Abstract

In mouse olfactory epithelium (OE), pituitary adenylate cyclase activating peptide (PACAP) protects against axotomy-induced apoptosis. We used mouse OE to determine whether PACAP protects neurons during exposure to the inflammatory cytokine TNFα. Live slices of neonatal mouse OE were treated with 40 ng/ml TNFα ± 40 nM PACAP for 6 hours and dying cells were live-labeled with 0.5% propidium iodide. TNFα significantly increased the percentage of dying cells while co-incubation with PACAP prevented cell death. PACAP also prevented TNFα-mediated cell death in the olfactory placodal (OP) cell lines, OP6 and OP27. Although OP cell lines express all three PACAP receptors (PAC1, VPAC1,VPAC2), PACAP’s protection of these cells from TNFα was mimicked by the specific PAC1 receptor agonist maxadilan and abolished by the PAC1 antagonist PACAP6–38. Treatment of OP cell lines with blockers or activators of the PLC and AC/MAPKK pathways revealed that PACAP-mediated protection from TNFα involved both pathways. PACAP may therefore function through PAC1 receptors to protect neurons from cell death during inflammatory cytokine release in vivo as would occur upon viral infection or allergic rhinitis-associated injury.

Introduction

During CNS injury, microglia become activated and release cytokines such as TNFα and IL1β (Clausen et al., 2008). Cytokines then cause a series of inflammatory responses in the tissue that are often detrimental, and can result in exacerbation of the original injury. Several studies have documented the ability of pituitary adenylate cyclase activating polypeptide (PACAP) to reduce expression and release of TNFα and other cytokines following lipopolysaccharide stimulation of microglial cell lines (Kim et al., 2000) or purified macrophage cultures (Delgado. et al., 2003b). PACAP belongs to the vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP)-secretin-glucagon superfamily of peptides (Kieffer & Habener, 1999) and acts through G-protein coupled PAC1, VPAC1 and VPAC2 receptors to increase cAMP and reduce TNFα expression in microglia (Kim et al., 2000). We used the murine olfactory epithelium (OE) as a model to analyze the effect of PACAP administration during cytokine release. Unlike in the CNS, the neurons of the OE are directly exposed to the external environment and are continually damaged by airborne toxins and xenobiotics. In response to the continual damage, the OE is able to regenerate and does so throughout adulthood (Graziadei & Graziadei, 1979). Both TNFα and TNFα receptors (TNFR1 and TNFR2) are expressed in the OE (Farbman et al., 1999) and TNFα can induce apoptosis in explants of the embryonic OE (Suzuki & Farbman, 2000). TNFR2 activates pro-survival signaling pathways, while TNFR1 contains a cytoplasmic death domain which allows recruitment of several death domain and other proteins which can then activate caspases and induce apoptosis (McCoy & Tansey, 2008).

PACAP is expressed in the OE (Hegg et al., 2003a; Hansel et al., 2001) and protects against axotomy-induced apoptosis of neonatal rat olfactory sensory neurons (OSNs) in primary cultures (Hansel et al., 2001). In addition, PACAP protects against axotomy-induced apoptosis of adult mouse OSNs via a phospholipase C (PLC) and calcium-dependent reduction in A-type potassium channels (Han & Lucero, 2005). While axotomy is a well-characterized model for study of olfactory neurodegeneration, it differs considerably from apoptosis induced by direct damage to the OE. Studies using cytokine-induced apoptosis more closely mimic an inflammatory response to direct damage to the OE and are likely to yield more physiologically-relevant information.

In this study, we therefore used a live slice model of the OE (Hegg et al., 2003a) to demonstrate that PACAP can protect against cytokine-induced cell death. As this model does not distinguish between effects of PACAP on neurons or immune cells, the majority of our study involved using two olfactory placodal (OP) cell lines to examine the effects of PACAP on neuronal cells in the absence of immune cells. OP6 and OP27 are olfactory neuronal precursor cell lines clonally derived from the olfactory placode of embryonic mice (Illing et al., 2002). These cell lines are well-characterized and shown to be a good model to study both immature and mature olfactory neuron function. OP27 cells contain the expression profile of immediate neuronal precursors (INPs) while OP6 cells express markers of immature receptor neurons (IRNs) (Illing et al., 2002). When placed in differentiating conditions, both OP cell lines develop a bipolar neuronal morphology, express odorant receptors, upregulate Golf and OMP, and down regulate NST in a manner similar to olfactory neurons in vivo (Illing et al., 2002, Regad et al., 2007; Pathak et al., 2009).

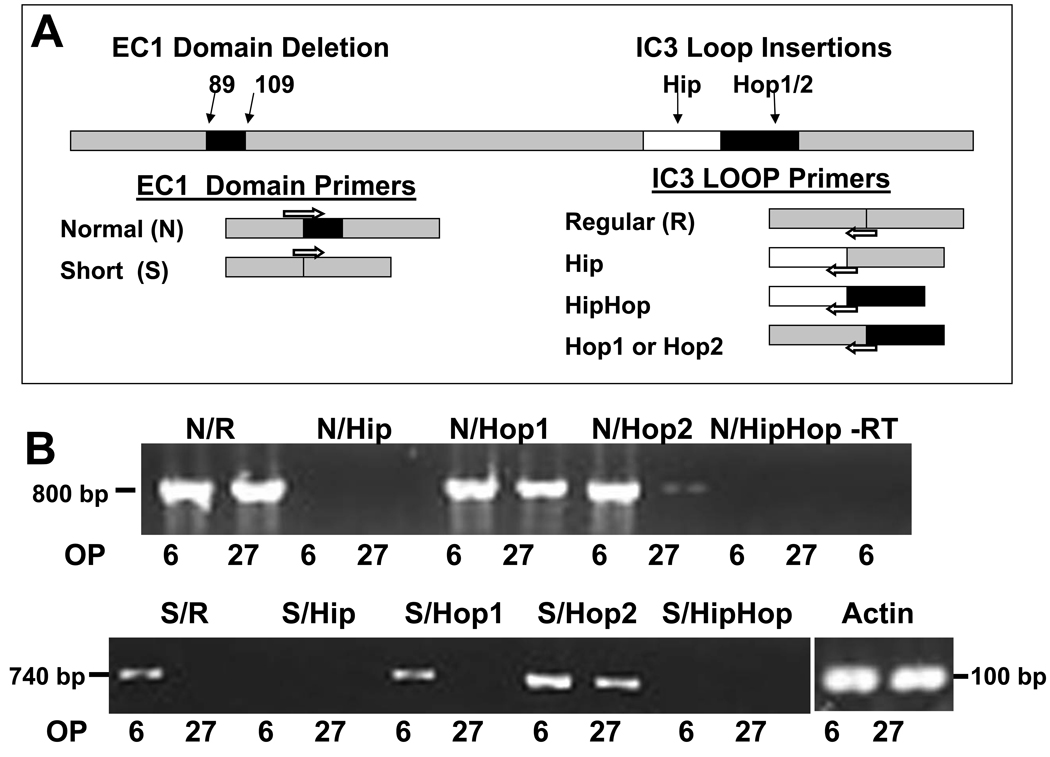

We examined the role of PACAP receptors and identified PAC1R subtypes expressed by the OP cell lines. The PACAP receptors PAC1, VPAC1 and VPAC2 have different agonist and antagonist profiles. Maxadilan is a potent vasodilatory peptide isolated from sandfly saliva (Lerner et al., 1991) which functions by activating the PAC1 receptor (PAC1R) (Lerner et al., 2007). Unlike PACAP itself, maxadilan binds specifically to PAC1R, and does not activate either of the VPAC receptors (Moro & Lerner, 1997). PACAP6–38 on the other hand is a truncated version of PACAP which functions as a PACAP receptor antagonist at both PAC1 and VPAC2 receptors, but does not block VPAC1 (Moro et al., 1999). Maxadilan and PACAP6–38 were therefore used to probe receptor specificity in this study. In addition, the PAC1 receptor occurs as several subtypes resulting from alternative splicing of mRNA encoding the first extracellular domain (EC1) (Pantaloni et al., 1996), and the third intracellular cytoplasmic loop (IC3) (Spengler et al., 1993). The most common EC1 variants are called normal (N, with no deletion) and short (S, with a 21 AA deletion), and these primarily regulate agonist binding (Pantaloni et al., 1996). IC3 splice variants occur as the regular form (R) without insertions, or with the inserted cassettes of Hip, Hop1, Hop2, or HipHop1/2 (Spengler et al., 1993). The IC3 splice variants govern coupling to either or both of the adenyl cyclase (AC) or phospholipase C (PLC) transduction pathways (Spengler et al., 1993; Ushiyama et al., 2007). We determined the PAC1R splice variants expressed by the OP cells to aid in identifying the second messenger systems activated by PACAP in this model.

In the present work, we use live-labeling with propidium iodide (PI) to show that TNFα induces cell death in neuronal precursors, and that TNFα-mediated cell death is reduced by PACAP via PAC1 receptor binding and activation of either the PLC or the AC/MAPKK second messenger systems. We also show that TNFα induced caspase activity is blocked by PACAP treatment in OP cells. These studies suggest that PACAP can be neuroprotective even if it does not precede TNFα release.

