Abstract

The aim of the present study was to evaluate the toxicity and the activity of a new lipid complex formulation of amphotericin B (AMB) (LC-AMB; dimyristoyl phosphatidylcholine, dimyristoyl phosphatidylglycerol, and AMB) that can be produced by a simple process. Like other lipid formulations, this new complex reduced both the hemolytic activity of AMB (the concentration causing 50% hemolysis of human erythrocytes, >100 μg/ml) and its toxicity toward murine peritoneal macrophages (50% inhibitory concentration, >100 μg/ml at 24 h). The in vivo toxicity of the new formulation (50% lethal dose, >200 mg/kg of body weight for CD1 mice) was similar to those of other commercial lipid formulations of AMB. The complex was the most effective formulation against the DD8 strain of Leishmania donovani. It was unable to reverse the resistance of an AMB-resistant L. donovani strain. In vivo LC-AMB was less efficient than AmBisome against L. donovani.

There is a need for a new treatment for patients with visceral leishmaniasis (VL), particularly those with AIDS, since there is a high incidence of relapse after treatment with pentavalent antimonial drugs (11, 19, 25, 32). Despite the recent success with miltefosine as an antileishmanial drug (17, 36), its use is limited because of the risk of the rapid development of resistance if it is used alone (7). The antifungal drug amphotericin B (AMB), a polyene antibiotic, is commonly used to treat leishmaniasis, but its application is limited because of its acute toxicity, which leads to a low therapeutic index when it is used as the traditional formulation, Fungizone (i.e., micelles mixed with the detergent deoxycholate) (18). In order to reduce this dose-limiting toxicity, different commercial lipid-based formulations have been developed and used in the clinical management of VL: AmBisome (4, 10), Abelcet (38, 39), and Amphotec (12). These have also been used as alternative treatments for mucocutaneous leishmaniasis (35, 46). In some developed countries, AmBisome is now indicated as the first-line therapy against VL. However, the high prices of these formulations restrict their use in the regions most affected by these tropical diseases (24, 15).

Recently, several less expensive AMB formulations have been tested. Such formulations include the AMB derivatives prepared and described by Al-Abdely et al. (1) and Golenser et al. (14), which are water soluble and also less toxic. Heat treatment of Fungizone is an inexpensive technique for reduction of its toxicity (31), as is extemporaneous mixing of Fungizone with Intralipid (20, 40). Another particulate formulation with anionic lipids is stable and has good in vitro and in vivo efficacies (26). However, AmBisome remains the most effective formulation for the treatment of VL (46), and none of these formulations has yet been proved to be more active than the commercial ones.

The present study was designed to evaluate the antileishmanial activity of a new lipid formulation of AMB in comparison with those of other commercially available lipid-AMB formulations. This formulation has the same lipid composition as Abelcet but differs in its size and form because of a different, simple preparation process (37). Its toxicity was assessed against two different cell types and in vivo by administration of a single dose to CD1 mice. The efficacies of the different formulations against both wild-type and AMB-resistant strains of Leishmania donovani growing in peritoneal macrophages in culture and against another strain of the same parasite in mice were determined.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals.

AMB was purchased from Sigma (Saint-Quentin-Fallavier, France), and Fungizone was purchased from Squibb (Neuilly, France). The different lipid formulations are described in Table 1. AmBisome and Ampholiposomes were kind gifts from Nexstar Pharmaceuticals (now Gilead Sciences, Foster City, Calif.) and the Pharmacie Centrale des Hôpitaux de Paris, respectively; Amphotec was obtained from Liposome Technology Inc. (Menlo Park, Calif.); and Abelcet was obtained from the Liposome Company Ltd. (London, United Kingdom). Dimyristoyl phosphatidylcholine (DMPC) and dimyristoyl phosphatidylglycerol (DMPG) were purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids Inc. (Alabaster, Ala.). Solvents and other reagents were obtained from Carlo Erba Reagenti (Val de Reuil, France). To prepare the free drug, AMB was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide at a concentration of 10 mg/ml just before the experiment and was then diluted in culture medium. Polymyxin B sulfate was obtained from Fluka (Mulhouse, France).

TABLE 1.

