Abstract

The Group VIA phospholipase A2 (iPLA2β) hydrolyzes glycerophospholipids at the sn-2-position to yield a free fatty acid and a 2-lysophospholipid, and iPLA2β has been reported to participate in apoptosis, phospholipid remodeling, insulin secretion, transcriptional regulation, and other processes. Induction of endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress in β-cells and vascular myocytes with SERCA inhibitors activates iPLA2β, resulting in hydrolysis of arachidonic acid from membrane phospholipids, by a mechanism that is not well understood. Regulatory proteins interact with iPLA2β, including the Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase IIβ, and we have characterized the iPLA2β interactome further using affinity capture and LC/electrospray ionization/MS/MS. An iPLA2β-FLAG fusion protein was expressed in an INS-1 insulinoma cell line and then adsorbed to an anti-FLAG matrix after cell lysis. iPLA2β and any associated proteins were then displaced with FLAG peptide and analyzed by SDS-PAGE. Gel sections were digested with trypsin, and the resultant peptide mixtures were analyzed by LC/MS/MS with database searching. This identified 37 proteins that associate with iPLA2β, and nearly half of them reside in ER or mitochondria. They include the ER chaperone calnexin, whose association with iPLA2β increases upon induction of ER stress. Phosphorylation of iPLA2β at Tyr616 also occurs upon induction of ER stress, and the phosphoprotein associates with calnexin. The activity of iPLA2β in vitro increases upon co-incubation with calnexin, and overexpression of calnexin in INS-1 cells results in augmentation of ER stress-induced, iPLA2β-catalyzed hydrolysis of arachidonic acid from membrane phospholipids, reflecting the functional significance of the interaction. Similar results were obtained with mouse pancreatic islets.

Keywords: Calcium Calmodulin-dependent Protein Kinase (CaMK), ER Stress, Mass Spectrometry (MS), Phospholipase A, Protein-Protein Interactions, Calnexin

Introduction

Phospholipases A2 (PLA2)2 comprise a diverse group of enzymes that catalyze hydrolysis of the sn-2 fatty acid substituent from glycerophospholipid substrates to yield a free fatty acid and a 2-lysophospholipid. The Group VIA PLA2 (iPLA2β) has a molecular mass of 84–88 kDa and does not require Ca2+ for catalytic activity (1–3). Various splice variants of iPLA2β are expressed at high levels in testis (3), brain (4), pancreatic islet β-cells (5), vascular myocytes (6), and a variety of other cells and tissues. It has been reported that iPLA2β participates in physiological processes that include phospholipid remodeling (7, 8), signaling in secretion (9, 10), apoptosis (11, 12), vasomotor regulation (6, 13, 14), transcriptional regulation (15–17), and eicosanoid generation (18, 19), among others.

The amino acid sequence of iPLA2β contains an ankyrin repeat domain with eight strings of a repetitive motif of about 33 amino acid residues (1–3, 20). Ankyrin repeats link integral membrane proteins to the cytoskeleton and mediate protein-protein interactions in signaling in other proteins (21). Ankyrin binds to inositol trisphosphate receptors (22) and associates with skeletal muscle postsynaptic membranes and sarcoplasmic reticulum (23). This raises the possibility that interactions with other proteins could regulate iPLA2β activation and/or subcellular distribution, and iPLA2β association with Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase IIβ (CaMK2) has been demonstrated to affect the activity of both enzymes (24).

To determine whether other proteins also interact with iPLA2β and to explore their role(s) in its regulation, we have expressed an iPLA2β-FLAG fusion protein in rat INS-1 insulinoma cells and used affinity capture, trypsinolysis, and LC/MS/MS with database searching to identify any associated proteins. A total of 37 such proteins were identified, which included several associated with mitochondria or endoplasmic reticulum (ER). Among them is the ER chaperone calnexin, and its association with iPLA2β increases upon induction of ER stress.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cell Culture

INS-1 (rat insulinoma cell line) cells were cultured as described (25, 26) in RPMI 1640 medium containing 11 mm glucose, 10% fetal calf serum, 10 mm Hepes buffer, 2 mm glutamine, 1 mm sodium pyruvate, 50 mm β-mercaptoethanol, 100 units/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin. Cells of the 293TN producer line (SBI, Mountain View, CA) were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (4.5 mg/ml glucose) containing 10% fetal bovine serum, l-Gln (4 mm), 100 units/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin.

Preparation of Recombinant Lentivirus Containing cDNA Encoding Rat Pancreatic Islet iPLA2β or Mouse Calnexin

A lentiviral system (LV500A-1, SBI) was used to stably transfect INS-1 cells with FLAG-tagged iPLA2β (C-terminal tag) and His-tagged calnexin (C-terminal tag) cDNA in order to achieve overexpression of these fusion proteins. Primers used to subclone FLAG-iPLA2β included the 5′ primer (5′-GAT-CGA-ATT-CGC-CAC-CAT-GCA-GTT-CTT-TGG-ACG-CC-3′) and the 3′ primer (5′-AGC-TGC-GGC-CGC-TCA-GAT-TAC-AAG-GAT-GAC-GAC-GAT-AAG-GGG-AGA-TAG-CAG-CAG-CT-3′). Primers used to subclone His-tagged-calnexin included the 5′ primer (5′-GAT-CGA-ATT-CGC-CAC-C-ATG-GAA-GGG-AAG-TGG-TTA-CTG-T-3′) and the 3′ primer (5′-AGC-TGC-GGC-CGC-TCA-CTT-ATC-GTC-GTC-ATC-CTT-GTA-ATC-CTC-TCT-TCG-TGG-CTT-TCT-3′). The constructs containing C-terminal FLAG-iPLA2β or C-terminal His-calnexin cDNA were transfected into Lenti-XTM 293T cells with packaging plasmids according to the manufacturer's instructions (SBI). Infectious virus particles released into the culture medium were collected and used to infect INS-1 cells.

Infection of INS-1 Cells with Recombinant Retrovirus and Selection of Stably Transfected Cells That Overexpress FLAG-iPLA2β or His-Calnexin

INS-1 cells were plated on 100-mm Petri dishes at a density of 3–5 × 105 cells/plate 12–18 h before infection. Freshly collected, lentivirus-containing medium was passed through a 0.45-μm filter and added to INS-1 cell monolayers. Polybrene (final concentration 4 μg/ml) was added to the culture medium, and the medium was replaced after 24 h of incubation. To select stably transfected cells that expressed high levels of iPLA2β fusion protein, lentivirus-infected cells were cultured with G418 (0.4 mg/ml) for 1–2 weeks. After G418-resistant colonies were identified and isolated, they were cultured continuously in INS-1 medium that contained G418 (40 μg/ml).

Affinity Purification and Mass Spectrometric Analysis of Proteins Associated with FLAG-iPLA2β

Stably transfected INS-1 cells that overexpress FLAG-iPLA2β (overexpressing (OE) cells) and INS-1 cells transfected with vector only (VO) cells were cultured in INS-1 medium until they were about 80% confluent. Two T flasks (225 cm2) of OE or VO cells were used in subsequent experiments. Cells were lysed in buffer (4 ml, 2% CHAPS in TBS) that contained protease and phosphatase inhibitors (Sigma) with vortex mixing (30 min on ice), and cell debris was sedimented by centrifugation (4 °C, 15,000 × g, 10 min). Protein concentrations in the supernatants were measured with Coomassie Brilliant Blue reagent according to the manufacturer's instructions (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL). A suspension (1 ml) of FLAG affinity beads was regenerated with 0.1 m glycine-HCl (pH 3.5) and washed with TBS buffer according to the manufacturer's instructions (Sigma). Equal aliquots (0.5 ml) of bead suspensions were placed in each of two columns (15 ml), and lysates (3.4 mg of protein) from OE or VO cells were loaded onto separate columns, which were then capped at both ends and rotated (4 °C, 6 h). The columns were then washed with TBS (10–20 volumes, twice), after which adsorbed proteins were displaced with 0.1 m glycine-HCl (pH 3.5). The eluates were mixed with 5× SDS-PAGE loading buffer and boiled (5 min). Samples were then analyzed by SDS-PAGE (10 × 15 cm gel), and proteins were visualized with SYPRO Ruby (Bio-Rad) stain. Gel lanes were cut into 10 sections, and in-gel trypsin digestion was performed before analysis by LC/MS/MS.

Mass spectrometric analyses were performed on a Thermo LTQ-FT (Thermo Fisher, San Jose, CA) instrument. Samples were loaded with an Eksigent autosampler onto a 15-cm Magic C18 column (5-μm particles, 300-Å pores, Michrom Bioresources, Auburn, CA) packed into a PicoFrit tip (New Objective, Woburn, MA), and analyzed on a nano-LC-1D HPLC. Analytical gradients were from 0 to 50% organic phase (98% acetonitrile, 0.1% formic acid in water, Sigma-Aldrich) over 60 min. Aqueous phase composition was 2% acetonitrile, 0.1% formic acid in water (Sigma-Aldrich). Eluant was routed into a PV-550 nanospray ion source (New Objective, Woburn, MA). Chromatographic peaks were typically about 15 s wide (FWHM). The LTQ-FT was operated in a data-dependent mode with preview scanning over the range m/z 400–2000. MS2 scans were performed in the LTQ. The FTMS AGC target was set to 1E06, and the MS2 AGC target was 2E04 with maximum injection times of 1000 and 500 ms, respectively. The first scan was a full Fourier transform mass spectrum (RP = 100,000 and m/z 421) and could trigger up to nine MS2 scans using parent ions selected from the MS1 scan. Dynamic exclusion was enabled for 30 s with a repeat count of three and expiration after 40 s. For tandem MS, the LTQ isolation width was 1.8 Da, the normalized collision energy was 35%, and the activation time was 30 ms. Raw data were submitted through the Mascot daemon client program to Mascot Server 2.0 and searched against the NCBInr database.