Results

PACAP protects against TNFα-induced cell death in live slices of the OE

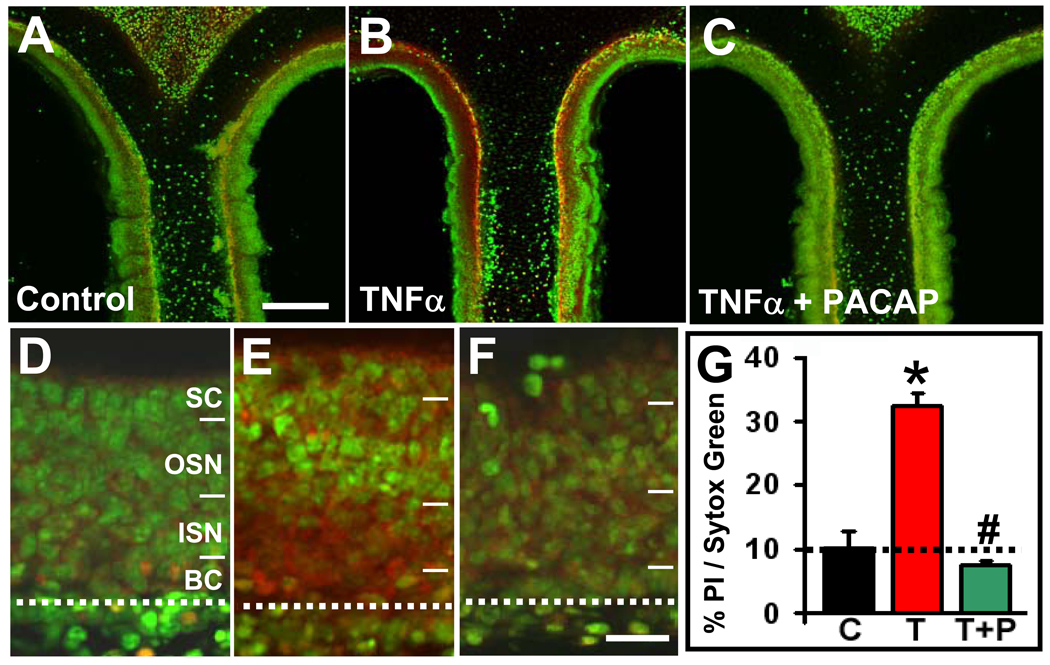

We treated live slices of OE from P1 mice with 40 ng/ml TNFα, TNFα+40 nM PACAP or vehicle for 6 hrs, and then live-labeled for 20 mins with 0.05% propidium iodide (PI), a dye that only enters dead or dying cells. Slices treated with TNFα (Fig. 1B, 1E) exhibited a significantly higher percentage of PI labeling (38 ± 6%, Fig. 1G) than vehicle controls (10 ± 3%, p=0.04, Fig. 1A, 1D). Co-incubating slices in both TNFα and PACAP (Fig. 1C, 1F) significantly reduced the percentage of PI labeling compared to TNFα alone (p=0.003) to a value that was not different from control (7 ± 1%, p=0.5, Fig. 1G). While TNFα treatment affected cells in all layers of the OE (Fig. 1E), the majority of PI labeling was in the basal to lower middle layers of the OE (Fig. 1D–F), which contain mainly basal progenitor cells, immediate neural precursors and immature neurons. These immature OE cells may thus be more vulnerable to the cumulative damaging effects of slicing and cytokine treatment than the mature neurons and sustentacular cells in the apical OE. PACAP reduced TNFα-induced PI labeling throughout the OE, demonstrating that PACAP can protect olfactory epithelial cells against cell death induced by TNFα, a cytokine endogenous to the OE (Farbman et al., 1999).

Figure 1. PACAP protects against TNFα-induced cell death in the olfactory epithelium.

Live coronal slices of OE from P1 mice were treated for 6 hrs with (A, D) vehicle control, (B, E) 40 ng/ml TNFα, or (C, F) 40 ng/ml TNFα and 40 nM PACAP. (A–C) Confocal projections (10 Z-stack images) of the dorsomedial septal area of the OE are shown, with dying cells labeled with PI (red) and all cells labeled with SYTOX-Green (scale bar = 200 µm). (D–F) Higher magnification images of the OE (confocal projections of 3 Z-stack images) demonstrate that a majority of the dying cells (red) are seen in the basal part of the OE, particularly in the ISN and BC layers. (SC: sustentacular cells, OSN: olfactory sensory neurons, ISN: immature sensory neurons, BC: basal cells; dotted line delineates the basement membrane. Scale bar = 30 µm) (G) Shown are the percentages of PI-pixel intensities vs. SYTOX-Green pixel intensities averaged across all slices and animals for each treatment (control [C]: 10 ± 3%; TNFα [T]: 33 ± 2%; TNFα + PACAP [T+P]: 7 ± 1 %; n = 3 mice. * = significantly different from control, Student’s T-test, p=0.04; # = significantly different from TNFα, Student’s T-test, p=0.003.

OE slice experiments however were relatively qualitative and did not differentiate between necrotic cell death and apoptosis nor distinguish between the different cell types of the olfactory mucosa. To focus our studies on neuronal cells of the OE, we assayed olfactory placodal cell lines of neuronal lineage.

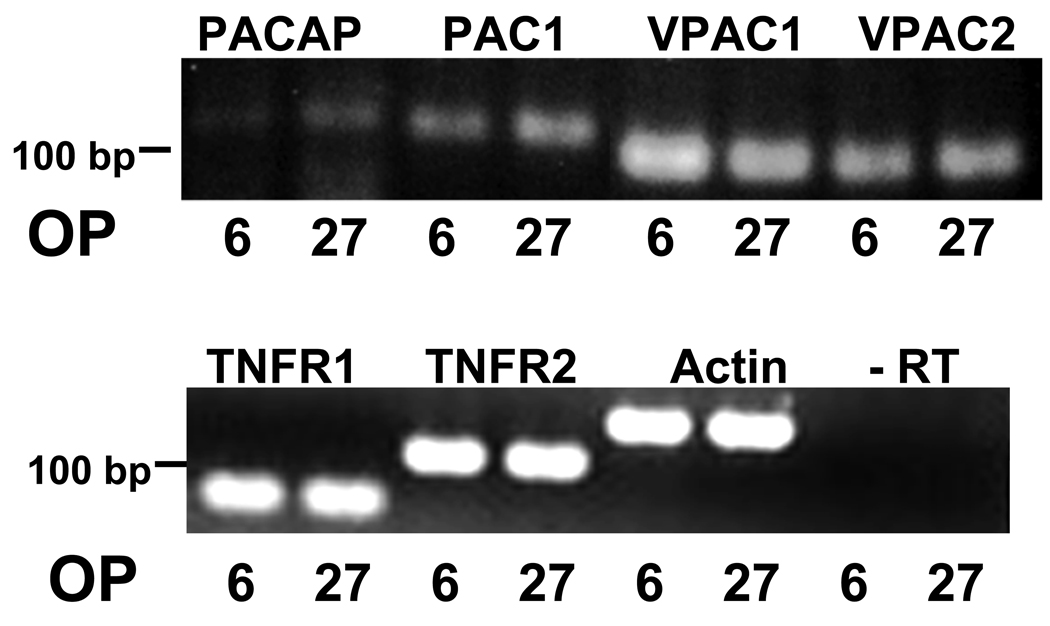

OP6 and OP27 cells express TNFα, PACAP and their receptors

OP6 and OP27 cells are clonal olfactory neuronal precursor cell lines derived from E10 mouse olfactory placode (Illing et al., 2002). Prior to using the OP cell lines in the apoptosis assay, we first determined whether they express receptors for the cytokine TNFα as well as PACAP and its receptors. RT-PCR showed that both OP6 and OP27 cells express both TNFR1 and TNFR2 (Fig. 2). RT-PCR also showed that OP6 and OP27 cells express PACAP and its receptors PAC1, VPAC1 and VPAC2 (Fig. 2). These data therefore indicate that the OP cell lines could function as an appropriate model system to examine a potential role for PACAP in protection against TNFα-induced neuronal cell death.

Figure 2. OP6 and OP27 cells express PACAP, and receptors for both TNFα, and PACAP.

In both OP6 and OP27 cells, RT-PCR showed expression of PACAP and all three PACAP receptors: PAC1, VPAC1 and VPAC2. Expression of TNF receptors, TNFR1 and TNFR2 was also seen in both cell lines (6 = OP6, 27 = OP27). Negative controls consisted of omitting the reverse transcriptase enzyme (-RT). Actin was used as a loading control.

