Abstract

Estrogen regulates fat mass and distribution and glucose metabolism. We have previously found that estrogen sulfotransferase (EST), which inactivates estrogen through sulfoconjugation, was highly expressed in adipose tissue of male mice and induced by testosterone in female mice. To determine whether inhibition of estrogen in female adipose tissue affects adipose mass and metabolism, we generated transgenic mice expressing EST via the aP2 promoter. As expected, EST expression was increased in adipose tissue as well as macrophages. Parametrial and subcutaneous inguinal adipose mass and adipocyte size were significantly reduced in EST transgenic mice, but there was no change in retroperitoneal or brown adipose tissue. EST overexpression decreased the differentiation of primary adipocytes, and this was associated with reductions in the expression of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ, fatty acid synthase, hormone-sensitive lipase, lipoprotein lipase, and leptin. Serum leptin levels were significantly lower in EST transgenic mice, whereas total and high-molecular-weight adiponectin levels were not different in transgenic and wild-type mice. Glucose uptake was blunted in parametrial adipose tissue during hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamp in EST transgenic mice. In contrast, hepatic insulin sensitivity was improved but muscle insulin sensitivity did not change in EST transgenic mice. These results reveal novel effects of EST on adipose tissue and glucose homeostasis in female mice.

Keywords: adipose, insulin, adipogenesis, leptin, transgenic

sex hormones regulate fat distribution and glucose metabolism (2, 4, 12, 21). Central obesity is common in men, while increased subcutaneous fat is often seen in obese young women (4, 32). These differences are mediated at least partly through estrogen (4, 32). Menopause is characterized by a loss of estrogen production, which leads to an increase in central (visceral) fat accumulation and insulin resistance (10, 11). Estrogen receptor-α (ERα) and aromatase are both expressed in adipose tissue and control estrogen activity (7, 24, 33, 40). Lack of estrogen signaling in mice and humans with ERα or aromatase deficiency results in obesity, insulin resistance, and elevated lipid levels (13–15). Estrogen sulfotransferase (EST, SULT1E1) inhibits estrogen activity by conjugating a sulfonate group to estrogens, preventing estrogen receptor binding and enhancing urinary excretion (36). EST is abundantly expressed in male reproductive tissues, where it is thought to prevent estrogen toxicity (25, 26, 37, 38). We have previously shown that EST is highly expressed in male white adipose tissue (WAT) (17). Castration suppresses EST activity in male WAT, whereas testosterone increases EST activity (17). EST is not detectable in WAT of normal cycling female mice but is markedly induced by testosterone, suggesting that EST may play a role in the metabolic dysregulation associated with hyperandrogenization in females (6, 17). We hypothesized that inhibition of local estrogen activity in female adipose by EST would alter adiposity and metabolism.

To address this issue, we directed EST expression in female mice by using the aP2 promoter. Parametrial and subcutaneous inguinal fat were both decreased in female EST transgenic mice. This is in contrast to systemic inhibition of estrogen in ERα and aromatase knockout mice, which results in obesity (13, 15). The differentiation of primary adipocytes was reduced in EST transgenic female mice compared with wild type (WT) and associated with a decrease in the expression of PPARγ, fatty acid synthase, lipoprotein lipase, and leptin. EST expression had different effects on glucose kinetics in female mice. Hepatic insulin sensitivity was increased in EST transgenic mice, WAT insulin sensitivity was reduced, and muscle insulin sensitivity did not change significantly. Together, these findings reveal novel effects of EST on adiposity and glucose homeostasis in female mice.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

aP2-EST transgenic mice.

The aP2 promoter was previously cloned (19). The cDNA of EST was placed downstream of the aP2 promoter. The transgene was microinjected into the pronuclei of fertilized B6SJL/F1 mouse eggs by the University of Pennsylvania Transgenic and Chimeric Mouse Facility. Transgenic founders were identified by PCR using primers P1, 5′-TGCCAGGGAGAACCAAAGTT-3′, and P2, 5′-TCTGGCCTTGCCAAGAACAT-3′. Similar expression levels were found in two lines, which were used interchangeably. C57BL6/SJL/F1 mice were crossed for seven generations to C57BL/6J background (Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME). Mice were housed (n = 5 per cage) in a 12:12-h light-dark cycle (light on at 7 AM) and ambient temperature 22°C and were allowed free access to water and a regular chow diet (LabDiet, Richmond, IN; catalog no. 5001, containing 4.5% fat, 49.9% carbohydrate, 23.4% protein; 4 kcal/g). Food intake was measured twice weekly, and body weight was measured weekly. Vaginal opening and estrous cycles were assessed after weaning, as previously described (1). The experiments were performed according to protocols reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine.

