Abstract

Background

For safety considerations, regulatory agencies recommend elimination of antibiotic resistance markers and nonessential sequences from plasmid DNA-based gene medicines. In the present study we analyzed antibiotic-free (AF) vector design criteria impacting bacterial production and mammalian transgene expression.

Methods

Both CMV-HTLV-I R RNA Pol II promoter (protein transgene) and murine U6 RNA Pol III promoter (RNA transgene) vector designs were studied. Plasmid production yield was assessed through inducible fed-batch fermentation. RNA Pol II-directed EGFP and RNA Pol III-directed RNA expression were quantified by fluorometry and quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR), respectively, after transfection of human HEK293 cells.

Results

Sucrose-selectable minimalized protein and therapeutic RNA expression vector designs that combined an RNA-based AF selection with highly productive fermentation manufacturing (>1,000 mg/L plasmid DNA) and high level in vivo expression of encoded products were identified. The AF selectable marker was also successfully applied to convert existing kanamycin-resistant DNA vaccine plasmids gWIZ and pVAX1 into AF vectors, demonstrating a general utility for retrofitting existing vectors. A minimum vector size for high yield plasmid fermentation was identified. A strategy for stable fermentation of plasmid dimers with improved vector potency and fermentation yields up to 1,740 mg/L was developed.

Conclusions

We report the development of potent high yield AF gene medicine expression vectors for protein or RNA (e.g. short hairpin RNA or microRNA) products. These AF expression vectors were optimized to exceed a newly identified size threshold for high copy plasmid replication and direct higher transgene expression levels than alternative vectors.

Keywords: DNA vaccine, Plasmid, Antibiotic-free, RNA interference, Short hairpin RNA, Gene therapy

Introduction

To ensure the safety of DNA products, the European Medicines Agency recommends the elimination of antibiotic resistance markers from plasmid gene therapy vectors [1]. This is to limit the potential transfer of antibiotic resistance to endogenous microbial flora, or activation and transcription of the marker from mammalian promoters after cellular incorporation into the genome. Ideally, these vectors would not encode any protein-based selection marker due to concerns that it may be unintentionally expressed and translated in target mammalian cells. To meet this need, a number of antibiotic-free (AF) plasmid retention systems have been developed in which the vector-encoded selection marker is not protein based. For example, repressor-titration selection requires multiple repressor binding sites in the vector [2]; ColE1 origin-encoded RNAI antisense selection involves no additional vector sequences [3,4]; RNA-OUT antisense selection vectors encode a small heterologous RNA [5]; and nonsense suppression vectors incorporate a tRNA marker [6,7]. Of these, high yield fermentation processes (>500 mg/L) have been developed for both the ColE1 RNAI antisense-based pMINI [900 mg/L; 8] and RNA-OUT antisense-based NTC8385 [1,200 mg/L; 5] vectors.

Vector encoded antigenic peptides, present in nonessential proteins or cryptic open reading frames (ORFs) in bacterial or eukaryotic vector sequences may also be expressed in humans or animals, resulting in cytotoxic T-cell or humoral responses [9]. To reduce this risk, in addition to eliminating protein-based selectable markers, nonessential spacer and junk sequences that do not encode a defined function should be removed. This is difficult to accomplish, since minor variations in the vector backbone can have dramatically adverse effects on production yield, plasmid quality, or mammalian cell expression [9,10,11,12].

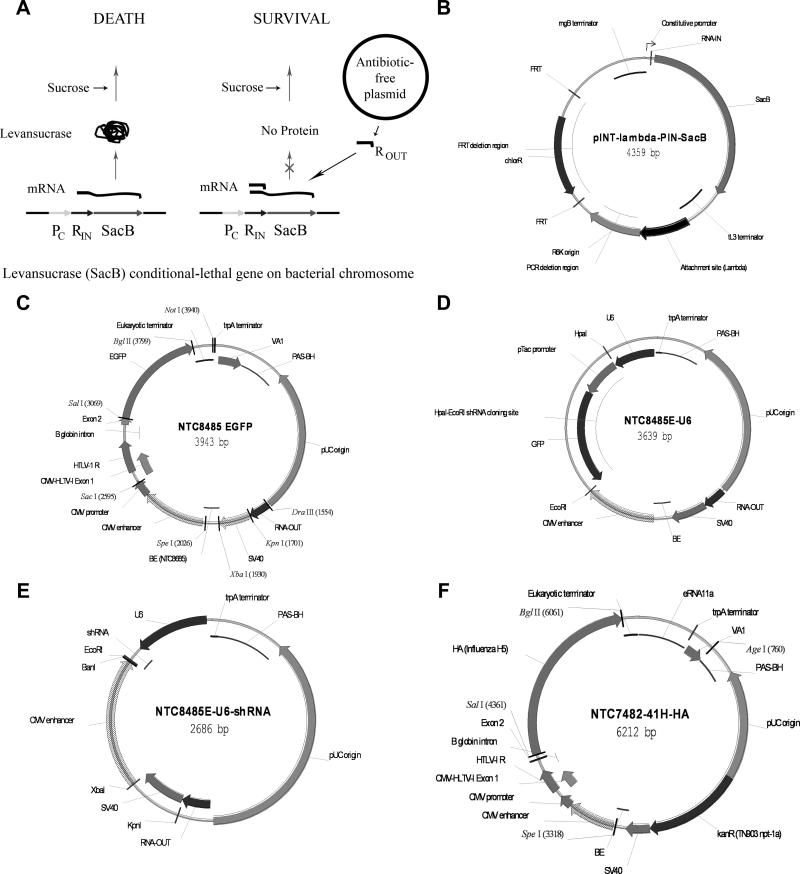

We previously reported the development of minimalized AF mammalian expression vector derivatives of the pDNAVACCUltra plasmid [11]. These vectors incorporate and express a 140 bp RNA-OUT antisense RNA. RNA-OUT represses expression of a chromosomally integrated counter-selectable marker (SacB levansucrase), which is toxic in the presence of sucrose (Figure 1A,B). These sucrose-selectable vectors combined AF selection with highly productive fermentation manufacturing (>1,000 mg/L plasmid DNA yields) and improved transgene expression levels compared to existing vectors [5]. These plasmids were designed to remove nonessential extraneous sequences and are minimalized FDA-compliant [13] vectors for gene therapy or genetic immunization applications.

Figure 1.

Antibiotic-free (AF) selection vectors. (A) RNA-OUT AF selection. Left: In a plasmid-free cell, levansucrase is expressed from a chromosomally-integrated SacB gene, leading to cell death in the presence of sucrose. Right: RNA-OUT (R-OUT) from the plasmid represses translation of the SacB gene, achieving plasmid selection. (B) pINT-λ-PIN-SacB vector. This vector was used to integrate the constitutive promoter (PC) expressed RNA-IN-SacB selection cassette into the phage λ genomic attachment site of the E. coli TG1 strain. (C) NTC8485 EGFP AF vector, with transient expression enhancers HTLV-I R, VA1 and SV40 enhancer. Optimization of the SV40-CMV boundary (BE 120 bp deletion) resulted in the improved expression NTC8685 vector (Table 1). These vectors incorporated an extended replication origin that included a primosomal assembly site (PAS-BH) and the SV40 enhancer. These sequences (PAS-BH-SV40 backbone) improved manufacturing yields [10]. (D) NTC8485E-U6. (E) NTC8485E-U6 shRNA. shRNA oligonucleotides were annealed and cloned downstream of the mU6 promoter by replacing the HpaI-EcoRI pTac-GFP selection module in NTC8485E-U6. Recombinants were non-fluorescent (parentals were green due to GFP expression) in lacI repressor expressing host strains (e.g. lacI expressing strains DH5α, DH10B, TOP10; lacIq expressing strains XL1Blue, TG1, JM109, SURE, Stbl4) when plated on standard LB media supplemented with IPTG. Recombinants were positively selected in cells lines that do not encode the lacI repressor (e.g. JM108, Stbl2) due to pTac promoter mediated toxic overexpression of parental plasmid-encoded GFP. In these strains essentially 100% of the recovered colonies were recombinant. (F) Annotated map of the kanR NTC7482-41H-HA expression vector.

