Abstract

BACKGROUND AND PURPOSE

The high predisposition to Torsade de Pointes (TdP) in dogs with chronic AV-block (CAVB) is well documented. The anti-arrhythmic efficacy and mode of action of Ca2+ channel antagonists, flunarizine and verapamil against TdP were investigated.

EXPERIMENTAL APPROACH

Mongrel dogs with CAVB were selected based on the inducibility of TdP with dofetilide. The effects of flunarizine and verapamil were assessed after TdP and in different experiments to prevent dofetilide-induced TdP. Electrocardiogram and ventricular monophasic action potentials were recorded. Electrophysiological parameters and short-term variability of repolarization (STV) were determined. In vitro, flunarizine and verapamil were added to determine their effect on (i) dofetilide-induced early after depolarizations (EADs) in canine ventricular myocytes (VM); (ii) diastolic Ca2+ sparks in RyR2R4496+/+ mouse myocytes; and (iii) peak and late INa in SCN5A-HEK 293 cells.

KEY RESULTS

Dofetilide increased STV prior to TdP and in VM prior to EADs. Both flunarizine and verapamil completely suppressed TdP and reversed STV to baseline values. Complete prevention of TdP was achieved with both drugs, accompanied by the prevention of an increase in STV. Suppression of EADs was confirmed after flunarizine. Only flunarizine blocked late INa. Ca2+ sparks were reduced with verapamil.

CONCLUSIONS AND IMPLICATIONS

Robust anti-arrhythmic efficacy was seen with both Ca2+ channel antagonists. Their divergent electrophysiological actions may be related to different additional effects of the two drugs.

Keywords: ventricular repolarization, drug-induced TdP arrhythmias, safety pharmacology, flunarizine, verapamil, CAVB dog

Introduction

In numerous pro-arrhythmic circumstances, calcium [Ca2+] overload of the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) is the cause of Ca2+ leak through ryanodine receptors (RyR). The ensuing Ca2+ sparks increase cytosolic [Ca2+]i which in turn may activate the sodium-calcium exchanger (NCX) to generate delayed afterdepolarizations (DADs) and trigger ventricular arrhythmias (de Groot et al., 2000; Pogwizd et al., 2001). The ‘Ca2+ antagonists’, flunarizine and verapamil, suppress DADs or DAD-dependent ventricular tachycardias (VTs) either induced by ouabain (Rosen and Danilo, 1980; Jonkman et al., 1986; Vos et al., 1990; Park et al., 1992) or by cathecholamines (Park et al., 1992). In addition, both drugs have also been shown to be effective against Torsade de Pointes (TdP) arrhythmias, whether seen in congenital (Shimizu et al., 1995) or in acquired long QT syndromes (January et al., 1988; Cosio et al., 1991; Verduyn et al., 1995; Carlsson et al., 1996; Aiba et al., 2005; Gallacher et al., 2007). The latter, however, are more likely initiated by early after depolarizations (EADs). The mechanisms underlying these EADs can be reactivation of ICa,L, a persistent INa or the NCX-mediated inward current (January et al., 1988; Volders et al., 1997; Sipido et al., 2000; Antoons et al., 2007). Although both flunarizine and verapamil belong to the category of Ca2+ antagonists, they have additional actions (Zhang et al., 1999; Trepakova et al., 2006), such as blocking the delayed rectifier current (IKr) that may negatively affect their anti-arrhythmic efficacy against repolarization-dependent VTs.

The canine model of chronic AV-block (CAVB) has been used to initiate both DAD- and EAD-dependent VTs (Vos et al., 1990; Verduyn et al., 1995; Volders et al., 1997; de Groot et al., 2000; Sipido et al., 2000). The enhanced susceptibility to triggered arrhythmias in this model has been related to SR Ca2+ overload and to a diminished repolarization reserve (Vos et al., 1990; de Groot et al., 2000; Sipido et al., 2000; Oros et al., 2008). In this setting, quantification of beat-to-beat variability of repolarization duration (BVR) by short-term variability (STV) has been shown to be a better parameter to predict proarrhythmic predisposition than the QT-time (Thomsen et al., 2006; Oros et al., 2008).

The objectives of this study were to determine if: (i) flunarizine and verapamil prevented and/or suppressed dofetilide-induced TdP in dogs with CAVB; (ii) flunarizine and verapamil improved repolarization reserve, as quantified by STV; (iii) flunarizine was effective against dofetilide-induced increases in STV and EADs in ventricular myocytes isolated from dogs with CAVB; and (iv) their mode of action on Ca2+ sparks and late INain vitro differed.

Methods

General

All animal care and experimental handling was in accordance with the ‘European Directive for the Protection of Vertebrate Animals used for Experimental and Scientific Purpose, European Community Directive 86/609/CEE’ and under the regulations of The Committee for Experiments on Animals of Utrecht University, the Netherlands.

A total of 26 adult mongrel dogs (Marshall, USA; 23 ± 3 kg, 16 females) were included. Four weeks after induction of complete AV-block, 22 animals were given a dofetilide test (i.v. infusion of 0.025 mg·kg−1 for 5 min). In this group, five dogs were excluded because they had TdP at baseline (n= 3) or they were non-inducible (n= 2). Repeatability and reproducibility of arrhythmias have been well studied in this model (Oros et al., 2008). In a second group of four animals with CAVB, verapamil and lidocaine were administered in combination to explore their effect on electrophysiological parameters.

All experiments were performed under complete anesthesia, induced with barbiturates and maintained during the experiments with isoflurane (1.5 %). The detailed description of experimental procedures, AV-node ablation, electrocardiogram and monophasic action potential (MAP) recordings (with MAP duration, MAPD at 90 % repolarization), definitions and data analysis, including determination of STVLV from the left ventricle (LV) MAPD, have been already published (Thomsen et al., 2004; Oros et al., 2006). Early ectopic activity was defined as ectopic beats (EB) initiating before the end of the preceding T wave. Distinction between single (SEBs) and multiple ectopic beats (MEBs) was made as the latter are considered more proarrhythmic (Belardinelli et al., 2003).

Anti-arrhythmic protocols in vivo

Experimental protocols were performed, separated by at least 2 weeks intervals:

Suppression protocol

Approximately 10 min after the start of dofetilide when TdP was reproducibly seen, flunarizine (n= 10; 2 mg·kg−1 for 2 min, i.v.) or verapamil (n= 7; 0.4 mg·kg−1 for 3 min, i.v) were administered to suppress pro-arrhythmic activity.

Validation that TdP remained present in the subsequent 10 min period after dofetilide was recently provided (Oros et al., 2008). To allow comparison of verapamil and flunarizine, the dose of verapamil chosen, had a similar negative inotropic effect in dogs (Vos et al., 1992; Bril et al., 1996) as seen with the anti-arrhythmic dose of flunarizine. Moreover, these equipotent negative haemodynamic effects were confirmed in six sinus rhythm dogs using a 7F catheter (Sentron, Roden, the Netherlands): LV end-systolic pressure decreased by 20% with both drugs: flunarizine from 94 ± 9 to 75 ± 9 mmHg (P < 0.05) and verapamil from 87 ± 13 to 67 ± 9 mmHg (P < 0.05).

Prevention protocol

Whether vulnerability to dofetilide-induced TdP could be prevented by pretreatment with flunarizine (n= 8) or verapamil (n= 6) was investigated in this set of experiments. The dose of dofetilide used was the same as in the previous experiment. Three animals were tested serially with both verapamil and flunarizine.