Tissue chemistry.

At 10 wk, randomly cycling female WT and EST transgenic mice were fasted for 6 h (0700 -1300), and tail blood glucose was measured with a One Touch Ultra II glucometer. The mice were then euthanized by CO2 inhalation, cardiac blood was drawn, and serum was stored at −80°C. Triglyceride, nonesterified fatty acids (NEFA), cholesterol, and β-hydroxybutyric acid levels were measured using colorimetric enzymatic assays (Stanbio, Boerne, TX). Insulin (Crystal Chem, Evanston, IL), leptin (Millipore, Billerica, MA), total and high-molecular-weight (HMW) adiponectin (ALPCO Diagnostics, Salem, NH), and 17β-estradiol (MP Biomedicals, Solon, OH) were measured using enzyme immunoassays.

WAT weight and histology.

Parametrial, subcutaneous inguinal, and retroperitoneal (perirenal) WAT depots and BAT were dissected and weighed, fixed in 10% buffered formalin overnight, washed with 1× PBS, and paraffin embedded. Sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin, and the slides were examined under a Nikon E600 microscope. Images of adipocytes were taken at ×10 magnification per slide, and the cross-sectional areas were measured and analyzed using Adobe Photoshop CS3. Technical assistance was provided by the Morphology Core of the Center for Molecular Studies in Digestive and Liver Diseases.

EST levels in WAT.

EST levels were assessed using Northern and immunoblotting, as we have previously described (17, 35). The EST immunoblots were stripped and reprobed with a glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase antibody (6C5; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA). The protein signal was detected with enhanced chemiluminescence (GE Healthcare, Buckinghamshire, UK). EST enzyme activity was measured in parametrial WAT as described (17, 35). Briefly, the tissue was incubated with [3H]estradiol (Estradiol-2,4-3H; Sigma, E-9767, final concentration 35 nM) in 200 μl of PBS, pH 7.5 and 0.625% Triton X, containing 100 mM 3′-phosphoadenosine 5′-phosphosulfate (Sigma, A-1651), and 200 μg of protein lysate was prepared from tissue homogenate (15,000 g) in the same buffer. The reaction was initiated by the addition of substrate and continued for 30 min at 37°C. The reaction mixture was extracted with 2 volumes of dichloromethane, and an aliquot of the aqueous phase was counted for radioactivity using a scintillation counter. Radioactive counts of denatured protein lysates were determined for background levels. EST enzyme activity was expressed as picomoles of estrogen sulfate formed per hour per milligram of total protein.

Parametrial WAT gene expression.

RNA was extracted from parametrial WAT samples using TRIzol. The RNA was reverse transcribed with Sprint RT Complete-Oligo (dT)18 (Clontech, Mountain View, CA). cDNA was amplified using Taqman Gene Expression Assays (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Expression of mRNA levels of ERα, IL-1β, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP1), and F4/80 were normalized to 36B4 (34, 39).

Primary adipocyte differentiation.

The effect of EST overexpression on primary adipocyte differentiation was evaluated. Inguinal (subcutaneous) adipose tissue was dissected from WT and EST transgenic female mice, minced, and digested with 1.5 U/ml collagenase D and 2.4 U/ml dispase II in DMEM, as previously described (30). The stromal vascular fraction was isolated by centrifugation and filtered through a 150-μm nylon mesh. Cells were grown in growth medium (DMEM-F-12 (1:1), 10% FBS, and antibiotics) for 24 h. Cells were split and then differentiated upon confluence in differentiation medium (DMEM-F-12, 10% FBS, 5 μg/ml insulin, 0.5 mM isobutylmethylxanthine, 1 μM dexamethasone, 125 nM indomethacin, and 1 μM rosiglitazone). After 48 h, the medium was replaced with growth medium containing insulin and then changed to growth medium after 4 days. Differentiated primary adipocytes were stained with Oil red O to detect triglycerides. Other primary adipocytes were subjected to RNA extraction, and the expressions of EST, PPARγ, CCAAT enhancer binding-protein-α (CEBPα), preadipocyte factor 1 (PREF1), ERα, fatty acid synthase (FAS), hormone-senstive lipase (HSL), lipoprotein lipase (LPL), and leptin (LEP) were measured by real-time PCR and normalized to 36B4 (30, 34, 39).

Hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamp.

We assessed glucose kinetics in 10-wk-old female EST transgenic and WT mice under basal (6 h of fasting) and insulin clamp conditions (3, 39). An indwelling catheter was inserted into the right internal jugular vein under pentobarbital sodium anesthesia and extended to the right atrium. Four days after recovery, the mice were fasted for 6 h (0700–1300) and administered a bolus injection of 5 μCi of [3-3H]glucose followed by continuous intravenous infusion at 0.05 μCi/min. Baseline glucose kinetics were measured for 60 min followed by a hyperinsulinemic clamp for 120 min. A priming dose of regular insulin (16 mU/kg Humulin; Eli Lilly, Indianapolis, IN) was given intravenously, followed by continuous infusion at 2.5 mU·kg−1·min−1. A variable intravenous infusion of 20% glucose was administered to attain blood glucose levels of 120–140 mg per 100 ml. The target glucose concentration was maintained for 90 min. The mice were euthanized, and liver, parametrial WAT, and soleus/gastrocnemius muscles were excised, frozen immediately in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C for analysis of glucose uptake. The rates of whole body glucose uptake and basal glucose turnover were measured as the ratio of the [3H] glucose infusion rate (dpm) to the specific activity of plasma glucose. Hepatic glucose production (HGP) during the clamp was measured by subtracting the glucose infusion rate (GIR) from the whole body glucose uptake (Rd) (3, 39). Liver samples were processed for immunoblotting of Akt (no. 9272; Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA) and phospho-Akt (no. 7985R; Santa Cruz Biotechnology). RNA was extracted from liver samples of clamped mice for measurement of glucose-6-phosphatase (G6Pase) and phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (PEPCK) by real-time PCR. The expression of mRNA levels was normalized to 36B4 (34, 39).

Statistics.

Data are represented as means ± SE. Differences in EST transgenic vs. WT were analyzed by unpaired t-test.

RESULTS

Generation of aP2-EST transgenic mice.

We used the aP2 promoter (19) to target expression of EST to adipose tissue. Figure 1A shows the schematic representation of the transgene. The EST cDNA was cloned downstream of the aP2 promoter. Figure 1, B and C, shows EST overexpression in WAT and peritoneal macrophages in female mice. Lower levels of EST expression were detected in the heart, kidney, lungs, and spleen of transgenic females. In contrast, no EST expression was found in WT females (data not shown). In transgenic females, EST mRNA was highly expressed in the parametrial, subcutaneous inguinal, and retroperitoneal (perirenal) WAT (Fig. 1D). EST mRNA was also highly expressed in the interscapular BAT of transgenic females. The expression of EST mRNA in female parametrial fat was further confirmed by increases in EST protein level (Fig. 1E). EST enzyme activity was demonstrated by the ability of parametrial WAT lysates to convert β-estradiol into an inactive sulfated form [Fig. 1F; (35)]. EST activity in transgenic female parametrial WAT was lower than in epididymal WAT from male mice (Fig. 1F). We did not detect changes in serum 17β-estradiol levels (Table 1), or ERα mRNA expression in WAT of transgenic EST female mice (data not shown).

Fig. 1.

Generation and identification of aP2-EST (estrogen sulfotransferase) transgenic (TG) mice. A: schema of the transgene construct. TG founders were identified using primers (P1 and P2) specific to the transgene. Northern blot analysis (B) and quantitative real-time PCR (C) detected abundant EST mRNA expression in parametrial white adipose tissue (WAT) and naïve peritoneal macrophages from female mice. Lower levels of EST mRNA expression were also found in the heart, kidney, lungs, and spleen. No EST mRNA expression was detected in tissues examined from wild-type (WT) female mice. D: EST mRNA expression in parametrial (PF), inguinal (IF), and retroperitoneal (RF) fat and brown adipose tissue (BAT) depots (n = 5). E: EST protein levels in parametrial WAT from transgenic mice. F: EST enzyme activity in parametrial WAT tissue from transgenic female mice vs. WT male epididymal WAT (EF; n = 4–5). No enzyme activity was detected in WT female parametrial WAT. WTM, wild-type male. Data presented are means ± SE. *P ≤ 0.05 vs. WTM EF.