We report herein the development of AF mammalian expression vectors NTC8485 and NTC8685 (Figure 1C). These vectors are CMV-HTLV-I R promoter derivatives of the NTC8385 minimal AF expression vector [5], and additionally incorporate the high copy number PAS-BH-SV40 backbone [10], and transient expression enhancers SV40 and Adenovirus serotype 5 VA RNAI, that increase mammalian cell expression (JAW, manuscript in preparation). A minimalized NTC8485-based AF vector system for therapeutic RNA expression was also developed. These RNA expression vectors have positive selection for recombinant RNA transgene inserts due to inclusion, in the parental vectors, of a protein that is toxic to the transformation host cell line. Target RNAs are expressed using the murine U6 (mU6) RNA Pol III promoter; this is the most potent promoter for vector-based short hairpin RNA (shRNA)-mediated RNA interference (RNAi) [14]. Vector functionality was verified by RNA expression quantification in human cells and high yield fermentation processes developed. Due to the small vector size, to further increase potency, these minimal RNA and protein expression vectors can optionally be dimerized and stably produced in high quantity and quality in fermentation culture.

Materials and Methods

AF selection cell line and plasmids

Kanamycin-resistant (kanR) plasmids were grown in Escherichia coli (E. coli) strain DH5α [F-Φ80dlacZΔM15 Δ(lacZYA -argF) U169 recA1 endA1 hsdR17(rK-, mK+) phoA supE44 λ-thi-1 gyrA96 relA1] (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) or XL1-Blue recA1 endA1 gyrA96 thi-1 hsdR17 supE44 relA1 lac [F′ proAB lacIqZΔM15 Tn10 (Tetr)] (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) while AF plasmids were grown in NTC4862 (DH5α attλ::P5/6 6/6-RNA-IN-SacB, CmR) or XL1-Blue SacB (XL1-Blue attλ::P5/6 6/6-RNA-IN-SacB, CmR). For cell culture testing, low endotoxin (<100 EU/mg) plasmid DNA was purified using Nucleobond AX 2000 columns (Macherey Nagel, Düren, Germany).

The E. coli DH5α-derived NTC4862 and XL1-Blue SacB AF selection cell lines were made using the pCAH63-CAT RNA-IN-SacB (P5/6 6/6) integration plasmid [5]. The plasmid was: PCR amplified with primers that delete the R6K replication origin (Figure 1B); restriction digested and circularized by ligation; and genomically integrated into the phage lambda genomic attachment site using the pINT-ts helper plasmid. This is a temperature sensitive R plasmid that encodes a heat inducible phage lambda integrase. Integrants were verified using PCR as described [15]. These cell lines constitutively express the sacB counter-selectable marker (Bacillus subtilis levansucrase) under the control of the RNA-IN leader sequence. Expression of sacB is conditionally toxic to E. coli in the presence of sucrose. Plasmids containing the 140 bp RNA-OUT RNA (complementary to RNA-IN) prevent sacB translation by RNA interference [5]. Plasmid transformants were selected in the presence of 6% sucrose (Figure 1A). The NTC48193 cell line (Stbl4 attλ::P5/6 6/6-RNA-IN-SacB CmR) for propagation of AF shRNA parent vectors containing the HpaI-EcoRI GFP positive selection module (Figure 1D) was made by integrating the pCAH63-CAT RNA-IN-SacB (P5/6 6/6) plasmid into the lacIq expressing Stbl4 cell line [mcrA Δ(mcrBC-hsdRMS-mrr) recA1 endA1 gyrA96 gal- thi-1 supE44 λ- relA1 Δ(lacproAB)/F′ proAB+ lacIqZΔM15 Tn10 (TetR)] (Invitrogen).

The AF selection TG1 cell line (TG1-FRT-SacB) was made using the pINT-λ-PIN-SacB integration plasmid (Figure 1B). This is a modification of pCAH63-CAT RNA-IN-SacB (P5/6 6/6) wherein the chloramphenicol resistance (CmR) gene was replaced with the pKD3 [16] version which is flanked by FRT sites. This allows optional excision of the CmR marker from the genome using the pCP20 FLP recombinase expression plasmid [16]. This plasmid was integrated into TG1 (Zymo Research, Orange, CA) using the pINT-ts helper plasmid and verified using PCR. The CmR marker was then excised using pCP20 to create markerless cell line TG1-FRT-SacB.

Fermentation

Seed stocks for plasmid fermentation were created in E. coli strain DH5α and derivative NTC4862 for AF selection (or XL1-Blue and XL1-Blue SacB AF selection host) using a low metabolic burden process as described [10]. These strains include the recA mutation (minimizes recombination of cloned DNA), the endA1 mutation (eliminates non-specific plasmid digestion), and relA (allows slow growth without induction of the stringent response). Where indicated, plasmids were dimerized by transformation into the recA+ TG1 or TG1-FRT-SacB cell lines, and resultant colonies screened for the presence of dimerized plasmid. The plasmid dimers were purified and transformed backed into DH5α.

The NTC3019 semidefined fed-batch plasmid fermentation media [17] was modified to contain 0.5% sucrose for AF plasmid selection. Fermentation (6 L working volume) in New Brunswick BioFlo 110 bioreactors was as described [10] using plasmid induction conditions as specified in Tables 1-3. Culture samples were taken at key points and analyzed immediately for biomass (OD600) and for plasmid yield by A280 quantification of plasmid purified using a Spin Miniprep Kit (Qiagen, Hilden Germany).

Table 1.

Antibiotic-free vector expression and manufacturea

| Construct | Size (kb) | ID | Selection | Ferm Yield (mg/L) | Specific yield (mg/L/OD600) | Relative Copy #e | EGFP Expression (HEK293)f |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| gWIZ-EGFPd | 5.75 | RF193 | Kan | 1370 | 16.25 | 2.83 | 38,190 ± 9,329 |

| NTC7485-41H-HAd | 6.21 | RF205 | Kan | 2200 | 24.9 | 4.01 | ND |

| NTC8385-KGFc | 3.59 | RF247 | Sucrose | 775 | 9.11 | 2.54 | 47,808 ± 12,916b |

| NTC8485-KGFc | 3.80 | RF248 | Sucrose | 1210 | 16.2 | 4.26 | 52,141 ± 7,356b |

| NTC8685-KGFc | 3.68 | RF252 | Sucrose | 1055 | 12.7 | 3.45 | 60,418 ± 2,624b |

Fed-batch inducible plasmid fermentation in DH5α or derivative AF section strain NTC4862.

Expression from equivalent EGFP-encoding vector.

All three vectors contained VA1. Plasmid induced by 30-42°C temperature shift at 55 OD600 for 11 h induction, 1 h hold at 25°C.

Plasmid induced by 30-42°C temperature shift at 55 OD600 for 10.5 h induction, 1 h hold at 25°C.

Ratio of specific plasmid yield/size, [mg/L/OD600]]/[kb].

Relative fluorescence units. Average ± SD from two days post triplicate transfection of the indicated plasmids.

Table 3.

Plasmid yields versus size for shake flask and inducible fed-batch fermentationa

| Backbone/Selectionb | Size (kb) | ID | Shake Spec Yield (mg/L/OD600) | Relative copy #d | Ferm Yield (mg/L) | Ferm Spec Yield (mg/L/OD600) | Relative copy #d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pUC19 (A) | 2.7 | RF215 | ND | ND | 121 | 1.4 | 0.5 |

