Abstract

The serine cycle methylotroph Methylobacterium extorquens AM1 contains two pterin-dependent pathways for C1 transfers, the tetrahydrofolate (H4F) pathway and the tetrahydromethanopterin (H4MPT) pathway, and both are required for growth on C1 compounds. With the exception of formate-tetrahydrofolate ligase (FtfL, alternatively termed formyl-H4F synthetase), all of the genes encoding the enzymes comprising these two pathways have been identified, and the corresponding gene products have been purified and characterized. We present here the purification and characterization of FtfL from M. extorquens AM1 and the confirmation that this enzyme is encoded by an ftfL homolog identified previously through transposon mutagenesis. Phenotypic analyses of the ftfL mutant strain demonstrated that FtfL activity is required for growth on C1 compounds. Unlike mutants defective for the H4MPT pathway, the ftfL mutant strain does not exhibit phenotypes indicative of defective formaldehyde oxidation. Furthermore, the ftfL mutant strain remained competent for wild-type conversion of [14C]methanol to [14C]CO2. Collectively, these data confirm our previous presumptions that the H4F pathway is not the key formaldehyde oxidation pathway in M. extorquens AM1. Rather, our data suggest an alternative model for the role of the H4F pathway in this organism in which it functions to convert formate to methylene H4F for assimilatory metabolism.

Growth of aerobic methylotrophic bacteria on single-carbon (C1) substrates generally involves the production of formaldehyde as a central intermediate. In the facultative methylotroph Methylobacterium extorquens AM1, the formaldehyde produced from the primary oxidation of C1 substrates condenses with either tetrahydrofolate (H4F) or tetrahydromethanopterin (H4MPT) to form the respective methylene derivatives (reviewed in reference 39). The reaction of formaldehyde with H4MPT, a folate analogue that had long been thought to be unique to methanogenic archaea (9), can occur either spontaneously or through the action of the formaldehyde-activating enzyme, Fae (42). Methylene-H4MPT is subsequently oxidized to methenyl-H4MPT and then formyl-H4MPT (14, 34, 40), which is ultimately hydrolyzed by the formyltransferase/hydrolase complex, Fhc, to produce formate and free H4MPT (32, 33). Mutants defective for the H4MPT pathway fail to grow on C1 substrates and are sensitive to the presence of compounds that lead to the production of formaldehyde (14, 27, 30, 42). These data have led to the suggestion that the H4MPT pathway serves as the primary formaldehyde oxidation and detoxification pathway.

Formaldehyde can also spontaneously react with H4F to form methylene-H4F. No enzymatic activity has been found thus far to catalyze this reaction (42). Methylene-H4F serves as the C1 donor for assimilation of formaldehyde through the serine cycle (reviewed in reference 21). Alternatively, methylene-H4F potentially can be converted to methenyl-H4F, and then formyl-H4F, through the action of an NADP-dependent methylene-H4F dehydrogenase (MtdA) (10, 40) and methenyl-H4F cyclohydrolase (Fch) (11, 34), respectively. Coupled to the conversion of ADP to ATP, formyl-H4F can then be reversibly oxidized to formate and free H4F through the action of formate-H4F ligase (FtfL, alternatively termed formyl-H4F synthetase [35]). The formate produced either through the H4F- or H4MPT-dependent C1 transfer pathway may then be oxidized to CO2 by formate dehydrogenases (20; L. Chistoserdova and M. E. Lidstrom, unpublished data).

The enzymes of the H4F pathway are found at high specific activities in serine cycle methylotrophs and are generally present at three- to fourfold higher levels during growth on C1 compounds than on multicarbon compounds (10, 26, 34, 40). As the H4F-dependent C1 transfer reactions are reversible, it has been postulated that this pathway is responsible for channeling carbon into the serine cycle during growth on formate (18), but this has never been demonstrated by mutant analysis. Additionally, the absence of significant levels of NAD (17) or dye-linked (26) formaldehyde dehydrogenase activities led to the suggestion that the H4F-linked C1 transfer pathway might be the key formaldehyde oxidation pathway in these organisms (26). The surprising discovery of the H4MPT pathway in M. extorquens AM1 (9) and other methylotrophs (41) refocused attention on the role of the H4F-linked C1 transfer pathway. The discovery that Fhc releases formate, rather than CO2, as the end product of the H4MPT pathway (32) showed a direct connection between the two C1 transfer pathways and raised the possibility that the H4F pathway may function during growth on methanol to convert formate into methylene-H4F, the starting substrate for the serine cycle (32, 39).

Results of the previous genetic analyses of H4F-dependent C1 transfer in M. extorquens AM1 have been somewhat inconclusive. It was shown that null mutants of mtdA or fchA could not be obtained even during growth on multicarbon substrates such as succinate (10, 11, 40). This was assumed to be due to their critical role during growth on multicarbon compounds, likely in producing formyl-H4F for the biosynthesis of purines and other compounds. Mutants with a reduced activity of MtdA or Fch were obtained, however, and these were found to be defective for growth on C1 compounds. These data confirmed a role for these enzymes in methylotrophy but did not clarify whether that role was in formaldehyde oxidation or in another function. Formate-H4F ligase activity had been detected in serine cycle methylotrophs (19, 26), but a candidate gene responsible for encoding its activity had not been identified, nor had mutants defective for FtfL been generated. Very recently, however, a strain negative for C1 growth was identified that contained a transposon insertion into a gene with a predicted gene product homologous to known FtfL sequences (30).

