Abstract

Circulating factors in preeclamptic women are thought to cause endothelial dysfunction and thereby contribute to the progression of this hypertensive condition. Despite the involvement of neurological complications in preeclampsia, there is a paucity of data regarding the effect of circulating factors on cerebrovascular function. Using a rat model of pregnancy, we investigated blood-brain barrier permeability, myogenic activity, and the influence of endothelial vasodilator mechanisms in cerebral vessels exposed intraluminally to plasma from normal pregnant or preeclamptic women. Additionally, the role of vascular endothelial growth factor signaling in mediating changes in permeability in response to plasma was investigated. A three-hour exposure to 20% normal pregnant or preeclamptic plasma increased blood-brain barrier permeability by approximately 6.5- and 18-fold, respectively, compared to no plasma exposure (p<0.01). Inhibition of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor kinase activity prevented the increase in permeability in response to preeclamptic plasma, but had no effect on changes in permeability of vessels exposed to normal pregnant plasma. Circulating factors in preeclamptic plasma did not affect myogenic activity or the influence of endothelium on vascular tone. These findings demonstrate that acute exposure to preeclamptic plasma has little effect on reactivity of cerebral arteries, but significantly increases blood-brain barrier permeability. Prevention of increased permeability by inhibition of vascular endothelial growth factor signaling suggests that activation of this pathway may be responsible for increased blood-brain barrier permeability following exposure to preeclamptic plasma.

Keywords: circulating factors, plasma, preeclampsia, blood-brain barrier, permeability, vascular endothelial growth factor

INTRODUCTION

Preeclampsia affects 3 – 8% of all pregnancies and represents a major cause of maternal and perinatal morbidity1. Although the pathophysiology behind the development of preeclampsia remains elusive and highly debated, one theory is that abnormal remodeling of uteroplacental bed spiral arteries leads to placental hypoperfusion, prompting release of factors into the maternal circulation2–4. These circulating factors include angiogenic and antiangiogenic molecules like soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase 1 receptor (sflt-1) and select cytokines3,5. For example, sflt-1, the soluble receptor for vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) receptor-1 (VEGFR1), is elevated in preeclamptic plasma and has been shown to inhibit certain actions of VEGF.3,5 In this manner, sflt-1 is thought to provoke endothelial dysfunction resulting in decreased endothelium-dependent vasodilation and increased vessel reactivity. Such changes may increase total peripheral vascular resistance contributing to a major feature of preeclampsia, namely hypertension2–4.

One of the most serious sequelae of preeclampsia are eclamptic seizures, a leading cause of maternal and fetal morbidity and mortality1. Clinical and experimental findings suggest the pathophysiology behind eclampsia involves a failure of autoregulation leading to decreased cerebral vascular resistance (CVR), transmission of increased pressure to the microcirculation, and blood-brain barrier (BBB) disruption6–9. Increased BBB permeability can result in the passage of damaging plasma constituents and protein into brain parenchyma, causing vasogenic edema and the neurological complications of severe preeclampsia and eclampsia6–9. Despite intensive investigation into the involvement of circulating factors in the etiology of preeclampsia, there is a paucity of data regarding their role in promoting of cerebrovascular damage, including enhanced BBB permeability and changes in vascular reactivity that could affect CVR and local perfusion.

The first goal of this study was to evaluate the effect of normal pregnant and preeclamptic plasma on BBB permeability by measuring hydraulic conductivity (Lp) of blood vessels exposed to plasma. Lp was evaluated as this parameter relates the filtration of water across the BBB in response to hydrostatic pressure10. Our second goal was to investigate the involvement of VEGF and related signaling in mediating changes in BBB permeability in response to plasma exposure. This cytokine was chosen as it is an angiogenic molecule with potent vascular permeability properties, and has been shown to increase BBB permeability10–13. In addition, while preeclampsia is associated with elevated sflt-1 levels that are thought to inactivate the actions of VEGF,3,5 the residual biological activity of VEGF in preeclamptic plasma is not known, especially with regards to BBB function. Finally, we investigated the effect of circulating factors in the plasma of normal pregnant and preeclamptic women on cerebral artery reactivity and endothelium-dependent vasodilator responses, two components that can affect CVR.

METHODS

Patients and Plasma Samples

Blood samples were collected from patients enrolled in a simultaneous ongoing Institutional Review Board (IRB) approved study at the University of Vermont. IRB exemption was granted to use these previously frozen plasma samples, for which patients had given informed consent. Plasma was pooled from two groups: a control group of normotensive pregnant women with uncomplicated pregnancies, and a group of preterm pregnant preeclamptic women. The control group (n=12) had an average age of 33.4 years (range 20 – 41) and had no history of hypertension, diabetes, or infection. The average gestational age at venipuncture was 34.4 weeks (range 31.9 – 36.3). The preeclamptic group (n=5) was comprised of women diagnosed with severe preeclampsia using American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists criteria of having > 5 g of protein measured in a 24-hour urine collection or the presence of intrauterine growth restriction as defined by fetal weight < 5% on the Vermont Hybrid growth curve in addition to blood pressure readings > 140 systolic and > 90 diastolic on at least two occasions, 6 hours apart. The preeclamptic group had an average age of 28 years (range 23 – 32), and average gestational age at venipuncture was 32.2 weeks (range 28.3 – 36.4). Effort was taken to use plasma from preterm preeclamptic women, as the earlier development of this disease is thought to represent a unique phenotype14. Blood samples were collected from patients into vacutainer tubes containing either ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid or lithium heparin. Blood was centrifuged at 1400–1600 g, the plasma removed, aliquoted, and the pooled samples frozen at −80 °C until experimentation.

