Abstract

The RhlR transcriptional regulator of Pseudomonas aeruginosa, along with its cognate autoinducer, N-butyryl homoserine lactone (C4-HSL), regulates gene expression in response to cell density. With an Escherichia coli LexA-based protein interaction system, we demonstrated that RhlR multimerized and that the degree of multimerization was dependent on the C4-HSL concentration. Studies with an E. coli lasB::lacZ lysogen demonstrated that RhlR multimerization was necessary for it to function as a transcriptional activator. Deletion analysis of RhlR indicated that the N-terminal domain of the protein is necessary for C4-HSL binding. Single amino acid substitutions in the C-terminal domain of RhlR generated mutant RhlR proteins that had the ability to bind C4-HSL and multimerize but were unable to activate lasB expression, demonstrating that the C-terminal domain is important for target gene activation. Single amino acid substitutions in both the N-terminal and C-terminal domains of RhlR demonstrated that both domains possess residues involved in multimerization. RhlR with a C-terminal deletion and an RhlR site-specific mutant form that possessed multimerization but not transcriptional activation capabilities were able to inhibit the ability of wild-type RhlR to activate rhlA expression in P. aeruginosa. We conclude that C4-HSL binding is necessary for RhlR multimerization and that RhlR functions as a multimer in P. aeruginosa.

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a versatile bacterium that inhabits ecological niches ranging from soil to water to plants (11). It is also an opportunistic pathogen of humans, infecting primarily the immunocompromised, including cystic fibrosis patients (8). The expression of many P. aeruginosa virulence factors is controlled by a regulatory mechanism known as quorum sensing (23). Quorum sensing is a form of intercellular communication whereby bacteria coordinately regulate target gene expression in response to cell density. The two main quorum-sensing systems of P. aeruginosa are the las and the rhl systems. These systems are composed of transcriptional regulator proteins, LasR and RhlR, and their cognate autoinducer synthases, LasI and RhlI. LasI directs the synthesis of N-3-oxododecanoyl-l-homoserine lactone (3O-C12-HSL), and RhlI directs the synthesis of N-butyryl homoserine lactone (C4-HSL). When a threshold autoinducer concentration is reached inside the cell, the autoinducer forms a complex with its cognate transcriptional regulator protein and the transcriptional regulator-autoinducer complex controls gene expression, presumably by binding to DNA elements with conserved dyad symmetry (las boxes) upstream of quorum-sensing-activated target genes (6). With DNA microarrays, it has recently been demonstrated that the las and rhl quorum-sensing systems can both activate and repress the expression of genes falling into a wide range of functional classes (virulence, motility, metabolism, etc.) (26, 32). It is thought that many of the activated and repressed genes are indirectly regulated by quorum sensing as they do not possess las boxes upstream of their transcriptional start sites (26, 32). Through examination of the P. aeruginosa genome, a third transcriptional regulator, QscR, with homology to both LasR and RhlR has recently been identified (4). QscR has been shown to negatively regulate the expression of quorum-sensing-controlled genes (4, 17).

Quorum-sensing transcriptional regulators have been identified in various species throughout the class Proteobacteria (9). LuxR, the transcriptional regulator of Vibrio fischeri, is the prototype member of this family; and genetic analyses have defined the functional regions of this protein. The N-terminal two-thirds of LuxR binds its autoinducer (10), and the C-terminal one-third of LuxR contains a helix-turn-helix motif that binds DNA and activates target gene expression (3). It was postulated that LuxR functions as a multimer as overexpression of the N-terminal domain inhibits the activity of the wild-type protein (2).

Molecular genetic and biochemical studies have demonstrated that P. aeruginosa LasR, RhlR, and QscR; Agrobacterium tumefaciens TraR; and Erwinia carotovora CarR form multimers. However, the mechanism of multimerization varies among the transcriptional regulator homologs. LasR requires its autoinducer for multimerization, and this multimerization correlates with its capacity to activate target gene expression (15). In addition, an N-terminal domain fragment of LasR inhibits the activity of wild-type LasR in vivo (15). TraR was recently crystallized as a complex with its cognate autoinducer and its DNA-binding site (30, 34). The crystal structures are the first obtained for a quorum-sensing transcriptional regulator, and they display TraR as a dimer with the N-terminal domain of each monomer binding to its autoinducer and the C-terminal domain of each monomer binding to DNA. The N- and C-terminal domains are connected by a linker (12 to 13 amino acid residues), and both domains participate in protein dimerization (30, 34). Previous work by Zhu and Winans demonstrated that apo-TraR is unstable and that TraR's cognate autoinducer, N-(3-oxo-octanoyl)-l-homoserine lactone, stabilizes nascent TraR for folding into its mature tertiary structure (35). In contrast, a recent genetic analysis of TraR demonstrated that the binding of TraR to its cognate autoinducer drives protein dimerization (19). While CarR also binds its autoinducer, like other members of this protein family, CarR exists as a preformed dimer and autoinducer binding causes the dimers to form higher-order multimers (33). Through fluorescence anisotropy and in vivo chemical cross-linking, two recent reports suggested that RhlR and QscR function similarly to CarR. The reports showed that RhlR forms a homodimer in the absence of C4-HSL and that QscR forms a multimer in the absence of either C4-HSL or 3O-C12-HSL (17, 31). They further demonstrated that while C4-HSL has no effect on the RhlR homodimers, 3O-C12-HSL could dissociate the homodimers into monomers (31). To gain a better understanding of the functional mechanism of the RhlR transcriptional regulator, this study analyzed RhlR with regard to protein multimerization, target gene activation, and C4-HSL binding. Through a series of deletions and site-specific mutations of conserved amino acid residues, critical functional regions of the protein were defined.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and plasmids.

Escherichia coli strains were grown at 37°C in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium, and P. aeruginosa strains were grown at 37°C in PTSB medium (21). Antibiotics were used at the following concentrations when needed: for E. coli, tetracycline (TET) at 12 μg/ml and ampicillin (AMP) at 100 μg/ml; for P. aeruginosa, carbenicillin (CARB) at 200 μg/ml. E. coli SU101 (7) carrying a chromosomally integrated sulA::lacZ fusion was used for the multimerization studies, and the E. coli MG4 λB21P1 lasB::lacZ lysogen (27) was used for the transcriptional activation studies. Wild-type P. aeruginosa PAO220 (13) carrying an rhlA::lacZ transcriptional fusion (a generous gift of Herbert Schweizer) was used to determine if RhlR functions as a multimer in P. aeruginosa.

DNA techniques.

