Abstract

Objectives

Advances in reconstruction and conservative surgery and the importance of quality of life (QOL) encouraged this reevaluation of surgery-based treatments for oropharyngeal cancer. We tried to compare treatment outcome and QOL after surgery-based versus radiation-based treatment in oropharyngeal cancer.

Methods

The 133 eligible patients were divided into surgery-based and radiotherapy (RT)-based treatment groups. Medical records were reviewed, and EORTC QLQ-C30 and HN65 questionnaires were completed for survivors. Three-year overall survivals, disease-free survivals, locoregional control rates, and QOL scores were compared between the two groups.

Results

Demographic data and overall stages were not significantly different between the two groups, and all survival rates were non-significantly different, either. The scores for most QOL items were equivalent, however, for a few items, scores were significantly better in surgery-based group.

Conclusion

The surgery-based group achieved equivalent treatment outcomes and slightly better QOL scores than the RT-based group. The results of this study suggest that surgery could still be considered as a first-line therapy for oropharyngeal cancer.

Keywords: Treatment outcome, Quality of life, Oropharyngeal cancer, Surgery, Radiation

INTRODUCTION

The latest National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) practical guideline recommends that most oropharyngeal cancers be treated by concurrent chemoradiotherapy (CCRT), rather than by surgery with or without adjuvant therapy. In fact, surgery is viewed as the equivalent of definite radiotherapy (RT) for only T1-2, N0-1 cancers. This guideline implies that the treatment outcomes of RT and CCRT are better than or equivalent to that of surgery with or without adjuvant RT, which is the traditional treatment protocol.

However, head and neck surgeons have been faced with two major changes in the clinical environment. One is the health-related quality of life (QOL) issue. Patients and surgeons now acknowledge that QOL is one of the important parameters when evaluating treatment outcome in head and neck cancer. The oropharynx is a cardinal region for swallowing and speaking, and accordingly, QOL should be a key consideration in the treatment of oropharyngeal cancer. The second major change involves the development of more conservative surgical techniques and of functional reconstructions. Traditionally surgery for oropharyngeal cancer often required highly invasive approaches, such as, mandibular swing or mandibular lingual release, to secure a wide operation field. However, several transoral approaches have been introduced and many reports have demonstrated that transoral techniques are associated with less morbidity and are oncologically safe. As for reconstruction, along with three-dimensional fitting, evolved flaps such as the sensate flap, the freestyle perforator flap have been devised that offer considerable functional and cosmetic improvement. Consequently, oropharyngeal surgery is now associated with fewer morbidities. Although a small number of studies have compared surgery-based and RT-based treatments, few have simultaneously compared the treatment outcomes and QOL. In addition, since intraoral procedures are generally conducted when operating oropharyngeal cancers at our institution, we suspected that patients treated with a surgery-based modality might have achieved better QOLs than those treated with a RT-based method.

In this study, we compared the treatment outcomes and the health-related QOLs of oropharyngeal cancer patients treated by surgery-based versus RT-based modalities. In addition, we evaluated the adequacy of surgery-based treatment as a first-line therapy for oropharyngeal cancer.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

From 1995 to 2007, all 228 patients who were diagnosed with oropharyngeal cancer in the Department of Otorhinolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery at Samsung Medical Center were enrolled. Of these 228 patients, 95 were excluded due to double or multiple primary cancers, referral after any curative-intent treatment, a proven pathology other than squamous cell carcinoma, or an incomplete medical record. The final number of eligible patients was 133.

These 133 patients were allocated to one of two groups: a surgery-based treatment group or a RT-based treatment group. Treatment modalities for all patients had been discussed previously by the tumor board. The surgery-based group included the patients who underwent surgery only, surgery with adjuvant RT, or surgery with adjuvant CCRT. The RT-based group consisted of those who underwent RT only or CCRT. At our institution, other treatment protocols, such as, induction chemotherapy followed by surgery or CCRT were not used. The radiation dose of the postoperative setting was usually not more than 6,000 cGy, while the radiation dose in the RT-based treatment protocol was usually about 7,000 cGy. The most commonly used chemotherapeutic agents were cisplatin with or without docetaxel in both treatment groups.

