Abstract

This phase 1 study (Clinicaltrials.gov: NCT00507442) was conducted to determine the maximum tolerated dose (MTD) of cyclophosphamide in combination with bortezomib, dexamethasone and lenalidomide (VDCR) and to assess the safety and efficacy of this combination in untreated multiple myeloma patients. Cohorts of three to six patients received a cyclophosphamide dosage of 100, 200, 300, 400 or 500 mg/m2 (on days 1 and 8) plus bortezomib 1.3 mg/m2 (on days 1, 4, 8 and 11), dexamethasone 40 mg (on days 1, 8 and 15) and lenalidomide 15 mg (on days 1–14), for eight 21-day induction cycles, followed by four 42-day maintenance cycles (bortezomib 1.3 mg/m2, on days 1, 8, 15 and 22). The MTD was the cyclophosphamide dose below which more than one of six patients experienced a dose-limiting toxicity (DLT). Twenty-five patients were treated. Two DLTs were seen, of grade 4 febrile neutropenia (cyclophosphamide 400 mg/m2) and grade 4 herpes zoster despite antiviral prophylaxis (cyclophosphamide 500 mg/m2). No cumulative hematological toxicity or thromboembolic episodes were reported. The overall response rate was 96%, including 20% stringent complete response (CR), 40% CR/near-complete response and 68% ≥ very good partial response. VDCR is well tolerated and highly active in this population. No MTD was reached; the recommended phase 2 cyclophosphamide dose in VDCR is 500 mg/m2, which was the highest dose tested.

Keywords: multiple myeloma, clinical trial, bortezomib, lenalidomide, multidrug combination, phase 1

Introduction

Treatment of multiple myeloma (MM) has changed dramatically since the introduction of the proteasome inhibitor bortezomib (VELCADE) and the immunomodulatory drugs thalidomide (Thalomid) and lenalidomide (Revlimid), resulting in improved survival for patients with MM.1,2 The most dramatic changes have been in the initial therapy of MM, wherein a number of clinical trials have evaluated various drug combinations including one or more of these drugs. These trials have evaluated novel combinations both in younger patients undergoing induction therapy followed by high-dose therapy and autologous stem cell transplantation (HDT-ASCT), as well as in older patients and in those who are considered ineligible for transplant. Two- and three-drug regimens combining dexamethasone with bortezomib,3–5 lenalidomide,6–9 bortezomib and lenalidomide,10,11 and bortezomib or lenalidomide plus the alkylating agent cyclophosphamide12–14 have been shown to be effective and well-tolerated in previously untreated MM. These regimens have led to significant improvement in myeloma-related early mortality as well as high complete response (CR) rates, which may translate into improved long-term outcomes, including prolonged survival.15,16 Given the promising activity of the two- and three-drug combinations, we hypothesized that combining bortezomib and lenalidomide with dexamethasone and cyclophosphamide in a four-drug regimen (VDCR) may result in even higher response rates as well as deeper responses.

The phase 1/2 EVOLUTION (Evaluation of VELCADE, dexamethasOne and Lenalidomide with or without cyclophosphamide Using Targeted Innovative ONcology strategies in the treatment of frontline MM) study was designed to investigate the safety and efficacy of bortezomib plus dexamethasone in combination with lenalidomide (VDR), cyclophosphamide (VDC) or VDCR in previously untreated MM patients. Here, we report the results of the phase 1 study, which was designed to determine the maximum tolerated dose (MTD) of cyclophosphamide that can be combined with bortezomib, dexamethasone and lenalidomide.

Materials and methods

Patients

Patients aged ≥ 18 years with previously untreated MM, with measurable disease and a Karnofsky performance status (KPS) ≥ 50%, were enrolled, regardless of their eligibility for HDT-ASCT. Measurable disease was defined as at least one of the following: serum M-protein ≥ 1 g/dl (≥ 10 g/l); urine M-protein ≥ 200 mg every24 h; or a serum free light chain (FLC) assay with an involved FLC level ≥ 10 mg/dl (≥ 100 mg/l), provided the serum FLC ratio was abnormal.17

Patients were excluded from the study if they had grade ≥ 2 peripheral neuropathy18 serum creatinine ≥ 2.5 mg/dl, absolute neutrophil count < 1000/µl, platelet count < 70 000/µl, AST/ALT > 2 × upper limit of normal or total bilirubin > 3 × upper limit of normal. Concomitant treatment with dexamethasone at doses other than those as per protocol, other corticosteroids, anti-neoplastic agents or investigational agents was not permitted. All patients provided written informed consent. The review boards at each study site approved the study, which was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Study design

The phase 1 study was conducted at 10 centers and enrolled patients from June 2007 to June 2008. We present the results as of the data cut-off of 22 July 2009. The primary objective was to determine the MTD of cyclophosphamide administered in combination with bortezomib, dexamethasone and lenalidomide. Secondary objectives were to evaluate the safety of this four-drug regimen, as well as the response rates, time-to-response, time-to-progression, progression-free survival and overall survival following therapy with VDCR in patients with previously untreated MM.

