Abstract

Reversible covalent conjugation chemistries that allow site- and condition-specific coupling and uncoupling reactions are attractive components in nanotechnologies, bioconjugation methods, imaging and drug delivery systems. Here, we compare three heterobifunctional crosslinkers, containing both thiol- and amine- reactive chemistry, to form pH-labile hydrazones with hydrazide derivatives of the known and often published water-soluble polymer, poly[N-(2-hydroxypropyl methacrylamide)] (pHPMA), while subsequently coupling thiol-containing molecules to the crosslinker via maleimide addition. Two novel crosslinkers were prepared from the popular heterobifunctional crosslinking agent, succinimidyl-4-(N-maleimidomethyl) cyclohexane-1-carboxylate (SMCC), modified to contain either terminal aldehyde groups (i.e., 1-(N-3-propanal)-4-(N-maleimidomethyl) cyclohexane carboxamide, PMCA) or methylketone groups (i.e., 1-(N-3-butanone)-4-(N-maleimidomethyl) cyclohexane carboxamide, BMCA). A third crosslinking agent was the commercially available N-4-acetylphenyl maleimide (APM). PMCA and BMCA exhibited excellent reactivity towards hydrazide-derivatized pHPMA with essentially complete hydrazone conjugation to polymer reactive sites, while APM coupled only ~ 60% of available reactive sites on the polymer despite a 3-fold molar excess relative to polymer hydrazide groups. All polymer hydrazone conjugates bearing these bifunctional agents were then further reacted with thiol-modified tetramethylrhodamine dye, confirming crosslinker maleimide reactivity after initial hydrazone polymer conjugation. Incubation of dye-labeled polymer conjugates in phosphate buffered saline at 37°C showed that hydrazone coupling resulting from APM exhibited the greatest difference in stability between pH 7.4 and 5.0, with hydrolysis and dye release increased at pH 5.0 over a 24hr incubation period. Polymer conjugates bearing hydrazones formed from crosslinker BMCA exhibited intermediate stability with hydrolysis much greater at pH 5.0 at early time points, but hydrolysis at pH 7.4 was significant after 5 hrs. Hydrazones formed with the PMCA crosslinker showed no difference in release rates at pH 7.4 and 5.0.

Keywords: Hydrazone, thioether, heterobifunctional crosslinker, controlled release, HPMA, polymer drug carriers

INTRODUCTION

Recent developments in nanomaterials, biotechnology and advanced drug delivery and imaging systems have prompted innovation of new molecular building blocks and methods to attach components together to achieve advanced materials with specific functionality. For polymer-based therapeutics in particular, the benefits of conjugating drugs to water-soluble polymers are well known and include: increased circulation half-life, reduced non-specific activity, enhanced targeting ability, and physiological solubility (1). While these benefits provide strong incentives for use of polymers and new particle carriers in drug delivery, methods to chemically couple therapeutic and imaging agents to such carriers have been frequently inflexible and performance limiting. Yet, control and versatility of the chemistry used to couple molecules together is crucial to their function and purpose. Most therapeutic agents are best released from carriers at the desired physiological site of drug activity to be most effective, while retaining stability in circulation until the construct reaches its therapeutic target. Many cleverly designed coupling agents and crosslinkers have therefore been developed for stable covalent attachment under one set of conditions (i.e., normal circulation) and reversible uncoupling chemistries under other sets of conditions (2–4). That these chemistries reside in a single coupling agent that responds reliably to desired stimuli (e.g., local pH, thermal or optical gradients, enzymes, electrochemical or redox inputs) to couple and uncouple connected cargo is a challenging goal.

Strategies for site-specific nanoparticle- or polymer-based agent delivery often exploit biochemical conditions intrinsic to cell internalization and processing pathways to specifically release drug into the cellular cytoplasm (5). Polymer and nanoparticle constructs internalized into cells by endocytosis are transported to lysosomes -- membrane-encapsulated cytoplasmic organelles more acidic (pH ~ 5.0) than normal physiological conditions, and containing a host of specific enzymes (6). Therapeutic agents with activity beyond the lysosomal compartment (i.e., most drugs) must achieve lysosomal release at sufficient dosing in order to exert their desired activity. For these reasons, polymer- and nanoparticle- drug conjugation chemistry is often designed to degrade once inside the cell via cleavage by lysosome-specific enzymes, as well as by non-specific pH-dependent and organelle-specific mechanisms. The Gly-Phe-Lys-Gly (GFLG) peptide sequence has been shown to degrade specifically by the lysosome enzyme, cathepsin B, and is a distinguishing component in the poly[N-(2-hydroxypropyl) methacrylamide] (pHPMA) copolymer-doxorubicin (DOX) anticancer drug PK1, currently in clinical trials (7–11). Other degradable peptide spacers such as the dipeptides valine-citrulline, asparagines-(D) lysinie and methionine-(D) lysine have been used to produce antibody-drug conjugates where the drug is released by proteolysis of the peptide linker (12, 13). Non-specific pH-driven hydrolytic degradation and agent decoupling has been demonstrated for a variety of coupling chemistries including hydrazone, acetal, carbamate and cis-aconityl moieties (14–17).

More specifically, hydrazone bonds have been successfully used to generate a variety of pH-sensitive conjugates of the anticancer drug doxorubicin with various polymers, particles, micelles, and antibodies by reaction with hydrazide-derivatized carriers and crosslinkers with the 13-keto position of this drug (15, 16, 18–24). Hydrazone bonds are formed by condensation of hydrazides with aldehydes or ketones after elimination of the carbonyl oxygen as water, resulting in a metastable imine bond. This reaction can be performed under aqueous conditions with careful control of pH and reaction stoichiometry, but is most often performed under organic conditions with an acid catalyst such as acetic acid or trifluoroacetic acid to facilitate dehydration and formation of the hydrazone bond (19, 25, 26). While certain types of hydrazone linkages are known to be stable at pH 7.4 and degrade at low pH (i.e., < 5.0), chemistries adjacent to both hydrazide and ketone functionality greatly affect pH and hydrolytic stability. Hence, specific substituents have been used to achieve different bond cleavage rates and pH sensitivities (15, 16). This chemistry can also be tailored to present other functional groups useful for other conjugation strategies.