Here we present the purification and biochemical characterization of FtfL from M. extorquens AM1 and confirm that this activity is encoded by the ftfL homolog previously identified (30). Physiological analyses of ftfL mutant strains establish that this enzymatic activity, and thus a complete H4F pathway, is required for growth on C1 compounds. Our data are inconsistent, however, with the model in which the main role of this pathway is in formaldehyde oxidation (26). Rather, our data support a model in which the H4F pathway functions to provide methylene-H4F for the serine cycle from formate (32, 39).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

M. extorquens AM1 (31) strains were grown at 30°C on a minimal salts medium (2) containing carbon sources at the following concentrations: 35 mM formate, 125 mM methanol, 35 mM methylamine, 15 mM oxalate, or 15 mM succinate. Escherichia coli strains were grown on Luria-Bertani (LB) medium (35). Antibiotics were added at the following final concentrations: 50 μg of ampicillin/ml, 50 μg of kanamycin/ml, 50 μg of rifamycin/ml, 35 μg of streptomycin/ml, and 10 μg of tetracycline/ml. All chemicals were obtained from Sigma. Nutrient agar and Bacto-agar were obtained from Difco. For purification of FtfL, wild-type M. extorquens AM1 was cultivated in a 50-liter fermenter (Inceltech Bioline) containing 40 liters of medium with methanol. The fermenter was stirred at 300 rpm and gassed with air (5 liters/min). The cultures were harvested in the late exponential phase at a cell density, OD578, of 4.0. Cells were pelleted by centrifugation at 5,000 × g and stored at −70°C until later use.

FtfL assay.

The assay for FtfL activity was based on the quantitative conversion of N10-formyl-H4F formed in the enzymatic reaction to methenyl-H4F by the addition of acid (35). Methenyl-H4F is determined spectrophotometrically by its characteristic absorption maximum at 350 nm. The assays were performed at 30°C as described previously (35). In brief, the standard assay mixture contained 0.1 M Tris buffer (pH 8.0), 2 mM +l-tetrahydrofolate (H4F) (Sigma; a 10 mM stock solution was prepared in 1.0 M 2-mercaptoethanol and neutralized with 1 N KOH), 10 mM MgCl2, 5 mM ATP, 200 mM sodium formate, and enzyme. The solution was incubated at 30°C, and the reaction was stopped at different time points by the addition of 2 ml of 0.36 N HCl/ml. The reaction mixtures were then allowed to stand at room temperature for 10 min. The absorbance of methenyl-H4F was determined at 350 nm (ɛ = 24.9 mM−1 cm−1 [16]).

Protein purification.

Frozen cells (30 g) of M. extorquens AM1 were resuspended in 50 mM morpholinepropanesulfonic acid (MOPS)-KOH (pH 7.0; buffer A) at 4°C. Cells were disrupted by ultrasonication (Sonicator 250; Branson Ultrasonic) twice for 10 min (50% duty cycles). Centrifugation was performed at 150,000 × g for 1 h to remove cell debris, whole cells, and the membrane fraction, which was shown to contain only traces of FtfL activity. Protein concentration was determined by the Bradford assay using Bio-Rad reagent with bovine serum albumin as the standard (7).

Formate-H4F ligase (FtfL) from M. extorquens AM1 was purified at 4°C under aerobic conditions. Saturated ammonium sulfate buffer A (61 ml) was added to 61 ml of the soluble fraction stirred on ice. After 15 min of stirring, the precipitated protein was removed by centrifugation at 20,000 × g for 1 h. The supernatant was applied to a phenyl Sepharose column (High Performance 26/10; Amersham Biosciences) equilibrated with 2 M ammonium sulfate [(NH4)2SO4] in buffer A. With a linear gradient decreasing from 2 to 0 M (NH4)2SO4 (540 ml), FtfL activity was found at about 0.4 M (NH4)2SO4. Combined active fractions were diluted with buffer A (pH 7.0) (1:5) and subjected to anion-exchange chromatography on a Source 15Q column (16/10; Amersham Biosciences) equilibrated with buffer A. The enzyme activity was recovered in the flowthrough of the column. The enzyme was further purified using a hydroxylapatite column (16/10; Bio-Rad) equilibrated with 10 mM potassium phosphate, pH 7.0. Protein was eluted with a step gradient of 25, 50, 75, 100, 150, 250, and 500 mM potassium phosphate (30 ml at each step). FtfL was eluted at 75 mM potassium phosphate. Active fractions were pooled, diluted in buffer A (1:2), and loaded on a Resource Q column equilibrated with buffer A. Purified protein was eluted with an increasing NaCl gradient (0 to 1 M NaCl in 150 ml). The purified enzyme was eluted with 0.4 M NaCl.

Gel electrophoresis and molecular mass determination.

Purified protein was subjected to electrophoresis in a 14% polyacrylamide gel and stained with Coomassie brilliant blue R250. The native molecular mass was estimated from gel filtration experiments on a Superdex 200 column (Amersham Biosciences) using the following standards: ferritin (440 kDa), catalase (232 kDa), peroxidase (44 kDa), and chymotrypsinogen (25 kDa).

Determination of the N-terminal amino acid sequence.

Purified enzyme was electrophoresed in the presence of sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) and electroblotted onto a polyvinyl trifluoride membrane (Applied Biosystems). The amino acid sequence was determined on a 477 protein-peptide sequencer from Applied Biosystems by D. Linder, University of Giessen, Giessen, Germany.

Generation of ftfL mutant strains and complementing plasmid.

