Abstract

The activity of Cdk5-p35 is tightly regulated in the developing and mature nervous system. Stress-induced cleavage of the activator p35 to p25 and a p10 N-terminal domain induces deregulated Cdk5 hyperactivity and perikaryal aggregations of hyperphosphorylated Tau and neurofilaments, pathogenic hallmarks in neurodegenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer disease and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, respectively. Previously, we identified a 125-residue truncated fragment of p35 called CIP that effectively and specifically inhibited Cdk5-p25 activity and Tau hyperphosphorylation induced by Aβ peptides in vitro, in HEK293 cells, and in neuronal cells. Although these results offer a possible therapeutic approach to those neurodegenerative diseases assumed to derive from Cdk5-p25 hyperactivity and/or Aβ induced pathology, CIP is too large for successful therapeutic regimens. To identify a smaller, more effective peptide, in this study we prepared a 24-residue peptide, p5, spanning CIP residues Lys245–Ala277. p5 more effectively inhibited Cdk5-p25 activity than did CIP in vitro. In neuron cells, p5 inhibited deregulated Cdk5-p25 activity but had no effect on the activity of endogenous Cdk5-p35 or on any related endogenous cyclin-dependent kinases in HEK293 cells. Specificity of p5 inhibition in cortical neurons may depend on the p10 domain in p35, which is absent in p25. Furthermore, we have demonstrated that p5 reduced Aβ(1–42)-induced Tau hyperphosphorylation and apoptosis in cortical neurons. These results suggest that p5 peptide may be a unique and useful candidate for therapeutic studies of certain neurodegenerative diseases.

Keywords: Cdk (Cyclin-dependent Kinase), Enzyme Inhibitors, Neurobiology, Neurodegeneration, Peptides

Introduction

The activity of Cdk5, a multifunctional serine/threonine kinase, is critical for neuronal development and synaptic activity; it sustains neurite outgrowth, neuronal migration, cortical lamination, and survival (1–9). Its activity depends on the binding of its neuron-specific, cyclin-related activators, p35 and p39 (10, 11). Cdk5 has also been implicated as a key player in learning and memory (12–15).

Normally, Cdk5 activity is tightly regulated, but under conditions of neuronal stress, it is deregulated, leading to hyperactivity, neuronal pathology, and cell death. Accordingly, Cdk5 has been implicated in certain neurodegenerative disorders, such as AD.2 A model of the role of Cdk5 in neurodegeneration suggests that a stress-induced influx of calcium ions into neurons activates calpain, a Ca2+-activated protease, which cleaves p35 into p25 and a p10 fragment. p25, in turn, forms a more stable Cdk5-p25 hyperactive complex, which hyperphosphorylates Tau and induces cell death (16–21). Indeed, increased levels of p25 and Cdk5 activity have been reported in AD brains. The finding that p25 may be toxic comes from studies of cortical neurons treated with β-amyloid (Aβ), a key marker of AD pathology, where p35 is converted to p25 accompanied by activated Cdk5, Tau hyperphosphorylation, and apoptosis (22, 23).

Expression of the Cdk5-p25 complex seems to be primarily responsible for the Tau pathology and suggests that a therapeutic approach directed specifically at this target might prove successful (24–26). For most of these studies, however, the focus has been on aminothiazol compounds resembling roscovitine, a kinase inhibitor that competes with the ATP binding site in Cdk5 and other kinases. These drugs do not act specifically on Cdk5-p25 but also inhibit Cdk5-p35 and other Cdks essential for normal development and function. This could be responsible for serious secondary side effects and thereby compromise any therapeutic value.

Our approach to this problem, however, is based on earlier studies, where we identified a peptide of 125 amino acid residues of p35 (CIP) that inhibited Cdk5-p25 activity and rescued cortical neurons from Aβ-induced apoptosis without affecting Cdk5-p35 activity (27). This approach might prove to be a more effective way to suppress deregulated Cdk5-p25 hyperactivity inducing neurodegenerative pathology. For a therapy to be effective, however, it must be small enough to pass the blood-brain barrier; a large peptide of 125 residues may be problematic, to say the least. For that reason, we set out to produce a smaller peptide of CIP with equivalent specificity. Based on an analysis of Cdk5-p25 structure and molecular dynamics, several smaller peptides were produced and tested. We identified a 24-residue peptide, called p5, that more effectively inhibited Cdk5-p25 activity in cortical neurons than CIP without affecting endogenous Cdk5-p35 or other Cdks. The small size and specificity of p5 inhibition make it an excellent candidate for therapeutic trials in animal models of AD.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

p35 (C-19) polyclonal antibody, Cdk5 (C-8) polyclonal antibody, and Cdk5 (J-3) monoclonal antibody at 1:500 dilutions, Cdc2 anti-PSTAIR antibody, and Cdk2, Cdk4, and Cdk6 antibodies were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Santa Cruz, CA), all used at 1:300–500 dilutions. Phospho-Tau-Ser199/Ser202, PHF1, Tau1, and Tau5 monoclonal antibodies were obtained from BIOSOURCE International Inc. (Camarillo, CA) and used at 1:1000 and 1:500 dilutions, respectively. AT-8 and AT180 antibodies were purchased from Thermo Scientific (Rockford, IL) and used at 1:500. Phospho-Tau-Ser422 was purchased from GenScript (Piscataway, NJ) and used at 1:1000. Other antibodies include caspase-3 and cleaved caspase-3 obtained from Cell Signaling Technologies (Beverly, MA) and used at 1:1000 dilutions, whereas β-tubulin antibody from Sigma was used at 1:2000. Secondary horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antibodies were obtained from Amersham Biosciences and used at 1:2000. Secondary fluorescence-conjugated Oregon Green and Texas Red antibodies (Invitrogen) were used at 1:400. Cdk5 inhibitor roscovitine was obtained from Biomol Research Laboratories, Inc. (Plymouth Meeting, PA). p5 peptide was synthesized by 21st Century Biochemicals (Marlboro, MA).

Plasmids and Generation of Recombinant Adenoviruses

The AdEasy system was kindly provided by Dr. Bert Vogelstein (Howard Hughes Medical Institute and Molecular Genetics Laboratory, Johns Hopkins Oncology Center, Baltimore, MD). A series of Cdk5-related genes were generated by PCR with the following primers with additional restriction enzyme (NotI and EcoRV) sequences underlined and Myc tag sequences capitalized: 1) p35, forward primer (tttgcggccgccAtgggcacggtgctgtccct) and reverse primer (tttgatatcttaccgatccaggcctagga; 2) p25 forward primer (tttgcggccgccAtggcccagcccccaccggccca) and reverse primer (the same as p35); 3) Cdk5, forward primer (tttgcggccgccAtgcagaaatacgagaaactgga) and reverse primer (tttgatatcttagggcggacagaagtcgg); 4) p5, forward primer (tttgcggccgccATGGCATCAATGCAGAAGCTGATCTCAGAGGAGGACCTGAtgaaggaggccttttgggaccg) and reverse primer (tttgatatcttaggcatttatctgcagcatcttt). Recombinant adenoviruses were generated according to the protocol (28). Briefly, all PCR fragments were cloned into a shuttle vector, pAdTrack-CMV. The resultant plasmids were linearized and subsequently co-transformed into Escherichia coli BJ5183 cells with an adenoviral backbone plasmid pAdEasy-1. Recombinants were linearized and transfected into 293-1 cells to generate the recombinant adenoviruses. High viral titers were purified by CsCl banding and mixed with 2× Storage Buffer (10 mm Tris, pH 8.0, 100 mm NaCl, 0.1% BSA, and 50% glycerol, filter-sterilized). Viruses were stored as stocks at −20 or −70 °C. The titers of virus were checked by GFP when infected with related cells.

Cell Culture, Transfection, and Infection

Primary cultures of rat cortical neurons were prepared from E-18 rat fetuses as described previously (29). After 7 days, cells were infected independently or co-infected with empty vector (EV), the constructs of p5, p25, p35, wild-type Cdk5, and dominant negative Cdk5 (changing Lys33 to Thr33) using the adenoviral vector (pAdTrack-CMV) packaging system as described above. After 48 h, cells were treated with roscovitine (20 μm) for 1 h and/or for 6 h with 10 μm Aβ(1–42) (incubated at 37 °C for 7 days before use). The cells were fixed for immunocytochemistry analyses or lysed with lysis buffer for immunoprecipitation and Western blot analyses.

