Abstract

Corneal epithelial abrasion elicits an inflammatory response involving neutrophil (PMN) recruitment from the limbal vessels into the corneal stroma. These migrating PMNs make surface contact with collagen and stromal keratocytes. Using mice deficient in PMN integrin CD18, we previously showed that PMN contact with stromal keratocytes is CD18-dependent, while contact with collagen is CD18-independent. In the present study, we wished to extend these observations and determine if ICAM-1, a known ligand for CD18, mediates PMN contact with keratocytes during corneal wound healing. Uninjured and injured right corneas from C57Bl/6 wild type (WT) mice and ICAM-1−/− mice were processed for transmission electron microscopy and imaged for morphometric analysis. PMN migration, stromal thickness, and ICAM-1 staining were evaluated using light microscopy. Twelve hours after epithelial abrasion, PMN surface contact with paralimbal keratocytes in ICAM-1−/− corneas was reduced to ~50% of that observed in WT corneas; PMN surface contact with collagen was not affected. Stromal thickness (edema), keratocyte network surface area and keratocyte shape were similar in ICAM-1−/− and WT corneas. WT keratocyte ICAM-1 expression was detected at baseline and ICAM-1 staining intensity increased following injury. Since ICAM-1 is readily detected on mouse keratocytes and PMN-keratocyte surface contact in ICAM-1−/− mice is markedly reduced, the data suggest PMN adhesive interactions with keratocyte stromal networks is in part regulated by keratocyte ICAM-1 expression.

Keywords: cornea, inflammation, wound healing, neutrophils (PMNs), keratocytes, adhesion molecules

1. Introduction

Corneal epithelial abrasion, resulting from physical damage or refractive surgery, elicits an inflammatory response (Belmonte, C., et al., 2004, Burns, A. R., et al., 2005, Chinnery, H. R., et al., 2009, Hamrah, P., et al., 2003, Li, Z., et al., 2006a, Li, Z., et al., 2006b, O'Brien, T. P., et al., 1998, Pearlman, E., et al., 2008, Wilson, S. E., et al., 2001) characterized by an acute recruitment of neutrophils (PMNs) into the stroma (Burns, A. R. et al., 2005, Li, Z. et al., 2006a, Li, Z. et al., 2006b, Wilson, S. E. et al., 2001). Li and colleagues showed PMN emigration from limbal vessels is facilitated by leukocyte-specific Beta (β)-2 integrin, CD18. Furthermore, they showed that the total absence of CD18, or absence of specific CD18 family members (CD11a/CD18-LFA-1 or CD11b/CD18-Mac-1), not only delayed entry of PMNs into the stroma but also significantly delayed wound closure (Li, Z. et al., 2006a, Li, Z. et al., 2006b).

PMN transendothelial migration in the systemic circulation is well known to be regulated by CD18 integrins (Carlos, T. M. & Harlan, J. M., 1994, Jaeschke, H. & Smith, C. W., 1997, Ley, K., 2001, Phillipson, M., et al., 2006). Most recently, in response to central corneal epithelial abrasion, we identified a novel extravascular role for CD18 during PMN migration through the corneal interstitium (Petrescu, M. S., et al., 2007). We observed that PMNs preferentially infiltrate the anterior stroma and migrate within the interlamellar spaces where they make close surface contacts with the surrounding collagen and paralimbal keratocytes. Close contact with keratocytes requires CD18 while contact with collagen does not. It is well known that keratocytes form a cellular network and we suggested keratocytes function as a "cellular highway" for CD18-dependent PMN migration within the stroma. The identity of the CD18-ligand expressed on the keratocyte was not determined.

It is well established that endothelial intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) plays a key role during inflammation, serving as a ligand for CD18 integrins and thereby facilitating PMN recruitment (Brake, D. K., et al., 2006, Burns, A. R., et al., 1994, Ley, K., 1996, Moreland, J. G., et al., 2002, Oberyszyn, T. M., et al., 1998). ICAM-1 is a five-domain transmembrane 4 glycoprotein that binds to PMN integrin CD11a/CD18 at domain one and CD11b/CD18 at domain three (Diamond, M. S., et al., 1993, Huang, C. & Springer, T. A., 1995, Lynam, E., et al., 1998, Roebuck, K. A. & Finnegan, A., 1999, Smith, C. W., et al., 1989). In vitro and in vivo studies of the cornea show that ICAM-1 is expressed on epithelial cell (Byeseda, S. E., et al., 2009, Hobden, J. A., et al., 1995, Kumagai, N., et al., 2003, Li, Z., et al., 2007, Liang, H., et al., 2007, Yannariello-brown, J., et al., 1998), keratocytes (Hobden, J. A. et al., 1995, Kumagai, N. et al., 2003, Liang, H. et al., 2007, Pavilack, M. A., et al., 1992, Seo, S. K., et al., 2001), and endothelial cells (Elner, V. M., et al., 1991, Hobden, J. A. et al., 1995, Pavilack, M. A. et al., 1992). We and others have observed increased ICAM-1 staining on mouse corneal epithelial cells following epithelial abrasion or Pseudomonas infection (Byeseda, S. E. et al., 2009, Hobden, J. A. et al., 1995, Li, Z. et al., 2007, Li, Z. et al., 2006a). With respect to the corneal keratocyte, in vitro studies of human corneal explants show increased levels of ICAM-1 staining after cytokine treatment (Pavilack, M. A. et al., 1992). In the mouse, baseline immunostaining for keratocyte ICAM-1 reportedly increases in vivo after Pseudomonas infection (Hobden, J. A. et al., 1995) but whether it increases after simple epithelial abrasion is unknown. Furthermore, it remains to be determined if ICAM-1 expression on mouse keratocytes mediates PMN close surface contact with keratocytes.

The purpose of this study is to evaluate the relative contribution of ICAM-1 to PMN stromal migration by determining if close surface contact between migrating PMNs and stromal keratocytes is ICAM-1-dependent.

2. Methods

2.1 Animals

Male C57Bl/6 wild type mice (WT) were purchased from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME) and bred at Baylor College of Medicine animal housing facilities. ICAM-1−/− mice (Byeseda, S. E. et al., 2009) were backcrossed at least 10 generations with C57Bl/6 mice. Twenty-eight mice (n=14 of each strain), ages 6 to 10 weeks, were used in this study. All animals were treated according to the guidelines described in the ARVO Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research and Baylor College of Medicine Animal Care and Use Committee policy.

2.2 Wound Protocol

Pentobarbital (Nembutal; Ovation Pharmaceuticals, Deerfield, IL) was administered intraperitoneally (50 mg/kg body weight) to anesthetize the mice. A 2 mm diameter trephine was used to demarcate the central epithelial region of the right eye and the epithelium within the demarcated region was mechanically removed using an Algerbrush II (Alger Equipment Co., Inc., Lago Vista, TX) under a dissecting microscope.