Plasmid DNA was purified by the Spin Mini Kit or Plasmid Mini Kit protocol (QIAGEN, Valencia, Calif.). E. coli DH5α was used as the host strain for molecular cloning. E. coli was transformed (25), and P. aeruginosa was electroporated (28), as previously described. Restriction endonucleases and DNA-modifying enzymes were obtained from Invitrogen Life Technologies (Carlsbad, Calif.) and New England Biolabs (Beverly, Mass.). Oligonucleotide synthesis and DNA sequencing were performed by the Core Nucleic Acid Facility of the Functional Genomics Center at the University of Rochester. PCR was performed with Vent DNA polymerase (New England Biolabs) or an Expand Long Template PCR system (Boehringer Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany) in accordance with the manufacturer's specifications.

Generation of LexA(DBD)-RhlR fusion plasmids.

The rhlR gene of P. aeruginosa was PCR amplified from plasmid pJPP12 (pBS SK− containing rhlABRI′ from PAO1, a generous gift of Jim Pearson) and fused in frame with the DNA-binding domain (DBD) of LexA, which is expressed from the lacUV5 promoter of plasmid pSR658 (5). The sense primer contained a unique XhoI restriction site to facilitate the generation of the translational fusion, and the antisense primer contained a unique PstI site.

Plasmids with 5′ and 3′ DNA deletions of rhlR were generated by PCR with plasmid pJPP12 as the template. For generation of the N-terminal rhlR deletions, the sense primers contained a unique XhoI restriction site, the DNA sequence corresponding to the first three amino acids of the rhlR gene, and an 18- to 21-bp annealing region homologous to the internal coding region of rhlR. For generation of the C-terminal rhlR deletion, the antisense primer contained a unique PstI site, the DNA sequence of the last three amino acids of the rhlR gene, and a 15-bp annealing region homologous to the internal coding region of rhlR. The antisense primer used in the generation of the N-terminal deletions and the sense primer used in the generation of the C-terminal deletion were the same as those used in the generation of the original LexA(DBD)-RhlR fusion. All PCR products were digested with XhoI and PstI, fused in frame with the LexA DBD of plasmid pSR658, and verified by sequencing. The five N-terminal deletions of RhlR coding for truncated proteins were Δ4-25, Δ4-66, Δ4-82, Δ4-117, and Δ4-161, and the C-terminal deletion of RhlR coding for a truncated protein was Δ179-239.

Nine site-specific mutations of the rhlR gene were generated with a recombination PCR-based protocol (14). The rhlR gene was first cloned from plasmid pSR658 into XhoI/PstI-digested pBS SK− (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.). Briefly, the mutagenic primers consisted of 4 to 6 bp of homologous sequence at the 5′ end, followed by one mutagenic nucleotide and 18 to 20 bp of homologous sequence at the 3′ end. The nonmutagenic primers were homologous to the pBS SK− coding sequence. Complementary PCR fragments were purified and used to transform E. coli XL1-Blue cells. The entire rhlR gene of the transformants was sequenced to verify that only the intended mutation, and no secondary mutations, was generated. The mutated rhlR genes were then cloned into XhoI/PstI-digested pSR658 to generate translational fusions with the LexA DBD. The mutations introduced into RhlR were Asp-12-Glu, Ala-44-Gly, Asp-81-Glu, Ser-135-Thr, Leu-162-Val, Leu-181-Val, Lys-196-Arg, Th-211-Ser, and Lys-222-Arg.

Generation of antibodies to RhlR.

For production of RhlR protein for immunization, E. coli DH5α(pJPP8) (pEX1.8 containing Ptac-rhlR)(22) was grown overnight at 37°C in LB medium containing AMP at 100 μg/ml and subcultured to a starting optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.05 in 2 liters of the same medium. The culture was incubated with shaking at 37°C for 3.5 h. Isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) was added to a final concentration of 1 mM, and the culture was incubated for an additional hour. Following centrifugation of the culture at 14,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C, the supernatant was decanted and the resulting pellet was resuspended in 30 ml of TES buffer (50 mM Tris HCl, 1 mM EDTA, 100 mM NaCl) (12) with phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF) at 1 μg/ml. This solution was French pressed at 18,000 lb/in2 and centrifuged at 17,000 × g for 20 min, and the resulting pellet was resuspended in TES-PMSF buffer (12). The French pressing and centrifugation were repeated, and the resulting cell pellet was frozen at −70°C. The procedure was repeated on a smaller scale (500 ml) with a culture of E. coli DH5α(pEX1.8) (pEX1 containing a P. aeruginosa origin of replication) (22) for use as a negative control. Cell pellets were resuspended in 4 ml of 1× sample buffer (25). Equivalent samples of pressed E. coli DH5α(pJPP8) and E. coli DH5α(pEX1.8) were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE), and proteins were visualized with rapid Coomassie stain (25). Protein with the approximate molecular mass of RhlR (28 kDa) was excised from the gel and frozen at −70°C. Gel fragments were resuspended in incomplete Freund's adjuvant (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) and injected into four female BALB/c mice 6 to 8 weeks old. Injections of antigen were given every 2 weeks. Generation of specific antibodies to RhlR was tested by Western analysis. Serum samples from a preinoculation bleeding of BALB/c mice were used as controls. Briefly, whole-cell lysates of E. coli DH5α(pEX1.8) and DH5α(pJPP8) prepared as described above were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to PROTRAN nitrocellulose (Schleicher & Schuell, Inc., Keene, N.H.). Membranes were blocked in Immuno Buffer (IB; 50 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 0.05% Tween 20, 0.01% SDS) containing 5% nonfat dry milk. All washes were done with IB. Primary antibody was diluted 1/2,000 in IB, and peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse secondary antibody (Kirkegaard & Perry Laboratories, Gaithersburg, Md.) was diluted 1/10,000 in IB. Specific binding was visualized with the LumiGLO chemiluminescent substrate system (Kirkegaard & Perry Laboratories). The membranes were exposed to X-ray film (X-Omat; Eastman Kodak Company, Rochester, N.Y.). No reactivity was seen with the preimmune serum. For the anti-RhlR antibodies, a band of the expected size (28 kDa) was present only in the pJPP8 sample and not in the pEX1.8 negative control.

Stability of RhlR in the presence and absence of C4-HSL.

E. coli DH5α(pJPP8) and E. coli DH5α(pSR658-lexA[DBD]-rhlR) were grown overnight in LB medium at 37°C with the appropriate antibiotic (either AMP at 100 μg/ml or TET at 12 μg/ml) and subcultured to a starting OD600 of 0.05 in the same medium. When an OD600 of 0.5 was reached, IPTG was added to a final concentration of 1 mM in the presence and absence of 50 μM C4-HSL. Growth was continued at 37°C for an additional 2 h. Pellets were resuspended in 1× sample buffer (25). Protein separation by SDS-PAGE, Western analysis, and specific binding were performed as described above. The primary antibody for the blots containing the LexA(DBD)-RhlR protein samples was rabbit polyclonal anti-LexA (Invitrogen), and the secondary antibody was peroxidase-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit (Amersham, Piscataway, N.J.).

RhlR multimerization assays.

