Abstract

Selective decontamination of the digestive tract (SDD) has been subject of numerous randomized controlled trials in critically ill patients. Almost all clinical trials showed SDD to prevent pneumonia. Nevertheless, SDD has remained a controversial strategy. One reason for why clinicians remained reluctant to implement SDD into daily practice could be that mortality was reduced in only 2 trials. Another reason could be the heterogeneity of trials of SDD. Indeed, many different prophylactic antimicrobial regimes were tested, and dissimilar diagnostic criteria for pneumonia were applied amongst the trials. This heterogeneity impeded interpretation and comparison of trial results. Two other hampering factors for implementation of SDD have been concerns over the risk of antimicrobial resistance and fear for escalation of costs associated with the use of prophylactic antimicrobials. This paper describes the concept of SDD, summarizes the results of published trials of SDD in mixed medical-surgical intensive care units, and rationalizes the risk of antimicrobial resistance and rise of costs associated with this potentially life-saving preventive strategy.

1. Introduction

Potentially pathogenic microorganisms such as Gram-negative bacteria (including Pseudomonas aeruginosa), Gram-positive bacteria (including Staphylococcus aureus), and yeasts rapidly colonize stomach and intestines of critically ill patients [1]. Retrograde colonization of the oral cavity and throat may occur, and microaspiration into the lung could eventually result in pneumonia [2]. Prevention of colonization of oral cavity, throat, stomach, and intestines could reduce the incidence of respiratory tract infections, thereby improving outcome of intensive care unit (ICU) patients.

Selective decontamination of the digestive tract (SDD) is one strategy to prevent colonization of oral cavity, throat, stomach, and intestines of ICU patients. Numerous randomized controlled clinical trials have suggested SDD a beneficial strategy. Indeed, reductions in the incidence of pneumonia have been achieved with the use of SDD in critically ill patients [3]. However, only 2 trials showed SDD to reduce mortality [4, 5]. This may have caused caregivers to become indisposed to apply this strategy in daily practice. In addition, fear for emergence of antimicrobial resistance and escalation of costs associated with SDD, at least in part, hampered widespread implementation of this preventive strategy.

It should be noticed that the concept of colonization and infection as presented by Stoutenbeek and van Saene concerned trauma patients. It can be questioned whether this concept holds true for other ICU patients. Indeed, these patients are older, have significant comorbidities, and are frequently on antibiotics already at or before admission to the ICU.

We here describe the concept of SDD. We summarize the numerous clinical trials of SDD, focusing on trials applying the original SDD strategy in mixed medical-surgical ICUs and having pneumonia and/or mortality as a primary endpoint. Concerns over bacterial resistance and costs associated with SDD are discussed and rationalized.

2. ICU-Related Infections

2.1. Incidence and Outcome

ICU-related infections, in particular pneumonia, constitute a major problem during critical illness [6, 7]. Up to 50% of critically ill patients develop pneumonia [8]. When critically ill patients develop pneumonia, ICU and hospital mortality may double [9]. In accordance, patients with pneumonia need mechanical ventilation for a longer period of time and have a prolonged stay in ICU and hospital [10, 11]. Consequently, costs rise when pneumonia develops [12–14].

2.2. Primary and Secondary Endogenous versus Exogenous Infections

ICU-related infections can be classified into primary endogenous, secondary endogenous, and exogenous infections [15].

Primary endogenous infections are caused by pathogens carried in throat, stomach, and/or intestines of patient on ICU-admission. They occur generally within one week after admission and can be prevented by parenteral antibiotics administered directly after admission to the ICU.

Secondary endogenous infections may also occur soon after admission to the ICU. Contrary to primary endogenous infections, pathogens involved with secondary endogenous infections are not carried in throat, stomach, and/or intestines on admission but acquired during stay in ICU, and mostly from other patients via the hands of caregivers. Most of these infections could be banned if colonization is prevented.

Exogenous infections can occur at any time during stay in ICU and occur when exogenous pathogens are accidentally introduced into a sterile internal organ without previous carriage.

2.3. Pathogenic Microorganisms of ICU-Related Infections

Micro-organisms differ in their pathogenicity. For example, fast majorities of ICU patients carry Enterococcus spp. in high concentrations in the intestines; infections caused by these microorganisms are rare. Conversely, 30%–40% of ICU patients who carry aerobic Gram-negative bacteria (including P. aeruginosa and Klebsiella spp.) in the oral cavity, throat or intestines develop an infection caused by these organisms.

The pathogenicity can be expressed in the Intrinsic Pathogenicity Index (IPI) [16]. IPI is number of patients infected by species x/number of patients carrying species × in throat or intestines. The range of IPI is from 0 to 1. Carriage of a microorganism with an IPI close to 0 will seldom be followed by an infection. Carriage of a microorganism with an IPI close to 1 will almost always be followed by an infection. According to the IPI, microorganisms can be divided in low, potentially and highly pathogenic microorganisms (Table 1). Prevention of carriage with pathogens with an IPI close to 1 is thought to benefit ICU patients.

Table 1.

Pathogenicity of microorganisms.

| Site of carriage | Micro-organisms involved | Flora |

|---|---|---|

| Low pathogenic microorganisms; IPI = 0.01 | ||

| Throat | Streptococcus viridans | Normal |

| Veillonella spp. | ||

| Peptostreptococci | ||

| Gut | Bacteroides spp. | |

| Clostridium spp. | ||

| Enterococcus spp | ||

| Escherichia Coli | ||

| Vagina | Indigenous flora | |

| Skin | Coagulase-negative Staphylococci | |

|

| ||

| Potentially pathogenic microorganisms; IPI = 0.3–0.6 | Normal | |

| “Community” PPM | ||

| Throat | Streptococcus pneumoniae | |

| Hemophilus. Influenzae | ||

| Moraxella catarrhalis | ||

| Staphylococcus aureus | ||

| Candida spp. | ||

| Gut | Escherichia coli | |

| Staphylococcus aureus | ||

| Candida spp. | ||

|

| ||

| “Hospital” PPM | ||

|

| ||

| Throat and gut | Klebsiella spp. | Abnormal |

| Proteus spp. | ||

| Morganella spp. | ||

| Enterobacter spp. | ||

| Citrobacter spp. | ||

| Serratia spp. | ||

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | ||

| Acinetobacter spp. | ||

| Multiresistant Staphylococcus aureus | ||

|

| ||

| Highly pathogenic microorganisms; IPI = 0.9–1.0 | ||

| “Epidemic” microorganisms | ||

| Throat | Neisseria meningitides | Abnormal |

| Gut | Salmonella spp. | |

See text for details.