Combination of drugs

To test if the electrophysiological effects seen with flunarizine were due to a combined block of ICa,L and Iate INa, verapamil (0.2 mg·kg−1 for 1.5 min) was followed 5 min later by lidocaine (1.5 mg·kg−1 for 1 min), a preferential late INa blocker (Fredj et al., 2006).

In vitro experiments

The following concentrations of drugs were used: 1 µM dofetilide, 1 µM and 10 µM flunarizine or verapamil.

Effects of flunarizine on cellular STV

Single myocytes from CAVB dogs were enzymically isolated (Volders et al., 1998). Action potentials were triggered in whole-cell current clamp mode with 2 ms current injections at a cycle length of 2000 ms and recorded with PClamp9 software (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). Action potential duration (APD) was measured at 90% repolarization and cellular STV was calculated from 20 successive APDs (STVAPD) similar to the in vivo quantification(Volders et al., 1998; Thomsen et al., 2004). Experiments were performed in Tyrode solution containing (in mmol·L−1): 137 NaCl, 5.4 KCl, 0.5 MgCl2, 1.8 CaCl2, 11.8 HEPES and 10 glucose, pH 7.4. Pipettes had a resistance of 2–3 MΩ when filled with pipette solution, containing (in mmol·L−1): 130 KCl, 10 NaCl, 10 HEPES, 5 MgATP and 0.5 MgCl2, pH 7.2. As with the in vivo experiments, two experimental protocols were used:

Protocol 1: effects of flunarizine on baseline cellular APD and STV in eight myocytes isolated from the LV of four dogs.

Protocol 2: effects of flunarizine on dofetilide-induced EADs. If 1 µM dofetilide induced EADs, flunarizine was added to the Tyrode solution to test its suppressive effect on EADs and dofetilide-increased APD and STV. For these experiments another eight cells [n= 4 right ventricle (RV) and n= 4 LV] from five dogs were used.

Effects of flunarizine and verapamil on INa

For recording cardiac peak and late INa, SCN5A-HEK 293 cells (expressing Nav1.5) were superfused with bath solution containing (in mmol·L−1): 140 NaCl, 4.0 KCl, 1.8 CaCl2, 0.75 MgCl2 and 5 HEPES (pH adjusted to 7.4 with NaOH). The pipette solution contained (in mmol·L−1): 20 CsCl, 120 CsF, 2 EGTA and 5 HEPES (pH adjusted to 7.4 with CsOH). All experiments were performed at 21 ± 1°C. Whole-cell membrane current was recorded as previously described (Hamill et al., 1981). Computer software (pCLAMP 10.0, Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA) was used to generate voltage-clamp protocols. Patch-clamp amplifier (Multiclamp 700B, Molecular Devices) data were sampled at 5 kHz. Whole-cell capacitance was compensated using the internal voltage-clamp circuitry and about 75–80% of series resistance was compensated. Membrane potentials were not corrected for junction potentials that arise between the pipette and bath solution. Cells were held at −140 mV and dialysed for 5 min before INa recording. Data analysis of all measured currents was performed using pCLAMP 10.0 and Origin 7.0 (MicroCal, Northampton, MA) software. To measure the extent of tonic block (first-pulse) by flunarizine or verapamil on peak INa, 24-ms depolarizing steps to −20 mV from a holding potential of −140 mV were applied to cells at a rate of 0.1 Hz. The magnitude of peak INa in the presence of drug was normalized to the respective control value. To measure the effect of flunarizine or verapamil on late INa, the normally small late INa was augmented by exposure of cells to Anemone Toxin-II (ATX-II; 3 nM; Song et al., 2008), and the effect of drug to reduce the ATX-II-induced late INa was determined. Late INa was defined as the magnitude of INa between 200 and 220 ms after application of a 220-ms depolarizing step to −20 mV from a holding potential of −140 mV applied at a rate of 0.1 Hz.

Effects of flunarizine and verapamil on Ca2+ sparks

Abnormally high spontaneous Ca2+ release in diastole (Ca2+ sparks) were recorded in intact quiescent myocytes enzymically isolated from homozygous mice carrying the mutation R4496C of the cardiac ryanodine receptor (RyR2R4496C+/+), which underlies catecholamine polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (CPVT) (Priori et al., 2001; Fernandez-Velasco et al., 2009). To measure the effects of verapamil and flunarizine on spontaneous Ca2+ spark activity, cells were loaded with fluorescent Ca2+ indicator (Fluo-3 AM) as previously described (Fernandez-Velasco et al., 2009). Cells were recorded under continuous perfusion with Tyrode solution (in mmol·L−1: 140 NaCl, 4 KCl, 1.1 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, 10 glucose, 1.8 CaCl2; pH = 7.4, with NaOH) before and following the addition of flunarizine or verapamil for 10 min.

Images were obtained by confocal microscopy (Meta Zeiss LSM 510, objective w.i. 63x, n.a. 1.2) in the line scan mode as previously explained. Image analyses were performed by homemade routines using IDL software (Research System Inc.). Images were corrected for the background fluorescence.

Statistical analysis

Pooled data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation except the result on INa where results are presented as mean ± SEM. For the effects of drugs over time, comparisons were performed using a one-way repeated-measures anova followed by a Bonferroni correction. For non-parametric comparisons, the Kruskal–Wallis test was used.

Materials

Flunarizine was supplied by Janssen Pharmaceutica N.V.; verapamil (Isoptin) and isoflurane was from Abbott, Europe; lidocaine from Braun Melsungen AG, Germany. ATX-II and all other chemicals were from Sigma. Channel, receptor and drug nomenclature follows Alexander et al. (2009).