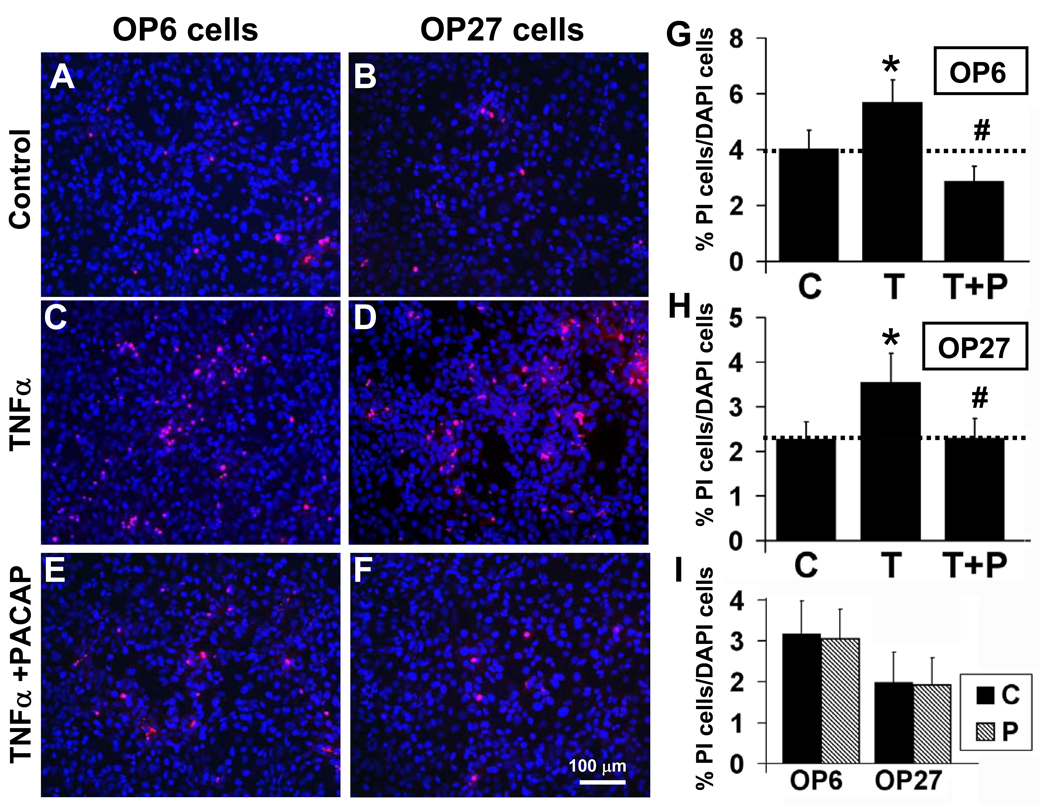

PACAP protects olfactory placodal cell lines against TNFα-induced cell death

To test the effects of PACAP on survival of cells of neuronal lineage, we cultured OP6 and OP27 cells for 5 hrs in the presence or absence of 40 ng/ml TNFα ± 40 nM PACAP. The percentage of PI-labeled to total cells was calculated for cultures treated with TNFα, TNFα+PACAP or vehicle. Under control conditions, PI labeled cells comprised 4 ± 0.7% of total in OP6 cells (Fig. 3A, 3G) and 2.3 ± 0.4% of total in OP27 cells (Fig. 3B, 3H). Treatment with TNFα significantly increased the level of cell death to 5.7 ± 0.8% in OP6 cells (Fig. 3C, 3G, n=15, p=0.003) and 3.5 ± 0.6% in OP27 cells (Fig. 3D, 3H, n=15, p=0.004). TNFα therefore increased cell death 42% above control in OP6 cells and 52% above control in OP27 cells.

Figure 3. PACAP protects against TNFα-induced cell death in OP cells.

OP6 cells and OP27 cells were treated for 5 hrs in vehicle control (A, B) 40 ng/ml TNFα (C, D) or 40 ng/ml TNFα + 40 nM PACAP (E, F). The percentage of dying cells (PI-labeled, red) to total cells (DAPI-labeled, blue) was determined for each treatment: control [C], TNFα [T] and TNFα+PACAP [T+P] in OP6 cells (G) and OP27 cells (H). Data is presented as mean ± SEM, n = 15 independent experiments. * = significantly different from control; # = significantly different from TNFα; paired Student’s T-test, p≤0.05. (I) Treatment of OP cells with 40 nM PACAP [P] alone did not change the percentages of cell death from control values [C] (n = 6, paired Student’s T-test, p≤0.05).

Co-incubating cells with TNFα and PACAP reduced the percentage of PI-labeled cells down to or below that seen in control: to 2.9 ± 0.5% in OP6 cells (Fig. 3E, 3G) and 2.3 ± 0.4% in OP27 cells (Fig. 3F, 3H). TNFα+PACAP treatment significantly lowered cell death from that seen with TNFα alone (n=15, p<0.001 (OP6); p=0.002 (OP27)). PACAP therefore protects against TNFα-induced cell death in the olfactory neuronal precursor cell lines, OP6 and OP27.

To examine whether PACAP treatment alone reduced cell death in the absence of TNFα, a subset of experiments included treatment of OP cells with PACAP at 40 nM (Fig. 3I). Treatment with PACAP alone did not significantly alter the level of dying cells compared to matched controls in either OP6 (3.1 ± 0.7% vs 3.2 ± 0.8%, n = 6, p=0.41) or OP27 cells (2 ± 0.7% vs 1.9 ± 0.7%, n = 6, p=0.88).

Caspase assay

To test whether TNFα induced necrotic or apoptotic cell death, we measured caspase activity in OP6 cells treated for 5 hours with TNFα, TNFα+PACAP or vehicle alone. OP6 cells treated with 40 ng/ml TNFα showed a significant increase in activity of the initiator caspase, caspase 8, (Kaushal & Schlichter, 2008) compared to control conditions: 115 ± 3% of that seen in control (n = 3 independent experiments, p=0.03). Inclusion of 40 nM PACAP with TNFα prevented the increase in caspase 8 activity (93 ± 11% of control; n = 3, p= 0.58). Induction of activated caspase 8 by TNFa and prevention of this induction by co-treatment with PACAP implies that both TNFa and PACAP mediate their effects at least partially, if not fully, on apoptotic cell death.

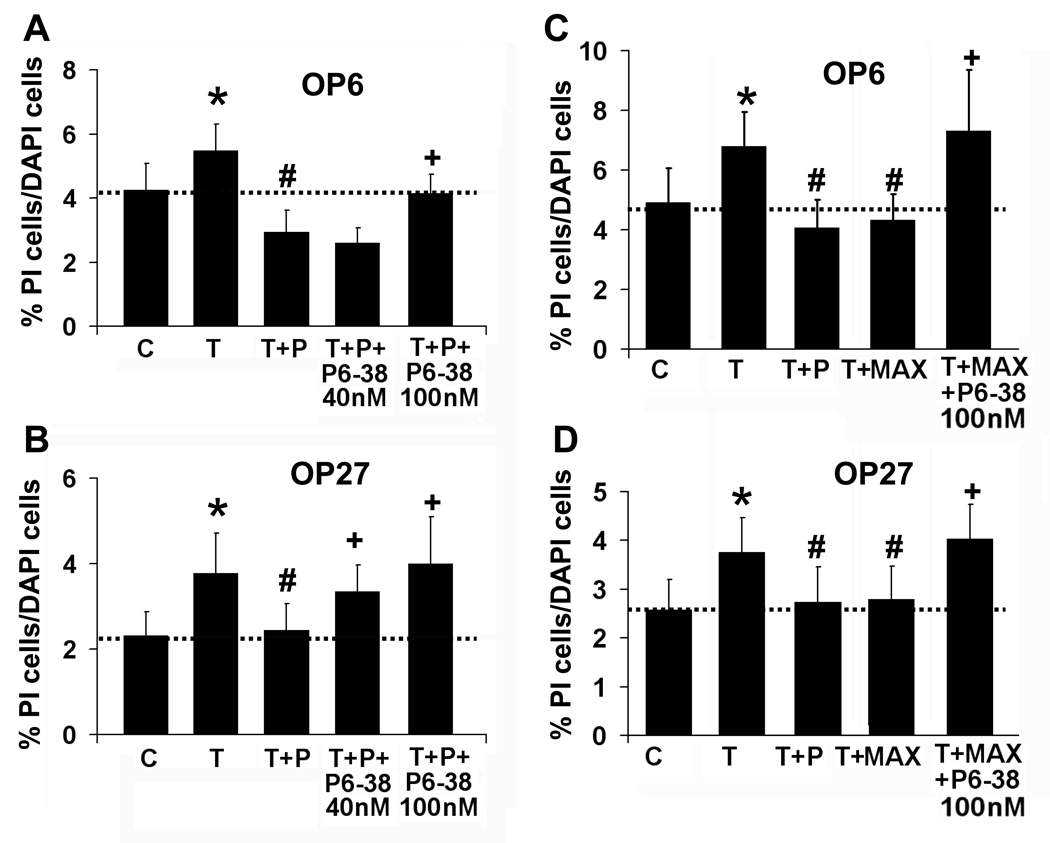

PACAP functions through PAC1R activation

To define the mechanism by which PACAP protects against TNFα-mediated cell death in olfactory placodal cells, we first looked at whether PACAP’s neuroprotective function is receptor-mediated. We co-incubated OP cells with TNFα+PACAP and the PAC1/VPAC2 specific antagonist PACAP6–38 at either 40 nM or 100 nM (Fig 4A). In OP6 cells, TNFα+PACAP reduced the PI-labeled cells from 5.5 ± 0.8% in TNFα alone to 2.9 ± 0.7%. Adding 40 nM PACAP6–38 to TNFα+PACAP did not significantly alter the level of PI-labeled OP6 cells from TNFα+PACAP (2.6 ± 0.5%, n = 6, p=0.10, Fig. 4A), while at 100 nM, the antagonist significantly reduced the protective effect of PACAP (4.2 ± 0.6%, n = 7, p=0.004). In OP27 cells, TNFα+PACAP reduced the PI-labeled cells from 3.8 ± 0.9% in TNFα alone to 2.4 ± 0.6%. PACAP6–38 was highly effective in blocking PACAP’s protection of OP27 cells, increasing the level of PI-labeled cells back to that seen with TNFα: 3.4 ± 0.6% at 40 nM and 4 ± 1% at 100 nM (n = 6, p=0.04; n = 7, p=0.03, Fig. 4B). Controls consisting of treating cells with PACAP6–38 alone at 40 nM or 100 nM or with TNFα+PACAP6–38 (100 nM), did not significantly alter the percentage of dying cells from that seen in matched controls or TNFα treatment respectively (Supplemental Data, Table 1).

Figure 4. The PAC1 receptor mediates the effects of PACAP.

