Abstract

We examined the relationship between social discrimination, violence, and illicit drug use among an ethnically diverse cohort of young men who have sex with men (YMSM) residing in Los Angeles. 526 YMSM (ages 18–24 years) were recruited using a venue-based, stratified probability sampling design. Surveys assessed childhood financial hardship, violence (physical assault, sexual assault, intimate partner violence), social discrimination (homophobia and racism), and illicit drug use in the past 3 months. Analyses examined main and interaction effects of key variables on drug use. Experiences of financial hardship, physical intimate partner violence and homophobia predicted drug use. Although African American participants were less likely to report drug use than their Caucasian peers, those who experienced greater sexual racism were at significantly greater risk for drug use. Racial/ethnic minority YMSM were at increased risk for experiencing various forms of social discrimination and violence that place them at increased risk for drug use.

Keywords: harassment, discrimination, violence, illicit drug use, YMSM

Introduction

Young men who have sex with men (YMSM)a constitute one of the most vulnerable groups in the United States for HIV infection, showing unacceptably high rates of unprotected anal intercourse, HIV seroprevalence, and incidence (Centers for Disease Control, 2008; Valleroy et al., 2000). Research has consistently shown robust associations between the reported use of illicit drugs and substantially heightened sexual risk for HIV infection among MSM (Chesney, Barrett, & Stall, 1998; Ostrow, Beltran, Joseph, DiFrancisco, & Group, 1993; Page-Shafer et al., 1997). In a comprehensive review of the literature, Halkitis, Parsons & Stirratt (2001) cited 21 studies, published between 1986 and 1997, documenting the relationship between drug use and sexual risk behavior and 11 publications showing the specific relationship between methamphetamine use and HIV seroconversion (Halkitis et al., 2001).

While it is now well understood that most young adults will experiment with alcohol and drugs at some point during their teens (Arnett, 2000), emerging adult YMSM (those between the ages 18–24) are significantly more likely than their heterosexual peers to report lifetime and recent use of illicit drugs (Kipke, Weiss, Ramirez et al., 2007; Wolitski, Valdiserri, Denning, & Levine, 2001). Although YMSM use illicit drugs for many of the same reasons as their heterosexual peers, researchers and social service practitioners believe YMSM are more likely to use illicit drugs because of the rejection, stigmatization, and social isolation that many experience due to their sexual orientation (D’Augelli & Herschberger, 1993; Harper & Schneider, 2003; Meyer, 2003; Savin-Williams, 1990). Furthermore, many YMSM avoid disclosure of their sexuality out of fear of rejection by peers or family members (Rosario, Hunter, Maguen, Gwadz, & Smith, 2001; Savin-Williams, 1990), which in turn may be associated with increased drug use (Greenwood et al., 2001). Rather than feeling alone and isolated, many YMSM may seek out and begin to spend time in gay-identified venues, such as gay bars, where they may find acceptance, but also have unfettered access to alcohol and illicit substances (McKirnan, Ostrow, & Hope, 1996). Other established risk factors associated with high levels of drug use among YMSM include a history of childhood sexual abuse (Hughes & Eliason, 2002), stressful life events (Rosario, Schrimshaw, & Hunter, 2004; Wong, Kipke, Weiss, & McDavitt, in press), gay-related verbal harassment and discrimination (Rosario, Rotheram-Borus, & Reid, 1996), and involvement in gay-related social events (Rosario et al., 2004). Despite that fact that the vast majority of these studies have been descriptive in nature and conducted with small, non-representative convenience samples, emerging evidence suggests that exposure to harassment, discrimination, and physical abuse predicted later adult health problems among YMSM including HIV infection, depression, and partner abuse (Friedman, Marshal, Stall, Cheong, & Wright, 2008), and mental health problems including lower self-esteem and increased suicidal ideation (Huebner, Rebchook, & Kegeles, 2004). Although the link between experiences of social discrimination and the sexual risk for HIV has been established in the research literature (Diaz, Ayala, & Bein, 2004; Malebranche, 2003; Meyer, 1995; Millett, Peterson, Wolitski, & Stall, 2006; Stokes & Peterson, 1998), as has the association between intimate partner violence, histories of childhood sexual abuse and HIV risk with adult MSM populations (Arreola, 2006; Jinich et al., 1998; Lenderking et al., 1997; Strathdee et al., 1998), less is known about the impact these experiences have on YMSM’s sexual health in general and their drug use behaviors in particular.

In this paper, we report the prevalence of social discrimination – specifically experiences of racism and homophobia and violence, including lifetime experiences of physical and sexual assault, as well as intimate partner violence. We examine the relationship between these experiences and drug use within a large and ethnically diverse sample of YMSM recruited using a venue-based, probability sampling design as part of the Healthy Young Men’s (HYM) Study.

Methods

Study Description, Population, & Recruitment

The overarching goal of the HYM Study was to longitudinally track a large and ethnically diverse cohort of YMSM, ages 18–22, to characterize the individual, familial, social, and community level risk and protective factors associated with drug use and HIV risk, with the ultimate goal being to use this information to develop new interventions for prevention. Recruitment occurred over the course of a year to control for seasonal variations within the venues (e.g., gay bars, clubs, raves, public spaces such as parks). Once recruited into the study, each participant completed a baseline survey, with four follow-up assessment surveys scheduled every six months. In addition, qualitative interviews have been conducted with targeted segments of the cohort to further clarify and contextualize key study findings. Present findings come from the baseline assessment. This research received Institutional Review Board approval.

