Abstract

Objective

Insomnia is a significant public health problem, particularly among older adults. We examined social support as a potential protective factor for sleep among older adults (60 years and older) with insomnia (n = 79) and age- and sex-matched controls without insomnia (n = 40).

Methods

Perceived social support, sleep quality, daytime sleepiness, and napping behavior were assessed via questionnaires or daily diaries. In addition, wrist actigraphy provided a behavioral measure of sleep continuity parameters, including sleep latency (SL), wakefulness after sleep onset (WASO), and total sleep time (TST). Analysis of covariance for continuous outcomes or ordinal logistic regression for categorical outcomes were used to examine the relationship between social support and sleep-wake characteristics and the degree to which observed relationships differed among older adults with insomnia versus non-insomnia controls. Covariates included demographic characteristics, depressive symptoms, and the number of medical comorbidities.

Results

The insomnia group had poorer subjective sleep quality, longer diary-assessed SL and shorter TST as compared to the control group. Higher social support was associated with lesser actigraphy-assessed WASO in both individuals with insomnia and controls. There was a significant patient group by social support interaction for diary-assessed SL, such that higher levels of social support were most associated with shorter sleep latencies in those with insomnia. There were no significant main effects of social support or social support by patient group interactions for subjective sleep quality, daytime sleepiness, napping behavior, or TST (diary or actigraphy-assessed).

Conclusion

These findings extend the literature documenting the health benefits of social support, and suggest that social support may similarly influence sleep in individuals with insomnia as well as non-insomnia controls.

Keywords: Insomnia, Older adults, Sleep, Social Support

Introduction

Insomnia is a highly prevalent and debilitating sleep disorder that disproportionately affects older adults (1, 2). However, some studies have suggested that age per se, is not a risk factor for insomnia but rather, age-related declines in mental and physical health are responsible for the excess risk (3). Ohayon and colleagues (3) have further shown that social factors, including social isolation or dissatisfaction with social activities may further contribute to age-related increases in insomnia risk. Conversely, high levels of social support may be an important, though under-investigated, protective factor associated with healthier sleep, particularly among vulnerable populations, such as older adults. Indeed, evidence from the broader social support literature documents particularly robust effects of social support on health outcomes in older populations (4, 5).

There are a number of reasons to predict that social support should be beneficial for sleep. First, social support could influence sleep by providing a sense of belonging and connectedness, inducing positive mood states, and promoting positive health behaviors, including maintaining healthy sleep habits (6). Moreover, perceiving that others “are there” and “will be there” for the individual protects against social isolation and loneliness, factors that have previously been associated with increased risk of sleep disturbance (7-9). In addition, social supports may operate as social zeitgebers (i.e., “time-givers”) which facilitate entrainment of circadian rhythms (10, 11), thereby helping to maintain a more consistent and consolidated sleep-wake schedule. For example, regularly meeting a friend for breakfast may benefit sleep not only by promoting a sense of belonging and enhancing well-being and deterring against negative emotions associated with sleep disturbance, but also by reinforcing a consistent sleep and wake routine. Social support could also influence sleep by attenuating the effects of psychological stress on sleep (12-14). Finally, there may be tangible aspects of social support that may benefit sleep, such as increasing access to material aid or resources, including information about healthy sleep habits. Thus, there are several plausible pathways that may link different types of social support with sleep, including: protecting against social isolation, attenuating stress responses, providing a sense of belonging and emotional support, encouraging healthy sleep behaviors, and entraining circadian rhythms.

Indeed, a number of studies have shown that aspects of the social environment are related to sleep disturbances in older adults (7, 15-18). However, the bulk of the extant literature has focused on the presence or absence of relationships (e.g., married versus unmarried) rather than the social supportive functions relationships provide. Moreover, among the studies that have examined social support per se, most have relied on single-or few-item measures of social support (e.g., “do you have a confidante?”), which have questionable reliability and validity, and only capture a single dimension of social support (e.g., emotional). Utilizing a more comprehensive and validated assessment of social support may provide a more sensitive examination of the links between social support and sleep.