3. Prevention of ICU-Related Infections

3.1. Selective Decontamination of the Digestive Tract

Multiple strategies to reduce the incidence of respiratory infections in ICU patients have been evaluated, including SDD. Van der Waaij et al. were the first to describe the concept of SDD in 1971 [17]. The concept of SDD is based on colonization resistance—the intact, anaerobic intestinal flora is protective against secondary colonization with Gram-negative aerobic bacteria. Disturbance or loss of this anaerobic flora leads to increased colonization and increased risk of infection with facultative aerobic bacteria. SDD should prevent colonization with aerobic Gram-negative bacteria and other pathogens, without disrupting the anaerobic flora with the aim to reduce the incidence of secondary infections.

3.2. Components of SDD

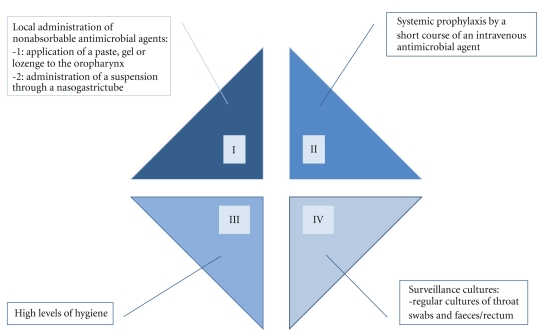

SDD classically consists of 4 components [18] (Figure 1):

Figure 1.

The 4 components of the original SDD regimen.

selective eradication of pathogenic microorganisms in the oral cavity and decontamination of the stomach and intestines by local administration of nonabsorbable antimicrobial agents—the first is reached by application of a paste, gel, or lozenge to the oropharynx, the second by administration of a suspension through a nasogastric tube;

systemic prophylaxis by a short course of an intravenous antimicrobial agent—to prevent respiratory infections that may occur during the ICU stay, caused by commensal respiratory flora;

high levels of hygiene to prevent cross-contamination;

surveillance cultures (regular cultures of throat swabs and feces/rectum) to monitor the effectiveness of SDD.

It has been suggested that failure to apply this complete 4-component model reduces the effectiveness of SDD [19], although this has neither been tested nor proven.

4. Studies of SDD

4.1. Search Strategy

We identified relevant publications on SDD by searching the PubMed, EMBASE, and Cochrane Library databases using the following terms or MeSH subject heading: [intensive care], [critical care], [critical illness], [critical mortality], [infections], [pneumonia], [infection control], [selective digestive decontamination], [antibiotic prophylaxis], [antibacterial agents/therapeutic use], [bacterial infections/prevention and control], [drug resistance (microbial/bacterial)], [costs and cost analysis], [cost–benefit analysis], [cost-effectiveness analysis], [economics], [drug costs], and [health care costs]. Reference lists from identified citations and relevant review articles were hand searched for additional potentially relevant publications and abstracts.

With this search strategy, trials analyzing the oral decontamination strategy were also found, but subsequently we focused on the complete SDD regimen. We also restricted our search to trials performed in mixed medical-surgical ICUs and to studies that had pneumonia and/or mortality as the primary endpoint. Adjacent to this, we looked for studies that focused on antimicrobial resistance induced by SDD and studies that analyzed costs of SDD treatment.

4.2. Search Results

The search yielded 336 manuscripts of potential interest. Studies that were performed in specific subgroups of ICU-patients, such as neurosurgical patients, liver transplant patients, burn patients, trauma patients, patients with severe pancreatitis, and patients after open-heart surgery, after gastrectomy or after oesophageal resection, were excluded. We also excluded studies of SDD in the pediatric ICU setting. We subsequently focused on mortality and pneumonia, antimicrobial resistance, and costs. This left us with 20 publications on trials (Table 2), and 15 meta-analyses (Table 3). addition, our search yielded several publications dealing with antimicrobial resistance (Table 4) and costs of SDD, respectively.

Table 2.

Incidence and relative risks of pneumonia and mortality in trials of SDD in mixed medical-surgical ICUs.

| Publication | Year | N | Incidence of pneumonia (%) | ICU Mortality (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SDD versus control (RR [95% confidence interval]) | ||||