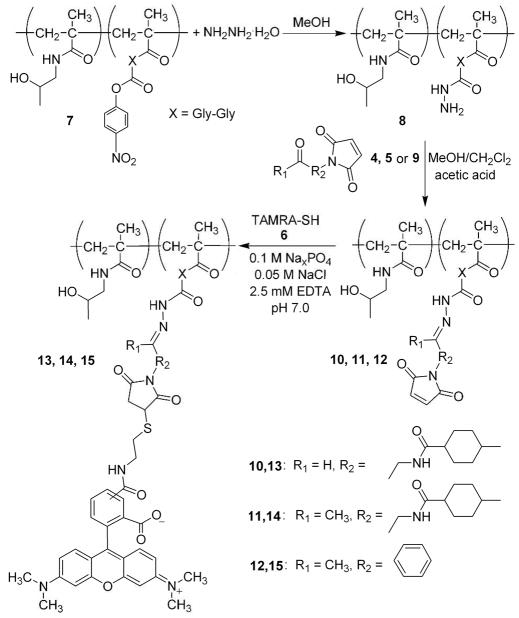

This work evaluates three heterobifunctional crosslinkers designed to couple thiol-containing molecules to hydrazone-derivatized pHPMA drug carriers enjoying a long history of use (9, 10, 27). Thiol-based drug conjugation to polymer-linked hydrazones is not widely studied. Efficiency of crosslinker coupling to reactive sites on the polymer backbone, and their subsequent stability at pH 7.4 and 5.0 were investigated. While both polymer and crosslinker can be designed to provide the hydrazide functionality, we placed this functional group on the polymer carrier as previously described (19, 20). Crosslinkers reactive to thiol coupling contain ketone or aldehyde functional groups on one terminus for reaction with pHPMA hydrazide groups, and a maleimide functionality at the other terminus to react with sulfhydryl groups on a different adduct via 1,4-Michael addition reactions (19, 20). This thiol coupling strategy is advantageous for coupling unmodified proteins/peptides lacking aldehyde/ketone functionality, or other thiol-containing molecules, to known hydrazide-derivatized pHPMA water-soluble carriers, or analogous chemistry. Two heterobifunctional crosslinkers investigated, 1-(N-3-propanal)-4-(N-maleimidomethyl) cyclohexane carboxamide (PMCA), and 1-(N-3-butanone)-4-(N-maleimidomethyl) cyclohexane carboxamide (BMCA) were prepared from the popular commercial crosslinker succinimidyl-4-(N-maleimidomethyl) cyclohexane-1-carboxylate (SMCC), while the third was a commercially available benzene derivative, N-4-acetylphenyl maleimide. Illustration of the reversible coupling/release strategy and crosslinking chemistry structures involving hydrazone-thiol coupling are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Design strategy for reversible coupling of thiols to pHPMA and crosslinker structures.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

General Procedures and Materials

All solvents were ACS-certified grade purchased from Fisher Scientific (Fair Lawn, USA) and used without further purification unless otherwise noted. Trinitrobenzene sulfonic acid (5% w/v solution in methanol) (TNBSA), cystamine hydrochloride (98%), diisopropylethylamine (DIPEA), ethyl carbazate (97%), N-hydroxysuccinamide (NHS) (98%), 4-(aminomethyl)cyclohexane carboxylic acid (97%), maleic anhydride (98+%), acetic anhydride, dicyclohexanecarbodiimide (DCC) (99%), hydrazine monohydrate (98%), 3-amino-1-propanol (99+%), triethyl amine (99.5%), oxalyl chloride (99+%) and glacial acetic acid, were all purchased from Aldrich (St. Louis, USA). N-4-(acetylphenyl) maleimide (APM) (98+%) was purchased from Lancaster Synthesis (Pelham, USA). 4-Amino-2-butanol (98%) was purchased from Acros Organics, (Geel, Belgium). Reducing gel with immobilized tris(2-carboxyethyl) phosphine hydrochloride (TCEP) was purchased from Pierce (Rockford, USA). Spectra/Por 1, 6–8 kDa molecular weight cut-off dialysis tubing was obtained from Spectrum Laboratories, Inc. (Rancho Dominguez, USA). Sephadex G-25 and LH-20 size exclusion chromatography gel was purchased from Amersham Biosciences (Uppsala, Sweden). Dimethyl sulfoxide-d6 containing 0.05% w/v tetramethylsilane was purchased from Cambridge Isotope Laboratories, Inc. (Andover, MA). 5(6)- Tetramethylrhodamine-succinimidyl ester (TAMRA-NHS) was obtained from AnaSpec (San Jose, USA). Poly(HPMA) molecular weight standards were a gift from Prof. P. Kopeckova, Univ. Utah, USA. Water was Millipore-filtered ASTM Type I quality. All NMR spectra were recorded on a Magnex Scientific Inova 400 MHz instrument in DMSO-d6 containing 5% w/v tetramethylsilane as an internal standard. Absorbance measurements were obtained on a Varian Carey 500 Scan instrument.

4-(N-maleimidomethyl) cyclohexane carboxylic acid (MCCA) (1)

4-(Aminomethyl) cyclohexane carboxylic acid (40.71 g, 0.26 mol, 1 eq) was dissolved in dimethyl acetamide (DMAc, 100 mL). A solution of maleic anhydride (25.20 g, 0.26 mol, 1 eq) was prepared in DMAc (50 mL), then added to the 4-(aminomethyl) cyclohexane carboxylic acid solution drop-wise while stirring. The reaction vessel was purged with nitrogen, capped and stirred for 24 hr at room temperature. After 24 hr, sodium acetate (5.00 g, 0.06 mol, 0.24 eq) and acetic anhydride (43 mL, 0.455 mol, 1.75 eq) were added and the reaction was continued for an additional 24 hrs. After 24 hrs, the reaction was heated to 65 °C and stirred for 5 hrs, then concentrated to ~125 mL under vacuum and poured into 1L cold water while stirring. The light-brown precipitate was collected by filtration and dried under vacuum. The aqueous portion was extracted twice with methylene chloride (500 mL), and product was isolated after evaporation of solvent. Both solid portions were combined and dissolved in methylene chloride (500 mL) then silica gel (5 g) was added to the solution, and the suspension was stirred for 30 min. The resulting colorless solution was filtered and solid product was obtained by evaporation of solvent under vacuum. Crude product was further purified by crystallization from ethyl acetate to yield a white solid. Yield: 14.70 g, 24 %. 1H NMR, δ ppm: 0.926 (dd, 2H), 1.22 (dd, 2H), 1.517 (m, 1H), 1.6165 (d, 2H), 1.869 (d, 2H), 2.109 (m, 1H), 3.2355 (d, 2H), 7.012 (s, 2H), 12.010 (s, 1H). 13C NMR, δ ppm: 27.932, 29.112, 36.013, 42.105, 42.861, 134.273, 171.549, 176.497. MS calcd [M + H]+ (C12H15NO4): 238.107. Found: (FAB) 238.108.

1-(N-3-propanol)-4-(N-maleimidomethyl) cyclohexane carboxamide (2)

Crosslinker precursor MCAA (3.00 g, 1.0 equiv., 13 mmol) was dissolved in methylene chloride (75 mL), purged with nitrogen, capped, and cooled to −15°C. A suspension of NHS was prepared (1.45 g, 1.0 equiv, 13 mmol) in methylene chloride (25mL), then cooled to −15 °C. Next, a solution of DCC was prepared (2.87g, 1.1 equiv, 14 mmol) in methylene chloride (25 mL) and cooled to −15°C. The DCC solution was added to the solution of MCAA, followed by addition of the NHS suspension. The reaction flask was purged with nitrogen, stirred at −15°C for 24 hr, and then filtered to remove dicyclohexylurea (DCU). The filtrate was retained and 3-amino-1-propanol (1.98 mL, 1.9 equiv, 25 mmol) was added drop-wise. The reaction was purged with nitrogen, capped, and stirred at room temperature for 3 hr. After 3 hr, the reaction mixture was filtered to remove liberated NHS and the filtrate was concentrated to ~2/3 original volume under vacuum, cooled to −20°C, then refiltered. The resulting filtrate volume was doubled by addition of diethyl ether to form a precipitate, which was isolated by filtration. The solid product was further purified by silica gel chromatography (10 × 40 cm, 90/10 methylene chloride/methanol mobile phase) and isolated by evaporation of solvent under vacuum. Yield: 1.91 g, 51.6%, white solid. 1H NMR, δ ppm: 0.886 (dd, 2H), 1.265 (dd, 2H), 1.508 (q, 3H), 1.618 (d, 2H), 1.682 (d, 2H), 1.998 (m, 1H), 2.5 (solvent overlap), 3.047 (q, 2H), 3.234 (d, 2H), 3.372 (q, 2H), 4.399 (t, 1H), 7.013 (s, 2H), 7.652 (t, 1H). 13C NMR, δ ppm: 28.488, 29.349, 32.386, 35.423, 36.060, 42.980, 43.704, 58.307, 134.277, 171.188, 174.825. MS calcd [M + H]+ (C15H22N2O4): 295.1657. Found: (FAB) 295.1654.