Medical records were retrospectively reviewed and several variables, including age, gender, primary tumor site, and TNM stage were compared between the two study groups. The Mann-Whitney test was used for age and RT dose comparison, and the chi-square test was used for other variables.

Treatment outcomes

Kaplan-Meier survival analysis was performed in each group. First, the three-year overall survival rates (OSR), disease-free survival rates (DFSR), locoregional control rates (LRCR) and their respective standard errors were determined using survival Tables. Next, Z values of the standard normal distribution were calculated with the pertinent survival rates and standard errors. Final P-values for testing the difference of treatment outcomes between the two groups were determined based on Z values. This whole analysis was repeated based on T classification (T1, 2 vs. T3, 4). Kaplan-Meier survival curves were also drawn.

Quality of life

QOL questionnaires were completed by telephone interview. The interviewers were doctors in our department who had been specifically trained for questionnaire. To eliminate bias, the interviewers were not provided with patients' information, aside from their telephone numbers. This QOL survey and the whole study design were approved by our institutional review board.

Thirty-seven patients had expired at the time of the survey, 13 could not be contacted, and two patients refused the survey, and thus, 81 patients were analyzed for QOL.

The questionnaires used in this study were the Korean version of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire (EORTC QLQ) validated by Yun et al. (1). The EORTC QLQ is composed of 30 core questions (C30) and many other cancer-specific modules. The head and neck cancer module containing 35 questions (HN35) was used with C30 in this study after obtaining permission from EORTC. The EORTC QLQ-C30 contains 15 items including one global health status/QOL, five functional scales, and nine symptom scales. In terms of global health status/QOL and functional scales, the greater the score, the better the status or function is, whereas the converse applies to the symptom scales. The EORTC QLQ-HN35 contains 18 symptom scale items. Therefore, the greater the score, the more severe the symptoms are in the head and neck region. All scores of QLQ-C30 and QLQ-HN35 were linear-transformed using the EORTC scoring manual to fit the range 0-100. To eliminate the possible confounding effect of T classification, which was the only variable that was significantly different between the two groups, patients were categorized into T1, 2 and T3, 4 and analyzed by Spearman's partial correlation test. All statistical analyses were carried out by the professional statistical support team at our institution.

RESULTS

Demographics and characteristics of the two treatment groups

There were 104 men and 29 women (M:F ratio 3.6:1) with a mean age of 61.5 years (range, 15 to 84 years) in the study sample. The follow-up period ranged from 1 to 155 months (average of 43.7 months), and the number of patients allocated to the surgery-based and RT-based groups were 66 and 67, respectively.

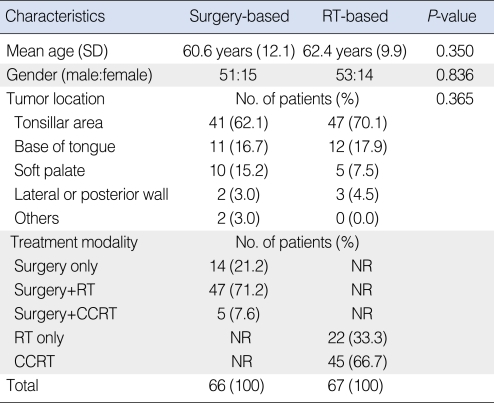

The characteristics of each treatment group are listed in Tables 1 and 2. Age, gender, and primary tumor location were not significantly different between the two groups. In the surgery-based group, 40 operations were performed intraorally including five laser resections. In 26 cases, operations were conducted using a more invasive approach, such as, a pull-through, mandibular swing, and mandibular lingual release.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the surgery-based and RT-based treatment groups

*Patients who underwent surgery only were excluded.

RT: radiotherapy; SD: standard deviation; CCRT: concurrent chemoradiotherapy; NR: no relevant data.

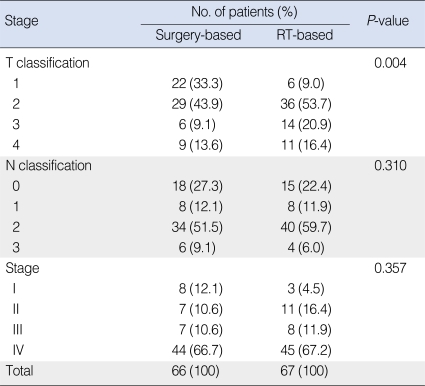

Table 2.