M. extorquens AM1 mutants defective for ftfL were generated using the targeted mutagenesis vector pCM184 (28). The regions immediately flanking ftfL were amplified by PCR, and the resulting products for the upstream and downstream flanks were cloned into pCR2.1 (Invitrogen) to produce pCM213 and pCM214, respectively. The 0.6-kb BglII-NcoI fragment from pCM213 was introduced between the corresponding sites of pCM184 to produce pCM215. Subsequently, the 0.5-kb SacII-SacI fragment from pCM214 was ligated into the same sites of pCM215 to produce pCM216. A ΔftfL::kan mutant of M. extorquens AM1, CM216K.1, was generated by introducing pCM216 by conjugation from E. coli S17-1 (38) as previously described (8). An unmarked ΔftfL strain CM216.1 was generated using the cre-expressing plasmid pCM157 as described elsewhere (28). Two double mutant strains were constructed by introducing pCM216 into CM198.1 (28) to generate the Δfae ΔftfL::kan mutant CM198-216K.1 and by introducing pCM212 (30) into CM216.1 to generate the ΔftfL ΔdmrA::kan mutant CM216-212K.1. All mutants were confirmed by diagnostic PCR analysis.

In order to construct a plasmid to complement ftfL-defective strains, a 2.7-kb region containing the ftfL coding region and putative promoter was amplified by PCR and cloned into pCR2.1 (Invitrogen) to produce pCM217. The entire 2.7-kb region of pCM217 was sequenced (University of Washington Biochemistry Department DNA Sequencing Facility) to confirm the sequence present on the ERGO website (www.integratedgenomics.com/genomereleases.html#list6). The 2.7-kb HindIII-BamHI fragment of pCM217 was cloned into the same sites of the broad-host-range cloning vector pCM62 (25) to produce pCM218, which was then introduced into the appropriate M. extorquens AM1 strains using the helper plasmid pRK2073 (13). All strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

M. extorquens AM1 strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Description | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| CM194K.1 | ΔmxaF::kan | 27 |

| CM198.1 | Δfae | 28 |

| CM198K.1 | Δfae::kan | 28 |

| CM198-216K.1 | Δfae ΔftfL::kan | This study |

| CM212K.1 | ΔdmrA::kan | 30 |

| CM216.1 | ΔftfL | This study |

| CM216K.1 | ΔftfL::kan | This study |

| CM216-212K.1 | ΔftfL ΔdmrA::kan | This study |

| M. extorquens AM1 | Rifr derivative | 31 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pCM62 | Broad-host-range cloning vector | 29 |

| pCM80 | M. extorquens AM1 expression vector (PmxaF) | 29 |

| pCM106 | pCM80 with flhA-fghA from P. denitrificans | 27 |

| pCM157 | Broad-host-range cre expression vector | 28 |

| pCM184 | Broad-host-range allelic exchange vector | 28 |

| pCM212 | Donor to generate ΔdmrA::kan mutation | 30 |

| pCM213 | pCR2.1 with ftfL upstream flank | This study |

| pCM214 | pCR2.1 with ftfL downstream flank | This study |

| pCM215 | pCM184 with ftfL upstream flank | This study |

| pCM216 | pCM215 with ftfL upstream flank | This study |

| pCM217 | pCR2.1 with 2.7-kb ftfL region | This study |

| pCM218 | pCM62 with ftfL region | This study |

| pCR2.1 | PCR cloning vector | Invitrogen |

| pRK2073 | Helper plasmid expressing IncP tra functions | 13 |

Phenotypic analyses of ftfL mutant strains.

In order to compare the growth of wild-type M. extorquens AM1 and CM216K.1 in liquid medium, cultures were grown to mid-exponential phase in medium containing succinate, centrifuged, and then resuspended into medium containing either succinate or methanol. After 2 h, methanol was added to one set of succinate flasks to a final concentration of 125 mM. Mutant phenotypes were also assessed on solid medium by comparing the relative rate of colony formation. Sensitivity to methanol or formaldehyde was assayed using succinate medium to which methanol or formaldehyde was added immediately before pouring plates at the following tested concentrations: 125, 10, and 1 mM and 100, 10, 1, and 0.1 μM for methanol; 1, 0.5, 0.1, 0.05, 0.01, and 0.005 mM for formaldehyde. Because an undetermined fraction will volatilize, particularly for methanol, the reported MIC is a maximum value. All phenotypic analyses were performed at least twice.

Whole-cell CO2 production assay.

In order to determine whether mutants defective for the H4F and/or H4MPT pathways were capable of oxidation of methanol to CO2, the rate of [14C]CO2 production from [14C]methanol was determined using a variation of previous methods (4, 22). Assays were performed at room temperature with cultures of wild-type M. extorquens AM1 and appropriate mutants in three independent experiments. Cultures grown to mid-exponential phase on succinate were centrifuged and resuspended to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 1.0. The assays were initiated by the addition of methanol to a final concentration of 1 mM, with 3.3 μCi of [14C]methanol (Sigma)/μl. Aliquots of 0.3 ml of the cell suspension containing methanol were then immediately dispensed into 2.0-ml autosampling vials (Kimble) and sealed with black phenolic screw cap tops (Kimble) and red polytetrafluoroethylene-faced white silicone septa (Kimble). Every 5 min, 0.3 ml of 0.1 M NaOH was added with a syringe to a set of samples to stop growth and trap CO2 as bicarbonate. The samples were equilibrated for 1 h and then centrifuged to remove cell material, and 0.4 ml of cell-free spent medium was placed into an 80°C heat block to allow for complete evaporation to eliminate the [14C]methanol. The samples were then resuspended in 0.4 ml of distilled H2O and transferred into 20-ml serum vials (Kimble). Truncated 1.7-ml Eppendorf tubes containing 0.2 ml of phenylethylamine were placed into the serum vials, and the vials were capped with one-piece aluminal seal crimp tops (Kimble) and Teflon-lined grey butyl septa (Wheaton). Bicarbonate was released as CO2 through the addition by syringe of 0.3 ml of 0.3 M HCl to each of the stoppered vials, and the CO2 was again trapped as bicarbonate in the phenylethylamine. After 1 h was allowed for equilibration, the vials were opened and the phenylethylamine was transferred into scintillation vials and counted. Controls were performed with 14C-labeled C1 compounds to confirm >99% retention of bicarbonate, 85% loss of formate, and >99% loss of both methanol and formaldehyde. Given that formate does not accumulate in the cell medium to appreciable amounts (M. Laukel et al., unpublished results) and that formate production requires formaldehyde oxidation, the minor retention of formate in this protocol did not significantly alter the results or their interpretation. The means and standard errors of three separate experiments are presented in nanomoles of [14C]CO2 OD600−1.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence of ftfL provided in the genome sequence data (www.integratedgenomics.com/genomereleases.html#list6) was confirmed and deposited with GenBank (accession no. AY279316).

