Abstract

Purpose

A series of six lung cancer cell lines of different cell origin (including small cell and mesothelioma) were characterized immunohistochemically and the role of a series of protein candidates previously implicated in drug resistance investigated.

Methods

These include colony-forming and cell growth assays, immunohistochemistry, siRNA knockouts, Real Time PCR, and Western blots.

Results

No correlation was found with AKT, HO-1, HO-2, GRP78, 14-3-3zeta and ERCC1 levels and cisplatin nor oxaliplatin cytotoxicity but an association was observed with levels of the enzyme, dihydrodiol dehydrogenase (DDH); an enzyme previously implicated in the development of platinum resistance. The relationship appeared to hold true for those cell lines derived from lung epithelial primary tumors but not for the neuroendocrine/small cell and mesothelioma cell lines. siRNA knockouts to DDH-1 and DDH-2 were prepared with the cell line exhibiting the greatest resistance to cisplatin (A549) resulting in marked decreases in the DDH isoforms as assessed by Real Time PCR, western blot and enzymatic activity. The DDH-1 knockout was far more sensitive to cisplatin than the DDH-2 knockout.

Conclusion

Thus, sensitivity to cisplatin appeared to be associated with DDH levels in epithelial lung cancer cell lines with the DDH-1 isoform producing the greatest effect. Results in keeping with transfection experiments with ovarian and other cell lines.

Keywords: Lung, Cancer, Cisplatin, Resistance

INTRODUCTION

Cisplatin is effective against a wide range of solid organ cancers; curative for most kinds of testicular cancer [1] and has been used in the treatment of ovarian, breast, cervical, head and neck cancer [2]. Its mode of action has been postulated to be its reactivity with the N7 position of guanine in the DNA chain (this leads to the formation of intra and interstrand crosslinks [3]. The presence of intrinsic and the development of acquired tumor cell resistance subsequent to chemotherapy limit its efficacy [4].

Many laboratories have attempted to decipher the mechanisms of cisplatin resistance by using a human ovarian carcinoma cell line which shows between a 9 to 15-fold stable resistance to cisplatin (2008/C13). There are many biochemical alterations described in the 2008/C13 cells that are potentially associated with cisplatin resistance; they include decreased intracellular accumulation of cisplatin [5], increased replicative bypass of cisplatin DNA adducts [6], reduced expression of membrane-associated beta tubulin [7], decreased expression of the intermediate filament cytokeratin-18 [8]. Electron microscopy shows the resistant cells have an altered morphology and hypersensitive to lipophilic cations as opposed to the parental cells [9]. Protein kinase C and the cyclic AMP signal transduction pathways are also perturbed [10, 11] as is expression of the oncogene (c-fos); an effect which can be partially reversed by treatment with an antisense oligonucleotide [12]. In addition, another enzyme (GST π) which has been implicated in cisplatin resistance is not altered in these cells [13] and the drug transport pump MRP-1, which has also been implicated in cisplatin resistance in other cells [14] is not affected [15]. Thus, there are multiple mechanisms interconnected in a complex manner responsible for cisplatin resistance in the 2008/C13 cell line.

Utilization of cDNA microarrays followed by cDNA transfection showed that an enzyme (dihydrodiol dehydrogenase) involved in the metabolic reduction and activation/inactivation of several xenobiotics is implicated in the development of cisplatin resistance in the 2008/C13 cells [16]. DDH belongs to a superfamily of monomeric cytosolic NADP(H)-dependant oxireductases that catalyze the metabolic reduction or oxidation of several xenobiotics [17, 18, 19]. In fact, increased expression of carboxyl reductase has been demonstrated in a doxorubicin-resistant tumor cell line to produce resistance [20] and increased expression of DDH has been described in an ethacrynic acid-resistant colon carcinoma cell line [21]. These drugs, however, require metabolic conversion to an active moity (doxorubicin) or inactivated form (ethacrynic acid) and the metabolic inactivation of cisplatin by DDH has not been described. At least four isoforms of DDH have been identified and characterized (DDH-1, DDH-2, DDH-3 and DDH-4; AKR1C1-4).

Recently, increased expression of DDH has been found to be a poor prognostic factor in patients with non small cell lung cancer [22]. These results led to the present study where a series of lung cancer cell lines (6 different cell types) were investigated with respect to cisplatin cytotoxicity and its potential association with the expression of a series of candidate protein targets. In addition, their sensitivity to oxaliplatin, a platinum drug active in GI cancer [23] but which is thought to produce resistance by a different mechanism [24] was also investigated.

MATERIALS & METHODS

Cell Culture Reagents, Cell Lines and Drugs

Cell culture reagents and Gentamicin were obtained from Cell-grow (Herndon, VA), RNAzol B from Tel-Test Inc. (Friendswood, TX). The lung cancer cell lines including A549, H520, H460, H23, DMS114 and H226 (Table 1) were obtained from ATCC and grown in Ham F-12 medium (A549) and RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and gentamicin at a final concentration of 10 μg/ml. The drugs employed included cisplatin from Aldrich Chemical Co. (Milwaukee, WI), and oxaliplatin from Alexis Biochemicals, (Plymouth Meeting, PA).

TABLE 1. IMMUNOLOGIC CLASSIFICATION OF THE LUNG CANCER CELL LINES.

