Abstract

We report here the construction of a physical and genetic map of the virulent Wolbachia strain, wMelPop. This map was determined by ordering 28 chromosome fragments that resulted from digestion with the restriction endonucleases FseI, ApaI, SmaI, and AscI and were resolved by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. Southern hybridization was done with 53 Wolbachia-specific genes as probes in order to determine the relative positions of these restriction fragments and use them to serve as markers. Comparison of the resulting map with the whole genome sequence of the closely related benign Wolbachia strain, wMel, shows that the two genomes are largely conserved in gene organization with the exception of a single inversion in the chromosome.

Wolbachia pipientis bacteria are vertically transmitted obligate intracellular symbionts that infect a broad range of insect species, a number of noninsect arthropods such as isopods and mites, and most species of filarial nematodes (2, 10, 18, 20, 21). In nematodes it appears that Wolbachia organisms are required for fertility and normal development of the host (11, 18). In contrast, in arthropods they are best known for the various reproductive modifications they induce that include cytoplasmic incompatibility (6a),parthenogenesis (1, 16, 19), feminization (6, 15), and male killing (5, 6, 8, 9). Usually Wolbachia organisms are benign in their hosts; however, one strain, wMelPop, has been implicated in the expression of a virulent life-shortening trait in Drosophila melanogaster (12-14).

Although there is an appreciable and increasing amount of knowledge about the distribution, phylogeny, and population genetics of Wolbachia infections, little is known about their genomic organization. Very few genes have been cloned from these bacteria, and these have mainly been used to address questions related to Wolbachia phylogeny. In a previous report (17), we have determined genome sizes with pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) for a number of different Wolbachia strains. They are much smaller (ranging from 0.95 to 1.5 Mb) than the genome sizes of free-living bacteria, a finding consistent with their obligate intracellular nature. In this report we focused on the construction of a physical and genetic map of the virulent Wolbachia strain, wMelPop. This strain possesses a unique phenotype, namely, early death of the adult insect host, and is very closely related to the benign wMel strain (13), which is in the process of having its full genome sequenced. Comparison of the genomes of these strains may shed light on the mechanisms of genome evolution within this group of bacteria, as well as indicate differences that may relate to the expression of the virulence phenotype by this particular strain.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Drosophila and Wolbachia strains.

D. melanogaster w1118 harboring wMelPop, D. melanogaster yw67c23 carrying wMel, and D. simulans Riverside hosting wRi were used as the source of Wolbachia in the present study. D. melanogaster w1118 previously treated with tetracycline was used as a Wolbachia-free control insect strain. All of the four Drosophila strains were reared on standard corn flour-sugar-yeast medium at 25°C.

Wolbachia purification.

Large-scale purification of wMelPop genomic DNA was prepared as previously described (17). In brief, adult flies were homogenized and filtered to remove debris, and the filtrate was differentially centrifuged to remove Drosophila nuclei while retaining Wolbachia genomic DNA. The purified wMelPop genomic DNA was then embedded in agarose blocks, treated with DNase I (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) and then proteinase K (Roche), and finally stored at 4°C in a lysis buffer until further use.

Restriction digestion of Wolbachia genomic DNA.

Plugs were treated as previously described (17) for restriction enzyme digestion with AscI (GG^CGCGCC), ApaI (GGGCC^C), FseI (GGCCGG^CC), and SmaI (CCC^GGG) (New England Biolabs, Beverly, Mass.). Complete digestions were carried out overnight at the optimal conditions for the restriction enzyme according to the manufacturer's directions. To determine the optimal conditions for partial digestions, we examined combinations of different digestion times (1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 h) and different amounts of restriction enzyme (from 0.01 to 10 U). The final reaction conditions used were 3 h digestion with 0.1 U of enzyme in a total volume (plug plus buffer) of 150 μl. The reaction was stopped with 1 ml of 0.5 M EDTA (pH 8.0). Sequential digestions were also done. After the first digestion, fragments were separated on a low-melting-point (LMP) agarose (American Bioanalytical, Natick, Mass.) PFGE gel and then recovered for a second digestion. The LMP agarose blocks containing the fragments of interest were cut out with a clean razor blade, treated at 56°C in 0.5 M EDTA (pH 8.0) for 2 h, and finally stored at 4°C until further use. The blocks were washed six times (each 30 min) in 1× Tris-EDTA at room temperature to dilute EDTA before the second digestion.