RESULTS

Purification of FtfL from M. extorquens AM1 and identification of the encoding gene.

Cell extracts of M. extorquens AM1 grown in the presence of methanol contained FtfL activity of 0.42 U/mg. The FtfL activity was associated with the soluble cell fraction. Purification of FtfL was achieved by ammonium sulfate precipitation and four chromatographic steps as described in Table 2. Purification was 279-fold with a yield of 18% and resulted in protein with a specific activity of 117 U/mg.

TABLE 2.

Purification of FtfL from M. extorquens AM1 grown on methanola

| Purification step | Protein (mg) | Activity (U) | Sp act (U/mg) | Purification (fold) | Yield (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soluble fraction | 2,394 | 1,016 | 0.42 | 1 | 100 |

| (NH4)2SO4 supernatant | 441 | 779 | 1.8 | 4 | 77 |

| Phenyl Sepharose | 46 | 937 | 20.4 | 49 | 92 |

| Source15Q | 28 | 524 | 18.7 | 45 | 52 |

| Hydroxyapatite | 5.7 | 522 | 92 | 219 | 51 |

| Resource Q | 1.6 | 187 | 117 | 279 | 18 |

Enzyme activity was determined as described in the text.

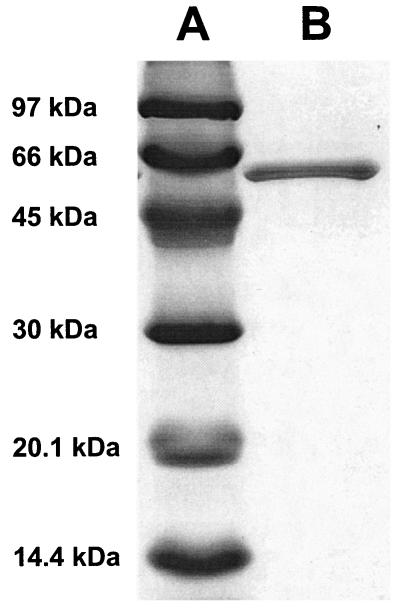

SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) analysis revealed the presence of one polypeptide of an apparent molecular mass of about 60 kDa (Fig. 1). Its N-terminal amino acid sequence was determined to be PSDIEIA?AATL. The encoding gene was identified in the unfinished genome database of M. extorquens AM1 (www.integratedgenomics.com/genomereleases.html#list6) and was recently predicted to encode FtfL (30). The deduced protein has a predicted molecular mass of 59.4 kDa and is therefore in agreement with the determination by SDS-PAGE of the purified protein. The predicted amino acid sequence of FtfL from M. extorquens AM1 (GenBank accession no. AY279316) shows 65% identity to the putative FtfL from Mesorhizobium loti (GenBank accession no. BAB49812) and 60% identity to FtfL from Moorella thermoacetica (GenBank accession no. A35942). FtfL from M. thermoacetica (previously referred to as Clostridium thermoaceticum) was studied in detail biochemically, and the crystal structure of this enzyme has been determined (36). Amino acid residues predicted to participate in binding ATP (amino acids 58 to 85), H4F (amino acids 197 to 202), and formyl phosphate (R97) (36) are conserved within FtfL from M. extorquens AM1 (data not shown). High sequence conservation between FtfL proteins from M. thermoacetica and M. extorquens AM1 suggests similar chemical, physical, and enzymatic properties as those for the well-studied enzymes present in gram-positive bacteria.

FIG. 1.

SDS-PAGE analysis of purified FtfL from M. extorquens AM1. Proteins were separated in a 14% polyacrylamide gel and stained with Coomassie brilliant blue R250. Lane A, molecular mass standards; lane B, 2.2 μg of purified FtfL.

Molecular and catalytic properties of FtfL.

The apparent molecular mass of FtfL was determined by gel filtration on Superdex 200 (Amersham Biosciences). Elution profiles indicated a native mass of about 240,000 Da. Since the subunit molecular mass of FtfL is predicted to be 59,400 Da, a homotetrameric structure is suggested. This mass correlates well with the mass for clostridial FtfLs that are homotetramers of molecular mass 240,000 Da (25). The UV-visible spectrum of the enzyme was that of a protein lacking a chromophoric prosthetic group.

The dependence of the rate of the reaction upon the concentration of formate, H4F, and ATP was determined using purified FtfL, and the apparent Km for each substrate was calculated according to the method of Lineweaver and Burk. The apparent Km for formate was found to be 22 mM, for H4F it was 0.8 mM, and for ATP it was 21 μM. The comparison to FtfL from clostridia including M. thermoacetica (24) reveals Km values for formate and H4F in the same order of magnitude (Km values for formate between 5 and 16 mM; values for H4F between 0.2 and 0.74 mM). Only the Km values for ATP from the gram-positive organisms were in general somewhat higher, 60 μM to 0.29 mM, for ATP than that from M. extorquens AM1.

