Abstract

To test the differential susceptibility to parenting hypothesis, a 4-wave, randomized prevention design was used to examine the impact of the Strong African American Families (SAAF) program on past-month substance use across 29 months as a function of DRD4 genotype. Youths (N = 337; M age = 11.65 years) were assigned randomly to treatment condition. Those carrying a 7-repeat allele showed greater differential response to intervention vs. control than those with two 4-repeat alleles. Control youths but not treatment youths with a 7-repeat allele reported increases in past-month substance use across the 29-month study period, but this pattern did not emerge for those with the 4-repeat allele. Supporting the differential susceptibility to parenting hypothesis, the results suggest a greater preventive effect for youths carrying a 7-repeat allele, a role for DRD4 in the escalation of substance use during adolescence, and potential for an enhanced understanding of early-onset substance use.

Keywords: DRD4, parenting, substance use, susceptibility

Belsky & Pluess (2009) suggest that children with so-called “risk alleles,” i.e., genetic variations thought to be associated with adverse outcomes, may be more sensitive to the impact of parenting behavior than are children who do not have these alleles. Preliminary evidence with young children has lent considerable support to the hypothesis that variability at DRD4, a well-studied 48-base pair (bp) repeat in the coding region of the dopamine D4 receptor, may indeed contribute to differential susceptibility to parenting (Bakermans-Kranenburg, van IJzendoorn, Pijlman, Mesman, & Juffer, 2008; Bakermans-Kranenburg & van IJzendoorn, 2007; Belsky, Bakermans-Kranenburg & van IJzendoorn, 2007). Variation at DRD4 also has been studied as a risk factor for certain problems in childhood, including ADHD (Gizer, Ficks, & Waldman, 2009) and risk for substance use (e.g., Conner, Hellemann, Ritchie, & Noble, 2010). Based on the hypotheses that DRD4 would confer differential susceptibility to parenting influences in adolescence and that substance use would escalate during adolescence, we predicted genetic moderation of a parenting-based prevention program on substance use outcomes would emerge.

We used the Strong African American Families (SAAF) program as the parenting intervention. SAAF is designed to prevent a cluster of risk behaviors, including alcohol use, marijuana use, and binge drinking (Brody et al., 2004); these behaviors are known to lead to problematic outcomes in adolescence and adulthood (Brook & Newcomb, 1995; Choi, Gilpin, Farkas, & Pierce, 2001). SAAF has been shown to prevent early initiation of substance use (Brody, Murry, Gerrard, et al., 2006) and recently has been shown to interact with a genetic polymorphism in 5HTT, a 22-bp repeat element in the promoter region of that gene, in the prediction of risk behavior initiation (Brody, Beach, Philibert, Chen, & Murry, 2009; Brody, Beach, Philibert, Chen, Lei, et al., 2009). Several papers have documented the SAAF program’s mechanism of action and predictors of response (Beach et al., 2008; Brody, Murry, Gerrard et al., 2006; Brody, Murry, Kogan et al., 2006; Brody et al., 2005; Brody, Murry, Chen, Kogan, & Brown, 2006; Gerrard et al., 2006; Murry et al., 2005). None of these papers, however, addressed the potential role of DRD4 in moderating response to the intervention. In contrast to research on moderation of SAAF treatment effects by 5HTT, which focused on initiation of risky behavior, in this article we focus on escalation of substance use across adolescence.

A Brief Primer on Genotyping

The genetic code is composed of nucleotide base pairs (bps) that are organized into genes. Genes represent segments of the genome that contribute to particular phenotypes or functions. Alternative forms of genes, termed “alleles,” can be identified by examining specific locations within the gene. One type of genetic variation, produced by repeated sets of base pairs, is referred to as a Variable Number Tandem Repeat (VNTR). Both DRD4 and 5HTT contain well-characterized VNTRs. VNTRs may alter the product of the gene (as with DRD4) if they occur in the coding region (i.e. the Exon), or they may influence the amount of product produced (as with 5HTT) if they occur in a promoter region. Within the coding region every three base pairs codes for a particular amino acid.

DRD4

The 48-bp VNTR in DRD4 that we examined is a polymorphism in exon 3 that codes for a 16 amino acid insert in the dopamine D4 receptor. The VNTR contains 2 to 11 repeats, with the 4-repeat and 7-repeat alleles being most common. The 7-repeat allele functions in a way that yields a protein structure that produces less reactive D4 receptors in both in vitro and in vivo tests of responsiveness, resulting in weaker transmission of intracellular signals for those with the 7-repeat allele versus the 4-repeat allele (e.g., Levitan et al., 2006). It has been difficult to characterize fully the functional significance of the less common repeat alleles. Accordingly, in the current report we focus on contrasts between individuals with at least one 7-repeat allele versus those with two 4-repeat alleles.

5HTT

The serotonin transporter (5HTT) is a key regulator of serotonergic neurotransmission, localized to 17p13 and consisting of 14 exons and a single promoter. The 5HTTLPR (5HTT linked polymorphic region) is a well-explored genetic marker contributing to childhood temperament. Variation in the promoter region of the gene results in two main variants, a short and a long allele; presence of the short allele results in lower serotonin transporter availability. The short variant has 12 copies, and the long variant 14 copies, of a 22-bp repeat element. The short allele appears to exert a similar effect on temperament for both males and females (Munafo, Clark, & Flint, 2004). In the current report, we focus on contrasts between individuals with at least one short allele and those with no short alleles.

