The recent study by Jin et al [1] provides estimates of infectiousness of anal intercourse (AI, insertive circumcised and uncircumcised; receptive with and without ejaculation) for the male homosexual population of Sydney, Australia in the highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) era. There is a lack of estimates of HIV infectiousness for homosexual men and for AI in general and especially for infectiousness with treatment. A recent literature review found only four studies reporting estimates of HIV transmissibility per AI act [2]. Therefore the additional data presented by Jin et al [1] are an important contribution to the literature. There are many methodological challenges when quantifying HIV infectiousness which have been discussed elsewhere [3, 4]. While the best study design for quantifying per-act HIV infectiousness for heterosexual populations has involved discordant monogamous couples (albeit compromised with its own set of biases), these types of study have been seldom used for homosexual populations. It may be more difficult to recruit such participants if rates of monogamy are lower than among heterosexual populations, and monogamous couples may also not be very representative of the wider male homosexual community. The alternative approach used by Jin et al was to follow up initially HIV seronegative homosexual men, testing annually for seroconversion and interviewing every six months for reports of types and frequencies of sexual exposure and the presumed serostatus of their sexual partners (categorised as HIV negative, positive, unknown). A similar approach has been used before for AI by Vittinghoff et al [5] as well as for female sex workers [6, 7]. However Vittinghoff et al were unable to provide per-act estimates per positive exposure for insertive AI, only providing estimates per-act with an “infected or unknown serostatus” partner and therefore may underestimate infectiousness per exposure, if HIV prevalence among unknown serostatus partners is low.

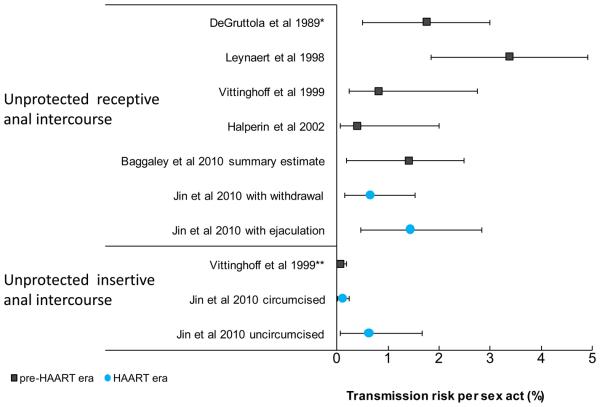

Jin et al's per-act AI transmission probability estimates for receptive unprotected AI (0.65% 95%CI 0.15-1.53% with withdrawal; 1.43% 95%CI 0.48-2.85% with ejaculation [1]), from a population with high (proposed 70%) HAART coverage, are remarkably similar to those estimates made preceding HAART (summary of four estimates: 1.4% 95%CI 0.2-2.5%, no differentiation by ejaculation [2], see Figure). As the authors note, this result is surprising, given the reduction in community viral load that has been observed in some other homosexual populations following the introduction of HAART [8], and that such reductions in viral load are expected to reduce HIV infectiousness.

Per act HIV infectiousness for anal intercourse, for the pre-HAART and HAART eras.

Baggaley et al summary estimate is a combined estimate for the four studies shown above it (DeGruttola et al [9], Leynaert et al [10], Vittinghoff et al [5] and Halperin et al [11]). Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals except for DeGruttola et al [9] where they represent the authors' range of plausible infectiousness estimates.

* No central estimate given.

** Vittinghoff et al insertive anal intercourse estimate is per act with a partner infected or of unknown serostatus (all other estimates represent HIV infectiousness per act with an infected partner).

Potential reasons why HIV infectiousness was not seen to reduce include higher infectiousness associated with various cofactors (STI prevalence may be higher in male homosexual communities now, perhaps as a result of risk compensation in the HAART era); there may be unreported competing exposures through other routes of transmission, such as intravenous drug use; or the partners of study participants may not have been representative of the wider Australian homosexual population, for example, with lower HAART coverage. It would have been useful to have more information regarding the likely HAART coverage of the infected partners, in order to assess how concerning these unexpectedly high estimates for infectiousness are. While authors state that 70% of male homosexuals diagnosed in Australia are currently treated, estimates of the proportion of those infected who are diagnosed and also an indication of adherence levels and average viral loads for those individuals receiving treatment are required to improve our understanding.