1-(N-3-butanol)-4-(N-maleimidomethyl) cyclohexane carboxamide (3)

This product was obtained by an analogous procedure used to synthesize compound 2 (vida infra) with the only difference being the use of 4-amino-2-butanol (1.65 mL, 1.1 equiv, 17.3 mmol) in methylene chloride (30 mL) as the amidation reagent. Yield: 2.88 g, 60%, white powder. 1H NMR, δ ppm: 0.887 (dd, 2H), 1.036 (d, 3H), 1.267 (dd, 2H), 1.521 (m, 1H), 1.620 (d, 2H), 1.686 (d, 2H), 1.998, (m, 1H), 3.065 (q, 2H), 3.240 (d, 2H), 3.585 (septet, 1H), 4.443 (d, 1H), 7.018 (s, 2H), 7.645 (t, 1H). 13C NMR, δ ppm: 23.509, 28.459, 29.334, 35.489, 36.046, 38.719, 42.966, 43.694, 63.628, 134.267, 171.168, 174.776. MS calcd [M + H]+ (C16H24N2O4): 309.1814. Found (FAB) 309.1819.

1-(N-3-propanal)-4-(N-maleimidomethyl) cyclohexane carboxamide, PMCA (4)

PMCA was prepared using the Swern procedure for oxidation of alcohol to aldehyde.(28) The alcohol 2 (500 mg, 1.0 equiv, 1.72 mmol) was dissolved in freshly distilled methylene chloride (20 mL) and cooled to −80°C. An activated dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) solution was prepared by combining DMSO (295 μL, 2.4 equiv, 4.13 mmol) and oxalyl chloride (950 μL of 2.0 M solution in methylene chloride, 1.1 equiv, 1.9 mmol) in methylene chloride (1.5 mL) at −80°C. The alcohol solution was slowly added to the activated DMSO solution over 5 minutes. The reaction was allowed to proceed for 15 minutes at −80°C, followed by addition of triethylamine (1.2 mL, 5.0 equiv, 8.5 mmol). The reaction was equilibrated to room temperature then water (15 mL) was added and the mixture was stirred for 10 minutes. The organic layer was separated, and the aqueous portion was re-extracted with 2 × 10 mL methylene chloride, then all organic portions were combined. The organic portion was washed with 1 M HCl, dilute NaHCO3, and H2O, then dried with Na2SO4. Product was isolated after removal of Na2SO4 and evaporation of solvent. Yield: 0.350g, 66%, white powder. 1H NMR, δ ppm: 0.878 (dd, 2H), 1.232 (dd, 2H), 1.507 (m, 1H), 1.636 (m, 2H), 1.976 (m, 1H), 2.502, (solvent overlap) 3.23 (d, 2H), 3.284 (q, 2H), 7.011 (s, 1H), 7.796 (t, 1H), 9.604 (t, 1H). 13C NMR, δ ppm: 28.378, 29.286, 32.393, 36.037, 42.957, 43.265, 43.566, 134.274, 171.185, 174.958, 202.195. MS calcd [M + H]+ (C15H20N2O4): 293.1501. Found (FAB) 293.1507.

1-(N-3-butanone)-4-(N-maleimidomethyl) cyclohexane carboxamide, BMCA, (5)

BMCA was prepared using the same Swern procedure described above to prepare PMCA, except starting with 3 (2.00 g, 1.0 equiv, 6.5 mmol) as the alcohol to be oxidized. Yield: 1.34 g, 68%, white powder. 1H NMR, δ ppm: 0.875 (q, 2H), 1.243 (q, 2H), 1.511 (m, 1H), 1.511 (m, 1H), 1.638 (m, 4H), 1.975 (m, 1H), 2.070 (s, 3H), 2.545 (t, 2H), 3.180 (q, 2H), 3.228 (d, 2H), 7.011 (s, 2H), 7.677 (t, 1H). 13C NMR, δ ppm: 28.407, 29.305, 29.752, 33.626, 36.043, 42.620, 42.962, 43.548, 134.273, 171.179, 174.796, 207.179. MS calcd [M + H]+ (C16H22N2O4): 307.1657. Found (FAB): 307.1657.

Thiol-containing tetramethylrhodamine (6)

Thiolated tetramethylrhodamine was prepared by reaction of TAMRA-NHS with cystamine hydrochloride activated with diisopropylethylamine (DIPEA) to form the TAMRA disulfide dimer (ssTAMRA) as previously described (29). Briefly, cystamine hydrochloride (9.6 mg, 0.9 equiv amines, 0.043 mmol) was activated in dimethylformamide (DMF, 2.5 mL) containing DIPEA (30 μL, 1.8 equiv, 0.17 mmol). This solution was added to TAMRA-NHS (50.0 mg, 1.0 equiv, 0.095 mmol) in DMF (1.5 mL) and stirred at room temperature in the dark for 30 minutes followed by addition of DIPEA (15 μL, 0.086 mmol, 1.0 eq) and reaction for an additional hour. Product was precipitated by addition of 50 mL cold diethyl ether, washed five times, and dried under vacuum overnight. Further purification was achieved by repeat precipitation from methanol into cold ether. Yield: 24.81 mg, 54%, dark red solid. MS calcd [M+H]+ (C54H52N6O8S2): 977.3366. Found (FAB): 977.3348.

poly[N-(2-hydroxypropyl) methacrylamide], pHPMA (7)

PHPMA was synthesized to contain 5 mol% reactive nitrophenol ester terminated, non-degradable glycylglycine side chains using previously described procedures (30–32). N-(2-hydroxypropyl) methacrylamide (HPMA) and methacryloyl glycylglycine nitrophenol ester (MAGGONP) monomers were prepared in house and confirmed with NMR and mass spectrometry. A detailed procedure for monomer synthesis and subsequent polymerization is provided as supporting information. The number of active esters in the resulting copolymer was estimated to be 2.55 × 10−4 mol/g polymer, 3.8 mol% by measuring the absorbance of released p-nitrophenolate anion at 400 nm (ε = 1.74 × 104 M−1cm−1) following hydrolysis of ester bonds in 0.05 M sodium hydroxide for 3 hr at 37°C. No increase in absorbance after the 3 hr incubation period was observed, showing complete cleavage of p-nitrophenol esters. Copolymer molecular weight was estimated to be 18,200 Da by size exclusion chromatography using a HP1050A HPLC equipped with a HP1047A refractive index detector and BioSil 125 column calibrated with pHPMA samples of known molecular weight. Samples were eluted at 0.5 mL/min with 0.1M sodium phosphate, 0.05M NaCl, pH 7.4.

Hydrazide derivatized pHPMA (8)

pHPMA copolymer was further modified to contain hydrazide-terminated side chains by reaction of p-nitrophenol ester-terminated MAGGONP side chains with excess hydrazine monohydrate using methods previously described (19, 20). Briefly, p-nitrophenol activated pHPMA (2.0 g, 1.0 equiv, 0.51 mmol active ester) was dissolved in methanol (25 mL). The pHPMA solution was added drop wise to a solution of hydrazine monohydrate (267 μL, 10.8 equiv, 5.5 mmol) in methanol (25 mL). The reaction was purged with nitrogen, capped, and stirred for 3 hr at room temperature. The reaction solution turned dark yellow indicating reaction of active ester groups and release of p-nitrophenol. After complete reaction, the reaction mixture was dripped into cold water (50 mL) and low molecular weight byproducts were removed by dialysis against water (SpectraPore, 6–8 kDa molecular weight cut-off, 2 days). Polymer product was isolated by lyophilization. Yield: 0.120 g, 60%, white powder. Hydrazide content: 2.63 × 10−4 mol/g, 100.5% conversion.