Why Should DRD4 Predict Escalation of Substance Use?

Individual differences in craving for substances may be important in predicting escalation of substance use, and considerable evidence indicates that one of the major neural substrates of craving is variation in the mesolimbic dopaminergic neurotransmission pathway (Berridge & Robinson, 1998; Wise, 1987). As noted previously, variation at DRD4 has been found to result in weaker transmission of intracellular signals for those with the 7-repeat allele relative to those with the 4-repeat allele, and the resulting hypodopaminergic functioning is associated with indicators of substance use in adolescents. For example, youths carrying at least one 7-repeat allele have been found to have higher lifetime rates of alcohol use (Conner et al., 2010; Laucht, Becker, Blomeyer, & Schmidt, 2007; Ray et al., 2008; Skowronek, Laucht, Hohm, Becker, & Schmidt, 2006; Vaughn, Beaver, DeLisi, Howard, & Perron, 2009) than do similar youths without a 7-repeat allele.

Why Examine the Interaction of SAAF and DRD4 in the Current Study?

Prior research suggests the potential importance of the DRD4 7-repeat allele in conferring susceptibility to parental influence early in childhood, and our own previous work has addressed the issues of genetic moderation with regard to initiation of risk behavior, including substance use. No studies, however, have been designed to determine whether the susceptibility to parental influence that DRD4 confers continues into adolescence and whether parenting continues to interact with the presence of the DRD4 7-repeat allele to predict escalation of substance use in late childhood and early adolescence. If variation in DRD4 is associated with both the attractiveness of certain risk activities and greater susceptibility to the impact of intervention-targeted parenting, a DRD4 × SAAF intervention interaction should emerge. Given prior work with 5HTT, we are interested in determining whether the impact of DRD4 is independent of the impact of 5HTT.

Hypotheses

The foregoing considerations lead to three specific hypotheses. First, we predicted that the intervention would yield similar outcomes for intervention-targeted parenting behavior regardless of youth genotype at DRD4 and that the SAAF program would work to alter intervention-targeted parenting behavior regardless of youth genotype. Second, we predicted that youths with one or two copies of the 7-repeat allele of DRD4 who were assigned randomly to the control condition would show greater increases in substance use over time than would youths with the same genotype who were assigned randomly to SAAF; this would not be true for youths with two copies of the 4-repeat allele. We further hypothesized that the differences would be due to differences in youth genotypes, not parental genotypes. In addition, we examined the exploratory hypothesis that parents with the DRD4 7-repeat allele might show less change in intervention-targeted parenting as a function of SAAF participation. Although this is not directly relevant to the differential susceptibility hypothesis, it is relevant to the broader issue of optimal construction of preventive intervention programs. The availability of parent genotypes provided an opportunity to explore this hypothesis. Given prior work indicating that youth 5HTT predicts differential initiation of risk behavior (Brody, Beach, Philibert, Chen, & Murry, 2009), we entered this genetic polymorphism into our analyses of youth susceptibility to the parenting intervention as a control variable.

Method

Data were collected as part of the evaluation of the SAAF family-based preventive intervention study. The data reported in this paper were collected from families randomly assigned to the prevention or control condition. Risk behaviors were assessed when the youths were 11 (pretest), 12 (posttest), 13 (follow-up) and 14 (long-term follow-up) years old. Data on intervention-targeted parenting practices were obtained at the posttest assessment; genetic data were obtained 2 years after the long-term follow-up assessment. All youths with at least one 7-repeat allele or two 4-repeat alleles who also had data for 5HTT (N = 337) were included in the analyses. We provide here a brief description of subject recruitment and enrollment, intervention implementation and fidelity, and data collection procedures; these procedures are described extensively in earlier reports on SAAF’s efficacy (Brody et al., 2004; Brody, Murry, Gerrard et al., 2006; Brody, Murry, Kogan et al., 2006).

Participants

Participants in the SAAF trial included 667 African American families who resided in rural Georgia. From each family, a youth who was 11 years old when recruited and the youth’s primary caregiver, typically the biological mother, provided data. Each family was paid $100 after each of the assessments.

The sample eligible for the present study included the 350 families randomly assigned to receive the SAAF intervention and the 291 randomly assigned to the control condition who completed the posttest; families assigned to SAAF were oversampled. Because only the 4-repeat and 7-repeat alleles are well characterized in terms of biological effects, only participants (N = 340) with these alleles were included in the analyses. Three additional participants were excluded because their data for 5HTT could not be characterized unambiguously.

Intervention Implementation and Fidelity

The SAAF prevention program consisted of seven consecutive meetings held at community facilities, with separate parent and youth skill-building curricula and a family curriculum. Each meeting included separate, concurrent training sessions for parents and youths followed by a joint parent-youth session during which the families practiced the skills they learned in their separate sessions. Concurrent and family sessions each lasted 1 hour; thus, parents and youths received 14 hours of prevention training. Additional details regarding the intervention can be found in Brody, Murry, Gerrard et al. (2006).

