Abstract

Regulatory T cells (Treg) offer potential for improving long-term outcomes in cell and organ transplantation. The non-human primate (NHP) model is a valuable resource for addressing issues concerning the transfer of Treg therapy to the clinic. Herein we discuss the properties of NHP Treg and prospects for their evaluation in allo- and xenotransplantation.

Keywords: Regulatory T cells, Non-human primates, Transplantation, Xenotransplantation

Treg and regulation of immune reactivity

The importance of regulatory T cells (Treg) in the control of immunity (1) and their involvement in tolerance to auto- and alloantigens (Ags) is well-documented in rodents and humans (2, 3). Treg offer potential for therapy (3–5), and the promise of avoiding many toxicities and morbidities associated with current immunosuppressive drug regimens that, except in rare circumstances, fail to promote clinical transplant tolerance. Treg offer the possibility of being highly-specific and effective, with potential to provide long-term tolerance. Naturally-occurring, conventional CD4+CD25+Treg (nTreg) that constitute approximately 10% of peripheral CD4+ T cells are the most extensively investigated. They are identified by intra-nuclear expression of the transcription factor forkhead/winged-helix box protein 3 (Foxp3) (6), which, at least in mice, is expressed selectively by Treg. Recent reviews (7, 8) describe their development and function. nTreg can suppress the activation, proliferation, differentiation and effector function of various immune cells, including CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, B cells, dendritic cells (DC) and natural killer cells (7) via different mechanisms, depending on the target and location of their action.

Human and NHP versus rodent Treg

Multiple ways of improving Treg activity to control alloimmunity are being pursued. Adoptive transfer of purified Treg is the most widely-studied approach. However, many practical concerns need to be addressed, while ethical issues limit the testing that can be done in humans. Moreover, rodent models of tolerance induction are rather poor predictors of tolerance in NHP and humans (9). This singles out the non-human primate (NHP) as a valuable pre-clinical resource, reinforced by the reported similarity in phenotype and function between human and NHP (rhesus macaque) Treg (10, 11) and the differences between the latter and rodent Treg, on which much experimental work has been done. Thus, unlike mouse Treg, human Treg constitute only a minor proportion of all CD25+ cells, with only CD4+CD25hi cells exhibiting regulatory properties. Furthermore, whereas Treg of conventional, specific pathogen-free mice are immunologically naïve cells, the majority of human Treg express a memory phenotype. Furthermore, while Foxp3 is clearly correlated with Treg suppressive function in mice, its expression in humans is also observed in activated T cells, that lack regulatory function.

Development of Treg therapeutic protocols

Adoptive cell therapies are at a very early stage of evaluation in NHP, and there are as yet no reports of conventional Treg therapy in NHP transplantation. However, in the rhesus macaque, Bashuda et al (12) administered autologous ‘suppressive T cells’ (approx 107/kg) rendered anergic by co-culture with donor alloAg in the presence of anti-CD80 and -CD86 monoclonal antibodies (mAbs). The anergic T cells were infused 13 days after renal transplantation to splenectomized recipients given brief cyclosporine A and cyclophosphamide therapy. Significantly, long-term graft survival and donor-specific tolerance were achieved in 50% of the recipients, demonstrating the potential of a regulatory T cell approach in NHP organ transplantation.

