Abstract

The transcription factor nuclear factor κB (NFκB) is a key factor in the immune response triggered by a wide variety of molecules such as inflammatory cytokines, or some bacterial and viral products. This transcription factor represents a new target for the development of anti-inflammatory molecules, but this type of research is currently hampered by the lack of a convenient and rapid screening assay for NFκB activation. Indeed, NFκB DNA-binding capacity is traditionally estimated by radioactive gel shift assay. Here we propose a new DNA-binding assay based on the use of multi-well plates coated with a cold oligonucleotide containing the consensus binding site for NFκB. The presence of the DNA-bound transcription factor is then detected by anti-NFκB antibodies and revealed by colorimetry. This assay is easy to use, non-radioactive, highly reproducible, specific for NFκB, more sensitive than regular radioactive gel shift and very convenient for high throughput screening.

INTRODUCTION

Nuclear factor κB (NFκB) is a ubiquitous transcription factor activated during the immune response to some viral and bacterial products, by oxidative stresses or pro-inflammatory cytokines (reviewed in 1). Interleukin 1 (IL-1) and tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα) are probably the strongest and most studied activators of NFκB. The activation mechanism of NFκB by these two pro-inflammatory cytokines is now well known. Briefly, NFκB is usually composed of the two subunits p65 (also called RelA) and p50, although these polypeptides belong to a family of proteins that can form homo- or heterodimers with each other (reviewed in 2). NFκB is sequestered in the cytoplasm of most resting cells through its association with an inhibitory protein called IκB. During stimulation by IL-1 or TNFα, a whole cascade of adaptor proteins and protein kinases is activated, leading to the phosphorylation of IκB by the IκB kinases α and β (IKKα/β) (reviewed in 3). Once phosphorylated, IκB is targetted to the proteasome and degraded. Consequently, NFκB is freed from its cytoplasmic anchor, migrates into the nucleus, and binds to its consensus decameric sequence located in the promoter region of several genes involved in the pro-inflammatory response, encoding various immunoreceptors, cell adhesion molecules, cytokines and chemokines (reviewed in 1).

In order to monitor NFκB activation, there are three major methods used currently. First, cytoplasmic IκB degradation can be estimated by western blot, using antibodies raised against IκB (4). This method is time consuming, and does not allow the handling of a large number of samples. Second, the DNA-binding capacity of active NFκB can be assayed by gel retardation, also called electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) (5). In this case, cell extracts are incubated with a radioactive double-stranded oligonucleotidic probe, containing the consensus sequence for NFκB binding. If NFκB is active in the cell extract, it binds to its consensus sequence. Samples are then resolved by native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis followed by autoradiography. A retarded band, corresponding to the NFκB/probe complexes appears, in addition to the fast migrating band corresponding to the free probe. In NFκB inactive form, IκB prevents its binding to DNA. In this case, the autoradiography shows only one band, corresponding to the free probe. This method is sensitive but difficult to adapt for automatization and is not suited for screening. In addition, it is based on the use of 32P radioactive probes. A third, largely-used, method to indirectly assay NFκB activation is based on reporter genes, typically luciferase or β-galactosidase genes, placed under the control of a promoter containing the NFκB consensus sequence. This promoter is either artificial, made of several NFκB cis-elements and a TATA box, or a natural one, like the HIV long terminal repeat element. In this case, transcription factors other than NFκB can influence the expression level of the reporter gene. In addition, as the read-out is the enzymatic activity of luciferase, for instance, the results may be affected by interferences with downstream processes like the general transcription or transduction machinery. Nevertheless, this method is widely used as it is sensitive and easy to perform on a large number of samples, provided the cells are efficiently transfected with a reporter vector. Finally, a fourth method has been proposed, based on the specific recognition by antibodies of the nuclear localization sequence (NLS) of NFκB (6), a domain of the protein which is masked by IκB when the transcription factor is in its inactive form. The activation of NFκB can thus be visualized by immunofluorescence thanks to this antibody. Once again, this method is not suited to the screening of multiple samples.

Altogether, these various methods have been very helpful for fundamental research during the last 10 years, and in particular for the identification of the molecular mechanisms involved in NFκB activation. Nevertheless, although NFκB is a key factor in various immune processes and represents a first choice pharmacological target for anti-inflammatory therapy (7), research in this field has been hampered by the fact that no convenient assay suitable for large-scale screening procedures was available up to now.

