ABSTRACT

Purpose: This report highlights the current international gap between the availability of high-quality evidence for pulmonary rehabilitation (PR) and its low level of implementation. Key barriers are outlined, and potentially effective strategies to improve implementation are presented.

Summary of key points: Although pulmonary rehabilitation (PR) is recommended by international guidelines as part of the management of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), participation in PR remains low. Physician referral to PR ranges from 3% to 16% of suitable patients. Barriers to participation include limited availability of suitable programmes and interrelated issues of referral and access. Individual patient barriers, including factors relating to comorbidities and exacerbations, perceptions of benefit, and ease of access, contribute less overall to low participation rates. Chronic care programmes that incorporate self-management support have some benefit in patients with COPD. However, the demonstrated cost-effectiveness of PR is substantial, and efforts to improve its implementation are urgently indicated.

Conclusion: To improve implementation, a holistic examination of the key issues influencing a patient's participation in PR is needed. Such an examination should consider the relative influences of environmental (e.g., health-service-related) factors, organizational factors (e.g., referral and intake procedures), and individual factors (e.g., patient barriers) for all participants. On the basis of these findings, policy, funding, service delivery, and other interventions to improve participation in PR can be developed and evaluated.

Key Words: COPD, evidence translation, guidelines, implementation, pulmonary rehabilitation

RÉSUMÉ

Objectif : Ce rapport fait état des disparités actuelles, à l'échelle internationale, entre la disponibilité de preuves cliniques de qualité relatives à la réadaptation pulmonaire et de son faible taux de mise en œuvre. Un résumé des principaux obstacles et une présentation des stratégies qui pourraient s'avérer efficaces pour en améliorer l'utilisation sont proposés.

Résumé des principaux points : Même si la réadaptation pulmonaire (RP) est recommandée dans les directives internationales pour la gestion des patients qui souffrent de maladies pulmonaires obstructives chroniques (MPOC), la participation à une telle forme de réadaptation demeure faible. La proportion de patients qui y sont dirigés par les médecins s'échelonne entre 3 % et 16 % de tous les patients qui pourraient en bénéficier. Les obstacles à la participation sont notamment la disponibilité limitée de programmes adéquats et les enjeux interdépendants de l'aiguillage des patients vers ces programmes et de leur disponibilité. Les obstacles chez les patients eux-mêmes, notamment les facteurs liés aux comorbidités et aux épisodes d'aggravation, à la perception quant aux bienfaits de telles interventions et à leur facilité d'accès contribuent à un degré moindre, dans l'ensemble, au faible taux de participation. Les programmes de soins pour les maladies chroniques qui incluent une aide à l'autogestion de la maladie sont effectivement bénéfiques pour les patients qui souffrent de MPOC. Toutefois, la rentabilité de cette forme de réadaptation est considérable et des efforts pour en améliorer le déploiement devraient être entrepris rapidement.

Conclusion : Pour améliorer la mise en œuvre de la RP, un examen approfondi des grands enjeux qui influent sur la participation des patients est nécessaire. Cette analyse devrait se pencher sur l'influence relative de facteurs environnementaux (c.-à-d. liés aux services de santé), organisationnels (procédures d'aiguillage des patients et d'accès) et individuels (obstacles du patient lui-même) chez tous les participants. À partir de ces conclusions, des politiques, un financement, la prestation de services et d'autres interventions visant à améliorer la participation à la RP pourront être mis en place, puis évalués.