Procedure

To enhance rapport and cultural understanding, African American students and community members served as field researchers to collect pretest, posttest, and long-term follow-up data. During each wave of data collection, the field researchers, who were blind to the families’ group assignments, made one home visit lasting 2 hours to each family. Well-established procedures for the study of the development of risk behaviors were used, including computer-based interviewing, matching of researchers and participants by ethnicity, and reassurance concerning confidentiality of the data (Murry & Brody, 2004). Each interview was conducted privately, with no other family members present or able to overhear the conversation. Youths provided data on their own past-month substance use and caregivers provided data on their own intervention-targeted parenting practices. Genetic data were obtained from youths and caregivers using procedures developed in partnership with rural African American community members (Brody et al., 2004).

Two years after the long-term follow-up (4.5 years after the pretest), we attempted to contact the study families to obtain youths’ and parents’ DNA from saliva samples. Of the original sample assessed at posttest, 88% (n = 566) of the families were located and one or more members of the family agreed to provide a DNA sample. This resulted in successful genotyping at DRD4 for 448 youths and 436 primary caregivers. Among youths, 171 carried at least one DRD4 7-repeat allele and 169 carried two 4-repeat alleles. Among caregivers, 175 carried at least one DRD4 7-repeat allele and 169 carried two 4-repeat alleles. Participants with other infrequent alleles (e.g. 2,2; 2,3; 2,4) were excluded (n = 108); most of these individuals carried the 4-repeat allele in combination with a rare variant. Three additional participants were excluded because they could not be adequately characterized with regard to 5HTT.

Informed consent forms were completed at all data collection points. Caregivers consented to their own and the youths’ participation in the study, and youths assented to their own participation.

Measures

The measures were selected for their relevance to the evaluation of the preventive intervention program. They were derived from previous research, which included focus group meetings and pilot testing followed by construct validation of the instruments (Brody et al., 2004). Parenting data were collected from caregivers and substance use data from youths.

Demographics

Youth age and gender, maternal age, maternal employment, and monthly income were recorded. Each caregiver reported the number of children and adults living in the home and her marital/significant relationship status. No association between demographic variables and DRD4 genotype emerged (see Table 1). In addition, no significant correlations emerged between demographic variables and past-month substance use or baseline interventiontargeted parenting behavior; accordingly demographic variables were not included as covariates in the analyses.

Table 1.

Equivalence of Demographic Variables for Groups Based on Youth Genotype

| Descriptive Measure |

DRD4, youths |

t-value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any 7-repeat allele (n = 169) |

Two 4-repeat alleles (n = 168) |

||||||

| M | SD | % | M | SD | % | ||

| Per capita income, $/mo. | 524.23 | 388.48 | 497.23 | 354.61 | 0.66 | ||

| Female, youths | 51.5 | 53.0 | -0.27 | ||||

| Single-mother-headed families | 62.7 | 56.5 | 1.15 | ||||

| Baseline intervention-targeted parenting | 66.81 | 8.73 | 66.33 | 10.12 | 0.46 | ||

| Baseline past month substance use | 0.10 | 0.53 | 0.05 | 0.29 | 1.14 | ||

Caregivers’ reports of intervention-targeted parenting behavior

Intervention-targeted parenting was assessed at each wave through caregiver self-report using an instrument developed in previous research with rural African American families (Brody & Ge, 2001; Ge, Brody, Conger, Simons, & Murry, 2002). The scale is composed of 43 items tapping five key intervention-targeted domains: child management, nurturant-involved parenting, racial socialization, sexual communication, and clear expectations about substance use. Sample items include, “I keep from blowing up at my child when I punish him/her. I remind my child that very few children his/her age get involved with alcohol or drugs.” Cronbach’s alpha for the scale was .83.

Past-month substance use

Consistent with other work (Johnston, O’Malley, & Bachman, 2000), youths were asked about frequency of substance use in the past month. The items were, “During the past month, how many times have you: drunk beer, wine, wine coolers, whiskey, gin, or other liquor; had three or more drinks of alcohol at one time; smoked marijuana?” Responses to these three items were summed to form a past-month substance use index, a procedure that is consistent with prior research (Brody & Ge, 2001; Hays, Widaman, DiMatteo, & Stacy, 1987; Needle, Su, & Lavee, 1989; Newcomb & Bentler, 1988; Wills et al., 2007). Cronbach’s alpha for the scale was .65.

Genotyping

Youths’ DNA was obtained using Oragene™ DNA kits (Genetek; Calgary, Alberta, Canada). Youths rinsed their mouths with tap water, then deposited 4 ml of saliva in the Oragene sample vial. The vial was sealed, inverted, and shipped via courier to a central laboratory in Iowa City, where samples were prepared according to the manufacturer’s specifications. Genotype at DRD4 was determined for each youth as described by Lichter et al. (1993). Genotype at the 5-HTTLPR was determined for each sample as described previously (Bradley, Dodelzon, Sandhu, & Philibert, 2005). Genotype was then called by two individuals blind to study hypotheses or other information about the participants.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

At the first data collection session, youths’ mean age was 11.65 years (SD = 0.35) and caregivers’ mean age was 36.7 years (SD = 7.1). Of the mothers, 32.6% were married and living with their husbands, 2.4% were married but separated, 7.1% were cohabiting with a significant other, 25.2% were in a significant relationship but not cohabiting, and 32.7% were not in a significant relationship. Mean household monthly income was $2,082. Although 75% of the mothers were employed outside the home, 44.5% of the families lived below federal poverty standards and another 29.6% lived within 150% of the poverty threshold.