| gwiz (K) | 2.8 | RF213 | 2.7 | 1.0 | 70 | 1.1 | 0.4 |

| 5.7 | RF193 | 7.2 | 1.3 | 1370 | 16.3 | 2.8 | |

| pVAX1-A2 (AF) | 2.9 | RF202 | 1.6 | 0.6 | 212 | 2.5 | 0.8 |

| 5.3 | RF203 | 3.2 | 0.6 | 555 | 6.9 | 1.3 | |

| NTC7482 (K) | 2.8 | RF207 | 2.3 | 0.8 | 186 | 1.6 | 0.6 |

| 5.7 (Dimer) | RF217 | 4.2 | 0.7 | 810c | 6.7c | 1.2 | |

| 3.5 | RF209 | 1.9 | 0.5 | 845 | 7.6 | 2.2 | |

| 6.9 (Dimer) | RF243 | 2.6 | 0.4 | 1290 | 15.5 | 2.2 | |

| 4.5 | RF208 | 2.8 | 0.6 | 1440 | 13.5 | 3.0 | |

| 9.0 (Dimer) | RF242 | 6.7 | 0.7 | 1195 | 15.7 | 1.7 | |

| 6.2 | RF205 | 10.4 | 1.7 | 2200 | 24.9 | 4.0 | |

| 12.4 (Dimer) | RF238 | 6.7 | 0.5 | 1550 | 19.4 | 1.6 | |

| 9.4 | RF214 | 7.3 | 0.8 | 1160 | 15.2 | 1.6 | |

| NTC7485-U6-shRNA (K) | 2.9 | RF226 | 1.6 | 0.6 | 320 | 3.0 | 1.0 |

| RF279 | 290 | 2.9 | 1.0 | ||||

| RF273-XL | 2.9 | 1.0 | 965 | 8.5 | 2.9 | ||

| NTC7485E-U6-shRNA (K) | 3.5 | RF231 | 1.8 | 0.5 | 1300 | 13.5 | 3.9 |

| RF274-XL | 4.2 | 1.2 | 975 | 14.2 | 4.1 | ||

| NTC8485-U6-shRNA (AF) | 2.1 | RF230 | 1.3 | 0.6 | 193 | 2.1 | 1.0 |

| RF276-XLS | 2.7 | 1.3 | 51 | 0.8 | 0.4 g | ||

| 4.2 (Dimer) | RF240 | 2.3 | 0.5 | 420 | 4.6 | 1.1 | |

| RF277-XLS | 3.5 | 0.8 | 835 | 12.4 | 3.0 | ||

| NTC8485E-U6-shRNA (AF) | 2.7 | RF232 | 1.5 | 0.6 | 394 | 4.4 | 1.6 |

| RF278-XLS | 3.7 | 1.4 | 1005 | 14.6 | 5.4 | ||

| 5.4 (Dimer) | RF241 | 3.2 | 0.6 | 1150 | 15.9 | 2.9 | |

| NTC8685-KGFf (AF) | 3.7 | RF260 | 2.3 | 0.6 | 1220 | 14.0 | 3.8 |

| 7.4 (Dimer) | RF263 | 3.8 | 0.5 | 1740 | 24.0 | 3.2 | |

| NTC8685-Ade | 8.3 | RF262 | 5.1 | 0.6 | 1740 | 20.4 | 2.5 |

Plasmids were grown in DH5α or derivative NTC4862 AF selection strain except where indicated (XL1-Blue = XL; XL1-Blue SacB = XLS). Shake flask cultures were grown in LB at 37°C throughout to saturation. Similar results were obtained with Super Broth Select APS (BD Diagnostics, Sparks MD) media (data not shown). Fermentations were grown at 30°C to 55OD600, and then induced at 42°C for 10.5 h prior to holding 1 h at 25°C.

K = Kanamycin resistance; AF = antibiotic free sucrose selection; A = ampicillin resistance

NTC7482 2.8 kb (dimer) fermentation (RF218) at 37C throughout reached 645 mg/L, 4.1 specific yield, 0.7 specific yield/size.

Ratio of specific plasmid yield/size, [(mg/L/OD600)/kb].

Slow linear temperature ramp from 30-42°C over 16 hours starting at 12-14 OD600.

11 h induction.

100/100 colonies at harvest retained plasmid (100% plasmid retention).

Seed stocks for protein fermentation of the pVEX vectors were manufactured in TG1 (pVEXK) or TG1-FRT-SacB (pVEX-AF) and the resultant cell lines fermented using a proprietary defined media fermentation process.

Analytical

Two stage agarose gel electrophoresis (AGE)

Plasmid DNA (uncut and T5 Exonuclease treated to digest all linear and nicked species) was resolved on a TAE agarose gel and poststained with a 1:10,000 dilution of SYBR Green I (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) in TAE buffer. The gel was destained, and electrophoresed again (stage 2). Resolution on a single gel using both conditions enabled high resolution separation of different plasmid isoforms (e.g. supercoiled versus nicked or linear) since they migrate differently in the presence or absence of SYBR Green I (10).

Plasmid methylation

Plasmid was digested with methylation sensitive restriction endonucleases for dam (DpnI cleaves methylated sites; MboI cleaves unmethylated sites; Sau3A cleaves all sites) and dcm (BstNI cleaves all sites; EcoRII cleaves unmethylated sites). Additional enzymatic QC assays to detect various undesirable plasmid alterations included:

Plasmid base integrity (incomplete plasmid DNA repair)

Endonuclease III and VIII (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA) digestion creates a strand break (nicked plasmid) at Apurinic/apyrimidinic (AP) abasic sites (AP sites are generated by various intracellular free radicals);

RNA primer (incomplete plasmid replication)

RNase H (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA) digestion of plasmid-encoded RNA (e.g. RNAII-derived primer) resulted in a nicked plasmid; and

Supercoiling linking number

Plasmid DNA (T5 Exonuclease treated to digest all linear and nicked species) was resolved on a TBE agarose gel containing 2.5 μg/mL chloroquine and poststained with a 1:10,000 dilution of SYBR Green I (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) in TBE buffer.

RNA Pol II CMV promoter Expression Vectors

All vectors were made using standard cloning as described [10]. Plasmids NTC8385, NTC8485, and NTC8685 (Figure 1C) are pUC origin plasmid vectors that contain a 140 bp DraIII-KpnI RNA-based sucrose-selectable marker (RNA-OUT)[5]. NTC8485 (and kanR vector equivalent NTC7485) and NTC8685 incorporate the high copy number PAS-BH-SV40 backbone [10]. NTC8385, NTC8485, and NTC8685 versions with a 600 bp keratinocyte growth factor (KGF) transgene or a NTC8685 derivative with a 5.2 kb adenoviral hexon-IRES-penton transgene (Ad) were made and utilized for fermentation yield analysis.

Plasmid NTC7482-41H-HA (Figure 1F) is a 6.212 kb kanR pUC origin PAS-BH-SV40 backbone high copy number plasmid with the same prokaryotic region (vector backbone) as NTC7485. Smaller derivatives with deletions in the eukaryotic region were constructed by: 1) removing the HA transgene (SalI-BglII sites; 4.5 kb); 2) removing the CMV enhancer-promoter-transgene (SpeI-BglII sites; 3.5 kb); and 3) removing the CMV enhancer-promoter-transgene, eRNA11a and VA1 RNAs (SpeI-BglII sites in vector derivative lacking eRNA11a and VA1; 2.8 kb). A larger derivative was made by cloning a 3.2 kb Ubiquitin-anthrax protective antigen-EGFP fusion transgene into the BglII site downstream of the HA gene (HA-PA-EGFP transgene; 9.4 kb).

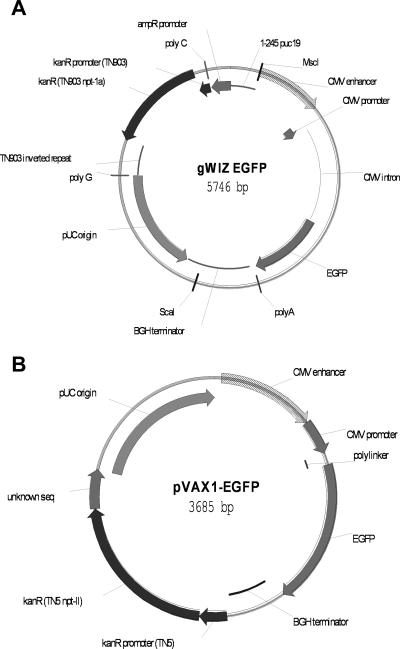

The pVAX1-EGFP vector (Figure 2B) is a 3.685 kb EGFP transgene derivative of the kanR pUC origin pVAX1 minimal DNA vaccine plasmid (Invitrogen). The pVAX1-A1-EGFP (RNA-OUT transcribed clockwise in the same orientation as the parent vector kanR marker) and pVAX1-A2-EGFP (RNA-OUT transcribed counterclockwise) clones were made by cloning the 0.14 kb RNA-OUT AF selection marker (in a 0.15 kb klenow filled DraIII-XbaI restriction fragment from NTC8385) in both orientations into PCR amplified pVAX1-EGFP (using primers designed to delete the kanR gene and promoter as indicated in Figure 2B). AF clones were isolated and verified by sequencing. A larger derivative was made by cloning a 3.2 kb Ubiquitin-anthrax protective antigen-EGFP fusion transgene in place of the EGFP gene in pVAX1-A2-EGFP (HA-PA-EGFP transgene; 5.3 kb).

Figure 2.

Vector retrofit. (A) gWIZ EGFP kanR vector with annotation of functional sequences CMV enhancer, promoter, intron, EGFP transgene, bovine growth hormone (BGH) terminator, and pUC origin. The kanR selection marker and nonessential spacer DNA (TN903 inverted repeat, polyC, polyG, ampR promoter) that accounts for the 2kb increased size compared to NTC8685 are shown. The kanR promoter and kanR gene (black annotation) were replaced with the 140 bp RNA-OUT antibiotic free marker in both orientations. (B) pVAX1 EGFP kanR vector with locations of kanR gene, and other functional sequences (CMV enhancer, promoter, EGFP transgene, BGH terminator, pUC origin) indicated. The kanR promoter and kanR gene (black annotation) were replaced with the 140 bp RNA-OUT antibiotic free marker in both orientations.