A total of 526 subjects were recruited into the study between February of 2005 and January of 2006. Young men were eligible to participate in the study if they: a) were 18- to 24-years old; b) self-identified as gay, bisexual, or uncertain about their sexual orientation and/or reported having had sex with a man; c) self-identified as Caucasian, African American, or Latino of Mexican descent; and d) were a resident of Los Angeles County and anticipated living in Los Angeles for at least the next six months. The sample was stratified by ethnicity to ensure comparable numbers within the three racial/ethnic groups.

YMSM were recruited at public venues using the stratified probability sampling design developed by the Young Men’s Study (MacKellar, Valleroy, Karon, Lemp, & Janssen, 1996) and later modified by the Community Intervention Trials for Youth (Muhib et al., 2001). Public venues included settings and events at which YMSM were observed to spend time or “hang out”, such as bars, coffee houses, parks, beaches, and high-traffic street locations; social events such as a picnic or baseball game sponsored by a youth-serving, community-based agency; and special events such as gay pride festivals. Detailed descriptions of the sampling methods can be found elsewhere (Kipke, Weiss, Ramirez et al., 2007; Kipke, Weiss, & Wong, 2007).

Study Instrument

The survey was administered in both English and Spanish using audio, computer-assisted interview (ACAI) technologies. ACAI technologies have increasingly been found to improve both the quality of the data being collected and the validity of subjects’ responses, particularly when questions were of a sensitive nature, such as drug use and sexual behavior (Turner et al., 1998). The survey included 1,109 items and required 1- to 1–1/2 hours to complete. Participants received $35 to compensate them for their time and effort. Analyses were performed to examine the following variables:

Demographic variables

Participants were asked to report their age; race/ethnicity; sexual identity; place of birth; immigration status; current place of residence; and whether they were attending school and/or employed.

Childhood financial hardship

Given that socio-economic status has often been found to be associated with domestic violence and abuse, this is an important variable to consider in the current study. However, because of the difficulty in discerning childhood socio-economic status, we approximated childhood financial situation by asking if participants experienced three different types of financial hardship while growing up: 1) whether they had ever lived with a friend or relative because of financial difficulty; 2) whether they had lived without light or heat because of financial difficulty; and 3) whether a person or people with whom they lived had ever receive public assistance. These items were added to that ranged from 0 (none experienced) to 3.

Violence

Physical assault while growing up was assessed by asking participants if they had ever been hit so hard by someone in their home that it had left a bruise or they had required medical help. Lifetime experience of sexual assault was based on two items that assessed whether participants had ever been sexually abused or assaulted when growing up or as an adult. To measure intimate partner violence, we adapted a scale developed by Smith, Earp & DeVellis (1995) to measure intimate partner violence among battered women. This scale contains 12 items that assess whether participants have ever been victims of various types of intimate partner violence (i.e., physical, sexual, emotional abuse), and 3 items that assess whether they have ever perpetrated intimate partner physical violence. Cronbach’s alpha for the overall scale was 0.83.

Social discrimination

Experiences of homophobia and racism growing up and as an adult were measured using two scales developed by Diaz and his colleagues (2004). Eleven items were used for each measure. To measure experiences of homophobia, we used items measuring verbal harassment and physical assaults in relation to both perceived sexual orientation and gender nonconformity. To measure racism, we chose both general items measuring institutional forms of racism, physical assault due to race, and items that focused on experiences of racism in gay social settings and/or sexual relationships. All items used a 4-item response format (1= never, 2 = once or twice, 3 = a few times and 4 = many times). Alphas calculated for these scales were .72 and .82, respectively.

Recent illicit drug use

Participants were asked about their recent (past 3- month) use of illicit drugs including marijuana, crack, LSD, PCP, mushrooms, cocaine, crystal/methamphetamine, other stimulants, ecstasy, GHB, Ketamine, poppers, and prescription drugs used without a physician’s order, such as anti-anxiety medications, depressants, anti-depressant medication, sedatives, opiates/narcotics, and medications for attention deficit disorder. In this paper, recent use of illicit drugs refers to past 3-month use of any one of these drugs, with the exception of marijuana.

Statistical Analysis

Confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) were conducted on each of the key measures of violence and social discrimination: intimate partner violence, homophobia, and racism, to examine whether subscales that make theoretical sense can be statistically substantiated. The integrity and structure of developed subscales were evaluated and verified using Mplus (v. 5.02). Summary scores based on results of the factor analyses then were used for subsequent analyses.