Analysis of pHPMA hydrazide content

Hydrazide content was estimated using a modified trinitrobenzene sulfonic acid (TNBSA) assay and methacryloyl glycylglycine hydrazide (MAGGH) standards (see Supporting Information for details regarding synthesis of MAGGH standards). For each pHPMA hydrazide content analysis, stock solutions of 0.1% w/v TNBSA and ~ 2 × 10−4M MAGGH were prepared in 0.1M NaHCO3, pH 8.5. The MAGGH solution was further diluted with 0.1 M NaHCO3 to generate standards in the range of ~0.3–2 × 10−4M. Next, hydrazide derivatized pHPMA solutions in 0.1 M NaHCO3 were prepared at concentrations of 0.2–0.4 mg/mL for samples prior to crosslinker reactions, and 1–2 mg/mL for crosslinker reacted samples. TNBSA stock solution (0.5 mL) was combined with MAGGH standard or pHPMA solutions (1.0 mL) and incubated for 1.5 hr at 37°C. After incubation, sample absorbance was measured at 505 nm and hydrazide content was estimated from the MAGGH standard curve.

Reaction of hydrazide-derivatized pHPMA with crosslinkers (10, 11, 12)

Hydrazide-derivatized pHPMA (8, 0.20 g, 1.0 equiv, 52 μmol hydrazide) was dissolved in 50/50 methylene chloride/methanol (2 mL), and 100 mg Na2SO4 was added. Crosslinker solutions (PMCA, 4, 46.0 mg, BMCA, 5, 48.0 mg, APM, 9, 34.0 mg, 3.1 equiv, 160 μmol) were prepared in 50/50 methylene chloride/methanol (2 mL) and then added drop-wise to the pHPMA solution at room temperature. After complete addition, acetic acid (5 μL of 34% v/v solution in methylene chloride, 0.6 equiv, 30 μmol) was added and the reaction was stirred under nitrogen at room temperature for 24 hr. The reaction was terminated by precipitation of pHPMA product into ether. Product was further purified by size exclusion chromatography (Sephadex LH-20, 1 × 15 cm, methanol mobile phase). Typical yields: pHPMA-PMCA 10: 116 mg 59%; pHPMA-BMCA 11: 122 mg, 61%; pHPMA-APM 12: 126 mg, 63%, all as white powders. Hydrazide content post-conjugation was determined using a TNBSA assay, as described above. Crosslinker content was determined by optical absorbance measurement at λmax and using the molar extinction coefficients of corresponding ethyl carbazate crosslinker hydrazone derivatives 10: 297 nm, ε = 5.5 × 102 M−1 cm−1; 11: 299 nm, ε = 5.7 × 102 M−1 cm−1; 12: 288 nm, ε = 1.9 × 104 M−1 cm−1 (see Supporting Information). Polymer crosslinker-bearing conjugates were analyzed by 1H NMR to confirm maleimide presence on the polymer backbone.

Coupling thiolated TAMRA to maleimide activated pHPMA (13, 14, 15)

Dimeric TAMRA disulfide 6 was reduced using TCEP-immobilized gel immediately prior to reaction with crosslinker-derivatized pHPMA. TAMRA disulfide dimer (17.46 mg, 0.036 mmol, 1 eq) was dissolved in 1 mL DMSO and added dropwise into an immobilized TCEP gel suspension (5 mL gel, ~ 1.1 equiv, ~ 0.04 mmol TCEP) in 12 mL phosphate buffer (0.1M sodium phosphate, 0.05 M NaCl, 2.5 mM EDTA, pH 7.0). The reduction reaction was allowed to proceed for 1.25 hr, followed by removal of TCEP gel by centrifugation. The gel material was washed with 6 mL buffer (pH 7.0, 2.5 mM EDTA), centrifuged, and the supernatant was retained and combined with the first fraction.

Reduced TAMRA solution (3 mL,~ 1.1 equiv,~ 5.9 μmol) was added separately to pHPMA crosslinker conjugates 10, 11, and 12 (20.0 mg in 2 mL sodium phosphate, 0.05 M NaCl, 2.5 mM EDTA, pH 7.0, ~ 1 equiv, ~5.3 μmol). Reaction mixtures were degassed, purged with nitrogen, capped, and stirred at room temperature in the dark for 3 hr. The coupling procedure was terminated by separation of unreacted TAMRA thiol after passage through an SEC column (Sephadex, G-25, 2 × 20 cm, H2O mobile phase). The polymer conjugate fraction was collected as the first red band eluting from the column and lyophilized. Typical yields of TAMRA conjugated pHPMA: 15.3–19.5 mg, 76–96%. TAMRA conjugation efficiency to maleimide groups was determined by absorbance measurements at 554 nm using ε = 6.4 × 104 M−1cm−1. TAMRA content (μmol/g polymer): 13 = 105.2, 14 = 47.8, 15 = 25.9.

Determination of decoupling hydrolysis rates for crosslinkers on conjugates 13–15

Release of free TAMRA dye from pHPMA was monitored at pH 5.0 (0.1M sodium acetate buffer) and pH 7.4 (0.1M sodium phosphate buffer). TAMRA-conjugated pHPMA samples (1.5–2.5 mg) were dissolved in the appropriate buffer (8.5 mL) and incubated at 37°C in the dark while stirring. At various time points, 750 μL of polymer solution was withdrawn and free TAMRA was separated from polymer using a Sephadex G-25 SEC column (1 × 13 cm, H2O mobile phase). The two resulting bands were collected and water was evaporated using a speed-vac. The samples were then dissolved in 500 μL water and % free TAMRA was determined by the ratio of absorbance at 554 nm of the two fractions. For pHPMA conjugate 15, TAMRA release was also determined after acidification (pH 3.0) of a sample incubated for 72 hrs at pH 7.4 (0.1M phosphate buffer). All release experiments comprised 4 individual samples and data was analyzed using Microsoft Excel.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Crosslinker design and synthesis

Although several heterobifunctional crosslinkers are commercially available that form hydrazone bonds and also contain thiol-coupling reactivity, most are synthesized to contain hydrazide groups that react with synthetic ketone-containing drugs such as doxorubicin or oxidized sugar moieties present on biomolecules. We know of only one commercially available crosslinker that contains both ketone and maleimide functionality (APM), since hydrazide groups are not a common target for reaction with biomolecules or synthetic drugs. However, synthetic polymers, particles, surfaces etc. can easily be prepared with hydrazide functionality for reversible conjugation of thiolated molecules using the crosslinkers described in this work.