The techniques and origin of the antibodies are described in the Materials and Methods Section

| CELL LINE |

ATCC | AE1/AE3 | Cam 5.2 | CK7 | CK5/6 | TTF1 | ERCC1 | Ki67 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A549 | Lung cancer | 2+ | 4+ | 4+ | − | − | − / 1+ | 90% |

| H460 | Large cell lung | 2+ / 3+ | 1+ | − | − | − | − | 80% |

| H520 | Squamous cell lung | 4+ | 2+ | + / − | 1+ / 2+ | − | − | 70% |

| H23 | Adenocarcinoma | − | 1+ / 2+ | − | − | − | − | 70% |

| DMS114 | Small cell lung | − | − | − | − | − | − | 80% |

| H226 | Mesothelioma/squamous cell |

4+ | 2+ / 3+ | 4+ | − | − | - / 1+ | 70% |

− indicates Not Determined

Immunohistochemistry

The cells in logarithmic growth phase were centrifuged in a cytofuge, fixed in 90% cold ethanol for 10 min. at RT then reacted with the following monoclonal antibodies; AE1/AE3, Calretinin, CD56, Synaptophysin (Zymed, San Francisco, CA), Cam 5.2 (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA), CK7, TTF-1, CD45, Ber-ep4, Sialosyn.TN, (Dako, Carpenteria, CA), CK5/6 (Cell Marque, Rocklin, CA) and ERCC1 (Neomarkers, Fremont, CA). Detection was performed with biotin-labeled horseradish peroxidase (Ventana, Phoenix, AZ) and the staining performed using a Ventana Bechmark XT machine. The slides were scored on a 0/4+ scale by two pathologists.

MTT Assays

Cells (4 × 103) at 70% confluency were trypsinized and seeded into 96-well plates in triplicate with 0, 0.5, 1, 5, 10, 50 and 100 μM of cisplatin and incubated for 72 hours. 10 μl of MTT (5 mg/ml in isopropanol/HCl (100:1)) was added into each well and incubated for 5 hours at the end of the 72-hour incubation. The plate was scanned at 570 nm in a 96-well plate reader (Genios, Candler, NC). Each experiment was performed at least three times in triplicate.

Colony-forming Assays

Cells (1×105) were seeded in 6-well plates and incubated for 24 hours. They were then treated with different concentrations of cisplatin (0 – 20 μM) for 4 hours. At the end of the treatment period, the cells were washed twice with drug-free medium and then trypsinized with 0.25% Trypsin-0.2% EDTA to obtain single-cell suspensions. Then, 200 cells (from untreated and each treatment group) were seeded in 60mm dishes in duplicate, followed by two-week incubation in drug-free complete medium to allow colony growth. At the end of incubation period, culture medium was aspirated and cells were fixed and stained with 0.5% methylene blue in 50% ethanol for 40 minutes at room temperature. Thereafter, the plates were gently washed with water and allowed to air-dry. Visible colonies (containing 50 or more cells each) were counted to determine the percent colony formation for each drug treatment and IC50 values. Values were expressed as the mean ± S.D. (standard deviation) from triplicate experiments.

Western Blotting Analysis

Cells, at a density of 1×106 ml, were incubated under normal growth conditions and then washed with chilled PBS (3x) and a whole cell lysate prepared from each of the cell lines by scraping the cells into a buffer containing 20 mM Tris-HC1 pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 1% (v/v) Triton X-100, 0.5% (v/v) Nonidet P40, 2.5 mM sodium pyrophosphate, 1mM sodium orthovanadate, 50 mM sodium fluoride and 1x protease inhibitor cocktail, and incubated on ice for 15 minutes. The lysate was then centrifuged at 13,000g for 20 minutes and the supernatant was transferred to a fresh tube and stored at – 80°C. Proteins were separated on a SDS-PAG gel and transferred to a PVDF membrane. The different antibodies were applied at concentrations defined by the manufacturer to the PVDF membrane and the bands identified with enhanced chemiluminescence reagents (Pierce Biochemicals, Rockford, IL).

Antibodies utilized in the Western Blots were rabbit polyclonal HO-2 (1:2000) (BD Bioscience, San Diego, CA), rabbit polyclonal HO-1 (1:1000) (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rockford, IL), rabbit polyclonal AKT (1:1000) (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA), goat polyclonal GRP78 (1:200) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), mouse polyclonal antibody to DDH-1 (1:250) and DDH-2 (1:250) (Abnova Corp., Walnut, CA), and a mouse monoclonal antibody against DDH-3 (1:2000) (Abcam, Cambridge, MA). The secondary antibodies were goat anti-rabbit and rabbit (1:4000) anti-goat (Pierce, Rockford, IL) and rabbit anti-mouse (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rockford, IL).

DDH knockdown in A549 cells

siRNAs corresponding to DDH-1 and DDH-2 genes were designed according to pSilencer neo instruction manual (Ambion, USA). Briefly, the 21-nt potential sequences in the target mRNAs of DDH that begin with an AA dinucleotide were found and compared to the human genome database using BLAST (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST). Any target sequences with more than 16-17 contiguous base pairs of homology to other coding sequences were eliminated from consideration. The hairpin siRNA template oligonucleotides were designed by a web-based insert design tool. For each gene, three pairs of sequences were designed and the following gene-specific sequences were selected as optimal: DDH-1: Sense sequence: 5′-GCCCAUUGGCCAGAAAAAATT-3′, antisense sequence: 5′- UUUUUUCUGGCCAAUGGGCTT-3′; DDH-2 Sequence: 5′-GCUACAGCUAAGCCCAUCGTT-3′, antisense sequence: 5′-CGAUGGGCUAGCUGUAGCTT-3′. The siRNAs-associated DNA sequences were synthesized and inserted into the BamH1 and HindIII sites of a pSilencer 3.1 neo vector (Ambion, Austin, TX) and referred to as pSilencer-DDH-1 or DDH-2. All siRNA-associated plasmids were analyzed by restriction endonclease digestion and DNA sequencing before use. Negative control, siRNA (Cat. #4611, lot #074 P24A) and GFP control insert p-Silencer (lot #033P00B) were obtained from Ambion (Austin, TX). Human lung cancer A549 cells were prepared in six-well plates at a density of 2×105 cells per well, grown for 24 hours and then transfected with 1μg of siRNA plasmid (pSilencer 3.1 – DDH-1 or DDH-2) using lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) in serum-free Ham’s F-12 medium as described by the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, 2 μl of lipofectamine2000 was added to 100 μl Ham’s F-12 serum-free medium which was kept at room temperature for 10 min. 1 μg siRNA plasmid were added to 100 μl Ham’s F-12 and the diluted lipofectamine 2000 was added to the diluted siRNAs and siRNA plasmids and incubated for 20 min at room temperature. The pre-incubated cells were washed with serum-free medium and 0.8 ml medium and 0.2 ml of the transfection mixture added to each well. After a 5-hour incubation, the transfected cells were trypsinized and diluted to grow in medium with G418 at a final concentration of 140 μg/ml. Negative siRNA sequences and empty pSilence 3.1 vector were used as controls. The clones were maintained in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with G418 (0.7 μg/ml) (Ambion, Austin, TX).

