Abstract

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention funded seven states, including Kentucky, to clarify statewide death certification practices in sudden, unexpected infant death and compare state performances with national expectations. Accurate assignment of the cause and manner of death in cases of sudden, unexpected infant death is critical for accurate vital statistics data to direct limited resources to appropriate targets, and to implement optimal and safe risk reduction strategies. The primary objectives are to (1) Compare SUID death certifications recommended by the KY medical examiners with the stated cause of death text field on the hard copy death electronic death certificates and (2) Compare KY and national SUID rates. Causes of death for SUID cases recommended by the medical examiners and those appearing on the hard copy and electronic death certificates in KY were collected retrospectively for 2004 and 2005. Medical examiner recommendations were based upon a classification scheme devised by them in 2003. Coroners hard copy death certificates and the cause of death rates in KY were compared to those occurring nationally. Eleven percent of infants dying suddenly and unexpectedly did not undergo autopsy during the study interval. The KY 2003 classification scheme for SIDS is at variance with the NICHD and San Diego SIDS definitions. Significant differences in causes of death recommended by medical examiners and those appearing on the hard copy and electronic death certificates were identified. SIDS rates increased in KY in contrast to decreasing rates nationally. Nationwide adoption of a widely used SIDS definition, such as that proposed in San Diego in 2004 as well as legislation by states to ensure autopsy in all cases of sudden unexpected infant death are recommended. Medical examiners’ recommendations for cause of death should appear on death certificates. Multidisciplinary pediatric death review teams prospectively evaluating cases before death certification is recommended. Research into other jurisdictions death certification process is encouraged.

Keywords: Sudden infant death syndrome, Sudden unexplained infant death, Classification, Death certificates, Death scene investigation

Background

In 2004, approximately 4,500 cases of sudden, unexpected infant death (SUID) occurred in the United States [1]. A diagnosis of sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) was made in the majority and it remains the leading cause of postneonatal SUID [1–3], although that percentage has been decreasing during the past few years. Some have ascribed this to a diagnostic shift away from SIDS toward other designations such as “undetermined” or suffocation [4–7]. This shift has been partially attributed to greater consideration of medical histories and improved death scene investigations. Adherence to widely publicized SIDS definitions that mandate death scene investigation and postmortem examinations has probably contributed as well [8, 9].

In 1991, SIDS was defined by an expert panel convened by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) as “the sudden death of an infant under 1 year of age which remains unexplained after a thorough case investigation, including performance of a complete autopsy, examination of the death scene, and review of the clinical history [8]. In 2004, the NICHD definition of SIDS was refined by an international panel of experts as “the sudden, unexpected death of an infant under 1 year of age, with onset of the fatal episode apparently occurring during sleep, that remains unexplained after a thorough case investigation, including performance of a complete autopsy, and review of the circumstances of death and the clinical history” [9]. This general definition was then stratified into categories for research purposes and another category, unclassified sudden infant death (USID), was created for other deaths, e.g., those in which a postmortem examination was not undertaken.

There is increasing consensus that SIDS is the lethal intersection of the inherently unstable developmental physiology of a young infant rendered vulnerable as a result of an underlying abnormality, such as has been documented in the medullary serotonergic system [10–13], while exposed to environmental risk factors [14]. Since the technology and resources necessary to identify these subtle neuropathologic abnormalities that have been found in a large percentage of SIDS cases are unavailable to medical examiners, SIDS remains a diagnosis of exclusion in the practical world of forensic pathology.

In July 2003, the Kentucky medical examiners devised and implemented a classification scheme for SUID cases (Table 1) with definitions for SIDS that are at variance with the NICHD [8] and San Diego [9] definitions. For example, SIDS Group B in the 2003 KY scheme allows a diagnosis of SIDS in the absence of a death scene investigation whereas it is a required in the NICHD and San Diego definitions.

Table 1.

