Abstract

Phosphatidyl-myo-inositol mannosides (PIMs) are unique glycolipids found in abundant quantities in the inner and outer membranes of the cell envelope of all Mycobacterium species. They are based on a phosphatidyl-myo-inositol lipid anchor carrying one to six mannose residues and up to four acyl chains. PIMs are considered not only essential structural components of the cell envelope but also the structural basis of the lipoglycans (lipomannan and lipoarabinomannan), all important molecules implicated in host-pathogen interactions in the course of tuberculosis and leprosy. Although the chemical structure of PIMs is now well established, knowledge of the enzymes and sequential events leading to their biosynthesis and regulation is still incomplete. Recent advances in the identification of key proteins involved in PIM biogenesis and the determination of the three-dimensional structures of the essential phosphatidyl-myo-inositol mannosyltransferase PimA and the lipoprotein LpqW have led to important insights into the molecular basis of this pathway.

Keywords: Bacterial Metabolism, Cell Wall, Glycerophospholipid, Lipid Synthesis, Membrane Enzymes, Mycobacterium, Glycosyltransferase, Phosphatidylinositol Mannosides, Tuberculosis

Introduction

myo-Inositol, as a phospholipid constituent, was first reported in mycobacteria by R. J. Anderson in 1930 (1). Subsequently, the presence of phosphatidyl-myo-inositol (PI)3 dimannosides (PIM2) and PI pentamannosides (PIM5) was recognized in Mycobacterium tuberculosis (2, 3). Over the past 40 years, the structure of the complete family of PI mannosides (PIM1–PIM6) in various Mycobacterium spp. and related Actinomycetes has been defined, first as deacylated glycerophosphoryl-myo-inositol mannosides and later as the fully acylated native molecules (4).

PIMs and metabolically related lipoglycans comprising lipomannan (LM) and lipoarabinomannan (LAM) are noncovalently anchored through their PI moiety to the inner and outer membranes of the cell envelope (5, 6) and play various essential although poorly defined roles in mycobacterial physiology. They are also thought to be important virulence factors during the infection cycle of M. tuberculosis. Aided by the availability of a growing number of genome sequences from lipoglycan-producing Actinomycetes, developments in the genetic manipulation of these organisms, and advances in our understanding of the molecular processes underlying sugar transfer in Corynebacterianeae, considerable progress was made over the last 10 years in identifying the enzymes associated with the biogenesis of PIM, LM, and LAM (for recent review, see Refs. 7 and 8). The precise chemical definition of these molecules from various Actinomycetes combined with comparative analyses of their interactions with the host immune system also has shed light on their structure-function relationships (9).

In this minireview, we present some key enzymatic, structural, and topological aspects of the biogenesis of PIMs, a pathway that may represent a paradigm for that of other mycobacterial complex (glyco)lipids. The elucidation of this pathway has helped in our understanding of the pathogenesis of tuberculosis and revealed new opportunities for drug discovery.

Chemical Structure of PIMs: An Overview

The PIM family of glycolipids comprises PI mono-, di-, tri-, tetra-, penta-, and hexamannosides with different degrees of acylation. PIM2 and PIM6 are the two most abundant classes found in Mycobacterium bovis bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG), M. tuberculosis H37Rv, and Mycobacterium smegmatis 607 (10). The presence of myo-inositol and mannose as sugar constituents of phospholipids from M. tuberculosis was first reported by Anderson in the 1930s (1, 11–13). Using similar approaches 25 years later, Lee and Ballou arrived at a complete structure of PIM2 from M. tuberculosis and Mycobacterium phlei and provided evidence of the existence of mono-, tri-, tetra-, and pentamannoside variants (2, 3, 14, 15). A reanalysis of PIMs from M. smegmatis in their deacylated form later revealed a structure based on that previously defined by Ballou et al. but containing six Manp residues (PIM6) (16). The complete chemical structures of the acylated native forms of PIM2 and PIM6 were later reinvestigated in M. bovis BCG and unequivocally established (Fig. 1A) (10, 17). PIM2 is composed of two Manp residues attached to positions 2 and 6 of the myo-inositol ring of PI. PIM6 is composed of a pentamannosyl group, t-α-Manp(1→2)-α-Manp(1→2)-α-Manp(1→6)-α-Manp(1→6)-α-Manp(1→, attached to position 6 of the myo-inositol ring, in addition to the Manp residue present at position 2 (Fig. 1A). Brennan and Ballou (18) initially found that PIM2 occurs in multiple acylated forms, where two fatty acids are attached to the glycerol moiety, and two additional fatty acids may esterify available hydroxyls on the Manp residue and/or the myo-inositol ring (Fig. 1A). The tri- and tetraacylated forms of PIM2 and PIM6 (Ac1PIM2/Ac2PIM2 and Ac1PIM6/Ac2PIM6) are the most abundant. Ac1PIM2 and Ac1PIM6 from M. bovis BCG show major acyl forms containing two palmitic acid residues (C16) and one tuberculostearic acid residue (10-methyloctadecanoate, C19), where one fatty acyl chain is linked to the Manp residue attached to position 2 of myo-inositol, and two fatty acyl chains are located on the glycerol moiety. The tetraacylated forms, Ac2PIM2 and Ac2PIM6, are present predominantly as two populations bearing either three C16/one C19 or two C16/two C19 (10, 17). Mass spectrometry analyses have led to the conclusion that the glycerol moiety is preferentially acylated with C16/C19. Other acylation positions are C3 of the myo-inositol unit and C6 of Manp linked to C2 of myo-inositol.