Percentages of PI-labeled cells versus total cells are shown for OP6 cells (A) and OP27 cells (B) incubated for 5 hrs with vehicle control [C], 40 ng/ml TNFα [T], 40 ng/ml TNFα + 40 nM PACAP [T+P] in the presence and absence of the PAC1R antagonist PACAP6–38 [T+P+P6–38] at 40 nM (n = 6) or 100 nM (n = 7) and then live-labeled with PI and DAPI. Data is presented as mean ± SEM. * = significantly different from control; # = significantly different from TNFα; + = significantly different from TNFα+PACAP; paired Student’s T-test, p≤0.05. (C, D) Percentages of PI-labeled versus total cells are shown for OP cells incubated for 5 hrs with vehicle control [C], 40 ng/ml TNFα [T], 40 ng/ml TNFα + 40 nM PACAP [T+P], and 40 ng/ml TNFα + the PAC1R agonist maxadilan [T+P+Max] (100 pM, n = 7) in the presence and absence of the PAC1R antagonist PACAP6–38 at 100 nM [T+P+Max+P6–38] (n = 3) and then live-labeled with PI and DAPI. Data is presented as mean ± SEM, * = significantly different from control; # = significantly different from TNFα; + = significantly different from TNFα+maxadilan; paired Student’s T-test, p≤0.05.

We then proceeded to define whether both PAC1 and VPAC2 are involved in PACAP-mediated protection from TNFα-induced cell death in the OP cells. We used the PAC1 specific agonist maxadilan to see if TNFα-induced cell death could be suppressed solely by activating PAC1. Co-incubating OP6 cells with TNFα and maxadilan (100 pM) significantly reduced PI-labeled cells from 6.8 ± 1% with TNFα alone to 4.3 ± 0.9% (n = 7, p=0.002, Fig. 4C). This is not significantly different from the level of dying cells seen with TNFα+PACAP (4.1 ± 0.9%, p=0.22, Fig. 4C). In OP27 cells, maxadilan also functioned similarly to PACAP, significantly reducing PI labeling from 3.8 ± 0.7% in TNFα alone to 2.8 ± 0.7% (n = 7, p=0.03) vs. 2.7 ± 0.7% seen with TNFα+PACAP (p=0.71, Fig. 4D). Co-incubating cells with TNFα + maxadilan and the antagonist PACAP6–38 significantly increased the level of dying cells to 7.3 ± 2% in OP6 cells (n = 3, p=0.02) and 4 ± 0.7% in OP27 cells (n = 3, p=0.02). Maxadilan alone did not alter the level of dying cells from that seen in control (Supplemental Data Table 1). These data indicate that in OP cells, PACAP is functioning at least in part through PAC1 receptors. Since the PAC1 receptor occurs as several different splice variants which couple differentially with second messenger systems, we next looked at expression of PAC1R splice variants in the two cell lines.

OP6 and OP27 cells express different splice variants of PAC1R

We used RT-PCR to examine OP6 and OP27 cells for the presence of the dominant variants of PAC1R: Extracellular domain 1 (EC1) variants normal (N) or short (S) with third intracellular domain (IC3) variants regular (R), Hip, Hop1, Hop2 or HipHop (Ushiyama et al., 2007) (Fig. 5A, 5B). We found that both the N/R and N/Hop1 variants were expressed in both OP6 and OP27 cells (Fig. 5B). Of the other EC1 normal variants, OP6 cells also expressed N/Hop2. Of the EC1 short variants, OP6 and OP27 expressed the S/Hop2 variant, while OP6 cells also expressed S/R and S/Hop1 variants. Neither cell line expressed the IC3 insertion Hip in any combination: thus the N/Hip, N/HipHop, S/Hip or S/HipHop variants were absent in both OP6 and OP27 cells (Fig. 5B). OP27 cells therefore expressed only three PAC1R splice variants: N/R, N/Hop1 and S/Hop2. OP6 cells express these subtypes as well as N/Hop2, S/R and S/Hop1. These expressed splice variants have been shown to activate both the phospholipase C (PLC) and adenyl cyclase (AC) pathways while the absent Hip variant only activates the AC pathway (Spengler et al., 1993).

Figure 5. OP6 and OP27 express a different panel of PAC1R variants.

(A) A schematic diagram of PAC1R variants and primer design. Primers were created to identify variants in the extracellular 1 (EC1) and the third intracellular loop (IC3) domains of PAC1R. EC1 domain primers identified the normal (N) and the short (S, with a 21AA deletion) versions of EC1 domain variants. IC3 domain primers identified the regular (R) version, and the IC3 insertions of Hip, Hip/Hop, Hop1 or Hop2. Primers for each EC1 domain were used in combination with that for each IC3 domain to identify expression of the 10 dominant isoforms of PAC1R. (B) Both OP6 and OP27 cells expressed the N/R, N/Hop1 and S/Hop2 variants. In addition, OP6 cells expressed the N/Hop2, S/R and S/Hop1 variants. The IC3 insertions of Hip and Hip/Hop were not expressed in either cell line. Negative controls (-RT) consisted of omitting the reverse transcriptase enzyme. Actin was used as a loading control.

PACAP protects through the PLC signaling pathway

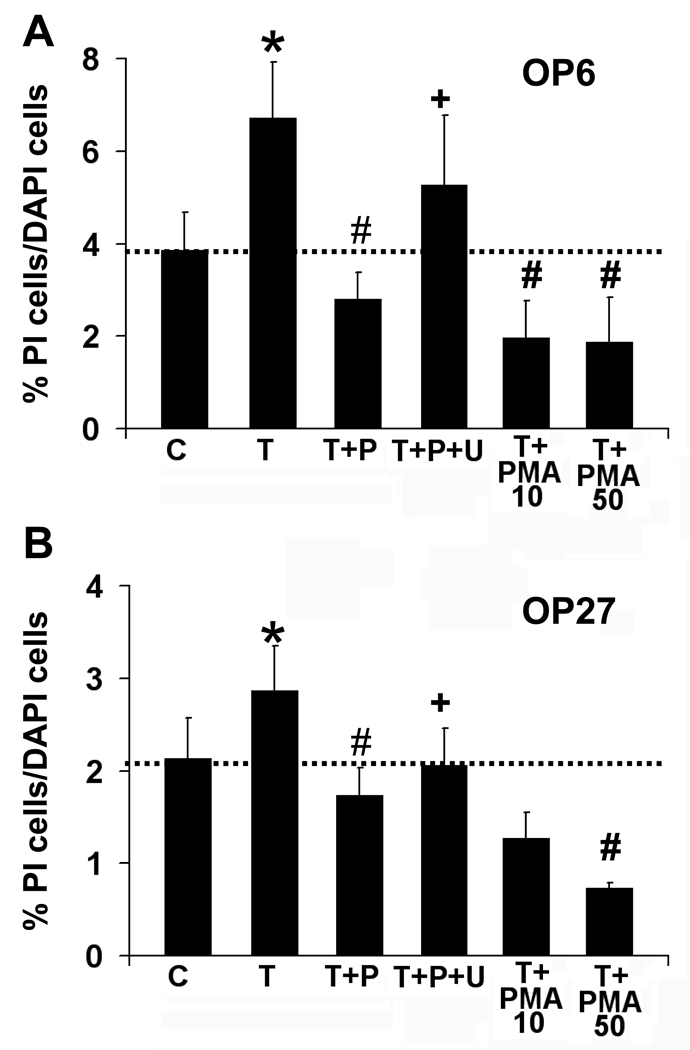

We next set out to identify the signaling mechanism by which PACAP protects against TNFα-induced cell death. Previous studies showed that PACAP reduces A-type K current and caspase activity through activation of PLC, and not AC, in mature OSNs in culture (Han & Lucero, 2005). Here we used phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) to directly activate protein kinase C (PKC), an effector protein downstream of PLC. Co-incubation of TNFα with PMA at 10 nM or 50 nM for 5 hrs significantly reduced the level of dying cells seen in both cell lines (Fig 6A, B). The level of PI-labeled OP6 cells dropped from 6.7 ± 1% in TNFα treatments to 2 ± 0.8% with 10 nM PMA (n = 3, p=0.03) and 1.9 ± 1% with 50 nM PMA (n = 3, p=0.004, Fig 6A). In OP27 cells, co-incubation of TNFα with 10 nM PMA reduced the level of PI-labeled cells from 2.9 ± 0.5% with TNFα treatment to 1.3 ± 0.3% (n = 3, p=0.06) while TNFα +PMA at 50 nM reduced the level to 0.7 ± 0.1% (n = 3, p=0.05, Fig 6B). PMA alone at 10 nM or 50 nM did not significantly alter the level of dying cells from that seen in control (Supplemental Data Table 2, p>0.05). Activating the PLC pathway using PMA thus significantly reduces TNFα-induced cell death, thereby mimicking PACAP’s effect against TNFα-induced cell death in both OP cell lines.

Figure 6. PACAP functions through the PLC pathway.

Percentages of PI-labeled cells versus total cells are shown for OP6 cells (A) and OP27 cells (B) incubated for 5 hrs with vehicle control [C], 40 ng/ml TNFα [T], 40 ng/ml TNFα + 40 nM PACAP [T+P] in the presence and absence of the PLC pathway antagonist U-73312 [T+P+U] at 100 µM (n = 5). In addition, 40 ng/ml TNFα was co-incubated with the PKC activator, PMA at 10 nM or 50 nM [T+PMA] (n = 3). Data is presented as mean ± SEM,* = significantly different from control; # = significantly different from TNFα; + = significantly different from TNFα+PACAP; paired Student’s T-test, p≤0.05.

