Abstract

Background: Liposomal cisplatin is a new formulation developed to reduce the systemic toxicity of cisplatin while simultaneously improving the targeting of the drug to the primary tumor and to metastases by increasing circulation time in the body fluids and tissues. The primary objectives were to determine nephrotoxicity, gastrointestinal side-effects, peripheral neuropathy and hematological toxicity and secondary objectives were to determine the response rate, time to tumor progression (TTP) and survival.

Patients and methods: Two hundred and thirty-six chemotherapy-naive patients with inoperable non-small-cell lung cancer were randomly allocated to receive either 200 mg/m2 of liposomal cisplatin and 135 mg/m2 paclitaxel (arm A) or 75 mg/m2 cisplatin and 135 mg/m2 paclitaxel (arm B), once every 2 weeks on an outpatient basis. Two hundred and twenty-nine patients were assessable for toxicity, response rate and survival. Nine treatment cycles were planned.

Results: Arm A patients showed statistically significant lower nephrotoxicity, grade 3 and 4 leucopenia, grade 2 and 3 neuropathy, nausea, vomiting and fatigue. There was no significant difference in median and overall survival and TTP between the two arms; median survival was 9 and 10 months in arms A and B, respectively, and TTP was 6.5 and 6 months in arms A and B, respectively.

Conclusions: Liposomal cisplatin in combination with paclitaxel has been shown to be much less toxic than the original cisplatin combined with paclitaxel. Nephrotoxicity in particular was negligible after liposomal cisplatin administration. TTP and survival were similar in both treatment arms.

Keywords: liposomal cisplatin, NSCLC

introduction

For three decades now, cisplatin has been a basic cytotoxic agent used for the treatment of stage III and IV non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Cisplatin-based doublet chemotherapy consisting of docetaxel, paclitaxel, gemcitabine or vinorelbine combinations is commonly administered as first-line treatment of NSCLC [1, 2]. Carboplatin is often used instead of cisplatin in the combination [3]. The adoption of cisplatin provided a survival advantage and a higher response rate since the start of its use; however, its major problem has been mainly nephrotoxicity [3]. A main substitute agent is the analogue carboplatin [4, 5] but also other combined agents including taxanes (paclitaxel, docetaxel) or gemcitabine, vinorelbine, pemetrexed and irinotecan have been used [6–14]. Liposomal cisplatin (Lipoplatin; Regulon Inc., Mountain View, CA) is formed from cisplatin and liposomes composed of dipalmitoyl phosphatidyl glycerol, soy phosphatidyl choline (SPC-3), cholesterol and methoxypolyethylene glycol-distearoyl phosphatidylethanolamine (mPEG2000-DSPE). Lipoplatin was developed in order to reduce the systemic toxicity of cisplatin. Preclinical studies have shown lipoplatin's lower nephrotoxicity in rats when compared with cisplatin [15]. Lipoplatin showed reduced renal toxicity in mice and rats, whereas animals injected with cisplatin developed renal insufficiency with clear evidence of tubular damage [16]. Two phase I studies have tested lipoplatin's pharmacokinetic profile and adverse reactions [17] and preferential tumor uptake of this agent in human studies [18]. Lipoplatin has been administered in 1 l 5% dextrose by an 8-h infusion. The highest plasma concentration was detected at 8 h and the platinum levels dropped to normal after 4–7 days [17]. Lipoplatin was ‘tested’ in combination with gemcitabine in a phase I–II trial of advanced pancreatic cancer where doses higher than 100–150 mg/m2 of lipoplatin were well tolerated [19]. Other trials have shown low or negligible nephrotoxicity and tumor effectiveness in vivo and in vitro [19, 20]. The dose of lipoplatin administered alone is tolerated even at the level of 350 mg/m2 (G.P. Stathopoulos, S.K. Rigatos, J. Stathopoulos, in press). The present study was designed to compare the toxicity, effectiveness and survival of patients ineligible for resection with NSCLC. The primary objectives were to determine nephrotoxicity, gastrointestinal (GI) side-effects, peripheral neuropathy and hematological toxicity and secondary objectives were to determine the response rate, time to tumor progression (TTP) and survival.