Cohorts of three to six patients received oral cyclophosphamide at doses of 100, 200, 300, 400 or 500 mg/m2 (on days 1 and 8) in combination with intravenous bortezomib (1.3 mg/m2, on days 1, 4, 8 and 11), oral dexamethasone (40 mg, on days 1, 8 and 15) and oral lenalidomide (15 mg, on days 1–14). Patients received up to eight 21-day treatment cycles of VDCR (induction), followed by up to four 42-day maintenance cycles of weekly bortezomib (1.3 mg/m2, on days 1, 8, 15 and 22). Peripheral blood stem cell collection was permitted after cycle 2 and eligible patients could discontinue therapy after cycle 4 to undergo HDT-ASCT. Cohorts were enrolled at each cyclophosphamide dose level until more than one patient experienced a dose-limiting toxicity (DLT) during cycle 1, or the maximum planned dose of 500 mg/m2 was reached. DLT was defined as one or more of the following toxicities: platelet count < 25 000/mm3 lasting for > 7 days or a platelet count < 10 000/mm3 or grade 4 neutropenia of > 7 days duration; any ≥ grade 3 non-hematological toxicity considered to be related to cyclophosphamide (except inadequately treated nausea, vomiting and diarrhea), or any hematological or non-hematological toxicity considered to be related to cyclophosphamide resulting in a treatment delay of > 2 weeks. After the first cycle, dose modifications for toxicity were permitted in accordance with pre-defined guidelines.

Patients could receive supportive therapy including bisphosphonates and transfusions as necessary. Prophylactic aspirin (325 mg daily) was required; warfarin or low-molecular weight heparin could be substituted at the investigator’s discretion based on risk for thrombosis. Antibiotics for Pneumocystis prophylaxis and acyclovir for herpes zoster prophylaxis were recommended. Erythropoietin use was permitted but not recommended, as it could increase the risk of lenalidomide-associated thromboembolism.19 Use of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor as prophylaxis for patients experiencing grade 4 neutropenia for > 7 days or febrile neutropenia was permitted after day 8 of the second and subsequent cycles.

Patients were discontinued from therapy if they experienced unacceptable toxicity or progressive disease (PD), had an unsatisfactory therapeutic response (investigator’s judgment), declined further treatment, were lost to follow-up, underwent HDT-ASCT or if there was a violation of the study protocol. Following treatment or discontinuation, patients without PD entered a short-term follow-up period and were monitored every 12 weeks until PD. After PD, patients entered long-term follow-up, and were contacted through telephone every 3 months to assess the survival and alternative treatments for MM.

Assessments

Adverse events (AEs) were recorded throughout the study and for 30 days after the last dose of the study drug and were graded according to NCI CTCAE version 3.0.18 Response was assessed before every other treatment cycle from cycle 3 onwards. Response categories were based on the uniform response criteria of the International Myeloma Working Group,17 with the addition of near-complete response (nCR) (defined as meeting the CR criteria but with positive serum and/or urine immunofixation).20 Specifically, CR required serum and urine to be immunofixation-negative, and < 5% marrow plasma cells, and stringent complete response (sCR) required in addition a normal serum FLC ratio and no marrow plasma cells by immunohistochemistry or immunofluorescence. Very good partial response (VGPR) required a ≥ 90% reduction in serum M-protein and a urine M-protein level of < 100 mg/24 h; patients could be classified as achieving nCR if they had no detectable M-protein by electrophoresis but were immunofixation-positive in serum and/or urine. PR required a ≥ 50% reduction in serum M-protein and a ≥ 90% reduction in urine M-protein (or an absolute level < 200 mg/24 h), as well as a ≥ 50% decrease in any soft tissue plasmacytomas. Patients were classified as having PD if they had a ≥ 25% increase in serum or urine M-protein, in soft tissue plasmacytomas or in bone marrow plasma cells. Patients who had a measurable disease based on elevated FLC levels were classified as achieving PR if they had a ≥ 50% decrease in the difference between involved and uninvolved FLC levels and as achieving very good partial response (VGPR) if they were immunofixation-negative for M-protein in serum and urine. These patients were classified as having PD if they had a ≥ 25% increase in the difference between involved and uninvolved FLC levels (absolute increase > 100 mg/l). The criteria were applied by an automated computer algorithm used to determine the response. The use of the algorithm assures consistent and rigorous assessment of responses across all patients.

A central laboratory was used for M-protein and FLC quantification, immunofixation and evaluation of minimal residual disease by multiparameter flow cytometry. One bone marrow assessment was required for documentation of CR and repeat assessments of serum and urine protein electrophoresis, serum and urine immunofixation, and serum FLCs were required to confirm CR. Bone marrow aspirate samples for cytogenetic analysis and immunophenotyping were collected for 8 weeks before the first dose of study drug treatment; samples were also obtained from patients with suspected CR for evaluation of minimal residual disease. Cytogenetic profiles were assessed using conventional metaphase cytogenetics and fluorescence in situ hybridization. The following findings were classified as ‘high risk’: del 13 or −13q14 (by conventional cytogenetic analysis only), t[4;14], t[14;16], −17p13 or hypodiploidy.