Mots clés : application de l'expérience clinique, directives, mise en œuvre, MPOC, réadaptation pulmonaire

INTRODUCTION

During the last decade, evidence for the effectiveness of pulmonary rehabilitation in the management of people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) has become irrefutable. Pulmonary rehabilitation (PR), including supervised exercise training, improves exercise tolerance,1,2 reduces dyspnoea, improves health-related quality of life, reduces fatigue,1 and reduces anxiety and depression.3 Participation in PR also significantly reduces the direct costs of COPD by decreasing unnecessary use of the health care system, particularly unplanned hospital admissions.4,5 Emerging evidence demonstrates that PR initiated immediately after exacerbations of COPD also reduces hospitalizations and improves exercise capacity and quality of life relative to standard care.6 On the basis of this high-level evidence, PR is recommended in national and international guidelines for management of patients with moderate to severe COPD.7–10 In addition, evidence for the effectiveness of PR in other chronic lung diseases causing dyspnoea continues to grow, with demonstrated improvements in exercise tolerance and quality of life for patients with interstitial lung disease.11,12 Calls to implement PR are being directed to primary-care physicians, public-health agencies, insurers, and funders.

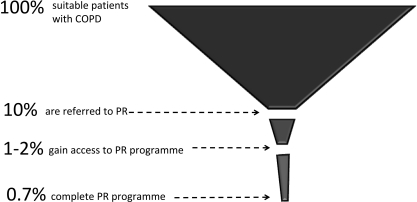

However, participation of patients in PR is reported to be consistently low around the world. Based on surveys of PR providers, authors in Canada,13 Australia,14 and the United Kingdom15 report that only 1–2% of suitable patients with COPD are receiving this intervention. Given the health and cost benefits of PR for individuals with disabling disease states, we should question why this figure is not higher. There is no clear definition of the disease-specific, socio-economic, or environmental characteristics of those who participate in PR compared with those who do not. This makes it difficult to determine how health care providers may better facilitate non-attending patients' participation in such programmes. The aims of this review were to (1) examine the evidence that demonstrates how well PR is being implemented in the management of patients with COPD, in line with internationally recognized guidelines; and (2) identify barriers to the guideline-based implementation of PR in patients with COPD.

METHODS

To address these review questions, a systematic search for relevant peer-reviewed qualitative and quantitative studies published between 2005 and 2009 was conducted. Electronic databases (EMBASE, Ageline, Your Journals@Ovid, MEDLINE, AMED, PsycINFO, and CINAHL) were searched using combinations of the following keywords: pulmonary rehabilitation, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, guidelines, implementation, adherence, barriers, and uptake. The search identified 31 articles that addressed the specific questions of this review. A range of study methodologies was represented in the identified studies, including systematic reviews, randomized controlled trials, qualitative studies (focus groups and interviews), and reports of round-table conferences. Data addressing the review questions were extracted and synthesized into a narrative report.

RESULTS

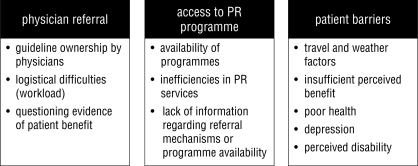

Barriers to guideline-based implementation of PR have been examined at individual stages of the patient journey. Three areas addressed in the literature are (1) physician referral, (2) access to PR programmes, and (3) patient barriers to participation (see Figure 1). In some cases, the efficacy of interventions to address these barriers has been described.

Figure 1.

Documented barriers to guideline-based implementation of pulmonary rehabilitation

Referral to PR by Primary-Care Physicians

A prospective study of practice patterns in 1,090 Canadian patients with COPD16 found that referral to PR by primary-care physicians was uncommon (only 9% of patients with moderate to severe COPD were referred). Participating physicians represented only 3% of those contacted, which indicates that bias is likely to have overestimated the proportion of referred patients. Similarly low referral incidence has been reported in the United States,17 Germany,18 and Malaysia;19 a higher referral rate of 16% was reported in a volunteer group of general practitioners in Denmark.20 In a survey of primary-care physicians and nurse practitioners in the United States, only 3% of respondents (n=284 surveys returned) expressed a belief that PR is helpful in COPD management.17 A survey of primary-care physicians in Germany found that referral to PR based on disease severity criteria did not meet national or international guidelines.18

