Abstract

The life-threatening infections caused by Leptospira serovars remain a global challenge since long time. Prevention of infection by controlling environmental factors being difficult to practice in developing countries, there is a need for designing potent anti-leptospirosis drugs. ATP-dependent MurD involved in biosynthesis of peptidoglycan was identified as common drug target among pathogenic Leptospira serovars through subtractive genomic approach. Peptidoglycan biosynthesis pathway being unique to bacteria and absent in host represents promising target for antimicrobial drug discovery. Thus, MurD 3D models were generated using crystal structures of 1EEH and 2JFF as templates in Modeller9v7. Structural refinement and energy minimization of the model was carried out in Maestro 9.0 applying OPLS-AA 2001 force field and was evaluated through Procheck, ProSA, PROQ, and Profile 3D. The active site residues were confirmed from the models in complex with substrate and inhibitor. Four published MurD inhibitors (two phosphinics, one sulfonamide, and one benzene 1,3-dicarbixylic acid derivative) were queried against more than one million entries of Ligand.Info Meta-Database to generate in-house library of 1,496 MurD inhibitor analogs. Our approach of virtual screening of the best-ranked compounds with pharmacokinetics property prediction has provided 17 novel MurD inhibitors for developing anti-leptospirosis drug targeting peptidoglycan biosynthesis pathway.

Keywords: Peptidoglycan biosynthesis, Leptospirosis, Virtual high-throughput screening, MurD inhibitors

Introduction

The widespread emergence of bacterial resistance to existing antibiotics is a global health threat and has emphasized the need to develop new antibacterial agents directed toward novel targets [1]. Human leptospirosis that caused by spirochete pathogen Leptospira interrogans is a worldwide zoonosis of global concern [2, 3]. The disease displays the danger of epidemic through contaminated water, rodents, or pets. Thus, deadly outbreaks may result during post-flood conditions. People exposed to infected animals and contaminated water due to their occupational compulsions such as recreational activities and farming are also at major risk of getting infected by leptospirosis [4, 5]. Due to wide range of wild reservoirs for the pathogen Leptospira, prevention of infection by controlling environmental factors is difficult to practice in developing countries. Either an effective and safe leptospirosis vaccine or a potent drug for treatment of severe form of leptospirosis is yet to be invented [6, 7]. Thus, structure-based virtual screening procedure would be highly useful for discovery of potential inhibitors targeting novel common drug targets identified from pathogenic L. interrogans serovars through subtractive genomic approach [data not shown].

Leptospira is a Gram-negative bacterium; hence, peptidoglycan is an important component to provide structural integrity to the cell wall. The peptidoglycan is traditionally a target of choice with respect to selective toxicity [8]. Properly constructed peptidoglycan provides rigidity, flexibility, and strength that are necessary for bacterial cells to grow and divide, while withstanding high internal osmotic pressure [9]. Peptidoglycan is composed of a β-1,4-linked glycans of alternating N-acetyl-glucosamine and N-acetyl-muramic acid sugar [10]. Among the intracellular stages of bacterial peptidoglycan biosynthesis, the ATP-dependent Mur ligases (MurC, MurD, MurE, and MurF) deserve particular attention. These enzymes successively add L-Ala, D-Glu, meso-A2pm or L-Lys, and D-Ala-D-Ala to the nucleotide precursor, UDP-MurNAc, and they represent promising targets for antibacterial drug discovery [8]. The present study focused on MurD (UDP-N-acetylmuramoylalanine-D-glutamate ligase) from 88 common drug targets identified among L. interrogans serovars [data not shown]. MurD catalyzes the formation of the peptide bond between UDP-MurNAc-L-Ala (UMA) and D-Glu. The reaction starts by phosphorylation of UMA to form an acylphosphate, followed by nucleophilic attack by the amino group of the incoming D-Glu. A high-energy tetrahedral intermediate is formed, which eventually collapses to yield UDP-MurNAc-L-Ala-D-Glu, ADP, and inorganic phosphate [11]. High specificity, ubiquity among bacteria, and absence in mammals make MurD a promising target for antibacterial therapy [12].

In this paper, L. interrogans MurD 3D structure was constructed using homology modeling technique. Structural refinement and energy minimization of built 3D model was done using Maestro 9.0. The structural quality of the predicted model was verified using Procheck, ProSA, PROQ, and Profile 3D. Validity of the model was assessed by docking natural substrates (UMA and D-glutamic acid) and published MurD inhibitors (phosphinic, sulfonamide, and benzene 1,3-dicarbixylic acid derivatives) [13–15]. The purpose of the present study was to use virtual high-throughput screening (VHTS) to find novel inhibitors of the MurD followed by scoring and ranking of the compounds to identify potential hits. The novel inhibitors proposed here would be highly useful for developing antimicrobial drug against leptospirosis.

Materials and methods

Hardware and software

The present work was carried out in Sun Microsystems SGI Fuel Workstation with 3.0 GHz processor, 4 GB RAM, 300 GB hard drive, and an Nvidia FX 1700 graphics card running in Linux operating system. Modeller9v7 [16], Schrodinger 2009 [17], and online bioinformatics resources were employed to propose the research findings.