Affinity Purification for Western Blotting Analyses

Stably transfected INS-1 cells overexpressing FLAG-iPLA2β or His-calnexin or INS-1 cells transfected with VO were cultured in INS-1 medium until 80% confluent. Cells were lysed in buffer (4 ml, TBS with 2% CHAPS) that contained protease and phosphatase inhibitors (Sigma), and cell debris was sedimented by centrifugation, as described above. Protein concentrations in supernatants were measured with Coomassie Brilliant Blue reagent. To prepare suspensions of FLAG affinity beads (40 μl) for capture of FLAG-iPLA2β or of cobalt beads for capture of His-calnexin, the beads were washed twice with TBS buffer (0.5 ml, ice-cold) and then resuspended (TBS, 110 μl, ice-cold). Aliquots of INS-1 FLAG-iPLA2β OE cell lysates adjusted to contain equal amounts of protein were placed in each of two centrifuge tubes (2 ml), and anti-FLAG-bead suspension (5 μl) was added to each of the tubes, which were then rotated (4 °C, 2–4 h). The beads were then washed extensively with ice-cold TBS, and iPLA2β and any associated proteins were subsequently displaced from the beads by incubating with FLAG peptide (200 μl, 500 ng/μl) in TBS (30 min, on ice, with shaking). The INS-1 His-calnexin OE cell lysates were processed similarly, except that cobalt affinity beads were used; the lysate was diluted 5-fold to reduce the CHAPS concentration; 15-ml rather than 2-ml centrifuge tubes were used; and cobalt affinity beads were boiled in 2× SDS-PAGE loading buffer (100 μl). Samples were then analyzed by 10% SDS-PAGE, and separated proteins were transferred onto PVDF membranes (Bio-Rad) that were then probed with antibodies.

Protein Glycosylation Detection

FLAG-tagged iPLA2β was purified with FLAG affinity resin (Sigma) and analyzed by 10% SDS-PAGE, and the glycosylation state of iPLA2β was examined with a glycoprotein detection kit (P0300, Sigma) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Protein Dephosphorylation with λ-Protein Phosphatase or Protein Phosphatase-1

INS-1 cells that overexpressed His-calnexin were treated with thapsigargin (16 h). Cells were then lysed, and His-calnexin was captured on a cobalt affinity column and eluted along with any associated proteins. The eluant was incubated either with λ-protein phosphatase (NEB 0753S) or with Protein Phosphatase 1 (NEB 0754S) (New England Biolabs) according to the manufacturer's protocols.

Phosphopeptide Isolation with Immobilized Metal Affinity Columns

Phosphopeptide enrichment was achieved by capture on TiO2 microtip columns by methods described previously (27). Briefly, TiO2 beads (1–2 mg) were loaded into a 10-μl barrier tip, and the protein digest was applied to the resultant TiO2 tip column by attaching the column to the female luer extension on a vacuum manifold. Columns were then washed (50 μl, 70% acetonitrile and 2% formic acid in water, twice), and captured phosphopeptides were eluted with 2% ammonium hydroxide (30 μl). After pH adjustment with formic acid (0.5 μl), phosphopeptides in the eluant (10 μl) were analyzed by LC/MS/MS (Eksigent 2D Plus LC (Dublin, CA) and ThermoElectron LTQ MS (Waltham, MA)), and potential phosphopeptides were identified by Mascot database searching.

Phospholipase A2 Enzymatic Activity

Ca2+-independent PLA2 enzymatic activity was assayed (30 μg of protein) in the absence and presence of ATP (10 mm) or BEL (10 μm) by ethanolic injection (5 μl) of the substrate 1-palmitoyl-2-[14C]linoleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (5 μm) in assay buffer (40 mm Tris, pH 7.5, 5 mm EGTA) by monitoring release of [14C]linoleate, as described previously (28).

Isolation of Pancreatic Islets from Mice

As described previously (30), islets were isolated from pancreata of WT C57BL/6J and RIP-iPLA2β-transgenic mice by collagenase digestion after mincing, followed by Ficoll step density gradient separation and manual selection under stereomicroscopic visualization to exclude contaminating tissues. Mouse islets were counted and used for [3H]arachidonic acid incorporation and release and for co-immunoprecipitation experiments.

Incorporation into and Release of [3H]Arachidonic Acid from INS-1 Cells and Isolated Islets

These experiments were performed essentially as described elsewhere (29) with modifications. INS-1 cells were prelabeled by incubation (5 × 105 cells/well, 20 h, 37 °C) with [3H]arachidonic acid (final concentration 0.5 μCi/ml, 5 nm). To remove unincorporated radiolabel, the cells were incubated (1 h) in serum-free medium and then washed three times with glucose-free RPMI 1640 medium. [3H]Arachidonate incorporation into phospholipid extracts was then determined by TLC and liquid scintillation spectrometry (25). Labeled cells were incubated in RPMI 1640 medium (0.5% BSA, 37 °C, 20 min) containing various additives (e.g. 10 μm BEL or DMSO vehicle). After removing that medium, cells were placed in RPMI 1640 medium with 0.5% BSA that contained various additives (e.g. 1 μm thapsigargin or vehicle) and incubated for various intervals at 37 °C. At the end of the incubation interval, cells were collected by centrifugation (500 × g, 5 min), and the 3H content of the supernatant was measured by liquid scintillation spectrometry, as described elsewhere (28). The amounts of released 3H were expressed as a percentage of incorporated 3H and normalized to the value of the appropriate control condition.

Similar experiments were performed with islets (∼1,200) isolated from 12 WT C57BL/6J mice that were incubated (12 h, 37 °C) in CMRL complete medium and then placed in fresh medium containing [3H]arachidonic acid (1 μCi) and incubated (20 h, 37 °C). The islets were washed three times with CMRL medium with 0.5% BSA to remove unincorporated radiolabel and divided into 12 aliquots, each of which was placed in a round bottom cryogenic vial (2-ml capacity) containing CMRL medium with 0.5% BSA (200 μl). Either BEL (final concentration 10 μm) or ethanol vehicle alone was then added, and incubation was continued (15 min, 37 °C). The medium was then removed, and the islets were washed three times with CMRL medium containing 0.5% BSA (200 μl). The islets were then placed in experimental medium (200 μl) containing either A23187 (10 μm) plus EGTA (0.5 mm) or DMSO vehicle alone and incubated (30 min, 37 °C). The medium was then removed, and its 3H content was determined by liquid scintillation spectrometry. Islet pellets were lysed in buffer (200 μl, 50 mm Tris-HCl with 1% Triton X-100), and the 3H content of an extract was determined.

Immunoprecipitation Experiments with Isolated Islets

Isolated islets were lysed in immunoprecipitation buffer (1 ml, 150 mm NaCl, 50 mm Tris-HCl, 1 mm sodium vanadate, 0.5 mm sodium fluoride, and inhibitors of proteases and phosphatases) by vortex mixing (on ice, 30 min). Lysates were centrifuged (10,000 × g, 4 °C, 10 min) to remove particulate debris. Supernatants were then precleared with washed protein A-agarose (60 μl) and were then divided into two aliquots. One was incubated (overnight, 4 °C, with agitation) with the immunoprecipitating antibody (1:20–50; 20 μl in 500 μl of lysate). Washed protein A-agarose beads (70–100 μl) were then added to each sample, and the mixture was incubated (4 °C, rotary agitation, 4 h). The agarose beads were collected by centrifugation (microcentrifuge, 14,000 × g, 5 s), and the supernatant was removed. The collected beads were washed three times (ice-cold PBS) and then boiled (95–100 °C, 5 min) to detach any associated proteins, which were then analyzed by SDS-PAGE, transferred to PVDF membranes, and probed with antibodies directed against either iPLA2β or calnexin in Western blotting experiments.

Statistical Methods

Results are presented as mean ± S.E. Data were evaluated by unpaired, two-tailed Student's t test or by analysis of variance with appropriate post hoc tests (29). Significance levels are described in the figure legends.

RESULTS

Identification of iPLA2β-interacting Proteins in Stably Transfected INS-1 Cells That Overexpress FLAG-iPLA2β

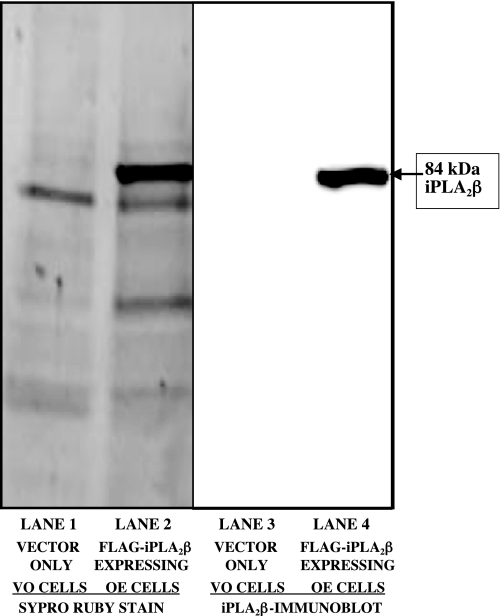

Our approach to examining the iPLA2β interactome involved OE FLAG-iPLA2β in stably transfected INS-1 cells, capturing FLAG-iPLA2β and any associated proteins on FLAG-antibody affinity resin, displacing the adsorbed proteins with FLAG peptide, analyzing the eluates by SDS-PAGE, excising the separated protein bands, performing in-gel tryptic digestion, and then analyzing the digests by LC/MS/MS with database searching. INS-1 cells transfected with VO were used as controls. Fig. 1 illustrates an SDS-PAGE analysis of proteins in the affinity column eluate as visualized by SYPRO Ruby staining (lanes 1 and 2). The major band at 84 kDa in lane 2 (Fig. 1, FLAG-iPLA2β OE) corresponds to iPLA2β itself, as verified by Western blotting with anti-iPLA2β antibody T-14 (Fig. 1, lane 4).