The gWIZ-EGFP vector (Figure 2A) is a 5.746 kb EGFP transgene version of the kanR pUC origin gWIZ DNA vaccine plasmid vector (Gene Therapy Systems, San Diego, CA). The 2.833 kb derivative gWIZ-min2 was created by MscI/ScaI digestion/religation of gWIZ-EGFP to remove the eukaryotic region (Figure 2A). The gWIZ-A1-EGFP (RNA-OUT transcribed clockwise) and gWIZ-A2-EGFP (RNA-OUT transcribed counterclockwise in the same orientation as the parent vector kanR marker) clones were made by cloning the RNA-OUT AF selection marker (the 0.15 kb klenow-filled restriction fragment from above) in both orientations into PCR amplified gWIZ-EGFP (using primers designed to delete the kanR gene and promoter as indicated in Figure 2A). AF clones were isolated and verified by sequencing.

E. coli Expression vector

The pVEXK vector (Nature Technology Corporation, Lincoln, NE) is a moderate copy number rop- pBR322 replication origin (without the pUC plasmid G to A high copy mutation [9]) E. coli recombinant protein expression vector. The AF version has the kanR gene and flanking sequences (1.35 kb) replaced with the 0.15 kb RNA-OUT restriction fragment from above in the same orientation.

RNA Pol III mU6 Expression Vectors

The NTC8485E-U6 plasmid (Figure 1D) is a NTC8485 backbone vector with the CMV promoter-eukaryotic terminator replaced by the mU6 promoter-tac-EGFP positive selection cloning cassette from pMLV GFP-neo U6 (a retroviral shRNA expression vector; Nature Technology Corporation, Lincoln, NE). NTC8485E-U6-shRNA (Figure 1E) has a random shRNA with a 22 bp hairpin inserted into the HpaI (blunt end)-EcoRI sites of the NTC8485E-U6 vector. The structure of the recombinant clone hairpin insert is shown below: 5’-gttaaagtcatcgactagccttacttcaagagagtaaggctagtcgatgacttttttttgaattc-3’

The vector-encoded three bases of the 5’ HpaI site and the 3’ EcoRI site are underlined and the 22 bp shRNA inverted repeat is bolded. The NTC8485-U6 and NTC8485-U6-shRNA vectors are derived from the equivalent NTC8485E vectors by deletion of the CMV enhancer (removal of the 570 bp XbaI-BanI fragment, Figure 1E).The kanR NTC7485E-U6-shRNA and NTC7485-U6-shRNA vectors are the kanR equivalents (with the kanR gene substituted, in the same orientation, for RNA-OUT) of the NTC8485 vectors. In NTC8485E-U6 (SV40-) and NTC8485-U6 (SV40-) the SV40 enhancer was removed (XbaI-KpnI region; Figure 1E).

pDNAVACC EGFP-U6 and pDNAVACC EGFP-U6-VA1 are pDNAVACC EGFP expression vectors [11] further containing the mU6 promoter (counterclockwise orientation) or the mU6 promoter combined with adenovirus serotype 5 VA RNAI (VA1) cloned between the eukaryotic transcription terminator and the pUC origin [18]. The mU6 promoter was cloned (in the clockwise orientation) into the polylinker of the ampicillin resistant pGEM3ZF(+) cloning vector (Promega, Madison, WI) to create pGEM3Zf(+) U6.

For quantification of RNA Pol III expression in HEK293 cells, these vectors were modified to express a single stranded non-hairpin RNA (ssRNA; eRNA18) from the mU6 promoter.

eRNA18:5’-gttagcgaaagcaggtactgatcctgtgtggaagatgtgtgcgacaatgcttcaatccgatgattgtcgagcttgcggtgtgt acaatgaaagagtatggggaggacctgtttttt-3’

The first three bases of the 5’ HpaI from the vector is underlined and the predicted 111 bp ssRNA expressed from the mU6 promoter is bolded.

Cell Culture

Adherent human embryonic kidney cell line HEK293 (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA) was propagated in DMEM/F12 containing 10% fetal bovine serum and split (0.25% Trypsin-EDTA) using Invitrogen reagents and conventional methodologies. For transfections, cells were plated on 24-well tissue culture dishes. Supercoiled plasmids were transfected into cell lines using Lipofectamine 2000 following the manufacturer's instructions (Invitrogen). Total cellular lysates for EGFP determination (Tables 1 and 2) were prepared by resuspending cells in cell lysis buffer (BD Biosciences Pharmingen, San Diego, CA) at the indicated time post transfection. Cells were lysed by incubation 30 min at 37°C followed by a freeze thaw cycle at -80°C. Lysed cells were clarified by centrifugation and EGFP assayed in the supernatants using a FLX800 microplate fluorescence reader.

Table 2.

Antibiotic-free vector retrofit

| Construct | Size (kb) | ID | Selection | Ferm Yield (mg/L) | Specific yield (mg/L/OD600) | Relative copy #e | Expression (HEK293)f |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| gWIZ-EGFPd | 5.75 | RF193 | Kan | 1370 | 16.25 | 2.83 | 14,562 ± 7,640 |

| gWIZ –A1-EGFPd | 4.98 | RF196 | Sucrose | 690 | 9.57 | 1.92 | 11,491 ± 4,762 |

| gWIZ –A2-EGFPd | 4.98 | RF198 | Sucrose | 1095 | 14.60 | 2.93 | 14,567 ± 2,101 |

| pVEXKa | 7.29 | RF258 | Kan | 67 | 1.21c | 0.17 | NAb |

| pVEX-AFa | 6.08 | RF259 | Sucrose | 140 | 1.89c | 0.31g | NAb |

| pVEX-AFa | 6.08 | RF257 | Sucrose | 192 | 1.92c | 0.32g | NAb |

| pVAX1-EGFPd | 3.69 | RF194 | Kan | 675 | 8.87 | 2.40 | 2,803 ± 403 |

| pVAX1-A1-EGFPd | 2.91 | RF197 | Sucrose | 260 | 1.91 | 0.66 | 10,620 ± 2608 |

| pVAX1-A2-EGFPd | 2.91 | RF202 | Sucrose | 212 | 2.46 | 0.85 | 11,181 ± 4963 |

Fed-batch defined media protein fermentation was at 37°C throughout in TG1 or derivative AF selection strain TG1-FRT-SacB. The pVEXK tac promoter was induced with 1 mM IPTG at 45-50OD600 (T=0) for 8 h in RF258 and RF259. Plasmid yield at T=8 is reported. RF257 was a no induction control fermentation grown until 100 OD600.

NA = Not applicable.

Plasmid yields at harvest. Harvest OD600 was 56, 74 and 100 for RF258, RF259 and RF257 respectively. Plasmid specific yields for RF258 and RF259 at T=0 (45-50OD600) were 1.47 and 1.26 respectively.

Fed-batch inducible plasmid fermentation in DH5α or derivative AF selection strain NTC4862. Plasmid was induced by 30-42°C temperature shift at 55 OD600 for 10.5 h induction, 1 h hold at 25°C.

Ratio of specific plasmid yield/size, [(mg/L/OD600)/kb].

Relative fluorescence units. Average ± SD from three days post triplicate transfection of the indicated plasmids. Similar results were obtained at one and two days post transfection.

100/100 tested colonies grown from plated T=8 cells retained plasmid (100% plasmid retention).

RT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated from transfected HEK293 cells using the protein and RNA isolation system (PARIS kit, Ambion, Austin TX). Samples were DNase treated (DNA-free DNase; Ambion, Austin TX) prior to reverse transcriptase RT-PCR using the Agpath-ID One step RTPCR kit (Ambion) and a TaqMan eRNA18 transgene 6FAM-CACCGCAAGCTCGA- MGBNFQ probe and flanking primers (5’-GACAATGCTTCAATCCGATGA-3’; 5’-TCCTCCCCATACTCTTTCATTGTAC-3’) in a TaqMan Gene expression assay using the Step One Real Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems Foster City, CA). DNase treatment conditions were confirmed by the lack of detectable signal in control RT-PCR reactions run without the initial 48°C reverse transcriptase step using heat treated 25x PCR buffer (inactivates heat labile reverse transcriptase but not Taq DNA polymerase). Linearized vector was used for the RT-PCR standard curve.

Results

We previously reported development of a low metabolic burden inducible (30-42°C) fed-batch plasmid fermentation process using semi-defined media that increased plasmid yield while enhancing plasmid quality and maintaining plasmid stability [10, 17, 19]. A high copy number kanR plasmid backbone incorporating the SV40 enhancer and an extended replication origin (to include a primosomal binding site, PAS-BH) was identified (Figure 1F; PAS-BH through SV40) [10]. Herein, this high copy PAS-BH-SV40 backbone was used to create potent, minimal AF and kanR protein and RNA expression vectors with improved bacterial copy number and superior mammalian cell expression.