Statistical methods

The safety population included all patients who received at least one dose of any study drug. The DLT-evaluable population included all patients who experienced DLT during the first treatment cycle or received all scheduled doses in cycle 1 without prohibited concomitant treatment.

Results

Patient characteristics and disposition

A total of 26 patients were enrolled, of whom 25 received at least one dose of any study drug and were included in the safety population. Demographic and baseline clinical characteristics, including cytogenetic data, are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic and baseline clinical characteristics (safety population)

| Characteristic | N = 25 |

|---|---|

| Median age, years (range) | 61 (49–79) |

| Aged ≥ 65 years, n (%) | 7 (28) |

| Aged ≥ 75 years, n (%) | 2 (8) |

| Male, n (%) | 13 (52) |

| Myeloma type, n (%) | |

| IgG | 15 (60) |

| IgA | 5 (20) |

| Free λ light chain | 3 (12) |

| Free κ light chain | 2 (8) |

| ISS stage at diagnosis (as reported by the investigator), n (%) | |

| First | 12 (48) |

| Second | 12 (48) |

| Third | 1 (4) |

| β2-Microglobulin (mg/l), n (%) | |

| < 2.5 | 8 (32) |

| 2.5–5.5 | 15 (60) |

| > 5.5 | 1 (4) |

| Missing (sample not assessable by central laboratory) | 1 (4) |

| Karnofsky performance status, n (%) | |

| 70–80% | 11 (44) |

| 90–100% | 14 (56) |

| Eligible for ASCT at baseline (physician assessment), n (%) | 22 (88) |

| Median (range) time from diagnosis, months | 2.0 (0.1–29.1) |

| Median (range) serum M-protein, g/dl | 23.0 (0–94.0) |

| Median (range) urine M-protein, g/24h | 0.02 (0–3.1) |

| Median (range) creatinine, µmol/l | 79.6 (52.2–196.2) |

| Creatinine clearance (ml/min), n (%) | |

| > 30–60 | 5 (20) |

| > 60 | 20 (80) |

| Abnormalities observed by conventional/molecular cytogenetic testing, n (%) | |

| Del 13 (standard cytogenetics) | 3 (12) |

| −13q14 (FISH) | 8 (32) |

| t (4;14) | 3 (12) |

| −17p13 | 5 (20) |

| Hypodiploidy | 0 |

| High-risk | 9 (36) |

Abbreviations: ASCT, autologous stem cell transplantation; FISH, fluorescence in situ hybridization; Ig, immunoglobulin.

High risk was defined as any of del 13 or −13q14 (by conventional cytogenetic analysis methods only), t[4;14], t[14;16], −17p13 or hypodiploidy.

Treatment assignment by cohort is shown in Table 2. In all, 17 (68%) patients completed treatment: 10 proceeded to HDT-ASCT and 7 received the maximum number of cycles per protocol. Eight patients did not complete the treatment, two because of AEs, one because of a serious AE of grade 3 lobar pneumonia at a dose of 300 mg/m2 cyclophosphamide, considered related to treatment during cycle 6; two declined further treatment, one had an unsatisfactory response by investigator judgment, one had PDand two discontinued because of other reasons.

Table 2.

Treatment assignment by cohort

| Dose level | Enrolled | Treateda | Patients undergoing ASCT | Patients entering maintenance | Patients completing treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (Cy 100mg/m2) | 3 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| 2 (Cy 200mg/m2) | 4 | 4b | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| 3 (Cy 300mg/m2) | 4 | 4b | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| 4 (Cy 400mg/m2) | 8 | 7c | 5 | 2 | 6 |

| 5 (Cy 500mg/m2) | 7 | 7b | 0 | 4 | 4 |

| Total | 26 | 25 | 10 | 9 | 17 |

Abbreviations: ASCT, autologous stem cell transplantation; Cy, cyclophosphamide.

Safety population.

One patient did not complete cycle 1 for reasons other than DLT (did not adhere to protocol) and was therefore not evaluable for DLT as per protocol, but did continue on therapy and is therefore evaluable for response.

One patient in dose level 4 was excluded from the safety population (did not receive study treatment because of a heart problem).

DLT and determination of MTD

One patient experienced DLT (grade 4 febrile neutropenia) at a dose of 400 mg/m2 cyclophosphamide, resulting in dose reduction and delay, and one patient experienced DLT (grade 3 herpes zoster virus reactivation despite antiviral prophylaxis) at a dose of 500 mg/m2 cyclophosphamide, resulting in dose reduction. As the MTD was not reached, the recommended phase 2 dose of cyclophosphamide in combination with bortezomib, dexamethasone and lenalidomide is 500 mg/m2, which was the highest dose tested.