FIGURE 1.

Expression of FLAG-iPLA2β in INS-1 cells, followed by affinity capture, desorption, and SDS-PAGE analysis. INS-1 cells were stably transfected with lentivirus vector only (lanes 1 and 3) or with vector containing cDNA encoding FLAG-iPLA2β (lanes 2 and 4) with the tag at the C terminus as described under “Experimental Procedures.” After incubation, cells were lysed, and the lysates were incubated with FLAG affinity resin and washed. Adsorbed proteins were then eluted and analyzed by 10% SDS-PAGE. Protein bands in lanes 1 and 2 were visualized with SYPRO Ruby stain. Lanes 3 and 4 represent immunoblots probed with antibody directed against iPLA2β.

Data from LC/MS/MS analyses of tryptic digests of proteins recovered from the FLAG-iPLA2β affinity capture experiments were processed by Mascot software and searched against the NCBInr protein sequence database. To select proteins that interact specifically with iPLA2β and to eliminate those that adsorb to the affinity resin in a nonspecific manner, we excluded proteins that were observed in VO cell lysates.

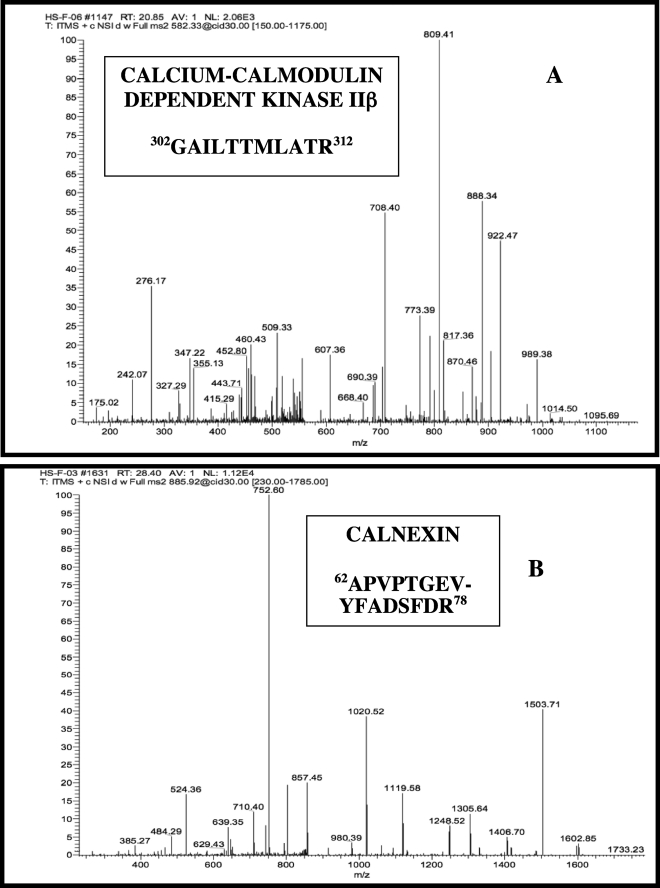

Two of the iPLA2β-interacting proteins identified in this way are CaMK2 and calnexin, and MS/MS scans that reveal the sequence of an observed peptide from each of these proteins are displayed in Fig. 2, A and B, respectively. A total of four CaMK2 tryptic peptides were observed, including 302GAILTTMLATR312 (Fig. 2A), 461FYFENLLAK469, 136DLKPENLLLASK147, and 10FTDEYQLYEDIGK22 (supplemental Table 1). The interaction between iPLA2β and CaMK2 was expected because it has previously been demonstrated by yeast two-hybrid screening and immunoprecipitation experiments by our group (24), although this is the first verification of the interaction by MS analyses. The iPLA2β-CaMK2 complex exhibits increased PLA2 and kinase activities in vitro compared with the individual proteins, and treating INS-1 cells with the adenylyl cyclase activator forskolin increases both the abundance of the immunoprecipitatable complex (24) and insulin secretion, suggesting that the interaction is functionally important in beta cell signal transduction.

FIGURE 2.

Tandem mass spectra of tryptic peptides from calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase IIβ (A) and from calnexin (B) observed in LC/MS/MS analyses of digests of FLAG-iPLA2β and interacting proteins from INS-1 cells. FLAG-iPLA2β and interacting proteins were generated, isolated, digested, and analyzed by LC/MS/MS as in Fig. 1. The tandem spectrum of one of four observed tryptic peptides from the sequence of calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase IIβ is illustrated in A, and the tandem spectrum of one of three observed tryptic peptides from calnexin is illustrated in B.

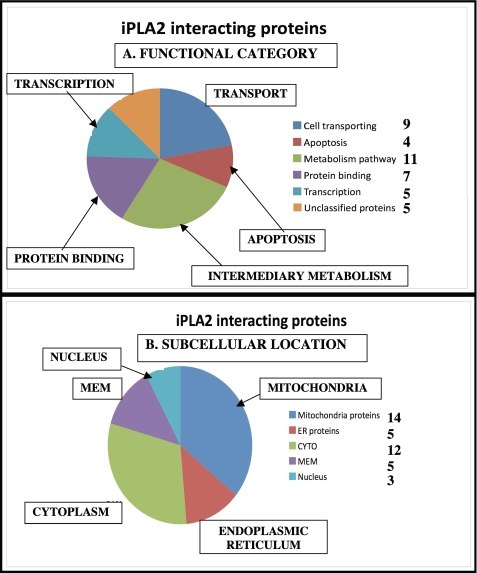

Table 1 displays the complete list of iPLA2β-interacting proteins identified in this manner. Proteins are grouped according to general function, and each is identified by its NCBInr protein database accession number, the corresponding protein description, and the name of the gene that encodes it. The number of distinct tryptic peptides within its sequence that were observed in the LC/MS/MS analyses is also specified. The peptides identified and their sequences are displayed in supplemental Table 1, which also specifies the deviation of observed and theoretical molecular masses of the precursor peptides and the Mascot score for each peptide. Protein species identified by a single peptide are not included. A total of 37 iPLA2β-interacting proteins were identified in this manner (Table 1 and Fig. 3) and include proteins involved in apoptosis (four), transport (eight), intermediary metabolism (eight), protein binding (seven), and transcription or translation (five) (Fig. 3A).

TABLE 1.

Summary of iPLA2β-interacting proteins identified by mass spectrometry in stably transfected INS-1 cells that overexpress FLAG-iPLA2β

Proteins shown were observed in each of three separate experiments.

| Accession number | Description | Gene name | Peptide hits |

|---|---|---|---|

| Proteins involved in cell trafficking | |||

| gi:37590229 | Solute carrier family 25, member 5 | slc25a5 | 6 |

| gi:57303 | Sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase | atp2a2 | 5 |

| gi:358959 | Na/K-ATPase α1 | atp1a1 | 4 |

| gi:13592037 | RAB3B, member RAS oncogene family | rab3b | 4 |

| gi:39645769 | ATP synthase, H+ transporting, mitochondrial F0 complex, subunit b, isoform 1 | atp5f1 | 4 |

| gi:829018 | Cytochrome c oxidase subunit II | coxll | 2 |

| gi:20806141 | Solute carrier family 25 (mitochondrial carrier; phosphate carrier), member 3 | slc25a3 | 4 |

| gi:1580888 | 2-Oxoglutarate carrier protein (Slc25a11) | slc25a11 | 6 |

| Proteins involved in apoptosis | |||

| gi:84370227 | DnaJ (Hsp40) homolog, subfamily A, member 3 isoform 1 | dnaja2 | 3 |

| gi:1050930 | Polyubiquitin | ubc | 2 |

| gi:58865966 | Tumor rejection antigen gp96 | hsp90b1 | 5 |

| gi:71051169 | Stomatin (Epb7.2)-like 2 | stoml2 | 2 |

| Proteins involved in intermediary metabolism | |||

| gi:8392839 | ATP citrate lyase | acly | 4 |

| gi:1709948 | Pyruvate carboxylase, mitochondrial precursor | pc | 2 |

| gi:60688124 | Hadha protein | hadha | 12 |

| gi:206205 | M2 pyruvate kinase | pk | 5 |

| gi:54035427 | Gpd2 protein | gpd2 | 4 |

| gi:1352624 | Pyruvate dehydrogenase E1 component subunit β, mitochondrial precursor | pdhb | 2 |

| gi:51260712 | Isocitrate dehydrogenase 3 (NAD+) beta | idh3b | 2 |

| gi:54035592 | Prohibitin | phb | 10 |

| Proteins involved in protein-protein interactions | |||

| gi:62659750 | PREDICTED: similar to coatomer protein complex subunit α | copa-predicted | 13 |

| gi:62647711 | PREDICTED: similar to CCTη, η subunit of the chaperonin containing TCP-1 | cct7 | 3 |

| gi:38969850 | Chaperonin containing TCP1, subunit 3 (γ) | cct3 | 2 |

| gi:310085 | Calnexin (ER chaperone, calcium binding) | canx | 3 |

| gi:6981450 | ATP-binding cassette, subfamily D (ALD), member 3 | abcd3 | 2 |

| gi:4557469 | Adaptor-related protein complex 2, β1 subunit isoform b (membrane adaptor) | ap2b1 | 3 |

| gi:55622 | α-Internexin | alpha-1.6 | 3 |

| Proteins involved in transcription or translation | |||

| gi:53734533 | B-cell receptor-associated protein 37 | phb2 | 4 |

| gi:6016535 | DNA replication licensing factor MCM6 | mcm6 | 2 |

| gi:8393296 | Eukaryotic translation elongation factor 2 | eef2 | 2 |

| gi:50925575 | Minichromosome maintenance protein 7 | mcm7 | 3 |

| gi:34870013 | PREDICTED: minichromosome maintenance-deficient 4 homolog | mcm4 | 3 |

| Unclassified proteins | |||

| gi:225775 | Calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II | camk2b | 4 |

| gi:34856103 | PREDICTED: similar to Nodal modulator 1 | nomo1 | 4 |

| gi:5811587 | TIP120-family protein TIP120B, short form | tip120b | 2 |

| gi:32451602 | Protein kinase, cAMP dependent, catalytic, beta | prkacb | 2 |

| gi:38014694 | Valosin-containing protein | vcp | 6 |

FIGURE 3.

