Abstract

Previous studies have shown that increased vascularity is associated with haematogenous metastasis and poor prognosis in gastric cancer. The role of mast cells in gastric cancer angiogenesis has not been clarified completely. In this study, we correlated microvascular density and tryptase- and chymase-positive mast cells with histopathological type in gastric cancer. Specimens of primary gastric adenocarcinomas obtained from 30 patients who had undergone curative gastrectomy were investigated immunohistochemically by using anti-CD31 antibody to stain endothelial cells and anti-tryptase and anti-chymase antibodies to stain mast cells. The results showed that stage IV gastric carcinoma has a higher degree of vascularization than other stages and that both tryptase- and chymase-positive mast cells increase in parallel with malignancy grade even if the density of chymase-positive mast cells was significantly lower than the density of tryptase-positive mast cells and is highly correlated with the extent of angiogenesis. This study has demonstrated that mast cell density correlates with angiogenesis and progression of patients with gastric carcinoma. Understanding the mechanisms of gastric cancer angiogenesis provides a basis for a rational approach to the development of an antiangiogenic therapy in patients with this malignancy.

Keywords: angiogenesis, chymase, gastric cancer, mast cells, tryptase, tumour progression

Several studies suggest that solid tumour growth to a clinically relevant size depends on an adequate blood supply. Solid tumours recruit blood vessels from neighbouring tissue by angiogenesis with the sprouting of capillaries from pre-existing vessels that migrate into the tumour and form a new vascular network (Ribatti & Vacca 2008). Prevascular tumours may remain dormant in situ for months to years, then the “switching” of a subgroup of prevascular tumour cells to an angiogenic phenotype enables rapid growth, progression and metastasis (Ribatti et al. 2007).

Previous studies have shown that increased vascularity is associated with haematogenous metastasis and poor prognosis of gastric cancer (Maeda et al. 1995; Tanigawa et al. 1996, 1997a,b). Maeda et al. (1996) showed that increasing microvessel counts correlated with lymph node metastasis, hepatic metastasis and poor prognosis. These findings are similar to a study on 55 patients with intestinal-type gastric cancer where microvessel counts were associated with poor prognosis and tumour progression (Araya et al. 1997). In 53 intestinal-type and 38 diffuse-type gastric cancers, vessel count was significantly higher in intestinal-type tumours than in diffuse-type tumours (Takahashi et al. 1996).

Among the growth factors involved in the angiogenic response in gastric carcinoma, Maeda et al. (1996) reported that vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) may be a good prognostic indicator. VEGF and fibroblast growth factor-2 (FGF-2) expression was significantly higher in intestinal-type tumours than in diffuse-type tumours. VEGF expression was correlated with tumour vessel counts in specimens from patients with intestinal-type tumours and both vessel count and VEGF expression correlated with stage of disease in patients with intestinal-type tumours, but did not in those with diffuse-type tumours (Takahashi et al. 1996). Takahashi et al. (1998) examined gastric cancer samples from 93 patients and found that tumours with both high VEGF and platelet derived endothelial cell growth factor (PD-ECGF) expression demonstrated higher vessel counts than tumours with high expression of either factor alone. In intestinal-type gastric cancer, PD-ECCF and VEGF may be additive or synergistic in their ability to induce angiogenesis in these tumours. VEGF and its receptors 1 and 2 (VEGFR-1 and VEGFR-2) are expressed widely in gastric cancer and their overexpression is associated with intratumoural angiogenesis and metastases to distant organs (Maehara et al. 2000; Zhang et al. 2002).

Saito et al. (1999) demonstrated that the levels of transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1) correlated with the progression of disease and prognosis in patients with gastric carcinoma and that TGF-β1 may be correlated with angiogenesis through an up-regulation of VEGF expression. Etoh et al. (2001) have detected angiopoietin-2 (Ang-2) in endothelial and cancer cells of both intestinal and diffuse type of gastric cancer. Immunohistochemical analysis revealed that Ang-2 was expressed by both endothelial cells and cancer cells. In addition, Ang-2 transfected cancer cells implanted orthotopically into the stomachs of nude mice developed highly metastatic tumours with hypervascularity as compared with controls (Etoh et al. 2001). Kitadai et al. (1999) have demonstrated that culture media from interleukin-8 (IL-8) transfected gastric cancer cells stimulated endothelial cells proliferation and that orthotopic implantation of these cells into nude mice led to rapidly growing, highly vascular neoplasms as compared with control cells. IL-8 was highly expressed by most gastric cancer samples examined in vivo and correlated with vascular density (Kitadai et al. 1998). We have previously demonstrated that stage IV gastric carcinoma has a higher degree of vascularization than other stages and that erythropoietin receptor (EpoR) expression in both endothelial and tumour cells increases in parallel with malignancy grade and is highly correlated with the extent of angiogenesis (Ribatti et al. 2003a).