patients and methods

patients’ eligibility

Eligibility for the study required chemotherapy-naive patients with histologically or cytologically confirmed NSCLC; patients were to be classified as stage IIIb and IV, or stage IIIa not amenable to curative treatment (surgery), and to have bidimensionally measurable disease on physical examination, X-rays, computed tomography (CT), Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status (PS) of zero to two, expected survival ≥12 weeks, adequate bone marrow reserves (leukocyte count ≥ 3500/μl, platelet count ≥ 100 000/μl and hemoglobin ≥ 10 g/μl), adequate renal function (serum creatinine ≤ 1.5 mg/dl) and liver function (serum bilirubin ≤ 1.5 mg/dl and serum transaminases ≤three times the upper limit of normal or ≤five times the upper limit of normal in cases of liver metastases), and age ≥ 18 years. In cases of central nervous system involvement, patients were excluded unless they were asymptomatic. Patients with a second malignancy were also excluded.

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice Guidelines [21] and was approved by both participating institutional ethics review boards. All patients gave their informed consent before entering the study.

study design

The study was designed as a multicenter phase III trial by the institutional boards of the seven participating clinics of two hospitals. The study was powered at 80% to detect a difference in nephrotoxicity as well as in other side-effects, such as GI (nausea–vomiting), neurotoxicity and asthenia. The sample size was initially planned to include 100 patients in each arm with an increase in the number of patients if a statistical difference of 5% between the two arms, with regard to toxicity, was not reached. The randomization was carried out centrally and patients were stratified by three prognostic variables: disease stage (locally advanced versus metastatic), PS (ECOG 0–2) and investigational site.

treatment plan

Patients were randomly assigned to arm A or arm B. Arm A patients were to be treated with lipoplatin 200 mg/m2 in combination with paclitaxel 135 mg/m2. Lipoplatin was infused in 1 l 5% dextrose for 8 h without an extra infusion for hydration. Paclitaxel, which was given before lipoplatin, was infused for 3 h. Arm B patients were also given paclitaxel 135 mg/m2 for 3 h and cisplatin 75 mg/m2 in 250 mg normal saline solution accompanied by 1 l 5% dextrose and 1 l electrolyte, the same day. Premedication included ondasetron 8 mg i.v., dexamethasone 8 mg i.v. and diphenyldramine hydrochloride 50 mg i.v. with modified timing 1 h before the beginning of treatment and repeated 4 and 8 h thereafter. Treatment of both arms was repeated every 2 weeks; the every 2-week treatment repetition has been tested in other trials [8, 22–24]. Nine cycles were planned. By repeating the treatment every 2 weeks instead of every 3 weeks, the doses of cisplatin and paclitaxel were reduced to 75 mg/m2 instead of 100 mg/m2 [24] for the former and 135 mg/m2 instead of 175 mg/m2 for the latter. Patients who responded to treatment continued to the end of the planned number of courses. Course delays of 1 week were permitted for recovery from adverse events. Concomitant supportive therapies, such as granulocyte colony-stimulating factors or blood transfusions, antibiotics and erythropoietic agents were allowed according to the American Society of Clinical Oncology guidelines [25].

baseline and treatment assessment and evaluation

Before study entry, all patients underwent the following evaluations: medical history, physical examination, tumor measurement or evaluation, ECOG PS, electrocardiogram, full blood count, liver and kidney function tests, ‘serum creatinine’, ‘creatinine clearance’ and urinalysis. Staging was determined by chest and abdominal CT, bone scan and occasionally magnetic resonance imaging. Blood count, blood urea and serum creatinine were measured before each treatment administration and 7 days after each course. In cases where patients had serum creatinine levels higher than normal, creatinine clearance was carried out. Patients with abnormal creatinine clearance were excluded from the study. The glomerular filtration rate, type Cockroft–Gault, was not determined at baseline or during the trial. During the treatment period, radiologic tests were conducted after four courses, at the end of the study and after any course if the clinical signs were indicative of disease progression. Disease status was assessed according to the RECIST [26].