As expected, prevalence rates for drug use at pretest, when the youths were 11 years old, were low: 15% for any alcohol use, 1.2% for binge drinking, and 0.0% for marijuana use. Lifetime prevalence rates increased over time; at the long-term follow-up, when the youths were 14 years old, lifetime rates were 39.2% for alcohol use, 4.6% for binge drinking, and 4.3% for marijuana use. Likewise, average past-month substance use was low at pretest (M = .07, SD = .42) but increased across waves to long-term follow-up (M = .17, SD = .73). These rates for African American youths are consistent with data from other studies (Johnston, O’Malley, Bachman, & Schulenberg, 2007).

Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium was examined for youth genotype distribution; χ2 = .91, p = 0.34. The non-significant chi-square indicates that the distribution of heterozygotes (4-R with non-4-R) was consistent with the distribution of homozygotes (4-R, 4-R), indicating no differential allele dropout.

Plan of Analysis

We used multilevel modeling (Bryk & Raudenbush, 1992) with HLM 6.08 software to examine the data. Two levels of analysis were conducted. First, there were 337 × 4 observations, accounting for the repeated measures within individuals. Second, there were 337 individuals. Because the outcome variable of past-month substance use consisted of count data (number of times using substances) with many zeros (non-consumption) and had a sample variance (.69) greater than the sample mean (.32), we conducted nonlinear analysis using a negative binomial regression for this dependent variable. Models examined the impact of youth genotype at both DRD4 and 5HTT, intervention condition, and the interaction of each genetic polymorphism with treatment. We used a similar approach to examine effects on intervention-targeted parenting but did not use the negative binomial distribution to model the data because the parenting measure was not composed of count data and did not include any zeroes. In the follow-up analyses to rule out passive effects, we focus only on parent DRD4.

Tests of Hypotheses

Effect of youth DRD4 and SAAF on intervention-targeted parenting

First, we determined whether youth DRD4 status interacted with condition to produce differential change in parenting behavior as a function of intervention. Using the analytic framework outlined previously, we found a main effect of participation in SAAF (γSAAF = .89, p < 0.01), but no significant effect for youth genotype for either DRD4 (γ g = 0.08, ns) or 5HTT (γ g = 0.14, ns), and no interaction of intervention with youth genotype at DRD4 (γS×G = -0.38, ns). A significant interaction of youth genotype at 5HTT with SAAF (γS×G = 1.65, p < .05) emerged. The results are summarized in Table 2. As can be seen, SAAF produced expected gains in intervention-targeted parenting behavior for all participants regardless of youth genotype at DRD4.

Table 2.

Effect of SAAF Intervention, Child DRD4 or 5HTT Genotype, and Intervention × Genotype Interaction on Growth in Youth Past Month Substance Use, and Intervention Targeted Parenting (N = 337)

| Past-Month Substance Use |

Intervention-Targeted Parenting |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1a | Model 1b | Model 1c | Model 2a | Model 2b | Model 2c | |

| Intercept | -1.89 | -1.91** | -1.92** | 67.38* | 67.38** | 67.38* |

| Slope | 0.21** | 0.19** | -0.22* | 1.04* | 0.41 | 0.68† |

| SAAF | -0.20* | 0.44** | 0.89** | 0.41 | ||

| DRD4, youth (1 = 7-repeat alleles) | 0.16† | 0.80** | 0.08 | 0.36 | ||

| 5HTTLPR, youth (1 = s allele) | 0.20† | 0.26* | 0.14 | -0.87† | ||

| Two-way interaction | ||||||

| SAAF × DRD4, youth | -1.04** | -0.38 | ||||

| SAAF × 5HTTLPR, youth | -0.18 | 1.65* | ||||

Note. Population-average model with robust standard errors; past-month substance use used negative binomial HLM regression model.

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .01.

