Abstract

Background

Dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) and Parkinson’s disease dementia (PDD) are the two most common types of dementing neurodegenerative disease after Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Both of these conditions are often diagnosed late or not at all.

Methods

Selective literature review.

Results

The severe cholinergic and dopaminergic deficits that are present in both DLB and PDD produce not only motor manifestations, but also cognitive deficits, mainly in the executive and visual-constructive areas, as well as psychotic manifestations such as visual hallucinations, delusions, and agitation. The intensity of these manifestations can fluctuate markedly over the course of the day, particularly in DLB. Useful tests for differential diagnosis include magnetic resonance imaging and electroencephalography; in case of clinical uncertainty, nuclear medical procedures and cerebrospinal fluid analysis can be helpful as well. Neuropathological studies have revealed progressive alpha-synuclein aggregation in affected areas of the brain. In DLB, beta-amyloid abnormalities are often seen as well.

Conclusion

DLB should be included in the differential diagnosis of early dementia. If motor manifestations arise within one year (DLB), dopaminergic treatment should be initiated. On the other hand, patients with Parkinson’s disease should undergo early screening for signs of dementia so that further diagnostic and therapeutic steps can be taken in timely fashion, as indicated. Cholinesterase inhibitors are useful for the treatment of cognitive deficits and experiential/behavioral disturbances in both DLB (off-label indication) and PDD (approved indication).

The question of whether dementia is an inevitable fate for many of us as we grow older cannot be answered with a simple “yes” or “no.” Old age is the most important risk factor for the development of any dementia. The older the mean age of a population, the greater the total number of people with dementia. In Germany, 6.5% to 8.7% of the population older than 65 years and 30% of those older than 89 are affected by one of the different types of dementia. Even if the incidence of dementia remains stable, the number of those affected in Germany will about double by 2050, owing to the aging population alone.

Neurodegenerative changes are the most common causes for dementia (for example, Alzheimer’s disease [AD]), followed by microangiopathies or macroangiopathies. Patients with such vascular cerebral changes often show additional and relevant neurodegenerative changes at postmortem (e1).

In the past decades, further, relatively common subcategories of neurogenerative dementias have been defined, clinically as well as neuropathologically. These include dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB)—the occurrence of dementia before Parkinson’s syndrome—and Parkinson’s disease dementia (PDD). Because these types of dementia respond to treatment with cholinesterase inhibitors, and because of the serious side effects associated with administration of traditional neuroleptic drugs, it’s important to distinguish these from Alzheimer’s dementia. The diagnostic certainty of the medical diagnosis of dementia is still low, at 78% to 84%; especially the certainty in diagnosing Lewy body dementia is low (e2). This may be due to the overlap of symptoms with the symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease, but it may also be due to lacking awareness of these disease entities among doctors.

The diagnostic evaluation and treatment of Lewy body dementia and Parkinson’s disease dementia require notably higher resources per patient than in Alzheimer’s disease (2). The probable reason for this is the combination of cognitive and physical impairments in the former dementia types. Both DLB and PDD also lead to a reduced quality of life for patients and an increased psychological burden for the relatives and carers compared with Alzheimer’s disease (2, e3).

Epidemiology

Like Alzheimer’s disease, dementia with Lewy bodies is a common neurodegenerative type of dementia. According to different studies, the estimated prevalence of DLB among all dementias is 3.6% to 6.6% in people older than 65 and 1.7% to 30.5% in dementia patients older than 65; these findings depend on the study design (3).

Parkinson’s disease itself is one of the more common diseases of old age; its prevalence is 1.8% in people older than 65. Compared with the general population, Parkinson’s patients have a sixfold increased risk of developing dementia (4, e4). According to a systematic review, the prevalence of Parkinson’s disease dementia is 0.5% in those older than 65 in the general population and 3.6% in dementia patients (e5). However, the data on Parkinson’s disease dementia are subject to great variation—namely, 39.9% (e6) to up to 80% after a mean disease course of 8 years (e7).

Risk factors for developing Parkinson’s disease dementia include hallucinations early on in the disease course and the akinetic-rigid type of Parkinson’s disease. Old age, comorbid depression, and nicotine misuse are also risk factors (e4).

Clinical symptoms

The main symptoms in Parkinson’s disease dementia include impaired executive functioning, impairments to visual-spatial functioning, cognitive deficits, and lack of drive that are mostly due to impaired memory function. In terms of memory, patients with Parkinson’s disease dementia are primarily affected by impaired strategic encoding and recall. Executive functions are the processes that are necessary to control behaviors and plan action. In addition to the dopaminergic system, further neurotransmitters of the central nervous system are essential for these deficits to develop, especially acetylcholine, noradrenalin, and serotonin (5).