Randomly assigned patients who met the eligibility criteria and who had baseline data were considered assessable for tumor response and duration of response. All patients in both arms who received at least one dose (course) of treatment were considered assessable for safety. Patients were assessed for toxicity according to the National Cancer Institute—Common Toxicity Criteria, version 2.0 [27]. A complete response (CR) was considered to be the disappearance of all measurable disease confirmed at 4 weeks at the earliest; a partial response (PR), a 30% decrease in all measurable disease, also confirmed at 4 weeks at the earliest. In stable disease (SD), neither the PR nor the progressive disease (PD) criteria were met; PD was considered to be a 20% increase of tumor burden and no CR, PR, or SD documented before increased disease. A two-step deterioration in PS, a >10% loss of pretreatment weight or increasing symptoms did not by themselves constitute progression of the disease; however, the appearance of these complaints was followed by a new evaluation of the extent of the disease. All responses had to be maintained for at least 4 weeks and be confirmed by an independent panel of radiologists and oncologists.

statistical analysis

The main end point for sample-size determination was toxicity [myelotoxicity, nephrotoxicity, neurotoxicity, GI side-effects and asthenia]. In order to detect a ±difference at a 3-year time point, 200 patients were needed in order to have 80% power at the 5% significance level.

Patients were randomly assigned to the two treatment arms: A, lipoplatin plus paclitaxel and B, cisplatin plus paclitaxel. Randomization was carried out according to the method of random permuted blocks within strata. The stratification factor comprised stages IIIa, IIIb and IV. Dynamic balancing by center was also carried out. For time to disease progression and overall survival (OS), the Kaplan–Meier method was used to estimate survival distribution and the log-rank test for the comparison of the treatment arms. An interim analysis on the basis of the O'Brien–Flemming boundary values was carried out when 50% of the end point (100 deaths) was reached.

For response rates and the presence of toxic effects, comparisons of the two treatment arms were done by the χ2 test or the Fisher's exact test, when appropriate. The Mann–Whitney U test was used for toxicity grade comparisons. All tests were two sided. A P value <0.05 (Pearson's chi-square test) was considered significant. The duration of response was calculated from the day of the first demonstration of response until PD. TTP was calculated from the day of entry into the study until documented PD. OS was calculated from the day of enrollment until death, or to the end of the study.

results

From April 2006 until September 2008, a total of 236 patients were enrolled in this multicenter trial. Two hundred and twenty-nine patients were assessable for toxicity, response and survival. Seven patients refused to undergo the treatment. One hundred and fourteen patients in arm A and 115 in arm B were assessable for safety and efficacy. The patients’ characteristics are shown in Table 1. In this table, gender, age, PS and histological tumor differentiation are analytically presented for both arms. The great majority of patients were stage IIIb and IV (102 arm A: 41 stage IIIb and 61 stage IV and 100 arm B: 43 stage IIIb and 57 stage IV). Twelve patients from Arm A and 15 from Arm B of stage IIIa were considered to be ineligible for resection due to: (a) respiratory insufficiency, (b) stage IIIaN2 inoperable, confirmed by mediastinoscopy.

Table 1.

Patient demographics and disease characteristics at baseline

| Arm A, n (%) | Arm B, n (%) | Total, n (%) | |

| No. of patients treated | 114 | 115 | 229 |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 104 | 99 | 203 |

| Female | 10 | 16 | 26 |

| Age (years) | |||

| Median | 65 | 66 | |

| Range | 37–80 | 41–85 | |

| ECOG performance status | |||

| 0 | 25 (21.93) | 23 (20.0) | 48 (20.96) |

| 1 | 75 (65.79) | 77 (66.96) | 152 (66.38) |

| 2 | 14 (12.28) | 15 (13.04) | 29 (12.66) |

| Histology (cytology) | |||

| Adenocarcinoma | 43 (37.72) | 44 (38.26) | 87 (37.99) |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 33 (28.95) | 36 (31.30) | 69 (30.13) |

| Undifferentiated NSCLCa | 34 (29.82) | 34 (29.57) | 68 (29.69) |

| Large cell carcinoma | 3 (2.63) | 0 | 3 (1.31) |

| Squamous + adenocarcinoma | 1 (0.88) | 1 (0.87) | 2 (0.87) |

| Differentiation | |||

| Well | – | 3 (2.61) | 3 (1.31) |

| Moderate | 28 (24.56) | 34 (29.57) | 62 (27.07) |

| Poor–undifferentiated | 85 (74.56) | 78 (67.83) | 163 (71.18) |

| Disease stage | |||

| IIIa | 12 (10.53) | 15 (13.04) | 27 (11.79) |

| IIIb | 41 (35.96) | 43 (37.39) | 84 (36.68) |

| IV | 61 (53.51) | 57 (49.57) | 118 (51.53) |

Nonclassified by cytology.

ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; NSCLC, non-small-cell lung cancer.

safety

Tables 2 and 3 show toxicity/statistical differences and toxicity by grade, respectively. A difference that was statistically significant was temporary nephrotoxicity or its buildup over the number of cycles. Nephrotoxicity in arm A patients treated with lipoplatin–paclitaxel was 6.1%, while for arm B patients treated with cisplatin–paclitaxel, it was 40.0%, P value < 0.001. Some arm A patients had increased blood urea and serum creatinine but this was temporary and these patients eventually received the full nine cycles. Other side-effects with a statistically significant difference occurred in arm B where GI tract nausea, vomiting and fatigue were worse than in arm A. Myelotoxicity was higher in arm B patients and the difference was statistically significant for grade 3–4 neutropenia. Six patients in arm A and 10 in arm B were hospitalized due to febrile neutropenia. Anemia was common: 43.9% in arm A and 54.9% in arm B. Grades 1–4 leucopenia were 33.3% and 45.2% in arm A and B patients, respectively; grades 3 and 4 leucopenia were 12.3% and 2.6%, respectively, in arm A and 18.3% and 8.7%, respectively, in arm B (Table 2; statistically significant difference P value 0.017). Asthenia was more common in arm B patients (71.3% versus 57% in arm A, P value 0.019). The side-effect comparison was carried out for 229 patients in total.

Table 2.

Toxicity/statistical differences

| Toxicity grade 1–4 | Arm A, n (%) | Arm B, n (%) | P valuea |

| Anemia | 50 (43.9) | 62 (54.9) | 0.112 |

| Leucopenia (neutropenia) | 38 (33.3) | 52 (45.2) | 0.017 |

| Thrombocytopenia | 2 (1.8) | 3 (2.6) | 1.000b |

| Nephrotoxicity (renal) | 7 (6.1) | 46 (40.0) | <0.001 |

| Neurotoxicity | 52 (45.6) | 63 (54.8) | 0.145 |

| GI toxic nausea–vomiting | 37 (32.5) | 52 (45.2) | 0.042 |

| GI diarrhea | 2 (1.8) | 3 (2.6) | 1.000b |

| Asthenia | 65 (57.0) | 82 (71.3) | 0.019 |

| Alopecia | 96 (84.2) | 87 (75.7) | 0.134 |

Pearson's chi-square test.

Fisher's exact test.

GI, gastrointestinal.

Table 3.

Toxicity by grade

| Arm A |

Arm B |

|||||

| Grade 1–2, n (%) | Grade 3, n (%) | Grade 4, n (%) | Grade 1–2, n (%) | Grade 3, n (%) | Grade 4, n (%) | |

| Anemia | 46 (40.4) | 4 (3.5) | – | 55 (47.8) | 7 (6.1) | – |

| Leucopenia (neutropeniaa) | 21 (18.4) | 14 (12.3) | 3 (2.6) | 21 (18.3) | 21 (18.3) | 10 (8.7) |

| Thrombocytopenia | 1 (0.9) | 1 (0.9) | – | 3 (2.6) | – | – |

| Nephrotoxicity | 6 (5.3) | 1 (0.9) | – | 40 (34.8) | 5 (4.3) | – |

| Neurotoxicity | 51 (44.7) | 1 (0.9) | – | 58 (50.4) | 5 (4.3) | – |

| Nausea–vomiting | 37 (32.5) | – | – | 51 (44.3) | 1 (0.9) | – |

| Diarrhea | 2 (1.8) | – | – | 2 (1.7) | 1 (0.9) | – |

| Asthenia | 65 (57.0) | – | – | 71 (61.7) | 11 (9.6) | – |

| Alopecia | 63 (55.3) | 33 (28.9) | – | 58 (50.4) | 29 (25.2) | – |

Six patients in arm A and 10 in arm B had febrile neutropenia.