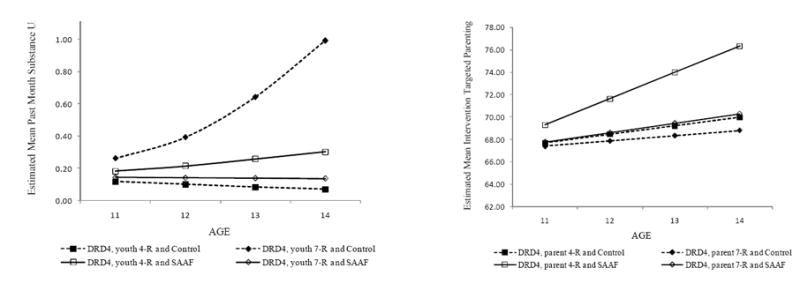

Effect of youth DRD4 and SAAF on past-month substance use

We examined the effect of youth DRD4 status on susceptibility to the intervention. Analysis of the unconditional model showed that the largest share of the variance in past-month substance use was within individuals (21%), reinforcing the importance of within- individual variation. As Table 2 shows, a significant overall treatment effect on past-month substance use emerged (γSAAF = -.20, p < 0.05). Main effects for both the DRD4 7-repeat allele (γ g = .16, p < .10) and the short 5HTT allele (γ g = .20, p < .10) approached significance. A significant gene × intervention interaction emerged for DRD4 (γS×G = -1.04, p < .01) but not for 5HTT (γS×G = - 0.18, NS). To explicate the significant interaction with DRD4, we plotted the means across time for past-month substance use for each of the four subgroups. As Figure 1 shows, SAAF reduced growth in past-month substance use only for youths with one or two copies of the 7-repeat allele for DRD4. The effect size of 0.26 for the interaction of genotype with intervention accounted for 2% of the explained variance in outcomes. Within-group analyses indicated a significant protective effect of SAAF only for those with the 7-repeat allele of DRD4 (γSAAF = -.69, p < 0.01). For those with the 4-repeat allele, the effect was in the opposite direction (γSAAF = .33, p < 0.01).

Figure 1.

Youth genotype at DRD4 moderates SAAF effects on past-month substance use and parent genotype at DRD4 influences SAAF effects on intervention-targeted parenting

Ruling out passive genetic effects

Because, in most cases, a biological relationship existed between the youth and caregiver, it is possible that the observed interaction effect between youth genotype and intervention actually resulted from the effect of parent genotype youth response to treatment. Confirming the potential for such an effect, a chi-square analysis indicated a significant association between caregiver and youth genotypes (χ(1)2 = 45.25, p < .01, N = 258). The number of parent-youth dyads with similar DRD4 status was 91 for those with 4-repeat alleles only and 92 for those with at least one 7-repeat allele; the numbers, however, were significantly lower for those in the off diagonals: 36 for those in which only the parent, and 39 for those in which only the youth, had a 7-repeat allele.

Effect of caregiver DRD4 on youth substance use

To rule out caregiver genotype as a source of passive genetic effects in response to intervention, the analysis of change in youth past-month substance use was repeated using caregiver rather than youth genotype as both a main effect and a moderator of intervention effects. Because there was no effect for youth genotype at 5HTT, parent genotype at 5HTT was not included in the analysis. All parents who provided genetic material and could be assigned to either the 7-repeat allele or the two 4-repeat allele group were included in the analyses (N = 344); the results are presented in Table 3. In this model, the effect of caregiver genotype on youth past-month substance use was not significant as a main effect (γ g = -.03, NS) or in interaction with intervention (γS×G = -.13, NS). Thus, youths’ own genetic variation at DRD4 and not genetic similarity to the caregiver was responsible for the observed intervention × genotype interaction.

Table 3.

Effect of SAAF Intervention, Parent DRD4 Genotype, and Intervention × Genotype Interaction on Growth in Youth Past Month Substance Use, and Intervention Targeted Parenting (N = 344)

| Past-Month Substance Use |

Intervention-Targeted Parenting |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1a | Model 1b | Model 1c | Model 2a | Model 2b | Model 2c | |

| Intercept | -1.93** | -1.94** | -1.94** | 66.89** | 66.89** | 66.89** |

| Slope | 0.17* | 0.31** | 0.28* | 1.09** | 1.19** | 0.79* |

| SAAF | -0.22† | -0.15 | 0.82* | 1.50** | ||

| DRD4, parent (1 = 7-repeat alleles) | -0.03 | 0.04 | -1.10** | -0.35 | ||

| Two-way interaction | ||||||

| SAAF × DRD4, parent | -0.13 | -1.31† | ||||

Note. Population-average model with robust standard errors; past-month substance use used negative binomial HLM regression model.

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .01.

Exploratory examination of caregiver DRD4 on intervention-targeted parenting

Given the association of DRD4 with attentional processes, caregiver genotype could be consequential for degree of change in intervention-targeted parenting. To test this possibility, we conducted an exploratory examination of parents’ own genotypes as a factor in their response to the intervention. The results are summarized in Table 3. Significant main effects emerged for both participation in SAAF (γSAAF = .82, p < .05) and parent genotype (γ g = - 1.10, p < .01). The interaction of SAAF with parent genotype approached significance (γS×G = -1.31, p < .10). As Figure 1 shows, caregivers with the 7-repeat allele reported less change in intervention-targeted parenting behavior than did caregivers with two copies of the 4-repeat allele. The marginal interaction was driven by the significant impact of SAAF on the slope of change among parents with 4-repeat alleles (γSAAF = 1.40, p < .01), with no significant effect for parents with a 7-repeat allele (γSAAF = .19, NS).

