Abstract

Purpose

To assess outcomes 1 year after Descemet’s stripping automated endothelial keratoplasty (DSAEK) in comparison with penetrating keratoplasty (PKP) from the Specular Microscopy Ancillary Study (SMAS) of the Cornea Donor Study.

Design

Multicenter, prospective, nonrandomized clinical trial.

Participants

A total of 173 subjects undergoing DSAEK for a moderate risk condition (principally Fuchs’ dystrophy or pseudophakic/aphakic corneal edema) compared with 410 subjects undergoing PKP from the SMAS who had clear grafts with at least 1 postoperative specular image within a 15-month follow-up period.

Methods

The DSAEK procedures were performed by 2 experienced surgeons per their individual techniques, using the same donor and similar recipient criteria as for the PKP procedures in the SMAS performed by 68 surgeons at 45 sites, with donors provided from 31 eye banks. Graft success and complications for the DSAEK group were assessed and compared with the SMAS group. Endothelial cell density (ECD) was determined from baseline donor, 6-month (range, 5–7 months), and 12-month (range, 9–15 months) postoperative central endothelial images by the same reading center used in the SMAS.

Main Outcome Measures

Endothelial cell density and graft survival at 1 year.

Results

Although the DSAEK recipient group criteria were similar to the PKP group, Fuchs’ dystrophy was more prevalent in the DSAEK group (85% vs. 64%) and pseudophakic corneal edema was less prevalent (13% vs. 32%, P<0.001). The regraft rate within 15 months was 2.3% (DSAEK group) and 1.3% (PKP group) (P = 0.50). Percent endothelial cell loss was 34±22% versus 11±20% (6 months) and 38±22% versus 20±23% (12 months) in the DSAEK and PKP groups, respectively (both P<0.001). Preoperative diagnosis affected endothelial cell loss over time; in the PKP group, the subjects with pseudophakic/aphakic corneal edema experienced significantly higher 12-month cell loss than the subjects with Fuchs’ dystrophy (28% vs. 16%, P = 0.01), whereas in the DSAEK group, the 12-month cell loss was comparable for the 2 diagnoses (41% vs. 37%, P = 0.59).

Conclusions

One year post-transplantation, overall graft success was comparable for DSAEK and PKP procedures and endothelial cell loss was higher with DSAEK.

Until recently, penetrating keratoplasty (PKP) was the standard procedure for the surgical treatment of vision loss associated with Fuchs’ dystrophy or pseudophakic/aphakic corneal edema. Major problems that have remained with this procedure since its development have been unpredictable astigmatic changes, risk of traumatic wound dehiscence, and long-term endothelial cell loss. Results from the Cornea Donor Study (CDS) and its ancillary study, the Specular Microscopy Ancillary Study (SMAS), have shown that after PKP for conditions at moderate risk for graft failure due to endothelial decompensation (principally Fuchs’ dystrophy or pseudophakic/aphakic corneal edema), the endothelial cell density (ECD) decreased by 70% (from a median of 2800 cells/mm2 to a median of 800 cells/mm2) within 5 years of transplantation.1

Endothelial keratoplasty recently has become an accepted and commonly used method for surgical management of endothelial decompensation caused by these same conditions.2 Between 2005 and 2008, the number of donor corneas the Eye Bank Association of America supplied for endothelial keratoplasty increased from 1429 to 17,468, and endothelial keratoplasty increased from 3% to 33% of the total transplants performed with Eye Bank Association of America-supplied corneas (2008 Eye Banking Statistical Report, available from the Eye Bank Association of America at http://www.restoresight.org/donation/statistics.htm, accessed April 30, 2009). Endothelial keratoplasty has gained popularity because it provides more rapid visual recovery, minimizes induced astigmatism, and, most important, maintains globe integrity better than PKP.2–4 As endothelial keratoplasty techniques have evolved, Descemet’s stripping automated endothelial keratoplasty (DSAEK) has become the most widely used method.

A number of studies suggest that 6-month cell loss is significantly higher after endothelial keratoplasty than PKP.5–8 Only 2 published DSAEK studies have reported cell loss to 2 years. In both, the cell loss increased by only 6% to 7%, relative to the baseline donor ECD, between 6 months and 2 years.5,8 These were relatively modest increases compared with the 25% increase in cell loss seen in a comparable time period in the SMAS PKP eyes.1 Limited data have been reported on relative graft survivals for endothelial keratoplasty versus PKP.

The ideal approach to determine any statistically and, more important, clinically significant differences in endothelial cell loss and graft success after DSAEK and PKP would be with a prospective, randomized study using the same donor pair and a central reading center to determine ECD on the donor and postoperative endothelial images. However, with the clear lowering of the risk of catastrophic eye loss with DSAEK with the smaller incision both intra-operatively if the patient develops a suprachoroidal hemorrhage and postoperatively if the eye has a traumatic injury, as well as reported lower induced astigmatism and more rapid visual recovery,2 it would be difficult to receive institutional review board approval and recruit surgeons and subjects for this type of randomized trial. In lieu of this design, this report describes the results of a prospective study examining outcomes of DSAEK, in particular endothelial cell loss and graft success, using the same donor and recipient inclusion/exclusion criteria and follow-up examination procedures and the same reading center that was used in the SMAS to determine ECD.1,9–11 The results were compared with the outcomes of the well-characterized historical subset from the SMAS that had a clear graft after PKP with at least 1 postoperative ECD within the first 15 months determined by the same reading center.