Treatment exposure

Patients received a median of six treatment cycles (range, 3–12); nine patients completed all eight cycles of induction and proceeded to maintenance (Table 2), of whom seven received all the four maintenance cycles. In total, thirteen patients required one or more dose reductions during induction therapy: ten for bortezomib, three for dexamethasone, seven for cyclophosphamide and three for lenalidomide. One additional patient had bortezomib dose reduced during maintenance. During the induction phase, the median dose of bortezomib per cycle was 4.9 mg/m2 (range, 2.4–5.3; expected dose 5.2 mg/m2), the median dose of dexamethasone per cycle was 120 mg (range, 66–120; expected dose 120 mg) and the median dose of lenalidomide per cycle was 210 mg (range, 138–210; expected dose 210 mg).

Safety

The frequencies of common treatment-emergent non-hematological AEs and all treatment-emergent hematological toxicities are shown in Table 3. The most common grade 3/4 AE was Peripheral Neuropathy, which was seen in 4 (16%) patients, and was transient sensory neuropathy in one patient; there was also one patient with grade 3/4 autonomic neuropathy.

Table 3.

Summary of the most common treatment-emergent non-hematological adverse events and all treatment-emergent hematological toxicities (safety population)

| Most common treatment-emergent non-hematological adverse events (≥ 25% of the patients), N = 25 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Adverse event | All grades, n (%) | Grade ≥ 3, n (%) | |

| Fatigue | 18 (72) | 2 (8) | |

| Constipation | 17 (68) | 0 | |

| Nausea | 13 (52) | 1 (4) | |

| Peripheral sensory neuropathy | 12 (48) | 1 (4)a | |

| Diarrhea | 10 (40) | 1 (4) | |

| Vomiting | 10 (40) | 1 (4) | |

| Dizziness (excluding vertigo) | 9 (36) | 0 | |

| Insomnia | 9 (36) | 0 | |

| Peripheral neuropathy | 8 (32) | 4 (16) | |

| Pyrexia | 8 (32) | 0 | |

| Back pain | 8 (32) | 3 (12) | |

| Dyspnea | 7 (28) | 1 (4) | |

| Edema, lower limb | 7 (28) | 0 | |

| Treatment-emergent hematological toxicities, N = 25 | |||

| Toxicity | Grade 1/2, n (%) | Grade 3, n (%) | Grade 4, n (%) |

| Anemia | 21 (84) | 2 (8) | 1 (4) |

| Thrombocytopenia | 18 (72) | 0 | 3 (12) |

| Neutropenia | 13 (52) | 5 (20) | 1 (4) |

This patient, who had transient grade 3 sensory neuropathy, was one of the four patients who experienced grade 3/4 peripheral neuropathy. An additional patient had grade 3/4 autonomic neuropathy.