2003 KY classification for cases of sudden, unexplained infant death [19, p. 344]

| Sudden infant death syndrome category | Description |

|---|---|

|

Group A (Attributed to SIDS) |

“Classic” SIDS including: age 3 weeks to 6 months, sleeping alone in a standard crib, bassinet, playpen or safe-sleeping surface, and performance of a complete autopsy with appropriate laboratory studies, scene investigation, and case history review |

|

Group B (Consistent with SIDS) |

Most findings are consistent with SIDS, however an aspect is either lacking or questionable which may include infant’s age <3weeks or 6–12 months, bedsharing, unsafe or questionable bedding surface, no scene investigation |

|

Group C (Undetermined) |

Cases in which there is no anatomical, toxicological, or metabolic cause of death, although physical or historical evidence eliminates SIDS as the potential diagnosis. Cases in this category may include a questionable family or social history that cannot be reconciled by the examiner, such as evidence or documented history of previous abuse with the same caregiver; another simultaneous death, i.e., twins; a previous SIDS death in the immediate family; and trauma not accounted for by resuscitative efforts |

The Commonwealth of Kentucky (KY) has 120 counties, each with its own elected coroner and a fluctuating number of deputy coroners. The coroner/medical examiner system is a cooperative effort among forensic specialists. The coroners are charged with the responsibility of investigating and certifying the cause and manner of all deaths, including deaths in children less than 18 years old, under their statutory jurisdiction. In infant deaths, the coroner in each county conducts the death scene investigation, evaluates the sleep environment, collects evidence, gathers the medical and family history, and involves other investigating agencies when applicable. The medical examiners, working within four regional offices, request these documents from the coroners to supplement their autopsy findings from which they recommend to the coroner the cause and manner of death that should be placed on the death certificate. In KY, the coroner is the official certifier of death in cases of SUID.

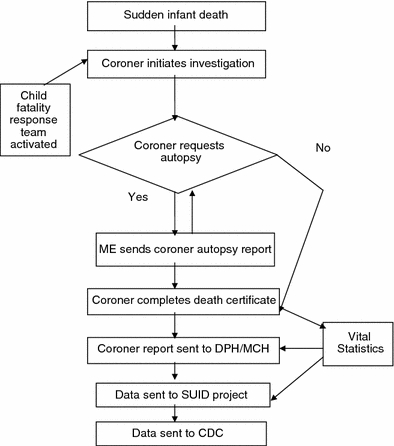

The hard copy death certificate completed by the coroner is then sent to the funeral director who submits it to the Office of Vital Statistics. Staff members in KY’s Vital Events Unit code specific demographic information from the certificate, such as gender, date of death, age, and cause of death, into the Super MICAR program of the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). The information is sent electronically to NCHS, which assigns an International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) code based upon the literal text field on the hard copy death certificate. If SIDS, whether subclassified as A, B, or C, written as “attributed to SIDS” or “consistent with SIDS” appears on the KY hard copy death certificate, then the NCHS automatically assigns the cause of death as SIDS with an ICD-10 code of R95 [15]. Finally, the NCHS sends the hardcopy death certificates back to KY’s Office of Vital Statistics who have these codes entered by a data entry vendor. All information is combined into one record, and the full electronic death certificate file is made available to various agencies (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

SUID Surveillance system in Kentucky

In 2006, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) funded seven states (Georgia, Kentucky, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Mexico, South Carolina, and Wisconsin) with the purpose of identifying differences in investigating, recording and collecting statewide SUID data in an effort to clarify statewide death certification practices and compare state performances with national expectations. The KY SUID pilot surveillance system was implemented in September 2006, building upon the infrastructure developed through the National Violent Death Reporting System. The supplemental SUID funding was utilized to collect population-based data. Figure 1 shows the flow of information to the state SUID database in KY.

We hypothesized that discrepancies in causes of death would be found between the KY medical examiners recommendations for cause of death and that found on the hard copy and electronic death certificates. We also hypothesized that SIDS rates in KY would differ from national rates. Thus the aims of our study are: (1) To compare SIDS death certifications recommended by the Kentucky medical examiners with the stated cause of death text field on the hard copy death certificates and with those cases coded as SIDS on the electronic death certificate file and (2) To compare KY and national SIDS rates.