compliance with treatment

For the response rate, 229 (114 arm A and 115 arm B) patients were evaluated. A total of 666 cycles were administered to arm A patients and 634 to arm B. The median number of cycles was six in both arms. The number of planned protocol cycles (nine) was completed in 46 patients in arm A and 43 in arm B. Treatment was delayed for 1 week due to grade 4 leucopenia in 3 (2.6%) arm A patients and in 10 (8.7%) arm B patients; these patients received granulocyte growth factor support. Extra hydration due to vomiting was given to 4 (3.5%) arm A patients and to 23 (20%) arm B patients. Blood transfusion was given during treatment to four (3.5%) patients in arm A and to seven (6.1%) patients in arm B.

At the time of evaluation, 128 (55.9%) patient deaths (events) had occurred: 63 (55.3%) in arm A and 65 (56.5%) in arm B; 111 (86.7%) died due to the disease, 7 (5.5%) of a heart attack, 5 (3.9%) due to infection, 3 (2.3%) due to pulmonary embolism and 1 (0.78%) because of aneurysm rupture, brain episode and bone fracture. There was no difference in the cause of death between arm A and arm B patients. The median follow-up was 15 months and the range was 6–33 months.

response

Of the intent-to-treat 229 patients, a response was observed in total in 122 patients (53.3%). In arm A, there was one CR on the basis of CT examination (0.9%). Sixty-seven patients achieved a PR (58.8%). SD was seen in 42 (36.8%) patients and disease progression in 4 (3.5%). In arm B, no CR was observed. A PR was observed in 54 (47%) patients, SD in 50 (43.5%) patients and disease progression in 11 (9.6%) (Table 4). No statistically significant difference was shown in the results between arm A and arm B. During the study process, there were two preliminary evaluations, first at the level of 60 patients and second at 130. These two evaluations showed a response rate between the two arms which was close to being statistically significant. By increasing the number of patients to 229, the difference with regard to response rate remained at no statistically significant difference.

Table 4.

Response rate/survival time (months) (log-rank test P value 0.577)

| Response rate | Arm |

Total |

P valuea | |

| A | B | |||

| CR | ||||

| n | 1 | 0 | 1 | – |

| % within arm | 0.9 | 0.0 | 0.4 | – |

| PR | ||||

| n | 67 | 54 | 121 | |

| % within arm | 58.8 | 47.0 | 52.8 | 0.073 |

| SD | ||||

| n | 42 | 50 | 92 | |

| % within arm | 36.8 | 43.5 | 40.2 | 0.306 |

| PD | ||||

| n | 4 | 11 | 15 | |

| % within arm | 3.5 | 9.6 | 6.6 | 0.064 |

| Total | ||||

| n | 114 | 115 | 229 | |

| Survival time | ||||

| n | 114 | 115 | 229 | |

| Median | 9.0 | 10.0 | 10.0 | |

| 95% CI | 6.2–11.8 | 6.8–13.2 | 8.3–11.7 | |

Pearson's chi-square test.

CR, complete response; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease; PD, progressive disease; CI, confidence interval.

postcontinuation therapies/second line

According to the study protocol, patients of either arm could undergo second-line chemotherapy in case of disease progression or recurrence. The cytotoxic agents administered were a combination of pemetrexed and docetaxel. Twelve (10.5%) and 10 (8.7%) arm A and B patients, respectively, were given the above combination with the number of cycles ranging from two to six. The outcome was SD in all patients of both arms. Radiation therapy was also administered to a small percentage of patients: eight arm A patients underwent radiotherapy for brain or bone metastasis and one for the primary site of the disease. Eight arm B patients underwent radiotherapy, six for brain or bone metastasis and two for the primary site of the disease. Two patients achieved a PR.

In two patients (one in each arm, stage IIIa and IIIb), after a PR, the disease was considered operable and a successful operation was carried out.

The fact that a small equal number of patients in each arm had second-line treatment and no response was observed shows that the second-line treatment did not influence the survival data. Two patients, one in each arm, who had undergone surgery were alive and without recurrence at the end of the study.