Cortical neuron cultures were prepared and plated on the coverslips as described. Human embryo kidney cells (HEK293) were grown as described previously (27). In these experiments, HEK293 cells on day 1 or neurons on day 5 were transfected with or without Myc-p5-GFP using Lipofectamine 2000 following the manufacturer's instructions.

Western Blot Analysis

Western blot analysis was performed as described previously (27). In brief, an equal amount of total protein (20 μg/lane) was resolved on a 4–20% SDS-polyacrylamide gel and blotted onto a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane. This membrane was incubated in blocking buffer containing 20 mm Tris-HCI (pH 7.4), 150 mm NaCl, and 0.1% (v/v) Tween 20 (TTBS) plus 5% dry milk (w/v) for 1 h at room temperature followed by incubation overnight at 4 °C in primary antibodies. The membranes were then washed four times in TTBS (5 min/each), followed by incubation in secondary antibody (goat anti-mouse or goat anti-rabbit IgG (H+L)-HRP conjugate at a dilution of 1:3000) for 1 h at room temperature. Western blots were analyzed using the Amersham Biosciences ECL kit following the manufacturer's instructions (GE Healthcare).

Immunoprecipitation and Kinase Assays

Kinase assays were performed as described previously (30). Briefly, 7 days in culture (DIC) primary rat cortical neurons were infected with p25, p35, Cdk5 wild type, dominant negative Cdk5, and p5 using the lentiviral gene delivery as described earlier. Cdk5 was immunoprecipitated using the polyclonal C8 antibody overnight at 4 °C, and immunoglobulin was isolated using Protein A-Sepharose beads for 2 h at 4 °C. Immunoprecipitates were washed three times with lysis buffer and then once with 1× kinase buffer containing 20 mm Tris-Cl, pH 7.4, 1 mm EDTA, 1 mm EGTA, 10 mm MgCl2, 10 mm sodium fluoride, and 1 mm sodium orthovanadate.

Endogenous Cdks were immunoprecipitated from HEK293 cells using their respective antibodies and treated as above. Kinase assays were performed in the same buffer containing 1 mm DTT, 0.1 mm ATP, and 0.185 MBq of [γ-32P]ATP with 20 μg of histone H1 as the substrate. Phosphorylation was performed in a final volume of 50 μl, incubated at 30 °C for 60 min, and stopped by the addition of 10% SDS sample buffer and heating at 95 °C for 5 min. Samples were separated by SDS-PAGE, and gels were stained with Coomassie, destained, dried, and exposed to autoradiography. In pad assays, 25-μl aliquots of the incubation mixture were placed on a Whatman p80 paper square, washed and dried, and placed in a scintillation vial for counting.

Effect of Tubulin Polymerization on Cdk5 Activity

Tubulin polymerization was performed as detailed in a previous report (31). Briefly, active kinase Cdk5-p35 (2 ng/μl) or active Cdk5-p25 (1 ng/μl) was incubated with β-tubulin (enzyme/tubulin at 1:100) in PEM buffer (80 mm PIPES, 2 mm MgCl2, 1 mm EGTA, pH 7.0) supplemented with 1 mm GTP at 35 °C for 45 min. Following the incubation, Cdk5 kinase assays were performed with or without the addition of 0.45 or 0.90 μm p5.

Immunocytochemistry

Immunocytochemistry analysis was performed as described previously (23). Briefly, cells were fixed on coverslips for 30 min at room temperature in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS and then permeabilized and blocked in 5% FBS with 0.1% Triton X-100 in 1× PBS for 1 h. The coverslips were incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies diluted in blocking buffer. After a wash in PBS (three times, 15 min each) the coverslips were incubated with fluorescein goat anti-mouse IgG or Texas Red goat anti-rabbit IgG and secondary antibody for 1 h at room temperature. This was followed by washing three times with PBS and mounting in an aqueous medium. Fluorescent images were obtained with a Zeiss LSM-510 laser-scanning confocal microscope. Images were processed and merged by Adobe Photoshop software.

TUNEL Assay for Apoptosis

Primary cortical neuron cells were cultured for 5 days on glass coverslips coated with poly-l-lysine and transfected with or without p5 using Lipofectamine 2000. After 24 h, TUNEL staining was done according to the manufacturer's instructions. Cells were washed three times in PBS, fixed for 1 h at room temperature in fresh 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS, and permeabilized (0.1% Triton X-100 in 0.1 sodium citrate) for 2 min on ice. After washing two times with PBS, TUNEL reaction mixture (50 μl) was added and incubated in a humidified atmosphere at 37 °C for 1 h. TUNEL staining and fluorescent images were visualized with a Zeiss LSM-510 laser-scanning confocal microscope. Images were processed and merged by Adobe Photoshop software.

RESULTS

Identification of Cdk5-inhibitory Peptides Derived from p35

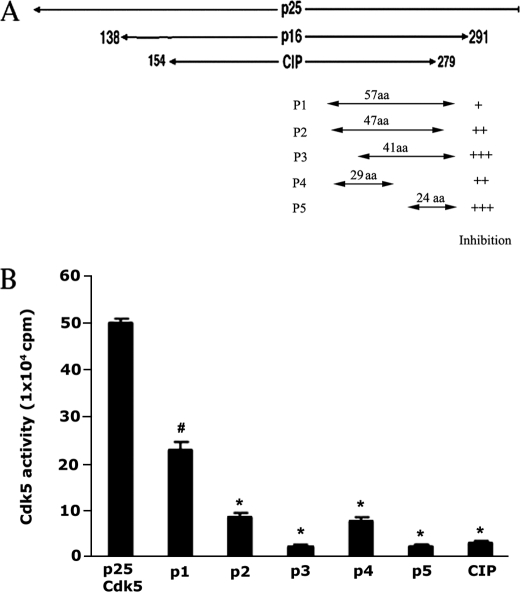

As demonstrated in our previous studies, CIP, a 125-amino acid truncated peptide from p35 (residues 154–279), is a highly effective and specific inhibitor of Cdk5-p25 activity. It reduces Tau hyperphosphorylation and protects transfected HEK cells and neurons from apoptosis induced by Cdk5-p25 (23, 27, 32–42). To produce a smaller and more effective inhibitory peptide of Cdk5-p25 for potential therapeutic use, we designed and constructed five short peptides in GST vectors, as shown in Fig. 1A. These are GST-p1 (Glu211–Ala277), 67 amino acid residues; GST-p2 (Met237–Ala277), 41 residues; GST-p3 (Glu221-Leu267), 47 residues; GST-p4 (Glu221–Leu249), 29 residues; and GST-p5 (Lys254–Ala277), 24 residues. Each was incubated with active Cdk5-p25 in a kinase assay in vitro. The results indicated that all short peptides inhibited Cdk5-p25 activities significantly, but only p3 and p5 are more effective inhibitors than CIP (Fig. 1B). Although both exhibit almost 100% inhibition in vitro, we chose to study p5 in detail because it is the smaller fragment. Moreover, molecular dynamics simulations revealed that residues Glu255, Trp259, and Ala233 of the p5 peptide bind to the PSSALRE motif of Cdk5, further supporting a potent inhibitor role for p5.

FIGURE 1.

Identification of Cdk5-inhibitory peptides derived from p25. A, a schematic diagram of p25 truncated peptides showing the CIP peptide from which five short peptides (p1–p5) were derived. p5 was the shortest and best inhibitor of Cdk5-p25 in an in vitro assay with histone H1 as substrate. B, a histogram summary comparison of the inhibitory effects of peptides derived from CIP in a standard in vitro pad assay of Cdk5-p25 activity. p3 and p5 were the most effective inhibitors under these conditions, reducing activity more than 90%. Data represent the mean ± S.E. (error bars) of three independent experiments. *, p < 0.01. aa, amino acids.

p5 Inhibits Both Cdk5-p25 and Cdk5-p35 Activities in Vitro; a Dose-dependent Study

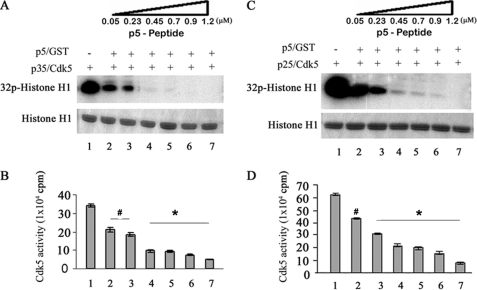

In a dose-dependent kinase assay, we compared the effective inhibitory concentration of p5 for both the Cdk5-p25 and Cdk5-p35 complexes. His-p5 peptide was added at different concentrations to the in vitro assay containing 100 μm [γ32-P]ATP and histone H1. The results are shown in Fig. 2. We found that inhibition increased progressively with increasing p5 concentration in both complexes (Fig. 2, compare A and B with C and D). Although Cdk5-p25 activity is significantly greater, the kinetics of inhibition was similar for both enzyme complexes. For example, at 0.05 μm p5, activities of both Cdk5-p35 and Cdk5-p25 were inhibited at about 30%, (compare lanes 2 in B and D), whereas 1.2 μm p5 virtually eliminated activity in both cases (compare lanes 7 in B and D). Under these in vitro conditions, p5 inhibition was not specific for Cdk5-p25.