Results

Antiarrhythmic effects of flunarizine

Flunarizine suppression

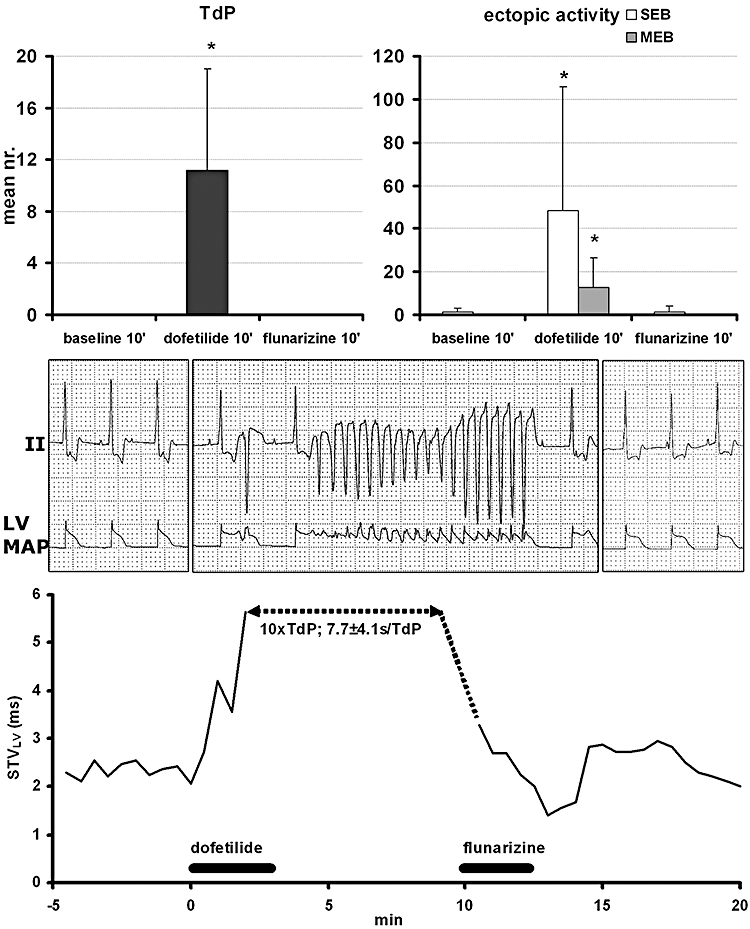

Dofetilide induced TdP with a median duration of 6.8 s, after 3.1 ± 1 min. After adding flunarizine, all arrhythmias disappeared with the exception of some SEBs in one dog (Figure 1 and Table 1). These anti-arrhythmic effects remained present for more than 10 min. Thereafter, some MEBs returned, albeit less severe. Electrophysiologically, dofetilide increased all repolarization parameters (QT, QTC, LVMAPD and RVMAPD) and STVLV before the first EB (2.5 ± 0.5 min. after start dofetilide). Flunarizine decreased the dofetilide-augmented STVLV and all the other repolarization parameters, to a level similar to baseline (Table 1 upper part and Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Upper panel: anti-arrhythmic effects of flunarizine (suppression) against dofetilide-induced TdP (left) and ectopic activity (right; as single ectopic beats, SEB and multiple ectopic beats, MEB) is shown with an individual example (middle part) of lead II electrocardiogram (ECG) and left ventricular monophasic action potential (LV MAP) recordings (printed at 10 mm·s−1 speed and calibrated at 1 mV per cm for ECG and 20 mV for the MAP recording) on scale paper in baseline (left), with TdP (middle) and after flunarizine. Lower panel illustrates continuous short-term variability (STVLV) quantification for this experiment. *P < 0.05 versus baseline. TdP, Torsade de Pointes.

Table 1.

Summary of electrophysiological parameters and arrhythmic events in flunarizine suppression and prevention experiments

| Baseline 1 | Dofetilide | Flunarizine | |

|---|---|---|---|

| RR | 1181 ± 87 | 1291 ± 140 | 1219 ± 251 |

| QT | 436 ± 44 | 566 ± 29* | 435 ± 36$ |

| QTC | 421 ± 49 | 553 ± 40* | 425 ± 38$ |

| LV MAPD | 355 ± 35 | 492 ± 53* | 367 ± 42$ |

| RV MAPD | 310 ± 32 | 395 ± 68* | 333 ± 30$ |

| ΔMAPD | 51 ± 28 | 97 ± 56* | 48 ± 32$ |

| STVLV | 1.8 ± 0.5 | 4.5 ± 1.5* | 1.5 ± 0.6$ |

| TdP | 0 ± 0 | 11 ± 8* | 0 ± 0$ |

| MEB | 0 ± 0 | 13 ± 14* | 0 ± 0$ |

| SEB | 1 ± 2 | 48 ± 58* | 1 ± 3$ |

| Baseline 2 | Flunarizine | Dofetilide | |

|---|---|---|---|

| RR | 1239 ± 329 | 1291 ± 390 | 1410 ± 462 |

| QT | 422 ± 51 | 380 ± 50* | 494 ± 92*# |

| QTC | 413 ± 51 | 369 ± 41* | 476 ± 77*# |

| LV MAPD | 299 ± 44 | 277 ± 36 | 380 ± 65*# |

| RV MAPD | 286 ± 39 | 275 ± 44 | 348 ± 73*# |

| ΔMAPD | 42 ± 27 | 22 ± 16 | 38 ± 42 |

| STVLV | 1.5 ± 0.6 | 1.0 ± 0.5* | 1.4 ± 0.5 |

| TdP | 0 ± 0 | 0 ± 0 | 0 ± 0 |

| MEB | 0 ± 1 | 0 ± 0 | 0 ± 0 |

| SEB | 3 ± 6 | 3 ± 5 | 6 ± 10 |

Maximal effects of flunarizine (5 min) in suppression experiments (upper part) and at the end of the infusion (2 min) in prevention experiments are shown (lower part). Arrhythmias are quantified as average number of events (TdP, MEB, SEB) per 10 min, except for the pretreatment with flunarizine (lower part) where after 5 min dofetilide was added. All electrophysiological parameters are expressed in ms and arrhythmias as average number per time interval.

P < 0.05 versus baseline;

P < 0.05 versus dofetilide;

P < 0.05 versus flunarizine pretreatment.

LV, left ventricle; MAPD, duration of the monophasic action potential; MEB, multiple ectopic beat; RV, right ventricle; SEB, single ectopic beat; STVLV, short term variability of repolarization, computed from LV MAPD; TdP, Torsade de Pointes.

Flunarizine prevention

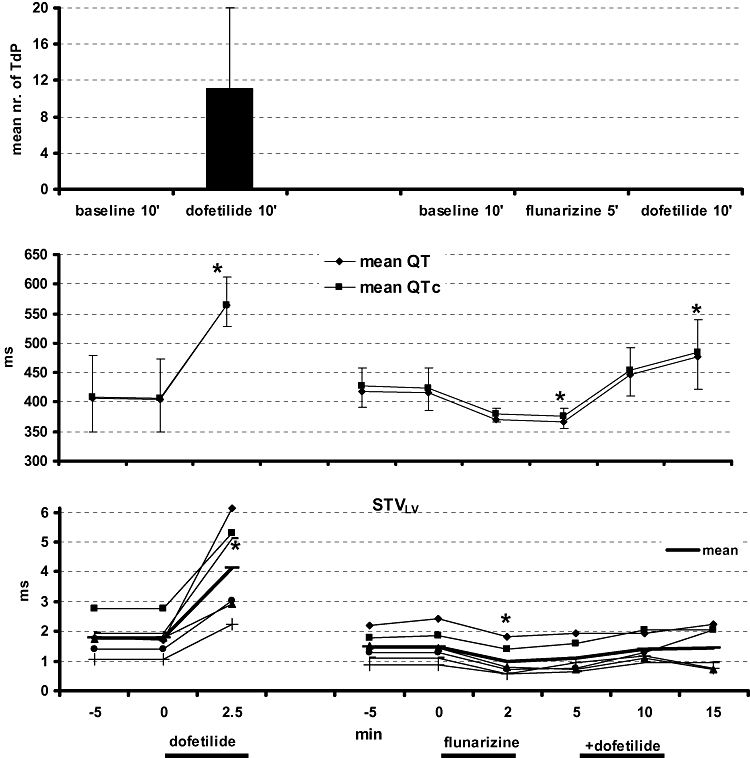

Pretreating the same animals with flunarizine resulted in complete prevention of TdP (Figure 2, upper part). During a 10 min. period, dofetilide could only induce few single EBs (6 ± 10 beats/10 min). Flunarizine significantly decreased baseline STVLV and QTc. After adding dofetilide, STVLV remained at a level similar to baseline, whereas an increase in QTc could not be prevented by this drug completely (Figure 2 and Table 1, lower part).

Figure 2.