Descriptive analyses characterized the demographic composition and prevalence of experiences of different types of violence and victimization both as children and as adults, for the entire sample. Next, we examined the way these variables differed across the three racial/ethnic groups using Pearson Chi-squared tests and Analysis of Variance (ANOVA). In instances when the assumption of homogeneity of variance was violated, results from the Welch statistic were used. Bivariate analyses were used to test the main effects of violence and victimization variables, and key covariates on recent illicit drug use. Then, multiple logistic regression analyses were performed to examine which of the significant (p < .05) main effects for the violence and victimization variables at the bivariate level remained significantly associated with recent drug use, while simultaneously adjusting for the effects of covariates and other independent variables. Because we were interested in testing the way race/ethnicity moderates the effects of violence and victimization on drug use, we also included those variables that were significantly different (p < .05) by race/ethnicity at the bivariate level. Correlations and collinearity diagnostics were examined to ensure that there was no evidence of multicollinearity among the variables entered. Using a step-wise approach, main effects from bivariate analyses that did not contribute to the overall prediction of the model at p < .10 were dropped until the most stable and parsimonious model was reached. The Homser–Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test was used to assess model fit at each step. All continuous predictors were grand-mean centered and dichotomized predictors were coded 0 and 1 before being added to the multiple regression model. The centering procedure was used to minimize multicollinearity between predictors and corresponding interaction terms and to allow greater ease of testing and interpreting significant interaction terms (Cohen, Cohen, West, & Aiken, 2003).

Interaction terms, represented by the cross-product of each dummy-coded ethnicity variable and violence/victimization variable were entered in a separate step in a hierarchical logistic multiple regression model. Interaction terms included in the analyses were those comprised of violence and victimization variables that significantly differed by race/ethnicity at the bivariate level. The analytical procedures used to test moderation followed those described by Baron and Kenny (1986).

Results

Factor Analyses

Results from the factor analyses produced four subscales for intimate partner violence (IPV) and three subscales each for homophobia and racism. The four IPV subscales included: 1) emotional abuse (e.g., being threatened, insulted, or made to feel stupid); 2) sexual abuse (e.g., receiving demands for sex, whether or not wanted); 3) physical abuse (e.g., slapping or punching with a fist); and 4) perpetrating physical violence (e.g., using a weapon to hurt the partner). The overall fit of the measurement model for IPV was good (Chi2(30)=32.89; CFI/TLI=.99/.99; RMSEA (Root Mean Square Error of Approximation)=.014). Subscales of homophobia included: 1) experience of homophobia while growing up (e.g., hearing that homosexuals are sinners and will go to hell); 2) evading or managing sexual identity to avoid negative consequences (e.g., moving away from friends and family); and 3) experience of more extreme forms of homophobic discrimination (e.g., lost of a job or career for being a homosexual, harassment by police for being homosexual). The overall fit of the measurement model for homophobia was also acceptable (Chi2(29)=70.32; CFI/TLI=.97/.97; RMSEA=.05). Finally, subscales of racism included 1) experience of racism in gay social settings and/or sexual relationships (e.g., made to feel uncomfortable in a gay bar/club; difficulty establishing a relationship because of your race or ethnicity); 2) experience of institutional racism (e.g., being denied a job because of your race, harassment by police because of your race); and 3) experience of physical assault because of race (e.g., getting beat up because of your race). The fit of this model also was adequate (Chi2(24)=40.39; CFI/TLI=.98/.98; RMSEA=.04).

Descriptive Findings

As summarized in Table 1, the sample of 526 YMSM included: 195 (37%) Caucasians (C), 126 (24%) African Americans (AA), and 205 (39%) Latinos of Mexican descent (M). The average age was 20.1 years, with 39% of the sample being 18–19 years of age. Thirty percent of the Latino respondents reported having been born outside of the US. More than half (53%) of the respondents reported living at home with their family, and 87% reported being in school and/or employed. Latino participants were significantly more likely than Caucasian participants to report living at home with their families (Chi2(2) = 50.33; p ≤ .001). A total of 39% of the sample reported experiencing some form of financial hardship while growing up. African American participants were significantly more likely to report experiencing two or more types of financial hardships while growing up (Chi2(6) = 20.02; p ≤ .001).

Table 1.

Differences in Demographic and Violence Variables by Ethnicity

| Total | AA | M | C | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N=526 | n=126 | n=205 | n=195 | |

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| Age** | ||||

| 18–19 yrs | 206 (39) | 43 (34) | 91 (44) | 72 (37) |

| 20–21 yrs | 196 (37) | 50 (40) | 83 (40) | 63 (32) |

| 22–24 yrs | 124 (24) | 33 (26) | 31 (15) | 60 (31) |

| Sexual Identity* | ||||

| Gay | 391 (74) | 81 (64) | 151 (74) | 159 (82) |

| Other same-sex identity | 47 (9) | 17 (13) | 16 (8) | 14 (7) |

| Bisexual/straight | 88 (17) | 28 (22) | 38 (19) | 22 (11) |

| Number of Childhood Financial Hardshipsa when Growing Up*** | ||||

| None | 311 (61) | 63 (52) | 107 (54) | 141 (73) |

| 1 | 118 (23) | 29 (24) | 58 (29) | 31 (16) |

| 2 | 62 (12) | 24 (20) | 25 (13) | 13 (7) |

| 3 | 22 (4) | 6 (5) | 8 (4) | 8 (4) |

| Residential Status*** | ||||

| Not living with family | 245 (47) | 61 (48) | 59 (29) | 125 (64) |

| Living with family | 281 (53) | 65 (52) | 146 (71) | 70 (36) |

| School/work | ||||

| In school | 113 (22) | 27 (17) | 46 (24) | 46 (22) |

| In school and employed | 142 (27) | 32 (25) | 62 (30) | 48 (25) |

| Not in school, employed | 201 (38) | 53 (42) | 70 (34) | 78 (40) |

| Not in school and not employed | 70 (13) | 20 (16) | 27 (13) | 23 (12) |

| Illicit Drug Use (previous 3 months)*** | 148 (28) | 22 (18) | 51 (25) | 75 (39) |