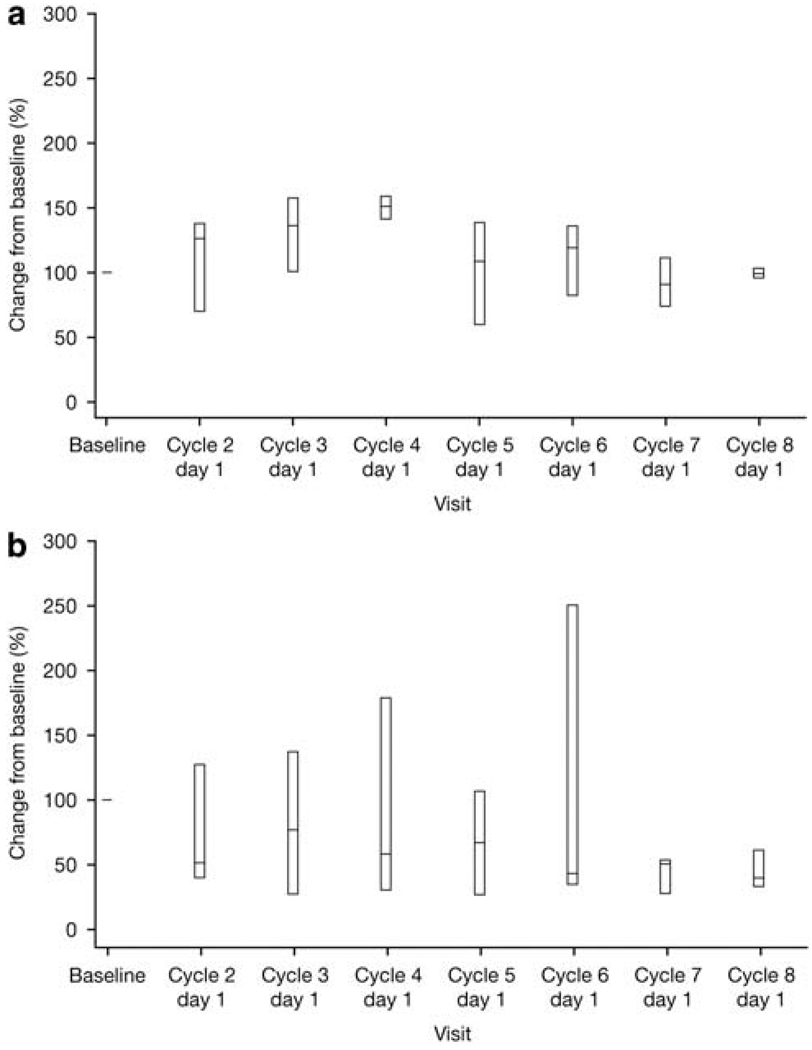

There was no evidence of cumulative hematological toxicity during induction therapy (Figure 1). No deep-vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism was reported, despite 18/25 patients receiving aspirin alone as DVT prophylaxis. Ten patients (40%) experienced at least one serious AE. Six patients (24%) experienced serious AEs considered to be related to the study treatment: one at 100 mg/m2 cyclophosphamide (grade 3 nausea and vomiting), two at 300 mg/m2 cyclophosphamide (grade 2 pyrexia; grade 3 lobar pneumonia, pancytopenia and febrile neutropenia), two at 400 mg/m2 cyclophosphamide (grade 4 leukopenia and febrile neutropenia and grade 3 typhlitis; grade 3 febrile neutropenia) and one at 500 mg/m2 cyclophosphamide (grade 3 angioneurotic edema). Two patients died during the follow-up period: one patient treated at the 200 mg/m2 cyclophosphamide dose, because of disease progression,and one patient treated at the 400 mg/m2 cyclophosphamide dose, because of subdural hematoma related to a fall.

Figure 1.

Box plot (with whiskers showing 10th to 90th percentile) of change in platelet count (a), and neutrophil count (b) over time for patients treated at dose level 5.

Efficacy

The Overall Response Rate (ORR) (CR, very good partial response and PR) to induction therapy (cycles 1–8) was 96%, with 68% of patients experiencing at least a very good partial response (VGPR) (Table 4). The sCR rate was 20%, and the CR/nCR rate was 40%, with 36% of patients achieving an immunofixation-negative CR. Of the nine patients with high-risk cytogenetics, three achieved a CR and four a very good partial response (VGPR). The rates appeared to be independent of cyclophosphamide dose, although patient numbers are limited. The single patient who failed to obtain a response received three cycles of therapy before discontinuing for PD due to a new soft tissue plasmacytoma. The median time to first response in responding patients was 49 days (range, 41–121) and the median time to best response was 95 days (range, 43–255). Time-to-progression, progression-free survival and overall survival could not be assessed as, at the time of data cut-off, only one patient had progressed and two patients had died. The patient who progressed had obtained a best response of PR and subsequently developed extramedullary progression.

Table 4.

Best confirmed response to treatment, by dose level

| Best confirmed response, N = 25 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dose level | Patients | CR (sCR) | VGPR (nCR) | PRa | PD |

| 1 (Cy 100 mg/m2) | 3 | 2 (2) | 1 (0) | 1 | 0 |

| 2 (Cy 200 mg/m2) | 4 | 1 (1) | 0 | 2 | 1 |

| 3 (Cy 300 mg/m2) | 4 | 1 (1) | 3 (1) | 3 | 0 |

| 4 (Cy 400 mg/m2) | 7 | 2 (0) | 3 (0) | 5 | 0 |

| 5 (Cy 500 mg/m2) | 7 | 3 (1) | 1 (0) | 4 | 0 |

| Total | 25 | 9 (5) | 8 (1) | 15 | 1 |

| Overall response rate, n (%) | 24 (96) | ||||

| ≥ VGPR rate, n (%) | 17 (68) | ||||

| CR/nCR rate, n (%) | 10 (40) | ||||

| CR rate, n (%) | 9 (36) | ||||

| sCR rate, n (%) | 5 (20) | ||||

Abbreviations: CR, complete response; Cy, cyclophosphamide; nCR, near-complete response; PD, progressive disease; PR, partial response; sCR, stringent complete response; VGPR, very good partial response.

Includes VGPR.

Other end points

Thirteen patients have undergone stem cell mobilization, with a median CD34+ yield of 5.5 × 106/kg (range, 1.8–10.3). Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor alone was used for the first cycle of mobilization. One patient required a second cycle of stem cell mobilization. At the time of data cut-off, ten patients had discontinued treatment to undergo HDT-ASCT.

Discussion

The introduction of bortezomib and immunomodulatory drugs and their judicious combination with old drugs in carefully designed clinical trials has led to a paradigm shift in the treatment of myeloma. These trials showed a high efficacy when any of these drugs were combined with corticosteroids and/or alkylating agents or when they were combined together. The high response rates, especially CR rates, seen in these studies highlight the prospect of obtaining profound reductions in tumor load, potentially translating into improved long-term outcomes. This study is the first to evaluate cyclophosphamide in combination with bortezomib, dexamethasone and lenalidomide in patients with newly diagnosed MM. In the phase 1 study, we determined that cyclophosphamide at a dose of 500 mg/m2 can be safely combined with VDR, resulting in a very high response rate and rate of CRs.