TdP prevention (upper panel) with flunarizine is presented in two serial experiments, first dofetilide alone (left) and with flunarizine pretreatment (right). The effects on QT/QTc (middle part) and short-term variability (STVLV) in individuals as well as average (lower part) are plotted. TdP, Torsade de Pointes.

Effect of flunarizine on baseline cellular BVR and on dofetilide-induced EADs

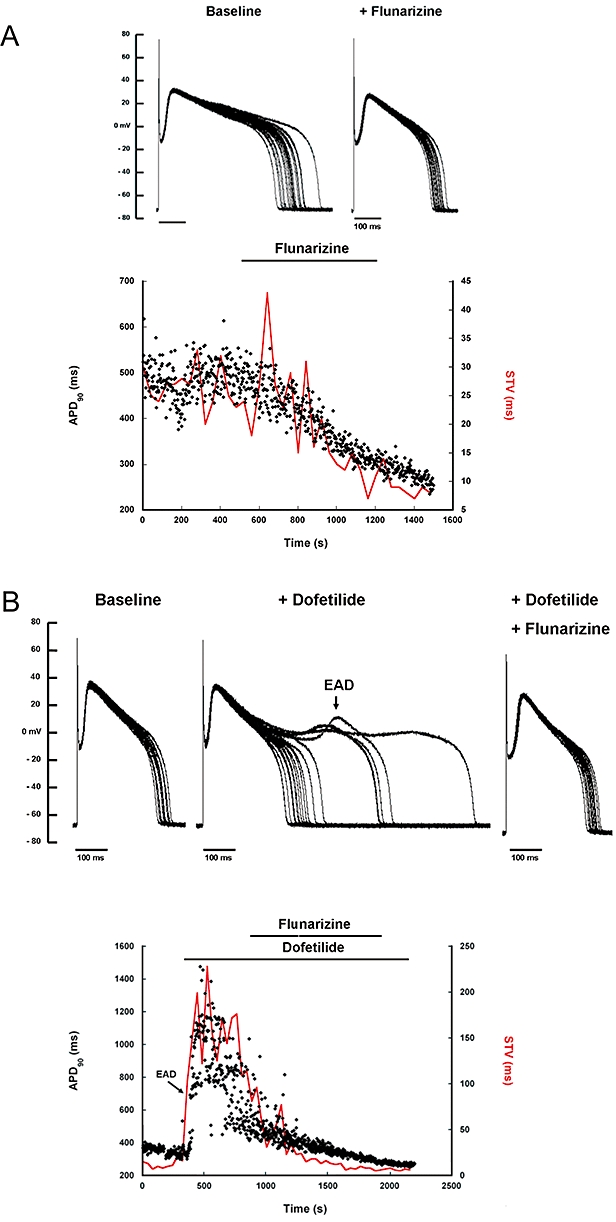

In untreated isolated myocytes from dogs with CAVB, flunarizine shortened (at 10 min) both APD (from 418 ± 116 ms in baseline to 312 ± 74 ms, P < 0.05) and cellular STVAPD (baseline 20 ± 10 ms to 11 ± 4 ms, P < 0.05). The time course of changes in APD and STV during an experiment is shown in Figure 3A.

Figure 3.

Anti-arrhythmic effects of flunarizine in isolated ventricular myocytes of the chronic AV-block (CAVB) dog are depicted. (A) 20 superimposed consecutive action potentials (APs) in baseline (left) and after flunarizine (right) as well as the time course of APD (dots) and short-term variability (STVAPD, continuous red line), baseline and with flunarizine perfusion are shown. (B) Similar, 20 superimposed APs in baseline (left), with dofetilide-induced EADs (arrow in middle panel) and after EADs suppression with flunarizine (right) and the temporal behaviour of APD and STVAPD are shown for this experiment. EADs, early after depolarizations.

In dofetilide-treated cells, APD increased from 337 ± 119 to 507 ± 153 ms (P < 0.05) and STV from 14 ± 14 to 65 ± 34 ms (P < 0.05). EADs occurred in eight from a total of nine cells. Addition of flunarizine suppressed all dofetilide-induced EADs (from 8/8 to 0/8, P < 0.05) and reversed APD (289 ± 60 ms) and cellular STV (11 ± 5 ms) to baseline values (P > 0.5 vs. baseline). A representative example is shown in Figure 3B.

Antiarrhythmic effects of verapamil

Verapamil suppression

Similar arrhythmia was seen with dofetilide in this group: TdP induction after 3.7 ± 1 min with a median duration of 7.1 s. All TdP and MEBs were suppressed, while some SEBs remained in three dogs (Table 2, upper part). Verapamil did not affect the dofetilide-prolonged repolarization duration (QT, QTc, LVMAPD and RVMAPD) but reduced the variability of repolarization STVLV to a level similar to control (Table 2, upper part).

Table 2.

Summary of electrophysiological parameters and arrhythmic events in verapamil suppression and prevention experiments

| Baseline 1 | Dofetilide | Verapamil | |

|---|---|---|---|

| RR | 1361 ± 190 | 1520 ± 210* | 1476 ± 166 |

| QT | 456 ± 67 | 611 ± 92* | 557 ± 97* |

| QTC | 424 ± 62 | 566 ± 87* | 516 ± 90* |

| LV MAPD | 349 ± 88 | 505 ± 110* | 466 ± 95* |

| RV MAPD | 305 ± 63 | 446 ± 135* | 392 ± 108* |

| ΔMAPD | 44 ± 39 | 72 ± 36 | 92 ± 92 |

| STVLV | 1.7 ± 0.4 | 3.2 ± 1.1* | 1.5 ± 0.7$ |

| TdP | 0 ± 0 | 9 ± 5* | 0 ± 0 |

| MEB | 0 ± 0 | 9 ± 4* | 0 ± 0 |

| SEB | 1 ± 1 | 50 ± 31* | 9 ± 15 |

| Baseline 2 | Verapamil | Dofetilide | |

|---|---|---|---|

| RR | 1285 ± 202 | 1212 ± 228 | 1464 ± 240# |

| QT | 442 ± 71 | 436 ± 57 | 651 ± 47*# |

| QTC | 417 ± 58 | 417 ± 41 | 611 ± 34*# |

| LV MAPD | 332 ± 68 | 328 ± 34 | 554 ± 77*# |

| RV MAPD | 324 ± 43 | 318 ± 37 | 545 ± 53*# |

| ΔMAPD | 32 ± 29 | 33 ± 16 | 30 ± 16 |

| STVLV | 1.3 ± 0.4 | 1.4 ± 0.6 | 2.3 ± 1.4 |

| TdP | 0 ± 0 | 0 ± 0 | 0.2 ± 0.4 |

| MEB | 0 ± 1 | 0.2 ± 0.4 | 3 ± 6 |

| SEB | 2 ± 4 | 1 ± 2 | 28 ± 44 |

Maximal effects of verapamil in suppression experiments (at 10 min, upper part) and at the end of the infusion (3 min) in prevention experiments are shown (lower part). All electrophysiological parameters are expressed in ms and arrhythmias (TdP, MEB, SEB) as average number per time interval.

P < 0.05 versus baseline;

P < 0.05 versus dofetilide;

P < 0.05 versus verapamil pretreatment.

LV, left ventricle; MAPD, duration of the monophasic action potential; MEB, multiple ectopic beat; RV, right ventricle; SEB, single ectopic beat; STVLV, short term variability of repolarization, computed from LV MAPD; TdP, Torsade de Pointes.