Materials and Methods

For our pilot study, death certificate data were collected retrospectively for SUID cases that occurred in KY between January 1, 2004 and December 31, 2005. The causes of death recommended by the medical examiners were compared with those of the coroners on the hard copy death certificates and the ICD-10 codes assigned by the NCHS. The electronic death certificate file is the primary source for cause of death reporting to the Department for Public Health. Hard copy death certificates are stored in a vault and are not easily accessible as the retrieval process is labor intensive and limited to Office of Vital Statistics staff. Therefore, initial comparisons were made between the causes of death recommended by the medical examiners and that appearing on the electronic death certificates and then secondarily between medical examiner recommendations and hard copy death certificates. Comparisons were also made between hard copy death and electronic death certificates to determine if there was a lack of agreement between SIDS Groups due to typing error or inadvertent exclusion. Finally, data obtained from the Linked Birth/Infant Death Data in the CDC’s query system WONDER were used to compare trends in rates in the U.S. with KY.

Data Analysis

Proportions were compared using chi-square statistics and agreement among methods was measured by the Kappa statistic [16]. The Kappa statistic was used to assess agreement, where −1 = complete disagreement, 0 = random coincidence (or no agreement beyond that expected by chance) and 1 = complete agreement. SAS® software was used for data analysis.

Results

Availability of Cause of Death Recommendations and Certificates

Data for all of the cases are shown in Table 2. Autopsies were performed in 178 (89%) of the total 199 SUID cases in 2004 and 2005. The medical examiners’ did not recommend a cause of death to the coroners for the 21 cases that had not undergone autopsy. In 18 cases there was an autopsy and autopsy report, but the medical examiners’ final diagnostic pages were unavailable to the SUID project. Only 74 (37.2%) of the 199 requested hard copy death certificates were received. Medical examiner data for each of the four jurisdictions and the entire state were available for 160 (90%) of the 178 cases undergoing autopsies (electronic death certificates were available in all 199 cases).

Table 2.

Comparison of the causes of death (COD) recommended by the Kentucky medical examiner (KYME) and those appearing on the hard copy (HCDC) and electronic death (EDC) certificates, by jurisdiction, 2004–2005

| ME office | Autopsy not performed | ME final COD page unavailable | Evaluable cases | SIDS Group A (attributed to SIDS) | SIDS Group B (consistent with SIDS) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KYME | HCDC | EDCa | ME | HCDC | EDCa,b | ||||

| Jefferson County | 10 (48%) | 9 (50%) | 55 (35%) | 7 (13%) | 0 | 30 (55%) | 27 (49%) | 0 | 0 |

| Frankfort Office | 8 (38%) | 7 (39%) | 74 (46%) | 17 (23%) | 24 (100%) | 51 (69%) | 35 (47%) | 26 (96%) | 1 (1%) |

| Western Office | 2 (10%) | 1 (5.5%) | 16 (10%) | 3 (19%) | 0 | 9 (56%) | 6 (38%) | 1 (4%) | 0 |

| Northern Office | 1 (5%) | 1 (5.5%) | 15 (9%) | 3 (20%) | 0 | 11 (73%) | 8 (53%) | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 21 | 18 | 160 | 30 | 24 | 101 | 76 | 27 | 1 |

aCases given ICD-10 code of R95 on EDC

bOne case coded as “R95-B” on the EDC even though an ICD-10 code for SIDS B does not exist

The number of autopsies in each jurisdiction is proportional to the size of the population in each of the geographical regions of medical examiner office coverage. The Frankfort and Louisville offices have jurisdiction over the two most populous cities in KY while the Northern and Western offices cover more rural areas, thus accounting for the varying percentage of available medical examiner data. The number of cases without an autopsy and the number of cases with an autopsy, but not a medical examiner recommendation, varied by less than one case in each of the four jurisdictions suggesting the presented data are valid (Table 2).