With few exceptions (7, 19) the extant literature has focused exclusively on the relationship between social support and self-reported sleep disturbances. These findings may reflect a more general negative affect bias, leading to negative perceptions of sleep and of social support. Thus, a more comprehensive test of the association between social support and sleep would be to include both behavioral and self-report measures of sleep. It is also important to examine whether observed associations between social support and sleep persist after statistical adjustment for other factors known to covary with sleep and social factors, including mental and physical health comorbidities. Indeed, given evidence that sleep disturbances may be an important predictor of functioning in older adults, including engagement in social activities (20), it is also plausible that the reverse pathway is true; sleep disturbances may lead to more negative perceptions of the social environment. Although cross-sectional studies cannot determine causality nor the directionality of the relationship, statistical control for variables that may account for the relationship affords the opportunity to examine the degree to which social support and sleep are associated, independent of other known risk factors. Finally, epidemiological studies which have included questions on sleep typically assess a limited number of sleep complaints or symptoms, but do not specifically examine whether results are similarly evidenced in individuals with a clinically significant sleep disorder. Given that insomnia is the most common sleep disorder, particularly among older adults, it is critical to examine whether the association between social support and sleep still holds for individuals with insomnia, or whether the association is evident only in non-sleep-disordered populations. That is, does the sleep disorder itself mask the association between social support and sleep? Previous research on the role of stress in the pathophysiology of insomnia suggests that individuals with insomnia are more vulnerable to stress-related sleep disturbances than normal sleepers (14); findings which may be attributable, at least in part, to a relative deficiency or inability to effectively utilize social support resources.

The present study examined the association between a well-validated and comprehensive measure of social support and sleep as measured by both self-report and by actigraphy, which provides a behavioral measure of rest-activity patterns. Participants in the study included individuals with well-characterized histories of insomnia and non-insomnia controls who were comparable in terms of age and sex. First, we examined whether perceptions of social support differed between individuals with insomnia and controls. Given the high comorbidity between insomnia and mood disorders, most notably, depression (2, 21), and that perceptions of social support may reflect, at least in part, a general affective bias (22), we predicted that individuals with insomnia would perceive lower levels of social support than controls. Second, we examined whether higher levels of social support are uniquely related to sleep outcomes, or whether social support is merely a proxy for depressive symptoms, general health, or demographic characteristics (including the presence or absence of a spouse) that are related to sleep. We hypothesized that higher levels of social support would be independently associated with better sleep, even after statistically controlling for relevant covariates. Finally, we examined whether the association between social support and sleep differed among individuals with insomnia and good sleeper controls. We predicted that the association between social support and sleep would be stronger among non-insomnia controls than among individuals with insomnia. That is, consistent with prior research showing greater susceptibility to stress-related sleep disturbances among individuals with insomnia, we predicted that individuals with insomnia would also fail to reap the benefits of social support as compared to controls.

Methods

These data were collected as part of an ongoing study of older adults with chronic insomnia (symptoms present for at least 6 months) and their response to a Brief Behavioral Treatment for Insomnia (BBTI). The BBTI study is part of a broader program project examining behavioral intervention strategies for sleep problems of older adults (AG 20677, T.H. Monk, Principal Investigator). Data for the current analyses were drawn from the pre-treatment baseline assessment in individuals with chronic insomnia and controls. Participants underwent an initial telephone screening and an in-person diagnostic evaluation conducted by study clinicians for the assessment of psychiatric or medical conditions. Within one month of the clinical evaluation participants completed baseline questionnaire data and two weeks of sleep diaries in conjunction with actigraphy in their home environments. The University of Pittsburgh Biomedical Institutional Review Board approved this study. All participants provided written informed consent.

Participants

All participants (N= 119) were at least 60 years of age, and were recruited from a primary care clinic or community advertisements. Insomnia participants were required to meet the general criteria for insomnia disorder in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition (DSM-IV) (23) and the International Classification of Sleep Disorders, 2nd Edition (24). Specifically, criteria included: presence of a sleep complaint lasting for at least one month (median duration of symptoms was 340 weeks, indicating chronic insomnia); adequate opportunity and circumstances for sleep; and evidence of significant distress or daytime impairment. To optimize the clinical relevance and generalizability of the study, we did not apply the exclusion criteria of DSM-IV for medical or psychiatric disorders. As a result, most of our participants would be considered to have comorbid insomnia (i.e., presence of another stable medical or psychiatric condition in addition to insomnia). The following exclusion criteria were applied: presence of dementia (identified by history or a score <25) on the Folstein Mini Mental Status Exam (25) or delirium; previously undiagnosed and untreated depressive, anxiety, psychotic, or substance use disorders (those with stably-treated depressive and anxiety disorders were not excluded); untreated obstructive sleep apnea syndrome (apnea hypopnea index (AHI) > 20), restless legs syndrome or other sleep disorders (those with stably-treated sleep disorders were not excluded); hospitalization within the past two weeks; ongoing chemotherapy or other cancer treatment; and terminal illness with life expectancy less than 6 months.