AMB lipid formulations

| AMB formulation | Composition (molar ratio)a | AMB/lipid ratio (mol%) | Charge | Shape | Size (μm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liposomes | |||||

| AmBisome | HSPC, CHOL, DSPG, AMB (2:1:0.8:0.4) | 10 | Negative | Small unilamellar vesicles | 0.08 |

| Ampholiposomes | EPC, CHOL, SA, AMB (4:3:1:0.4) | 5 | Positive | Oligolamellar vesicles | 0.2-0.3 |

| Complexes | |||||

| Amphotec | CS, AMB (1:1) | 50 | Negative | Colloidal dispersion (disks) | 0.12 |

| Abelcet | DMPC, DMPG, AMB (7:3:10) | 50 | Negative | Lipid complexes (sheets) | 1-10 |

| LC-AMB | DMPC, DMPG, AMB (7:3:5) | 33 | Negative | Lipid complexes | 0.25 |

Abbreviations: HSPC, hydrogenated soy phosphatidylcholine; CHOL, cholesterol; DSPG, distearoylphosphatidylglycerol; EPC, egg yolk phosphatidylcholine; SA, stearylamine; CS, cholesteryl sulfate.

Tissue culture.

Tissue culture products were obtained from Gibco (Eragny, France), tissue culture flasks and 24-well plates were obtained from Dominique Dutscher (Brumath, France), and Nunc 96-well plates were obtained from ATGC (Noisy-le-Grand, France). Triton X-100, sodium dodecyl sulfate, dimethyl formamide, and dimethylthiazol diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) were all supplied by Sigma. All reagents and media for tissue culture experiments were tested for lipopolysaccharide (LPS) content by a colorimetric Limulus amebocyte lysateassay (detection limit, 11 pg/ml; Whittaker Bioproducts, Walkersville, Md.).

Preparation of a lipid complex of AMB (LC-AMB).

A colloidal dispersion was prepared by using the solvent displacement process described by Stainmesse (37). AMB (3.5 mg) was dissolved in methanol (15 ml) with DMPC (3.5 mg) and DMPG (1.5 mg), and this organic phase was added to the aqueous phase (15 ml of pure water). The volume was reduced to 5 ml by low-pressure evaporation. The mean particle diameter, measured by laser light scattering with a typical preparation (Nanosizer N4; Coultronics, Margency, France), was 250 ± 50 nm (mean ± standard deviation for three runs), with a polydispersity index of 0.12.

The properties of the other lipid formulations are described in Table 1.

Electron microscopy. (i) Freeze fracture.

A drop of the suspension containing 30% glycerol as a cryoprotectant was deposited on a thin copper planchette and was rapidly frozen in liquid propane. Fracturing and shadowing with Pt-C were performed in a Balzers BAF 310 freeze-etch unit. The replicas were examined with a Philips 410 electron microscope.

(ii) Air drying.

The sample was deposited on a freshly cleaved mica plate, dried at room temperature, and shadowed in the Balzers units. The shadowing with Pt-C was performed in a Balzers BAF 310 freeze-etch unit. The replicas were examined with a Philips 410 electron microscope.

Mouse peritoneal macrophages.

Thioglycolate-elicited mouse peritoneal macrophages were harvested from female CD1 mice (weight, 20 to 25 g; Charles River Ltd., St.-Aubin-Les-Elbeuf, France), as described by Larabi et al. (21).

In vitro toxicity.

Toxicity toward mouse peritoneal macrophages was assessed with cells plated in 96-well plates at 105 cells/well. After adherence, the medium was removed and replaced by one of the media containing the different formulations of AMB. The plates were incubated for 4, 24, 48, and 72 h at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator. Control cells were incubated with culture medium alone. Cell viability was determined by a colorimetric assay with the tetrazolium salt MTT. In parallel experiments, after the cells were washed twice in warm phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), followed by lysis in 0.1% (wt/vol) Triton X-100, the protein contents of the macrophage monolayers were determined after the same incubation times mentioned above by a detergent-compatible assay (Lowry method; Bio-Rad, Ivry-sur-Seine, France) with bovine serum albumin as a standard. Finally, to ensure that the toxic effects of the AMB formulations were not due to contamination with traces of bacterial LPS, another set of experiments was performed in which the formulations were preincubated with polymyxin B (2 μM) for 15 min at 37°C before addition to the cells.

Measurement of antibiotic-induced Hb release from erythrocytes.

The AMB formulations were dispersed in PBS at different concentrations (0.1 to 100 μg/ml) and incubated for 5 min at 37°C. Freshly isolated human erythrocytes were then added to a final hematocrit of 2% (approximately 2 × 108 cells per ml) and incubated at the same temperature for 30 min. After centrifugation (1,500 × g for 5 min at 4°C) the supernatant was removed and the erythrocyte pellet was lysed with sterile water. The hemoglobin (Hb) remaining in the pellet was estimated from its absorption at 560 nm, which was recorded with a spectrophotometer. Control erythrocytes (2 × 108 cells per ml) incubated with PBS alone in the same experiment were used to estimate the total Hb content after lysis. The percent hemolysis was calculated from the difference between the Hb remaining in the test samples and that remaining in the control erythrocytes. The results provided here are from one representative experiment of three experiments conducted, with each concentration determined in triplicate.