Clinical course

The symptoms of dementia with Lewy bodies start with cognitive and/or further psychiatric impairments and are accompanied within the first year (or from the beginning) by the typical symptoms of Parkinson’s syndrome. In Parkinson’s disease dementia, cognitive deficits and/or dementia develop only if the full motor symptoms of Parkinson’s have been present for a minimum of one year (“one year rule” for clinical studies). If full-blown disease is present then usually no differences between the two disease entities exist, neither clinically nor neuropathologically.

Clinical classification criteria

Clinical classification criteria for dementia with Lewy bodies were first defined by a group of experts around McKeith in 1995 and revised in 1999 and 2005. The specificity of these criteria is 95%; their sensitivity is very low, at 32%, which is due to the overlap of clinical symptoms with those of Alzheimer’s disease, among other reasons (6). Boxes 1 and 2 show the classification criteria for dementia with Lewy bodies and Parkinson’s disease dementia.

Box 1. Clinical-diagnostic consensus criteria for dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB)*1.

-

Central characteristic

Dementia with impairments in everyday functioning and often well functioning memory at onset of illness

-

Key characteristics are

Fluctuating cognition (especially attention and awareness/alertness)

Visual hallucinations

Symptoms of Parkinson’s disease

-

Highly suggestive characteristics are

REM sleep behavior disorder

Pronounced oversensitivity to neuroleptics

Reduced dopaminergic activity in the basal ganglia (on SPECT or PET scan)

-

For a diagnosis of “possible” DLB

Central characteristic AND

at least one key characteristic or at least a strongly suggestive characteristic

-

For a diagnosis of “likely” DLB

Central characteristic AND

at least two key characteristics or one key characteristic together with one strongly suggestive characteristic

-

Supporting characteristics (these are often present, but they currently have no diagnostic specificity)

Repeated falls or episodes of syncope, transient impairment of consciousness, severe autonomic dysfunction (orthostatic hypotension, urinary incontinence), hallucinations in other modalities, systematic delusions, depression, an intact medial temporal lobe (cranial CT, cranial MRI scan), reduced metabolism, measured on SPECT/PET scan, especially in the occipital lobe, pathological MIBG-SPECT scan of the myocardium, slowed down EEG activity with intermittent temporal sharp waves

-

Findings that do not support DLB

Cerebrovascular lesions on cranial CT or cranial MRI or focal-neurological symptoms

Other disorders that may provide a satisfactory explanation for the clinical symptoms

Spontaneous symptoms of Parkinson’s disease which occur exclusively in severe dementia

*1 Modified (from McKeith et al, 19–21); SPECT, single photon emission computed tomography; PET, positron emission tomography; CT, computed tomography; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; MIBG-SPECT, 31-iodine metaiodobenzylguanidine single photon emission computed tomography; EEG, electroencephalography

Box 2. Summary of the clinical-diagnostic consensus criteria for Parkinson’s disease dementia (PDD)*1.

-

Key characteristics are (1)

Queen Square Brain Bank criteria*2 for Parkinson’s disease

-

Dementia with:

Impairments in more than one cognitive domain

Reduced cognition compared with the premorbid level

Deficit related impairments in everyday functioning

-

Associated clinical characteristics are (2)

Attention

Executive functions

Visual-spatial functions

Memory

Speech

Apathy

Personality changes and mood changes

Hallucinations

Delusions

Increased daytime fatigue

-

Characteristics that make a diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease dementia unlikely (3)

Presence of other abnormalities that may cause cognitive impairments (for example, a finding of relevant vascular lesions)

The time interval between the development of motor and cognitive symptoms is not known

-

Characteristics that are indicative of different circumstances/disorders as the cause of mental impairment (4)

Cognitive and behavioral symptoms only in combination with, for example, acute confusion in systemic illness, adverse effects from medication

Major depression according to the DSM-IV

Characteristics that are consistent with a suspected diagnosis of “probable vascular dementia”

-

For a diagnosis of “likely” Parkinson’s disease dementia

-

For a diagnosis of “possible” Parkinson’s disease dementia

Both key characteristics

(2) does not apply—for example, motor or sensorimotor aphasia or exclusive impairment of memory (memory function does not improve after help has been given or in recognition) while attentiveness remains, behavioral symptoms may be present or not, OR

one or more criteria listed under (2) are met

none of the criteria listed under (4) is met

*1 Modified from (22)