Materials and Methods

Inclusion Criteria and Data Collection

In this prospective, interventional study, subjects were treated with DSAEK at Price Vision Group (Indianapolis, IN) and Gorovoy Eye Specialists (Tampa, FL) between June 2006 and September 2007. The University Hospitals Case Medical Center (Cleveland, OH) institutional review board approved the study, and each subject gave written informed consent to participate. The results of 6 subjects (6 eyes) in the current study were included in a previous retrospective analysis of 6-month endothelial cell loss that relied on site-determined postoperative endothelial cell densities.5

Subject eligibility criteria were exactly the same as those used in the SMAS, except the age range was 40 to 85 years old in the DSAEK group, whereas the SMAS cohort age range was 40 to 80 years old. Eligible subjects in the SMAS, as in the prospective series of patients with DSAEK, had conditions at moderate risk for graft failure after PKP caused by endothelial decompensation (principally Fuchs’ dystrophy or pseudophakic/aphakic corneal edema). Patients undergoing a regraft or who had 2 or more quadrants of stromal neovascularization, uncontrolled uveitis, uncontrolled glaucoma, prior placement of a glaucoma shunt, or fellow eye visual acuity <20/200 were excluded. Only 1 eye per patient was enrolled in both groups.

Donor eligibility criteria were the same as those used in the SMAS.1,10,12 Donor criteria included an age range of 10 to 75 years old, an eye bank-determined ECD of 2300 to 3300 cells/mm2, death to surgery time of ≤5 days, and death to preservation time of ≤12 hours, if the body was refrigerated or eyes were iced, and ≤8 hours if not.

Data collection forms that paralleled those used in the CDS and the SMAS were provided to participating eye banks and clinical sites for completion and transmission to Case Western Reserve University Vision Research Coordinating Center, where the clinical data were collected and analyzed.1,11,12 The Coordinating Center also audited both clinical sites during and at conclusion of the follow-up period to verify all data.

Descemet’s Stripping Automated Endothelial Keratoplasty Surgical Technique

Two surgeons (FWP and MG) performed the DSAEK procedures, as previously described.3,13 Unlike the CDS and the SMAS, the surgeons were not masked as to donor characteristics, but were obligated to use donor tissue according to the CDS/SMAS guidelines. If a significant cataract was present, a phacoemulsification procedure was performed before the DSAEK procedure. Removal of the cataract created more space in the anterior chamber to safely position the graft. In addition, both surgeons preferred to replace anterior chamber intraocular lenses with suture-fixated posterior chamber intraocular lenses before the DSAEK.

In brief, the donor cornea was dissected using a Moria CB microkeratome and associated artificial anterior chamber (Moria USA, Doylestown, PA). After dissection, the donor tissue was transferred to a punching system and cut with a trephine size between 8.25 and 9.0 mm.

Surgery was performed on the recipient using topical anesthesia and monitored intravenous sedation. A 3.2-mm corneal incision (MG) or a 5-mm temporal scleral tunnel or clear corneal incision (FWP) was made, and Descemet’s membrane and endothelium were stripped from within the planned graft area. The donor cornea was folded over onto itself in a “taco” configuration and inserted into the anterior chamber using single-point fixation forceps, or the graft was pulled into the eye through a funnel glide. Air was injected into the anterior chamber to help unfold the donor tissue and press it up against the recipient cornea. Three or four equally spaced small incisions were made in the mid-peripheral recipient cornea down to the graft interface to help drain any residual fluid from the interface.

At 1 site (MG) the anterior chamber was completely filled with air for 1 hour followed by partial air removed at the slit lamp before sending the patient home. At the other site (FP) the anterior chamber was completely filled with air for 8 minutes, the majority of the air was removed and replaced with balanced salt solution, a drop of homatropine 5% was instilled to prevent pupillary block, tobramycin/dexamethasone ointment was placed in the eye, and patients remained lying face up for 30 minutes in the recovery room to allow the remaining small air bubble to push the donor tissue up against the recipient cornea before being sent home.

Descemet’s Stripping Automated Endothelial Keratoplasty Postoperative Care

The subjects undergoing DSAEK received either (1) prednisolone acetate 1% 4 times daily for 2 months, and then dosing was tapered by 1 drop per month down to 1 drop per day dosing, continued indefinitely, or (2) tobramycin/dexamethasone ointment 4 times daily for the first week postoperatively, then prednisolone acetate 1% 4 times daily for 4 months, followed by a 1 drop per month taper down to 1 drop per day dosing, continued indefinitely. Steroid-responsive ocular hypertensive subjects received intraocular pressure-lowering agents as needed, and the prednisolone acetate 1% was usually changed to fluorometholone or loteprednol etabonate.