Table 1.

Metabolic parameters in female EST transgenic and WT mice

| WT | EST Transgenic | |

|---|---|---|

| Body weight, g | 18.88 ± 0.54 | 18.46 ± 0.46 |

| Food intake, kcal/day | 15.81 ± 0.65 | 14.56 ± 0.44 |

| Glucose, mg/dl | 150.0 ± 6.20 | 148.4 ± 6.13 |

| Triglycerides, mg/dl | 43.15 ± 1.25 | 42.66 ± 2.01 |

| Cholesterol, mg/dl | 52.91 ± 3.64 | 60.00 ± 5.81 |

| β-Hydroxybutyrate, mg/dl | 2.599 ± 0.82 | 2.229 ± 0.20 |

| NEFA, mEq/l | 0.534 ± 0.055 | 0.598 ± 0.088 |

| Insulin, ng/ml | 0.121 ± 0.030 | 0.072 ± 0.029 |

| 17β-Estradiol, pg/ml | 30.76 ± 7.67 | 46.44 ± 9.90 |

| Leptin, ng/ml | 4.866 ± 0.36 | 3.295 ± 0.23* |

| Total adiponectin, μg/ml | 30.83 ± 0.60 | 34.30 ± 4.56 |

| HMW adiponectin, μg/ml | 5.67 ± 0.43 | 6.63 ± 0.81 |

Values are means ± SE; n = 5–6. WT, wild type; EST, estrogen sulfotranserase; NEFA, nonesterified fatty acids; HMW, high molecular weight.

P ≤ 0.01 vs. WT.

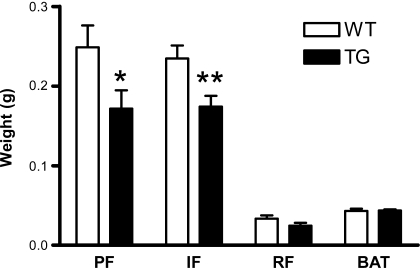

EST transgenic female mice accumulate less fat.

EST expression had no apparent effect on food intake and body weight in female mice (Table 1). Moreover, the timings of vaginal opening and estrous cycles were similar in EST transgenic and WT mice (data not shown). At 10 wk, the weights of parametrial and subcutaneous inguinal WAT were significantly lower in female EST transgenic than in WT mice (Fig. 2). There was no difference in the weights of retroperitoneal (perirenal) WAT and interscapular BAT. Histological examination showed that adipocytes from parametrial and subcutaneous inguinal WAT were smaller in female EST transgenic than in WT (Fig. 3, A–D). The median adipocyte area in the parametrial WAT was 948 μm in EST transgenic and 1,285 μm in WT (P < 0.0001). The median adipocyte area in the subcutaneous inguinal WAT was 766 μm in EST transgenic and 1,020 μm in WT (P < 0.0001). The reduction in WAT mass in EST transgenic mice was associated with a significant decrease in serum leptin levels (P = 0.006; Table 1). Insulin levels were also lower in EST transgenic mice, but this was not significant (P = 0.266; Table 1). Glucose, lipids, and total and HMW adiponectin levels were also not altered significantly by EST overexpression in female mice (Table 1).

Fig. 2.

Fat mass in EST TG (filled bar) and WT female mice (open bar). Data presented are means ± SE; n = 13–14. *P ≤ 0.05 vs. WT; **P ≤ 0.01 vs. WT.

Fig. 3.

A and B: hematoxylin & eosin-stained sections of parametrial WAT from WT (A) and EST TG female mice (B). Scale bar, 100 μm. C and D: histograms comparing distribution of adipocytes in parametrial (C) and inguinal subcutaneous (D) WAT from WT (open bar) and EST TG female mice (filled bar). See text for definitions.

EST overexpression decreases adipogenesis.

