Abstract

BACKGROUND AND PURPOSE

Exendin-4 (exenatide, Ex4) is a high-affinity peptide agonist at the glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor (GLP-1R), which has been approved as a treatment for type 2 diabetes. Part of the drug/hormone binding site was described in the crystal structures of both GLP-1 and Ex4 bound to the isolated N-terminal domain (NTD) of GLP-1R. However, these structures do not account for the large difference in affinity between GLP-1 and Ex4 at this isolated domain, or for the published role of the C-terminal extension of Ex4. Our aim was to clarify the pharmacology of GLP-1R in the context of these new structural data.

EXPERIMENTAL APPROACH

The affinities of GLP-1, Ex4 and various analogues were measured at human and rat GLP-1R (hGLP-1R and rGLP-1R, respectively) and various receptor variants. Molecular dynamics coupled with in silico mutagenesis were used to model and interpret the data.

KEY RESULTS

The membrane-tethered NTD of hGLP-1R displayed similar affinity for GLP-1 and Ex4 in sharp contrast to previous studies using the soluble isolated domain. The selectivity at rGLP-1R for Ex4(9–39) over Ex4(9–30) was due to Ser-32 in the ligand. While this selectivity was not observed at hGLP-1R, it was regained when Glu-68 of hGLP-1R was mutated to Asp.

CONCLUSIONS AND IMPLICATIONS

GLP-1 and Ex4 bind to the NTD of hGLP-1R with similar affinity. A hydrogen bond between Ser32 of Ex4 and Asp-68 of rGLP-1R, which is not formed with Glu-68 of hGLP-1R, is responsible for the improved affinity of Ex4 at the rat receptor.

Keywords: GLP-1, exendin-4, GPCR, diabetes, hormone, receptor, ligand

Introduction

Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) is a 30 amino acid ‘incretin’ hormone that plays a central role in post-prandial insulin release and the subsequent regulation of blood sugar levels (Baggio and Drucker, 2007). GLP-1 is released from intestinal L-cells in response to the ingestion of food, and acts at pancreatic β-cells to potentiate insulin secretion in a glucose-dependent manner (Kieffer and Habener, 1999; Drucker, 2001). It also acts to reduce blood glucose by the inhibition of gastric emptying (Wettergren et al., 1993), inhibition of glucagon secretion (Orskov et al., 1988) and reduction of food intake (Turton et al., 1996). As such, it is of great interest as a pharmaceutical target for the treatment of diabetes, with two peptides (liraglutide, albiglutide) currently in phase III clinical trials (Knudsen et al., 2001; Matthews et al., 2008) and another (exenatide) already licensed for use as an adjunct therapy (DeFronzo et al., 2005). Exenatide is the synthetic version of exendin-4 (Ex4), a 39 amino acid natural analogue of GLP-1 found in the saliva of the Gila monster (Eng et al., 1992; Goke et al., 1993). It acts as a potent agonist at the GLP-1 receptor (GLP-1R) and was developed as an anti-diabetic drug due to its much longer half-life in vivo (Taylor et al., 2002).

The receptor for GLP-1 (GLP-1R; Alexander et al., 2009) is a typical ‘family B’ G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR), a family characterized by an extracellular N-terminal domain (NTD) of 100–150 residues and a transmembrane domain (J or core domain) consisting of seven transmembrane α-helices (Mayo et al., 2003). The proposed model for agonist-induced activation of GLP-1R is via a two-step mechanism in which the C-terminal helical region of the peptide ligand binds to the NTD, while a second interaction between the N-terminal residues of the ligand and the core region of the receptor leads to receptor activation (Lopez de Maturana et al., 2003). While the details of this second interaction are still to be determined, the first interaction has been elucidated in detail via the determination of the crystal structures of the isolated NTD of human GLP-1R (hGLP-1R) bound with either GLP-1 (Underwood et al., 2010) or Ex4(9–39) (Runge et al., 2008). In common with other family B GPCRs, the NTD of hGLP-1R has an N-terminal α-helix and a short consensus repeat stabilized by three conserved disulphide bonds (Grace et al., 2007; Parthier et al., 2007; Pioszak and Xu, 2008; Pioszak et al., 2008; Runge et al., 2008).

Ex4 is 50% identical with GLP-1 with an additional nine-residue C-terminal extension and some unusual pharmacological properties that are not shared with GLP-1 itself: firstly, it can be truncated at its N-terminus by up to eight residues without significant loss of affinity at the rat GLP-1R (rGLP-1R) (MontroseRafizadeh et al., 1997); secondly, it can maintain high affinity for the isolated NTD of the GLP-1R (Lopez de Maturana et al., 2003). In previous studies using rGLP-1R, we demonstrated that the nine-residue C-terminal extension of Ex4, which is absent in GLP-1, enhanced the peptide's affinity via an interaction with the NTD of the receptor (Al-Sabah and Donnelly, 2003a; Lopez de Maturana et al., 2003). We suggested that this extra ‘Ex’ interaction was the reason for the higher affinity of Ex4 over GLP-1 for the NTD and also the reason why Ex4, but not GLP-1, could be truncated at its N-terminus without significant loss of affinity at rGLP-1R. As the C-terminal region of the peptide had been shown via NMR to form a unique fold called a ‘Trp-cage’ (Neidigh et al., 2001), we had speculated (although not demonstrated) that this structural motif may be the basis for the ‘Ex’ interaction (Al-Sabah and Donnelly, 2003a).

A comparison of the crystal structures of the isolated NTD of hGLP-1R bound with either GLP-1 or Ex4(9–39) (Runge et al., 2008; Underwood et al., 2010) has shown that both peptides share a remarkably similar binding mode, despite the large difference in affinity displayed by these peptides at this isolated domain. Furthermore, the structure of Ex4(9–39) bound to the isolated NTD showed no Trp-cage motif and very limited interaction between the nine-residue C-terminal extension and the receptor. Moreover, a combination of pharmacological and biophysical approaches demonstrated that the removal of the C-terminal extension of Ex4 had no effect upon binding to hGLP-1R (Runge et al., 2007). Given these apparently contradictory outcomes, we have carried out a detailed pharmacological study of the role of the NTD of GLP-1R in binding GLP-1, Ex4 and Ex4(9–39). Using modified and truncated receptors and ligands, we describe a model for the interaction of the peptides with the receptor that is consistent with the available structural data, but also accounts for the observed pharmacology.

