Abstract

Individualized risk assessments during HIV testing are an integral component of prevention counseling, a currently recommended behavioral intervention for patients in high-risk settings. Additionally, aggregate risk assessment data are the source of aggregate behavioral statistics that inform prevention programs and allocation of resources. Consequently, inaccurate or incomplete risk behavior disclosure during test counseling may impact the efficacy of the counseling intervention, as well as bias aggregate behavioral statistics. To quantify client-reported accuracy during the risk assessment and identify barriers and facilitators to risk behavior disclosure, we interviewed young men accessing HIV testing services in a southeastern United States city using mixed methodology. Data were collected from August 2007 to April 2008. Based on data collected via an audio and computer-assisted self-interview (n = 203), over 30% of men reported that they were not accurate during the risk assessment. Participants reported numerous interpersonal facilitators to complete disclosure. During qualitative interviews (n = 25), participants revealed that many did not understand the purpose of the risk assessment. Findings suggest that risk assessments completed during HIV test counseling may be incomplete. Modifications to the risk assessment process, including better explaining the role of the risk assessment in prevention counseling, may increase the validity of the data.

Introduction

In the 1994 Counseling, Testing and Referral (CTR) guidelines for providers offering HIV testing, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) promoted use of a client-centered, prevention counseling model that has been demonstrated to reduce high-risk behaviors.1 During the pretest prevention counseling session, the counselor implements a personalized risk assessment in which the client is encouraged to disclose all past risk behaviors for HIV transmission. Based on the risk assessment, the counselor works with the client to develop a behavior change goal that will reduce the client's risk of acquiring HIV.2 In an effort to reduce barriers and routinize testing, the CDC removed the pretest counseling recommendation in the revised 2006 guidelines.3

Nonetheless, prevention counseling, which includes an individualized risk assessment, is “still strongly encouraged for persons at high risk for HIV in settings such as sexually transmitted disease (STD) clinics.”4 Although risk-based screening has limitations,5 risk assessments combined with risk reduction counseling have been suggested as more cost-effective in both identifying undiagnosed infections and preventing further transmission compared to routine opt-out testing.6,7 Additionally, the risk assessment provides data to examine risk behavior trends in the testing population.8,9 Even under the revised recommendations, the majority of federally funded CTR sites collect individual risk assessments on all patients testing for HIV, submitting quarterly reports to the CDC.10 Aggregated data at the state and national level monitor trends in the testing population and are used to evaluate CTR programs to ensure testing programs are reaching populations identified by state health departments as high-risk.11–14 In 2009, the CDC released quality assurance standards for CTR data collection in federally funded sites, which stressed the need for precise, reliable, valid, and complete data, including measures of patient's self-reported risk behaviors.14

Accuracy of the HIV counseling risk assessment

Few studies have attempted to quantify the accuracy of risk behavior disclosure during the HIV test counseling risk assessment. Previous research in North Carolina documented that young men newly diagnosed with HIV were more likely to accurately disclose the gender of their sexual partners during postdiagnosis partner notification and referral services interviews than during pretest counseling.15 Additional research has shown that STD clinic patients provide more or different information when completing an audio and computer-assisted self-interview (ACASI) than in clinician interviews16–18 suggesting that a face-to-face, counselor implemented HIV counseling risk assessment may also be incomplete.

Reasons for level of accuracy

Self-presentation bias (wishing to be viewed in a positive light) may result in patients underreporting behaviors they perceive to be stigmatizing.19 In a comparison of self-reports of sexual history from clinician interviews and ACASIs in an urban, public STD clinic, ACASI reports were more complete for “socially sensitive” behaviors, such as same gender sexual partners and illicit drug use. “Socially rewarded” behaviors, such as condom use and previous testing history, were more frequently reported in clinician interviews.16

Characteristics of the HIV test counselor may also influence client's accuracy. The theory of social influence, used primarily in counseling research, proposes that it is not only the message given during the therapy, but the client's perception of the counselor that influences effectiveness.20 Matched race/ethnicity and gender of the patient and counselor may allow for a better understanding of behavior motivations21 through shared cultural beliefs,22 language,23 and social experiences, as well as reduce fear of discrimination.16 Additionally, client's perceptions of trustworthiness and level of knowledge of the counselor may also impact success of the counseling session.20

Few studies have examined patient's racial and gender preferences for the counselor during HIV test counseling 24, 25 and none have examined the impact on risk behavior disclosure, nor the role of the counselor's age or sexual orientation. Additionally, there is little information on other possible barriers to complete risk behavior disclosure, such as anticipated response from the counselor (e.g., judgment) and perceived confidentiality.

As part of an ongoing investigation of the HIV epidemic in young men,26–29 the objectives of this study were to quantify young men's self-reported accuracy and comfort in the HIV counseling risk assessment and determine barriers and facilitators to complete risk behavior disclosure. This study was approved by University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Public Health-Nursing Institutional Review Board.

Methods

Study design

We conducted a cross-sectional survey of a convenience sample of English-speaking men aged 18–30 years who completed a pretest counseling session in a publicly funded STD clinic in North Carolina. We used an ACASI to gather quantitative data on risk behavior disclosure and barriers and facilitators to complete disclosure. Semistructured qualitative interviews with a sample of men completing the ACASI were used to triangulate and expand upon quantitative measures,30 exploring men's testing experiences in more depth.

Setting

Data were collected in an STD clinic in a local health department located in an urban county in central North Carolina. Based on aggregate CTR data, the local health department is comparable in terms of reported risk behaviors to the testing population in other publicly funded clinics in North Carolina. As the county has a higher proportion of minorities than other areas of the state, there are some demographic differences in the testing populations. On average, the local health department tests approximately 1200 men aged 18–30 each year, with a percent HIV positivity of less than 1.0%.