PFGE.

CHEF (contour-clamped homogeneous electric field) (4) gels were run to separate DNA fragments that included at least one fragment with a size greater than 50 kb by using either a CHEF Mapper XA (Bio-Rad) or a CHEF-DR II (Bio-Rad). For the resolution of DNA fragments of <50 kb, field inversion gel electrophoresis (3) was done by using only the CHEF Mapper XA. All of the electrophoresis was carried out at 14°C by using 0.5× Tris-borate-EDTA as the running buffer. The migration profiles were determined by using CHEF Mapper XA interactive software version 1.2 (Bio-Rad). Fragment lengths and the presence of multiple fragments were determined by using Gel-Doc and Quantity One 1-D analysis software (Bio-Rad).

LMP agarose CHEF gels were run to recover fragments of interest for partial digestions, and these gels were run for 16 h 50 min at 6 V/cm, with switch times ramped from 0.42 s to 2 min 41.18 s. Fragments of between 10 and 1,800 kb can be recovered under these conditions.

Southern hybridization.

The probes used in the present study originated from three sources: (i) previously cloned gene fragments from wTai digested from plasmids kindly provided by S. Masui, University of Tokyo (Table 1); (ii) previously described gene fragments PCR amplified from wMelPop with Wolbachia gene-specific primers (Table 2); and (iii) gene fragments (with or without flanking sequences) PCR amplified with Wolbachia gene-specific primers as determined from the wMel whole-genome sequencing project (Table 3).

TABLE 1.

Probes derived from previously cloned genes of the Wolbachia strain wTaia

| Gene | Gene product |

|---|---|

| rpoB | RNA polymerase |

| gyrA | DNA gyrase |

| sucD | Succiny1-CoA synthetaseb |

| lipA | Lipoic acid synthetase |

| thrS | Threonyl-tRNA synthetase |

| atpA | F1F0-ATPase |

| polA | DNA polymerase I |

| sdhA | Succinate dehydrogenase |

| glyA | Serine hydroxymethyltransferase |

| tuf | Elongation factor Tu |

Kindly provided by Shinji Masui.

CoA, coenzyme A.

TABLE 2.

Probes derived from previously described Wolbachia genes PCR amplified with gene-specific primers

| Gene | Gene product | Primer used for amplification (5′-3′)

|

PCR template | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Sequence | |||

| wsp | Wolbachia surface protein | 81F | TGGTCCAATAAGTGATGAAGAAAC | wMelPop |

| 691R | AAAAATTAAACGCTACTCCA | wMelPop | ||

| ftsZ | Cell division protein | ftsZ1F | GTTGTCGCAAATACCGATGC | wMelPop |

| ftsZ1R | CTTAAGTAAGCTGGTATATC | wMelPop | ||

| rrs | 16S rRNA | 99F | TTGTAGCCTGCTATGGTATAACT | wMelPop |

| 994R | GAATAGGTATGATTTTCATGT | wMelPop | ||

| dnaA | Chromosomal DNA replication initiator | dnaAp1 | GCTATAGCATGCATTAGATGTG | wRi |

| dnaAS2R | TCACGAGATTAACATGCAC | wRi | ||

| acrD | Multidrug resistance protein D | dnaAp5 | GGATTTCTGCTCAAGATAGTGA | wRi |

| dnaAS5R | TCGAATATTTACCGGTATC | wRi | ||

| nusA | N utilization substance protein A | dnaAS9F | CTATTGCTTGATGCCTTTCATC | wRi |

| dnaASAR | CTACTTGTTTAACAATACCATACC | wRi | ||

| infB | Translation initiation factor IF-2 | dnaASDF | CTCATGATGCAGAAGAAC | wRi |

| dnaASER | CATAACATCACCACCAAGC | wRi | ||

| rbfA-ubiA | Ribosomal binding factor A 4-hydroxybenzoate octaprenyltransferase | dnaApC | GTAAGTGATGGAGTCATAAG | wRi |

| dnaASIR | CCAAGATTTTGTTGTATCACC | wRi | ||

TABLE 3.