Methods

Constructs

The pcDNA3 vector (Invitrogen, Paisley, UK) containing the full-length rGLP-1R cDNA (Lopez de Maturana and Donnelly, 2002), and pcDNA5-FRT (Invitrogen) containing the cDNA encoding the full-length hGLP-1R (gift from AstraZeneca, Macclesfield, Cheshire, UK), were used to express the full-length receptors. The cDNA encoding amino acids Met1-Asn177 (NTD, including signal sequence, and first transmembrane helix of the rGLP-1R followed by a stop codon, named rNT-TM1) was synthesized by PCR, using the pcDNA3 vector containing the full-length rGLP-1R cDNA as a template. The forward and reverse oligonucleotides incorporated the HindIII and XhoI recognition sites, respectively, to facilitate insertion into the pcDNA3 expression vector. The analogous hGLP-1R construct was synthesized by PCR amplification of the cDNA encoding the equivalent region of the human receptor and inserted into the pcDNA3 vector. All other mutated full-length receptors were generated using QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA, USA), and confirmed by DNA sequencing. These constructs were used to express the wild-type, truncated and mutant GLP-1Rs in human embryonic kidney (HEK)-293 cells. The soluble NTD of rGLP-1R (rNTD) was expressed in Escherichia coli from a construct containing the cDNA encoding residues A21-E127, followed by a stop codon, inserted via the BamHI and HindIII sites of the plasmid pQE-30 (Qiagen Ltd, Crawley, UK) as described previously (Lopez de Maturana et al., 2003).

Protein expression and cell culture

The soluble rNTD was expressed in E. coli, purified and refolded exactly as we have described previously (Lopez de Maturana et al., 2003). The HEK-293 cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's Medium (Sigma, Poole, UK) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (Lonza Wokingham Ltd, Wokingham, UK), 2 mM l-glutamine, 100 U·mL−1 penicillin and 100 µg·mL−1 streptomycin (Invitrogen). Cells were transfected with plasmid containing the cDNA encoding the receptors, using the SuperFect Transfection Reagent (Qiagen Ltd), and stable clones were selected as described previously (Al-Sabah and Donnelly, 2003b).

Peptides

GLP-1(7-36)amide (called GLP-1 throughout), Ex4 and Ex4(9–39) were purchased from Bachem (Saffron Walden, Essex, UK). Ser32–Ex4(9–39), Ser33–Ex4(9–39) and Ex4(9–30) were custom synthesized by Genosphere Biotechnologies (Paris, France). The radioligand [125I]-exendin(9–39) was from PerkinElmer Life and Analytical Sciences (Waltham, MA, USA).

Radioligand binding using HEK-293 membranes

HEK-293 cells, cultured to confluence on five 160 cm2 Petri dishes (pre-coated with poly-d-lysine), were washed with PBS, followed by the addition of 15 mL of ice-cold sterile double distilled water to induce cell lysis. Following 5 min incubation on ice, the ruptured cells were thoroughly washed with ice-cold PBS before being scraped from the plates and pelleted by centrifugation in a bench-top centrifuge (13 000× g for 30 min). The crude membrane pellet was resuspended in 1 mL membrane binding solution [MBS; 25 mM HEPES (pH 7.4), 2.5 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, 50 mg·L−1 bacitracin) and forced through a 23G needle; 0.1 mL aliquots were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −70°C. Membranes were slowly thawed on ice before being diluted to a concentration that gave total radioligand binding of <10% total counts added. In a reaction volume of 200 µL, 75 pM [125I]-exendin(9–39), various concentrations of an unlabelled competitor ligand and HEK-293 membranes expressing the receptor of interest were combined, all diluted appropriately in MBS. Assays were carried out for 1 h at room temperature in MultiScreen 96-well Filtration Plates (glass fibre filters, 0.65 µm pore size, Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA) pre-soaked in 1% non-fat milk/PBS. After the incubation, membrane-associated radioligand was harvested by transferring the assay mixture to the filtration plate housed in a vacuum manifold. The wells of the filtration plate were washed three times with 0.2 mL PBS before harvesting the filter discs. Radioactivity was measured in a γ counter (RiaStar 5405 counter; PerkinElmer Life and Analytical Sciences). Total radioligand bound was <10%, and non-specific binding was ∼1% of total counts added.

Radioligand binding using soluble rNTD

In a reaction volume of 300 µL, [125I]-exendin(9–39) (50 pM), various concentrations of unlabelled competitor ligand and rNTD, diluted appropriately in MBS, were combined in 0.5 mL microfuge tubes. Following incubation for 1 h at room temperature, the hexa-histidine-tagged rNTD was separated from free radioligand by the addition of 40 µL of nickel–nitrilotriacetic acid agarose resin (Qiagen Ltd.; Ni-NTA). Following mixing, the resin was allowed to incubate with the rNTD for 30 min before the addition of 100 µL of a phthalate oil mixture (2:1 ratio of dibutyl phthalate to diisononyl phthalate, Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA). The tubes were centrifuged so that the oil formed a layer in-between the resin–rNTD complex and the free radioligand. The tubes were frozen on dry ice, the pellets isolated by cutting off the bottom of the tubes and the radioactivity counted as above. The concentration of rNTD used for the experiments was determined empirically such that it gave total radioligand binding of <10% of the total counts added.

Data analysis

Binding curves in the figures represent one of at least three independent experiments for which each point is the mean of triplicate values with SEM displayed as error bars. Counts were normalized to the maximal specific binding within each data set. IC50 values were calculated with a single site binding model fitted using non-linear regression with the aid of GraphPad PRISM 5 software (San Diego, CA, USA). Values in the tables represent the mean with SEM calculated from the pIC50 values (–log IC50) from at least three independent experiments. Statistical significance was calculated using Student's unpaired t-test with threshold values quoted in the text and tables.

Molecular modelling and dynamics

The crystal structure of the NTD of hGLP-1R bound with Ex4(9–39) (Runge et al., 2008; Protein Data Bank code 3C5T) was used as the starting structure. In order to explore the stability of the putative Trp-cage and the possibility that it interacts with the receptor, this region of the ligand had to be modelled because residues 34*–39* (ligand residues will be identified with an asterisk throughout) were disordered in the crystal structure. The Trp-cage structure was built with the aid of SYBYL v6.3 (Tripos Associates, St Louis, MO, USA) using the Ex4 NMR structure (Neidigh et al., 2001; Protein Data Bank code 1JRJ) by least square superposition of the ligands followed by the replacement of the C-terminal residues of 3C5T with those of 1JRJ. As noted previously, the structures of the two ligand structures are highly compatible, making this modelling stage straightforward (Runge et al., 2008). In silico mutagenesis of Glu68 was carried out using the mutagenesis option within SYBYL v6.3. Molecular dynamics simulations of NTD of hGLP-1R bound with Ex4(9–39) and the E68D mutant were performed using the united atom model CHARMM19 with the implicit solvation model FACTS (Haberthur and Caflisch, 2008) implemented in CHARMM (Brooks et al., 2009). Simulations were performed starting from the conformations described above after a brief energy minimization; simulations were performed at 300K using Langevin dynamics, an integration time step of 2 ns, and were at least 100 ns long.