Comparison of Medical Examiners’ Cause of Death Recommendations with the Hard Copy and Electronic Death Certifications

The greatest disparity in classification centered on SIDS Group B or “consistent with SIDS.” This cause of death was recommended in 47.5% of cases by the medical examiners, but appeared on just 36.5% of the hard copy death certificates and only once was SIDS Group B identified among the R95 codes found in the electronic death certificate file (Table 3).

Table 3.

Kentucky medical examiner recommendations compared to electronic and hard copy death certifications in SUID cases, 2004–2005

| Cause of death | Percent of cases | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Medical examiner recommendation (%) | Hard copy death certificatea (%) | Electronic death certificateb (%) | |

| SIDS A | 18.75 | 32.43 | 57.29 |

| SIDS B | 47.5 | 36.49 | 0.50 |

aHard copy death certificates are available in only 74 cases

bElectronic death certificates are available for all 199 cases with and without autopsies

SIDS Group A is recommended by the medical examiners as the cause of death at a rate about one half that which appears on the hard copy death certificate (18.8 vs. 32.4%, respectively). And, SIDS Group A is listed as the cause of death on the electronic death certificates three times more commonly than the rate recommended by the medical examiners (57.3 vs. 18.8%, respectively). In other words, the percentage of “classic” SIDS cases appearing on Kentucky’s electronic death certificates was significantly greater (P < 0.0001) than the percentage the medical examiners had designated as “classic” SIDS cases. Conversely, SIDS Group B is recommended by the medical examiners in nearly half of the cases compared to less than 1% of the electronic death certificates (47.5 vs. 0.50%, respectively). SIDS Group B was consistently the most frequent classification in ME offices statewide.

There is slight agreement when the medical examiners recommendations are compared with the hard copy death certificates (Kappa = 0.16 [95% CI: 0.078, 0.39] for SIDS Group A and 0.25 for SIDS Group B [95% CI: 0.021, 0.47]. When comparing the overall assessment of SUID classification within the medical examiners’ recommendations with the electronic death certificates, the Kappa is 0.39; [95% CI: 0.31, 0.47] indicating fair agreement; the Kappa for SIDS Group A is 0.24 [95% CI: 0.15, 0.32] indicating slight to fair agreement. The Kappa for SIDS Group B is 0.01 [95% CI: −0.013, 0.041] indicating poor agreement. When comparing the hard copy death certificates with the electronic death certificates, the Kappa for SIDS Group A is 0.43 [95% CI: 0.27, 0.59] and for SIDS Group B is 0.12 [95% CI: −0.033, 0.27], representing fair and unusually low agreement, respectively.

Although there were no classifications with perfect agreement between the medical examiner recommendations and the death certificates; substantial agreement occurred with Group C/Undetermined and with the “Other SUIDs” group.