Synthesis of the aldehyde or methyl ketone SMCC-based heterobifunctional crosslinkers is shown in Scheme 1. The cyclohexyl SMCC core was chosen as it is known to produce a stable maleimide functional group. Maleimide groups are subject to degradation by hydrolysis and the increased hydrophobicity and lack of a conjugated aromatic system in the cyclohexyl spacer may reduce the hydrolysis rate (2, 33). Early attempts to synthesize these crosslinkers involved direct modification of commercially available SMCC, but synthesis of SMCC precursors in-house allowed inexpensive scale-up. Synthesis of the corresponding alcohols of SMCC was performed in a one-pot reaction after activation of carboxylic acid with NHS using well-known carbodiimide chemistry (2). Direct coupling of 4-amino-2-butanol and 3-amino-1-propanol to 4-(N-maleimidomethyl) cyclohexane carboxylic acid (1) following DCC activation without NHS led to a mixture of products, presumably due to addition of alcohol groups to the highly reactive DCC-activated carboxylic acid. The choice of methylene chloride as the solvent aided in product purification due to the limited solubility of NHS by-product, which precipitated from solution and was easily removed by filtration after concentration and cooling the reaction mixture. Residual NHS was removed by aqueous extraction for crosslinker precursor 3, but this purification strategy for 2 resulted in reduced yields due to higher water solubility. Chromatographic purification of 2 resulted in markedly increased yields.

Scheme 1.

Thiol-reactive crosslinker synthesis

Oxidation of alcohol groups in crosslinker precursors 2 and 3 was readily achieved using the mild oxidation conditions of the Swern procedure to yield the corresponding aldehyde- and methylketone- containing reactive crosslinkers. No side reactions were observed with other functional groups in the molecule. Other attempts to oxidize the alcohol functional groups using pyridinium chlorochromate resulted in oxidation of alcohol groups, but removal of chromium salt by-products was difficult, resulting in low yields (data not shown).

Crosslinker coupling to pHPMA

Synthesis of hydrazide-derivatized pHPMA (8) was easily achieved by reaction of active p-nitrophenol esters on pendant side chains with hydrazine monohydrate as previously described (19, 20). This construct has been previously utilized to couple doxorubicin via a hydrazone bond to allow pH-dependent release (19, 20). The number of reactive sites in pHPMA was controlled by monomer feed ratios in the free radical-initiated polymerization reaction to produce pHPMA with reactive sites kept fairly low so as to not alter the polymer solubility after crosslinker conjugation. Formation of hydrazone bonds has been reported for doxorubicin conjugates with pHPMA and poly(ethylene glycol) in polar protic conditions with methanol used as the solvent, and acetic acid as the catalyst (19, 20). Since the hydrophobic crosslinkers used in this study were only minimally soluble in methanol, and the more hydrophilic pHPMA was only minimally soluble in solvents ideal for crosslinker solvation, a mixed solvent system was used. The best methanol-based solvent system for optimal crosslinker/polymer solubility was found to be 50/50 methanol/methylene chloride. PHPMA-crosslinker reactions showing conjugation efficiency are summarized in Table 1. With the reactive sites on the polymer controlled by monomer feed ratio, an excess of crosslinker was used to maximize conjugation to the polymer.

Table 1.

Summary of pHPMA-crosslinker coupling reactions

| polymer conjugate | crosslinker | crosslinker contenta (μmol/g) | conversion (%) | remaining hydrazideb (μmol/g) | conversion (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 13 | PMCA | 373.0 ± 21.2 | 141.8 ± 8.1 | 19.5 ± 0.1 | 92.6 ± 4.3 |

| 14 | BMCA | 248.9 ± 8.1 | 94.6 ± 3.1 | 18.6 ± 0.1 | 92.9 ± 5.6 |

| 15 | APM | 166.7 ± 14.5 | 69.8 ± 6.1 | 90.9 ± .1 | 62.0 ± 1.9 |

n=4 for all measurements

determined by crosslinker optical absorbance

determined by TNBSA assay

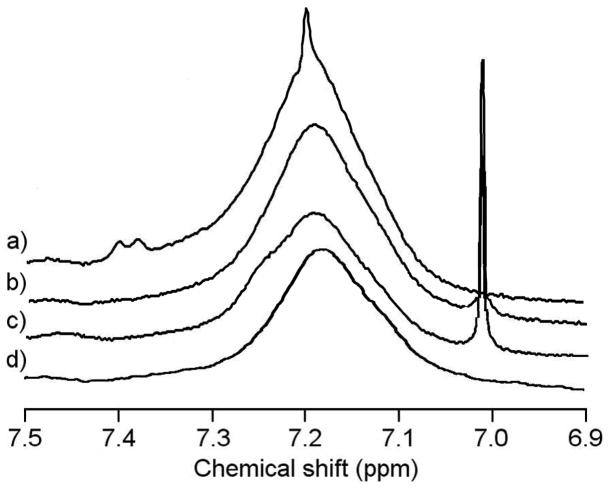

Reaction of crosslinkers PMCA (4) and BMCA (5) resulted in complete conversion of hydrazide groups to hydrazone conjugates as determined directly by crosslinker absorbance and indirectly by determination of remaining hydrazide groups using TNBSA measurements. Optical absorption measurements of the pHPMA-PMCA crosslinker product 10 showed the highest coupling efficiency, indicative of the higher reactivity of aldehyde functional groups. Although more than stoichiometric conversion was observed for the aldehyde crosslinker, the excess coupling is small compared to the total polymer units in the pHPMA carrier, indicating that polymer units lacking the hydrazide functionality were generally unreactive towards the aldehyde. The amount of hydrazide containing monomer units in pHPMA was ~4 mole %, thus the ~140% coupling of the aldehyde crosslinker observed under these reaction conditions corresponds to modification of only ~2% of the polymer side chains in an unintended fashion. One possible explanation for the higher coupling rate observed for the aldehyde crosslinker is the formation of acetals with the alcohol groups contained in pHPMA side chains or mixed acetals formed by reaction with pHPMA and MeOH, as the reaction conditions used for hydrazone formation are similar to those used for acetal formation (i.e. acid catalyst and dehydrating agent). The methylketone group of 5 reacted with pHPMA hydrazide groups in a stoichiometric fashion, with absorbance and remaining hydrazide content in good agreement for conjugate 11. This demonstrates that the less reactive methyl ketone functionality resulted in more readily controlled conjugation. The resonance stabilized APM crosslinker 9 was less reactive and did not stoichiometrically react with hydrazide-containing pHPMA 8 to produce conjugate 12. Only 60–70% conjugation was observed in the crosslinker-derivatized product 12, with crosslinker absorbance and remaining hydrazide measurement in good agreement. A similar result was observed in the analogous reaction of APM with ethyl carbazate (see Supporting Information). 1H NMR analysis of the crosslinker polymer conjugates 10–12 also revealed a convenient analytical signal to confirm conjugation due to the sharp maleimide peak at 7.0–7.2 ppm, shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

1H NMR spectra of pHPMA conjugates showing the pHPMA amide peak (broad) and crosslinker maleimide peak (sharp). Spectra recorded at 400 MHz, 25°C in DMSO-d6. (a) pHPMA-APM conjugate 12, (b) pHPMA-BMCA conjugate 11, (c) pHPMA-PMCA conjugate 10, (d) pHPMA-hydrazide 8.

For conjugates 10 and 11, the maleimide peak appeared in an unobscured region of the 1H NMR spectrum allowing easy detection. Additionally, formation of conjugate 10 was confirmed by the disappearance of the aldehyde peak present in unreacted crosslinker 4 at 9.6 ppm. Although the maleimide signal overlapped with the polymer backbone signal for conjugate 12 containing APM, it was still visible protruding above the broad amide peak. Additionally, the ability of each crosslinker to form hydrazone linkages was modeled with the hydrazide-containing small molecule ethyl carbazate, with confirmation of hydrazone formation more analytically straightforward than with a small percentage of reactive sites in a polymer conjugate (see Supporting Information). For PMCA and BMCA, rapid, stoichiometric conversion to hydrazone product was obtained, with only a simple purification procedure needed to isolate pure hydrazone product. However, reaction of APM with ethyl carbazate resulted in formation of several products and purification required a separation procedure for isolation, which resulted in a lower overall yield.