The local health department offers free walk-in HIV testing and all STD patients are offered HIV tests as part of a comprehensive examination. All clients accepting HIV testing are pretest counseled by a local health department staff member (an “HIV counselor”) trained in the state HIV counseling curriculum based on Project RESPECT,31 an intervention study that documented the effectiveness of HIV prevention counseling.32 A face-to-face risk assessment is completed during the counseling session that serves as the basis for individualized prevention counseling. The assessment is documented, sent to the North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services (NCDHHS) and entered into the CTR database. After consent is obtained, a blood sample is drawn and sent to the state laboratory for antibody testing, as well as acute HIV screening.33 HIV test results are provided in person approximately 2 weeks after the pretest counseling session. During the data collection period, there were two HIV test counselors at the local health department, both of similar demographics (Caucasian females, mid 30s). STD examinations were completed separately by medical providers.

ACASI

Data collection

Clinic clients meeting the eligibility criteria (men, aged 18–30 and English speaking who had an HIV test that day) were read a recruitment script by a local health department staff member at the completion of the HIV pretest counseling session. To calculate response rates, local health department staff provided aggregate counts of men meeting the eligibility criteria each day of data collection.

Men agreeing to participate met with the study interviewer in a private room within the clinic. To allow the survey to be anonymous, a waiver of signed consent was obtained and men verbally consented to participate. Participants completed an ACASI on a laptop using Questionnaire Development System (QDSTM) software (NOVA Research Company, Bethesda, MD). The survey had been pretested, revised, and was at less than a fifth-grade reading level. All participants completed noninvasive practice questions with the study interviewer prior to self-administration to ensure client comfort with the laptop and mouse, program, and question format. ACASI questions focused on participant's comfort and accuracy during the risk assessment with specific questions on risk behaviors for HIV infection. Risk behaviors were selected for overlap with the CTR surveillance form (gender of sexual partners and drug use) and other key HIV risk factors: number of sexual partners,34 condom use,35 and type of sex (anal, vaginal, and oral).36 Additional information was gathered on client demographics, risk behaviors, and preferences for counselor characteristics. All men completed the ACASI on the day of their pretest counseling session, so their test results were not requested. Men completing the ACASI were compensated with a $10 gift card to a local grocery store.

Analysis

We report descriptive statistics of participant-reported levels of accuracy and comfort during the risk assessment, facilitators and barriers to risk behavior disclosure and preferences for counselor characteristics. Additionally, we investigate if preference for counselor characteristics varied by client demographics. We report participant demographics and opinions stratified by level of reported accuracy during the risk assessment, using Pearson χ2 tests. When expected cell counts were less than 5, exact χ2 statistics were used.37 Data analysis was completed in SAS version 9.13 (SAS Corporation, Cary, NC).

Qualitative interviews

Data collection

A subsample of men completing the ACASI was recruited for one-on-one qualitative interviews. We used purposeful sampling38 to oversample men expressing less than complete comfort and/or accuracy during the ACASI. Initially all men completing the ACASI were recruited to participate; the final screen on the ACASI contained a recruitment script for participation in the qualitative portion of the study. After 10 qualitative interviewers, we reviewed participant characteristics as reported on their ACASI. As we had more participation from men who expressed complete comfort and accuracy during the risk assessment, we revised the recruitment selection criteria to oversample men expressing less than complete comfort and/or accuracy. Clients recruited were given the option to complete the interview immediately or return within the next week.

Using a semistructured interview guide, clients were asked open-ended questions by a single female study researcher. Interview questions focused on participant's experience with the HIV counseling session, accuracy and comfort during the risk assessment, and barriers to risk behavior disclosure, including preference for concordance in test counselor demographics. Although these key constructs remained consistent throughout the data collection period, continuous reviews of memos kept by the study interviewer during the data collection were used to modify and finesse the interview guide, including development of additional prompts. Interviews were digitally audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. All men completing the qualitative interview were provided a $40 gift card to a local grocery store.

Analysis

We used constant comparative analysis, reviewing transcribed interviews one at a time and comparing with others to conceptualize relations between the data.39 All narratives were first topically coded using deductive constructs outlined in the interview guide. To develop themes within constructs, we used inductive coding with the development of the codebook documented in an ongoing memo. Coding was primarily conducted by one researcher using ATLAS.ti v.5.2. (Scientific Software Development GmbH, Berlin, Germany). A second primary investigator coded a random sample of interviews (15%) and discrepancies in coding were discussed and analysis refined where relevant. The research team periodically reviewed code reports of relevant passages to identify emerging themes within and between constructs. Final thematic findings were triangulated with quantitative measures in the ACASI to identify areas of corroboration and contradiction,40 as well as additional barriers not captured in the ACASI.

Results

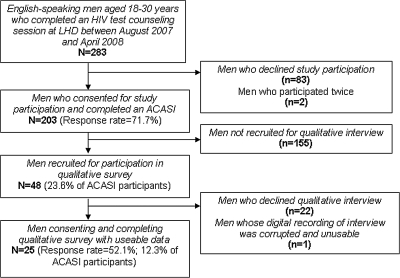

Data collection was completed between August 2007 and April 2008. Two hundred eighty-three men were recruited and 205 agreed to participate in the study, consented, and completed the ACASI (a response rate of 71.7%). Two men participated twice and their duplicate interviews were removed, resulting in a final sample of 203 (Fig. 1). Due to confidentiality, we were not provided demographics of men who refused participation. When study participants were compared in demographics to a similar testing population at the local health department during the same time period, there were some differences (Table 1). The testing population at the local health department had a larger percent of men of “other” race compared to the study population,19.4% versus 5.4%, a difference of 14.0% (95% confidence interval: 9.9%–18.1%). The “other” race category includes Hispanics and the difference was likely due to the study language inclusion criteria. There also appeared to be some differences in risk behaviors, which could be due in part to the different modes of risk assessment (local health department counseling session versus research study ACASI).

FIG. 1.

Study sample selection.

Table 1.