Animals

All procedures were approved by the University of Vermont Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and complied with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Female late-pregnant Sprague-Dawley rats (d20, 390–402 g) were used for all experiments and housed in an Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care accredited facility. Animals had access to food and water ad libitum, and maintained a 12 hour light/dark cycle.

Venous Permeability Studies

The effect of normal pregnant and preeclamptic plasma on Lp of cerebral veins was determined as previously described with slight modification15. Veins were perfused with either physiologic HEPES saline solution only (n=9), normal pregnant plasma (n=5) or preeclamptic plasma (n=5). Veins were first exposed intraluminally to 20% plasma in HEPES buffer from each group for 3 hours at 10 ± 0.3 mmHg. Plasma was then flushed out of the venous lumen and Lp determined without the presence of plasma in the lumen. This procedure avoided potential differences in colloid oncotic pressure in the different pools of plasma that could influence Lp measurements by having a common perfusate and suffusate.

A separate set of experiments was completed to investigate the potential contribution of VEGF and VEGF receptor signaling on changes in BBB permeability in response to plasma by the addition of VEGF receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor-II (VEGFR-II; 200 nmol/L; Calbiochem 676481) to normal pregnant (n=6) and preeclamptic plasma (n=6) prior to intraluminal perfusion. The biological activities of VEGF in the vasculature are mediated by binding of VEGF to one of 2 receptor tyrosine kinases, VEGFR1 and VEGFR2.13 According to the manufacturer, VEGFR-II is a pyridinyl-anthranilamide compound that is highly specific for inhibiting VEGFR1 and VEGFR2 and demonstrates >10-fold potency at VEGFR2 (fetal liver kinse-1, flk-1) than at VEGFR1 (flt-1) or c-Kit. This inhibitor is thought to have minimal or no effects on other kinases. Thus, while this inhibitor is non-selective for VEGFR1 vs. VEGFR2, it is thought to be specific for VEGF receptor tyrosine kinase activity.

The level of total VEGF in normal pregnant and preeclamptic plasma used for permeability studies was determined using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA, hVEGF, R&D Systems, DY293B, Minneapolis, MN) and compared to plasma from normotensive nonpregnant women. VEGF in the pooled human plasma samples (0.5 ml) was concentrated on C18 Sep-Pak solid-phase cartridge minicolumns (Waters, Milford, MA), as previously described16. VEGF recovery from the column was approximately 70%. The hVEGF ELISA was modified from manufacturer’s instructions. After microplate coating with capture antibody, sample incubation (4 h), biotinylated detection antibody addition (3 h) and strepavidin-horse radish peroxidase processing for tetramethylbenzidine substrate development, the optical density in each well was measured at 450 nm with background correction. The hVEGF antiserum recognizes both VEGF121 and VEGF165 isoforms and there is no apparent crossreactivity with placental growth factor (PlGF), hVEGF-C or hVEGF-D.

Arterial Reactivity Studies

In order to determine the effects of normal pregnant and preeclamptic plasma on vascular reactivity, vessels were perfused with either normal pregnant (n=6) or preeclamptic plasma (n=6). The protocol for measuring vessel reactivity was as previously described17. Briefly, a third-order branch of the posterior cerebral artery (PCA) was carefully dissected, mounted on glass cannulas in an arteriograph chamber and perfused with 20% plasma from either pregnant or preeclamptic women in HEPES buffer. The suffusate consisted of HEPES solution only. All vessels were exposed to 20% plasma in HEPES buffer intraluminally for 3 hours as the plasma was left in the vessel for the entire reactivity protocol.

Drugs and Solutions

HEPES physiologic salt solution was made fresh daily and consisted of (mmol/L): 142.0 NaCl, 4.7 KCl, 1.71 MgSO4, 0.50 EDTA, 2.8 CaCl2, 10.0 HEPES, 1.2 KH2PO4 and 5.0 dextrose. Nώ-nitro-L-arginine (L-NNA), indomethacin, and papaverine were made fresh weekly at 10−2 mol/L or 10−3 mol/L stock solutions and stored at 4°C. VEGF was purchased from Sigma and kept frozen until use. HEPES and indomethacin were purchased from Fisher Scientific (Hampton, NH); papaverine, L-NNA, and A23187 (calcium ionophore) were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). VEGFR-II was purchased through Calbiochem (Gibbstown, NJ).

