Abstract

Mutants of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium resistant to fusidic acid (Fusr) have mutations in fusA, the gene encoding translation elongation factor G (EF-G). Most Fusr mutants have reduced fitness in vitro and in vivo, in part explained by mutant EF-G slowing the rate of protein synthesis and growth. However, some Fusr mutants with normal rates of protein synthesis still suffer from reduced fitness in vivo. As shown here, Fusr mutants could be similarly ranked in their relative fitness in mouse infection models, in a macrophage infection model, in their relative hypersensitivity to hydrogen peroxide in vivo and in vitro, and in the amount of RpoS production induced upon entry into the stationary phase. We identify a reduced ability to induce production of RpoS (σs) as a defect associated with Fusr strains. Because RpoS is a regulator of the general stress response, and an important virulence factor in Salmonella, an inability to produce RpoS in appropriate amounts can explain the low fitness of Fusr strains in vivo. The unfit Fusr mutants also produce reduced levels of the regulatory molecule ppGpp in response to starvation. Because ppGpp is a positive regulator of RpoS production, we suggest that a possible cause of the reduced levels of RpoS is the reduction in ppGpp production associated with mutant EF-G. The low fitness of Fusr mutants in vivo suggests that drugs that can alter the levels of global regulators of gene expression deserve attention as potential antimicrobial agents.

Fusidic acid is a steroidlike antibiotic that inhibits protein synthesis by binding to a complex of the ribosome and elongation factor G (EF-G) (26). Resistance to fusidic acid in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium is caused by mutations in fusA encoding EF-G (22). EF-G is a GTP-binding protein that catalyses the translocation of peptidyl-tRNA from the ribosomal A site to the P site (24, 37). After GTP hydrolysis and translocation, EF-G · GDP leaves the ribosome and is regenerated by the spontaneous exchange of GDP for GTP. Fusidic acid blocks the release of EF-G · GDP from the ribosome, thus inhibiting further protein synthesis. Phenotypes of Fusr mutants of EF-G include a reduced rate of GDP-to-GTP exchange that reduces the rate of protein synthesis and altered levels of the transcriptional regulator molecule ppGpp (guanosine 3′-biphosphate, 5′-biphospate) (29). ppGpp acts as a nutritional stress signal which binds to the β-subunit of RNA polymerase (10, 35) and reduces its affinity for promoters of stable RNA (17, 43) by inhibiting formation of a ternary transcription initiation complex (1, 23). The translational and transcriptional phenotypes of Fusr mutants can each be expected to have a negative impact on bacterial fitness. Throughout this paper the term fitness is used to describe the relative competitive ability of a mutant versus an isogenic wild type. Depending on the assay, differences in fitness can mean differences in growth rate or differences in survival in a particular environment.

The rpoS-encoded σs factor (RpoS) is required for expression of a large number of genes in response to various stresses, including nutrient limitation, osmotic challenge, acid shock, heat shock, oxidative damage, and growth into stationary phase (19). RpoS regulates Salmonella virulence and is essential during infection (13). S. enterica serovar Typhimurium is a facultative intracellular pathogen that, upon infection, resides in macrophages where it is exposed to a wide repertoire of antimicrobial effectors, including the phagocyte NAD(P)H oxidase (Phox). An initial oxidative bactericidal phase, associated with the production of superoxide anion and hydrogen peroxide, is followed by a bacteriostatic phase where nitric oxide is produced (38). The ability of S. enterica serovar Typhimurium to survive these stresses is an important determinant of its fitness in vivo (39).

Nutrient deprivation appears to be a critical environmental signal triggering the expression of Salmonella virulence genes within the phagosomes of host macrophages (12), and there is evidence that macrophages restrict the growth of phagocytosed organisms by limiting essential nutrients within the phagosome (31). The combination of nutrient restriction and stress conditions in the intracellular environment may be the stimulus for RpoS induction (11). Starvation also elevates the intracellular levels of ppGpp, whereas the synthesis of RpoS is positively regulated by ppGpp (15). In fact, ppGpp-deficient strains fail to synthesize RpoS as cells enter the stationary phase in a rich medium and under starvation (15). The major effects of ppGpp induction are not exerted on rpoS mRNA abundance or on protein turnover but instead affect translational efficiency (7). It was proposed that ppGpp indirectly regulates one or more additional factors specifically required for rpoS translation. Thus, intracellular S. enterica serovar Typhimurium may use ppGpp as a modulator of RpoS expression and thereby activate its adaptation to stress.

In the present study, we have investigated the fitness costs associated with several fusidic acid-resistant (Fusr) mutations in vivo. We show that the attenuated in vivo growth of Fusr mutants is associated with increased sensitivity to H2O2. We report that Fusr mutants have reduced levels of sigma factor RpoS. The relationship between decreased virulence of Salmonella with mutant EF-G forms, perturbed levels of ppGpp and reduced levels of RpoS is discussed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, media, and growth conditions.