2.3 Immunohistochemistry

For histologic studies, WT and ICAM-1−/− mice were humanely euthanized (1-chloro-2,2,2-trifluoroethyldifluoromethyl ether-Isofluorane inhalation followed by cervical dislocation) and the eyes were enucleated. Corneas were excised from ICAM-1−/− and WT mice and incubated at 37 degrees Celsius for 30 minutes. Epithelial sheets were removed and corneas were fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde (Tousimus Research Corporation, Rockville, MD) in 0.1M phosphate buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.2) at 4 degrees Celsius for 60 minutes, blocked with PBS with 2% bovine serum albumin (BSA), and permeabilized with 0.1% Triton-X. Radial cuts were made from the peripheral edge to the paracentral region. Uninjured and 12 hour injured corneas (a time point when PMN stromal infiltration is underway;(Li, Z., et al., 2006c)) were incubated with unconjugated rabbit anti-ALDH3A1 antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Santa Cruz, CA) overnight at 4 degrees Celsius. All corneas were washed three times with PBS/2% BSA and incubated overnight with goat-anti-rabbit Cy5 conjugated secondary IgG (Abcam, San Francisco, CA) to identify ALDH3A1-positive keratocytes, PE conjugated anti-ICAM-1 antibody (clone YN-1, Abcam, San Francisco, CA) to evaluate ICAM-1 expression on keratocytes, FITC conjugated Ly6-G antibody to detect PMNs (BD Bioscience, Pharmingen, San Jose, CA), and DAPI (4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole, Sigma, St. Louis, MO) to detect nuclei. Separate 12 hour injured corneas were stained with a PE conjugated antibody against Thy1.2 (Ishihara, A., et al., 1987, Pei, Y., et al., 2004)(BD Bioscience, Pharmingen, San Jose, CA), a fibroblast marker, and FITC conjugated antibody against alpha-smooth muscle actin, a myofibroblast marker (Jester, J. V., et al., 1995, Yoshida, S., et al., 2005)(Sigma, St. Louis, MO). A third set of uninjured and injured corneas served as control for non-specific antibody staining and was incubated with the appropriate isotype matched non-immune IgG antibodies. All corneas were mounted in AIRVOL mounting media (Celanese, Dallas, TX). Images through the full thickness of the paralimbal corneal region, immediately central and adjacent to the limbus, were obtained using a DeltaVision Core inverted microscope (Applied Precision, Issaquah, WA) and processed using SoftWorx software.

2.4 Electron Microscopy

2.4.1 Tissue processing

Whole uninjured and injured mouse eyes were fixed in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer (pH 7.2) containing 2.5% glutaraldehyde for 2 hours at room temperature. Fixed eyes were rinsed in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer and stored at 4 degrees Celsius until further processing. Corneas, with the limbus intact, were carefully excised from the whole eye and cut into four equal-sized quadrants. These quadrants were post-fixed in 1% tannic acid for 5 minutes and transferred to 1% osmium tetroxide. Specimens were then dehydrated through an acetone series and embedded in resin (EMbed-812, Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatsfield, PA). Thin plastic sections (80 to 100 nm) were cut and imaged on a JEOL 200CX (Tokyo, Japan) electron microscope or a Tecnai G2 Spirit BioTWIN (FEI Company, Hillsboro, OR) electron microscope.

2.4.2 Morphometric Analysis

Morphometric analyses using stereological techniques were performed, as previously described (Petrescu, M. S. et al., 2007), to quantify the percentage of PMN membrane in close contact with stromal structures (keratocytes, other PMNs and collagen) and determine keratocyte network size and surface area. Stereology, a well-established technique, is used for analyzing two-dimensional images (e.g., tissue sections) to obtain unbiased and accurate estimates of geometrical features including feature number, length, surface area, and volume. It has been used extensively over the past 40 years in the study of biological structures (Anderson, H. R., et al., 1994, Gibbons, C. H., et al., 2009, Howard, C. & Reed, M., 1998, Knust, J., et al., 2009, Mahon, G. J., et al., 2004, Michel, R. P. & Cruz-Orive, L. M., 1988, Petrescu, M. S. et al., 2007, Schmitz, C. & Hof, P. R., 2005, Weibel, E. R., 1981), including the cornea (Petrescu, M. S. et al., 2007) and retina (Anderson, H. R. et al., 1994, Mahon, G. J. et al., 2004). Briefly, electron micrographs were recorded from the anterior and posterior paralimbal regions. To avoid observer sampling bias, systematic uniform random sampling (SURS) (Howard, C. & Reed, M., 1998, Petrescu, M. S. et al., 2007) of PMNs, keratocytes, and collagen lamellae were obtained by imaging the paralimbal corneal region in a rasterized pattern. Digital images were analyzed in Adobe Photoshop (Adobe Systems Inc., San Jose, CA) using a cycloid grid. The grid consisted of a sinusoidal wave pattern with regularly spaced target points which were randomly cast over the digital images using the layer function in Photoshop; the orientation of the grid was fixed in a direction perpendicular to the direction of the collagen lamellae (Fig 1A) to account for the anisotropic properties of the corneal stroma.

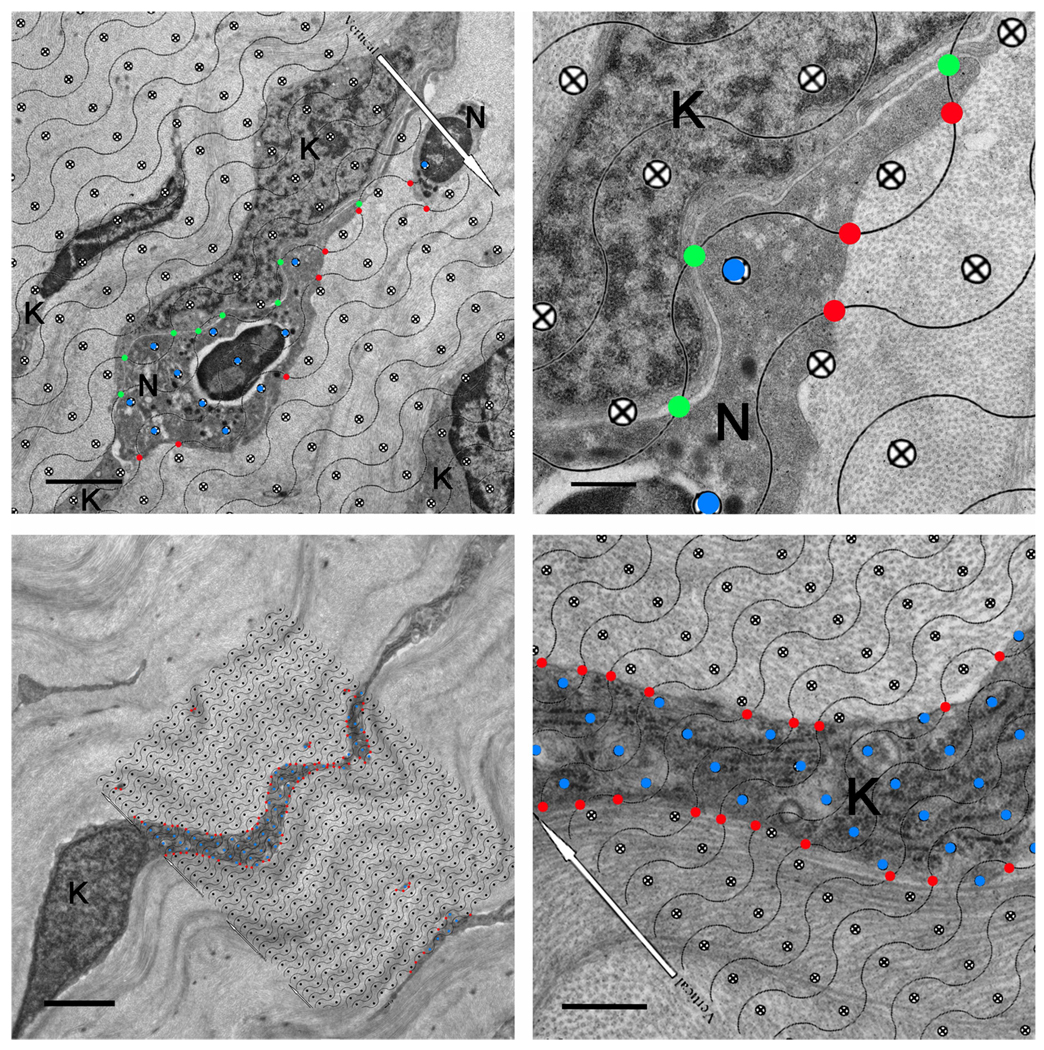

Fig 1.