Next, to examine whether blocking PLC activity could prevent PACAP’s function, we co-incubated cells with TNFα+PACAP and the PLC pathway blocker U-73122. Co-incubating cells with 100 µM U-73122 reduced the effect of PACAP on TNFα-induced cell death in both cell lines (Fig 6A, B). U-73122 significantly increased the level of cell death from 2.8 ± 0.6% in TNFα+PACAP-treated OP6 cells to 5.3 ± 1.5% with U-73122 (n = 5, p=0.04), which was not significantly different from TNFα treatment alone (6.7 ± 1.2%, p=0.18). In OP27 cells, cell death increased significantly from 1.7 ± 0.3% in TNFα+PACAP to 2.1 ± 0.4% when combined with U-73122 (n=5, p=0.03). However the level of cell death was still significantly lower than in TNFα alone (2.8 ± 0.5%, p=0.02), implying that U-73122 did not completely block PACAP’s protection of OP27 cells. U-73122 alone or TNFα+U-73122 did not significantly alter the percentage of dying cells from that seen in paired control or TNFα treatments respectively (Supplemental Data Table 2). These studies suggest that activating the PLC pathway is sufficient for protection from TNFα and that inhibiting the PLC pathway reveals an incomplete block of PACAP protection suggesting involvement of additional pathways.

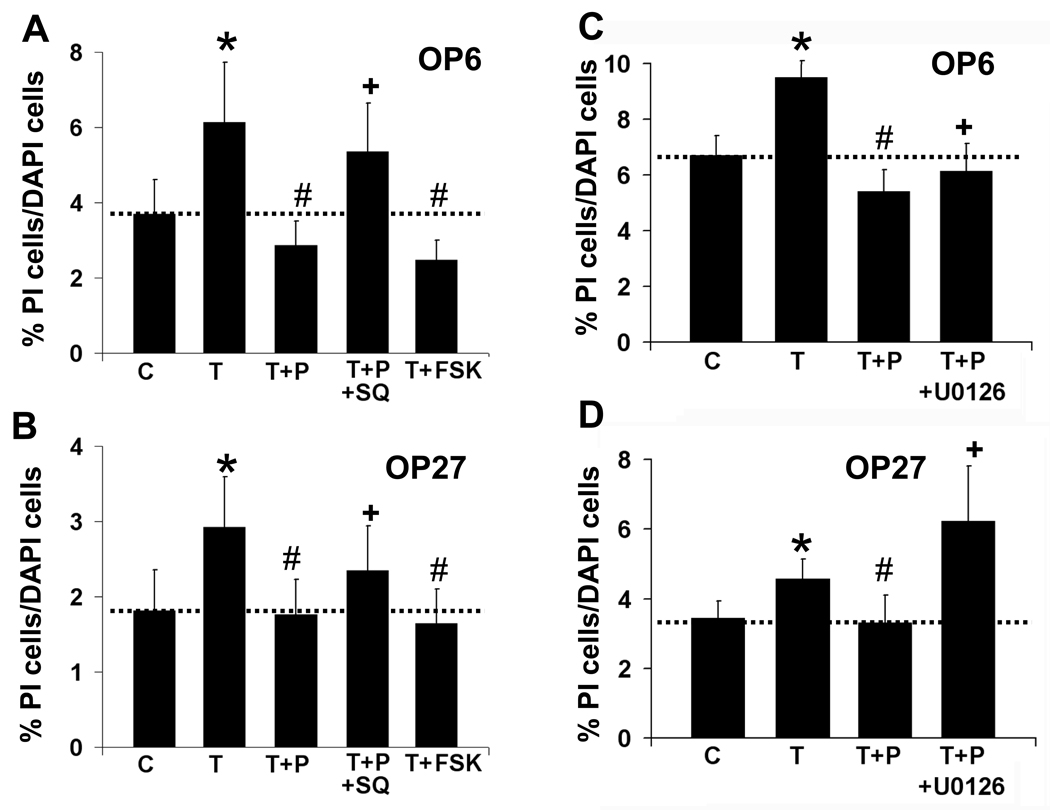

PACAP protects through the adenylate cyclase (AC) signaling pathway

In several models for CNS damage and disease, PACAP has been shown to be neuroprotective primarily by activation of protein kinase A or MAPKK through the AC pathway (Villalba et al., 1997). Since the PLC blocker did not eliminate PACAP’s inhibitory effect, we next looked at the potential role of AC in OP cells. Incubating cultures with TNFα and the AC activator forskolin (FSK, 20 µM) reduced the level of PI-labeled cells from 6.1 ± 1% in TNFα treated OP6 cells to 2.5 ± 0.5% with FSK (n = 6, p=0.02, Fig 7A), which is not significantly different from values for TNFα+PACAP treatment: 2.9 ± 0.6% (p=0.2). In OP27 cells, adding FSK to the TNFα treatment changed the level of PI-labeled cells from 2.9 ± 0.7% with TNFα alone to 1.6 ± 0.5% with TNFα+FSK (n = 6, p=0.007, Fig 7B), which was not significantly different from that seen with TNFα+PACAP (1.8 ± 0.5%, p=0.6). FSK alone did not significantly alter the level of dying cells from that seen in control (Supplemental Data Table 3). These data indicate that AC pathway activation can mimic the protective effect of PACAP on TNFα treatment of OP cells.

Figure 7. PACAP functions through the AC pathway.

(A, B) Percentages of PI-labeled cells versus total cells are shown for OP6 cells (A) and OP27 cells (B) incubated for 5 hrs with vehicle control [C], 40 ng/ml TNFα [T], 40 ng/ml TNFα + 40 nM PACAP [T+P] in the presence and absence of the AC pathway antagonist SQ77536 [T+P+SQ] at 300 µM. In addition, cells were treated with 40 ng/ml TNFα + the AC activator forskolin at 20 µM [T+FSK]. (C, D) Percentages of PI-labeled cells versus total cells are shown for OP6 cells (C) and OP27 cells (D) incubated for 5 hrs with vehicle control [C], 40 ng/ml TNFα [T],, 40 ng/ml TNFα + 40 nM PACAP [T+P] in the presence and absence of the MEK1/2 antagonist U0126 at 10 µM [T+P+U0126]. Data is presented as mean ± SEM, n = 6; *= significantly different from control; # = significantly different from TNFα; + = significantly different from TNFα+PACAP; paired Student’s T-test, p≤0.05.

We then used the AC blocker SQ22536 (300 µM) to attempt to eliminate PACAP’s function in OP cells by specifically blocking AC. In OP6 cells, SQ22536 abolished PACAP’s protective effect, increasing the level of cell death from: 2.9 ± 0.6% with TNFα+PACAP to 5.4 ± 1% when SQ22536 was added (Fig 7A, n = 6, p=0.03). SQ22536 also significantly blocked PACAP function in OP27 cells, increasing cell death from 1.8 ± 0.5% with TNFα+PACAP to 2.3 ± 0.6% with the AC blocker (Fig. 7B, n = 6, p=0.04). SQ22536 alone or TNFα+SQ22536 did not significantly alter the level of dying cells from that seen in control or TNFα respectively (Supplemental Data Table 3). PACAP therefore can also function in this model of cell death through activation of the AC pathway.

To further investigate the second messenger pathways used by PACAP in its protective role against TNFα-induced cell death, we looked at the effect of incubating cells with the MEK1/2 inhibitor, U-0126 in conjunction with TNFα+PACAP. Adding 10 µM U-0126 significantly reduced PACAP’s protective function by increasing the level of PI-labeled OP6 cells from 5.4 ± 0.8% in TNFα+PACAP to 6.1 ± 1% with the MEK1/2 inhibitor (Fig 7C, n = 5, p=0.05). In OP27 cells, adding U-0126 increased the level of PI-labeled cells from 3.3 ± 0.8% in TNFα+PACAP to 6.2 ± 1% with the MEK1/2 inhibitor (Fig 7D, n = 5, p=0.04). Incubation of OP cells with U-0126 alone or with TNFα+U-0126 did not significantly alter the level of cell death from that seen in control or TNFα treatments respectively (Supplemental Data Table 3). PACAP can therefore use the MAPKK pathway to protect against TNFα-induced cell death in OP cell lines.

Discussion

We showed that PACAP can protect olfactory sensory neurons against cell death induced by TNFα, a cytokine endogenous to the olfactory epithelium. PACAP protected cells in live OE slices as well as olfactory placodal cells of neuronal lineage against TNFα-induced cell death. Assays to measure caspase activity indicated that caspase 8, an apoptosis initiator caspase is significantly increased by 5 hours of TNFα treatment and this increase is blocked by PACAP, suggesting that TNFα-induced cell death involves apoptosis. However since the majority of experiments were performed using PI which does not distinguish between apoptosis and necrosis, we conservatively describe our results in terms of cell death rather than apoptosis. Our studies show that PACAP mediated this protection via activation of PAC1R and signaling through adenylate cyclase and/or phospholipase C. We also showed that the olfactory placodal cell lines OP6 and OP27 express all three PACAP receptors and several PAC1R isoforms. To our knowledge, these data are the first to show PACAP-mediated protection against TNFα-induced cell death in olfactory neuroepithelium or olfactory neuronal cell lines.