Comparison of KY and National Rates of Sudden Unexpected Infant Death

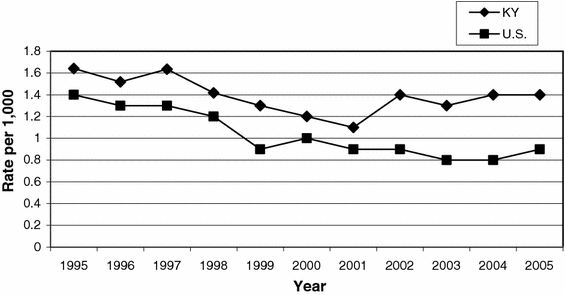

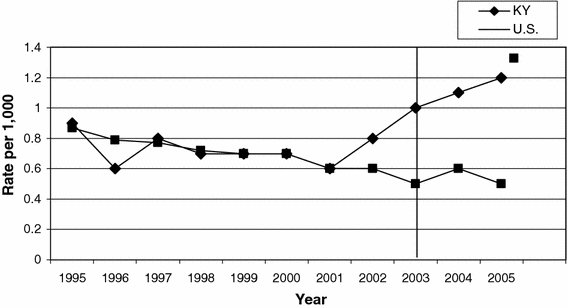

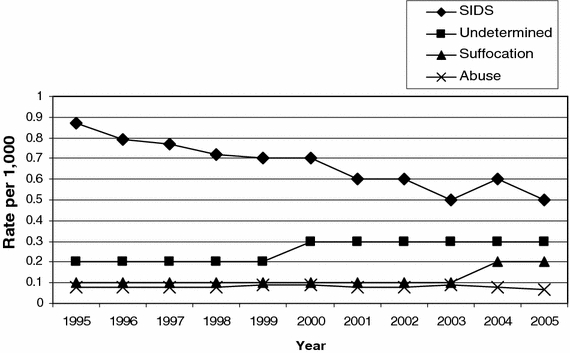

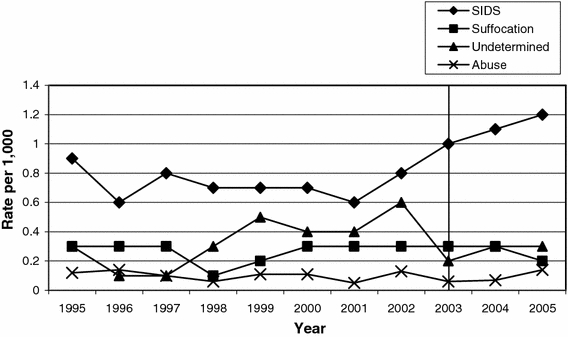

Figures 2, 3, 4, and 5 show infant death rates from 1995 through 2005 in KY and the U.S. While there is some parallel in overall SUID rates over this interval, SIDS rates have diverged upward in KY and downward in the U.S. Deaths occurring as a result of inflicted injuries remained relatively stable in KY and nationally. Rates of Undetermined causes of death went up in 2002 and have remained stable in the U.S., however, in KY they began to increase in 1998 peaking in 2002 from which time they declined. In KY rates of suffocation increased in 1998 from which time they leveled off; in comparison, suffocation rates in the U.S. were low for many years, increased in 2003 and then leveled off.

Fig. 2.

Rates of sudden, unexpected infant deaths in Kentucky and the U.S., 1995–2005

Fig. 3.

SIDS rates in Kentucky and the U.S., 1995–2005

Fig. 4.

SIDS, suffocation, abuse, and undetermined rates in the U.S., 1995–2005

Fig. 5.

SIDS, suffocation, abuse, and undetermined rates in KY, 1995–2005

Discussion

Several findings have emerged from our analysis. In contrast to other states, such as California, for example, where autopsies are mandated by statute and performed on nearly every infant dying suddenly and unexpectedly, autopsies were not performed on approximately 11% of such cases in KY. Although coroners are mandated to perform “postmortem investigations,” the current KY statute does not require an autopsy in which case death certification occurs without the recommendation of a medical examiner. Thus, the likelihood of incorrectly identifying the cause of death, be it SIDS, other natural causes, or inflicted or accidental injuries, is increased. With incorrect diagnoses, state vital statistics will be skewed. And appropriate counseling for planned future pregnancies may not be provided to the surviving parents.

The KY 2003 classification scheme for SIDS (Table 1) is at variance with the widely accepted NICHD SIDS definition[8] published in 1991 as well as the increasingly adopted San Diego definition published in 2004 [9]. Consequently, a sudden unexpected infant death not subjected to death scene investigation can be classified as SIDS in KY under this classification system. Since reports by caretakers regarding the scene are not always accurate [17], death scene investigation is critically important. For example, infant deaths caused by asphyxia may not be accompanied by diagnostic postmortem findings yet the scene investigation may identify an unsafe sleep environment that explains the cause of death.