Discussion

The results supported the hypotheses that participation in the SAAF prevention program would increase intervention-targeted parenting regardless of youth genotype at DRD4 and that youths with the DRD4 7-repeat allele would be more responsive to the intervention than would youth with two copies of the DRD4 4-repeat allele. A main effect of intervention on change in past-month substance use over time emerged; main effects for both DRD4 and 5HTT approached significance. As the susceptibility hypothesis (Belsky & Pluess, 2009) and research with toddlers (Bakermans-Kranenburg et al., 2008) suggested, youths with the 7-repeat allele were more responsive than those without it to a parenting-focused intervention. Among youths with the 7-repeat allele, those in the control group increased past-month substance use at a substantially greater rate than did those in SAAF. Conversely, for youths with 4-repeat alleles, no evidence indicated that participation in the intervention reduced age-related increases in past-month substance use. The net result was greater differential change in the predicted direction between intervention and control youth for those with the 7-repeat allele relative to those with two 4-repeat alleles. In the context of the susceptibility hypothesis, the results indicated that SAAF interacted with presence of the 7-repeat polymorphism in DRD4 to change a potentially deleterious genetic factor into a potentially positive one. It is important to note, however, that the results are based on youth self-reported substance use and are not corroborated by biological tests. In addition, in other exploratory analyses, we found no evidence of similar moderation by DRD4 for parent-reported delinquency outcomes, suggesting that genetic moderation of the effect of DRD4 is specific to increases in substance use or that parent report may yield a different pattern of results.

We examined caregiver genotype, and its association with youth genotype was highly significant. Caregiver genotype did not, however, account for the observed susceptibility effect among youth. Interestingly, however, parents carrying the 7-repeat allele showed less change over time in intervention-targeted parenting behavior. Together with the observed susceptibility effect for youth with the 7-repeat allele, this suggests the potential need to craft intervention delivery methods that enhance changes in intervention-targeted parenting for caregivers carrying the 7-repeat allele, particularly when they are caregivers for youth with the same allele. In addition, the results suggest that the explication of the caregiver genotype × child genotype × intervention interaction may prove interesting and important when larger samples permit adequately powered examination of higher-order effects.

The differential impact of SAAF was not attributable to different ending points for intervention-targeted parenting as a function of youth genotype at DRD4. Rather, the SAAF program was designed to equalize the parenting environments for youth with differing genotypes. Caregivers showed equivalent changes in response to intervention regardless of youth genotype at DRD4 and showed significantly greater changes in SAAF than in the control condition. Accordingly, the effects support a susceptibility hypotheses and not simply a genetic risk explanation for the impact of the 7-repeat allele of DRD4. This finding has the potential to change understanding of the nature of vulnerability to early substance use and strengthens the argument for provision of preventive programming focused on substance use outcomes.

The effect of genotype on outcomes of interest may have been missed had we not examined the susceptibility hypothesis. Belsky and Pluess (2009) point to the susceptibility hypothesis as a compelling account of the manner in which genetic variability may exert its influence, one that does not require genotypic main effects and fits with broader evolutionary theorizing (Belsky, 1997, 2005). In the case of DRD4, increased susceptibility to variation in parenting behavior and decreased responsiveness of the dopaminergic reward pathway may have been particularly adaptive in contexts of deprivation (Campbell & Eisenberg, 2007), which characterized much of human evolutionary history. At a minimum, some advantages of the DRD4 7-repeat allele seem likely because it appears to have arisen as a rare variant that increased substantially through positive selection over the past 40,000-50,000 years (Ding et al., 2002).

Finally, it is important to note that, in the current study, we found effects of the SAAF intervention on escalation of risk behavior whereas in prior work we have focused primarily on its initiation (e.g. Brody, Murry, Gerrard et al., 2006; Brody, Beach, Philibert, Chen, & Murry, 2009). The emergence of different genetic moderators for initiation (e.g. 5HTT) than for escalation (e.g. DRD4) of risk behavior across adolescence may inform developmental models of youth substance use. In particular, the distinct phases of substance use initiation, substance use escalation, and substance use maintenance into young adulthood may constitute separable processes with differing genetic substrates.

The current results are also of interest from a practical perspective in light of studies of pharmacotherapy for ADHD that have focused on the role of the DRD4 genotype in predicting response to treatment. These studies have found preferential response to treatment among youth with the 4-repeat genotype compared with those carrying the 7-repeat allele (e.g. Cheon, Kim, & Cho, 2007; Hamarman, Fossella, Ulger, Brimacombe, & Dermody, 2004). Combined with the present results and those of Bakermans-Kranenburg et al. (2008), this suggests the intriguing possibility of differential effectiveness of various intervention modalities for some problems in childhood and early adolescence as a function of genotype or associated behavioral characteristics (i.e., pharmacological intervention for some allelic variants or phenotypes and psychosocial interventions for others). Although additional research is necessary, youths with the 7-repeat allele may be particularly responsive to parenting-based intervention whereas those with two 4-repeat alleles are not. This may provide opportunities to enhance universal, community-based interventions by making special efforts to recruit those most likely to show the greatest response. Likewise, the current results suggest that caregivers of some youth with 7-repeat alleles may be less likely to change their parenting styles if they also carry the 7-repeat allele of DRD4. If so, this may constitute an important opportunity to enhance treatment for a subgroup that is particularly likely to show positive effects: parent-child dyads concordant for the 7-repeat allele.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Awards Numbers 5RO1AA012768-08 and 3R01AA012768-08S1 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, and by Awards Numbers 5R01DA01923-04S1 and 1P30DA027827 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, the National Institute on Drug Abuse, or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