All strains used are S. enterica serovar Typhimurium strains derived from the wild-type strains LT2 (TT10000 from the strain collection of John Roth, University of California, Davis) and ATCC 14028s. LT2-based strains were used in all experiments (in vivo and in vitro), except for competitions in macrophages and C57BL/6 mice, where strains derived from the more-virulent ATTC 14028s were required. LT2 has the advantage of being more defined genetically, whereas with 14028s, it is easier to establish infections in mice and macrophages. We have made comparisons of LT2 and 14028s with respect to growth kinetics in vivo (BALB/c mice), and they behave similarly, i.e., we can extrapolate the 14028s data to LT2. Furthermore, LT2 and 14028s survive stationary-phase and oxidative stresses equally well (41). Fusr mutations were moved between strains by P22-mediated transduction with a linked marker, zhb-736::Tn10 (21). Within each experiment the strains used were isogenic. We have determined that the zhb-736::Tn10 marker is selectively neutral for growth in our competition experiments in vivo and in vitro, and we have therefore used it to distinguish the wild-type and Fusr strains in competition experiments. The katE::Tn10 mutation was transduced from TYT3260, ATTC 14028s katE::Tn10 kindly supplied by Stanley Maloy. The katG knockout mutation was transduced from the strain TT19901, ATTC 14028s katG::pRR10 karE::Tn10 (pRR10 is an RK2-based minireplicon encoding β-lactam resistance), kindly supplied by Kim Bunny and John Roth. The rpoS-lacZ fusions used were transduced from the strains TE6253, putPA1303::KanR-rpoS-lacZ [pr] and TE6127, putPA1303::KanR-rpoS-lacZ [op], kindly supplied by Tom Elliott (6). Minimal growth medium is M9 salts supplemented with 0.2% glucose, 5 μg of thiamine ml−1, and amino acids at 40 μg ml−1 as required. Rich medium is Luria broth (LB). Antibiotics were tetracycline at 15 μg ml−1 and fusidic acid (sodium salt) at 800 μg ml−1 in the presence of 1 mM EDTA.

Measurement of bacterial viability in the presence of H2O2 in vitro.

From an overnight culture, 1 × 106 to 2 × 106 cells/ml were inoculated in minimal glucose medium containing 70 μM H2O2 and incubated at 37°C without shaking. Samples were taken at each hour over the course of 23 h, diluted, and spread onto LB plates. After overnight incubation at 37°C, CFU were counted. The remainder of each culture was further incubated for several additional days to determine whether any living cells remained after the H2O2 treatment. H2O2 was diluted in water from a 30% stock (Merck).

Competition assays in vivo.

BALB/c mice, C57BL/6 wild-type and isogenic Cybb knockout mice (34), and stock 002365 (Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, Maine) were housed at the Microbiology and Tumor Biology Center, Karolinska Institute (Stockholm, Sweden) in accordance with both institutional and national guidelines. Animal experiments were performed as described previously (2, 3) by using an intraperitoneal challenge. Competitions were run for one cycle of 3 to 4 days corresponding to about 10 generations of bacterial growth (3).

Competition assays in cell culture: J774-A.1 macrophages.

J774-A.1 cells (ATCC TIB 67) were cultivated in RPMI medium (Gibco) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco), l-glutamine (10 mM final concentration; Gibco), and HEPES (10 mM final concentration; Gibco). Batches of RPMI and fetal bovine serum were screened before use to ensure they did not contain endotoxin. Cells were infected with S. enterica serovar Typhimurium at a multiplicity of infection of 1. Briefly, bacteria were suspended in phosphate-buffered saline, opsonized for 30 min in vitro with 10% mouse serum, diluted in HEPES-buffered RPMI, and subsequently seeded onto J774-A.1 cells. Plates were centrifuged for 5 min at 1,000 × g. After 1 h of infection, extracellular bacteria were killed by treatment for 45 min with 50 μg of gentamicin/ml. For continued incubations, killing medium was replaced by maintenance medium containing gentamicin (10 μg/ml). The amount of intracellular bacteria was determined, at the indicated time intervals, by hypotonic lysis to release intracellular bacteria, after which viable cells were counted on agar plates. For the second growth cycle (16 to 32 h), intracellular bacteria were grown first in one set of cells, then released from host cells by hypotonic lysis, enriched, recoated with complement, and fed to fresh cells.

Measurements of ppGpp. (i) Basal ppGpp levels.

Bacterial cultures were grown in M9 minimal medium for at least 15 generations of exponential growth to an optical density at 460 nm (OD460) of 0.3 to 0.4. Cells (60 ml) were fixed with 6 ml of 1.9% formaldehyde, and nucleotides were extracted according to a published method (27). High-performance liquid chromatography analysis and quantification of ppGpp levels were performed as described previously (29).

(ii) Starvation-induced ppGpp levels.

Bacteria were grown in buffered morpholinepropanesulfonic acid (MOPS) minimal medium (5) with 0.2% glucose and 100 μCi of 32Pi (Amersham) ml−1 in a BioscreenC reader (Labsystems). Starvation was induced during exponential growth at an OD600 of 0.2 to 0.3 by the addition of α-methyl glucoside to a final concentration of 2.6% (18). Aliquots (20 μl) were removed every 15 s to microcentrifuge tubes containing 20 μl of cold 20% formic acid. Zero time points were taken immediately before the addition of α-methyl glucoside. Acid extracts were incubated on ice for 30 min and then centrifuged in a Microfuge. Samples (5 μl) of supernatant were applied to polyethyleneimine-cellulose plates (Macherey-Nagel) and chromatographed in 1.5 M KH2PO4, pH 3.0. Chromatograms were analyzed and quantified with a PhosphorImager with Molecular Dynamics software.

β-Galactosidase assays.

For measurements of rpoS-lacZ fusion induction upon entry into stationary phase, cultures were initially grown overnight at 37°C in LB medium and then diluted 100-fold in fresh LB medium. Samples from exponentially growing (E) and stationary-phase (S and S + 2) cultures were collected and assayed for β-galactosidase activity (30). Exponentially growing cells were collected at an OD600 of 0.3. Stationary-phase samples were taken from the cultures that were left to grow for an additional 1 h (S) or 3 h (S + 2) after reaching an OD600 of 0.5 (20). Appropriate dilutions of S and S + 2 samples were made in order to be approximately equal to the OD600 of the exponentially growing cells. The OD420 and OD540 were measured at intervals of 5 min in a BioscreenC machine. Miller units of β-galactosidase activity were calculated from the linear part of the curve OD420 = f (time [in minutes]), at approximately the same OD420 for all of the samples analyzed, with the formula OD420 − 1.75 × OD550/OD660 × time (in minutes) × volume of the sample (in milliliters) × 1,000. For measurements of lacZ-rpoS fusion induction upon glucose starvation, cultures were grown overnight in minimal M9 medium with 0.2% glucose. Cultures were diluted 50-fold in fresh media and grown to an OD600 of 0.2 to 0.3, at which time α-methyl glucoside was added to a final concentration of 2.6% (18). The cultures were left to incubate with shaking at 37°C for a further 5 and 30 min, at which times samples were taken and subjected to a standard β-galactosidase assay as described above.