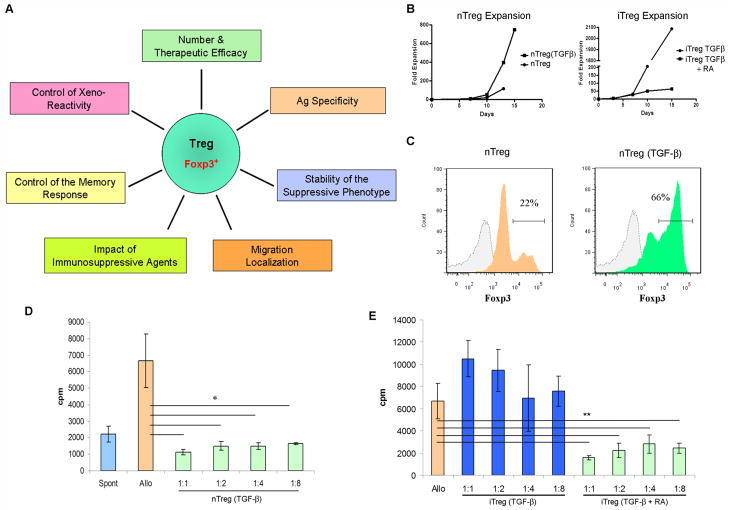

Realization of a therapeutic protocol based on adoptive transfer of Treg requires that multiple issues be addressed (Fig 1A): 1) the efficacy of Treg and the number of cells necessary to obtain a therapeutic effect; 2) the Ag specificity necessary for safe and effective control of rejection; 3) the stability of the suppressive phenotype of adoptively-transferred Treg; 4) the Treg migratory pattern that guarantees the strongest regulatory function; 5) the conditions permissive to regulation of the memory response; 6) the ability of Treg to control the xeno-reactive response; 7) the impact of lymphocyte depletion/concomitant immunosuppressive therapy on Treg function. In light of the strong similarity between human and NHP Treg, NHP transplant models are well-positioned to resolve these issues.

FIGURE 1.

(A), Issues that govern the successful application of Treg therapy in transplantation. (B–D), Highly-suppressive Treg can be expanded/induced from cynomolgus monkey blood. (B), CD4+CD127loCD25+ (nTreg) were flow-sorted from PBMC. They were stimulated in vitro with anti-CD3/CD28-coated beads, in the presence of human IL-2 (500U/ml), with or without TGFβ1 (5ng/ml). In parallel, CD4+CD127hiCD25− T cells were sorted and induced to convert into regulatory cells (iTreg) by stimulation with anti-CD3/CD28-coated beads in the presence of IL-2 and TGFβ1, with or without retinoic acid (RA; 5ng/ml). The fold-expansion obtained under each condition at multiple time points is indicated. (C), Preservation of Foxp3 expression in expanded nTreg was tested by intracellular staining after 16 days of culture. (D), The suppressive capacity of expanded nTreg was tested in MLR. PBMC were obtained from the same source as nTreg and stimulated in vitro with irradiated allogeneic PBMC (1:2 responder to stimulator ratio). Titrated numbers of nTreg or nTreg (TGFβ1) were added to the cultures at the indicated Treg to responder ratios. Responder cell proliferation was quantified by thymidine incorporation on day 4. nTreg expanded with IL-2 alone did not inhibit proliferation significantly (data not shown). (E), as in D, T cells induced to convert into iTreg were tested for their suppressive capacity in MLR.

p<0.02; **, p<0.05 for all comparisons indicated.

Purification, induction, and expansion of NHP Treg

Although rare cells, new methods have emerged for the purification and expansion of polyclonal and Ag-specific Treg (13). Phenotypic and functional characterization of NHP nTreg (CD4+CD25+) in blood or lymphoid tissues has been reported for cynomolgus (14, 15) and rhesus macaques (10, 16, 17) and baboons (18). Their ex vivo expansion following immunomagnetic bead or/and flow sorting has been documented in response to either polyclonal stimuli (11, 16), peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) (18) or allogeneic DC (14) (Table 1). As in humans, more precise characterization of NHP Treg is needed. Recently, human Treg have been better distinguished from conventional T cells by their lack of cell surface CD127 (IL-7Rα); CD127 expression correlates inversely with Foxp3 and suppressive function (13). In cynomolgus macaques, circulating CD4+CD25+CD127− cells that express Foxp3 and exhibit suppressive activity have been isolated and expanded using ‘semi-mature’ allogeneic DC and IL-2 (14), although the alloAg specificity of the Treg was not ascertained. In rhesus macaques, circulating CD4+CD25+CD127lo/− T cells have been expanded ex vivo using anti-CD3/CD28 mAbs and IL-2, and shown to potently inhibit effector T cell proliferation in a non-specific manner (11). Our recent findings (19) are the first to show that a highly-suppressive population of alloAg-specific rhesus Treg can be generated in vitro from circulating CD4+CD127−/lo T cells (6±1% of bulk CD4+ T cells) in response to immature allogeneic DC and stimulation with IL-2 and IL-15.

TABLE 1.