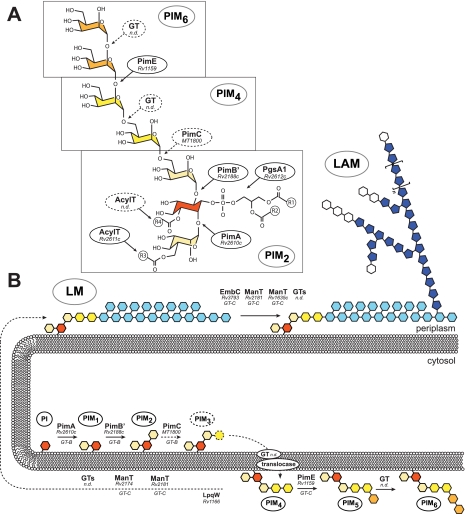

FIGURE 1.

Proposed model for PIM biosynthesis and regulation. A, chemical structure of PIM. One Manp residue (in beige) is attached to position 2 of myo-inositol (in red), whereas the total number of Manp residues attached to position 6 may range from zero to five. In PIM2, the myo-inositol ring is glycosylated with a Manp unit at each of positions 2 and 6 (beige). In PIM4, a dimannosyl unit, t-α-Manp(1→6)-α-Manp(1→6) (yellow), further extends the Manp linked to position 6 of the myo-inositol ring of PIM2. PIM6 results from the elongation of PIM4 by the dimannosyl unit t-α-Manp(1→2)-α-Manp(1→2) (orange). AcylT, acyltransferase; n.d., not determined. B, topology model for the biosynthesis of PIMs, LM, and LAM in mycobacteria. See text for details. The precise identity of the PIM intermediate(s) translocated from the cytosolic to the periplasmic side of the plasma membrane, whether (Ac1/2)PIM2, (Ac1/2)PIM3, or (Ac1/2)PIM4, remains to be determined. The biosynthesis of PIMs takes place on both sides of the inner membrane. Synthesis is initiated on the cytoplasmic side, where Manp is transferred from GDP-Manp to PI, followed by one to three additional Manp residues. On the periplasmic side, the mannolipid is extended by additional Manp residues up to PIM6. The enzymes involved belong to the GT-C fold family of GTs, which are predicted to have between 8 and 13 transmembrane α-helices with the active site located on an extracytoplasmic loop. Subsequent mannosylation and arabinosylation steps in LM and LAM biosynthesis (light blue, Manp residues; dark blue, Araf residues; white, Manp-capping residues) are thought to all take place on the periplasmic side of the plasma membrane, requiring polyprenyl-phosphate-sugar donors. As an important part of the literature on the biosynthesis of PIM, LM, and LAM refers to the M. tuberculosis H37Rv genes, the Rv numbers of the proteins required for the different catalytic steps of the pathway are indicated. The M. tuberculosis CDC1551 nomenclature was used in the case of pimC (MT1800), as this gene lacks an ortholog in H37Rv.

Suggestive of a metabolic relationship, the reducing end of LM and LAM shares structural similarities with PIMs in that the myo-inositol residues of the PI of PIMs, LM, and LAM are mannosylated at positions 2 and 6, and similar fatty acyl chains esterify the glycerol moiety, Manp linked to C2 of myo-inositol, and the myo-inositol ring (16, 19–21).

PIM2 Biosynthesis

Ac1PIM2 and Ac2PIM2 are considered both metabolic end products and intermediates in the biosynthesis of Ac1PIM6/Ac2PIM6, LM, and LAM. According to the currently accepted model, PIM synthesis is initiated by the transfer of two Manp residues and one fatty acyl chain onto PI on the cytosolic face of the plasma membrane. The first step consists of the transfer of a Manp residue from GDP-Manp to position 2 of the myo-inositol ring of PI to form PI monomannoside (PIM1) (Fig. 1, A and B) (15). On the basis of genetic, enzymatic, and structural evidence, we identified PimA from M. smegmatis (orthologous to Rv2610c of M. tuberculosis H37Rv) as the α-mannosyltransferase (α-ManT) responsible for this catalytic step and found this enzyme to be essential for the growth of M. smegmatis mc2155 and M. tuberculosis (22, 23).4 The second step involves the action of the α-ManT PimB′ (Rv2188c), also an essential enzyme of M. smegmatis, which transfers a Manp residue from GDP-Manp to position 6 of the myo-inositol ring of PIM1 (23, 24). The essential character of both PimA and PimB′ validates these enzymes as therapeutic targets worthy of further development.