Specular Microscopy Ancillary Study Penetrating Keratoplasty Operative and Postoperative Care

Sixty-eight surgeons at 45 sites participated in the SMAS, whose subjects are included in this comparison. Surgical technique and postoperative care, including prescription of medications, were provided according to each investigator’s customary routine.12 The rate of primary donor failures and 5-year endothelial cell loss and graft survival were previously reported for the CDS and SMAS cohorts,1,12 but this is the first report of 6-month and 1-year graft survivals and of endothelial cell loss in clear grafts that had at least 1 postoperative specular image within a 15-month follow-up period from a subset of the SMAS cohort.

Specular Microscopy and Endothelial Cell Density Determination

Participating eye banks that contributed corneas to the DSAEK group and specular images of the donor to the reading center included Indiana Lions Eye and Tissue Transplant Bank (Indianapolis, IN), Lions Eye Institute for Transplant and Research (Tampa, FL), North Carolina Eye Bank (Winston-Salem, NC), Heartland Lions Eye Bank (St. Louis, MO), and SightLife (Seattle, WA); each had previously participated in the SMAS and were familiar with image capture and transmission procedures.1,9,11 All the eye banks that contributed to the SMAS group have been noted.1,11 As in the SMAS, a single image of the central endothelium of each study donor cornea was submitted electronically to the CWRU Specular Microscopy Reading Center (SMRC, Cleveland, OH) for ECD determination. If a donor image could not be analyzed by the SMRC or was not available, as in the SMAS, the eye bank-determined ECD was used for data analysis. Postoperative images of the central endothelium were captured by specular microscopy (Konan Medical Corp, Torrance, CA) or confocal microscopy (Nidek Inc., Fremont, CA) at the 6-month (range, 5–7 months) and 12-month (range, 9–15 months) study visits and transmitted to the SMRC for analysis. Only SMRC-determined postoperative ECDs were used for data analysis, as in the SMAS. Image capture, calibration, and analysis procedures for both the donor and postoperative images by the SMRC were as previously described.1,9,11

Statistical Methods

The primary outcome measure was endothelial cell loss at 12 months, and the secondary outcome measure was graft clarity at 12 months. Percent cell loss was calculated by subtracting postoperative ECD from baseline ECD and then dividing by baseline ECD and multiplying by 100. For cases in which the baseline donor specular image was not analyzed by the SMRC, the ECD determined by the eye bank was used, as was done in the SMAS.1

The Jaeb Center for Health Research (Tampa, FL), the coordinating center for the CDS and the SMAS, consulted on defining the comparative cohort for this study and provided the CWRU Vision Research Coordinating Center all available demographic and ECD data from a subset of 410 CDS/SMAS subjects who had clear grafts between 9 and 15 months post-PKP and at least 1 postoperative ECD determination by the SMRC. It was determined that 1-year specular images from 150 DSAEK eyes would be required to have 90% confidence of detecting a 10% difference in endothelial cell loss between DSAEK study eyes and SMAS PKP eyes. A 10% to 15% dropout rate was anticipated; thus, a total of 175 subjects were initially enrolled.

For normally distributed variables, descriptive statistics were reported as mean ± standard deviation and compared using a 2-sample Student t test. Otherwise, they were reported as median (25th and 75th quartile) and compared using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test, or they were expressed as a proportion and compared using chi-square analysis, as appropriate. A 3-way repeated-measures analysis of variance was carried out to examine changes over time in ECD while accounting for the effects of procedure groups (DSAEK or PKP) and diagnosis. Specifically, the within-subject variable was ECD at baseline, 6 months, and 12 months with procedure group (2 levels) and diagnosis (2 levels) being the between-subjects factors. Because of small numbers in the other endothelial dysfunction categories in the PKP group and none in the DSAEK group, the analysis was restricted to 2 diagnoses: Fuchs’ dystrophy and pseudophakic/aphakic corneal edema. Analysis of covariance was used to compare endothelial cell loss between groups while taking into account the effect of baseline ECD and diagnosis. All reported P values were 2 sided. All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS software (version 9.1, SAS Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

Donor and Recipient Characteristics

A total of 175 eyes undergoing DSAEK were enrolled in the study. However, 1 eye inadvertently was the fellow eye of a subject already enrolled, and 1 subject received a DSAEK after a previously failed DSAEK; thus, 173 eyes (173 subjects) were available for analysis.

Donor characteristics for the 2 groups are summarized in Table 1. The death to preservation and death to surgery times were comparable in the DSAEK and PKP groups. In the DSAEK group, the mean donor age was 3 years younger (P = 0.03) and the mean baseline ECD was 91 cells/mm2 greater than in the PKP group (P = 0.001).

Table 1.