Acute toxicity in vivo.

A single bolus injection (200 μl) containing various doses of AMB in different formulations (Fungizone, Abelcet, LC-AMB) was given intravenously to groups of 10 male CD1 mice (weight, 25 to 30 g; Charles River). Mouse survival was monitored daily for 30 days, and the 50% lethal dose (LD50) was determined by the method of Litchfield and Wilcoxon (23).

Activity against L. donovani promastigotes in macrophages.

L. donovani (MHOM/IN/80/DD8), from the World Health Organization reference collection at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine (University of London, London, United Kingdom), was used to obtain the AMB-resistant line by drug pressure. This strain is referred to as L. donovani DD8 AMB-R (28) and was used for the in vitro experiments.

Mouse peritoneal macrophages were plated in Labtek eight-chamber slides at 5 × 104 cells per well in RPMI 1640 with 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum at 37°C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2 in air for 4 h. The macrophages were then incubated for 24 h at 37°C with infective promastigotes at a 1:20 cell/parasite ratio for the AMB-R strain and a 1:10 cell/parasite ratio for the wild type; approximately 80% of the cells were infected. After the cells were washed to eliminate extracellular parasites, the cells were incubated for 24 h in culture medium alone. The medium was then replaced with medium containing the drug for 4 days. After the medium was removed, the slides were fixed with methanol and stained with Giemsa, the number of amastigotes in 200 macrophages per chamber was counted, and the antileishmanial activity was expressed as described by Neal and Croft (29).

In vivo activity against L. donovani.

Female BALB/c mice (weight, 20 g; Tuck Ltd., Battlesbridge, United Kingdom) were infected by the intravenous route with 1.5 × 107 L. donovani (MHOM/ET/67/H43) amastigotes freshly isolated from hamster spleen. At 7 days postinfection, one mouse was killed to check for the patency of infection, and drug administration was commenced. The activities of sodium stibogluconate (Pentostam), LC-AMB, and Abelcet were compared in the first experiment; and the activities of sodium stibogluconate, LC-AMB, and AmBisome were compared in the second experiment. The AMB formulations were administered intravenously at different doses for 3 consecutive days, while sodium stibogluconate was given subcutaneously at 15 mg/kg of body weight for 5 consecutive days. All mice were killed on day 14 postinfection, liver impression smears were made, and the smears were fixed with 100% methanol and stained with Giemsa. The number of parasites per 500 liver cells was counted. Parasite numbers were calculated by taking into account the weight of the liver. The 50% effective dose (ED50) was also determined by sigmoidal regression analysis.

RESULTS

Structure of the formulation.

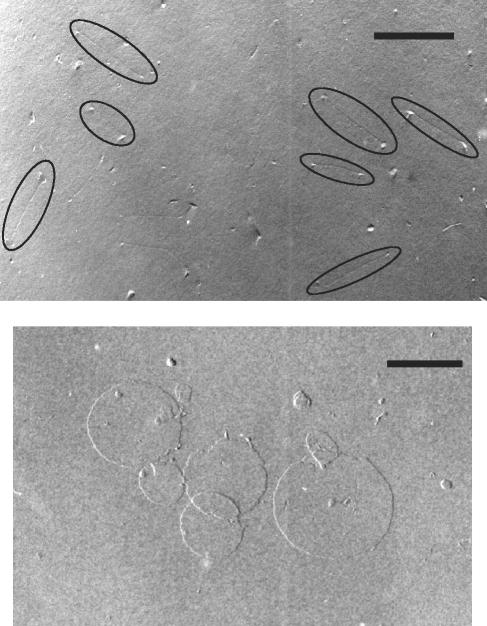

Electron microscopy of LC-AMB after freeze fracture showed a very thin (a few-nanometer-thick) dumbbell-like structure with a length of about 250 nm (Fig. 1A). In contrast, electron microscopy of the complex performed without freeze fracture and just with drying and shadowing showed a thin disk-like structure of about 250 nm in diameter. The thickness of the disk was evaluated from the angle of shadowing and the length of the shadow and was found to be about 29 Å (Fig. 1, bottom). The fact that freeze fracture occurred through the thickness of the disk and not along the long axis of the particles suggests that the lipids adopt an interdigitated rather than a bilayer structure; and the lack of fusion between two disks, shown in the center of the bottom panel of Fig. 1, despite the harsh experimental conditions, confirms a strong interaction between AMB and phospholipids. It was therefore interesting to assess the toxicity of AMB in this form.