Morphometric measurements of PMN-keratocyte interaction and keratocyte surface-to-volume ratio (Sv) using a cycloid grid. Panel A shows a systematically, randomly cast cycloid grid placed on top of a corneal cross section (WT 12 hours post-injury). The white arrow on the cycloid grid is oriented perpendicular to the longitudinally oriented collagen fibrils which run parallel to the orientation of the cycloid grid lines. Grid lines intersecting PMN-keratocyte membrane interfaces separated by distances of ≤ 25 nm are marked as close surface contacts (green points). Points falling within the PMN body are scored for volume measurements (blue points). PMN-collagen close interactions (≤ 25 nm) are indicated by red points. Panel B is a magnified image of panel A and shows areas of PMN close surface contact with keratocyte and collagen. Colored points are more easily appreciated at this magnification. Panel C shows a cycloid grid overlaid on top of uninjured WT anterior paralimbal keratocytes. Again, the white arrows on the cycloid grid are oriented perpendicular to the overall longitudinal orientation of the collagen fibrils. Here, the red points are placed at the intersections of grid lines and keratocyte membrane and blue points falling within the keratocyte body are used to calculate the keratocyte surface-to-volume ratio (Sv), an indirect measurement of shape. Panel D is a magnified image of panel C where the red points intersecting the grid line-membrane interface and blue points within the keratocyte body can be better appreciated. Additional symbols: N=PMN, K=keratocyte. Scale bar: 2 µm (A, C), 0.5 µm (B, D).

Cycloid grid lines intersecting the PMN plasma membrane at PMN-keratocyte or PMN-collagen associations where the membrane-membrane or membrane-collagen separation was ≤25 nm were recorded as close contact (Fig 1A–B). This value defines the predicted length of an integrin-ligand association required to mediate cell adhesion (Springer, T. A., 1990). Distances greater than 25 nm were considered as PMN association with interlamellar space. Grid target points falling within the PMN body were also recorded (Fig 1A–B). Grid lines intersecting the keratocyte membrane and grid target points falling within the keratocyte cell body were recorded for morphometric analysis of the keratocyte network (Fig 1C–D). The ratio between lines on the cycloid grid intersecting the surface of a cell and the target points on the grid which lie within the cell body was used to calculate cell surface density, or Sv (surface-to-volume ratio). Using an established formula (Howard, C. & Reed, M., 1998, Petrescu, M. S. et al., 2007), Sv = (2•ΣI)/(l/p•ΣP), where I is defined by the number of times the cycloid lines intersecting the interface of PMN-keratocyte, PMN-collagen, and PMN-PMN interactions or PMN-interlamellar space associations and P is the number of cycloid grid points within the PMN body, the amount of PMN surface (i.e. percentage of Sv) in contact with keratocytes, collagen, with neighboring PMNs, or associated with interlamellar space was acquired. Sv is an indirect measure of shape; thus, the same formula can be used to obtain an estimate of keratocyte network shape (Sv). Keratocyte network surface area (SA) can then be derived by multiplying Sv by the volume of the paralimbal stromal keratocytes. To obtain the volume of the paralimbal stromal keratocytes, the number of grid target points falling on keratocytes is divided by the number of points falling on the stroma. This ratio is then multiplied by the known reference volume of the paralimbal corneal stroma which is obtained by multiplying the paralimbal width of 530 µm (Petrescu, M. S. et al., 2007) by the thickness of the paralimbal stroma (see below).

2.5 Corneal Thickness Measurements

Thick cross sections (0.5 µm) from corneas prepared for electron microscopy were stained with 1% toluidine blue O and examined by light microscopy using a 40× objective. For each cornea, three separate perpendicular measurements, laterally separated by 50 µm, were made from the basement membrane of the epithelium to the top of Decemet’s membrane at the paralimbal region of the corneal cross section. The mean measurement was reported as the corneal paralimbal stromal thickness.

2.6 Statistical Analysis

Data analyses were performed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by a Newman-Keuls Multiple Comparison post test. A p value <0.05 was considered significant. Data are reported as means ± SEM.

3. Results

3.1 Paralimbal keratocyte phenotype is retained after central epithelial abrasion

The corneal crystalline aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) 3A1 is a marker for undifferentiated mammalian keratocytes (Jester, J. V., 2008, Stagos, D., et al., Pei, Y. et al., 2006, Yoshida, S. et al., 2005) and is not present on keratocytes that have differentiated into fibroblasts and myofibroblasts. Paralimbal stromal cells from uninjured and injured WT and ICAM-1−/− corneas stained positively with anti-ALDH3A1 antibody (Figs 2B,F, J and N). In addition, uninjured and injured WT and ICAM-1−/− corneas stained with antibodies against Thy1.2 (fibroblast marker) and alpha smooth muscle actin (myofibroblast marker) did not show staining on any stromal cells within the paralimbus (data not shown). Collectively, the data suggest epithelial abrasion does not cause keratocyte differentiation during the first 12 hours post-injury.

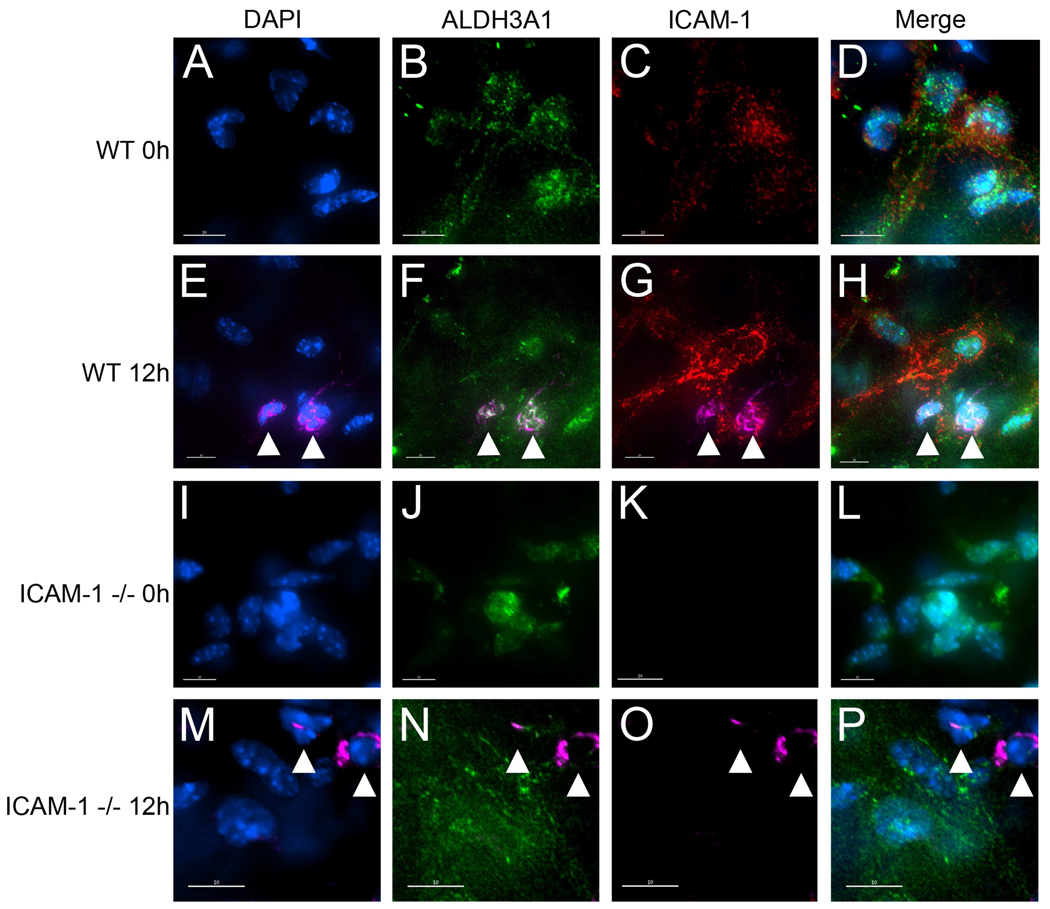

Fig 2.

