Abstract

Konzo is a self-limiting central motor-system disease associated with food dependency on cassava and low dietary intake of sulfur amino acids (SAA). Under conditions of SAA-deficiency, ingested cassava cyanogens yield metabolites that include thiocyanate and cyanate, a protein carbamoylating agent. We studied the physical and biochemical modifications of rat serum and spinal cord proteins arising from intoxication of young adult rats with 50-200 mg/kg linamarin, or 200 mg/kg sodium cyanate (NaOCN), or vehicle (saline) and fed either a normal amino acid- or SAA-deficient diet for up to two weeks. Animals under SAA-deficient diet and treatment with linamarin or NaOCN developed hind limb tremors or motor weakness, respectively. LC/MS-MS analysis revealed differential albumin carbamoylation in animals treated with NaOCN, vs. linamarin/SAA-deficient diet, or vehicle. 2D-DIGE and MALDITOF/MS-MS analysis of the spinal cord proteome showed differential expression of proteins involved in oxidative mechanisms (e.g. peroxiredoxin 6), endocytic vesicular trafficking (e.g. dynamin 1), protein folding (e.g. protein disulfide isomerase), and maintenance of the cytoskeleton integrity (e.g. α-spectrin). Studies are needed to elucidate the role of the aformentioned modifications in the pathogenesis of cassava-associated motor system disease.

Keywords: Biomarkers, cassava, cyanate, konzo, linamarin, proteomics

Introduction

Konzo is an upper motor neuron disease characterized by a sudden onset of a non-progressive and irreversible spastic paraparesis (Tshala-Katumbay et al, 2002). The disease mainly affects children and women of childbearing age among sub-Saharan African populations that rely on the root and leaves of cassava (Manihot esculenta) as their staple food (WHO 1996). Outbreaks of konzo have been reported from several remote rural areas of the Democratic Republic of Congo, Central African Republic, Tanzania, and Mozambique (Howlett et al, 1990; Banea et al, 1992; Tylleskär et al, 1994; Cliff et al, 1997). The disease phenotype resembles that of neurolathyrism, which is caused by food dependency on the grass pea lathyrus sativus (Spencer et al, 1993).

The pathogenetic mechanisms of konzo have yet to be elucidated. Epidemiological studies consistently show an association between the occurrence of a spastic paraparesis or tetraparesis in severe cases, consumption of poorly processed bitter cassava, and low dietary intake of sulfur amino acids (SAA) needed for the rhodanese-mediated detoxification of cassava cyanogens (Howlett et al, 1990; Tylleskär et al, 1991; Banea et al, 1997; Cliff et al, 1997). Bitter cassava contains high levels of cyanogenic glucosides, mainly linamarin (α-hydroxyisobutyronitrile-β-D-glucopyranoside; Conn, 1969). Under normal conditions, ingested linamarin is converted to acetone cyanohydrin and cyanide (CN), which in turn is converted to the less acutely toxic thiocyanate (SCN) via the aforementioned SAA-dependent rhodanese pathway. CN is also converted into trace amounts of cyanate (OCN) and 2-aminothiazoline-4-carboxylic acid (ATCA). Under conditions of SAA deficiency, oxidative detoxification pathways are favored and there is increased production of OCN (Swenne et al, 1996; Tor-Agbidye et al, 1999). The identity of the neurotoxic agent(s) that trigger motor system degeneration are not known. While acetone cyanohydrin induces brain (predominantly thalamic) neurotoxicity in rodents, the reported neuropathological findings are not consistent with the marked corticospinal dysfunction observed in konzo (Tshala-Katumbay et al, 2002; Soler-Martin et al, 2009). Other potentially culpable neurotoxic candidates include CN (improbable), SCN (conceivable), ATCA (unlikely), and OCN (likely) (Spencer, 1999). OCN is an attractive candidate because repeated treatment with its sodium salt induces a motor system disease in humans, primates and rodents (Ohnishi et al, 1975; Tellez-Nagel et al, 1977; Tellez et al, 1979). NaOCN induces protein carbamoylation, a modification that can lead to protein loss of function possibly relevant to the pathogenesis of neurodegenerative diseases (Cocco et al, 1982; Nagendra et al, 1997; González et al, 1998; Kraus and Kraus, 2001).

In this study, we used state-of-the-art proteomic methodologies -- notably liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC/MS-MS), two-dimensional differential in-gel electrophoresis (2D-DIGE), and matrix assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF/MS-MS) -- to (1) test the hypothesis that protein carbamoylation occurs in sera of animals treated with linamarin while maintained on a SAA-deficient diet and (2) determine whether spinal cord proteomic modifications under a linamarin/SAA-deficient diet experimental paradigm mirror changes induced by the neurotoxic and protein-carbamoylating sodium cyanate (NaOCN). Young adult rats were put on an all amino acid (AAA)-containing control diet or a SAA-deficient diet and treated with linamarin, NaOCN, or vehicle, intraperitoneally (i.p.), for up to 2 weeks. We found that animals treated with linamarin or NaOCN, under SAA-deficient diet, developed hind limb tremors (linamarin) or severe motor weakness (NaOCN). Differential serum protein-carbamoylation was detected in sera from animals treated with linamarin/SAA-diet vs. NaOCN/AAA diet or vehicle/AA diet. MALDI-TOF/MS-MS studies of the spinal cord rat proteome revealed differential expression of proteins involved in important cellular functions such as control of thiol-redox mechanisms, endocytic vesicular trafficking, and cytoskeleton integrity.

Materials and Methods

Chemicals

Linamarin (α-hydroxyisobutyronitrile-β-D-glucopyranoside, chemical abstracts service (CAS) number 554-35-8, 98% purity) was purchased from A.G. Scientific, Inc. (San Diego, CA) and stored at -20°C. NaOCN (CAS number 917-61-3, 96% purity) was bought from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) and stored at room temperature. All other laboratory reagents were of analytical or molecular biology grades.

Animals

Young adult male heterozygous nude rats (Crl:NIH-Fox1 rnu/Fox 1+, 5-7 weeks old, n=30, weighing 145 ± 4.74 grams (mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) upon arrival) and known to have a normal phenotype (not T-cell deficient, Charles River technical data sheet 2009) were kindly donated by Professor Neuwelt, Department of Neurology, OHSU, who maintains a colony available for experimental studies as per institutional regulations on colony handling and efficient use of laboratory animals . Animals were individually caged in a room maintained on a 12-h/12-h light dark cycle. Food and water were given ad libitum.

