Ca2+-calcineurin-NFAT signaling transmits signals to the nucleus from a wide variety of receptors and is required for developmental events as diverse as axon outgrowth, cardiac morphogenesis, lung morphogenesis, neural crest diversification, epithelial stem cell maintenance, and immune responses. The pathway appears to be particularly dedicated to vertebrate-specific morphogenic events, perhaps reflecting its first evolutionary appearance in vertebrates. Calcineurin-NFAT signaling is the target of the drugs cyclosporin A and FK506 and several viral immune modulators. In addition, its malfunction is implicated in Down’s syndrome, diabetes, and cardiac hypertrophy.

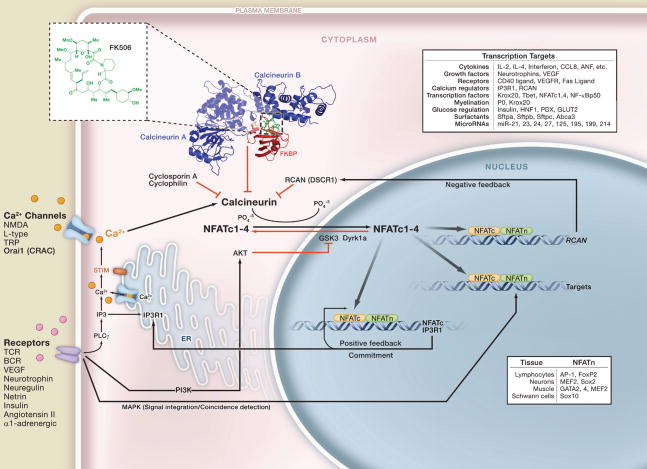

Receptors that induce the entry of Ca2+ into the cell resulting in the activation of calcineurin phosphatase are shown in the lower left. Ca2+ binds to the regulatory subunit of calcineurin as well as to calmodulin to activate the phosphatase activity of calcineurin (Stemmer and Klee, 1994). The immunosuppressive drugs FK506 and cyclosporin A inhibit calcineurin by binding first to the abundant intracellular proteins, FKBP and cyclophilin, respectively. These protein complexes then bind to calcineurin, preventing substrate access (Liu et al., 1991). The specificity of these calcineurin inhibitors is due to the large composite surface arising from FKBP bound to FK506 (see inset structure) (Griffith et al., 1995) or cyclosporin A bound to cyclophilin. FK506 and cyclosporin A are highly specific probes of the NFAT signaling pathway in tissues where the concentration of calcineurin is less than the concentration of FKBP or cyclophilin (Graef et al., 2001). Calcineurin removes several phosphate residues from the N terminus of NFATc proteins, the Ca2+-calcineurin-sensitive subunits of NFAT transcription complexes. Removal of the phosphates exposes nuclear localization sequences in NFATc proteins leading to their rapid entry into the nucleus (Beals et al., 1997a). Once in the nucleus, the NFATc proteins assemble on DNA with partner proteins generically termed NFATn (lower right) that are often the endpoints of other signaling pathways (Crabtree and Olson, 2002). In most cases, NFAT-dependent transcription requires that the Ca2+ signaling be coincident with MAP kinase signaling, providing a mechanism for signal integration and coincidence detection.

The targets of NFAT signaling (panel, upper right) are largely cytokines, growth factors and their receptors, proteins involved in cell-cell interactions, as well as many microRNAs. Of particular importance are positive feedback loops initiated by direct binding of NFATc1 and NFATc4 to their promoters as well as the regulation of Ca2+ channels, such as the IP3 receptor, responsible for the release of intracellular Ca2+ stores (Genazzani et al., 1999). This positive feedback loop appears to be important in committing cells to specific fates. A negative feedback loop mediated by the NFAT-dependent activation of RCAN (DSCR1) gene expression appears to constrain the pathway (Arron et al., 2006).