Homology modeling of MurD

MurD was selected as drug target against pathogenic Leptospira through subtractive genomic approach. The sequence of L. interrogans MurD was obtained from the Uniprot. The protein primary sequence was analyzed using ProtParam [18], and secondary structure was predicted using PSI-PRED [19]. A Pfam [20] search yielded conserved domains. SCOP [21] analysis was performed to detect domains based on similarity from experimental structures. The involvement of the drug target in pathogens metabolic pathways were analyzed at the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genome [22]. Local alignments were predicted using Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLASTP) [23] at the NCBI and homologous entries were obtained from the Protein Data Bank (PDB). Cocrystallized structure of Escherichia coli MurD with substrate UMA (PDB ID:1EEH) [24] was chosen as template. The BLASTP alignment was further refined using ClustalX [25]. The sequence alignment file was used as input to the Modeller9v7 [16] to construct homology models for L. interrogans MurD in complex with UMA. A bundle of 20 models from random generation of the starting structure was calculated, and the best model (structure with lowest DOPE score) was subjected for further analysis. To gain better relaxation and more correct arrangement of the atoms, refinement was done on the built Leptospira MurD model using Maestro 9.0 by applying OPLS-AA 2001 force field [17]. Similarly, L. interrogans MurD 3D model in complex with D-Glu containing sulfonamide inhibitor (LK2) was predicted based on crystal structure of 2JFF to obtain residue details of D-glutamic acid binding site [26]. The models and their features were visualized to list UMA and LK2 binding residues with Maestro 9.0 [17]. The model generated in complex with UMA was selected for further validation and virtual screening.

Evaluation of model quality

The stereochemical parameters of the energy minimized MurD model were assessed by Procheck, ProSA, ProQ [27–29], and Profile 3D [16]. Procheck and ProSA are optimized to find native structures, while ProQ is a neural network-based predictor that is based on a number of structural features to predict the quality of a protein model. The target and template Density Optimization Potential Energy (DOPE) profiles were plotted using gnuplot (http://www.gnuplot.info/), and Modeller SuperPose command was used to superimpose the 3D structures of template and target [16]. The developed 3D model of L. interrogans MurD was submitted to Protein Model Data Base (PMDB) [30], which collects 3D models obtained by structure prediction methods.

Ligand-based VHTS

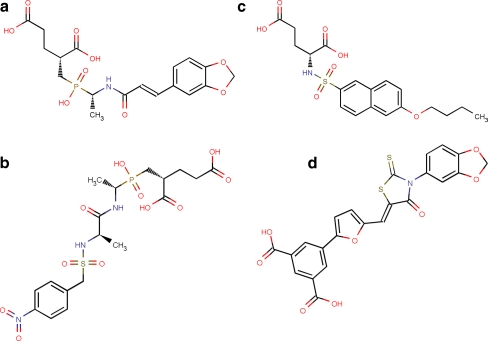

The Ligand.Info tool can interactively cluster sets of molecules on the user side and automatically download similar molecules from the server. The low-molecular-weight phosphinates (Fig. 1a and b) [13], N-sulfonyl derivative (Fig. 1c) [14], and benzene 1,3-dicarboxylic acid derivative (Fig. 1d) [15] MurD inhibitors were searched for structural analogs against Ligand.Info Meta-Database [31]. The top 50 structural analogs for each inhibitors were downloaded from each sub databases such as Havard’s ChemBank, ChemPDB, KEEG Ligand, Druglikeliness National Cancer Institute (NCI), Anti-HIV NCI, Unannotated NCI, AkoS GmhB, Asinex Ltd, etc. [31, 32]. An in-house library of 1,496 MurD inhibitor analogs was generated.

Fig. 1.

a Phosphinate inhibitor 1 (IC50 = 95 ± 15 µM). b Phosphinate inhibitor 2 (IC50 = 78 ± 19 µM). c N-sulfonyl-glutamic acid inhibitor (LK2). d Benzene 1,3-dicarboxylic acid inhibitor (IC50 = 270 µM)

Docking and scoring

All the docking and scoring calculations were performed using the Schrodinger software suite 2009 (Maestro 9.0) [17]. The inhibitor analogs were prepared using LigPrep [33]. A grid box was generated on the receptor (modeled L. interrogans MurD) by picking the active site residues in Glide 5.5 [34]. Maestro 9.0 virtual screening protocol constraints such as Run QikProp, Lipinski filter, and Reactive filter were set to filter ligands with suitable pharmacological property and no reactive functional group. The filters demonstrated ability of screened ligand to follow ADME rule. Glide HTVS and Standard Precision method parameters were checked and set to save 10% of the good scoring ligands [17, 34].

Validation of MurD inhibitors

Maestro 9.0 virtual screening protocol was used to dock MurD natural substrates (UMA and D-glutamic acid) and four published MurD inhibitors (Fig. 1). The Glide score and interaction mode of these compounds with L. interrogans MurD were kept as reference to validate novel MurD inhibitors.