RESULTS

Fitness of Fusr mutants in vitro does not correlate with their fitness in vivo.

EF-G Fusr mutants with reduced translation and growth rates in vitro (29) show, as expected, reduced fitness in vivo (3). To determine whether factors other than translation rate are relevant for fitness in vivo, we studied a collection of Fusr mutants for which the rate of protein synthesis was similar. Thus, we selected, from a strain carrying the unfit mutation fusA1, a set of strains carrying secondary mutations within EF-G that restore fitness in vitro, measured as exponential growth rate in glucose minimal media (21). These growth-rate-compensated (GRC) mutants retained, in most cases, resistance to fusidic acid, and the original fusA1 mutation and the alleles are referred to as fusA1-1 and fusA1-2, etc. (Table 1). The fitness of strains carrying these mutations in vivo was measured in competition against a fusidic acid-sensitive (Fuss) wild-type strain in a BALB/c mouse infection model (see Materials and Methods). The degree of fitness restoration in vitro versus in vivo for these GRC strains showed a very poor correlation (Table 1). Thus, while GRC mutants in vitro are restored to within a few percent of the wild-type growth rate, in vivo these same strains, although improved relative to the parental strain, have in many cases very slow growth rates. We concluded that Fusr mutations in EF-G can reduce fitness in vivo by a mechanism that does not correlate with the effects on the growth rate measured in vitro.

TABLE 1.

Relative fitness of the wild type and Fusr mutants in vitro and in vivod

| fusA allele | EF-G mutation(s) | Growth rate, in vitroa | Generation time, in vivob | MIC (μg/ml)c |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild type | Wild type | 1.00 | 1.00 | 100-200 |

| fusA1-1 | P413L, G13C | 0.98 | 0.94 | 200 |

| fusA1-2 | P413Q | 1.02 | 0.85 | 400 |

| fusA1-7 | P413V | 0.98 | 0.68 | 800 |

| fusA1-8 | P413L, A66V | 0.98 | 0.66 | 2,400 |

| fusA1-11 | P413L, F444L | 0.98 | 0.59 | 2,400 |

| fusA1-14 | P413L, V291E | 0.98 | 0.36 | 800 |

| fusA1-15 | P413L, T423I | 0.98 | 0.33 | >3,200 |

| fusA1 | P413L | 0.52 | 0.00 | 2,400 |

The in vitro growth rate is the relative growth rate in M9 glucose minimal medium, with that of the wild type set at 1.00.

The in vivo generation time is the relative generation time in BALB/c mice, with that of the wild type set at 1.00. Values are calculated from growth competition assays in a mouse intraperitoneal infection model as described previously (3) and are taken from this reference.

The MIC is the minimal inhibitory concentration of fusidic acid (in micrograms/milliliter) required to inhibit bacterial growth in a microtiter well assay (21).

All values are the arithmetic means of the results from at least four independent measurements.

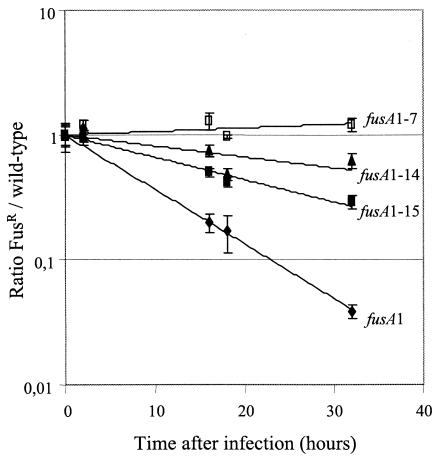

Fusr mutants have reduced fitness in macrophages.

The capacity to survive within macrophages is an absolute requirement for Salmonella virulence and, therefore, for fitness in vivo (14). We tested the relative fitness of the wild type and four Fusr strains during competition in a macrophage infection model (see Materials and Methods). Three Fusr mutants (fusA1, fusA1-14, and fusA1-15) previously found to be unfit in vivo (3) were also unfit in competition against the wild type in the macrophage assay (Fig. 1). In contrast, the Fusr mutant carrying fusA1-7, although unfit in vivo (3), competed effectively with the wild type in the macrophage assay. The lower fitness of the mutant with fusA1-7 in the mouse competition assays (Table 2) suggests that, in the more complex in vivo environment, it is subjected to stresses it does not meet in the macrophage assay. The order in which these four Fusr mutants were ranked in fitness under macrophage growth conditions was the same as that observed in the BALB/c in vivo model (Table 1).

FIG. 1.

Relative competitive ability of the wild type versus four different Fusr mutants in a macrophage infection. Conditions are described in Materials and Methods. With the exception of the time zero points (four independent measurements per assay), each point is the mean of the results from 7 to 11 independent measurements. Standard error bars (standard deviations of the means) are shown for each point.

TABLE 2.