Demographics of Men Aged 18–30 Testing for HIV Between August 2007 and April 2008, North Carolina

| |

|

|

Study participants |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men testing in NCDHHS clinic n = 17,142 | Men testing at LHD n = 892 | Men completing ACASI n = 203 | Men completing qualitative interview n = 25 | |

| Age | ||||

| 18–21 | 6034 (35.2%) | 289 (32.4%) | 82 (40.4%) | 7 (28.0%) |

| 22–25 | 6182 (36.1%) | 308 (34.5%) | 66 (32.5%) | 11 (44.0%) |

| 26–30 | 4926 (28.7%) | 295 (33.1%) | 55 (27.1%) | 7 (28.0%) |

| Race | ||||

| White | 4602 (26.8%) | 61 (6.8%) | 11 (5.4%) | 2 (8.0%) |

| African American | 9186 (53.6%) | 653 (73.2%) | 179 (88.2%) | 21 (84.0%) |

| Other | 2316 (13.5%) | 173 (19.4%) | 11 (5.4%) | 2 (8.0%) |

| Missing | 1038 (6.1%) | 5 (0.6%) | 2 (1.0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Previous HIV test | ||||

| Yes | 10120 (59.0%) | 581 (65.1%) | 147 (72.4%) | 18 (72.0%) |

| No | 6702 (39.1%) | 308 (34.5%) | 56 (27.3%) | 7 (28.0%) |

| Missing | 320 (1.9%) | 3 (0.3%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Injection drug use | ||||

| Yes | 297 (1.7%) | 4 (0.4%) | 8 (3.9%) | 1 (4.0%) |

| No | 16,845 (98.3%) | 888 (99.6%) | 195 (96.1%) | 24 (96.0%) |

| Sexual partnersa | ||||

| Male | 1493 (8.7%) | 80 (9.0%) | 19 (9.4%) | 2 (8.0%) |

| Female | 14789 (86.3%) | 819 (91.8%) | 182 (89.7%) | 22 (88.0%) |

| Male and female | 546 (3.2%) | 18 (2.0%) | 8 (4.0%) | 0 (0%) |

| No sex | 491 (2.9%) | 11 (1.2%) | 5 (2.5%) | 1 (4.0%) |

| Missing | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.5%) | 0 (0%) |

Not mutually exclusive; Last year for all NCDHHS and all DCHD clients; last 6 months for study participants.

NCDHHS; North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services; LHD, Local health department; ACASI, Audio and computer-assisted self-interview.

The majority of men participating in the study self-identified as African American (88.2%), had a high school diploma or more (81.3%) and had previously been tested for HIV (72.4%). Only 10 men (3.5%) were there exclusively for an HIV test and the majority of men reported their primary motivation for the visit was that they had symptoms of an STD (39.9%). Primary reasons for choosing to visit the local health department were because they “knew it was free” (36.0%) and that they had “been here before” (19.2%). Drug use was prevalent (68.8%) with the majority attributed to marijuana. No item on the ACASI was missing more than 3%.

Forty-eight of the men completing the ACASI were recruited for the qualitative interview and 26 (54.2%) agreed, consented, and participated. The digital recording of one interview was corrupted, resulting in a sample size of 25 (Fig. 1). There were no demographic differences between men participating in the qualitative interviews and non-responders. Purposeful sampling provided a sample that reported slightly lower levels of complete comfort during the risk assessment compared to the full study population (56.1% versus 61.6%). Interviews lasted between 35 and 65 minutes.

Comfort and accuracy during the risk assessment

During the ACASI, all of the men reported completing a risk assessment with an HIV test counselor. Almost 80% discussed all five key behaviors measured on the ACASI and 97% discussed three or more of the behaviors. Type of sex (vaginal, anal, or oral) was least frequently discussed during the prevention counseling session with the main reason reported that the “counselor didn't ask” about it. Overall, the majority of men reported that they were “completely comfortable” and told their test counselor “everything” during the risk assessment (Table 2). Still, over 30% reported not fully disclosing risk behaviors during the assessment. Level of disclosure and comfort in discussing specific risk behaviors varied, with men reporting lowest levels of comfort and accuracy for answering questions about the type of sex they had (among those who discussed it with their counselor).

Table 2.

Reported Comfort and Accuracy in Discussing Risk Behaviors During HIV Test Counseling, Among Men Aged 18–30 Accessing Services at a Publicly Funded Clinic, North Carolina (n = 203)

| |

|

Comfort in discussing risk behaviors |

Level of disclosure of risk behaviors |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Discussed behavior | Not at all | Somewhat | Completely | Nothing | Some things | Everything | |

| Overall | — | 7 (3.4%) | 71 (35.0 %) | 125 (61.6%) | 7 (3.4%) | 60 (29.6%) | 136 (67.0%) |

| Specific behaviors | |||||||

| Drug use | 185 (91.1%) | 2 (1.1%) | 37 (20.0%) | 145 (78.4%) | 8 (4.3%) | 40 (21.6%) | 138 (74.6%) |

| Type of sex (vaginal, anal or oral) | 179 (88.2%) | 2 (1.1%) | 56 (31.3%) | 121 (67.6%) | 2 (1.1%) | 48 (26.8%) | 127 (70.9%) |

| Condom use | 196 (96.6%) | 0 (0%) | 41 (20.9%) | 155 (79.1%) | 2 (1.0%) | 48 (24.5%) | 146 (74.4%) |

| Gender of sex partners | 199 (98.0%) | 3 (1.5%) | 34 (17.1%) | 162 (81.4%) | 6 (3.0%) | 29 (14.6%) | 162 (81.4%) |

| Number of sex partners | 191 (94.1%) | 3 (1.6%) | 40 (20.9%) | 147 (77.0%) | 1 (0.5%) | 45 (23.6%) | 143 (74.9%) |

There were few client demographics associated with self-reported level of accuracy during the risk assessment (Table 3). Men who reported nonheterosexual behaviors were more likely to not fully disclose all of their risks, and comfort with their own sexual orientation was associated with full disclosure. Education level was associated with level of accuracy; 50% of men with less than a high school education reported an incomplete risk assessment compared to 72.5% of men with a high school diploma (p = 0.04). Men who reported complete comfort in discussing risk behaviors with the test counselor were more likely than men who were not completely comfortable to report full risk behavior disclosure (p < 0.01).