Statistical analysis

All data are presented as mean ± SE. Differences in blood pressures, Lp and between control and preeclamptic plasma as well as between different vessels with the same plasma were determined using Student’s t-test or one-way analysis of variance, where appropriate. A posthoc analysis for multiple comparisons was performed with Student-Newman-Kuels test where appropriate. Differences were considered significant at p<0.05.

RESULTS

Effect of plasma on hydraulic conductivity

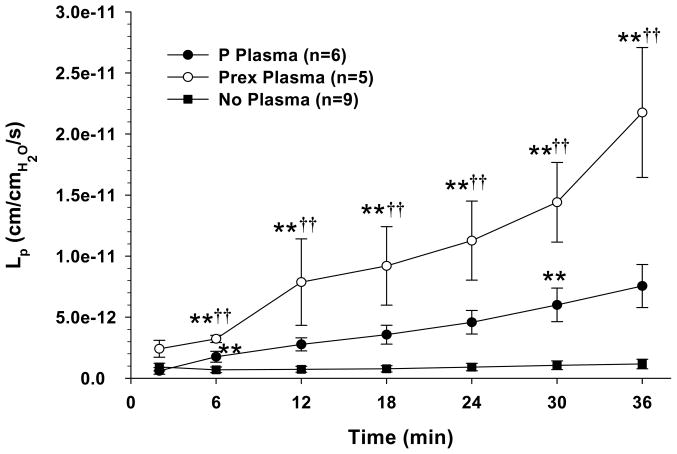

Changes in Lp vs. time for cerebral veins are shown in Figure 1. Cerebral veins exposed to plasma from both normal pregnant and preeclamptic women had significant increases in Lp vs. no plasma exposure. In addition, veins exposed to HEPES buffer only (no plasma exposure) had a constant Lp during the duration of the experiment whereas veins exposed to pregnant or preeclamptic plasma had Lp that increased over time, suggesting loss of barrier properties over time with plasma exposure. The increase in BBB permeability was significantly greater in veins exposed to preeclamptic vs. normal pregnant plasma, suggesting circulating factors or other properties of plasma in preeclampsia have a greater influence on permeability than normal pregnant plasma.

Figure 1.

Graph showing hydraulic conductivity (Lp) as a function of time in cerebral veins perfused with either HEPES physiologic solution only (No Plasma), normal pregnant (P) plasma, or preeclamptic (Prex) plasma. Veins exposed to normal pregnant and preeclamptic plasma had increased Lp compared to no plasma exposure. In addition, veins exposed to preeclamptic plasma had Lp that was significantly increased vs. normal pregnant plasma. (**p<0.01 vs. no plasma; ††p<0.01 vs. P plasma)

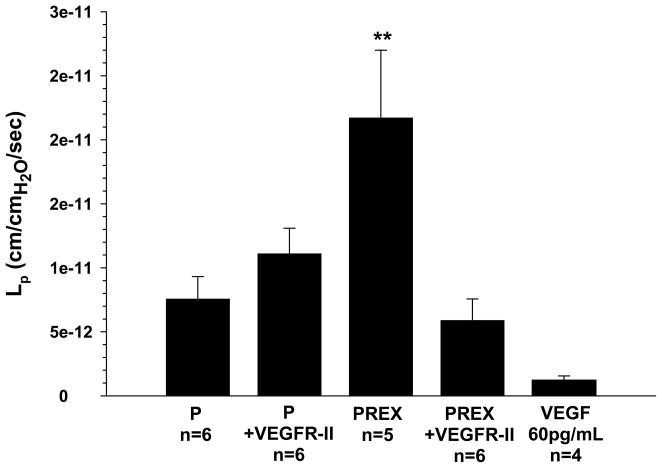

The role of VEGF signaling in mediating changes in BBB permeability was investigated by measuring Lp of veins exposed to pregnant and preeclamptic plasma with the addition of VEGFR-II, a VEGF receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor. The permeability of veins exposed to normal pregnant plasma was unaffected by VEGFR-II (Figure 2). However, addition of VEGFR-II to preeclamptic plasma completely prevented the increase in Lp, suggesting VEGF receptor tyrosine kinase signaling has an important role in increasing BBB permeability in response to preeclamptic plasma. To determine if increased VEGF receptor activation was due to higher VEGF levels in preeclamptic plasma, total peripheral circulating VEGF levels in both groups of plasma was measured via ELISA. Although the concentration of peripheral VEGF was similar between normal pregnant and preeclamptic plasma (62.0 pg/ml vs 61.4 pg/ml, respectively), it was considerably higher than the level of VEGF found in nonpregnant women (15.0 pg/ml).

Figure 2.