Both PIM1 and PIM2 can be acylated with palmitate at position 6 of the Manp residue transferred by PimA by the acyltransferase Rv2611c to form Ac1PIM1 and Ac1PIM2, respectively. The disruption of Rv2611c abolishes the growth of M. tuberculosis and severely alters that of M. smegmatis particularly at low NaCl concentrations and when detergent (Tween 80) is present in the culture medium (25).4 Based on cell-free assays, two models were originally proposed for the biosynthesis of Ac1PIM2 in mycobacteria. In the first model, PI is mannosylated to form PIM1. PIM1 is then further mannosylated to form PIM2, which is acylated to form Ac1PIM2. In the second model, PIM1 is first acylated to Ac1PIM1 and then mannosylated to Ac1PIM2. Recent cell-free assays using pure enzymes alone or in combination with M. smegmatis membrane extracts indicated that although both pathways might co-exist in mycobacteria, the sequence of events PI → PIM1 → PIM2 → Ac1PIM2 is favored (23). The acyltransferase responsible for the transfer of a fourth acyl group to position 3 of the myo-inositol ring has not yet been identified.

A major advance in our understanding of the molecular basis of the biosynthesis of the PIM2 family was provided by the structural characterization of PimA from M. smegmatis mc2155 (26). PimA is not only a key player in the biosynthetic pathway of PIM but also a paradigm of a large family of peripheral membrane-associated glycosyltransferases (GTs), the molecular mechanisms of substrate/membrane recognition and catalysis of which are poorly understood. The PimA enzyme, which belongs to the ubiquitous GT4 family of retaining GTs (CAZy (Carbohydrate-Active enZYmes) Database), displays the typical GT-B fold of GTs (Fig. 2A) (26, 27). The crystal structure of a PimA·GDP-Manp complex revealed that the enzyme adopts a “closed” conformation in the presence of GDP-Manp, with the GDP moiety of the sugar donor substrate making binding interactions predominantly with the C-terminal domain of the protein (Fig. 2B). The three-dimensional structure also provided clear insights into the architecture of the lipid acceptor-binding site. Docking calculations and site-directed mutagenesis validated the position of the polar head of the lipid acceptor, myo-inositol phosphate, in a well defined pocket with its O2 atom favorably positioned to receive the Manp residue from GDP-Manp (Fig. 2B) (28).

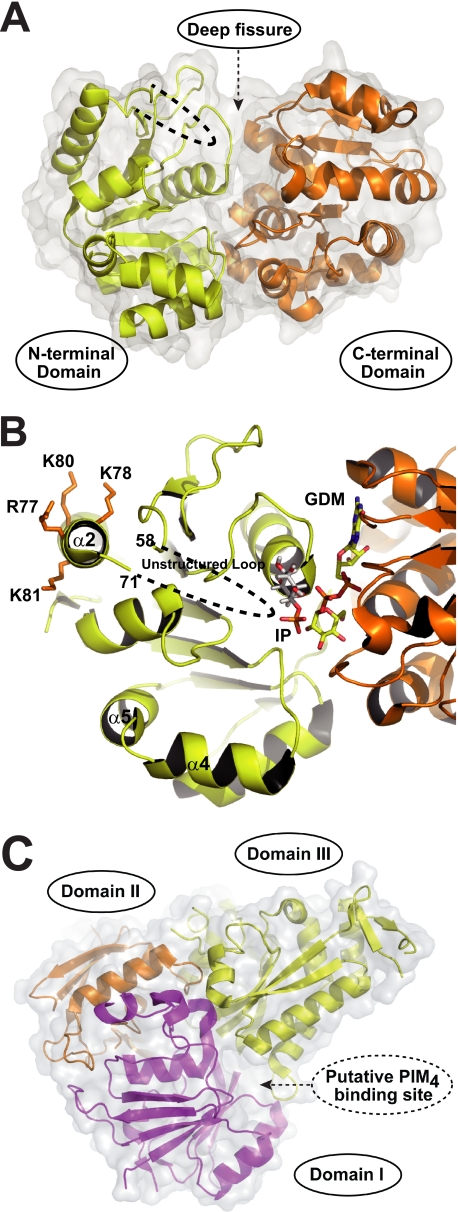

FIGURE 2.