FIGURE 2.

p5 equally inhibits both Cdk5-p25 and Cdk5-p35 activities in vitro (a dose-dependent analysis). Activated Cdk5-p35 and Cdk5-p25 were used in a comparative test tube assay of the inhibitory effect of p5 with histone H1 as the substrate. p5 as p5-GST was added at a range of concentrations from 0.05 to 1.2 μm. After SDS-PAGE, autoradiographs were prepared as shown in A and C, and pad assay scintillation counts were quantified from three separate experiments as summarized in the bar graphs (B and D). Note that initially, the Cdk5-p25 activity is twice that of the Cdk5-p35 activity. The levels of inhibition, however, are almost identical, although it might appear from the autoradiograms that the Cdk5-p35 activity is more sensitive because it seems completely inhibited at 0.45 μm, whereas Cdk5-p25 activity is evident at least to 0.9 μm in the sample shown. This is due to the initially higher activity of the Cdk5-p25 complex. The quantitative data (B and D), however, show that p5 equally inhibits each Cdk5 complex in a dose-dependent manner when compared with lanes 1 in B and D, respectively; at 0.05 μm (lane 2), p5 peptide inhibits 36% of Cdk5-p35 activity and ∼33% of Cdk5-p25 activity, whereas 0.7 μm (lane 5) inhibits both complexes ∼70%, and finally at 1.2 μm (lane 6), both are inhibited ∼90%. *, p < 0.01; #, p < 0.05. Error bars, S.E.

p5 Inhibits Cdk5-p25 Activity without Affecting Endogenous Cdk5-p35 Activity in Cortical Neurons

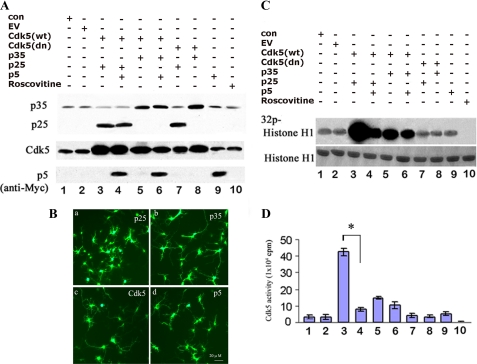

If specificity of p5 inhibition is not evident in vitro, is it present in cortical neurons? To examine this question we used E-18 rat cortical neurons co-infected with Cdk5 and p5, p35, or p25 in various constructs. The AdEasy-based viral infection system, used to introduce the appropriate genes into cortical neurons, typically yielded ∼60–70% efficiency (Fig. 3B). We utilized Western blotting with the appropriate antibodies to examine the expression of Cdk5, p35, and p25 genes in cortical neurons (Fig. 3, A and B). Neurons were infected at 5 DIC, and lysates were harvested after 48 h to ensure proper integration and infection rates and high expression levels. As seen in Fig. 3A, infected Cdk5 showed dramatically higher expression (lanes 3–8) compared with controls (con), EV (lanes 1 and 2), and p5 only (lane 9). Infected p35 and p25 also showed robust increases in the amounts of expressed protein (lanes 5, 6, and 8 and lanes 3, 4, and 7, respectively). Endogenous p35 (lanes 1–4, 7, 9, and 10) was expressed at much lower levels when compared with endogenous Cdk5 (lanes 1, 2, 9, and 10), whereas p25 showed no endogenous expression.

FIGURE 3.

p5 inhibits Cdk5-p25 activity without affecting endogenous Cdk5-p35 activity in cortical neurons. A, to determine the effect of p5 on Cdk5-p35 and Cdk5-p25 activity in infected neurons, E-18 rat cortical neurons after 5 DIC were infected with different gene constructs using adenoviral vector as follows: co-infected with Cdk5-p25, Cdk5-p35, dominant negative Cdk5-p25, and dominant negative Cdk5-p35 or triply infected with GFP-Myc-p5, except for cells that were infected with GFP-Myc-p5 alone and one group of uninfected cells treated with 20 μm roscovitine as a control. After SDS-PAGE and Western analysis with the specific antibodies, the expression level of each of the constructs is shown. B, the expressions of cells infected with p25 (a), p35 (b), Cdk5 (c), and p5 (d). C, Cdk5 activity was measured in Cdk5 immunoprecipitates (IP) from lysates of these infected cells (from A) using histone H1 as a substrate. The top panel is the autoradiograph, and the bottom panel shows the corresponding Coomassie-stained histone H1 bands. D, a histogram showing quantitative scintillation count data (cpm) from corresponding pad assays of kinase activities from the same lysates. Data represent means ± S.E. (error bars) of three separate experiments. *, p < 0.01.

To determine the specificity of p5 inhibition in cortical neurons, Cdk5 immunoprecipitates were prepared from each infected culture, and kinase activity was assayed in vitro (Fig. 3, C (radioautographs) and D (pad assay)). Endogenous basal levels of Cdk5 activity were shown in control (non-infected cells) and vector (EV)-infected neurons (lanes 1 and 2). Neurons infected with Cdk5-p25 showed remarkably high activity (lane 3); when co-infected with p5, however, activity decreased more than 90% (p < 0.01 compare lane 4 with lane 3). Activity in neurons co-infected with Cdk5-p35, although much lower than Cdk5-p25, exhibited only 10–20% inhibition when co-infected with p5 (p > 0.05; compare lane 6 with lane 5). These results suggest that p5 minimally affects Cdk5-p35 activity within infected neurons as much as it inhibits Cdk5-p25 activity. The more important question is whether p5 inhibits endogenous Cdk5-p35 activity. We show that cells infected only with p5 exhibit no reduction in activity (compare lanes 1 and 2 with lane 9). Complete inhibition, however, does occur in the presence of roscovitine (lane 10), suggesting that p5 does not inhibit endogenous Cdk5-p35 activity. Cells infected with dominant negative Cdk5, as negative controls, exhibit endogenous levels of activity (lanes 7 and 8). In summary, p5 does not inhibit Cdk5-p35 activity in neuronal cells to the same extent as Cdk5-p25.

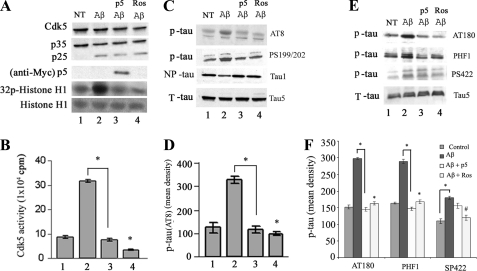

p5 Inhibits Aβ-mediated Cdk5-p25 Hyperactivity and Aβ-mediated Tau Hyperphosphorylation