The results of the phase 1 portion of this study indicate that combining two novel agents, bortezomib and lenalidomide, with the standard anti-myeloma agents dexamethasone and cyclophosphamide is a feasible, well-tolerated frontline treatment approach. The most common treatment-emergent hematological and non-hematological AEs were consistent with those seen in previous studies evaluating combinations of bortezomib and/or lenalidomide with cyclophosphamide and/or dexamethasone.5,8,10,12–14 Thrombosis events that have been seen with thalidomide and lenalidomide did not occur in the current study.21 This is despite 18/25 patients receiving aspirin alone as thromboprophylaxis, consistent with other studies of bortezomib in combination with immunomodulatory drugs.10,22 The most common grade 3/4 non-hematological AE was Peripheral Neuropathy (in four patients), a toxicity that is manageable and reversible in the majority of patients. With single-agent bortezomib in previously untreated MM patients, 85% of patients showed improvement or resolution of treatment-related sensory Peripheral Neuropathy in a median of 98 days,23 while in patients with relapsed MM, 64% of patients with grade ≥ 2 Peripheral Neuropathy showed improvement or resolution in a median of 110 days.24 Similar findings have been reported in combination studies in previously untreated patients.25,26 The majority of patients in the present study experienced thrombocytopenia, neutropenia and/or anemia, but these were mild or moderate in severity and manageable. Most importantly, there was no evidence of cumulative hematological toxicity as shown by the lack of any downward trend in the platelet or neutrophil count with increasing duration of therapy (Figure 1). Nevertheless, grade 3/4 myelosuppression appeared to be somewhat more frequent with VDCR than reported for the two- and three-agent combinations.5,8,10,12 The most common treatment-emergent serious adverse event was febrile neutropenia (three patients). It is important to note that 7 (28%) patients in the current study were aged ≥ 65 years, including 2 who were aged at least 75 years, and the tolerability of the regimen was favorable in this patient group as well.

High response rates were achieved in this phase 1 study; the ORR was 96%, with 40% CR/nCR, including 20% sCR. These response rates appeared to be comparable to or somewhat higher than those reported in recent studies of the three-drug combinations VDR (ORR 100%),10 lenalidomide, cyclophosphamide and dexamethasone (RCd, ORR: 83%),13 VDC (ORR 84–88%),12,14 and VDC (three cycles) followed by bortezomib, thalidomide and dexamethasone (VTD; three cycles) (ORR 95%) in newly diagnosed MM patients.27 Stringent CR rates and durability data have not yet been reported for all these studies.

In addition to the three-drug regimens noted above, other three- and four-drug combinations that include bortezomib and/or lenalidomide or thalidomide are also being evaluated and are proving to be highly active and generally well-tolerated induction therapies in this setting. This plethora of studies suggests a shift in the treatment paradigm for newly diagnosed MM toward the use of such multiagent combinations, both as induction therapy before HDT-ASCT and as frontline treatment for non-transplant patients. However, longer-term follow-up as well as head-to-head comparisons of efficacy and toxicity are required for these combinations to determine whether the high response rates translate into improved survival, and to determine the most efficacious combination in these patient populations.

In addition to the high overall response rates, ongoing trials of combination regimens are targeting the depth of response as indicated by the ability to achieve an sCR or minimal residual disease (MRD) negative status. In many hematological malignancies, assessment of minimal residual disease (MRD) following treatment is standard practice, but this is still under investigation in MM, given the lack of treatments with high CR rates until now.28 Recent data suggest that minimal residual disease (MRD)-negative status, as assessed by immunophenotyping through multiparameter flow cytometry, is a better predictor of survival than CR as evaluated by immunofixation.29 In the current study, baseline bone marrow samples were collected and successfully analyzed using flow cytometry for the majority of patients (23/25; 92%). This information will provide a better estimate of the efficacy of this regimen as additional data are collected in the phase 2 portion of the trial.

Conclusion

Cyclophosphamide with bortezomib, dexamethasone and lenalidomide, VDCR, is a generally well-tolerated and highly active novel four-drug regimen in patients with previously untreated MM. The recommended dose of cyclophosphamide in this regimen was established as 500 mg/m2, which was the highest dose tested. Enrolment to the three-arm, randomized phase 2 portion of this study, which is investigating cyclophosphamide 500 mg/m2 in combination with bortezomib and dexamethasone, with or without lenalidomide (VDCR/VDC) or VDR, has been completed recently and analysis is going on.