The KY system of death certification begins with the medical examiner giving their cause and manner of death recommendations to the coroner, who has the legal authority to reject them but is still responsible for completing the hard copy death certificate. The death certification process concludes with NCHS that assigns an ICD-10 code based on information appearing on the hard copy death certificate. Given the different criteria for SIDS in the KY, NICHD, and San Diego definitions, it is not surprising there are significant disparities between the medical examiners recommendations and what is being coded as SIDS by the NCHS.

As alluded to above, the combination of the rates in which autopsies are not done in KY, the KY classification scheme for SUID cases, and the lack of consistency between the recommendations of the medical examiners and the cause of death appearing on the electronic death certificates inevitably create vital statistics data that are inaccurate and cannot be compared with confidence to those from other statewide or national jurisdictions. This seems to be borne out in diverging rates of infant death from different causes between KY and the U.S (Figs. 2, 3, 4, 5). Further, given the limited resources available to address efforts to reduce rates of infant death, any skewing of vital statistics mortality data allows the possibility if not the probability of misdirecting funds to inappropriate target areas. Others have emphasized the consequences of inconsistent and inappropriate definitions of SIDS as well [18].

Our study has limitations. It is retrospective and relies solely upon information provided on death forms completed by the medical examiners and the death certificates completed by the coroners and the ICD-10 code assigned by the NCHS. Investigation variables were inconsistent and often incomplete; autopsy variables were present much more consistently than death scene information, but autopsies weren’t always performed or medical examiner recommendations were not always completed, leaving a deficit in the data. Since almost all of the available hard copy death certificates emanated from autopsies performed in the Frankfort ME office, responsible for central and eastern Kentucky, the results are skewed towards them and away from other jurisdictions. How this may have affected the hard copy death certificate results had the reporting been more consistent is unknown.

The vulnerability of a pilot study, as ours is, to missing and/or inaccurate data is another important limitation given such studies are often used as the basis for a more comprehensive and inclusive surveillance system. Further, the hard copy death certificates more closely reflect the medical examiner’s recommendations compared to the electronic death certificates in which almost all cases of the SIDS Group A and B distinctions were lumped together as SIDS and coded as R95. Nevertheless, assessment of a pilot study can provide the context in which to assess the feasibility of collecting uniform, statewide or nationwide data and to recommend improvements, efficiency and usefulness to pilot participants and future project participants. Kentucky’s statewide pilot project has broader implications than the seemingly provincial study of one state’s SUID surveillance system. First, this study provides a detailed state-level data quality evaluation template, which the other seven funded states and potential future states might use to evaluate discrepancies in SUID classifications. Secondly, states with decentralized death investigation systems might take this evaluative model and transpose it for replication in all death classifications of all ages.

In conclusion, our study leads to several recommendations, including, first, nationwide adoption of a widely used SIDS definition, such as that proposed in San Diego in 2004; second, implementation of legislation to ensure autopsy in all cases of sudden unexpected infant death; third, the medical examiners’ recommendations for causes of death should appear on all death certificates under their jurisdiction; fourth, multidisciplinary pediatric death review teams should prospectively evaluate infant and childhood cases before death certification is recommended; and last, research into other jurisdictions’ death certification process is encouraged in order to improve certification of the causes and manners of sudden unexpected infant death.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (424128 to S.W., National Violent Death Reporting System, SUID pilot project, supplemental funding). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of CDC. The CJ Foundation for SIDS and First Candle/SIDS Alliance provided funding support to this study. The authors wish to thank Dr. Carrie Shapiro-Mendoza for her guidance, support and editorial contribution. Sincerest gratitude is extended to the Kentucky medical examiners and coroners for their support.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Abbreviations