Structural basis of PimA and LpqW. A, overall structure of PimA. The enzyme (42.3 kDa; shown in A and B in its closed conformation) displays the typical GT-B fold of GTs, consisting of two Rossmann fold domains with a deep fissure at the interface that includes the catalytic center. Met1–Gly169 and Trp349–Ser373 form the N-terminal domain of the protein (in yellow), whereas the C-terminal domain consists of Val170–Asp348 (in orange). The core of each domain is composed of seven parallel β-strands alternating with seven connecting α-helices. Two regions of the structure have poor or no electron density, indicating conformational flexibility. The conserved connecting loop β3–α2 (residues 59–70) within the N-terminal domain and the C-terminal extension of the protein (residues 374–386) that is missing in other mycobacterial PimA homologs is shown as dashed lines. B, model of action for PimA. See text for details. The secondary structure of a selected region of PimA (in a different orientation than in A) including the GDP-Manp (GDM)- and myo-inositol phosphate (IP)-binding sites and the amphipathic α2 helix involved in membrane association is shown. Membrane attachment is mediated by an interfacial binding surface on the N-terminal domain of the protein, which likely includes a cluster of basic residues and the adjacent exposed loop β3–α2. Protein-membrane interactions stimulate catalysis by facilitating substrate diffusion from the lipid bilayer to the catalytic site and/or by inducing allosteric changes in the protein. C, overall structure and proposed mode of action for LpqW. LpqW is predicted to be a monomeric membrane-associated lipoprotein composed of 600 amino acids (62.9 kDa). The crystal structure revealed that the protein is organized in two lobes. Three structural domains (I, II, and III) can be identified, with domains I (magenta) and II (orange) representing the “lower” lobe (lobe 1) and domain III (yellow) representing the “upper” lobe (lobe 2). Although the structure of LpqW was determined in the non-liganded state, the major periplasmic component of PIM4 (t-α-Manp(1→6)-α-Manp(1→6)) was accommodated by using in silico docking. It is proposed that LpqW functions at the divergence point of the polar PIM and LM/LAM biosynthetic pathways to control the relative abundance of these species in the mycobacterial cell envelope.

More recently, experimental evidence based on structural, calorimetric, mutagenesis, and enzyme activity studies indicated that PimA undergoes significant conformational changes upon substrate binding that seem to be important for catalysis. Specifically, the binding of the donor substrate, GDP-Manp, triggered an important interdomain rearrangement from an “open” to a closed state that stabilized the enzyme and considerably enhanced its affinity for the acceptor substrate, PI. The interaction of PimA with the β-phosphate of GDP-Manp was essential for this conformational change to occur. The open-to-closed motion brings together critical residues from the N- and C-terminal domains, allowing the formation of a functionally competent active site. In contrast, the binding of PI to the enzyme had the opposite effect, inducing the formation of a more relaxed complex with PimA. It could be speculated that PI binding allows the initiation of the enzymatic reaction and induces the “opening” of the protein, allowing the product to be released. Interestingly, GDP-Manp stabilized and PI destabilized PimA by a similar enthalpic amount, suggesting that they form or disrupt an equivalent number of interactions within PimA complexes. Altogether, our experimental data support a model wherein flexibility and conformational transitions confer upon PimA the adaptability to the donor and acceptor substrates required for catalysis (28). In this regard, PimA thus seems to follow an ordered mechanism similar that reported for other GT-B enzymes (29, 30).

Another key aspect of the mode of action of PimA is its interaction with membranes. To perform their biochemical functions, membrane-associated GTs interact with membranes by two different mechanisms. Whereas integral membrane GTs are permanently attached through transmembrane regions (e.g. hydrophobic α-helices) (31), peripheral membrane-associated GTs temporarily bind membranes by (i) a stretch of hydrophobic residues exposed to bulk solvent, (ii) electropositive surface patches that interact with acidic phospholipids (e.g. amphipathic α-helices), and/or (iii) protein-protein interactions (32–35). A close interaction of the α-ManTs PimA and PimB′ with membranes is likely to be a strict requirement for PI/PIM modification. Consistent with this hypothesis, the membrane association of PimA via electrostatic interactions is suggested by the presence of an amphipathic α-helix and surface-exposed hydrophobic residues in the N-terminal domain of the protein (Fig. 2B). Despite the fact that sugar transfer is catalyzed between the mannosyl group of the GDP-Manp donor and the myo-inositol ring of PI, the enzyme displayed an absolute requirement for both fatty acid chains of the acceptor substrate in order for the transfer reaction to take place. Most importantly, although PimA was able to bind monodisperse PI, its transferase activity was stimulated by high concentrations of non-substrate anionic surfactants, indicating that the reaction requires a lipid-water interface (26). Interestingly, critical residues and their interactions are preserved in PimA and PimB′, strongly supporting conserved catalytic and membrane association mechanisms (23).