Results

Competition radioligand binding experiments were carried out using [125I]-exendin(9–39) as the tracer and various unlabelled peptides as competitor ligands. From these experiments, IC50 values were obtained and used as an approximation of binding affinity. The two natural peptides GLP-1 and Ex4 bind to hGLP-1R with similar affinity (Table 1, twofold, P= 0.43), whereas rGLP-1R has a small, but significant preference for Ex4 (Table 1, fivefold, P < 0.005). While the membrane-tethered NTD of hGLP-1R (hNT-TM1) displayed only eightfold preference (P= 0.002) for Ex4 over GLP-1, there was almost 25-fold selectivity (P < 0.001) observed at the rat equivalent (rNT-TM1), and this selectivity was increased to 200-fold at the fully soluble/isolated rNTD (P < 0.001).

Table 1.

Binding properties of the rat and hGLP-1Rs, and truncated receptors lacking all or most of their core domain

| GLP-1 | Ex4 | d1 | Ex4(9–39) | Ex4(9–30) | d2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rGLP-1R | 8.4 ± 0.10 | 9.1 ± 0.08 | 5 | 8.1 ± 0.06 | 6.7 ± 0.08a | 28 |

| rNT-TM1 | 6.9 ± 0.05 | 8.3 ± 0.01a | 25 | 8.1 ± 0.10 | 6.6 ± 0.07a | 35 |

| rNTD | 6.4 ± 0.15 | 8.7 ± 0.03a | 200 | 7.9 ± 0.12 | 6.4 ± 0.11a | 32 |

| hGLP-1R | 8.7 ± 0.07 | 8.9 ± 0.06 | 2 | 8.1 ± 0.06 | 7.8 ± 0.07 | 2 |

| hNT-TM1 | 6.8 ± 0.07 | 7.7 ± 0.02 | 8 | 7.4 ± 0.10 | 6.9 ± 0.11 | 3 |

Significantly different from the value in the cell to the left (P < 0.001).

Values represent mean pIC50 values ± SE for three independent competition binding assays using Ex4(9–39) and Ex4(9–30) as the unlabelled ligands with 125I-Ex4(9–39) as the tracer. d1 refers to the fold change in mean IC50 values of GLP-1 relative to Ex4, while d2 to the fold change in mean IC50 values of Ex4(9–30) relative to Ex4(9–39).

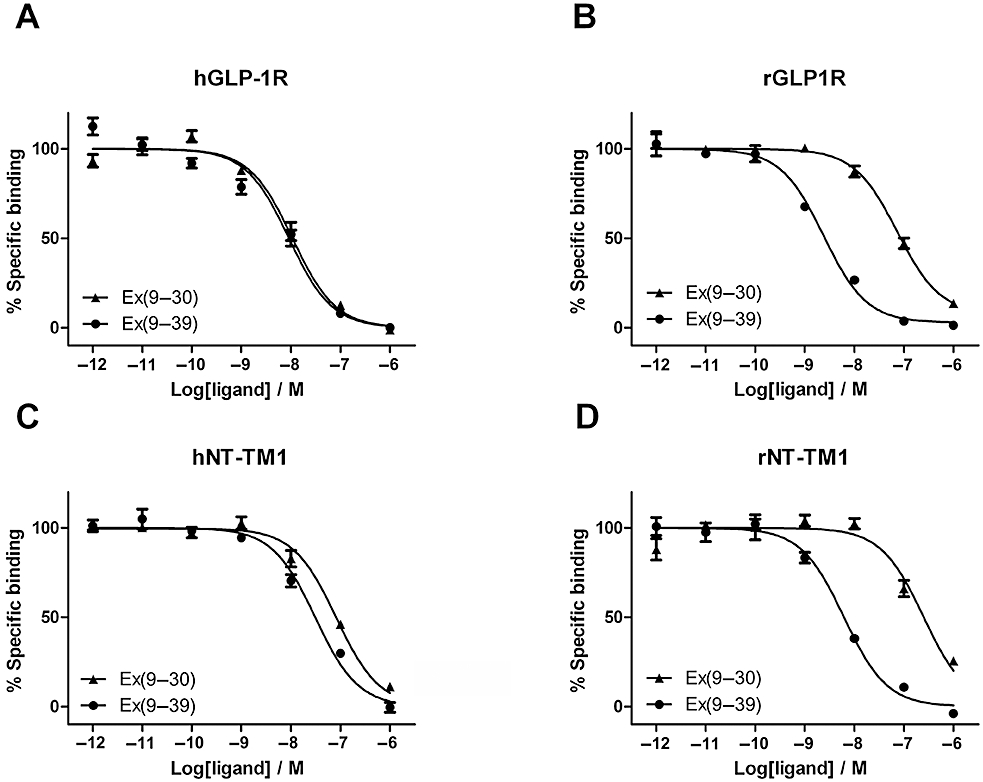

The importance of the C-terminal extension of Ex4(9–39) for binding to either rGLP-1R or hGLP-1R was investigated by comparing Ex4(9–39) with Ex4(9–30). The absence of these nine C-terminal residues was shown to have no significant effect on binding to hGLP-1R (twofold reduction in affinity), whereas it resulted in a 28-fold reduction in affinity at rGLP-1R (Figure 1A,B; Table 1). Receptors consisting of the NTD of either the rat or human receptor anchored in the membrane with transmembrane helix 1 (rNT-TM1 and hNT-TM1) were also tested for their sensitivity to the removal of the C-terminal extension (Figure 1C,D; Table 1). These mirrored the effects observed at the full-length receptors (threefold reduction in affinity at hNT-TM1 and 35-fold at rNT-TM1), indicating that residues 31*–39* (ligand residues will be identified with an asterisk throughout) of Ex4(9–39) interact with the NTD of rGLP-1R. Moreover, the fully isolated/soluble rNTD also displayed a 32-fold selectivity for Ex4(9–39) over Ex4(9–30).

Figure 1.

Competition radioligand binding experiments using [125I]-Ex4(9–39) as the tracer and either Ex4(9–39) or Ex4(9–30) as the competing ligands, at (A) hGLP-1R, (B) rGLP-1R, (C) hNT-TM1 and (D) rNT-TM1. The panels each represent a typical example of one of three independent experiments. The receptors derived from rat are highly sensitive to the removal of the C-terminal extension of Ex4, while those from human are not.