PACAP and Receptor expression in OP6 and OP27 cells

PACAP belongs to the secretin-glucagon superfamily of peptides (Kieffer & Habener, 1999) and occurs as either a 38 or a 27 amino acid peptide. The 38 amino acid peptide (PACAP38) is the predominant form of PACAP and is the focus of the present work. PACAP27 is formed through post-translational modification and represents only 10% of the PACAP peptide measured in various brain regions (Mikkelsen et al., 1995). Both isoforms of PACAP and the closely-related peptide VIP bind to three GPCRs (PAC1R, VPAC1 and VPAC2) with PACAP38 and PACAP27 having a 500 to 1000 fold higher affinity than VIP at PAC1R and similar affinities as VIP at the VPAC receptors (Spengler et al., 1993). The presence of mRNA for PACAP and all three of its receptors in the OP cell lines suggests that PACAP signaling is important in olfactory neuronal precursors.

We found that PACAP significantly inhibited TNFα-induced cell death through a PAC1R-specific mechanism in both cell lines. Although VPAC1 and VPAC2 also bind PACAP, the effects of TNFα were significantly reduced by maxadilan, a PAC1R selective agonist. These studies suggest that PAC1R activation alone is sufficient to mimic the neuroprotective effects of PACAP.

Interestingly, we found differences in the efficacy of PACAP6–38, a PAC1R antagonist between the two OP cell lines: PACAP6–38 was effective at significantly blocking PACAP activity at a lower dose (40 nM) in OP27 cells compared to OP6 cells. In addition, although PACAP equally eliminated the TNFα-induced component of cell death in OP6 and OP27 cells, TNFα+PACAP treatments in the 2 cell lines differed relative to their respective controls. PACAP alone did not significantly alter cell death over that seen in control. However, in the presence of TNFα, PACAP reduced the level of cell death significantly below control levels in OP6 cells (p=0.003) but not in OP27 cells (p=0.79). OP cells express both types of TNFα receptor, TNF1 and TNF2. TNFR1 activates the apoptotic pathway, while TNFR2 activation can be protective against apoptosis. It is possible that when cells are treated with TNFα+PACAP, TNFα, acting through the TNF2 receptors, synergizes with PAC1 receptor activation thereby increasing the protection against apoptosis, while in the absence of PACAP, TNFα binding to TNF1 receptors overcomes any beneficial effect of TNFα binding to TNF2 receptors, and the end result is increased cell death. The different levels of maturation between OP6 and OP27 cells may also contribute to this differential effect in baseline neuroprotection.

Supporting the idea of multiple roles for PACAP in OP cells, we found 6 PAC1R splice variants in OP6 cells and 3 PAC1R splice variants in OP27 cells. OP6 cells expressed N/R, N/Hop1, S/Hop2, N/Hop2, S/R and S/Hop1 while OP27 cells expressed N/R, N/Hop1, and S/Hop2. The R and Hop1/2 splice variants strongly activate both PLC and AC pathways, while Hip which is absent from OP cells, exclusively activates the AC pathway (Spengler et al., 1993). Differential expression of PAC1R variants alone can regulate neuronal function through differential coupling to second messenger systems (Nicot & Dicicco-Bloom, 2001), implying that the splice variants present in OP cells allow for PACAP’s activation of the AC and PLC pathways.

PACAP mediates neuroprotection by AC and PLC pathways

PACAP has varied functions in a wide range of tissues (Vaudry et al., 2009). PACAP has been shown to be protective to cells in tissues including the heart (Gasz et al., 2006), kidney (Li et al., 2008), immune system (Delgado et al., 2003a), and the nervous system (Shioda et al., 2006). In the nervous system, PACAP’s protective role includes increasing proliferation and survival of both neurons and glia (Waschek, 2002), reducing the level of programmed cell death during development (Falluel-Morel et al., 2007) and protecting neurons against cytotoxicity induced by glutamate (Morio et al., 1996), ethanol (Vaudry et al., 2002b), ischemia (Unal-Cevik et al., 2004), oxidative stress (Vaudry et al., 2002a) and bacterial or viral infections (Kim et al., 2000). PACAP has been shown to be neuroprotective in several systems, including in vitro models for apoptosis using cerebellar granule cells (Falluel-Morel et al., 2007), rat cortical neurons (Morio et al., 1996) or PC12 cells (Onoue et al., 2002), as well as in in vivo models for Parkinson’s disease (Reglodi et al., 2004). PACAP primarily functions in these systems through activation of protein kinase A or MAPKK through the AC pathway (Dejda et al., 2005; Villalba et al., 1997). The present study also showed involvement of the AC/MAPKK pathway in the PACAP-mediated protection of OP cells. Forskolin significantly increased cell survival in the presence of TNFα while the AC inhibitor SQ22536 and the MEK1/2 inhibitor U-0126 reduced the protective effects of PACAP.

In contrast to the predominance of the AC pathway for neuroprotection in other systems, the PLC pathway was also implicated in the neuroprotective effects of PACAP on OP cells. The protein kinase C agonist PMA mimicked the effects of PACAP while the PLC antagonist U-73122 inhibited the effects of PACAP in both cell lines. Previous work showed that PACAP exclusively utilizes the PLC pathway in reducing axotomy-induced apoptosis of mature OSNs (Han & Lucero, 2005; Han & Lucero, 2006). It will be interesting to directly determine whether the differences in second messenger pathway efficacy are due to differences between axotomy and TNFα or to the difference in maturation between the OP cell lines and mature neurons.

Conclusions

Collectively, our studies show that PACAP is effective at reducing TNFα-induced PI labeling (a marker for cell death) in slices of neonatal olfactory epithelium as well as in two cell lines of neuronal progenitors derived from olfactory placode. A recent transgenic model for chronic rhinosinusitus shows that chronic OE expression of TNFα leads to a gradual loss of OSNs over 42 days (Lane et al., 2010). This surprisingly slow time course for TNFα-induced neuronal death may reflect the ability of endogenous PACAP to protect against TNFα-mediated cell death in the OE in vivo. In our OE slice studies, TNFα accelerated the rate of death to hours rather than days, likely due to higher concentrations and the summed insults inherent with slice preparation. Remarkably, PACAP blocked the TNFα–induced PI labeling in OE slices suggesting protection from cell death. The success of PAC1R activation in reducing cytokine insult both in situ and in cell lines suggests that PACAP might be a promising therapeutic for protecting neurons and/or neuronal progenitors from inflammatory damage by TNFα.

Experimental Methods

Chemicals

PACAP38 and PACAP6–38 were obtained from Bachem Chemicals (Torrance, CA). TNFα, phorbol 12-myristate13-acetate (PMA), U-73122, U-0126, forskolin, SQ22536 and other chemicals were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) unless otherwise mentioned. Propidium iodide (PI) was obtained from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). Maxadilan was a generous gift from Dr. Ethan Lerner (Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA).

OE live slice experiments

All animal procedures were conducted under the guidelines of the NIH Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the University of Utah Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Coronal olfactory epithelial slices (250 µm thick) were prepared from postnatal day 1 (P1) C57/B16 mice as previously described (Hegg et al., 2003b). Slices were cut and collected in ice cold Ringer’s solution (in mM: 140 NaCl, 5 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 2 CaCl2, 10 HEPES and 10 Glucose), and then transferred immediately into assay medium (DMEM/F12 + 0.5% BSA) with TNFα (40 ng/ml), TNFα+PACAP (40 nM) or assay medium alone (vehicle control). The total slices obtained from each mouse were divided equally between the 3 treatments. Slices were exposed to treatments for 6 hrs at 37°C in a tissue culture incubator (Suzuki & Farbman, 2000) and then live-labeled for 20 mins with 0.5% PI to identify dying cells. Slices were then fixed with 20% Formal-Fixx (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA) for 20 mins and stained with 10 µM SYTOX-Green (Molecular Probes, Carlsbad, CA) to label cellular nuclei. (A total of 9–11 slices were cut from the OE of one mouse, these were split between the 3 treatments, and therefore 2–3 slices were imaged per treatment per mouse.) Slices were then imaged at identical settings across all treatments using a Zeiss confocal LSM510 argon-krypton laser scanner attached to a Zeiss Axioskop 2FS microscope. Regions of interest (ROIs) were drawn around the dorsal recess and septum, and fluorescence intensity was measured using LSM510 software. The percentage of dying cells (PI-labeling) versus total cells (SYTOX-Green-labeling) was determined by dividing the total number of pixels labeled with PI by those labeled with SYTOX-Green × 100 (threshold pixel intensity = 100; bin width = 6). The ratio of PI/SYTOX-Green pixels in the 3 treatments is expressed as mean ± SEM, n = 3 mice; independent Student’s T test, p≤0.05. This assay provides an overall qualitative assessment of the effects of TNFα and PACAP on cell death in live OE slices and does not yield information on actual cell counts.

Tissue culture

The olfactory placodal (OP) cells lines OP6 and OP27 were obtained from the laboratory of Dr. A. J. Roskams (Univ. British Columbia, Vancouver, BC). Cells were grown in a tissue culture incubator at 33°C in DMEM/F12 media supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% anti-mycotic/antibiotic (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). All treatments were added to assay media which consisted of DMEM/F12 with 0.5% BSA. While these cells can be induced to differentiate, all of our studies were done on undifferentiated OP6 and OP27 cells as determined by the absence of cells with mature neuronal morphology: an apical ciliated dendrite and basal axon.

Cell death assays

Initial assays were done to determine the optimal conditions under which cell death could be induced by TNFα. OP6 and OP27 cells were treated to several concentrations of TNFα for 24 hrs: 1, 2, 5, 10, 20 and 40 ng/ml (data not shown). The 40 ng/ml treated cultures had the highest level of cell death. To determine the optimal time of TNFα exposure, cells were treated to 10 ng/ml or 40 ng/ml TNFα for periods of 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 12 and 24 hrs (data not shown). The optimal treatment was found to be 40 ng/ml of TNFα for 5 hrs, similar to that used in previous studies inducing apoptosis in organotypic cultures of the embryonic mouse OE (Suzuki & Farbman, 2000). All assays were done in parallel using both OP6 and OP27 cells, with 3–4 coverslips assayed per treatment per experimental trial. Experiments were repeated a minimum of three times.