Multimerization of wild-type LexA(DBD)-RhlR and the LexA(DBD)-RhlR mutant forms was assayed with a LexA-based protein interaction system (7). The pSR658-lexA(DBD)-rhlR plasmid constructs were electroporated into E. coli SU101 carrying a sulA::lacZ fusion. The transformants were grown overnight in LB medium containing TET at 12 μg/ml and subcultured to a starting OD600 of 0.05 in LB medium containing TET at 12 μg/ml and 1 mM IPTG in the presence and absence of 50 μM C4-HSL. The cultures were grown to an OD600 of ∼0.8, and β-galactosidase activity was assayed as previously described (20).

RhlR transcriptional activation assays.

To determine if the pSR658-lexA(DBD)-rhlR plasmid constructs were able to activate target gene expression, they were transformed into E. coli MG4 carrying a lasB::lacZ fusion. The transformants were grown overnight in LB medium containing TET at 12 μg/ml and subcultured to a starting OD600 of 0.05 in LB medium containing TET at 12 μg/ml and 1 mM IPTG in the presence and absence of 50 μM C4-HSL. The cultures were grown to an OD600 of ∼1.0, and β-galactosidase activity was assayed as previously described (20).

Statistical analysis.

For the multimerization and transcriptional activation studies, two to four independent assays were performed with triplicate samples. Data were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance with a post-hoc Tukey test to determine statistical significance (P ≤ 0.05).

Inhibition of wild-type RhlR in P. aeruginosa.

pSR658-lexA(DBD)-rhlR Δ179-239 and pSR658-lexA(DBD)-rhlR Thr-211-Ser were digested with XhoI and KpnI, the ends were made flush with Klenow, and then both were redigested with PstI. Purified fragments were ligated to SmaI/PstI-digested pEX1.8 (22), placing the rhlR constructs under the control of the tac promoter. pEX1.8, pEX1.8 RhlR Δ179-239, and pEX1.8 RhlR Thr-211-Ser were electroporated into PAO220 (13). PAO220 carrying the plasmid constructs was grown overnight in PTSB medium containing CARB at 200 μg/ml and subcultured to a starting OD660 of 0.05 in PTSB medium containing CARB at 200 μg/ml in the presence of 1 mM IPTG. When appropriate, 2 or 10 μM C4-HSL was added to the cultures. The cultures were grown to an OD660 of ∼1.0, and β-galactosidase activity was assayed as previously described (20).

[3H]C4-HSL-binding assays.

E. coli DH5α carrying the pSR658-lexA(DBD)-rhlR plasmid constructs was grown overnight at 37°C in LB medium containing TET at 12 μg/ml and subcultured to a starting OD600 of 0.05 in the same medium. When an OD600 of 0.5 was reached, IPTG was added to a final concentration of 1 mM and growth was continued at 37°C for an additional 2 h. Approximately 0.2 μM [3H]C4-HSL (purified as described in reference 22) was added to 1 ml of culture, and [3H]C4-HSL binding was assayed as previously described (22).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

C4-HSL is necessary for RhlR multimerization and activity.

To examine the functional domains of RhR, we used a LexA-based protein interaction system (7). LexA is composed of an N-terminal DBD and a C-terminal dimerization domain. For these studies, the C-terminal dimerization domain of LexA was replaced with a wild-type or mutated rhlR gene, generating a hybrid LexA(DBD)-RhlR fusion protein. For the multimerization studies, the LexA(DBD)-RhlR fusion proteins were introduced into E. coli SU101 (7), a reporter strain containing a dyad symmetrical operator sequence that controls expression of a sulA::lacZ fusion carried as a lambda lysogen. Multimerization of RhlR allows the LexA-DBD to bind the sulA operator and efficiently repress expression of lacZ, which is monitored by β-galactosidase activity.

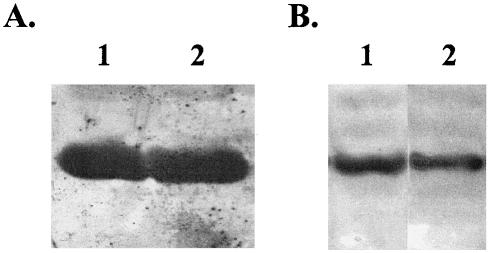

Zhu and Winans have previously demonstrated that apo-TraR is unstable in the absence of its cognate autoinducer (35). Therefore, we first determined if RhlR is stable in E. coli in the absence of C4-HSL (Fig. 1A). Western analysis with anti-RhlR antibodies was performed on whole-cell lysates of E. coli DH5α(pJPP8) (22) grown in the absence and presence of C4-HSL. A band of the expected size (28 kDa) was present to roughly the same level in both the absence (lane 1) and presence (lane 2) samples, indicating that C4-HSL is not necessary for the stabilization of RhlR in E. coli. We also determined if the LexA(DBD)-RhlR fusion is stable in the presence and absence of C4-HSL (Fig. 1B). Western analysis with anti-LexA antibodies was performed on whole-cell lysates of E. coli DH5α(pSR658-lexA[DBD]-rhlR) grown in the absence and presence of C4-HSL. Again, a band of the expected size (36 kDa) was present to roughly the same level in both the uninduced (lane 1) and induced (lane 2) samples, indicating that C4-HSL is not necessary for stabilization of the LexA(DBD)-RhlR fusion in E. coli. These results indicated that, unlike TraR (35), apo-RhlR is stable in the absence of its cognate autoinducer, C4-HSL.

FIG. 1.

Stability of RhlR in the absence and presence of C4-HSL. Equivalent samples of whole-cell lysates of E. coli DH5α(pJPP8) (A) and E. coli DH5α(pSR658-lexA[DBD]-rhlR) (B) grown in the absence (lane 1) and presence (lane 2) of 50 μM C4-HSL were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by immunoblotting with either anti-RhlR (A) or anti-LexA (B) antibodies.

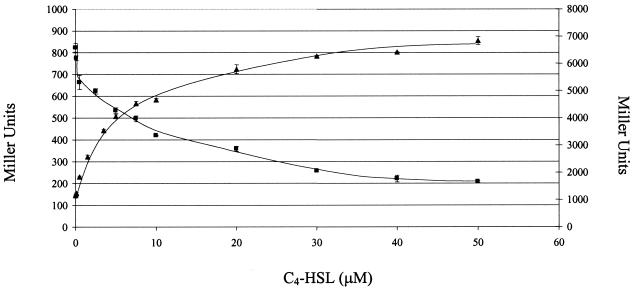

Pearson et al. have previously shown that expression of an rhlA::lacZ fusion in E. coli carrying RhlR increases with increasing concentrations of C4-HSL and that a higher concentration of C4-HSL is necessary for activation of rhlA in E. coli than in P. aeruginosa (22). The decreased sensitivity of E. coli to C4-HSL may be due to decreased uptake or stability of C4-HSL in E. coli or the difference in transcriptional and translational factors between E. coli and P. aeruginosa (22). We, therefore first performed the multimerization assay in the presence of different C4-HSL concentrations. E. coli SU101 carrying pSR658-lexA(DBD)-rhlR fusion was grown in the presence of C4-HSL concentrations ranging from 0 to 50 μM, and β-galactosidase activity was quantified (Fig. 2). In the absence of C4-HSL, the LexA(DBD)-RhlR fusion protein generated β-galactosidase activity similar to that obtained with the pSR658 vector control (approximately 6,800 Miller units), and no statistically significant difference was observed for the pSR658 vector control grown with no autoinducer or with 50 μM C4-HSL (data not shown). The LexA(DBD)-RhlR fusion protein showed increased multimerization (a decrease in the number of Miller units) with increasing concentrations of C4-HSL. These results indicated that RhlR multimerized and that its multimerization was dependent on the C4-HSL concentration.