Probes derived from gene fragments PCR amplified with Wolbachia gene-specific primers

| Gene | Gene product | PCR template | Primer name | Primer (5′-3′) sequencea |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| rrl | 23S rRNA | wMelPop | 232FYW | GTAGTGACGAGCGAAAG |

| 0775R | ATTGGCCTTTCACCCC | |||

| aatA | Aspartate aminotransferase A | wMelPop | aatAF | CAACTTATGGATAGTC |

| aatAR | ACTGCTGTTGATGG | |||

| aprD | Alkaline protease secretion ATP- binding protein | wMelPop | orf649F | TGCATTTGCATGTTCTGC |

| orf649R | CCTGCAATTTTTGCTGCT | |||

| atpD | ATP synthase β subunit | wMelPop | atpDF | CACTTACCAGAGGCTG |

| atpDR | AAGGTCAATTTGGGTC | |||

| coq7 | Ubiquinone biosynthetase protein | wMelPop | coq7F | CAGCCTGTTTTTATGAATG |

| coq7R | AGGTACAGCAACAATCAG | |||

| coxA | Cytochrome c oxidase polypeptide I | wMelPop | coxAF | CAGATATGGCATTTCCTCG |

| coxAR | GCAAATAGCATAGGGGTC | |||

| cysS | Cysteinyl-tRNA synthetase | wMel | cysSF | GAGCTTCAGGAATG |

| cysSR | GATAAAGATCATGTG | |||

| dnaJ | DNAJ protein | wMelPop | dnaJF | CTTCAGATTGCTGTTG |

| dnaJR | CTATGACCGTTATGG | |||

| fabF | 3-Oxoacyl-[acyl-carrier protein] synthase II | wMelPop | fabFF | CACCAAGTAAATGTCC |

| fabFR | AGTCACTGGTGTTG | |||

| ffh | Signal recognition particle protein | wMelPop | ffhF | ACCATAGAGCTCATTTG |

| ffhR | CTTGCCTCTTTAGAC | |||

| folD | Methylenetetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase | wMel | foldF | GTGTATCTACGGTTGG |

| foldR | CAATCCAGCAAGTCAGG | |||

| ftsK | Cell division protein FtsK | wMelPop | ftsKF | GCTACAAATGAGGAAGTG |

| ftsKR | AGCAACGAGCAAGTGG | |||

| ftsW | Cell division protein FtsW | wMelPop | ftsWF | AACACTCAATGTTACCCC |

| ftsWR | TCTGGTATAGAACGCTGG | |||

| gidA | Glucose-inhibited division protein A | wMelPop | gidAF | CAGTATCATCATCCAG |

| gidAR | CACGCTGCTTATAAC | |||

| groEL | Heat shock protein 60 | wMelPop | hsp60F | TTCTAGCTTTCACACTGTC |

| hsp60R | GTATCAGGTGAGCAGTTG | |||

| htrA | Probable periplasmic serine proteinase do-like precursor | wMelPop | htrAF | TTCTCCGATCACAAC |

| htrAR | CTACTGCATGCAAC | |||

| mraY1 | Phospho-N-acetylmuramoyl-pentapeptide-transferase | wMelPop | mraY1F | TGACCATCTCTTCTTCTC |

| mraY1R | GCAGATGATCTTAGCTAC | |||

| imsbA | ABC transporter ATP-binding protein | wMelPop | msbA2F | TGGCACAGAGCACGATTT |

| msbA2R | TGAAAACGGAGCAGAAGC | |||

| mutS | DNA mismatch repair protein | wMelPop | mutSF | CACACAGTAGTGAATC |

| mutSR | TATTGTTGTGGGAGAG | |||

| mviN | Virulence factor Mvin | wMelPop | orf258F | TGCTCCTGGATTTGACCA |

| orf258R | TTGACATGACTGCCGTTG | |||

| permease | Na+-linked d-alanine glycine permease | wMelPop | nagPF | TATGGAATACAGAC |