Stage characteristics of the surgery-based and RT-based treatment groups

RT: radiotherapy.

T classification was significantly lower in the surgery-based group, but overall TNM staging was not different between the two groups because many patients were N2 or N3, consequently, fell into stage IV.

The mean RT dose in the RT-based group was 6,637 cGy ranging from 1,800 to 7,200, while the mean RT dose of surgery-based group was mean 4,632 cGy, ranging from 0 to 7,000. After the exclusion of patients who had undergone surgery only, the mean RT dosage of surgery-based group was 5,878 cGy, and the difference of RT dose between the two groups was significantly different (P<0.0001).

Chemotherapeutic agents were also compaired. Cisplatin with or without decetaxel comprise 80% of surgery-based group and 77.8% of RT-based group, and it was not different statistically (P=0.443).

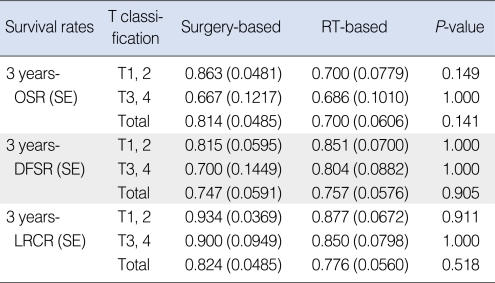

Treatment outcomes

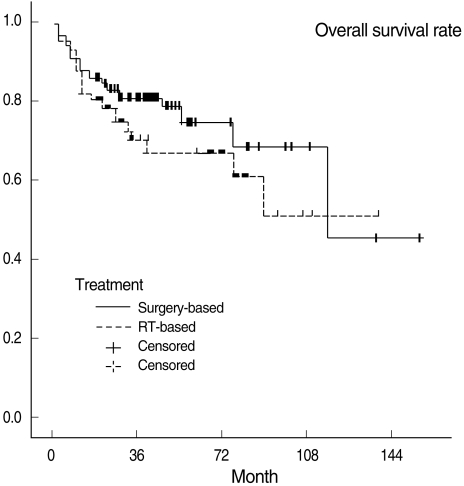

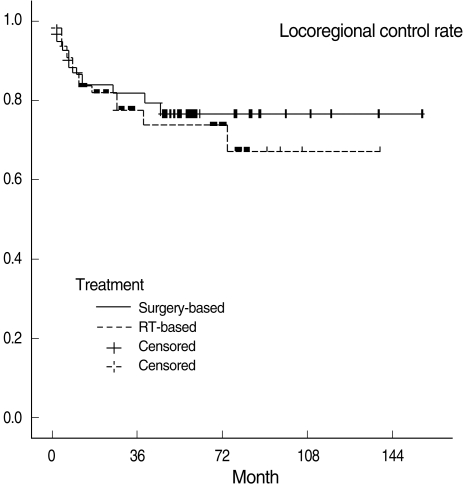

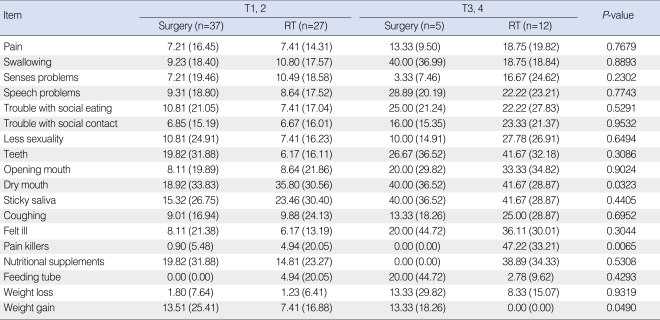

Three-year OSRs, DFSRs, and LRCRs are shown in Table 3. Survival rates were not significantly different between the two treatment groups. All survival rates which were categorized into T1, 2 and T3, 4 were also not statistically different. Kaplan-Meier survival curves are shown in Figs. 1 to 3.

Table 3.