Diet and dosing regimens

Custom-synthesized isonitrogenous rodent diet with either all amino acids (AAA diet; code TD09460) or lacking 75% of the SAA-content relative to the control diet (SAA-deficient diet; code TD09463) were purchased from Harlan (Madison, WI) and stored at 4°C until use. Previous experimental studies have shown that animals fed with SAA-free chow have significant weight loss and general weakness (Tor-Agbidye et al, 1999). Human (konzo) studies have shown drastic reduction in urinary excretion of inorganic sulfate, surrogate maker for SAA-deficiency (Banea-Mayambu et al, 1997). In our experiments, we balanced the interpretation of these aforementioned findings and chose to use a severe but not complete deficiency in SAA (i.e. 75% SAA-deficient). Rats were acclimated for a 5-day transitional period on a diet consisting of 1:1 normal rodent chow (PMI Nutrition International, NJ) and either AAA-diet (n=15) or SAA-deficient diet (n=15).

On day 6, rats were assigned to experimental groups (n=5/group) and treated i.p. (one injection per day) for up to 2 weeks as follows: 1) AAA-diet, 50-200 mg/kg body weight (bw) linamarin; 2) AAA-diet, 200 mg/kg bw NaOCN; 3) AAA diet, equivalent amount of vehicle (2 μ/gram bw saline); 4) SAA-deficient diet, 50–200 mg/kg bw linamarin; 5) SAA-deficient diet, 200 mg/kg bw NaOCN; 6) SAA-deficient diet, equivalent amount of vehicle (2 μ/gram bw saline). Subjects with konzo present with a history of chronic exposure to cyanogenic glucosides followed by a salient increase in the exposure levels during the months preceding outbreaks of the disease. Moreover, the LD50 of linamarin in rats is 300 mg/kg bw following oral treatment (Cortés et al, 1998; Link et al, 2006). Based on these findings and considering the short duration of our study, linamarin treatment consisted of 50 mg/kg bw for 4 days, a transitional increase to 100 mg/kg bw for one day, and thereafter, 200 mg/kg bw for 6 days. The dose of NaOCN was kept at 200 mg/kg bw throughout the entire study period but animals were terminated at the beginning of the second week due to severe body weight loss and motor weakness. Animals were weighed daily to assess changes in body weight and adjust the dose of the test article accordingly.

Animal observation and motor tests

Rats (n=5/experimental group) were examined daily for physical signs, including tremors and the hind limb extension reflex, which is elicited when the animal is gently raised by the tail. Motor coordination was also evaluated by their performance on an accelerating rotating rod. Briefly, animals were individually placed on rotating rods in a software-driven rotarod apparatus (AccuScan Instruments, Inc., Columbus, OH), set in an accelerating mode. The speed of rotation was gradually increased from 5 to 20 rpm. The apparatus had an automatic system for fall detection via photobeams. Animals were tested twice per week and each session consisted of 2 consecutive trials with a cutoff point of 90 seconds. The latency to fall was recorded and compared across treatment-groups.

Serum preparation and tissue processing

For proteomic studies, rats (n = 2/group) were deeply anesthetized with 4% isofluorane (1 liter oxygen/min), the blood collected via cardiac puncture and transcardially perfused with saline through the ascending aorta to remove the remaining blood. The brain and the spinal cord were dissected out, flash frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at -80°C till later MALDI-TOF/MS-MS studies. Blood obtained through cardiac puncture (1.5-3.5 ml/rat) was collected in Vacutainer tubes with no anticoagulants and kept overnight at 4°C. The serum was then collected in sterile tubes and centrifuged at 15,000 rpm for 15 min at 4°C. Serum samples were aliquoted in cryotubes and stored at -80°C till later LC-MS/MS studies.

Neuropathology studies (n=3/treatment group) including examination of the cytoarchitecture of the motor cortex and spinal cord (Nissl staining), expression of neuronal choline acetyltransferase (ChAT, immunohistochemistry for lumbar motor neurons), glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) in the aforementioned areas, and ultrastructural studies were conducted using previously described techniques (Kassa et al, 2009; Tshala-Katumbay et al, 2009). Treatment and handling of rats were done in accordance with the institutional (OHSU) guidelines for care and use of laboratory animals.

Proteomic studies

Serum LC-MS/MS

Serum samples from vehicle- or NaOCN-treated animals maintained on AAA diet and those from linamarin-treated animals maintained on SAA-deficient diet were assayed for protein content using bovine serum albumin as a standard and BCA protocol (Pierce Chemical, Rockford, IL). Twenty g portions were dissolved in 20 μl of 100 mM ammonium bicarbonate, 2 μl of 100 mM dithioerythritol added, and the sample incubated at 37°C for 30 min. Three μl of 150 mM iodoacetamide was then added, the samples incubated at room temperature for 60 min, and 10 μl of 0.1 μg/μl trypsin added (Proteomics Grade, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). Following an overnight incubation at 37°C the samples were acidified by addition of neat formic acid to produce a final 6% concentration. Ten g portions of each protein digest were analyzed by LC-MS using an Agilent 1100 series capillary LC system (Agilent Technologies Inc, Santa Clara, CA) and an LTQ linear ion trap mass spectrometer (ThermoFisher, San Jose, CA).

Electrospray ionization was performed with an ion max source fitted with a 34 gauge metal needle (ThermoFisher, cat. no. 97144-20040) and 2.7 kV source voltage. Samples were applied at 20 μL/min to a trap cartridge (Michrom BioResources, Inc, Auburn, CA), and then switched onto a 0.5 × 250 mm Zorbax SB-C18 column with 5 m particles (Agilent Technologies) using a mobile phase containing 0.1% formic acid, 7-30% acetonitrile gradient over 195 min, and 10 μL/min flow rate.