| Violence Growing Up | ||||

| Witness to physical violence in the home | 133 (25) | 33 (26) | 54 (26) | 46 (24) |

| Experienced physical violence | 104 (20) | 23 (18) | 45 (22) | 36 (18) |

| Sexual Assault (ever) | 120 (23) | 33 (26) | 42 (20) | 45 (23) |

| Intimate Partner Violence | ||||

| Emotional abuse | 217 (41) | 54 (43) | 74 (36) | 89 (46) |

| Physical abuse | 123 (23) | 26 (21) | 46 (22) | 51 (26) |

| Sexual abuse | 92 (18) | 24 (19) | 35 (17) | 33 (17) |

| Perpetrator of abuse | 65 (12) | 20 (16) | 19 (9) | 26 (13) |

| Homophobia | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) |

| Homophobia growing up* | 2.87 (0.79) | 2.77 (0.79) | 2.97 (0.76) | 2.81 (0.80) |

| Homophobic discrimination that required evasion or identity management | 1.88 (0.72) | 1.98 (0.72) | 1.83 (0.73) | 1.87 (0.69) |

| Extreme harassment Racism | 1.18 (0.33) | 1.19 (0.31) | 1.18 (0.34) | 1.18 (0.33) |

| Sexualized racism*** | 1.64 (0.58) | 1.91 (0.69) | 1.59 (0.47) | 1.52 (0.55) |

| Institutional racism*** | 1.45 (0.61) | 1.81 (0.81) | 1.43 (0.51) | 1.23 (0.41) |

| Physical assault | 1.06 (0.26) | 1.08 (0.26) | 1.07 (0.25) | 1.04 (0.26) |

Note. AA=African Americans M=Latinos of Mexican descent; C=Caucasian/Whites.

Three types of childhood financial hardships were assessed: Lived w/family/relative because of financial difficulty; without light or heat; received public assistance (ever).

p ≤ .05;

p ≤ .01;

p ≤ .001

Eighty-three percent of respondents self-identified as gay or some other same-sex sexual identity, 16% identified as bisexual, and 1% identified as straight or heterosexual, with African American participants being significantly more likely than Caucasian and Latinos to self-identify as bisexual/straight (Chi2(4) =13.11; p=.01).

Also presented in Table 1 is a summary of the participants’ experiences with respect to violence when growing up, sexual assault, intimate partner violence, homophobia, racism, and recent use of illicit drugs by race/ethnicity. Twenty-five percent of the sample reported having witnessed violence in their home while growing up; 20% reported that they had experienced physical violence resulting in a bruise and/or necessitating medical attention while growing up; and 23% reported having ever been sexually assaulted. In addition, of the different types of intimate partner violence, 41% of the group reported experiencing emotional abuse, 23% physical abuse, and 18% sexual abuse from an intimate partner; 12% reported having perpetrated violence within an intimate relationship. Caucasian participants were significantly more likely to report that they had experienced emotional and physical intimate partner violence compared to African American participants. Caucasian participants were also significantly more likely than African American and Latino participants to report recent drug use (Chi2(2)= 18.46; p ≤ .001).

With respect to experiences of homophobia and racism, 98% of the sample reported ever having experienced homophobia, 79% cited experiences of racism in gay settings and/or sexual relationships, 51% experienced institutional racism, and 8% reported having been physically assaulted because of their racial/ethnic identity. African American participants were significantly less likely to report experiences of homophobia while growing up as compared to Latino and Caucasian participants (F(2, 521) = 3.15; p ≤ .05). However, African American participants were significantly more likely to report experiences of racism in gay social settings and/or sexual relationships (Welch statistic (2, 286.16) = 13.99; p ≤ .001) or institutional racism (Welch statistic (2, 274.46) = 30.70; p ≤ .001), when compared to Latinos and Caucasians.

Bivariate-level Associations

Bivariate associations between demographic covariates, discrimination, violence, and recent illicit drug use are presented in Table 2. The following were each associated with greater drug use: having experienced all three of the assessed childhood financial hardships and not being in school and/or employed (OR = 2.66; 95%CI (1.11–6.36); p ≤ .05; OR = 1.94; CI (.99–3.78); p ≤ .05 respectively). Participants were significantly less likely to report drug use if they were living at home with family (OR = .52; CI (0.36–0.77); p ≤ .001). Among the different types of intimate partner violence, physical violence (OR = 2.13; CI (1.39–3.26); p ≤ .001) and being the perpetrator of violence (OR = 1.85; CI (1.08–3.17); p ≤ .05) were associated with increased risk for recent drug use. Additionally, respondents who experienced extreme homophobia were found to have increased risk for drug use (OR = 2.03; CI (1.18–3.5); p ≤ .01). On the other hand, experiences of institutional racism were found to be associated with decreased risk for recent drug use (OR = .71; CI (.50–1.0); p ≤ .05).