These quantitative surveys did not examine reasons for differences between recommended and reported practices. In contrast, Smith et al. identified social factors, including “a need for a greater sense of ownership of the content,”21(p.124) as a major barrier for medical consultants in the implementation of guidelines for inpatient management of patients with COPD in Adelaide, Australia (Adelaide Collaboration on Chronic Respiratory Disease, or ACCORD, guidelines, a local adaptation of national and international guidelines). Non-consultant medical officers, nursing staff, and allied health staff cited logistical difficulties (workloads, limited time), as well as a need for clear evidence that patient outcomes would be enhanced by guideline implementation. Initiatives and publications that attempt to extract key messages from guidelines about PR to promote to primary-care practitioners22,23 have been reported but not evaluated. A written resource providing COPD patients with information about evidence-based management for their condition did not lead more patients to discuss COPD management with their doctors, as had been anticipated.24 However, participation by general practitioners in an educational programme improved the incidence of referral to PR for COPD patients, evaluated by audits of patient records (>2,300 records pre and post) before and 12 months after the programme.20

Availability of and Access to PR Programmes

One possible cause of low referral rates is the belief that recommendations with respect to PR are “beyond the reach of many patients and health care systems.”25(p.278) For example, in the Asia-Pacific region, an expert task force recommended that simplified PR programmes be established in areas where comprehensive programmes are unavailable.26 In Canada, Brooks et al.13 distributed a survey about PR programmes to all hospitals with >250 beds (n=244); of the 149 surveys returned, 89 reported PR programmes, and 36 facilities (60%) described waiting lists for intervention (with 14±12 patients waiting for 11±9 weeks). The authors estimated that the capacity of these programmes would provide a PR service to only 1.2% of Canadians with COPD. It may be that medical practitioners are not referring patients because they know either that PR programmes are not available locally or that existing programmes are full to capacity. However, the strong evidence base for PR as a cost-effective intervention is an incentive to insurers and governments. A recent round-table discussion of PR experts noted that beginning in January 2010, PR will be an approved medical benefit under both Medicare and Medicaid programmes in the United States.27

An unpublished survey of Australian PR providers28 reported that an average of 8.4 patients participated in PR each time the programme was offered. In most centres (73%), programmes were not run continuously; an average of five programmes were offered per year, so that patients were required to wait to join the next available programme. These figures suggest inefficiencies in system-wide organization of processes such as intake (e.g., non-continuous programmes) that could be addressed in order to improve access to PR services.29 Almost all (96%) of the Australian PR providers surveyed felt that there were patients who could benefit from PR who were not accessing it. In this scenario, eligibility criteria (related to programme funding) may prevent primary-care physicians from referring patients to PR programmes. Alternatively, it may be that physicians lack up-to-date, reliable information about the availability of, eligibility criteria for, and referral mechanisms to high-quality local PR programmes. Possible models of care to promote PR referral and uptake include facilitated coordinated care (assistance with identifying and accessing required health care services)30 or a specialized referral service. While one approach to coordinated care failed to reduce hospitalizations for patients with COPD, some quality-of-life measures did improve following this intervention.31

Patient Barriers to Participation

For patients who are both referred to PR and access a PR programme, there are still many reasons that may impede successful completion of the programme. Reported completion rates vary; recent studies have described completion rates ranging from 69%32 to 77%.33 Patient barriers to participation in PR, as determined from semi-structured interviews, include unwillingness to travel, insufficient perceived benefit from the intervention,34 lack of social support at home, overcoming the effort of living with COPD,35 and health and weather factors.36

Depression has been identified as a risk factor for dropout from PR.32 Symptoms of depression and anxiety were also identified in the US National Emphysema Treatment Trial37 as predictors of non-adherence to PR, along with distance to travel (>36 miles), lower education levels, and worse baseline FEV1 (<20% predicted). Fischer et al.38 reported that patients' time constraints or dissatisfaction with organization of care were the main reasons for lack of programme uptake or early dropout. Female patients, those living alone, and current smokers were more likely to cancel appointments. Greater belief in the effectiveness of PR and higher fat-free mass also predicted attendance. A UK observational study of 239 patients found that being a current smoker, experiencing greater breathlessness, more frequent hospital admissions, and longer patient travel time were independently associated with worse attendance at PR sessions.39

Implementing PR: In the “Too Hard” Basket?