FIG. 2.

Multimerization and activation of LexA(DBD)-RhlR are dependent on C4-HSL. E. coli SU101 (▪) and an E. coli MG4 lasB::lacZ lysogen (▴) expressing the full-length LexA(DBD)-RhlR fusion protein were grown in the presence of 0 to 50 μM C4-HSL. For E. coli SU101, multimerization is indicated by a decrease in the number of Miller units (right y axis), and for the E. coli MG4 lasB::lacZ lysogen, activity is indicated by an increase in the number of Miller units (left y axis). Representative results from one independent assay are presented as the average of triplicates plus and minus the standard error of the mean.

In a previous study, RhlR was demonstrated to homodimerize in the absence of C4-HSL, and addition of C4-HSL had no effect on the homodimers (31). These results are the opposite of what we conclude here. Our results indicate that, similar to LasR and TraR, RhlR forms multimers only in the presence of its cognate autoinducer, C4-HSL (15, 19). Both the study of Ventre et al. (31) and the present study used N-terminal translational protein fusions, and both were performed in E. coli backgrounds. As has been previously hypothesized for LuxR (2), a possible explanation for the discrepancy between the experimental results obtained is that in the study by Ventre et al., RhlR might have been able to form multimers in the absence of C4-HSL when a high concentration of protein was expressed in E. coli (31). In addition, Ventre et al. only used 1 μM C4-HSL in their E. coli experiments (31), which, while sufficient to activate RhlR in P. aeruginosa, has been previously reported (22) and also shown in this study to have little effect on RhlR activity in E. coli.

It was next determined if RhlR multimerization is necessary for it to transcriptionally activate gene expression. For the activation studies, the pSR658-lexA(DBD)-rhlR plasmid was introduced into E. coli MG4 carrying a lasB::lacZ lysogen. It has previously been demonstrated that RhlR is an activator of lasB in P. aeruginosa and E. coli (1, 22). The transcriptional activation of lasB can be seen as an increase in β-galactosidase activity. The E. coli MG4 lasB::lacZ lysogen (27) carrying the pSR658-lexA(DBD)-rhlR plasmid was grown in the presence of C4-HSL concentrations ranging from 0 to 50 μM, and β-galactosidase activity was quantified (Fig. 2). In the absence of C4-HSL, the LexA(DBD)-RhlR fusion protein generated β-galactosidase activity similar to that obtained with the pSR658 vector control (data not shown), and the LexA(DBD)-RhlR fusion protein showed increasing activity (an increase in the number of Miller units) with increasing concentrations of C4-HSL. These results indicated that the protein transcriptional activity of lasB by LexA(DBD)-RhlR was also dependent on the C4-HSL concentration. The RhlR multimerization and transcriptional activation results are consistent with previously reported data that show a requirement for C4-HSL and a positive correlation between the concentration of C4-HSL and the ability of RhlR to act as a transcriptional activator (22). These results are different from those of the earlier study by Ventre et al.; however, they did not perform any RhlR transcriptional activation studies (31). The C4-HSL concentration necessary for both half-maximal multimerization and half-maximal activity was approximately 3 μM, and no significant difference in multimerization or transcriptional activity was observed at concentrations above 40 μM. Throughout the remainder of the study, all of the multimerization and transcriptional activation assays were performed in the absence or presence of 50 μM C4-HSL, which provided an autoinducer excess.

The P. aeruginosa LasR transcriptional regulator multimerizes in the presence of 3O-C12-HSL (15), and Pesci et al. have shown that 3O-C12-HSL inhibits C4-HSL from binding to RhlR (24). To determine if full-length RhlR would multimerize in the presence of 3O-C12-HSL or only in the presence of its cognate autoinducer, C4-HSL, the LexA(DBD)-RhlR multimerization assay was also performed in the absence and presence of 50 μM 3O-C12-HSL. Inclusion of 50 μM 3O-C12-HSL did not result in multimerization, indicating that RhlR multimerization was specific for C4-HSL (data not shown).

Domains of RhlR necessary for multimerization and transcriptional activity.