NFATc proteins are actively removed from the nucleus by first priming with Dyrk1a or protein kinase A (PKA) followed by phosphorylation by GSK3 (Arron et al., 2006; Beals et al., 1997b; Gwack et al., 2006). The inhibition of GSK3 by AKT and PI3 kinase (PI3K) signaling increases the level of NFATc proteins in the nucleus and hence provides a second means of coincidence detection and signal integration. Many of the phenotypes of Down’s syndrome are thought to be due to the duplication of the DSCR and Dyrk1a genes on chromosome 21. Increased gene dosage both reduces NFATc import into the nucleus and also facilitates export leading to a reduction in NFATc function and compromised positive feedback (Arron et al., 2006).

Abbreviations

- AKT

the cellular homolog of the acute transforming oncogene v-AKT

- BCR

B cell receptor

- CRAC

Ca2+ release-activated Ca2+ channel

- DSCR1/RCAN

Down’s syndrome critical region 1, now called regulator of calcineurin

- Dyrk1a

dual-specificity tyrosine-(Y)-phosphorylation regulated kinase 1A

- FKBP

FK506-binding protein

- GSK3

glycogen synthease kinase 3

- IP3R1

inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate receptor 1

- NFAT

nuclear factor of activated T cells

- NMDA

N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor

- NFATc

Ca2+-calcineurin-dependent subunits of NFAT complexes, also cyclosporin-sensitive subunit of NFAT complexes

- NFATn

generic name for nuclear subunits of NFAT-transcription complexes

- NF-κB

nuclear factor binding to the immunoglobulin kappa locus in B cells

- PI3K

phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase

- IP3

inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate

- PLCγ

phospholipase gamma

- STIM

stromal interaction molecule

- Sox2

sex determination-box containing gene

- TRP

transient receptor potential channel

- TCR

T cell receptor

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor

References

- Arron JR, Winslow MM, Polleri A, Chang CP, Wu H, Gao X, Neilson JR, Chen L, Heit JJ, Kim SK, et al. NFAT dysregulation by increased dosage of DSCR1 and DYRK1A on chromosome 21. Nature. 2006;441:595–600. doi: 10.1038/nature04678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beals CR, Clipstone NA, Ho SN, Crabtree GR. Nuclear localization of NF-ATc by a calcineurin-dependent, cyclosporin- sensitive Intramolecular interaction. Genes Dev. 1997a;11:824–834. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.7.824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beals CR, Sheridan CM, Turck CW, Gardner P, Crabtree GR. Nuclear export of NF-ATc enhanced by glycogen synthase kinase-3. Science. 1997b;275:1930–1934. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5308.1930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crabtree GR, Olson EN. NFAT signaling: choreographing the social lives of cells. Cell. 2002;109(Suppl):S67–S79. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00699-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genazzani AA, Carafoli E, Guerini D. Calcineurin controls inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate type 1 receptor expression in neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:5797–5801. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.10.5797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graef IA, Chen F, Chen L, Kuo A, Crabtree GR. Signals transduced by Ca(2+)/calcineurin and NFATc3/c4 pattern the developing vasculature. Cell. 2001;105:863–875. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00396-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffith JP, Kim JL, Kim EE, Sintchak MD, Thomson JA, Fitzgibbon MJ, Fleming MA, Caron PR, Hsiao K, Navia MA. X-ray structure of calcineurin inhibited by the immunophilin-immunosuppressant FKBP12–FK506 complex. Cell. 1995;82:507–522. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90439-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gwack Y, Sharma S, Nardone J, Tanasa B, Iuga A, Srikanth S, Okamura H, Bolton D, Feske S, Hogan PG, et al. A genome-wide Drosophila RNAi screen identifies DYRK-family kinases as regulators of NFAT. Nature. 2006;441:646–650. doi: 10.1038/nature04631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Farmer JD, Jr, Lane WS, Friedman J, Weissman I, Schreiber SL. Calcineurin is a common target of cyclophilin-cyclosporin A and FKBP-FK506 complexes. Cell. 1991;66:807–815. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90124-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stemmer PM, Klee CB. Dual calcium ion regulation of calcineurin by calmodulin and calcineurin B. Biochemistry. 1994;33:6859–6866. doi: 10.1021/bi00188a015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]