Attachment of thiolated TAMRA to pHPMA and subsequent release

Synthesis of the pHPMA crosslinker TAMRA conjugates 13–15 is shown in Scheme 2. Thiol-modified TAMRA (6) was used as a model cargo compound to react with maleimide groups resulting from crosslinker conjugation to pHPMA. This model system was convenient as TAMRA is fairly water-soluble, readily detected by simple absorbance measurements and released dye is sufficiently smaller in size to allow rapid separation from the polymer-bound fraction using size exclusion chromatography. Reduction of the TAMRA disulfide 6 was performed with TCEP-immobilized gel, allowing easy separation of reducing agent. Free TCEP, DTT, or combinations of both resulted in lower conjugation of TAMRA to the polymer (data not shown). Although free TCEP is generally believed to be unreactive towards maleimide functional groups, similar observations regarding interference with maleimide coupling have been reported (34, 35). Reaction times of TAMRA with crosslinker-derivatized pHPMA were kept short (3 h) in this study, as degradation rates of the hydrazones were unknown. TAMRA conjugation was not efficient under these conditions, with couplings relative to crosslinker content of ~20% for all pHPMA-crosslinker conjugates. Maleimide coupling efficiency for all crosslinkers may increase with longer reaction times until hydrazone degradation and release from the polymer competes with thiol conjugation.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of pHPMA conjugates

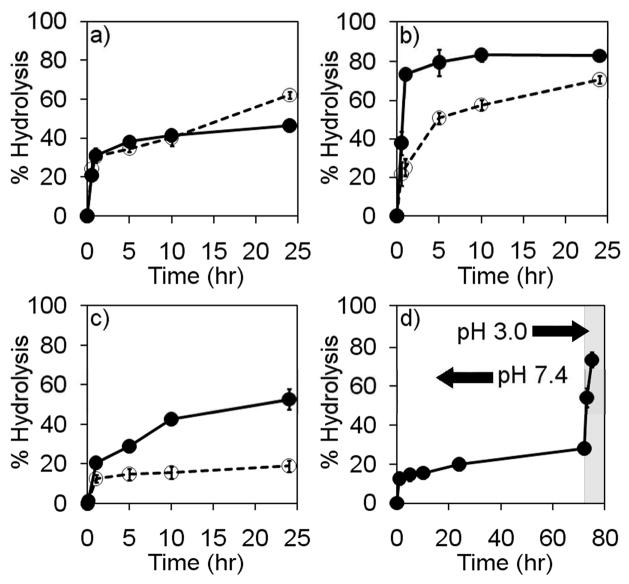

Release of conjugated TAMRA from the polymer backbone at physiologically relevant temperature and pH [pH 7.4 (circulation) and pH 5.0 (lysosomes), 37°C] was influenced by crosslinker structure as shown in Figures 3a–c. The conditions used to observe hydrazone degradation are not physiological, as the addition of other physiologically relevant components such as serum interfere with the ability to separate released TAMRA dye from the macromolecular component of the mixture by size exclusion chromatography: TAMRA can associate with high molecular weight serum components in more complex milieu via non-specific interactions. Ideally, for systemic administration of a drug delivery system, the hydrolytic stability of the hydrazone bond between the carrier and therapeutic agent should be stable at systemic pH (~7.4) for same period of time that it takes for the carrier to reach its site of activity. However, if the carrier is rapidly cleared from circulation, and the therapeutic target is also the site of rapid accumulation (i.e. kidney or liver tissue), the hydrazone does not necessarily need to exhibit extended stability at systemic pH. For carriers targeting cancer tissue by the EPR effect, the hydrazone used for preparation of the conjugate should exhibit minimal hydrolysis at pH 7.4 as accumulation into cancer tissue by the EPR effect requires a carrier with extended circulation (36). In this regard, the stability of the hydrazone used to couple the therapeutic agent to the carrier depends on the properties of the carrier used.

Figure 3.

Hydrolysis rates for pHPMA-crosslinker-TAMRA conjugates. Graphs a–c represent hydrolysis at pH 7.4  and pH 5.0

and pH 5.0  : (a) pHPMA-PMCA-TAMRA conjugate 13, (b) pHPMA-BMCA-TAMRA conjugate 14, (c) pHPMA-APM-TAMRA conjugate 15. (d) Hydrolysis of pHPMA-APM-TAMRA conjugate 15 upon acidification following 75 hr incubation at pH 7.4. Each data point represents the average of 4 samples ± the standard deviation.

: (a) pHPMA-PMCA-TAMRA conjugate 13, (b) pHPMA-BMCA-TAMRA conjugate 14, (c) pHPMA-APM-TAMRA conjugate 15. (d) Hydrolysis of pHPMA-APM-TAMRA conjugate 15 upon acidification following 75 hr incubation at pH 7.4. Each data point represents the average of 4 samples ± the standard deviation.

Polymer conjugates 13 and 14 containing aliphatic acyl hydrazone bonds were relatively unstable at physiological pH, with more than 30% of conjugated TAMRA released after 5 hr. Release for conjugate 13 prepared with the aldehyde-containing PMCA crosslinker showed no difference between pH 7.4 and 5.0, with a maximum of 40–60% release observed after only a few hours, with little increase after 24 hr. Hydrolysis of conjugate 13 rapidly plateaued at a value less than complete hydrolysis, which may be attributed to the reversible nature of the hydrazone bond and the closed system used to study the release profile which could result in the highly reactive aldehyde-containing PMCA crosslinker reaching equilibrium between the aldehyde and hydrazone forms at this concentration and temperature. Alternatively, the additional PMCA attached to the polymer (~140% conjugation to pHPMA was observed) could be interfering with the observation of hydrazone bond hydrolysis, assuming that the additional conjugation resulted in a hydrolytically unstable bond (i.e. acetal). Polymer conjugate 14 formed with the BMCA crosslinker showed a marked difference in hydrazone degradation at early time points, with more than 75% of cargo released after only 2 hrs at pH 5.0 while only 25% of TAMRA was released at pH 7.4 in the same time frame. This difference in initial pH stability for BMCA containing conjugate 14 compared to the hydrazone formed with PMCA in conjugate 13 is likely due to increased electron donation ability of a methyl group relative to a hydrogen, which would facilitate protonation of the imine nitrogen but also sterically hinder the imine carbon electrophile towards nucleophilic attack by water. This property may be useful for targeting or delivery devices that can efficiently reach a target site of lower pH without prolonged residence in the off-target environment, with rapid release of cargo at the site of lower pH.

The desired difference in stability of polymer conjugates at pH 7.4 and 5.0 was most pronounced for the pHPMA-APM containing conjugate 15. Polymer conjugate 15 containing the resonance-stabilized hydrazone was most stable at pH 7.4 with less than 30% of degradation occurring after 24 hours, while degradation at pH 5.0 steadily increased during the same time period (Figure 3c). Increased degradation rate of conjugate 15 upon acidification after extended incubation at pH 7.4 is shown in Figure 3d, hydrolysis increased immediately upon lowering the pH. This result shows that polymer-bound payload is likely to be released within target cells in vivo following extended circulation, cellular internalization, and trafficking to acidic subcellular organelles (lysosomes).