Competition between the wild type and different Fusr mutant Salmonella strains in two strains of mice, wild-type C57BL/6 and Cybb mice

| Fusr mutant | Competition index (SE) in mouse straina:

|

Fold improvement | |

|---|---|---|---|

| C57BL/6 | Cybb | ||

| fusA1-7 | 5.1 × 10−1 (1.6 × 10−1) | 2.2 (5.0 × 10−1) | 4 |

| fusA1-14 | 2.2 × 10−3 (4.4 × 10−3) | 9.2 × 10−2 (2.2 × 10−2) | 42 |

| fusA1-15 | 1.2 × 10−3 (7.8 × 10−5) | 4.4 × 10−2 (1.5 × 10−2) | 37 |

| fusA1 | <10−6 | 4.6 × 10−5 (2.4 × 10−5) | >46 |

Each result is expressed as a competition index, which is the ratio of mutant to wild type at the end of one growth cycle/the ratio of mutant to wild type at time zero. Each data point is the arithmetic mean of the bacterial ratios from the livers of six mice.

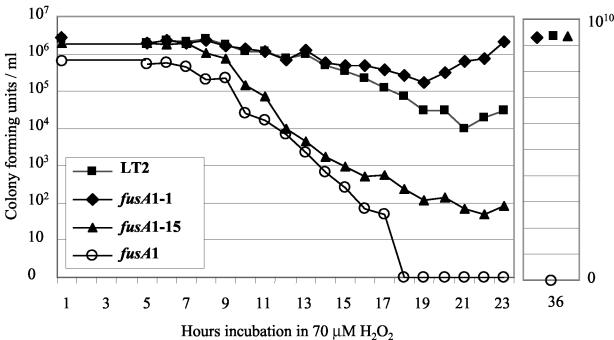

Fusr mutants lose viability in the presence of H2O2 in vitro.

Resistance to oxidative stress may be an important characteristic in the ability of Salmonella to withstand killing in phagocytic cells (31). One of the main determinants for the killing of Salmonella by macrophages is H2O2 (40). We tested whether Fusr mutants were sensitive to hydrogen peroxide in vitro by measuring survival in glucose minimal medium supplemented with 70 μM hydrogen peroxide. This concentration of hydrogen peroxide was used because it approximates the concentration generated during the respiratory burst (16, 25, 40) and because it distinguishes clearly between the different Fusr mutants. The experiment showed that bacterial growth was initially inhibited for several hours, after which a decrease in the viable count (CFU) was observed (Fig. 2). For the LT2 wild type and the fittest Fusr strain (fusA1-1), the CFU decreased from the initial ∼2 × 106 cells/ml to 1 × 104 (wild type) or 1.7 × 105 (fusA1-1) cells/ml. Thus, the Fusr mutant carrying fusA1-1 is more resistant than the wild type to exposure to H2O2, although it is slightly less fit in growth competition both in vitro and in vivo (Table 1). In contrast, the CFU of the Fusr mutant carrying fusA1-15 decreased from ∼2 × 106 cells/ml to only 50 cells/ml after 22 h of exposure to H2O2, before growth resumed. Although this number of cells is very small, multiple experiments confirmed that beginning with 106 cells results typically in about 5 logs of killing, with the survivors resuming growth. The Fusr mutant with the least fit allele, fusA1, was so sensitive in this assay that no cells survived. Multiple experiments confirm that this strain is so sensitive to H2O2 that reproducibly no cells survive in assays where ∼106 to 107 cells/ml are initially inoculated. With the exception of the strain carrying fusA1, each of the strains eventually resumed growth and, by 36 h, had reached a density of at least 109 CFU/ml (Fig. 2). We concluded that the oxidative stress caused by H2O2 reduced the viability of the unfit Fusr mutants relative to the wild type, inhibiting growth and causing cell death. Furthermore, the relative sensitivity of different Fusr mutants to H2O2 correlated with their relative in vivo fitness measured in the BALB/c mouse model (Fig. 2; additional data for the other Fusr mutants are not shown).

FIG. 2.

Growth inhibition and loss of viability of the wild type and Fusr mutants in the presence of H2O2. Approximately 106 CFU of each culture was inoculated into M9 glucose with 70 μM H2O2 and incubated at 37°C without shaking. Samples were taken at the indicated intervals, diluted, and plated onto LB plates to determine the number of CFU for each strain. The 36-h sample shows that growth had resumed for three of the four strains after the initial killing period. No growth occurred in the culture with the mutant carrying fusA1 even after several days of incubation. This experiment was repeated two to five times for each strain, and results from a representative experiment are shown.

In vivo sensitivity to hydrogen peroxide.

To test whether sensitivity to H2O2 is an important in vivo determinant of the fitness of Fusr mutants, we measured competitive ability in vivo in two different mouse strains: a wild-type strain, C57BL/6, and an isogenic strain carrying a targeted mutation in NADPH cytochrome b oxidase (Cybb). Cybb mice are unable to undergo a phagocyte oxidative burst. We observed that the fitness of three unfit Fusr mutants was improved in the Cybb mice by about 40-fold (Table 2). The strain carrying the fusA1-7 mutation was restored to wild-type fitness. We conclude that sensitivity to oxidative stress is a significant fitness parameter of the Fusr mutants. However, the fitness of the three least-fit Fusr mutants was not fully restored in the Cybb mice. The incomplete restoration of fitness may be because the Cybb mice still produce some H2O2 and almost twice as much nitric oxide as the wild-type mice (40). However, there may be additional factors that contribute to the low fitness of the Fusr mutants in vivo.

Reduced catalase activity associated with Fusr mutants.