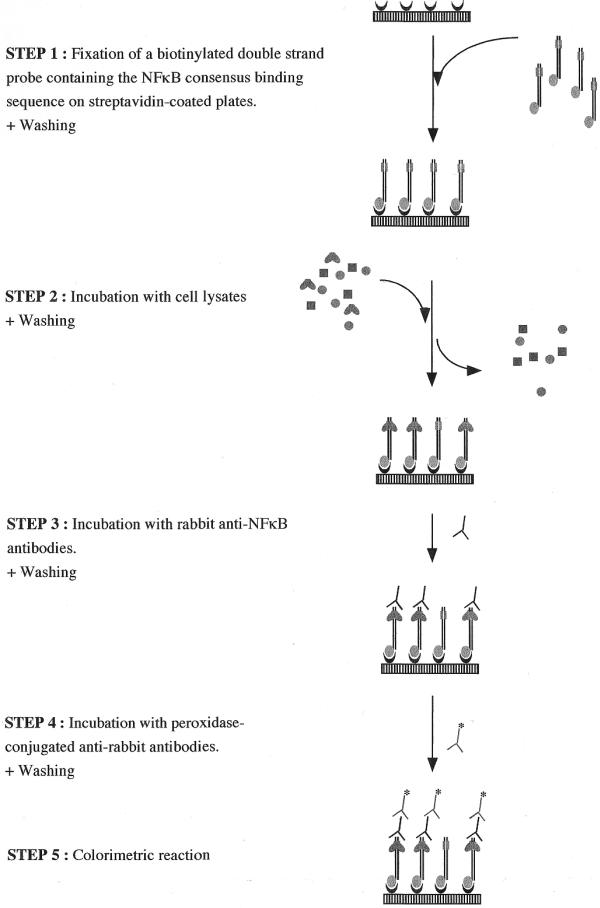

In this context we developed a new sensitive assay to estimate the amount of activated NFκB in cell extracts. The test is based on an ELISA principle, except that the protein of interest, NFκB, is captured not by an antibody, as in classical ELISA, but by a double-stranded oligonucleotidic probe containing the consensus binding sequence for NFκB (Fig. 1). Consequently, only the activated transcription factor is captured by the probe bound in microwell plates. The binding of NFκB to its consensus sequence is then detected using a primary anti-NFκB antibody, followed by a secondary antibody conjugated to horseradish peroxidase. Finally, the results are quantified by a chromogenic reaction. This non-radioactive multiwell-based assay was first optimized with purified NFκB (the p50/p50 homodimer) and then with whole-cell extracts. By comparing this new method with gel retardation, we clearly show that our optimized assay is specific, more rapid and sensitive than gel retardation and is better suited for large-scale screening.

Figure 1.

Schematic procedure of the microwell NFκB-DNA binding assay.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture and preparation of cell extracts

The cell line WI-38 VA13, an SV40 virus-transformed human fibroblastic cell line, was purchased from the American Type Culture Collection and plated in 75 cm2 flasks. Cells were serially cultivated in minimum essential medium (Gibco, UK) supplemented with Na2SeO3 10–7 M and antibiotics, in the presence of 10% fetal bovine serum. To activate NFκB, cells were stimulated for 30 min with 5 ng/ml IL-1β (R&D systems, UK). After stimulation, cells were rinsed twice with cold PBS before being scraped and centrifuged for 10 min at 1000 r.p.m. The pellet was then resuspended in 100 µl of lysis buffer (20 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 0.35 M NaCl, 20% glycerol, 1% NP-40, 1 mM MgCl2·6H2O, 0.5 mM EDTA, 0.1 mM EGTA) containing a protease inhibitor cocktail (#1697498; Roche, Germany). After 10 min on ice, the lysate was centrifuged for 20 min at 14 000 r.p.m. The supernatant constitutes the total protein extract and can be kept frozen at –70°C.