Graph showing hydraulic conductivity (Lp) at 36 minutes of cerebral veins exposed to normal pregnant (P) or preeclamptic (Prex) plasma with and without the addition of VEGFR-II to inhibit VEGF receptor tyrosine kinase activity in the plasma perfusate, or 60 pg/mL VEGF without plasma. Veins exposed to P plasma were unaffected by VEFGR-II. However, VEGFR-II prevented an increase of Lp in veins exposed to Prex plasma, suggesting VEGF receptor tyrosine kinase activity is involved in increased BBB permeability in response to Prex plasma. VEGF alone produced modest permeability that was significantly decreased from PREX plasma only. (**p<0.01 vs. all)

The determine if the level of VEGF measured in plasma affected Lp alone without plasma, a separate set of experiments (n=4) was done in which 60 pg/mL was perfused in cerebral veins and Lp measured. We found that 60 pg/mL VEGF perfused in cerebral veins produced modest permeability that was lower than both plasmas, but was only significantly different from PREX plasma.

Effect of plasma on myogenic reactivity and tone

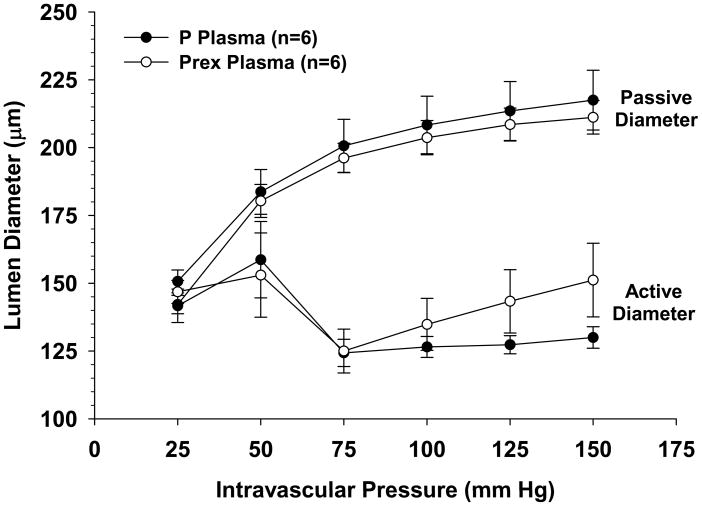

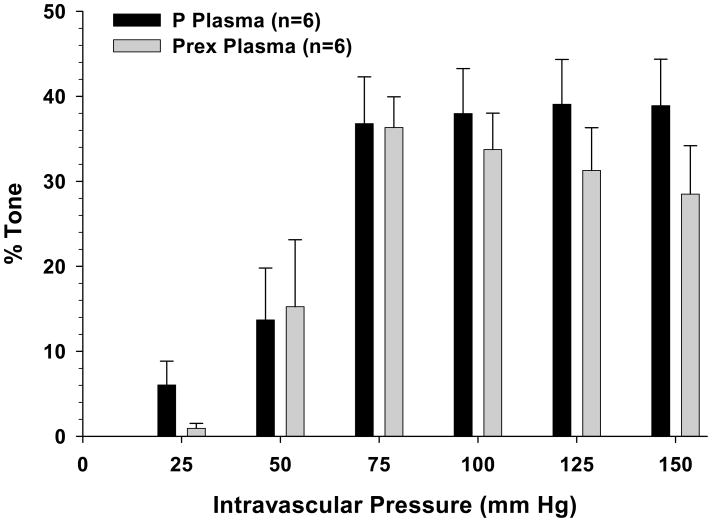

The active response of PCAs perfused with plasma from either normal pregnant or preeclamptic women to stepwise increases of intravascular pressure are shown in Figure 3 together with their respective passive diameters. As seen in the active diameter vs. pressure curves, all vessels dilated at pressures below the myogenic pressure range, from 25 – 50 mmHg, then constricted and exhibited myogenic reactivity as pressure was increased to 75 mmHg. PCAs perfused with pregnant plasma demonstrated considerable myogenic activity as demonstrated by the amount of vasoconstriction maintained in response to increased intravascular pressure. PCAs perfused with preeclamptic plasma had similar overall reactivity, though they had non-significant increases in lumen diameters at higher pressures (125 – 150 mmHg). All PCAs had similar passive diameters. In addition, all arteries had considerable pressure-induced myogenic tone within the autoregulatory range between 75 and 150 mmHg that was similar regardless of the type of plasma perfusate (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Graph showing active and passive diameter vs. pressure curves for posterior cerebral arteries (PCAs) perfused with either normal pregnant (P) or preeclamptic (Prex) plasma. Arteries perfused with both types of plasma constricted and exhibited similar myogenic reactivity at pressures > 50 mmHg. Passive diameters of PCAs perfused with P and Prex plasma were similar at all intravascular pressures studied.

Figure 4.

Graph showing percent tone vs. pressure of posterior cerebral arteries (PCAs) perfused with either normal pregnant (P) or preeclamptic (Prex) plasma. Acute exposure to plasma did not affect tone in either group.