FIG. 1.

Electron microscopy of LC-AMB. Samples were prepared with DMPC-DMPG-AMB (7:3:5) with freeze fracture (top panel) or without freeze fracture (bottom panel), as described in Materials and Methods. Bars, 200 nm.

In vitro toxicity. (i) Hemolysis.

AMB dispersed in water from a stock solution in dimethyl sulfoxide produced 50% hemolysis of human erythrocytes at a concentration of 3.5 μg/ml. Fungizone and AMB prepared by the same process used to prepare LC-AMB but without lipids were slightly less toxic (the concentration causing 50% hemolysis of human erythrocytes, 5 μg/ml). All the lipid formulations caused less than 50% hemolysis at the highest concentration tested (>100 μg/ml).

(ii) Toxicity of AMB formulations toward mouse peritoneal macrophages.

Toxicity was determined by the MTT conversion test (Table 2); the protein assay for determination of the number of macrophages remaining adherent in the plates yielded similar results (data not shown). AmBisome and the new formulation, LC-AMB, were the least toxic, with IC50s above 100 μg/ml after a 24-h exposure. The toxicities of all formulations increased with the time of exposure. At 48 h the IC50 of LC-AMB was 86 μg/ml. The IC50s were not reduced by treatment of the formulations with polymyxin B to complex any contaminating LPS; therefore, this toxicity can be ascribed to AMB.

TABLE 2.

In vitro and in vivo toxicities determined as described in Materials and Methodsa

| Formulation | IC50 (μg of AMB per ml) in vitro at:

|

LD50 (mg of AmB per kg) in vivo

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 h | 24 h | 48 h | Determined experimentally | Determined previously (reference) | |

| Fungizone | 57 | 4.5 | 2 | 3.5 | 2.5 (22) |

| AmBisome | >100 | >100 | 92 | >175 (22) | |

| Ampholiposomes | >100 | 46 | 21 | 22 (30) | |

| LC-AMB | >100 | >100 | 86 | >200 | |

| Abelcet | >100 | 84 | 73 | 40 | 50-70 (22) |

| Amphotec | >100 | 91 | 86 | >100 (16) | |

The in vitro toxicities (IC50s) of the different formulations of AMB were determined by the MTT test with murine peritoneal macrophages after various incubation periods. The in vivo toxicities (LD50s for acute toxicity) of these AMB formulations were assessed in male CD1 mice after a single intravenous bolus injection. Values are calculated from the number of mice surviving the injection. The maximum tolerated dose of LC-AmB was 100 mg/kg.

Acute toxicity in vivo.

As shown in Table 2, all the lipid formulations were clearly less toxic than Fungizone after a single injection. The acute toxicities observed for Fungizone and Abelcet were in accordance with the data reported in the literature (Table 2). LC-AMB was less toxic than Abelcet and Amphotec and showed toxicity similar to those for AmBisome given in the literature. The concentrations of LC-AMB necessary to determine the LD50 without increasing the injection volume were higher than those which could be obtained by the process described above. Further concentration of the LC-AMB had to be performed, leading to an increase in viscosity at concentrations above 10 mg of AMB per ml, corresponding to 80 mg/kg. Although all the mice given 200 mg of AMB as LC-AMB per kg survived the injection, three mice in this group died a few days later (between days 2 and 5). Among the mice in the group given 150 mg/kg, one mouse died on day 2 and another died on day 5. There were no deaths in the groups given 100 mg/kg or less. These results with 100, 150, and 200 mg/kg were obtained in two independent experiments.

In vitro activities against wild-type and AMB-resistant L. donovani DD8 promastigotes.

The activities of the different formulations against the intramacrophage L. donovani DD8 amastigotes and the AMB-resistant strain, previously selected by drug pressure (27), were determined. The new discoid complex, LC-AMB, was by far the most active formulation against the wild-type strain, followed by Abelcet, whereas the Amphotec complex and the Ampholiposomes were the least active (Table 3). The lipid formulations did not reverse the resistance of the AMB-resistant strain, but three of them (Ampholiposomes, Amphotec, and LC-AMB) were more effective than Fungizone against this strain.

TABLE 3.

In vitro evaluation of lipid formulations of AMB with macrophages infected with the L. donovani DD8 wild-type and AMB-R lines

| AMB formulation | IC50 (μg of AMB per ml)a

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Wild type | AMB-R | |

| AMBb | 0.045 ± 0.006 | 0.723 ± 0.081 |

| Fungizone | 0.041 ± 0.010 | 0.751 ± 0.006 |

| AmBisome | 0.042 ± 0.005 | 0.657 ± 0.078 |

| Ampholiposomes | 0.075 ± 0.022 | 0.204 ± 0.019 |

| Amphotec | 0.075 ± 0.025 | 0.209 ± 0.031 |

| LC-AMB | 0.008 ± 0.003 | 0.221 ± 0.031 |

| Abelcet | 0.032 ± 0.007 | 0.622 ± 0.034 |

IC50s were determined as described in Materials and Methods after 4 days of treatment. The values are means ± standard deviations.