| nagPR | TGTCTATAAGTGGTG | |||

| omp1 | Outer membrane protein Omp1 | wMelPop | omp1F | TTCCTGCCCTGCTTGTTG |

| omp1R | ACGTTGTGCATACTCTGG | |||

| pccB | Propionyl-CoA carboxylase β-chain precursorb | wMel | pccBF | ACATTCGAGTATTCTG |

| pccBR | GACATTGATGAATCCT/PICK> | |||

| pcnB | Poly(A) polymerase | wMel | pcnBF | TTTGGTGGTGAGG |

| pcnBR | GATATCGTTGGATAG | |||

| pheS | Phenylalanyl-tRNA synthetase α chain | wMelPop | pheSF | GTCATAAAAGCTCCTCAAG |

| pheSR | AGAGATAGAAGACGCAGG | |||

| ppdK | Pyruvate phosphate dikinase | wMelPop | ppdKF | CCACTAACTTTGCAATC |

| ppdKR | GAACGCTGATACTC | |||

| putA | Proline dehydrogenase | wMelPop | putAF | GAAAGCAAAGCATCC |

| putAR | ATGAACCTCATCCAG | |||

| radA | DNA repair protein | wMelPop | radAF | CATGTGACAATTGGG |

| radAR | GCAACAGCAAGATCAG | |||

| recA | DNA recombination protein RecA | wMelPop | recAF | GGTTGATGTGATAG |

| recAR | CTCACTATCCTCGTC | |||

| RP006 | Hypothetical protein RP006 from R. prowazekii | wMelPop | RP006F | AATGCGTGGTCAAGTGTTG |

| RP006R | CGCTACACTCGTGCATAA | |||

| trmD | tRNA (guanine-N1)-methyltransferase | wMelPop | trmDF | CGACATTTCTAACTACTACC |

| trmDR | CATGCATCAAGAACCACC | |||

| trxB | Thioredoxin reductase | wMelPop | trxB2F | GTTGGAATATTCACTG |

| trxB2R | GAGAGTTGTGGATTAC | |||

| uvrC | Excinuclease ABC subunit C | wMelPop | uvrCF | TTTTCTGTACTCACTC |

| uvrCR | GAGTTATGCTCTTAC | |||

| virB4 | Virulence protein VirB4 | wMelPop | virB4F | CAGAGGTATCATCAAG |

| virB4R | GTACTTACCAGTACATAG |

Primer sequences were determined from the unfinished wMel whole genome sequence.

CoA, coenzyme A.

In the latter case, PCR primers were designed based on sequence data of the wMel chromosome and used in PCRs with wMel-infected and uninfected flies. PCR products of the expected size were found in all cases for wMel-infected flies, and no products were produced from uninfected flies. In addition, the majority of primers were able to amplify PCR products of the expected size from wMelPop-infected flies. These fragments were used as probes in subsequent Southern hybridizations. In cases in which the primers could only amplify a fragment from wMel, this product was used as a probe (Table 3).

PCR amplifications were done with total DNA extracted from each of the four Drosophila strains as previously described (7). PCR products were gel purified with Qiagen gel extraction kits (Qiagen, Inc., Valencia, Calif.). Probes were made by radioactively labeling PCR fragments with a random primed DNA labeling kit (Roche). After PFGE, Southern transfers were done with a VacuGene XL vacuum blotting system (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Uppsala, Sweden). The blots were hybridized at 56°C and washed under high-stringency conditions.

Sequencing.

Two genomic DNA fragments from wMelPop were PCR amplified with primers pccBAF (5′-GTATCCATATGATGCAGC-3′) and pccBAR (5′-GACATTGATGAATCCT-3′) and with primers cysSFF (5′-TTCTATATGCCATCCAGGTC-3′) and cysSRR (5′-TCACTGCAGCTTCTATTTGG-3′) and then sequenced. The two sequences have been deposited in the GenBank database under accession numbers AF426436 and AF426437, respectively.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

In a previous study (17) it was shown that four restriction enzymes (AscI, ApaI, SmaI, and FseI) digest the wMelPop genome into a small number of fragments ranging from 6 kb to 1 Mb. These four enzymes were used for the construction of a physical map of the wMelPop genome. Digestions with one enzyme or a combination of any two, three, or all of the four enzymes were done to detect neighboring restriction sites.