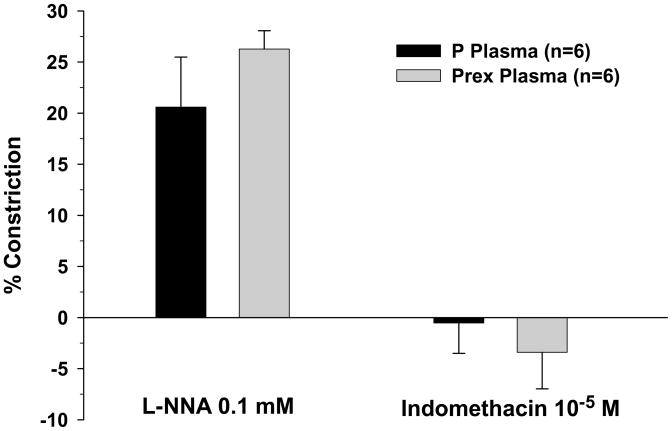

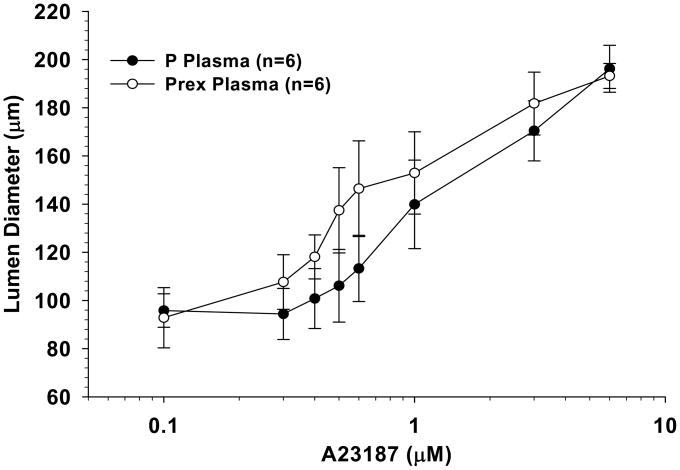

Influence of nitric oxide (NO), cyclooxygenase (COX), and endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor (EDHF) on vascular tone

PCAs perfused with both pregnant plasma and preeclamptic plasma constricted in response to NO synthase (NOS) inhibition with L-NNA, suggesting the basal influence of NO to inhibit vascular tone was present in both groups (Figure 5). There was no difference in the amount of constriction between arteries perfused with different plasma types. The addition of indomethacin to inhibit COX caused minimal changes to vessel diameters regardless of the type of plasma perfusate (Figure 5). The influence of EDHF in PCAs perfused with normal pregnant or preeclamptic plasma was assessed by measuring vasodilation to the addition of A23187 in the presence of NOS and COX inhibition (Figure 6). This is a common approach for assessing EDHF-related mechanisms17. Under these conditions, A23187 caused dilation in all vessels that was not different between groups.

Figure 5.

Graph showing percent constriction of posterior cerebral arteries perfused with normal pregnant (P) plasma or preeclamptic (Prex) plasma to the addition of L-NNA and indomethacin to inhibit nitric oxide synthase and cyclooxygenase, respectively. All vessel and plasma combinations constricted similarly with the addition of L-NNA. The addition of indomethacin caused minimal changes in vessel diameter.

Figure 6.

Graph showing percent dilation of posterior cerebral arteries perfused with normal pregnant (P) plasma or preeclamptic (Prex) plasma with the addition of A23187 in the presence of nitric oxide synthase and cyclooxygenase inhibition. All vessel and plasma combinations dilated similarly with the addition of A23187.

DISCUSSION

The major finding from this study was that BBB permeability was significantly increased by circulating factors in plasma from normal pregnant women, an effect that was further amplified in plasma from severely preeclamptic women. While plasma from normal pregnant women caused increased Lp of cerebral veins compared to no plasma, exposure to preeclamptic plasma led to an even greater disruption of BBB properties. Furthermore, the finding that VEGF receptor tyrosine kinase inhibition prevented the increase in permeability of veins exposed to preeclamptic, but not normal pregnant plasma, suggests that VEGF receptor tyrosine kinase activity is involved in increasing BBB permeability following exposure to preeclamptic plasma only. In contrast, we found acute exposure to circulating factors during preeclampsia did not affect cerebral artery reactivity, myogenic tone, and several endothelium-dependent responses.

It has been hypothesized that circulating factors in preeclampsia contribute to the development of brain edema and the neurological complications of severe preeclampsia.17–19 However, an effect of preeclamptic plasma on BBB permeability has not been previously examined. Results from this study indicate a three-hour intraluminal exposure to preeclamptic plasma significantly increased BBB permeability compared to normal pregnant plasma and no plasma exposure (Figures 1 and 2). Permeability was measured by determining Lp of cerebral veins, a critical parameter relating flux of water in response to hydrostatic pressure due to both transcellular and paracellular transport across the BBB.10 Cerebral veins were used for these experiments as they have been shown to be a primary site of BBB disruption during acute hypertension20,21 and in response to VEGF.22 Although this is the first report we know of showing that preeclamptic plasma increased Lp of cerebral veins, Neal et al. found exposure to preeclamptic plasma increased Lp of mesenteric microvessels from frogs.23 In that study, there was increased permeability of vessels exposed to plasma from women with severe but not mild preeclampsia. Preeclamptic plasma used in our study was pooled from women who also had the diagnosis of severe, preterm preeclampsia, suggesting circulating factors during this disease increase permeability of the BBB as well as systemic vessels, and may promote vasogenic brain edema seen with severe preeclampsia.