There is increasing evidence to support the view that angiogenesis and inflammation are mutually dependent (Ribatti & Crivellato 2009a). During inflammatory reactions, immune cells, including macrophages, neutrophils, lymphocytes and mast cells, synthesize and secrete pro-angiogenic factors that promote neovascularization. On the other hand, the newly formed vascular supply contributes to the perpetuation of inflammation by promoting the migration of inflammatory cells to the site of inflammation. Tumour cells are surrounded by an infiltrate of inflammatory cells, which communicate via a complex network of intercellular signalling pathways, mediated by surface adhesion molecules, cytokines and their receptors. Accordingly, immune cells cooperate and synergize with stromal cells as well as malignant cells in stimulating endothelial cell proliferation and blood vessel formation (Ribatti et al. 2006).

A significant increase in mast cells number has been observed in malignant tumours, in both experimental models and human specimens (Ribatti & Crivellato 2009b) and a close relationship has been established between angiogenesis, mast cell number and tumour growth (Ribatti et al. 2004). In human tissues, at least two mast cell phenotypes can be distinguished immunocytochemically by their neutral protease content, the MCT phenotype containing only tryptase and the MCTC phenotype containing tryptase, chymase carboxypeptidase A3 and cathepsin G (Schwartz 2006).

In this study, we have investigated immunohistochemically the correlation between CD31 expression and tryptase- and chymase-positive mast cells and we have correlated these parameters with histopathological type in gastric cancer.

Materials and methods

Patient population and tumours

Specimens of primary gastric adenocarcinomas and their paired adjacent normal gastric mucosa were obtained from 30 patients who had undergone curative gastrectomy. None of these patients received preoperative treatment such as radiation and chemotherapy. There were 16 male patients and 14 female patients, and their ages ranged from 40 to 75 years. Tumours were divided into two histological subgroups: well-differentiated type, including papillary and tubular adenocarcinomas, and poorly differentiated type, including signet ring cell carcinomas and mucinous adenocarcinomas. According to histological stage, five patients had stage I disease, eight had stage II disease, eight had stage III disease and nine had stage IV disease. Twenty control specimens were taken from non-tumour gastric mucosa without hyperplasia or atypical hyperplasia at 5 cm away from the edge of a tumour specimen. Tissue samples were fixed in formalin and embedded in paraffin according to standard procedures. 4-μm-thick sections were cut and mounted on glass slides.

Immunohistochemistry

Three murine monoclonal antibodies (MAb) against the endothelial cell marker CD31 (MAb 1A10; Dako, Glostrup, Denmark) and against mast cell markers tryptase and chymase (Mab AA1, Dako, and, respectively, MabCC1, Novocastra Laboratories Ltd, Newcastle, UK) were used in this study. Briefly, sections were collected on 3-amino-propyl-triethoxysilane coated slides, deparaffinized by the xylene-ethanol sequence, rehydrated in a graded ethanol scale and in Tris-buffered saline (TBS, pH 7.6) and incubated overnight at 4 °C with the MAb 1A10 (1:25 in TBS), after prior antigen retrieval by enzymatic digestion with Ficin (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA) for 30 min at room temperature. The immunodetection was performed with alkaline phosphatase anti-alkaline phosphatase (APAAP, Dako) and Fast Red as chromogen, followed by haematoxylin counterstaining. A preimmune serum (Dako) replacing the primary antibody served as negative control.

Image analysis methods

Computer-assisted image analysis was performed to evaluate the areal density of CD31-, tryptase- and chymase-positive regions in the tissue samples. The image analysis system included a light microscope (DM-R; Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany) and a high-resolution digital camera (DC200; Leica Microsystems) transmitting image data to a PC equipped with appropriate software for image acquisition and analysis (QWin; Leica Microsystems, Cambridge, UK). The images of four 200× magnifications random fields for each of three sections per sample were then acquired, processed to correct shading and enhance the contrast and stored as TIFF files. Images were analysed according to a previously detailed procedure (Guidolin et al. 2008). Briefly, specifically immunostained structures were identified by selecting the pixels with colour hue in a specified yellow-orange range (to exclude all the blue haematoxylin stained nuclei) and brightness lower than the mean brightness level exhibited by the negative control sections minus three standard deviations (thus excluding the unspecific staining). The total area of the identified structures was then measured and expressed as percentage of the total area of the analysed field.

The mean distance of the immunopositive structures from gastric gland profiles was evaluated as previously reported (Guidolin et al. 2006). The procedure involved the interactive tracing of the gland profiles to obtain a binary image of these structures and the calculation of its ‘distance transform’. This algorithm provides a map where each pixel is labelled with a value corresponding to its distance from the nearest pixel belonging to a gland profile. From these values, the mean distance from gland of the immunopositive structures was then evaluated.