To test whether FtfL is specific for H4F or whether H4MPT could also be formylated, H4F was replaced by H4MPT in the standard enzyme assay (under acidic conditions the formyl group of H4MPT is converted to methenyl-H4MPT [12] as for formyl-H4F). No enzyme activity was detected, suggesting that FtfL from M. extorquens AM1 is specific for H4F.

Generation of a ΔftfL::kan mutant by allelic exchange and phenotypic analysis.

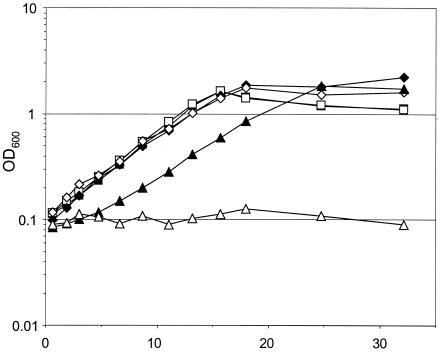

A ΔftfL::kan mutant, CM216K.1, was generated using the allelic exchange vector pCM184 (28). Cell extracts of the resulting ΔftfL::kan strain CM216K.1 lacked detectable FtfL activity. The CM216K.1 mutant grew like wild-type M. extorquens AM1 on solid medium containing succinate but showed no growth on plates containing methanol or methylamine. The mutant strain containing a plasmid with the ftfL gene (pCM218) grew normally, demonstrating that the defect in the mutant was due to the loss of FtfL. Growth experiments in liquid medium containing either succinate or methanol confirmed these results (Fig. 2). Furthermore, no growth was observed on plates containing either formate or oxalate, which is catabolized through formate in organisms such as Oxalobacter formigenes (1). Addition of either methanol or formaldehyde to succinate plates only slightly inhibited CM216K.1, in contrast to the severe inhibition effect observed for mutant strains defective for the H4MPT pathway (14, 27, 30, 42). The MICs of methanol and formaldehyde were found to be 125 and 0.5 mM, respectively, whereas the H4MPT pathway mutant defective for Fae, for example, was sensitive to 0.05 to 0.1 and 0.1 to 0.2 mM (27, 41). Similarly, growth in liquid medium was not affected by the addition of 125 mM methanol (Fig. 2). These data are consistent with the preliminary analysis of the ftfL::ISphoA/hah mutants (30) and are the first demonstration that FtfL activity is required for growth on C1 compounds. Furthermore, these data suggest that the H4F pathway may play a minor role, if any, in formaldehyde oxidation or detoxification.

FIG. 2.

Growth of wild-type M. extorquens AM1 (filled symbols) and the ftfL mutant CM216K.1 (open symbols) pregrown in succinate, harvested, and resuspended in media containing succinate (squares), succinate with methanol added to 125 mM at 2 h (triangles), or methanol (diamonds).

The FtfL-deficient mutant is not complemented by the expression of the GSH-dependent formaldehyde oxidation pathway.

The C1− and methanol-sensitive mutant phenotype of mutants defective for the H4MPT pathway in M. extorquens AM1 can be complemented by the heterologous expression of enzymes for the glutathione (GSH)-dependent formaldehyde oxidation pathway of Paracoccus denitrificans (27). This result suggested that the H4MPT pathway is required for formaldehyde oxidation and detoxification and called into question whether the endogenous H4F pathway significantly contributes to these functions. In order to determine whether the C1− mutant phenotype of the ftfL mutant is also due to defective formaldehyde oxidation, the pCM106 plasmid that expresses the GSH pathway was introduced into CM216K.1. The presence of pCM106 did not alter the mutant phenotypes (data not shown). Again, this result is inconsistent with the hypothesis that the H4F pathway may be required for the oxidation of formaldehyde to formate.

Mutants defective for both the H4F and H4MPT pathways are not more sensitive to methanol or formaldehyde than mutants solely lacking the H4MPT pathway.

As a second physiological test of the hypothesis that the H4F pathway is required for a role other than net formaldehyde oxidation to formate, mutants were generated that were defective for both the H4F and the H4MPT pathways to determine whether the double mutants would exhibit a more severe physiological defect than either single mutant alone. The H4MPT pathway was interrupted at two levels: at fae, which encodes the enzyme that generates methylene-H4MPT (42), and at dmrA, which encodes the putative dihydromethanopterin reductase (30). The fae mutant was shown to possess limited ability for oxidation of formaldehyde through the H4MPT pathway, via the nonenzymatic condensation (42), while dmrA mutant does not produce H4MPT (S. Wyles and M. E. Rasche, personal communication) and therefore should not possess H4MPT pathway activity (30). Double Δfae ΔftfL::kan (CM198-216K.1) and ΔftfL ΔdmrA::kan (CM216-212K.1) mutants were generated. Phenotypes of these mutants were compared to those of the single mutants CM198K.1 (28) and CM212K.1 (30) defective for fae and dmrA, respectively, on solid succinate medium containing a range of methanol or formaldehyde concentrations. The strains CM198K.1 and CM198-216K.1 were found to be equally sensitive (MIC of 10 μM methanol or 100 μM formaldehyde), as was true for the pair CM212K.1 and CM216-212K.1 (MIC of 1 μM methanol or 10 μM formaldehyde). These data provide additional evidence that the H4F pathway does not play a significant role in formaldehyde oxidation.

FtfL mutants generated [14C]CO2 from [14C]methanol at wild-type rates, whereas an H4MPT pathway mutant showed a reduced capacity.