Semi Quantitative RT-PCR Analysis

Total RNA was isolated from the cells after a brief wash (2x) with cold PBS (pH 7.4), RNAzol (tel-test, Friedwood, TX), was added followed by chloroform extraction, isopropanol precipitation, and a 75% (v/v) ethanol-DEPC wash. The reverse transcription reaction consisted of 1 μg of RNA, 4 units of Omniscript RT, 1 μM oligo-dT primer, 0.5 mM dNTP, 10 units of RNase inhibitor, and 1x RT buffer. Reverse transcription was performed at 37° C for 1 h and inactivated at 93° C for 3 minutes. The cDNA was then amplified by PCR using gene-specific primer pairs. Each PCR reaction consisted of 1x PCR buffer, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 200 μM dNTP, 2.5 units of Taq Polymerase and 0.2 mM gene-specific forward (F) and reverse (R) primers (see below). The PCR conditions were as follows: an initial denaturation at 94° for 15 s, 55° C for 30 s, 72 ° C for 30 s for the number of cycles optimized for each primer to ensure that the product intensity fell within the linear phase of amplification, and then a final elongation step was performed for 10 min at 72° C. RT-PCR amplification of GAPDH transcript was used as the internal control to verify that equal amounts of RNA were used from each cell line. The PCR products were separated on a 1.5% agarose gel stained with ethidium bromide (0.35 μg/mL) by electrophoresis in 1x Tris borate EDTA buffer. A Hae III digest of Ф-X174 DNA was used as a standard marker.

| HO-1 | F 5′-CAGCAGCAATGTCAGCGGAAGTG-3′ R 5′-CATGATGGGTGCTTCACATGT-3′ |

| HO-2 | F 5′-TCCGATGGGTCCTTACACTC-3′ R 5′-TAAGGAAGCCAGCCAAGA-3′ |

| DDH-1 | F 5′-CTAACCAGGCCAGTGACAGA-3′ R 5′-CTCATGCAATGCCCTCCATG-3′ |

| DDH-2 | F 5′-GCTAACCAGGCCAGTGACAGAAATG-3′ R 5′-CTTCTGGCAGACCTCATGCAATG-3′ |

| DDH-3 | F 5′-CCCATTGTTTTTGTAATCTCTG-3′ R 5′-TTATTTCAAAATGATAAAAATTTATTG-3′ |

| GAPDH | F 5′-GAAGGTGAAGGTCGGAGTC-3′ R 5′-GAAGATGGTGATGGGATTC-3′ |

Real Time (RT)-PCR Analysis

For the Real Time-PCR analysis, SYBR green dye was utilized in each of the PCR reactions using an Eppendorf Real-Plex PCR System. The reaction mixture included 1 μg of RNA, 4 units of omniscript RT, 1 μM of oligo (dT) primer, 0.5 mM dNTP, 10 units of RNAase inhibitor and 1x RT buffer and was performed at 37° for 1 hour followed by incubation at 93° for 3 minutes. Thereafter, an equal volume of cDNA was amplified using the gene-specific primer pairs in a reaction mixture consisting of 1x PCR buffer, 1.5 mM MgC12, 200 μM dNTP, 2.5 units of Taq polymerase and 0.2 mM of gene-specific forward and reverse primers (see below). The initial denaturation was 94° for 3 minutes was followed by 94° for 15 seconds, 55° for 30 seconds, then 72° for 30 seconds for a number of cycles optimized for each primer. The final elongation step was performed for 10 minutes at 72°. The cycle threshold values were collected and analyzed by the Mastercycler Eppendorf Realplex software system. The primers were designed using a software program: Primer Express, Version 1 from Applied Biosystems (Foster City, CA).

For absolute quantification of DDH-1 and DDH-2 mRNA levels, a standard curve was generated utilizing 30 – 300,000 copies of linearized plasmids containing DDH-1 or DDH-2 full length cDNA as templates. The plasmids containing the full-length DDH-1 and DDH-2 cDNA have been described before34. Absolute quantification of DDH-1 and DDH-2 mRNA was achieved by the regression equations obtained from the standard curves as described (http://docs.appliedbiosystems.com/pebiodocs/04371090.pdf, Applied Biosystems).

Primers for Real-time PCR

| DDH-1 | F 5′-GTAAAGCTTTAGAGGCCAC-3′ R 5′-ATAAGGTAGAGGTCAACATAA-3′ |

| DDH-2 | F 5′-AAGCCGGGTTCCACCATATT-3′ R 5′-TGACATTCCACCTGGTTGCA-3′ |

| DDH-3 | F 5′-AAGCTGGGTTCCGCCATATA-3′ R 5′-TGCCTGCGGTTGAAGTTTGA-3′ |

| GAPDH | F 5′-ACCCACTCCTCCACCTTTG-3′ R 5′-CTCTTGTGCTCTTGCTGGG-3′ |

DDH Enzyme Activity

Cells were plated at a density of 2×106 in 100mm plates and incubated for 24 hours. At the end of the incubation period, the cells were washed with chilled, phosphate-buffered saline, and scraped into a buffer containing 10mM sodium phosphate (pH 7.4), 150 mM KCl and 0.5 mM EDTA (Buffer A). After a brief centrifugation, the cells were resuspended in Buffer A containing protease inhibitor cocktail and homogenized in a glass Dounce homogenizer with a tight fitting pestle. The lysed homogenate was centrifuged at 14,000 g for 20 minutes. The supernatant fraction was further centrifuged at 100,000 g for 60 minutes to separate the cytosol fraction. Aliquots were stored at −70° until use. The protein concentration was determined by the Coomassie blue assay (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) using BSA as a standard. Enzyme activity was then assayed in a reaction mixture consisting of 4 mM NADP+, 0.1 mM potassium phosphate, pH 7.0, with indicated concentrations of substrate and the cytosolic fraction. The reaction was started by addition of substrate, and the disappearance of NADPH at 25 °C was monitored with the aid of a Beckman DU-70 recording spectrophotometer at 340 nm. An assay mixture containing all of the components except the substrate served as the blank. Initial rates of NADPH disappearance were determined in triplicate.