The sensitivity of Fusr mutants to H2O2 in vitro and in vivo suggested to us that they might have reduced levels of catalase activity. We measured the rate of clearance of H2O2 from the growth medium (33, 42) and found that Fusr mutants, relative to the wild type, are slow at clearing H2O2 (data not shown). As a control, we showed that strains carrying insertion mutations in katE or katG had catalase activities reduced to 33 and 77% of the wild-type level, respectively. These experiments showed that Fusr mutants also had reduced catalase activity, down to 35% of wild-type activity in the case of fusA1. However, others have reported that catalase activity per se is not an important virulence factor (8). To assess directly the significance of catalase activity to in vivo fitness, we performed competition experiments with BALB/c mice. The wild type was competed against isogenic strains carrying either of two unfit Fusr mutations (fusA1 or fusA1-15) or carrying insertions inactivating katE or katG. The competition results (Table 3) showed that both Fusr strains were very unfit, as expected, but that the catalase mutations had little or no effect on the in vivo competition index. Our conclusion is that while Fusr mutants have reduced catalase activity, this phenotype does not explain their reduced fitness in vivo. This is in agreement with previous results showing that an S. enterica serovar Typhimurium double mutant (katE and katG) unable to produce either HPI or HPII catalase activity retains full virulence in macrophage and mouse assays (8).

TABLE 3.

Relative fitness of Fusr and catalase mutants competing against wild-type 14028s in BALB/c mice

| Relevant mutation | Competition indexa | SE |

|---|---|---|

| katE::Tn10 | 1.4 | 0.2 |

| katG::pRR10 | 0.4 | 0.08 |

| fusA1-15 | 0.002 | 0.001 |

| fusA1 | <0.0008 |

The competition index is the ratio of mutant to wild type at the end of one growth cycle/the ratio of mutant to wild type at time zero. Each result is the arithmetic mean of the bacterial ratios from at least four mice.

Basal and starvation-induced levels of ppGpp in Fusr mutants.

The fusA1 mutation, associated with low fitness both in vitro and in vivo, has reduced basal and starvation-induced levels of ppGpp (29). We assayed ppGpp levels in several GRC Fusr mutants to determine whether the ppGpp levels had been restored to wild-type levels. Basal levels of ppGpp were measured in exponentially growing cells by high-performance liquid chromatography analysis (see Materials and Methods). Wild-type LT2 had 15 pmol/OD460 while in fusA1 it was 5 pmol/OD460. In the GRC mutants, basal levels were restored (but not always exactly to the wild-type level) and ranged from 13 to 26 pmol/OD460, with no obvious correlation with their fitness in vivo (Table 4). Under glucose starvation conditions, the fusA1 strain converted only 10% of GTP into ppGpp compared with about 30% conversion for the wild-type strain. Conversion of GTP into ppGpp was restored to the wild-type level in the most-fit GRC Fusr mutants but not in the less fit mutants, fusA1-14 and fusA1-15 (Table 4). Thus, altered ppGpp-mediated gene regulation might be one factor in determining the relative fitness of these strains under stress conditions.

TABLE 4.

ppGpp level in Fusr strains

| fusA allele | Relative ppGpp levelc

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Basala | Inducedb | |

| Wild type | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| fusA1-1 | 0.9 | 1.3 |

| fusA1-2 | 1.4 | ND |

| fusA1-7 | 1.7 | 1.1 |

| fusA1-8 | 1.0 | ND |

| fusA1-11 | 1.2 | ND |

| fusA1-14 | 1.0 | 0.7 |

| fusA1-15 | 1.3 | 0.6 |

| fusA1 | 0.3 | 0.3 |

The basal level of the wild type is 15 pmol of ppGpp/OD460 of exponentially growing cells.

Induced levels are measured as the percent GTP converted into ppGpp 90 s after induction by the addition of α-methylglucoside. The value for the wild type is 29%. ND, not determined.

All results are the arithmetic means of the results from at least three independent experiments. Our detection level in measurements of basal levels of ppGpp was 1 pmol/OD460, and the variation between experiments is approximately ±2 pmol/OD460.

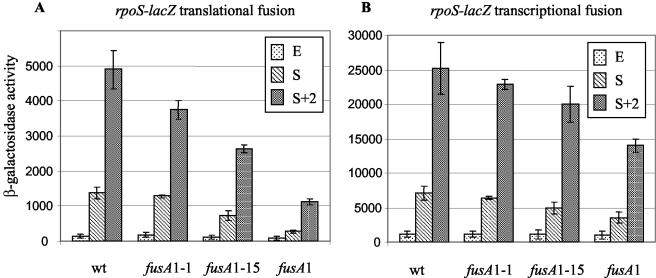

Expression rpoS-lacZ fusions in Fusr mutants.

Synthesis of RpoS is positively regulated by ppGpp (15). The rpoS-encoded σs factor regulates Salmonella virulence and is essential during infection (13). We measured the expression of rpoS in various Fusr mutants with perturbed starvation levels of ppGpp by using translational [pr] and transcriptional [op] rpoS-lacZ fusions (6). Expression of rpoS was measured on samples taken at three different points during growth. Samples from exponentially growing cultures (E) were taken at an OD600 of 0.3. Samples from cultures entering stationary phase (S) were taken 1 h after the time at which the OD600 reached 0.5 (20). This definition of S compensated for the slower growth rate of fusA1. A second stationary-phase sample (S + 2) was taken 3 h after the OD600 reached 0.5 (20). The β-galactosidase activity of the translational fusion, rpoS-lacZ [pr], in the wild-type strain was low during exponential growth but increased dramatically after entrance into stationary phase. In the wild type, the induction ratio (S + 2)/E was ∼30-fold (Fig. 3A), in agreement with published data (11, 20). The level of induction at S + 2 was close to maximal, and only a small further increase was associated with overnight incubation (data not shown). Relative to the wild type, each of the Fusr mutants tested induced rpoS-lacZ expression to a lesser extent upon entry into stationary-phase growth. Thus, at S + 2, the inductions associated with the various fusA mutations were 76, 54, and 23% of the wild-type level for fusA1-1, fusA1-15, and fusA1, respectively (Fig. 3A).

FIG. 3.