Expression of ICAM-1 on ALDH3A1 positive WT and ICAM-1−/− mouse keratocytes. Uninjured (0h) and injured (12h) mouse corneas from WT and ICAM-1−/− mice were prepared for immunofluorescence staining as described in Methods and images were pseudocolored. Corneas were labeled with a nuclear stain DAPI (blue) and antibodies against ALDH3A1, a keratocyte marker (green), ICAM-1 (red) and LY6G, a PMN marker (pink). White arrowheads denote presence of PMNs. Scale bars: 10 µm.

3.2 ICAM-1 expression on mouse keratocytes

ICAM-1 expression is upregulated on keratocytes during corneal infections, as demonstrated in rabbits and mice (Liang, H. et al., 2007, Pavilack, M. A. et al., 1992, Seo, S. K. et al., 2001). However, to our knowledge, the expression of ICAM-1 on mouse keratocytes following epithelial abrasion has not been reported. PE conjugated antibody against mouse ICAM-1 (clone YN-1) was used to determine the relative expression of ICAM-1 on uninjured and 12 hour injured WT corneal keratocytes. Uninjured and 12 hour injured ICAM-1−/− corneas were also incubated with the YN-1 antibody to confirm the absence of ICAM-1 in the knockout genotype. To validate that ICAM-1-positive cells were indeed keratocytes, all corneas were dual-stained with ALDH3A1. Immunostaining of uninjured WT corneas revealed that ICAM-1 was expressed at baseline levels (Fig 2C) on ALDH3A1 positive keratocytes (Fig 2B and 2D). The intensity of ICAM-1 staining was markedly increased on ALDH3A1 positive WT keratocytes 12 hours post-injury (Figs 2F–H), suggesting keratocyte ICAM-1 protein is upregulated after epithelial debridement. Furthermore, PMNs in the stroma were found in close proximity to paralimbal keratocytes (Figs 2E–H). As expected, neither the uninjured nor the 12 hour injured ICAM-1−/− corneas stained positively for ICAM-1 (Figs 2K and 2O, respectively), whereas PMNs were readily detected in the ICAM-1−/− corneal stroma 12 hour after injury (Figs 2M–P). Non-specific antibody binding using appropriate non-immune antibodies was negligible (data not shown). Thus, we confirm that stromal paralimbal keratocytes in the mouse stain positively for ICAM-1 and show for the first time that keratocyte ICAM-1 staining increases after simple epithelial abrasion.

3.3 Morphometric Analysis

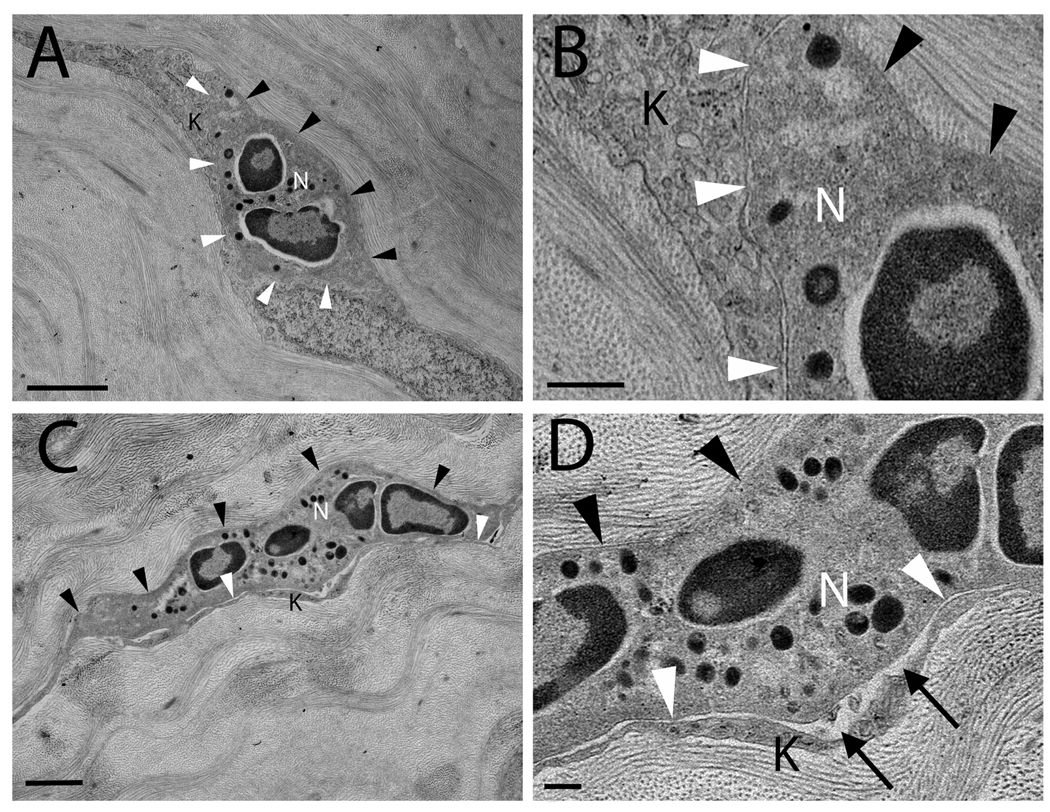

Following corneal epithelial abrasion, PMNs preferentially infiltrate the anterior aspect of the stroma as early as 6 hours and by 12 hours there is a substantial influx of PMNs into the WT cornea (Li, Z. et al., 2006b). PMNs first enter the paralimbal region of the cornea, the area immediately central and adjacent to the limbus (Petrescu, M. S. et al., 2007). Previously, Li and colleagues showed that although peak limbal PMN infiltration is delayed by 6 hours in ICAM-1−/− mice compared to WT mice, both genotypes have substantial PMN infiltration 12 hours after epithelial abrasion (Li, Z. et al., 2006c). Moreover, in this study, electron micrographs clearly demonstrate the presence of PMNs in both WT and ICAM-1−/− mouse paralimbal stroma 12 hours after injury (Figs 3A–D). In the paralimbal stroma of the WT corneas, PMNs made close surface contact with both stromal collagen and keratocytes (Fig 3A–B). In contrast, PMNs migrating through the stroma of ICAM-1−/− corneas appeared to have fewer close contacts with keratocytes, but remained in close contact with collagen (Fig 3C–D).

Fig 3.

Transmission electron micrographs of 12 hour injured corneas in wild type (A, B) and ICAM-1−/− (C, D) mice. (A) WT PMNs (12 hours post-injury) come into close contact with collagen (black arrowheads) and keratocytes (white arrowheads). Close contact is defined by any distance ≤ 25 nm between the surface of a PMN and an adjacent surface (e.g. collagen or keratocyte). (B) A magnified view of (A) shows close contact between PMN and keratocyte membrane surfaces. (C) In the ICAM-1−/− cornea (12 hours post-injury), the PMN shows close surface contact with collagen (black arrowheads) but surface contacts with keratocytes (white arrowheads) are less evident and (D) the distance between PMN and keratocyte surfaces frequently exceeds 25 nm (black arrows). Additional symbols: N = PMN, K = keratocyte. Scale bars: 2 µm (A, C), 0.5 µm (B, D).

Table 1 summarizes the morphometric results of PMN close surface contact with keratocytes and collagen in the presence and absence of ICAM-1. Twelve hours after injury, in the presence of ICAM-1 on the surface of keratocytes (WT corneas), ~ 50% of the PMN surface was in close contact with surrounding collagen while ~ 40% of the PMN surface was in close contact with a neighboring keratocyte (Table 1). These results agree with our previous findings in WT corneas 6 hours after injury and show that as a PMN migrates through the interlamellar space in the paralimbal cornea, approximately half of its surface contacts collagen while the remainder of its surface is in close contact with keratocytes (Petrescu, M. S. et al., 2007). In the ICAM-1−/− corneas, ~ 60% of the PMN surface came into close contact with collagen (Table 1). This estimation was not statistically different from that of WT. However, PMN-keratocyte interactions in ICAM-1−/− corneas were significantly reduced by 50% compared to WT estimates (p < 0.05; Table 1). Infiltrating PMNs also encounter neighboring PMNs and interlamellar space while migrating through the stroma. These interactions account for the remaining PMN associations within the stroma (Table 2). As expected, PMN associations with interlamellar space (where the distance between the PMN membrane and the nearest cell membrane or collagen fibril is >25 nm) increase significantly in ICAM-1−/− corneas while PMN-keratocyte surface contacts decrease, clearly demonstrating that PMN close surface contact with keratocytes is dependent on ICAM-1 (Petrescu, M. S. et al., 2007).