Treatment outcomes in the surgery-based and RT-based treatment groups

RT: radiotherapy; OSR: overall survival rate; SE: standard error; DFSR: disease-free survival rate; LRCR: locoregional control rate.

Fig. 1.

Overall survival curves in the surgery-based and radiotheraapy (RT)-based treatment groups.

Fig. 3.

Locoregional control curves in the surgery-based and radiotherapy (RT)-based treatment groups.

Quality of life

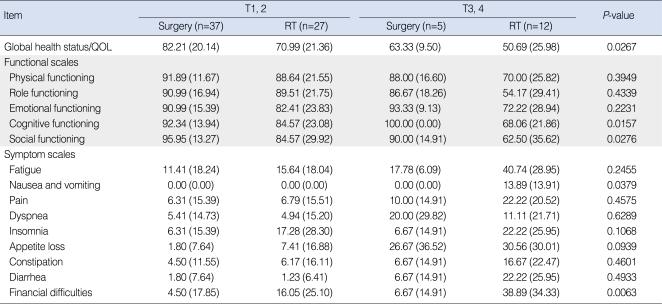

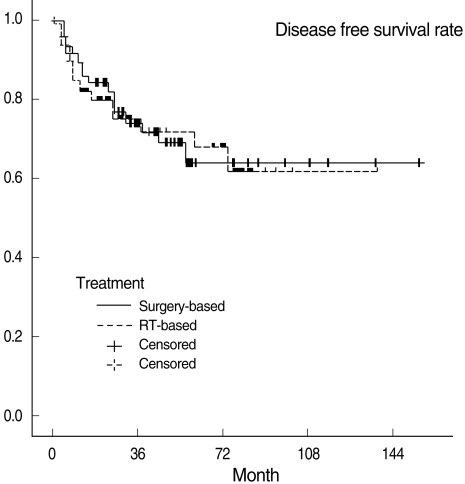

The number of patients who completed the QOL survey in the surgery-based and RT-based groups were 42 and 39, respectively. The EORTC QLQ-C30 scores of two treatment groups are shown in Table 4. The surgery-based group had a better average QOL score for five items, namely, global health status/QOL, cognitive functioning, social functioning, nausea and vomiting, and financial difficulties, whereas the RT-based group did not have a better score than the surgery-based group for any QOL item. The average scores of the other 10 items were not significantly different between the two groups.

Table 4.

EORTC QLQ-C30 scores in the surgery-based and RT-based treatment groups

Values are presented as mean (standard deviation).

EORTC QLQ: European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life; RT: radiotherapy.

Table 5 shows the results from the analysis for EORTC QLQ-HN35. Likewise in QLQ-C30, no items showed an advantage for the RT-based group. Three items, that is, dry mouth, pain killers, and weight gain, were superior in the surgery-based group. The majority of QLQ-HN35 items were not significantly different between the two groups.

Table 5.

EORTC QLQ-HN35 scores in the surgery-based and RT-based treatment groups

Values are presented as mean (standard deviation).

EORTC QLQ: European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life; RT: radiotherapy.

DISCUSSION

Treatment outcomes

According to the NCCN guideline, CCRT should be considered the first-line treatment for the majority of oropharyngeal cancers, but evidence supporting this guideline is questionable. In a review of recent reports, five-year survival rates in oropharyngeal cancer ranged from 45 to 70% for surgery followed by RT (2-5), whereas for CCRT, the majority of studies conducted in patients with advanced stage disease found three-year survival rates in the range 37 to 51% (6-8). Although patients in the CCRT studies appeared to have higher stage disease than in the surgery followed by RT studies, treatment outcomes of CCRT are far from satisfactory.

Comparative reports on surgery-based and RT-based treatment of oropharyngeal cancer are scarce. Soo et al. (9) reported no significant three-years DFSR difference between surgery with adjuvant RT and CCRT (50 vs. 40%, respectively) in 119 patients with stage III/IV head and neck cancers. This study was the first randomized controlled study to focus on the results of CCRT in overall head and neck cancer, but it included only 25 patients with oropharyngeal cancer (surgery+RT 12 and CCRT 13). Moreover, organ preservation was possible in only 24% of patients (6 out of 25), which shows that the oropharynx is a less satisfactory site for organ preservation than the larynx, which was preserved in 71.4% of patients (10 out of 14). Lanza et al. (8) compared the results of surgery with RT and neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by RT in 115 T3-4 patients. The three-years OSRs of the respective treatment groups were 82 and 49%, showing that surgery-based therapy appeared to be the better treatment option. However, in their study, stage stratification was not conducted and their RT was not based on a standard "concurrent" protocol.