Results and discussion

L. interrogans MurD as drug target

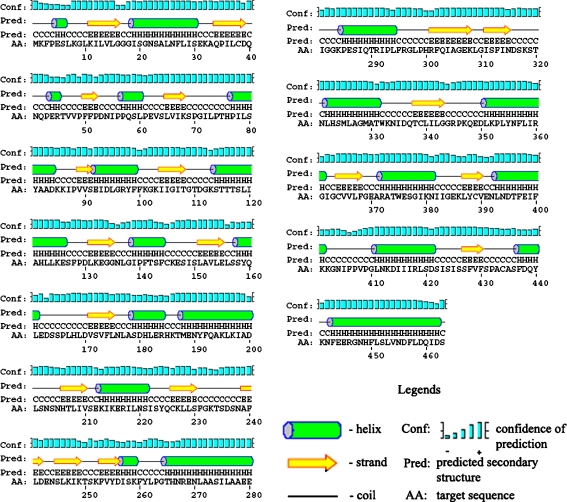

Peptidoglycans are the main constituents of the outer cell wall of Gram-negative bacteria, thus, designing competitive inhibitors against MurD would disintegrate rigidity, flexibility, and strength that are necessary for bacterial cells to grow and divide and making the pathogen prone to osmotic lysis. MurD of L. interrogans is of 463 amino acid length with 51.3 kD molecular weight. The protein is expressed in cytoplasm. A potential ATP binding site was noticed from 109 to 115 amino acid residues [18]. The high confidence level of secondary structure prediction (Fig. 2) would be useful for evaluating protein 3D model [19, 29]. The protein was found having three functional domains. A Pfam search of L. interrogans MurD sequence had detected presence of Mur ligase middle domain (Mur ligase M, IPR013221, Pfam Acc No. PF08245) from 105 to 278 amino acid position and Mur ligase family Glutamate ligase domain (Mur ligase C, IPR004101, Pfam Acc No. PF02875) from 298 to 335 amino acid position [35]. An additional MurD N-terminal domain was predicted from 1 to 93 amino acid regions through SCOP analysis. The N-terminal domain responsible for binding the UDP-substrate, the central domain bearing resemblance to the ATP-binding domains of a number of ATP- or GTP-ases, and a C-terminal domain is involved in the binding of the incoming amino acid [36]. Mur ligases have “closed” and “open” conformations, and the closure of the domains is believed to be caused by ligand binding [36]. The MurD of L. interrogans serovars (Copenhageni and Lai) were showing 99% sequence identity and was highly conserved among the leptospires.

Fig. 2.

Secondary structure diagram for the Leptospira interrogans MurD showing location of secondary structural elements with confidence level of prediction