EMSA

The binding reaction occurs in a binding mixture of 20 µl containing 2 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 5% glycerol, 75 mM KCl, 2.5 mM dithiotreitol (DTT), 2 µg poly d(IC), 20 µg bovine serum albumin (BSA), cell extract (25 µg protein determined according to the Bradford assay) and a 32P-labeled oligonucleotide (±1 ng or 20 000 c.p.m.). The cold double-strand probe (5′-AGTTGAGGGGACTTTCCCAGGC) was purchased from Promega (Madison, WI), labeled with γ-32P using the T4 polynucleotide kinase and purified on a Sephadex S-200 column. After 30 min of incubation, the binding mixture was analyzed on a native 4% acrylamide gel in 0.5× TBE (0.9 M Tris, 0.9 M boric acid, 0.02 M EDTA), followed by autoradiography. Competition experiments were realized with a 1-, 5- or 20-fold excess of the 22 bp non-radioactive probe, either wild-type (see above) or mutated: 5′-AGTTGAGCTCACTTTCCCAGGC (with the mutated three bases, compared to the wild-type sequence, underlined). Radioactive and non-radioactive probes were first mixed before adding the cell lysate for the binding reaction. Samples were then processed as described above.

Microwell colorimetric NFκB assay

Figure 1 depicts this assay schematically. The following parameters are the final conditions used for the microwell colorimetric assay after optimization. The optimization steps are summarized in the text.

Step 1: Binding of the double-stranded oligonucleotidic probe on multi-well plates. The NFκB consensus oligonucleotide 5′-AGTTGAGGGGACTTTCCCAGGC-3′ (Promega, Madison, WI) was added at the 3′ end of a 100 bp random sequence chosen for the absence of the NFκB consensus binding sequence. The resulting 122 bp probe was produced by PCR using a biotinylated forward primer (TGGCCAAGCGGCCTCTGATAAC) and for the reverse primer, the NFκB consensus sequence. The PCR product was purified on ultracentrifugation membranes.

As the 5′ extremity is biotinylated, this probe can be linked to streptavidin-coated 96-well plates (Roche): 2 pmol of probe per well was incubated for 1 h at 37°C in 50 µl phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Plates were then washed twice with PBS + 0.1% Tween-20 to remove the probe in excess and once with PBS alone. The amount of DNA fixed on streptavidin-coated plates was quantified using the Picogreen assay (Molecular Probes, OR) following the recommendations of the manufacturer.

Step 2: Binding of NFκB to the double-stranded probe. This assay was first set up with purified p50 (Promega), and then with whole-cell lysates from cells stimulated with IL-1β or left unstimulated (see ‘preparation of cell extracts’, above). Twenty microliters of p50 diluted in lysis buffer or 20 µl of cell extract were incubated with 30 µl of binding buffer [4 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 100 mM KCl, 8% glycerol, 5 mM DTT, 0.2% BSA, 0.016% poly d(IC)] in microwells coated with the probes containing the NFκB binding consensus. After a 1 h incubation at room temperature with a mild agitation (200 r.p.m. on an IKA MS2 vortex), microwells were washed three times with PBS + 0.1% Tween-20.

Step 3: Binding of anti-NFκB antibodies to the NFκB–DNA complex. Rabbit anti-NFκB antibodies (100 µl), diluted 1000 times in a 10 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) containing 50 mM NaCl and 1% non-fat dried milk, were incubated in each well for 1 h at room temperature. Two different antibodies were tested (see Results): a rabbit anti-NFκB p50 (#100-4164; Rockland, Gilbertsville, PA) and a rabbit anti-NFκB p65 (#sc-372; Santa Cruz, CA). Microwells were then washed three times with 200 µl PBS + 0.1% Tween-20. Irrelevant antibodies were also tested without generating any signal: a rabbit anti-cPLA2 and anti-IκBα (Santa Cruz, CA).

Step 4: Binding of peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG to the anti-NFκB antibodies. Peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (100 µl; #611-1302; Rockland), diluted 1000 times in a 10 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) containing 50 mM NaCl and 1% non-fat dried milk, were incubated in each well for 1 h at room temperature. Microwells were then washed four times with 200 µl PBS + 0.1% Tween-20.

Step 5: Colorimetric detection. Tetramethylbenzidine (100 µl; Biosource, Belgium) was incubated for 10 min at room temperature before adding 100 µl of stopping solution (Biosource). Optical density was then read at 450 nm, using a 655 nm reference wavelength, with an Ultramark microplate reader (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). For samples presenting a very high optical density at 450 nm, the plate can be read at 405 nm to avoid a saturation of the plate reader. The results are expressed after subtraction of the blank values. The blanks are realized following the same procedure as the tests, except that lysis buffer is incubated in the microwells instead of purified p50 or cell lysate.