Reports of NHP Treg isolation, expansion and ability to inhibit allo- or xenoreactive T cell proliferation

| Species | Treg selection (purity) | Cell yield | Expansion method | Expansion rate | Suppressive activity | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rhesus (macaque) | T cells from spleen | 200×106 cells per recipient (splenectomized) | Donor splenocytes + anti-CD80/CD86; 13 d | 2–4-fold | In vivo infusion 13d post allo kidney transplant; donor-specific suppression of rejection | (12) |

| Rhesus | MACS (90%) or FACS (98%) CD4+ CD25+ | Not mentioned | Anti-CD3/CD28 beads + IL-2; 4wk | 300–2000-fold | Up to 1:8a ratio, inhibition of autologous PBMC proliferation | (16) |

| Rhesus | Anti-CD8 and anti-CD20 Dynabeads, or CD4+ MACS, followed by anti-CD25 MACS (82%) | 10% of CD3+CD4+ T cells | Fresh cells used; no expansion | n/a | Proliferation of Teff to anti-CD3 or irradiated PBMC decreased at 1:1a ratio, but variation between animals | (10) |

| Rhesus | FACS CD4+CD25hi or CD4+CD25+CD127− | 10×104 cells/ml blood | Anti-CD3/CD28 beads + IL-2; 4 wk | Up to 450-fold | CFSE-MLR, up to 1:100a ratio; suppression of allo response by responder-specific or third-party Treg | (11) |

| Rhesus | MACS CD4+CD127−/lo | 7% of CD4+/1.3% of total PBMC; 3.7 × 104 cells/ml blood | Immature Mo-DC + IL-2 + IL-15; 14d, or 10d followed by 2d without DC | No expansion | Suppression up to 1:40a ratio; donor-specific | (19) |

| Cynomolgus (macaque) | FACS CD4+ CD25+CD127− (>98%) | 0.4% of PBMC | Allo DC (BMDC/Mo-DC) + IL-2; 7days | 12–25-fold | CFSE-MLR, PBMC+ anti-CD3/CD28+ Treg: 30% inhibition at 1:3a ratio. Treg suppressive capacity stimulated by BMDC > Mo-DC | (14) |

| Cynomolgus (MS model) | MACS CD4+ CD25+ (>90%) | 6.4% of T cells | Fresh cells used; no expansion | n/a | Proliferation to anti-CD3/CD28 or CD3/CD46 stimulation is impaired during active MS | (15) |

| Baboon | MACS→FACS sorting (>95%) CD4+CD25hi | 1.7% spleen, 3.1% LN, 1.9% blood T cells; 10×104 cells/ml blood | Pig PBMC + IL-2; 3–4 wk + 7–10d without PBMC | ≤ 2000-fold, depending on IL-2 concentration | 1:1a, strong xenogeneic suppression, donor-specific: 4–10× less efficient to third-party | (18) |

Treg:effector cell ratio;

n/a, not applicable

BMDC, bone-marrow derived dendritic cells; d, day; FACS, fluorescence-activated cell sorting; LN, lymph node; MACS, magnetic-activated cell sorting; Mo-DC, monocyte-derived dendritic cells; MS, multiple sclerosis; wk: week

Since the frequency of nTreg is comparatively low, de novo generation of Treg from conventional T cells is an appealing strategy to obtain large numbers of cells. In vitro activation of human CD4+CD25− T cells via T cell receptor stimulation in the presence of transforming growth factor (TGF)β upregulates Foxp3, conferring suppressive capacity (20). As with genetic manipulation of conventional T cells to express Foxp3, the reproducibility of Treg induction (iTreg) using this approach has been questioned, as has the stability of their suppressive capacity (21). Despite these concerns, considerable promise has now been shown by the ability of all-trans-retinoic acid (RA) to synergize with TGFβ during T cell stimulation and induce highly suppressive murine or human Foxp3+ T cells (22, 23). These iTreg suppress immune-mediated disorders in mice (22), and potentially represent a valid alternative to expanded nTreg. However, clinical testing is not foreseeable due to safety concerns, and NHP models represent the best tool to establish the feasibility of this approach.