Donor Characteristics in Descemet’s Stripping Automated Endothelial Keratoplasty and Specular Microscopy Ancillary Study Penetrating Keratoplasty Groups

| DSAEK (N = 173) Mean (SD) | SMAS PKP (N = 410) Mean (SD) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Death to preservation (hrs) | 7.3 (2.7) | 6.9 (2.8) | 0.12 |

| Death to surgery (days) | 3.7 (1.2) | 3.6 (1.0) | 0.28 |

| Donor age (yrs) | 54 (17) | 57 (15) | 0.03 |

| Endothelial cell density (cells/mm2) | 2782 (310) | 2691 (295) | 0.001 |

DSAEK = Descemet’s stripping automated endothelial keratoplasty; PKP = penetrating keratoplasty; SD = standard deviation; SMAS = Specular Microscopy Ancillary Study.

Recipient characteristics for the 2 groups are summarized in Table 2. The mean age was 2 years older in the DSAEK group (P = 0.02). Also, compared with the PKP group, the DSAEK group had a higher proportion with Fuchs’ dystrophy (85% vs. 64%) and a lower proportion with pseudophakic/aphakic corneal edema (13% vs. 32%, P<0.001). Preoperatively, the majority of eyes (88%) in the DSAEK group were pseudophakic. Sixteen phakic eyes underwent combined cataract surgery and DSAEK. Postoperatively, the PKP group had a higher proportion of phakic eyes than the DSAEK group (15% vs. 2%, P<0.0001) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Recipient Characteristics in Descemet’s Stripping Automated Endothelial Keratoplasty and Specular Microscopy Ancillary Study Penetrating Keratoplasty Groups

| DSAEK (N = 173) | SMAS PKP (N = 410) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, yrs (mean ± SD) | 72±11 | 70±8 | 0.02 |

| Sex, No. female (%) | 104 (60) | 251 (61) | 0.8 |

| Race, No. (%) | 0.30 | ||

| Caucasian | 169 (98) | 389 (95) | |

| African-American | 3 (2) | 14 (3) | |

| Hispanic, Asian, Other | 1 (<1) | 7 (2) | |

| Diagnosis, No. (%) | <0.0001 | ||

| Fuchs’ dystrophy | 147 (85) | 264 (64) | |

| Pseudophakic/aphakic corneal edema | 23 (13) | 130 (32) | |

| Other endothelial failure | 3 (2) | 9 (2) | |

| Posterior polymorphous dystrophy | 0 | 2 (<1) | |

| Interstitial keratitis | 0 | 5 (1%) | |

| Preoperative lens status, No. (%) | <0.0001 | ||

| Pseudophakic, anterior chamber | 0 | 56 (14) | |

| Pseudophakic, posterior chamber capsule supported | 148 (85) | 128 (31) | |

| Pseudophakic, posterior chamber sutured | 5 (3) | 1 (<1) | |

| Aphakic | 0 | 27 (7) | |

| Phakic | 20 (12) | 198 (48) | |

| Postoperative lens status, No. (%) | <0.0001 | ||

| Pseudophakic, anterior chamber | 0 | 38 (9) | |

| Pseudophakic, posterior chamber capsule supported | 164 (95) | 276 (67) | |

| Pseudophakic, posterior chamber sutured | 5 (3) | 25 (6) | |

| Aphakic | 0 | 9 (2) | |

| Phakic | 4 (2) | 62 (15) |

DSAEK = Descemet’s stripping automated endothelial keratoplasty; PKP = penetrating keratoplasty; SD = standard deviation; SMAS = Specular Microscopy Ancillary Study.

Graft Success

Of the 173 subjects in the DSAEK group who entered the study, 145 (84%) were examined and found to have clear grafts at 1 year; 15 (9%) had clear grafts at 6 months and returned to their referring doctors; 4 (2.3%) were lost to follow-up before the 6-month examination, 4 (2.3%) died; 1 (0.58%) withdrew; and 4 (2.3%) experienced a graft failure within the first 15 months.

The DSAEK group experienced no primary graft failures. Four eyes (2.3%) were regrafted with DSAEK; two were related to visually significant wrinkles in the graft, one was related to stromal haze that was subsequently determined to be in the recipient cornea, and one was precipitated by immunologic graft rejection. The PKP group (consisting of all 596 enrolled subjects from the SMAS) experienced 1 primary graft failure (0.2%). Eight additional eyes (1.3%) were regrafted, including 5 with endothelial decompensation, 2 with rejection, and 1 related to epithelial down-growth. The regraft rate did not differ significantly between the 2 groups (P = 0.50).

Endothelial Cell Loss

Of the 145 subjects in the DSAEK group with clear grafts at 12 months, 102 (70%) had analyzable specular images, 14 (10%) had clear grafts but the 12-month postoperative image was not analyzable, and the remaining 29 (20%) had clear grafts but no image was obtained. No significant difference in the percent cell loss was noted with the inclusion of the eye bank-determined ECD when an SMRC-determined ECD was not available on the donor (data not shown); the cell loss analysis includes combined eye bank- and SMRC-determined ECD on the donor image.