The authors addressed the uncertainty regarding “unknown” serostatus and presumed HIV negative sexual partners by undertaking uncertainty analysis, varying the HIV prevalence of the “unknown” and presumed HIV negative partner populations by 5%-15% and 0.5-2% respectively, based on prevalence studies from the locality. It would be informative if this analysis could be extended to reflect the uncertainty in HAART coverage levels in order to explore how sensitive the HIV infectiousness estimates are to the assumed proportion of sexual partners on treatment.

However, even in the absence of further information, levels of HAART are likely to be substantial and so the authors' observation that their per-act estimates are not markedly different from those made in the absence of HAART remains a concerning finding. Community viral load studies covering the Sydney population may help to explain these findings, although the association between viral load and HIV infectiousness for sexual transmission, particularly for AI, remains to be definitively proven. It would also be useful, if data are available or for future cohorts, to ascertain the treatment status of infected partners where possible, in order to make estimates of AI infectiousness stratified by treatment status. This study and our review have clearly highlighted the need for more data on HIV infectiousness for sexual transmission among homosexual men [1, 2].

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

We declare that we have no commercial or other association that might pose a conflict of interest.

This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Jin F, Jansson J, Law M, Prestage GP, Zablotska I, Imrie JC, et al. Per-contact probability of HIV transmission in homosexual men in Sydney in the era of HAART. AIDS. 2010;24:907–913. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283372d90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baggaley RF, White RG, Boily MC. HIV transmission risk through anal intercourse: systematic review, meta-analysis and implications for HIV prevention. Int J Epidemiol. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyq057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Powers KA, Poole C, Pettifor AE, Cohen MS. Rethinking the heterosexual infectivity of HIV-1: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2008;8:553–563. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(08)70156-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boily MC, Baggaley RF, Wang L, Masse B, White RG, Hayes RJ, Alary M. Heterosexual risk of HIV-1 infection per sexual act: systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Lancet Infect Dis. 2009;9:118–129. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(09)70021-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vittinghoff E, Douglas J, Judson F, McKirnan D, MacQueen K, Buchbinder SP. Per-contact risk of human immunodeficiency virus transmission between male sexual partners. Am J Epidemiol. 1999;150:306–311. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a010003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gilbert PB, McKeague IW, Eisen G, Mullins C, Gueye NA, Mboup S, Kanki PJ. Comparison of HIV-1 and HIV-2 infectivity from a prospective cohort study in Senegal. Stat Med. 2003;22:573–593. doi: 10.1002/sim.1342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Donnelly C, Leisenring W, Kanki P, Awerbuch T, Sandberg S. Comparison of transmission rates of HIV-1 and HIV-2 in a cohort of prostitutes in Senegal. Bull Math Biol. 1993;55:731–743. doi: 10.1007/BF02460671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Das-Douglas M, Chu P, Santos G-M, Scheer S, McFarland W, Vittinghoff E, Colfax G. Decreases in community viral load are associated with a reduction in new HIV diagnoses in San Francisco. 17th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections; San Francisco. February 2010; Abstract 33. [Google Scholar]

- 9.DeGruttola V, Seage GR, 3rd, Mayer KH, Horsburgh CR., Jr. Infectiousness of HIV between male homosexual partners. J Clin Epidemiol. 1989;42:849–856. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(89)90098-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leynaert B, Downs AM, de Vincenzi I. Heterosexual transmission of human immunodeficiency virus: variability of infectivity throughout the course of infection. European Study Group on Heterosexual Transmission of HIV. Am J Epidemiol. 1998;148:88–96. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Halperin DT, Shiboski SC, Palefsky SC, Padian NS. High level of HIV-1 infection from anal intercourse: a neglected risk factor in heterosexual AIDS prevention. Int Conf AIDS [abstract ThPeC7438] 2002:14. [Google Scholar]