It has been suggested that amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles, pathological hallmarks of several neurodegenerative disorders, are linked to deregulated Cdk5 and neuronal death. According to one model, β-amyloid, being toxic, may evoke abnormal calcium influx into neurons, which activates calpains. These proteases cleave p35 to p25, which forms a more stable and hyperactive complex with Cdk5. Hyperactivation of Cdk5 leads to the aberrant phosphorylation of Tau and neurofilaments in a number of neurodegenerative diseases, including AD and ALS (19, 21, 43–47). Several studies in different laboratories, including our own, have shown that primary cortical neurons, when treated with Aβ(1–42) are induced to form Cdk5-p25 complexes, hyperactive Cdk5 activity, hyperphosphorylation of Tau, and neuronal apoptosis (44). To determine whether p5 will inhibit endogenous Tau phosphorylation induced by Aβ treatment in cortical neurons, 7-day-old cortical neurons, infected with EV or with p5, were treated with Aβ for 6 h, lysed, and prepared for Cdk5 immunoprecipitation and kinase assay. The data are shown in Fig. 4. Aβ treatment causes an approximately 3-fold increase in endogenous Cdk5 activity as visualized by histone H1 phosphorylation (Fig. 4, A and B, fifth panel, lane 2). Infected p5, however, dramatically reduced Cdk5 activity in the Aβ-treated neurons to basal levels (lane 3). Western blot assays of whole cell lysates from similarly transfected cortical neurons treated with Aβ revealed an up-regulation of the expression of p25 (Fig. 4A, third panel, lanes 2–4). The increased p25 expression was correlated with an increased level of endogenous Tau phosphorylation at residues Ser199/Ser202 as detected by two different phospho-Tau antibodies, AT8 and Ser(P)199/Ser(P)202 (Fig. 4, C and D, panels 1 and 2, lane 2), whereas infection of p5 inhibited the Aβ-mediated Tau hyperphosphorylation, restoring it to basal levels (lane 3). In order to confirm that Tau was hyperphosphorylated by Cdk5 and not by other kinases, we used a Cdk5 inhibitor, roscovitine, to co-treat cells with Aβ. The results showed that the Tau phosphorylation was significantly inhibited (p < 0.01) (Fig. 4, C and D, first and second panels, lane 4). To confirm these results, Tau1 antibody was used to detect the non-phosphorylated Tau Ser199/Ser202 (Fig. 3C, third panel). The results showed that the non-phospho-Tau was decreased in Aβ-treated cells (compare lane 2 with lanes 3 and 4). We also used Tau antibody Ser(P)404, PHF antibody AT180 (which recognizes Thr(P)231), and Ser(P)422 antibody to observe whether p5 affects other Tau phosphorylation residues (Fig. 4, E and F). The results showed that Aβ-induced Tau hyperphosphorylation can be detected with the above three antibodies in cortical neurons. p5 significantly inhibits Tau phosphorylation at Ser404 and Thr231 (Fig. 4, E and F, panels 1 and 2, compare lane 3 with lane 2) (p < 0.01), whereas the slight decrease of Tau phosphorylation at the Ser422 site is not significant (Fig. 4E, panel 3, compare lane 3 with lane 2) (p > 0.05). However, roscovitine significantly inhibits Tau phosphorylation at the Ser422 site (panel 3, compare lane 4 with lane 2) (p < 0.05). Tau5 recognizes total Tau, non-phosphorylated as well as phosphorylated. In summary, p5 effectively inhibits Cdk5 phosphorylation of Tau sites identified in PHF Tau that characterizes abnormal tangles in AD.

FIGURE 4.

Aβ-mediated Cdk5-deregulated phosphorylation of Tau is inhibited by p5 in cortical neurons. 7 DIC cortical neurons from E-18 rat brain were infected with p5 (Myc-p5) and treated with 10 μm Aβ(1–42) for 6 h, lysed, and prepared for Cdk5 immunoprecipitation, Western blot analysis, and kinase assays. A, Western blots show the formation of p25 from p35 as a result of the stress induced by Aβ (lanes 2–4), accompanied by a significant increase in histone phosphorylation (compare lane 2 with lane 1). In the presence of p5, however, the activity is decreased by 70% to control levels, although p25 is still present (compare lane 3 with lane 2). Neurons treated with 20 μm roscovitine show almost complete inhibition (lane 4). B, the scintillation count results of three separate pad assay experiments of the above lysates are plotted in the bar graph as means ± S.E. (error bars). C, Western blots of these same Aβ-treated cells infected with and without p5 exhibit Aβ-induced Tau phosphorylation at PHF Tau sites, Ser202, Thr205, and Ser199, as detected by AT8 antibody (compare lanes 1 and 2). Cells infected with p5, however, show base-line levels of Tau phosphorylation comparable with that produced by roscovitine (lanes 3 and 4), indicating p5 rescue from Aβ-induced Tau hyperphosphorylation. Another Tau antibody specific for sites Ser199/Ser202 is also shown, confirming the above result. Tau1 recognizes nonphosphorylated Tau, whereas Tau5 identifies total Tau, phosphorylated as well as non-phosphorylated. D, a histogram of optical density data of phosphorylation by AT8 was prepared from three separate experiments. E, to show that several other phosphorylated Tau sites were rescued by p5, Western blots of similarly treated lysates were immunoreacted with PHF antibodies AT180 (Thr(P)231), Ser(P)404, and Ser(P)422. Comparison of lanes 1 and 2 shows significantly elevated Aβ-induced phosphorylation at sites Thr231 and Ser404, with lower levels at Ser422. The addition of p5 reduces phosphorylation at Thr231 and Ser404 with only a modest effect on Ser422 (compare lanes 2 and 3). F, data from three separate experiments are quantified in the bar graph. *, p < 0.01; #, p < 0.05.

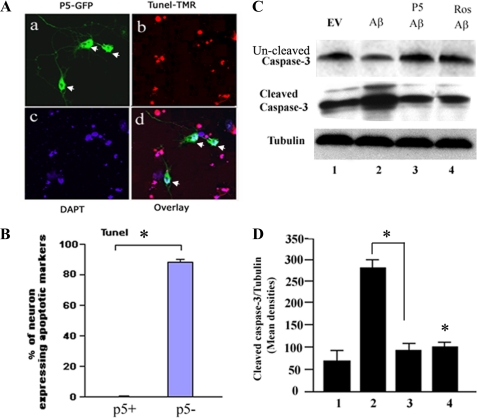

p5 Inhibits Aβ-mediated Neuronal Apoptosis

Several hypotheses for the induction of neuronal apoptosis in neurodegeneration have been offered, among which is one invoking stress-induced initiation of abnormal mitosis in neurons (48–51). Most neurons are terminally postmitotic, destined not to divide. Stress, however, may induce aberrant cell cycle activity that leads to cell death. Alternatively, Cdk5-p25 has previously been implicated in neuronal apoptosis (19, 44), with the suggestion that this aberrant Cdk5 hyperactivity, induced by a conversion of p35 to p25, is a major factor in neurodegeneration and neuronal death (19, 44). It has been shown that Aβ significantly increases the level of cortical neuron apoptosis (22, 52). To determine whether p5 can inhibit neuronal apoptosis induced by Aβ, primary cortical neurons (5 DIC) were transfected with p5-GFP using Lipofectamine 2000. After 24 h, cells were exposed to Aβ for 6 h. The neurons were fixed and subjected to TUNEL staining, whereas p5 was visualized by GFP. p5 clearly inhibited Aβ-mediated neuronal apoptosis in that the only TUNEL negative neurons were those infected with p5 (Fig. 5A, a and d, arrows), whereas non-transfected neurons showed TUNEL-positive and fragmented nuclei (Fig. 5A, a–d). The data are quantified in Fig. 5B. More than 85% of non-transfected neurons were apoptosis-positive.

FIGURE 5.

Aβ-induced apoptosis is prevented in the presence of p5. A, E-18 cortical neurons grown for 3 days were transfected with or without GFP-p5. After 24 h, they were treated with Aβ for 6 h, fixed, and prepared for a TUNEL apoptosis assay. It can be seen in the fluorescence images that p5-transfected neurons expressing GFP (a) are prevented from undergoing apoptosis as seen in the overlay in d. B, The data are quantified in the bar graph showing that virtually all p5-transfected cells were protected from Aβ-induced apoptosis. The percentage of GFP- and TUNEL-expressing neurons was determined by counting at least 100 DAPI-stained nuclei in each of five fields. Data from three experiments are shown. C, the cortical neurons infected with or without p5 were treated with Aβ for 6 h, lysed, and prepared for Western blots using caspase-3 and cleaved caspase-3 antibody expression as a measure of apoptosis. Cells infected with p5 show a marked reduction in cleaved caspase-3 expression compared with Aβ-treated cells without p5 (compare lanes 2 and 3) (panel 2) to a level comparable with the effect of roscovitine (lane 4). The uncleaved caspase-3 is lower in Aβ-induced cells (panel 1, lane 2) while higher in cells treated with p5 or roscovitine. D, the data from three experiments are expressed in a bar graph as means ± S.E. (error bars). *, p < 0.01.