Statistical Analysis

The linear regression analysis for IC50s and paired t-test were performed using Excel and the SigmaStat Statistical Analysis System, Version 1.01. P values were considered to be significant when p <0.05.

RESULTS

Characterization of the cell lines

The cells were characterized by immunohistochemistry (Table 1) and it is apparent that A549, H460 and H23 are all epithelial non-small carcinomas of the lung as evidenced by expression of keratins and nonexpression of markers of squamoid differentiation such as CK5/6. A549 appears to be an adenocarcinoma whereas H520 shows squamoid differentiation, (CK5/6 positive) correlating to the ATCC designation of the original cell lines. H460 and H23 are best classified as poorly differentiated non-small cell lung carcinomas. Immunohistochemical staining of the DMS114 cells with synaptophysin and CD56 show this line to be of small cell/neuroendocrine origin.. Positive staining of the H226 cells by calretinin and their negativity to Ber-EP4 (positive if an adenocarcinoma) and sialosyn-Tn show that this cell line is of mesothelial cell origin (ATCC designation: squamoid/mesothelioma). Thus the modern immunohistochemical staining analysis correlates quite well with the origin of cell lines listed by the ATCC – derived from the primary tumors 20 years ago when modern immunotyping was not available. TTF staining is negative; a not unexpected finding since these cells are morphologically undifferentiated (high proliferation rate) and although this marker is positive in 72% of lung adenocarcinomas only 5% of squamous and 0% in large cell are positive; additionally, this marker is not positive in tumors with a high proliferation index [25]. (See Table 1 for Ki67 proliferation index.)

Cytotoxicity Assays

It can be seen when colony-forming assays are performed with these cells lines that the IC50 to cisplatin of the non-small cell epithelial cell lines decreases with A549>H520 = H460>H23 (Table 2) and that the IC50 values are high (except H23) relative to human ovarian cells sensitive to cisplatin (2008, A2780). However, the small cell/neuroendocrine cell line (DMS114) and the mesothelial cell line (H226) appear to have resistance to cisplatin (similar to H520 and H460). If oxaliplatin is compared to cisplatin, some correlation is observed with the epithelial cells with A549, H520 and H460 being equally resistant and H23 still the most sensitive but the mesothelial cell line H226 appears sensitive to oxaliplatin.

TABLE 2. COLONY-FORMING ASSAYS WITH CISPLATIN AND OXALIPLATIN.

Experimental details are described in the Material and Methods Section. Number of experiments (each performed in duplicate) are indicated in parentheses. Error is expressed as mean ± SD