*2 Clinical criteria for a diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease according to which, in addition to the absence of exclusion criteria (such as no improvement after levodopa), the presence of supporting criteria (for example, unilateral onset), bradykinesis, and at least one of the following symptoms have to be present: muscle rigidity, resting tremor, and/or postural instability (e21)

Neurologically, 25% to 50% of patients with dementia with Lewy bodies have symptoms of Parkinson’s disease at the onset of their illness (e8). If these are not present initially then the disorder is often not diagnosed. Typically patients with Lewy body dementia also have a REM sleep behavior disorder (RBD) in the shape of lively and often anxiety-dominated dreams during the REM phase of sleep, which may be accompanied by motor symptoms. The REM sleep behavior disorder is characteristic for neurodegenerative disorders with pathological cerebral aggregates of the protein alpha-synuclein (7). Disorders of the autonomous nervous system are much more common in dementia with Lewy bodies than in Alzheimer’s disease. Often these lead to orthostatic dysregulations, which may be accompanied by vertigo/dizziness, result in syncope and may be the cause for increased falls, such as often occur in patients with Lewy body dementia or Parkinson’s disease dementia. Urinary incontinence is also more common in patients with dementia with Lewy bodies than in Alzheimer’s disease.

Psychiatrically, dementia with Lewy bodies and Parkinson’s disease dementia may be accompanied by depression and (mostly visual) hallucinations. Patients with dementia with Lewy bodies often report lively and colorful, sometimes complex, hallucinations in the shape of scenic sequences (8).

Additional investigations

Neuropsychological tests

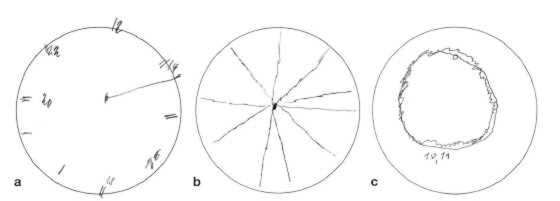

Patients who have dementia with Lewy bodies or Parkinson’s disease dementia display frontal-executive and visual-constructive deficits in both groups. The latter can be demonstrated particularly poignantly by means of the “clock drawing test”; the patients are asked to complete the pre-drawn circle of a clock face to show 10 minutes past 11 o’clock (Figure 1 a – c).

Figure 1: Clock drawing tests from three patients.

Male, age 73 years, diagnosis: dementia with Lewy bodies, MMSE score of 18 points

Male, age 80 years, diagnosis: Parkinson’s disease dementia, MMSE score: 25 points

Male, age 74 years, diagnosis Parkinson’s disease dementia, MMSE score: 20 points

MMSE, mini-mental state examination

Both dementias also have in common the fluctuating neuropsychological deficits. These are also responsible for the fact that cognitive impairments are usually not diagnosed by performing simple, global screening procedures, such as the mini-mental state examination (MMSE), only once.

Imaging

For reasons of differential diagnostic evaluation, cerebral imaging (preferably cranial magnetic resonance imaging [MRI]) should be undertaken in patients with Lewy body dementia and Parkinson’s disease dementia, to exclude structural changes and possible additional vascular lesions. Electroencephalography (EEG) is also recommended, to rule out an epilepsy related cause (e9). Patients with Lewy body dementia usually have slower EEG rhythms at baseline than patients with Alzheimer’s disease or Parkinson’s disease dementia (e10).

In dementia with Lewy bodies—by contrast to Alzheimer’s disease—a dopaminergic nigrostriatal deficit is present. Nuclear medical investigation to determine dopamine transporter binding are appropriate—for example, by means of FP-CIT SPECT (single photon emission computed tomography) scanning, to distinguish dementia with Lewy bodies (in the absence of comorbid Parkinson’s syndrome) from Alzheimer’s disease (sensitivity 78% and specificity 90%) (9). Szintigraphy of the myocardium can be used to show the sympathetic denervation of the heart in dementia with Lewy bodies and Parkinson’s disease dementia (e11). Nuclear medical techniques can also help in establishing the distinction to Alzheimer’s disease.

Analyzing cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) for beta-amyloid(1–42) and tau protein also helps in differentiating dementia with Lewy bodies from Alzheimer’s disease: in dementia with Lewy bodies, the tau protein measurement is mostly normal—except in some cases with an unusually rapid disease course—and beta-amyloid(1–42) is lowered (as in Alzheimer’s disease) (10, e12). For tau protein, the sensitivity and specificity for a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease versus dementia with Lewy bodies are 73% and 76%, respectively (e12). A normal finding on CSF analysis, however, rules out neither dementia with Lewy bodies nor Parkinson’s disease dementia.