Verapamil prevention

Verapamil pretreatment also prevented TdP induction remarkably, only one self-terminating TdP was seen. However, dofetilide was still able to generate numerous SEBs and few MEBs (Table 2, lower part). Verapamil did not change baseline electrophysiological parameters, or STVLV. The duration of repolarization parameters (QT, QTc, LVMAPD and RVMAPD) was prolonged after adding dofetilide despite verapamil pretreatment. However, the variability of repolarization (STVLV) was not significantly increased after dofetilide (Table 2, lower part).

Analysis of the mode of action

Effects of flunarizine and verapamil on INa

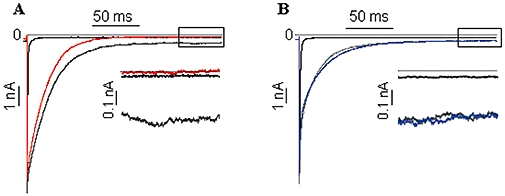

Figure 4 shows the effect of flunarizine (Figure 4A, left) and verapamil (Figure 4B, right) on late INa induced by ATX-II (Figure 4). Flunarizine (1 µM, Figure 4A) inhibited late INa by 94.4 ± 2.3%, n= 5 cells, P < 0.05). However, at a higher concentration (10 µM), flunarizine had no effect on peak INa (tonic block; 4.3 ± 3.0%, n= 4 cells, P > 0.05). In contrast to flunarizine, verapamil (Figure 4B, 10 µM) had no effect on either late INa (n= 5 cells, P > 0.05) or peak INa (tonic block; 10 µM, n= 6 cells (P > 0.05 and 30 µM, n= 4 cells, P > 0.05), as compared with control.

Figure 4.

Effects of flunarizine (left) and verapamil (right) on late INa: representative recordings of late INa from a single cell in the absence of drug (black line), during superfusion with 3 nM ATX-II (ATX, grey line) and during superfusion with 1 µM flunarizine (left; red line) or 10 µM verapamil (right; blue line). Insets: expanded traces (last 50 ms following depolarizing pulse) of late INa in the absence (black line) and presence of flunarizine (red line) or verapamil (blue line) respectively.

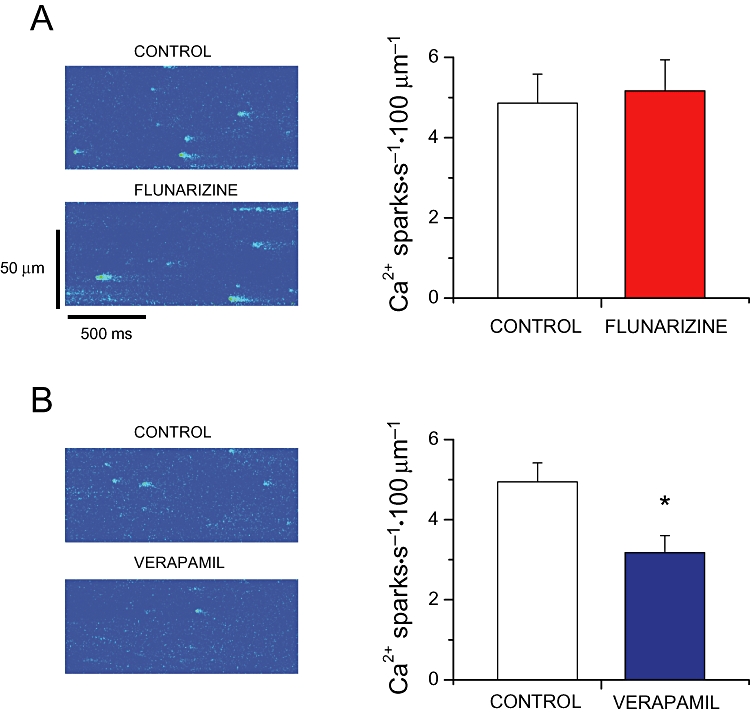

Ca2+ sparks study

Acute application of these drugs on the frequency of spontaneous Ca2+ sparks in cardiac myocytes expressing a gain-of-function mutation in the RyR2 was examined. Flunarizine (1 µM) did not change the frequency of spontaneous Ca2+ sparks in RyRR4496C cells (Figure 5A, P > 0.05). In contrast, verapamil (10 µM) significantly reduced spontaneous Ca2+ spark activity by ≈35% (Figure 5B, P < 0.005).

Figure 5.

(A) Left, representative line-scan images of spontaneous Ca2+ sparks recorded in a RyR2R4496C+/+ ventricular myocyte in the absence (top) or presence (bottom) of 1 µM flunarizine. Right, Ca2+ spark occurrence before (control) and during flunarizine (n= 8 cells). (B) Similar, images of spontaneous Ca2+ sparks in the absence (top) or presence (bottom) of 10 µM verapamil. Right panel shows the average data in control and with verapamil (n= 11 cells). *P < 0.05 versus control. RyR, ryanodine receptor.

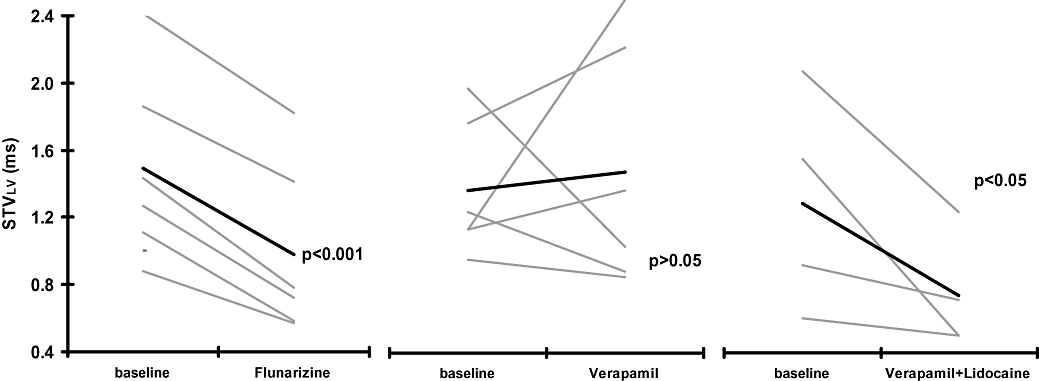

In vivo effects of verapamil in combination with lidocaine

To confirm that STVLV reduction in baseline by flunarizine was in part due to inhibition of late INa, the effects of verapamil combined with lidocaine were explored. The combination of these drugs shortened the duration of repolarization (QTc from 353 ± 35 to 306 ± 21 ms, P < 0.05) and STVLV was significantly reduced, effects similar to those seen with flunarizine alone (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Effects of flunarizine (left), verapamil (middle) and the combination of verapamil and lidocaine on baseline short-term variability (STVLV). Effects of these drugs on baseline STVLV is shown for individual animals (thin lines) and as a mean value for each group (thick line).

Discussion

The most important findings of this study can be summarized as follows: (i) both Ca2+ antagonists flunarizine and verapamil were equally and markedly effective in suppressing and preventing dofetilide-induced TdP; (ii) this anti-arrhythmic effect was reflected in STVLV, but not in QT or LV MAPD; (iii) flunarizine but not verapamil decreased BVR in baseline, which could be ascribed to its additional late INa blocking effect; and (iv) verapamil modestly reduced Ca2+ sparks, an effect not seen with flunarizine.