To evaluate whether the reduction in subcutaneous and parametrial WAT depots in EST transgenic females could be explained, at least partly, by a reduction adipogenesis, we isolated WAT stromovascular fractions from EST transgenic and WT mice and examined primary adipocyte differentiation. Oil red O staining showed fewer adipocytes in EST transgenic mice compared with WT (Fig. 4, A and B). As expected, EST mRNA levels were higher in transgenic primary adipocytes (Fig. 4C). In contrast, the expression of PPARγ, a major adipogenic transcription factor for adipogenesis, was significantly reduced in EST transgenic adipocytes (Fig. 4C). Moreover, there was a nonsignificant decrease in CEBPα, a transcription factor also involved in adipogenesis, in EST adipocytes (Fig. 4C). On the other hand, the expressions of PREF1, a preadipocyte biomarker, and ERα were unchanged in EST transgenic adipocytes (Fig. 4C). The reduction in adipogenesis in EST transgenic mice was associated with decreased expression of FAS, HSL, LPL, and leptin (Fig. 4D).

Fig. 4.

A and B: primary adipocyte differentiation of subcutaneous WAT from WT and EST TG female mice. C and D: mRNA levels of EST and adipogenic genes in WT and EST TG primary adipocytes. Data presented are means ± SE. **P ≤ 0.01 vs. WT; ***P ≤ 0.001 vs. WT. Scale bar, 100 μm.

Adipose EST overexpression regulates insulin sensitivity.

Previous studies have shown that estrogen increases whole body and adipose tissue insulin sensitivity (20). We used tracer kinetics to study glucose homeostasis under fasted (basal) and insulin clamp conditions in female EST transgenic and WT mice. There was no difference in the basal (fasted) glucose production in WT (62.40 ± 3.47 mg·kg−1·min−1) and EST transgenic mice (59.49 ± 2.79 mg·kg−1·min−1, P = 0.52). In contrast, the GIR needed to maintain blood glucose at 120–140 mg/dl during the insulin clamp was increased in EST transgenic mice, suggesting an improvement in insulin sensitivity (WT 42.32 ± 8.14 vs. EST transgenic 67.77 ± 3.87 mg·kg−1·min−1, P = 0.01; Fig. 5A). HGP was reduced (P < 0.001), whereas the glucose Rd did not change significantly in EST transgenic mice (P = 0.31; Fig. 5A). Glucose uptake was significantly reduced in clamped parametrial WAT of EST transgenic mice (Fig. 5B) but did not change in gastrocnemius/soleus muscles (Fig. 5C). These findings demonstrated that expression of EST expression in WAT increased hepatic insulin sensitivity while reducing WAT insulin sensitivity. In agreement, hepatic p-Akt/Akt protein levels were increased in clamped EST transgenic females, and mRNA levels of gluconeogenic enzymes G6Pase and PEPCK tended to be decreased (Fig. 5, D–F). Insulin resistance in EST transgenic WAT was associated with nonsignificant increases in expression of IL-1β and MCP1. In contrast, the expression of the macrophage biomarker F4/80 did not change in EST WAT (Fig. 5, G–I).

Fig. 5.

Hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamp of WT (open bar) and EST TG female mice (filled bar). A: glucose infusion rate (GIR), hepatic glucose production (HGP), and glucose disappearance rate (Rd). B: glucose uptake in parametrial WAT. C: glucose uptake in skeletal muscle. D: ratio of p-Akt and total Akt protein levels in livers of clamped mice. E and F: mRNA levels of G6Pase and PEPCK in livers of clamped mice. G–I: mRNA levels of IL-1β, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP1), and F4/80 in parametrial WAT. Data are means ± SE; n = 9 mice per group. *P ≤ 0.05 vs. WT; **P ≤ 0.01 vs. WT; ***P ≤ 0.001 vs. WT.

DISCUSSION

Differences in adipose mass and distribution and glucose homeostasis in males and females have been attributed at least partly to sex steroids. Menopause is characterized by reduced estrogen production and a shift in adipose distribution from peripheral to central accumulation (4). Hyperandrogenization in polycystic ovarian disease is associated with central (visceral) obesity, insulin resistance, and type 2 diabetes (6). These sex steroid-induced metabolic changes are also observed in rodents (41). Genetically modified rodents have also offered insights into the role of estrogen in adipose development and glucose homeostasis. Mice deficient in ERα had an increase in WAT compared with WT, partly due to hypertrophy and hyperplasia (13). Moreover, ERα deficiency resulted in a decrease in energy expenditure with no change in food intake (13). Estrogen regulates energy balance through the central nervous system, as evidenced by the development of hyperphagia and reduced energy expenditure in response to injection of ERα RNAi into the ventromedial nucleus of the hypothalamus (22). These mice became obese and glucose intolerant (22). Deficiency of aromatase, the enzyme that synthesizes C18 estrogens from androgens, also results in obesity associated with reduced spontaneous activity (15). However, studies involving ERα and aromatase whole body knockouts did not determine the relative contributions of central vs. peripheral actions of estrogen on adiposity and metabolism. Although testosterone induces EST activity in female WAT (17), it is impossible to discern whether testosterone regulates WAT locally via EST or acts systemically to regulate WAT and metabolism in females. Therefore, to determine the local effect of estrogen inactivation in WAT by EST, we chose a transgenic approach that allowed us to increase EST expression in female WAT to levels found in males. We confirmed that EST increased the levels of the sulfated inactive form of estrogen in WAT without changing systemic 17β-estradiol levels. Disruption of estrogen activity in female WAT decreased the weights of parametrial and subcutaneous inguinal WAT in females. This result is consistent with our previous study (17), where whole body knockout of EST increased the weight of WAT.