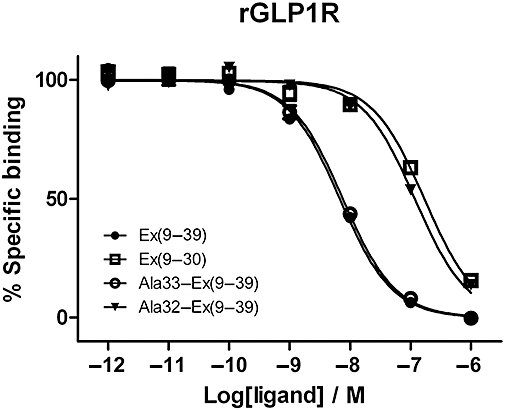

To investigate whether the contribution to affinity made by residues 31*–39* at rGLP-1R was due to the formation of a Trp-cage motif, competition binding was carried out using Ala33–Ex4(9–39) as the competing ligand. The study of mini-proteins via NMR has shown that Ser-33* is essential for Trp-cage formation due to a hydrogen bond made by the serine side chain (Barua et al., 2008), and therefore the removal of the hydroxyl moiety would be expected to prevent the formation of this motif. However, this modified peptide ligand bound to rGLP-1R with similar affinity to Ex4(9–39) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Competition radioligand binding experiments at the rGLP-1R using [125I]-Ex4(9–39) as the tracer and either Ex4(9–39), Ex4(9–30), Ala32-Ex4(9–39) or Ala33-Ex4(9–39) as the competing ligands. Note that the curves for Ex4(9–39) and Ala33(Ex4(9–39) are overlaid. Curves represent a typical example of one of three independent experiments. Mean pIC50 for Ala33–Ex4(9–39) is 8.01 ± 0.14 (n= 3); see Table 2 for other pIC50 values. Disruption of the putative Trp-cage, via removal of the side chain hydroxyl of Ser-33*, had no effect upon Ex4(9–39) affinity, whereas removal of the Ser-32* hydroxyl reduces the affinity to that of the C-terminally truncated peptide.

In contrast, removal of the hydroxyl group from Ser-32* had a pronounced effect, with Ala32–Ex4(9–39) displaying a similar reduction in affinity relative to Ex4(9–39), as had been seen for Ex4(9–30) (21-fold and 28-fold, respectively; Figure 2 and Table 2).

Table 2.

Binding properties of mutant and wild-type GLP-1R

| Ex4(9–39) | Ex4(9–30) | Ala32–Ex4(9–39) | d2 | d3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rGLP-1R | 8.1 ± 0.06 | 6.7 ± 0.08a | 6.9 ± 0.08a | 28 | 21 |

| rGLP-1R D68E | 7.8 ± 0.08 | 7.4 ± 0.09 | 7.4 ± 0.14 | 3 | 2 |

| rGLP-1R D68A | 8.6 ± 0.05 | 8.0 ± 0.06 | 8.2 ± 0.06 | 4 | 2 |

| hGLP-1R | 8.1 ± 0.06 | 7.8 ± 0.07 | 7.7 ± 0.14 | 2 | 2 |

| hGLP1R E68D | 8.2 ± 0.02 | 6.9 ± 0.01a | 7.0 ± 0.03a | 21 | 16 |

Significantly different (P < 0.0005) compared to Ex4(9–39).

Values represent mean pIC50 values ± SE for three independent competition binding assays using Ex4(9–39), Ex4(9–30) and Ala32–Ex4(9–39) as the unlabelled ligands with 125I-Ex4(9–39) as the tracer. d2 refers to the fold change in mean IC50 values of Ex4(9–30) relative to Ex4(9–39), and d3 refers to the fold change in mean IC50 values of Ala32–Ex4(9–39) relative to Ex4(9–39).