Table 2.

Bivariate Logistic Regression Analyses between Demographic, Discrimination, Violence and Recent Drug Use (N = 526)

| nb(%)c | OR | (95% CI) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Racial/Ethnic Group | ||||

| Caucasian | 75 (39) | 1.00 | ||

| African American*** | 22 (18) | 0.34 | (0.20, 0.58) | 0.00 |

| Latino of Mexican descent** | 51 (25) | 0.53 | (0.35, 0.81) | 0.00 |

| Age | ||||

| 18–19 yrs | 53 (26) | 1.00 | ||

| 20–21 yrs | 52 (27) | 1.04 | (0.67, 1.60) | 0.85 |

| 22–24 yrs | 43 (35) | 1.53 | (0.94, 2.49) | 0.08 |

| Sexual Identity | ||||

| Gay | 114 (29) | 1.00 | ||

| Other same-sex identity | 14 (30) | 1.03 | (0.53, 2.00) | 0.93 |

| Bisexual/straight | 20 (23) | 0.75 | (0.43, 1.29) | 0.30 |

| Number of Financial Hardship when Growing Up | ||||

| None | 85 (27) | 1.00 | ||

| 1 | 32 (27) | 0.99 | (0.61, 1.59) | 0.97 |

| 2 | 18 (29) | 1.09 | (0.60, 1.99) | 0.78 |

| 3* | 11 (50) | 2.66 | (1.11, 6.36) | 0.03 |

| Residential Status | ||||

| Not living with family | 86 (35) | 1.00 | ||

| Living with family*** | 62 (22) | 0.52 | (0.36, 0.77) | 0.00 |

| School/work | ||||

| In school | 24 (21) | 1.00 | ||

| In school and employed | 37 (26) | 1.31 | (0.73, 2.35) | 0.37 |

| Not in school, employed | 63 (31) | 1.69 | (0.99, 2.91) | 0.06 |

| Not in school and not employed* | 24 (34) | 1.94 | (0.99, 3.78) | 0.05 |

| Violence Growing Up | ||||

| Witness physical violence in the home | 45 (34) | 1.44 | (0.94, 2.20) | 0.09 |

| Experienced physical violence | 36 (35) | 1.47 | (0.93, 2.32) | 0.10 |

| Sexual Assault (ever) | ||||

| No | 108 (27) | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 40 (33) | 1.38 | (0.89, 2.14) | 0.15 |

| Intimate Partner Violence | ||||

| Emotional abuse | 66 (30) | 1.21 | (0.82, 1.78) | 0.33 |

| Physical abuse*** | 50 (41) | 2.13 | (1.39, 3.26) | 0.00 |

| Sexual abuse | 28 (30) | 1.15 | (0.70, 1.87) | 0.59 |

| Perpetrator of abuse* | 26 (40) | 1.85 | (1.08, 3.17) | 0.03 |

| Mb (SD) | OR | (95% CI) | p value | |

| Homophobia | ||||

| Homophobia growing up | 2.84 (0.78) | 0.95 | (0.75, 1.21) | 0.70 |

| Homophobic discrimination that required evasion or identity management | 1.88 (0.77) | 1.00 | (0.77, 1.30) | 0.99 |

| Extreme Harassment** | 1.24 (0.37) | 2.03 | (1.18, 3.50) | 0.01 |

| Racism | ||||

| Sexualized racism | 1.65 (0.61) | 1.02 | (0.73, 1.42) | 0.91 |

| Institutional racism* | 1.36 (0.50) | 0.71 | (0.50, 1.00) | 0.05 |

| Physical assault | 1.08 (0.58) | 1.35 | (0.67, 2.70) | 0.40 |

Three types of childhood financial hardships were assessed: Lived w/family/relative because of financial difficulty; without light or heat; received public assistance (ever)

Number or mean of those who did illicit drugs in the previous 3 months for each variable

% is based on among those within each category, how many did illicit drugs

p ≤ .05;

p ≤ .10;

p ≤ .001

Multivariate Associations: Main Effects and Interactions

Table 3 presents results from multiple regression analyses performed to describe racial/ethnic differences, and the effects of discrimination and violence on recent illicit drug use. After controlling for effects of childhood financial hardships, residential status, intimate partner violence, homophobia, and racism variables, African American participants were still significantly less likely to use drugs when compared to Caucasians (AOR = .35; CI (.18–.68); p ≤ .01). After simultaneously adjusting for the effects of demographic and other violence variables, analyses indicated that having experienced physical intimate partner violence and homophobia related to physical harassment continued to be associated with greater odds of drug use (AOR = 2.01; CI (1.24–3.27); p ≤ .01; and AOR = 1.98; CI (1.05–3.76); p ≤ .05, respectively). Moreover, institutional racism continued to be related to a lower likelihood of recent illicit drug use (AOR = .62; CI (.40–.98); p ≤ .05).

Table 3.