Data-dependent collection of MS/MS spectra used the dynamic exclusion feature of the instrument's control software (repeat count equal to 1, exclusion list size of 50, exclusion duration of 30 sec, and exclusion mass width of -1 to +4) to obtain MS/MS spectra of the three most abundant parent ions following each survey scan from mass to charge ratio (m/z) of 400 to 2000. The tune file was configured with no averaging of microscans, a maximum inject time of 200 msec, and AGC targets of 3 × 104 in MS mode and 1 × 104 in Msn mode. Peptides were identified by comparing the observed MS/MS spectra to theoretical MS/MS spectra of peptides generated from a protein database using the program Sequest (Version 27, rev. 12, ThermoFisher). DTA files were created with BioWorks 3.3 (ThermoFisher), and Sequest searches configured with parent ion and fragment ion mass tolerances of 2.5 Da (average) and 1.0 Da (monoisotopic), respectively. The search was also performed using a static modification of +57 on cysteines due to alkylation with idoacetamide, a differential modification of +43 on lysines to detect carbamoylation, and trypsin specificity. A rat only version of the Uniprot database (Release 15.4, Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics, Geneva, Switzerland) was used, concatenated with sequence reversed entries to independently estimate protein false discovery rates (33,134 entries). Lists of identified proteins were assembled using the program Scaffold (version 2_06_00, Proteome Software, Portland, OR). Thresholds for peptide and protein probabilities were set in Scaffold at 90% and 99%, respectively, as specified using the Peptide Prophet algorithm (Keller et al, 2002) and the Protein Prophet algorithm (Nesvizhskii et al, 2003) respectively, and requiring a minimum of 3 peptides matched to each protein entry. Sites of carbamoylation at lysine residues were also confirmed by missed trypsin cleavage at modified sites. Carbamoylation studies were conducted only on samples from vehicle- or NaOCN-treated animals maintained on AAA diet vs. those from linamarin-treated animals maintained on SAA-deficient diet, groups that were relevant to the testing of our primary hypothesis.

2D-DIGE and MALDI-TOF-MS

Flash-frozen (lumbosacral) rat spinal cord segments were shipped on dry ice to Applied Biomics (Hayward, CA) for proteomic studies. 2D-DIGE was conducted as previously described (Tshala-Katumbay et al, 2008). Samples loaded on individual gels consisted of two samples, each from animals treated with either one of the test articles (i.e. linamarin, NaOCN, or saline), in addition to one internal standard that consisted of equal protein amount (5 μg) from each treatment-group. The ratio changes in protein expression were given by in-gel and cross-gel Decyder analysis (version 6.5, GE Healthcare, NJ) with a detection limit of 0.2 ng of protein per spot. Protein spots that were consistently differentially expressed within linamarin, NaOCN or vehicle-treated groups or across these groups were picked up by the Ettan Spot Picker (GE Healthcare, NJ) and subjected to in-gel digestion with modified porcine trypsin protease (Trypsin Gold, Promega). The digested tryptic peptides were desalted by Zip-tip C18 (Millipore). Peptides were eluted from the Zip-tip with 0.5 ul of matrix solution (α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid 5 mg/ml in 50% acetonitrile, 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid, 25 mM ammonium bicarbonate) and spotted on the MALDI plate (model ABI 01-192-6-AB).

MALDI-TOF/MS and TOF/TOF tandem MS/MS were performed on an ABI 4700 mass spectrometer (Applied Biosystems, Framingham, MA). MALDI-TOF mass spectra were acquired in reflectron positive ion mode, averaging 4000 laser shots per spectrum. TOF/TOF tandem MS fragmentation spectra were acquired for each protein, averaging 4000 laser shots per fragmentation spectrum on each of the 10 most abundant ions present in each sample (excluding trypsin autolytic peptides and other known background ions).

Both the resulting peptide mass and the associated fragmentation spectra were submitted to GPS Explorer workstation equipped with MASCOT search engine (Matrix science) to search the National Center for Biotechnology Information non-redundant (NCBInr) database. Searches were performed without constraining protein molecular weight or isoelectric point, with variable carbamidomethylation of cysteine and oxidation of methionine residues, and with one missed cleavage allowed in the search parameters. Candidates with confidence scores greater than 95% for protein identification were considered significantly dysregulated.

Statistical analysis

Body weight and latency to fall from the rotarod were analyzed by analysis of variance using Proc Mixed of SAS 9.22 (2009). A split plot design model was used, and the main effects (treatment, diet, rotarod trial, and animal nested within treatment and diet) and all possible interactions were included. The effect of animal within treatment and diet and the residual were considered random effects. Treatment, diet, rotarod trial, and its interactions were considered fixed effects. Preplanned contrasts were used to separate treatment effect into individual degree of freedom contrast. All statistical analyses we conducted at the significance level of p < 0.05.

Results

Body weight, motor assessment and neuropathology

Animals on AAA diet had significantly higher body weight over time compared to those on SAA-deficient diet regardless the treatment (p<0.001). By the beginning of the second week, NaOCN-treated animals that lost more than 20 % of their initial body weight were terminated for biochemical and/or pathological studies.

Qualitative assessment for motor abnormalities revealed hind limb tremors in two linamarin/SAA-treated rats over the last two days of treatment. Rats treated with NaOCN developed a hunched-back posture and dragged their hind limbs after two days of treatment. Those on SAA-deficient diet appeared to be more affected than those on normal AAA diet. Moreover, the extension reflex was abolished in most of these animals. Quantitative analysis of rotarod performance showed that treatment but not diet had a significant effect on motor coordination. NaOCN-treated animals spent significantly less time (mean latency to fall per treatment group ± SEM) on the rotarod when compared to animals treated with linamarin or vehicle (17 ± 3.9 vs. 36.3 ± 3.8 and 39.2 ± 3.8 seconds, respectively, p < 0.01). No significant difference in the time spent on the rotarod was found when comparing linamarin- to vehicle-treated animals.

Nissl staining of the motor cortex and the lumbar spinal cord, GFAP immunostaining in the motor cortex, ChAT and GFAP immunostaining in the lumbar spinal cord, as well as ultrastructural (electron microscopy) studies on the cervical spinal cord and proximal segments of sciatic nerves were unremarkable.

Proteomic changes

Serum proteomics

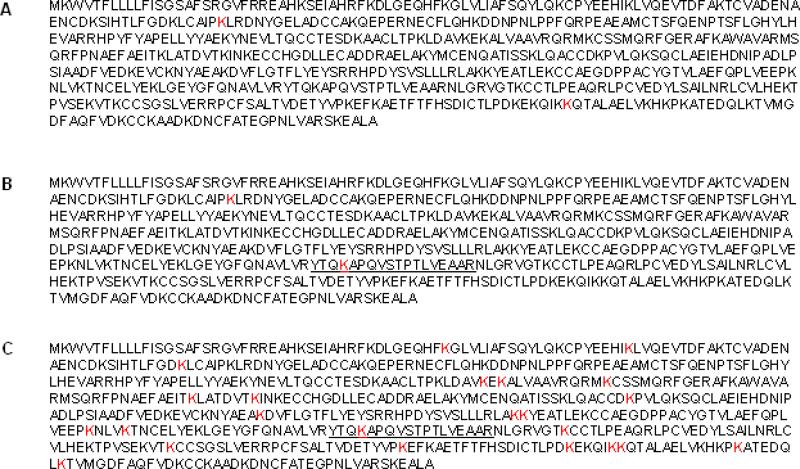

We used LC-MS/MS to search for carbamoylation on albumin, the most abundant serum protein, in samples from animals treated with vehicle under normal AAA diet vs. linamarin under SAA diet or NaOCN under normal AAA diet. Samples from animals treated with vehicle yielded two peptides carbamoylated at lysine residues 103 and 549. Peptides (89-105 and 435-452) carbamolylated at lysine residues 103 and 438 were found in samples from animals treated with linamarin/SAA-deficient diet. Carbamolyated peptide 435-452 was not detected in samples from animals treated with vehicle. However, it was detected in samples from animals treated with NaOCN/AAA-normal diet in which a total of 23 carbamolylation sites were found. (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