Free drug.

Activity against L. donovani in vivo.

AmBisome was more active than LC-AMB in a mouse model of visceral leishmaniasis (Table 4). The ED50s were 0.19 and <0.20 mg/kg, respectively, and the ED90s were 0.51 and <0.20 mg/kg, respectively.

TABLE 4.

Activities of the novel AMB formulation against L. donovani H43 in BALB/c micea

| Formulation and dosing regimen (mg/kg)b | % Inhibition (mean ± SEM) | ED50 (ED90) (mg/kg) |

|---|---|---|

| LC-AmB | ||

| 0.125 | 33.23 ± 5.3 | |

| 0.25 | 59.45 ± 10.1 | 0.19 (0.51) |

| 0.5 | 96.68 ± 0.8 | |

| 1.0 | 99.37 ± 0.7 | |

| AmBisome | ||

| 0.2 | 98.5 ± 0.3 | |

| 1.0 | 99.95 ± 0.1 | <0.2 (<0.2) |

| 5.0 | 100 | |

| Sodium stibogluconatec | 31.72 ± 8.4 |

The number of amastigotes in the liver at the end of the treatment was determined as described in Materials and Methods.

The doses were given three times unless indicated otherwise.

Sodium stibogluconate was given at 15 mg/kg five times subcutaneously.

In a previous experiment, LC-AMB was found to be as effective as Abelcet at the same dose, but the ED50 could not be determined because of the small number of points (99 and 71% inhibition of liver parasite burdens after three injections of 1 mg/kg, respectively).

DISCUSSION

Leishmania parasites have developed strategies which allow them to survive and multiply within macrophages. After injection, colloidal drug delivery systems are concentrated in the organs of the mononuclear phagocyte system. Hence, the advantage of such formulations for the treatment of leishmaniasis is that these colloidal formulations are concentrated within phagocytic cells and increase the local drug concentrations in the infected tissues (2). It is also possible that the lipids themselves could have an effect on the parasite. In another study, DMPC-DMPG (7:3 molar ratio) prepared by the same process used to prepare LC-AMB, but without AMB, was not efficient against L. donovani H43. The proportion of infected macrophages was 82% for blank LC-AMB (2 μM of lipids), whereas it was 80% for the control (infected macrophages with the complete cell culture medium). Similar results were observed with Ampholiposomes (30) and AmBisome (9, 44).

In terms of in vitro toxicity, the new lipid complex, LC-AMB, reduced the hemolytic activity of AMB in way similar to those of the other lipid formulations, in comparison with the hemolytic activity of the free drug or Fungizone. However, the toxicity toward mouse peritoneal macrophages varied from one lipid formulation to another. The toxicity induced by AMB is now believed to involve several different mechanisms: cell membrane permeability due to complexes formed between the antibiotic and sterol (5) and lipid peroxidation induced by the auto-oxidation of antibiotic (3, 6). Similar mechanisms of toxicity against Leishmania have been shown (8, 33, 34).

One factor that could influence the toxicities of the different lipid formulations is the rate at which they release AMB (monomeric or aggregated [for a review, see reference 6]). It seems that the stabilities of the formulations in biological fluids play a role in determining toxicity, because Ampholiposomes, which have been shown to release drug into the medium, were more toxic than the more stable AmBisome. The interdigitated structure of LC-AMB, which allows strong interactions between AMB and the phospholipids, and its small size (250 nm), which reduces its level of uptake by phagocytosis, probably combine to give this formulation low levels of toxicity. The release of AMB from the formulations may be accelerated by the action of cellular lipases released by the cells. For example, Swenson et al. (42) have reported that the presence of fungal phospholipase may determine susceptibility to Abelcet.

A second factor which could determine the toxicities of these formulations is the rate at which they are taken up by macrophages. In previous work, we compared the association of different AMB formulations with mouse peritoneal macrophages (21). This was much greater for the commercial complexes Amphotec and Abelcet than for the liposomes (AmBisome, Ampholiposomes), with the association of LC-AMB intermediate between those of these two groups. Therefore, toxicity does not seem to be directly related to the total amount of AMB delivered to the cells.