The present sample included 79 insomnia patients (68% female) with social support, demographic, and sleep data. We recruited control participants in a 2:1 ratio from the same sources, and applied the same inclusion and exclusion criteria, with the exception of the presence of insomnia. Control participants were carefully screened for the absence of clinically significant sleep complaints; however, they did not undergo polysomnographic screening for apnea or restless legs. The present sample consists of 40 controls (65% female) with complete data.

Measures

Social support, demographic, and clinical characteristics of the sample were collected via self-report at the baseline assessment. The major outcome measures for this study (described below) were subjective sleep quality from the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI); (26), subjective daytime sleepiness from the Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS) (27), quantitative sleep parameters including sleep latency (SL), wakefulness after sleep onset (WASO), and total sleep time (TST) as assessed from sleep diaries and actigraphy, and napping behavior (number of naps per week, assessed via diary). These specific outcomes were chosen as they are important markers of functioning in older populations (e.g., daytime sleepiness; TST; napping) and/ or correspond with clinically relevant criteria in the diagnosis of insomnia (28).

Social Support

The 16-item version of the Interpersonal Support Evaluation List (ISEL); (29) was used to provide a comprehensive measure of perceived social support. Specifically, the ISEL measures the perceived availability of the following kinds of support: emotional (someone with whom one can confide in), belonging (people with whom one can do things with), self-esteem (positive social comparison), and tangible (provision of material aid, e.g. someone to provide transportation). The ISEL yields a total score as well as scores for each subscale. Previous research documents the reliability and validity of the ISEL total score and the individual subscale scores (29). For the current analyses, we used the total ISEL score, as the total score yielded adequate internal reliability (α = .85); whereas 2 out of the 4 individual subscales (self-esteem and tangible) had inadequate reliabilities (α's < .61).

Covariates

Marital status was assessed via self-report and was dichotomized as currently married (1) or not married (0). Not married included subjects who were divorced or widowed. The majority of the sample was married (62%) Age, marital status and sex were included as covariates, because they have shown consistent associations with sleep disturbances (1, 21).

Depressive symptoms were assessed with the 17-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HRSD) (30). The HRSD is a clinician-administered interview scale that assesses the presence and severity of 17 symptoms of depression experienced in the past week using a varied response format ranging from 0-2 to 0-4 (with higher scores indicating greater depression severity), and exhibits well-documented reliability and validity (31). Given that the HRSD includes 3 items which pertain to sleep disturbance, we removed these 3 items from all subsequent analyses.

Medical comorbidities were evaluated with the Comorbidity Questionnaire developed at the Center for Research on Chronic Disorders at the University of Pittsburgh School of Nursing. This measure is adapted from the Charlson Comorbidity Index (32), but includes a wider range of conditions, which we have grouped into 17 categories.

Sleep Outcomes

The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI); (26) was used as a measure of global sleep quality. The PSQI is a widely-used, well-validated, self-report scale, spanning 7 categories that assess sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep duration, habitual sleep efficiency, sleep disturbances, use of sleeping medications, and daytime dysfunction. Participants are asked to respond to questions about their sleep in the past month. A global sleep quality score was computed by summing the scores from the seven sleep categories, with a total possible range from 0 (good sleep quality) to 21 (poor sleep quality).

The Pittsburgh Sleep Diary (PghSD) (33) is a prospective self-report measure of daytime activities, sleep behaviors, and sleep parameters, including bed time and rise time, sleep latency, wakefulness during sleep, sleep quality, and number of naps per day. Previous research has demonstrated that the PghSD is sensitive to differences between sleep disorder patients and good sleeper controls (33), and to behavioral treatment effects in insomnia patients (34). The PghSD was collected for two weeks (mean = 14 days, SD = 1.2) at baseline in both insomnia and control participants. For the present study, outcomes from the PghSD included SL, WASO, and TST (all expressed in minutes) and number of naps per week (defined categorically as < 1 nap, 1-3 naps, > 3 naps/ week).

Wrist actigraphy was measured with the Minimitter Actiwatch-64© device (Respironics, Inc., Murrysville, PA), which was worn concurrently with the collection of sleep diary data (on average 14 days). Actigraphs are wrist-watch-sized, motion-sensitive monitors worn on the participant's nondominant arm that can be used to provide a behavioral measure of sleep-wake patterns. Previous research has documented the reliability and validity of actigraphy assessed measures of sleep in older adults with and without insomnia (35, 36). Actigraphy data were collected in one-minute epochs and analyzed with the validated Actiware Version 5.04 software program. Sleep diary data for bed time and rise time were entered for calculation of sleep-wake variables. Actigraphy outcome variables included SL, WASO, and TST (all expressed in minutes). We used definitions provided by the Actiware software for these variables, which rely on values for bed time and rise time from the sleep diary.