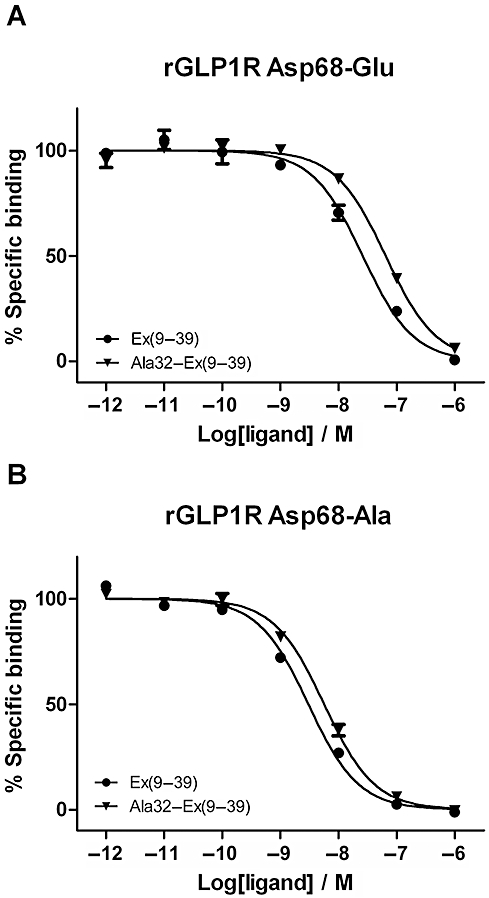

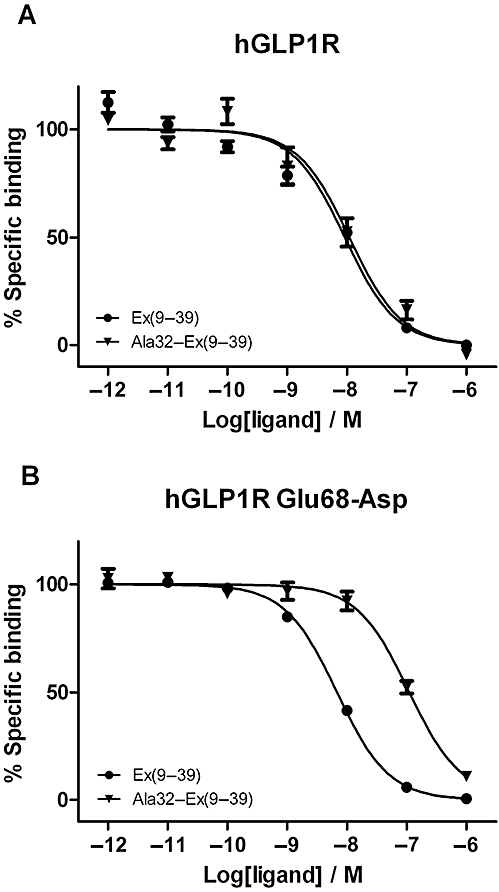

The mutation of Asp68 to Glu in rGLP-1R resulted in a receptor that was no longer affected by removal of the C-terminal nine residues of Ex4(9–39) (threefold reduction in affinity; Table 2) or by the replacement of Ser-32* with Ala in Ex4(9–39) (twofold reduction in affinity; Figure 3A and Table 2). Likewise, Asp68–Ala in rGLP-1R was also insensitive to either C-terminal truncation of Ex4(9–39) (fourfold) or by the removal of the side chain hydroxyl at residue 32* (twofold decrease in affinity of Ala32–Ex4(9–39) relative to Ex4(9–39); Figure 3B and Table 2). Conversely, mutation of Glu68 to Asp in hGLP-1R caused the receptor to become sensitive both to N-terminal deletion (21-fold reduction in affinity; Table 2), as well as to the replacement of Ser32* by Ala in Ex4(9–39) (16-fold reduction in affinity; Table 2 and Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Competition radioligand binding experiments using [125I]-Ex4(9–39) as the tracer and either Ex4(9–39) or Ala32–Ex4(9–39) as the competing ligands at (A) rGLP-1R Asp68–Glu and (B) rGLP-1R Asp68–Ala. Curves represent a typical example of one of three independent experiments. Removal of the hydrogen-bonding capability of Asp68 by replacing it with Ala abolishes the ability of rGLP-1R to select between the two ligands (compare with Figure 1B). The ability to select between the peptides is also absent in the Asp68–Glu mutant, suggesting that the glutamic acid side chain cannot interact with Ser-32*.

Figure 4.

Competition radioligand binding experiments using [125I]-Ex4(9–39) as the tracer and either Ex4(9–39) (circles) or Ala32–Ex4(9–39) (triangles) as the competing ligands at (A) hGLP-1R and (B) hGLP-1R Glu68–Asp. The panels each represent a typical example of one of three independent experiments. The replacement of the native glutamate in hGLP-1R with Asp confers the ability to select between Ex4(9–39) and Ala32–Ex(9–39).

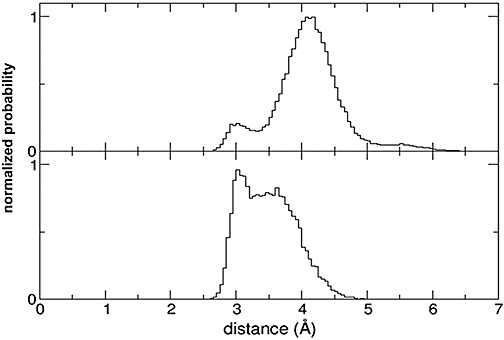

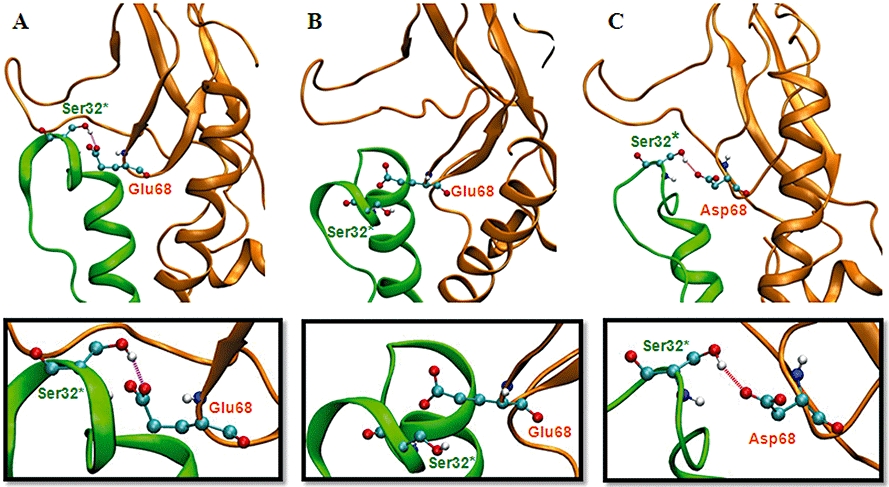

In order to interpret the data described above and to investigate the nature of the receptor–ligand interaction in more detail, long equilibrium molecular dynamics simulations of NTD of hGLP-1R and the E68D mutant bound with Ex4(9–39) were carried out as described in Methods. Figure 5 (upper panel) shows a histogram of the distance between the side chain oxygen of Ser32* of Ex4(9–39) and the carboxyl group of Glu68 of hGLP-1R; this has a small peak at an optimum distance for hydrogen bond formation (∼3 Å). It can be seen at the wild-type hGLP-1R that, despite a hydrogen bond being present in the starting structure, there is a low probability that a hydrogen bonding distance can be maintained (a snapshot of this low-frequency event is shown in Figure 6A). Instead, the atoms spend most of their time bent away at a distance too great for a hydrogen bond (Figure 6B). However, when Glu68 is mutated to Asp, there is a much greater probability of the atoms being at an ideal distance to form a hydrogen bond (Figure 5, lower panel). This situation is illustrated in Figure 6C.

Figure 5.

Histogram chart showing calculations from molecular dynamics simulations showing the probability (normalized so that the integral between 0 and infinity is 1) that the side chain oxygen of Ser-32* of Ex4(9–39) and the closest side chain oxygen of Asp/Glu68 of GLP-1R are at a given distance. A peak at 3 Å indicates the atoms are at an ideal distance for hydrogen bond formation to occur. Upper panel: probabilities of distances between atoms of Ser-32* in Ex4(9–39) and Glu68 in GLP-1R. Lower panel: probabilities of distances between atoms of Ser32* in Ex4(9–39) and Asp68 in GLP-1R.

Figure 6.

Ribbon diagrams illustrating snapshots of the structure of Ex4(9–39) bound to hGLP-1R taken from different points during molecular dynamics simulations. Ex4(9–39) is shown in green, GLP-1R is shown in orange and the atoms of Ser32* of Ex4(9–39) and Glu/Asp68 from GLP-1R are shown as ball and sticks coloured by atom type. Hydrogen bond formation between these groups is indicated (see boxed panels for close-up views). In the wild-type hGLP-1R, Ser32* and Glu68 spend a relatively short amount of time at a hydrogen bonding distance, for example, (A) while, instead, the majority of time is spent over 4 Å apart, for example, (B), a distance too great to allow a hydrogen bond. In Glu68–Asp hGLP-1R, Ser32* and Asp68 have a high probability of forming a distance ideal for hydrogen bond formation, for example (C).