Compared with the PKP group, the DSAEK group had significantly higher endothelial cell loss at 6 months (34±22% vs. 11±20%, P<0.001) and 12 months (38±22% vs. 20±23%, P<0.001) (Table 3). Adjustment for the difference in the baseline ECD between the 2 groups resulted in the same conclusion and level of statistical significance (P<0.001). The DSAEK surgeons were allowed to use their own preferred techniques, just as the CDS PKP surgeons were. Separate comparisons of each individual DSAEK surgeon’s cohort with the PKP cohort resulted in the same finding that 1-year endothelial cell loss was significantly higher with DSAEK (P≤0.001).

Table 3.

Endothelial Cell Density and Cell Loss for Descemet’s Stripping Automated Endothelial Keratoplasty and Specular Microscopy Ancillary Study Penetrating Keratoplasty Groups

| DSAEK |

SMAS PKP |

P Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | No. of Eyes | Mean (SD) | No. of Eyes | ||

| Endothelial cell density (cells/mm2) | |||||

| Baseline | 2778 (309) | 173 | 2691 (295) | 410 | 0.002 |

| 6 mos | 1838 (628) | 131 | 2411 (583) | 204 | <0.001 |

| 1 yr | 1743 (629) | 111 | 2154 (665) | 320 | <0.001 |

| Endothelial cell loss (%) | |||||

| 6 mos | 34 (22) | 131 | 11 (20) | 204 | <0.001 |

| 1 yr | 38 (22) | 111 | 20 (23) | 361 | <0.001 |

DSAEK = Descemet’s stripping automated endothelial keratoplasty; PKP = penetrating keratoplasty; SMAS = Specular Microscopy Ancillary Study.

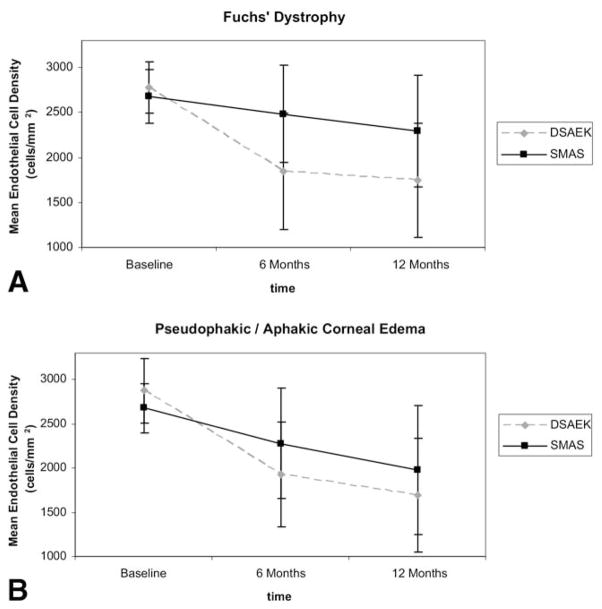

An additional analysis of change in ECD over time was performed, taking into account the effect of preoperative diagnosis. Endothelial cell density changed significantly over time (P<0.001) and was significantly affected by treatment group (DSAEK vs. PKP, P<0.001). Although diagnosis and the interaction between treatment group and diagnosis were not significant factors in the analysis (P = 0.069 and P = 0.166, respectively), the interactions between time and treatment group (DSAEK vs. PKP) and between time and diagnosis were significant (P<0.001 and P = 0.013, respectively), indicating that ECD changed over time, but in different ways, depending on the keratoplasty procedure and diagnosis status, as shown in Figure 1A for Fuchs’ dystrophy and Figure 1B for pseudophakic/aphakic corneal edema. Notably, in the SMAS PKP group, the subjects with Fuchs’ dystrophy experienced significantly lower 12-month cell loss than the subjects with pseudophakic/aphakic corneal edema (16% vs. 28%, P = 0.0089), whereas in the DSAEK group, the 12-month cell loss was comparable for the 2 diagnoses (37% vs. 41%, P = 0.59). The difference in cell loss between subjects with Fuchs’ dystrophy and subjects with pseudophakic/aphakic corneal edema in the SMAS PKP group remained significant (P = 0.00057) even if eyes with anterior chamber intraocular lenses were excluded from the analysis.

Figure 1.

A, Mean ECD as a function of time for patients with Fuchs’ dystrophy in the DSAEK and SMAS PKP groups. B, Mean ECD as a function of time for patients with pseudophakic/aphakic corneal edema in the DSAEK and SMAS PKP groups. DSAEK = Descemet’s stripping automated endothelial keratoplasty; ECD = endothelial cell density; SMAS = Specular Microscopy Ancillary Study.