Nuclear medical investigations and, in individual cases, CSF analysis should be considered in cases that are not clear on differential diagnostic evaluation.

The role of alpha-synuclein

Many neurodegenerative disorders are characterized by pathological protein aggregates in particularly vulnerable neural populations, which may result in the clinically characteristic disease symptoms—such as memory loss and Parkinson’s symptoms.

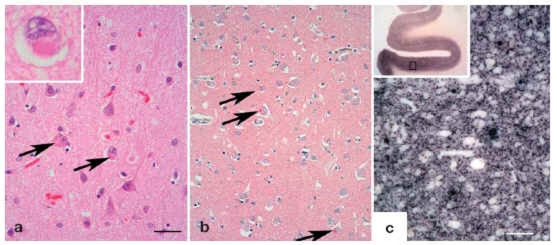

Parkinson’s disease dementia and dementia with Lewy bodies have pathomorphological structures that mainly consist of the protein alpha-synuclein (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Histology in dementia.

alpha-synuclein aggregates in the cortex of patients with Lewy body dementia can be shown in the shape of Lewy bodies by using conventional histological techniques; Bar=50 µm (HE, arrow, inset).

The cortical Lewy bodies are not as compact as those within the substantia nigra and can be visualized easily by using immunohistochemical techniques (antibodies 4B12 [Abcam]; red reaction product, blue counter stain, arrow).

More than 90% of alpha-synuclein aggregates do not form Lewy bodies. Using one of the modern molecular pathological methods (PET blot), small alpha-synuclein aggregates in the synapses of cortical nerve cells can be shown as a dark reaction product. Bars=100 µm. Used: paraffin embedded tissue blot (PET-blot) as view from above without microscopic enlargement. PET-blot, antibody 4B12, same enlargement as b) (e20) (image provided by PD Dr Walter J Schulz-Schaeffer, Department of Neuropathology; University Medical Center Göttingen, Germany)

Treatment

Treatment of motor symptoms in Parkinson’s disease

Treatment of motor, psychological/psychiatric, and autonomous symptoms of Parkinson’s disease should be symptomatic, depending on the degree of clinical impairment and independently of a diagnosis of dementia with Lewy bodies or Parkinson’s disease dementia. Attention needs to be paid to the reduced response of motor symptoms, especially akinesis, to levodopa in 40% of patients with Lewy body dementia. Owing to the development of the dementia and the tendency to develop psychoses in dementia with Lewy bodies, monotherapy with levodopa is usually recommended. Studies of combination treatment with dopamine agonists and levodopa have not been conducted in patients with Lewy body dementia; whether combination treatment with dopamine agonists is useful and tolerable depends on the individual case. This requires consideration, especially bearing in mind the patient’s age (11). Close monitoring for possible psychotic symptoms is urgently advised. The administration of anticholinergic drugs is contraindicated.

Therapy for dementia

Patients with Lewy body dementia or Parkinson’s disease dementia have a pronounced cholinergic deficit. Acetylcholine is broken down in the brain by acetylcholinesterase and butyrylcholinesterase. Cholinesterase inhibitors (ChEI) inhibit different isoenzymes of the cholinesterases and increase the concentration of acetylcholine (which, owing to the disease, is low) in the synaptic gap. ChEI are effective in treating cognitive symptoms in dementia with Lewy bodies and Parkinson’s disease dementia. Additionally they reduce neuropsychiatric symptoms. By 2009, the only drug that was licensed in Germany for the treatment of Parkinson’s disease dementia was rivastigmine by oral administration (capsules); currently, no ChEI are licensed for dementia with Lewy bodies.

By contrast to other ChEI that are licensed for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease, rivastigmine inhibits not only isoenzymes of acetylcholinesterase but also those of butyrylcholinesterase. No clinical advantage of this principle of dual effectiveness has been shown. In a randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled, multicenter study of 541 patients with Parkinson’s disease dementia, the group that received treatment with an average of 8.6 mg of rivastigmine per day showed slight improvements in cognitive functioning, by 2.1 points in a scale of 0–70 of the ADAS-cog (a subtest of the Alzheimer’s disease assessment scale). The patients who had been treated with placebo underwent a slight deterioration, of a mean of 0.7 points. A clinically noticeable improvement was noted in 19.8% of patients who were treated with rivastigmine, but also in 14.5% of patients who had received placebo. 13% and 23.1%, however, deteriorated (P=0.007) (12). These values are mean group values of almost all therapeutic studies and do not mean that each single patient would have improved or, if given placebo, deteriorated. The extent to which cognitive improvements relevant for everyday life can be deduced for the individual case (or not) remains to be seen from longer studies investigating therapy over a longer term. In particular, the duration of treatment with rivastigmine in Parkinson’s disease dementia has not been studied under controlled conditions.