EST overexpression decreased primary adipocyte differentiation, providing a possible mechanism for the reduction in inguinal and parametrial WAT depots. The expressions of PPARγ, CEBPα, FAS, HSL, LPL, and leptin were reduced in EST transgenic adipocytes, suggesting a reduction in adipogenesis. EST overexpression via the aP2 promoter decreased parametrial and subcutaneous inguinal WAT but not perirenal WAT or BAT. Thus, it is likely that local factors present in specific WAT depots modulate the response to estrogen inactivation by EST. Our findings on the effect of EST overexpression on WAT are opposite to previous reports in estrogen-deficient mice (13, 15). The difference may be attributed, at least partly, to effects by local vs. systemic actions of estrogen. Although WAT EST expression modifies estrogen activity locally, ablation of ERα or aromatase in the whole body affects estrogen action in WAT as well as the brain and other organs (13, 15). It is well known that estrogen has profound systemic effects on energy homeostasis, including inhibition of feeding through interaction with leptin-sensitive neurons in the hypothalamus (5). Although leptin levels were reduced by 32% in female EST transgenic mice in parallel with the reduction in WAT, food intake was not affected. Understanding of the specific actions of ERα and aromatase in WAT mass and metabolism requires adipose-specific ablation of these genes.

There is evidence in rodents and humans showing potent effects of estrogen on glucose homeostasis (28). Postmenopausal women develop central obesity associated with insulin resistance and increased risk for type 2 diabetes, whereas estrogen replacement decreases the incidence of diabetes (16, 29). Similarly, female mice are less prone to diabetes (41). Ovariectomy reduces insulin sensitivity and insulin secretion, whereas estradiol treatment improves these parameters (18). In our study, EST expression in female WAT decreased insulin sensitivity in WAT but increased insulin sensitivity in liver. On the other hand, soleus/gastrocnemius insulin sensitivity was not altered by EST overexpression in WAT. It is important to point out that we did not assess insulin-mediated glucose uptake in other muscle groups and BAT, which may explain the discrepancy in glucose Rd in the clamp studies. It is unknown whether the reduction in adipocyte size or changes in the ratio of estrogen and estrogen sulfate were directly responsible for the reduction in insulin sensitivity in EST transgenic WAT. Although MCP1 and IL-β mRNA levels tended to be elevated in EST transgenic WAT, these changes were not significant. Moreover, the expression of a macrophage biomarker, F4/80, was not different between WT and EST transgenic WAT, casting doubt on a major contribution of inflammation. Total and HMW adiponectin, which have been associated with enhancement of insulin sensitivity, were also not different in EST transgenic and WT mice (23).

The female EST transgenic mouse model provides new insights into how estrogen inactivation affects WAT and glucose homeostasis. At this stage, the role of EST in human physiology and pathology is unknown (9). Further studies are needed to evaluate the levels and activity of EST in various adipose depots in men and women and whether these are altered during menopause and in hyperandrogenic states such as polycystic ovarian syndrome. Moreover, it is important to determine whether changes in the ratio of active and inactive estrogen by EST contribute to the sexual dimorphism of fat mass and distribution, glucose and lipid metabolism, and cardiovascular diseases (8, 27, 31).