Complications

The most frequent postoperative complication in both cohorts was an intraocular pressure spike exceeding 25 mmHg (Table 4). Also, both groups experienced a 5% rate of immunologic graft rejection episodes (9/173 DSAEK cases and 21/410 PKP cases). Graft detachment in the immediate postoperative period was a complication unique to the DSAEK group and occurred in 10 of the 173 cases (5.8%). No pupillary block glaucoma occurred. Complications unique to the SMAS PKP group (N = 410) included wound leak in 15 cases (3.7%), unplanned vitreous loss in 8 cases (2.0%), persistent epithelial defect in 5 cases (1.2%), and corneal infection/ulceration in 1 case (<1%).

Table 4.

Complications and Adverse Events in Descemet’s Stripping Automated Endothelial Keratoplasty and Specular Microscopy Ancillary Study Penetrating Keratoplasty Groups

| DSAEK (N = 173) No. (%) | SMAS (N = 410) No. (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Elevated intraocular pressure (>25 mmHg) | 27 (16) | 113 (28) |

| Graft rejection episode | 9 (5.2) | 21 (5.1) |

| Graft detachment and repositioning | 10 (5.8) | NA |

| Anterior syncheciae | 2 (1.2) | 1 (<1) |

| Retinal detachment | 1 (<1) | 0 (0) |

| Pupillary block glaucoma | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Wound leak | 0 (0) | 15 (3.7) |

| Vitreous loss (unplanned) | 0 (0) | 8 (2.0) |

| Capsule rupture | 0 (0) | 6 (1.5) |

| Persistent epithelial defect | 0 (0) | 5 (1.2) |

| Re-suture | NA | 2 (<1) |

| Corneal infection/ulceration | 0 (0) | 1 (<1) |

| Severe intraocular inflammation | 0 (0) | 1 (<1) |

| Suprachoroidal hemorrhage | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Endophthalmitis | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

DSAEK = Descemet’s stripping automated endothelial keratoplasty; NA = not available; PKP = penetrating keratoplasty; SMAS = Specular Microscopy Ancillary Study.

Discussion

We have demonstrated that the 1-year graft survival was comparable for DSAEK and PKP, whereas cell loss in the DSAEK group at both 6 months (34%) and 12 months (38%) postoperatively was significantly greater than observed in the historical PKP group from the SMAS at 6 months (11%) and 12 months (20%), with essentially the same donor and recipient characteristics and ECD determined by the same reading center. This degree of cell loss within the first year confirms the observations of other investigators at single sites,5–8 but is significantly less than the 61% cell loss reported at 1 year by another investigator.14 Thus, we confirm that, at least initially, the DSAEK procedure results in significantly greater loss of cells than PKP, particularly within the first 6 months of the procedure, probably because of multiple factors but principally related to greater surgical manipulation and trauma to the graft. Longer term, 5-year data on endothelial cell survival after DSAEK, with objective determination of the ECD by a central reading center (similar to the SMAS), would provide a more definitive determination of behavioral differences in the endothelial cell population of the DSAEK and PKP groups over time.

In the SMAS PKP group, the subjects with pseudophakic/aphakic corneal edema experienced significantly greater cell loss at 12 months than the subjects with Fuchs’ dystrophy, which may relate to the 4 times greater failure rate in this group independently of lens status noted at 5 years.15 In contrast, in the DSAEK group, the 12-month cell loss was comparable for the 2 diagnoses. The greater early cell loss associated with the DSAEK surgical procedure may have masked differences associated with recipient diagnosis in the 1-year study time frame. Longer follow-up is needed to fully assess how different recipient diagnoses affect long-term cell loss after DSAEK.

A major value of the central reading center is to provide ECD data on specular images of varying quality by certified readers whose readings are subjected to dual grading, adjudication, if differing by greater than 5%, and intraobserver retesting to confirm reliability, as was used with the SMAS and similarly with this study.1,9,11 By using this methodology, we found that the DSAEK group demonstrated similar endothelial cell loss at 6 and 12 months postoperatively, as has been reported from experienced surgeons at individual sites using differing cell counting methodologies and single readers and without testing for inter- and intraobserver variability.5–8 The results of this study, however, are not necessarily applicable to less experienced DSAEK surgeons whose staff do not necessarily perform specular microscopy on a routine basis.

The most frequent postoperative complication in both the DSAEK and PKP groups was intraocular pressure elevation greater than 25 mmHg. In addition, both groups experienced a 5% rate of initial immunologic graft rejection episodes within the first year. The rates of intraocular pressure elevation and immunologic rejection episodes were within ranges previously reported.16–20

Certain complications were unique to each procedure. Graft detachment was unique to DSAEK, because the graft is just held in place initially with an air bubble rather than with sutures. The graft detachment rate in this study was within the range reported in previous endothelial keratoplasty studies.2,3,5–8,13,21,22 Complications unique to the SMAS PKP cohort included wound leak or dehiscence, vitreous loss, persistent epithelial defect, and corneal infection/ulceration. These complications are associated with the open sky approach, severing all corneal nerves, a relatively large incision, and long-standing sutures, which are inherent elements of the PKP procedure. Descemet’s stripping automated endothelial keratoplasty avoids these complications because it is performed through a relatively small incision, corneal innervation is retained, the eye remains essentially closed, and sutures, if used at all, are removed relatively early.2