Adverse effects for rivastigmine (>5%) include nausea, vomiting, tremor, diarrhea, falls, vertigo/dizziness, and hypotension; rarely, hallucinations have been reported (4.7%).

Improved cognitive functioning has been shown for donepezil in patients with Parkinson’s disease dementia in few controlled trials with small case numbers, some of which were methodologically unsatisfactory (e13– e15).

Similar effects were shown for patients with Lewy body dementia, mainly in terms of a reduction in neuropsychiatric symptoms, especially hallucinations and productive-delusional symptoms (13, e16, e17). Formally, the use of rivastigmine and other ChEI in dementia with Lewy bodies is off-label in Germany. The use (even as an off-label treatment) of other antidementia drugs is not justified on the basis of current data. According to a comparative study, no differences in effectiveness exist for the 3 ChEI (rivastigmine, galantamine, and donepezil) in the treatment of Lewy body dementia if studies are of a comparable quality and size (e18).

In principle, cognition can be improved clinically noticeable and objectively by ChEI; often, everyday functioning is also improved, with fewer neuropsychiatric symptoms.

The question of how long treatment with ChEI should be continued is not unproblematic in view of the costs incurred and is currently the subject of critical discussion. In any case, the treatment should be controlled and evaluated 6 months after treatment initiation (this is also in accordance with the S3 guideline on dementia [14]). Cessation of treatment with ChEI should be decided on an individual as well as clinical basis. In case of progressive dementia and an MMSE score of less than 10 in spite of ChEI, the treatment needs to be questioned because no license exists in this scenario in Germany. Caution is indicated in abrupt cessation of treatment with ChEI because this entails the risk of substantial cognitive deterioration (15).

Treatment of hallucinations, delusions, and agitation

Visual hallucinations, delusions, and other productive-psychotic symptoms may occur early on in the disease course in dementia with Lewy bodies. In Parkinson’s disease, these often develop only during the course of the disease, and in a scenario where new hallucinations or psychoses occur for the first time after a change in medication, the most recent change in medication should be reversed (11). If this does not yield the desired success or if hallucinations occur without prior change of medication, the medication for Parkinson’s disease should be changed according to the treatment algorithm provided in the guidelines (figure 3).

Figure 3.

Algorithm for the treatment of psychosis (adapted from 11, 18); PDD, Parkinson’s disease dementia; DLB, dementia with Lewy bodies

If this does not improve the productive-psychotic symptoms to a satisfactory degree, the use of antipsychotics may be considered. This is particularly the case when (especially in patients with Parkinson’s disease) a reduction in the Parkinson medication is followed by a substantial deterioration in motor functioning, so that a minimum dose of levodopa is a definite requirement.

It is in particular the productive-psychotic symptoms of dementia with Lewy bodies and Parkinson’s disease dementia that place a heavy burden on relatives and carers; they are also responsible for a multitude of admissions to residential care homes, so that medication treatment is absolutely essential.

The raised sensitivity or intolerability of dementia with Lewy bodies vis-à-vis the typical antipsychotic drugs has been described repeatedly (16). By contrast, severe side effects in reaction to the atypical antipsychotic drug quetiapine (daily dosage 12.5–100 mg/d to a maximum of 200–300 mg/d) and clozapine (daily dosage 12.5–100 mg/d) have rarely been observed. Larger studies are lacking, and future studies should distinguish between dementia with Lewy bodies and Parkinson’s disease dementia. In a comparative study of 40 patients with Parkinson’s disease, both the group receiving quetiapine (mean dosage: 91 mg/day) and the group receiving clozapine (mean dosage: 26 mg/day) showed improvements of their psychotic symptoms without a deterioration of their Parkinson’s symptoms (e19). Rarely, the anticholinergic side effects increase confusion. It is important to start treatment with a very low dose—for example, 6.25 mg or 12.5 mg clozapine. Because of the risk of agranulocytosis during clozapine treatment, regular blood counts are essential. Other atypical antipsychotics are not recommended, and typical antipsychotics should not be used in patients with dementia with Lewy bodies and Parkinson’s disease dementia owing to their greater sensitivity to neuroleptic drugs. Especially treatment with typical neuroleptic drugs may increase the symptoms of Parkinson’s disease to a life threatening degree (to the extent of an akinetic crisis with massive swallowing impairment), to an impaired conscious level, and autonomic dysfunction, to the extent of a malignant neuroleptic syndrome with high mortality (16).