Repolarization-dependent ventricular arrhythmias and EADs

The common Ca2+ antagonism of verapamil and flunarizine was used to investigate whether they could improve repolarization reserve, as reflected in protection against dofetilide-induced TdP. These repolarization-dependent arrhythmias normally occur under conditions in which this reserve is ‘challenged beyond capacity’, as in the long QT syndromes, or in congestive heart failure (Tomaselli et al., 1994). Lately, it has been suggested that this reserve can be estimated by STV (Thomsen et al., 2004; 2006; 2007; Hinterseer et al., 2008; Oros et al., 2008). EADs and EAD-dependent triggered activity have been considered as possible initiation mechanisms for TdP in long QT syndromes (el-Sherif et al., 1996; Belardinelli et al., 2003). To develop new anti-arrhythmic drugs, it is important to understand possible targets that are key components of the generation of EADs, such as L-type Ca2+ channels, Na+ channels (with peak and late INa), RyR and its regulating unit calstabin2 (FKBP12.6), and the NCX. EADs have at least two different ways in which they may be generated: (i) window currents, either through the ICa,L or late INa; and (ii) NCX-mediated inward currents due to an abnormal Ca2+ release from the SR. The ICa,L has been studied extensively as block of ICa,L by verapamil or nitrendipine prevented EADs from developing (Marban et al., 1986; January et al., 1988) and as regional differences in the expression levels of L-type Ca2+ channels have implications for the origin of EADs (Sims et al., 2008). This effect may also explain why IKr blockade by verapamil (Zhang et al., 1999) and flunarizine are not pro-arrhythmic because an additional block of ICa,L protects the heart from developing EADs, despite the QT lengthening induced by IKr block (Bril et al., 1996). This balance between ICa,L recovery and ventricular repolarization serves also as a physiological stabilizer (Guo et al., 2008).

The second theory, the involvement of abnormal SR Ca2+ release in generating EADs, is more controversial (Volders et al., 1997; Antoons et al., 2007). Nevertheless there is evidence that DADs and EADs may occur in the same preparation (Marban et al., 1986; Priori and Corr, 1990; Volders et al., 1997; Song et al., 2008), suggesting a similar etiology. Moreover, EADs and calcium transients have been related (Hamlin and Kijtawornrat, 2008). Indirectly, activation of calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII) due to an increase in [Ca2+]i might facilitate both ICa,L and INa, thus inducing EADs and DADs (Anderson et al., 1998). Because of the number of actions of the drugs, the relevance of this alternative (for the conditional phase) was difficult to assess. However, measuring diastolic Ca2+ sparks known to underlie DAD generation is an interesting approach to address the question of whether flunarizine and verapamil inhibit the disturbed SR Ca2+ release events.

Calcium antagonists: flunarizine and verapamil

Flunarizine does not belong to the cardiovascular categories of Ca2+ antagonists. Clinically, the drug has been used to treat neurological disorders, such as migraine and has been termed a calcium overload blocker (van Zwieten, 1986). The latter implies that flunarizine may have an intracellular target. However, until now, only sarcolemmal effects have been described. Besides blocking three types of Ca2+ channels (Tytgat et al., 1991; 1996;), ICa,L (IC50= 4.6–10 µM), ICa,N (0.8 µM) and ICa,T (3.3–11 µM), flunarizine is also a potent IKr (5.7 nM) and IKs (0.7 µM) blocker (Trepakova et al., 2006).

Verapamil is known to block ICa,L (0.6–15.5 µM) (Hosey and Lazdunski, 1988), IKr (0.1 µM) (Zhang et al., 1999) and IKs (5.7–6.3 µM) (Aiba et al., 2005). According to the supplier, our dose of flunarizine will reach a total plasma concentration around 1.7 µM (828 ng·mL−1, MW 477.4) while, for verapamil, this value is around 0.5 µM (Fossa et al., 2002).

In susceptible dogs with CAVB, both drugs were very effective (100% efficacy) in preventing and terminating dofetilide-induced TdP. They were much more effective stronger than other drugs such as the late INa blockers, ranolazine and lidocaine, which were effective in approximately 60% of the animals (Antoons et al., 2010), whereas the IK,ATP agonist levcromakalim was slightly more effective (70%, unpublished data). This confirms that inhibition of ICa,L is a very effective way to treat dofetilide-induced TdP, assuming that no other actions are involved (see below).

Additional modes of action

In order to gain more insight in the mode of action of flunarizine and verapamil, we undertook cellular experiments to determine their possible action against late INa and Ca2+ sparks. Flunarizine but not verapamil blocked late INa, which could explain why flunarizine, but not verapamil, was effective against veratridine-induced contractures (Patmore et al., 1989).

Albeit modestly, verapamil (at high concentrations) but not flunarizine could reduce the frequency of diastolic Ca2+ sparks in a cell model expressing a gain-of-function mutation in the RyR2 responsible for abnormal Ca2+ leakage. These results show that the antiarrhythmic molecular mechanism of verapamil and flunarizine could involve different targets. Regarding flunarizine it is possible to discard an action of flunarizine on RyR2 activity. As mentioned, there is controversy concerning the proposition that SR Ca2+ leak may indirectly provide inward currents that contribute to induction of EADs (Fauconnier et al., 2005; Hamlin and Kijtawornrat, 2008). One way to study this is by application of drugs that specifically block this release, like ryanodine or K201. Unfortunately, both drugs do not have a high degree of specificity.

When evaluating the literature concerning ryanodine and its action on DADs or EADs, it becomes apparent that the results are not consistent. Ryanodine is known to be anti-arrhythmic against DADs and DAD-dependent VT (Marban et al., 1986; Priori and Corr, 1990). In dogs with CAVB, ryanodine (10 mg) was effective against drug-induced TdP, whereas ryanodine was not effective against cesium or ATX-II-induced EADs (Marban et al., 1986; Park et al., 1992; Song et al., 2008), but anti-arrhythmic against catecholamine-induced EADs (Priori and Corr, 1990). Ryanodine and flunarizine were both effective against acceleration-induced EADs (Burashnikov and Antzelevitch, 1998). Until there is a specific blocker for unconditional Ca2+ leak, it will be difficult to prove SR leakage to be part of the generation of EADs. It is evident however, that adding blocking properties against either late INa or Ca2+ sparks could generate more anti-arrhythmic ‘strength’. Future studies are necessary to evaluate which of the two additional actions is the most attractive.

Anti-arrhythmic action and STV

The anti-arrhythmic potential of flunarizine and verapamil was clearly reflected by the changes in STVLV. Its suppressive actions were associated with a reduction in STVLV, whereas the preventive effects could be seen in keeping STVLV at low(er) levels. Anti-arrhythmic properties of flunarizine were confirmed in vitro on drug-induced EADs and STVAPD. Thus, STV is an indicator of the ability of the heart to withstand a pro-arrhythmic challenge. However, the action on the other electrophysiological parameters differed. Flunarizine showed a pronounced action on repolarization parameters such as QTc and LV MAPD and cellular APD, whereas the effect of verapamil on repolarization time was much smaller or even absent.

Second, flunarizine decreased baseline STVLV, suggesting that this drug may increase repolarization reserve. This interpretation is consistent with the greater effect of verapamil combined with lidocaine on STVLV (Figure 6) and QT LV MAPD than verapamil alone.