Frameworks for chronic disease management, such as the chronic care model (CCM), are whole-system approaches that aim to improve processes and outcomes while making the best use of limited health care resources.40 Components of the CCM include self-management support (helping patients acquire skills to manage their own chronic condition); design of delivery systems (health practice organizational changes to support and plan for chronic disease care); decision support (accessible evidence-based support for clinical decisions); and clinical information systems (information technology supporting all model components).41 These components are now being included in many national health strategies. However, industry and health policy appear to be outpacing research in this area in the urgency to address the growing costs of managing chronic disease. Based on current research, chronic care programmes for patients with COPD appear to be less effective than programmes for patients with other conditions (e.g., depression, diabetes)42 and require at least two43 or three40 components of the CCM to demonstrate lower relative risks for hospitalization.

In view of the apparent lack of implementation of PR, chronic disease self-management (CDSM) approaches to improve quality of life and reduce health care utilization in COPD are being examined.44,40 A systematic review of a variety of CDSM programmes in patients with COPD demonstrated a reduction in the probability of at least one hospital admission among patients receiving self-management education relative to those receiving “usual care” (OR=0.64; 95% CI: 0.47–0.89).45 A randomized controlled trial comparing PR with a CDSM programme for individuals with COPD based on the Stanford model is currently being conducted.44 Clearly, building patients' capacity to self-manage their conditions is a vital component of care in patients with COPD, and this is generally incorporated within PR. However, there is a need to investigate and address the challenge of implementing PR rather than opting for substitutes to this already proven cost-effective intervention.

Ways Forward: Examine the Whole Patient Journey

The complexity of gaps between evidence, policy, and practice in PR needs to be addressed. This review has demonstrated that current processes are inadequate to implement PR for most patients who would benefit from it (see Figure 2). Thus, it seems essential to consider the relative importance of identified barriers to the uptake of and adherence to PR, and how they influence each other. For example, do physicians in Canada not refer to PR because they recognize that there are too few programmes and that existing programmes have long waiting lists? A focus-group study of general practitioners and practice nurses in the United Kingdom reported that inadequate local service provision, a difficult referral process, and confusion about which health practitioner should refer to PR were key barriers to referral.46 The area that has been more comprehensively studied—individual patient barriers to completion—is the area that appears to contribute least to overall low participation rates. Reasons for lack of referral and lack of infrastructure for provision of PR have been less well documented, and it is here that the bulk of the problem appears to lie.

Figure 2.

Relative influence of barriers to participation in pulmonary rehabilitation (PR)

While single-stakeholder approaches contribute to the body of evidence, a coordinated multilevel approach to intervention will be required to change practice significantly for the better. The necessary precursor to such an approach is a holistic evaluation of the COPD patient's journey, from diagnosis forward, to strategically examine the pathway to and through PR. Information on barriers to and enablers of guideline implementation need to be considered for all stakeholders, including referring medical practitioners, PR providers, and consumers, at all time points in the journey. The relative influences of and relationships among environmental, organizational, and individual barriers to guideline implementation need to be examined in this whole-system approach.

CONCLUSION

Integration of PR in comprehensive care of patients with COPD is essential to optimize patient health outcomes and to streamline service-delivery costs.26,28 While the stated target users of most COPD guidelines are clinicians, implementation requires involvement of policy makers, funding bodies, organizational systems, and communications and referral networks, as well as efforts to increase consumer awareness. While individual clinicians are encouraged to make clinical decisions based on guidelines, without whole-system support these decisions are likely to be difficult to sustain.

The task of implementing evidence-based policy with respect to PR will be specific to local context and to national health care systems. Once a clear picture of the system- and environment-wide barriers to patient participation in PR is obtained, policy intervention research can proceed. High-quality guidelines that support PR should form the basis of engagement between policy-intervention research, health policy makers, funding bodies, clinicians, and consumers.