Discussion

The crystal structure of the NTD of hGLP-1R and Ex4(9–39) shows that the ligand forms an α-helix from residues Leu-10*–Asn-28*, but that only Glu-15* to Asn-28* actually contacts the NTD (Runge et al., 2008). Likewise, the recent structure of GLP-1 bound to the NTD of hGLP-1R shows that GLP-1 forms an α-helix from Thr-13* to Val-33*, with only Ala-24*–Val-33* contacting the NTD (Neidigh et al., 2001; Underwood et al., 2010). The binding sites of Ex4 and GLP-1 are remarkably similar, and, although the α-helix of GLP-1 is kinked relative to that of Ex4(9–39), this occurs at Gly-22* in a region that does not contact the NTD (Neidigh et al., 2001; Underwood et al., 2010). The crystal structures do not appear to explain why Ex4 has such enhanced affinity for this fully isolated/soluble NTD compared with GLP-1 (187- to 400-fold; Lopez de Maturana et al., 2003; Runge et al., 2007), and indeed a mutagenic analysis of the peptide binding site failed to locate a specific interaction that accounts for this large affinity difference, but rather identified a more subtle sevenfold differential affinity (Underwood et al., 2010). This was in keeping with the conclusions of a detailed biophysical study which demonstrated that it is the higher helical propensity of Ex4 compared with GLP-1 that was responsible for its enhanced affinity at the isolated NTD (Runge et al., 2007).

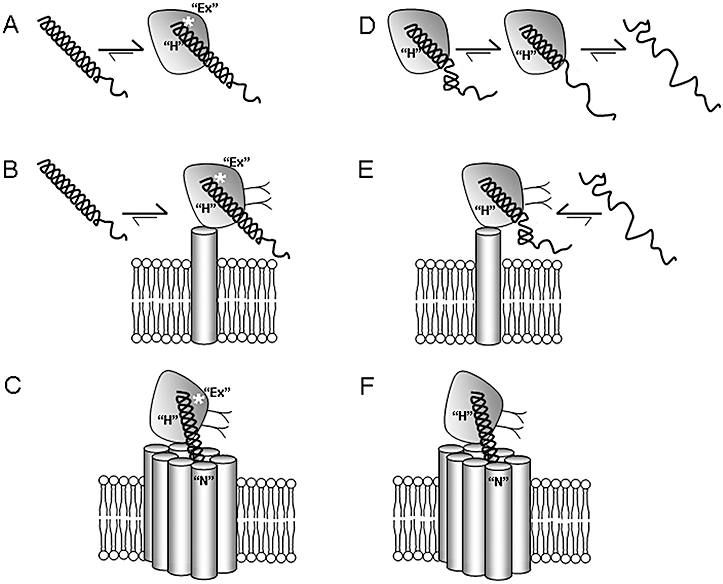

Here, we demonstrate a surprising observation showing that the large difference in affinity between GLP-1 and Ex4 observed at the isolated NTD of hGLP-1R was almost absent at the membrane-tethered hNT-TM1 (eightfold; Table 1). This similarity in binding affinity is in agreement with the binding data resulting from the mutagenic analysis of Reedtz-Runge and co-workers, which implies that Ex4 makes only minor additional interactions with the NTD of hGLP-1R relative to GLP-1 (Underwood et al., 2010). However, the data appear to conflict with the binding data at the fully isolated NTD, and therefore, in order to explain these apparently conflicting observations, we propose a modified peptide/receptor binding model (Figure 7). While the 200-fold difference in affinity between GLP-1 and Ex4 at rGLP-1R was substantially reduced at rNT-TM1 (25-fold), there nevertheless still remained a significant difference between the affinities of the two peptides (Table 1). We have described this observation previously and have accounted for it by defining an extra ‘Ex’ interaction between Ex4 and the NTD of rGLP-1R, which we localized to the C-terminal extension of Ex4 (asterisk in Figure 7A–C; Al-Sabah and Donnelly, 2003a). This ‘Ex’ interaction also accounts for the ∼30-fold difference between the affinities of Ex4(9–39) and Ex4(9–30) observed at both the isolated rNTD and rNT-TM1 (Table 2; Al-Sabah and Donnelly, 2003a). The modest affinity enhancement that Ex4 attains over GLP-1 as a result of the ‘Ex’ interaction with rGLP-1R is physiologically relevant and should not be confused with the larger affinity difference observed at the isolated NTD, which results from the low helical propensity of GLP-1 in this artificial receptor-binding environment.

Figure 7.

A model for the binding of Ex4 (left panels, A–C) and GLP-1 (right panels, D–F) to either the fully isolated/soluble NTD of GLP-1R expressed in Escherichia coli (A, D), the isolated NTD tethered to the membrane, expressed in HEK-293 cells (NT-TM1, B and E) or the full-length receptor expressed in HEK-293 cells (C, F). The helical structure of the peptide ligands is critical for their high-affinity interaction with the NTD via the ‘H’ interaction. (A) A cartoon representation of the binding of Ex4 (helix) with the isolated NTD of GLP-1R based on the crystal structure. The C-terminal half of the peptide interacts with the NTD, while the high helical propensity of Ex4 enables its helical structure to remain intact, despite the absence of interactions with the N-terminal region of the ligand. However, the binding of GLP-1 with the isolated NTD of GLP-1R occurs with much lower affinity because the lower helical propensity of GLP-1, coupled with the absence of interactions with the N-terminal region of the ligand, results in the more frequent unwinding of the helix, loss of the ‘H’ interaction and consequent dissociation of the ligand (D). Hence, there is a large affinity difference between Ex4 and GLP-1 at the isolated NTD (200- to 400-fold), which reflects the difference in helical propensity rather than the relative strength of the ‘H’ interaction. However, the two ligands bind with much more similar affinity to the isolated NTD tethered to the plasma membrane (B, E). We speculate that this is due to the close proximity of the membrane, which stabilizes the N-terminal region of GLP-1, eliminating the difference in helical propensity, and thus enabling the C-terminal helix to remain intact and interact with the NTD. The addition of the core domain of the receptor (C, F) results in additional interactions with the N-terminal region of the ligands, the ‘N’ interaction, which is stronger for GLP-1 than for Ex4. A third interaction, termed ‘Ex’ (white asterisk), represents a specific interaction between Ser-32* in the C-terminal region of Ex4 and the NTD of rGLP-1R.

However, in contrast to these observations at the rat receptor, the deletion of the C-terminal extension from Ex4(9–39) had a minimal effect on binding affinity at either the full-length hGLP-1R or the membrane-tethered hNT-TM1 (Table 1; Figure 1A,C), in agreement with data obtained using the fully isolated soluble hNTD (Runge et al., 2007). Further evidence for the absence of a role for the C-terminal extension of Ex4 in binding came from the crystal structure of Ex4(9–39) bound to the soluble NTD of hGLP-1R, which showed that residues 34*–39* of Ex4(9–39) were disordered and did not contact the receptor (Runge et al., 2008). Given these data, it would appear that the extra nine residues that make up the C-terminal extension of Ex4 enhance the affinity for rGLP1R, but play little or no role in generating affinity for the human receptor.