In our study, the choice of treatment modalities may have been subject to physicians' bias. However, all factors considered to be able to influence prognosis were evaluated and no factor except T classification turned out to be significantly different in the surgery-based and RT-based treatment groups. Furthermore, the difference in T classification is considered to have had little impact on our survival rates, because overall stages were not different between the two groups. Actually subgroup analysis based on T classification (T1, 2 vs. T3, 4) also revealed no difference in all survival rates between the two groups (Table 3).

The present study shows that three-years DFSRs in the surgery-based and RT-based treatment groups were 74.7% and 75.7%, respectively. Furthermore, our review of the literature showed that CCRT appears to be slightly inferior to surgery with adjuvant radiotherapy in terms of treatment outcomes. Our results and review of literature lead us to believe that present CCRT is likely to have an equal or only slightly worse result than surgery plus RT. Of course, a large-scale prospective randomized trial is required to prove the comparative oncologic results of these two treatment approaches.

Quality of life

QOL is a complex concept that reflects several aspects of life, and an individual's perception of overall well-being with regard to disease and treatment-related symptoms is specifically called "health-related QOL" (10). However, many reports use the two terms interchangeably.

Several QOL assessment tools have been devised. According to a structured review of QOL in head and neck cancer (11), the most frequently used questionnaires are the EORTC (12), the University of Washington - Quality Of Life (UW-QOL), and the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy (FACT) questionnaires. Of these, the EORTC questionnaire is most commonly used, and has been validated in Korean-speaking sample (1). Therefore, it was selected for our study. The EORTC questionnaire is an integrated system for assessing QOL in a wide range of cancer patients. It is composed of core questions (QLQ-C30) and supplementary tumor-specific questionnaire modules: for lung cancer (QLQ-LC13), breast cancer (QLQ-BR23), head and neck cancer (QLQ-HN35), esophageal cancer (QLQ-OES18), ovarian cancer (QLQ-OV28), and so on. In the present study, we used the EORTC QLQ-C30 and EORTC QLQ-HN35.

From the 1990's, QOL has been increasingly recognized as an important outcome parameter in head and neck cancer, and literally hundreds of papers have been published on that issue. However, in the case of oropharyngeal cancer, generally accepted conclusions are rare, because only dozens of studies have been conducted, and these studies addressed their specific topics, applied different enrollment criteria and used different methods of analysis.

Many physicians believe that oropharyngeal cancer surgery is too invasive to be compatible with a good or even a tolerable QOL. However, we resist this presumption. Current advances in reconstruction allowed the oropharyngeal cancer surgery to become less destructive. Recent studies on free-flap reconstruction have shown the acceptable QOL and functional status in most cases, even after extensive ablative surgery (13-15). Although these were longitudinal, cohort studies without control groups, they at least showed that current surgical therapies offered good treatment options with acceptable QOL. Our study result also supports this conclusion.

At our institution, surgical extent tends to be conservative, nearly all T1 and most T2 primary tumors are resected intraorally, and even for advanced cases, mandibulotomy and segmental mandibulectomy are avoided if possible. Three-dimensional reconstructions are carried out in the majority of advanced cases. We believe that this conservative surgical approach is likely to achieve better QOL results without disturbing oncologic outcome.