RESULTS

Optimization of the NFκB DNA-binding assay on purified p50 homodimer

The successive steps of the colorimetric assay for NFκB-DNA binding (Fig. 1) were optimized with purified p50/p50 homodimer. The first step, the fixation of the double-stranded DNA probe containing the NFκB consensus sequence, was performed through a biotin–streptavidin interaction: increasing concentrations of the 5′-biotinylated oligonucleotide were incubated in streptavidin-coated microwells. The DNA-binding assay was then performed as described in Materials and Methods, with sequential incubation with purified p50, anti-p50 antibodies and finally anti-rabbit antibodies conjugated with peroxidase. We determined that maximum fixation of p50 is obtained in microwells coated with 1 pmol of DNA.

Different parameters were then tested to optimize the binding of the purified p50 homodimer on the DNA probe (Fig. 1, step 2): the incubation time, the temperature and the agitation. The binding reaction was accelerated when performed with mild agitation. The signal obtained increases with the incubation time, reaching a plateau after 1 h. The plateau level was higher at room temperature than at 37°C, suggesting that the p50 homodimer could be partly degraded or denatured at 37°C. The choice of these parameters (agitation, 1 h, room temperature) led to a 30% improvement in the detected signal.

The binding of the rabbit anti-p50 antibody on the p50 homodimer–DNA complex (Fig. 1, step 3) was then optimized in terms of temperature (37°C or room temperature), incubation time (from 30 to 120 min), antibody concentration (up to 80 µg/ml) and incubation buffer. An incubation at 37°C is not recommended as the signal obtained is lower than at room temperature, again suggesting a partial denaturation of p50 at 37°C. The maximum signal was obtained after a 1 h incubation and remarkably increased with the antibody concentration: we chose a final concentration of 80 µg/ml, corresponding to a 1/1000 dilution of the provided stock antibody. The NaCl concentration in the phosphate buffer during the incubation with the anti-p50 antibody also influenced the signal obtained: with 50 mM NaCl, the signal was 15% higher than with 150 mM, whereas it is barely detectable with 300 mM NaCl. The selected parameters for the incubation with the anti-p50 antibody were 1 h at room temperature with a 1/1000 dilution of the antibody in phosphate buffer with 50 mM NaCl.

The same parameters were tested for step 4 (Fig. 1), i.e. the incubation with the anti-rabbit IgG antibody conjugated with horseradish peroxidase. The changes in the signal were very similar to those in step 3, except that the effect of the antibody concentration was much less pronounced. We chose the same conditions as for step 3. Altogether, with the optimization of the steps 2–4, the signal corresponding to the binding of p50 to the DNA probe increased 8-fold.

Optimization of the NFκB DNA-binding assay in whole-cell extracts

We then applied the method in order to detect NFκB activation in whole-cell protein extracts, coming either from unstimulated cells or from cells stimulated with IL-1 (Fig. 3). The signal obtained with IL-1-stimulated extracts was twice as high as the signal from unstimulated cells, indicating that the microwell NFκB DNA-binding assay allows the detection of intracellularly-activated NFκB, although at this stage, the sensitivity of the assay remains low (100 µg of cell protein extract from stimulated cells is necessary to detect NFκB activation).