In acute situations, patients may be given a short course of clomethiazole and lorazepam (for the purpose of sedation) (17).

Key Messages.

Dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) should be considered as a differential diagnosis in patients with the following symptoms: if in additional to the central symptom dementia, one or two of the following symptoms are present: a fluctuating course, hallucinations, or symptoms of Parkinson’s disease.

Parkinson’s disease dementia (PDD) should be the suspected diagnosis in patients with Parkinson’s disease who develop cognitive deficits and/or hallucinations during the course of their illness.

Diagnostic measures include: FP-CIT and single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) or szintigraphy of the myocardium with 131-iodine metaiodobenzylguanidine (and in the individual case examination of cerebrospinal fluid) are useful in clinically unclear cases.

The treatment of choice for dementia with Lewy bodies and Parkinson’s disease dementia is a cholinesterase inhibitor (ChEI). ChEI are effective in dementia with Lewy bodies and Parkinson’s disease dementia; they do not only improve cognitive functioning but they also reduce productive-psychotic symptoms.

If visual hallucinations, delusions, or agitation develop, anticholergic medication should be stopped, dopamine agonists should be reduced stepwise, and levodopa treatment should be optimized. If required, treatment with atypical neuroleptics such as quetiapine or clozapine should be administered. For clozapine, patients require monitoring for possible side effects.

Acknowledgments

Translated from the original German by Dr Birte Twisselmann.

We thank Professor Dr Klaus Berger, Professor Dr Richard Dodel, and PD Dr J Walter Schulz-Schaeffer for their constructive support in compiling the manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

PD Dr Mollenhauer receives financial funding from the Michael J Fox Foundation, the American Parkinson Disease Association, and a Dr-Werner Jackstädt scholarship (Stifterverband für die Deutsche Wissenschaft) and is in receipt of research funds from TEVA Pharma. She has received travel funding from Boehringer Ingelheim and Novartis, as well as honoraria for speaking from GlaxoSmithKline und Bayer Schering Pharma.

Professor Förstl has received honoraria for speaking and advisory activities from Astra, Bayer, Cilag, Eisai, Eli, Janssen, Lilly, Lundbeck, Merz, Novartis, Pfizer, Schwabe, Zeneca, and others.

Professor Deuschl is a coauthor and the lead investigator of the Rivastigmine study (NEJM 351,24: 2505–18).

Professor Alexander Storch is a member of the editorial boards of Stem Cells, Stem Cells International, Open Biotechnology Journals, and European Neurological Journal. He has received study support from the Federal Ministry of Education and Research, the German Research Foundation, Roland-Ernst Foundation, Thyssen Foundation, International Parkinson Foundation, State Foundation Baden-Württemberg, and from Boehringer Ingelheim, Pfizer, and UCB Pharma. He has received honoraria for presentations or advisory board meetings from Cephalon, GE Health Care, Boehringer Ingelheim, GlaxoSmithKline, Valeant, Pfizer, Novartis, Orion, Solvay, TEVA, Lundbeck, und Schwarz/UCB Pharma.

Professor Wolfgang H Oertel has received honoraria for presentations or advisory board meetings from Boehringer Ingelheim, Cephalon, Desitin, Eisai, GE Health Care, GlaxoSmithKline, Meda, Merck-Serono, Neurosearch, Novartis, Orion, Pfizer, Schering-Plough, Solvay, TEVA/Lundbeck, and Schwarz/UCB Pharma.

Professor Trenkwalder has received honoraria for presentations or advisory board meetings from Cephalon, Boehringer Ingelheim, GlaxoSmithKline, Pfizer, Novartis, Solvay, TEVA, Lundbeck, and Schwarz/UCB Pharma, as well as study funding and honoraria for speaking from Novartis.