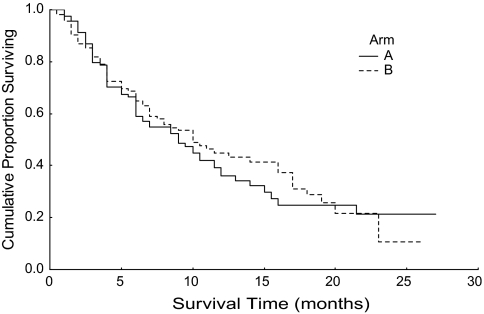

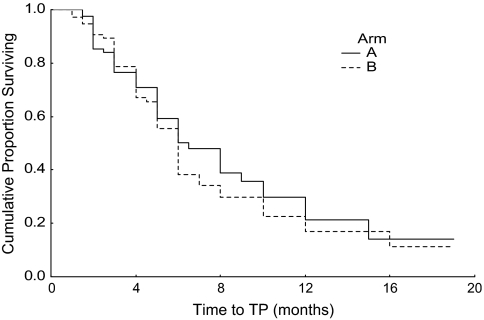

survival data

The median survival of patients of arm A was 9 months [95% confidence interval (CI) 6.2–11.8]; for arm B, median survival was 10 months (95% CI 6.8–13.2). The difference was not statistically significant, P value 0.577. These data are shown in Table 4. The Kaplan–Meier survival curve is shown in Figure 1. For arm A and B patients, median TTP was 6.5 months (95% CI 4.7–8.3) and 6 months (95% CI 5.3–6.7), respectively, P value 0.464. Figure 2 shows the Kaplan–Meier curve for TTP.

Figure 1.

Kaplan–Meier survival curve (arm A, 95% CI 6.2–11.8; arm B, 95% CI 6.8–13.2). CI, confidence interval.

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier TTP. TTP, time to tumor progression.

discussion

Liposomal cisplatin was produced to overcome the toxicity of cisplatin, particularly nephrotoxicity. Certainly, its effectiveness should not be inferior to cisplatin. A number of studies have been carried out before our decision to run the present trial. The administration of single lipoplatin has been tested to define the dose-limiting toxicity and 350 mg/m2 was not accompanied by nephrotoxicity but only GI side-effects and grade 1–2 myelotoxicity (G.P. Stathopoulos, S.K. Rigatos, J. Stathopoulos, in press). When lipoplatin is combined with another agent such as gemcitabine, paclitaxel or 5-fluorouracil (5-FU), the maximum tolerated dose is 200 mg/m2 (G.P. Stathopoulos, S.K. Rigatos, J. Stathopoulos, in press). A trial in 2007 documented the combination of lipoplatin with 5-FU in comparison with conventional cisplatin and 5-FU. This study showed that the pharmacokinetic profile of lipoplatin (in combination with 5-FU) indicates that the liposomal formulation results in a greater and longer body clearance, which may confirm the clinical observation of decreased toxicity, especially renal deterioration [29]. The present study shows that response rate, survival and TTP of patients treated with liposomal cisplatin and paclitaxel are similar to that of those patients treated with cisplatin and paclitaxel. However, the important outcome is that in patients treated with liposomal cisplatin, nephrotoxicity is negligible, as are other adverse reactions such as nausea–vomiting, peripheral neuropathy and asthenia, as shown by the statistical analysis. Lipoplatin has no myelotoxicity [19] and this makes it different from other cisplatin substitutes such as carboplatin [8]. Nephrotoxicity is negligible provided liposomal cisplatin is infused in 1000 ml of 5% dextrose for 8 h, ‘without additional hydration’. The median survival of the patients of both arms was 9 and 10 months, respectively, which is similar to other recent publications with other agent combinations in advanced NSCLC patients [2, 4, 29–34]. The biweekly (every 2 weeks) administration of cisplatin has also been used by other investigators [35–38]. Cisplatin remains a fundamental agent nowadays for the treatment of patients with advanced NSCLC. The present trial has determined that liposomal cisplatin is not superior in efficacy to cisplatin. However, with respect to adverse reactions, lipoplatin is much more well tolerated.

Liposomal cisplatin treatment in combination with paclitaxel in NSCLC overcomes nephrotoxicity, the main adverse reaction of cisplatin, while offering a similar effectiveness to cisplatin with regard to response rate, TTP and OS.