As the C-terminal extension of Ex4 has been shown to form part of a Trp-cage motif in some environments (Neidigh et al., 2001), it is feasible that this structure could play a role in enhancing the affinity of the peptide at rGLP-1R. Trp-cage formation is dependent upon a number of sequence-dependent features, one of which is the presence of the hydroxyl side chain of Ser-33* which forms an intra-molecular hydrogen bond (Barua et al., 2008). Therefore, in order to examine the putative role of the Trp-cage in enhancing the affinity of Ex4(9–39), we substituted Ser-33* with Ala, preventing the intra-molecular hydrogen bond and hence disrupting Trp-cage formation. However, this substitution had no effect upon the peptide's affinity at rGLP-1R (Figure 2). Hence, it is clear that our earlier speculation was wrong because neither the putative Trp-cage motif nor the hydroxyl side chain of Ser-33* is responsible for the observed affinity enhancement mediated by residues 31*–39*. These data were substantiated in our molecular dynamics simulations where the Trp-cage motif included in the starting conformation was observed to unfold early in the simulation (data not shown).

In order to explain how the C-terminal extension of Ex4(9–39) generates affinity for rGLP-1R, but not hGLP-1R, the species-specific residues in the vicinity of the binding site of this region of the peptide were identified from the crystal structure (Runge et al., 2008). In fact, only Glu68 (Asp-68 in rGLP-1R) appeared to be capable of interacting with the C-terminal region of Ex4(9–39) via an interaction with Ser-32*. The replacement of Ser-32* with Ala in Ex4(9–39) reduced affinity at rGLP-1R to a similar extent as the deletion of the entire C-terminal region of the peptide (Table 2; Figure 2), and it may be concluded therefore that the hydroxyl side chain of this residue is responsible for the enhanced affinity at rGLP-1R caused by the presence of the C-terminal extension.

Although the crystal structure shows that Glu-68 forms a hydrogen bond with Ser-32* of the ligand, the authors imply that this assignment was tentative due to the increasing B-factors at the C-terminal end of the ligand. Indeed, our molecular dynamic simulations demonstrated that this interaction was transient and unlikely to generate affinity (Figure 5A), and we confirmed this experimentally by the disruption of this interaction via the replacement of Ser-32* with Ala in Ex4(9–39), which had no effect on the peptide's affinity at hGLP-1R (Table 2; Figure 4A).

On the other hand, the molecular dynamic simulations using the hGLP-1R mutant Glu-68–Asp (generated in silico) bound with Ex4(9–39), predicted a much more stable interaction via a hydrogen bond between the Asp-68 side chain and the hydroxyl group of Ser-32*. It would therefore be expected that the removal of the hydroxyl from Ser-32* would manifest as a reduction in binding affinity and, once again, this was confirmed experimentally (Table 2; Figure 4B). Indeed, despite the subtle change at only one side chain, the Glu-68–Asp mutation at hGLP-1R conferred pharmacological selectivity that closely resembled that observed at rGLP-1R, presumably by enabling the ‘Ex’ interaction to form.

To confirm the importance of the Asp-68–Ser-32* interaction between rGLP-1R and Ex4(9–39), this residue was mutated to either Glu or Ala. The Asp-68–Ala mutation would result in a side chain that cannot hydrogen bond with Ser-32*, and indeed this mutant receptor was insensitive to the removal of the serine hydroxyl of Ex4(9–39) or the truncation of residues 31*–39* (Table 2; Figure 3B). Moreover, despite its theoretical ability to form an interaction resembling Asp-68, the sensitivity of the Asp-68–Glu mutant to the removal of the Ser32* hydroxyl closely resembled that of the Asp-68–Ala mutant, indicating that no stable interaction between Glu68 and Ser-32* was formed. While the mutations at Asp-68 abolished the selectivity between Ex4(9–39) and Ala32–Ex4(9–39), both mutants bound the peptides with higher affinity than expected, suggesting the possibility that conformational changes in the protein structure may enhance interactions with other regions of the peptide. While mutations often result in such unexpected observations, we have found previously that the difference in the affinities of two very similar ligands at the same receptor is highly diagnostic for identifying ligand–receptor interactions (Mann et al., 2008; Pioszak et al. 2009). Taken with the data from the pharmacological and dynamics analyses of hGLP-1R, it can be concluded that a glutamic acid side chain at residue 68 of GLP-1R cannot form a stable hydrogen bond with Ser-32* of the peptide ligand, and therefore does not contribute to the affinity of the peptide.

In summary, we have identified a specific interaction between rGLP-1R and the C-terminal extension of Ex4(9–39). Rather than being formed via the putative Trp-cage of the peptide ligand, it is most likely to be the result of a hydrogen bond formed between the side chains of Asp-68 and Ser-32*. This interaction improves the affinity of the peptide by 20- to 30-fold, and accounts for the ‘Ex’ interaction which we had observed previously (Al-Sabah and Donnelly, 2003a). This ‘Ex’ interaction is responsible for the insensitivity of Ex4 to N-terminal truncation at rGLP-1R (MontroseRafizadeh et al., 1997) and for the high affinity of Ex4 for the membrane-tethered NTD of rGLP-1R. Furthermore, the absence of the ‘Ex’ interaction in Ex4 binding to hGLP-1R results in a much more modest Ex4/GLP-1 differential affinity, while the much larger differential affinity observed at the fully isolated NTD is independent of the ‘Ex’ interaction and derives from the absence of a stabilizing interaction with the N-terminal half of GLP-1.

Acknowledgments

We thank BBSRC, AstraZeneca and the Egyptian government for funding.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- Ex4

exendin-4

- GLP-1

glucagon-like peptide 1

- GLP-1R

GLP-1 receptor

- GPCR

G protein-coupled receptors

- hGLP-1R

human GLP-1R

- hNTD

N-terminal domain of hGLP-1R

- NTD

N-terminal domain of GLP-1R

- rGLP-1R

rat GLP-1R

- rNTD

N-terminal domain of rGLP-1R

Conflict of interest

None to declare.

