Abstract

Primary lymphedema is a rare, chronic and distressing condition with negative effects on physical, social and emotional level. The purpose of these reports was to present and discuss two different cases of primary lower limb lymphedema with a focus on its physical and mental impact and on some qualitative aspects of patients' self-reported experiences. The patients were recruited as they used occasional services within the University Hospital of Heraklion (Crete, Greece). The functional and mental impact of primary lymphedema was measured using the generic Medical Outcome Study short form-36 questionnaire and open-ended questions led to give more emphasis to patients' experiences. The analysis of short form-36 results in the first patient disclosed a significant functional impairment with a minor impact of the condition on emotional and social domains. For the second patient quality of life scores in the emotional and social domains were affected. Our findings support further the statement that physicians should pay full attention to appraise the patient's physical and emotional condition. General practitioners have the opportunity to monitor the long-term impact of chronic disorders. Posing simple open-ended questions and assessing the level of physical and mental deficits in terms of well-being through the use of specific metric tools can effectively follow-up rare conditions in the community.

Keywords: lymphedema, diagnosis, quality of life, primary health care

Introduction

Lymphedema is defined as an excessive lymphatic fluid accumulation in subcutaneous tissues, due to inability of the lymphatic system to maintain normal tissue homeostasis 1. It may be classified as primary or secondary 1. Primary lymphedema results from congenital abnormality or dysfunction of the lymphatic vessels 2. Secondary lymphedema which is more common than the primary form can develop as a consequence of distruction or obstruction of lymphatic channels by other pathological conditions such as infection, trauma or malignancy 1. The most common cause of secondary lymphedema worldwide is filariasis, an infestation of the lymph nodes by the parasite Wuchereria bancrofti 2.

Primary lymphedema is a rare condition that affects approximatelly 1/100.000 persons less than 20 years old with preponderance in female gender 3. There are three subtypes of primary lymphedema: congenital lymphedema, which is detected at birth or in the first year of life; lymphedema praecox which has its onset at the time of puberty 4; and lymphedema tarda, which ussualy occurs after the age of 35 years old 2.

Lymphedema is a chronic, unremitting and potentially disabling condition leading to a long-term burden for the patient's life in terms of physical, social and emotional level 5. It has been reported that patients with lymphedema exhibit an excess of psychological sequelae and poor levels of psychosocial adaptation comparative to the general population 6. There is limited information about psychological distress that patients with lymphedema meet, thus we found interesting to review known cases of lymphedema in the island of Crete.

These reports focus on two cases of primary lower limb lymphedema, by discussing the overall physical and mental impact of primary lymphedema through the use of metric tools of health related quality of life domains and highlighting some qualitative aspects of patients' self-reported experiences.

Case presentation

The patients were recruited from the first author (EKS) as they used occasional services within the University Hospital of Heraklion in a four year period. They reported a medical history of primary lower limb lymphedema diagnosis by specialists and all accepted to participate in this study when they were asked. Patient's health status was measured using the generic Medical Outcome Study (MOS) short form-36 questionnaire (SF-36) 7, translated and validated in Greek language 8. It is a self-administered questionnaire that comprises 8 domains of quality of life: physical functioning, role physical, role emotional, bodily pain, vitality, mental health, social functioning, and general health. SF-36 metric patterns of the two patients were registered and are shown in Table 1 and a description of these two cases follows below

Table 1.

SF-36 Scale Scores (score range: 0-100)

| SF-36 scale domains | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical Functioning | Role Physical | Bodily Pain | General Health | Vitality | Social Functioning | Role Emotional | Mental Health | |

| Case 1 | 20 | 50 | 51 | 35 | 70 | 100 | 100 | 60 |

| Case 2 | 65 | 25 | 74 | 10 | 75 | 50 | 33.3 | 72 |

100: Best Health

0: Poorest Health

Case 1

A 53-years old man presented with a history of chronic left lower limb edema. The swelling was initially presented at the age of 8 years from the left ankle progressing slowly up to the calf, thigh and inguinal area leading to disfigurement and functional impairment. The patient had a negative family history of edema. He received a diagnosis of primary lymphedema at the age of 13 years. Since then he was recommended to follow a conservative management with elevation of the extremity, elastic stockings, physical activity and avoidance of trauma. Currently, he reports at least two episodes of cellulitis annually.