References

- 1.Bickel H. Dementia in advanced age: estimating incidence and health care costs. Z Gerontol Geriatr. 2001;34(2):108–115. doi: 10.1007/s003910170074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bostrom F, Jonsson L, Minthon L, Londos E. Patients with Lewy body dementia use more resources than those with Alzheimer’s disease. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;22(8):713–719. doi: 10.1002/gps.1738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zaccai J, McCracken C, Brayne C. A systematic review of prevalence and incidence studies of dementia with Lewy bodies. Age Ageing. 2005;34:561–566. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afi190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aarsland D, Perry R, Larsen JP, et al. Neuroleptic sensitivity in Parkinson’s disease and parkinsonian dementias. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66(5):633–637. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tiraboschi P, Hansen LA, Alford M, et al. Cholinergic dysfunction in diseases with Lewy bodies. Neurology. 2000;54(2):407–411. doi: 10.1212/wnl.54.2.407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nelson PT, Jicha GA, Kryscio RJ, et al. Low sensitivity in clinical diagnoses of dementia with Lewy bodies. J Neurol. 2009 doi: 10.1007/s00415-009-5324-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boeve BF, Silber MH, Ferman TJ, Lucas JA, Parisi JE. Association of REM sleep behavior disorder and neurodegenerative disease may reflect an underlying synucleinopathy. Mov Disord. 2001;16(4):622–630. doi: 10.1002/mds.1120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aarsland D, Ballard C, Larsen JP, McKeith I. A comparative study of psychiatric symptoms in dementia with Lewy bodies and Parkinson’s disease with and without dementia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2001;16(5):528–536. doi: 10.1002/gps.389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McKeith I, O’Brien J, Walker Z, et al. Sensitivity and specificity of dopamine transporter imaging with 123I-FP-CIT SPECT in dementia with Lewy bodies: a phase III, multicentre study. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6(4):305–313. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(07)70057-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mollenhauer B, Cepek L, Bibl M, et al. Tau protein, Abeta42 and S-100B protein in cerebrospinal fluid of patients with dementia with Lewy bodies. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2005;19(2-3):164–170. doi: 10.1159/000083178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eggert KM, Deuschl G, Gasser T. Leitlinien in der Neurologie Therapie-Parkinson-Syndrome. In: Diener HC, Putzki N, et al., editors. „Leitlinien für die Diagnostik und Therapie in der Neurologie“. 4th edition . Stuttgart: Georg Thieme Verlag; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Emre M, Aarsland D, Albanese A, et al. Rivastigmine for Dementia Associated with Parkinson’s Disease. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(24):2509–2518. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McKeith I, Del Ser T, Spano P, et al. Efficacy of rivastigmine in dementia with Lewy bodies: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled international study Lancet. 2000;356(9247):2031–2036. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)03399-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Deuschl G MW, et al. S3-Leitlinie Demenz; 2009. www.dgn.org/statement.html.

- 15.Minett TS, Thomas A, Wilkinson LM, et al. What happens when donepezil is suddenly withdrawn? An open label trial in dementia with Lewy bodies and Parkinson’s disease with dementia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2003;18(11):988–993. doi: 10.1002/gps.995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McKeith I, Fairbairn A, Perry R, Thompson P, Perry E. Neuroleptic sensitivity in patients with senile dementia of Lewy body type. BMJ. 1992;305(6855):673–678. doi: 10.1136/bmj.305.6855.673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tulloch JA, Ashwood TJ, Bateman DN, Woodhouse KW. A single-dose study of the pharmacodynamic effects of chlormethiazole, temazepam and placebo in elderly parkinsonian patients. Age Ageing. 1991;20(6):424–429. doi: 10.1093/ageing/20.6.424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Poewe W. When a Parkinson’s disease patient starts to hallucinate. Pract Neurol. 2008;8(4):238–241. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2008.152579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McKeith IG, Dickson DW, Lowe J, et al. Diagnosis and management of dementia with Lewy bodies: Third report of the DLB consortium. Neurology. 2005;65(12):1863–1872. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000187889.17253.b1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McKeith IG, Galasko D, Kosaka K, et al. Consensus guidelines for the clinical and pathologic diagnosis of dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB): report of the consortium on DLB international workshop. Neurology. 1996;47(5):1113–1124. doi: 10.1212/wnl.47.5.1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McKeith IG, Perry EK, Perry RH. Report of the second dementia with Lewy body international workshop: diagnosis and treatment. Consortium on Dementia with Lewy Bodies. Neurology. 1999;53(5):902–905. doi: 10.1212/wnl.53.5.902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Emre M, Aarsland D, Brown R, et al. Clinical diagnostic criteria for dementia associated with Parkinson Disease. Mov Disord. 2007;12:1689–1707. doi: 10.1002/mds.21507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e1.Knecht S, Berger K. Vascular factors contributing to the development of dementia .Einfluss vaskulärer Faktoren auf die Entwicklung einer Demenz] [Dtsch Arztebl. 2004;101(31-32):A 2185–A 2189. [Google Scholar]