Function of NHP nTreg and iTreg

We have characterized and sorted nTreg from cynomolgus blood and also ascertained whether iTreg can be generated from conventional T cells. We tested in vitro conditions for expansion of nTreg and iTreg, and at the same time, determined their suppressive capacity. Flow-sorted CD4+CD25+CD127lo T cells were stimulated with anti-CD3/CD28-coated beads and IL-2. Additionally, TGF-β was tested for its ability to preserve the expression of Foxp3 and nTreg suppressive ability. As shown in Fig 1B, both conditions caused significant proliferation of the cells, with up to 700-fold expansion over a 15-day period. In our amplification system, when nTreg were stimulated with IL-2 only, high Foxp3 expression was lost (Fig 1C). Addition of TGFβ preserved the level of this transcription factor necessary for Treg suppressive activity. Expanded nTreg were tested for their ability to suppress proliferation of autologous responder T cells stimulated by allogeneic PBMC. As expected from the absence of Foxp3 expression, nTreg expanded without TGFβ did not exhibit significant suppressive capacity. By contrast, nTreg expanded with TGFβ were highly suppressive (Fig 1D).

Cynomolgus CD4+CD25−CD127hi T cells were also flow-sorted and stimulated in vitro with anti-CD3/CD28-coated beads in the presence of IL-2 and TGFβ1, with or without RA. Both conditions induced Foxp3 expression and favored significant expansion of the stimulated population (Fig 1B). Interestingly, as reported by Wang et al (23) for human T cells, only cynomolgus T cells stimulated with TGFβ and RA demonstrated profound inhibition of autologous alloreactive PBMC (Fig 1E). These data indicate the feasibility of testing the therapeutic potential of NHP iTreg and comparing their suppressive activity to that of expanded nTreg.

Several NHP studies have shown strong in vitro suppressive effects with Treg:responder cell ratios from 1:1 to 1:100, depending on type of expansion. Thus, Anderson et al (11) not only demonstrated impressive expansion of rhesus Treg, but also enhanced suppressive activity of polyclonally-expanded Treg with ratios up to 1:100. Studies in rhesus or cynomolgus macaques using alloAg-specific stimulation indicate however, that cell numbers cannot be expanded significantly (from no increase, up to 25-fold) (14, 19). On the other hand, pig PBMC and IL-2 were used to expand baboon Treg up to 2000-fold after 4 weeks of culture (18). These Treg suppressed effector T cell responses even at 1:256 ratio. Most likely, large numbers of Treg will be required to achieve the desired suppressive effect in vivo. An alternative solution could be incorporation of a T-cell depleting strategy (e.g. alemtuzumab [humanized anti-CD52; (24)] or anti-thymocyte globulin [ATG]) in NHP prior to Treg infusion, as fewer Treg would be needed for a favorable Treg:T cell ratio. Under these circumstances, delayed infusion of Treg would be indicated in order to avoid Treg depletion by the Ab (the terminal half-life of alemtuzumab in humans is 15–21 days [(25, 26)]). In our experience in cynomolgus monkeys, initial recovery of lymphocytes was evident 7 days after infusion of alemtuzumab (27), suggesting that Treg infused at this or a later time-point would remain intact.

Migratory properties of NHP Treg

Recently, Treg migratory ability has gained increased attention as a correlate of their in vivo suppressive function (28). While regulatory T cell markers are expressed both in accepted and rejected NHP renal allografts (29), recruitment of CD4+ Treg expressing TGFβ to the graft interstitium has been implicated in metastable renal transplant tolerance in rhesus monkeys (30). Multiple studies, including those in transplant models, have indicated that expression of specific chemokine receptors is essential for Treg activity in vivo (31, 32). There is also evidence that maximal Treg protective activity occurs when the cells migrate to both the transplant site and draining lymphoid tissue. Based on this paradigm, optimization of a procedure for rendering highly-suppressive NHP Treg should include testing for expression of a pattern of chemokine receptors (CCR2, CCR4, CCR5, CCR7) compatible with their migration to both the graft and lymphoid tissues. Recently, associations between Treg numbers and the expression of ligands for CXCR3, CCR4 and CCR7 in lymphoid tissue of simian immunodeficiency virus-infected cynomolgus monkeys have been reported (33).