| Ledingham [20] | 1988 | 324 | 3 versus 9%, P = .006 | 24 versus 24%, ns |

| Ulrich [4] | 1989 | 100 | 6 versus 44%, P < .00001 | 31 versus 54%, P < .02 |

| (0.28 [0.13–0.59]) | (0.69 [0.47–1.02]) | |||

| Godard [21] | 1990 | 181 | 2 versus 15%, P < .05 | 12 versus 18%, ns |

| McClelland [22] | 1990 | 27 | 7 versus 50%, P < .05 | 60 versus 58%, ns |

| Aerdts [23] | 1991 | 56 | 6 versus 62%, P = .0001 | 12 versus 10%, ns |

| (0.09 [0.01–0.60]) | (0,71 [0.25–2.02]) | |||

| Blair [24] | 1991 | 256 | 48 versus 82%, P = .002 | 15 versus 19%, ns |

| (0.33 [0.18–0.62]) | (0.17 [0.49 – 1.28]) | |||

| Finch [25] | 1991 | 49 | 0.69 [0.23–2.01], ns | 1.56 [0.88–2.77], ns |

| Gaussorgues [26] | 1991 | 118 | N.A. | 1.00 [0.69–1.44], ns |

| Cockerill [27] | 1992 | 150 | 5 versus 16%, P = .03 | 11 versus 19%, ns |

| 0.33 [0.11–0.99] | 0.69 [0.34–1.38] | |||

| Hammond [28] | 1992 | 239 | 26 versus 34%, P = .22 | 12 versus 12%, ns |

| 0.82 [0.51–1.34] | 1.08 [0.70–1.67] | |||

| Jacobs [29] | 1992 | 91 | 0 versus 9%, ns | 39 versus 53%, ns |

| 0.13 [0.02–0.95] | 0.62 [0.37–1.05] | |||

| Rocha [5] | 1992 | 101 | 15 versus 46%, P < .001 | 21 versus 44%, P < .05 |

| 0.32 [0.15–0.68] | 0.70 [0.49–1.02] | |||

| Winter [30] | 1992 | 183 | 3 versus 18%, P < .05 | 36 versus 43%, ns |

| 0.18 [0.05–0.59] | 0.83 [0.58–1.19] | |||

| Ferrer [31] | 1994 | 80 | 18 versus 24%, ns | 31 versus 27%, ns |

| 0.70 [0.33–1.46] | 1.21 [0.63–2.34] | |||

| Palomar [32] | 1997 | 129 | 17 versus 50%, P = .005 | 24 versus 31%, ns |

| 0,39 [0,21–0,73] | 0,98 [0,52–1,84] | |||

| Verwaest [33] | 1997 | 440 | 9 versus 18%, P = .026 | 18 versus 17%, ns |

| 0.53 [0.34–0.89] | 1,17 [0.81–1.71] | |||

| Sánchez-García [34] | 1998 | 271 | 11 versus 29%, P < .001 | 39 versus 47%, ns |

| 0.57 [0.40–0.81] | 0.84 [0.63–1.11] | |||

| Parra Moreno [35] | 2002 | 306 | 5 versus 20%, P < , 0001 | N.A. |

| 0.30 [0.16–0.53] | ||||

| De Jonge [36] | 2003 | 934 | N.A. | 15 versus 23%, P = .002 |

| 0.65 [0.49–0.85] | ||||

| De Smet [37] | 2009 | 4035 | N.A. | 3.5% points absolute reduction, P = .02 |

| 0.81 [0.69–0.94] | ||||

N: number of patients; ns: not significant; N.A.: not available.

Table 3.

Odds ratios for pneumonia and mortality in meta-analyses of trials of SDD.

| Publication | Year | n/N | Pneumonia | Mortality |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR [95% confidence interval] | ||||

| Van den Broucke-Grauls [38] | 1991 | 6/491 | 0.12 [0.08–0.19] | 0.70 [0.45–1.09] |

| SDD Group [39] | 1993 | 22/4142 | 0,37 [0.31–0.43] | 0.90 [0.79–1.04] |

| Heyland [40] | 1994 | 24/3312 | 0.46 [0.39–0.56] | 0.87 [0,79–0.97] |

| Kollef [41] | 1994 | 16/2270 | 0.15 [0.12–0.17] | 0.02 [−0.02–0.05] |

| Hurley [42] | 1995 | 26/3768 | 0.35 [0.30–0.42] | 0.86 [0.74–0.99] |

| D'Amico [43] | 1998 | 16/3361 | 0.35 [0.29–0.41] | 0.80 [0.69–0.93] |

| 1999 | 21/N.A. | N.A. | 0.70 [0.52–0.93]a | |

| Nathens [44] | 0.91 [0.71–1.18]b | |||

| Liberati [45] | 2000 | 16/3361 | 0.35 [0,29–0.41] | 0.80 [0.69–0.93] |

| Redman [46] | 2001 | N.A. | 0.36 [0.28–0.46] | N.A. |

| Liberati [47] | 2004 | 36/6922 | 0.35 [0.29–0.41] | 0.78 [0.68–0.89] |

| Silvestri [48] | 2007 | 51/8065 | N.A. | 0.80 [0.69–0.94] |

| Silvestri [49] | 2008 | 54/9473 | 0.11 [0.06–0.20] | N.A. |

| Silvestri [50] | 2009 | 21/4902 | N.A. | 0.71 [0.61–0.82] |

| Liberati [51] | 2009 | 36/6914 | 0.28 [0.20–0.38] | 0.75 [0.65–0.87] |

asurgical patients; bmedical patients; n/N: number of trails/patients; OR: odds ratio; N.A.: not available.

Table 4.

SDD and the emergence of antimicrobial resistance, in areas with high and low endemicity.

| Endemicity | Main findings |

|---|---|

| MRSA | |

| High | Increase of colonization with MRSA [28, 31, 33, 52–55] |

| Low | No increase of colonization with MRSA [36, 56, 57] |

|

| |

| VRE | |

| High | No increase of VRE infection rates [58, 59]; no increase of VRE infection rates when enteral vancomycin is added [26, 56, 60–64] |

| Low | No increase of VRE carriage [36]; increase of VRE isolates [57] |

|

| |

| AGNB | |

| High | Decrease of multiresistant AGNB [54, 65]; lower incidence of carriage and infections with antibiotic resistant Gram-negative bacteria [36, 66–69]; no increase in prevalence of beta lactam- or aminoglycoside-resistant Gram-negative rods [57, 70]; increased antimicrobial resistance [5, 33, 71] |

| Low | Increased intestinal colonization with Gram-negative bacteria resistant to ceftazidime, tobramycin, or ciprofloxacin—discontinuation of SDD results in a rebound effect of ceftazidime resistant bacteria in the intestinal tract [72]; SDD increased the number of infections caused by multiresistant bacteria [73] |

MRSA: methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, VRE: vancomycin-resistant Enterococci and AGNB: aerobic Gram-negative bacteria.

4.3. Study Heterogeneity

Although we focused on trials applying the classical 4-component SDD, studies remained heterogenic.

Different methods of randomization were used, for example inclusion per time period or per ICU. There was also great variation in the number of patients included in the retrieved trials.

Second, there was great diversity in used prophylactic antimicrobials. In the original design, SDD consisted of locally applied polymyxin E, tobramycin, and amphotericin B plus systemically applied cefotaxim [74]. In one trial locally applied amphotericin B was replaced by nystatin [27]. In other trials tobramyein was replaced by a quinolone [4, 23, 75], gentamicin [66, 76], or neomycin [27, 34]. In many trials, cefotaxim was replaced by another antimicrobial, such as ceftazidime [30], ceftriaxone [77], ciprofloxacin [56, 75], ofloxacin [33], or trimethoprim [4].