Summary of iPLA2β-interacting proteins in INS-1 cells that overexpress FLAG-iPLA2β identified by affinity capture, SDS-PAGE, and LC/MS/MS. FLAG-iPLA2β and interacting proteins were generated in INS-1 cells, affinity-captured, and analyzed by SDS-PAGE as in Fig. 1. Gels were sectioned, in situ tryptic digestion was performed, and the digests were analyzed by LC/MS/MS with database searching as described under “Experimental Procedures.” A, functional category; B, subcellular localization. The displayed results represent a summary of three separate experiments.

Mitochondrial and Endoplasmic Reticulum Proteins Interact with iPLA2β

The subcellular localization of the identified iPLA2β-interacting proteins is summarized in Fig. 3B, and nearly half of them reside in mitochondria or the ER, which is consistent with reports that a portion of cellular iPLA2β resides in mitochondria (31) and that ER stress induces subcellular redistribution of iPLA2β and increased mitochondrial association (29, 32). Our studies have identified a total of 11 mitochondrial proteins (Fig. 3B) in the iPLA2β interactome, of which six are membrane proteins and five are matrix proteins. Entry into the mitochondrial matrix would presumably require iPLA2β to traverse mitochondrial membranes, and this process generally requires a signal peptide in N-terminal segments of the protein that can be recognized by specific receptors in the mitochondrial outer membrane (33). We have previously observed that iPLA2β undergoes both N-terminal and C-terminal processing and that its apparent subcellular distribution depends on whether the tag used to localize it is attached to the N or C terminus (12, 34, 35), suggesting that specific proteolytically processed forms of iPLA2β might interact with mitochondria.

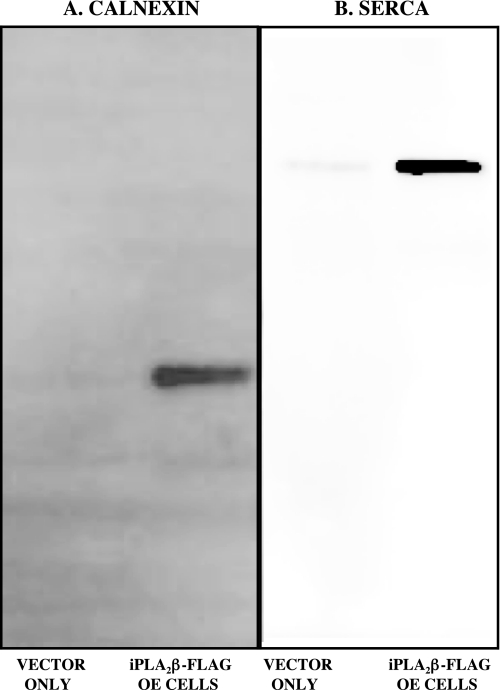

Our studies identify four ER proteins that interact with iPLA2β, including the ER chaperone and Ca2+-binding protein calnexin (Figs. 2B and 4A) and the sarco(endo)plasmic reticulum ATPase (SERCA) (Fig. 4B). The others are tumor rejection antigen gp96 (GRP94) and valosin-containing protein (supplemental Table 1). The interaction of iPLA2β with each protein was also confirmed immunochemically by performing Western blotting experiments with appropriate antibodies on eluates from FLAG affinity columns onto which lysates from FLAG-iPLA2β-overexpressing INS-1 cells had been loaded, as illustrated in Fig. 4 for calnexin (A) and SERCA (B). These proteins were recovered from the FLAG affinity columns only with lysates of FLAG-iPLA2β-overexpressing INS-1 cells and not with those of INS-1 cells transfected with vector only (Fig. 4).

FIGURE 4.

Immunochemical verification of the identities of iPLA2β-interacting proteins identified by LC/MS/MS analyses. FLAG-iPLA2β and interacting proteins were generated in INS-1 cells, affinity-captured, and analyzed by SDS-PAGE as in Fig. 1. Immunoblotting was then performed with antibodies directed against calnexin (A) or SERCA (B) as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Displayed results are representative of three separate experiments.

The Interaction between iPLA2β and Calnexin Is Regulated by Thapsigargin-induced ER Stress

ER stress can induce apoptosis in a wide variety of cells by processes that are incompletely understood (36), and thapsigargin, which inhibits SERCA, is often used to induce apoptosis via ER stress in INS-1 cells and other cells (12). The sensitivity of INS-1 cell lines to thapsigargin-induced apoptosis increases with their iPLA2β expression level, and thapsigargin treatment increases INS-1 cell iPLA2β activity and alters its subcellular distribution (9). This indicates that ER events are communicated to iPLA2β and may participate in its regulation, but the mechanism by which this occurs is not known.

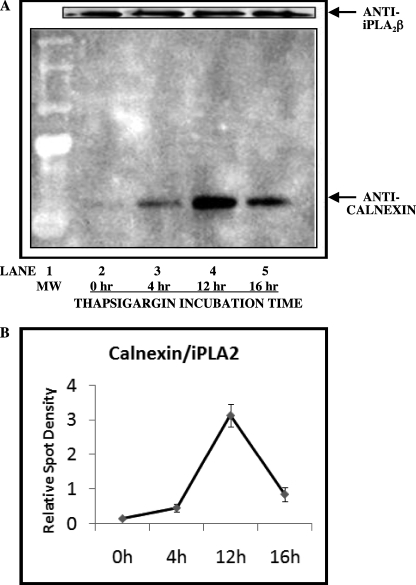

Among the four identified ER proteins that interact with iPLA2β, the association with calnexin increased in a time-dependent manner upon induction of ER stress with thapsigargin, as illustrated in Fig. 5, but the others did not. In these experiments, stably transfected INS cells that overexpress FLAG-iPLA2β were treated with thapsigargin for 0, 4, 12, or 16 h. Lysates from the FLAG-iPLA2β-OE-INS1-cells were then incubated with FLAG affinity resin, and adsorbed proteins were subsequently displaced with FLAG peptide. The eluate was analyzed by SDS-PAGE, and the separated proteins were transferred onto PVDF membranes and probed with anti-calnexin antibody and, after stripping, with anti-iPLA2β antibody.

FIGURE 5.

Induction of ER stress with thapsigargin increases the association of calnexin with iPLA2β in INS-1 cells that overexpress FLAG-iPLA2β. INS-1 cells stably transfected to overexpress FLAG-iPLA2β were incubated for various intervals with 1 μm thapsigargin and then lysed. Lysates were processed as in Fig. 1 to capture FLAG-iPLA2β and associated proteins, which were then analyzed by SDS-PAGE. In A, immunoblotting was then performed with antibodies directed against calnexin, and, after stripping and reprobing, for iPLA2β. B represents a plot of the densitometric ratios for calnexin over iPLA2β as a function of incubation time with thapsigargin. The displayed results are representative of three separate experiments.

Fig. 5 illustrates that the intensity of the calnexin-immunoreactive band that co-purified with iPLA2β increased progressively between 4 and 12 h of thapsigargin treatment relative to the vehicle control. The intensity of the calnexin band declined at 16 h, and this probably reflects loss of cells from apoptosis, which occurs over that time course under these conditions (32). Fig. 5 also illustrates that the intensity of the iPLA2β-immunoreactive band in these experiments remains fairly constant, which indicates that the variable intensity of the calnexin-immunoreactive signal in Fig. 5 reflects changes in the extent of association of calnexin with iPLA2β rather than variable capture of the FLAG-iPLA2β complex.

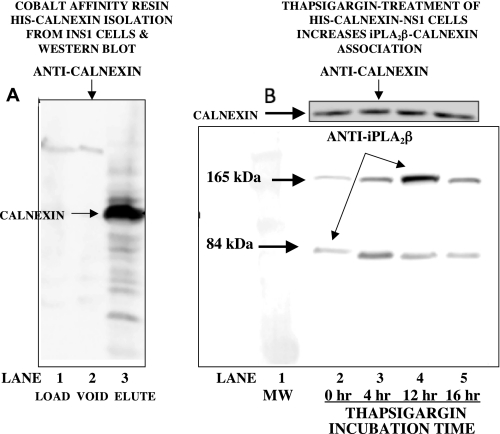

Experiments Involving Expression of His-tagged Calnexin in INS-1 Cells Followed by Affinity Capture with Cobalt Columns and Immunoblotting Corroborate Thapsigargin-induced Association of iPLA2β and Calnexin

To examine further the interaction between calnexin and iPLA2β, INS-1 cells were infected with lentivirus that contained cDNA encoding C-terminally His-tagged calnexin in order to overexpress His-calnexin. Lysates from these cells were then loaded onto cobalt affinity columns to capture His-calnexin and any associated proteins, and the columns were then washed to remove non-adsorbed proteins. Interaction of His-calnexin with cobalt ions in the column resin was disrupted with 200 mm imidazole or by boiling the beads with SDS-PAGE buffer. Aliquots from the load, void, and eluant fractions that contained identical measured amounts of protein were then analyzed by SDS-PAGE, and blots from the gels were probed with anti-calnexin antibody, as illustrated in Fig. 6A.

FIGURE 6.

Induction of ER stress with thapsigargin increases the association of iPLA2β with calnexin in INS-1 cells that overexpress His-calnexin. INS-1 cells were stably transfected to overexpress His-calnexin. In A, cells were lysed and applied to cobalt affinity columns (LOAD, lane 1), which were then washed (VOID, lane 2). His-calnexin and associated proteins were then desorbed (ELUTE, lane 3) and analyzed by SDS-PAGE as in Fig. 1. Immunoblotting was then performed with anti-calnexin antibody. In B, INS-1 cells that overexpressed His-calnexin were incubated for various intervals with thapsigargin, and lysates were then processed as in A. Immunoblots were probed with anti iPLA2β antibody and then stripped and reprobed with anti-calnexin antibody (inset in B). Displayed results are representative of three separate experiments.