Homology modeling and model evaluation

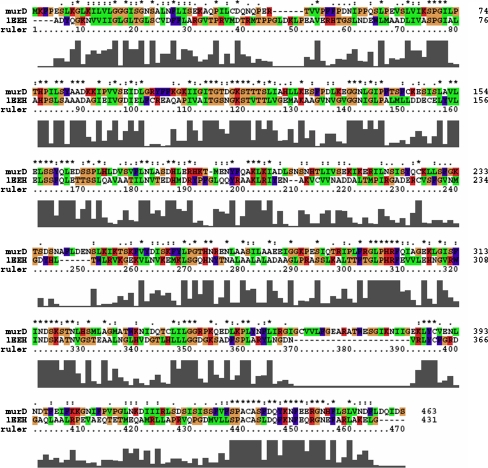

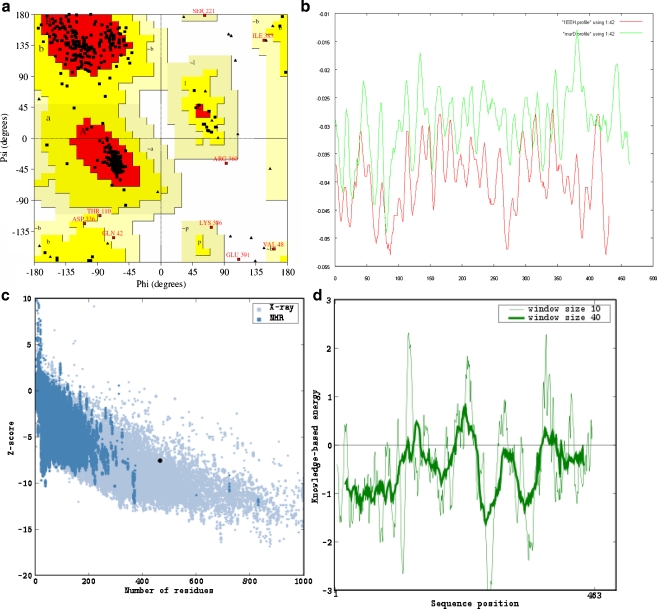

Cocrystallized MurD with UMA (1EEH) and N-sulfonyl-glutamic acid inhibitor (2JFF) from E. coli were two structural homologous proteins found by BLASTP analysis and hence, chosen as templates for developing the Leptospira MurD 3D model. The multiple sequence alignment was followed by pairwise alignment among Leptospira MurD sequence and 1EEH (Fig. 3). A total of 20 models of Leptospira MurD were generated in complex with substrate UMA using Modeller9v7. The substrate UMA was incorporated to the Leptospira MurD 3D model in order to enhance the model prediction accuracy and to detect active site residues. The structure with lowest DOPE score from the bundle of 20-modeled MurD structures was selected for further validation. The DOPE plots of target (Fig. 4a) and template 1EEH had revealed similar 3D profiles. Stereochemistry assessment of model had shown 99.5% residues in favorable region and 0.5% residues in disallowed region and was found to compare favorably with data of crystal structure 1EEH (99.7% in favorable region and 0.3% residues in disallowed region; Fig. 4b). Evaluation of Leptospira MurD 3D model with ProSA-web revealed a Z-score value of −7.54, which is well within the range of native conformations of crystal structures. The ProSA-web analysis had shown that overall the residue energies of the Leptospira MurD 3D model were largely negative (importantly all active site residues were largely negative) except for some peaks in the middle region. The residue energies including pair energy, combined energy, and surface energy are all negative and has similar surface energy tendency with template (Fig. 4c and d). Protein Quality Predictor (ProQ) tool prediction efficiency increases by 15% when the 3D models evaluated along with its secondary structure. The secondary structure (Fig. 2) and 3D model of L. interrogans MurD while submitted to ProQ tool had shown LGscore of 5.045. The result suggests that the model is of extremely good quality [29]. RMS-superimposition of modeled structure was performed to check the structure compatibility with template. The tertiary structure of Leptospira MurD had shown close resemblances to crystallized 1EEH with a Cα RMSD of 0.35 A° and an overall RMSD of 0.69 A°. The low overall RMSD reflect the high structural conservation making it a good system for homology modeling. Through this assessment and analysis process, it can be concluded that the L. interrogans MurD model generated in the present study is reliable to characterize protein–substrate and protein–ligand interactions and to investigate the relation between the structure and function. With all these evaluations the predicted L. interrogans MurD model was submitted to PMBD, and it has accepted the model with less than 3% stereochemical check failures. PMDB ID for the developed L. interrogans MurD model in complex with UMA was PM0075991.

Fig. 3.

Target (Q8F7V4)–template (1EEH) alignment using CLUSTALX

Fig. 4.

a Profile 3D plot of template 1EEH and target Leptospira interrogans MurD. b Ramachandran plot of predicted Leptospira interrogans MurD 3D model. c ProSA-web Z-scores of all protein chains in PDB determined by X-ray crystallography (light blue) and NMR spectroscopy with respect to their length. The Z-score of Leptospira interrogans MurD was present in that range represented in black dot. d Energy plot for the predicted Leptospira interrogans MurD