Our current results suggest that circulating factors in the plasma from preeclamptic women increases BBB permeability and that VEGF receptor tyrosine kinase activity is involved because VEGFR-II, a specific inhibitor of VEGF receptor tyrosine kinase activity, prevented the increase in permeability. This result was distinctly different from what was found with normal pregnant plasma which produced a more moderate increase in permeability and no change with VEGFR-II. However, the differential response of the BBB to pregnant vs. preeclamptic plasma, and the apparent involvement of VEGF receptor tyrosine kinase activity in preeclamptic plasma only, occurred despite similar levels of VEGF (60 pg/mL) in the two plasmas. These findings suggest that elevated levels of VEGF alone may not be responsible for the increase in permeability in response to preeclamptic plasma. In fact, we tested the response of 60 pg/mL VEGF alone on Lp of cerebral veins and found that this amount of VEGF caused modest permeability, lower than both plasmas. Together, these results suggest that VEGF alone is not the only circulating factor during either pregnancy or preelampsia that affects BBB permeability.

There are at least two possibilities to explain our findings. First, there may be circulating factors present in preeclamptic plasma that enhance effects of VEGF on permeability, as has been shown in other studies.24–27 PlGF, a member of the VEGF growth factor family that binds and activates VEGFR1, has been shown to enhance Lp compared to VEGF alone.24,25 PlGF is significantly elevated in both normal pregnant and preeclamptic plasma, however, it is unlikely PlGF is acting in this manner to enhance VEGF-induced permeability because studies have consistently found that levels of PlGF are decreased in preeclamptic plasma compared to normal pregnancy.28,29 However, there may be another yet unidentified factor that is elevated in preeclamptic plasma that may be acting to sensitize the BBB to VEGF-induced permeability. There are numerous cytokines and growth factors produced in preeclampsia2–4 that could activate downstream pathways and/or increase endothelial cell calcium and in this way sensitize the BBB to VEGF-induced permeability.

Second, there may be differences in VEGF isoforms present in preeclamptic vs. normal pregnant plasma. VEGFs are a family of six growth factors, including VEGF-A, B, C, D, E, and PlGF.13,30 VEGF-A, the most commonly secreted form, exerts its actions via the tyrosine kinase activity of VEGFR1 and VEGFR2 whereas other growth factors in this family are receptor-specific.13,30 For example, PlGF only binds and activates VEGFR1 whereas VEGF-C specifically activates VEGFR2.25,30,31 Although total VEGF was found to be similar in normal pregnant and preelcamptic plasma, the ELISA we used does not distinguish between different VEGF isoforms. Thus, it is possible that receptor specific isoforms are present in higher concentrations in preeclamptic plasma and activating different VEGFRs, compared to normal pregnant plasma, to increase Lp. In addition, a primary mechanism of hypertension and proteinuria in preeclampsia is thought to be due to diminished VEGF activity resulting from enhanced sflt-1 competitive binding that inhibits the interaction between VEGF and VEGFR1.3,5 Our finding that preeclamptic plasma appears to increase Lp through activation of VEGF receptors is somewhat contrary to these studies. However, because sflt-1 is specific for inhibiting VEGFR1 signaling, other isoforms that specifically bind VEGFR2, such as VEGF-C, may be elevated in preeclamptic plasma and cause an increase in permeability. It is worth noting that despite the importance of VEGF signaling in vascular function, the mechanisms by which VEGF increases vascular permeability, and the receptors involved, are still largely unknown. One limitation of this study was that the inhibitor we used was non-selective for VEGFR1 vs. VEGFR2 and further studies are needed to determine which receptors are involved in increasing permeability of the BBB in response to preeclamptic plasma and the exact cellular mechanisms by which this occurs.

Although preeclamptic plasma increased cerebral vein permeability, it had a negligible effect on cerebral artery reactivity, myogenic tone, or endothelium-dependent responses. This lack of effect may have been secondary to the acute exposure to plasma, as PCAs were exposed to plasma for a total duration of ~ 3 hours. Vascular function of these arteries may differ with chronic exposure to preeclamptic plasma. Another possible explanation for the lack of effect of preeclamptic plasma on arterial reactivity may be due to the discrepancy between the concentrations of plasma we used as a perfusate (20%) compared to physiologic values of about 55%. This concentration was used because of limited plasma availability. However, a prior study comparing 20 % vs. 40% normal pregnant plasma as a luminal perfusate found no differences in vascular reactivity.17 However, permeability was not measured in that study and thus, the use of 20% plasma may have underestimated effects at normal physiological levels. Nevertheless, these experiments suggest that acute exposure to circulating factors in preeclamptic plasma influence cerebrovascular function primarily by affecting the BBB and increasing the permeability of cerebral veins rather than the reactivity of cerebral arteries.