Analyses

Prior to statistical analyses, we examined the data for normality and used transformations where necessary to normalize distributions. T-tests and chi-squares were used to examine group differences in social support, sleep outcomes, and covariates. The primary analytic strategy involved analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) to examine the main effect of social support and the interaction between social support and patient status (insomnia versus control) on each sleep outcome, after adjusting for age, gender, marital status, depressive symptoms, number of medical conditions, and the main effect of patient status. Given that naps per week were analyzed as a categorical outcome due to the distribution of the variable (< 1 nap/ week, 1-3 naps/ week, > 3 naps/ week), for this outcome only, analyses were conducted using ordinal logistic regression with the same covariates as in ANCOVA.

Results

Sample Characteristics (Table 1)

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics good sleeper controls and for insomnia patients.

| Controls (n=40) | Insomnia (n=79) | |

|---|---|---|

| % Female (n) | 65.0 (26) | 68.4 (54) |

| % Married (n) | 70.0 (28) | 58.2 (46) |

| Number of chronic health conditions† | 4.8 (2.5) | 5.6 (2.7) |

| Hamilton Depression Rating Scale ⌠†** | 1.4 (1.6) | 3.6 (2.4) |

| Social Support | 37.5 (7.4) | 36.9 (6.5) |

| Clinical Ratings | ||

| PSQI†** | 2.4 (1.7) | 10.4 (3.0) |

| ESS† | 6.0 (3.1) | 6.7 (3.8) |

| Sleep Diary Measures | ||

| Sleep Latency†** | 12.7 (11.0) | 36.4 (28.1) |

| WASO†** | 12.5 (13.5) | 51.7 (33.4) |

| TST** | 443.9 (45.6) | 400.7 (66.3) |

| Naps | % (n) | % (n) |

| < 1 nap/ week | 45 (18) | 37 (29) |

| 1-3 naps/ week | 33 (13) | 33 (26) |

| > 3 naps/ week | 7.6 (9) | 19.5 (23) |

| Actigraphy | ||

| Sleep Latency† | 12.9 (9.2) | 16.5 (12.4) |

| WASO† | 47.7 (22.0) | 54.8 (24.3) |

| TST†* | 399.9 (36.1) | 379.5 (49.0) |

Note. Depressive symptoms after removing sleep items; PSQI = Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index; ESS = Epworth Sleepiness Scale; WASO = Wakefulness After Sleep Onset; TST = total sleep time.

Transformation used in analyses. Units for sleep latency, WASO, and TST are represented in minutes.

p < .01;

p < .05.

The groups were comparable in terms of age, sex, marital status, and education. Insomnia patients reported more depressive symptoms, poorer sleep quality (PSQI), longer diary-assessed SL and WASO, and shorter actigraphy and diary-assessed TST. The groups did not differ in level of number of comorbid medical conditions, perceived social support, daytime sleepiness (ESS), diary-assessed naps, or actigraphy-assessed SL or WASO.

Patient Status, Social Support and Sleep

ANCOVA results depicting the relationship between the main effects of patient status, social support and social support*patient status interactions are reported in Table 2. After adjustment for covariates, there was a main effect of patient status on subjective sleep quality (PSQI). However, there were no significant main effects of social support or social support* patient status interactions for PSQI or ESS.

Table 2.

Analyses of covariance examining the association between patient status, social support, and the interaction of patient status * social support on sleep.ˆ

| Patient Status | Social Support | Social Support*Patient Status | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical Ratings | |||

| PSQI† | F(1,109)=6.93, p=0.01 | F(1,109)=3.43, p=0.07 | F(1,109)=0.38, p=0.54 |

| ESS† | F(1,108)=0.01, p=0.94 | F(1,108)=2.51, p=0.12 | F(1,108)=0.00, p=0.96 |

| Sleep Diary | |||

| Sleep Latency† | F(1,108)=10.99, p=0.001 | F(1,108)=1.62, p=0.21 | F(1,108)=4.55, p=0.04 |

| WASO† | F(1,107)=0.27, p=0.61 | F(1,107)=1.16, p=0.28 | F(1,107)=1.83, p=0.18 |

| TST† | F(1, 108)= 6.00, p=0.02 | F(1, 108)= 0.00, p =0.96 | F(1, 108)= 2.74, p =0.10 |