Cells were plated in culture media at 1.5 × 105 cells per well on 12 mm glass coverslips placed in 24 well tissue culture plates. The next day, cells were treated with 40 ng/ml TNFα, TNFα+PACAP (40 nM), or assay media (vehicle control). In addition to these treatments, we tested blockers and activators of various pathways that might be involved in PACAP’s actions on TNFα-mediated cell death. Control treatments included treating with the test agents alone, or with vehicle (DMSO) for test agents, and were without significant effects (Supplemental data, Tables 1–3). After a 5 hr exposure period at 33°C in a tissue culture incubator, media was replaced with 0.5% PI in assay media for 20 mins to label nuclei of dying cells. After rinsing with PBS, cells were fixed with 20% Formal-Fixx for 15 mins. Cells were then rinsed with PBS and stained with DAPI to label all cellular nuclei. Coverslips were then mounted onto slides using Vectastain mounting media (Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA).

Cell count analysis

Slides were blinded and images taken using a Zeiss Axioplan2 microscope, attached Axiocam camera and Axioscan software. Both DAPI and PI labeling were imaged from 5 representative areas on each of the 3–4 coverslips used per treatment. For each image, total cells (DAPI-labeled cells) and dead/dying cells (PI labeled cells) were counted using ImageJ software (NIH). The total number of cells in each image ranged from approximately 600–1200 cells. The percentage of dying cells (PI cells/DAPI cells × 100) was calculated for each treatment. Data are presented as mean ± SEM, with n = number of times an experiment (trial) was performed per cell line.

Statistical significance was set at p≤0.05. To control for conditions that could vary between trials, treatment comparisons were made within the same trial using the paired sample T-test. Unlike the independent sample T-test, which assumes a correlation of zero between two groups, the paired T-test assumes that a correlation in the treatments within each trial is non-zero. To verify this assumption, a Pearson’s correlation coefficient was computed within trial treatment pairs. As expected, there was a high correlation between treatments done within the same trial: in 15 trials, the correlation coefficient for control vs TNFα treatments was r=0.83, p<0.001, in OP6 cells and r=0.84, p=<0.001, in OP27 cells; between TNFα and TNFα+PACAP treatments was r=0.86, p=<0.001, in OP6 cells and r=0.89, p<0.001, in OP27 cells. The large r values verified that the paired T-Test was appropriate. Consistent with paired significance testing, data are presented with the within trial control, TNFα and TNFα+PACAP treatment values for each subset of experiments.

Caspase assays

To identify the activated caspases, we used a fluorometric caspase assay kit as per manufacturer’s instructions (Biovision, Mountain View, CA). Cells were plated at 0.6 × 105 – 0.6 × 106 cells/ well in 96 well plates and treated with TNFα, TNFα+PACAP or vehicle [DMEM/F12 + 0.5% BSA] for 5hrs as described above. Plates were read using a SpectraMax Gemini EM microplate spectrophotometer (Molecular Devices). Caspase assays were done in duplicate, and repeated 3 times using OP6 cells. Statistical analysis was done using paired Student’s T-test at p≤0.05.

RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted from OP6 and OP27 cells using the RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Genomic DNA was eliminated by digesting with RNAse-free DNAse I. The total RNA concentration was determined by measuring the optical density at 260 nm. First-strand cDNA was synthesized using SuperScript III reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and oligo dT primers. A total amount of 50 ng cDNA was used for all PCR reactions. The final reaction mixture of 25 µL contained 0.6 µM each of forward and reverse primers, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM dNTPs and 5 units of platinum taq DNA Polymerase (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). All the PCRs were done for 40 cycles at an annealing temperature of 63°C and extension at 72°C.

Primers used were PACAP forward primer- 5’-gtatgggataataatgcatagcagtg-3’; PACAP reverse primer: 5’-ctggtcgtaagcctcgtct-3’; VIP forward primer: 5’-agtgtgctgttctctcagtcg-3’; VIP reverse primer: 5’-gccattttctgctaagggattct-3’; PAC1R forward primer: 5’-gcttcctgaatggggaggta-3’; PAC1R reverse primer: 5’-ggtgcttgaagtccatagtg-3’; VPAC1 forward primer: 5’-gatgtgggacaacctcacctg-3’; VPAC1 reverse primer: 5’-tagccgtgaatgggggaaaac-3’; VPAC2 forward primer: 5’-gacctgctactgctggttg-3’; VPAC2 reverse primer: 5’-cagctctgcacattttgtctct-3’; TNFR1 forward primer: 5’-acaccctacaaaccggaacc-3’; TNFR1 reverse primer: 5’-tgagccttcctgtcatagtattcct-3’; TNFR2 forward primer: 5’-cgggagaagagggatagctt-3’; TNFR2 reverse primer: 5’-tcggacagtcactcaccaagt-3’; ACTIN forward primer: 5’-ggctgtattcccctccatcg-3’; ACTIN reverse primer: 5’-ccagttggtaacaatgccatgt-3’.

To amplify the various combinations of PAC1R splice variants in the first extracellular (EC1) domain (normal and short) with the different splice variants in the third intracellular (IC3) domain (regular, HIP, HOP1, HOP2 and HIP/HOP), primer combinations (8 total) were designed based on published work (Ushiyama et al., 2007). The schematics in Fig. 5A show the design of the combination primers. The PCR products of these combination primer sets had expected sizes of 741–891 bp.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. A.J. Roskams for providing OP6 and OP27 cell lines; Dr. E. Lerner for providing maxadilan; Dr. W. Michel for use of his microscope and helpful suggestions on the manuscript; Dr. A. Greig for technical support. Funded by NIH NIDCD DC002994, CSS/ARRA supplements to SK, AG, and NIA 1K07AG028403-01A1 from the Utah Center on Aging.

List of abbreviations

- AA

amino acid

- AC

adenylate cyclase

- BSA

bovine serum albumin

- cAMP

cyclic adenosine monophosphate

- CNS

central nervous system

- dNTP

deoxynucleotide triphosphate

- dT

deoxythymidine

- EC1

first extracellular domain of PAC1R sequence

- FBS

fetal bovine serum

- FSK

forskolin

- GPCR

G-protein-coupled receptor

- IC3

third intracellular domain of PAC1R sequence

- INP

immediate neuronal precursor

- IRN

immature receptor neuron

- K

potassium

- MAPKK

mitochondrial activated protein kinase kinase

- N

normal variant of EC1 domain of PAC1R

- n

number of animals used, or cell-based experiments done

- NST

neuron specific tubulin

- OE

olfactory epithelium

- OMP

olfactory marker protein

- OP

olfactory placodal

- OSN

olfactory sensory neuron

- P1

post-natal day 1

- PACAP

pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating peptide

- PAC1R

PACAP-specific receptor

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- PI

propidium iodide

- PLC

phospholipase C

- PMA

phorbol 12-myristate13-acetate

- PKC

protein kinase C

- R

regular variant of IC3 domain of PAC1R

- ROI

regions of interest

- RT-PCR

reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction

- S

short variant EC1 domain of PAC1R

- TNFα

tumor necrosis factor α

- TNFR1, TNFR2

TNFα receptors

- VIP

vasointestinal peptide

- VPAC1,VPAC2

receptors for VIP

- VS

very short variant of EC1 domain of PAC1R

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Shami Kanekar, Email: Shami.Kanekar@hsc.utah.edu.

Mahendra Gandham, Email: gmahendra6@yahoo.com.

Mary T Lucero, Email: mary.lucero@utah.edu.