Table 3.

Characteristics of Men, 18–30 by Reported Level of Disclosure of Risk Behaviors During HIV Test Counseling in a Publicly Funded Clinic, North Carolina (n = 203)

|

Not completely accurate n = 67 |

Completely accurate n = 136 |

p Valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Type of visit | |||

| HIV test only | 5 (3.7%) | 65 (97.0%) | 1.0 |

| STD examination + HIV test | 2 (3.0%) | 131 (96.3%) | |

| Age | |||

| 18–21 | 24 (35.8%) | 58 (42.7%) | |

| 22–25 | 23 (34.3%) | 43 (31.6%) | 0.65 |

| 26–30 | 20 (29.9%) | 35 (25.7%) | |

| Race | |||

| African American | 59 (89.4%) | 120 (88.9%) | 1.0 |

| Non-African American | 7 (10.6%) | 15 (11.1%) | |

| Education | |||

| Did not complete high school | 19 (28.4%) | 19 (14.0%) | |

| High school diploma/GED | 22 (32.8%) | 58 (42.7%) | 0.04 |

| More than high school | 26 (38.8%) | 59 (43.4%) | |

| Previous test | |||

| Yes, at local health department | 27 (40.3%) | 70 (51.5%) | |

| Yes, not at local health department | 23 (34.3%) | 27 (19.9%) | 0.08 |

| No | 17 (25.4%) | 39 (28.7%) | |

| Any drug use | |||

| Yes | 48 (71.6%) | 91 (66.9%) | 0.52 |

| No | 19 (28.4%) | 45 (33.1%) | |

| Injection drug use | |||

| Yes | 6 (9.0%) | 2 (1.5%) | 0.02 |

| No | 61 (91.0%) | 134 (98.5%) | |

| Non-heterosexual behaviorb | |||

| Yes | 10 (15.6%) | 9 (6.7%) | 0.07 |

| No | 54 (84.4%) | 125 (93.3%) | |

| Sexual orientationc | |||

| Heterosexual | 56 (84.9%) | 125 (91.1%) | 0.14 |

| Not heterosexual | 10 (15.1%) | 11 (8.1%) | |

| Comfort with sexual orientation | |||

| Completely | 51 (76.1%) | 125 (92.6%) | <0.01 |

| Not completely | 16 (23.9%) | 10 (7.4%) | |

| Comfort during risk assessment | |||

| Completely | 30 (44.8%) | 95 (69.9%) | <0.01 |

| Not completely | 37 (55.2%) | 41 (30.2%) | |

Pearson exact χ2.

Based on reported gender of sex partners in last 6 months.

Client identified sexual orientation.

Barriers to comfort and accuracy

Among men who reported fully disclosing their risk behaviors to the counselor during the ACASI (n = 136), the majority (47.1%) attributed their accuracy to the counselor's characteristics; including perceived trust, level of caring and a lack of judgment (Table 4). Among men who provided incomplete information during the assessment (n = 67), the majority reported intrapersonal barriers, such as embarrassment and unwillingness to disclose personal information.

Table 4.

Reported Reasons for Level of Accuracy in Risk Assessment During HIV Test Counseling, Men Aged 18–30 Accessing Services at a Publicly Funded Clinic, North Carolina (n = 203).

| Facilitators for full disclosurea | |

| I knew the information would be kept confidential | 42 (30.9%) |

| I trusted him/her | 25 (18.4%) |

| He/she seems to really care | 21 (15.4%) |

| I didn't feel like he/she was judging me | 18 (13.2%) |

| He/she asked | 16 (11.8%) |

| Other | 14 (10.3%) |

| Barriers to full disclosureb | |

| I was embarrassed | 27 (40.3%) |

| It's none of his/her business | 12 (17.9%) |

| Other | 10 (14.9%) |

| He/she wouldn't understand | 6 (9.0%) |

| I thought he/she would judge me | 5 (7.5%) |

| I didn't trust him/her | 3 (4.5%) |

| I didn't think it would be kept confidential | 2 (3.0%) |

| Missing | 2 (3.0%) |

Among men reporting complete accuracy (n = 136).

Among men reported less than complete accuracy (n = 67).

Similar to the quantitative measures of facilitators to full risk behavior disclosure, men discussed the importance of their perception of test counselor including her personality and level of caring during the one-on-one interviews.

And the [test counselor], she was cool, but it was a professional cool, you know, where I wouldn't feel condemned or damned for talking to her. I felt like she was genuine and really cared about me as a patient. I don't know if that was a therapeutic thing that she was pulling or … I felt like I could talk to her, like I could be easy with her.

—24 year old, African American

Men also reported that how the counselor asked the questions during the risk assessment related to their comfort and the accuracy of their responses. Some men preferred a straightforward list of questions, while others felt that the standardized measures made the counseling feel less individualized.

… they ask you straight up, like … how many partners you've had, have you used unprotected sex … when the last time you had unprotected sex … and I think by them asking you straightforward like that … they get a lot of straightforward answers … .

—25 year old, African American

It felt like scripted … .like she had a set of questions she had to say, her little spiel about HIV and once she was done that was it. It wasn't like … it wasn't like … the whole thing wasn't made to make me feel comfortable.

—22 year old, African American

Additionally a few of the men stated that their main reason for disclosing their behaviors during the counseling session was that they felt like it was important in order to be treated appropriately. One participant who reported during the ACASI survey that he was completely accurate explained:

Well, they can't fix you if they don't know everything that's wrong. And withholding information is not going to help if you're trying to get something fixed.