References

- 1.Pfister DG, Johnson DH, Azzoli CG, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology treatment of unresectable non-small-cell lung cancer guidelines: update 2003. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:330–353. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.09.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scaglioti GV, DeMarinis F, Rinaldi M, et al. for the Italian Lung Cancer Project. Phase III randomized trial comparing three platinum-based doublets in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:4285–4291. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.02.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kelly K, Crowley T, Bunn PA, Jr., et al. Randomized phase III trial of paclitaxel plus carboplatin versus vinorelbine plus cisplatin in the treatment of patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a Southwest Oncology Group trial. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:3210–3218. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.13.3210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Le Chevalier T, Scaglioti G, Natale R, et al. Efficacy of gemcitabine plus platinum chemotherapy compared with other platinum containing regimens in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. A meta-analysis of survival outcomes. Lung Cancer. 2005;47:69–80. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2004.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer Collaborative Groups. Chemotherapy in non-small-cell lung cancer: a meta-analysis using updated data on individual patients from 52 randomized clinical trials. BMJ. 1995;311:899–909. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fosella F, Pereira JR, von Pawel J, et al. Randomized, multinational, phase III study of docetaxel plus platinum combinations versus vinorelbine plus cisplatin for advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: the TAX 326 study group. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:3016–3024. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.12.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Greco A, Hainsworth JD. Paclitaxel (1-h infusion) plus carboplatin in the treatment of advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: results of a multicenter phase II trial. Semin Oncol. 1997;24:512–514. S12–S17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chang AY, de Vore R, Johnson D. Pilot study of vinorelbine (navelbine) and paclitaxel in patients with refractory non-small-cell lung cancer. Semin Oncol. 1996;23:S19–S21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Iaffaioli RV, Tortoriello A, Facchini G, et al. Phase I–II study of gemcitabine and carboplatin in stage IIIb–IV non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:921–926. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.3.921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frasci G, Panza N, Comella P, et al. Cisplatin, gemcitabine and paclitaxel in locally advanced or metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer: a phase I–II study. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:2316–2325. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.8.2316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stathopoulos GP, Veslemes M, Georgatou N, et al. Front-line paclitaxel-vinorelbine versus paclitaxel-carboplatin in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a randomized phase III trial. Ann Oncol. 2004;15:1048–1055. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdh260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hanna N, Shepherd FA, Fosella FV, et al. Randomized phase III trial of pemetrexed versus docetaxel in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer previously treated with chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:1589–1597. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.08.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Giaccone G. Twenty-five years of treating advanced NSCLC: what we achieved? Ann Oncol. 2004;15:Siv81–Siv83. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdh908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dimitroulis J, Stathopoulos GP. Evolution of non-small-cell lung cancer chemotherapy (Review) Oncol Rep. 2005;13:923–930. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boulikas T. Low toxicity and anticancer activity of a novel liposomal cisplatin (Lipoplatin) in mouse xenografts. Oncol Rep. 2004;12:3–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Devarajan P, Tarabishi R, Mishra J, et al. Low renal toxicity of lipoplatin compared to cisplatin in animals. Anticancer Res. 2004;24:2193–2200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stahtopoulos GP, Boulikas T, Vougiouka M, et al. Pharmacokinetics and adverse reactions of a new liposomal cisplatin (Lipoplatin phase I study) Oncol Rep. 2005;13:589–595. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boulikas T, Stathopoulos GP, Volakakis N, Vougiouka M. Systemic lipoplatin infusion, results in preferential tumor uptake in human studies. Anticancer Res. 2005;25:3031–3039. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stathopoulos GP, Boulikas T, Vougiouka M, et al. Liposomal cisplatin combined with gemcitabine in pretreated advanced pancreatic cancer patients: a phase I–II study. Oncol Rep. 2005;15:1201–1204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Arienti Ch, Tesei A, Ravaioli A, et al. Activity of lipoplatin in tumor and in normal cells in vitro. Anticancer Drugs. 