Biosynthesis of PIM5, PIM6, LM, and LAM

Ac1PIM2 and Ac2PIM2 can be further elongated with additional Manp residues to form higher PIM species (such as Ac1PIM3–Ac1PIM6/Ac2PIM3–Ac2PIM6), LM, and LAM (Fig. 1B). It has been proposed that the third Manp residue of PIM is added to Ac1PIM2 by the nonessential GDP-Manp utilizing α-ManT PimC, identified in the genome of M. tuberculosis CDC1551 (36). However, this enzyme is absent from other mycobacterial genomes (e.g. M. smegmatis and M. tuberculosis H37Rv), suggesting the existence of an alternative pathway. Likewise, the α-ManT (PimD) that catalyzes the transfer of the fourth Manp residue onto PI trimannosides remains to be identified. Ac1PIM4/Ac2PIM4 seems to be a branch point intermediate in Ac1PIM6/Ac2PIM6 and LM/LAM biosynthesis. The addition of two α-1,2-linked Manp residues to Ac1PIM4/Ac2PIM4, a combination not found in the mannan backbone of LM and LAM, leads to the formation of the higher order mannosides Ac1PIM6 and Ac2PIM6 (31, 37, 38). PimE (Rv1159) has been recently identified as an α-1,2-ManT involved in the biosynthesis of higher order PIMs. PimE belongs to the GT-C superfamily of GTs, which comprises integral membrane proteins that use polyprenyl-linked sugars as donors (7, 8, 27, 31). A combination of phenotypic characterization of M. tuberculosis and M. smegmatis pimE knock-out mutants and cell-free assays clearly indicated that PimE transfers a Manp residue from polyprenol-phosphate-mannose to Ac1PIM4 to form Ac1PIM5 at the periplasmic face of the plasma membrane (Fig. 1, A and B) (31).4 The α-1,2-ManT responsible for the formation of PIM6 from PIM5 is not yet known.

A screening for M. smegmatis transposon mutants with defects in cell envelope synthesis led to the discovery of a mutant harboring an insertion in the putative lipoprotein-encoding gene lpqW (orthologous to Rv1166 of M. tuberculosis H37Rv). On complex media, the mutant formed small colonies that produced much reduced quantities of LAM compared with the wild-type parent strain. This phenotype was unstable, however, as the mutant rapidly evolved to give rise to variants that had restored LAM biosynthesis but failed to produce higher PIMs and accumulated the branch point intermediate Ac1PIM4 (39). Consistent with the accumulation of this intermediate, the restoration of LAM synthesis in the lpqW mutant was accounted for by secondary mutations in the pimE gene affecting the extracytoplasmic enzyme activity of this protein (40). From these findings, it was proposed that LpqW is required to channel PIM4 into LAM synthesis (Fig. 1B) and that loss of PimE, which results in the accumulation of high levels of Ac1PIM4 in the cells, bypasses the need for LpqW (40). The crystal structure of LpqW (41) revealed an overall fold (Fig. 2C) that resembles those of a family of bacterial substrate-binding proteins (42). A plausible model was suggested in which an electronegative interdomain cavity in LpqW might bind the Ac1PIM4 intermediate (Fig. 2C) to channel it into the LM/LAM biosynthetic pathway, thus controlling the relative abundance of higher PIMs and LM/LAM (Fig. 1B).

Compartmentalization of the PIM Biosynthetic Pathway and Translocation of PIMs across the Cell Envelope

As evidenced by the nature of the GTs and sugar donors involved and the asymmetrical PIM composition of the inner and outer leaflets of the mycobacterial plasma membrane (43), the biosynthesis of PIM, LM, and LAM is topologically complex. Whereas the first two mannosylation steps of the pathway at least involve GDP-Manp-dependent enzymes and occur on the cytoplasmic face of the plasma membrane (22, 23, 38, 43), further steps in the biosynthesis of the higher, more polar forms of PIMs (PIM5 and PIM6 in their various acylated forms) and metabolically related LM and LAM appear to rely upon integral membrane GT-C-type GTs and to take place on the periplasmic side of the membrane (Fig. 1B) (7, 31, 43, 44).4 Thus, similar to other M. tuberculosis glycolipids, such as sulfolipid-I and the linker unit of the mycobacterial cell wall (for a recent review, see Ref. 8), PIMs clearly display a compartmentalized biosynthetic pathway organized around the inner and outer leaflets of the plasma membrane. Such a compartmentalization implies the translocation of PIM intermediates (i.e. PIM2, PIM3, and/or PIM4) from the cytoplasmic to the periplasmic side of the membrane. Likewise, much like the lipid-linked oligosaccharides involved in the biosynthesis of bacterial (lipo)polysaccharides and peptidoglycan (45–47), it is expected that polyprenol-phosphate-mannose is translocated to the periplasmic side of the plasma membrane to serve as the Manp donor in the glycosyl transfer reactions catalyzed by PimE and subsequent GT-C-type ManTs of the PIM, LM, and LAM pathway. Beyond the plasma membrane, because two different populations of PIMs (one associated with the inner membrane and the other associated with the outer membrane) have been described (2, 48), transporters must exist that are responsible for their translocation across the periplasm and to the cell surface. None of the transporters involved in these processes have yet been identified.