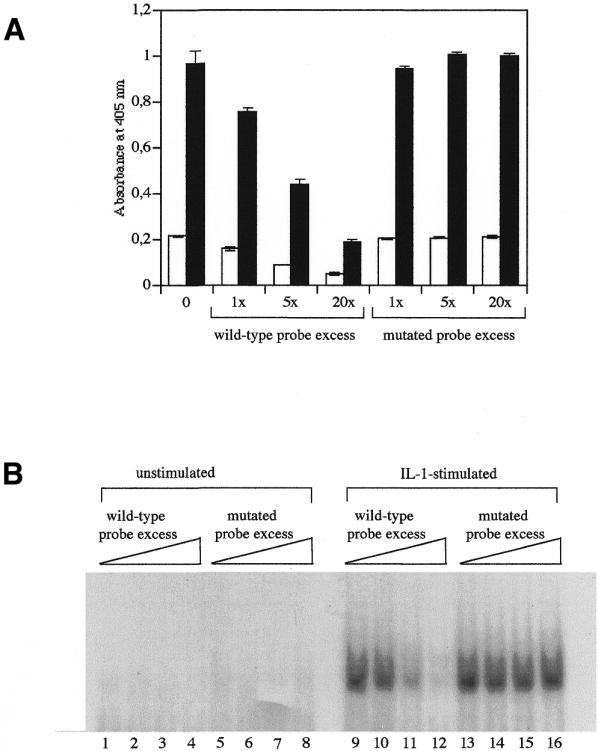

Figure 3.

Competition assay, using a wild-type probe and a mutated probe, on the DNA-binding of NFκB, estimated by the microwell assay (A) and by EMSA (B). (A) Microwells bearing the 122 bp DNA probe were incubated with an increasing excess of the 22 bp non-biotinylated probe, containing either the wild-type or the mutated NFκB-binding consensus sequence. The DNA-binding assay was then performed with 5 µg protein of cell lysates prepared either from unstimulated cells (open columns) or from IL-1-stimulated cells (black columns). The data represent the means of three values ± SD. (B) The radioactive 22 bp probe was first mixed with an increasing excess (0, 1, 5 and 20 times) of the cold 22 bp probe containing either the wild-type (lanes 1–4 and 9–12) or the mutated (lanes 4–8 and 13–16) NFκB-binding consensus sequence. EMSA was then performed with 25 µg protein of cell extracts coming from unstimulated (lanes 1–8) or IL-1-stimulated cells (lanes 9–16).

To make the assay more sensitive with whole-cell lysates, several parameters were modified. Regarding the binding of intracellularly activated NFκB to the DNA probe (step 2), an increase in the BSA concentration (from 0.12 to 0.6%) reduced the signal observed in non-stimulated cell lysates, thereby increasing the specificity of the assay. In contrast to BSA, the concentration of DTT (2–5 mM) and poly d(IC) (0.012–0.0012%) did not affect the signal. Of note is that poly d(IC) can be replaced indifferently by salmon sperm DNA. At steps 3 and 4 of the procedure, the addition of 1% BSA or non-fat dried milk during the incubations with the primary and secondary antibodies decreased the blanks. Addition of BSA, ovalbumin or non-fat dried milk in the washing solution did not improve the signal-to-noise ratio.