NTC8485 and NTC8685 AF protein expression vectors

KanR selection CMV-HTLV-I R promoter expression vector NTC7485 containing the PAS-BH-SV40 backbone was constructed and subsequently modified for AF selection (Figure 1A) resulting in the AF selection equivalent vector NTC8485 (Figure 1C). NTC8685 is a NTC8485 derivative in which spacer DNA between the SV40 and CMV enhancers was deleted. This deletion resulted in improved CMV promoter-directed transgene expression (Table 1; 60,418 versus 52,141 relative fluorescence units). These vectors have high yield production (>1,000 mg/L; Tables 1 & 3) in the inducible fed-batch plasmid fermentation process and increased EGFP transgene expression and plasmid copy number (Table 1; 3.45-4.26 relative copy number) compared to alternative vectors such as gWIZ (Table 1; 2.83 relative copy number) or pVAX1 (Table 2; 2.40 relative copy number). The AF NTC8685-Ad vector with a large transgene insert had a yield of 1,740 mg/L (Table 3; RF262), similar to that seen with larger kanR vectors. Copy number improvements are critical with minimal vectors, since plasmids yields are reduced with small vectors (i.e. a 6 kb plasmid with the same copy number as a 3 kb plasmid will have twice as much DNA per cell).

gWIZ vector retrofit to AF selection

The gWIZ vector, a commonly utilized kanR DNA vaccine vector, was retrofitted with the RNA-OUT selectable marker (both potential orientations) by precise replacement of the kanR promoter and gene (Figure 2A). Fermentation yield and eukaryotic expression were determined (Table 2; RF193, RF196, and RF198). RNA-OUT orientation A2 (RNA-OUT in same orientation as the kanR gene) had equivalent fermentation copy number (2.93 versus 2.82 relative copy number) and eukaryotic expression (14,567 versus 14,562 relative fluorescence units) as the parent vector. RNA-OUT orientation A1 was detrimental to copy number (Table 2; 1.92 versus 2.83 relative copy number).

pVEXK vector retrofit to AF selection

The pVEXK vector, a moderate copy number (rop- pBR322 origin) kanR E. coli protein expression vector, was retrofitted with the RNA-OUT AF selectable marker by precise replacement of the kanR promoter and gene with RNA-OUT in the same orientation. Defined media fermentation in TG1 (pVEXK) or TG1-FRT-SacB (pVEX-AF) was performed (Table 2; RF194, RF193 and RF202). pVEX-AF had two-fold increased relative copy number in the defined media fermentation harvests compared to the pVEXK parent (0.31 versus 0.17 relative copy number), and 100% plasmid retention at fermentation harvest (Table 2). Collectively, these results demonstrated that the RNA-OUT AF selection system functioned in both defined media protein and semi-defined media plasmid fermentation processes, with different host strains (TG1 versus DH5α) and with moderate copy number rop- pBR322 origin vectors in addition to high copy pUC origin vectors.

pVAX1 vector retrofit to AF selection

The pVAX1 vector, a commonly utilized kanR minimal DNA vaccine vector, was retrofitted with the RNA-OUT AF selectable marker (both potential orientations) by precise replacement of the kanR promoter and gene (Figure 2B) Fermentation yields and eukaryotic expression were determined (Table 2; RF258, RF259, RF257). Both RNA-OUT orientations A1 and A2 had dramatically increased (four-fold) eukaryotic expression compared to the parent vector (Table 2; 10,620 or 11,181 versus 2,803 relative fluorescence units). However, fermentation copy number was reduced three-fold with both A1 and A2 orientations (Table 2; 0.66 or 0.85 versus 2.40 relative copy numbers).

Small vector replication

The effect of plasmid size on fermentation yield was determined. The AF pVAX1-A vectors were very small (2.9 kb) compared to the 3.7 kb parent vector. Increasing the vector size of AF pVAX1-A2 to 5.3 kb increased copy number by 63% (Table 3; RF203 versus RF202). To determine if this effect was limited to AF vectors, a 2.8 kb derivative of kanR gWIZ was constructed and fermented. This vector also had dramatically reduced copy number (seven-fold) compared to the 5.7 kb parent vector (Table 3; RF213 versus RF193) demonstrating reduced copy number in small vectors was not limited to AF selection. The pUC19 ampicillin resistant (ampR) plasmid also replicated at a low copy number (Table 3; RF215); larger vectors with the pUC19 backbone replicated at much higher copy numbers (data not shown).

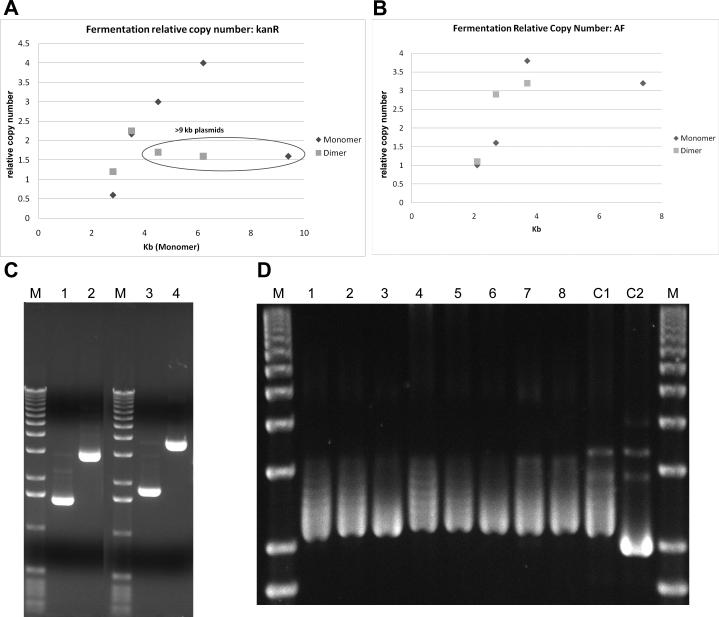

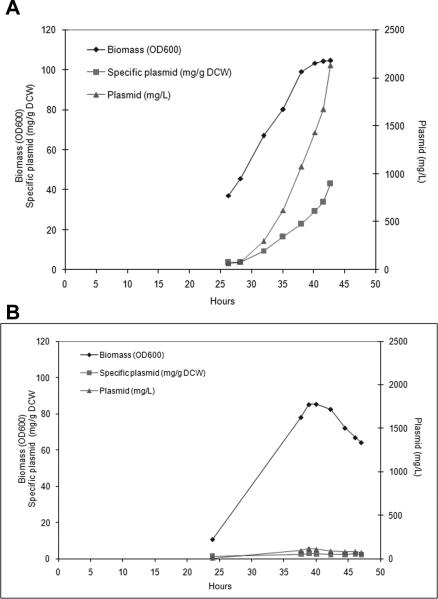

A series of deletions in the eukaryotic portion of the kanR NTC7482-41H-HA vector (Figure 1F; same PAS-BH-SV40 vector backbone as NTC7485) were made and shake flask and fermentation copy number of the resulting 2.8, 3.5, 4.5, 6.2, and 9.4 kb vectors in DH5α was determined (Table 3; Figure 3A). The vectors had similar relative copy number [(mg/L/OD600)/kb] in shake flask culture (0.5-0.8, with the exception of 1.7 for the 6.2 kb plasmid). In fermentation, the vectors from 3.5 kb to 9.4 kb had higher relative copy numbers, compared to shake flask, in a range from 1.6 to 4.0. However, the fermentation relative copy number of the smallest vector (2.8 kb) was reduced four-fold compared to the 3.5 kb vector from 2.2 to 0.6 relative copy number (Table 3; RF207 versus RF209). This is approximately the same as that obtained in shake flask culture with this vector (0.8).

Figure 3.