As for the results of the EORTC QLQ-C30 questionnaire, cognitive functioning and social functioning were found to be better in the surgery-based group. Although its relevance is questionable and its mechanism is unclear, accumulating evidence indicates an association between chemotherapy and cognitive deterioration (16-19). The better social functioning score of the surgery-based group is believed to reflect the shorter duration of therapy and fewer sequelae as compared with the RT-based group. Our conspicuous finding was that patients in the surgery group suffered less from financial difficulties than those in the RT-based group. We believe that this result is due to the national medical insurance system in Korea, which charges extremely low fees for surgery. Nausea and vomiting is a common complication of chemotherapy, thus poorer results of this item in the RT-based group can be easily appreciated. Although the majority of patients (78.8%) in the surgery-based group received radiation or chemoradiation postoperatively, radiation doses in the surgery group were significantly lower than those in the RT-based group (5,878 cGy vs. 6,637 cGy). We think that this difference in radiation dose might contribute to make a difference in several QOL items, since the analysis after "compensation" of radiation doses revealed that no items of the QLQ-C30 were different. This analysis result is somewhat confusing. It does not mean that the QOL results are truly identical but implies that if the radiation doses had been the same, QOL results would not have differed between the two groups. But in an actual clinical setting, the radiation dose of the two treatment groups will be different.

According to our EORTC QLQ-HN35 survey data, most items revealed no significant differences between the two groups, although members of the RT group had more problems with a dry mouth, difficulties in weight gain, and were more dependent on pain killers. A dry mouth appears to be an invariant RT-associated problem. However, difficulty in weight gain and greater pain found in the RT-based group have not been found previously, and we ascribe this apparent discrepancy to our less destructive surgery. Analysis after correction of radiation dose was conducted again, and this time, differences in pain killers (P=0.0021), weight gain (P=0.0198) items were still significant.

The interpretation of QOL data is not straightforward, and some potential problems should be borne in mind. First, many factors such as age, sex, marital status, comorbidity, malnutrition, tumor location, stage, treatment modality, and time of evaluation, etc. are known to affect QOL in patients with head and neck cancer. In addition, many of these factors have been inconsistently associated with QOL. For example, van der Schroeff et al. (20) found that age had no independent impact on QOL when they compared QOL in 24 older (≥70 years) and 33 younger (45-60 years) patients, whereas Hammerlid et al. (21) found that older patients scored significantly better for emotional and social functioning than patients of <65, but significantly worse for physical functioning and for various symptoms measures. Hence, potential confounders have to be well controlled. In our study, T classification in the surgery-based group turned out to be significantly lower than in the RT-based group. We supposed that it might affect QOL results, thus, this was compensated by subgroup analysis based on T classification and using Spearman's partial correlation analysis.

The second problem is that QOL scores change with time. Many studies have found that QOL deteriorates during treatment, recovers to some extent during the first year post-treatment, and then stabilizes (14, 22-24). Besides, QOL may be compromised before treatment (14). In this study, QOL was evaluated just once in a cross-sectional fashion, and thus, we cannot rule out the possibility that QOLs differed between the two groups before the treatment, and this is our major drawback. Accordingly, a longitudinal study is required to further investigate QOL issues.

Regarding previous comparisons of surgery-based and RT-based treatments of oropharyngeal cancer from the QOL point of view, many findings are inconsistent. Mowry et al. (25) failed to find any difference between 17 and 18 patients of stages II-IV who underwent surgery plus RT or CCRT, respectively. Pourel et al. (26) administered EORTC QLQ-C30 and HN35 questionnaires to 113 patients, and found that QOLs were similar regardless of initial treatment modality (brachytherapy, external beam RT, or surgery plus RT). Boscolo-Rizzo et al. (10) compared QOL in 57 patients who had T3-4 oropharyngeal cancer after surgery plus postoperative RT (26 patients) versus CCRT (31 patients) using EORTC QLQ-C30 & QLQ-HN35. Physical and social functioning were found to be significantly better in CCRT group. CCRT group was advantageous in symptom items such as fatigue, pain, and swallowing, trouble with social eating, trouble with social contact. However CCRT was unfavorable in teeth, open mouth, dry mouth, and sticky saliva items. Tschudi et al. (27) investigated QOL after three different treatment modalities, namely, surgery alone, RT alone, and surgery plus RT in 31, 19, and 49 patients, respectively. EORTC QLQ-C30 revealed no significant differences between the three treatment groups, although non-irradiated patients had significantly fewer problems associated with swallowing, social eating, social contact, dry mouth, sticky saliva, and mouth opening, regardless of the primary treatment modality. Allal et al. (28) assessed QOL after radical surgery with postoperative RT and an RT boost with or without chemotherapy in 60 patients. They used the Performance Status Scale for Head and Neck Cancer (PSSHN) questionnaire which comprises eating in public, understandability of speech, normalcy of diet, and the EORTC QLQ-C30 questionnaire. No significant differences were observed for T1-2 tumors, but patients with T3-4 tumors showed highly significant differences that favored the RT group for all three subscales. EORTC QLQ-C30 findings revealed that T1-2 patients in the surgery group had better social function than those in the RT group. In patients with T3-4 tumors, patients in the surgery group suffered from more severe pain than those in the RT group.