Hydrazones investigated in this work showed the following trend for increased difference in stability at pH 7.4 and 5.0 based on the functional groups attached to the imine carbon: phenyl, CH3 > alkyl, CH3 > alkyl, H. A similar trend has also been observed for other hydrazone systems, recently reviewed elsewhere (15). This trend is directly related to crosslinker reactivity towards polymer hydrazide groups, with highly reactive carbonyl groups forming hydrazone bonds with decreased pH-dependent hydrolysis. The acyl hydrazide functionality utilized on the pHPMA component of the hydrazone forming system was not varied but the acyl hydrazide was convenient to prepare by simple aminolysis of active esters by hydrazine and also likely aided in the stability of the resulting hydrazones at pH 7.4. A recent detailed study of hydrazone stability showed that an acyl hydrazone had a first-order rate constant for hydrolysis a few hundred-fold lower relative to an alkyl hydrazone at pH 7.0 (37).

The pH-dependent release mechanism for hydrazone hydrolysis involves: 1) protonation of the imine nitrogen, 2) nucleophilic attack of a water molecule at the imine carbon, 3) formation of a tetrahedral carbinolamine intermediate and 4) decomposition of the carbinolamine and cleavage of the C-N bond (15, 17, 37, 38). The rate at which this hydrolysis occurs is influenced by substituents adjacent to the hydrazone. In general, crosslinker electron-donating groups can facilitate pH-dependent hydrolysis by encouraging protonation of the imine nitrogen, which activates the imine carbon towards nucleophilic attack from water as the nitrogen can then accept a pair of electrons from the imine bond to form the tetrahedral carbinolamine intermediate. Electron withdrawing groups decrease pH sensitivity by decreasing electron density of the imine carbon making it more susceptible to nucleophilic attack by water (15, 37, 39, 40). Aromatic groups in π-bond conjugation with hydrazones have also been shown to increase their stability, due to resonance stabilization, as was observed in our results (41). The desired stability for controlled pH-dependent hydrolysis is dependent on a delicate balance of groups adjacent to the carbonyl and hydrazide reaction partners used to form the hydrazone.

Modification of the carbonyl portion of crosslinkers described here may result in increased stability at pH 7.4 and hydrolysis rate at pH 5.0, while retaining excellent hydrazide reactivity. For example, glyoxylyl aldehydes prepared from N-terminal serine modified amino acids have been recently used to form pH-sensitive hydrazones with acyl hydrazides (42). These findings suggest that further optimization of the SMCC-based crosslinker chemistries described here could be achieved by incorporation of different chemistries on carbon atoms adjacent to the reactive ketone functionality.

CONCLUSIONS

This work demonstrates the feasibility of forming thiol-reactive pHPMA conjugates with varying coupling and decoupling stability controlled by different chemical substitution patterns in analogous heterobifunctional crosslinker chemistries. Currently, the APM crosslinker is likely the best choice for long-circulation in vivo application due to the high stability at pH 7.4, with desired increased degradation occurring in acidic conditions analogous to the lysosome environment within cells. However, although APM shows the desired release properties for a long circulating conjugate, this crosslinker has the inherent disadvantage of lower hydrazide reactivity. BMCA is attractive for use where rapid release of cargo at a target site where extended stability is not desired (i.e. conjugates that rapidly accumulate at their site of activity or those that need to be rapidly cleared after use, i.e., gadolinium imaging agents). Alternatively, modifications of chemistry contained in the hydrazide part of synthetic constructs could result in conjugates with more stable hydrazone linkages formed with PMCA and BMCA.

The utility of these thiol-reactive crosslinkers may be further extended to produce non-degradable conjugates. In this case, addition of a hydrazone reducing agent such as sodium cyanoborohydride would result in a stable amide bond. Thus, the excellent hydrazide and maleimide reactivity of PMCA and BMCA would be attractive. Additionally, hydrazide reactivity is different from amine reactivity due to the lower pKa of hydrazides. Non-reversible conjugation of the crosslinkers described here to hydrazides in the presence of primary amines could be achieved by control of reaction pH and the use of a hydrazone reducing agent.

In summary, the thiol-reactive crosslinkers described in this work could prove to be useful new tools for preparation of bioconjugates with specific coupling/de-coupling properties. Hydrazide functionality is readily incorporated into synthetic systems, while thiol functionality is readily contained in biological components targeted for conjugation and subsequent release. These crosslinkers could be used for conjugation and subsequent triggered release as described here, for non-reversible conjugation by simply changing the reaction conditions, or serve as a starting point for design of more advanced crosslinkers with specific performance features.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Andrew Higginbotham and Dr. Mark Kerr for helpful discussion regarding organic procedures. Partial support from NIH grant EB000894 is gratefully acknowledged.