Knowns and Unknowns of the Physiological Roles and Biological Activities of PIMs

The role of PIMs in the physiology of mycobacteria remains unclear. Because in M. bovis BCG PI and PIMs make up as much as 56% of all phospholipids in the cell wall and 37% of those in the plasma membrane, these molecules have long been thought to be essential structural components of the mycobacterial cell envelope (48). Drug susceptibility testing and uptake experiments with norfloxacin or chenodeoxycholate performed on recombinant M. smegmatis and M. tuberculosis strains affected in their polar or apolar PIM contents clearly implicated these glycolipids in the permeability of the cell envelope to both hydrophilic and hydrophobic molecules (22, 31, 49). Recent electron microscopy studies on a pimE-deficient mutant of M. smegmatis further pointed to a role of higher order PIMs in cell membrane integrity and in the regulation of cell septation and division (31). Somewhat supporting these observations, polar and apolar PIM production was reported to be affected by environmental factors known to impact replication rate and/or membrane fluidity, such as carbon/nitrogen sources and temperature (50, 51). The amount of higher order PIMs (PIM5 and PIM6) recovered from mycobacterial cells increases with the age of the culture, probably at the expense of the apolar forms (PIM1–PIM4), the synthesis of which was shown to decrease in M. smegmatis when cultures enter stationary phase (43, 52, 53). The regulatory mechanisms involved and the specific steps of the PIM pathway at which they act, whether exclusively at the level of LpqW or otherwise, are not known. Although higher order PIMs are dispensable molecules in M. smegmatis, M. bovis BCG, and M. tuberculosis (31, 54),4 such is not the case with PIM1 and PIM2, the disruption of which causes immediate growth arrest in both fast- and slow-growing mycobacteria (22, 23). Interestingly, we found the disruption of the acyltransferase Rv2611c to be lethal to M. tuberculosis H37Rv and to result in severe growth defects in M. smegmatis (25),4 emphasizing the critical physiological impact of not only the degree of mannosylation of PIMs but also their acylation state.

Much of what is known of the roles of PIMs in host-pathogen interactions is derived from in vitro studies using various cell models and purified PIM molecules or whole mycobacterial cells (for recent reviews, see Refs. 9 and 55–57). PIMs are major non-peptidic antigens of the host innate and acquired immune responses. They are TLR-2 agonists and stimulate unconventional αβ T-lymphocytes in the context of CD1 proteins. Importantly, PIMs are also recognized by the C-type lectins mannose receptor, mannose-binding protein, and DC-SIGN and, as such, play a role in the opsonic and non-opsonic binding of M. tuberculosis to phagocytic and non-phagocytic cells. The higher forms of PIMs in particular, which contain two α-1,2-linked Manp residues, identical to the dimannoside motif decorating the nonreducing termini of the arabinosyl side chains of mannosylated LAM, have been shown to share with mannosylated LAM the ability to engage the mannose and DC-SIGN receptors of phagocytic cells and, in so doing, to impact phagosome-lysosome fusion in cultured human monocyte-derived macrophages (54, 58). Both the fatty acyl appendages of PIMs and their degree of mannosylation are important to their interactions with host cells. However, a better understanding of their roles in the pathogenesis of tuberculosis would greatly benefit from the availability of M. tuberculosis mutants deficient in either their synthesis (wherever possible) or transport to the cell surface.

Concluding Remarks and Future Challenges

Considerable advances have been made over the last 10 years in understanding the genetics and biochemistry of PIM synthesis in M. tuberculosis. Foremost among these advances has been the structural characterization of PimA (in fact, the very first crystal structure of a GT involved in mycobacterial cell wall biosynthesis) and the proposal of a model for interpreting the conformational changes and membrane interactions associated with its catalytic mechanism. This model may represent a paradigm for other cytosolic bacterial cell wall biosynthetic enzymes working at the interface with the plasma membrane. Our current knowledge of the molecular mechanisms of substrate/membrane recognition by PimA and PimB′ in turn places us in an unprecedented position to identify inhibitors of these enzymes and to develop new drugs with bactericidal mechanisms different from those of presently available agents. Yet considerable challenges remain to be overcome to fully understand the biosynthetic machinery of PIMs, their translocation to the cell surface, their roles in the physiology of mycobacteria, and their contribution to host-pathogen interactions. Among the biochemistry challenges are (i) the identification of the third and fourth α-1,6-ManTs of the pathway (PimC and PimD), that of the α-1,2-ManT catalyzing the formation of PIM6 from PIM5, and that of the acyltransferase responsible for the acylation of position 3 of myo-inositol; (ii) the elucidation of the transport machinery responsible for the translocation of PIM intermediates and lipid-linked sugars across the inner membrane and for the transport of the presumably fully assembled higher and lower forms of PIMs to the cell surface; (iii) the elucidation of the crystal structure of PIM biosynthetic enzymes in complex with PI or PIMs; and (iv) the discovery of potent inhibitors of the PIM pathway that would not only provide bases for the rational design of novel drugs targeting M. tuberculosis but also be useful to probe the physiological functions of PIM, LM, and LAM during in vitro growth and in the course of host infection.