(A) Highlighted sites of carbamoylation (lysine residues 103 and 549) on serum albumin in animals treated with vehicle. (B) Highlighted sites of carbamoylation (lysine residues 103 and 438) on serum albumin in linamarin-treated animals. Peptide 435-452 (underlined) was also found carbamoylated in animals treated with NaOCN but not vehicle. (C) Serum albumin sequence with 23 highlighted lysine (K) carbamoylated residues and underlined peptide 435-452 (also found in linamarin-treated animals), in animals treated with NaOCN.

Spinal cord proteomics

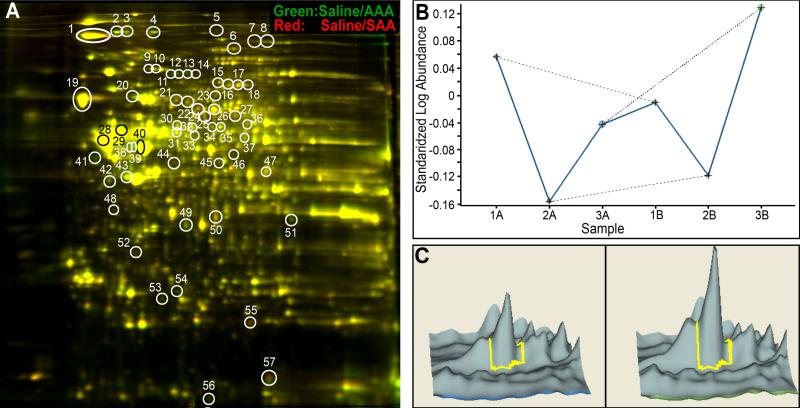

MALDI-TOF/MS-MS studies revealed differential expression of proteins in animals maintained on SAA-deficient diet relative to those on normal AAA diet and treated with either vehicle, or linamarin, or OCN. In-gel and cross-gel Decyder analysis of protein expression revealed up to 59 protein spots differentially regulated (with a minimum of 1.3 fold change for any pair-wise comparison) across all the treatment groups. Interestingly, SAA-deficient diet impacted the overall expression of proteins by itself (Figure 2) and in combination with linamarin or NaOCN treatment (Table 1). Mass spectrometry analysis was conducted on only 33 protein spots that were consistently modified across the linamarin/SAA and NaOCN/AAA-treatment conditions, the most relevant pair comparison in order to determine whether proteomic changes induced by linamarin under SAA-deficiency diet were similar to those induced by NaOCN under normal AAA diet. In general, both linamarin under SAA-deficiency and NaOCN under normal diet altered the expression of proteins involved in maintaining the integrity of the cytoskeleton (e.g. α2-spectrin and light and medium weight neurofilament subunits), in controlling redox and protein folding mechanisms (e.g. protein disulfide isomerase, PDI) and controlling vesicular trafficking (e.g. dynamin 1), and regulating oxidative mechanisms (e.g. peroxiredoxin 6) (Table 1).

Figure 2.

(A) Representative 2D-DIGE images displaying differential expression of lumbosacral proteins from animals treated with vehicle (saline) while maintained on normal AAA diet versus 75% SAA-deficient diet. Green spot (e.g. spot # 2): higher protein abundance in saline/AAA-treated samples; red spot (e.g. spot # 44): higher abundance of respective protein in saline/SAA-treated animals; yellow spot (e.g. spot # 19): no differential change of respective protein abundance in saline-treated animals fed normal AAA versus 75% SAA-deficient diet. Protein names of spots are given in Table 1. Differential migration of proteins e.g. spots 11-14 identified as dynamin 1 indicates that posttranslational modifications occur in our model. (B) Graph depicting relative abundance of a selected protein, i.e., N-ethylmaleimide sensitive fusion protein (isoform CRA_a, NSF) in samples from animals treated with either one of the 6 treatment conditions (1= linamarin, 2= NaOCN, 3= vehicle; A= normal AAA diet and B= 75% SAA-deficient diet). Differential protein abundance of NSF in the pair comparison 1A versus 1B, or 2A versus 2B, or 3A versus 3B demonstrates the impact of diet on protein expression for each treatment condition. (C) Decyder output showing differential abundance of NSF in 3A (left, vehicle/AAA) versus 3B (right, vehicle/SAA) protein samples.

Table 1.

List of proteins differentially expressed following administration of linamarin, or NaOCN, or vehicle in animals maintained on either normal AAA or SAA-deficient diet (LIN = linamarin).

| Peptide count | Protein score | Total ion score | AAA vs. SAA | LIN vs. Vehicle |

NaOCN vs. vehicle |

Functional category | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AAA | SAA | AAA | SAA | |||||||

| 1 | neurofilament, medium polypeptide | 25 | 509 | 264 | -1.34 | -1.74 | -3.16 | -1.25 | -1.56 | Structural protein/protein binding |

| 2 | alpha-spectrin 2 | 46 | 280 | 39 | +1.43 | +1.36 | +2.15 | +1.20 | +1.87 | Structural protein/protein binding |

| 4 | spna2 protein | 41 | 327 | 81 | +1.43 | +1.30 | +2.16 | +1.13 | +1.59 | Structural protein/protein binding |

| 8 | ATP citrate lyase isoform 2 | 12 | 86 | 14 | +1.16 | -1.24 | -1.31 | -1.59 | +1.01 | Fatty acid biosynthesis |

| 10 | Gelsolin1 | 22 | 386 | 176 | +1.26 | -1.06 | -1.13 | -1.10 | +1.28 | Structural protein/protein binding/apoptosis regulator |

| 11 | dynamin 12,3 | 16 | 138 | 24 | +3.31 | +1.97 | +8.15 | +1.25 | +3.30 | Endocytic vesicle trafficking |