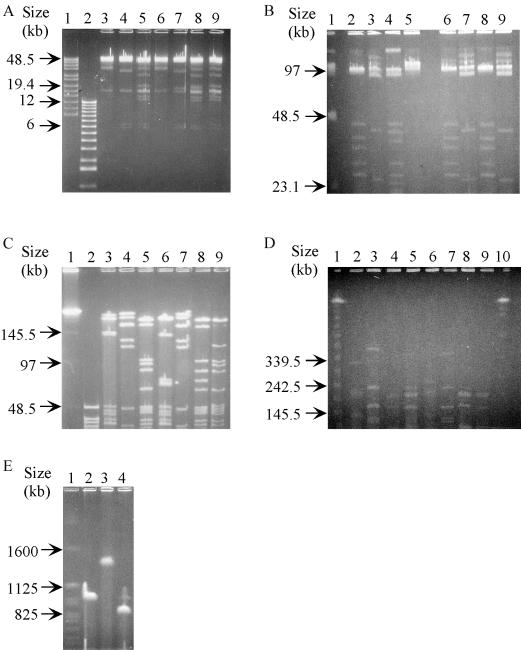

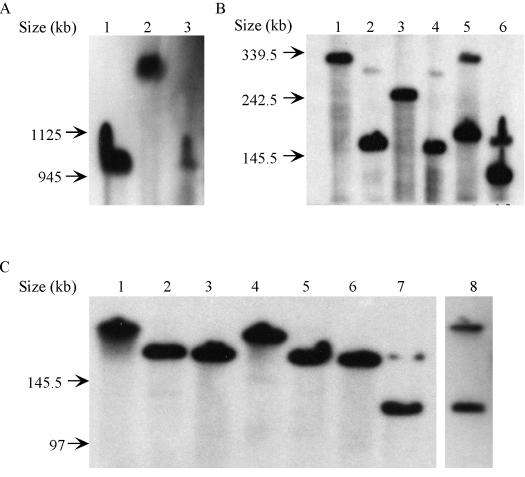

Complete digestions of the wMelPop genome were carried out, and the different migration profiles were used to order the digested fragments (Fig. 1). For example, FseI has only one restriction site in the wMelPop genome, whereas AscI has two sites (17). The two fragments produced by AscI digestion of wMelPop were designated AscBF (the large fragment) and AscSF (the small fragment) (17). Double digestion with AscI and FseI determined that the FseI site is located in AscBF (Fig. 1E, lane 4). Southern hybridization with probes derived from plasmids (Table 1) showed that atpA is located in AscBF (Fig. 2A, lanes 1 and 2) and, specifically, the smallest fragment produced by double digestions with AscI and FseI (AFSF) (Fig. 2C, lane 8). In addition, Southern blots placed atpA on fragments with sizes all bigger than AFSF, which were digested with either ApaI and AscI (Fig. 2C, lane 3), SmaI and AscI (Fig. 2B, lane 4, and C, lane 5), or ApaI, SmaI, and AscI (Fig. 2C, lane 6). These results indicate that neither ApaI nor SmaI has a recognition site in AFSF. Therefore, the atpA gene was used as an end-labeling probe to order the fragments that resulted from ApaI or SmaI partial digests of AscBF (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