Third, criteria for pneumonia were very diverse. Indeed, clinical, radiological, and microbial criteria versus bronchoscopic techniques with quantitative cultures were used. Consequently, the incidence of VAP ranged from as low as less than 10% to as high as 85%. Also, great variation in the mortality of the control group was seen in the different trials, making comparison of studies more difficult.

5. The Effect of SDD on the Incidence of Pneumonia and Mortality

With the exception of 3 trials [25, 28, 31], a reduction of the incidence of pneumonia was seen with the use of SDD (Table 2). Reductions were larger in trials that used more loose criteria for pneumonia. It can be argued that in trials that used only clinical and/or radiologic criteria with or without positive cultures of tracheal secretions the reduction in respiratory tract infections was in fact a reduction in purulent bronchitis and not a reduction in pneumonia per se [3]. All meta-analyses demonstrated a reduction of the incidence of pneumonia with the use of SDD (Table 3).

There were only 2 small studies that demonstrated a reduction of mortality with the use of SDD [4, 5]. Notably, most studies were too small to show a significant effect of SDD on mortality (Table 2). Two recently published well-powered trials also show SDD to reduce mortality of ICU patients [36, 37]. With the exception of 1 meta-analysis [38], reduced mortality rates of ICU patients were seen with the use of SDD (Table 3).

6. Effects of SDD on Microbial Resistance

One concern with prophylactic use of antimicrobial agents is the risk of the emergence of resistant pathogens [78, 79]. Notably, in most trials colonization with resistant bacteria or an increase of superinfections was not reported (Table 4). One trial that specifically addressed the issue of microbial resistance found that resistance rates were actually higher in the control population than in the SDD-treated population [36]. In addition, a reduction in the incidence of multiresistant Klebsiella spp. with SDD use was seen in 3 other trials [65, 80, 81].

However, more recently it was shown that SDD was associated with a gradual increase of rates of ceftazidime-resistant Gram-negative bacteria in the respiratory tract [72]. The rate of resistant Gram-negative bacteria in the gastrointestinal tract significantly increased after discontinuation of SDD [72].

SDD may promote colonization with Gram-positive bacteria. The rate of colonization with Gram-positive strains was significantly higher, and more cases of Gram-positive bacteremia occurred in SDD-treated patients [33, 34].

Two meta-analyses showed that resistance against SDD antimicrobials is not emerging with long-term use [43, 50]. Use of SDD was even associated with a lower rate of colonization as well as infection with resistant Gram-negative bacteria [34, 65, 82].

Additional research is mandatory to determine whether SDD is a safe strategy with respect to the risk of emergence of antimicrobial resistance, especially in countries with higher endemicity of multidrug-resistant pathogens, because with the available evidence this risk cannot completely be denied.

7. Costs of SDD

Several studies compared costs of antimicrobial therapies between the SDD strategy and the control strategy, though in all these trials cost was only a secondary endpoint.

Costs have been calculated in different ways. One trial showed no differences in costs between the SDD strategy and the control strategy [67]. Studies that used cefotaxime showed a reduction of costs. Two other trials, however, showed higher costs with SDD when a quinolone was given for systemic prophylaxis [33, 75].

Four trials analyzed total ICU costs per survivor [5, 61, 77, 83]. These trials showed a reduction of costs with the use of SDD, which was the result of reductions in length of stay and reduced use of systemic antibiotics.

8. Discussion

The findings of our review of the literature can be summarized as follows: (I) numerous trials of SDD show a reduction of the incidence of pneumonia with this preventive strategy, (II) well-powered trials of SDD show a reduction of mortality with SDD, (III) although SDD is associated with induction of antimicrobial resistance in some studies, it certainly was not a problem in all trials, and (IV) SDD seems to be a cost-effective strategy.

Preventive measures against pneumonia in critically ill patients include, but may not be restricted to, early weaning from mechanical ventilation, hand hygiene, aspiration precautions, and prevention of contamination—at times summarized with the acronym “WHAP” [84]. It has been demonstrated that an educational initiative on WHAP, directed at respiratory care practitioners and ICU-nurses, was associated with decreases in VAP incidence rates of up to 61% [84]. One of the problems with the interpretation of the trials of SDD is that it is uncertain whether the caregivers complied with these prevention strategies. Indeed, only “high levels of hygiene” is a component of SDD.

Interpretation and comparison of the results of trials of SDD are complicated by the many dissimilarities amongst SDD regimens that were applied. We tried to solve this issue by focusing on studies that investigated the effect of the classical SDD regimen, applying all 4 components thought to be important for its efficacy [18]. Nevertheless, large differences remained present. Interpretation and comparison of the results of trials of SDD are also complicated by the difference in quality of the individual studies. For instance, large variation in the incidence of pneumonia was seen, due to difference in the way pneumonia was diagnosed. The incidence of pneumonia in studies that used bronchoscopic techniques with quantitative cultures was half of that in studies made the diagnosis of pneumonia on clinical and radiological criteria. Nevertheless, since all studies showed a positive effect of SDD with respect to the rate of pneumonia, we consider the evidence for SDD as an effective prophylactic strategy sufficient. Thereby it can be questioned if it is necessary to give the “full” protocol, with intestinal decontamination and systemic cefotaxime. In the light of the recently published work by de Smet et al. the role of intestinal decontamination and of systemic cefotaxime seems to be questionable [37].

The fast majority of trials of SDD showed no effect on mortality. It should be noted, however, that most studies were underpowered to show any effect on mortality. The last 2 trials of SDD, however, were adequately powered [36, 37]. Since these 2 trials showed SDD to reduce mortality of ICU patients, we also consider the evidence for SDD as a life-saving strategy sufficient.

It can be questioned if SDD should be given to all ICU patients or restricted to selected groups. We have solely focused on the effect of SDD in patients in mixed medical-surgical ICUs.