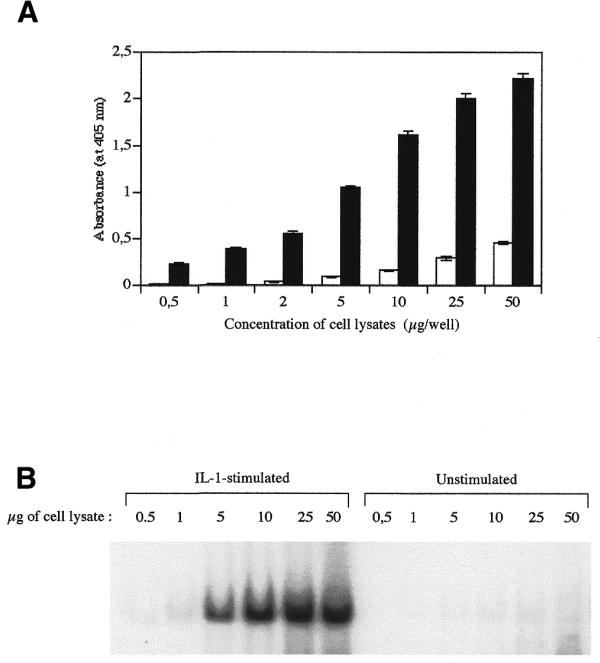

A great improvement in the sensitivity was obtained by using another anti-NFκB antibody. Indeed, NFκB is composed of two subunits belonging to the Rel-NFκB family (reviewed in 2). The p50/p65 (p65 is also called RelA) heterodimer is probably the most widespread, and is the only dimer activated in IL-1-stimulated WI-38 VA13 cells, as shown previously by supershift assay (10). We therefore used an anti-p65 polyclonal antibody in the third step of this assay, instead of the anti-p50 used previously. There was a 15-fold enhancement of signal difference between unstimulated and IL-1-stimulated cell extracts, as compared to the anti-p50 antibody (data not shown). Under these conditions, the assay was performed in parallel with EMSA on the same protein extracts. The results presented in Figure 2 clearly show that the NFκB DNA-binding assay in microwells is at least 10 times more sensitive than the EMSA: 5 µg of proteins was required to detect a signal by EMSA, but <0.5 µg of protein was necessary for the microwell assay. Figure 2 also indicates that the microwell assay is dose-dependent and linear at least in the range of 2–10 µg of protein. For higher protein concentrations, the values tend to saturate in a plateau manner, a phenomenon also observed in EMSA.

Figure 2.

Comparison of the NFκB DNA-binding assay in microwells (A) and by EMSA (B). (A) Microwells containing the DNA probe were incubated with increasing amounts of cell lysates (0.5, 1, 2, 5, 10, 25 and 50 µg of proteins) prepared either from unstimulated cells (open columns) or from IL-1-stimulated cells (black columns). The data represent the means of three values ± SD. (B) EMSA was performed with 0.5, 1, 5, 10, 25 and 50 µg of proteins extracted from unstimulated cells or from IL-1-stimulated cells [same protein extracts as in (A)]. The gel was exposed for 5 days.

Finally, working on whole-cell extracts, we wanted to check the specificity of the assay in a competition experiment. In microwells coated with 1 pmol of the 122 bp probe containing the NFκB-consensus binding sequence, we added 1, 5 or 20 pmol of a 22 bp probe containing either the wild-type NFκB-consensus binding sequence or the same sequence with three mutated bases as proposed by Ivanov et al. (9). They showed that mutating the κB motif from 5′-GGGGACTTCC into 5′-GCTCACTTTCC (mutation indicated with bases in bold) resulted in the complete loss of NFκB DNA-binding. As shown in Figure 3, the wild-type probe competed in a dose-dependent manner, while the mutated probe did not. This competition shows the specificity of the NF-κB binding on the DNA-coated microwells. In addition, unrelated antibodies were tested in step 3, instead of anti-p50 antibodies; the antibodies used were raised either against the cytosolic phospholipase A2 (cPLA2) or against IκBα, and no signal was detected (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

In this paper, we showed that NFκB DNA-binding activity can be easily and quickly detected in a microwell-based colorimetric assay. The most critical factor in the optimization process was the choice and the concentration of the polyclonal anti-NFκB antibody. With both anti-p50 and anti-p65 antibodies, the higher the concentration of the antibody, the stronger the signal was. But the most impressive improvement of this assay, a 15-fold signal increase, was achieved when shifting from an anti-p50 polyclonal antibody (Rockland) to an anti-p65 antibody (Santa Cruz). We wondered whether this increase resulted from a better affinity of the antibody or from a better accessibility of p65 in the DNA-transcription factor complex to its antibody, as compared to p50. Both hypotheses are probably right, since the use of an anti-p50 polyclonal antibody from Santa Cruz gave a much better signal than the anti-p50 antibody from Rockland (about 11 times greater), but the signal was still 25% lower than with the anti-p65 antibody (data not shown). Antibodies from other companies could possibly be tested in the future to further improve the sensitivity of the assay, although the assay is now suitable for cells cultured in 24-well plates, and thus compatible with high-throughput screening.

Preliminary results indicate that the methodology developed for this assay can be applied to other transcription factors like CREB and AP-1 (data not shown), provided antibodies specific for the transcription factor are available. This approach has already been used for measuring the DNA-binding capacity of a GST-purified recombinant human helicase-like transcription factor (11), but the authors did not check the feasibility of assaying helicase from cell extracts. Gubler and Abarzua (12) have developed another non-radioactive ELISA-type assay to measure the DNA binding of another transcription factor, p53. In their assay, the transcription factor was first incubated with the biotinylated double-stranded DNA probe and anti-p53 antibody. The mixture was then transferred in microwells coated with anti-IgG, and the binding of the DNA/p53/antibody complex is revealed by a chromogenic reaction, with the streptavidin-conjugated alkaline phosphatase. This method has two main disadvantages: first, the binding reaction is performed in a separate container before being transferred to the multiwell plate. Secondly, the antibody binds to active as well as inactive transcription factor. As the inactive factors do not bind to the DNA probe, the antibodies can be rapidly saturated by the inactive factor, thereby decreasing the sensitivity of the assay.