This study comparing DSAEK outcomes with SMAS PKP outcomes had several limitations. First, the subjects were not randomized to the 2 procedures with the same donor, although donor and recipient characteristics were well matched. Second, 2 experienced surgeons performed the DSAEK cases; thus, results cannot be necessarily extrapolated to surgeons initiating the DSAEK procedure into their practice or using it infrequently. In contrast, the SMAS PKP cases were performed at 45 clinical sites with varying surgical experience. This distribution of both academic and private practice sites with varying volume was purposely chosen to provide as broad a view of the performance of PKP as related to donor age as possible. However, PKP survivals have been shown to be higher for PKPs performed at high-volume centers,19 and this effect may have had some influence in the SMAS. Third, ideally comparative visual and refractive results to accompany the graft success and cell loss data would have provided further insights into the performance of both procedures. However, the CDS and SMAS did not track this information, and thus, the authors decided to similarly not track for the prospective DSAEK cases. Nevertheless, other studies have done so for both PKP and DSAEK, suggesting visual performance is comparable whereas astigmatism is significantly less with DSAEK.2,3,6,13,19,23–25 Fourth, although the same donor and recipient inclusion/exclusion criteria were used for the 2 groups, the rate of Fuchs’ dystrophy cases was significantly higher in the DSAEK group, and the rate of pseudophakic corneal edema cases was correspondingly lower. In previous PKP studies, the long-term graft survival was significantly higher in Fuchs’ dystrophy groups than in pseudophakic corneal edema groups.15,19,26 Although endothelial cell loss did not differ significantly with recipient diagnosis at 1 year in this prospective DSAEK study, longer follow-up is needed to more fully assess the effect of recipient characteristics and compare long-term graft survival of DSAEK with PKP.

An additional factor affecting this comparative study was that the lens status differed significantly between the DSAEK and PKP cohorts. The crystalline lens is frequently removed before DSAEK as either a staged or combined procedure, because this creates more space in the anterior chamber, which can facilitate insertion and positioning of the DSAEK graft.2 In contrast, it is more common in patients with Fuchs’ dystrophy to replace the crystalline lens after PKP, because the lens replacement procedure can be used to help correct some of the unpredictable refractive shifts induced by the PKP procedure. Thus, the PKP cohort had a higher proportion of phakic eyes. In addition, both DSAEK surgeons who participated in this study prefer to replace an anterior chamber intraocular lens with a sutured posterior chamber intraocular lens as a staged procedure before performing DSAEK. Thus, none of the DSAEK eyes had an anterior chamber intraocular lens postoperatively, whereas 9% of the PKP eyes did. Anterior chamber intraocular lenses have been associated with a higher rate of endothelial cell loss and graft failure after PKP in one series26 but not another series.27

In conclusion, Descemet’s stripping automated endothelial keratoplasty performed by experienced surgeons resulted in a higher 6-month and 12-month percent cell loss than PKP with comparable graft survival and comparable donor and recipient characteristics. Longer-term graft success and cell loss data involving DSAEK surgeons with varying experience are needed, using a central reading center to ensure accurate and nonbiased determination of ECD.

Acknowledgments

Supported by the National Eye Institute, Bethesda, MD (EY15145, EY12728); Eye Bank Association of America, Washington, DC; Vision Share, Apex, NC; Cornea Research Foundation of America, Indianapolis, IN; Research to Prevent Blindness, New York, NY; and Ohio Lions Eye Research Foundation, Grove City, OH.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure(s):

The author(s) have made the following disclosure(s):

Drs. Price have received travel grants from Moria (Antony, France).