Multivariate Model of Demographic, Discrimination, and Violence Predicting Recent Drug Use (N = 510)a

| Recent Illicit drug use (not including marijuana) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| OR | (95% CI) | p value | |

| Racial/Ethnic Group | |||

| Caucasian | |||

| African American** | 0.35 | (0.18, 0.68) | 0.002 |

| Latino of Mexican descent | 0.77 | (0.47, 1.27) | 0.310 |

| Number of Childhood Financial Hardship when Growing Up | |||

| None | 1.00 | ||

| 1 | 1.15 | (0.69, 1.90) | 0.600 |

| 2 | 1.37 | (0.67, 2.68) | 0.361 |

| 3+ | 2.58 | (0.96, 6.94) | 0.061 |

| Residential Status | |||

| Living with family* | 0.63 | (0.41, 0.97) | 0.036 |

| Intimate Partner Violence | |||

| Physical abuse** | 2.01 | (1.24, 3.27) | 0.005 |

| Homophobia | |||

| Homophobia growing up+ | 0.76 | (0.57, 1.02) | 0.064 |

| Extreme harassment* | 1.98 | (1.05, 3.76) | 0.036 |

| Racism | |||

| Sexualized racism | 0.81 | (0.45, 1.46) | 0.490 |

| Institutional racism* | 0.62 | (0.40, 0.98) | 0.042 |

| Interaction termsb | |||

| African American X sexualized racism* | 2.62 | (1.07, 6.50) | 0.036 |

| Latino Mexican descent X sexualized racism+ | 2.39 | (0.96, 5.94) | 0.060 |

Note. All continuous variables are grand-mean centered and all dichotomous variables are coded 0, 1.

16 cases were excluded from multivariate analyses due to missing values.

Interaction terms shown are part of the final multivariate model testing whether the effect of sexual racism on drug use differ by race/ethnicity after adjusting for main effects.

p ≤ .10;

p ≤ .05;

p ≤ .10;

p ≤ .001

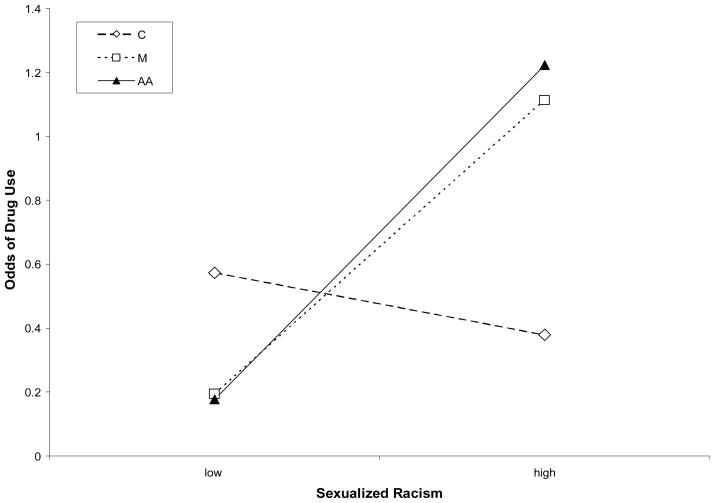

Among the interaction terms between ethnicity and variables related to experiences of violence considered in the multivariate model, what remained significant was the interaction term related to African American ethnicity and the experience of racism in gay social settings and/or sexual relationships (Wald = 4.39; p ≤ .05). The interaction term for Latinos and the experience of racism in gay social settings and/or sexual relationships was nearly significantly associated (Wald = 3.53; p ≤ .10). The significance or near significance of these interaction terms indicated that the effects of racism that occurs in gay social settings and/or sexual relationships on drug use differed between the three ethnic groups. Because of the dummy-coded nature of the ethnicity variables, the unstandardized regression coefficient for the sexualized racism variable actually represents the slope of the Caucasian cohort. The interaction terms of the other ethnic groups each represent the slope of the variable within each of these groups. A plot depicting the interactions (see Figure 1) shows that the risk for drug use was higher for African American YMSM, compared to Caucasian YMSM, when they experienced high level of sexualized racism (AOR = 2.62; CI (1.07–6.50); p = .036). Though a trend, Figure 1 also shows that the risk for drug use among Latinos of Mexican descent was higher when reported high levels of sexualized racism (AOR = 2.39; CI (.96–5.94); p =.06). As expected, the slope of the line for the Caucasian cohort was not significantly different from zero.

Figure 1.

Plot depicting the interaction between experiences of sexualized racism and drug use for each racial/ethnic group.

Discussion

In this study, we found that YMSM recruited from gay-identified venues are a heterogeneous population, with a sizable proportion reporting experiences of homophobia, racism, and violence, which in turn, were significantly associated with recent illicit drug use. A greater number of financial hardships experienced and having witnessed violence while growing up was significantly associated with illicit drug use among YMSM in this study. Homophobia also was strongly associated with drug use. In addition, we found important racial/ethnic differences in exposure to various forms of homophobia, racism, and violence, and recent involvement in illicit drug use. Specifically, we found that participants varied in the type of intimate partner violence experienced. African American participants were more likely to report sexual intimate partner violence and being the perpetrator of intimate partner violence, while Caucasian participants were more likely to report physical or emotional intimate partner violence than their counterparts. African American participants were significantly less likely to report experiences of homophobia while growing up as compared to Latino and Caucasian participants, but were significantly more likely than the other groups to report experiences of institutional racism and racism in gay social settings and/or sexual relationships. Caucasian participants were significantly more likely than African American and Latino participants to report recent illicit drug use.