Active site region

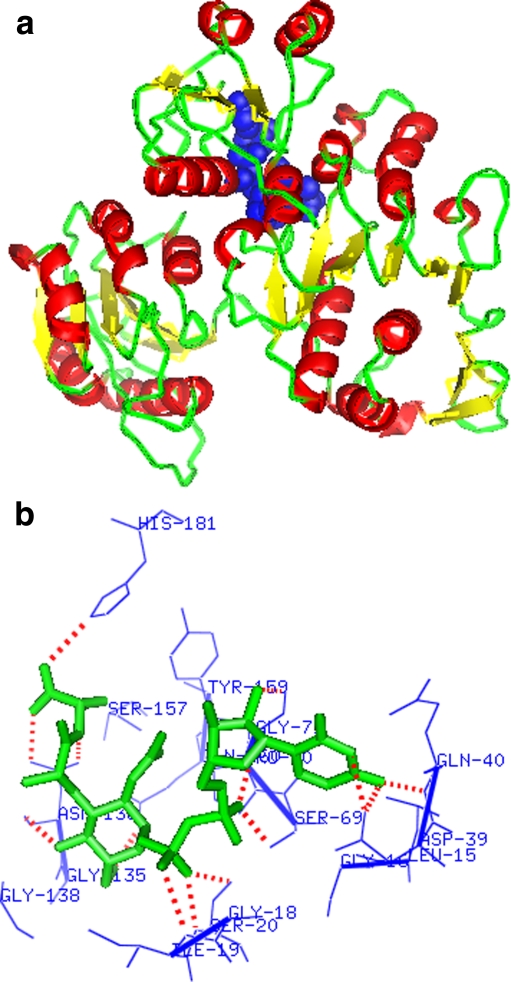

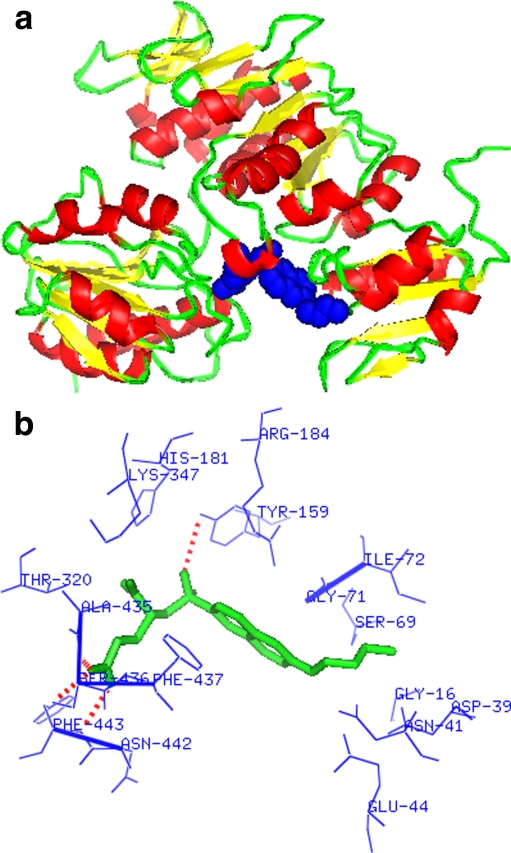

L. interrogans MurD has three ligand-binding sites (UMA, ATP, and D-glutamic acid). These binding site residues were predicted from the model in complex with UMA (Fig. 5a and b) and model in complex with LK2 (Fig. 6a and b). The UMA-binding site residues were Gly16, Gly18, Ile19, Ser20, Gly21, Asp39, Gln40, Asn41, Arg45, Ser69, Pro70, Gly71, Ile72, Lys113, Gly135, Asn136, Gly138, Pro140, Ser157, Tyr159, Gln160, and His181 (Fig. 5b). The residues present in LK2-binding site were Gly16, Asp39, Asn41, Glu44, Ser69, Gly71, Ile72, Tyr159, His181, Arg184, Thr-320, Lys347, Ala435, Ser436, Phe437, Asn442, and Phe443 (Fig. 6b). These binding site residues were reported as important for UMA (N-terminal domain), ATP (MurD middle domain), and D-glutamic acid (MurD ligase C-terminal domain) binding in cocrystallized structures of E. coli [24]. Thus, all these residues were confirmed as L. interrogans MurD active site residues and picked to generate grid in the centroid of these residues for virtual screening.

Fig. 5.

aLeptospira interrogans MurD 3D model in complex with UMA (blue spheres). b The picture showing residues (blue) within 4 A° of UMA forming hydrogen bonds (red dotted lines) with UMA (structures generated using PYMOL, Delano WL. DeLano Scientific LLC, USA, 2005)

Fig. 6.

aLeptospira interrogans 3D model in complex with LK2 (blue spheres). b The picture showing residues (blue) within 4 A° of LK2 (structures generated using PYMOL, Delano WL. DeLano Scientific LLC, USA, 2005)

Lead identification

One of the most widely used methods for VHTS is docking of small molecules into active site of protein target and subsequent scoring. A wide range of different docking programs are available, most of which use semi-rigid docking, where the ligands are treated as flexible and the receptors as rigid. The Glide 5.5 software was used for pro-ligand docking. Glide offers the full spectrum of speed and accuracy from high-throughput virtual screening of millions of compounds to extremely accurate binding mode predictions, providing consistently high enrichment at every level.