2008;19(10):983–990. doi: 10.1097/CAD.0b013e3283114fb2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.ICH Efficacy Guidelines EG (R1) Good Clinical Practice Consolidated Guideline. Federal Register September 15, 2003, Vol. 68, No. 178. http://www.ich.org/cache/compo/475-272-1.html (14 April 2010, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stathopoulos GP, Rigatos SK, Pergantas N, et al. Phase II trial of biweekly administration of vinorelbine and gemcitabine in pretreated advanced breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2001;20:37–41. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.1.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kosmas C, Tsavaris N, Syrigos K, et al. A phase I-II study of bi-weekly gemcitabine and irinotecan as second-line chemotherapy in non-small-cell lung cancer after prior taxanes + platinum based regimens. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2006;6:242–245. doi: 10.1007/s00280-006-0242-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Le Chevalier T, Brisgand D, Douillard JY, et al. Randomized study of vinorelbine and cisplatin versus vindesine and cisplatin versus vinorelbine alone in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: results of a European multicenter trial including 612 patients. J Clin Oncol. 1994;12:360–367. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1994.12.2.360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ozer H, Armitage JO, Bennett CL, et al. 2000 update of recommendations for the use of hematopoietic colony-stimulating factors: evidence based, clinical practice guidelines. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:3558–3585. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.20.3558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Therasse P, Arbuck SG, Eisenhower EA, et al. New guidelines to evaluate the response to treatment in solid tumors: European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer, National Cancer Institute of the United States. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:205–216. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.3.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Arbuck SG, Ivy SP, Setser A. The Revised Common Toxicity Criteria: Version 2.0. http://ctep.info.nih.gov (13 April 2010, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jehn CF, Boulikas T, Kourvetaris A, et al. Pharmacokinetics of liposomal cisplatin (lipoplatin) in combination with 5-FU in patients with advanced head and neck cancer: first results of a phase III study. Anticancer Res. 2007;27:471–475. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Scagliotti CV, Parikh P, von Pawel J, et al. Phase III study comparing cisplatin plus gemcitabine with cisplatin plus pemetrexed in chemotherapy-naive patients with advanced-stage non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:3543–3551. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.0375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schiller JH, Harrngton D, Belani CP, et al. Comparison of four chemotherapy regimens for advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:92–98. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sandler A, Gray R, Perry MC, et al. Paclitaxel-carboplatin alone or with bevacizumab for non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:2542–2550. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa061884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stathopoulos GP, Dimitroulis J, Antoniou D, et al. Front-line paclitaxel and irinotecan combination chemotherapy in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a phase I–II trial. Br J Cancer. 2005;93:1106–1111. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Manegold C, Gatzemeier U, von Pawel J, et al. Front-line treatment of advanced non-small-cell lung cancer with MTA (LY231514 pemetrexed disodium, ALIMTA) and cisplatin: a multicenter phase II trial. Ann Oncol. 2000;11:435–440. doi: 10.1023/a:1008336931378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Georgoulias V, Papadakis E, Alexopoulos A, et al. Platinum based and non-platinum-based chemotherapy in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a randomized multicenter trial. Lancet. 2001;357:1478–1484. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04644-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lutz MP, Wilke H, Wagener DJ, et al. Weekly infusional high-dose fluorouracil (HD-FU), HD-FU plus folinic acid (HD-FU/FA), or HD-FU/FA plus biweekly cisplatin in advanced gastric cancer: randomized phase II trial 40953 of the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Gastrointestinal Group and the Arbeitsgemeinschaft Internistische Onkologie. J Clin Oncol. 2008;1:164–169. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.11.1666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen CH, Lin CM, Kao KC, et al. Phase II study of a biweekly regimen of vinorelbine and cisplatin in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Chang Cung Med J. 2007;30:249–255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tas F, Guney N, Derin D, et al. Bi-weekly administration of gemcitabine and cisplatin chemotherapy in patients with anthracycline and taxane-pretreated metastatic breast cancer. Invest New Drugs. 2008;26:363–368. doi: 10.1007/s10637-007-9110-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Heinrish S, Pestalozzi BC, Schafer M, et al. Prospective phase II trial of neoadjuvant chemotherapy with gemcitabine and cisplatin for resectable adenocarcinoma of the pancreatic head. J Clin Oncol. 2008;20:2526–2531. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.5556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]