While these findings provide new evidence with respect to a range of risk factors associated with illicit drug use within this population, there are a number of limitations within this study that need to be acknowledged. First, the findings rely on respondents’ self-reported behaviors, which cannot be independently verified. Self-report data regarding respondents’ risk behaviors may have underestimated the true prevalence given that some of these behaviors may be perceived as socially undesirable, although we expect that the use of CAI may have minimized the underreporting in these behaviors (Kissinger et al., 1999; Ross, Tikkanen, & Mansoon, 2000; Turner et al., 1998). A second limitation is that the data are cross-sectional and therefore do not contain information about the temporal relationship between violence and social discrimination variables with illicit drug use. Thus, no statements can be made about the causal relationship between these variables. Given that the HYM Study is a longitudinal study, we will have the opportunity to confirm whether these and other causal relationships do indeed exist. Finally, although this sample is likely to be representative of YMSM who can be recruited through gay-identified venues, this sample is certainly not representative of the larger YMSM population.

Despite these limitations, findings provide very clear evidence that segments of the YMSM population are at increased risk for experiencing various forms of social discrimination and violence that place this group of young men at increased risk for drug use. Key though was the relationship found in the current study between experiences of racism and illicit drug use. Overall, African American and Latino participants were found to be significantly less likely than Caucasians to report recent use of illicit drugs. However, among African American YMSM who experienced racism in gay social settings and/or sexual relationships, they were at significantly greater risk for recent illicit drug use. Our data underscore the need for more research on the roles that social discrimination and violence play in heightening the risk for illicit drug use, especially given the disproportionate impact of HIV/AIDS on African American and Latino MSM. Our findings also highlight the importance of examining cross-group differences among YMSM since research on this population is not often powered to conduct cross-group comparisons. Findings speak to the need for intervention content that focuses on the broad array of different types of discrimination and sources of discrimination, and for clinicians and provider to explore strategies for managing/coping with these different kinds of negative life experiences. In addition, structural interventions can help reduce the prevalence of homophobia and racism, with a clear target within the gay communities to ensure that young men of different ethnic cultural groups feel welcomed. Data reported in the aggregate often masks important racial/ethnic differences in the determinants of risk. This is a critical point from a prevention perspective as we contemplate the implications of these findings for program and intervention development.

Acknowledgments

SOURCE OF SUPPORT

This study was funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse of the National Institutes of Health (R01 DA015638–04).

Footnotes

The term of YMSM is used in this paper although it is important to note that the YMSM, as well as the adult MSM populations, are heterogeneous and not homogenous groups.

References

- Arnett JJ. Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist. 2000;55:469–480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arreola SG. Childhood sexual abuse and HIV among Latino gay men: The price of sexual silence during the AIDS epidemic. In: Tenunis N, Herdt G, editors. Sexual Inequalities and Social Justice. University of California Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control. Trends in HIV/AIDS diagnoses among men who have sex with men-33 states, 2001–2006. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2008 Retrieved August 25, 2008, from http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5725a2.htm. [PubMed]

- Chesney MA, Barrett DC, Stall RD. Histories of substance use and risk behavior: Precursors to HIV seroconversion in homosexual men. American Journal of Public Health. 1998;88:113–118. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.1.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, Cohen P, West SG, Aiken LS. Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences. xxviii. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- D’Augelli AR, Herschberger S. Lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth in community settings: Personal challenges and mental health problems. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1993;21:421–448. doi: 10.1007/BF00942151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz RM, Ayala G, Bein E. Sexual risk as an outcome of social opresion: Data from a probability sample of Latino gay men in three U.S. cities. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2004;10:255–267. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.10.3.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman MS, Marshal MP, Stall R, Cheong J, Wright ER. Gay-related development, early abuse, and adult health outcomes among gay males. AIDS and Behavior. 2008;12:891–902. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9319-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood GL, White EW, Page-Shafer K, Bein E, Osmond DH, Paul JP, et al. Correlates of heavy substance use among young gay and bisexual men: The San Francisco Young Men’s Study. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2001;61:105–112. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(00)00129-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halkitis PN, Parsons JT, Stirratt M. A double epidemic: Crystal methamphetamine drug use in relation to HIV transmission among gay men. Journal of Homosexuality. 2001;41:17–35. doi: 10.1300/J082v41n02_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper GW, Schneider M. Oppression and discrimination among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgendered people and communities: A challenge for community psychology. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2003;31:243–252. doi: 10.1023/a:1023906620085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huebner DM, Rebchook GM, Kegeles SM. Experiences of harassment, discrimination, and physical violence among young gay and bisexual men. American Journal of Public Health. 2004;94:1200–1203. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.7.1200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes TL, Eliason MJ. Substance use and abuse in lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender populations. Journal of Primary Prevention. 2002;22:263–298. [Google Scholar]