PFGE of digested wMelPop genomic DNA. (A) Lane 1, 8- to 48-kb ladder; lane 2, 1-kb ladder; lanes 3 to 9, digested genome; lane 3, ApaI; lane 4, SmaI; lane 5, ApaI and SmaI; lane 6, ApaI and AscI; lane 7, SmaI and AscI; lane 8, ApaI, SmaI, and AscI; lane 9, ApaI, SmaI, and FseI. (B) Lane 1, low-range pulsed-field gel marker; lanes 2 to 9, digested genome; lane 2, ApaI; lane 3, SmaI; lane 4, ApaI and SmaI; lane 5, AscI; lane 6, ApaI and AscI; lane 7, SmaI and AscI; lane 8, FseI and ApaI; lane 9, FseI and SmaI. (C) Lane 1, λ ladder; lane 2, 8- to 48-kb ladder; lanes 3 to 9, digested genome; lane 3, ApaI; lane 4, SmaI; lane 5, ApaI and SmaI; lane 6, ApaI and AscI; lane 7, SmaI and AscI; lane 8, ApaI, SmaI, and AscI; lane 9, ApaI, SmaI, and FseI. (D) Lane 1, λ ladder; lanes 2 to 9, digested genome; lane 2, ApaI; lane 3, SmaI; lane 4, ApaI and SmaI; lane 5, ApaI, AscI, and SmaI; lane 6, ApaI and AscI; lane 7, SmaI and AscI; lane 8, ApaI, SmaI, and FseI; lane 9, ApaI, AscI, and SmaI and FseI; lane 10, yeast chromosomal marker. (E) Lane 1, yeast chromosomal marker; lanes 2 to 4, digested genome; lane 2, AscI; lane 3, FseI; lane 4, AFSF.

FIG. 2.

Autoradiographs of Southern blots of PFGE gels of digested wMelPop genome probed with the atpA gene fragment. (A) Lane 1, AscI; lane 2, FseI; lane 3, AFSF. (B) Lane 1, ApaI; lane 2, SmaI; lane 3, ApaI and SmaI; lane 4, SmaI and AscI; lane 5, ApaI and FseI; lane 6, SmaI and FseI. (C) Composite Southern blots. Lane 1, ApaI; lane 2, SmaI; lane 3, ApaI and SmaI; lane 4, ApaI and AscI; lane 5, SmaI and AscI; lane 6, ApaI, SmaI, and AscI; lane 7, ApaI, SmaI, and FseI; lane 8, AFSF. FseI usually does not digest completely, which is indicated by the presence of two labeled DNA fragments in lanes where FseI was used.

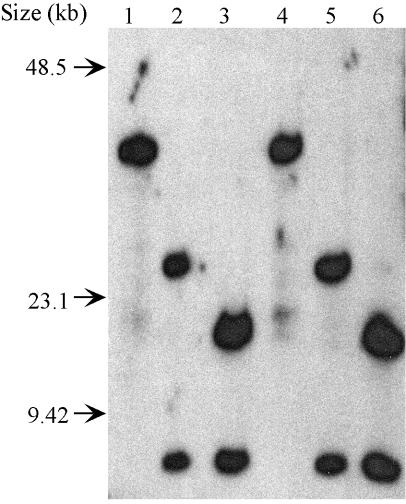

Southern hybridization with probes designed from the wMel whole genome sequence was used to further ascertain neighboring fragments (Fig. 3). Although some of the probes harboring a restriction site of interest were derived from the wMel genome, these probes were also capable of successfully hybridizing to wMelPop restriction fragments. Finally, we used genome sequence of wMel to design primers to PCR amplify and sequence two small regions of the wMelPop chromosome to complete the map. These two regions were designated pccBwMelPop (the pccB gene region harboring two ApaI sites <1 kb apart) and cysSwMelPop (the cysS gene region containing one ApaI site and one SmaI site, also <1 kb apart). The two PCR fragments have high sequence similarity to their counterparts in the wMel genome (99.6% for pccBwMelPop and 99.9% for cysSwMelPop) and share the same restriction sites for ApaI and SmaI. Based on analyses combining all of the data obtained from complete digestions, partial digestions, Southern hybridizations, and sequencing, a physical and genetic map of the wMelPop genome was constructed (Fig. 4).

FIG.3.

Autoradiograph of a Southern blot of Digested wMelPop genome probed with trmD gene fragment (harboring SmaI site). Lane 1, ApaI; lane 2, SmaI; lane 3, ApaI and SmaI; lane 4, ApaI and AscI; lane 5, SmaI and AscI; lane 6, ApaI, AscI, and SmaI.