| Cell Line | IC50 cisplatin (μM ± SD) | IC50 oxaliplatin (μM ± SD) |

|---|---|---|

| A549 | 3.1 ± 0.2 (3) | 1.9 ± 0.1 (3) |

| H460 | 1.9 ± 0.1 (3) | 2.1 ± 0.1 (3) |

| H520 | 1.8 ± 0.3 (3) | 2.2 ± 0.2 (3) |

| H23 | 0.5 ± 0.1 (3) | 0.8 ± 0.1 (3) |

| H226 | 2.2 ± 0.3 (3) | 0.8 ± 0.1 (3) |

| DMS114 | 1.6 ± 0.3 (3) | 1.0 ± 0.1 (3) |

| 2008 | 0.3 ± 0.1 (3) | ND |

| A2780 | 0.3 ± 0.1 (3) | ND |

ND = Not Determined

Western Blots

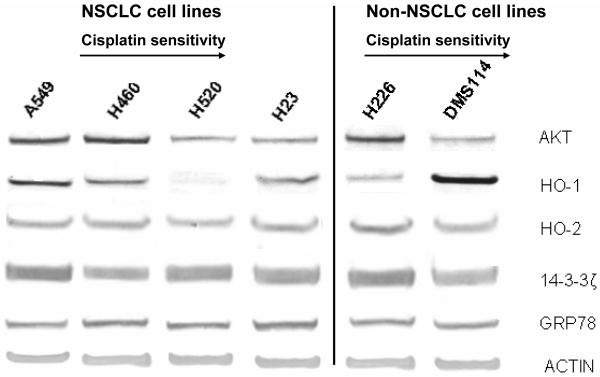

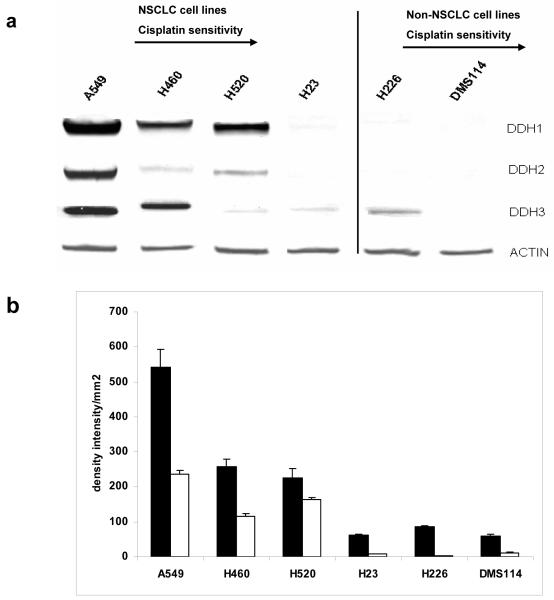

Various proteins have been implicated in drug resistance in lung cancer cell lines including those involved in the AKT pathway [26], ROS generation (HO-1 and HO-2) [27, 28], 14-3-3zeta [29] pathway and the ER stress pathway (GRP78) [30]. mRNA and protein expression were investigated - no association with cisplatin resistance was observed between the levels of HO-1, 14-3-3zeta or GRP78 (Figure 1) with minimal changes observed between the cell lines; AKT levels showed poor correlation with very high levels in H460 and 226 and high levels of HO-1 were only observed in DMS114 and minimal levels in H520. However, when DDH-1, DDH-2 and DDH-3 were analyzed, the NSCL cell lines (A549, H520, H460 and H23) showed an association with decreased expression of total DDH (and to a lesser extent DDH-1) with decreased resistance to cisplatin (Figure 2). The non-epithelial cell lines (DMS114 and H226) showed little correlation with cisplatin cytotoxicity with low levels of DDH but relatively high resistance to the drug. Immunologic staining for ERCC1, a DNA excision repair enzyme that has been implicated in cisplatin resistance [31] showed staining that was primarily cytoplasmic with little nuclear positivity (the control tissue showed strongly positive nuclear staining) and poor correlation of nuclear staining with cisplatin cytotoxicity (Table 1). A recent investigation reported only half of lung tumors showed nuclear positivity for this enzyme [32].

Fig. 1.

Protein expression of AKT, HO-1, HO-2, 14-3-3zeta and GRP78 in six lung cancer cell lines; Lane 1 (A549), 2 (H460), 3 (H520), 4 (H23), 5 (H226) and 6 (DMS114), as analyzed by Western blot analysis. The protein extraction and separation was performed as described in the Material and Methods Section. Actin was used as an internal control to ensure equal loading of each lane

Fig. 2.

(a) - Protein expression of DDH-1, DDH2, DDH-3 in six lung cancer cell lines; Lane 1 (A549), 2 (H460), 3 (H520), 4 (H23), 5 (H226) and 6 (DMS114) as visualized following western blot analysis. The origin of the antibodies, condition for protein separation and visualization of the bands was performed as described in the Material and Methods Section. Actin was used as an internal control to ensure equal loading of each lane (b) Densitometry of the western blots (2 gels in duplicate) of total DDH (■) and DDH-1 (□) in six lung cancer cell lines

DDH Knockdown in A549 Cells

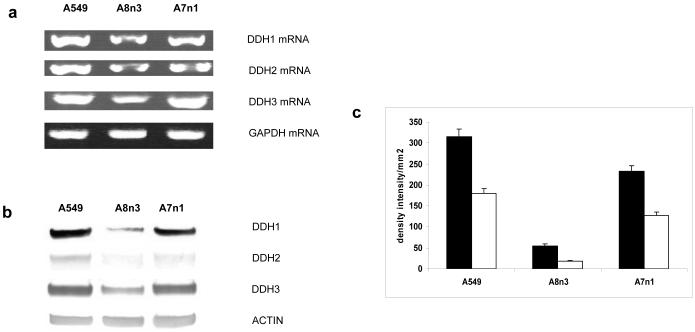

In order to investigate the possible role of DDH in producing cisplatin resistance, siRNA transfectants of DDH-1, DDH-2 and DDH-3 were cloned into the most highly resistant cell line (A549), which was defined as an adenocarcinoma/non-small cell carcinoma of the lung. siRNA transfection of DDH-3 could not be performed in this and other human ovarian cell lines since the transfected cells died; a result which was not unexpected since DDH-3 has recently been implicated in controlling cell growth [33]. The DDH-1 (A8n3) and DDH-2 (A7n1) siRNA transfectants showed decreased levels of DDH-1 and 2 RNA as assessed by RT-PCR (Figure 3a), and real-time PCR (Table 3A). Western blots showed that the DDH-1 knockdown A8n3 showed both a marked decrease in total DDH and DDH-1 (Figures 3b and c); the DDH-2 knockdown (A7nl) showed a much smaller decrease in both total DDH and DDH-1 and these results correlated with the decreased in enzymatic activity (Table 3B). The decrease in DDH-1 in the DDH-2 knockdown was due probably to the 98% homology between the two isoform gene sequences. Colony-forming and MTT assays performed with these transfectants show a marked affect on the IC50 to cisplatin produced by the introduction of the DDH-1 siRNA (A8n3) vector and a far lesser affect with the DDH-2 transfectant (A7n1) (Table 4). This paralleled the marked effect DDH-1 produced when human ovarian (2008) and lung (calu) cell lines were transfected with DDH-1 and DDH2 [34], but not the recent results of Hung, et al. [40], who showed the reverse with H23 lung cells. Interestingly, the IC50 (CFA) of the DDH-1 knockout (A8n3) is higher than H23 but H23 has less DDH-3 than A8n3 suggesting that perhaps this isoform, as well as DDH-1, may play a role in cisplatin resistance as has been reported with the 2008 human ovarian carcinoma cell [35].

Fig. 3.

(a) - Semiquantitative RT-PCR of DDH-1, DDH-2, DDH-3 mRNA in the A549 cells (lane 1), the DDH-1 siRNA transfected cells A8n3 (lane 2) and the DDH-2 siRNA transfected cells A7nl (lane 3). GAPDH mRNA was run as an internal control (b) Protein expression of DDH-1, DDH-2 and DDH-3 as visualized by western blot analysis; A549 (lane 1), A8n3 (lane 2), and A7nl (lane 3). Actin is used as an internal control to assure equal loading in each lane (c) Densitometry of the western blots (2 gels in duplicate) of total DDH (■) and DDH-1 (□) in the A549, A8n3 and A7nl cells

TABLE 3. QUANTITATION OF DDH1 AND DDH2 BY Real Time PCR (A) AND ENZYME ACTIVITY (B) OF THE siRNA A549 KNOCKOUTS.