| 12 | dynamin 1 | 17 | 180 | 49 | +2.06 | +1.70 | +4.29 | +1.09 | +2.01 | |

| 13 | dynamin 1 | 23 | 266 | 80 | +1.99 | +2.03 | +4.95 | +1.21 | +2.11 | |

| 14 | dynamin 1 | 21 | 198 | 46 | +1.72 | +1.91 | +4.19 | +1.16 | +1.69 | |

| 15 | radixin | 21 | 316 | 137 | -1.14 | +1.05 | -1.48 | -1.54 | -1.51 | Structural protein/protein binding |

| 16 | N-ethylmaleimide sensitive fusion protein | 18 | 210 | 63 | -1.05 | +1.14 | -1.24 | +1.26 | +1.38 | Intracellular membrane fusion protein |

| 17 | N-ethylmaleimide sensitive fusion protein | 33 | 430 | 117 | -1.48 | +1.26 | -1.38 | -1.30 | -1.76 | |

| 18 | N-ethylmaleimide sensitive fusion protein | 23 | 312 | 99 | -1.54 | +1.13 | -1.54 | -1.04 | -1.70 | |

| 19 | neurofilament, light polypeptide | 29 | 489 | 156 | -1.24 | -1.76 | -2.97 | -1.14 | -1.58 | Structural protein/protein binding |

| 20 | heat shock protein 82 | 26 | 535 | 261 | +1.39 | -1.14 | +1.10 | +2.29 | +3.39 | Protein folding/thermotolerance |

| 21 | dihydropyrimidinase-like 2 | 13 | 215 | 71 | -1.40 | -1.96 | -2.88 | -1.06 | -1.46 | Axonal growth and path finding |

| 23 | heat shock protein 8 | 10 | 83 | 18 | +1.15 | -1.12 | -1.37 | -1.63 | -1.61 | Protein folding/thermotolerance |

| 25 | dihydropyrimidinase-like 2 | 22 | 311 | 110 | +1.05 | -1.79 | -1.47 | -1.08 | -1.60 | Axonal growth and path finding |

| 26 | dihydropyrimidinase-like 2 | 29 | 560 | 214 | -1.41 | -1.87 | -2.66 | -2.70 | -2.48 | |

| 28 | tubulin T beta 15 | 17 | 292 | 101 | +1.07 | -1.45 | -2.09 | -1.51 | -1.33 | Structural protein/axonal transport |

| 30 | protein disulfide isomerase associated 33 | 18 | 260 | 111 | +1.18 | +1.30 | -1.02 | -1.79 | -1.47 | Redox mechanisms/protein folding |

| 32 | protein disulfide isomerase associated 33 | 19 | 225 | 65 | -1.02 | -1.64 | +1.34 | -1.06 | -1.10 | |

| 34 | syntaxin binding protein 1 | 22 | 378 | 197 | +1.34 | +1.07 | +1.84 | +2.03 | +1.91 | Synaptic vesicle trafficking |

| 38 | glial fibrillary acidic protein delta | 30 | 471 | 151 | +2.78 | +2.43 | +4.76 | -1.48 | +2.82 | Structrual protein |

| 40 | glial fibrillary acidic protein delta | 38 | 751 | 231 | +1.42 | -1.62 | -1.41 | -1.53 | +1.16 | |

| 41 | neurofilament, light polypeptide | 23 | 321 | 87 | +2.11 | +1.33 | +3.31 | +1.29 | +2.81 | Structural protein/protein binding |

| 43 | predicted similar to Actin | 18 | 551 | 355 | +1.48 | -1.13 | +1.22 | +1.31 | +2.15 | Structural protein/internal cell motility |

| 44 | actin-related protein 3 homolog | 13 | 273 | 149 | -1.71 | +1.79 | +1.16 | +1.36 | +1.05 | Structural protein |

| 47 | pyruvate dehydrogenase E1 alpha form 1 subunit | 18 | 326 | 173 | -1.03 | +1.45 | +1.44 | +1.20 | -1.13 | Energy metabolism |

| 53 | peroxiredoxin 6 | 15 | 617 | 429 | +1.31 | -1.21 | +1.15 | +1.90 | +2.31 | Redox mechanisms |

Negative and positive signs indicate lower or higher abundance of protein showing effect of diet (vehicle/AAA vs. vehicle/SAA), or effect of treatment (LIN/AAA vs. vehicle/AAA, LIN/SAA vs. vehicle/SAA, NaOCN/AAA vs. vehicle/AAA, or NaOCN/SAA vs. vehicle/SAA).

Gelsolin showed significant dysregulation (-1.34) in the pair-comparison LIN/AAA vs. LIN/SAA (not shown in table) indicating interaction between diet and linamarin treatment.

Examples of proteins with relative abundance heavily impacted by the type of diet.

Examples of proteins with differential migration pattern on 2D-DIGE suggesting that protein posttranslational modifications may play important roles in our model.

Differential 2D-DIGE migration of selected proteins such as dynamin 1, PDI, and light weight neurofilament subunit are indicative of changes in their respective isoelectric points and/or molecular masses (Figure 2A and Table 1). This finding suggests that protein posttranslational modifications occur in our model.

Discussion

Our study demonstrates for the first time that linamarin, the main cassava cyanogenic glucoside, and NaOCN induce a qualitatively similar pattern of spinal cord proteomic modifications in vivo. Whether these modifications are attributable to a mechanism commonly associated with both cyanide (linamarin metabolite) and cyanate (NaOCN) intoxications has yet to be determined. The observed difference in the extent and (LC/MS-MS) pattern of albumin carbamoylation between animals treated with NaOCN vs. linamarin under SAA-deficient diet may be possibly explained by the fact that cyanate production did not significantly occur in the latter group of animals. This interpretation is consistent with a previous proposal that suggests that the gut flora is needed for linamarin breakdown and hence, for cyanide and/or cyanate intoxication (under SAA-deficiency) to occur. It is possible oral administration of linamarin under dietary SAA-deficiency would lead to an increased production of cyanate (Tylleskär et al., 1991; Swenne et al., 1996; Tor-Agbidye et al., 1999). Human studies are therefore needed to explore whether serum levels of linamarin as well as those of cyanate and carbamoylated proteins correlate with increased risk for konzo among cassava-reliant populations.