References

- 1.Cornea Donor Study Investigator Group. Donor age and corneal endothelial cell loss 5 years after successful corneal transplantation: Specular Microscopy Ancillary Study results. Ophthalmology. 2008;115:627–32. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2008.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Price MO, Price FW. Descemet’s stripping endothelial keratoplasty. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2007;18:290–4. doi: 10.1097/ICU.0b013e3281a4775b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gorovoy MS. Descemet-stripping automated endothelial keratoplasty. Cornea. 2006;25:886–9. doi: 10.1097/01.ico.0000214224.90743.01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Melles GR. Posterior lamellar keratoplasty: DLEK to DSEK to DMEK. Cornea. 2006;25:879–81. doi: 10.1097/01.ico.0000243962.60392.4f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Price MO, Price FW., Jr Endothelial cell loss after Descemet stripping with endothelial keratoplasty: influencing factors and 2-year trend. Ophthalmology. 2008;115:857–65. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koenig SB, Covert DJ, Dupps WJ, Jr, Meisler DM. Visual acuity, refractive error, and endothelial cell density six months after Descemet stripping and automated endothelial keratoplasty (DSAEK) Cornea. 2007;26:670–4. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e3180544902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Terry MA, Chen ES, Shamie N, et al. Endothelial cell loss after Descemet’s stripping endothelial keratoplasty in a large prospective series. Ophthalmology. 2008;115:488–96. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.10.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Busin M, Bhatt PR, Scorcia V. A modified technique for Descemet membrane stripping automated endothelial keratoplasty to minimize endothelial cell loss. Arch Ophthalmol. 2008;126:1133–7. doi: 10.1001/archopht.126.8.1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Benetz BA, Gal RL, Ruedy KJ, et al. Cornea Donor Study Group. Specular Microscopy Ancillary Study methods for donor endothelial cell density determination of Cornea Donor Study images. Curr Eye Res. 2006;31:319–27. doi: 10.1080/02713680500536738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cornea Donor Study Group. Baseline donor characteristics in the Cornea Donor Study. Cornea. 2005;24:389–96. doi: 10.1097/01.ico.0000151503.26695.f0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cornea Donor Study Group. An evaluation of image quality and accuracy of eye bank measurement of donor cornea endothelial cell density in the Specular Microscopy Ancillary Study. Ophthalmology. 2005;112:431–40. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2004.10.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cornea Donor Study Investigator Group. The effect of donor age on corneal transplantation outcome results of the Cornea Donor Study. Ophthalmology. 2008;115:620–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2008.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Price MO, Price FW., Jr Descemet’s stripping with endothelial keratoplasty: comparative outcomes with microkeratome-dissected and manually dissected donor tissue. Ophthalmology. 2006;113:1936–42. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.05.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mearza AA, Qureshi MA, Rostron CK. Experience and 12-month results of Descemet-stripping endothelial keratoplasty (DSEK) with a small-incision technique. Cornea. 2007;26:279–83. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e31802cd8c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sugar A, Tanner JP, Dontchev M, et al. Cornea Donor Study Investigator Group. Recipient risk factors for graft failure in the Cornea Donor Study. Ophthalmology. 2009;116:1023–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2008.12.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Allan B, Terry MA, Price FW, Jr, et al. Corneal transplant rejection rate and severity after endothelial keratoplasty. Cornea. 2007;26:1039–42. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e31812f66e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Price MO, Jordan CS, Moore G, Price FW., Jr Graft rejection episodes after Descemet stripping with endothelial keratoplasty: Part two: the statistical analysis of probability and risk factors. Br J Ophthalmol. 2009;93:391–5. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2008.140038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vajaranant TS, Price MO, Price FW, et al. Visual acuity and intraocular pressure after Descemet-stripping endothelial keratoplasty in patients with and without preexisting glaucoma. Ophthalmology. 2009;116:1644–50. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.05.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Williams KA, Lowe MT, Bartlett CM, et al. The Australian Corneal Graft Registry 2007 Report. Adelaide, Australia: Flinders University Press; 2007. [Accessed July 19, 2009]. pp. 124–7. Available at: http://dspace.flinders.edu.au/dspace/bitstream/2328/1723/3/FINAL%20COMPILED%20REPORT%202007.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brandt JD, Lim MC, O’Day DG. Glaucoma after penetrating keratoplasty. In: Krachmer JH, Mannis MJ, Holland EJ, editors. Cornea. 2. Vol. 2. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Mosby; 2005. pp. 1575–90. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kitzmann AS, Goins KM, Reed C, et al. Eye bank survey of surgeons using precut donor tissue for Descemet stripping automated endothelial keratoplasty. Cornea. 2008;27:634–9. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31815e4011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Terry MA, Shamie N, Chen ES, et al. Endothelial keratoplasty: the influence of preoperative donor endothelial cell densities on dislocation, primary graft failure, and 1-year cell counts. Cornea. 2008;27:1131–7. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e3181814cbc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pineros O, Cohen EJ, Rapuano CJ, Laibson PR. Long-term results after penetrating keratoplasty for Fuchs’ endothelial dystrophy. Arch Ophthalmol. 1996;114:15–8. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1996.01100130013002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Claesson M, Armitage WJ, Fagerholm P, Stenevi U. Visual outcome in corneal grafts: a preliminary analysis of the Swedish Corneal Transplant Register. Br J Ophthalmol. 2002;86:174–80. doi: 10.1136/bjo.86.2.174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Price FW, Jr, Whitson WE, Marks RG. Progression of visual acuity after penetrating keratoplasty. Ophthalmology. 1991;98:1177–85. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(91)32136-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thompson RW, Jr, Price MO, Bowers PJ, Price FW., Jr Long-term graft survival after penetrating keratoplasty. Ophthalmology. 2003;110:1396–402. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(03)00463-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lass JH, DeSantis DM, Reinhart WJ, et al. Clinical and morphometric results of penetrating keratoplasty with 1-piece anterior chamber or suture-fixated posterior chamber lenses in the absence of lens capsule. Arch Ophthalmol. 1990;108:1427–31. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1990.01070120075032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]