Reverse binding experiments were performed by incubating stably transfected INS-1 cells that overexpress His-calnexin with thapsigargin for various intervals. Cell lysates were then incubated with cobalt affinity resin to capture His-calnexin and any associated proteins, and adsorbed proteins were then displaced and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting with antibodies directed against calnexin and iPLA2β. Fig. 6B illustrates that the intensity of the calnexin-immunoreactive band in these experiments is fairly constant, which suggests that there is little variability in the extent of capture of His-calnexin by the cobalt affinity resin from experiment to experiment. Western blots performed with antibody directed against iPLA2β revealed two immunoreactive bands with apparent molecular masses of about 84 kDa and about 165 kDa, respectively, and the intensities of the bands varied with thapsigargin incubation time in a manner similar to calnexin in Fig. 5, which suggests that thapsigargin-induced association of calnexin and iPLA2β might involve a dimer or a post-translationally modified form of iPLA2β that migrates with a higher apparent molecular weight.

The Interaction between iPLA2β and Calnexin Is Not Regulated by Glycosylation

Calnexin is a chaperone molecule, and its best recognized function is to retain unfolded or unassembled N-linked glycoproteins in the endoplasmic reticulum (37). Calnexin binds mainly monoglucosylated carbohydrates on newly synthesized glycoproteins. If the glycoprotein is not properly folded, the sequential actions of glucosidases I and II trim two glucose residues from the misfolded glycoprotein to form monoglucosylated oligosaccharides that bind calnexin and result in ER retention of the misfolded protein (37). To determine whether this lectin-binding mechanism is involved in the association of iPLA2β with calnexin, the extent of iPLA2β glycosylation was assessed by glycosylation-specific fluorescence staining. These experiments indicated that there is little glycosylation of iPLA2β under control conditions and that no significant change in that property occurs upon thapsigargin treatment (not shown).

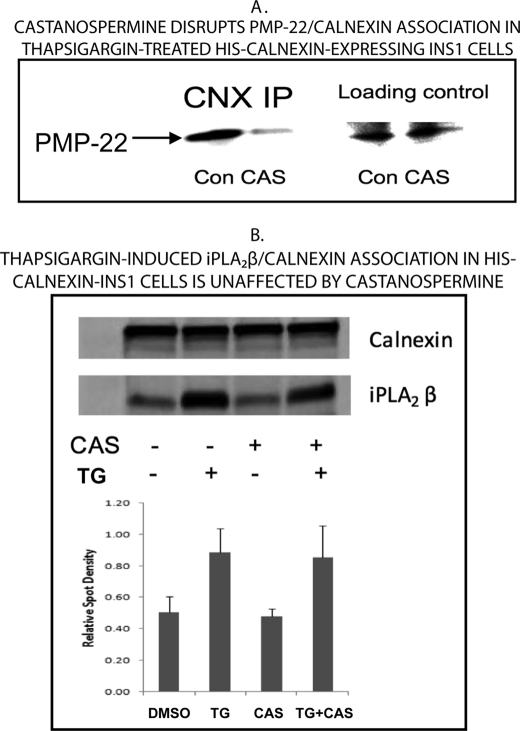

Additional evaluation of a possible lectin-binding mechanism for the association of iPLA2β with calnexin was performed with the glucosidase inhibitor castanospermine, which blocks the actions of glucosidases I and II and prevents the generation of the lectin binding site recognized by calnexin. This effect of castanospermine is illustrated in Fig. 7A. The protein PMP-22 (peripheral myelin protein-22) is known to associate with calnexin by the classical lectin-binding mechanism (38), and immunoreactive PMP-22 is readily demonstrable by Western blotting of the eluates of cobalt affinity columns to which lysates of INS-1 cells that overexpress His-calnexin had been applied (Fig. 7A, lane 1). The magnitude of the immunoreactive PMP-22 signal was greatly reduced when the cells were incubated with castanospermine (Fig. 7A, lane 2) because of the effect of the compound to prevent generation of the lectin-binding motif recognized by calnexin. In contrast, the thapsigargin-induced association of calnexin and iPLA2β was unaffected by castanospermine (Fig. 7B), suggesting that this interaction does not involve a classical lectin-binding mechanism.

FIGURE 7.

The glucosidase inhibitor castanospermine disrupts association of calnexin with PMP-22 but not with iPLA2β in thapsigargin-treated INS-1 cells that express His-calnexin. INS-1 cells were stably transfected to overexpress His-calnexin. In A, cells were incubated with vehicle (DMSO; Con) or with castanospermine (1 mm; CAS) and then incubated with thapsigargin and processed as in Fig. 6. Immunoblots from SDS-PAGE analyses were probed with antibody directed against PMP-22. The two leftmost lanes reflect Western blots of SDS-PAGE analyses of the immunoprecipitate obtained with the anti-calnexin antibody (CNX IP). The two rightmost lanes are loading controls on which no immunoprecipitation was performed before SDS-PAGE and Western blotting with the antibody against PMP-22. In B, experiments were performed in a similar manner, except that immunoblots were probed with antibody directed against iPLA2β and then stripped and reprobed with antibody directed against calnexin. Densitometric ratios of signals contained with the two antibodies were computed and plotted in the histogram in the lower portion of B. Displayed results are representative of three separate experiments. TG, thapsigargin.

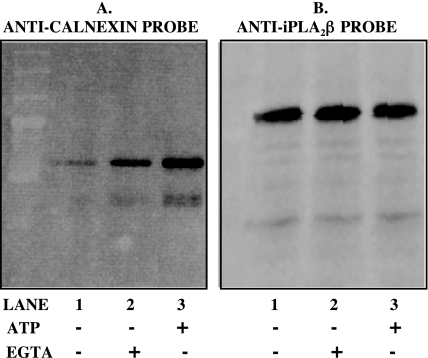

Ca2+ Depletion and ATP Enhance the Association of iPLA2β and Calnexin

ATP and Ca2+ are cofactors involved in binding of protein oligosaccharide moieties to calnexin (39). Both ATP and Ca2+ induce conformational changes in the ER luminal domain of calnexin and enhance its binding of oligosaccharide substrates (39). In contrast, Ca2+ tends to disrupt calnexin binding to proteins via polypeptide sequence motifs, although ATP does promote such binding by affecting calnexin conformation (40). Fig. 8 illustrates that the association of calnexin and iPLA2β is affected by the concentrations of Ca2+ and ATP in the buffer in which thapsigargin-treated INS-1 cells that express FLAG-iPLA2β are lysed before affinity capture.

FIGURE 8.

Influence of ATP and chelation of Ca2+ with EGTA on association of calnexin and iPLA2β. INS-1 cells stably transfected to overexpress FLAG-iPLA2β were incubated for various intervals with 1 μm thapsigargin and then lysed as in Fig. 5, and lysates were then incubated with no additions (lanes 1 in A and B), with 5 mm EGTA (lanes 2 in A and B), or with 1 mm ATP (lanes 3 in A and B). The lysates were then processed as in Fig. 5 to capture FLAG-iPLA2β and associated proteins, which were then analyzed by SDS-PAGE. Immunoblotting was then performed with antibodies directed against calnexin (A), and blots were then stripped and reprobed with antibodies directed against iPLA2β (B). Displayed results are representative of three separate experiments.

As reflected by the magnitude of the immunoreactive calnexin signal upon Western blotting of eluates from FLAG affinity columns, adding 3 mm EDTA to the lysis buffer to chelate free Ca2+ increases the association of calnexin and iPLA2β (Fig. 8A, lanes 1 and 2), as does adding 1 mm ATP without EGTA (Fig. 9A, lane 3). The magnitude of the iPLA2β-immunoreactive signal was relatively constant under these conditions (Fig. 8B), suggesting that calnexin signal intensity is governed by the degree of calnexin-iPLA2β association in these experiments rather than by variations in the amount of iPLA2β captured by the affinity column. The findings in Figs. 7 and 8 thus suggest that calnexin does not interact with iPLA2β via oligosaccharide binding but may do so via a polypeptide domain, as do some other proteins (41).

FIGURE 9.

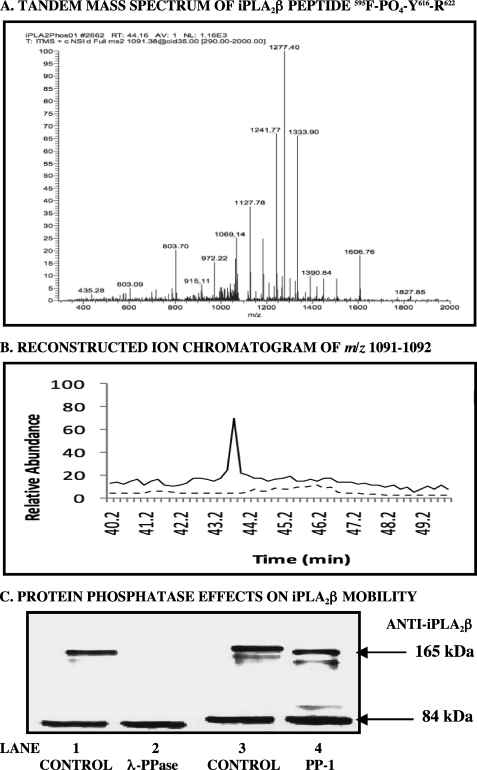

Identification of a phosphotyrosine residue in iPLA2β after thapsigargin treatment of His-calnexin-INS1 cells. INS-1 cells were stably transfected to overexpress His-calnexin and incubated with thapsigargin or vehicle as in Fig. 6. The cells were then lysed, and the lysates were passed over cobalt affinity columns to capture and then elute His-calnexin and associated proteins, including iPLA2β. Eluates were processed by SDS-PAGE and tryptic digestion, and digests were analyzed by LC/MS/MS, as in Fig. 3. A, tandem spectrum of a tryptic peptide (595FLDGGLLANNPTLDAMTEIHEYNQDMIR62) from the iPLA2β sequence in which Tyr616 is phosphorylated that was obtained from materials in a thapsigargin-treated cell lysate. B, reconstructed ion chromatogram for the [M + 3H]3+ ion (m/z 1091–1092) of that peptide from LC/MS analyses of tryptic digests. Solid line, thapsigargin-treated cells; dashed line, vehicle-treated cells. C, immunoblots from SDS-PAGE analyses of cobalt column eluates obtained from thapsigargin-treated cells. The eluates in lanes 1 and 3 (CONTROL) were not treated with phosphatase. The eluates in lanes 2 and 4 were treated with λ-protein phosphatase (λ-PPase) and protein phosphatase-1 (PP-1), respectively, before SDS-PAGE analyses. The blots were probed with antibody directed against iPLA2β. Displayed results are representative of three separate experiments.