Key Messages

What Is Already Known on This Topic

PR is a cost-effective intervention for patients with COPD and is recommended by international guidelines for the management of these patients. However, participation of suitable patients in PR is low.

What This Study Adds

Low rates of referral by primary-care physicians and difficulty in accessing suitable programmes are major barriers to the implementation of PR. Individual patient barriers to completion of PR programmes are well documented, but these factors contribute less to overall low participation rates in patients with COPD. An examination of the patient journey to and through PR is needed to investigate the relative influences of environment, organization, and individual factors. Such an examination will better inform policy, funding, service delivery, and other interventions to improve participation in PR.

Johnston K, Grimmer-Somers K. Pulmonary rehabilitation: overwhelming evidence but lost in translation? Physiother Can. 2010;62:368–373

References

- 1.Lacasse Y, Goldstein R, Lasserson TJ, Martin S. Pulmonary rehabilitation for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Db Syst Rev. 2006;4 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003793.pub2. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003793.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ries AL, Bauldoff GS, Carlin BD, Casaburi R, Emery CF, Mahler DA, et al. Pulmonary rehabilitation: joint ACCP/AACVPR evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2007;131(5 Suppl):4S–42S. doi: 10.1378/chest.06-2418. doi: 10.1378/chest.06-2418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coventry PA, Hind D. Comprehensive pulmonary rehabilitation for anxiety and depression in adults with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Psychosom Res. 2007;63:551–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2007.08.002. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2007.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Griffiths TL, Phillips CJ, Davies S. Cost effectiveness of an outpatient pulmonary rehabilitation program. Thorax. 2001;56:779–84. doi: 10.1136/thorax.56.10.779. doi: 10.1136/thorax.56.10.779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cecins N, Geelhoed E, Jenkins SC. Reduction in hospitalization following pulmonary rehabilitation in patients with COPD. Aust Health Rev. 2008;32:415–22. doi: 10.1071/ah080415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Puhan M, Scharplatz M, Troosters T, Walters EH, Steurer J. Pulmonary rehabilitation following exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Db Syst Rev. 2009;1 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005305.pub2. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005305.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) Global strategy for the diagnosis, management and prevention of COPD: updated 2008. Washington: Medical Communications Resources Inc.; 2008. [cited 2009 Aug 4]. Available from: http://www.goldcopd.org/Guidelineitem.asp?l1=2&l2=1&intId=2003. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abramson M, Brown J, Crockett AJ, Frith PA, Glasgow N, Jenkins S, et al. The COPD-X plan: Australian and New Zealand guidelines for the management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Lutwyche, QLD: Australian Lung Foundation; 2010. [cited 2010 Jul 19]. Available from: http://www.copdx.org.au/home. [Google Scholar]