(A) Experimental details for absolute quantitation of DDH-1 and DDH -2 mRNA are described inthe Material and Methods Section. The number of experiments (in duplicate) are in parentheses. Data are expressed as mean ± SD. DDH-1 and DDH-2 mRNA levels were signi ficantly (p<0.05) decreased in the siRNA-transfected cells compared to the parental A549 cells.

(B) DDH enzyme activity in parental and siRNA-transfected A549 cells was determined in a buffer containing 0.1mM potassium phosphate, pH 7.0, 4mM NADP+, 2mM 1-acenaphthenol and the cytosolic extracts from the indicated cells. The numbers of experiments (in duplicate) are in parentheses. Data are expressed as mean ± SD. The DDH enzyme activity was significantly (p<0.05) decreased in the siRNA-transfected cells compared to the parental A549 cells.

| A | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cells | DDH1 (x105 copy/μg RNA) |

P Value | DDH2 (x105 copy/μg RNA) |

P Value |

| A549 | 149.775 ± 11.866 (3) | 33.342 ± 17.323 (3) | ||

| A8n3 | 6.909 ± 1.352 (3) | <0.05 | 2.211 ± 0.062 (3) | <0.05 |

| A7n1 | 57.291 ± 3.757 (3) | <0.05 | 1.046 ± 0.4394 (3) | <0.05 |

| B | ||

|---|---|---|

| Cells | Enzyme activity (nmole/min/mg protein) |

P Value |

| A549 | 58.7 ± 1.9 (3) | |

| A8n3 | 11.1 ± 5.3 (3) | <0.01* |

| A7n1 | 21.3 ± 4.0 (3) | <0.01* |

TABLE 4. CYTOTOXICITY ASSAYS WITH A549 and siRNAs TRANSFECTANTS.

Colony-forming assays and MTT assays are described in the Material and Methods Section Numbers of experiments (duplicate) are indicated in parentheses. Data are expressed as mean ± SD. P values were obtained by comparing the IC50 values of the parental A549 cells versus the siRNA-transfected cells.

| CFA | MTT | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cells | IC50 (μM ± S.D.) | Fold resistance |

P Value | IC50 (μM ± S.D.) | Fold resistance |

P Value |

| A549 | 3.5 ± 0.8 (3) | 1 | 19.0 ± 3.0 (3) | 1 | ||

| A8n3 | 1.9 ± 0.1 (3) | 0.53 | <0.05 | 7.6 ± 0.6 (3) | 0.40 | <0.05 |

| A7n1 | 2.6 ± 0.6 (3) | 0.74 | <0.05 | 11.5 ± 0.4 (3) | 0.61 | <0.05 |

DISCUSSION

An investigation was initiated to study the role of various proteins involved in widely different cellular pathways. Some of these proteins have been implicated in the development of cisplatin resistance in lung cancer and include AKT [27]. HO-1, a protein induced by stress-stimulation including chemopreventive agents [28] and HO-2 its partner, which has been implicated in cisplatin resistance in human ovarian 2008 cells [35]. The up-regulation of 14-3-3zeta, which cam result in down-regulation of the AKT/PI-3 kinase pathway, was investigated since increased expression correlated to poor outcome in NSLC lung cancer and its down-regulation in lung cancer A549 cells sensitizes these cells to cisplatin [29]. GRP78 is an endoplasmic reticulum stress protein which has been implicated in predicting chemotherapeutic response in breast [36], prostate [37] and lung [20] cancer; with higher levels generally correlating to poor outcome. ERCC1, a member of the excision repair cross-complementary group-1 proteins, has also been implicated in the development of cisplatin resistance in lung cancer with positivity correlating to poor survival and cisplatin resistance [32]. All six proteins from these widely different pathways appeared to correlate poorly with cisplatin cytotoxicity in the six lung cancer cell lines studied, four of epithelial, one of neuroendocrine and one of mesothelial origin.

Recently, work with a human ovarian cancer cell line which exhibits stable resistance to cisplatin implicated an enzyme, dihydrodiol dehydrogenase, in the production of resistance to cisplatin and carboplatin in a wide range of cells derived from cancers from different primary sites [34]. This enzyme, a member of the superfamily of monomeric cytosolic NADPH-dependent oxireductases, catalyzes the interconversion of aldehydes and ketones to alcohols. Involvement of oxireductases in producing drug resistance has been reported, albeit in a few cases; in human colon cancer cells with ethacrylic acid [20] and in a doxorubicin-resistant cell line [21]. When DDH isoforms were transfected into a wide range of tumor cell types, ubiquitous induction of cisplatin resistance and carboplatin resistance was observed primarily with DDH-1 and to a far lesser extent with DDH-2 and DDH-3 [34]. The transfected cells showed no cross-resistance to other widely used chemotherapeutic agents including Taxol, Vincristine, Doxorubicin and Melphalan, except in the case of a germ cell tumor cell line (Tera) that was found to be cross-resistant to Vincristine and Doxorubicin. However in this study, human lung cancer cell lines from disparate origins were studied and cisplatin sensitivity appears only to be associated with DDH-1, DDH-2 or DDH-3 expression in the four epithelial cell carcinomas but not in a neuroendocrine/small cell or mesothelioma-derived cell line. These results have been substantiated here by RNA interference experiments with DDH-1 and DDH-2 which showed that decreasing DDH-1 in the most highly resistant cell line (A549) produced marked decreases in the IC50 to cisplatin.

Interestingly, resistance to oxaliplatin appears markedly decreased as compared to cisplatin with the mesothelial cell line (H226); a not unexpected result since the latter drug has been shown to have a different mode of action to that of cisplatin producing primarily DNA-strand breaks as opposed to crosslinks [23]. In addition, studies on the development of resistance to oxaliplatin shows (although the studies are meager) show that an altered mode of drug uptake may explain the development of resistance in a human ovarian as well as a colon cancer cell line [24]. Both sets of results may explain why oxaliplatin is useful in treating GI and colon cancers whereas cisplatin is relatively ineffective [38].

How DDH exerts its effect is still a matter of speculation; there are no studies as yet showing any direct interaction with cisplatin. Studies have implicated ROS in certain human ovarian cell lines but no correlation with basal ROS levels was observed with these lung cell lines.