Acknowledgements

We thank all the patients who participated in the study, all the investigators, nursing staff and research support staff involved in the studyand the research team at Millennium Pharmaceuticals. We would like to acknowledge the editorial assistance of Sarah Maloney and Jane Saunders of FireKite during the development of this publication, which was funded by Millennium Pharmaceuticals and supported by Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceutical Research & Development, LLC and Millennium Pharmaceuticals.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

SKK has a consultancy/advisory relationship, and has received research funding from Millennium Pharmaceuticals, Celgene; IF has received honoraria and research funding from Millennium Pharmaceuticals; SJN has received honoraria from Millennium Pharmaceuticals; PH has a consultancy/advisory relationship with Millennium Pharmaceuticals and Celgene; has received honoraria from Celgene and research funding from Millennium Pharmaceuticals; RR has a consultancy/advisory relationship with Millennium Pharmaceuticals and has received honoraria from Millennium Pharmaceuticals, Celgene and Amgen; NC has received research funding from Millennium Pharmaceuticals; MB has received honoraria from Pfizer, Spectrum Pharmaceuticals, Millennium Pharmaceuticals and Cephalon; JLW has received honoraria from Millennium Pharmaceuticals, Celgene and Ortho Biotech; CG has a consultancy/advisory relationship, and has received honoraria and research funding from Millennium Pharmaceuticals and Celgene; AK has stock/ownership interest in Celgene, and has received honoraria from Millennium Pharmaceuticals and Celgene; DG has a consultancy/advisory relationship with and has received honoraria from Millennium Pharmaceuticals; EAS has a consultancy/advisory relationship with Millennium Pharmaceuticals and has received honoraria from Millennium Pharmaceuticals and Celgene; HS and IJW are employees of Millennium Pharmaceuticals; PGR has a consultancy/advisory role in Millennium Pharmaceuticals and Celgene and has received research funding from Millennium Pharmaceuticals; JG and SVR declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Kumar SK, Rajkumar SV, Dispenzieri A, Lacy MQ, Hayman SR, Buadi FK, et al. Improved survival in multiple myeloma and the impact of novel therapies. Blood. 2008;111:2516–2520. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-10-116129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brenner H, Gondos A, Pulte D. Recent major improvement in long-term survival of younger patients with multiple myeloma. Blood. 2008;111:2521–2526. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-08-104984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jagannath S, Durie BG, Wolf JL, Camacho ES, Irwin D, Lutzky J, et al. Extended follow-up of a phase 2 trial of bortezomib alone and in combination with dexamethasone for the frontline treatment of multiple myeloma. Br J Haematol. 2009;146:619–626. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2009.07803.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harousseau JL, Attal M, Leleu X, Troncy J, Pegourie B, Stoppa AM, et al. Bortezomib plus dexamethasone as induction treatment prior to autologous stem cell transplantation in patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: results of an IFM phase II study. Haematologica. 2006;91:1498–1505. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harousseau JL, Mathiot C, Attal M, Marit G, Caillot D, Hulin C, et al. Bortezomib/dexamethasone versus VAD as induction prior to autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT) in previously untreated multiple myeloma (MM): updated data from IFM 2005/01 trial. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:455s. Abstract 8505; updated data presented at the ASH 2008 joint ASH/ASCO symposium. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rajkumar SV, Hayman SR, Lacy MQ, Dispenzieri A, Geyer SM, Kabat B, et al. Combination therapy with lenalidomide plus dexamethasone (Rev/Dex) for newly diagnosed myeloma. Blood. 2005;106:4050–4053. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-07-2817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lacy MQ, Gertz MA, Dispenzieri A, Hayman SR, Geyer S, Kabat B, et al. Long-term results of response to therapy, time to progression, and survival with lenalidomide plus dexamethasone in newly diagnosed myeloma. Mayo Clin Proc. 2007;82:1179–1184. doi: 10.4065/82.10.1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zonder JA, Crowley J, Hussein MA, Bolejack V, Moore DF, Whittenberger BF, et al. Superiority of lenalidomide (Len) plus high-dose dexamethasone (HD) compared to HD alone as treatment of newly-diagnosed multiple myeloma (NDMM): results of the randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled SWOG trial S0232. Blood. 2007;110:32a. Abstract 77. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rajkumar SV, Jacobus S, Callander NS, Fonseca R, Vesole DH, Williams ME, et al. Lenalidomide plus high-dose dexamethasone versus lenalidomide plus low-dose dexamethasone as initial therapy for newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: an open-label randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:29–37. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70284-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Richardson PG, Lonial S, Jakubowiak AJ, Jagannath S, Raje NS, Avigan DE, et al. High response rates and encouraging time-to-event data with lenalidomide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: final results of a phase I/II study. Blood. 2009;114:501a–502a. Abstract 1218. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang M, Delasalle K, Giralt S, Alexanian R. Rapid control of previously untreated multiple myeloma with bortezomib-lenalidomide-dexamethasone (BLD) Blood. 2007;110:1057a. doi: 10.1179/102453310X12583347010133. Abstract 3611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Knop S, Liebisch P, Wandt H, Kropff M, Jung W, Kroeger N, et al. Bortezomib, IV cyclophosphamide, and dexamethasone (VelCD) as induction therapy in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: results of an interim analysis of the German DSMM Xia trial. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:437s. Abstract 8516. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kumar S, Hayman S, Buadi F, Lacy M, Stewart K, Allred J, et al. Phase II trial of lenalidomide (Revlimid) with cyclophosphamide and dexamethasone (RCd) for newly diagnosed myeloma. Blood. 2008;112:40a. Abstract 91. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reeder CB, Reece DE, Kukreti V, Chen C, Trudel S, Hentz J, et al. Cyclophosphamide, bortezomib and dexamethasone induction for newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: high response rates in a phase II clinical trial. Leukemia. 2009;23:1337–1341. doi: 10.1038/leu.2009.26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lahuerta JJ, Mateos MV, Martinez-Lopez J, Rosinol L, Sureda A, de la RJ, et al. Influence of pre- and post-transplantation responses on outcome of patients with multiple myeloma: sequential improvement of response and achievement of complete response are associated with longer survival. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:5775–5782. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.9721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van de Velde HJK, Liu X, Chen G, Cakana A, Deraedt W, Bayssas M. Complete response correlates with long-term survival and progression-free survival in high-dose therapy in multiple myeloma. Haematologica. 2007;92:1399–1406. doi: 10.3324/haematol.11534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Durie BG, Harousseau JL, Miguel JS, Blade J, Barlogie B, Anderson K, et al. International uniform response criteria for multiple myeloma. Leukemia. 2006;20:1467–1473. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.National Cancer Institute. Cancer Therapy Evaluation Program Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events. Version 3.0. 2006 http://ctep.cancer.gov, Available from http://ctep.cancer.gov/protocolDevelopment/electronic_applications/docs/ctcaev3.pdf.