—24 year old, African American

In the quantitative portion of the study, the prevalence of self-reported complete disclosure was higher among men who said they had previously been tested in a publicly funded clinic compared to men with no previous test (88.6% versus 69.4%). Similar trends were seen in the qualitative data, as some men reported that the first time they tested they were more likely to provide incomplete risk data. As explained by one participant who had tested at the local health department multiple times:

The first time [testing] … you might be a little tempted to lie or leave some stuff out …

—23 year old, African American

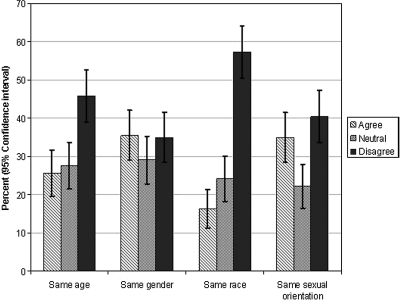

Matching to test counselor demographics

In the ACASI, most men disagreed that it would be easier to talk about risk behaviors if they had a counselor matched to their demographics (Fig. 2). Only 33 men (16.3%) said having a counselor of the same race would increase comfort and only a quarter of men preferred a counselor that was their age. When we examined preferences for matching by client characteristics, men who reported nonheterosexual orientation were more likely to want a counselor of the same sexual orientation than men with heterosexual orientation (61.9% versus 32.8%, p = 0.01).

FIG. 2.

Reported preferences for characteristics of HIV test counselor to make it easier to discuss risk behaviors, men aged 18–30, North Carolina (n = 203).

Similarly in the qualitative interviews, the majority of men interviewed stated that having a counselor matched to their race, gender or sexual orientation would not affect their comfort and accuracy during the counseling session.

Race doesn't matter to me. I don't think it really matters to me … everyone is the same, so … it wouldn't make a difference. It wouldn't make it more comfortable or uncomfortable.

—20 year old, Caucasian

I look at the counselor as, I'm not looking at their race or their, uh, gender. I'm looking at them to get an answer, cause I know they have rules and regulations also within the clinic. So I trust them.

—26 year old, African American

Furthermore, a few men articulated that the counselor's experience and/or personality would trump the effect of matched physical characteristics.

You know, black, white, green, or yellow. It doesn't … really, you know, as long as we can talk civilized, I would say. You know, and talk with an educated mind.

—29 year old, African American

Only a few participants stated that sharing the demographics of their counselor would increase comfort due to shared understanding.

… even though race shouldn't be a factor in this, but we have to be realistic … it is. And most people feel more comfortable and more open, you know to speak on stuff with people they feel like is a part of them, in a certain way you know.

—23 year old, African American

A few men mentioned that having a counselor who looked like them would increase the likelihood that they knew each other which would thus be a barrier to disclosure.

I'd rather have somebody that's different, different race or something. Somebody that I've never seen before … because it's like they don't know you, you know what I'm saying? That's not good … I don't need that. I'd rather have somebody of another race.

—24 year old, African American

In the ACASI the majority of men disagreed that having a counselor of the same age would increase comfort; however, preference for age of the counselor was split evenly in the qualitative interviews. About half of the participants did not want to talk to a counselor who was much older than them, preferring to talk to someone closer to their age.

Have I ever lied? Yeah, I lied when they had the little 78-year-old dude in there asking me questions, but you know … I still pretty much gave the same stuff, but on some of the questions he was asking me like “how many sex partners have you had in the last 60 days” or something like that. And I was like “one” you know because I know he knows that I was married, so I didn't want to tell him that. That's about the only thing that really made me feel uncomfortable was the age.

—24 year old, African American

Um, it's like … I don't really like talking to older adults like that. It's like, you know, I feel they give you this look like, a down look, like “you shouldn't be doing stuff like that.” I don't know, I guess if it was like somebody my age was in there, or something like I'd kind of feel more comfortable.

—21 year old, African American

The men who preferred a counselor who was not their age related it to the likelihood of seeing the person outside of the clinic or to their general comfort in discussing risks with someone their age:

… I personally would feel more comfortable talking to an older person than closer to my age that I would probably run into some where

—23 year old, African American

I would say, somebody older is easier … um I guess somebody around your age is going to be more judgmental.

—25 year old, African American

Risk assessment process

Not originally hypothesized as a barrier to risk behavior disclosure during the risk assessment and not measured in the ACASI, a theme that emerged from the qualitative interviews was that many men did not understand the risk assessment portion of the pretest counseling. When probed on why they were asked questions about their risk behaviors, no respondent reported a personal benefit. Although when asked about reasons for accuracy one respondent indirectly referenced the role of the risk assessment in prevention counseling:

I feel like … if she doesn't know everything and if I hide something then that could hurt me down later on in life … like she could be giving me advice on something I may already know or I may already be doing, but I said I wasn't doing it

—21 year old, mixed heritage

The majority of participants either did not know why the risk assessment questions were asked or suggested that the information was for general statistics or was just of interest to the HIV counselor:

… that's the reason why she probably asked that … to get a … to educate herself probably on like, what guys my age are actually doing.

—23 year old, African American

I believe that is probably used more for statistics like to show certain behaviors that may lend more easily to becoming infected so yes it's very important for research purposes.

—26 year old, African American

Men who received a physical STD examination in addition to the HIV test reported that two risk assessments were completed, one by the STD medical provider and one by the HIV counselor. Men expressed frustration at having to answer the same risk behavior questions twice, not understanding the purpose of multiple assessments.

Yeah! Very private questions and after a while you get kind of tired of answering the same questions. You'll be like “can you just pass the sheet to the next person so they know what's going on.” Cause, like, ok, I'm answering all these questions, but where is the information going. Cause obviously it's not going to the next person.

—22 year old, African American

I mean the person you already got comfortable with … now you gotta go and transition to looking at a whole new face … it should be like, one person … drawing the blood and everything.

—24 year old, African American

… besides … it's probably to catch somebody, catch you somewhere.

Interviewer: Catch you?

In a lie.