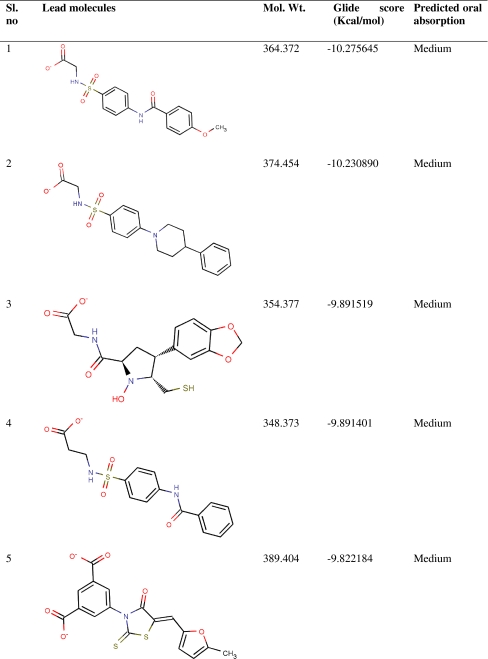

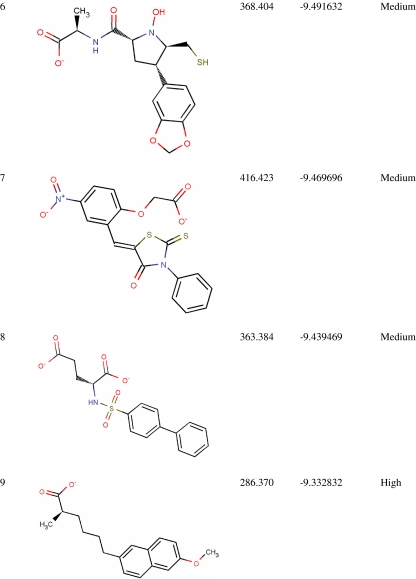

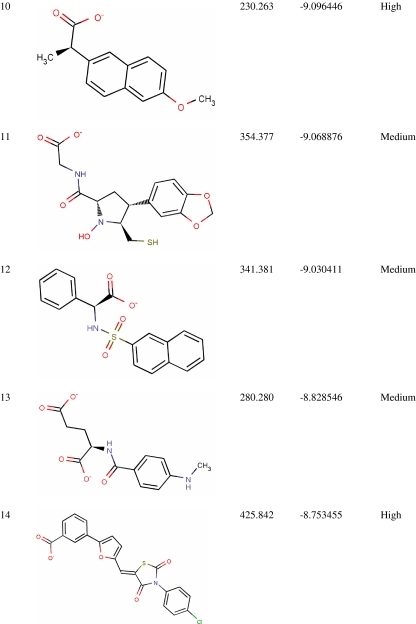

Virtual screening from in-house MurD inhibitor analogs library was performed using Glide 5.5. For this, 4,366 conformers were generated from 1,496 MurD inhibitor analogs. Conformers (2,136) were passed in Lipinski filter and reactive filter from 4,366 conformers. The dataset was further condensed to 213 based on best-scoring ligands through HTVS, out of which 17 ligands were identified as lead candidates through careful inspection of the docking poses and possible interactions with the active site for all of the active compounds. These 17 leads were novel carboxylic acid derivatives and suggested for first time as MurD inhibitor (Table 1). Three inhibitors (5, 8, and 13) were having intact D-Glu fragment [13–15]. All lead molecules were satisfying pharmacological properties of 95% drugs and demonstrated high to medium oral absorption availability. The 10th ranked lead had illustrated 100% oral availability. In decreasing order, lead 1 and lead 17 demonstrated a Glide score of −10.28 and −8.65 Kcal/mol, respectively. Two binding modes were observed while analyzing MurD inhibitor docking complexes. Sixteen leads were well aligned to LK2-binding site, and lead 15 was well aligned to UMA-binding site. Thus, analyzing docking interaction of best ranked lead and 15th ranked lead would signify the mode of MurD competitive inhibition.

Table 1.

Novel Leptospira interrogans MurD inhibitors

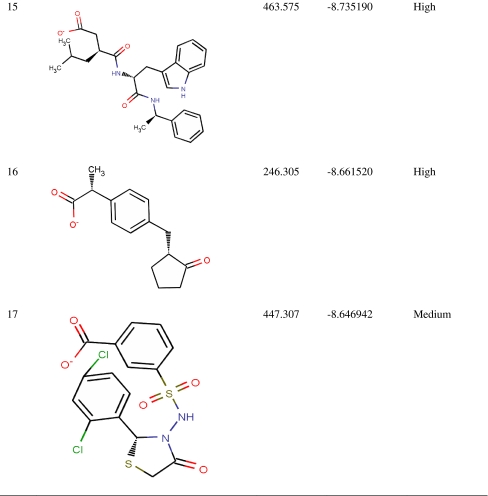

The best ranked lead (Glidescore −10.28 Kcal/mol) had shown an overall 256 good van der Waal contacts and no ugly contacts. The docking complex revealed that Lys125, Leu131, Glu133, Lys132, Gly138, Ile139, Phe144, Lys146, Lys318, Ser319, Thr320, Arg301, Phe302, Asn321, Ser324, Ala327, and Gly328 were involved in good van der Waals interaction; Leu131, Ile139, Phe144, and Ala327 were involved in hydrophobic interaction, and three hydrogen bonds were formed with Asn321, Leu131, and Ser324 (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Molecular docking interactions of best ranked lead and Leptospira interrogans MurD. The protein is shown in ribbons, and ligand in ball and sticks. Hydrogen bonds are shown in red dotted lines

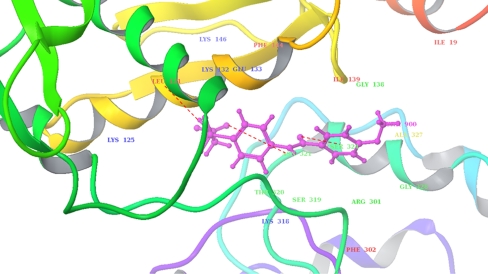

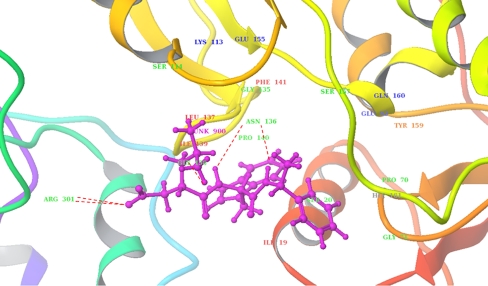

Lead 15 interacted with MurD with a Glidescore of −8.74 Kcal/mol. The MurD 15th lead docking complex revealed an overall 286 good van der Waals contacts and no ugly contacts. Ile19, Ser20, Glu92, Gly71, Lys113, Ser114, Glu115, Gly135, Asn136, Leu137, Gly138, Ile139, Phe141, Ser157, Tyr 159, Gln160, His181, and Arg301 were associated with good van der Waals interaction; Ile19, Leu137, Ile139, Phe141, Tyr159, Pro70, and Pro140 were involved in hydrophobic interaction and Asn136, Arg301, and Gly138 formed five hydrogen bonds (two hydrogen bonds with each of Asn136, Arg301, and one with Gly138; Fig. 8).

Fig. 8.

Docking interactions of 15th ranked lead and Leptospira interrogans MurD. The protein is shown in ribbons, and ligand in ball and sticks. Hydrogen bonds are shown in red dotted lines

In silico validation of lead candidates as potential MurD inhibitors

UMA, D-glutamic acid, and four reference inhibitors (Fig. 1) were docked flexibly into L. interrogans MurD active site for validation of identified lead candidates as inhibitor. UMA was docked to MurD with a Glide score of −6.97 Kcal/mol with seven hydrogen bonds (two hydrogen bonds with Asn136 and one hydrogen bond each with Ile19, Ser20, Asp39, Lys113, and Gly138). D-Glutamic acid had docked with a Glide score of −5.32 Kcal/mol with three hydrogen bonds (Arg301, Asp316, and Lys318). The docking of two phosphinate inhibitors (Fig. 1a and b) with L. interrogans MurD demonstrated a Glidescore of −6.59 and −6.03 Kcal/mol, respectively. The sulfonyl inhibitor (Fig. 1c) demonstrated Glidescore of −9.08 Kcal/mol, and benzene 1,3-dicarboxylic acid derivatives MurD inhibitor (Fig. 1d) had shown Glidescore of −6.54 kcal/mol. The phosphinate inhibitors were well aligned to UMA-binding site and benzene 1,3-dicarboxylic acid derivative inhibitor was aligned to LK2-binding site.