Phosphorylation of an iPLA2β Tyrosine Residue

Phosphorylation is a post-translational modification that can cause a PLA2 enzyme to migrate with a higher than expected molecular mass on SDS-PAGE (42, 43). This suggests the possibility that the high molecular weight iPLA2β-immunoreactive band in Fig. 6B could represent a phosphorylated isoform. To examine this possibility, His-calnexin and associated proteins in eluates from cobalt affinity columns to which His-calnexin-expressing INS-1 cell lysates had been applied were digested with trypsin, and the digests were loaded onto TiO2 tip columns to capture phosphopeptides. Eluates from these columns were then analyzed by LC/MS/MS, and acquired spectra were submitted to a Mascot server (Matrix Science Inc., Boston, MA) to identify potential phosphorylated peptides via database searching.

Fig. 9A is the tandem spectrum of the iPLA2β tryptic peptide 595FLDGGLLANNPTLDAMTEIHEY(PO4)NQDMIR622 from a thapsigargin-treated His-calnexin-expressing INS-1 cell lysate subjected to collision-induced dissociation on an LTQ mass spectrometer. The spectrum indicates that Tyr616 within this peptide is phosphorylated, and this phosphopeptide was not observed in eluates from vehicle-treated cells, as illustrated in Fig. 9B, which is the reconstituted total ion chromatogram for m/z 1091–1092. That is the m/z value of the [M + 3H]3+ ion of the identified iPLA2β phosphopeptide (595F-(PO4-Y616)-R622), and it is observed as a dominant peak at 43.8 min retention time for the eluate from thapsigargin-treated cells (solid line), although no such peak is observed in the eluate from vehicle-treated control cells (dashed line).

To determine whether the high molecular weight iPLA2β-immunoreactive band observed in Fig. 6B might represent a phosphorylated form of iPLA2β, a similar set of samples was generated, and effects of protein phosphatase enzymes on their electrophoretic mobilities were examined. In these experiments, His-calnexin-expressing INS-1 cells were treated with thapsigargin and lysed, and the lysates were applied to cobalt affinity columns, which were then washed to remove non-adsorbed proteins. Calnexin and associated proteins were then eluted from the columns, and the eluates were divided into aliquots that were or were not treated with protein phosphatase enzymes before SDS-PAGE analysis and immunoblotting with iPLA2β antibody. Enzymes examined included λ-protein phosphatase (which hydrolyzes phosphotyrosine, -serine, or -threonine residues) and protein phosphatase-1 (which hydrolyzes phosphoserine or -threonine but not phosphotyrosine residues). Fig. 9C illustrates that control samples not treated with a protein phosphatase exhibited both 84 and 165 kDa iPLA2β-immunoreactive bands upon SDS-PAGE analysis (Fig. 9C, lanes 1 and 3). Treating the samples with λ-protein phosphatase completely eliminated the higher molecular weight band (lane 2), whereas treating with protein phosphatase-1 left a residual high molecular weight band with an intensity similar to that of untreated samples. These results suggest that the higher molecular weight iPLA2β-immunoreactive band is a phosphorylated form of iPLA2β and that it contains a phosphotyrosine residue.

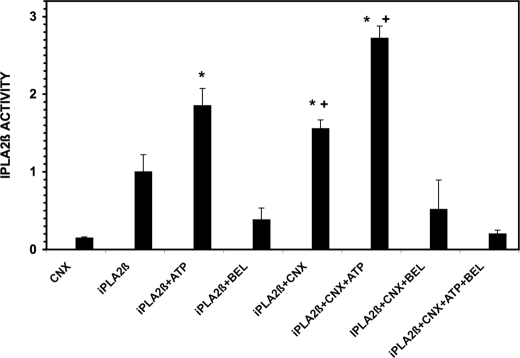

Calnexin Stimulates iPLA2β Enzymatic Activity in Vitro

To assess the potential functional significance of the iPLA2β-calnexin interaction, the influence of calnexin on the enzymatic activity of iPLA2β in vitro was determined (Fig. 10). Stably transfected INS-1 cell lines that overexpress His-tagged iPLA2β or His-tagged calnexin were prepared with lentivirus vectors, and iPLA2β and calnexin (CNX) were then purified separately after cell lysis by adsorption to immobilized metal affinity column resin and desorption with imidazole. iPLA2β activity was then determined in EGTA-containing buffer by measuring the release of [14C]linoleic acid from the phospholipid substrate 1-palmitoyl-2-[14C]linoleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine, and values were normalized to that observed with the iPLA2β preparation without other additives. As expected, the activity of the iPLA2β preparation was stimulated by ATP and inhibited by the suicide substrate BEL (Fig. 10, second, third, and fourth bars), as previously reported (3, 10, 25, 26), and the calnexin preparation itself exhibited little iPLA2β activity (Fig. 10, first bar). The addition of calnexin to iPLA2β in the absence or presence of ATP significantly increased iPLA2β activity over that observed without calnexin, and the activity retained BEL sensitivity (Fig. 10, fifth, sixth, and seventh bars).

FIGURE 10.

Effects of calnexin on Group VIB phospholipase A2 (iPLA2β) activity. The source of iPLA2β was the imidazole eluate from cobalt immobilized metal affinity columns onto which lysates of INS-1 cells that overexpress His-tagged iPLA2β had been applied. Calnexin (CNX) was prepared in a similar manner with INS-1 cells that overexpress His-calnexin. ATP (10 mm) and/or BEL (1 μm) were included in the incubation medium where indicated. Incubations were performed for 30 min at 37 °C, and PLA2 activity was measured as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Mean values are displayed, and S.E. values are indicated (error bars) (n = 6). *, significantly (p < 0.05) higher value for the condition in question and the “iPLA2β” condition, in which only iPLA2β and substrate and no calnexin, ATP, or BEL were added to the incubation medium. X denotes a significantly lower value for the condition in question and the “iPLA2β” condition. A plus sign denotes a significant difference for the values of the parameter of interest with and without calnexin. The p value for the difference between the conditions “iPLA2β” and “iPLA2β + CNX” is 0.0027, and that between “iPLA2β + ATP” and “iPLA2β + ATP” is 0.026.

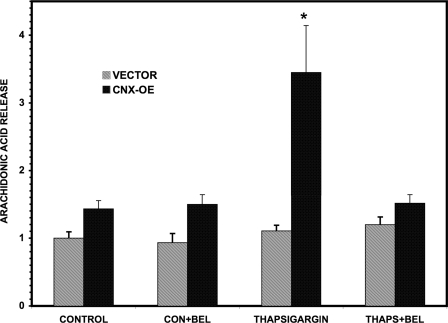

Calnexin Overexpression Augments iPLA2β-catalyzed Release of [3H]Arachidonic Acid from INS-1 Cells Induced by ER Stress

INS-1 cells that had been stably transfected with lentivirus vector to overexpress calnexin (CNX-OE) or control cells that had been treated with empty vector (VECTOR) were prelabeled with [3H]arachidonic acid and incubated with thapsigargin to induce ER stress (Fig. 11). The CNX-overexpressing cells exhibited significantly greater hydrolysis of [3H]arachidonic acid from membrane phospholipids and its release into the medium than did the vector control cells after treatment with thapsigargin, and thapsigargin-induced [3H]arachidonic acid release from the CNX-overexpressing cells was suppressed by the iPLA2β inhibitor BEL (Fig. 11), indicating that calnexin overexpression augmented ER stress-induced, iPLA2β-catalyzed release of [3H]arachidonic acid from INS-1 cells.

FIGURE 11.

Effects of calnexin Overexpression on ER stress-induced release of [3H]arachidonic acid from prelabeled cells. INS-1 cells that had been stably transfected with a lentivirus vector construct that caused them to overexpress His-calnexin (CNX-OE; dark bars) and cells transfected with empty vector only (VECTOR, light bars) were prelabeled by incubation (5 × 105 cells/well, 20 h, 37 °C) with [3H]arachidonic acid (final concentration 0.5 μCi/ml and 5 nm). To remove unincorporated radiolabel, the cells were incubated (1 h) in serum-free medium and then washed three times with glucose-free RPMI 1640 medium. Labeled cells were incubated in RPMI 1640 medium (0.5% BSA, 37 °C, 20 min) containing BEL (10 μm) or DMSO vehicle. After removal of that medium, the cells were placed in RPMI 1640 medium with 0.5% BSA that contained thapsigargin (THAPS; 1 μm) or vehicle (CONTROL or CON) and incubated (37 °C, 2 h). The cells were then collected by centrifugation, and the 3H content of the supernatant was measured by liquid scintillation spectrometry, as described under “Experimental Procedures” and elsewhere (28). The amounts of released 3H were expressed as a percentage of incorporated 3H and then normalized to the value for the vector control condition. Mean values are displayed, and S.E. values (n = 6) are indicated (error bars). *, significant difference (p < 0.05). The p values for the difference between the thapsigargin condition and the other conditions were 0.020 (versus control), 0.024 (versus control + BEL), and 0.025 (versus thapsigargin + BEL), respectively.