Physical signs associated with linamarin intoxication were minor and consisted of hind limb tremors mostly observed in animals under SAA-deficient diet. NaOCN-treated animals present with more severe signs consisting of both hind limb weakness and gait abnormalities regardless of the type of diet. A previous study has found motor abnormalities in young rats kept on a cassava-containing diet for 1 year (Mathangi et al, 1999). Whether these abnormalities could be attributed to linamarin vs. the protein-deficient diet was not addressed. NaOCN-motor system toxicity is consistent with previous studies that showed motor weakness and peripheral neuropathy in rats treated with NaOCN (Tellez-Nagel et al, 1977). Treatment with the same agent led to a central demyelinating lesion involving the pyramidal tract in the spinal cord of non-human primates (Maccaca nemestrina) (Tellez et al, 1979) and peripheral axonopathy in patients under NaOCN therapy for sickle cell disease (Ohnishi et al, 1975). The predominantly myelinotoxic effect of OCN (Tellez-Nagel et al, 1977; Tellez et al, 1979) has been attributed to a selective modification of myelin proteins by carbamoylation (Tellez et al, 1979). OCN carbamoylates proteins at amino and/or sulfhydryl sites leading to a modification that may induce changes in protein structure and function (Farías et al, 1993; González et al, 1998; Kraus and Kraus, 2001). Despite severe motor weakness and gait abnormalities, our neuropathological findings were unremarkable probably because of the short duration of our study not enough for structural changes to develop.

Our spinal cord proteomic (MALDI-TOF/MS-MS) analysis revealed similar qualitative trends in modifications induced by either linamarin or NaOCN, modifications of which the magnitude appeared to be aggravated under SAA-deficient diet. Treatment with linamarin or NaOCN altered the abundance of proteins involved in vesicular trafficking, redox mechanisms, protein folding, and maintenance of the cytoskeleton integrity. Whether the observed spinal cord modifications are associated with a motor system toxicity has to be explored. These findings, however, offer opportunities for new lines of investigations in the pathogenesis of konzo and/or cyanate neurotoxicity. In-depth proteomic studies are also needed to determine whether carbamoylation of spinal cord proteins occurs in animals under linamarin/SAA- or OCN-treatment as well as to understand its pathogenetic significance in relation to motor system disease. Such studies may be conducted on proteins that are differentially expressed in our model or on other sentinel proteins such as superoxide dismutase (SOD) 1, whose enzymatic function is known to be impaired by carbamoylation (Cocco et al, 1983).

We also found a remarkable influence of the SAA-deficient diet on linamarin- and NaOCN-associated proteomic modifications. This finding underscores the role of diet in susceptibility to toxicant-induced diseases and particularly, those associated with cyanogenic intoxication. Whether the bidirectional pattern associated with our proteomic modifications e.g. increase in the relative abundance of proteins involved in thiol-redox mechanisms (peroxiredoxin 6) vs. decrease in the abundance of most structural proteins (e.g. neurofilament light chain) is reflective of adaptive or pathological responses to our test articles is not known and needs to be explored. More importantly, the role of the differentially expressed proteins needs to be explored in relation to neurodegenerative mechanisms. For example, the GTPase activity of neuron-specific dynamin 1 (Lou et al, 2008) is essential for synaptic vesicle fission during clathrin-mediated endocytosis in nerve terminals (Clayton and Cousin, 2009). Dynamin 1 was shown to inhibit phosphatidylinositol 3 kinase (PI3K) ex vivo (Findik et al, 2001), a survival signalling molecule acting via Akt to inhibit several proapoptotic substrates such as BAD, caspase 9, and glycogen synthase kinase β (Wong et al, 2005). Interestingly, decreased levels of phosphorylated Akt have been found in motor neurons from sporadic and familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), and also in the murine familial ALS model (SOD1G93A mice) prior to the onset of symptoms (Dewil et al, 2007). Thus, increased expression of dynamin 1 leading to inhibition of PI3K/Akt and thus, impairment of cell survival mechanisms may play a role in the pathogenesis of linamarin/SAA and NaOCN-induced neurotoxicity. Increased abundance of dynamin 1 in the brains of old mice has been attributed a similar detrimental role in the process of aging (Poon et al, 2006). Interestingly, mutations in the gene coding for a dynamin 1 isomer, dynamin 2, are associated with a demyelinating and axonal neuropathy in Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease (Niemann et al, 2006). Thus, changes in the protein expression of dynamin 1 possibly including its posttranslational modification may be relevant to the toxicity of linamarin and/or NaOCN.

Peroxiredoxin 6 is an anti-oxidant enzyme which protects from reactive oxygen species-mediated deoxyribonucleic acid fragmentation (Fatma et al, 2001). Aberrant expression of peroxiredoxin subtypes has been reported in neurodegenerative disorders. 2D-DIGE coupled to MALDI-MS showed increased protein levels of peroxiredoxin 6 in the frontal cortex of postmortem tissue from subjects with Pick's disease, one of the causes of frontotemporal lobar degeneration (Krapfenbauer et al, 2003). Increased expression of peroxiredoxin 6 was also documented in spinal cord tissue from paralyzed SOD1G93A mice (Strey et al, 2004) and implicated in neuroprotection through a reduction in the accumulation of stress-induced reactive oxygen species (Strey et al, 2004; Boukhtouche et al, 2006). Thus, the increased abundance of peroxiredoxin 6 in linamarin/SAA- and NaOCN/AAA-treated animals may represent a neuroprotective response to modifications induced by our test articles.

PDI catalyzes thiol/disulfide exchange reactions and plays a major role in the correct folding of proteins (Turano et al, 2002; Wilkinson and Gilbert, 2004). PDI is one of the most abundant proteins in the endoplasmic reticulum, an important organelle for posttranslational modification. Endoplasmic reticulum stress is a feature of neurodegenerative diseases such as ALS, Parkinson's disease and Alzheimer's disease (Atkin et al, 2008; Saxena et al, 2009; Scheper and Hoozemans, 2009). Overexpression of PDI reduced mutant SOD1-mediated toxicity in transfected motor neuron like NSC-34 cell lines (Walker et al, 2009). Upregulation of PDI was found in the cerebrospinal fluid and spinal cord tissue of subjects with sporadic ALS and SOD1G93A rats (Atkin et al, 2008). However, the enzyme was found to be S-nitrosylated and functionally inactive in the spinal cord tissue of subjects with sporadic ALS and SOD1G93A mice (Walker et al, 2009). S-nitrosylation of cysteine residues that mediate the activity of PDI was also found in the brains of subjects with sporadic Parkinson's and Alzheimer's disease (Uehara et al, 2006). In our study, we found a dysregulation and differential 2D-DIGE migration of PDI suggesting a potential role of this enzyme, and possibly its posttranslational modification, in the pathogenesis of linamarin or NaOCN-toxicity.