To confirm these results, an independent method of assaying for cell death, the expression of cleaved caspase-3, was used. Cortical neurons infected with or without p5 and treated with Aβ for 6 h were assayed for cleaved caspase-3 by Western blot analysis (Fig. 5C). As seen in Fig. 5, the infection of EV and treatment with Aβ caused elevated expression of cleaved caspase-3 (Fig. 5C, panel 2, lane 2), which was inhibited in those cells infected with p5 (Fig. 5C, panel 2, lane 3); cleaved caspase-3 expression was reduced to control EV levels. To confirm that the effect was mediated by activated Cdk5, cells treated with roscovitine exhibited reduced levels of cleaved caspase-3 comparable with that seen with p5 infection (Fig. 5C, panel 2, lane 4). To confirm the result, anti-caspase-3 was used to detect uncleaved caspase-3. The uncleaved caspase-3 is lower in Aβ-induced cells (Fig. 5C, panel 1, lane 2) compared with control cells and the cells treated with p5 or roscovitine (Fig. 5C, panel 2, lanes 1, 3, and 4).

The data are quantified in Fig. 5D. We see that in an independent apoptosis assay, the caspase-3 cleavage assay, pretreatment with p5 significantly rescues cortical neurons from apoptosis (p < 0.01).

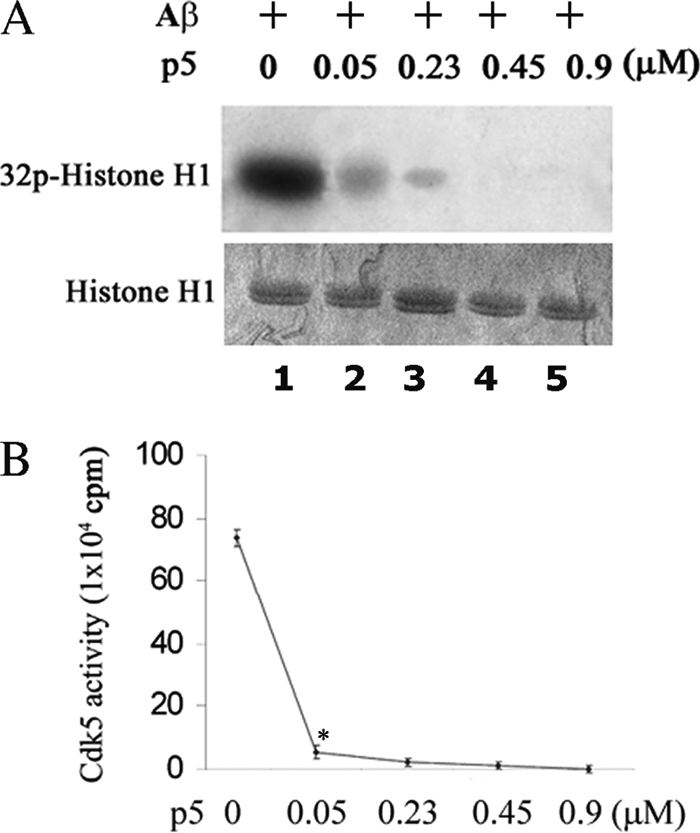

p5 at Low Doses Inhibits Cdk5 Hyperactivity Induced by Aβ

If p5 peptide is to be used therapeutically, its effectiveness at low doses in cortical neurons should be evaluated. To determine the minimum dose at which the p5 peptide is an efficient inhibitor of Cdk5-p25 hyperactivity under physiological conditions, we treated cortical neurons with Aβ(1–42) to induce the expression of p25 and Cdk5 hyperactivation (23), prepared Cdk5 immunoprecipitates, and in kinase assays followed inhibition after the addition of different concentrations of p5 (Fig. 6). The results show that 0.05 μm p5 peptide decreased Aβ(1–42)-induced Cdk5 hyperactivity more than 70% (compare lane 2 with lane 1) (p < 0.01), and at p5 concentrations of 0.45 μm or above, activity was totally eliminated (lanes 4 and 5). These results indicate that p5 is effective at very low doses in successfully reducing Aβ-induced Cdk5-p25 activity.

FIGURE 6.

p5 at low concentrations inhibits Cdk5-p25 activity induced by Aβ in cortical neurons. A, 7 DIC cortical neurons were treated with 10 μm Aβ(1–42) or PBS for 6 h, and the harvested cells were lysed for Cdk5 immunoprecipitation using anti-Cdk5 antibody. Immunoprecipitates were then used as an enzyme in in vitro kinase assays with increasing concentrations of p5 peptide. The top panel is the autoradiograph, and the bottom panel shows the corresponding Coomassie-stained histone H1 bands. High levels of induced activity are rapidly inhibited by the addition of p5. B, a line graph shows that Cdk5-p25 activities induced by Aβ were inhibited by p5 in a dose-dependent manner with most of the inhibition (90%) exhibited at 0.05 μm, the lowest concentration. Data represent means ± S.E. from three experiments. *, p < 0.01.

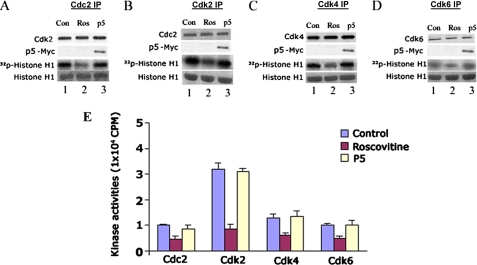

p5 Infection Does Not Inhibit Endogenous Cdk Activities in HEK293 Cells

If p5 is to function as an effective systemic therapeutic agent, it should target brain neurons without secondarily affecting organs and tissues enriched in cycling cells (i.e. immune system, gastrointestinal tract, and skin) containing cyclin-dependent kinases, such as Cdk2, Cdk4, and Cdk6. All, like Cdk5, are inhibited by roscovitine and may be sensitive to p5. To determine whether p5 inhibits other Cdks, three groups of HEK293 cells were prepared: a control group infected with vector only, a group treated with 20 μm roscovitine, and a third group of cells infected with a c-Myc-tagged p5. Aliquots of cell lysates from each group were subjected to immunoprecipitation, respectively, using Cdc2, Cdk2, Cdk4, and Cdk6 antibodies. The respective immunoprecipitates were assayed for kinase activity (Fig. 7). The expression of infected p5 (Myc) and endogenous cyclin kinase was detected by anti-Myc and the respective antibodies (Fig. 7, A–D, panels 1 and 2). The activity data seen in panel 3 show varying degrees of inhibition by roscovitine, whereas infected p5 exhibited no inhibition in all cases (p > 0.05, comparing all lanes 3 with lanes 1). The activity data, based on a kinase pad assay, were quantified as the mean and S.E. of three independent experiments in Fig. 7E. These results indicate that p5, a derivative of the p35 regulator, fails to inhibit cyclin-dependent kinases in proliferating cells, although each is inhibited to varying degrees by roscovitine. It would suggest that specificity of p5 inhibition of Cdk5-p25 resides in its interaction with the regulator, whereas roscovitine affects the catalytic site (ATP binding site) in the cyclin kinase family. As a therapeutic agent used systemically, these data suggest that p5 may effectively protect stressed neurons without affecting proliferating tissues and producing secondary side effects.

FIGURE 7.

p5 does not inhibit activity of cell cycle Cdks. To study the effect of p5 on cycling cells, a group of proliferating HEK293 cells were infected with p5-Myc, the second group were infected with EV as control, and the third group were infected with EV but treated with 20 μm roscovitine. Cell lysates from each group were immunoprecipitated with specific antibodies to Cdc2 (A), Cdk2 (B), Ckd4 (C), and Cdk6 (D), respectively. The immunoprecipitates were used for Western blotting and kinase assays with histone H1 as substrate. The expression of p5-Myc, the specific kinases as seen in blots (lanes 1 and 2), and the phosphorylating activities (presented as radioautographs, lane 3) are shown in A–D. The scintillation count data (means ± S.E. (error bars)) from three pad assay experiments in each case are quantified in the bar graphs (E). It is clear in each case that roscovitine inhibits ∼50% of endogenous Cdk activity (compare bars 2 with bars 1), whereas p5 has virtually no effect, as evident from the bar graph, (comparing bars 3 with bars 1).