Table 1.

Percent of PMN Surface in Close Contact (≤25 nm) with Keratocytes or Collagen in the Paralimbal Region of Injured Corneas

| Genotype | Contact with Keratocytes (%) | Contact with Collagen (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Wild Type, n=5 | 39.9 ± 3.5 | 51.3 ± 3.4 |

| ICAM-1−/−, n=5 | 21.5 ± 3.0* | 59.1 ± 2.0 |

p < 0.05 compared to wild type.

Data are means ± SEM.

Table 2.

Percent of PMN Surface in Close Contact (≤ 25 nm) with Neighboring PMN(s) or Associated with Interlamellar Space (% Sv> 25 nm).

| Genotype | PMN-PMN (% Sv ≤ 25 nm) |

PMN-Interlamellar Space (% Sv > 25 nm) |

|---|---|---|

| Wild Type, n=5 | 0.4 ± 0.4 | 8.4 ± 2.8 |

| ICAM-1−/−, n=5 | 1.6 ± 1.0 | 17.8 ± 2.3* |

p < 0.05 compared to wild type.

Data are means ± SEM.

To exclude the possibility that the reduction in PMN contact with keratocytes observed in ICAM-1−/− mice was due to some factor other than a lack of ICAM-1, it was necessary to verify that the keratocyte network shape, amount of keratocyte network surface area, and degree of stromal swelling (edema) was comparable in ICAM-1−/− and WT mice. Any or all of these factors could impose changes in the keratocyte-stromal environment that could result in decreased PMN contact with keratocytes, independent of a contribution from ICAM-1.

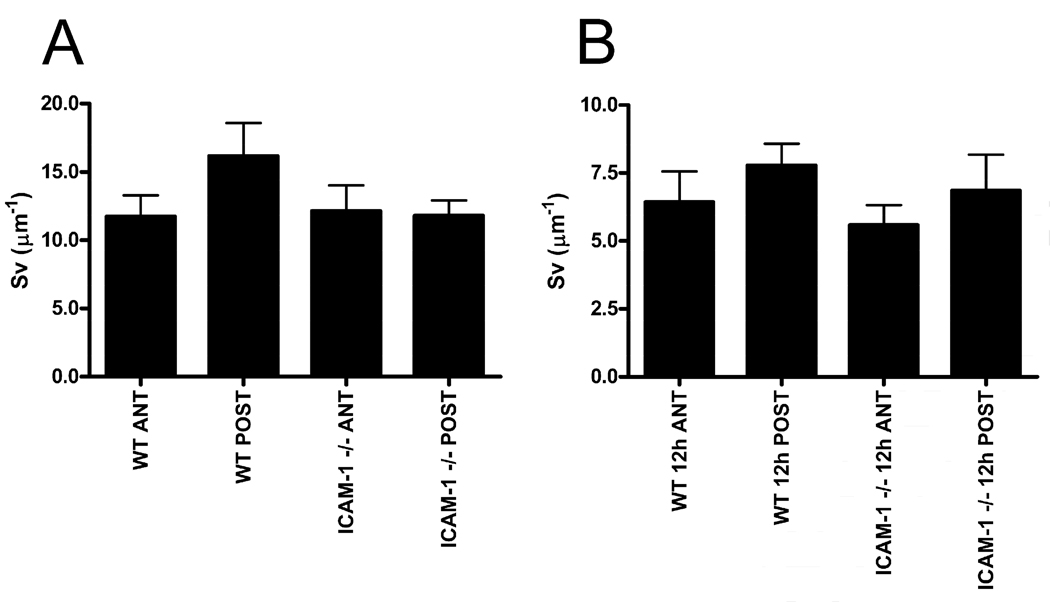

First we determined if there were any differences in keratocyte network shape. An indirect estimate of keratocyte network shape is given by its surface-to-volume ratio (Sv). Morphometric analysis of Sv (see methods) showed that there was no difference in keratocyte network shape prior to injury (baseline) in the anterior or posterior aspect of the cornea for WT and ICAM-1−/− mice (Fig 4A; p=0.2741). Moreover, twelve hours after injury, when PMNs are migrating within the paralimbal stroma, the keratocyte Sv ratio was not different between genotypes (Fig 4B; p=0.5119). Hence, in ICAM-1−/− mice, there are no mouse strain-specific changes in keratocyte network shape after injury that could account for the reduction in PMN surface contact with keratocytes.

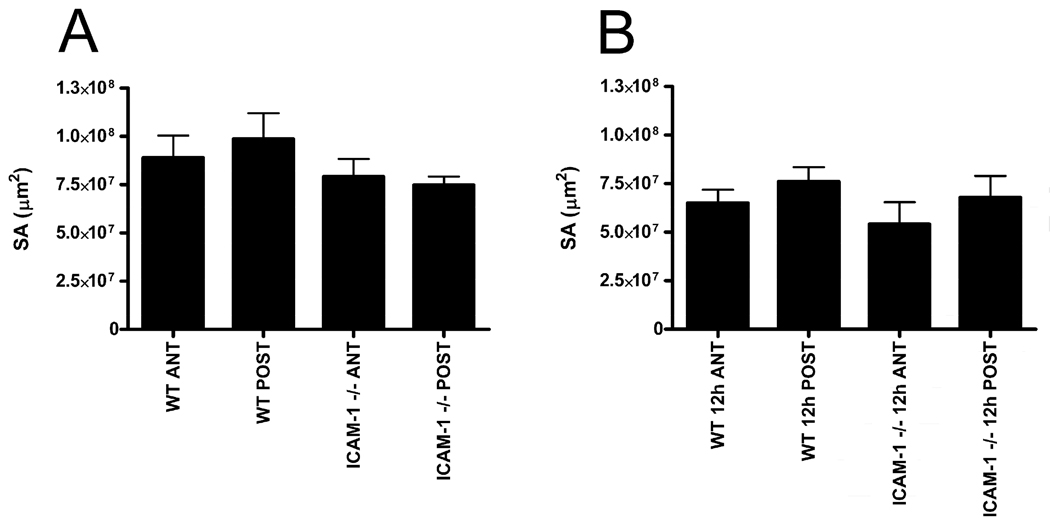

Fig 4.

Surface-to-volume ratio of paralimbal keratocytes of uninjured (A) and 12 hour injured (B) corneas. Both anterior (ANT) and posterior (POST) regions of WT and ICAM-1−/− corneas are evaluated. Data are means ± SEM.

Keratocyte network surface area (SA) is the amount of surface available on the network itself with which a PMN can closely associate. A mouse strain-specific decrease in network SA as a result of injury could potentially explain a reduction in PMN-keratocyte close surface contact observed in the absence of ICAM-1. At baseline levels, there was no difference between anterior or posterior keratocyte network SA within a given genotype and no difference between the two genotypes of mice (Fig 5A; p=0.3765). Similarly, 12 hours post injury when PMNs are migrating, there was no strain-specific difference in network SA for anterior and posterior paralimbal keratocytes within a genotype and no difference between genotypes (Fig 5B; p=0.4452). Hence, in ICAM-1−/− mice, there are no mouse strain-specific changes in keratocyte network SA that could account for the reduction in PMN-keratocyte close surface interactions.

Fig 5.

Paralimbal keratocyte network surface area of uninjured (A) and 12 hour injured (B) corneas for WT and ICAM-1−/− mice. Both anterior (ANT) and posterior (POST) regions are evaluated. Data are means ± SEM.