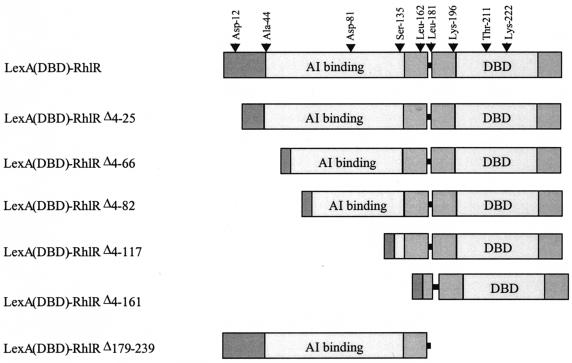

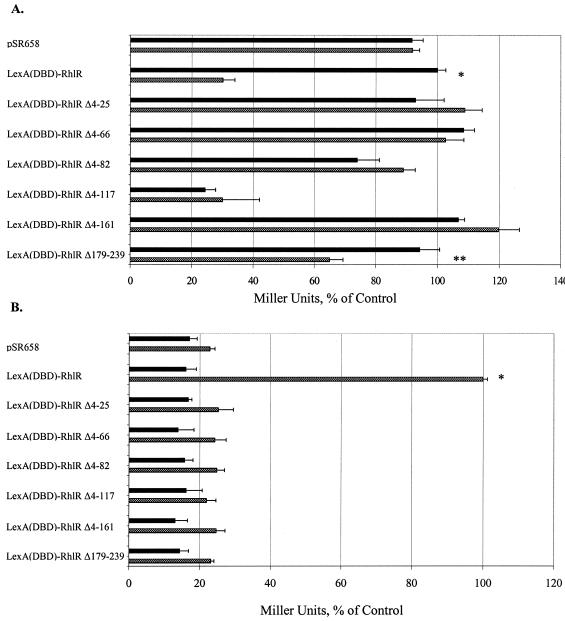

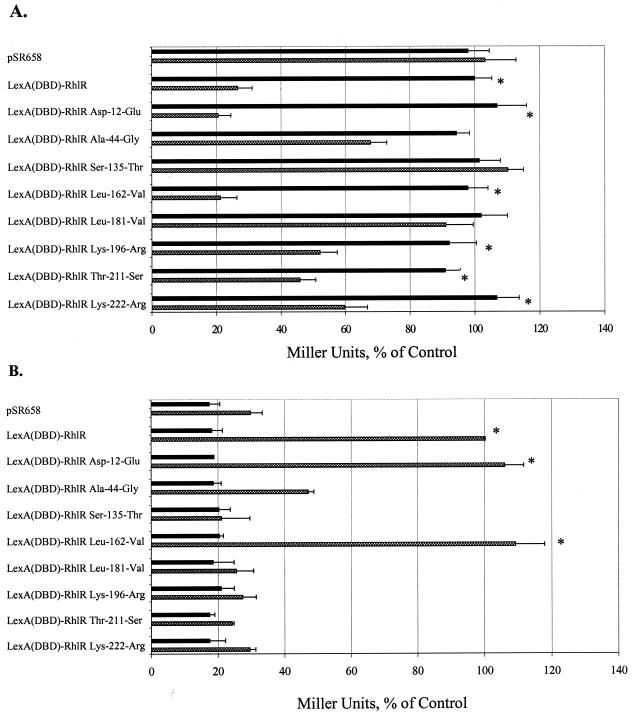

To determine the regions of RhlR necessary for it to multimerize and transcriptionally activate lasB, six truncated forms of RhlR were generated (Fig. 3) and assessed for their multimerization and transcriptional activation abilities (Fig. 4A and B). Five of the deletions were at the N-terminal end of the protein [LexA(DBD)-RhlR Δ4-25, Δ4-66, Δ4-81, Δ4-117, and Δ4-161], and one of the deletions was at the C-terminal end of the protein [LexA(DBD)-RhlR Δ179-239]. Western analysis with polyclonal anti-LexA antibodies indicated that all of the truncated forms of RhlR were stable in E. coli in the presence of 50 μM C4-HSL to roughly the same level (data not shown). As previously demonstrated (Fig. 2), the LexA(DBD)-RhlR fusion protein multimerized and possessed transcriptional activity in the presence of 50 μM C4-HSL. The LexA(DBD)-RhlR deletion results indicated that RhlR Δ4-117 multimerized independently of C4-HSL and that RhlR Δ179-239 demonstrated impaired multimerization in a C4-HSL-dependent manner. The P value for the difference between the uninduced and induced samples of the Δ179-239 deletion form of RhlR was ≤0.1. Taking into account all of the data that will be presented on this C-terminal truncated form of RhlR, including the finding that it is multimerization and activity of native RhlR, this partial multimerization is most likely significant. The remaining truncated forms of RhlR were unable to multimerize regardless of the presence of C4-HSL, and none of the six deletion-carrying forms of RhlR was able to transcriptionally activate lasB (Fig. 4A and B).

FIG. 3.

Schematic representation of the RhlR protein. The full-length RhlR protein is displayed with the proposed autoinducer (AI)-binding domain, linker, and DBD indicated. The amino acids that underwent site-specific mutagenesis are shown above the drawing. The truncated RhlR polypeptides are displayed below.

FIG. 4.

Multimerization and transcriptional activity of the LexA(DBD)-RhlR deletion forms. E. coli SU101 (A) and the E. coli MG4 lasB::lacZ lysogen (B) carrying the pSR658 vector control, the full-length LexA(DBD)-RhlR fusion protein, and the LexA(DBD)-RhlR truncated proteins were grown with no autoinducer (▪) or with 50 μM C4-HSL (▩). In panel A, the data are expressed relative to the number of Miller units of the LexA(DBD)-RhlR positive control grown in the absence of C4-HSL, which was normalized to 100%, and in panel B, the data are expressed relative to the number of Miller units of the LexA(DBD)-RhlR positive control grown in the presence of 50 μM C4-HSL, which was normalized to 100%. Representative results from one independent assay are presented as the average of triplicates plus the standard error of the mean. A statistically significant difference (P ≤ 0.05) between the samples grown in the absence or presence of autoinducer is indicated by an asterisk. The P value for the RhlR Δ179-239 construct was ≤0.1 (**).

The results of RhlR Δ4-25 demonstrated that the extreme N-terminal end of RhlR is essential for autoinducer-dependent multimerization. Similar results have been reported for the N-terminal end of LasR (15), and the crystal structure of TraR has also shown a dimerization domain present at residues 4 to 11 at the extreme N terminus of this protein (30, 34). The RhlR Δ4-117 deletion form was able to multimerize in an autoinducer-independent fashion, indicating a second multimerization site. Interestingly, the Δ4-117 deletion form of RhlR was unable to transcriptionally activate the lasB::lacZ lysogen. The inability of the LexA(DBD)-RhlR Δ4-161 protein to multimerize demonstrated that deletion of a larger portion of the N terminus may have interrupted this second multimerization domain. Indeed, the crystal structure of TraR showed a major dimerization domain present at the C-terminal end of the N-terminal globular domain (34). Interestingly, two very similar N-terminal truncated forms of LasR (Δ4-160 and Δ4-172) both multimerized in an autoinducer-independent fashion and both possessed transcriptional activity (15). These results implied that LasR and RhlR possess differences in their protein structures. RhlR Δ179-239 demonstrated partial multimerization ability in the presence of C4-HSL but was unable to activate transcription of the lasB::lacZ lysogen. These results implied that the autoinducer-binding portion of RhlR is at the NH2-terminal end, whereas the C-terminal end of RhlR possesses the transcriptional activation domain, similar to other LuxR transcriptional regulator homologs.

Domains of RhlR necessary for C4-HSL binding.

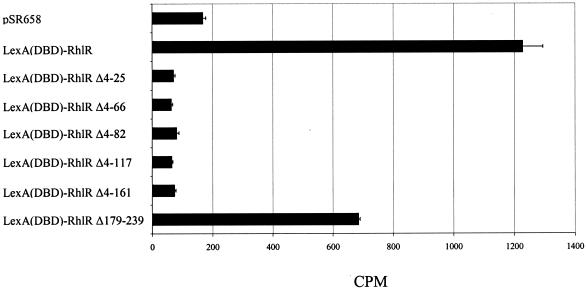

The tritiated-autoinducer retention of E. coli overexpressing LuxR, LasR, or RhlR has been used to analyze autoinducer binding to the cognate transcriptional regulator proteins (10, 16, 22, 24). To determine what regions of RhlR participate in autoinducer binding, the six LexA(DBD)-RhlR truncated forms were assessed for the ability to bind [3H]C4-HSL (Fig. 5). As expected, the results indicated that the pSR658 vector control did not bind [3H]C4-HSL and that the full-length LexA(DBD)-RhlR fusion protein exhibited [3H]C4-HSL binding. None of the N-terminal truncated forms of RhlR bound [3H]C4-HSL, and RhlR with a C-terminal deletion of Δ179-239 demonstrated partial [3H]C4-HSL binding. These data confirmed that the autoinducer-binding domain of RhlR is present at the N-terminal end of the protein. Interestingly, the Δ4-25 truncated form of RhlR was unable to bind [3H]C4-HSL, whereas a Δ2-39 N-terminal truncated form of TraR retains its ability to bind its cognate autoinducer, N-(3-oxo-octanoyl)-l-homoserine lactone (19), demonstrating differences in autoinducer binding between the two proteins. As the Δ179-239 RhlR C-terminal truncated form was the only truncated RhlR protein to demonstrate C4-HSL-dependent multimerization (Fig. 4A) and also bind [3H]C4-HSL, these data further support our conclusion that C4-HSL binding is necessary for RhlR multimerization.