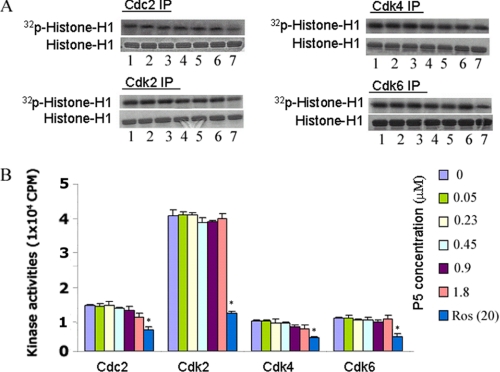

p5 Does Not Inhibit Other Cdk Activities at High Concentrations; a Dose-dependent Study

It is possible that the response to p5 is dose-dependent among cyclin-dependent kinases, with Cdk5 showing maximum sensitivity because p5 derived from p25 is more likely to competitively inhibit p25 binding to Cdk5 at lower doses. To test the possibility that higher doses of p5 might inhibit other cyclin-dependent kinases, four sets of HEK293 cells were immunoprecipitated with antibodies specific to Cdc2, Cdk2, Cdk4, and Cdk6, respectively. The immunoprecipitates were then used as enzyme in kinase pad assays in vitro to which different concentrations of p5 peptide were added, ranging from 0 to 1.8 μm (a dose-dependent study) (Fig. 8, A and B), similar to p5 concentrations used for Cdk5 (see Figs. 2 and 6B). The results, shown in autoradiographs in Fig. 8A, suggest minimal inhibition of Cdc2 and Cdk4 activities at the highest concentration (1.8 μm). Roscovitine, in lane 7, shows a significant effect for all kinases (p < 0.01). The pad assay data are quantified in Fig. 8B and confirm the conclusion that the cell cycle kinases show a marked roscovitine inhibition with virtually no inhibition by p5, even at its highest concentration (p > 0.05). Cdk5 activity, on the other hand, is virtually abolished at the lowest concentration, 0.05 μm p5 (Fig. 6B). We see that Cdk5-p25 is selectively inhibited by p5, whereas related cyclin-dependent kinases are unaffected even in actively cycling cells. It suggests that if p5 has any therapeutic value, it does show a high degree of specificity, affecting postmitotic brain neurons without affecting actively proliferating cells.

FIGURE 8.

High concentrations of p5 do not inhibit activities of cell cycle Cdks. A dose-dependent analysis shows the effect of p5 on Cdk activities in vitro. Non-treated and non-transfected HEK293 cell lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation using anti-Cdc2, anti-Cdk2, anti-Cdk4, and anti-Cdk6 antibodies. The immunoprecipitates were used for standard kinase pad assays in the presence of increasing concentrations of p5 peptide (0.05–1.8 μm). A, the phosphorylating activities at different concentrations of p5 (lanes 1–6) and 20 μm roscovitine (positive control, lane 7) for each Cdk are shown in radioautographs. Except for roscovitine, activities in the presence of p5 are relatively unaffected. B, a bar graph summarizes scintillation counting data from three experiments (means ± S.E.) of histone H1 phosphorylation. Note that only roscovitine has a significant effect on Cdk endogenous activities (∼50%; compare lane 7 with lane 1), whereas p5, even at the highest concentration of 1.8 μm, exhibits virtually no inhibition. *, p < 0.01.

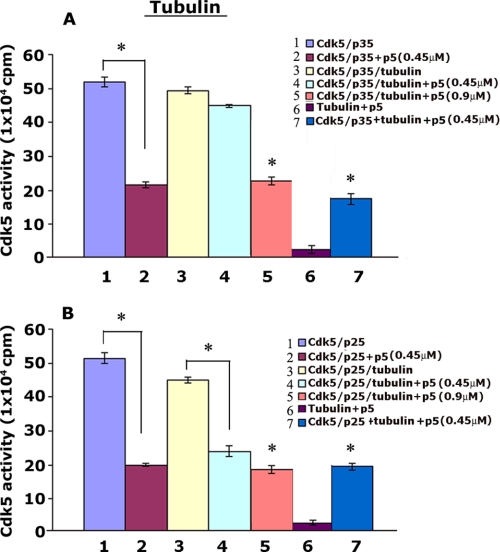

Interaction of p35 with Tubulin May Account for p5 Specificity in Cortical Neurons

The data presented in Fig. 2 show that p5 inhibition is nonspecific in vitro; it inhibits both Cdk5-p35 and Cdk5-p25 activities equally. Specificity is shown in cells, however, where p5 inhibited Cdk5-p25 activity more than Cdk5-p35 activity in cortical neurons (Fig. 3, C and D, lanes 3–6). How can we account for the difference between p5 action in vitro and in cortical neurons? A fundamental structural difference between the two activators offers a possible explanation; p25, a truncated version of p35, lacks the myristoylated p10 N-terminal domain of the intact p35. The p10 region is responsible for interaction of p35 with several cellular proteins, such as importins, Munc18, calmodulin, microtubules, and protein kinase CK2 (31, 53–55). Microtubules, for example, bind p35 due to its p10 domain, whereas they do not interact with the p25 due to the loss of the p10 region of the p35 truncated fragment (31). This suggests that p10 in p35 is essential for microtubule interaction. We propose that microtubule binding to p35 competes with p5, preventing it from interacting with Cdk5 in the Cdk5-p35 complex. We hypothesize that in the cells, proteins like microtubules, binding to p35, may prevent p5 binding to Cdk5 in the Cdk5-p35 complex. To further explore this possibility, we used β-tubulin (which is enriched in neurons) to perform an experiment in vitro to mimic p35 interactions in cells. Cdk5-p35 and Cdk5-p25 active kinases were preincubated with β-tubulin (Cdk5 kinase/tubulin ratio of 1:100), respectively, at 35 °C for 45 min to 1 h under conditions that would promote tubulin polymerization, followed by a Cdk5 kinase assay with or without the addition of p5. Our results showed that Cdk5-p35 activity was not inhibited by 0.45 μm p5 after preincubation with β-tubulin (Fig. 9A, compare lane 4 with lane 1) (p > 0.05). Cdk5-p25 activity, however, was inhibited 60% after preincubation at the lower p5 concentration (0.45 μm) (Fig. 9B, compare lane 4 with lane 1) (p < 0.01). This suggests that Cdk5-p35 activity is protected from p5 by tubulin polymerization perhaps as a consequence of microtubule binding the Cdk5-p35 complex, making it less accessible to p5. At double the concentration of p5 to 0.90 μm, however, both Cdk5 complexes were inhibited (Fig. 9, A and B, compare lanes 5 with lanes 1) (p < 0.01). To confirm the importance of tubulin polymerization, we could show that in the absence of preincubation (unpolymerized), p5 inhibited both Cdk5-p35 and Cdk5-p25 activities equally at 0.45 μm (Fig. 9, A and B, compare lanes 7 with lanes 1) (p < 0.01). We used albumin as a control protein in the same experimental conditions and showed no differential effect of p5 on both Cdk5-p35 and Cdk5-p25 activities (data not shown). These results suggest that specificity of p5 inhibition in cortical neurons probably results from p35 binding to proteins like microtubules to form a multimeric complex that sequesters the Cdk5-p35 complex from p5. On the other hand, p25, lacking the p10 domain, fails to bind these proteins, and p5 readily binds with Cdk5 in the Cdk5-p25 complex to inhibit activity.

FIGURE 9.

Polymerized tubulin protects Cdk5-p35 activity from p5 inhibition in vitro. Active Cdk5-p35 and Cdk5-p25 were preincubated with tubulin in PEM buffer supplemented with 1 mm GTP at 35 °C for 45 min to 1 h (under conditions to promote polymerization). p5 at 0.45 or 0.9 μm was added, and the mixture was then subjected to in vitro kinase assay. Quantification of Cdk5-p35 (A) and Cdk5-p25 (B) activities showed that p5 inhibits preincubated Cdk5-p25 activity ∼50% (B, compare 3 and 4) but has no effect on preincubated Cdk5-p35 activity (A, compare 3 and 4). At a higher concentration of p5 (0.9 μm), both kinase complexes are inhibited equally (compare 5 in A and B). The importance of polymerization during preincubation is seen in lane 7 of both A and B; in the presence of unpolymerized tubulin, p5 inhibits both kinases equally. The concentrations of Cdk5-p35 and Cdk5-p25 were matched to exhibit equal activity. Data represent mean ± S.E. of three experiments. *, p < 0.01.