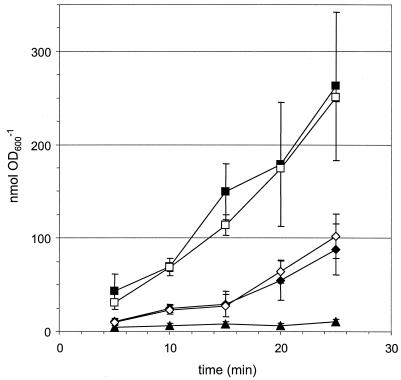

As a final test of whether the H4F pathway contributes significantly to net formaldehyde oxidation, mutants were analyzed for the ability to oxidize [14C]methanol to [14C]CO2 (Fig. 3). As a control, the ΔmxaF::kan strain CM194K.1 (27) was analyzed and found to produce no detectable [14C]CO2, consistent with its lesion in methanol dehydrogenase. CM216K.1 produced [14C]CO2 at a rate similar to the wild type. However, there was a significant lag of 10 to 15 min for the dmrA mutant CM212K.1 before [14C]CO2 could be detected. These data provide additional support for the model in which the H4MPT pathway, and not the H4F pathway, is primarily responsible for formaldehyde oxidation. In order to determine whether the H4F pathway was responsible for the CO2 production that occurred after a time lag in the H4MPT-deficient strain CM212K.1, the strain CM216-212K.1, defective for both ftfL and dmrA, was investigated. CO2 production by this strain was similar to that of CM212K.1. These data, again, do not support a role for the H4F pathway in formaldehyde oxidation, even in the absence of the H4MPT pathway. The likely source(s) to contribute to formaldehyde oxidation capacity in the absence of the H4MPT pathway is discussed below.

FIG. 3.

Whole-cell production of [14C]CO2 from [14C]methanol. Strains examined are wild type (filled squares), the dmrA mutant CM212K.1 (filled diamonds), the ftfL mutant CM216K.1 (open squares), the ftfL dmrA double mutant CM216-212K.1 (open diamonds), and the mxaF mutant CM194K.1 (filled triangles).

DISCUSSION

We have determined that the overall chemical, physical, and enzymatic properties of the FtfL purified from the serine cycle methylotroph M. extorquens AM1 appear to be very similar to those of the FtfL enzymes characterized previously from gram-positive bacteria. Not surprisingly, the predicted amino acid sequence of the M. extorquens AM1 FtfL is highly similar to these other sequences, and all amino acids suspected to be involved in substrate binding (36) are conserved. The phenotype of the ΔftfL::kan mutant strain provides firm evidence of the requirement for FtfL activity during methylotrophic growth of M. extorquens AM1.

So far, it has not been possible to isolate null mutants defective for the H4F pathway enzymes MtdA and Fch, even on medium containing succinate, in contrast to results described here for FtfL (10, 11, 34). The facts that null mutants could be obtained in FtfL and the resulting ftfL mutant strains exhibited wild-type growth characteristics on succinate indicate that a complete H4F pathway is not required for growth on multicarbon compounds. This is consistent with the hypothesis that the apparent requirement for MtdA and Fch during growth on multicarbon compounds is due to their role in generating formyl-H4F for the cell's biosynthetic needs. Unlike the mtdA and fch mutant strains described previously that contained low levels of the respective enzymes, the ftfL mutant is a null mutant in which the interconversion of methylene-H4F and formate is completely blocked, allowing for a more straightforward interpretation of the role of this pathway in methylotrophy.

In this study we demonstrated that the ftfL mutants, which are blocked in the H4F-linked interconversion of methylene-H4F and formate, have a phenotype different from that of mutants in the H4MPT-linked pathway: they are not sensitive to formaldehyde-producing substrates, and they are not complemented by the expression of the heterologous GSH pathway for formaldehyde oxidation. Furthermore, the methanol sensitivity of H4MPT pathway mutant strains was not exacerbated by an additional mutation blocking the H4F pathway. Finally, in addition to these physiological data suggesting that the H4F pathway is not required for formaldehyde oxidation, the conversion of [14C]methanol to [14C]CO2 was directly tested in mutant strains blocked in one or both of the pterin-linked pathways. Whereas the dmrA mutant and the ftfL dmrA double mutant showed a significant delay in [14C]CO2 production, the ftfL mutant exhibited wild-type conversion of methanol to CO2. These biochemical data provide further evidence that the H4F pathway does not contribute significantly to formaldehyde oxidation.

The likely source(s) of the remaining formaldehyde oxidation capacity in the mutant strain blocked for both the H4F and H4MPT pathways may be other aldehyde dehydrogenases that are present in M. extorquens AM1 (17, 43). These are neither specific for formaldehyde nor induced during growth on methanol and, in the one case in which an enzyme was purified, the Km for formaldehyde was 3.85 mM (17), suggesting that these enzymes are not specific for methylotrophy. Previous calculations, however, indicated that the intracellular concentration of this toxic intermediate would rise to 100 mM in less than a minute if methanol oxidation proceeded in the absence of subsequent formaldehyde oxidation (3, 42). It is possible, therefore, that the lag observed in the CO2 production by strains lacking the H4MPT pathway corresponds to the time required for the intracellular formaldehyde to rise to a sufficiently high concentration to allow the low-affinity aldehyde dehydrogenases to function at a measurable level. Alternatively, the formaldehyde may also be accumulating in the periplasm under these conditions, where it may be oxidized by methanol dehydrogenase itself (15). In either case it remained remarkable that, under these conditions that likely correspond to a significantly elevated formaldehyde concentration, the presence or absence of an intact H4F pathway did not alter the kinetics of formaldehyde oxidation.