- SUID

Sudden, unexpected infant death

- SIDS

Sudden infant death syndrome

- CDC

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- SUIDIRF

SUID investigation reporting form

- ME

Medical examiner

- DC

Death certificate

- ICD-10

International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision

- HCDC

Hard copy death certificate

- NCHS

National Center for Health Statistics

- NICHD

National Institute of Child Health and Human Development

References

- 1.Hunt CE, Hauck FR. Sudden infant death syndrome. CMAJ. 2006;174:1861–1869. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.051671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moon RY, Horne RS, Hauck FR. Sudden infant death syndrome. Lancet. 2007;370:1578–1587. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61662-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Academy of Pediatrics Task Force on Sudden Infant Death Syndrome The changing concept of sudden infant death syndrome: Diagnostic coding shifts, controversies regarding the sleeping environment, and new variables to consider in reducing risk. Pediatrics. 2005;116:1245–1255. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Malloy MH. Trends in postneonatal aspiration deaths and reclassification of sudden infant death syndrome: Impact of the “Back to Sleep” program. Pediatrics. 2002;109:661–665. doi: 10.1542/peds.109.4.661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Malloy MH, MacDorman M. Changes in the classification of sudden unexpected infant deaths: United States, 1992–2001. Pediatrics. 2005;115:1247–1253. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-2188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moore, B. M., Fernbach, K. L., Finkelstein, M. J., & Carolan, P. L. (2008). Impact of changes in infant death classification on the diagnosis of sudden infant death syndrome. Clinical Pediatrics (Phila). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Shapiro-Mendoza CK, Tomashek KM, Anderson RN, Wingo J. Recent national trends in sudden, unexpected infant deaths: More evidence supporting a change in classification or reporting. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2006;163:762–769. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Willinger M, James LS, Catz C. Defining the sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS): Deliberations of an expert panel convened by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. Pediatric Pathology. 1991;11:677–684. doi: 10.3109/15513819109065465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krous HF, Beckwith JB, Byard RW, et al. Sudden infant death syndrome and unclassified sudden infant deaths: A definitional and diagnostic approach. Pediatrics. 2004;114:234–238. doi: 10.1542/peds.114.1.234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Panigrahy A, Filiano J, Sleeper LA, et al. Decreased serotonergic receptor binding in rhombic lip-derived regions of the medulla oblongata in the sudden infant death syndrome [In Process Citation] Journal of Neuropathology and Experimental Neurology. 2000;59:377–384. doi: 10.1093/jnen/59.5.377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kinney HC, Filiano JJ, White WF. Medullary serotonergic network deficiency in the sudden infant death syndrome: Review of a 15-year study of a single dataset. Journal of Neuropathology and Experimental Neurology. 2001;60:228–247. doi: 10.1093/jnen/60.3.228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kinney HC, Randall LL, Sleeper LA, et al. Serotonergic brainstem abnormalities in Northern Plains Indians with the sudden infant death syndrome. Journal of Neuropathology and Experimental Neurology. 2003;62:1178–1191. doi: 10.1093/jnen/62.11.1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Paterson DS, Trachtenberg FL, Thompson EG, et al. Multiple serotonergic brainstem abnormalities in sudden infant death syndrome. JAMA. 2006;296:2124–2132. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.17.2124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Filiano JJ, Kinney HC. A perspective on neuropathologic findings in victims of the sudden infant death syndrome: The triple-risk model. Biology of the Neonate. 1994;65:194–197. doi: 10.1159/000244052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sudden, Unexplained Infant Death Initiative (SUIDI): Cause of Death Diagnosis. Available at http://www.cdc.gov/SIDS/deathscene.htm. Accessed on 12/1/08.

- 16.SAS software, Version 9.1 of the SAS System. Copyright 2002-2003. SAS Institute Inc. SAS and all other SAS Institute Inc. product or service names are registered trademarks or trademarks of SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA.

- 17.Byard RW, Jensen LL. How reliable is reported sleeping position in cases of unexpected infant death? Journal of Forensic Sciences. 2008;53:1169–1171. doi: 10.1111/j.1556-4029.2008.00813.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Byard RW, Marshall D. An audit of the use of definitions of sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) Journal of Forensic Legal Medicine. 2007;14:453–455. doi: 10.1016/j.jflm.2006.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shields LB, Hunsaker JC, III, Corey TS, Stewart D. Is SIDS on the rise? The Journal of Kentucky Medical Association. 2007;105:343–353. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]