Preliminary results indicate that the procedure described here can be adapted to microarrays to detect NFκB activation (data not shown). In the future, we could even use the method developed by Bulyk et al. (13) to synthesize double-stranded DNA directly on microarrays.

This assay could be used in the research and screening of new anti-inflammatory drugs, but also to gain a better understanding of the molecular mechanisms of action of well-known drugs, such as aspirin. The recent discovery that both aspirin and salicylate inhibit the activity of the IκB kinase (14) has confirmed NFκB as a possible key target for the development of anti-inflammatory drugs (7). Clearly, the NFκB DNA-binding assay presented in this paper offers attractive advantages for both fundamental and pharmaceutical researchers: it is simple, highly reproducible and sensitive, rapid, non-radioactive and suited to large-scale screening.

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was supported by the Region Wallonne. We thank the FNRS (Fonds National de la Recherche Scientifique, Belgium) for financial support. P.R. is a postdoctoral researcher at the FNRS. This text presents results of the Belgian Programme on Interuniversity Poles of Attraction initiated by the Belgian State, Prime Minister’s Office, Science Policy Programming.

References

- 1.Baeuerle P.A. and Baichwal,V.R. (1997) NF-κB as a frequent target for immunosuppressive and anti-inflammatory molecules. Adv. Immunol., 65, 111–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ghosh S., May,M.J. and Kopp,E.B. (1998) NF-κB and Rel proteins: evolutionarily conserved mediators of immune responses. Annu. Rev. Immunol., 16, 225–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Karin M. (1999) The beginning of the end: IκB kinase (IKK) and NF-κB activation. J. Biol. Chem., 274, 27339–27342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sun S.C., Ganchi,P.A., Beraud,C., Ballard,D.W. and Greene,W.C. (1994) Autoregulation of the NF-κb transactivator RelA (P65) by multiple cytoplasmic inhibitors containing ankyrin motifs. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 91, 1346–1350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schreck R., Zorbas,H., Winnacker,E.L. and Baeuerle,P.A. (1990) The NF-κB transcription factor induces DNA bending which is modulated by its 65 kDa subunit. Nucleic Acids Res., 18, 6497–6502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zabel U., Henkel,T., Silva,M. and Baeuerle,P. (1993) Nuclear uptake control of NF-κB by MAD-3, an IκB protein present in the nucleus. EMBO J., 12, 201–211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee J.I. and Burckart,G.J. (1998) Nuclear factor κB: important transcription factor and therapeutic target. J. Clin. Pharmacol., 38, 981–993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rasmussen S.R., Larsen,M.R. and Rasmussen,S.E. (1991) Covalent immobilization of DNA onto polystyrene microwells: the molecules are only bound at the 5′ end. Anal. Biochem., 198, 138–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ivanov V., Merkenschlager,M. and Ceredig,R. (1993) Antioxidant treatment of thymic organ cultures decreases NF-κB and TCF1(α) transcription factor activities and inhibits αβ-T-cell development. J. Immunol ., 151, 4694–4704. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Renard P., Zachary,M.-D., Bougelet,C., Mirault,M.-E., Haegeman,G., Remacle,J. and Raes,M. (1997) Effects of antioxidant enzyme modulations on interleukin-1-induced nuclear factor κB activation. Biochem. Pharmacol., 53, 149–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Benotmane A.M., Hoylaerts,M.F., Collen,D. and Belayew,A. (1997) Nonisotopic quantitative analysis of protein–DNA interactions at equilibrium. Anal. Biochem., 250, 181–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gubler M.L. and Abarzua,P. (1995) Nonradioactive assay for sequence-specific DNA binding proteins. Biotechniques, 18, 1008, 1011–1014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bulyk M.L., Gentalen,E., Lockhart,D.J. and Church,G.M. (1999) Quantifying DNA–protein interactions by double-stranded DNA arrays. Nat. Biotechnol., 17, 573–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yin M.J., Yamamoto,Y. and Gaynor,R.B. (1998) The anti-inflammatory agents aspirin and salicylate inhibit the activity of I(κ)B kinase-beta. Nature, 396, 77–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]