The lower Glidescore (−10.28 to −8.65 Kcal/mol) of identified lead candidates (Table 1) compared to substrates and reference inhibitors (Table 2) in respective docking complexes revealed that the novel leads would bind more competitively into MurD active site than substrate UMA, D-glutamic acid, and existing inhibitors. The binding modes observed in these 17 lead candidates were well aligned with existing MurD inhibitors. Importantly, the involvement of identified lead molecule in blocking substrate binding residues through hydrogen bonding (Asn136, Gly138, Arg301) van der Waals (Ser20, Asp39, Lys318) and hydrophobic interaction (Ile19, Thr320) justified them as potential inhibitors against L. interrogans MurD. These novel inhibitors may be validated in vitro through biochemical assays. MurD being unique to bacterial species and the active site being almost conserved in bacteria, the same inhibitor may also be trialed against other Gram-negative bacterial pathogens in order to design common effective inhibitor.

Table 2.

Summary of docking results of natural substrates and published MurD inhibitors

| Sl. No. | Ligand name | Glide score (Kcal/mol) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | UMA (Natural substrate) | −6.97 |

| 2 | D-Glutamic acid (Natural substrate) | −5.32 |

| 3 | Phosphinate inhibitor-1 | −6.59 |

| 4 | Phosphinate inhibitor-2 | −6.03 |

| 5 | Sulfonyl inhibitor (LK2) | −9.08 |

| 6 | benzene 1,3-dicarboxylic acid derivative inhibitor | −6.54 |

Conclusion

Peptidoglycan biosynthesis pathway is unique to Leptospira and absent in host human. Properly constructed peptidoglycan provides rigidity, flexibility, and strength that are necessary for bacterial cells to grow and divide, while withstanding high internal osmotic pressure. MurD ligase is essential for addition of D-Glu to nucleotide precursor; UDP-MurNAc, thus, is critical for proper construction of peptidoglycans. Metabolic pathway analysis had revealed that no alternative enzyme could add D-Glu to UDP-MurNAc in Leptospira. Thus, Leptospira MurD is of significant interest for novel inhibitor design to overcome the challenges of severe leptospirosis. A high-quality homology model of L. interrogans MurD was reported through computational validation. Our approach employing Glide for virtual screening along with QikProp ADME evaluation provided 17 novel MurD inhibitors. The novel 17 carboxylic acid derivative inhibitors identified through high-throughput virtual screening using L. interrogans MurD homology model would be of interest as common inhibitor against leptospiral serovars. As peptidoglycan biosynthesis pathway is unique to bacteria, the in silico identified MurD inhibitors are likely to be broad spectrum Gram-negative inhibitors if synthesized and tested in animal models.

Acknowledgments

The study was supported by grants from DBT, Ministry of Science and Technology, Government of India, New Delhi. We are grateful to Dr. B. Vengamma, Director, for providing constant support and encouragement for research at SVIMS Bioinformatics Centre, where this work has been performed. We thank Prof. S. Ramakumar, IISc., Bangalore for rendering critical valuable suggestions on the present work.

References

- 1.Chopra I, Schofield C, Everett M, O'Neill A, Miller K, Wilcox M, Frère JM, Dawson M, Czaplewski L, Urleb U, Courvalin P. Treatment of health-care-associated infections caused by Gram-negative bacteria: a consensus statement. Lancet Infect Dis. 2008;8:133–9. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(08)70018-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization Leptospirosis worldwide. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 1999;74:237–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bharti AR, Nally JE, Ricaldi JN, Matthias MA, Diaz MM, Lovett MA, Levett PN, Gilman RH, Willig MR, Gotuzzo E, Vinetz JM. Leptospirosis: a zoonotic disease of global importance. The Lancet Infect Dis. 2003;3:757–771. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(03)00830-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Trueba G, Zapata S, Madrid K, Cullen P, Haake D. Cell aggregation: a mechanism of pathogenic Leptospira to survive in fresh water. Int Microbiol. 2004;7:35–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Levett PN. Leptospirosis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2001;14:296–326. doi: 10.1128/CMR.14.2.296-326.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guidugli F, Castro AA, Atallah Antibiotics for preventing leptospirosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2000;4:CD001305. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang Z, Jin L, Wegrzyn A. Leptospirosis vaccines. Microb Cell Fact. 2007;6:39. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-6-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barreteau H, Kovac A, Boniface A, Sova M, Gobec S, Blanot D. Cytoplasmic steps of peptidoglycan biosynthesis. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2008;32:168–207. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2008.00104.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vollmer W, Blanot D, Pedro MA. Peptidoglycan structure and architecture. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2008;32:149–67. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2007.00094.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heijeinoot J. Recent advances in the formation of bacterial peptidoglycan monomer unit. Nat Prod Rep. 2001;18:503–519. doi: 10.1039/a804532a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bouhss A, Dementin S, Heijenoort J, Parquet C, Blanot D. MurC and MurD synthetases of peptidoglycan biosynthesis: borohydride trapping of acyl-phosphate intermediates. Methods Enzymol. 2002;354:189–196. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(02)54015-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.El Zoeiby A, Sanschagrin F, Levesque RC. Structure and function of the Mur enzymes: development of novel inhibitors. Mol Microbiol. 2003;47:1–12. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03289.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Strancar K, Blanot D, Gobec S. Design, synthesis and structure-activity relationships of new phosphinate inhibitors of MurD. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2006;16:343–348. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2005.09.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Humljan J, Kotnik M, Contreras-Martel C, Blanot D, Urleb U, Dessen A, Solmajer T, Gobec S. Novel naphthalene-N-sulfonyl-D-glutamic acid derivatives as inhibitors of MurD, a key peptidoglycan biosynthesis enzyme. J Med Chem. 2008;51:7486–7494. doi: 10.1021/jm800762u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Perdih A, Kovac A, Wolber G, Blanot D, Gobec S, Solmajer T. Discovery of novel benzene 1,3-dicarboxylic acid inhibitors of bacterial MurD and MurE ligases by structure-based virtual screening approach. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2009;19:2668–2673. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2009.03.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eswar N, Eramian D, Webb B, Shen MY, Sali A. Protein structure modeling with MODELLER. Methods Mol Biol. 2008;426:145–59. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60327-058-8_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maestro 9.0, versuib 70110, Schrodinger, New York