| Number of Naps (per week) ∂ | χ2 (1) = 2.52, p = .11 | χ2 (1) = 1.45, p = .23 | χ2 (1) = 2.43, p = .12 |

| Actigraphy | |||

| Sleep Latency† | F(1,98)=1.41, p=0.24 | F(1,98)=0.74, p=0.39 | F(1,98)=0.75, p=0.39 |

| WASO† | F(1,98)=0.01, p=0.91 | F(1,98)=7.95, p=0.006 | F(1,98)=0.17, p=0.68 |

| TST† | F(1,98)=3.38, p=0.07 | F(1,98)=0.04, p=0.84 | F(1,98)=1.86, p=0.18 |

Note. Controlling for age, gender, marital status, HRSD with sleep items removed, and count of medical conditions. PSQI = Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index; ESS = Epworth Sleepiness Scale; WASO = Wakefulness After Sleep Onset; TST = total sleep time.

Transformation used in analyses.

Analyzed using ordinal logistic regression due to categorical nature of outcome variable (naps/ week).

p < .01;

p < .05.

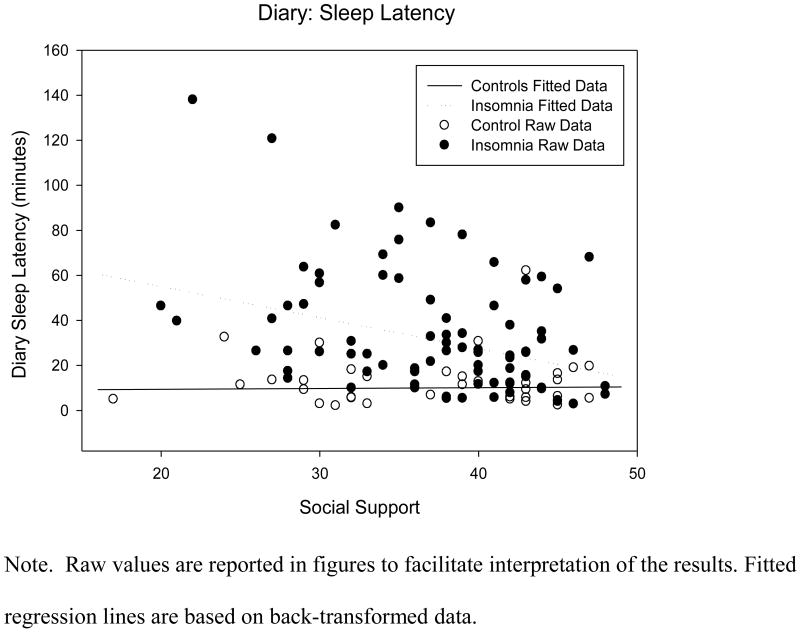

ANCOVAs for the sleep diary outcomes revealed a significant main effect of patient status on SL (F (1,108) = 10.54, p =.002) and TST (F (1, 108) = 6.00, p = .02). In addition, there was a significant interaction effect for patient status*social support on sleep latency (F (4,108) = 4.55, p = .04). As shown in the fitted regression lines depicted in Figure 1, higher social support was more strongly associated with shorter sleep latencies among the insomnia group than in the control group. The main effect of social support and the social support* patient status interaction were non-significant for diary-assessed WASO, TST, and number of naps per week.

Figure 1.

Scatterplot of raw diary-assessed sleep latency values for patients with insomnia and controls according to social support, with covariate adjustment.