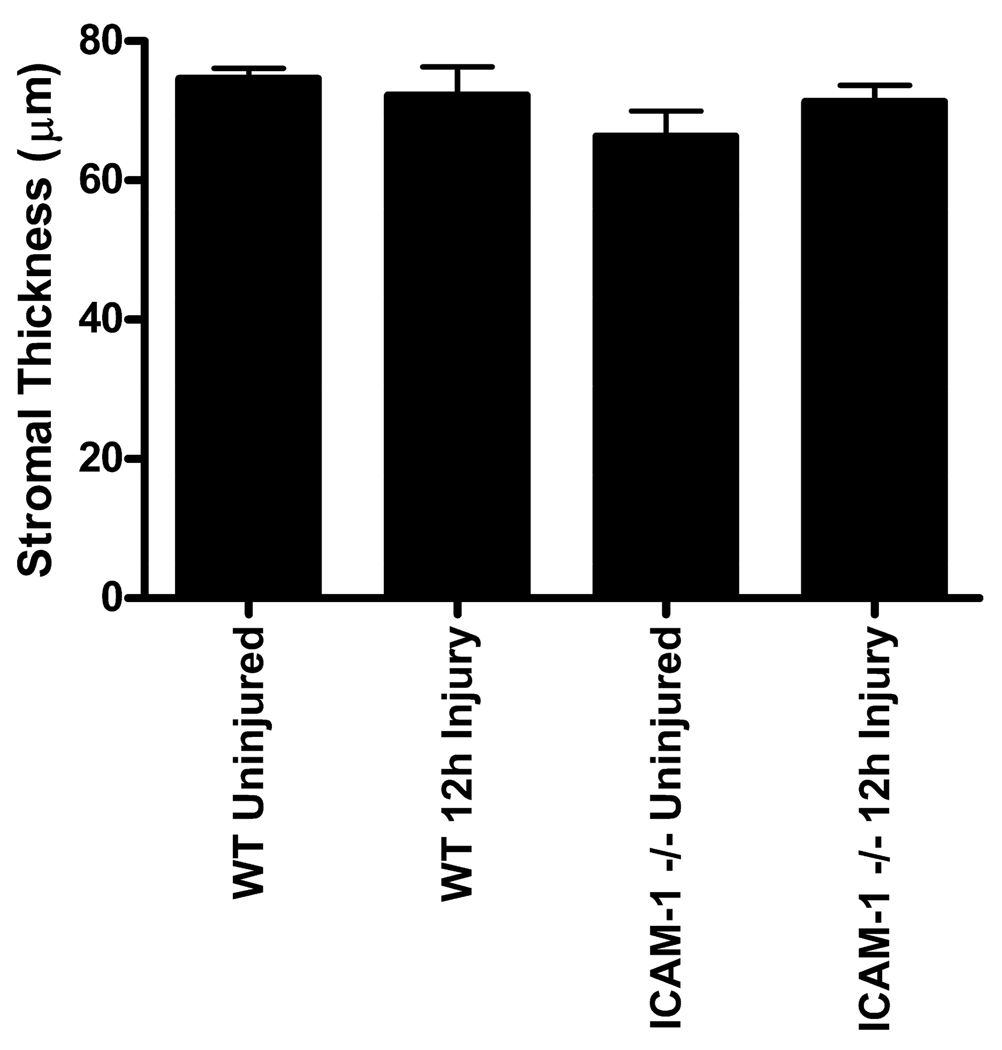

Finally, corneal epithelial abrasion in the mouse can result in stromal edema (Petrescu, M. S. et al., 2007). Corneal swelling is associated with interlamellar separation and if swelling was more severe in the ICAM-1−/− mice, it could result in less PMN contact with keratocytes. Since our analysis focused solely on the paralimbal region, which was not directly injured, we wanted to verify whether edema extended into the paralimbus and whether there was any difference in corneal swelling between WT and ICAM-1−/− mice. Our results show that there was no significant difference in total stromal thickness between uninjured and 12 hour injured WT and ICAM-1−/− corneas in the paralimbal region (Fig 6; p=0.3301). Hence, paralimbal stromal edema is not a prominent feature of WT or ICAM-1−/− corneas at 12 hours post-injury. Moreover, enhanced stromal edema in ICAM-1−/− mice is not a reasonable explanation for the reduction of PMN and paralimbal keratocyte close surface contact.

Fig 6.

Paralimbal stromal thickness of uninjured and 12 hour injured WT and ICAM-1−/− mouse corneas. Data are means ± SEM.

4. Discussion

The purpose of this study was 1) to confirm that ICAM-1 is expressed on mouse keratocytes in our epithelial debridement model and 2) to determine if ICAM-1 contributes to PMN-keratocyte close surface contact during the corneal inflammatory response. In our model of injury, epithelial abrasion is a non-stromal penetrating injury associated with an acute corneal inflammatory response (Li, Z. et al., 2007, Li, Z. et al., 2006a, Li, Z. et al., 2006b, Li, Z. et al., 2006c, Petrescu, M. S. et al., 2007) and death of underlying central keratocytes (Wilson, S. E., et al., 1996, Zhao, J. & Nagasaki, T., 2004, Zieske, J. D., et al., 2001). However, at least for the first 12 hours post-injury, keratocytes in the paralimbus, a region distal to the site of injury, remain viable and do not express fibroblast or myofibroblast differentiation markers (Thy1.2 or alpha smooth muscle actin, respectively), but do express ALDH3A1 (Fig 2), a marker for undifferentiated mammalian keratocytes (Jester, J. V., 2008, Stagos, D., et al., Pei, Y. et al., 2006 Yoshida, S. et al., 2005). Immunostaining for ICAM-1 reveals baseline ICAM-1 expression on uninjured mouse keratocytes, and 12 hours after injury the intensity of the ICAM-1 staining increases. Others have reported low expression of keratocyte ICAM-1 in mice (Hobden, J. A. et al., 1995) and this expression increases following LPS stimulation (Seo, S. K. et al., 2001) or bacterial infection (Hobden, J. A. et al., 1995). We now report that ICAM-1 expression also increases on mouse keratocytes following central corneal epithelial abrasion, an injury not associated with bacterial infection. More importantly, our studies with ICAM-1−/− mice show that PMN close surface contact with paralimbal keratocytes is significantly reduced in the absence of keratocyte ICAM-1.

ICAM-1 has a well defined “intravascular” role in regulating PMN recruitment at sites of inflammation (Brake, D. K. et al., 2006, Carlos, T. M. & Harlan, J. M., 1994, Jaeschke, H. & Smith, C. W., 1997, Ley, K., 1996, Ley, K., 2001, Moreland, J. G. et al., 2002, Oberyszyn, T. M. et al., 1998, Phillipson, M. et al., 2006). Specifically, the association of endothelial ICAM-1 and PMN CD18 allows for firm adhesion of PMNs to the blood vessel wall, a pre-requisite for efficient transendothelial migration (Jaeschke, H. & Smith, C. W., 1997, Ley, K., 1996, Ley, K., 2001, Moreland, J. G. et al., 2002, Oberyszyn, T. M. et al., 1998, Phillipson, M. et al., 2006). We now provide data showing that ICAM-1 also has an “extravascular” role in regulating PMN contact with corneal keratocytes. Our observation of increased keratocyte ICAM-1 expression during the corneal inflammatory process is consistent with the view that the binding of the leukocyte Beta-2 integrin (CD18) with keratocyte ICAM-1 facilitates PMN surface interactions with keratocytes. This finding is in line with an earlier study using excised human corneas which documented ICAM-1 staining on keratocytes and speculated stromal ICAM-1 may play a role in leukocyte localization (Pavilack, M. A. et al., 1992). Our ultrastructural stereologic findings are consistent with this concept and show that PMN close contact with stromal keratocytes is dependent upon the presence of ICAM-1.