Control of memory T cells

Donor-reactive memory T cells (Tmem) resistant to immunosuppressive agents undermine strategies for tolerance induction. Moreover, recent studies have shown that lymphoablative strategies (e.g. T cell depletion) may lead to preferential expansion and accumulation of Tmem, that derive from homeostatic proliferation of naïve T cells (34). In mice, CD4+ and CD8+ allospecific Tmem are more resistant to Treg-mediated suppression than naïve T cells (35). However, these Treg still suppress Tmem proliferation when present in equivalent number or at 1:3 ratio (Treg:Tmem). Human nTreg can suppress both naïve and memory T cell proliferation (36). While these reports suggest the potential of Treg to control rejection in sensitized patients, they also indicate the likely need for complementary treatments to control Tmem without affecting Treg activity. Thus it is noteworthy that proliferation of sirolimus-resistant rhesus monkey Tmem is inhibited by combined use of bortezomib (a proteasomal inhibitor that blocks nuclear factor κβ nuclear translocation) and sirolimus, a regimen that preserves pre-existing Treg survival (37).

Xenotransplantation

Although most NHP Treg studies have concerned the allogeneic response, a recent report by Porter et al (38) focused on baboon Treg in a xenogeneic (pig to baboon) setting. Treg were expanded in a donor-specific manner using irradiated pig PBMC. The expanded Treg not only were strongly suppressive at a ratio of 1:1, but donor-specific suppression was achieved. Further development of NHP Treg in the context of xenotransplantation, which offers the consistent advantage of donor identification before transplantation, could justify preclinical studies in this field [reviewed in (39)].

Transitioning to the clinic: the importance of NHP research

Safe and reliable protocols for the selection/induction and expansion of Treg that could be tested clinically are at a very early stage of development. A recent report (40) describes the first two cases of (donor-derived) CD4+CD25+CD127− Treg therapy in humans with acute or chronic graft-versus-host disease following hematopoietic cell transplantation. The findings indicate that the required Treg number may depend on clinical symptoms and underlying disease, as well as CD4+ T cell numbers, rather than on host body weight. NHP models have the inherent advantage of closely resembling the human condition and allow for preclinical testing, although such studies provoke ethical considerations, demand relevant experience, are expensive and time-consuming. They also require specialized facilities and resources that may only be available in large academic centers. Whether pre-clinical studies of Treg in NHP are essential before proceeding to a clinical trial is certainly debatable. Of importance is whether the therapeutic agents to be employed are effective in NHP, which is not always the case. However, if they are known to be effective, studies in NHP do provide a greater indication of both efficacy and safety than can be achieved from investigations in rodents. A clear example is the possible suppression of the immune response to infectious agents that could be induced by Treg infusion. Most would agree that experience of potential detrimental effects in a NHP model is much preferred, as it provides a greater assurance that the approach will be safe and efficacious when applied clinically. An innovative and more cost-effective approach to assess NHP Treg in vivo (and particularly relevant to rapid testing of primate-specific reagents) could be the use of ‘primatized’ mice, similar to ‘humanized’ mice (41), engrafted with NHP lymphohematopoietic stem cells giving rise to a complete repertoire of NHP immune cells. Such a model could be beneficial for initial testing of NHP Treg, without the need for, and the aforementioned limitations of, the large animal model. Taken together, and with due consideration to questions regarding efficacy and safety, NHP Treg hold considerable potential for preclinical testing of tolerance-promoting strategies.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant U01 AI 51698. Eefje M. Dons is the recipient of fellowships from the Ter Meulen Fund of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences and the Stichting Professor Michael van Vloten Fund, The Netherlands. Giorgio Raimondi is in receipt of an American Heart Association Beginning Grant-in-Aid, an American Diabetes Association Junior Faculty Grant and the Thomas E. Starzl Transplantation Institute Joseph A. Patrick Fellowship.

Abbreviations

- Ag

antigen

- DC

dendritic cells

- NHP

non-human primate

- PBMC

peripheral blood mononuclear cells

- RA

retinoic acid

- Teff

T effector cells

- TGFβ

transforming growth factor β

- Tmem

memory T cells

- Treg

regulatory T cells

Footnotes

Authors Contributions: EMD, GR, DKCC and AWT each participated in the writing of the mini-review