One role that has been suggested for the H4F pathway in serine cycle methylotrophs is that it functions in the reductive direction, generating methylene-H4F during growth on formate, thereby providing the means to assimilate carbon during growth on this substrate (18). In contrast to strains defective for the H4MPT pathway (27), ftfL mutant strains failed to grow on formate, confirming the role of this pathway in formate utilization. Additionally, ftfL mutants were defective for growth on oxalate, which is converted to formate in other organisms that grow on this compound through the action of oxalyl-coenzyme A (CoA) decarboxylase (6) and formyl-CoA transferase (5). Consistent with this model for growth of M. extorquens AM1 on oxalate, mutants lacking one of the two putative formyl-CoA transferases found in the genome sequence (www.integratedgenomics.com/genomereleases.html#list6) fail to grow on oxalate (C. J. Marx and M. E. Lidstrom, unpublished data). Interestingly, the initial assimilatory reactions during the growth of serine cycle methylotrophs on formate mirror the initial steps of the Wood-Ljungdahl pathway utilized by acetogenic bacteria (23), with both classes of organisms utilizing FtfL to activate formate for further assimilation.

The data presented in this paper clearly demonstrate that the complete H4F pathway is required for methylotrophic growth of M. extorquens AM1, but they contradict the previous suggestion that serine cycle methylotrophs may oxidize formaldehyde via the H4F-linked C1 transfer pathway (26). Our data are consistent, however, with an alternative hypothesis (32, 39) that a fraction of the formate produced by the H4MPT pathway may be assimilated via the reductive H4F pathway. In accordance with this hypothesis, the H4F pathway would function as a second route for the production of methylene-H4F, the starting substrate for the serine cycle, in addition to the nonenzymatic condensation of formaldehyde with H4F.

Acknowledgments

We thank L. Chistoserdova, M. G. Kalyuzhnaya, N. Korotkova, H. M. Rothfuss, and S. Stolyar for their helpful comments and suggestions.

This work was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (GM 36296), the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, the Max-Planck-Gesellschaft, and the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anantharam, V., M. J. Allison, and P. C. Maloney. 1989. Oxalate:formate exchange, the basis for energy coupling in Oxalobacter. J. Biol. Chem. 264:7244-7250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Attwood, M. M., and W. Harder. 1972. A rapid and specific enrichment procedure for Hyphomicrobium spp. Antonie Leeuwenhoek 38:369-377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Attwood, M. M., and J. R. Quayle. 1984. Formaldehyde as a central intermediary metabolite of methylotrophic metabolism, p. 315-323. In R. L. Crawford and R. S. Hanson (ed.), Microbial growth on C1 compounds. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C.

- 4.Auman, A. J., S. Stolyar, A. M. Costello, and M. E. Lidstrom. 2000. Molecular characterization of methanotrophic isolates from freshwater lake sediment. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:5259-5266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baetz, A. L., and M. J. Allison. 1990. Purification and characterization of formyl-coenzyme A transferase from Oxalobacter formigenes. J. Bacteriol. 172:3537-3540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baetz, A. L., and M. J. Allison. 1989. Purification and characterization of oxalyl-coenzyme A decarboxylase from Oxalobacter formigenes. J. Bacteriol. 171:2605-2608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bradford, M. M. 1976. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 72:248-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chistoserdov, A. Y., L. V. Chistoserdova, W. S. McIntire, and M. E. Lidstrom. 1994. Genetic organization of the mau gene cluster in Methylobacterium extorquens AM1: complete nucleotide sequence and generation and characteristics of mau mutants. J. Bacteriol. 176:4052-4065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chistoserdova, L., J. A. Vorholt, R. K. Thauer, and M. E. Lidstrom. 1998. C1 transfer enzymes and coenzymes linking methylotrophic bacteria and methanogenic Archaea. Science 281:99-102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chistoserdova, L. V., and M. E. Lidstrom. 1994. Genetics of the serine cycle in Methylobacterium extorquens AM1: identification of sgaA and mtdA and sequences of sgaA, hprA, and mtdA. J. Bacteriol. 176:1957-1968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chistoserdova, L. V., and M. E. Lidstrom. 1994. Genetics of the serine cycle in Methylobacterium extorquens AM1: identification, sequence, and mutation of three new genes involved in C1 assimilation, orf4, mtkA, and mtkB. J. Bacteriol. 176:7398-7404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Donnelly, M. I., J. C. Escalante-Semerena, K. L. Rinehart, Jr., and R. S. Wolfe. 1985. Methenyl-tetrahydromethanopterin cyclohydrolase in cell extracts of Methanobacterium. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 242:430-439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Figurski, D. H., and D. R. Helinski. 1979. Replication of an origin-containing derivative of plasmid RK2 dependent on a plasmid function provided in trans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 76:1648-1652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hagemeier, C. H., L. Chistoserdova, M. E. Lidstrom, R. K. Thauer, and J. A. Vorholt. 2000. Characterization of a second methylene tetrahydromethanopterin dehydrogenase from Methylobacterium extorquens AM1. Eur. J. Biochem. 267:3762-3769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heptinstall, J., and J. R. Quayle. 1969. A mutant of Pseudomonas AM-1 which lacks methanol dehydrogenase activity. J. Gen. Microbiol. 55:xvi-xvii. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Himes, R. H., and J. C. Rabinowitz. 1962. Formyltetrahydrofolate synthetase. III. Studies on the mechanism of the reaction. J. Biol. Chem. 237:2915-2925. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johnson, P. A., and J. R. Quayle. 1964. Microbial growth on C1 compounds. 6. Oxidation of methanol, formaldehyde and formate by methanol-grown Pseudomonas AM1. Biochem. J. 93:281-290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Large, P. J., D. Peel, and J. R. Quayle. 1961. Microbial growth on C1 compounds. 2. Synthesis of cell constituents by methanol- and formate-grown Pseudomonas AM1, and methanol-grown Hyphomicrobium vulgare. Biochem. J. 81:470-479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Large, P. J., and J. R. Quayle. 1963. Microbial growth on C1 compounds. 5. Enzyme activities in extracts of Pseudomonas AM1. Biochem. J. 87:383-396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Laukel, M., L. Chistoserdova, M. E. Lidstrom, and J. A. Vorholt. 2003. The tungsten-containing formate dehydrogenase from Methylobacterium extorquens AM1: purification and properties. Eur. J. Biochem. 270:325-333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lidstrom, M. E. 2 November 2001, posting date. Aerobic methylotrophic prokaryotes. In M. Dworkin (ed.), Prokaryotes. [Online.] http://link.springer.de/link/service/books/10125/.