The emergence of antimicrobial resistance with SDD has been the subject of numerous hot debates [85–87]. It has been argued that the use of SDD would promote the growth of resistant bacteria. In theory, this is a potential adverse effect of SDD treatment, but in low antibiotic resistance endemic areas this seems not to be a problem. The 2 trials that investigated resistance were performed in The Netherlands, a country with the lowest use of outpatient antibiotics, generally a narrower spectrum antibiotic for hospitalized patients, a low incidence of methicillin-resistant S. aureus, vancomycin-resistant Enterococci (VRE) other multidrug-resistant pathogens, and extended spectrum bèta-lactamase (ESBL) producing pathogens [88, 89]. This situation is markedly different from other centers across the world.

Because SDD is not active against resistant Gram-positive bacteria, it may promote colonization with bacteria such as S. Aureus, and E. faecalis and it can lead to infections with these bacteria in critically ill patients [90–92]. Patients' illness causes conversion of carriage of normal to abnormal flora. Most ICU patients have bacterial overgrowth. The increased spontaneous mutations lead to polyclonality and antimicrobial resistance [93]. In this way, treatment with SDD could promote gut overgrowth of intrinsically resistant bacteria, such as MRSA and VRE, although with endemicity no increase has been found [36, 94, 95]. However, it cannot be excluded that in countries where VRE is endemic, SDD can have a negative effect on VRE. On the other hand, the reduced prescription of systemic-broad spectrum antibiotics in SDD-treated patients may also lead to decreased incidence of VRE. Although SDD does exert selection pressure on plasmid-mediated ESBL, emergence of ESBL-producing bacteria due to SDD has not been found.

SDD seems a safe strategy with regard to the emergence of antibiotic resistance in low antibiotic resistance endemic areas, but with the available evidence, we cannot say that SDD is also a safe strategy in high endemicity areas. We should consider giving SDD only in low endemic areas till results in high endemic areas are available. Additional research is also mandatory to determine what to do when resistant pathogens do emerge.

Another concern with SDD is the cost associated with this preventive strategy. Costs of SDD have been calculated in several studies, but most of these were not designed to analyze cost-effectiveness. The absence of studies on costs and cost-effectiveness is remarkable. It could be that a proper economic analysis in the ICU setting is difficult to perform, because it is hard to quantify the relative contribution of a single strategy. For example, the price of intravenous antibiotics can vary widely between hospitals, because the price is dependent on negotiations between local pharmacy and manufacturers.

The most important cost component associated with SDD is the cost of antibiotics. As the aim of SDD is to reduce in ICU infections, including pneumonia, a reduction in total antibiotic use can be expected. Overall hospital costs may be lower, in part due to the decrease rate of pneumonia. Development of pneumonia is associated with up to 5 extra days of ICU treatment. Prevention of pneumonia substantially decreases the length of ICU stay and thus reduces costs per patient.

9. Conclusion

Numerous randomized controlled trials have shown that SDD reduces the incidence of pneumonia. Two recently published well-powered trials also show SDD to reduce mortality of ICU patients. SDD can be associated with induction of antimicrobial resistance, but this seems not to be a clinical problem, at least not in countries with low endemicity. Finally, SDD seems to be a cost-effective strategy. Based on these findings, we favor the use of SDD in ICU patients.