References

- 1.Sakaguchi S, Yamaguchi T, Nomura T, Ono M. Regulatory T cells and immune tolerance. Cell. 2008;133 (5):775. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wood KJ, Sakaguchi S. Regulatory T cells in transplantation tolerance. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3 (3):199. doi: 10.1038/nri1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roncarolo MG, Battaglia M. Regulatory T-cell immunotherapy for tolerance to self antigens and alloantigens in humans. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7 (8):585. doi: 10.1038/nri2138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bluestone JA. Regulatory T-cell therapy: is it ready for the clinic? Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5 (4):343. doi: 10.1038/nri1574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bluestone JA, Thomson AW, Shevach EM, Weiner HL. What does the future hold for cell-based tolerogenic therapy? Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7 (8):650. doi: 10.1038/nri2137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zheng Y, Rudensky AY. Foxp3 in control of the regulatory T cell lineage. Nat Immunol. 2007;8 (5):457. doi: 10.1038/ni1455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Raimondi G, Turner MS, Thomson AW, Morel PA. Naturally-occurring regulatory T cells: recent insights in health and disease. Crit Rev Immunol. 2007;27:61. doi: 10.1615/critrevimmunol.v27.i1.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shevach EM. Mechanisms of foxp3+ T regulatory cell-mediated suppression. Immunity. 2009;30 (5):636. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sachs DH. Tolerance: of mice and men. J Clin Invest. 2003;111 (12):1819. doi: 10.1172/JCI18926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haanstra KG, van der Maas MJ, t Hart BA, Jonker M. Characterization of naturally occurring CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells in rhesus monkeys. Transplantation. 2008;85 (8):1185. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e31816b15b9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anderson A, Martens CL, Hendrix R, et al. Expanded nonhuman primate Tregs exhibit a unique gene expression signature and potently downregulate alloimmune responses. Am J Transplant. 2008;8 (11):2252. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2008.02376.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bashuda H, Kimikawa M, Seino K, et al. Renal allograft rejection is prevented by adoptive transfer of anergic T cells in nonhuman primates. J Clin Invest. 2005;115 (7):1896. doi: 10.1172/JCI23743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Riley JL, June CH, Blazar BR. Human T regulatory cell therapy: take a billion or so and call me in the morning. Immunity. 2009;30 (5):656. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moreau A, Chiffoleau E, Beriou G, et al. Superiority of bone marrow-derived dendritic cells over monocyte-derived ones for the expansion of regulatory T cells in the macaque. Transplantation. 2008;85 (9):1351. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e31816f22d6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ma A, Xiong Z, Hu Y, et al. Dysfunction of IL-10-producing type 1 regulatory T cells and CD4(+)CD25(+) regulatory T cells in a mimic model of human multiple sclerosis in Cynomolgus monkeys. Int Immunopharmacol. 2009;9 (5):599. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2009.01.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gansuvd B, Asiedu CK, Goodwin J, et al. Expansion of CD4+CD25+ suppressive regulatory T cells from rhesus macaque peripheral blood by FN18/antihuman CD28-coated Dynal beads. Hum Immunol. 2007;68 (6):478. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2007.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hartigan-O’Connor DJ, Abel K, McCune JM. Suppression of SIV-specific CD4+ T cells by infant but not adult macaque regulatory T cells: implications for SIV disease progression. J Exp Med. 2007;204 (11):2679. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Porter CM, Horvath-Arcidiacono JA, Singh AK, Horvath KA, Bloom ET, Mohiuddin MM. Characterization and expansion of baboon CD4+CD25+ Treg cells for potential use in a non-human primate xenotransplantation model. Xenotransplantation. 2007;14 (4):298. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3089.2007.00416.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zahorchak AF, Raimondi G, Thomson AW. Rhesus monkey immature monocyte-derived dendritic cells generate alloantigen-specific regulatory T cells from circulating CD4+CD127−/lo T cells. Transplantation. 2009;88 (9):1057. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3181ba6b1f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Walker MR, Kasprowicz DJ, Gersuk VH, et al. Induction of FoxP3 and acquisition of T regulatory activity by stimulated human CD4+CD25− T cells. J Clin Invest. 2003;112 (9):1437. doi: 10.1172/JCI19441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tran DQ, Ramsey H, Shevach EM. Induction of FOXP3 expression in naive human CD4+FOXP3 T cells by T-cell receptor stimulation is transforming growth factor-beta dependent but does not confer a regulatory phenotype. Blood. 2007;110 (8):2983. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-06-094656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mucida D, Park Y, Kim G, et al. Reciprocal TH17 and regulatory T cell differentiation mediated by retinoic acid. Science. 