- 22.Lidstrom, M. E., and L. Somers. 1984. Seasonal study of methane consumption in Lake Washington. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 47:1255-1260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ljungdahl, L. G. 1986. The autotrophic pathway of acetate synthesis in acetogenic bacteria. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 40:415-450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.MacKenzie, R. E. 1984. Biogenesis and interconversion of substituted tetrahydrofolates, p. 255-306. In R. L. Blakley and S. J. Bankovic (ed.), Folates and pterins, vol. 1. John Wiley & Sons, New York, N.Y.

- 25.MacKenzie, R. E., and J. C. Rabinowitz. 1971. Cation-dependent reassociation of subunits of N10-formyltetrahydrofolate synthetase from Clostridium acidi-urici and Clostridium cylindrosporum. J. Biol. Chem. 246:3731-3736. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marison, I. W., and M. M. Attwood. 1982. A possible alternative mechanism for the oxidation of formaldehyde to formate. J. Gen. Microbiol. 128:1441-1446. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marx, C. J., L. Chistoserdova, and M. E. Lidstrom. Formaldehyde detoxifying role of the tetrahydromethanopterin-linked pathway in Methylobacterium extorquens AM1. J. Bacteriol. 185:3614-3622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Marx, C. J., and M. E. Lidstrom. 2002. Broad-host-range cre-lox system for antibiotic marker recycling in gram-negative bacteria. BioTechniques 33:1062-1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marx, C. J., and M. E. Lidstrom. 2001. Development of improved versatile broad-host-range vectors for use in methylotrophs and other gram-negative bacteria. Microbiology 147:2065-2075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marx, C. J., B. N. O'Brien, J. Breezee, and M. E. Lidstrom. 2003. Novel methylotrophy genes of Methylobacterium extorquens AM1 identified by using transposon mutagenesis including a putative dihydromethanopterin reductase. J. Bacteriol. 185:669-673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nunn, D. N., and M. E. Lidstrom. 1986. Isolation and complementation analysis of 10 methanol oxidation mutant classes and identification of the methanol dehydrogenase structural gene of Methylobacterium sp. strain AM1. J. Bacteriol. 166:581-590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pomper, B. K., O. Saurel, A. Milon, and J. A. Vorholt. 2002. Generation of formate by the formyltransferase/hydrolase complex (Fhc) from Methylobacterium extorquens AM1. FEBS Lett. 523:133-137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pomper, B. K., and J. A. Vorholt. 2001. Characterization of the formyltransferase from Methylobacterium extorquens AM1. Eur. J. Biochem. 268:4769-4775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pomper, B. K., J. A. Vorholt, L. Chistoserdova, M. E. Lidstrom, and R. K. Thauer. 1999. A methenyl tetrahydromethanopterin cyclohydrolase and a methenyl tetrahydrofolate cyclohydrolase in Methylobacterium extorquens AM1. Eur. J. Biochem. 261:475-480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rabinowitz, J. C., and W. E. Pricer, Jr. 1963. Formyltetrahydrofolate synthetase. Methods Enzymol. 6:375-379. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Radfar, R., R. Shin, G. M. Sheldrick, W. Minor, C. R. Lovell, J. D. Odom, R. B. Dunlap, and L. Lebioda. 2000. The crystal structure of N10-formyltetrahydrofolate synthetase from Moorella thermoacetica. Biochemistry 39:3920-3926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 38.Simon, R., U. Priefer, and A. Puhler. 1983. A broad host range mobilization system for in vivo genetic engineering: transposon mutagenesis in gram negative bacteria. Bio/Technology 1:784-791. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vorholt, J. A. 2002. Cofactor-dependent pathways of formaldehyde oxidation in methylotrophic bacteria. Arch. Microbiol. 178:239-249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vorholt, J. A., L. Chistoserdova, M. E. Lidstrom, and R. K. Thauer. 1998. The NADP-dependent methylene tetrahydromethanopterin dehydrogenase in Methylobacterium extorquens AM1. J. Bacteriol. 180:5351-5356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vorholt, J. A., L. Chistoserdova, S. M. Stolyar, R. K. Thauer, and M. E. Lidstrom. 1999. Distribution of tetrahydromethanopterin-dependent enzymes in methylotrophic bacteria and phylogeny of methenyl tetrahydromethanopterin cyclohydrolases. J. Bacteriol. 181:5750-5757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vorholt, J. A., C. J. Marx, M. E. Lidstrom, and R. K. Thauer. 2000. Novel formaldehyde-activating enzyme in Methylobacterium extorquens AM1 required for growth on methanol. J. Bacteriol. 182:6645-6650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Weaver, C. A., and M. E. Lidstrom. 1985. Methanol dissimilation in Xanthobacter H4-14: activities, induction and comparison to Pseudomonas AM1 and Paracoccus denitrificans. J. Gen. Microbiol. 131:2183-2197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]