- 9.O'Donnell D, Aaron S, Bourbeau J, Hernandez P, Marciniuk P, Balter M, et al. The Canadian Thoracic Society recommendations for management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (2007 update) Can Respir J. 2007;14(Suppl B):5B–32B. doi: 10.1155/2007/830570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.National Collaborating Centre for Chronic Conditions. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: national clinical guideline on management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in adults in primary and secondary care. Thorax. 2004;59(Suppl 1):1–232. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Holland AE, Hill CJ, Conron M, Munro P, McDonald CF. Short term improvement in exercise capacity and symptoms following exercise training in interstitial lung disease. Thorax. 2008;63:549–54. doi: 10.1136/thx.2007.088070. doi: 10.1136/thx.2007.088070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ferreira A, Garvey C, Connors GL, Hilling L, Rigler J, Farrell S, et al. Pulmonary rehabilitation in interstitial lung disease: benefits and predictors of response. Chest. 2009;135:442–7. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-1458. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-1458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brooks D, Sottana R, Bell B, Hanna M, Laframboise L, Selvanayagarajah S, et al. Characterization of pulmonary rehabilitation programs in Canada in 2005. Can Respir J. 2007;14(2):87–92. doi: 10.1155/2007/951498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Australian Lung Foundation. Pulmonary rehabilitation [Internet] Brisbane: The Foundation; c2009. [updated 2009 Aug 31; cited 2010 Jul 19]. Available from: http://www.lungfoundation.com.au/content/view/197/197/ [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yohannes AM, Connolly MJ. Pulmonary rehabilitation programmes in the UK: a national representative survey. Clin Rehabil. 2004;18:444–9. doi: 10.1191/0269215504cr736oa. doi: 10.1191/0269215504cr736oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bourbeau J, Sebaldt RJ, Bouchard J, Day A, Bouchard J, Kaplan A, et al. Practice patterns in the management of COPD in primary practice: the CAGE study. Can Respir J. 2008;15(1):13–9. doi: 10.1155/2008/173904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yawn BP, Wollan PC. Knowledge and attitudes of family physicians coming to COPD continuing medical education. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2008;3:311–7. doi: 10.2147/copd.s2486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Glaab T, Banik N, Singer C, Wencker M. Outpatient management of COPD in Germany according to national or international guidelines. Dtsch Med Wochensch. 2006;131:1203–8. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-941752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Azarisman SMS, Hadzri HM, Fauzi RA, Fauzi AM, Faizal MPA, Roslina MA, et al. Compliance to national guidelines on the management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in Malaysia: a single centre experience. Singapore Med J. 2008;49:886–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lange P, Rasmussen F, Borgeskov H, Dollerup J, Jensen MS, Roslind K, et al. The quality of COPD care in general practice in Denmark: the KVASIMODO study. Prim Care Respir J. 2007;16(3):174–81. doi: 10.3132/pcrj.2007.00030. [KVASIMODO Study Group]. doi: 10.3132/pcrj.2007.00030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smith B, Dalziel K, McElroy HJ, Ruffin RE, Frith PA, McCaul KA, et al. Barriers to success for an evidence-based guideline for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Chron Respir Dis. 2005;2(3):121–31. doi: 10.1191/1479972305cd075oa. doi: 10.1191/1479972305cd075oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fromer L, Cooper CB. A review of the GOLD guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of patients with COPD. Int J Clin Pract. 2008;62:1219–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2008.01807.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2008.01807.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.ZuWallack R, Hedges H. Primary care of the patient with COPD—part 3: pulmonary rehabilitation and comprehensive care for the patient with COPD. Am J Med. 2008;121(7 Suppl):S25–32. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harris M, Smith BJ, Veale A, Esterman A, Frith P, Selim P. Providing patients with reviews of evidence about COPD treatments: a controlled trial of outcome. Chron Respir Dis. 2006;3(3):133–40. doi: 10.1191/1479972306cd112oa. doi: 10.1191/1479972306cd112oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pierson DJ. Clinical practice guidelines for COPD: a review and comparison of current resources. Respir Care. 2006;51:277–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Asia Pacific COPD Roundtable Group. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease strategy for the diagnosis, management and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: an Asia-Pacific perspective. Respirology. 2005;10(1):9–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2005.00692.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2005.00692.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nici L, Raskin J, Rochester CL, Bourbeau JC, Carlin B, Casaburi R, et al. Pulmonary rehabilitation: what we know and what we need to know. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev. 2009;29(3):141–51. doi: 10.1097/HCR.0b013e3181a85cda. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Australian Lung Foundation. Market research report: pulmonary rehabilitation survey [Internet] Neutral Bay, NSW: Stollznow Research; 2007. [cited 2009 Aug 4]. Available from: http://www.lungfoundation.com.au/images/stories/docs/ALF_PulmonRehab_Report_FINAL_200707.