Physical examination revealed an erythematous non-pitting edema extended from groin to foot. The temperature of the involved extremity was normal. Circumferential measurements in centimeters were accomplished on bilateral lower extremities at the level of ankle, calf, mid-thigh and inguinal area: ankle: [32cm (left), 22cm (right)], calf: [51cm (left), 40cm (right)], left mid-thigh: [70cm (left), 59 cm (right)], left inguinal area: [73cm (left) and 62cm (right)], (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Left lower limb lymphedema in a 53-year old man.

During the medical interview on family issues, the patient commented: “I did not think to have children that may suffer from the same problem”, and when information on his professional status was asked he added: “I could not spend too much time standing up and I lost my job”.

Case 2

A 33-years old woman during the first trimester of gestation (2 years ago) described a progressive painless enlargement on the left ankle, proximally extended, leading to impaired daily activity and creating a sensation of heaviness and discomfort. There was no family history of similar disorders. A conventional approach was applied, involving elevation of the affected limb, massage, physical activity and compression with elastic stockings.

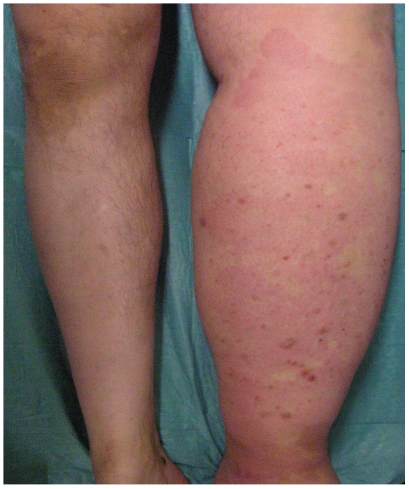

On physical examination she presented a non-pitting, non-erythematous edema extended from the ankle to the groin without signs of inflammation (Figure 2). Circumferential measurements of the legs in centimeters were: ankle: [33cm (left), 25cm (right)], calf: [50cm (left), 37cm (right)], mid thigh: [63cm (left), 56cm (right)], and inginal area: [66cm (left), 59cm (right)]. The remainder of the physical examination was unremarkable.

Figure 2.

Left lower limb lymphedema in a 33-year old female.

It is noteworthy that daily life issues represented sources of embarrassment leading to some social isolation: “I felt so embarrassed when a shop employee told me: Can I ask you what happened to your leg?” The patient added: “I did not go shopping anymore!”

Discussion

In the first case the analysis of SF-36 results disclosed a significant functional impairment with a slight impact of the condition on emotional and social domains (Table 1). A possible explanation could be the chronicity of the disorder. Based on our observation, it seems that the long time passed from the moment of the diagnosis may have offered the first patient the chance to cope better with the psychological aspects of his condition over time. In the past, the burden of the problem was considerable as the disorder conditioned patient's perceptions in family planning and had a negative impact on his employment status.

Another important issue is that due to some physicians' limited awareness the patient suffered his condition for a long time without a diagnosis. According to the patient some of the involved physicians paid limited attention to his disorder. In a study that described characteristics of lymphedema referrals, approximately 7 out of 10 patients with primary lymphedema, suffered their condition, on average, for at least 5 years 9. The late referral was considered an important cause of ineffective management for these patients 9.

In the second patient, domains of physical role, general health, social functioning and emotional role had gained a lower scoring (Table 1).

In this study, it seems that features such as severity of lower limb lymphedema cannot predict a 'linear effect' on emotional well-being. In alignment with this, previous research efforts showed that there is no linear relationship between the change of the limb volume and psycho-social morbidity 10. Furthermore it is not clear to what extent factors such as sex, socio-cultural or family status influenced personal views of the patients involved. Factors that have been associated with increased psychological distress and sexual dysfunction in patients with lymphedema were low levels of social support 10. It was surmised that social support may help combat fears of abandonment and feelings of isolation 10.

The psychosocial impact of lymphedema seems to be neglected by the health care providers 5. It has been reported that only 3% of patients with lymphedema received psychological support as a treatment approach 5. It is also noteworthy that in a study among primary health care teams only 4 out of 10 physicians were aware about the presence of an effective treatment for lower limb lymphedema 11. Nevertheless, lymphedema specialists such as vascular surgeons are more familiar with the management of the disorder in the acute phase. Although the disease is rare, primary care physicians as first contact care givers and through the continuity of care that they can offer, may play an important role in the diagnosis and the monitoring of the long-term impact of lymphedema on physical and emotional or social domains. The SF-36 seems to be a suitable tool for the assessment of quality of life in patients with lower limb lymphedema 12. It could represent a useful long term monitoring tool that evaluates the course of lymphedema impact on patients' functional and emotional well-being.