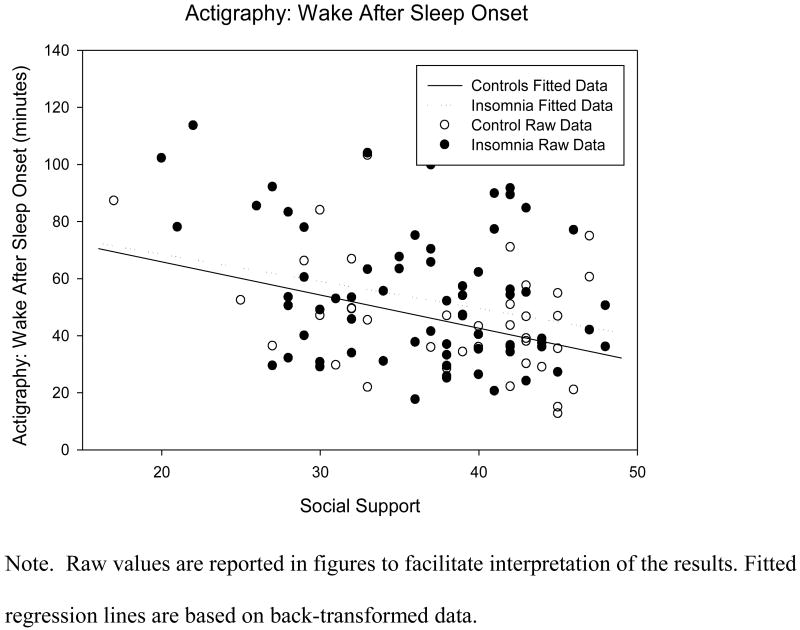

There were no significant main effects of patient status on any of the actigraphy outcomes. There was a significant main effect of social support on actigraphy-assessed WASO (F (1, 98) = 7.95, p =.006); however there was not a significant interaction term for WASO. Figure 2 shows that higher social support was associated with shorter WASO in both individuals with and without insomnia. In addition, both the main effect and interaction between social support and patient status were non-significant for sleep latency and TST.

Figure 2.

Scatterplot of raw actigraphy-assessed WASO values with fitted regression lines for patients with insomnia and controls according to social support, with covariate adjustment.

Discussion

Substantial research has investigated potential risk factors for insomnia, including age, sex, marital status, and mental and physical health comorbidities. In contrast, relatively little research has examined factors that may contribute to healthy sleep, and whether similar processes operate in individuals with versus without insomnia. The present study focused on social support as one such factor that may be associated with higher sleep quality and continuity in older adults with and without insomnia. Consistent with prior reports, older adults with insomnia had more depressive symptoms than older adults without insomnia (21), and they also differed on subjective sleep outcomes (PSQI and diary measures) more reliably than on actigraphy outcomes. Despite these differences and contrary to our expectations, individuals with insomnia and non-insomnia controls did not differ in terms of level of perceived social support. These findings argue against a general negative affect bias which might influence perceptions of health, sleep, and social support.

We found limited support for an association between social support and sleep outcomes, and these relationships differed as a function of the sleep assessment tool. Specifically, higher levels of social support were associated with shorter actigraphy-assessed WASO in both individuals with insomnia and non-insomnia controls, but there was no association between social support and actigraphy-assessed sleep latency, actigraphy or diary-assessed total sleep time, subjective sleep quality, daytime sleepiness, or napping behavior in either group. Higher social support was associated with shorter diary-assessed sleep latencies; however, this effect was primarily driven by a significant association within the insomnia group. This significant interaction may be due to the greater variability in night-to-night subjective reports of sleep latency, particularly among individuals with insomnia (37). Thus, contrary to our expectations, with the exception of diary-assessed sleep latency, we found no other significant interaction effects, suggesting that the association between social support and sleep outcomes was similar in older adults with insomnia and those without insomnia. These findings are notable in that they are the first to document that social support may be an important correlate of sleep in older adults with and without insomnia. Importantly, however, given that the findings are cross-sectional, an alternative explanation is that better sleep, particularly in the context of aging, leads to greater functioning, including higher perceptions of social support. Consistent with this notion, Dew and colleagues (20) found that disrupted sleep predicted fewer regular social activities one year later. The fact that relationships between sleep and social functioning are likely to be bidrectional in nature, rather than unidirectional (38), only further highlights the need for further longitudinal investigations that examine trajectories of social support and sleep in older adults.

Our findings should be interpreted in light of study strengths and limitations. The recruitment strategy and sample characteristics are strengths of the study, in that patients were recruited from the community and from primary care practices and inclusion criteria was broad, by design, to capture a representative sample of community-dwelling older adults with and without insomnia. Nevertheless, the sample was relatively small, which may have limited our power, particularly among the controls. While the inclusion of a behavioral measure of sleep (i.e., actigraphy) is a notable strength, actigraphy data also has limitations. Specifically, while actigraphy has demonstrated high sensitivity for detecting sleep, it tends to underestimate total wake time and sleep latency, particularly in individuals with disturbed sleep, which may have affected our ability to detect significant interactions (39). In addition, the control group did not have PSG sleep studies as part of their eligibility evaluation. Although, they were carefully screened and recruited on the basis of their reported lack of sleep disturbances, it is possible that occult sleep disorders, such as sleep-disordered breathing, could have confounded the results in the controls. Future studies examining the association between social support and polysomnographic (PSG) sleep outcomes are needed to examine relationships between social support and specific sleep stages and to address these specific limitations. Finally, although we statistically adjusted for key covariates that have consistently demonstrated relationships with sleep, including demographic characteristics, depressive symptoms, and medical comorbidities, we did not adjust for all possible confounders. Thus, we cannot rule-out the possibility that a third variable(s) could account for relationships between social support and sleep.