- e2.Mok W, Chow TW, Zheng L, Mack WJ, Miller C. Clinicopathological concordance of dementia diagnoses by community versus tertiary care clinicians. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2004;19(3):161–165. doi: 10.1177/153331750401900309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e3.Aarsland D, Larsen JP, Karlsen K, Lim NG, Tandberg E. Mental symptoms in Parkinson’s disease are important contributors to caregiver distress. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1999;14(10):866–874. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e4.Emre M. Dementia associated with Parkinson’s disease. Lancet Neurol. 2003;2(4):229–237. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(03)00351-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e5.Aarsland D, Zaccai J, Brayne C. A systematic review of prevalence studies of dementia in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2005;20(10):1255–1263. doi: 10.1002/mds.20527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e6.Cummings JL. Intellectual impairment in Parkinson’s disease: clinical, pathologic, and biochemical correlates. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 1988;1(1):24–36. doi: 10.1177/089198878800100106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e7.Dubois B, Pillon B. Cognitive deficits in Parkinson’s disease. J Neurol. 1997;244(1):2–8. doi: 10.1007/pl00007725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e8.Stiasny-Kolster K, Doerr Y, Moller JC, et al. Combination of ’idiopathic’ REM sleep behaviour disorder and olfactory dysfunction as possible indicator for alpha-synucleinopathy demonstrated by dopamine transporter FP-CIT-SPECT. Brain. 2005;128(Pt 1):126–137. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e9.Werhahn KJ. Epilepsy in the elderly [Altersepilepsie] Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2009;106(9):135–142. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2009.0135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e10.Bonanni L, Thomas A, Tiraboschi P, Perfetti B, Varanese S, Onofrj M. EEG comparisons in early Alzheimer’s disease, dementia with Lewy bodies and Parkinson’s disease with dementia patients with a 2-year follow-up. Brain. 2008;131(Pt 3):690–705. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e11.Yoshita M, Taki J, Yokoyama K, et al. Value of 123I-MIBG radioactivity in the differential diagnosis of DLB from AD. Neurology. 2006;66(12):1850–1854. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000219640.59984.a7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e12.Gomez-Tortosa E, Gonzalo I, Fanjul S, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid markers in dementia with lewy bodies compared with Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 2003;60(9):1218–1222. doi: 10.1001/archneur.60.9.1218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e13.Aarsland D, Laake K, Larsen JP, Janvin C. Donepezil for cognitive impairment in Parkinson’s disease: a randomised controlled study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2002;72(6):708–712. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.72.6.708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e14.Putt ME, Ravina B. Randomized, placebo-controlled, parallel group versus crossover study designs for the study of dementia in Parkinson’s disease. Control Clin Trials. 2002;23(2):111–126. doi: 10.1016/s0197-2456(01)00207-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e15.Ravina B, Putt M, Siderowf A, et al. Donepezil for dementia in Parkinson’s disease: a randomised, double blind, placebo controlled, crossover study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2005;76(7):934–939. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2004.050682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e16.Beversdorf DQ, Warner JL, Davis RA, Sharma UK, Nagaraja HN, Scharre DW. Donepezil in the treatment of dementia with lewy bodies. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2004;12(5):542–544. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajgp.12.5.542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e17.Wild R, Pettit T, Burns A. Cholinesterase inhibitors for dementia with Lewy bodies. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;(3) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003672. CD003672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e18.Bhasin M, Rowan E, Edwards K, McKeith I. Cholinesterase inhibitors in dementia with Lewy bodies: a comparative analysis. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;22(9):890–895. doi: 10.1002/gps.1759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e19.Morgante L, Epifanio A, Spina E, et al. Quetiapine and clozapine in parkinsonian patients with dopaminergic psychosis. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2004;27(4):153–156. doi: 10.1097/01.wnf.0000136891.17006.ec. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e20.Kramer ML, Schulz-Schaeffer WJ. Presynaptic alpha-synuclein aggregates, not Lewy bodies, cause neurodegeneration in dementia with Lewy bodies. J Neurosci. 2007;27(6):1405–1410. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4564-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e21.Hughes AJ, Daniel SE, Kilford L, Lees A. Accuracy of clinical diagnosis of idiopathic Parkinson’s disease: a clinico-pathological study of 100 cases. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1992;55(3):181–184. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.55.3.181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]