FIG. 4.

A physical and genetic map of the wMelPop genome. Arrows point to the location of genes determined by Southern hybridization (see Tables 1 to 3). Short bars indicate probes that contain the indicated restriction site. Numbers indicate the sizes of restriction fragments.

When a comparison is made between the map of wMelPop and the unfinished sequence of the wMel genome, considerable conservation is seen. For example, most restriction sites mapped to the wMelPop genome are in the same order and location in the unfinished wMel genome, with the exception of a single ApaI site. Similarly, when all of the genes mapped to the wMelPop restriction fragments are compared to the unfinished wMel genome, there appears to be almost complete synteny between the two genomes at the resolution afforded by Southern hybridization. However, there appears to be an inversion of fragment containing pcnB, sdhA, and msbA genes between the strains.

The pcnB gene is located between the fold gene and the sdhA gene in the wMel genome, on the same ApaI-SmaI restriction fragment as the sdhA gene, whereas the homolog in the wMelPop genome is localized on the same ApaI-ApaI restriction fragment as the lipA gene (Fig. 4). The msbA gene is located between the fold gene and the sdhA gene in the wMelpop genome, on the same ApaI-SmaI restriction fragment as the sdhA gene (Fig. 4), whereas the homolog in the wMel genome sits on the same ApaI-ApaI restriction fragment as the lipA gene. The ApaI site separating the fragment harboring the sdhA gene and the fragment harboring the ftsW gene appears rearranged. After complete digestion with the four enzymes used in the present study, the fragment harboring the sdhA gene has an estimated size of 66 kb in the wMelPop genome, which is smaller than the corresponding fragment (125 kb) in the wMel genome. The neighboring fragment harboring the ftsW gene has an estimated size of 200 kb in the wMelPop genome and only 140 kb in the wMel genome. The translocation of the msbA gene and the pcnB gene may be linked events. The simplest potential explanation for the observed differences would be one inversion event: the two breakpoints are between lipA-msbA and fold-pcnB fragments.

Higher-resolution mapping of this chromosomal region of the wMelPop genome will be needed to determine the exact nature of the inversion event. This chromosomal region in wMel is known to contain prophage sequences, and it is possible that the observed differences between these two strains may be due to phage-mediated events. A better understanding of these rearrangements and potential insertion/deletion events may also indicate putative genes associated with the virulence phenotype of the wMelPop strain in Drosophila.

Acknowledgments

We thank Serap Aksoy, Liangbiao Zheng, and Diane McMahon-Pratt for the use of equipment associated with this study; Shinji Masui for providing plasmids containing Wolbachia gene fragments for use as probes; and Patricia Strickler for technical support. Preliminary genome sequence data for wMel was provided by Jonathan Eisen.

This study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health and the McKnight foundation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arakaki, N., T. Miyoshi, and H. Noda. 2001. Wolbachia-mediated parthenogenesis in the predatory thrips Franklinothrips vespiformis (Thysanoptera: Insecta). Proc. R. Soc. London Ser. B Biol. Sci. 268:1011-1016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bandi, C., T. J. Anderson, C. Genchi, and M. L. Blaxter. 1998. Phylogeny of Wolbachia in filarial nematodes. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. B Biol. Sci. 265:2407-2413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Birren, B. W., E. Lai, L. Hood, and M. I. Simon. 1989. Pulsed field gel electrophoresis techniques for separating 1- to 50-kilobase DNA fragments. Anal. Biochem. 177:282-286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chu, G., D. Vollrath, and R. W. Davis. 1986. Separation of large DNA molecules by contour-clamped homogeneous electric fields. Science 234:1582-1585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fialho, R. F., and L. Stevens. 2000. Male-killing Wolbachia in a flour beetle. Proc. R. Soc. London Ser. B Biol. Sci. 267:1469-1473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fujii, Y., D. Kageyama, S. Hoshizaki, H. Ishikawa, and T. Sasaki. 2001. Transfection of Wolbachia in Lepidoptera: the feminizer of the adzuki bean borer Ostrinia scapulalis causes male killing in the Mediterranean flour moth Ephestia kuehniella. Proc. R. Soc. London Ser. B Biol. Sci. 268:855-859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6a.Hoffmann, A. A., and M. Turelli. 1997. Cytoplasmic incompatibility in insects, p. 42-80. In S. L. O’Neill, A. A. Hoffmann, and J. H. Werren (ed.), Influential passengers: inherited microorganisms and arthropod reproduction. Oxford University Press, Oxford, United Kingdom.