These same formulations also had various efficacies (IC50s) against the DD8 strain of L. donovani growing within macrophages. The IC50s of the same formulation varied according to the line of Leishmania and the cells used (45). The type of formulation may determine the intracellular trafficking of AMB and hence its availability to the parasite. Therefore, it would be interesting to determine the subcellular distribution of free AMB delivered to macrophages by different formulations, particularly in infected cells.

None of the formulations tested were completely effective against the AMB-resistant strain of L. donovani DD8 and had IC50s similar to that of Fungizone for the wild-type strain. However, several of them, including LC-AMB, were more active than Fungizone against the AMB-resistant strain. The AMB resistance of this strain is the result of an altered membrane composition in the parasite, in which ergosterol is replaced by another sterol, thus removing the main target for AMB and causing increased membrane fluidity and fragility (27). It is possible that some formulations could improve the efficacy of AMB by facilitating its insertion into the modified parasite membrane. These results were not as spectacular as those obtained by Espuelas et al. (13), in which mixed micelles of AMB with the hydrophilic surfactant poloxamer 188 were able to completely reverse the resistance of the DD8 strain in vitro.

The lipid formulations all reduced the acute, in vivo toxicity of AMB in mice (Table 2). Again, the formulations were not equivalent. Although Abelcet and LC-AMB share the same lipid composition, there was a large difference in their toxicities. Although the distribution of the LC-AMB formulation was not determined, there is some indirect evidence that it also accumulates in the organs of the reticuloendothelial system. In toxicity studies in which multiple doses (20 mg/kg/day for 21 days) were administered to mice, there were significant increases in both liver and spleen weights and circulating transaminase levels (Fungizone at 0.5 mg/kg, Abelcet at 10 mg/kg, and LC-AMB at 20 mg/kg led to concentrations of transaminases [alanine aminotransaminase] in plasma of 404, 405, and 233 IU/liter, respectively). However, no changes in renal function were observed.

Many studies suggest that AmBisome is the most effective lipid formulation of AMB in clinical use for VL (15, 46). As expected, AmBisome was highly effective in our in vivo model, and LC-AMB showed slightly lower levels of activity. In preliminary experiments, LC-AMB was found to be more effective than Abelcet (99 and 71% inhibition of the liver parasite burden, respectively, after three injections of 1 mg/kg) and also had the advantage of much lower levels of toxicity. The longer circulation time of AmBisome implies a persistence in tissues and organs which helps to prevent the occurrence of relapses, thus increasing its activity against mucocutaneous leishmaniasis (28), and its low level of toxicity allows better tolerance of the treatment and the possibility that a single high dose can be administered to cure VL infections (41, 43).

In conclusion, the new lipid formulation of AMB described here shows a low level of toxicity and good in vivo activity in mice. The AMB/lipid ratio is much higher in LC-AMB (33 mol%) than in AmBisome (10 mol%), which reduces the need for expensive phospholipids in the formulation, which are needed for AmBisome. The preparation procedure contains only two steps: mixing of phases and organic solvent elimination. Furthermore, it shows satisfactory activity against an AMB-resistant strain of L. donovani. In the future, it would be of interest to determine the distribution of the parasite load and the AMB concentration in different organs (to predict relapse) and the efficacy of this new lipid formulation of AMB in a mucocutaneous leishmaniasis model.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by a grant from BQR98 of Paris XI University and a personal grant (“Louis Forest et Georges Canat”) from la Chancellerie des Universités de Paris, as well as Ph.D. awards from the Academie de Pharmacie and the School of Pharmacy of Paris XI to M.L. V.Y. received financial support from the UNDP/World Bank/WHO Special Programme for Research and Training in Tropical Diseases.

We thank Ghania Degobert (Laboratoire d'Automatique et de Genie des Procedes, Lyon, France) for enriching discussions about the scale up of this new preparation process and the technicians of the Faculty's Central Animal House for care of the mice. AmBisome and Ampholiposomes were kind gifts from Nexstar Pharmaceuticals (now Gilead Sciences) and the Pharmacie Centrale des Hôpitaux de Paris, respectively; Amphotec was obtained from Liposome Technology Inc., and Abelcet was obtained from the Liposome Company Ltd.