Vectors <3 kb have reduced copy number. The relative fermentation copy number for monomer and dimer plasmid in DH5α (Table 3) versus monomer vector size for: (A) kanR NTC7485 derivatives; and (B) AF NTC8485 derivatives. Monomer kanR or AF plasmids <3 kb had a much lower relative copy number than larger plasmids. The dimer plasmids of the 2.8 and 3.5kb NTC7485 kanR and the 2.1 and 2.7 kb NTC8485 vectors (plotted at the monomer kb size) had up to two fold improved copy number. Since a dimer plasmid also contains 2 fold more DNA, this resulted in dramatically higher plasmid yields than the corresponding monomer plasmids. (C) The inducible fermentation process maintained AF monomer and dimer plasmid stability with all vector sizes and produced high quality supercoiled plasmid. Plasmid DNA was prestained with SYBR Green I (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) and resolved on a TAE agarose gel. Fermentation harvests (see Table 3 for yields) of 2.1 kb NTC8485-U6-shRNA monomer (RF230; lane 1) and 4.2 kb dimer; (RF240; lane 2) and 2.7 kb NTC8485E-U6-shRNA monomer (RF232; lane 3) and 5.4 kb dimer; (RF241; lane 4) are shown. M is marker lanes (1 kb DNA ladder; Invitrogen). (D) Supercoiling linking number analysis of NTC7485-U6-shRNA fermentation samples. Samples were treated with T5 exonuclease to remove nicked plasmid prior to AGE in the presence of chloroquine. Plasmid from 42°C induction (lanes 1 and 4 = 8 h induction; lanes 2, 5 and 7 = 10 h induction) and post-induction 25°C hold stages (lanes 3, 6 and 8) of DH5α fermentations RF226 (lanes 1-3), RF279 (lanes 4-6), and XL1-Blue fermentation RF273 (lanes 7 and 8) are shown. Lanes C1 and C2 are 8 h 42°C induction sample from DH5α fermentation RF226 (without T5 treatment to remove nicked species) with (C2) or without (C1) E. coli DNA gyrase (New England Biolabs, Beverly, MA) treatment [10] to increase negative supercoiling linking number. In this assay negatively supercoiled plasmid topoisomers with higher linking numbers migrated faster. M is marker lanes (1 kb DNA ladder; Invitrogen).

One difference between shake flask and fermentation production was that shake flasks were grown at 37°C constant temperature while fermentations were induced by 30-42°C temperature shift during growth rate restriction. The 30-42°C induction was critical for improved fermentation plasmid yields (Figure 4A); the copy number of a plasmid in a 37°C throughout fermentation was reduced 2-fold (0.7 relative copy number compared to 1.2 with a 30-42°C fermentation) to the same as that observed in shake flask (Table 3; RF218 versus RF217). While pre-induction copy number was comparable, plasmid copy number induction did not occur after the 30-42°C temperature shift with small plasmids (Figure 4B). Thus small plasmids have reduced fermentation yield due to defective temperature shift-mediated copy number induction.

Figure 4.

Small plasmids have impaired induction. (A) Typical plasmid yield profiles and biomass growth for the inducible fed-batch fermentation (30 to 42°C shift) in DH5α. Induction of this 6.5 kb kanR plasmid was at 29hrs, plasmid yield reached 2130 mg/L after 12 hrs induction. (B) Plasmid yield profiles and biomass for 2.8 kb kanR gWIZ derived plasmid (Table 3; RF213). Induction was at 36 hrs; plasmid yield reached a peak of 120 mg/L and dropped to 70 mg/L after 10.5 h induction.

shRNA expression vectors

A series of murine U6 (mU6) RNA Pol III shRNA expression vectors in the NTC7485 (kanR) and NTC8485 (AF) backbones were made. The shRNA oligonucleotides were cloned downstream of the mU6 promoter replacing a HpaI-EcoRI GFP positive selection module (Figure 1D) to create a compact shRNA expressing vector (Figure 1E).

The effects of inclusion of various sequence elements such as the CMV enhancer, SV40 enhancer, RNA Pol II EGFP transgene, or a second RNA Pol III transcription unit (VA1) on mU6 expression levels in the human cell line HEK293 were determined (Table 4). Expression levels rather than silencing were assessed; expression is a direct determinant of promoter efficiency while silencing can be affected by multiple cell specific factors. The mU6 RNA Pol III promoter was relatively insensitive to vector backbone modifications with similar size-standardized expression levels obtained with a wide range of vectors, although inclusion of a CMV promoter expression cassette (EGFP) slightly reduced expression (Table 4).

Table 4.

U6 expression in various vectorsa

| Name | Pol II enhancer | Size (kb) | pg RNAb (Run 1) | pg RNAb (Run 2) | Avg | Stdc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pGEM3ZF(+) U6 | None | 3.6 | 3.5 | 10.9 | 7.2± 5.2 | 100% c |

| NTC8485-U6 (SV40-)a | None | 2.0 | 15.8 | 13.7 | 14.8± 1.5 | 114% |

| NTC8485-U6a | SV40 | 2.2 | 9.6 | 13.3 | 11.5± 2.6 | 98% |

| NTC8485E-U6 (SV40-)a | CMV | 2.7 | 10.9 | 13.3 | 12.1±1.7 | 126% |

| NTC8485E-U6a | SV40+CMV | 2.8 | 7.1 | 12.5 | 9.8±3.8 | 106% |

| NTC8485E-U6 dimera | SV40+CMV | 5.6 | 5.4 | 16.3 | 10.9±7.7 | 235%d |

| NTC7485-U6 | SV40 | 3.0 | 8.2 | 9.9 | 9.1±1.2 | 105% |

| NTC7485E-U6 | SV40+CMV | 3.6 | 7.9 | 9.4 | 8.7±1.1 | 121% |

| pDNAVACC EGFP-U6 | CMV EPe | 4.3 | 4.2 | 5.8 | 5.0±1.1 | 83% |

| pDNAVACC EGFP-U6-VAI | CMV EPe | 4.5 | 4.1 | 4.3 | 4.2±0.1 | 73% |

| pMLV GFP-neo U6 shRNA | CMV EPe SV40 E | 7.1 | 3.8 | 3.6 | 3.7±0.1 | 101% |

| pDNAVACC EGFP (negative control) | CMV EPe | 3.8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Vectors expressed a 100 bp ssRNA (eRNA18) for RT-PCR quantification. Vector sizes are 100 bp larger than the corresponding shRNA vectors from Table 3. Transfections were performed in duplicate in 24 well plates, using two wells per transfection (4 wells per experiment).

pg eRNA18 target/100 ng total RNA isolated 24 h post transfection.

Standardized mU6 expression compared to pGEM3F(+) U6 vector (avg pg RNA/7.2 × vector size (kb)/3.6 × 100%).

Dimer contained two copies of eRNA18 per plasmid.

Vector contained CMV promoter and RNA Pol II expressed transgene.

The base NTC7485-U6 (2.9 kb) and NTC8485-U6 (2.1 kb) vectors are at or below the minimum size identified above for high copy number fermentation. As expected, fermentation copy number with these constructs was low (Table 3; RF226, RF279 and RF230). While inclusion of the 600 bp CMV enhancer from the parent vectors did not affect expression level in HEK293 (Table 4), the resultant larger NTC7485E-U6 (3.5 kb) and NTC8485E-U6 (2.7 kb) vectors had increased copy number, such that fermentation yields were increased four- and two-fold respectively (Table 3; RF231 and RF232).

XL1-Blue is superior to DH5α for small plasmid production

Shake flask and fermentation plasmid yields in XL1-Blue were determined to evaluate strain-specific effects on plasmid replication. Plasmid production of the 2.1 kb NTC8485-U6 plasmid was similarly low yielding in XL1-Blue and DH5α (Table 3; RF276-XLS and RF230). The RF276-XLS fermentation had 100% plasmid retention at harvest (Table 3) demonstrating that poor plasmid yield was not due to plasmid loss. While XL1-Blue and DH5α had comparable specific yields with large plasmids such as the 3.5 kb NTC7485E-U6-shRNA vector, XL1-Blue fermentation volumetric yields were lower due to reduced biomass compared to DH5α (Table 3; RF274-XL versus RF231). However, XL1-Blue had much higher specific and volumetric yields with the 2.7 kb NTC8485E-U6-shRNA (Table 3; RF278-XL versus RF232) and 2.9 kb NTC7485-U6-shRNA plasmids (Table 3; RF273-XL versus RF226 and RF229).

The quality of XL1-Blue and DH5α produced plasmid was then compared. Plasmid DNA from NTC7485-U6-shRNA in DH5α (RF226, RF279) and XL1-Blue (RF273-XL), and NTC8485E-U6-shRNA in DH5α (RF230) and XL1-Blue SacB (RF278-XLS) was analyzed using QC assays that evaluated plasmid isoforms (2-stage AGE), dam- and dcm-mediated methylation, supercoiling linking number (Figure 3D), plasmid base integrity (AP damaged bases), and incompletely replicated plasmid intermediates (RNA primer) (see Materials and Methods). No significant difference between DH5α and XL1-Blue produced plasmid in these quality attributes was detected (data not shown). Interestingly, plasmid negative supercoiling was slightly higher after the 25°C post plasmid production hold than during 42°C growth (Figure 3D). The 25°C hold step reduced the rate of plasmid replication initiation; we hypothesize that plasmid replication cycles were finished, and gyrase-mediated supercoiling completed during this step.