Our study does not exclude other potential mechanisms in the pathogenesis of cassava-related neurological diseases. For instance, the neurotoxic potential of SCN, an experimentally known AMPA chaotropic agent, i.e., a possible mediator of excitotoxicity, still needs to be explored (Spencer, 1999). Taken together, our findings suggest that the pathogenesis of konzo may involve pathological protein posttranslational modifications possibly including carbamoylation and/or dysregulation of cellular functions involved in thiol-redox mechanisms, endocytic vesicular trafficking, and cytoskeleton integrity. However, this proposal can be effectively addressed only in an animal model of konzo in which unequivocal degeneration of the central motor pathway has been demonstrated.

Acknowledgement

These studies were supported by NIEHS grant R21ES017225, NINDS grant K01NS052183, and core grants 5P30CA069533, 5P30EY010572, P30NS061800 from National Institutes of Health (Bethesda, MD). The technical expertise of Dan Austin and scientific advice from Dr Peter Spencer, OHSU, are highly appreciated.

Abbrevations

- AAA

all amino acid

- ALS

amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

- ATCA

2-aminothiazoline-4-carboxylic acid

- bw

body weight

- CAS

chemical abstracts service

- ChAT

choline acetyltransferase

- 2DDIGE

two-dimensional differential in-gel electrophoresis

- GFAP

glial fibrillary acidic protein

- i.p.

intraperitoneally

- LC

liquid chromatography

- MALDI-TOF/MS-MS

matrix assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight/tandem mass spectrometry

- PDI

protein disulfide isomerase

- PI3K

phosphatidylinositol 3 kinase

- SAA

sulfur amino acid

- SEM

standard error of the mean

- SOD

superoxide dismutase

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Atkin JD, Farg MA, Walker AK, McLean C, Tomas D, Horne MK. Endoplasmic reticulum stress and induction of the unfolded protein response in human sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurobiol. Dis. 2008;30:400–407. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2008.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banea M, Bikangi N, Tylleskär T, Rosling H. Haute prevalence de konzo associée à une crise agro-alimentaire dans la région de Bandundu au Zaïre. Annales de la Société Belge de Médecine Tropicale. 1992;72:295–309. (English translation appears in: Banea, M., 1997. Dietary exposure to cyanogens from cassava. A challenge for prevention in Zaire. Doctoral thesis. Uppsala University.)

- Banea-Mayambu JP, Tylleskär T, Gitebo N, Matadi N, Gebre-Medhi M, Rosling H. Geographical and seasonal association between linamarin and cyanide exposure from cassava and the upper motor neuron disease konzo in former Zaire. Trop. Med. Int. Health. 1997;2:1143–1151. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.1997.d01-215.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boukhtouche F, Vodjdani G, Jarvis CI, Bakouche J, Staels B, Mallet J, Mariani J, Lemaigre-Dubreuil Y, Brugg B. Human retinoic acid receptor-related orphan receptor 1 overexpression protects neurones against oxidative stress-induced apoptosis. J. Neurochem. 2006;96:1778–1789. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.03708.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clayton EL, Cousin MA. The molecular physiology of activity-dependent bulk endocytosis of synaptic vesicles. J. Neurochem. 2009;111:901–914. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06384.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cliff J, Nicala D, Saute F, Givragy R, Azambuja G, Taela A, Chavane L, Howarth J. Konzo associated with war in Mozambique. Trop. Med. Int. Health. 1997;2:1068–1074. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.1997.d01-178.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cocco D, Rossi L, Barra D, Bossa F, Rotilio G. Carbamoylation of Cu, Zn superoxide dismutase by cyanate. Role of lysines in the enzyme action. FEBS Lett. 1982;150:303–306. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(82)80756-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cocco D, Mavelli I, Rossi L, Rotilio G. Reduced anion binding and anion inhibition in Cu, Zn superoxide dismutase chemically modified at lysines without alteration of the rhombic distortion of the copper site. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1983;111:860–864. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(83)91378-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conn EE. Cyanogenic glycosides. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1969;17:519–526. [Google Scholar]