—20 year old, African American

Alternatives methods for risk assessment

During the qualitative interviews, participants were asked how the risk assessment could be improved to increase accuracy. Some men spoke to how the test counselor should ask the questions, as mentioned above. Interestingly, no participants suggested not collecting risk data, but some men suggested alternate ways of documenting their behaviors during the visit. Men proposed that answering questions on a laptop would be preferable for perceived confidentiality, improved accuracy and to decrease the amount of time spent in the clinic.

I mean the questions have to be asked, so there's really no way … unless it was on a computer screen … and that may help. … I know myself … I feel more comfortable answering the questions on a computer screen then actually telling someone … you know … someone asking me these questions face to face … yeah … well, the laptop does well.

—29 year old, African American

Two men suggested that to increase accuracy the risk assessment should be self-administered, but could be completed on a sheet of paper. One participant compared this method of administering the risk assessment to how information is collected during other health examinations, such as visits to a doctor's office.

Um … the questions I guess, when they get into the details about oral, anal … all that … .Cause I think a lot people do lie when they are asked the question … I think it is more truthful if you are actually writing them down.

—25 year old, African American

The uncomfortable part, I guess, of actually somebody you don't know asking you personal questions. That's taken out. You just answer them, like a survey I guess. It's basically like if you go to the doctor and you gotta … if it's your first time at the doctor's office, they ask you about your past, your medical history and are you at risk, are people in your family have this thing. That's how I see it … .then I can just check off like “yes, yes, no, no.”

—25 year old, African American

Discussion

In this mixed methods study, we investigated the accuracy of the risk assessment during the HIV test counseling session as reported by young men accessing services in a publicly funded STD clinic in North Carolina. Approximately a third of the men in the sample reported that they did not disclose all of their risk behaviors to the HIV counselor during the face-to-face risk assessment. These results echo similar studies of risk disclosure to medical providers.16,18,41 Although a previous analysis documented inaccuracies in the CTR surveillance database for HIV positive young men,15 this is the first to document likely CTR inaccuracies among the broader testing population of young men, the majority of whom were likely HIV negative based on the local health department's average percent positivity.

Accuracy level in the risk assessment was associated with few client demographics. In this study, men with less education were more likely to not fully disclose risks. Lower education levels may be a marker for distrust in health care providers,42 which in turn may affect disclosure level. Intrapersonal characteristics, such as comfort with sexual orientation, were associated with higher levels of accuracy suggesting that there are nonclinic related factors impacting disclosure.

This study furthers the discussion on the accuracy of the risk assessment by elucidating barriers to complete risk behavior disclosure. Captured in both the quantitative and qualitative data, participants reported numerous interpersonal facilitators to complete disclosure. Perceptions of the counselor as non-judgmental and as truly “caring” about the client appeared to increase comfort more than concordant counselor demographics. Only a minority of men stated their comfort would increase when speaking to a counselor with concordant race, gender or sexual orientation, although matching of sexual orientation may be important for clients identifying as nonheterosexual. While not triangulated clearly across the ACASI and qualitative interviews, the age of the counselor seemed influential in decisions about disclosing behaviors for some men. These findings support prior research on race and gender matching24,25,43,44 and newly document that the age and perceived sexual orientation of the counselor may affect comfort for some clients. These additional measures should be included in future assessments of clients' preferences for counselors; however, based on research to date there is no clear indication for standardized counselor matching by demographics. As suggested in both the qualitative and quantitative measures in this study, a perception that the counselor is well-trained and compassionate may influence accurate disclosure more than concordant demographics.

When asked about the purpose of the risk assessment, some men in the qualitative portion of the study articulated population-level benefits (e.g., accurate statistics), but participants did not understand that the risk assessment was being used as part of individualized prevention counseling. In reviews of risk behavior disclosure on surveys, participants with a self-interest are more likely to provide honest answers.19 In this study, not understanding the individual benefit may have resulted in a less than accurate risk assessment. Additionally, in the context of an STD exam, men reported having multiple risk assessment by multiple providers. For these men, they were forced to answer similar questions twice without understanding the purpose. To help maximize accurate responses, part of the counseling session should include an explicit explanation by the counselor of the purpose of the risk assessment, including both individual and population-level benefits.

Barriers and facilitators to risk behavior disclosure are complex. Our use of a mixed methods approach, collecting quantitative and qualitative data simultaneously allowed us to examine the primary research questions from different perspectives and overcome limitations of each of the methods.40,45 By triangulating between data sources, we were able to cross-validate findings, seeking convergence to strengthen credibility and contradiction to generate future research questions.30,45 A mixed methods approach also increased our scope of inquiry as the qualitative data allowed us to expand on barriers to risk behavior disclosure not captured quantitatively.30

Still, there are several limitations to this study. The sample was limited to English speaking young men testing in one clinic in North Carolina and the results may not be generalizable to other testing populations, such as women, older populations and clients accessing testing services outside of publicly funded clinics or in other parts of the country. We identified some differences in our study sample compared to the larger population of men accessing services in publicly funded clinics in North Carolina (Table 1), suggesting that our findings may not be generalizable across other clinics in the state. We were not able to quantify differences in recruited men selecting not to participate in the ACASI. Our study population appeared similar to aggregate demographics of young men testing in the local health department during the data collection period; however, they may have differed on nonmeasured characteristics, such as socioeconomic status. Our qualitative sample only included a portion of men completing the ACASI. The sample was purposeful as we tried to oversample men who reported as being not completely comfortable discussing risk behaviors. Furthermore, we did not have data on men not accessing care in the clinic, of which a portion might be the most uncomfortable and/or inclined to be inaccurate during their risk assessment.