In summary, treatment outcomes were found to be equal in the surgery-based and RT-based groups, and patients in the surgery-based group achieved better QOL scores for a few variables. Consequently, we cautiously infer that surgery-based treatment is worth reconsidering as a first-line therapy as well as CCRT for the treatment of oropharyngeal cancer.

Fig. 2.

Disease-free survival curves in the surgery-based and radiotherapy (RT)-based treatment groups.

Footnotes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

- 1.Yun YH, Park YS, Lee ES, Bang SM, Heo DS, Park SY, et al. Validation of the Korean version of the EORTC QLQ-C30. Qual Life Res. 2004 May;13(4):863–868. doi: 10.1023/B:QURE.0000021692.81214.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Makitie AA, Pukkila M, Laranne J, Pulkkinen J, Vuola J, Back L, et al. Oropharyngeal carcinoma and its treatment in Finland between 1995-1999: a nationwide study. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2006 Feb;263(2):139–143. doi: 10.1007/s00405-005-0975-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Parsons JT, Mendenhall WM, Stringer SP, Amdur RJ, Hinerman RW, Villaret DB, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma of the oropharynx: surgery, radiation therapy, or both. Cancer. 2002 Jun;94(11):2967–2980. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pericot J, Escriba JM, Valdes A, Biosca MJ, Monner A, Castellsague X, et al. Survival evaluation of treatment modality in squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity and oropharynx. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2000 Feb;28(1):49–55. doi: 10.1054/jcms.1999.0091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roosli C, Tschudi DC, Studer G, Braun J, Stoeckli SJ. Outcome of patients after treatment for a squamous cell carcinoma of the oropharynx. Laryngoscope. 2009 Mar;119(3):534–540. doi: 10.1002/lary.20033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Adelstein DJ. Concurrent chemoradiotherapy in the management of squamous cell cancer of the oropharynx: current standards and future directions. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2007;69(2 Suppl):S37–S39. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.04.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Calais G, Alfonsi M, Bardet E, Sire C, Germain T, Bergerot P, et al. Randomized trial of radiation therapy versus concomitant chemotherapy and radiation therapy for advanced-stage oropharynx carcinoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999 Dec;91(24):2081–2086. doi: 10.1093/jnci/91.24.2081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lanza L, Rizzi L, Durso D, Occhini A, Benazzo M, Tinelli C. Integrated treatment in locally advanced carcinoma of the oropharynx. J Surg Oncol. 2000 May;74(1):75–78. doi: 10.1002/1096-9098(200005)74:1<75::aid-jso16>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Soo KC, Tan EH, Wee J, Lim D, Tai BC, Khoo ML, et al. Surgery and adjuvant radiotherapy vs concurrent chemoradiotherapy in stage III/IV nonmetastatic squamous cell head and neck cancer: a randomised comparison. Br J Cancer. 2005 Aug;93(3):279–286. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boscolo-Rizzo P, Stellin M, Fuson R, Marchiori C, Gava A, Da Mosto MC. Long-term quality of life after treatment for locally advanced oropharyngeal carcinoma: surgery and postoperative radiotherapy versus concurrent chemoradiation. Oral Oncol. 2009 Nov;45(11):953–957. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2009.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rogers SN, Ahad SA, Murphy AP. A structured review and theme analysis of papers published on 'quality of life' in head and neck cancer: 2000-2005. Oral Oncol. 2007 Oct;43(9):843–868. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2007.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, Bullinger M, Cull A, Duez NJ, et al. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993 Mar;85(5):365–376. doi: 10.1093/jnci/85.5.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bozec A, Poissonnet G, Chamorey E, Casanova C, Vallicioni J, Demard F, et al. Free-flap head and neck reconstruction and quality of life: a 2-year prospective study. Laryngoscope. 2008 May;118(5):874–880. doi: 10.1097/MLG.0b013e3181644abd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Borggreven PA, Aaronson NK, Verdonck-de Leeuw IM, Muller MJ, Heiligers ML, Bree R, et al. Quality of life after surgical treatment for oral and oropharyngeal cancer: a prospective longitudinal assessment of patients reconstructed by a microvascular flap. Oral Oncol. 