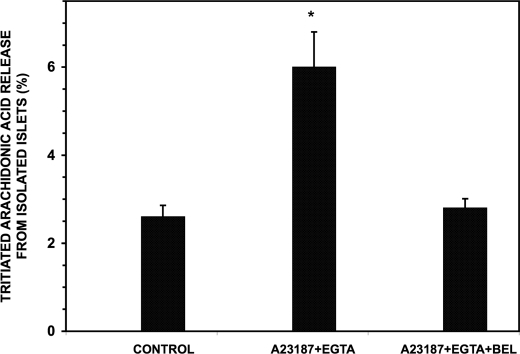

ER Stress Induced by Incubation with Ionophore A2317 and EGTA Stimulates iPLA2β-catalyzed Release of [3H]Arachidonic Acid from Isolated Pancreatic Islets and Induces Association of Calnexin and iPLA2β within Islets

To determine whether these phenomena are relevant to native pancreatic islets, we isolated islets from mice and prelabeled them with [3H]arachidonic acid and incubated them with ionophore A23187 and EGTA to induce ER stress. This results in ER Ca2+ store depletion without inhibiting SERCA and represents an alternate means to induce ER stress that is effective in many cells (6, 49) (Fig. 11). When incubated with ionophore A23187 and EGTA, the isolated pancreatic islets exhibited significantly greater hydrolysis of [3H]arachidonic acid from membrane phospholipids and its release into the medium than did islets incubated in Ca2+-replete medium in the absence of ionophore, and this ER stress-induced [3H]arachidonic acid release from the islets was suppressed by the iPLA2β inhibitor BEL (Fig. 12).

FIGURE 12.

Release of [3H]arachidonic acid from prelabeled pancreatic islets subjected to ER stress with ionophore A23187 and EGTA. Pancreatic islets isolated from mice were incubated with [3H]arachidonic acid (1 μCi, 20 h) and washed free of unincorporated radiolabel as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The islets were then divided into aliquots that were preincubated with vehicle (left and center bar) or BEL (10 μm; right bar). After removal of the preincubation medium and washing, islets were incubated with DMSO in Ca2+-replete medium (CONTROL) or with ionophore A23187 (10 μm) in buffer containing EGTA (0.5 mm, right and center bars). The 3H content of the supernatant was measured by liquid scintillation spectrometry, as in Fig. 11, and amounts of released 3H were expressed as a percentage of incorporated 3H for each condition. Results are expressed as mean ± S.E. (error bars) (n = 7). *, significant difference (p < 0.05) from the control value.

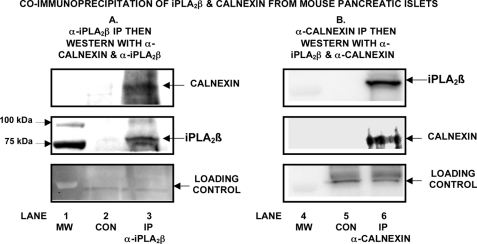

Moreover, when islets were subjected to ER stress and lysed, the lysate was subjected to immunoprecipitation with an anti-iPLA2β antibody, and the immunoprecipitate was analyzed by SDS-PAGE, a calnexin-immunoreactive band was visualized upon Western blotting (Fig. 13). This indicates that ER stress induces association of iPLA2β with calnexin in native islets at endogenous expression levels in a manner similar to that observed with INS-1 cells in which one of the interacting partners is overexpressed. This interaction of iPLA2β and calnexin in native islets subjected to ER stress was confirmed in similar experiments in which immunoprecipitation was performed with anti-calnexin antibody and the immunoprecipitate was analyzed by SDS-PAGE followed by Western blotting with an antibody against iPLA2β (Fig. 13B).

FIGURE 13.

Co-Immunoprecipitation of iPLA2β and calnexin from pancreatic islets isolated from mice. In A, pancreatic islets (∼1250) were isolated from C57BL/6J wild-type mice and subjected to ER stress as in Fig. 12. A lysate was then prepared in immunoprecipitation buffer containing 2% CHAPS. The lysate was divided into two aliquots, and one was incubated with Protein A-agarose and 20 μl of fetal bovine serum (20 μl) as a control (CON). The other aliquot was incubated with Protein A-agarose and a rabbit antibody (20 μl) directed against iPLA2β to effect immunoprecipitation (IP). The resultant immunoprecipitate was then analyzed by SDS-PAGE, transferred to PVDF membrane, and probed with rabbit antibody directed against calnexin (upper panel). After stripping, the blot was then probed with goat antibody directed against iPLA2β (middle panel). The lower panel represents a loading control probed with anti-calnexin antibody. In B, islets (∼1160) were isolated from RIP-iPLA2β-transgenic mice (30) and lysed as above, and the lysate was divided into two aliquots, one of which was incubated with Protein A-agarose and fetal bovine serum as control (CON). The other was incubated with Protein A-agarose and rabbit anti-calnexin antibody (rabbit). The resultant immunoprecipitate (IP) was analyzed by SDS-PAGE, transferred to a PVDF membrane, and probed with T-14 antibody directed against iPLA2β (upper panel). After stripping, the blot was probed with mouse anti-calnexin antibody (middle panel). The lower panel represents a loading probed with T-14 anti-iPLA2β antibody. Displayed results are representative of three independent experiments. MW, molecular weight standards.

DISCUSSION

Depletion of ER Ca2+ stores with thapsigargin or other SERCA inhibitors or by other means has long been known to result in the activation of iPLA2β in a variety of cells, including insulin-secreting β-cells (12, 31, 32, 35. 44–48), vascular myocytes (6, 49), and macrophages (29), and this is associated with subcellular redistribution of iPLA2β from ER to mitochondria (29, 35, 45–48), mitochondrial phospholipid hydrolysis (29, 31, 48), cytochrome c release (29), and apoptosis (12, 29, 32, 35, 45–47). How the filling state of ER Ca2+ stores is communicated to iPLA2β and how this results in iPLA2β activation have not been clearly established.

The findings here raise the possibility that the ER-resident protein calnexin could be affected by ER Ca2+ content, which might, for example, influence the conformation of the protein in such a way as to promote association with and thereby activate iPLA2β, possibly in concert with phosphorylation. Thapsigargin activates protein kinase cascades that include the Src tyrosine kinase (50) in cultured cells, and induction of ER stress promotes association of a phosphorylated form of Group IVA PLA2 (cPLA2α) with ER membranes and its colocalization with calnexin (51). This is associated with cPLA2α activation, membrane phospholipid hydrolysis, arachidonic acid release, enhancement of the unfolded protein response, and apoptosis (51). These observations suggest that activation of intracellular PLA2 enzymes might be important in the evolution of the unfolded protein response and apoptosis induced by ER stress, and iPLA2β appears to be a major regulator of mitochondrial content of cardiolipin (52), a phospholipid that associates with cytochrome c and is important for its mitochondrial retention (53).

It is now recognized that ER and mitochondria interact physically at the “mitochondria-associated ER membrane” (MAM), which plays important roles in non-vesicular transport of phospholipids, transmission of Ca2+ from ER to mitochondria, and control of apoptosis, and molecular chaperones, including calnexin, regulate the association of the two organelles (54). Under resting conditions, the vast majority of cellular calnexin localizes to the ER, and it resides predominantly at the MAM (55). Calnexin can also regulate the activity of the ER Ca-ATPase (SERCA) via a direct protein-protein interaction that is controlled by phosphorylation of the cytoplasmic tail of calnexin (56, 57).

Our characterization here of the iPLA2β interactome indicates that SERCA also associates with iPLA2β, and it is possible that this reflects assembly of a macromolecular supercomplex at the MAM involved in Ca2+ signaling and cell fate decisions that includes calnexin, SERCA, iPLA2β, and perhaps CaMK2, which we have observed here and previously (24) to be a member of the iPLA2β interactome and which has recently been reported to link ER stress with the mitochondrial apoptosis pathway (58). Calnexin has also been reported to regulate apoptosis induced by ER stress or other mechanisms (59–62), and thus at least three members of the iPLA2β interactome (SERCA, CaMK2, and calnexin) and iPLA2β itself have been reported to participate in ER stress-induced apoptosis.

One mechanism of calnexin association with other proteins involves recognition of the Glc1Man9GlcNAc2 epitope attached to Asn residues in nascent polypeptide chains entering the lumen of the ER (63). Such calnexin lectin binding is part of a cycle that also involves glycan processing by glucosidases I and II and UDP-glucose:glycoprotein glucosyltransferase, and the cycle functions to allow properly folded proteins to traffic out of the ER while misfolded proteins are retained for further folding or degradation (63). Calnexin can also interact with other proteins by polypeptide domains (40, 41), however, and conditions such as Ca2+ depletion cause the calnexin conformation to change in a manner that favors such interactions (40). The observations reported here suggest that polypeptide domain-mediated interaction represents the means by which calnexin associates with iPLA2β, which has several domains that resemble those in other proteins that mediate protein-protein interactions (1–3, 5, 20, 64).

In summary, we have identified by affinity chromatography and LC/MS/MS a total of 37 proteins that associate with iPLA2β in stably transfected INS-1 insulinoma cells that overexpress FLAG-iPLA2β, and many of them are mitochondrial or ER proteins. This is consistent with previous reports that induction of ER stress activates iPLA2β and causes its subcellular distribution, including increased association with mitochondria (29, 31, 32, 35, 45, 47, 48). The SERCA inhibitor thapsigargin is widely used to induce ER stress, and it increases the association of iPLA2β and the ER protein calnexin, perhaps by triggering changes in the conformation of calnexin and/or post-translational modification of iPLA2β. Our data suggest that glycosylation of iPLA2β is not stimulated under these conditions and that calnexin interacts with iPLA2β via a polypeptide domain and not through an attached oligosaccharide.