- 19.Knight R, DeLap RJ, Zeldis JB. Lenalidomide and venous thrombosis in multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2079–2080. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc053530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Richardson PG, Barlogie B, Berenson J, Singhal S, Jagannath S, Irwin D, et al. A phase 2 study of bortezomib in relapsed, refractory myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2609–2617. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Palumbo A, Rajkumar SV, Dimopoulos MA, Richardson PG, San MJ, Barlogie B, et al. Prevention of thalidomide- and lenalidomide-associated thrombosis in myeloma. Leukemia. 2008;22:414–423. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2405062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cavo M, Tacchetti P, Patriarca F, Petrucci MT, Pantani L, Galli M, et al. A phase III study of double autotransplantation incorporating bortezomib-thalidomide-dexamethasone (VTD) or thalidomide-dexamethasone (TD) for multiple myeloma: superior clinical outcomes with VTD compared to TD. Blood. 2009;114:148a–149a. Abstract 351. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Richardson P, Xie W, Mitsiades C, Chanan-Khan AA, Lonial S, Hassoun H, et al. Single-agent bortezomib in previously untreated multiple myeloma: efficacy, characterization of peripheral neuropathy, and molecular correlations with response and neuropathy. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3518–3525. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.3087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Richardson PG, Sonneveld P, Schuster MW, Stadtmauer EA, Facon T, Harousseau JL, et al. Reversibility of symptomatic peripheral neuropathy with bortezomib in the phase III APEX trial in relapsed multiple myeloma: impact of a dose-modification guideline. Br J Haematol. 2009;144:895–903. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2008.07573.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mateos M-V, Richardson PG, Schlag R, Khuageva NK, Dimopoulos MA, Shpilberg O, et al. Peripheral neuropathy with VMP resolves in the majority of patients and shows a rate plateau. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma. 2009;9:S30. Abstract 172. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Popat R, Oakervee HE, Hallam S, Curry N, Odeh L, Foot N, et al. Bortezomib, doxorubicin and dexamethasone (PAD) front-line treatment of multiple myeloma: updated results after long-term follow-up. Br J Haematol. 2008;141:512–516. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2008.06997.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bensinger WI, Jagannath S, Vescio R, Camacho E, Wolf J, Irwin D, et al. Phase 2 study of two sequential three-drug combinations containing bortezomib, cyclophosphamide and dexamethasone, followed by bortezomib, thalidomide and dexamethasone as frontline therapy for multiple myeloma. Br J Haematol. 2009 doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2009.07981.x. E-pub ahead of print; doi:10.1111/j.1365-2141.2009.07981.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Anderson KC, Kyle RA, Rajkumar SV, Stewart AK, Weber D, Richardson P. Clinically relevant end points and new drug approvals for myeloma. Leukemia. 2008;22:231–239. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2405016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Paiva B, Vidriales MB, Cervero J, Mateo G, Perez JJ, Montalban MA, et al. Multiparameter flow cytometric remission is the most relevant prognostic factor for multiple myeloma patients who undergo autologous stem cell transplantation. Blood. 2008;112:4017–4023. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-05-159624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]