- Jinich S, Paul JP, Stall RD, Acree M, Kegeles SM, Hoff C, et al. Childhood sexual abuse and HIV risk-taking behavior among gay and bisexual men. AIDS and Behavior. 1998;2:41–51. [Google Scholar]

- Kipke MD, Weiss G, Ramirez M, Dorey F, Ritt-Olson A, Iverson E, et al. Club drug use in Los Angeles among young men who have sex with men. Substance Use & Misuse. 2007;42:1723–1743. doi: 10.1080/10826080701212261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kipke MD, Weiss G, Wong CF. Residential status as a risk factor for drug use and HIV risk among YMSM. AIDS and Behavior. 2007;11:56–69. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9204-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kissinger P, Rice J, Farley T, Trim S, Jewitt K, Margavio V, et al. Application of computer-assisted interviews to sexual behavior research. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1999;149:950–954. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenderking WR, Wold C, Mayer KH, Goldstein R, Losina E, Seage GR. Childhood sexual abuse among homosexual men: Prevalence and association with unsafe sex. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 1997;12:250–253. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1997.012004250.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKellar DA, Valleroy LA, Karon JM, Lemp GF, Janssen RS. The Young Men’s Survey: Methods for estimating HIV seroprevalence and risk factors among young men who have sex with men. Public Health Reports. 1996;111:138–144. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malebranche DJ. Black men who have sex with men and the HIV epidemic: Next steps for public health. American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93:862–865. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.6.862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKirnan DJ, Ostrow DG, Hope B. Sex, drugs, and escape: a psychological model of HIV-risk sexual behaviours. AIDS Care. 1996;8:655–659. doi: 10.1080/09540129650125371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH. Minority stress and mental health in gay men. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1995;36:38–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin. 2003;129:674–697. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millett GA, Peterson JL, Wolitski RJ, Stall RD. Greater risk for HIV infection of Black men who have sex with men: A critical literature review. American Journal of Public Health. 2006;96:1–7. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.066720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muhib F, Lin L, Steuve A, Miller R, Ford W, Johnson W, et al. The Community Intervention Trial for Youth (CITY) Study team: A venue-based method for sampling hard to reach populations. Public Health Reports. 2001;116:216–222. doi: 10.1093/phr/116.S1.216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostrow DG, Beltran ED, Joseph JG, DiFrancisco W, Group MACSM. Recreataional drugs and sexual behavior in the MACS cohort of homosexually active men. Journal of Substance Abuse. 1993;5:311–325. doi: 10.1016/0899-3289(93)90001-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page-Shafer K, Veugelers PJ, Moss AR, Strathdee S, Kaldor JM, van Griensven GJP. Sexual risk behavior and risk factors for HIV-1 seroconversion in homosexual men participating in the Tricontinental Seroconverter Study. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1997;146:531–542. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosario M, Hunter J, Maguen S, Gwadz MV, Smith RG. The coming-out process and its adaptational and health-related associations among gay, lesbian, and bisexual youths: Stipulation and exploration of a model. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2001;29:133–160. doi: 10.1023/A:1005205630978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosario M, Rotheram-Borus MJ, Reid H. Gay-related stress and its correlates among gay and bisexual adolescents of predominantly Black and Hispanic background. Journal of Community Psychology. 1996;24:136–159. [Google Scholar]

- Rosario M, Schrimshaw EW, Hunter J. Predictors of substance use over time among gay, lesbian, and bisexual youths: An examination of three hypotheses. Addictive Behaviors. 2004;29:1623–1631. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.02.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross MW, Tikkanen R, Mansoon SA. Differences between Internet and samples and conventional samples of men who have sex with men. Social Science and Medicine. 2000;4:749–758. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00493-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savin-Williams R. Gay and lesbian youth: Expressions of identity. New York: Hemisphere; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Smith E, Earp JA, DeVellis R. Measuring battering: development of the women’s experience with battering (WEB) scale. Women’s Health. 1995;4:273–288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stokes JP, Peterson JL. Homophobia, self-esteem, and risk for HIV among African American men who have sex with men. AIDS Education and Prevention. 1998;10:278–292. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strathdee SA, Hogg RS, Martindale S, Cornelisse PGA, Craib KJP, Montaner J, et al. Determinants of sexual risk-taking among young HIV-negative gay and bisexual men. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes and Human Retrovirology. 1998;19:61–66. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199809010-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner C, Ku L, Rogers S, Lindberg L, Pleck J, Sonenstein F. Adolescent sexual behavior, drug use, and violence: Increased reporting with computer survey technology. Science. 1998;280:867–873. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5365.867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valleroy LA, MacKellar DA, Karon JM, Rosen DH, McFarland W, Shehan DA. HIV prevalence and associated risks in young men who have sex with men. Journal of American Medical Association. 2000;284:198–204. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.2.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolitski RJ, Valdiserri R, Denning P, Levine W. Are we headed for a resurgence of the HIV epidemic among men who have sex with men? American Journal of Public Health. 2001;91:883–888. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.6.883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong CF, Kipke MD, Weiss G, McDavitt B. The impact of recent stressful experiences on HIV-risk related behaviors among YMSM. Journal of Adolescence. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2009.06.004. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]