- 18.Gasteiger E, Hoogland C, Gattiker A, Duvaud S, Wilkins MR, Appel RD, Bairoch A (2005) Protein Identification and Analysis Tools on the ExPASy Server. In: John M. Walker (ed) The Proteomics Protocols Handbook. Humana Press, pp 571–607

- 19.Bryson K, McGuffin LJ, Marsden RL, Ward JJ, Sodhi JS, Jones DT. Protein structure prediction servers at University College London. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:W36–W38. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sonnhammer EL, Eddy SR, Birney E, Bateman A, Durbin R. Pfam: multiple sequence alignments and HMM-profiles of protein domains. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:320–322. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.1.320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Murzin AG, Brenner SE, Hubbard T, Chothia C. SCOP: a structural classification of proteins database for the investigation of sequences and structures. J Mol Biol. 1995;247:536–540. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1995.0159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kanehisa M, Goto S. KEGG: Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:27–30. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schäffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman DJ. Gapped BLAST and PSI BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bertrand JA, Fanchon E, Martin L, Chantalat L, Auger G, Blanot D, Heijenoort J, Dideberg O. Open structures of MurD: domain movements and structural similarities with folylpolyglutamate synthetase. J Mol Biol. 2000;301:1257–1266. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thompson JD, Gibson TJ, Plewniak F, Jeanmougin F, Higgins DG. The ClustalX windows interface: flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;24:4876–4882. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.24.4876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kotnik M, Humljan J, Contreras-Martel C, Oblak M, Kristan K, Hervé M, Blanot D, Urleb U, Gobec S, Dessen A, Solmajer T. Structural and functional characterization of enantiomeric glutamic acid derivatives as potential transition state analogue inhibitors of MurD ligase. J Mol Biol. 2007;370:107–115. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.04.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Laskowski RA, MacArthur MW, Moss DS, Thornton JM. PROCHECK: a program to check the stereochemical quality of protein structures. J Appl Crystallogr. 1993;26:283–291. doi: 10.1107/S0021889892009944. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wiederstein M, Sippl MJ. ProSA-web: interactive web service for the recognition of errors in three-dimensional structures of proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:W407–W410. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wallner B, Elofsson A. Can correct protein models be identified? Protein Sci. 2003;12:1073–1086. doi: 10.1110/ps.0236803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Castrignano T, Meo PD, Cozzetto D, Talamo IG, Tramontano A. The PMDB protein model database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:D306–9. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Grotthuss M, Pas J, Rychlewski L. Ligand-Info, searching for similar small compounds using index profiles. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:1041–1042. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Plewczynski D, Hoffmann M, Grotthuss M, Ginalski K, Rychewski L. In silico prediction of SARS protease inhibitors by virtual high throughput screening. Chem Biol Drug Des. 2007;69:269–279. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-0285.2007.00475.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brooks WH, Daniel KG, Sung SS, Guida WC. Computational validation of the importance of absolute stereochemistry in virtual screening. J Chem Inf Model. 2008;48:639–645. doi: 10.1021/ci700358r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Friesner RA, Banks JL, Murphy RB, Halgren TA, Klicic JJ, Mainz DT, Repasky MP, Knoll EH, Shelley M, Perry JK, Shaw DE, Francis P, Shenkin PS. Glide: a new approach for rapid, accurate docking and scoring. 1. Method and assessment of docking accuracy. J Med Chem. 2004;47:1739–1749. doi: 10.1021/jm0306430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Faine S, Adler B, Bolin C, Perolat P (1999) Appendix 2 Species and serovar list. In: Leptospira and leptospirosis, 2nd edn. Medisci, Melbourne, Australia, pp 138–139

- 36.Smith CS. Structure, function and dynamics in the Mur family of bacterial cell wall ligases. J Mol Biol. 2006;362:640. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.07.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]