Studies are currently underway to determine whether the expression of DDH has a clinical role in lung cancer. A preliminary study suggested that it may play an important role in predicting outcome and prognosis in lung cancer has appeared but whether the patients with poor prognoses were due to treatment failure with cisplatin was not addressed [22]. In addition, identification of which DDH isoforms were implicated was not investigated in the clinical material although DDH transfection into an epithelial lung cell line, (H-23) showed resistance with both DDH-1 and DDH-2 transfectants [40] with the latter producing the greatest effect. Results contrary to reports with both lung and ovarian cells where DDH-1 transfection produced a far greater effect than DDH-2 [34] and the experiments described here where DDH-1 knockdown decreased cisplatin cytotoxicity far more than DDH-2. The primer described by Hung, et al. [39] is not specific and will produce both DDH-1 and DDH-2 isoforms and a polyclonal antibody was employed (not specific for either isoform) and this may explain the discrepant results.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The work was supported by the National Institutes of Health [Grant R01-CA098804, Funding Agency: National Cancer Institute].

Footnotes

“DISCLOSURES: NONE”

Contributor Information

Jianli Chen, North Shore-Long Island Jewish Health System, The Feinstein Institute for Medical Research, Manhasset, NY; Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, Staten Island University Hospital, Staten Island, NY.

Nashwa Emara, Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, Temple University School of Medicine, Philadelphia, PA.

Charalambos Solomides, Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, Temple University School of Medicine, Philadelphia, PA.

Hemant Parekh, Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, Temple University School of Medicine, Philadelphia, PA.