Nevertheless, these findings have important implications for health care providers of older adults. Specifically, given the numerous health benefits of social support and the significant health consequences of social isolation, helping seniors to strengthen their existing support networks or to build new social connections, may be an important protective factor, attenuating stress responses and facilitating healthy sleep practices. Indeed, these data in conjunction with emerging data showing that loneliness (the perceived discrepancy between actual and desired relationships) is also an independent risk factor for sleep disturbance (7, 9), further highlight the importance of the social context in influencing sleep. In summary, these findings extend the extensive and robust literature on the benefits of social support for a wide variety of mental and physical health outcomes, and suggest another way that social relationships may influence well-being and physical health.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this work was provided by the National Institutes of Health [AG 20677 to T.H.M., AG 13396 to T.H.M., AG 019362 to M.H., HL076852 / 076858 to M.H. (PMBC Core) and W.M.T (pilot funds), UL1RR024153 to D.J.B., HL082610-01 to D.J.B, and K23HL093220 to W.M.T]. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Foley DJ, Monjan AA, Brown SL, Simonsick EM, Wallace RB, Blazer DG. Sleep complaints among elderly persons: an epidemiologic study of three communities. Sleep. 1995;18:425–32. doi: 10.1093/sleep/18.6.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Morphy H, Dunn KM, Lewis M, Boardman HF, Croft PR. Epidemiology of insomnia: a longitudinal study in a UK population. Sleep. 2007;30:274–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ohayon MM, Zullery J, Guilleminault C, Smirne S, Priest RG. How age and daytime activities are related to insomnia in the general population: Consequences for older people. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49:360–366. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.49077.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Krause N. Exploring Age Differences in the Stress-Buffering Function of Social Support. Psychol Aging. 2005;20:714. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.20.4.714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Seeman T. Health promoting effects of friends and family on health outcomes in older adults. Am J Health Promot. 2000;14 doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-14.6.362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Troxel WM, Robles TF, Hall M, Buysse DJ. Marital quality and the marital bed: examining the covariation between relationship quality and sleep. Sleep Med Rev. 2007;11:389–404. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2007.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cacioppo JT, Hawkley LC, Bernston GC, Ernst JM, Gibbs AC, Stickgold R, Hobson J. Do lonely days invade the nights? Potential social modualation of sleep efficiency. Psychol Sci. 2002;13:384–387. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.00469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen Y, Kawachi I, Subramanian SV, Acevedo-Garcia D, Lee YJ. Can social factors explain sex differences in insomnia? Findings from a national survey in Taiwan. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2005;59:488–494. doi: 10.1136/jech.2004.020511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pressman SD, Cohen S, Miller GE, Barkin A, Rabin BS, Treanor JJ. Loneliness, Social Network Size, and Immune Response to Influenza Vaccination in College Freshmen. Health Psychol. 2005;24:297–306. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.24.3.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mistlberger RE, Skene DJ. Social influences on mammalian circadian rhythms: animal and human studies. Biol Rev Camb Philos Soc. 2004;79:533–556. doi: 10.1017/s1464793103006353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Monk TH, Buysse DJ, Potts JM, DeGrazia JM, Kupfer DJ. Morningness-eveningness and lifestyle regularity. Chronobiol Int. 2004;21:435–443. doi: 10.1081/cbi-120038614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Akerstedt T, Fredlund P, Gillberg M, Jansson B. Work load and work hours in relation to disturbed sleep and fatigue in a large representative sample. J Psychosom Res. 2002;53:585–588. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(02)00447-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hall M, Buysse DJ, Nofzinger EA, Reynolds CF, 3rd, Thompson W, Mazumdar S, et al. Financial strain is a significant correlate of sleep continuity disturbances in late-life. Biol Psychol. 2008;77:217–222. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2007.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morin CM, Rodrigue S, Ivers H. Role of stress, arousal, and coping skills in primary insomnia. Psychosom Med. 2003;65:259–267. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000030391.09558.a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Frisoni GB, DeLeo D, Rozzini R, Bernardini M, Buono MD. Psychic correlates of sleep symptoms in the elderly. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1992;7:891–898. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hanson BS, Ostergren PO. Different social network and social support characteristics, nervous problems and insomnia: theoretical and methodological aspects on some results from the population study ‘men born in 1914’, Malmo, Sweden. Soc Sci Med. 1987;25:849–59. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(87)90043-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Murata C, Yatsuya H, Tamakoshi K, Otsuka R, Wada K, Toyoshima H. Psychological factors and insomnia among male civil servants in Japan. Sleep Med. 2007;8:209–214. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2007.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nordin M, Knutsson A, Sundbom E. Is disturbed sleep a mediator in the association between social support and myocardial infarction? J Health Psycho. 2008;13:55–64. doi: 10.1177/1359105307084312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Friedman EM, Hayney MS, Love GD, Urry HL, Rosenkranz MA, Davidson RJ, Singer BH, Ryff CD. Social relationships, sleep quality, and interleukin-6 in aging women. Pro Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:18757–62. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509281102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dew MA, Reynolds CF, Monk TH, Buysse DJ, et al. Psychological correlates and sequelae of electroencephalographic sleep in healthy elders. J Gerontol. 1994;49:8–18. doi: 10.1093/geronj/49.1.p8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Buysse DJ, Germain A, Moul DE. Diagnosis, Epidemiology, and Consequences of Insomnia. Prim Psychiatry. 2005;12:37–44. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shaver PR, Brennan KA. Measures of depression and loneliness. In: Robinson JP, Shaver Phillip R, Wrightsman LS, editors. Measures of personality and social psychological attitudes. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1991. pp. 195–289. [Google Scholar]