There is limited evidence about the optimal treatment approach of patients with lymphedema 5, 13. Working with an interdisciplinary team has been reported to be an important issue in the patient's adherence to lymphedema treatment 13. It is also remarkable that, in a recent report discussing the genetic inheritance pattern of congenital primary lymphedema, genetic assessment and molecular investigation have been considered that contribute significantly to a proper counseling process to the families with a confirmed disease background 14. Furthermore, it is reported that a close collaboration among health professionals, with a high level of awareness, from geneticists, neonatologists, pediatricians to dermatologists, may represent an essential issue for an optimal overall management of cases with a congenital primary lymphedema 14.

Conclusions

Assessing the impact of the duration and severity of the condition in relation to age, sex and occupational status as influential determinants to personal perceptions of well-being deserves further discussion. General practitioners can monitor the long-term impact of chronic disorders through their daily practice. Posing simple open-ended questions, allowing patients to talk about their conditions and using generic metric tools for the assessment of physical and mental deficits represent both approaches that in conjunction can effectively follow-up rare, and commonly related to poor care provision, disorders.

The SF-36 findings highlight the necessity of additional research efforts that promote the implementation of a more holistic care approach for patients with primary lymphedema, the same as in other chronic illnesses and conditions. Assessing not only the severity of the physical limitation but also the related psychosocial dimensions and quantifying the burden of this complex condition over time could contribute to tailor fitted interventions.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the researchers who translated and validated the SF-36 questionnaire into Greek for offering information on technical details.

Written informed consent was obtained from the patients for publication of these case reports and any accompanying images.

References

- 1.Rockson SG. Lymphedema. Am J Med. 2001;110:288–95. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(00)00727-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tiwari A, Cheng KS, Button M, Myint F, Hamilton G. Differential diagnosis, investigation, and current treatment of lower limb lymphedema. Arch Surg. 2003;138:152–61. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.138.2.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smeltzer DM, Stickler GB, Schirger A. Primary lymphedema in children and adolescents: a follow-up study and review. Pediatrics. 1985;76:206–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rizzo C, Gruson LM, Wainwright BD. Lymphedema praecox. Dermatol Online J. 2009;15:7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moffatt CJ, Franks PJ, Doherty DC, Williams AF, Badger C, Jeffs E, Bosanquet N, Mortimer PS. Lymphedema: an underestimated health problem. QJM. 2003;96:731–8. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcg126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Godoy JM, de Godoy Mde F. Godoy & Godoy technique in the treatment of lymphedema for under-privileged populations. Int J Med Sci. 2010;7:68–71. doi: 10.7150/ijms.7.68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ware JE Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30:473–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pappa E, Kontodimopoulos N, Niakas D. Validating and norming of the Greek SF-36 Health Survey. Qual Life Res. 2005;14:1433–8. doi: 10.1007/s11136-004-6014-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sitzia J, Woods M, Hine P, Williams A, Eaton K, Green G. Characteristics of new referrals to twenty-seven lymphedema treatment units. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 1998;7:255–62. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2354.1998.00112.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Passik SD, McDonald MV. Psychosocial aspects of upper extremity lymphedema in women treated for breast carcinoma. Cancer. 1998;83:2817–20. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19981215)83:12b+<2817::aid-cncr32>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Logan V, Barclay S, Caan W, McCabe J, Reid M. Knowledge of lymphoedema among primary health care teams: a questionnaire survey. Br J Gen Pract. 1996;46:607–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Franks PJ, Moffatt CJ, Doherty DC, Williams AF, Jeffs E, Mortimer PS. Assessment of health related quality of life in patients with lymphedema of the lower limb. Wound Repair Regen. 2006;14:110–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2006.00099.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pereira de Godoy JM, Braile DM, de Fátima Godoy M, Longo OJr. Quality of life and peripheral lymphedema. Lymphology. 2002;35:72–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kitsiou-Tzeli S, Vrettou C, Leze E, Makrythanasis P, Kanavakis E, Willems P. Milroy's primary congenital lymphedema in a male infant and review of the literature. In Vivo. 2010;3:309–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]