REFERENCES

- 1.Al-Abdely, H. M., J. R. Graybill, R. Bocanegra, L. Najvar, E. Montalbo, S. L. Regen, and P. C. Melby. 1998. Efficacies of KY62 against Leishmania amazonensis and Leishmania donovani in experimental murine cutaneous leishmaniasis and visceral leishmaniasis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:2542-2548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alving, C. R. 1983. Delivery of liposome-encapsulated drugs to macrophages. Pharmacotherapy 22:407-424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barwicz, J., I. Gruda, and P. Tancrede. 2000. A kinetic study of the oxidation effects of amphotericin B on human low-density lipoproteins. FEBS Lett. 465:83-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berman, J. D., R. Badaro, C. P. Thakur, K. M. Wasunna, K. Behbehani, R. Davidson, F. Kuzoe, L. Pang, K. Weerasuriya, and A. D. Bryceson. 1998. Efficacy and safety of liposomal amphotericin B (AmBisome) for visceral leishmaniasis in endemic developing countries. Bull. W. H. O. 76:25-32. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brajtburg, J., W. G. Powderly, G. S. Kobayashi, and G. Medoff. 1990. Amphotericin B: current understanding of mechanisms of action. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 34:183-188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brajtburg, J., and J. Bolard. 1996. Carrier effects on biological activity of amphotericin B. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 9:512-531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bryceson, A. 2001. A policy for leishmaniasis with respect to the prevention and control of drug resistance. Trop. Med. Int. Health 6:928-934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cohen, B. E., H. Ramos, M. Gamargo, and J. Urbina. 1986. The water and ionic permeability induced by polyene antibiotics across plasma membrane vesicles from Leishmania sp. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 860:57-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Croft, S. L., R. N. Davidson, and E. A. Thornton. 1991. Liposomal amphotericin B in the treatment of visceral leishmaniasis. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 28(Suppl. B):111-118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davidson, R. N., S. L. Croft, A. Scott, M. Maini, A. H. Moody, and A. D. Bryceson. 1991. Liposomal amphotericin B in drug-resistant visceral leishmaniasis. Lancet 337:1061-1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Desjeux, P. 1999. Global control and leishmania HIV co-infection. Clin. Dermatol. 17:317-325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dietze, R., E. P. Milan, J. D. Berman, M. Grogl, A. Falqueto, T. F. Feitosa, K. G. Luz, F. A. Suassuna, L. A. Marinho, and G. Ksionski. 1993. Treatment of Brazilian kala-azar with a short course of Amphocil (amphotericin B cholesterol dispersion). Clin. Infect. Dis. 17:981-986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Espuelas, S., P. Legrand, P. M. Loiseau, C. Bories, G. Barratt, and J. M. Irache. 2000. In vitro reversion of amphotericin B resistance in Leishmania donovani by poloxamer 188. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:2190-2192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Golenser, J., S. Frankenburg, T. Ehrenfreund, and A. J. Domb. 1999. Efficacious treatment of experimental leishmaniasis with amphotericin B-arabinogalactan water-soluble derivatives. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:2209-2214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guerin, P. J., P. Olliaro, S. Sundar, M. Boelaert, S. L. Croft, P. Desjeux, M. K. Wasunna, and A. D. Bryceson. 2002. Visceral leishmaniasis: current status of control, diagnosis, and treatment, and a proposed research and development agenda. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2:494-501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guo, L. S. S., and P. K. Working. 1993. Complexes of amphotericin B and cholesteryl sulfate. J. Liposome Res. 3:437-490. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Herwaldt, B. L. 1999. Miltefosine—the long-awaited therapy for visceral leishmaniasis? N. Engl. J. Med. 341:1840-1842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khoo, S. H., J. Bond, and D. W. Denning. 1994. Administering amphotericin B, a practical approach. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 33:203-213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Laguna, F., R. Lopez-Velez, F. Pulido, A. Salas, J. Torre-Cisneros, E. Torres, F. J. Medrano, J. Sanz, G. Pico, J. Gomez-Rodrigo, J. Pasquau, J. Alvar, et al. 1999. Treatment of visceral leishmaniasis in HIV-infected patients: a randomized trial comparing meglumine antimoniate with amphotericin B. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 13:1063-1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lamothe, J. 2001. Activity of amphotericin B in lipid emulsion in the initial treatment of canine leishmaniasis. J. Small Anim. Pract. 42:170-175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Larabi, M., P. Legrand, M. Appel, S. Gil, M. Lepoivre, J. P. Devissaguet, F. Puisieux, and G. Barratt. 2001. Reduction of NO synthase expression and tumor necrosis factor alpha production in macrophages by amphotericin B lipid carriers. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:553-562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lasic, D. D., and D. Papahadjopoulos. 1998. Medical applications of liposomes. Elsevier, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