Small plasmid dimers replicate efficiently

An alternative approach to increase vector potency and fermentation yield is vector multimerization. Vector dimers and trimers of the minimalized AF vectors are small enough for effective cell transfection in vitro or in vivo using electroporation [20]. The effect of dimerization on fermentation yields for the RNA Pol II CMV-HTLV-I R promoter vector NTC8685-KGF (monomer size 3.7 kb) and the RNA Pol III mU6 promoter shRNA vectors NTC8485-U6-shRNA (2.1 kb) and NTC8485E-U6-shRNA (2.7 kb) in DH5α was determined (Table 3; Figure 3B). Dimer relative copy number was approximately the same as monomer with NTC8485-U6-shRNA (Table 3; RF240 versus RF230) and NTC8685-KGF resulting in two-fold improved fermentation yields up to 1,740 mg/L with the NTC8685-KGF dimer plasmid (Table 3; RF263 versus RF260). NTC8485-U6-shRNA dimer relative copy number was seven-fold higher than the monomer in XL1-Blue resulting in yield increase from 51 to 835 mg/L (Table 3; RF277-XLS versus RF276-XLS). Dimer relative copy number in DH5α was increased approximately two-fold compared to monomer with NTC8485E-U6-shRNA, resulting in three-fold improved volumetric yields to 1,150 mg/L (Table 3; RF241 versus RF232). As expected, NTC8485E-U6-shRNA dimer had two-fold increased mU6-directed expression in HEK293 cells compared to the monomer plasmid (235% versus 106% standardized mU6 expression, respectively; Table 4).

The 2.8, 3.5, 4.5, and 6.2 kb kanR PAS-BH-SV40 vectors were also dimerized and shake flask and fermentation yields in DH5α were determined (Table 3). Relative dimer copy number was the same or reduced compared to monomer for the 3.5, 4.5, and 6.2 kb vectors. As seen with small AF plasmid dimers, dimerization of the 2.8 kb kanR vector increased relative plasmid copy number two-fold resulting in a dimer fermentation yield improvement of four-fold over monomer (Table 3; RF217 versus RF207).

The inducible fermentation process produced high quality monomer and dimer DNA (Figure 3C). For example, the NTC8485E-U6-shRNA monomer fermentation harvest was 98.5% monomer with 1.5% dimer and undetectable trimer, while the dimer fermentation harvest was 99.3% dimer with 0.7% trimer and undetectable monomer (data not shown). This was expected since this process was designed to maintain plasmid stability during growth, and has been demonstrated to stabilize production of a variety of rearrangement prone vectors [19].

Discussion

The minimalized CMV-HTLV-I R promoter AF NTC8485 and NTC8685 RNA Pol II protein transgene expression vectors described herein combined high manufacturing yields (PAS-BH-SV40 backbone) with increased mammalian cell expression (Table 1) through optimization of the vector backbone configuration and inclusion of transient expression enhancers VA1 and HLTVI-R (Figure 1C). Inclusion of these elements increased the vector backbone size to 3.0-3.1 kb. A transgene insertion (e.g. the 0.6 kb KGF gene) will increase vector size over the minimal required for high yield fermentation. Thus, these vectors are optimized for potency, manufacturing yield, and transgene expression.

Vector retrofits from kanR to AF selection generated AF versions of the commonly used gWIZ and pVAX1 CMV promoter DNA vaccine vectors. This also identified vector design criteria impacting copy number and mammalian cell expression. In the gWIZ backbone the optimal orientation for transcription of the RNA-OUT selection marker was towards the replication origin; the opposite orientation had reduced copy number (Table 2). Previous analysis of the VR1012 plasmid (same backbone as gWIZ) identified 4 promoters upstream of the kanR gene and no transcriptional terminator between kanR and the replication origin. The addition of a transcriptional terminator downstream of the kanR marker did not increase copy number [21]. This result, in combination with our observation of reduced copy number with divergently transcribed RNA-OUT, demonstrated marker-mediated transcriptional interference of replication primer synthesis is unlikely to reduce copy number in the gWIZ vector and that transcription into the origin may be beneficial to replication. In pVAX1, RNA-OUT orientation-with respect to the replication origin-had little effect on plasmid copy number, although the orientation wherein RNA-OUT transcription was towards the replication origin was slightly increased. By contrast, in pDNAVACC vectors, the optimal orientation of a kanR selection marker was divergent from the replication origin [11]. However, in pMCP-1 (4.9 kb), the npt-II kanR gene, divergently transcribed away from the replication origin, reduced fermentation yield three-fold compared to the 3.5 kb pMINI AF version [8]. It appears that vector-intrinsic differences determine optimal selection marker-replication origin configurations for high copy number replication.

Both AF versions of the pVAX1 vector had dramatically higher eukaryotic transgene expression than the parent kanR vector (Table 2). The orientation of the TN903 derived npt-1a kanR gene in pDNAVACC vectors dramatically affected mammalian cell expression, presumably due to the presence of spurious binding sites for mammalian cell repressor or activator proteins [9,11]; this may also be the case with the TN5 derived npt-II gene in pVAX1 which is positioned adjacent to the BGH terminator (Figure 2B).

Unlike the CMV promoter, the mU6 RNA Pol III promoter was relatively insensitive to vector backbone modifications with similar standardized expression levels from a wide range of vectors (Table 4). RNA Pol III promoters are simpler in structure and may be less affected by spurious transcription factor binding sites present in different vector backbones. The presence of an active RNA Pol II CMV promoter expression cassette (EGFP) reduced expression perhaps due to competition for common promoter cofactors. The presence of the CMV and or SV40 enhancers in isolation did not significantly increase mU6 promoter expression. This contrasts previous reports that the CMV enhancer-U6 or CMV enhancer-H1 (CMV-H1) chimeric promoters improved RNA silencing of target genes compared to the parent mU6 or H1 promoters in cell culture [22, 23]. This may be due to different endpoints (expression versus silencing) and methodologies employed in these studies. Indeed, a comparison of the H1 and CMV-H1 promoters in NIH3T3 and in vivo identified different optimal vectors for inhibition of target gene expression in the two conditions. The CMV-H1 vector was however superior for in vivo delivery [24]. The SV40 enhancer increased plasmid nuclear import and improved plasmid expression in vivo after delivery to non-dividing muscle cells [25]. The minimal 2.7 kb NTC8485E-U6-shRNA vector, which contains both the CMV and SV40 enhancers, may therefore be the most potent vector for in vivo RNA delivery.

Small plasmids replicate at reduced copy number in growth-restricted inducible fed-batch fermentation culture, but not shake flask culture. The dramatic increase in copy number, typically observed after temperature shift of growth-restricted fermentations, was not obtained with smaller plasmids (Table 3; Figure 4B). Monomer and dimer fermentations demonstrated that: 1) Reduced yields were due to impaired plasmid copy number induction, and not plasmid loss; 2) Impaired plasmid induction correlated with monomer subunit size of 2.1 kb (XL1-Blue), or 2.1- 2.9kb (DH5α); and 3) Impaired plasmid induction did not affect plasmid quality; high quality monomer and dimer DNA was produced regardless of the copy number (Figure 3C).

Copy number reduction was not due to cellular toxicity (there was no fermentation lysis) or plasmid instability (i.e. no plasmid deletion products in fermentation harvest samples). The effect was independent of selectable marker (AF, kanR, ampR) or vector backbone (NTC, gWIZ, pUC, or pVAX1 backbone). Generic differences in the effects of supercoiling [26] or other structural attributes of plasmids <3 kb may be the cause, perhaps through inhibition of replication primer formation by reduced RNAII primer or increased RNAI repressor transcription levels [26], reduced RNAII D-loop formation, or reduced RNase H-mediated replicative primer formation. Alternatively, small plasmids may be less efficient at DNA Pol I replication initiation or DNA Pol III replication elongation.

The PAS-BH-SV40 backbone RNA Pol III shRNA expression vector NTC8485-U6-shRNA with a short hairpin RNA transgene is only 2.1 kb and is poor yielding in both DH5α and XL1-Blue. Inclusion of the flanking CMV enhancer (NTC8485E-U6-shRNA) increased the size to 2.7 kb and improved relative copy number and fermentation yields, compared to NTC8485-U6, from 193 to 394 mg/L (DH5α) or from 51 to 1005 mg/L (XL1-Blue) (Table 3). The corresponding kanR NTC7485E-U6-shRNA vector is 3.5 kb, and had four-fold increased copy number (to 1,300 mg/L) compared to the 2.9 kb NTC7485-U6-shRNA vector (320 mg/L; Table 3) in DH5α. These plasmids were both similarly high yielding (965 and 975 mg/L) in XL1-Blue. These differences are likely due to strain-specific epigenetic factors. For example DNA gyrase overexpression (increased negative supercoiling) was highly detrimental to plasmid copy number induction in DH5α [10]. Slight differences in supercoiling between XL1Blue and DH5α during 42°C growth (Figure 3D) may account for the improved copy number of 2.7-2.9 kb plasmids in XL1Blue. Given that DH5α and XL1Blue produce similarly high quality plasmid, XL1Blue is the superior host for production of small (<3 kb) vectors such as NTC8485E-U6-shRNA, and NTC7485-U6-shRNA.