(A) Expression of rpoS-lacZ translational fusion in the wild type (wt) and Fusr mutants as a function of growth stage. E is exponential growth, S is 1 h after the OD600 reached 0.5, and S + 2 is 3 h after the OD600 reached 0.5. Values shown are the means of the results from three independent measurements. Standard error bars (standard deviations of the means) are shown for each point. The data in panel B are the same as described for panel A, except that the transcription activity from the rpoS promoter is being measured.

Similar assays were made with an rpoS-lacZ transcriptional fusion [op] in wild type and Fusr mutants (Fig. 3B). These showed that in the wild type, rpoS expression increased upon entry into the stationary phase (Fig. 3B). For the wild type, the transcription induction ratio (S + 2)/E was 22. This induction ratio is similar to published data (20). Of the three Fusr mutants, only the strain with the fusA1 mutation had significantly slower induction kinetics than the wild type, having 50 to 55% of wild-type levels at S and S + 2 (Fig. 3B). Taken together, the measurements of rpoS-lacZ fusions suggested that Fusr mutants with reduced in vivo fitness were defective in inducing rpoS upon entry into the stationary phase and that the defect is more pronounced at the posttranscriptional level.

The β-galactosidase assays on cells entering the stationary phase were made in LB medium to facilitate a direct comparison with published results (20) on rpoS induction upon entry into the stationary phase. We also made β-galactosidase assays on the rpoS-lacZ fusions in cells growing exponentially in minimal M9 glucose medium, where carbon starvation was induced by the addition of α-methyl-glucoside (see Materials and Methods). In the wild type, the rpoS-lacZ induction ratio after 30 min of starvation was ∼5-fold, as expected from the literature (19), while in the strains with fusA1 or fusA1-15, virtually no induction was detected (<2-fold). We conclude that Fusr mutants are defective in RpoS induction both under conditions of entry into the stationary phase and starvation stress, in rich and minimal medium.

DISCUSSION

Translation factor EF-G drives ribosomal movement through its interaction with the ribosomal A site. The A site on the ribosome is also where the transcription regulator molecule, ppGpp, is produced by the RelA protein. Fusidic acid is an antibiotic that targets EF-G in the ribosomal A site. Fusidic acid-resistant mutants (Fusr) of Salmonella have alterations in EF-G that decrease their sensitivity to the antibiotic (21, 22). It waspreviously shown that many of these Fusr mutants reduce growth and translation rate as could be expected for mutants of EF-G (29). More intriguingly, it was noted that Fusr mutants were also frequently disturbed in their production of ppGpp on the ribosome (29), suggesting that mutant EF-G can perturb not only translation, but also transcription regulation. Fusr mutants have also been shown to be unfit in vivo (3). Because of the perturbation of ppGpp levels in Fusr strains, we asked whether the loss of fitness associated with a Fusr phenotype in vivo could be associated with altered expression of one or more important genes, rather than simply being the result of a reduced growth rate. To determine this, we have made use of Fusr mutants with growth rates similar to those of the wild type (21). We measured the relative fitness of these Fusr mutants and found that many still have severe fitness defects in vivo (Table 1).

Why are Fusr mutants with a normal growth rate unfit in vivo?

Upon infection, Salmonella evokes a host immune response and is targeted and engulfed by macrophages (36). Here we showed that Fusr mutants could be similarly ranked in fitness in mice (Table 1) and in macrophages (Fig. 1). The relative fitness of Fusr mutants is improved in Cybb mutant mice that are incapable of mounting a normal phagocyte oxidative response (Table 2). This identifies sensitivity to oxidative attack as one factor determining the relative fitness of Fusr mutants in vivo. This link between in vivo fitness and sensitivity to the oxidative response is supported by the fact that Fusr strains are growth inhibited, and lose viability, in the presence of micromolar concentrations of hydrogen peroxide in vitro (Fig. 2). Sensitivity to hydrogen peroxide suggested to us that Fusr mutants might have a decreased catalase activity. We measured catalase activity in Fusr mutants and found that it was reduced in strains with low fitness in vivo. However, reduced catalase levels by themselves do not reduce Salmonella fitness in vivo (Table 3), as has also been observed by others (8). This showed that while Fusr mutants are sensitive to oxidative stress in vivo (Table 2), the cause of this sensitivity is not their reduced catalase activity per se.

One critical factor for Salmonella virulence is the stationary-phase sigma factor, RpoS (13). The Fusr strains are defective in ppGpp production (Table 4), a molecule that is proposed to be a positive regulator of RpoS levels (15). Thus, the Fusr mutants might have reduced levels of RpoS in the stationary phase or other stress conditions, and that may be the cause of their low fitness in vivo. In accordance with this idea, we found that fusA mutations were associated with reduced induction levels of rpoS. The effect was mainly at the level of rpoS translation, and the magnitude of the effect correlated with the in vivo fitness associated with a particular fusA mutation (Fig. 3). From these experiments we conclude that the reduced in vivo fitness of the Fusr mutants resulted from their failure to respond appropriately to stress conditions with a rapid induction of expression of RpoS sigma factor. The low level of induction may, in turn, be due to the reduced levels of ppGpp produced in Fusr mutants in response to stress signals (Table 4).

The RpoS sigma factor is induced in response to a variety of different stress conditions (19, 28), including nutrient starvation, growth phase shift, and oxidative damage. Cellular levels of ppGpp increase in response to each of these stress conditions (9). Thus, immunoblots revealed a 25- to 50-fold increase in RpoS when ppGpp was artificially induced, without starvation, and that a complete ppGpp0 deficiency blocked RpoS induction during starvation. The major effect of ppGpp induction on RpoS levels is exerted on the translational efficiency of the RpoS mRNA rather than on the rate of transcription or protein turnover (7). Expression of an rpoS-lacZ translational fusion increased rapidly in S. enterica serovar Typhimurium after phagocytosis, with over 70% of maximal induction occurring during the first 2 h (11). This suggests that the regulatory system mediated by RpoS is activated by the intracellular environment of eukaryotic cells (11). Our results suggest that some Fusr mutants reduce ppGpp induction levels under stress conditions and that one result of this is a reduced RpoS induction. A consequence for Salmonella is a reduction in the in vivo fitness of Fusr mutants.