Footnotes

SUPPORTING INFORMATION AVAILABLE. Experimental details regarding pHPMA synthesis, synthesis of methacryloyl glycylglycine TNBSA assay standards, reaction of crosslinkers with ethyl carbazate and spectral properties of hydrazones formed with crosslinkers and ethyl carbazate are described. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Monfardini C, Veronese FM. Stabilization of substances in circulation. Bioconjug Chem. 1998;9:418–50. doi: 10.1021/bc970184f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hermanson GT. Bioconjugate techniques. Academic Press; San Diego: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brinkley M. A brief survey of methods for preparing protein conjugates with dyes, haptens, and cross-linking reagents. Bioconjugate Chem. 1992;3:2–13. doi: 10.1021/bc00013a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mattson G, Conklin E, Desai S, Nielander G, Savage MD, Morgensen S. A practical approach to crosslinking. Mol Biol Rep. 1993;17:167–83. doi: 10.1007/BF00986726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Asokan A, Cho MJ. Exploitation of intracellular pH gradients in the cellular delivery of macromolecules. J Pharm Sci. 2002;91:903–13. doi: 10.1002/jps.10095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wattiaux R, Laurent N, Wattiaux-De Coninck S, Jadot M. Endosomes, lysosomes: their implication in gene transfer. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2000;41:201–8. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(99)00066-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Satchi R, Connors TA, Duncan R. PDEPT: polymer-directed enzyme prodrug therapy. I. HPMA copolymer-cathepsin B and PK1 as a model combination. Br J Cancer. 2001;85:1070–6. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2001.2026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Duncan R, Gac-Breton S, Keane R, Musila R, Sat YN, Satchi R, Searle F. Polymer-drug conjugates, PDEPT and PELT: basic principles for design and transfer from the laboratory to clinic. J Controlled Release. 2001;74:135–46. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(01)00328-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kopecek J, Kopeckova P, Minko T, Lu ZR, Peterson CM. Water soluble polymers in tumor targeted delivery. J Controlled Release. 2001;74:147–158. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(01)00330-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Putnam D, Kopecek J. Polymer conjugates with anticancer activity. Biopolymers II. 1995;122:55–123. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Seymour L, Ferry D, Kerr D, Rea D, Whitlock M, Poyner R, Boivin C, Hesslewood S, Twelves C, Blackie R, Schatzlein A, Jodrell D, Bissett D, Calvert H, Lind M, Robbins A, Burtles S, Duncan R, Cassidy J. Phase II studies of polymer-doxorubicin (PK1, FCE28068) in the treatment of breast, lung and colorectal cancer. Int J Oncol. 2009;34:1629–1636. doi: 10.3892/ijo_00000293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Doronina S, Toki B, Torgov M, Mendelsohn B, Cerveny C, Chace D, DeBlanc R, Gearing R, Bovee T, Siegall C, Francisco J, Wahl A, Meyer D, Senter P. Development of potent monoclonal antibody auristatin conjugates for cancer therapy. Nat Biotechnol. 2003:778–784. doi: 10.1038/nbt832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Doronina S, Bovee T, Meyer D, Miyamoto J, Anderson M, Morris-Tilden C, Senter P. Novel peptide linkers for highly potent antibody-auristatin conjugate. Bioconjugate Chem. 2008;19:1960–1963. doi: 10.1021/bc800289a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gillies ER, Goodwin AP, Frechet JMJ. Acetals as pH-sensitive linkages for drug delivery. Bioconjugate Chem. 2004;15:1254–1263. doi: 10.1021/bc049853x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.West KR, Otto S. Reversible covalent chemistry in drug delivery. Curr Drug Discov Technol. 2005;2:123–60. doi: 10.2174/1570163054866882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kratz F, Beyer U, Schutte MT. Drug-polymer conjugates containing acid-cleavable bonds. Crit Rev Ther Drug. 1999;16:245–288. doi: 10.1615/critrevtherdrugcarriersyst.v16.i3.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.D’Souza AJ, Topp EM. Release from polymeric prodrugs: linkages and their degradation. J Pharm Sci. 2004;93:1962–79. doi: 10.1002/jps.20096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Flenniken ML, Liepold LO, Crowley BE, Willits DA, Young MJ, Douglas T. Selective attachment and release of a chemotherapeutic agent from the interior of a protein cage architecture. Chem Commun. 2005:447–449. doi: 10.1039/b413435d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Etrych T, Chytil P, Jelinkova M, Rihova B, Ulbrich K. Synthesis of HPMA copolymers containing doxorubicin bound via a hydrazone linkage. Effect of spacer on drug release and in vitro cytotoxicity. Macromol Biosci. 2002;2:43–52. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Etrych T, Jelinkova M, Rihova B, Ulbrich K. New HPMA copolymers containing doxorubicin bound via pH-sensitive linkage: synthesis and preliminary in vitro and in vivo biological properties. J Controlled Release. 2001;73:89–102. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(01)00281-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.King HD, Dubowchik GM, Mastalerz H, Willner D, Hofstead SJ, Firestone RA, Lasch SJ, Trail PA. Monoclonal antibody conjugates of doxorubicin prepared with branched peptide linkers: inhibition of aggregation by methoxytriethyleneglycol chains. J Med Chem. 2002;45:4336–43. doi: 10.1021/jm020149g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bae Y, Fukushima S, Harada A, Kataoka K. Design of environment-sensitive supramolecular assemblies for intracellular drug delivery: Polymeric micelles that are responsive to intracellular pH change. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2003;42:4640–4643. doi: 10.1002/anie.200250653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rodrigues PCA, Beyer U, Schumacher P, Roth T, Fiebig HH, Unger C, Messori L, Orioli P, Paper DH, Mulhaupt R, Kratz F. Acid-sensitive polyethylene glycol conjugates of doxorubicin: Preparation, in vitro efficacy and intracellular distribution. Bioorg Med Chem. 1999;7:2517–2524. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0896(99)00209-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Padilla De Jesus OL, Ihre HR, Gagne L, Frechet JM, Szoka FC., Jr Polyester dendritic systems for drug delivery applications: in vitro and in vivo evaluation. Bioconjugate Chem. 2002;13:453–61. doi: 10.1021/bc010103m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.King TP, Zhao SW, Lam T. Preparation of protein conjugates via intermolecular hydrazone linkage. Biochemistry. 1986;25:5774–5779. doi: 10.1021/bi00367a064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kaneko T, Willner D, Monkovic I, Knipe JO, Braslawsky GR, Greenfield RS, Vyas DM. New hydrazone derivatives of adriamycin and their immunoconjugates - a correlation between acid stability and cytotoxicity. Bioconjugate Chem. 1991;2:133–141. doi: 10.1021/bc00009a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kopecek J, Kopeckova P, Minko T, Lu Z. HPMA copolymer-anticancer drug conjugates: design, activity, and mechanism of action. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2000;50:61–81. doi: 10.1016/s0939-6411(00)00075-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Omura K, Swern D. Oxidation of alcohols by activated dimethyl-sulfoxide - preparative, steric and mechanistic Study. Tetrahedron. 1978;34:1651–1660. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Christie R, Tadiello C, Chamberlain L, Grainger D. Optical properties and application of a reactive and bioreducible thiol-containing tetramethylrhodamine dimer. Bioconjugate Chem. 2009;20:476–480. doi: 10.1021/bc800367e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kopecek J. Reactive copolymers of N-(2-Hydroxypropyl)Methacrylamide with N-methacryloylated derivatives of L-Leucine and L-Phenylalanine. 1 Preparation, characterization, and reactions with diamines. Macromol Chem Phys. 1977;178:2169–2183. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Drobnik J, Kopecek J, Labsky J, Rejmanova P, Exner J, Saudek V, Kalal J. Enzymatic cleavage of side-chains of synthetic water-soluble polymers. Macrom Chem Phys. 1976;177:2833–2848. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ulbrich K, Subr V, Strohalm J, Plocova D, Jelinkova M, Rihova B. Polymeric drugs based on conjugates of synthetic and natural macromolecules I. Synthesis and physico-chemical characterisation. J Controlled Release. 2000;64:63–79. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(99)00141-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ishikawa E, Imagawa M, Hashida S, Yoshitake S, Hamaguchi Y, Ueno T. Enzyme-labelling of antibodies and their fragments for enzyme-immunoassay and immunohistochemical staining. J Immunoassay. 1983:209–327. doi: 10.1080/15321818308057011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Getz EB, Xiao M, Chakrabarty T, Cooke R, Selvin PR. A comparison between the sulfhydryl reductants tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine and dithiothreitol for use in protein biochemistry. Anal Biochem. 1999;273:73–80. doi: 10.1006/abio.1999.4203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shafer DE, Inman JK, Lees A. Reaction of tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP) with maleimide and alpha-haloacyl groups: Anomalous elution of TCEP by gel filtration. Anal Biochem. 2000;282:161–164. doi: 10.1006/abio.2000.4609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Maeda H, Wu J, Sawa T, Matsumura Y, Hori K. Tumor vascular permeability and the EPR effect in macromolecular therapeutics: a review. J Controlled Release. 2000;65:271–284. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(99)00248-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kalia J, Raines R. Hydrolytic stability of hydrazones and oximes. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2008;47:7523–7526. doi: 10.1002/anie.200802651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cordes EH, Jencks WP. Mechanism of hydrolysis of Schiff bases derived from aliphatic amines. J Am Chem Soc. 1963;85:2843–2848. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Harnsberger HF, Cochran EL, Szmant HH. The basicity of hydrazones. J Am Chem Soc. 1955;77:5048–5050. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nguyen R, Huc I. Optimizing the reversibility of hydrazone formation for dynamic combinatorial chemistry. Chem Commun. 2003:942–943. doi: 10.1039/b211645f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kale A, Torchilin V. Design, synthesis, and characterization of pH-sensitive PEG-PE conjugates for stimuli-sensitive pharmaceutical nanocarriers: The effect of substitutes at the hydrazone linkage on the pH stability of PEG-PE conjugates. Bioconjugate Chem. 2007;18:363–370. doi: 10.1021/bc060228x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Galande AK, Weissleder R, Tung CH. Fluorescence probe with a pH-sensitive trigger. Bioconjugate Chem. 2006;17:255–257. doi: 10.1021/bc050330e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.