Henry Simpkins, North Shore-Long Island Jewish Health System, The Feinstein Institute for Medical Research, Manhasset, NY; Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, Staten Island University Hospital, Staten Island, NY.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ozols RF, William SD. Testicular Cancer. Curr Probl Cancer. 1989;13:287–335. doi: 10.1016/0147-0272(89)90020-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Loehrer PJ, Einhorn LH. Drugs Five Years Later, Cisplatin. Ann Intern Med. 1984;100:704–713. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-100-5-704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pinto A, Lippard SJ. Binding of the antitumor drug Cisdiamminedichloroplatinum (II) (cisplatin) to DNA. Biochem Biophys Acta. 1985;780:167–180. doi: 10.1016/0304-419x(85)90001-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Timmer-Bosscha H, Mulder NH, deVries EGE. Modulation of cisdiamminedichloroplatinum (II) resistance: A review. Br J Cancer. 1992;66:227–238. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1992.249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Andrews PA, Velury S, Mann SC, Howell SB. Cisdiamminedichloroplatinum (II) accumulation in sensitive and resistant human ovarian cells. Cancer Res. 1992;48:68–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mamenta EL, Poma EE, Kaufman WK, Delmastro DA, Grady HL, Chaney SG. Enhanced replicative bypass of platinum: DNA adducts in cisplatin resistant human ovarian carcinoma cell lines. Cancer Res. 1994;54:3500–3508. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Christen RJ, Jekunen AP, Jones JA, Thiebaut F, Shalinsky DR, Howell SB. In Vitro modulation of cisplatin accumulation in human ovarian cells by pharmacological alteration of microtubules. J Clin Invest. 1993;92:431–440. doi: 10.1172/JCI116585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Parekh HK, Simpkins H. The differential expression of cytokeratin 18 in cisplatin-sensitive and resistant human ovarian adenocarcinoma cells and its association with drug sensitivity. Cancer Res. 1995;55:203–5206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Andrews PA, Albright KD. Mitochondrial defects in cisdiamminedichloroplatinum (II) - resistant human ovarian carcinoma cells. Cancer Res. 1992;52:1895–1901. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Isonishi S, Jekunen AP, Hom DH, Eastman A, Edelstein PS, Thiebaut FB, Christen RD, Howell SB. Modulation of cisplatin sensitivity and growth rate of an ovarian carcinoma cell line by bombesin and tumor necrosis factor. J Clin Invest. 1992;90:1436–1442. doi: 10.1172/JCI116010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mann SC, Andrews PA, Howell SB. Modulation of cis-diamminedichloroplatinum (II) accumulation and sensitivity by forkolin: a 3 isobutyl, 1-methylxanthine in sensitive and resistant human ovarian cells. Int J Cancer. 1992;48:866–872. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910480613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moorehead RA, Singh G. Influence of the proto-oncogene c-fos on cisplatin sensitivity. Biochem Pharmacol. 2000;59:337–345. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(99)00333-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Parekh HK, Simpkins H. Cross resistance and collateral sensitivity to natural product drugs in cisplatin-sensitive and -resistant rat lymphoma and human ovarian carcinoma cells. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 1996a;37:457–462. doi: 10.1007/s002800050412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen Z-S, Mutoh M, Sumizawa T, Furukawa T, Haraguchi M, Tani A, Saijo N, Kondo T, Akiyami S. An active efflux system for heavy metals in cisplatin-resistant human KB carcinoma cells. Exp Cell Res. 1998;240:312–320. doi: 10.1006/excr.1998.3938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Parekh HK, Simpkins H. Species-specific differences in taxol transport and cytotoxicity against human and rodent tumor cells: Evidence for an alternative transport system. Biochem Pharmacol. 1996b;51:301–311. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(95)02176-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Deng HB, Adikari M, Parekh HK, Simpkins H. Increased expression of dihydrodiol dehydrogenase induces resistance to cisplatin in human ovarian carcionoma cells. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:15035–15043. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112028200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smithgall TE, Harvey RG, Penning TM. Regio and stereospecificity of homogeneous 3 alpha hydroxysteroid-dihydrodiol dehydrogenase for trans-dihydrodiol metabolites of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:6184–6191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smithgall TE, Harvey RG, Penning TM. Oxidation of the trans-3′4 - dihydrodiol metabolites of the potent carcinogen 7,12 dimethylbenz(a)anthracene and other benz(a)anthracene derivatives by 3 alpha hydrosteroid dehydrogenase: effects of methyl substitution on velocity and sterochemical course of trans-dihydrodriol oxidation. Cancer Res. 1988a;48:1227–1232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smithgall TE, Harvey RG, Penning TM. Spectroscopic identification of orthoquinones as the products of polycyclic aromatic trans-dihydrodiol oxidation catalyzed by dihydrodiol dehydrogenase: A potent route of proximate carcinogen metabolism. J Biol Chem. 1988b;263:1814–1820. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ax W, Soldan M, Koch L, Maser E. Development of duanorubicin resistance in tumor cells by induction of carbonyl reductase. Biochem Pharmacol. 2000;59:293–300. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(99)00322-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ciacco PJ, Stuart JE, Tew KD. Overproduction of a 37.5 kDa cytosolic protein structurally similar to prostaglandin F synthase in ethacrynic acid-resistant human colon cells. Mol Pharmacol. 1993;43:845–853. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hsu N-Y, Ho H-C, Chow K-C, Lin T-Y, Shih C-S, Wang L-S, Tsai C-M. Overexpression of dihydrodiol dehydrogenase as a prognostic marker of non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Res. 2001;61:2727–2731. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Raymond E, Faure S, Chaney S, Wojnarowski-Cvithovic E. Cellular and Molecular Pharmacology of Oxaliplatin. Mol Cancer Ther. 2002;1:227–235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hector S, Bolanowska-Higdon W, Zolanowicz J, Hitt S, Pendyla L. In vitro studies on the mechanisms of oxaliplatin resistance. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2001;48:398–406. doi: 10.1007/s002800100363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pelosi G, Fraggetta F, Pasini F, Maisonneuve P, Sonzogni A, Iannucci A, Terzi A, Bresaola E, Valduga F, Lupo C, Viale G. Immunoreactivity for thyroid transcription factor-1 in Stage 1 non-small cell carcinomas of the lung. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:363–372. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200103000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee T-C, Ho I-C. Expression of heme oygenase in arsenic-resistant human lung adenocarcinoma cells. Cancer Res. 1996;54:1660–1664. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee MW, Kim DS, Min NY, Kim HT. AKT-1 inhibition by RNA interference sensitizes human non-small cell lung cancer cells to cisplatin. Int J Cancer. 2008;122:2380–2384. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kweon M-H, Adikhari V-M, Lee J-S, Mukhtar H. Constitutive overexpression of Nrf2-dependent Heme oxygenase-1 in A549 cells contributes to resistance to apoptosis induced by Epigallocatechin 3-gallate. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:33761–33772. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M604748200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fan T, Li R, Todd NW, Qui Q, Fang H-B, Wang H, Shen J, Zhao R-Y, Caraway NP, Katz RL, Stass SA, Jiang F. Upregulation of 14-3-3zeta in lung cancer and its implication as a prognostic and therapeutic target. Cancer Res. 2007;67:7901–7906. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Uramoto H, Sugio K, Oyama T, Nakata S, Ono K, Yoshimatsu T, Morita M, Yasumoto K. Expression of endoplasmic reticulum molecular chaperone Grp 78 in human lung cancer and its clinical significance. Lung Cancer. 2005;49:55–62. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2004.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dabholkar M, Vionnet J, Bostick-Bruton F, Yu JJ, Reed E. Messenger RNA levels of XPAC and ERCC1 in ovarian cancer tissue correlate with response of platinum-based chemotherapy. J Clin Invest. 1994;94:703–708. doi: 10.1172/JCI117388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hwang IG, Ahn MJ, Park BB, Ahn YC, Han J, Lee S, Kim J, Shim YM, Ahn JS, Park K. ERCC1 expression as a prognostic marker in N2(+) non-small cell lung cancer patients treated with platinum-based neoadjuvant concurrent chemoradiotherapy. Cancer. 2008;113:1379–1386. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Desmond JC, Mountford JC, Drayson MT, Walker EA, Hewison M, Ride JP, Luong QT, Hayden RE, Vanin EF, Bunce CM. The aldo-keto reductase AKR1C3 is a novel suppressor of cell differentiation that provides a plausible target for the non cyclo-oxygenase-dependent antineoplastic actions of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Cancer Res. 2003;63:505–512. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Deng HB, Adikari M, Parekh HK, Simpkins H. Ubiquitous induction of resistance to platinum drugs in human ovarian, cervical, germ cell and lung carcinoma tumor cells overexpressing isoforms 1 and 2 of dihydrodriol dehydrogenase. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2004;54:301–307. doi: 10.1007/s00280-004-0815-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen J, Adikari M, Pallai R, Parekh HK, Simpkins H. Dihydrodiol dehydrogenase regulates the generation of reactive oxygen species and the development of cisplatin resistance in human ovarian carcinoma cells. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2008;61:979–987. doi: 10.1007/s00280-007-0554-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fernandez PM, Tabbara SO, Jacobs LK, Manning FC, Tsangaris TN, Schwartz AM, Kennedy KA, Patierno SR. Overexpression of the glucose regulated stress gene GRP78 in malignant but not benign breast lesions. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2000;59:15–26. doi: 10.1023/a:1006332011207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tang D, Khuleque MA, Jones EL, Theriault JR, Li C, Wong WH, Stevenson MA, Calderwood SK. Expression of heat shock protein and heat shock protein messenger ribonucleic acid in human prostate carcinoma in vitro and in tumors in vivo. Cell Stress Chaperones. 2005;10:46–58. doi: 10.1379/CSC-44R.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fogelman DR, Kopetz S, Eng C. Emerging drugs for colorectal cancer. Expert Opin Emerg Drugs. 2008;13:629–642. doi: 10.1517/14728210802544575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hung J-J, Chow K-C, Wang H-W, Wong L-S. Expression of Dihydrodiol Dehydrogenase and resistance to chemotherapy and radiotherapy in adenocarcinoma cells of the lung. Anticancer Res. 2006;26:2949–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]