FIG. 5.

[3H]C4-HSL binding by the LexA(DBD)-RhlR truncated proteins. Shown is the radioactivity remaining with E. coli DH5α expressing the pSR658 vector control, the full-length LexA(DBD)-RhlR fusion protein, and the LexA(DBD)-RhlR truncated proteins following incubation with [3H]C4-HSL. Representative results from one independent assay are presented as the average of triplicates plus the standard error of the mean.

Amino acid residues of RhlR necessary for multimerization and transcriptional activity.

To further characterize the structure and function of RhlR, site-specific mutations of single amino acids of RhlR were generated (Fig. 3). Since RhlR is 23% identical and 42% similar to TraR, the mutated amino acids were largely based on the recent crystal structure of TraR (30, 34) and an alignment of the TraR and RhlR amino acid sequences (29). The mutated amino acids are also well conserved among the quorum-sensing transcriptional regulator protein homologs (29). Three mutated RhlR amino acids [Ala-44 (TraR Ala-38), Asp-81 (TraR Asp-70), and Ser-135 (TraR Thr-129)] correspond to amino acids that participate in pheromone binding in TraR. Three other mutated RhlR amino acids [Asp-12 (TraR Asp-6), Leu-162 (TraR Arg-158), and Lys-196 (TraR Lys-189)] correspond to amino acids that participate in protein dimerization in TraR. One mutated RhlR amino acid [Leu-181 (TraR Leu-174)] corresponds to an amino acid that is in the interdomain linker of TraR, and two mutated RhlR amino acids [Thr-211 (TraR Ser-204) and Lys-222 (TraR Arg-215)] correspond to amino acids that are in the DNA-binding helix of TraR. Western analysis with polyclonal anti-LexA antibodies indicated that all of the RhlR proteins with amino acid substitutions were stable in E. coli in the presence of 50 μM C4-HSL to roughly the same level, with the exception of Asp-81-Glu, which was not detected by Western analysis (data not shown). This Asp residue is completely conserved among all LuxR transcriptional regulator homologs (29), and the crystal structure of TraR shows that this Asp residue is completely buried in the autoinducer-binding cavity and that it contacts its autoinducer by a hydrogen bond (30, 34). Interestingly, mutation of the corresponding Asp residue of TraR does not result in protein instability (19). The LexA(DBD)-RhlR Asp-81-Glu mutant protein did not multimerize, possess transcriptional activity, or bind [3H]C4-HSL, which correlated with its instability (data not shown).

The Ala-44-Gly and Ser-135-Thr amino acid substitutions altered amino acids that might participate in autoinducer binding. The data indicated that the Ser-135-Thr mutant protein did not form multimers or transcriptionally activate the lasB::lacZ lysogen and that the Ala-44-Gly mutant protein did not form multimers or activate transcription as well as the wild-type LexA(DBD)-RhlR fusion (Fig. 6A and B). Luo et al. have also recently shown that an alanine-to-valine mutation of the corresponding amino acid of TraR demonstrated decreased autoinducer retention and also a reduction in the ability of TraR to dimerize or activate reporter expression (19). Of the amino acid substitutions that may participate in protein multimerization (Asp-12-Glu, Leu-162-Val, and Lys-196-Arg), only the Lys-196-Arg mutant protein demonstrated partial impairment of RhlR multimerization, suggesting that RhlR differs from TraR. Interestingly, the Lys-196-Arg mutant protein was unable to transcriptionally activate the lasB::lacZ lysogen. Since this site-specific mutation was generated at the C-terminal end of the protein near the hypothetical transcriptional activation domain of RhlR (residues 209 to 223 on the basis of homology to TraR), it may have disrupted the DNA-binding helix, leading to the loss of transcriptional activation abilities. The amino acid substitution in the interdomain linker (Leu-181-Val) demonstrated complete impairment in multimerization and activation abilities, and the two amino acid substitutions in the hypothetical transcriptional activation domain (Thr-211-Ser and Lys-222-Arg) demonstrated partial impairment of multimerization and complete impairment of the ability of RhlR to transcriptionally activate the lasB::lacZ lysogen.

FIG. 6.

Multimerization and transcriptional activity of the LexA(DBD)-RhlR site-specific mutant proteins. E. coli SU101 (A) and the E. coli MG4 lasB::lacZ lysogen (B) carrying the pSR658 vector control, the full-length LexA(DBD)-RhlR fusion protein, and the LexA(DBD)-RhlR site-specific mutant proteins were grown in the presence of 0 (▪) or 50 (▩) μM C4-HSL. In panel A, the data are expressed relative to the number of Miller units of the LexA(DBD)-RhlR positive control grown in the absence of C4-HSL, which was normalized to 100%, and in panel B, the data are expressed relative to the number of Miller units of the LexA(DBD)-RhlR positive control grown in the presence of 50 μM C4-HSL, which was normalized to 100%. Representative results from one independent assay are presented as the average of triplicates plus the standard error of the mean. A statistically significant difference (P ≤ 0.05) between the samples grown in the absence or presence of autoinducer is indicated by an asterisk.

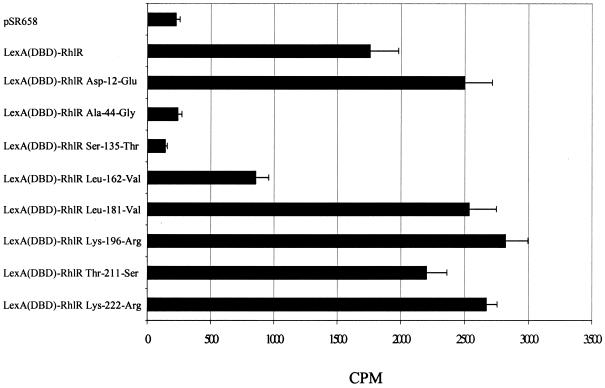

Binding of C4-HSL to LexA(DBD)-RhlR site-specific mutant proteins.