Supplementary Material

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants R01 AI064798 and R37 AI018357 from NIAID. This work was also supported by IKERBASQUE, the Basque Foundation for Science, the Fundacion Biofisica Bizkaia, European Commission Contract LSHP-CT-2005-018923 (New Medicines for Tuberculosis), and the Infectious Disease SuperCluster (Colorado State University). This minireview will be reprinted in the 2010 Minireview Compendium, which will be available in January, 2011.

This work is dedicated to Professor Clinton E. Ballou, honoring the precise and definitive research on the structures of the phosphatidylinositol mannosides conducted by him and his colleagues during the 1960s.

N. Barilone, G. Stadthagen, and M. Jackson, unpublished data.

- PI

- phosphatidyl-myo-inositol

- PIM1

- PI monomannoside

- PIM2

- PI dimannoside

- PIM3

- PI trimannoside

- PIM4

- PI tetramannoside

- PIM5

- PI pentamannoside

- PIM6

- PI hexamannoside

- LM

- lipomannan

- LAM

- lipoarabinomannan

- BCG

- bacillus Calmette-Guérin

- α-ManT

- α-mannosyltransferase

- GT

- glycosyltransferase.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anderson R. J. (1930) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 52, 1607–1608 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ballou C. E., Vilkas E., Lederer E. (1963) J. Biol. Chem. 238, 69–76 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee Y. C., Ballou C. E. (1964) J. Biol. Chem. 239, 1316–1327 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brennan P. J. (1988) in Microbial Lipids (Ratledge C., Wilkinson S. G. eds) pp. 203–298, Academic Press Ltd., London [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ortalo-Magné A., Lemassu A., Lanéelle M. A., Bardou F., Silve G., Gounon P., Marchal G., Daffé M. (1996) J. Bacteriol. 178, 456–461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pitarque S., Larrouy-Maumus G., Payré B., Jackson M., Puzo G., Nigou J. (2008) Tuberculosis 88, 560–565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berg S., Kaur D., Jackson M., Brennan P. J. (2007) Glycobiology 17, 35–56R Review [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kaur D., Guerin M. E., Skovierová H., Brennan P. J., Jackson M. (2009) Adv. Appl. Microbiol. 69, 23–78 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gilleron M., Jackson M., Nigou J., Puzo G. (2008) in The Mycobacterial Cell Envelope (Daffé M., Reyrat J. M. eds) pp. 75–105, American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gilleron M., Quesniaux V. F., Puzo G. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 29880–29889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anderson R. J., Renfrew A. G. (1930) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 52, 1252–1254 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Anderson R. J., Roberts G. (1930) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 52, 5023–5029 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anderson R. J. (1939) Prog. Chem. Org. Nat. Prod. 3, 145–202 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee Y. C., Ballou C. E. (1965) Biochemistry 4, 1395–1404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hill D. L., Ballou C. E. (1966) J. Biol. Chem. 241, 895–902 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chatterjee D., Hunter S. W., McNeil M., Brennan P. J. (1992) J. Biol. Chem. 267, 6228–6233 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gilleron M., Ronet C., Mempel M., Monsarrat B., Gachelin G., Puzo G. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 34896–34904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brennan P., Ballou C. E. (1967) J. Biol. Chem. 242, 3046–3056 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hunter S. W., Brennan P. J. (1990) J. Biol. Chem. 265, 9272–9279 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khoo K. H., Dell A., Morris H. R., Brennan P. J., Chatterjee D. (1995) Glycobiology 5, 117–127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nigou J., Gilleron M., Cahuzac B., Bounéry J. D., Herold M., Thurnher M., Puzo G. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272, 23094–23103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Korduláková J., Gilleron M., Mikusova K., Puzo G., Brennan P. J., Gicquel B., Jackson M. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 31335–31344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guerin M. E., Kaur D., Somashekar B. S., Gibbs S., Gest P., Chatterjee D., Brennan P. J., Jackson M. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 25687–25696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lea-Smith D. J., Martin K. L., Pyke J. S., Tull D., McConville M. J., Coppel R. L., Crellin P. K. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 6773–6782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Korduláková J., Gilleron M., Puzo G., Brennan P. J., Gicquel B., Mikusová K., Jackson M. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 36285–36295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guerin M. E., Kordulakova J., Schaeffer F., Svetlikova Z., Buschiazzo A., Giganti D., Gicquel B., Mikusova K., Jackson M., Alzari P. M. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 20705–20714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lairson L. L., Henrissat B., Davies G. J., Withers S. G. (2008) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 77, 521–555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guerin M. E., Schaeffer F., Chaffotte A., Gest P., Giganti D., Korduláková J., van der Woerd M., Jackson M., Alzari P. M. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 21613–21625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen L., Men H., Ha S., Ye X. Y., Brunner L., Hu Y., Walker S. (2002) Biochemistry 41, 6824–6833 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Varki A., Cummings R., Esko J., Freeze H., Stanley P., Bertozzi C. R., Hart G., Etzler M. E. (2009) Essentials of Glycobiology, 2nd Ed., Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY: [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Morita Y. S., Sena C. B., Waller R. F., Kurokawa K., Sernee M. F., Nakatani F., Haites R. E., Billman-Jacobe H., McConville M. J., Maeda Y., Kinoshita T. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 25143–25155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lind J., Rämö T., Klement M. L., Bárány-Wallje E., Epand R. M., Epand R. F., Mäler L., Wieslander A. (2007) Biochemistry 46, 5664–5677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang X., Weldeghiorghis T., Zhang G., Imperiali B., Prestegard J. H. (2008) Structure 16, 965–975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Seelig J. (2004) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1666, 40–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wieprecht T., Apostolov O., Beyermann M., Seelig J. (2000) Biochemistry 39, 191–201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kremer L., Gurcha S. S., Bifani P., Hitchen P. G., Baulard A., Morris H. R., Dell A., Brennan P. J., Besra G. S. (2002) Biochem. J. 363, 437–447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Patterson J. H., Waller R. F., Jeevarajah D., Billman-Jacobe H., McConville M. J. (2003) Biochem. J. 372, 77–86 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Morita Y. S., Patterson J. H., Billman-Jacobe H., McConville M. J. (2004) Biochem. J. 378, 589–597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kovacevic S., Anderson D., Morita Y. S., Patterson J., Haites R., McMillan B. N., Coppel R., McConville M. J., Billman-Jacobe H. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 9011–9017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Crellin P. K., Kovacevic S., Martin K. L., Brammananth R., Morita Y. S., Billman-Jacobe H., McConville M. J., Coppel R. L. (2008) J. Bacteriol. 190, 3690–3699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Marland Z., Beddoe T., Zaker-Tabrizi L., Lucet I. S., Brammananth R., Whisstock J. C., Wilce M. C., Coppel R. L., Crellin P. K., Rossjohn J. (2006) J. Mol. Biol. 359, 983–997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tam R., Saier M. H., Jr. (1993) Microbiol. Rev. 57, 320–346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Morita Y. S., Velasquez R., Taig E., Waller R. F., Patterson J. H., Tull D., Williams S. J., Billman-Jacobe H., McConville M. J. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 21645–21652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Besra G. S., Morehouse C. B., Rittner C. M., Waechter C. J., Brennan P. J. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272, 18460–18466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Raetz C. R., Whitfield C. (2002) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 71, 635–700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ruiz N. (2008) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 15553–15557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bos M. P., Robert V., Tommassen J. (2007) Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 61, 191–214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Goren M. B. (1984) in The Mycobacteria: A Sourcebook (Kubica G. P., Wayne L. G. eds) Vol. 1, pp. 379–415, Marcel Dekker, Inc., New York [Google Scholar]

- 49.Parish T., Liu J., Nikaido H., Stoker N. G. (1997) J. Bacteriol. 179, 7827–7833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dhariwal K. R., Chander A., Venkitasubramanian T. A. (1977) Can. J. Microbiol. 23, 7–19 [Google Scholar]

- 51.Taneja R., Malik U., Khuller G. K. (1979) J. Gen. Microbiol. 113, 413–416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Penumarti N., Khuller G. K. (1983) Experientia 39, 882–884 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Haites R. E., Morita Y. S., McConville M. J., Billman-Jacobe H. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 10981–10987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Driessen N. N., Ummels R., Maaskant J. J., Gurcha S. S., Besra G. S., Ainge G. D., Larsen D. S., Painter G. F., Vandenbroucke-Grauls C. M., Geurtsen J., Appelmelk B. J. (2009) Infect. Immun. 77, 4538–4547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Briken V., Porcelli S. A., Besra G. S., Kremer L. (2004) Mol. Microbiol. 53, 391–403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fenton M. J., Riley L. W., Schlesinger L. S.2005. in Tuberculosis and the Tubercle Bacillus (Cole S. T., Davis Eisenach K., McMurray D. N., Jacobs W. R., Jr., eds.) pp. 405–426, American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C [Google Scholar]

- 57.Torrelles J. B., Schlesinger L. S. (2010) Tuberculosis 90, 84–93 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Torrelles J. B., Azad A. K., Schlesinger L. S. (2006) J. Immunol. 177, 1805–1816 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.