The data collected were based on participants' self-report of accuracy and comfort. Although we used an ACASI, thought to increase validity when measuring sensitive information, it is possible that social desirability bias influenced men's answers. Additionally, qualitative interviews were completed by a single, Caucasian female study researcher which may have influenced participants' responses, specifically regarding preferences for counselor characteristics, although triangulation with the self-administered questionnaire helped increase credibility.40

It is possible that the accuracy of the risk assessment depends in part on the counselor's skill and ability to properly implement the prevention counseling curriculum. Unfortunately we did not observe the counseling sessions and are not able to assess this. Although Project RESPECT, a randomized control trial, showed prevention counseling to be effective in reducing risk behaviors among uninfected patients, few observational studies have been able to replicate those results.46 It is possible that the discordance in findings is due to improper implementation of the prevention counseling curriculum and research suggests that CTR sites may not fully implement the CTR guidelines.47 In a study of 30 publicly-funded clinics in Pennsylvania, researchers used participant actors to evaluate staff-client interaction.48 While almost 90% of providers conducted a risk assessment, only 43% discussed changing behaviors with their clients. Still, the test counselors at the local health department had both been trained in the state curriculum and represent a “real world” application of prevention counseling in North Carolina CTR facilities.

Findings from this study suggest that in a sample of young men accessing HIV testing services in a publicly funded clinic, the risk assessment completed during HIV test counseling may be incomplete, which may have implications for both the efficacy of individual prevention counseling and the interpretation of aggregate behavioral statistics. If the risk assessment continues to be used by CTR programs, alternative methods may be more appropriate to obtain accurate data. As suggested by study participants, ACASI or paper-based assessments may increase accuracy through decreased embarrassment, as well as having time to answer questions thoughtfully. In a recent feasibility study, Cohall and colleagues showed that an ACASI risk assessment as part of the HIV counseling session was acceptable to patients in a community setting.49 ACASI assessments may also streamline the testing process allowing more time for health education and targeted risk reduction by a trained counselor. Additionally, changes in the test counseling risk assessment process, including simply explaining the purpose of the risk assessment may help increase perceived benefit of complete risk behavior disclosure.

Acknowledgments

This research was support in part by grant #P30 AI50410 from the University of North Carolina Center for AIDS Research. This study could not have been possible without the young men who shared their thoughts and opinions. We thank the staff at the Durham County Health Department, especially the HIV counselors, for their assistance in recruiting participants.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.CDC. HIV Counseling Testing And Referral: Standards And Guidelines. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sikkema KJ. Bissett RT. Concepts, goals, and techniques of counseling: Review and implications for HIV counseling and testing. AIDS Educ Prev. 1997;9(3 Suppl):14–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Branson BM. Handsfield HH. Lampe MA. Janssen RS. Taylor AW. Lyss SB. Clark JE Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Revised recommendations for HIV testing of adults, adolescents, and pregnant women in health-care settings. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2006;55 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Questions and Answers for Professional Partners: Revised Recommendations for HIV Testing of Adults, Adolescents and Pregnant Women in Healthcare Settings. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/testing/resources/qa/qa_professional.htm. [Feb 4;2009 ]. www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/testing/resources/qa/qa_professional.htm

- 5.Duffus WA. Weis K. Kettinger L. Stephens T. Albrecht H. Gibson JJ. Risk-based HIV testing in South Carolina health care settings failed to identify the majority of infected individuals. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2009;23:339–345. doi: 10.1089/apc.2008.0193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Holtgrave DR. Costs and consequences of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's recommendations for opt-out HIV testing. PLoS Med. 2007;4:e194. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mehta SD. Hall J. Greenwald JL. Cranston K. Skolnik PR. Patient risks, outcomes, and costs of voluntary HIV testing at five testing sites within a medical center. Public Health Rep. 2008;123:608–617. doi: 10.1177/003335490812300511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.CDC. HIV counseling and testing at CDC-supported sites, United States, 1999–2004. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weber JT. Frey RL., Jr. Horsley R. Gwinn ML. Publicly funded HIV counseling and testing in the United States, 1992–1995. AIDS Educ Prev. 1997;9(3 Suppl):79–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.CDC. HIV Testing Form and Variables Manual. Alanta, GA: Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Holtgrave DR. DiFranceisco W. Reiser WJ, et al. Setting standards for the Wisconsin HIV Counseling and Testing Program: An application of threshold analysis. J Public Health Manag Pract. 1997;3:42–49. doi: 10.1097/00124784-199709000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Holtgrave DR. Reiser WJ. Di Franceisco W. The evaluation of HIV counseling-and-testing services: Making the most of limited resources. AIDS Educ Prev. 1997;9(3 Suppl):105–118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Self-assessment Tool for State and Territorial Health Departments HIV Counseling, Testing and Referral Services. 2008. www.nastad.org/Docs/Public/Publication/2006216_CTRNeesdAss.pdf. [May 22;2010 ]. www.nastad.org/Docs/Public/Publication/2006216_CTRNeesdAss.pdf