2007 Nov;43(10):1034–1042. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2006.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Friedlander P, Caruana S, Singh B, Shaha A, Kraus D, Harrison L, et al. Functional status after primary surgical therapy for squamous cell carcinoma of the base of the tongue. Head Neck. 2002 Feb;24(2):111–114. doi: 10.1002/hed.10015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vardy J, Tannock I. Cognitive function after chemotherapy in adults with solid tumours. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2007 Sep;63(3):183–202. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2007.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vardy J, Rourke S, Tannock IF. Evaluation of cognitive function associated with chemotherapy: a review of published studies and recommendations for future research. J Clin Oncol. 2007 Jun;25(17):2455–2463. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.1604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jansen CE, Miaskowski C, Dodd M, Dowling G, Kramer J. A metaanalysis of studies of the effects of cancer chemotherapy on various domains of cognitive function. Cancer. 2005 Nov;104(10):2222–2233. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Iconomou G, Mega V, Koutras A, Iconomou AV, Kalofonos HP. Prospective assessment of emotional distress, cognitive function, and quality of life in patients with cancer treated with chemotherapy. Cancer. 2004 Jul;101(2):404–411. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van der Schroeff MP, Derks W, Hordijk GJ, de Leeuw RJ. The effect of age on survival and quality of life in elderly head and neck cancer patients: a long-term prospective study. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2007 Apr;264(4):415–422. doi: 10.1007/s00405-006-0203-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hammerlid E, Bjordal K, Ahlner-Elmqvist M, Boysen M, Evensen JF, Biorklund A, et al. A prospective study of quality of life in head and neck cancer patients. Part I: at diagnosis. Laryngoscope. 2001 Apr;111(4 Pt 1):669–680. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200104000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abendstein H, Nordgren M, Boysen M, Jannert M, Silander E, Ahlner-Elmqvist M, et al. Quality of life and head and neck cancer: a 5 years prospective study. Laryngoscope. 2005 Dec;115(12):2183–2192. doi: 10.1097/01.MLG.0000181507.69620.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bjordal K, Ahlner-Elmqvist M, Hammerlid E, Boysen M, Evensen JF, Biorklund A, et al. A prospective study of quality of life in head and neck cancer patients. Part II: Longitudinal data. Laryngoscope. 2001 Aug;111(8):1440–1452. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200108000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Infante-Cossio P, Torres-Carranza E, Cayuela A, Hens-Aumente E, Pastor-Gaitan P, Gutierrez-Perez JL. Impact of treatment on quality of life for oral and oropharyngeal carcinoma. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009 Oct;38(10):1052–1058. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2009.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mowry SE, Ho A, Lotempio MM, Sadeghi A, Blackwell KE, Wang MB. Quality of life in advanced oropharyngeal carcinoma after chemoradiation versus surgery and radiation. Laryngoscope. 2006 Sep;116(9):1589–1593. doi: 10.1097/01.mlg.0000233244.18901.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pourel N, Peiffert D, Lartigau E, Desandes E, Luporsi E, Conroy T. Quality of life in long-term survivors of oropharynx carcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2002 Nov;54(3):742–751. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(02)02959-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tschudi D, Stoeckli S, Schmid S. Quality of life after different treatment modalities for carcinoma of the oropharynx. Laryngoscope. 2003 Nov;113(11):1949–1954. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200311000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Allal AS, Nicoucar K, Mach N, Dulguerov P. Quality of life in patients with oropharynx carcinomas: assessment after accelerated radiotherapy with or without chemotherapy versus radical surgery and postoperative radiotherapy. Head Neck. 2003 Oct;25(10):833–839. doi: 10.1002/hed.10302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]