Exploiting knowledge of in vivo fitness costs.

There have been several reports associating fitness costs in vivo with antibiotic resistance mutations (2-4, 32). In none of these cases has the specific nature of the in vivo fitness cost been identified. In terms of the Fusr mutants described here, we have found that there are at least two significant fitness costs associated with the resistance mutations. One cost, a reduced rate of protein synthesis, is relevant both in vivo and in vitro. The second cost identified here is reduced virulence associated with the failure of Fusr strains to properly induce RpoS expression in response to stress signals and is primarily relevant in vivo. Indeed, as shown here, Fusr mutants with a very small reduction in growth rate in vitro, are often significantly impaired in growth or survival in vivo. Determining the nature of the specific fitness costs associated with antibiotic resistance in vivo provides potential tools for improving how we deal with antibiotic-resistant strains. Such information could inform the choice of targets to be explored in screening programs for novel antibiotic drugs. Specifically, drugs that can alter the levels of ppGpp and/or RpoS, or indeed any other global regulator of gene expression, deserve attention as potential antimicrobial agents. In addition, we have noted that Fusr mutants disturb two central processes, translation and transcription, and it may be that this double hit makes it difficult for bacteria to genetically compensate for the resulting fitness loss. Thus, a second class of targets to be considered in drug screening programs would be those that occupy functional intersections between different important cellular processes.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge economic support from the Swedish Natural Science Council (to D.H. and D.I.A.); the Swedish Medical Research Council (to D.H., D.I.A., and M.R.); Leo Pharmaceuticals, Ballerup, Denmark (to D.H. and D.I.A); the EU (to D.H.); and the Swedish Institute for Infectious Disease Control (to D.I.A. and M.R.).

We thank Tom Elliott, Stanley Maloy, and John Roth's laboratory for providing strains and Måns Ehrenberg for critical reading of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bartlett, M. S., T. Gaal, W. Ross, and R. L. Gourse. 1998. RNA polymerase mutants that destabilize RNA polymerase-promoter complexes alter NTP-sensing by rrn P1 promoters. J. Mol. Biol. 279:331-345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Björkman, J., D. Hughes, and D. I. Andersson. 1998. Virulence of antibiotic-resistant Salmonella typhimurium. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:3949-3953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Björkman, J., I. Nagaev, O. G. Berg, D. Hughes, and D. I. Andersson. 2000. Effects of environment on compensatory mutations to ameliorate costs of antibiotic resistance. Science 287:1479-1482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Björkman, J., P. Samuelsson, D. I. Andersson, and D. Hughes. 1999. Novel ribosomal mutations affecting translational accuracy, antibiotic resistance and virulence of Salmonella typhimurium. Mol. Microbiol. 31:53-58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bochner, B. R., and B. N. Ames. 1982. Complete analysis of cellular nucleotides by two-dimensional thin layer chromatography. J. Biol. Chem. 257:9759-9769. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown, L., and T. Elliott. 1996. Efficient translation of the RpoS sigma factor in Salmonella typhimurium requires host factor I, an RNA-binding protein encoded by the hfq gene. J. Bacteriol. 178:3763-3770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brown, L., D. Gentry, T. Elliott, and M. Cashel. 2002. DksA affects ppGpp induction of RpoS at a translational level. J. Bacteriol. 184:4455-4465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buchmeier, N. A., S. J. Libby, Y. Xu, P. C. Loewen, J. Switala, D. G. Guiney, and F. C. Fang. 1995. DNA repair is more important than catalase for Salmonella virulence in mice. J. Clin. Investig. 95:1047-1053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cashel, M., D. R. Gentry, V. J. Hernandez, and D. Vinella. 1996. The stringent response, p. 1458-1496. In F. C. Neidhardt et al. (ed.), Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology, 2nd ed., vol. 1. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 10.Chatterji, D., N. Fujita, and A. Ishihama. 1998. The mediator for stringent control, ppGpp, binds to the beta-subunit of Escherichia coli RNA polymerase. Genes Cells 3:279-287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen, C. Y., L. Eckmann, S. J. Libby, F. C. Fang, S. Okamoto, M. F. Kagnoff, J. Fierer, and D. G. Guiney. 1996. Expression of Salmonella typhimurium rpoS and rpoS-dependent genes in the intracellular environment of eukaryotic cells. Infect. Immun. 64:4739-4743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fang, F. C., M. Krause, C. Roudier, J. Fierer, and D. G. Guiney. 1991. Growth regulation of a Salmonella plasmid gene essential for virulence. J. Bacteriol. 173:6783-6789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fang, F. C., S. J. Libby, N. A. Buchmeier, P. C. Loewen, J. Switala, J. Harwood, and D. G. Guiney. 1992. The alternative sigma factor katF (rpoS) regulates Salmonella virulence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89:11978-11982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fields, P. I., R. V. Swanson, C. G. Haidaris, and F. Heffron. 1986. Mutants of Salmonella typhimurium that cannot survive within the macrophage are avirulent. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 83:5189-5193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gentry, D. R., V. J. Hernandez, L. H. Nguyen, D. B. Jensen, and M. Cashel. 1993. Synthesis of the stationary-phase sigma factor sigma s is positively regulated by ppGpp. J. Bacteriol. 175:7982-7989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gonzalez-Flecha, B., and B. Demple. 2000. Genetic responses to free radicals. Homeostasis and gene control. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 899:69-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hamming, J., G. Ab, and M. Gruber. 1980. E coli RNA polymerase-rRNA promoter interaction and the effect of ppGpp. Nucleic Acids Res. 8:3947-3963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hansen, M. T., M. L. Pato, S. Molin, N. P. Fill, and K. von Meyenburg. 1975. Simple downshift and resulting lack of correlation between ppGpp pool size and ribonucleic acid accumulation. J. Bacteriol. 122:585-591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hengge-Aronis, R. 2002. Signal transduction and regulatory mechanisms involved in control of the sigma(S) (RpoS) subunit of RNA polymerase. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 66:373-395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hirsch, M., and T. Elliott. 2002. Role of ppGpp in rpoS stationary-phase regulation in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 184:5077-5087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johanson, U., A. Aevarsson, A. Liljas, and D. Hughes. 1996. The dynamic structure of EF-G studied by fusidic acid resistance and internal revertants. J. Mol. Biol. 258:420-432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johanson, U., and D. Hughes. 1994. Fusidic acid-resistant mutants define three regions in elongation factor G of Salmonella typhimurium. Gene 143:55-59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jores, L., and R. Wagner. 2003. Essential steps in the ppGpp-dependent regulation of bacterial ribosomal RNA promoters can be explained by substrate competition. J. Biol. Chem. 278:16834-16843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Katunin, V. I., A. Savelsbergh, M. V. Rodnina, and W. Wintermeyer. 2002. Coupling of GTP hydrolysis by elongation factor G to translocation and factor recycling on the ribosome. Biochemistry 41:12806-12812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kaul, N., and H. J. Forman. 1996. Activation of NF kappa B by the respiratory burst of macrophages. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 21:401-405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Laurberg, M., O. Kristensen, K. Martemyanov, A. T. Gudkov, I. Nagaev, D. Hughes, and A. Liljas. 2000. Structure of a mutant EF-G reveals domain III and possibly the fusidic acid binding site. J. Mol. Biol. 303:593-603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Little, R., and H. Bremer. 1982. Quantitation of guanosine 5′, 3′-bisdiphosphate in extracts from bacterial cells by ion-pair reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography. Anal. Biochem. 126:381-388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Loewen, P. C., B. Hu, J. Strutinsky, and R. Sparling. 1998. Regulation in the rpoS regulon of Escherichia coli. Can. J. Microbiol. 44:707-717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Macvanin, M., U. Johanson, M. Ehrenberg, and D. Hughes. 2000. Fusidic acid-resistant EF-G perturbs the accumulation of ppGpp. Mol. Microbiol. 37:98-107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miller, J. H. 1992. A short course in bacterial genetics: a laboratory manual and handbook for Escherichia coli and related bacteria. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Plainview, N.Y.