DISCUSSION

Neurodegenerative disorders leading to dementia, such as Alzheimer disease, are chronic, long term processes resulting from an accumulation of various lesions and insults. Among the latter are oxidative stress (56), inflammation, hormonal deficits, abnormal cholesterol metabolism (57, 58), and exocitotoxic stress (59). Such defects result in synaptic function deficits, neuronal death, and dementia. The hallmark pathologies of AD brains are the β-amyloid-rich senile plaques and the neurofibrillary tangles containing hyperphosphorylated Tau among other constituents (neurofilaments, kinases, etc). These pathologies have generally been regarded as the primary cause of cell death and dementia, and the factors responsible for their formation have been extensively studied. β-Amyloid is toxic in a variety of neuronal preparations (60) and is known to induce hyperphosphorylated Tau accumulations and cytoskeletal defects in cortical neurons in vitro (23, 27) and in β-amyloid-expressing transgenic mice (61). Accumulation of hyperphosphorylated Tau in neurofibrillary tangles is correlated with the activation of kinases, such as GSK3 (62) and Cdk5 (16, 21, 44, 45), as well as the down-regulation of phosphatases, such as PP2A (63). Our laboratory, along with others (64–66), has focused on Cdk5 and its deregulation as a principal “player” responsible for Tau pathology, neurofibrillary tangle accumulation, and cell death in AD. Several lines of evidence are consistent with this hypothesis. Cdk5 is stabilized and hyperactivated when complexed with p25, a truncated fragment of the normal p35 regulator (44). Neuronal stress converts p35 to its truncated form p25 by activating calpain, a calcium-dependent protease (19, 43), resulting in long term accumulation of p25, a major factor in the formation of hyperactivated Cdk5. Consistent with this hypothesis, the ratio of p25 to p35 has been reported to be significantly higher in AD brains than in control brains, particularly in the frontal cortex (44, 45), although other laboratories report either a decrease in p25 or no evidence of an increased p25-p35 ratio in AD brains (46, 67). Nevertheless, overexpression of p25 in cultured neurons leads to cytoskeletal disruption, hyperphosphorylated Tau, and apoptotic cell death (16). Cdk5 activity is deregulated in hippocampal neurons by Aβ fibrils, resulting in the activation of Cdk5 and hyperphosphorylation of Tau (68, 69). Probably because of its multifunctional role in the nervous system, aberrant Cdk5-p25 activity looms as a major factor in neurodegenerative disorders. This suggests that inhibitors of Cdk5 activity may be effective candidates for therapeutic development (25, 70, 71).

Although several potent chemical inhibitors of Cdk5 have been identified and studied (26, 72, 73), most compete with ATP at the catalytic binding site. Accordingly, these compounds are relatively nonspecific because other cyclin-dependent kinases (as well as other kinases) are equally dependent on ATP binding. Acknowledging this problem, a group, in search of non-competitive ATP inhibitors, are screening an extensive library of compounds that affect the kinetics of Cdk5-p25 interactions with Tau to distinguish competitive from non-competitive inhibitors of Cdk5 activity (63, 70). The ultimate challenge for such compounds is to selectively inhibit Cdk5-p25 in biological systems without affecting the activity of Cdk5-p35, the active complex essential for neural development and function.

As an approach to this problem, in our previous studies, we have demonstrated that CIP, a 125-amino acid truncated peptide derived from p35, specifically inhibited Cdk5-p25 activity and significantly decreased hyperphosphorylation of Tau and apoptosis induced by Aβ treatment in both HEK293 cells and cortical neurons (23, 27). An effective therapeutic drug, however, should be much smaller to increase absorption efficiency (particularly across the blood-brain barrier) after injection or oral administration. Here we tested several truncated peptides derived from CIP and identified p5 (only 24 residues) as a more effective inhibitor of Cdk5-p25 activity than CIP in vitro. Furthermore, we confirmed that p5 rescued cortical neurons from Aβ toxicity, Tau pathology, and cell death. At low doses, it specifically inhibited Cdk5-p25 activity without affecting endogenous Cdk5-p35 activity in cortical neurons. At higher doses, the activities of closely related Cdk kinases, such as Cdc2, Cdk2, Cdk4, and Cdk6, in proliferating HEK293 cells were unaffected by p5.

Although both complexes are inhibited equally by p5 in vitro, it is noteworthy that the specificity of inhibition is displayed within cells; in cortical neurons, hyperactive Cdk5-p25 is more effectively inhibited by p5 than the normal endogenous Cdk5-p35 complex. Although the factors responsible for p5 specificity in cortical neurons are not understood, it is critical to the therapeutic potential of p5. We propose that the p10 myristoylated N-terminal domain of p35, absent in p25, determines the specificity of p5 inhibition in cortical neurons.

The p10 interaction in vivo with other cellular proteins, such as tubulin (microtubules) and calmodulin (31, 74), may protect the activity of the Cdk5-p35 complex (and not the Cdk5-p25 complex) from p5 inhibition. In our experiments (Fig. 9), we showed that after preincubation of the Cdk5-p35 complex with tubulin, under conditions favoring polymerization, the addition of 0.45 μm p5 had no effect on activity, whereas Cdk5-p25 was inhibited under identical conditions. Without preincubation, however, p5 inhibited both complexes equally; p35 interaction with soluble tubulin did not prevent p5 inhibition. These data suggest that in cortical neurons, the relatively high affinity of p35 to microtubules sequesters the Cdk5-p35 complex from p5, interfering with p5 binding to Cdk5. The significant finding is that in cortical neurons, p5 inhibits the hyperactive Cdk5-p25 complex responsible for neuronal pathology without affecting the activity of the endogenous, functionally dependent Cdk5-p35.

We have identified and characterized p5 as a small, more readily diffusible peptide that specifically inhibits Cdk5-p25 activity at low doses, does not affect endogenous Cdk5-p35 essential for neuronal development and function, does not inhibit related Cdks in proliferating cells (and hence would have significantly reduced side effects), and rescues neurons from Aβ toxicity, Tau hyperphosphorylation, and cell death. Accordingly, we believe that p5 is an excellent therapeutic candidate to rescue neurons from the debilitating onslaught of Aβ toxicity and hyperactivated Cdk5-p25 that characterizes some neurodegenerative disorders.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health, NINDS, intramural funds.