We tested the RhlR constructs containing single amino acid substitutions for the ability to bind [3H]C4-HSL (Fig. 7). The LexA(DBD)-RhlR amino acid substitutions Asp-12-Glu, Leu-181-Val, Lys-196-Arg, Thr-211-Ser, and Lys-222-Arg were able to bind [3H]C4-HSL as well as the wild-type LexA(DBD)-RhlR fusion protein, and the Leu-162-Val amino acid substitution showed moderate impairment of the ability to bind [3H]C4-HSL. The Ala-44-Gly and Ser-135-Thr mutant proteins showed binding similar to that of the pSR658 vector control.

FIG. 7.

[3H]C4-HSL binding by LexA(DBD)-RhlR mutant proteins. Shown is the radioactivity remaining with E. coli DH5α expressing the pSR658 vector control, the full-length LexA(DBD)-RhlR fusion protein, and the indicated LexA(DBD)-RhlR site-specific mutant proteins following incubation with [3H]C4-HSL. Representative results combined from two independent assays are presented as the average of six replicates plus the standard error of the mean.

The binding assays demonstrated that amino acids that participate in C4-HSL binding in RhlR (Ala-44 and Ser-135) correspond to amino acids that participate in pheromone binding in TraR. The assays also further demonstrated that [3H]C4-HSL binding was necessary for multimerization. The Asp-12-Glu, Leu-162-Val, Lys-196-Arg, Thr-211-Ser, and Lys-222-Arg site-specific mutant proteins, which demonstrated the ability to multimerize, bound [3H]C4-HSL, and the Ala-44-Gly and Ser-135-Thr mutant proteins, which did not multimerize, did not bind [3H]C4-HSL. However, [3H]C4-HSL binding was not always sufficient for multimerization to occur. Thus, the protein containing the site-specific amino acid mutation in the interdomain linker (Leu-181-Val) bound [3H]C4-HSL even though it was unable to multimerize or transcriptionally activate lasB. These results indicated that while RhlR and TraR possess many similar conserved amino acid residues for autoinducer binding and transcriptional activation, the amino acids that participate in multimerization are not homologous between these two proteins.

Inhibition of wild-type RhlR in P. aeruginosa.

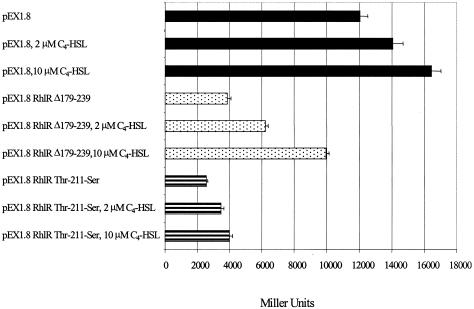

It has previously been demonstrated that the mutated LuxR, TraR, and LasR proteins interfere with the function of their wild-type counterparts (2, 15, 18). To determine if RhlR functions as a multimer in vivo, the RhlR C-terminal deletion of amino acids 179 to 239 and the Thr-211-Ser site-specific mutation, which demonstrated multimerization but not transcriptional activation capabilities, were expressed in wild-type P. aeruginosa carrying an rhlA::lacZ fusion (13). If these proteins multimerize with wild-type RhlR and inhibit its ability to transcriptionally activate rhlA, then they will act as dominant negative forms. Consequently, a decrease in β-galactosidase activity from the pEX1.8 control will be observed. Figure 8 shows that the RhlR Δ179-239 C-terminal deletion and the RhlR Thr-211-Ser site-specific mutation were able to inactivate wild-type RhlR. Addition of 2 or 10 μM C4-HSL increased the β-galactosidase activity of the rhlA::lacZ lysogen in both the pEX1.8 control and experimental samples; however, in no case did the activity from the experimental samples reach that of the pEX1.8 control. These results indicate that RhlR functions as a multimer in P. aeruginosa.

FIG. 8.

Inhibition of wild-type RhlR in P. aeruginosa. Shown is the PAO220 rhlA::lacZ fusion expressing the pEX1.8 vector control (▪), pEX1.8 RhlR Δ179-239 (░⃞), and pEX1.8 RhlR Thr-211-Ser (▤). When indicated, 2 or 10 μM C4-HSL was added to the assay. If the mutated RhlR proteins multimerize and inactivate the wild-type RhlR present in the cell, RhlR will be unable to activate the rhlA::lacZ fusion and a decrease in β-galactosidase activity will be seen. Representative results from one independent assay are presented as the average of triplicates plus the standard error of the mean.

Conclusions.

The data generated by the multimerization, transcriptional activation, and C4-HSL-binding studies indicate that basic function of RhlR is similar to that of LasR, TraR, and LuxR; however, differences in the structure of the RhlR protein were also elucidated. It was demonstrated that, similar to that of LasR (15), RhlR multimerization is dependent on its cognate autoinducer and multimerization is necessary for transcriptional activity. In addition, the deletion, site-specific mutation, and C4-HSL-binding results indicated that the autoinducer-binding domain is present at the N-terminal end and the transcriptional activation domain is present at the C-terminal end of RhlR, as in other transcriptional regulator homologs. In contrast, the site-specific mutation results demonstrated that the amino acid residues that play a role in the multimerization of RhlR and TraR (30, 34) differ between the two proteins. Also, the RhlR deletion data demonstrated differences between RhlR and LasR. The Δ4-117 deletion form of RhlR multimerized in an autoinducer-independent fashion and was unable to activate transcription, while similar deletion forms of LasR (15) possessed both multimerization and transcriptional activation abilities. These data support previous suggestions that the P. aeruginosa lasR and rhlR genes were not the result of a gene duplication event and were acquired independently of each other (9).

With DNA microarrays, it was recently discovered that the las and rhl quorum-sensing systems can function as negative regulators (26, 32). It is still unknown if RhlR can directly down-regulate transcription or if the negative regulation is a downstream effect of RhlR-activated genes. If RhlR does directly function as a negative regulator, it will be interesting to determine if the multimer form of RhlR is necessary for it to down-regulate target gene expression, as is required to activate gene expression.

Acknowledgments

We thank Melanie Filiatrault and Lou Passador for critical review of the manuscript.

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation under a postdoctoral grant awarded in 2000 to J.R.L. (DBI-0074374) and by a National Institutes of Health research grant (AI133713) to B.H.I.