- Cortés ML, de Felipe P, Martin V, Hughes MA, Izquierdo M. Successful use of a plant gene in the treatment of cancer in vivo. Gene Ther. 1998;5:1499–1507. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3300751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewil M, Lambrechts D, Sciot R, Shaw PJ, Ince PG, Robberecht W, Van Den Bosch L. Vascular endothelial growth factor counteracts the loss of phospho-Akt preceding motor neurone degeneration in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol. 2007;33:499–509. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.2007.00850.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farías GA, Vial C, Maccioni RB. Functional domains on chemically modified tau protein. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 1993;13:173–182. doi: 10.1007/BF00735373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fatma N, Singh DP, Shinohara T, Chylack LT., Jr. Transcriptional regulation of the antioxidant protein 2 gene, a thiol-specific antioxidant, by lens epithelium-derived growth factor to protect cells from oxidative stress. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:48899–48907. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100733200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Findik DH, Misra S, Jain SK, Keeler ML, Powell KA, Malladi CS, Varticovski L, Robinson PJ. Dynamin inhibits phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase in hematopoietic cells. Biochem. Biophys. Acta. 2001;1538:10–19. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4889(00)00130-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González C, Farías G, Maccioni RB. Modifications of tau to an Alzheimer's type protein interferes with its interaction with microtubules. Cell Mol. Biol. (Noisy-le-grand) 1998;44:1117–1127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howlett WP, Brubaker GR, Mlingi N, Rosling H. Konzo, an epidemic upper motor neuron disease studied in Tanzania. Brain. 1990;113:223–235. doi: 10.1093/brain/113.1.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kassa RM, Mariotti R, Bonaconsa M, Bertini G, Bentivoglio M. Gene, cell, and axon changes in the familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis mouse sensorimotor cortex. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2009;68:59–72. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e3181922572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller A, Nesvizhskii AI, Kolker E, Aebersold R. Empirical statistical model to estimate the accuracy of peptide identifications made by MS/MS and database search. Anal. Chem. 2002;15:5383–5392. doi: 10.1021/ac025747h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krapfenbauer K, Engidawork E, Cairns N, Fountoulakis M, Lubec G. Aberrant expression of peroxiredoxin subtypes in neurodegenerative disorders. Brain Res. 2003;967:152–160. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)04243-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraus LM, Kraus AP., Jr. Carbamoylation of amino acids and proteins in uremia. Kidney Int. Suppl. 2001;78:S102–107. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.59780102.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Link N, Aubel C, Kelm JM, Marty RR, Greber D, Djonov V, Bourhis J, Weber W, Fussenegger M. Therapeutic protein transduction of mammalian cells and mice by nucleic acid-free lentiviral nanoparticles. Nucleic acids Res. 2006;34:e16. doi: 10.1093/nar/gnj014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lou X, Paradise S, Ferguson SM, De Camilli P. Selective saturation of slow endocytosis at a giant glutamatergic central synapse lacking dynamin 1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:17555–17560. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809621105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathangi DC, Mohan V, Namasivayam A. Effect of cassava on motor co-ordination and neurotransmitter level in the Albino rat. Food Chem. Toxicol. 1999;37:57–60. doi: 10.1016/s0278-6915(98)00099-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagendra SN, Faiman MD, Davis K, Wu JY, Newby X, Schloss JV. Carbamoylation of brain glutamate receptors by a disulfiram metabolite. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:24247–24251. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.39.24247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nesvizhskii AI, Keller A, Kolker E, Aebersold R. A statistical model for identifying proteins by tandem mass spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 2003;75:4646–4658. doi: 10.1021/ac0341261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niemann A, Berger P, Suter U. Pathomechanisms of mutant proteins in Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease. Neuromolecular Med. 2006;8:217–242. doi: 10.1385/nmm:8:1-2:217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohnishi A, Peterson CM, Dyck PJ. Axonal degeneration in sodium cyanate-induced neuropathy. Arch. Neurol. 1975;32:530–534. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1975.00490500050005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poon HF, Vaishnav RA, Getchell TV, Getchell ML, Butterfield DA. Quantitative proteomics analysis of differential protein expression and oxidative modification of specific proteins in the brains of old mice. Neurobiol. Aging. 2006;27:1010–1019. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2005.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxena S, Cabuy E, Caroni P. A role for motoneuron subtype-selective ER stress in disease manifestations of FALS mice. Nat. Neurosci. 2009;12:627–636. doi: 10.1038/nn.2297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheper W, Hoozemans JJ. Endoplasmic reticulum protein quality control in neurodegenerative disease: the good, the bad and the therapy. Curr. Med. Chem. 2009;16:615–626. doi: 10.2174/092986709787458506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soler-Martin C, Riera J, Seoane A, Cutillas B, Ambrosio S, Boadas-Vaello P, Llorens J. The targets of acetone cyanohydrin neurotoxicity in the rat are not the ones expected in an animal model of konzo. Neurotoxicol. Teratol. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2009.11.001. doi:10.1016/j.ntt.2009.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer PS, Ludolph AC, Kisby GE. Neurologic diseases associated with use of plant components with toxic potential. Environ. Res. 1993;62:106–113. doi: 10.1006/enrs.1993.1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer PS. Food toxins, AMPA receptors, and motor neuron diseases. Drug Metab. Rev. 1999;31:561–587. doi: 10.1081/dmr-100101936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strey CW, Spellman D, Stieber A, Gonatas JO, Wang X, Lambris JD, Gonatas NK. Dysregulation of stathmin, a microtubule-destabilizing protein, and up-regulation of Hsp 25, Hsp27, and the antioxidant peroxiredoxin 6 in a mouse model of familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Am. J. Pathol. 2004;165:1701–1718. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63426-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swenne I, Eriksson UJ, Christoffersson R, Kagedal B, Lundquist P, Nilsson L, Tylleskär T, Rosling H. Cyanide detoxification in rats exposed to acetonitrile and fed a low protein diet. Fundam. Appl. Toxicol. 1996;32:66–71. doi: 10.1006/faat.1996.0107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tellez-Nagel I, Korthals JK, Vlassara HV, Cerami A. An ultrastructural study of chronic sodium cyanate-induced neuropathy. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 1977;36:352–363. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tellez I, Johnson D, Nagel RL, Cerami A. Neurotoxicity of sodium cyanate. Acta Neuropathol. 1979;47:75–79. doi: 10.1007/BF00698277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tor-Agbidye J, Palmer VS, Lasarev MR, Craig AM, Blythe LL, Sabri MI, Spencer PS. Bioactivation of cyanide to cyanate in sulfur amino acid deficiency: relevance to neurological disease in humans subsisting on cassava. Toxicol. Sci. 1999;50:228–235. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/50.2.228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tshala-Katumbay D, Eeg-Olofsson KE, Kazadi-Kayembe T, Tylleskär T, Fällmar P. Analysis of motor pathway involvement in konzo using transcranial electrical and magnetic stimulation. Muscle Nerve. 2002;25:230–235. doi: 10.1002/mus.10029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tshala-Katumbay D, Monterroso V, Kayton R, Lasarev M, Sabri M, Spencer P. Probing mechanisms of axonopathy. Part I: Protein targets of 1,2-diacetylbenzene, the neurotoxic metabolite of aromatic solvent 1,2-diethylbenzene. Toxicol. Sci. 2008;105:134–141. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfn103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tshala-Katumbay D, Desjardins P, Sabri M, Butterworth R, Spencer P. New insights into mechansims of γ-diketone-induced axonopathy. Neurochem. Res. 2009;34:1919–1923. doi: 10.1007/s11064-009-9977-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turano C, Coppari S, Altieri F, Ferraro A. Proteins of the PDI family: unpredicted non-ER locations and functions. J. Cell Physiol. 2002;193:154–163. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tylleskär T, Banea M, Bikangi N, Fresco L, Persson LA, Rosling H. Epidemiological evidence from Zaire for a dietary etiology of konzo, an upper motor neuron disease. Bull. World Health Organ. 1991;69:581–589. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tylleskär T, Légué FD, Peterson S, Kpizingui E, Stecker P. Konzo in the Central African Republic. Neurology. 1994;44:959–961. doi: 10.1212/wnl.44.5.959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uehara T, Nakamura T, Yao D, Shi ZQ, Gu Z, Ma Y, Masliah E, Nomura Y, Lipton SA. S-nitrosylated protein-disulphide isomerase links protein misfolding to neurodegeneration. Nature. 2006;441:513–517. doi: 10.1038/nature04782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker AK, Farg MA, Bye CR, McLean CA, Horne MK, Atkin JD. Protein disulfide isomerase protects against protein aggregation and is S-nitrosylated in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Brain. 2009 doi: 10.1093/brain/awp267. doi:10.1093/brain/awp267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO Konzo, a distinct type of upper motor neuron disease. Wkly. Epidemiol. Rec. 1996;71:225–232. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson B, Gilbert HF. Protein disulfide isomerase. Biochem. Biophys. Acta. 2004;1699:35–44. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2004.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong WR, Chen YY, Yang SM, Chen YL, Horng JT. Phosphorylation of PI3/Akt and MAPK/ERK in an early entry step of enterovirus 71. Life Sci. 2005;78:82–90. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2005.04.076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]