2007;317 (5835):256. doi: 10.1126/science.1145697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang J, Huizinga TW, Toes RE. De novo generation and enhanced suppression of human CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells by retinoic acid. J Immunol. 2009;183 (6):4119. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van der Windt DJ, Setanka C, Macedo C, et al. Investigation of lymphocyte depletion and repopulation using alemtuzumab (CAMPATH-1H) in cynomolgus monkeys. Am J Transplant. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2010.03050.x. In Press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rebello P, Cwynarski K, Varughese M, Eades A, Apperley JF, Hale G. Pharmacokinetics of CAMPATH-1H in BMT patients. Cytotherapy. 2001;3 (4):261. doi: 10.1080/146532401317070899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Morris EC, Rebello P, Thomson KJ, et al. Pharmacokinetics of alemtuzumab used for in vivo and in vitro T-cell depletion in allogeneic transplantations: relevance for early adoptive immunotherapy and infectious complications. Blood. 2003;102 (1):404. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-09-2687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van der Windt DJ, Smetanka C, Macedo C, et al. Investigation of lymphocyte depletion and repopulation using alemtuzumab (Campath-1H) in cynomolgus monkeys. Am J Transplant. 2010;10 (4):773. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2010.03050.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen D, Bromberg JS. T regulatory cells and migration. Am J Transplant. 2006;6 (7):1518. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2006.01372.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Haanstra KG, Wubben JA, Korevaar SS, Kondova I, Baan CC, Jonker M. Expression patterns of regulatory T-cell markers in accepted and rejected nonhuman primate kidney allografts. Am J Transplant. 2007;7 (10):2236. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2007.01917.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Torrealba JR, Katayama M, Fechner JH, Jr, et al. Metastable tolerance to rhesus monkey renal transplants is correlated with allograft TGF-beta 1+CD4+ T regulatory cell infiltrates. J Immunol. 2004;172 (9):5753. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.9.5753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Izcue A, Coombes JL, Powrie F. Regulatory lymphocytes and intestinal inflammation. Annu Rev Immunol. 2009;27:313. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang N, Schroppel B, Lal G, et al. Regulatory T cells sequentially migrate from inflamed tissues to draining lymph nodes to suppress the alloimmune response. Immunity. 2009;30 (3):458. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.12.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Qin S, Sui Y, Soloff AC, et al. Chemokine and cytokine mediated loss of regulatory T cells in lymph nodes during pathogenic simian immunodeficiency virus infection. J Immunol. 2008;180 (8):5530. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.8.5530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sener A, Tang AL, Farber DL. Memory T-cell predominance following T-cell depletional therapy derives from homeostatic expansion of naive T cells. Am J Transplant. 2009;9 (11):2615. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2009.02820.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yang J, Brook MO, Carvalho-Gaspar M, et al. Allograft rejection mediated by memory T cells is resistant to regulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104 (50):19954. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704397104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Levings MK, Sangregorio R, Roncarolo MG. Human CD25+CD4+ T regulatory cells suppress naive and memory T cell proliferation and can be expanded in vitro without loss of function. J Exp Med. 2001;193 (11):1295. doi: 10.1084/jem.193.11.1295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kim JS, Lee JI, Shin JY, et al. Bortezomib can suppress activation of rapamycin-resistant memory T cells without affecting regulatory T-cell viability in non-human primates. Transplantation. 2009;88 (12):1349. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3181bd7b3a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Porter CM, Bloom ET. Human CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells suppress anti-porcine xenogeneic responses. Am J Transplant. 2005;5 (8):2052. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2005.00972.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Muller YD, Golshayan D, Ehirchiou D, Wekerle T, Seebach JD, Buhler LH. T regulatory cells in xenotransplantation. Xenotransplantation. 2009;16 (3):121. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3089.2009.00531.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Trzonkowski P, Bieniaszewska M, Juscinska J, et al. First-in-man clinical results of the treatment of patients with graft versus host disease with human ex vivo expanded CD4+CD25+CD127− T regulatory cells. Clin Immunol. 2009;133 (1):22. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2009.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shultz LD, Ishikawa F, Greiner DL. Humanized mice in translational biomedical research. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7 (2):118. doi: 10.1038/nri2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]