REFERENCES

- 1.Brint, J. M., and D. E. Ohman. 1995. Synthesis of multiple exoproducts in Pseudomonas aeruginosa is under the control of RhlR-RhlI, another set of regulators in strain PAO1 with homology to the autoinducer-responsive LuxR-LuxI family. J. Bacteriol. 177:7155-7163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Choi, S. H., and E. P. Greenberg. 1992. Genetic evidence for multimerization of LuxR, the transcriptional activator of Vibrio fischeri luminescence.Mol. Marine Biol. Biotechnol. 1:408-413. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Choi, S. H., and E. P. Greenberg. 1991. The C-terminal region of the Vibrio fischeri LuxR protein contains an inducer-independent lux gene activating domain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 88:11115-11119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chugani, S. A., M. Whiteley, K. M. Lee, D. D'Argenio, C. Manoil, and E. P. Greenberg. 2001. QscR, a modulator of quorum-sensing signal synthesis and virulence in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:2752-2757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Daines, D. A., and R. P. Silver. 2000. Evidence for multimerization of neu proteins involved in polysialic acid synthesis in Escherichia coli K1 using improved LexA-based vectors. J. Bacteriol. 182:5267-5270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Devine, J. H., G. S. Shadel, and T. O. Baldwin. 1989. Identification of the operator of the lux regulon from the Vibrio fischeri strain ATCC 7744. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 86:5688-5692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dmitrova, M., G. Younes-Cauet, P. Oertel-Buchheit, D. Porte, M. Schnarr, and M. Granger-Schnarr. 1998. A new LexA-based genetic system for monitoring and analyzing protein heterodimerization in Escherichia coli. Mol. Gen. Genet. 257:205-212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Govan, J., and G. Harris. 1986. Pseudomonas aeruginosa and cystic fibrosis: unusual bacterial adaptation and pathogenesis. Microbiol. Sci. 3:302-308. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gray, K. M., and J. R. Garey. 2001. The evolution of bacterial LuxI and LuxR quorum sensing regulators.Microbiology 147:2379-2387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hanzelka, B. L., and E. P. Greenberg. 1995. Evidence that the N-terminal region of the Vibrio fischeri LuxR protein constitutes an autoinducer-binding domain. J. Bacteriol. 177:815-817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hardalo, C., and S. C. Edberg. 1997. Pseudomonas aeruginosa: assessment of risk from drinking water. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 23:47-75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hershberger, C., R. Ye, M. Parsek, Z. Xie, and A. M. Chakrabarty.1995. . The algT (algU) gene of Pseudomonas aeruginosa, a key regulator involved in alginate biosynthesis, encodes an alternative sigma factor (σE). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:7941-7945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hoang, T. T., A. J. Kutchma, A. Becher, and H. P. Schweizer. 2000. Integration-proficient plasmids for Pseudomonas aeruginosa: site-specific integration and use for engineering of reporter and expression strains.Plasmid 43:59-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Howorka, S., and H. Bayley. 1998. Improved protocol for high-throughput cysteine scanning mutagenesis.BioTechniques 25:764-766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kiratisin, P., K. D. Tucker, and L. Passador. 2002. LasR, a transcriptional activator of Pseudomonas aeruginosa virulence genes, functions as a multimer. J. Bacteriol. 184:4912-4919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kline, T., J. Bowman, B. H. Iglewski, T. de Kievit, Y. Kakai, and L. Passador. 1999. Novel synthetic analogs of the Pseudomonas autoinducer. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 9:3447-3452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ledgham, F., I. Ventre, C. Soscia, M. Foglino, J. N. Sturgis, and A. Lazdunski. 2003. Interactions of the quorum sensing regulator QscR: interaction with itself and the other regulators of Pseudomonas aeruginosa LasR and RhlR. Mol. Microbiol. 48:199-210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Luo, Z. Q., and S. K. Farrand. 1999. Signal-dependent DNA binding and functional domains of the quorum-sensing activator TraR as identified by repressor activity.Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:9009-9014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Luo, Z. Q., A. J. Smyth, P. Gao, Y. Qin, and S. K. Farrand. 2003. Mutational analysis of TraR: correlating function with molecular structure of a quorum-sensing transcriptional activator. J. Biol. Chem. 4:4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miller, J. 1972. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 21.Ohman, D. E., S. J. Cryz, and B. H. Iglewski. 1980. Isolation and characterization of a Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO mutant that produces altered elastase. J. Bacteriol. 142:836-842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pearson, J. P., E. C. Pesci, and B. H. Iglewski. 1997. Roles of Pseudomonas aeruginosa las and rhl quorum-sensing systems in control of elastase and rhamnolipid biosynthesis genes.J. Bacteriol. 179:5756-5767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pesci, E., and B. Iglewski. 1999. Quorum sensing in Pseudomonas aeruginosa, p.147 -155. In G. Dunny and S. Winans (ed.), Cell-cell signaling in bacteria. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 24.Pesci, E., J. Pearson, P. Seed, and B. Iglewski. 1997. Regulation of las and rhl quorum sensing in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 179:3127-3132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 26.Schuster, M., C. P. Lostroh, T. Ogi, and E. P. Greenberg.2003. . Identification, timing, and signal specificity of Pseudomonas aeruginosa quorum-controlled genes: a transcriptome analysis. J. Bacteriol. 185:2066-2079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Seed, P., L. Passador, and B. Iglewski. 1995. Activation of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa lasI gene by LasR and the Pseudomonas autoinducer PAI: an autoinduction regulatory hierarchy. J. Bacteriol. 177:654-659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smith, A. W., and B. H. Iglewski. 1989. Transformation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa by electroporation. Nucleic Acids Res. 17:10509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stevens, A., and E. P. Greenberg. 1999. Transcriptional activation by LasR, p.231 -242. In G. Dunny and S. Winans (ed.), Cell-cell signaling in bacteria. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 30.Vannini, A., C. Volpari, C. Gargioli, E. Muraglia, R. Cortese, R. De Francesco, P. Neddermann, and S. D. Marco. 2002. The crystal structure of the quorum sensing protein TraR bound to its autoinducer and target DNA. EMBO J. 21:4393-4401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ventre, I., F. Ledgham, V. Prima, A. Lazdunski, M. Foglino, and J. N. Sturgis. 2003. Dimerization of the quorum sensing regulator RhlR: development of a method using EGFP fluorescence anisotropy. Mol. Microbiol. 48:187-198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wagner, V. E., D. Bushnell, L. Passador, A. I. Brooks, and B. H. Iglewski. 2003. Microarray analysis of Pseudomonas aeruginosa quorum-sensing regulons: effects of growth phase and environment. J. Bacteriol. 185:2080-2095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Welch, M., D. E. Todd, N. A. Whitehead, S. J. McGowan, B. W. Bycroft, and G. P. Salmond.2000. . N-acyl homoserine lactone binding to the CarR receptor determines quorum-sensing specificity in Erwinia.EMBO J. 19:631-641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang, R. G., T. Pappas, J. L. Brace, P. C. Miller, T. Oulmassov, J. M. Molyneaux, J. C. Anderson, J. K. Bashkin, S. C. Winans, and A. Joachimiak. 2002. Structure of a bacterial quorum-sensing transcription factor complexed with pheromone and DNA.Nature 417:971-974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhu, J., and S. Winans. 2001. The quorum-sensing transcriptional regulator TraR requires its cognate signaling ligand for protein folding, protease resistance, and dimerization.Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:1507-1512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]