The fact that flunarizine decreased APD/QTc while verapamil did not, could in part contribute to the mechanism by which flunarizine reduced STVLV or STVAPD. However, the contribution of APD to STVLV was not seen in the suppression experiments where verapamil shortened STV without a significant reduction in APD or QTc.

Study limitations

The results obtained in the SCN5A-HEK 293 cells and/or in myocytes isolated from the transgenic mouse model RyR2R4496C+/+ may differ from the results that could be obtained from myocytes isolated from CAVB dog hearts.

The blocking effect of verapamil on Ca2+ sparks was not very robust and attained at relatively high dosages. Whether this finding has therapeutic consequences is therefore unclear.

In conclusion, a robust anti-arrhythmic efficacy was seen with flunarizine and verapamil. This suppressive and preventive action of the drugs was reflected in STVLV or cellular STVAPD. Their different electrophysiological response may be related to different additional effects of the two drugs: flunarizine blocks late INa, whereas verapamil reduces Ca2+ sparks.

Acknowledgments

The study was supported by a grant from the EU FP6 (LSHM-CT-2005-018802, Contica), a Veni grant from the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (916.56.145) to G. Antoons, Agence National de la Recherche to AMG (ANR-09-GENO-034) and to SR (ANR-06-PHYSIO-004). PN is a Fellow of the Fondation pour la Recherche Medicale.

Within the Contica framework we received the knock-in mice RyR24496C+/+ from Drs S. G. Priori and C. Napolitano, Pavia, Italy.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- APD

action potential duration

- BVR

beat-to-beat variability of repolarization duration

- [Ca2+]i

intracellular calcium concentration

- CAVB

chronic AV-block

- DADs

delayed afterdepolarizations

- EADs

early after depolarizations

- ICa,L

L-type calcium current

- IKr

rapid component of the delayed rectifier current

- IKs

slow component of the delayed rectifier current

- late INa

persistent sodium current

- LV

left ventricle

- MAP

monophasic action potential

- MAPD

duration of the monophasic action potential

- MEBs

multiple ectopic beats

- NCX

sodium-calcium exchanger

- RV

right ventricle

- RyR

ryanodine receptor

- SEBs

single ectopic beats

- SR

sarcoplasmic reticulum

- STVAPD

short-term variability of repolarization, computed from cellular APD

- STVLV

short-term variability of repolarization, computed from LV MAPD

- TdP

Torsade de Pointes

- VTs

ventricular tachycardias

Conflicts of interest

SR and LB are employees of Gilead Sciences Inc.

References

- Aiba T, Shimizu W, Inagaki M, Noda T, Miyoshi S, Ding WG, et al. Cellular and ionic mechanism for drug-induced long QT syndrome and effectiveness of verapamil. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45:300–307. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.09.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander SPH, Mathie A, Peters JA. Guide to Receptors and Channels (GRAC), 4th edn. Br J Pharmacol. 2009;158(Suppl. 1):S1–S254. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00499.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson ME, Braun AP, Wu Y, Lu T, Wu Y, Schulman H, et al. KN-93, an inhibitor of multifunctional Ca++/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase, decreases early afterdepolarizations in rabbit heart. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1998;287:996–1006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antoons G, Volders PG, Stankovicova T, Bito V, Stengl M, Vos MA, et al. Window Ca2+ current and its modulation by Ca2+ release in hypertrophied cardiac myocytes from dogs with chronic atrioventricular block. J Physiol. 2007;579:147–160. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.124222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antoons G, Oros A, Beekman JDM, Engelen MA, Houtman MJ, Belardinelli L, et al. Late Na+ current inhibition by Ranolazine reduces Torsades de Pointes in the chronic atrioventricular block dog model. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:801–809. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.10.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belardinelli L, Antzelevitch C, Vos MA. Assessing predictors of drug-induced torsade de pointes. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2003;24:619–625. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2003.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bril A, Gout B, Bonhomme M, Landais L, Faivre JF, Linee P, et al. Combined potassium and calcium channel blocking activities as a basis for antiarrhythmic efficacy with low proarrhythmic risk: experimental profile of BRL-32872. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1996;276:637–646. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burashnikov A, Antzelevitch C. Acceleration-induced action potential prolongation and early afterdepolarizations. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 1998;9:934–948. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.1998.tb00134.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlsson L, Drews L, Duker G. Rhythm anomalies related to delayed repolarization in vivo: influence of sarcolemmal Ca++ entry and intracellular Ca++ overload. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1996;279:231–239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosio FG, Goicolea A, Lopez Gil M, Kallmeyer C, Barroso JL. Suppression of Torsades de Pointes with verapamil in patients with atrio-ventricular block. Eur Heart J. 1991;12:635–638. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a059952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Groot SH, Schoenmakers M, Molenschot MM, Leunissen JD, Wellens HJ, Vos MA. Contractile adaptations preserving cardiac output predispose the hypertrophied canine heart to delayed afterdepolarization-dependent ventricular arrhythmias. Circulation. 2000;102:2145–2151. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.17.2145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fauconnier J, Lacampagne A, Rauzier JM, Fontanaud P, Frapier JM, Sejersted OM, et al. Frequency-dependent and proarrhythmogenic effects of FK-506 in rat ventricular cells. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;288:H778–H786. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00542.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Velasco M, Rueda A, Rizzi N, Benitah JP, Colombi B, Napolitano C, et al. Increased Ca2+ sensitivity of the ryanodine receptor mutant RyR2R4496C underlies catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia. Circ Res. 2009;104:201–209. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.177493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fossa AA, DePasquale MJ, Raunig DL, Avery MJ, Leishman DJ. The relationship of clinical QT prolongation to outcome in the conscious dog using a beat-to-beat QT-RR interval assessment. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2002;302:828–833. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.035220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredj S, Sampson KJ, Liu H, Kass RS. Molecular basis of ranolazine block of LQT-3 mutant sodium channels: evidence for site of action. Br J Pharmacol. 2006;148:16–24. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallacher DJ, Van de Water A, van der Linde H, Hermans AN, Lu HR, Towart R, et al. In vivo mechanisms precipitating torsades de pointes in a canine model of drug-induced long-QT1 syndrome. Cardiovasc Res. 2007;76:247–256. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2007.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo D, Zhou J, Zhao X, Gupta P, Kowey PR, Martin J, et al. L-type calcium current recovery versus ventricular repolarization: preserved membrane-stabilizing mechanism for different QT intervals across species. Heart Rhythm. 2008;5:271–279. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2007.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamill OP, Marty A, Neher E, Sakmann B, Sigworth FJ. Improved patch-clamp techniques for high-resolution current recording from cells and cell-free membrane patches. Pflugers Arch. 1981;391:85–100. doi: 10.1007/BF00656997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamlin RL, Kijtawornrat A. Use of the rabbit with a failing heart to test for torsadogenicity. Pharmacol Ther. 2008;119:179–185. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2008.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinterseer M, Beekman BM, Thomsen MB, Lengyl Y, Schimpf R, Ulbrich M, et al. Increased Beat-to-Beat Variability of repolarization is associated with ventricular tachycardia in heart failure patients. Eur Heart J. 2008;29:185–190. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosey MM, Lazdunski M. Calcium channels: molecular pharmacology, structure and regulation. J Membr Biol. 1988;104:81–105. doi: 10.1007/BF01870922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- January CT, Riddle JM, Salata JJ. A model for early afterdepolarizations: induction with the Ca2+ channel agonist Bay K 8644. Circ Res. 1988;62:563–571. doi: 10.1161/01.res.62.3.563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonkman FA, Boddeke HW, van Zwieten PA. Protective activity of calcium entry blockers against ouabain intoxication in anesthetized guinea pigs. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1986;8:1009–1013. doi: 10.1097/00005344-198609000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marban E, Robinson SW, Wier WG. Mechanisms of arrhythmogenic delayed and early afterdepolarizations in ferret ventricular muscle. J Clin Invest. 1986;78:1185–1192. doi: 10.1172/JCI112701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oros A, Volders PG, Beekman JD, van der Nagel T, Vos MA. Atrial-specific drug AVE0118 is free of torsades de pointes in anesthetized dogs with chronic complete atrioventricular block. Heart Rhythm. 2006;3:1339–1345. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2006.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oros A, Beekman JD, Vos MA. The canine model with chronic, complete atrio-ventricular block. Pharmacol Ther. 2008;119:168–178. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2008.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park J, Danilo P, Rosen MR. Effects of flunarizine on impulse initiation in canine purkinje fibers. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 1992;3:306–314. [Google Scholar]