In our previous study (Petrescu, M. S. et al., 2007), using the same corneal epithelial abrasion model, we found that in the absence of CD18, PMN-keratocyte interactions are reduced by 75% from that of WT. Utilizing the same wounding technique, we also see a significant reduction in PMN-keratocyte interactions in the absence of ICAM-1 (50% of WT). The reduction in surface contact by 50% as opposed to 75% as seen with the CD18−/− mice suggests the possible involvement of an additional CD18 ligand during PMN contact with paralimbal keratocytes. JAM-C is an adhesion molecule that also interacts with Cd11b/CD18 (Mac-1) during intravascular PMN transendothelial migration (Chavakis, T., et al., 2004). Morris et al. identified JAM-C expression on cultured human corneal fibroblasts (Morris, A. P., et al., 2006) and we have identified JAM-C mRNA expression on freshly isolated mouse keratocytes and staining for JAM-C is evident on cultured mouse keratocytes (unpublished results). Whether JAM-C is expressed on mouse keratocytes in vivo, and whether its expression pattern is altered by inflammation associated with epithelial abrasion remains to be determined.

Recent reports show the association of endothelial ICAM-1 with PMN CD18 triggers outside-in signaling events promoting sustained PMN adhesion to vascular endothelium (Wang, Q. & Doerschuk, C. M., 2002) and directing PMN transmigration at sites of inflammation (Sarantos, M. R., et al., 2008). Conceivably, this integrin-ligand binding may also trigger similar signaling events outside the limbal vasculature, through extravascular keratocyte ICAM-1 and extravasated PMN CD18 binding. While the existence of such signaling in the corneal stroma remains to be shown, preliminary studies in our laboratory suggest ICAM-1 negatively regulates keratocyte repopulation following epithelial abrasion. In our injury model, there is complete loss of keratocytes from the central anterior stroma directly beneath the site of injury. Keratocytes in the posterior central stroma do not appear to die. Keratocyte repopulation of the central anterior stroma occurs within 4 days post-injury and, in the absence of ICAM-1, the number of anterior central keratocytes recovers completely while WT anterior central keratocyte numbers fail to return to normal levels (unpublished results). Whether CD18-dependent PMN binding to keratocyte ICAM-1 promotes paralimbal keratocyte signaling events that negatively regulate the recovery of anterior central keratocytes remains to be determined.