The following manuscript is the final accepted manuscript. It has not been subjected to the final copyediting, fact-checking, and proofreading required for formal publication. It is not the definitive, publisher-authenticated version. The American Psychological Association and its Council of Editors disclaim any responsibility or liabilities for errors or omissions of this manuscript version, any version derived from this manuscript by NIH, or other third parties. The published version is available at www.apa.org/pubs/journals/fam

Contributor Information

Steven R. H. Beach, University of Georgia, Institute for Behavioral Research, 514 Boyd Graduate Studies Research Center, Athens, GA 30602-7419

Gene H. Brody, University of Georgia, Center for Family Research, 1095 College Station Road, Athens, GA 30602-4527

Man-Kit Lei, University of Georgia, Center for Family Research, 1095 College Station Road, Athens, GA 30602-4527.

Robert A. Philibert, University of Iowa, 2-126B Medical Education Building, 500 Newton Road, Iowa City, IA 52242-1190

References

- Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, van IJzendoorn MH. Genetic vulnerability or differential susceptibility in child development: the case of attachment. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2007;48:1160–1173. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01801.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, van IJzendoorn MH, Pijlman FTA, Mesman J, Juffer F. Experimental evidence for differential susceptibility: dopamine D4 receptor polymorphism (DRD4 VNTR) moderates intervention effects on toddlers’ externalizing behavior in a randomized controlled trial. Developmental Psychology. 2008;44:293–300. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.44.1.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beach SRH, Kogan SM, Brody GH, Chen Y, Lei M, Murry VM. Change in caregiver depression as a function of the Strong African American Families Program. Journal of Family Psychology. 2008;22:241–252. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.22.2.241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J. Variation in susceptibility to environmental influence: An evolutionary argument. Psychological Inquiry. 1997;8:182–186. [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J. Differential susceptibility to rearing influence: An evolutionary hypothesis and some evidence. In: Ellis B, Bjorklund D, editors. Origins of the social mind: Evolutionary psychology and child development. New York: Guildford; 2005. pp. 139–163. [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, van IJzendoorn MH. For better and for worse: Differential susceptibility to environmental influences. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2007;16:300–304. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8721.2007.00525.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, Pluess M. Beyond diathesis stress: differential susceptibility to environmental influences. Psychological Bulletin. 2009;135:885–908. doi: 10.1037/a0017376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berridge KC, Robinson TE. What is the role of dopamine in reward: Hedonic impact, reward learning, or incentive salience? Brain Research Review. 1998;28:309–369. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(98)00019-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley SL, Dodelzon K, Sandhu HK, Philibert RA. Relationship of serotonin transporter gene polymorphisms and haplotypes to mRNA transcription. American Journal of Medical Genetics: Part B Neuropsychiatric Genetics. 2005;136:58–61. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Beach SRH, Philibert RA, Chen Y-f, Lei M-K, Murry VM, Brown AC. Parenting moderates a genetic vulnerability factor in longitudinal increases in youths’ substance use. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77:1–11. doi: 10.1037/a0012996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Beach SRH, Philibert RA, Chen Y-f, Murry VM. Prevention effects moderate the association of 5-HTTLPR and youth risk behavior initiation: Gene × environment hypotheses tested via a randomized prevention design. Child Development. 2009;80:645–661. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01288.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Ge X. Linking parenting processes and self-regulation to psychological functioning and alcohol use during early adolescence. Journal of Family Psychology. 2001;15:82–94. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.15.1.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Murry VM, Chen Y-f, Kogan SM, Brown AC. Effects of family risk factors on dosage and efficacy of a family-centered preventive intervention for rural African Americans. Prevention Science. 2006;7:281–291. doi: 10.1007/s11121-006-0032-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Murry VM, Gerrard M, Gibbons FX, McNair L, Brown AC, Chen Y-f. The Strong African American Families program: Prevention of youths’ high-risk behavior and a test of a model of change. Journal of Family Psychology. 2006;20:1–11. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.20.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Murry VM, Gerrard M, Gibbons FX, Molgaard V, McNair L, Neubaum-Carlan E. The Strong African American Families Program: Translating research into prevention programming. Child Development. 2004;75:900–917. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00713.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Murry VM, Kogan SM, Gerrard M, Gibbons FX, Molgaard V, Wills TA. The Strong African American Families program: A cluster-randomized prevention trial of long-term effects and a mediational model. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74:356–366. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.74.2.356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Murry VM, McNair L, Chen Y-f, Gibbons FX, Gerrard M, Wills TA. Linking changes in parenting to parent-child relationship quality and youth self-control: The Strong African American Families program. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2005;15:47–69. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2005.00086.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brook JS, Newcomb MD. Childhood aggression and unconventionality: Impact on later academic achievement, drug use, and workforce involvement. Journal of Genetic Psychology. 1995;156:393–410. doi: 10.1080/00221325.1995.9914832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryk AS, Raudenbush SW. Hierarchical linear models for social and behavioural research: Applications and data analysis methods. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell BC, Eisenberg D. Obesity, attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder and the dopaminergic reward system. Collegium Antropologicum. 2007;31:33–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheon KA, Kim BN, Cho SC. Association of 4-repeat allele of the dopamine D4 receptor gene exon III polymorphism and response to methylphenidate treatment in Korean ADHD children. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2007;32:1377–1383. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi WS, Gilpin EA, Farkas AJ, Pierce JP. Determining the probability of future smoking among adolescents. Addiction. 2001;96:313–323. doi: 10.1046/j.1360- 0443.2001.96231315.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conner BT, Hellemann GS, Ritchie TL, Noble EP. Genetic, personality, and environmental predictors of drug use in adolescents. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2010;38:178–190. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2009.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding Y, Chi H, Grady DL, Morishima A, Kidd JR, Flodman P, Moyzis RK. Evidence of positive selection acting at the human dopamine receptor D4 gene locus. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2002;99:309–314. doi: 10.1073/pnas .012464099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge X, Brody GH, Conger RD, Simons RL, Murry VM. Contextual amplification of pubertal transition effects on deviant peer affiliation and externalizing behavior among African American children. Developmental Psychology. 2002;38:42–54. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.38.1.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerrard M, Gibbons FX, Brody GH, Murry VM, Cleveland MJ, Wills TA. A theory-based dual-focus alcohol intervention for preadolescents: The Strong African American Families program. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2006;20:185–195. doi: 10.1037/0893-164x.20.2.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gizer IR, Ficks C, Waldman ID. Candidate gene studies of ADHD: a meta-analytic review. Human Genetics. 2009;126:51–90. doi: 10.1007/s00439-009-0694-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamarman S, Fossella J, Ulger C, Brimacombe M, Dermody J. Dopamine receptor 4 (DRD4) 7-repeat allele predicts methylphenidate dose response in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: A pharmacogenetic study. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology. 2004;14:564–574. doi: 10.1089/cap.2004.14.564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hays RD, Widaman KF, DiMatteo MR, Stacy AW. Structural-equation models of current drug use: Are appropriate models so simple(x)? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1987;52:134–144. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.52.1.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG. Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975-1999. Volume I: Secondary school students (NIH Publication No. 00-4802) Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975-2006 Volume I: Secondary school students (NIH Publication No 07-6205) Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Laucht M, Becker K, Blomeyer D, Schmidt MH. Novelty seeking involved in mediating the association between the dopamine D4 receptor gene exon III polymorphism and heavy drinking in male adolescents: Results from a high-risk community sample. Biological Psychiatry. 2007;61:87–92. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.05 .025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levitan RD, Masellis M, Lam RW, Kaplan AS, Davis C, Tharmalingam S, Kennedy JL. A birth-season/DRD4 gene interaction predicts weight gain and obesity in women with seasonal affective disorder: A seasonal thrifty phenotype hypothesis. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31:2498–2503. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichter JB, Barr CL, Kennedy JL, Van Tol HHM, Kidd KK, Livak KJ. A hypervariable segment in the human dopamine receptor D4 (DRD4) gene. Human Molecular Genetics. 1993;2:767–773. doi: 10.1093/hmg/2.6.767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munafò MR, Clark TG, Flint J. Are there sex differences in the association between the 5HTT gene and neuroticism? A meta-analysis. Personality and Individual Differences. 2004;37:621–626. [Google Scholar]