References

- 1.Clausen BH, Lambertsen KL, Babcock AA, Holm TH, Dagnaes-Hansen F, Finsen B. Interleukin-1beta and tumor necrosis factor-alpha are expressed by different subsets of microglia and macrophages after ischemic stroke in mice. J.Neuroinflammation. 2008;5:46. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-5-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dejda A, Sokolowska P, Nowak JZ. Neuroprotective potential of three neuropeptides PACAP, VIP and PHI. Pharmacol.Rep. 2005;57:307–320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Delgado M, Abad C, Martinez C, Juarranz MG, Leceta J, Ganea D, Gomariz RP. PACAP in immunity and inflammation. Ann.N.Y.Acad.Sci. 2003a;992:141–157. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2003.tb03145.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Delgado M, Leceta J, Ganea D. Vasoactive intestinal peptide and pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide inhibit the production of inflammatory mediators by activated microglia. J.Leukoc.Biol. 2003b;73:155–164. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0702372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Falluel-Morel A, Chafai M, Vaudry D, Basille M, Cazillis M, Aubert N, Louiset E, de Jouffrey S, Le Bigot JF, Fournier A, Gressens P, Rostene W, Vaudry H, Gonzalez BJ. The neuropeptide pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide exerts anti-apoptotic and differentiating effects during neurogenesis: focus on cerebellar granule neurones and embryonic stem cells. Journal of Neuroendocrinology. 2007;19:321–327. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2007.01537.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Farbman AI, Buchholz JA, Suzuki Y, Coines A, Speert D. A molecular basis of cell death in olfactory epithelium. J.Comp Neurol. 1999;414:306–314. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19991122)414:3<306::aid-cne2>3.0.co;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gasz B, Racz B, Roth E, Borsiczky B, Ferencz A, Tamas A, Cserepes B, Lubics A, Gallyas F, Jr, Toth G, Lengvari I, Reglodi D. Pituitary adenylate cyclase activating polypeptide protects cardiomyocytes against oxidative stress-induced apoptosis. Peptides. 2006;27:87–94. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2005.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Graziadei PP, Graziadei GA. Neurogenesis and neuron regeneration in the olfactory system of mammals. I. Morphological aspects of differentiation and structural organization of the olfactory sensory neurons. Journal of Neurocytology. 1979;8:1–18. doi: 10.1007/BF01206454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Han P, Lucero MT. Pituitary adenylate cyclase activating polypeptide reduces A-type K+ currents and caspase activity in cultured adult mouse olfactory neurons. Neuroscience. 2005;134:745–756. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Han P, Lucero MT. Pituitary adenylate cyclase activating polypeptide reduces expression of Kv1.4 and Kv4.2 subunits underlying A-type K(+) current in adult mouse olfactory neuroepithelia. Neuroscience. 2006;138:411–419. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hansel DE, Eipper BA, Ronnett GV. Regulation of olfactory neurogenesis by amidated neuropeptides. Journal of Neuroscience Research. 2001;66:1–7. doi: 10.1002/jnr.1191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hegg CC, Au E, Roskams AJ, Lucero MT. PACAP is present in the olfactory system and evokes calcium transients in olfactory receptor neurons. Journal of Neurophysiology. 2003a;90:2711–2719. doi: 10.1152/jn.00288.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hegg CC, Greenwood D, Huang W, Han P, Lucero MT. Activation of purinergic receptor subtypes modulates odor sensitivity. Journal of Neuroscience. 2003b;23:8291–8301. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-23-08291.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Illing N, Boolay S, Siwoski JS, Casper D, Lucero MT, Roskams AJ. Conditionally immortalized clonal cell lines from the mouse olfactory placode differentiate into olfactory receptor neurons. Mol.Cell Neurosci. 2002;20:225–243. doi: 10.1006/mcne.2002.1106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaushal V, Schlichter LC. Mechanisms of microglia-mediated neurotoxicity in a new model of the stroke penumbra. Journal of Neuroscience. 2008;28:2221–2230. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5643-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kieffer TJ, Habener JF. The glucagon-like peptides. Endocr.Rev. 1999;20:876–913. doi: 10.1210/edrv.20.6.0385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim WK, Kan Y, Ganea D, Hart RP, Gozes I, Jonakait GM. Vasoactive intestinal peptide and pituitary adenylyl cyclase-activating polypeptide inhibit tumor necrosis factor-alpha production in injured spinal cord and in activated microglia via a cAMP-dependent pathway. Journal of Neuroscience. 2000;20:3622–3630. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-10-03622.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lane AP, Turner J, May L, Reed R. A genetic model of chronic rhinosinusitis-associated olfactory inflammation reveals reversible functional impairment and dramatic neuroepithelial reorganization. Journal of Neuroscience. 2010;30:2324–2329. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4507-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lerner EA, Iuga AO, Reddy VB. Maxadilan, a PAC1 receptor agonist from sand flies. Peptides. 2007;28:1651–1654. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2007.06.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lerner EA, Ribeiro JM, Nelson RJ, Lerner MR. Isolation of maxadilan, a potent vasodilatory peptide from the salivary glands of the sand fly Lutzomyia longipalpis. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1991;266:11234–11236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li M, Maderdrut JL, Lertora JJ, Arimura A, Batuman V. Renoprotection by pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide in multiple myeloma and other kidney diseases. Regulatory Peptides. 2008;145:24–32. doi: 10.1016/j.regpep.2007.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McCoy MK, Tansey MG. TNF signaling inhibition in the CNS: implications for normal brain function and neurodegenerative disease. J.Neuroinflammation. 2008;5:45. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-5-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mikkelsen JD, Hannibal J, Fahrenkrug J, Larsen PJ, Olcese J, McArdle C. Pituitary adenylate cyclase activating peptide-38 (PACAP-38), PACAP-27, and PACAP related peptide (PRP) in the rat median eminence and pituitary. Journal of Neuroendocrinology. 1995;7:47–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.1995.tb00666.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morio H, Tatsuno I, Tanaka T, Uchida D, Hirai A, Tamura Y, Saito Y. Pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide (PACAP) is a neurotrophic factor for cultured rat cortical neurons. Ann.N.Y.Acad.Sci. 1996;805:476–481. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1996.tb17507.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moro O, Lerner EA. Maxadilan, the vasodilator from sand flies, is a specific pituitary adenylate cyclase activating peptide type I receptor agonist. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1997;272:966–970. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.2.966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moro O, Wakita K, Ohnuma M, Denda S, Lerner EA, Tajima M. Functional characterization of structural alterations in the sequence of the vasodilatory peptide maxadilan yields a pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating peptide type 1 receptor-specific antagonist. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1999;274:23103–23110. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.33.23103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nicot A, Dicicco-Bloom E. Regulation of neuroblast mitosis is determined by PACAP receptor isoform expression. Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.U.S.A. 2001;98:4758–4763. doi: 10.1073/pnas.071465398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Onoue S, Endo K, Ohshima K, Yajima T, Kashimoto K. The neuropeptide PACAP attenuates beta-amyloid (1–42)-induced toxicity in PC12 cells. Peptides. 2002;23:1471–1478. doi: 10.1016/s0196-9781(02)00085-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pantaloni C, Brabet P, Bilanges B, Dumuis A, Houssami S, Spengler D, Bockaert J, Journot L. Alternative splicing in the N-terminal extracellular domain of the pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide (PACAP) receptor modulates receptor selectivity and relative potencies of PACAP-27 and PACAP-38 in phospholipase C activation. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1996;271:22146–22151. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.36.22146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pathak N, Johnson P, Getman M, Lane R. Odorant receptor (OR) gene choice is biased and non-clonal in two olfactory placodal cell lines, and OR RNA is nuclear prior to differentiation of these cell lines. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2009;108:486–497. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05780.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Regad T, Roth M, Bredenkamp N, Illing N, Papalopulu N. The neural progenitor-specifying activity of FoxG1 is antagonistically regulated by CK1 and FGF. Nature Cell Biology. 2007;9:531–540. doi: 10.1038/ncb1573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reglodi D, Lubics A, Tamas A, Szalontay L, Lengvari I. Pituitary adenylate cyclase activating polypeptide protects dopaminergic neurons and improves behavioral deficits in a rat model of Parkinson's disease. Behavioural Brain Research. 2004;151:303–312. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2003.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shioda S, Ohtaki H, Nakamachi T, Dohi K, Watanabe J, Nakajo S, Arata S, Kitamura S, Okuda H, Takenoya F, Kitamura Y. Pleiotropic functions of PACAP in the CNS: neuroprotection and neurodevelopment. Ann.N.Y.Acad.Sci. 2006;1070:550–560. doi: 10.1196/annals.1317.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Spengler D, Waeber C, Pantaloni C, Holsboer F, Bockaert J, Seeburg PH, Journot L. Differential signal transduction by five splice variants of the PACAP receptor. Nature. 1993;365:170–175. doi: 10.1038/365170a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Suzuki Y, Farbman AI. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha-induced apoptosis in olfactory epithelium in vitro: possible roles of caspase 1 (ICE), caspase 2 (ICH-1), and caspase 3 (CPP32) Experimental Neurology. 2000;165:35–45. doi: 10.1006/exnr.2000.7465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Unal-Cevik I, Kilinc M, Can A, Gursoy-Ozdemir Y, Dalkara T. Apoptotic and necrotic death mechanisms are concomitantly activated in the same cell after cerebral ischemia. Stroke. 2004;35:2189–2194. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000136149.81831.c5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ushiyama M, Ikeda R, Sugawara H, Yoshida M, Mori K, Kangawa K, Inoue K, Yamada K, Miyata A. Differential intracellular signaling through PAC1 isoforms as a result of alternative splicing in the first extracellular domain and the third intracellular loop. Molecular Pharmacology. 2007;72:103–111. doi: 10.1124/mol.107.035477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vaudry D, Falluel-Morel A, Bourgault S, Basille M, Burel D, Wurtz O, Fournier A, Chow BK, Hashimoto H, Galas L, Vaudry H. Pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide and its receptors: 20 years after the discovery. Pharmacol.Rev. 2009;61:283–357. doi: 10.1124/pr.109.001370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vaudry D, Pamantung TF, Basille M, Rousselle C, Fournier A, Vaudry H, Beauvillain JC, Gonzalez BJ. PACAP protects cerebellar granule neurons against oxidative stress- induced apoptosis. European Journal of Neuroscience. 2002a;15:1451–1460. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2002.01981.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vaudry D, Rousselle C, Basille M, Falluel-Morel A, Pamantung TF, Fontaine M, Fournier A, Vaudry H, Gonzalez BJ. Pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide protects rat cerebellar granule neurons against ethanol-induced apoptotic cell death. Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.U.S.A. 2002b;99:6398–6403. doi: 10.1073/pnas.082112699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Villalba M, Bockaert J, Journot L. Pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide (PACAP-38) protects cerebellar granule neurons from apoptosis by activating the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAP kinase) pathway. Journal of Neuroscience. 1997;17:83–90. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-01-00083.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Waschek JA. Multiple actions of pituitary adenylyl cyclase activating peptide in nervous system development and regeneration. Developmental Neuroscience. 2002;24:14–23. doi: 10.1159/000064942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.