PERSPECTIVES

This is the first study we are aware of that examined the effect of circulating factors during preeclampsia on cerebral vascular function. The findings that factors during preeclampsia, but not normal pregnancy, significantly increase BBB permeability through a mechanism that involves VEGF receptor tyrosine kinase activity challenges current dogma that the pathophysiology underlying preeclampsia is invariably linked to decreased VEGF activity secondary to elevated sflt-1 levels. Additionally, although investigators have administered recombinant VEGF to animal models of preeclampsia in an attempt to reverse the phenotypical features of this disease32, our study cautions such treatment as this has the potential to increase BBB permeability. However, we are also not suggesting the use of VEGF receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors for treatment of preeclampsia as these compounds are used extensively as anti-cancer agents and are known to promote hypertension and renal damage.33 The VEGF receptor inhibitor used in this study was for mechanistic purposes only. However, our results raise questions regarding the potential mechanisms behind VEGF receptor tyrosine kinase activity in response to preeclamptic plasma, and further studies evaluating the effects of specific VEGFR-1 vs. VEGFR-2 activation or other circulating factors that enhances VEGF-induced permeability are warranted. The lack of effect of preeclamptic plasma on vascular reactivity, myogenic tone and endothelium-dependent vasodilation suggests increased BBB permeability from circulating factors may be the dominant factor behind the development of vasogenic edema and the neurological complications of severe preeclampsia and eclampsia.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding

We gratefully acknowledge the generous support of the Preeclampsia Foundation (OAA and MJC), the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NS045940 to MJC), the American Heart Association (EIA 0540082 to MJC) and the National Heart Lung and Blood institute (RO1 HL 71944 to IMB).

Acknowledgments

None.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest/Disclosure Statement

None.