GRANTS

V. K. Khor was supported a fellowship award from the Institute for Diabetes, Obesity and Metabolism of the University of Pennsylvania. Research support was provided by National Institute of Health grants RO1-DK-062348, PO1-DK-049210 (R. S. Ahima), HD-042767 (W.-C. Song), and Diabetes and Endocrinology Research Center Mouse Metabolic Phenotyping Core and Transgenic and Chimeric Mouse Facility (P30-DK-19525). Adipose histology was performed by the Center for Molecular Studies of Digestive and Liver Disease (P30-DK-50306).

DISCLOSURE

No conflicts of interest are reported by the authors.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. Ormond MacDougald for the aP2 promoter.

REFERENCES

- 1. Ahima RS, Dushay J, Flier SN, Prabakaran D, Flier JS. Leptin accelerates the onset of puberty in normal female mice. J Clin Invest 99: 391– 395, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ahmed-Sorour H, Bailey CJ. Role of ovarian hormones in the long-term control of glucose homeostasis, glycogen formation and gluconeogenesis. Ann Nutr Metab 25: 208– 212, 1981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Akpan I, Goncalves MD, Dhir R, Yin X, Pistilli EE, Bogdanovich S, Khurana TS, Ucran J, Lachey J, Ahima RS. The effects of a soluble activin type IIB receptor on obesity and insulin sensitivity. Int J Obes (Lond) 33: 1265– 1273, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bjorntorp P. Adipose tissue distribution and function. Int J Obes 15, Suppl 2: 67– 81, 1991 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Clegg DJ, Brown LM, Woods SC, Benoit SC. Gonadal hormones determine sensitivity to central leptin and insulin. Diabetes 55: 978– 987, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Diamanti-Kandarakis E, Christakou C, Kandarakis H. Polycystic ovarian syndrome: the commonest cause of hyperandrogenemia in women as a risk factor for metabolic syndrome. Minerva Endocrinol 32: 35– 47, 2007 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dieudonne MN, Leneveu MC, Giudicelli Y, Pecquery R. Evidence for functional estrogen receptors α and β in human adipose cells: regional specificities and regulation by estrogens. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 286: C655– C661, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ding EL, Song Y, Malik VS, Liu S. Sex differences of endogenous sex hormones and risk of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 295: 1288– 1299, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Escobar-Morreale HF, San Millan JL. Abdominal adiposity and the polycystic ovary syndrome. Trends Endocrinol Metab 18: 266– 272, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gambacciani M, Ciaponi M, Cappagli B, Piaggesi L, De Simone L, Orlandi R, Genazzani AR. Body weight, body fat distribution, and hormonal replacement therapy in early postmenopausal women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 82: 414– 417, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gaspard U. Hyperinsulinaemia, a key factor of the metabolic syndrome in postmenopausal women. Maturitas 62: 362– 365, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Geer EB, Shen W. Gender differences in insulin resistance, body composition, and energy balance. Gend Med 6, Suppl 1: 60– 75, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Heine PA, Taylor JA, Iwamoto GA, Lubahn DB, Cooke PS. Increased adipose tissue in male and female estrogen receptor-alpha knockout mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97: 12729– 12734, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jones ME, Boon WC, McInnes K, Maffei L, Carani C, Simpson ER. Recognizing rare disorders: aromatase deficiency. Nat Clin Pract Endocrinol Metab 3: 414– 421, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Jones ME, Thorburn AW, Britt KL, Hewitt KN, Wreford NG, Proietto J, Oz OK, Leury BJ, Robertson KM, Yao S, Simpson ER. Aromatase-deficient (ArKO) mice have a phenotype of increased adiposity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97: 12735– 12740, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kaaja RJ. Metabolic syndrome and the menopause. Menopause Int 14: 21– 25, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Khor VK, Tong MH, Qian Y, Song WC. Gender-specific expression and mechanism of regulation of estrogen sulfotransferase in adipose tissues of the mouse. Endocrinology 149: 5440– 5448, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kumagai S, Holmang A, Bjorntorp P. The effects of oestrogen and progesterone on insulin sensitivity in female rats. Acta Physiol Scand 149: 91– 97, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Longo KA, Wright WS, Kang S, Gerin I, Chiang SH, Lucas PC, Opp MR, MacDougald OA. Wnt10b inhibits development of white and brown adipose tissues. J Biol Chem 279: 35503– 35509, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Macotela Y, Boucher J, Tran TT, Kahn CR. Sex and depot differences in adipocyte insulin sensitivity and glucose metabolism. Diabetes 58: 803– 812, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mayes JS, Watson GH. Direct effects of sex steroid hormones on adipose tissues and obesity. Obes Rev 5: 197– 216, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Musatov S, Chen W, Pfaff DW, Mobbs CV, Yang XJ, Clegg DJ, Kaplitt MG, Ogawa S. Silencing of estrogen receptor alpha in the ventromedial nucleus of hypothalamus leads to metabolic syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104: 2501– 2506, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Pajvani UB, Du X, Combs TP, Berg AH, Rajala MW, Schulthess T, Engel J, Brownlee M, Scherer PE. Structure-function studies of the adipocyte-secreted hormone Acrp30/adiponectin. Implications for metabolic regulation and bioactivity. J Biol Chem 278: 9073– 9085, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Price TM, O'Brien SN. Determination of estrogen receptor messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) and cytochrome P450 aromatase mRNA levels in adipocytes and adipose stromal cells by competitive polymerase chain reaction amplification. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 77: 1041– 1045, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Qian YM, Song WC. Regulation of estrogen sulfotransferase expression in Leydig cells by cyclic adenosine 3′,5′-monophosphate and androgen. Endocrinology 140: 1048– 1053, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Qian YM, Sun XJ, Tong MH, Li XP, Richa J, Song WC. Targeted disruption of the mouse estrogen sulfotransferase gene reveals a role of estrogen metabolism in intracrine and paracrine estrogen regulation. Endocrinology 142: 5342– 5350, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Regitz-Zagrosek V, Lehmkuhl E, Mahmoodzadeh S. Gender aspects of the role of the metabolic syndrome as a risk factor for cardiovascular disease. Gend Med 4, Suppl B: S162– S177, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ropero AB, Alonso-Magdalena P, Quesada I, Nadal A. The role of estrogen receptors in the control of energy and glucose homeostasis. Steroids 73: 874– 879, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Salpeter SR, Walsh JM, Ormiston TM, Greyber E, Buckley NS, Salpeter EE. Meta-analysis: effect of hormone-replacement therapy on components of the metabolic syndrome in postmenopausal women. Diabetes Obes Metab 8: 538– 554, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Seale P, Bjork B, Yang W, Kajimura S, Chin S, Kuang S, Scime A, Devarakonda S, Conroe HM, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Rudnicki MA, Beier DR, Spiegelman BM. PRDM16 controls a brown fat/skeletal muscle switch. Nature 454: 961– 967, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Shi H, Clegg DJ. Sex differences in the regulation of body weight. Physiol Behav 97: 199– 204, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Shi H, Seeley RJ, Clegg DJ. Sexual differences in the control of energy homeostasis. Front Neuroendocrinol 30: 396– 404, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Simpson ER, Ackerman GE, Smith ME, Mendelson CR. Estrogen formation in stromal cells of adipose tissue of women: induction by glucocorticosteroids. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 78: 5690– 5694, 1981 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Singhal NS, Patel RT, Qi Y, Lee YS, Ahima RS. Loss of resistin ameliorates hyperlipidemia and hepatic steatosis in leptin-deficient mice. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 295: E331– E338, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Song WC, Moore R, McLachlan JA, Negishi M. Molecular characterization of a testis-specific estrogen sulfotransferase and aberrant liver expression in obese and diabetogenic C57BL/KsJ-db/db mice. Endocrinology 136: 2477– 2484, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Strott CA. Steroid sulfotransferases. Endocr Rev 17: 670– 697, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Tong MH, Christenson LK, Song WC. Aberrant cholesterol transport and impaired steroidogenesis in Leydig cells lacking estrogen sulfotransferase. Endocrinology 145: 2487– 2497, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Tong MH, Song WC. Estrogen sulfotransferase: discrete and androgen-dependent expression in the male reproductive tract and demonstration of an in vivo function in the mouse epididymis. Endocrinology 143: 3144– 3151, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Varela GM, Antwi DA, Dhir R, Yin X, Singhal NS, Graham MJ, Crooke RM, Ahima RS. Inhibition of ADRP prevents diet-induced insulin resistance. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 295: G621– G628, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wade GN, Gray JM. Cytoplasmic 17 beta-[3H]estradiol binding in rat adipose tissues. Endocrinology 103: 1695– 1701, 1978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Wade GN, Gray JM, Bartness TJ. Gonadal influences on adiposity. Int J Obes 9, Suppl 1: 83– 92, 1985 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]