- AD

- Alzheimer disease

- EV

- empty vector

- DIC

- days in culture

- Aβ

- β-amyloid.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chae T., Kwon Y. T., Bronson R., Dikkes P., Li E., Tsai L. H. (1997) Neuron 18, 29–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cheung Z. H., Fu A. K., Ip N. Y. (2006) Neuron 50, 13–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dhavan R., Tsai L. H. (2001) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2, 749–759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gilmore E. C., Ohshima T., Goffinet A. M., Kulkarni A. B., Herrup K. (1998) J. Neurosci. 18, 6370–6377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lai K. O., Ip N. Y. (2009) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1792, 741–745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nikolic M., Dudek H., Kwon Y. T., Ramos Y. F., Tsai L. H. (1996) Genes Dev. 10, 816–825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ohshima T., Gilmore E. C., Longenecker G., Jacobowitz D. M., Brady R. O., Herrup K., Kulkarni A. B. (1999) J. Neurosci. 19, 6017–6026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ohshima T., Ward J. M., Huh C. G., Longenecker G., Veeranna Pant H. C., Brady R. O., Martin L. J., Kulkarni A. B. (1996) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 93, 11173–11178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zheng Y. L., Li B. S., Kanungo J., Kesavapany S., Amin N., Grant P., Pant H. C. (2007) Mol. Biol. Cell 18, 404–413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hisanaga S., Saito T. (2003) Neurosignals 12, 221–229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tang D., Wang J. H. (1996) Prog. Cell Cycle Res. 2, 205–216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Angelo M., Plattner F., Giese K. P. (2006) J. Neurochem. 99, 353–370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fischer A., Sananbenesi F., Pang P. T., Lu B., Tsai L. H. (2005) Neuron 48, 825–838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fischer A., Sananbenesi F., Schrick C., Spiess J., Radulovic J. (2002) J. Neurosci. 22, 3700–3707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fischer A., Sananbenesi F., Spiess J., Radulovic J. (2003) Curr. Drug Targets CNS Neurol. Disord. 2, 375–381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ahlijanian M. K., Barrezueta N. X., Williams R. D., Jakowski A., Kowsz K. P., McCarthy S., Coskran T., Carlo A., Seymour P. A., Burkhardt J. E., Nelson R. B., McNeish J. D. (2000) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 2910–2915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cruz J. C., Tseng H. C., Goldman J. A., Shih H., Tsai L. H. (2003) Neuron 40, 471–483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kusakawa G., Saito T., Onuki R., Ishiguro K., Kishimoto T., Hisanaga S. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 17166–17172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee M. S., Kwon Y. T., Li M., Peng J., Friedlander R. M., Tsai L. H. (2000) Nature 405, 360–364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nguyen M. D., Mushynski W. E., Julien J. P. (2002) Cell Death Differ. 9, 1294–1306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Noble W., Olm V., Takata K., Casey E., Mary O., Meyerson J., Gaynor K., LaFrancois J., Wang L., Kondo T., Davies P., Burns M., Veeranna Nixon R., Dickson D., Matsuoka Y., Ahlijanian M., Lau L. F., Duff K. (2003) Neuron 38, 555–565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Town T., Zolton J., Shaffner R., Schnell B., Crescentini R., Wu Y., Zeng J., DelleDonne A., Obregon D., Tan J., Mullan M. (2002) J. Neurosci. Res. 69, 362–372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zheng Y. L., Kesavapany S., Gravell M., Hamilton R. S., Schubert M., Amin N., Albers W., Grant P., Pant H. C. (2005) EMBO J. 24, 209–220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Helal C. J., Kang Z., Lucas J. C., Gant T., Ahlijanian M. K., Schachter J. B., Richter K. E., Cook J. M., Menniti F. S., Kelly K., Mente S., Pandit J., Hosea N. (2009) Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 19, 5703–5707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lau L. F., Seymour P. A., Sanner M. A., Schachter J. B. (2002) J. Mol. Neurosci. 19, 267–273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shiradkar M. R., Padhalingappa M. B., Bhetalabhotala S., Akula K. C., Tupe D. A., Pinninti R. R., Thummanagoti S. (2007) Bioorg. Med. Chem. 15, 6397–6406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zheng Y. L., Li B. S., Amin N. D., Albers W., Pant H. C. (2002) Eur. J. Biochem. 269, 4427–4434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.He T. C., Zhou S., da Costa L. T., Yu J., Kinzler K. W., Vogelstein B. (1998) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 2509–2514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zheng Y. L., Li B. S., Veeranna Pant H. C. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 24026–24032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Veeranna Amin N. D., Ahn N. G., Jaffe H., Winters C. A., Grant P., Pant H. C. (1998) J. Neurosci. 18, 4008–4021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hou Z., Li Q., He L., Lim H. Y., Fu X., Cheung N. S., Qi D. X., Qi R. Z. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 18666–18670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Amin N. D., Zheng Y. L., Kesavapany S., Kanungo J., Guszczynski T., Sihag R. K., Rudrabhatla P., Albers W., Grant P., Pant H. C. (2008) J. Neurosci. 28, 3631–3643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Han P., Dou F., Li F., Zhang X., Zhang Y. W., Zheng H., Lipton S. A., Xu H., Liao F. F. (2005) J. Neurosci. 25, 11542–11552 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kanungo J., Zheng Y. L., Amin N. D., Kaur S., Ramchandran R., Pant H. C. (2009) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 386, 263–267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kanungo J., Zheng Y. L., Amin N. D., Pant H. C. (2009) Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 29, 1073–1080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kanungo J., Zheng Y. L., Mishra B., Pant H. C. (2009) Neurochem. Res. 34, 1129–1137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kesavapany S., Li B. S., Amin N., Zheng Y. L., Grant P., Pant H. C. (2004) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1697, 143–153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kesavapany S., Pareek T. K., Zheng Y. L., Amin N., Gutkind J. S., Ma W., Kulkarni A. B., Grant P., Pant H. C. (2006) Neurosignals 15, 157–173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kesavapany S., Zheng Y. L., Amin N., Pant H. C. (2007) Biotechnol. J. 2, 978–987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rudrabhatla P., Zheng Y. L., Amin N. D., Kesavapany S., Albers W., Pant H. C. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 26737–26747 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shea T. B., Zheng Y. L., Ortiz D., Pant H. C. (2004) J. Neurosci. Res. 76, 795–800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zheng M., Leung C. L., Liem R. K. (1998) J. Neurobiol. 35, 141–159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nath R., Davis M., Probert A. W., Kupina N. C., Ren X., Schielke G. P., Wang K. K. (2000) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 274, 16–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Patrick G. N., Zukerberg L., Nikolic M., de la Monte S., Dikkes P., Tsai L. H. (1999) Nature 402, 615–622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tseng H. C., Zhou Y., Shen Y., Tsai L. H. (2002) FEBS Lett. 523, 58–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Patrick G. N., Zukerberg L., Nikolic M., de La Monte S., Dikkes P., Tsai L. H. (2001) Nature 411, 764–765 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nguyen M. D., Larivière R. C., Julien J. P. (2001) Neuron 30, 135–147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Herrup K., Neve R., Ackerman S. L., Copani A. (2004) J. Neurosci. 24, 9232–9239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Herrup K., Yang Y. (2007) Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 8, 368–378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Webber K. M., Raina A. K., Marlatt M. W., Zhu X., Prat M. I., Morelli L., Casadesus G., Perry G., Smith M. A. (2005) Mech. Ageing Dev. 126, 1019–1025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhu Y. S., Saito T., Asada A., Maekawa S., Hisanaga S. (2005) J. Neurochem. 94, 1535–1545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Oddo S., Caccamo A., Shepherd J. D., Murphy M. P., Golde T. E., Kayed R., Metherate R., Mattson M. P., Akbari Y., LaFerla F. M. (2003) Neuron 39, 409–421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fu X., Choi Y. K., Qu D., Yu Y., Cheung N. S., Qi R. Z. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 39014–39021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lim A. C., Qu D., Qi R. Z. (2003) Neurosignals 12, 230–238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Qu D., Li Q., Lim H. Y., Cheung N. S., Li R., Wang J. H., Qi R. Z. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 7324–7332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Smith D. S., Tsai L. H. (2002) Trends Cell Biol. 12, 28–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Luque F. A., Jaffe S. L. (2009) Int. Rev. Neurobiol. 84, 151–165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Martins I. J., Berger T., Sharman M. J., Verdile G., Fuller S. J., Martins R. N. (2009) J. Neurochem. 111, 1275–1308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dong X. X., Wang Y., Qin Z. H. (2009) Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 30, 379–387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yankner B. A., Duffy L. K., Kirschner D. A. (1990) Science 250, 279–282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Smith W. W., Gorospe M., Kusiak J. W. (2006) CNS Neurol. Disord. Drug Targets 5, 355–361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Liu F., Liang Z., Shi J., Yin D., El-Akkad E., Grundke-Iqbal I., Iqbal K., Gong C. X. (2006) FEBS Lett. 580, 6269–6274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Liu M., Choi S., Cuny G. D., Ding K., Dobson B. C., Glicksman M. A., Auerbach K., Stein R. L. (2008) Biochemistry 47, 8367–8377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cruz J. C., Kim D., Moy L. Y., Dobbin M. M., Sun X., Bronson R. T., Tsai L. H. (2006) J. Neurosci. 26, 10536–10541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Maccioni R. B., Otth C., Concha I. I., Muñoz J. P. (2001) Eur. J. Biochem. 268, 1518–1527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rockenstein E., Torrance M., Mante M., Adame A., Paulino A., Rose J. B., Crews L., Moessler H., Masliah E. (2006) J. Neurosci. Res. 83, 1252–1261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Taniguchi S., Fujita Y., Hayashi S., Kakita A., Takahashi H., Murayama S., Saido T. C., Hisanaga S., Iwatsubo T., Hasegawa M. (2001) FEBS Lett. 489, 46–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Alvarez A., Muñoz J. P., Maccioni R. B. (2001) Exp. Cell Res. 264, 266–274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Alvarez A., Toro R., Cáceres A., Maccioni R. B. (1999) FEBS Lett. 459, 421–426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Glicksman M. A., Cuny G. D., Liu M., Dobson B., Auerbach K., Stein R. L., Kosik K. S. (2007) Curr. Alzheimer Res. 4, 547–549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Tsai L. H., Lee M. S., Cruz J. (2004) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1697, 137–142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Knockaert M., Wieking K., Schmitt S., Leost M., Grant K. M., Mottram J. C., Kunick C., Meijer L. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 25493–25501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Helal C. J., Kang Z., Lucas J. C., Bohall B. R. (2004) Org. Lett. 6, 1853–1856 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.He L., Hou Z., Qi R. Z. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 13252–13260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]