- 23.American Psychiatric Association (APA) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV-TR) Fourth Edition, Text Revision. Washington, DC: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 24.American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM) The International Classification of Sleep Disorders, Second Edition (ICSD-2): Diagnostic and Coding Manual. Second Edition. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Folstein MF, Folstein SW, McHugh PR. Mini-mental state: A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: A new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989;28:193–213. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Johns MW. Sleepiness in different situations measured by the Epworth Sleepiness Scale. Sleep. 1994;17:703–10. doi: 10.1093/sleep/17.8.703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Edinger JD, Bonnet MH, Bootzin RR, Doghramji K, Dorsey CM, Espie CA, Jamieson AO, McCall WV, Morin CM, Stepanski EJ, American Academy of Sleep Medicine Work G. Derivation of research diagnostic criteria for insomnia: report of an American Academy of Sleep Medicine Work Group. Sleep. 2004;27:1567–96. doi: 10.1093/sleep/27.8.1567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cohen S, Mermelstein R, Kamarck T, Hoberman HM. Measuring the functional components of social support. In: Sarason IG, Sarason B, editors. Social support: theory, research and applications. The Hague: Martinus Nijgoff. 1985. pp. 73–94. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1960;23:56–62. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Prien RF, Carpenter LL, Kupfer DJ. The definition and operational criteria for treatment outcome of major depressive disorder. A review of the current research literature. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1991;48:796–800. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1991.01810330020003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Monk TH, Reynolds CF, 3rd, Kupfer DJ, Buysse DJ, Coble PA, Hayes AJ, Machen MA, Petrie SR, Ritenour AM. The Pittsburgh Sleep Diary. J Sleep Res. 1994;3:111–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Germain A, Moul D, Franzen PL, Miewald J, Reynolds CF, 3rd, Monk TH, Buysse DJ. Effects of a brief behavioral treatment of late-life insomnia: Preliminary findings. J Clin Sleep Med. 2006;2:403–406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Blackwell T, Redline S, Ancoli-Israel S, Schneider JL, Surovec S, Johnson NL, Cauley JA, Stone KL, Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research G. Comparison of sleep parameters from actigraphy and polysomnography in older women: the SOF study. Sleep. 2008;31:283–91. doi: 10.1093/sleep/31.2.283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lichstein KL, Stone KC, Donaldson J, Nau SD, Soeffing JP, Murray D, Lester KW, Aguillard RN. Actigraphy validation with insomnia. Sleep. 2006;29:232–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Buysse DJ, Cheng Y, Germain A, Moul D, Franzen PL, Fletcher M, Monk TH. Night-to night sleep variability in older adults with and without chronic insomnia. Sleep Med. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2009.02.010. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Reynolds CF, III, Buysse DJ, Nofzinger EA, Hall M, Dew MA, Monk TH. Age wise: Aging well by sleeping well. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49:491. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.49099.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sivertsen B, Omvik S, Havik OE, Pallesen S, Bjorvatn B, Nielsen GH, Straume S, Nordhus IH. A comparison of actigraphy and polysomnography in older adults treated for chronic primary insomnia. Sleep. 2006;29:1353–8. doi: 10.1093/sleep/29.10.1353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]