LC/MS/MS analyses of phosphopeptides captured with TiO2 columns from tryptic digests of thapsigargin-treated INS-1 lysates demonstrate that the iPLA2β tryptic peptide Phe595–Arg622 is phosphorylated on Tyr616 when INS-1 cells are treated with thapsigargin and that tyrosine-phosphorylated iPLA2β associates with calnexin. The phosphorylated form of iPLA2β produced under these conditions can be dephosphorylated with λ-protein phosphatase, which hydrolyzes phosphotyrosine as well as phosphoserine and phosphothreonine residues. The likely functional significance of the interaction is reflected by the facts that co-incubating calnexin with iPLA2β increases iPLA2β activity in vitro and that overexpression of calnexin in INS-1 cells results in augmentation of ER stress-induced, iPLA2β-catalyzed hydrolysis of arachidonic acid from membrane phospholipids.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Alan Bohrer for excellent technical assistance; Robert Sanders for assistance in preparing the manuscript and figures; and Dr. Sasanka Ramanadham for advice, discussion, and a critical reading of the manuscript.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health United States Public Health Service Grants R37-DK34388, P41-RR00954, P60-DK20579, and P30-DK56341.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Table 1.

- PLA2

- phospholipase A2

- iPLA2β

- Group VIA PLA2

- CaMK2

- calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase 2

- CNX

- calnexin

- cPLA2α

- group IVA phospholipase A2

- ER

- endoplasmic reticulum

- MAM

- mitochondria-associated ER membrane

- OE

- overexpressing

- SERCA

- sarco(endo)plasmic reticulum ATPase

- VO

- vector only.

REFERENCES

- 1.Tang J., Kriz R. W., Wolfman N., Shaffer M., Seehra J., Jones S. S. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272, 8567–8575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Balboa M. A., Balsinde J., Jones S. S., Dennis E. A. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272, 8576–8580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ma Z., Ramanadham S., Kempe K., Chi X. S., Ladenson J., Turk J. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272, 11118–11127 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yang H. C., Mosior M., Ni B., Dennis E. A. (1999) J. Neurochem. 73, 1278–1287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ma Z., Wang X., Nowatzke W., Ramanadham S., Turk J. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 9607–9616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moon S. H., Jenkins C. M., Mancuso D. J., Turk J., Gross R. W. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 33975–33987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Balsinde J., Balboa M. A., Dennis E. A. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272, 29317–29321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baburina I., Jackowski S. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 9400–9408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Owada S., Larsson O., Arkhammar P., Katz A. I., Chibalin A. V., Berggren P. O., Bertorello A. M. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 2000–2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ramanadham S., Song H., Hsu F. F., Zhang S., Crankshaw M., Grant G. A., Newgard C. B., Bao S., Ma Z., Turk J. (2003) Biochemistry 42, 13929–13940 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Atsumi G., Murakami M., Kojima K., Hadano A., Tajima M., Kudo I. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 18248–18258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ramanadham S., Hsu F. F., Zhang S., Jin C., Bohrer A., Song H., Bao S., Ma Z., Turk J. (2004) Biochemistry 43, 918–930 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jenkins C. M., Han X., Mancuso D. J., Gross R. W. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 32807–32814 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smani T., Domínguez-Rodríguez A., Hmadcha A., Calderón-Sánchez E., Horrillo-Ledesma A., Ordóñez A. (2007) Circ. Res. 101, 1194–1203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Williams S. D., Ford D. A. (2001) Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 281, H168–H176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moran J. M., Buller R. M., McHowat J., Turk J., Wohltmann M., Gross R. W., Corbett J. A. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 28162–28168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xie Z., Gong M. C., Su W., Turk J., Guo Z. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 25278–25289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Murakami M., Kambe T., Shimbara S., Kudo I. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 3103–3115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tay H. K., Melendez A. J. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 22505–22513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ma Z., Turk J. (2001) Prog. Nucleic Acids Res. Mol. Biol. 67, 1–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lux S. E., John K. M., Bennett V. (1990) Nature 344, 36–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bourguignon L. Y., Jin H. (1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270, 7257–7260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kordeli E., Ludosky M. A., Deprette C., Frappier T., Cartaud J. (1998) J. Cell Sci. 111, 2197–2207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang Z., Ramanadham S., Ma Z. A., Bao S., Mancuso D. J., Gross R. W., Turk J. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 6840–6849 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ramanadham S., Hsu F. F., Bohrer A., Ma Z., Turk J. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 13915–13927 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ma Z., Ramanadham S., Wohltmann M., Bohrer A., Hsu F. F., Turk J. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 13198–13208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thingholm T. E., Jørgensen T. J., Jensen O. N., Larsen M. R. (2006) Nat. Protoc. 1, 1929–1935 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Song H., Bao S., Ramanadham S., Turk J. (2006) Biochemistry 45, 6392–6406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bao S., Li Y., Lei X., Wohltmann M., Jin W., Bohrer A., Semenkovich C. F., Ramanadham S., Tabas I., Turk J. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 27100–27114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bao S., Jacobson D. A., Wohltmann M., Bohrer A., Jin W., Philipson L. H., Turk J. (2008) Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 294, E217–E229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Seleznev K., Zhao C., Zhang X. H., Song K., Ma Z. A. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 22275–22288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lei X., Zhang S., Bohrer A., Ramanadham S. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 34819–34832 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Neupert W. (1997) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 66, 863–917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Song H., Hecimovic S., Goate A., Hsu F. F., Bao S., Vidavsky I., Ramanadham S., Turk J. (2004) J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 15, 1780–1793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Song H., Bao S., Lei X., Jin C., Zhang S., Turk J., Ramanadham S. (2010) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1801, 547–558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Szegezdi E., Logue S. E., Gorman A. M., Samali A. (2006) EMBO Rep. 7, 880–885 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kleizen B., Braakman I. (2004) Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 16, 343–349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dickson K. M., Bergeron J. J., Shames I., Colby J., Nguyen D. T., Chevet E., Thomas D. Y., Snipes G. J. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 9852–9857 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ou W. J., Bergeron J. J., Li Y., Kang C. Y., Thomas D. Y. (1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270, 18051–18059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thammavongsa V., Mancino L., Raghavan M. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 33497–33505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pollock S., Kozlov G., Pelletier M. F., Trempe J. F., Jansen G., Sitnikov D., Bergeron J. J., Gehring K., Ekiel I., Thomas D. Y. (2004) EMBO J. 23, 1020–1029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lin L. L., Wartmann M., Lin A. Y., Knopf J. L., Seth A., Davis R. J. (1993) Cell 72, 269–278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.de Carvalho M. G., McCormack A. L., Olson E., Ghomashchi F., Gelb M. H., Yates J. R., 3rd, Leslie C. C. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271, 6987–6997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nowatzke W., Ramanadham S., Ma Z., Hsu F. F., Bohrer A., Turk J. (1998) Endocrinology 139, 4073–4085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lei X., Zhang S., Bohrer A., Bao S., Song H., Ramanadham S. (2007) Biochemistry 46, 10170–10185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lei X., Zhang S., Barbour S. E., Bohrer A., Ford E. L., Koizumi A., Papa F. R., Ramanadham S. (2010) J. Biol. Chem. 285, 6693–6705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lei X., Barbour S. E., Ramanadham S. (2010) Biochimie 92, 627–637 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhao Z., Zhang X., Zhao C., Choi J., Shi J., Song K., Turk J., Ma Z. A. (2010) Endocrinology 151, 3038–3048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wolf M. J., Wang J., Turk J., Gross R. W. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272, 1522–1526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chao T. S., Abe M., Hershenson M. B., Gomes I., Rosner M. R. (1997) Cancer Res. 57, 3168–3173 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ren G., Takano T., Papillon J., Cybulsky A. V. (2010) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1803, 468–481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Malhotra A., Edelman-Novemsky I., Xu Y., Plesken H., Ma J., Schlame M., Ren M. (2009) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 2337–2341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kagan V. E., Bayir H. A., Belikova N. A., Kapralov O., Tyurina Y. Y., Tyurin V. A., Jiang J., Stoyanovsky D. A., Wipf P., Kochanek P. M., Greenberger J. S., Pitt B., Shvedova A. A., Borisenko G. (2009) Free Radic. Biol. Med. 46, 1439–1453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hayashi T., Rizzuto R., Hajnoczky G., Su T. P. (2009) Trends Cell Biol. 19, 81–88 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Myhill N., Lynes E. M., Nanji J. A., Blagoveshchenskaya A. D., Fei H., Carmine Simmen K., Cooper T. J., Thomas G., Simmen T. (2008) Mol. Biol. Cell 19, 2777–2788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Roderick H. L., Lechleiter J. D., Camacho P. (2000) J. Cell Biol. 149, 1235–1248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chevet E., Smirle J., Cameron P. H., Thomas D. Y., Bergeron J. J. (2010) Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 21, 486–490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Timmins J. M., Ozcan L., Seimon T. A., Li G., Malagelada C., Backs J., Backs T., Bassel-Duby R., Olson E. N., Anderson M. E., Tabas I. (2009) J. Clin. Invest. 119, 2925–2941 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Takizawa T., Tatematsu C., Watanabe K., Kato K., Nakanishi Y. (2004) J. Biochem. 136, 399–405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Delom F., Fessart D., Chevet E. (2007) Apoptosis 12, 293–305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mohan C., Lee G. M. (2009) Cell Stress Chaperones 14, 49–60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Guérin R., Beauregard P. B., Leroux A., Rokeach L. A. (2009) PLoS One 4, e6244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Caramelo J. J., Parodi A. J. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 10221–10225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Turk J., Ramanadham S. (2004) Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 82, 824–832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.