- 7.Holmes, D. S., and J. Bonner. 1973. Preparation, molecular weight, base composition, and secondary structure of giant nuclear ribonucleic acid. Biochemistry 12:2330-2338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hurst, G. D., A. P. Johnson, J. H. Schulenberg, and Y. Fuyama. 2000. Male-killing Wolbachia in Drosophila, a temperature-sensitive trait with a threshold bacterial density. Genetics 156:699-709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hurst, G. D. D., L. D. Hurst, and M. E. N. Majerus. 1997. Cytoplasmic sex-ratio distorters, p. 125-154. In S. L. O'Neill, A. A. Hoffmann, and J. H. Werren (ed.), Influential passengers: inherited microorganisms and arthropod reproduction. Oxford University Press, Oxford, United Kingdom.

- 10.Jeyaprakash, A., and M. A. Hoy. 2000. Long PCR improves Wolbachia DNA amplification: wsp sequences found in 76% of sixty-three arthropod species. Insect Mol. Biol. 9:393-405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Langworthy, N. G., A. Renz, U. Mackenstedt, K. Henkle-Duhrsen, M. B. de Bronsvoort, V. N. Tanya, M. J. Donnelly, and A. J. Trees. 2000. Macrofilaricidal activity of tetracycline against the filarial nematode Onchocerca ochengi: elimination of Wolbachia precedes worm death and suggests a dependent relationship. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 267:1063-1069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McGraw, E. A., D. J. Merritt, J. N. Droller, and S. L. O'Neill. 2002. Wolbachia density and virulence attenuation after transfer into a novel host. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:2918-2923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McGraw, E. A., D. J. Merritt, J. N. Droller, and S. L. O'Neill. 2001. Wolbachia-mediated sperm modification is dependent on the host genotype in Drosophila. Proc. R. Soc. London Ser. B Biol. Sci. 268:2565-2570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Min, K. T., and S. Benzer. 1997. Wolbachia, normally a symbiont of Drosophila, can be virulent, causing degeneration and early death. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:10792-10796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rigaud, T. 1997. Inherited microorganisms and sex determination of arthropod hosts, p. 81-101. In S. L. O'Neill, A. A. Hoffmann, and J. H. Werren (ed.), Influential passengers: inherited microorganisms and arthropod reproduction. Oxford University Press, Oxford, United Kingdom.

- 16.Stouthamer, R. 1997. Wolbachia-induced parthenogenesis, p. 102-124. In S. L. O'Neill, A. A. Hoffmann, and J. H. Werren (ed.), Influential passengers: inherited microorganisms and arthropod reproduction. Oxford University Press, Oxford, United Kingdom.

- 17.Sun, L. V., J. M. Foster, G. Tzertzinis, M. Ono, C. Bandi, B. E. Slatko, and S. L. O'Neill. 2001. Determination of Wolbachia genome size by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. J. Bacteriol. 183:2219-2225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Taylor, M. J., and A. Hoerauf. 1999. Wolbachia bacteria of filarial nematodes. Parasitol. Today 15:437-442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weeks, A. R., and J. A. Breeuwer. 2001. Wolbachia-induced parthenogenesis in a genus of phytophagous mites. Proc. R. Soc. London Ser. B Biol. Sci. 268:2245-2251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Werren, J. H., and D. M. Windsor. 2000. Wolbachia infection frequencies in insects: evidence of a global equilibrium? Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 267:1277-1285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Werren, J. H., W. Zhang, and L. R. Guo. 1995. Evolution and phylogeny of Wolbachia: reproductive parasites of arthropods. Proc. R. Soc. London Ser. B Biol. Sci. 261:55-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]