- Patmore L, Duncan GP, Spedding M. The effects of calcium antagonists on calcium overload contractures in embryonic chick myocytes induced by ouabain and veratrine. Br J Pharmacol. 1989;97:83–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1989.tb11927.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pogwizd SM, Schlotthauer K, Li L, Yuan W, Bers DM. Arrhythmogenesis and contractile dysfunction in heart failure: Roles of sodium-calcium exchange, inward rectifier potassium current, and residual beta-adrenergic responsiveness. Circ Res. 2001;88:1159–1167. doi: 10.1161/hh1101.091193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Priori SG, Corr PB. Mechanisms underlying early and delayed afterdepolarizations induced by catecholamines. Am J Physiol. 1990;258:H1796–H1805. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1990.258.6.H1796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Priori SG, Napolitano C, Tiso N, Memmi M, Vignati G, Bloise R, et al. Mutations in the cardiac ryanodine receptor gene (hRyR2) underlie catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia. Circulation. 2001;103:196–200. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.2.196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen MR, Danilo P., Jr Effects of tetrodotoxin, lidocaine, verapamil, and AHR-2666 on Ouabain-induced delayed afterdepolarizations in canine Purkinje fibers. Circ Res. 1980;46:117–124. doi: 10.1161/01.res.46.1.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- el-Sherif N, Caref EB, Yin H, Restivo M. The electrophysiological mechanism of ventricular arrhythmias in the long QT syndrome. Tridimensional mapping of activation and recovery patterns. Circ Res. 1996;79:474–492. doi: 10.1161/01.res.79.3.474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu W, Ohe T, Kurita T, Kawade M, Arakaki Y, Aihara N, et al. Effects of verapamil and propranolol on early afterdepolarizations and ventricular arrhythmias induced by epinephrine in congenital long QT syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1995;26:1299–1309. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(95)00313-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sims C, Reisenweber S, Viswanathan PC, Choi BR, Walker WH, Salama G. Sex, age, and regional differences in L-type calcium current are important determinants of arrhythmia phenotype in rabbit hearts with drug-induced long QT type 2. Circ Res. 2008;102:e86–100. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.173740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sipido KR, Volders PG, de Groot SH, Verdonck F, Van de Werf F, Wellens HJ, et al. Enhanced Ca(2+) release and Na/Ca exchange activity in hypertrophied canine ventricular myocytes: potential link between contractile adaptation and arrhythmogenesis. Circulation. 2000;102:2137–2144. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.17.2137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song Y, Shryock JC, Belardinelli L. An increase of late sodium current induces delayed afterdepolarizations and sustained triggered activity in atrial myocytes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;294:H2031–H2039. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01357.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomsen MB, Verduyn SC, Stengl M, Beekman JD, de Pater G, van Opstal J, et al. Increased short-term variability of repolarization predicts d-sotalol-induced torsades de pointes in dogs. Circulation. 2004;110:2453–2459. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000145162.64183.C8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomsen MB, Matz J, Volders PG, Vos MA. Assessing the proarrhythmic potential of drugs: current status of models and surrogate parameters of torsades de pointes arrhythmias. Pharmacol Ther. 2006;112:150–170. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2005.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomsen MB, Oros A, Schoenmakers M, van Opstal JM, Maas JN, Beekman JD, et al. Proarrhythmic electrical remodelling is associated with increased beat-to-beat variability of repolarisation. Cardiovasc Res. 2007;73:521–530. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2006.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomaselli GF, Beuckelmann DJ, Calkins HG, Berger RD, Kessler PD, Lawrence JH, et al. Sudden cardiac death in heart failure. The role of abnormal repolarization. Circulation. 1994;90:2534–2539. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.90.5.2534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trepakova ES, Dech SJ, Salata JJ. Flunarizine is a highly potent inhibitor of cardiac hERG potassium current. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2006;47:211–220. doi: 10.1097/01.fjc.0000200810.18575.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tytgat J, Pauwels PJ, Vereecke J, Carmeliet E. Flunarizine inhibits a high-threshold inactivating calcium channel (N-type) in isolated hippocampal neurons. Brain Res. 1991;549:112–117. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)90606-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tytgat J, Vereecke J, Carmeliet E. Mechanism of L- and T-type Ca2+ channel blockade by flunarizine in ventricular myocytes of the guinea-pig. Eur J Pharmacol. 1996;296:189–197. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(95)00691-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verduyn SC, Vos MA, Gorgels AP, van der Zande J, Leunissen JD, Wellens HJ. The effect of flunarizine and ryanodine on acquired torsades de pointes arrhythmias in the intact canine heart. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 1995;6:189–200. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.1995.tb00770.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volders PG, Kulcsar A, Vos MA, Sipido KR, Wellens HJ, Lazzara R, et al. Similarities between early and delayed afterdepolarizations induced by isoproterenol in canine ventricular myocytes. Cardiovasc Res. 1997;34:348–359. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(96)00270-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volders PG, Sipido KR, Vos MA, Kulcsar A, Verduyn SC, Wellens HJ. Cellular basis of biventricular hypertrophy and arrhythmogenesis in dogs with chronic complete atrioventricular block and acquired torsade de pointes. Circulation. 1998;98:1136–1147. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.98.11.1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vos MA, Gorgels AP, Leunissen JD, Wellens HJ. Flunarizine allows differentiation between mechanisms of arrhythmias in the intact heart. Circulation. 1990;81:343–349. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.81.1.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vos MA, Gorgels AP, Leunissen JD, van der Nagel T, Halbertsma FJ, Wellens HJ. Further observations to confirm the arrhythmia mechanism-specific effects of flunarizine. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1992;19:682–690. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S, Zhou Z, Gong Q, Makielski JC, January CT. Mechanism of block and identification of the verapamil binding domain to HERG potassium channels. Circ Res. 1999;84:989–998. doi: 10.1161/01.res.84.9.989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Zwieten PA. Differentiation of calcium entry blockers into calcium channel blockers and calcium overload blockers. Eur Neurol. 1986;25(Suppl. 1):57–67. doi: 10.1159/000116061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]