References

- 1.Duley L. The global impact of pre-eclampsia and eclampsia. Semin Perinatol. 2009;33:130–137. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2009.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Conrad KP, Benyo DF. Placental cytokines and the pathogenesis of preeclampsia. Am J Reprod Immunol. 1997;37:240–249. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.1997.tb00222.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gilbert JS, Ryan MJ, LaMarca BB, Sedeek M, Murphy SR, Granger JP. Pathophysiology of hypertension during preeclampsia: linking placental ischemia with endothelial dysfunction. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;294:H541–H550. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01113.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Granger JP, Alexander BT, Llinas MT, Bennett WA, Khalil RA. Pathophysiology of preeclampsia: linking placental ischemia/hypoxia with microvascular dysfunction. Microcirculation. 2002;9:147–160. doi: 10.1038/sj.mn.7800137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Levine RJ, Maynard SE, Qian C, Lim KH, England LJ, Yu KF, Schisterman EF, Thadhani R, Sachs BP, Epstein FH, Sibai BM, Sukhatme VP, Karumanchi SA. Circulating angiogenic factors and the risk of preeclampsia. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:672–683. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa031884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cipolla MJ. Cerebrovascular function in pregnancy and eclampsia. Hypertension. 2007;50:14–24. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.106.079442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Koch S, Rabinstein A, Falcone S, Forteza A. Diffusion-weighted imaging shows cytotoxic and vasogenic edema in eclampsia. Am J Neurorad. 2001;22:1068–1070. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Euser AG, Cipolla MJ. Cerebral blood flow autoregulation and edema formation during pregnancy in anesthetized rats. Hypertension. 2007;49:334–340. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000255791.54655.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Foyouzi N, Norwitz ER, Tsen LC, Buhimschi CS, Buhimschi IA. Placental growth factor in the cerebrospinal fluid of women with preeclampsia. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2006;92:32–37. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2005.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kimelberg HK. Water homeostasis in the brain: basic concepts. Neuroscience. 2004;129:851–860. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.07.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dobrogowska DH, Lossinsky AS, Tarnawski M, Vorbrodt AW. Increased blood-brain barrier permeability and endothelial abnormalities induced by vascular endothelial growth factor. J Neurocytol. 1998;27:163–173. doi: 10.1023/a:1006907608230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Argaw AT, Gurfein BT, Zhang Y, Zameer A, John GR. VEGF-mediated disruption of endothelial CLN-5 promotes blood-brain barrier breakdown. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:1977–1982. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808698106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ferrara N, Gerber HP, LeCouter J. The biology of VEGF and its receptors. Nat Med. 2003;9:669–676. doi: 10.1038/nm0603-669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Murphy DJ, Stirrat GM. Mortality and morbidity associated with early-onset preeclampsia. Hypertens Pregnancy. 2000;19:221–231. doi: 10.1081/prg-100100138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roberts TJ, Chapman AC, Cipolla MJ. PPAR-gamma agonist rosiglitazone reverses increased cerebral venous hydraulic conductivity during hypertension. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2009;297:H1347–H1353. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00630.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brandenburg CA, May V, Braas KM. Identification of endogenous sympathetic neuron pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide (PACAP): depolarization regulates production and secretion through induction of multiple propeptide transcripts. J Neurosci. 1997;17:4045–4055. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-11-04045.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Amburgey OARS, Bernstein IM, Cipolla MJ. Resistance Artery Adaptation to Pregnancy Counteracts the Vasoconstricting Influence of Plasma from Normal Pregnant Women. Reproductive Sciences. 2009;17:29–39. doi: 10.1177/1933719109345288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bartynski WS, Boardman JF, Zeigler ZR, Shadduck RK, Lister J. Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome in infection, sepsis, and shock. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2006;27:2179–2190. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Karumanchi SA, Lindheimer MD. Advances in the understanding of eclampsia. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2008;10:305–312. doi: 10.1007/s11906-008-0057-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mayhan WG, Heistad DD. Permeability of blood-brain barrier to various sized molecules. Am J Physiol. 1985;248:H712–H718. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1985.248.5.H712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mayhan WG, Heistad DD. Role of veins and cerebral venous pressure in disruption of the blood-brain barrier. Circ Res. 1986;59:216–220. doi: 10.1161/01.res.59.2.216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mayhan WG. VEGF increases permeability of the blood-brain barrier via a nitric oxide synthase/cGMP-dependent pathway. Am J Physiol. 1999;276(5 Pt 1):C1148–C1153. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1999.276.5.C1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Neal CR, Hunter AJ, Harper SJ, Soothill PW, Bates DO. Plasma from women with severe pre-eclampsia increases microvascular permeability in an animal model in vivo. Clin Sci (Lond) 2004;107:399–405. doi: 10.1042/CS20040018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chang YS, Tarbell J, Jain RK, Munn LL. Kinetics of placenta growth factor/vascular endothelial growth factor synergy in endothelial hydraulic conductivity and proliferation. Microvasc Res. 2001;61:203–210. doi: 10.1006/mvre.2000.2298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Park JE, Chen HH, Winer J, Houck KA, Ferrara N. Placenta growth factor. Potentiation of vascular endothelial growth factor bioactivity, in vitro and in vivo, and high affinity binding to Flt-1 but not to Flk-1/KDR. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:25646–25654. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Autiero M, Waltenberger J, Communi D, Kranz A, Moons L, Lambrechts D, Kroll J, Plaisance S, De Mol M, Bono F, Kliche S, Fellbrich G, Ballmer-Hofer K, Maglione D, Mayr-Beyrle U, Dewerchin M, Dombrowski S, Stanimirovic D, Van Hummelen P, Dehio C, Hicklin DJ, Persico G, Herbert JM, Shibuya M, Collen D, Conway EM, Carmeliet P. Role of PlGF in the intra- and intermolecular cross talk between the VEGF receptors Flt1 and Flk1. Nat Med. 2003;9:936–943. doi: 10.1038/nm884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carmeliet P, Moons L, Luttun A, Vincenti V, Compernolle V, De Mol M, Wu Y, Bono F, Devy L, Beck H, Scholz D, Acker T, DiPalma T, Dewerchin M, Noel A, Stalmans I, Barra A, Blacher S, Vandendriessche T, Ponten A, Eriksson U, Plate KH, Foidart JM, Schaper W, Charnock-Jones DS, Hicklin DJ, Herbert JM, Collen D, Persico MG. Synergism between vascular endothelial growth factor and placental growth factor contributes to angiogenesis and plasma extravasation in pathological conditions. Nat Med. 2001;7:575–583. doi: 10.1038/87904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wikström AK, Larsson A, Eriksson UJ, Nash P, Nordén-Lindeberg S, Olovsson M. Placental growth factor and soluble FMS-like tyrosine kinase-1 in early-onset and late-onset preeclampsia. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;109:1368–1374. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000264552.85436.a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Polliotti BM, Fry AG, Saller DN, Mooney RA, Cox C, Miller RK. Second-trimester maternal serum placental growth factor and vascular endothelial growth factor for predicting severe, early-onset preeclampsia. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;101:1266–1274. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(03)00338-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Olsson AK, Dimberg A, Kreuger J, Claesson-Welsh L. VEGF receptor signalling - in control of vascular function. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7:359–371. doi: 10.1038/nrm1911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hillman NJ, Whittles CE, Pocock TM, Williams B, Bates DO. Differential effects of vascular endothelial growth factor-C and placental growth factor-1 on the hydraulic conductivity of frog mesenteric capillaries. J Vasc Res. 2001;38:176–186. doi: 10.1159/000051044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gilbert JS, Verzwyvelt J, Colson D, Arany M, Karumanchi SA, Granger JP. Recombinant vascular endothelial growth factor 121 infusion lowers blood pressure and improves renal function in rats with placentalischemia-induced hypertension. Hypertension. 2010;55:380–385. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.141937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Homsi J, Daud AI. Spectrum of activity and mechanism of action of VEGF/PDGF inhibitors. Cancer Control. 2007;14:285–294. doi: 10.1177/107327480701400312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]