In summary, the data show keratocyte ICAM-1 serves a novel extravascular role as a mediator of cell-cell contact, enabling PMNs to make close surface contact with keratocytes. This observation is entirely consistent with our previous finding that PMN contact with keratocytes also requires CD18. The fact that CD18 and ICAM-1 are well established receptor/ligand partners makes it reasonable to consider these two molecules as complementary partners of extravascular PMN adhesion to keratocytes. The addition of keratocyte ICAM-1 to the original concept that PMNs utilize CD18 to closely associate with the keratocyte network adds a new level of understanding to leukocyte recruitment in the injured cornea.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by the National Eye Institute grants EY018239, EY017120, P30EY007551 and grants 39970250 and 30672287 from the National Natural Science Foundation of China. The authors thank Margaret Gondo for providing excellent technical support.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Anderson HR, Stitt AW, Gardiner TA, Archer DB. Estimation of the surface area and volume of the retinal capillary basement membrane using the stereologic method of vertical sections. Anal Quant Cytol Histol. 1994;16(4):253–260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belmonte C, Acosta MC, Gallar J. Neural basis of sensation in intact and injured corneas. Exp Eye Res. 2004;78(3):513–525. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2003.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brake DK, Smith EO, Mersmann H, Smith CW, Robker RL. ICAM-1 expression in adipose tissue: effects of diet-induced obesity in mice. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2006;291(6):C1232–C1239. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00008.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns AR, Li Z, Smith CW. Neutrophil migration in the wounded cornea: the role of the keratocyte. Ocul Surf. 2005;3(4 Suppl):S173–S176. doi: 10.1016/s1542-0124(12)70249-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns AR, Takei F, Doerschuk CM. Quantitation of ICAM-1 expression in mouse lung during pneumonia. J Immunol. 1994;153(7):3189–3198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byeseda SE, Burns AR, Dieffenbaugher S, Rumbaut RE, Smith CW, Li Z. ICAM-1 is necessary for epithelial recruitment of gammadelta T cells and efficient corneal wound healing. Am J Pathol. 2009;175(2):571–579. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.090112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlos TM, Harlan JM. Leukocyte-endothelial adhesion molecules. Blood. 1994;84(7):2068–2101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavakis T, Keiper T, Matz-Westphal R, Hersemeyer K, Sachs UJ, Nawroth PP, Preissner KT, Santoso S. The junctional adhesion molecule-C promotes neutrophil transendothelial migration in vitro and in vivo. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(53):55602–55608. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404676200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinnery HR, Carlson EC, Sun Y, Lin M, Burnett SH, Perez VL, McMenamin PG, Pearlman E. Bone marrow chimeras and c-fms conditional ablation (Mafia) mice reveal an essential role for resident myeloid cells in lipopolysaccharide/TLR4-induced corneal inflammation. J Immunol. 2009;182(5):2738–2744. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond MS, Garcia-Aguilar J, Bickford JK, Corbi AL, Springer TA. The I domain is a major recognition site on the leukocyte integrin Mac-1 (CD11b/CD18) for four distinct adhesion ligands. J Cell Biol. 1993;120(4):1031–1043. doi: 10.1083/jcb.120.4.1031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elner VM, Elner SG, Pavilack MA, Todd RF, 3rd, Yue BY, Huber AR. Intercellular adhesion molecule-1 in human corneal endothelium. Modulation and function. Am J Pathol. 1991;138(3):525–536. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons CH, Illigens BM, Wang N, Freeman R. Quantification of sweat gland innervation: a clinical-pathologic correlation. Neurology. 2009;72(17):1479–1486. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181a2e8b8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamrah P, Liu Y, Zhang Q, Dana MR. Alterations in corneal stromal dendritic cell phenotype and distribution in inflammation. Arch Ophthalmol. 2003;121(8):1132–1140. doi: 10.1001/archopht.121.8.1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobden JA, Masinick SA, Barrett RP, Hazlett LD. Aged mice fail to upregulate ICAM-1 after Pseudomonas aeruginosa corneal infection. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1995;36(6):1107–1114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard C, Reed M. Unbiased Stereology-Three-Dimensional Measurements in Microscopy. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Huang C, Springer TA. A binding interface on the I domain of lymphocyte function-associated antigen-1 (LFA-1) required for specific interaction with intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1) J Biol Chem. 1995;270(32):19008–19016. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.32.19008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishihara A, Hou Y, Jacobson K. The Thy-1 antigen exhibits rapid lateral diffusion in the plasma membrane of rodent lymphoid cells and fibroblasts. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1987;84(5):1290–1293. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.5.1290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaeschke H, Smith CW. Cell adhesion and migration. III. Leukocyte adhesion and transmigration in the liver vasculature. Am J Physiol. 1997;273(6 Pt 1):G1169–G1173. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1997.273.6.G1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jester JV. Corneal crystallins and the development of cellular transparency. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2008;19(2):82–93. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2007.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jester JV, Petroll WM, Barry PA, Cavanagh HD. Expression of alpha-smooth muscle (alpha-SM) actin during corneal stromal wound healing. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1995;36(5):809–819. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knust J, Ochs M, Gundersen HJ, Nyengaard JR. Stereological estimates of alveolar number and size and capillary length and surface area in mice lungs. Anat Rec (Hoboken) 2009;292(1):113–122. doi: 10.1002/ar.20747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumagai N, Fukuda K, Fujitsu Y, Nishida T. Expression of functional ICAM-1 on cultured human keratocytes induced by tumor necrosis factor-alpha. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 2003;47(2):134–141. doi: 10.1016/s0021-5155(02)00686-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ley K. Molecular mechanisms of leukocyte recruitment in the inflammatory process. Cardiovasc Res. 1996;32(4):733–742. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ley K. Pathways and bottlenecks in the web of inflammatory adhesion molecules and chemoattractants. Immunol Res. 2001;24(1):87–95. doi: 10.1385/IR:24:1:87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z, Burns AR, Rumbaut RE, Smith CW. gamma delta T cells are necessary for platelet and neutrophil accumulation in limbal vessels and efficient epithelial repair after corneal abrasion. Am J Pathol. 2007;171(3):838–845. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.070008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z, Burns AR, Smith CW. Lymphocyte function-associated antigen-1-dependent inhibition of corneal wound healing. Am J Pathol. 2006a;169(5):1590–1600. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.060415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z, Burns AR, Smith CW. Two waves of neutrophil emigration in response to corneal epithelial abrasion: distinct adhesion molecule requirements. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006b;47(5):1947–1955. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z, Rumbaut RE, Burns AR, Smith CW. Platelet response to corneal abrasion is necessary for acute inflammation and efficient re-epithelialization. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006c;47(11):4794–4802. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-0381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang H, Brignole-Baudouin F, Labbe A, Pauly A, Warnet JM, Baudouin C. LPS-stimulated inflammation and apoptosis in corneal injury models. Mol Vis. 2007;13:1169–1180. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynam E, Sklar LA, Taylor AD, Neelamegham S, Edwards BS, Smith CW, Simon SI. Beta2-integrins mediate stable adhesion in collisional interactions between neutrophils and ICAM-1-expressing cells. J Leukoc Biol. 1998;64(5):622–630. doi: 10.1002/jlb.64.5.622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahon GJ, Anderson HR, Gardiner TA, McFarlane S, Archer DB, Stitt AW. Chloroquine causes lysosomal dysfunction in neural retina and RPE: implications for retinopathy. Curr Eye Res. 2004;28(4):277–284. doi: 10.1076/ceyr.28.4.277.27835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michel RP, Cruz-Orive LM. Application of the Cavalieri principle and vertical sections method to lung: estimation of volume and pleural surface area. J Microsc. 1988;150(Pt 2):117–136. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2818.1988.tb04603.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreland JG, Fuhrman RM, Pruessner JA, Schwartz DA. CD11b and intercellular adhesion molecule-1 are involved in pulmonary neutrophil recruitment in lipopolysaccharide-induced airway disease. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2002;27(4):474–480. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.4694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris AP, Tawil A, Berkova Z, Wible L, Smith CW, Cunningham SA. Junctional Adhesion Molecules (JAMs) are differentially expressed in fibroblasts and co-localize with ZO-1 to adherens-like junctions. Cell Commun Adhes. 2006;13(4):233–247. doi: 10.1080/15419060600877978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Brien TP, Li Q, Ashraf MF, Matteson DM, Stark WJ, Chan CC. Inflammatory response in the early stages of wound healing after excimer laser keratectomy. Arch Ophthalmol. 1998;116(11):1470–1474. doi: 10.1001/archopht.116.11.1470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oberyszyn TM, Conti CJ, Ross MS, Oberyszyn AS, Tober KL, Rackoff AI, Robertson FM. Beta2 integrin/ICAM-1 adhesion molecule interactions in cutaneous inflammation and tumor promotion. Carcinogenesis. 1998;19(3):445–455. doi: 10.1093/carcin/19.3.445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavilack MA, Elner VM, Elner SG, Todd RF, 3rd, Huber AR. Differential expression of human corneal and perilimbal ICAM-1 by inflammatory cytokines. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1992;33(3):564–573. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearlman E, Johnson A, Adhikary G, Sun Y, Chinnery HR, Fox T, Kester M, McMenamin PG. Toll-like receptors at the ocular surface. Ocul Surf. 2008;6(3):108–116. doi: 10.1016/s1542-0124(12)70279-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pei Y, Sherry DM, McDermott AM. Thy-1 distinguishes human corneal fibroblasts and myofibroblasts from keratocytes. Exp Eye Res. 2004;79(5):705–712. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2004.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pei Y, Reins RY, McDermott AM. Aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) 3A1 expression by the human keratocyte and its repair phenotype. Exp Eye Res. 2006;83(5):1063–1073. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2006.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrescu MS, Larry CL, Bowden RA, Williams GW, Gagen D, Li Z, Smith CW, Burns AR. Neutrophil interactions with keratocytes during corneal epithelial wound healing: a role for CD18 integrins. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48(11):5023–5029. doi: 10.1167/iovs.07-0562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillipson M, Heit B, Colarusso P, Liu L, Ballantyne CM, Kubes P. Intraluminal crawling of neutrophils to emigration sites: a molecularly distinct process from adhesion in the recruitment cascade. J Exp Med. 2006;203(12):2569–2575. doi: 10.1084/jem.20060925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roebuck KA, Finnegan A. Regulation of intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (CD54) gene expression. J Leukoc Biol. 1999;66(6):876–888. doi: 10.1002/jlb.66.6.876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarantos MR, Zhang H, Schaff UY, Dixit N, Hayenga HN, Lowell CA, Simon SI. Transmigration of neutrophils across inflamed endothelium is signaled through LFA-1 and Src family kinase. J Immunol. 2008;181(12):8660–8669. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.12.8660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz C, Hof PR. Design-based stereology in neuroscience. Neuroscience. 2005;130(4):813–831. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.08.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seo SK, Gebhardt BM, Lim HY, Kang SW, Higaki S, Varnell ED, Hill JM, Kaufman HE, Kwon BS. Murine keratocytes function as antigen-presenting cells. Eur J Immunol. 2001;31(11):3318–3328. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200111)31:11<3318::aid-immu3318>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith CW, Marlin SD, Rothlein R, Toman C, Anderson DC. Cooperative interactions of LFA-1 and Mac-1 with intercellular adhesion molecule-1 in facilitating adherence and transendothelial migration of human neutrophils in vitro. J Clin Invest. 1989;83(6):2008–2017. doi: 10.1172/JCI114111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Springer TA. Adhesion receptors of the immune system. Nature. 1990;346(6283):425–434. doi: 10.1038/346425a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stagos D, Chen Y, Cantore M, Jester JV, Vasiliou V. Corneal aldehyde dehydrogenases: multiple functions and novel nuclear localization. Brain Res Bull. 81(2–3):211–218. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2009.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q, Doerschuk CM. The signaling pathways induced by neutrophil-endothelial cell adhesion. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2002;4(1):39–47. doi: 10.1089/152308602753625843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weibel ER. Stereological methods in cell biology: where are we--where are we going? J Histochem Cytochem. 1981;29(9):1043–1052. doi: 10.1177/29.9.7026667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson SE, He YG, Weng J, Li Q, McDowall AW, Vital M, Chwang EL. Epithelial injury induces keratocyte apoptosis: hypothesized role for the interleukin-1 system in the modulation of corneal tissue organization and wound healing. Exp Eye Res. 1996;62(4):325–327. doi: 10.1006/exer.1996.0038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson SE, Mohan RR, Mohan RR, Ambrosio R, Jr, Hong J, Lee J. The corneal wound healing response: cytokine-mediated interaction of the epithelium, stroma, and inflammatory cells. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2001;20(5):625–637. doi: 10.1016/s1350-9462(01)00008-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yannariello-brown J, Hallberg CK, Haberle H, Brysk MM, Jiang Z, Patel JA, Ernst PB, Trocme SD. Cytokine modulation of human corneal epithelial cell ICAM-1 (CD54) expression. Exp Eye Res. 1998;67(4):383–393. doi: 10.1006/exer.1998.0514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida S, Shimmura S, Shimazaki J, Shinozaki N, Tsubota K. Serum-free spheroid culture of mouse corneal keratocytes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46(5):1653–1658. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-1405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao J, Nagasaki T. Mechanical damage to corneal stromal cells by epithelial scraping. Cornea. 2004;23(5):497–502. doi: 10.1097/01.ico.0000114129.63670.ab. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zieske JD, Guimaraes SR, Hutcheon AE. Kinetics of keratocyte proliferation in response to epithelial debridement. Exp Eye Res. 2001;72(1):33–39. doi: 10.1006/exer.2000.0926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]