- 31.Murray, H. W. 1988. Interferon-gamma, the activated macrophage, and host defense against microbial challenge. Ann. Intern. Med. 108:595-608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nagaev, I., J. Bjorkman, D. I. Andersson, and D. Hughes. 2001. Biological cost and compensatory evolution in fusidic acid-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Mol. Microbiol. 40:433-439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Paul, K. G., P. I. Ohlsson, and N. A. Jonsson. 1982. The assay of peroxidases by means of dicarboxidine on enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay level. Anal. Biochem. 124:102-107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pollock, J. D., D. A. Williams, M. A. Gifford, L. L. Li, X. Du, J. Fisherman, S. H. Orkin, C. M. Doerschuk, and M. C. Dinauer. 1995. Mouse model of X-linked chronic granulomatous disease, an inherited defect in phagocyte superoxide production. Nat. Genet. 9:202-209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reddy, P. S., A. Raghavan, and D. Chatterji. 1995. Evidence for a ppGpp-binding site on Escherichia coli RNA polymerase: proximity relationship with the rifampicin-binding domain. Mol. Microbiol. 15:255-265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Richter-Dahlfors, A., A. M. Buchan, and B. B. Finlay. 1997. Murine salmonellosis studied by confocal microscopy: Salmonella typhimurium resides intracellularly inside macrophages and exerts a cytotoxic effect on phagocytes in vivo. J. Exp. Med. 186:569-580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rodnina, M. V., A. Savelsbergh, V. I. Katunin, and W. Wintermeyer. 1997. Hydrolysis of GTP by elongation factor G drives tRNA movement on the ribosome. Nature 385:37-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vazquez-Torres, A., and F. C. Fang. 2001. Oxygen-dependent anti-Salmonella activity of macrophages. Trends Microbiol. 9:29-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vazquez-Torres, A., and F. C. Fang. 2001. Salmonella evasion of the NADPH phagocyte oxidase. Microbes Infect. 3:1313-1320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vazquez-Torres, A., J. Jones-Carson, P. Mastroeni, H. Ischiropoulos, and F. C. Fang. 2000. Antimicrobial actions of the NADPH phagocyte oxidase and inducible nitric oxide synthase in experimental salmonellosis. I. Effects on microbial killing by activated peritoneal macrophages in vitro. J. Exp. Med. 192:227-236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wilmes-Riesenberg, M. R., J. W. Foster, and R. Curtiss III. 1997. An altered rpoS allele contributes to the avirulence of Salmonella typhimurium LT2. Infect. Immun. 65:203-210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Winquist, L., U. Rannug, A. Rannug, and C. Ramel. 1984. Protection from toxic and mutagenic effects of H2O2 by catalase induction in Salmonella typhimurium. Mutat. Res. 141:145-147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang, X., P. Dennis, M. Ehrenberg, and H. Bremer. 2002. Kinetic properties of rrn promoters in Escherichia coli. Biochimie 84:981-996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]