References

- 1.Marshall JC. Gastrointestinal flora and its alterations in critical illness. Current Opinion in Clinical Nutrition and Metabolic Care. 1999;2(5):405–411. doi: 10.1097/00075197-199909000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.du Moulin GC, Paterson DG, Hedley-Whyte J, Lisbon A. Aspiration of gastric bacteria in antacid-treated patients: a frequent cause of postoperative colonisation of the airway. Lancet. 1982;1(8266):242–245. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(82)90974-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schultz MJ, de Jonge E, Kesecioglu J. Selective decontamination of the digestive tract reduces mortality in critically ill patients. Critical Care. 2003;7(2):107–110. doi: 10.1186/cc1873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ulrich C, Harinck-de Weerd JE, Bakker NC, Jacz K, Doornbos L, de Ridder VA. Selective decontamination of the digestive tract with norfloxacin in the prevention of ICU-acquired infections: a prospective randomized study. Intensive Care Medicine. 1989;15(7):424–431. doi: 10.1007/BF00255597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rocha LA, Martin MJ, Pita S, et al. Prevention of nosocomial infection in critically ill patients by selective decontamination of the digestive tract. A randomized, double blind, placebo-controlled study. Intensive Care Medicine. 1992;18(7):398–404. doi: 10.1007/BF01694341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burke JP. Infection control—a problem for patient safety. New England Journal of Medicine. 2003;348(7):651–656. doi: 10.1056/NEJMhpr020557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hugonnet S, Uçkay I, Pittet D. Staffing level: a determinant of late-onset ventilator-associated pneumonia. Critical Care. 2007;11(4, article R80) doi: 10.1186/cc5974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vincent J-L, Rello J, Marshall J, et al. International study of the prevalence and outcomes of infection in intensive care units. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2009;302(21):2323–2329. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vincent J-L. Nosocomial infections in adult intensive-care units. Lancet. 2003;361(9374):2068–2077. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13644-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heyland DK, Cook DJ, Griffith L, Keenan SP, Brun-Buisson C. The attributable morbidity and mortality of ventilator-associated pneumonia in the critically ill patient. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 1999;159(4):1249–1256. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.159.4.9807050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Safdar N, Abad C. Educational interventions for prevention of healthcare-associated infection: a systematic review. Critical Care Medicine. 2008;36(3):933–940. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0B013E318165FAF3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cook DJ. Ventilator associated pneumonia: perspectives on the burden of illness. Intensive Care Medicine. 2000;26(1):S31–S37. doi: 10.1007/s001340051116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ylipalosaari P, Ala-Kokko TI, Laurila J, Ohtonen P, Syrjälä H. Intensive care unit acquired infection has no impact on long-term survival or quality of life: a prospective cohort study. Critical Care. 2007;11(2, article R35) doi: 10.1186/cc5718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Safdar N, Dezfulian C, Collard HR, Saint S. Clinical and economic consequences of ventilator-associated pneumonia: a systematic review. Critical Care Medicine. 2005;33(10):2184–2202. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000181731.53912.d9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Van Saene HKF, Damjanovic V, Murray AE, de la Cal MA. How to classify infections in intensive care units—the carrier state, a criterion whose time has come? Journal of Hospital Infection. 1996;33(1):1–12. doi: 10.1016/s0195-6701(96)90025-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leonard EM, van Saene HKF, Shears P, Walker J, Tam PKH. Pathogenesis of colonization and infection in a neonatal surgical unit. Critical Care Medicine. 1990;18(3):264–269. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199003000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van der Waaij D, Berghuis-de Vries JM, van der Lekkerkerk-Wees JE. Colonization resistance of the digestive tract in conventional and antibiotic-treated mice. Journal of Hygiene. 1971;69(3):405–411. doi: 10.1017/s0022172400021653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sleijfer DTh, Mulder NH, de Vries-Hospers HG, et al. Infection prevention in granulocytopenic patients by selective decontamination of the digestive tract. European Journal of Cancer and Clinical Oncology. 1980;16(6):859–869. doi: 10.1016/0014-2964(80)90140-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rommes JH, Zandstra DF, van Saene HKF. Selective digestive decontamination reduces mortality among intensive care patients. Nederlands Tijdschrift voor Geneeskunde. 1999;143(12):602–605. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ledingham IM, Alcock SR, Eastaway AT, McDonald JC, McKay IC, Ramsay G. Triple regimen of selective decontamination of the digestive tract, systemic cefotaxime, and microbiological surveillance for prevention of acquired infection in intensive care. Lancet. 1988;1(8589):785–790. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(88)91656-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Godard J, Guillaume C, Reverdy M-E, et al. Intestinal decontamination in a polyvalent ICU. A double-blind study. Intensive Care Medicine. 1990;16(5):307–311. doi: 10.1007/BF01706355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McClelland P, Murray AE, Williams PS, et al. Reducing sepsis in severe combined acute renal and respiratory failure by selective decontamination of the digestive tract. Critical Care Medicine. 1990;18(9):935–939. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199009000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aerdts SJA, van Dalen R, Clasener HAL, Festen J, van Lier HJJ, Vollaard EJ. Antibiotic prophylaxis of respiratory tract infection in mechanically ventilated patients; a prospective, blinded, randomized trial of the effect of a novel regimen. Chest. 1991;100(3):783–791. doi: 10.1378/chest.100.3.783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blair P, Rowlands BJ, Lowry K, Webb H, Armstrong P, Smilie J. Selective decontamination of the digestive tract: a stratified, randomized, prospective study in a mixed intensive care unit. Surgery. 1991;110(2):303–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Finch RG, Romlinson P, Holliday M. Selective decontamination of the digestive tract (SDD) in the prevention of secondary sepsis in a medical/surgical intensive care unit. In: Proceedings of the 17th Congress of Chemotherapy; 1991; Berlin, Germany. abstract 471. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gaussorgues P, Salord M, Sirodot S, et al. Efficiency of selective decontamination of the digestive tract on the occurence of nosocomial bacteremia in patients on mechanical ventilation receiving betamimetic therapy. Réanimation, Soins Intensifs, Médecine d'Urgence. 1991;7:169–174. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cockerill FR, III, Muller SR, Anhalt JP, et al. Prevention of infection in critically ill patients by selective decontamination of the digestive tract. Annals of Internal Medicine. 1992;117(7):545–553. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-117-7-545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hammond JMJ, Potgieter PD, Saunders GL, Forder AA. Double-blind study of selective decontamination of the digestive tract in intensive care. Lancet. 1992;340(8810):5–9. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)92422-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jacobs S, Foweraker JE, Roberts SE. Effectiveness of selective decontamination of the digestive tract (SDD) in an ICU with a policy encouraging a low gastric pH. Clinical Intensive Care. 1992;3(1):52–58. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Winter R, Humphreys H, Pick A, MacGowan AP, Willatts SM, Speller DCE. A controlled trial of selective decontamination of the digestive tract in intensive care and its effect on nosocomial infection. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 1992;30(1):73–87. doi: 10.1093/jac/30.1.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ferrer M, Torres A, González J, et al. Utility of selective digestive decontamination in mechanically ventilated patients. Annals of Internal Medicine. 1994;120(5):389–395. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-120-5-199403010-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Palomar M, Alvarez-Lerma F, Jorda R, Bermejo B. Prevention of nosocomial infection in mechanically ventilated patients: Selective digestive decontamination versus sucralfate. Clinical Intensive Care. 1997;8(5):228–235. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Verwaest C, Verhaegen J, Ferdinande P, et al. Randomized, controlled trial of selective digestive decontamination in 600 mechanically ventilated patients in a multidisciplinary intensive care unit. Critical Care Medicine. 1997;25(1):63–71. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199701000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sánchez García M, Cambronero Galache JA, López Diaz J, et al. Effectiveness and cost of selective decontamination of the digestive tract in critically III intubated patients: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter trial. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 1998;158(3):908–916. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.158.3.9712079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Parra Moreno ML, Arias Rivera S, de La Cal López MÁ, et al. Effect of selective digestive decontamination on the nosocomial infection and multiresistant microorganisms incidence in critically ill patients. Medicina Clinica. 2002;118(10):361–364. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.de Jonge E, Schultz MJ, Spanjaard L, et al. Effects of selective decontamination of digestive tract on mortality and acquisition of resistant bacteria in intensive care: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2003;362(9389):1011–1016. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14409-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.de Smet AMGA, Kluytmans JAJW, Cooper BS, et al. Decontamination of the digestive tract and oropharynx in ICU patients. New England Journal of Medicine. 2009;360(1):20–31. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0800394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vandenbroucke-Grauls CMJE, Vandenbroucke JP. Effect of selective decontamination of the digestive tract on respiratory tract infections and mortality in the intensive care unit. Lancet. 1991;338(8771):859–862. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)91510-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Aerdts SJA, Clasener HAL, Blair PHB, et al. Meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials of selective decontamination of the digestive tract. selective decontamination of the digestive tract. British Medical Journal. 1993;307(6903):525–532. doi: 10.1136/bmj.307.6903.525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Heyland DK, Cook DJ, Jaeschke R, Griffith L, Lee HN, Guyatt GH. Selective decontamination of the digestive tract: an overview. Chest. 1994;105(4):1221–1229. doi: 10.1378/chest.105.4.1221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kollef MH. The role of selective digestive tract decontamination on mortality and respiratory tract infections: a meta-analysis. Chest. 1994;105(4):1101–1108. doi: 10.1378/chest.105.4.1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hurley JC. Prophylaxis with enteral antibiotics in ventilated patients: selective decontamination or selective cross-infection? Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 1995;39(4):941–947. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.4.941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.D’Amico R, Pifferi S, Leonetti C, Torri V, Tinazzi A, Liberati A. Effectiveness of antibiotic prophylaxis in critically ill adult patients: systematic review of randomised controlled trials. British Medical Journal. 1998;316(7140):1275–1285. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7140.1275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nathens AB, Marshall JC. Selective decontamination of the digestive tract in surgical patients: a systematic review of the evidence. Archives of Surgery. 1999;134(2):170–176. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.134.2.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liberati A, D’Amico R, Pifferi S, Telaro E. Antibiotic prophylaxis in intensive care units: meta-analyses versus clinical practice. Intensive Care Medicine. 2000;26(1):S38–S44. doi: 10.1007/s001340051117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Redman R, Ludington E, Crocker M, et al. Analysis of respiratory and non-respiratory infections in published trials of selective digestive decontamination. Intensive Care Medicine. 2001;27(supplement 1):p. S285. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liberati A, D’Amico R, Pifferi S, Torri V, Brazzi L. Antibiotic prophylaxis to reduce respiratory tract infections and mortality in adults receiving intensive care. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2004;(1) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000022.pub2. Article ID CD000022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Silvestri L, van Saene HKF, Milanese M, Gregori D, Gullo A. Selective decontamination of the digestive tract reduces bacterial bloodstream infection and mortality in critically ill patients. Systematic review of randomized, controlled trials. Journal of Hospital Infection. 2007;65(3):187–203. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2006.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Silvestri L, van Saene HKF, Casarin A, Berlot G, Gullo A. Impact of selective decontamination of the digestive tract on carriage and infection due to Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria: a systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Anaesthesia and Intensive Care. 2008;36(3):324–338. doi: 10.1177/0310057X0803600304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Silvestri L, van Saene HKF, Weir I, Gullo A. Survival benefit of the full selective digestive decontamination regimen. Journal of Critical Care. 2009;24(3):474.e7–474.e14. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2008.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Liberati A, D’Amico R, Pifferi S, Torri V, Brazzi L. Antibiotic prophylaxis to reduce respiratory tract infections and mortality in adults receiving intensive care. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2009;(4) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000022.pub3. Article ID CD000022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gastinne H. Selective digestive decontamination, effects onepidemiology andbacterial resistances. Practical considerations. Reanimation. 2007;16(3):250–255. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wiener J, Itokazu G, Nathan C, Kabins SA, Weinstein RA. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of selective digestive decontamination in a medical-surgical intensive care unit. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 1995;20(4):861–867. doi: 10.1093/clinids/20.4.861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lingnau W, Berger J, Javorsky F, Fille M, Allerberger F, Benzer H. Changing bacterial ecology during a five year period of selective intestinal decontamination. Journal of Hospital Infection. 1998;39(3):195–206. doi: 10.1016/s0195-6701(98)90258-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.de la Cal MA, Cerdá E, van Saene HKF, et al. Effectiveness and safety of enteral vancomycin to control endemicity of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in a medical/surgical intensive care unit. Journal of Hospital Infection. 2004;56(3):175–183. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2003.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Krueger WA, Lenhart F-P, Neeser G, et al. Influence of combined intravenous and topical antibiotic prophylaxis on the incidence of infections, organ dysfunctions, and mortality in critically III surgical patients: a prospective, stratified, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2002;166(8):1029–1037. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2105141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Heininger A, Meyer E, Schwab F, Marschal M, Unertl K, Krueger WA. Effects of long-term routine use of selective digestive decontamination on antimicrobial resistance. Intensive Care Medicine. 2006;32(10):1569–1576. doi: 10.1007/s00134-006-0304-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Arnow PM, Carandang GC, Zabner R, Irwin ME. Randomized controlled trial of selective bowel decontamination for prevention of infections following liver transplantation. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 1996;22(6):997–1003. doi: 10.1093/clinids/22.6.997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hellinger WC, Yao JD, Alvarez S, et al. A randomized, prospective, double-blinded evaluation of selective bowel decontamination in liver transplantation. Transplantation. 2002;73(12):1904–1909. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200206270-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bergmans DCJJ, Bonten MJM, Gaillard CA, et al. Prevention of ventilator-associated pneumonia by oral decontamination: a prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2001;164(3):382–388. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.164.3.2005003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Korinek AM, Laisne MJ, Nicolas MH, Raskine L, Deroin V, Sanson-Lepors MJ. Selective decontamination of the digestive tract in neurosurgical intensive care unit patients: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study. Critical Care Medicine. 1993;21(10):1466–1473. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199310000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Korinek AM. Ecological impact of preventive antibiotherapy. Annales Francaises d’Anesthesie et de Reanimation. 2000;19(5):418–423. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pugin J, Auckenthaler R, Lew DP, Suter PM. Oropharyngeal decontamination decreases incidence of ventilator-associated pneumonia: a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind clinical trial. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1991;265(20):2704–2710. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Schardey HM, Joosten U, Finks U, et al. The prevention of anastomotic leakage after total gastrectomy with local decontamination: a prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled multicenter trial. Annals of Surgery. 1997;225(2):172–180. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199702000-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Brun-Buisson C, Legrand P, Rauss A, et al. Intestinal decontamination for control of nosocomial multiresistant gram-negative bacilli. Study of an outbreak in an intensive care unit. Annals of Internal Medicine. 1989;110(11):873–881. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-110-11-873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Unertl K, Ruckdeschel G, Selbmann HK, et al. Prevention of colonization and respiratory infections in long-term ventilated patients by local antimicrobial prophylaxis. Intensive Care Medicine. 1987;13(2):106–113. doi: 10.1007/BF00254795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.van der Voort PHJ, van Roon EN, Kampinga GA, et al. A before-after study of multi-resistance and cost of selective decontamination of the digestive tract. Infection. 2004;32(5):271–277. doi: 10.1007/s15010-004-3170-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Leone M, Albanese J, Antonini F, Nguyen-Michel A, Martin C. Long-term (6-year) effect of selective digestive decontamination on antimicrobial resistance in intensive care, multiple-trauma patients. Critical Care Medicine. 2003;31(8):2090–2095. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000079606.16776.C5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Saunders GL, Hammond JMJ, Potgieter PD, Plumb HA, Forder AA. Microbiological surveillance during selective decontamination of the digestive tract (SDD) Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 1994;34(4):529–544. doi: 10.1093/jac/34.4.529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Krueger WA, Heininger A, Unertl KE. Selective digestive tract decontamination in intensive care medicine. Fundamentals and current evaluation. Anaesthesist. 2003;52(2):142–152. doi: 10.1007/s00101-002-0443-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Rocha LA, Martin MJ, Pita S, et al. Prevention of nosocomial infection in critically ill patients by selective decontamination of the digestive tract. A randomized, double blind, placebo-controlled study. Intensive Care Medicine. 1992;18(7):398–404. doi: 10.1007/BF01694341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Oostdijk EAN, de Smet AMGA, Blok HEM, et al. Ecological effects of selective decontamination on resistant gram-negative bacterial colonization. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2010;181(5):452–457. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200908-1210OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hammond JMJ, Potgieter PD. Long-term effects of selective decontamination on antimicrobial resistance. Critical Care Medicine. 1995;23(4):637–645. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199504000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Stoutenbeek CP, van Saene HKF, Miranda DR, Zandstra DF. A new technique of infection prevention in the intensive care unit by selective decontamination of the digestive tract. Acta Anaesthesiologica Belgica. 1983;34(3):209–221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lingnau W, Berger J, Javorsky F, Lejeune P, Mutz N, Benzer H. Selective intestinal decontamination in multiple trauma patients: prospective, controlled trial. Journal of Trauma. 1997;42(4):687–694. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199704000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Flaherty J, Nathan C, Kabins SA, Weinstein RA. Pilot trial of selective decontamination for prevention of bacterial infection in an intensive care unit. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 1990;162(6):1393–1397. doi: 10.1093/infdis/162.6.1393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Sánchez García M, Cambronero Galache JA, López Diaz J, et al. Effectiveness and cost of selective decontamination of the digestive tract in critically III intubated patients: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter trial. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 1998;158(3):908–916. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.158.3.9712079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Salgado CD, O’Grady N, Farr BM. Prevention and control of antimicrobial-resistant infections in intensive care patients. Critical Care Medicine. 2005;33(10):2373–2382. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000181727.04501.f3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Bastin AJ, Ryanna KB. Use of selective decontamination of the digestive tract in United Kingdom intensive care units. Anaesthesia. 2009;64(1):46–49. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2008.05676.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Taylor ME, Oppenheim BA. Selective decontamination of the gastrointestinal tract as an infection control measure. Journal of Hospital Infection. 1991;17(4):271–278. doi: 10.1016/0195-6701(91)90271-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Brun-Buisson C, van Saene HKF. SDD and the novel extended-broad-spectrum β-lactamases. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 1991;28(1):145–147. doi: 10.1093/jac/28.1.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.de Jonge E. Effects of selective decontamination of digestive tract on mortality and antibiotic resistance in the intensive-care unit. Current Opinion in Critical Care. 2005;11(2):144–149. doi: 10.1097/01.ccx.0000155352.01489.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Stoutenbeek CP, Saene HKF, Zandstra DF. Prevention of multiple organ system failure by selective decontamination of the digestive tract in multiple trauma patients. In: Faist E, Baue AE, Schildberg FW, editors. The Immune Consequences of Trauma, Shock and Sepsis. Lengerich, Germany: Pabst Science; 1996. pp. 1055–1066. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Babcock HM, Zack JE, Garrison T, et al. An educational intervention to reduce ventilator-associated pneumonia in an integrated health system: a comparison of effects. Chest. 2004;125(6):2224–2231. doi: 10.1378/chest.125.6.2224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Bonten MJM, Krueger WA. Selective decontamination of the digestive tract: cumulating evidence, at last? Seminars in Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2006;27(1):18–22. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-933669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Silvestri L, van Saene HKF. Selective decontamination of the digestive tract does not increase resistance in critically ill patients: evidence from randomized controlled trials. Critical Care Medicine. 2006;34(7):2027–2030. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000226400.53640.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Wunderink RG. Welkommen to our world: emergence of antibiotic resistance with selective decontamination of the digestive tract. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2010;181(5):426–427. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200912-1821ED. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Goossens H, Ferech M, Vander Stichele R, et al. Outpatient antibiotic use in Europe and association with resistance: a cross-national database study. Lancet. 2005;365(9459):579–587. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17907-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Cantón R, Novais A, Valverde A, et al. Prevalence and spread of extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in Europe. Clinical Microbiology and Infection. 2008;14(1):144–153. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2007.01850.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kaufhold A, Behrendt W, Krauss T, van Saene H. Selective decontamination of the digestive tract and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Lancet. 1992;339(8806):1411–1412. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Bonten MJM, Gaillard CA, van Tiel FH, van der Geest S, Stobberingh EE. Colonization and infection with Enterococcus faecalis in intensive care units: the role of antimicrobial agents. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 1995;39(12):2783–2786. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.12.2783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Sijpkens YWJ, Buurke EJ, Ulrich C, van Asselt GJ. Enterococcus faecalis colonisation and endocarditis in five intensive care patients as late sequelae of selective decontamination. Intensive Care Medicine. 1995;21(3):231–234. doi: 10.1007/BF01701478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Damjanovic V, van Saene HKF. Microbial mutation as a source of polyclonality in the gut of the critically ill. Journal of Hospital Infection. 2005;59(4):374–375. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2004.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Krueger WA. Selective digestive decontamination. Journal fur Anasthesie und Intensivbehandlung. 2004;11(1):153–154. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Heininger A, Meyer E, Schwab F, Marschal M, Unertl K, Krueger WA. Effects of long-term routine use of selective digestive decontamination on antimicrobial resistance. Intensive Care Medicine. 2006;32(10):1569–1576. doi: 10.1007/s00134-006-0304-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]