ColE1 plasmid replication is controlled by the plasmid-encoded RNAI repressor, such that plasmid levels are set by the number of origins per cell; dimers therefore replicate at approximately ½ the copy number of monomers [27]. Consistent with this, larger dimers >7 kb had reduced copy number compared to the monomer (Table 3). As well, copy number was reduced with dimerized and trimerized versions of a 4.6 kb plasmid in batch fermentation [28]. By contrast plasmid copy number was either unaffected or increased up to two-fold for vectors in which the dimer was 7 kb or less. This resulted in dimer fermentation yield improvement of two to four-fold over monomer fermentations (Table 3). The increased copy number of the small plasmid dimers, as opposed to a 50% reduction, is further indication that generic structural replication problems exist with small plasmids. Vector dimerization is thus a method to improve small plasmid production in fermentation culture.

As expected, the NTC8485E-U6-shRNA dimer had twice the standardized expression level compared to the other vectors, due to the presence of two mU6 expression cassettes per molecule (235% versus 106%; Table 4). This is consistent with previous studies demonstrating plasmid concatamers had dramatically improved transgene expression in mammalian cells and that small plasmid multimers were ideal to maximize both cell transfection efficiency and transgene expression [29,30].

In summary, we report the development of minimalized AF NTC8485 (RNA Pol II and Pol III promoters) and NTC8685 (RNA Pol II promoter) series plasmids for expression of protein or RNA products. These vectors can be optionally dimerized or trimerized into increased potency multimers that are: 1) stably manufactured in high quantity and quality in the inducible fermentation process; and 2) small enough (e.g. NTC8485-U6-shRNA trimer is 6.3 kb) for effective in vivo delivery using electroporation [20]. These AF vectors are potent non-viral alternatives for gene and shRNA therapies.

Acknowledgements

We thank Kim Hanson (Nature Technology) for purifying the plasmid DNA used in this study, Aaron Tabor (Gene Facelift) for providing the KGF gene and Ann Leen (Baylor College of Medicine) for providing the adenoviral hexon-IRES-penton transgene. This paper described work supported by NIH grants R44 GM072141-03 and R43 GM080768-01 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: AEC, JL, JMV, SA, AS, CPH and JAW have an equity interest in Nature Technology Corporation.

References

- 1.EMA . Non-clinical studies required before first clinical use of gene therapy medicinal products. European Medicines Agency; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Williams SG, Cranenburgh RM, Weiss AM, Wrighton CJ, Sherratt DJ, Hanak JA. Repressor titration: a novel system for selection and stable maintenance of recombinant plasmids. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:2120–2124. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.9.2120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cranenburgh RM. Plasmid maintenance. 2009 US patent 7611883.

- 4.Pfaffenzeller I, Mairhofer J, Striedner G, Bayer K, Grabherr R. Using ColE1-derived RNAI for suppression of a bacterially encoded gene: implication for a novel plasmid addiction system. Biotechnol J. 2006;1:675–681. doi: 10.1002/biot.200600017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Luke J, Carnes AE, Hodgson CP, Williams JA. Improved antibiotic-free DNA vaccine vectors utilizing a novel RNA based plasmid selection system. Vaccine. 2009;27:6454–6459. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Soubrier F, Cameron B, Manse B, et al. pCOR: a new design of plasmid vectors for nonviral gene therapy. Gene Ther. 1999;6:1482–1488. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3300968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marie C, Vandermeulen G, Quiviger M, Richard M, Préat V, Scherman D. pFARs, Plasmids free of antibiotic resistance markers display high-level transgene expression in muscle, skin and tumor cells. J Gene Med. 2010;12:323–332. doi: 10.1002/jgm.1441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mairhofer J, Cserjan-Puschmann M, Striedner G, Nöbauer K, Razzazi-Fazeli E, Grabherr R. Marker-free plasmids for gene therapeutic applications-lack of antibiotic resistance gene substantially improves the manufacturing process. J Biotechnol. 2010;146:130–137. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2010.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Williams JA, Carnes AE, Hodgson CP. Plasmid DNA vector design; impact on efficacy, safety and upstream production. Biotechnol Adv. 2009;27:353–370. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2009.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Williams JA, Luke J, Langtry S, Anderson S, Hodgson CP, Carnes AE. Generic plasmid DNA production platform incorporating low metabolic burden seed-stock and fed-batch fermentation processes. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2009;103:1129–1143. doi: 10.1002/bit.22347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Williams JA, Luke J, Johnson L, Hodgson CP. pDNAVACCultra vector family: high throughput intracellular targeting DNA vaccine plasmids. Vaccine. 2006;24:4671–4676. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2005.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Azzoni AR, Ribeiro SC, Monteiro GA, Prazeres DM. The impact of polyadenylation signals on plasmid nuclease-resistance and transgene expression. J Gene Med. 2007;9:392–402. doi: 10.1002/jgm.1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.FDA . Guidance for industry: considerations for plasmid DNA vaccines for infectious disease indications. US Food and Drug Administration; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Takahashi Y, Yamaoka K, Nishikawa M, Takakura Y. Quantitative and temporal analysis of gene silencing in tumor cells induced by small interfering RNA or short hairpin RNA expressed from plasmid vectors. J Pharm Sci. 2009;98:74–80. doi: 10.1002/jps.21398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haldimann A, Wanner BL. Conditional-Replication, Integration, Excision, and Retrieval Plasmid-Host Systems for Gene Structure-Function Studies of Bacteria. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:6384–6393. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.21.6384-6393.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Datsenko KA, Wanner BL. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:6640–6645. doi: 10.1073/pnas.120163297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carnes AE, Hodgson CP, Williams JA. Inducible Escherichia coli fermentation for increased plasmid DNA production. Biotechnol Appl Biochem. 2006;45:155–66. doi: 10.1042/BA20050223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Williams JA. Vectors and Methods for Genetic Immunization. 2008 World Patent Application WO2008153733.

- 19.Carnes AE, Williams JA. Low metabolic burden plasmid production. Genetic Eng Biotech. News. 2009;29:56–57. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Molnar MJ, Gilbert R, Lu Y, et al. Factors influencing the efficacy, longevity, and safety of electroporation-assisted plasmid-based gene transfer into mouse muscles. Mol Ther. 2004;10:447–455. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2004.06.642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Audonnet J. DNA Plasmids having improved expression and stability. 2008 World Patent Application WO2008136790.

- 22.Xia XG, Zhou H, Ding H, Affar EB, Shi Y, Xu Z. An enhanced U6 promoter for synthesis of short hairpin RNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:e100. doi: 10.1093/nar/gng098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ong ST, Li F, Du J, Tan YW, Wang S. Hybrid cytomegalovirus enhancer-H1 promoter-based plasmid and baculovirus vectors mediate effective RNA interference. Human Gene Ther. 2006;16:1404–1412. doi: 10.1089/hum.2005.16.1404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hassani Z, Francois JC, Alfama G, et al. A hybrid CMV-H1 construct improves efficiency of PEI-delivered shRNA in the mouse brain. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:e65. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li S, MacLaughlin FC, Fewell JG, Gondo M, Wang J, Nicol F, Dean DA, Smith LC. Muscle-specific enhancement of gene expression by incorporation of SV40 enhancer in the expression plasmid. Gene Ther. 2001;8:494–497. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wood DC, Lebowitz J. Effect of supercoiling on the abortive initiation kinetics of the RNA-I promoter of ColE1 plasmid DNA. J Biol Chem. 1984;259:11184–11187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Summers D. Timing, self-control and a sense of direction are the secrets of multicopy plasmid stability. Mol Microbiol. 1998;29:1137–1145. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.01012.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Voβ C, Schmidt T, Schleef M, Friehs K, Flaschel E. Production of supercoiled multimeric plasmid DNA for biopharmaceutical application. J Biotechnol. 2003;105:205–213. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2003.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Leahy P, Carmichael GG, Rossomando EF. Transription from plasmid expression vectors is increased up to 14-fold when plasmids are transfected as concatamers. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:449–450. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.2.449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maucksch C, Bohla A, Hoffmann F, et al. Transgene expression of transfected supercoiled plasmid DNA concatemers in mammalian cells. J Gene Med. 2009;11:444–453. doi: 10.1002/jgm.1310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]