- 23.Litchfield, J. T., and F. Wilcoxon. 1949. A simplified method of evaluating dose-effect experiments. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 96:99-113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lockwood, D. N. J. 1998. Commentary: some good news for treatment of visceral leishmaniasis in Bihar. BMJ 316:1205. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Loiseau, P. M., and C. Bories. 1999. Recent strategies for the chemotherapy of visceral leishmaniasis. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 12:559-564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Loiseau, P. M., L. Imbertie, C. Bories, D. Betbeder, and M. I. De Miguel. 2002. Design and antileishmanial activity of amphotericin B-loaded stable ionic amphiphile biovector formulations. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:1597-1601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mbongo, N., P. M. Loiseau, M. A. Billion, and M. Robert-Gero. 1998. Mechanism of amphotericin B resistance in Leishmania donovani promastigotes. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:352-357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mullen, A. B., K. C. Carter, and A. J. Baillie. 1997. Comparison of the efficacy of various formulations of amphotericin B against murine visceral leishmaniasis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 41:2089-2092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Neal, R. A., and S. L. Croft. 1984. An in vitro system for determining the activity of compounds against the intracellular amastigote form of Leishmania donovani. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 14:463-475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Paul, M., R. Durand, H. Fessi, D. Rivollet, R. Houin, A. Astier, and M. Deniau. 1997. Activity of a new liposomal formulation of amphotericin B against two strains of Leishmania infantum in a murine model. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 41:1731-1734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Petit, C., V. Yardley, F. Gaboriau, J. Bolard, and S. L. Croft. 1999. Activity of a heat-induced reformulation of amphotericin B deoxycholate (Fungizone) against Leishmania donovani. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:390-392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pintado, V., P. Martin-Rabadan, M. L. Rivera, S. Moreno, and E. Bouza. 2001. Visceral leishmaniasis in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected and non-HIV-infected patients. A comparative study. Medicine 80:54-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ramos, H., P. C. Saint, J. Bolard, and B. E. Cohen. 1994. Effect of ketoconazole on lethal action of amphotericin B on Leishmania mexicana promastigotes. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 38:1079-1084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ramos, H., E. Valdivieso, M. Gamargo, F. Dagger, and B. E. Cohen. 1996. Amphotericin B kills unicellular leishmaniasis by forming aqueous pores permeable to small cations and anions. J. Membr. Biol. 21:65-75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sampaio, R. N., and P. D. Marsden. 1997. Treatment of the mucosal form of leishmaniasis without response to glucantime, with liposomal amphotericin B. Rev. Soc. Bras. Med. Trop. 30:125-128. (In Portuguese.) [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Soto, J., J. Toledo, P. Gutierrez, R. S. Nicholls, J. Padilla, J. Engel, C. Fischer, A. Voss, and J. Berman. 2001. Treatment of American cutaneous leishmaniasis with miltefosine, an oral agent. Clin. Infect. Dis. 33:E57-E61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stainmesse, S., H. Fessi, J. P. Devissaguet, and F. Puisieux. June 1989. Procédé de préparation de systèmes colloidaux dispersibles de lipides amphiphiles sous forme de liposomes submicroniques. European patent 894018571.

- 38.Sundar, S., and H. W. Murray. 1996. Cure of antimony-unresponsive Indian visceral leishmaniasis with amphotericin B lipid complex. J. Infect. Dis. 173:762-765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sundar, S., A. K. Goyal, D. K. More, M. K. Singh, and H. W. Murray. 1998. Treatment of antimony-unresponsive Indian visceral leishmaniasis with ultra-short courses of amphotericin B-lipid complex. Ann. Trop. Med. Parasitol. 92:755-764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sundar, S., L. B. Gupta, V. Rastogi, G. Agrawal, and H. W. Murray. 2000. Short-course, cost-effective treatment with amphotericin B-fat emulsion cures visceral leishmaniasis. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 94:200-204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sundar, S., G. Agrawal, M. Rai, M. K. Makharia, and H. W. Murray. 2001. Treatment of Indian visceral leishmaniasis with single or daily infusions of low dose liposomal amphotericin B: randomised trial. BMJ 323:419-422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Swenson, C. E., W. R. Perkins, P. Roberts, I. Ahmad, R. Stevens, D. A. Stevens, and A. S. Janoff. 1998. In vitro and in vivo antifungal activity of amphotericin B lipid complex: are phospholipases important? Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:767-771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thakur, C. P. 2001. A single high dose treatment of kala-azar with AmBisome (amphotericin B lipid complex): a pilot study. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 17:67-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yardley, V., and S. L. Croft. 1997. Activity of liposomal amphotericin B against experimental cutaneous leishmaniasis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 41:752-756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yardley, V., and S. L. Croft. 2000. A comparison of the activities of three amphotericin B lipid formulations against experimental visceral and cutaneous leishmaniasis. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 13:243-248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zijlstra, E., M. Musa, A. G. Khalil, M. E. Hassan, and M. El-Hassan. 2003. Post-kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 3:87-98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]