- Murry VM, Brody GH. Partnering with community stakeholders: Engaging rural African American families in basic research and the Strong African American Families preventive intervention program. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy. 2004;30:271–283. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-0606.2004.tb01240.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murry VM, Brody GH, McNair L, Luo Z, Gibbons FX, Gerrard M, Wills TA. Parental involvement promotes rural African American youths’ self-pride and sexual self-concepts. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2005;67:627–642. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2005.00158.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Needle R, Su S, Lavee Y. A comparison of the empirical utility of three composite measures of adolescent overall drug involvement. Addictive Behaviors. 1989;14:429–441. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(89)90030-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newcomb MD, Bentler PM. Consequences of adolescent drug use: Impact on the lives of young adults. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Ray LA, Bryan A, MacKillop J, McGeary J, Hesterberg K, Hutchison KE. The dopamine D4 Receptor (DRD4) gene exon III polymorphism, problematic alcohol use and novelty seeking: Direct and mediated genetic effects. Addiction Biology. 2008;14:238–244. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2008.00120.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skowronek MH, Laucht M, Hohm E, Becker K, Schmidt MH. Interaction between the dopamine D4 receptor and the serotonin transporter promoter polymorphisms in alcohol and tobacco use among 15-year-olds. Neurogenetics. 2006;7:239–246. doi: 10.1007/s10048-006-0050-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaughn MG, Beaver KM, DeLisi M, Howard MO, Perron BE. Dopamine D4 receptor gene exon III polymorphism associated with binge drinking attitudinal phenotype. Alcohol. 2009;43:179–184. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2009.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA, Murry VM, Brody GH, Gibbons FX, Gerrard M, Walker C, Ainette MG. Ethnic pride and self-control related to protective and risk factors: Test of the theoretical model for the Strong African American Families program. Health Psychology. 2007;26:50–59. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.26.1.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wise RA. The neurobiology of craving: Implications for the understanding and treatment of addiction. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1987;97:118–132. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.97.2.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]