- 14.CDC. 2009 Quality Assurance Standards for HIV Counseling, Testing, and Referral Data. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Torrone EA. Thomas JC. Kaufman JS. Pettifor AE. Leone PA. Hightow-Wiedman LB. Glen or Glenda: Reported gender of sex partners in two statewide HIV databases. Am J Public Health. 2010;100:525–530. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.162552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kurth AE. Martin DP. Golden MR, et al. A comparison between audio computer-assisted self-interviews and clinician interviews for obtaining the sexual history. Sex Transm Dis. 2004;31:719–726. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000145855.36181.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rogers SM. Willis G. Al-Tayyib A, et al. Audio computer assisted interviewing to measure HIV risk behaviours in a clinic population. Sex Transm Infect. 2005;81:501–507. doi: 10.1136/sti.2004.014266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ghanem KG. Hutton HE. Zenilman JM. Zimba R. Erbelding EJ. Audio computer assisted self interview and face to face interview modes in assessing response bias among STD clinic patients. Sex Transm Infect. 2005;81:421–425. doi: 10.1136/sti.2004.013193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Catania JA. Gibson DR. Chitwood DD. Coates TJ. Methodological problems in AIDS behavioral research: Influences on measurement error and participation bias in studies of sexual behavior. Psychol Bull. 1990;108:339–362. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.108.3.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Linton J. Daugherty TK. Perceived therapeutic qualities of counselor trainees with disabilities. J Instruct Psychol. 1999;26:125–136. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bhattacharya G. Health care seeking for HIV/AIDS among South Asians in the United States. Health Soc Work. 2004;29:106–115. doi: 10.1093/hsw/29.2.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sue S. Fujino DC. Hu LT. Takeuchi DT. Zane NW. Community mental health services for ethnic minority groups: A test of the cultural responsiveness hypothesis. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1991;59:533–540. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.59.4.533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saha S. Taggart SH. Komaromy M. Bindman AB. Do patients choose physicians of their own race? Health Aff (Millwood) 2000;19:76–83. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.19.4.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Striley CW. Margavio C. Cottler LB. Gender and race matching preferences for HIV post-test counselling in an African-American sample. AIDS Care. 2006;18:49–53. doi: 10.1080/09540120500159466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pealer LN. Peterman TA. Newman DR, et al. Are counselor demographics associated with successful human immunodeficiency virus/sexually transmitted disease prevention counseling? Sex Transm Dis. 2004;31:52–56. doi: 10.1097/01.OLQ.0000104814.89521.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Torrone EA. Thomas JC. Leone PA. Hightow-Weidman LB. Late diagnosis of HIV in young men in North Carolina. Sex Transm Dis. 2007;34:846–848. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31809505f7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hightow LB. Leone PA. Macdonald PD. McCoy SI. Sampson LA. Kaplan AH. Men who have sex with men and women: A unique risk group for HIV transmission on North Carolina College campuses. Sex Transm Dis. 2006;33:585–593. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000216031.93089.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hightow LB. MacDonald PD. Pilcher CD, et al. The unexpected movement of the HIV epidemic in the Southeastern United States: Transmission among college students. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005;38:531–537. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000155037.10628.cb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sena AC. Torrone EA. Leone PA. Foust E. Hightow-Weidman L. Endemic early syphilis among young newly diagnosed HIV-positive men in a southeastern U.S. state. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2008;22:955–963. doi: 10.1089/apc.2008.0077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Greene JC. Caracelli VJ. Graham WF. Toward a conceptual framework for mixed-method evaluation designs. Educ Eval Policy Anal. 1989;11:255–274. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sexually Transmitted Disease Protocols/HIV CTR/Counseling and Consent Form. North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services. 2008. www.rabies.ncdhhs.gov/epi/hiv/stdmanual/Management%20Protocols/HIV%20Opt%20Out.pdf. [Feb 4;2009 ]. www.rabies.ncdhhs.gov/epi/hiv/stdmanual/Management%20Protocols/HIV%20Opt%20Out.pdf

- 32.Kamb ML. Fishbein M. Douglas JM, Jr., et al. Efficacy of risk-reduction counseling to prevent human immunodeficiency virus and sexually transmitted diseases: A randomized controlled trial. Project RESPECT Study Group. JAMA. 1998;280:1161–1167. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.13.1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pilcher CD. McPherson JT. Leone PA, et al. Real-time, universal screening for acute HIV infection in a routine HIV counseling and testing population. JAMA. 2002;288:216–221. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.2.216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.CDC. Number of sex partners and potential risk of sexual exposure to human immunodeficiency virus. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1988;37:565–568. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.CDC. Condoms for prevention of sexually transmitted diseases. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1988;37:133–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Varghese B. Maher JE. Peterman TA. Branson BM. Steketee RW. Reducing the risk of sexual HIV transmission: Quantifying the per-act risk for HIV on the basis of choice of partner, sex act, and condom use. Sex Transm Dis. 2002;29:38–43. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200201000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stokes MD. Davis CS. Koch GG. Categorical Data Analysis Using the SAS System. 2nd. Cary, NC: SAS Publishing; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Troust J. Statistically nonrepresentative stratified sampling: A sampling technique for qualitative studies. Qual Sociol. 1986;9:54–57. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Glaser BG. Strauss A. The Discovery Of Grounded Theory. Hawthorne: Aldine; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ulin P. Robinson ET. Tolley EE. Qualitative Methods in Public Health. San Francisco: Josey-Bass; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bernstein KT. Liu KL. Begier EM. Koblin B. Karpati A. Murrill C. Same-sex attraction disclosure to health care providers among New York City men who have sex with men: Implications for HIV testing approaches. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:1458–1464. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.13.1458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Armstrong K. Ravenell KL. McMurphy S. Putt M. Racial/ethnic differences in physician distrust in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2007;97:1283–1289. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.080762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hennessy M. Williams SP. Mercier MM. Malotte CK. Designing partner-notification programs to maximize client participation: A factorial survey approach. Sex Transm Dis. 2002;29:92–99. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200202000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kahn RH. Moseley KE. Johnson G. Farley TA. Potential for community-based screening, treatment, and antibiotic prophylaxis for syphilis prevention. Sex Transm Dis. 2000;27:188–192. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200004000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Steckler A. McLeroy KR. Goodman RM. Bird ST. McCormick L. Toward integrating qualitative and quantitative methods: An introduction. Health Educ Q. 1992;19:1–8. doi: 10.1177/109019819201900101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Weinhardt LS. Carey MP. Johnson BT. Bickham NL. Effects of HIV counseling and testing on sexual risk behavior: a meta-analytic review of published research, 1985–1997. Am J Public Health. 1999;89:1397–1405. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.9.1397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Castrucci BC. Kamb ML. Hunt K. Assessing the Center for Disease Control and Prevention's 1994 HIV counseling, testing, and referral: standards and guidelines: how closely does practice conform to existing recommendations? Sex Transm Dis. 2002;29:417–421. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200207000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Silvestre AJ. Gehl MB. Encandela J. Schelzel G. A participant observation study using actors at 30 publicly funded HIV counseling and testing sites in Pennsylvania. Am J Public Health. 2000;90:1096–1099. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.7.1096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cohall AT. Dini S. Senathirajah Y, et al. Feasibility of using computer-assisted interviewing to enhance HIV test counseling in community settings. Public Health Rep. 2008;123(Suppl 3):70–77. doi: 10.1177/00333549081230S309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]