References

- Al-Sabah S, Donnelly D. A model for receptor-peptide binding at the glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor through the analysis of truncated ligands and receptors. Br J Pharmacol. 2003a;140:339–346. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Sabah S, Donnelly D. The positive charge at Lys-288 of the glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor is important for binding the N-terminus of peptide agonists. FEBS Lett. 2003b;553:342–346. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)01043-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander SPH, Mathie A, Peters JA. Guide to Receptors and Channels (GRAC), 4th edition. Br J Pharmacol. 2009;158:S1–S239. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00499.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baggio LL, Drucker DJ. Biology of incretins: GLP-1 and GIP. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:2131–2157. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.03.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barua B, Lin JC, Williams VD, Kummler P, Neidigh JW, Andersen NH. The Trp-cage: optimizing the stability of a globular miniprotein. Protein Eng Des Sel. 2008;21:171–185. doi: 10.1093/protein/gzm082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks BR, Brooks CL, Mackerell IIIAD, Jr, Nilsson L, Petrella RJ, Roux B, et al. CHARMM: the biomolecular simulation program. J Comput Chem. 2009;30:1545–1614. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeFronzo RA, Ratner RE, Han J, Kim DD, Fineman MS, Baron AD. Effects of exenatide (exendin-4) on glycemic control and weight over 30 weeks in metformin-treated patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:1092–1100. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.5.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drucker DJ. Minireview: the glucagon-like peptides. Endocrinology. 2001;142:521–527. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.2.7983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eng J, Kleinman WA, Singh L, Singh G, Raufman JP. Isolation and characterization of exendin-4, an exendin-3 analog, from heloderma-suspectum venom – further evidence for an exendin receptor on dispersed acini from guinea-pig pancreas. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:7402–7405. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goke R, Fehmann HC, Linn T, Schmidt H, Krause M, Eng J, et al. Exendin-4 is a high potency agonist and truncated exendin-(9–39)-amide an antagonist at the glucagon-like peptide 1-(7–36)-amide receptor of insulin-secreting beta-cells. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:19650–19655. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grace CRR, Perrin MH, Gulyas J, DiGruccio MR, Cantle JP, Rivier JE, et al. Structure of the N-terminal domain of a type B1 G protein-coupled receptor in complex with a peptide ligand. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:4858–4863. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700682104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haberthur U, Caflisch A. FACTS: fast analytical continuum treatment of solvation. J Comput Chem. 2008;29:701–715. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kieffer TJ, Habener JL. The glucagon-like peptides. Endocr Rev. 1999;20:876–913. doi: 10.1210/edrv.20.6.0385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knudsen LB, Agerso H, Bjenning C, Bregenholt S, Carr RD, Godtfredsen C, et al. GLP-1 derivatives as novel compounds for the treatment of type 2 diabetes: selection of NN2211 for clinical development. Drugs Future. 2001;26:677–685. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez de Maturana R, Donnelly D. The glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor binding site for the N-terminus of GLP-1 requires polarity at Asp198 rather than negative charge. FEBS Lett. 2002;530:244–248. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)03492-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez de Maturana R, Willshaw A, Kuntzsch A, Rudolph R, Donnelly D. The isolated N-terminal domain of the glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor binds exendin peptides with much higher affinity than GLP-1. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:10195–10200. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212147200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann R, Wigglesworth MJ, Donnelly D. Ligand–receptor interactions at the parathyroid hormone receptors: subtype binding selectivity is mediated via an interaction between residue 23 on the ligand and residue 41 on the receptor. Mol Pharmacol. 2008;74:605–613. doi: 10.1124/mol.108.048017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews JE, Stewart MW, De Boever EH, Dobbins RL, Hodge RJ, Walker SE, et al. Albiglutide Study Group. Pharmacodynamics, pharmacokinetics, safety, and tolerability of albiglutide, a long-acting glucagon-like peptide-1 mimetic, in patients with type 2 diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:4810–4817. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-1518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayo KE, Miller LJ, Bataille D, Dalle S, Goke B, Thorens B, et al. International Union of Pharmacology. XXXV. The glucagon receptor family. Pharmacol Rev. 2003;55:167–194. doi: 10.1124/pr.55.1.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MontroseRafizadeh C, Yang H, Rodgers BD, Beday A, Pritchette LA, Eng J. High potency antagonists of the pancreatic glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:21201–21206. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.34.21201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neidigh JW, Fesinmeyer RM, Prickett KS, Andersen NH. Exendin-4 and glucagon-like-peptide-1: NMR structural comparisons in the solution and micelle-associated states. Biochemistry. 2001;40:13188–13200. doi: 10.1021/bi010902s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orskov C, Holst JJ, Nielsen OV. Effect of truncated glucagon-like peptide-1 [proglucagon-(78–107) amide] on endocrine secretion from pig pancreas, antrum, and nonantral stomach. Endocrinology. 1988;123:2009–2013. doi: 10.1210/endo-123-4-2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parthier C, Kleinschmidt M, Neumann P, Rudolph R, Manhart S, Schlenzig D, et al. Crystal structure of the incretin-bound extracellular domain of a G protein-coupled receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:13942–13947. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706404104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pioszak AA, Xu HE. Molecular recognition of parathyroid hormone by its G protein-coupled receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:5034–5039. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801027105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pioszak AA, Parker NR, Suino-Powell K, Xu HE. Molecular recognition of corticotropin-releasing factor by its G-protein-coupled receptor CRFR1. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:32900–32912. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M805749200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pioszak AA, Parker NR, Gardella TJ, Xu HE. Structural basis for parathyroid hormone-related protein binding to the parathyroid hormone receptor and design of conformation-selective peptides. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:28382–28391. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.022905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Runge S, Schimmer S, Oschmann J, Schiodt CB, Knudsen SM, Jeppesen CB, et al. Differential structural properties of GLP-1 and exendin-4 determine their relative affinity for the GLP-1 receptor N-terminal extracellular domain. Biochemistry. 2007;46:5830–5840. doi: 10.1021/bi062309m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Runge S, Thogersen H, Madsen K, Lau J, Rudolph R. Crystal structure of the ligand-bound glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor extracellular domain. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:11340–11347. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708740200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor K, Kim D, Bicsak T, Heintz S, Varns A, Aisporna M, et al. Continuous subcutaneous infusion of AC2993 (synthetic exendin-4) provides sustained, day-long glycemic control to patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2002;51:344. [Google Scholar]

- Turton MD, Oshea D, Gunn I, Beak SA, Edwards CMB, Meeran K, et al. A role for glucagon-like peptide-1 in the central regulation of feeding. Nature. 1996;379:69–72. doi: 10.1038/379069a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Underwood CR, Garibay P, Knudsen LB, Hastrup S, Peters GH, Rudolph R, et al. Crystal structure of glucagon-like peptide-1 in complex with the extracellular domain of the glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:723–730. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.033829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wettergren A, Schjoldager B, Mortensen PE, Myhre J, Christiansen J, Holst JJ. Truncated Glp-1 (proglucagon 78–107-amide) inhibits gastric and pancreatic functions in man. Dig Dis Sci. 1993;38:665–673. doi: 10.1007/BF01316798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]