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Spruit MA, Vanderhoven-Augustin I, Janssen PP, Wouters EFM. Integration of pulmonary rehabilitation in COPD. Lancet. 2008;371:12–3. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60048-3. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60048-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bird SR, Kurowski W, Dickman GK, Kronborg I. Integrated care facilitation for older patients with complex health care needs reduces hospital demand. Aust Health Rev. 2007;31:451–61. doi: 10.1071/ah070451. doi: 10.1071/AH070451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Smith BJ, McElroy HJ, Ruffin RE, Frith PA, Heard AR, Battersby MW, et al. The effectiveness of coordinated care for people with chronic respiratory disease. Med J Aust. 2002;177:481–5. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2003.tb05054.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Garrod R, Marshall J, Barley E, Jones PW. Predictors of success and failure in pulmonary rehabilitation. Eur Respir J. 2006;27:788–94. doi: 10.1183/09031936.06.00130605. doi: 10.1183/09031936.06.00130605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fischer MJ, Scharloo M, Abbink JJ, Thijs-Van Nies A, Rudolphus A, Snoei L, et al. Participation and drop out in pulmonary rehabilitation: a qualitative analysis of the patient's perspective. Clin Rehabil. 2007;21:212–21. doi: 10.1177/0269215506070783. doi: 10.1177/0269215506070783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Taylor R, Dawson S, Roberts N, Sridhar M, Partridge MR. Why do patients decline to take part in a research project involving pulmonary rehabilitation? Respir Med. 2007;101:1942–6. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2007.04.012. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2007.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Arnold E, Bruton A, Ellis-Hill C. Adherence to pulmonary rehabilitation: a qualitative study. Respir Med. 2006;100:1716–23. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2006.02.007. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2006.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.O'Shea SD, Taylor NF, Paratz JD. But watch out for the weather: factors affecting adherence to progressive resistance exercise for persons with COPD. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev. 2007;27(3):166–74. doi: 10.1097/01.HCR.0000270686.78763.c8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fan VS, Giardino ND, Blough DK, Kaplan RM, Ramsey SD, Fishman AP, et al. Costs of pulmonary rehabilitation and predictors of adherence in the National Emphysema Treatment Trial. COPD. 2008;5(2):105–16. doi: 10.1080/15412550801941190. doi: 10.1080/15412550801941190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer MJ, Scharloo M, Abbink JJ, van't Hul AJ, van Ranst D, Rudolphus A, et al. Drop-out and attendance in pulmonary rehabilitation: the role of clinical and psychosocial variables. Respir Med. 2009;103:1564–71. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2008.11.020. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2008.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sabit R, Griffiths TL, Evans W, Bolton CE, Shale DJ, Lewis KE. Predictors of poor attendance at an outpatient pulmonary rehabilitation programme. Respir Med. 2008;102:819–24. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2008.01.019. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2008.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Steuten LM, Lemmens KM, Nieboer AP, Vrijhoef HJ. Identifying potentially cost effective chronic care programs for people with COPD. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2009;4(1):87–100. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bodenheimer T, Wagner EH, Grumbach K. Improving primary care for patients with chronic illness. J Am Med Assoc. 2002;288:1775–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.14.1775. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.14.1775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ofman JJ, Badamgarav E, Henning JM, Knight K, Gano AD, Jr, Levan RK. Does disease management improve clinical and economic outcomes in patients with chronic diseases? a systematic review. Am J Med. 2004;117:182–92. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2004.03.018. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2004.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Adams SG, Smith PK, Allan PF, Anzueto A, Pugh JA, Cornell JE. Systematic review of the chronic care model in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease prevention and management. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:551–61. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.6.551. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.6.551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chang AT, Haines T, Jackson C, Yang I, Nitz J, Choy NL, et al. Rationale and design of the PRSM study: pulmonary rehabilitation or self management for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), what is the best approach? Contemp Clin Trials. 2008;29:796–800. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2008.04.004. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2008.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Effing T, Monninkhof EEM, van der Valk PP, Zielhuis GGA, Walters EH, van der Palen JJ, et al. Self-management education for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Db Syst Rev. 2007;4 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002990.pub2. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002990.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Harris D, Hayter M, Allender S. Improving the uptake of pulmonary rehabilitation in patients with COPD: qualitative study of experiences and attitude. Br J Gen Pract. 2008;58:703–10. doi: 10.3399/bjgp08X342363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]