Results

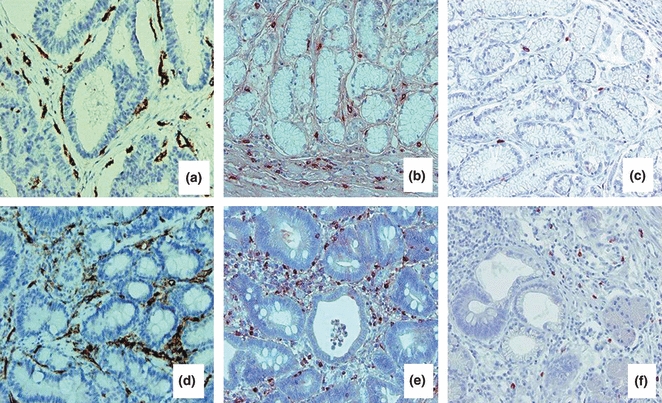

We have focused our morphological and morphometric analyses on the area immediately around gastric glands, where CD31-positive blood vessels and tryptase- and, respectively, chymase-positive mast cells are more numerous in bioptic specimens of stage IV gastric cancer (Figure 1) as compared with stage III (not shown) and respectively stages II (Figure 1) and I (not shown). Moreover, in all the stages, the number of chymase-positive mast cell was significantly lower than the number of tryptase-positive mast cells.

Figure 1.

Immnohistochemical staining for CD31, tryptase and chymase in stage II (a–c) and stage IV (d–f) human gastric cancer. In (a, d) endothelial cells immunoreactive for CD31; in (b, e) tryptase-positive mast cells; in (c, f) chymase-positive mast cells. Blood vessels and mast cells are distributed around the gastric glands. The number of blood vessels and mast cells is higher in stage IV as compared with stage II; bioptic specimens and chymase-positive are lower as compared with tryptase-positive mast cells. Original magnification: a–f, ×200.

These morphological aspects have been confirmed by the morphometric analysis. In fact, as indicated by the Area percentage values exhibited by the CD31-positive blood vessels (Table 1), a significant and progressive increase in vessel density was observed from stage I to stage IV. As far as mast cells were concerned, both tryptase-positive and chymase-positive cell density showed the same trend with a progressive and significant increase from stage I to stage IV (Table 1), being the density of chymase-positive cells always significantly lower than the density of tryptase-positive cells.

Table 1.

Percentage field area occupied by immunopositive structures (mean ± SEM, n = 10)

| Stage | CD31 | Tryptase | Chymase |

|---|---|---|---|

| I | 4.1 ± 1.0a | 1.9 ± 0.5a | 0.14 ± 0.03a |

| II | 6.9 ± 1.5b | 3.0 ± 0.8a | 0.23 ± 0.07a |

| III | 11.7 ± 2.2c | 4.6 ± 1.1b | 0.60 ± 0.10b |

| IV | 13.8 ± 2.8c | 5.2 ± 1.5b | 0.80 ± 0.30b |

a,b,c: means labelled with a different letter are statistically different (P < 0.05, One-way anova followed by Bonferroni’s test for multiple comparisons).

In the first stages of the pathology, both vessels and tryptase-positive mast cells appeared spatially associated with gastric glands, as demonstrated by the quite short mean distance between these structures and the gland profiles (Table 2). Such a parameter significantly increased in the next stages (Table 2), reflecting the progressive filling of the connective tissue between glands with vessels and tryptase-positive mast cells. On the contrary, in all the analysed samples, chymase-positive mast cells resulted similarly scattered in the connective tissue and their mean distance from glands did not change with stage.

Table 2.

Mean distance (microns) between immunopositive structures and glands (mean ± SEM, n = 10)

| Stage | CD31 | Tryptase | Chymase |

|---|---|---|---|

| I | 7.0 ± 1.4a | 6.0 ± 0.3a | 18.8 ± 5.1a |

| II | 7.1 ± 2.2a | 5.4 ± 0.2a | 18.2 ± 6.1a |

| III | 9.6 ± 2.2b | 8.0 ± 1.5b | 19.2 ± 5.8a |

| IV | 10.6 ± 1.1b | 10.5 ± 2.5c | 20.7 ± 5.1a |

a,b,c: means labelled with a different letter are statistically different (P < 0.05, One-way anova followed by Bonferroni’s test for multiple comparisons).

Discussion

The results of this study show that stage IV gastric carcinoma has a higher degree of vascularization than other stages and that mast cell density increases in parallel with malignancy grade and is highly correlated with the extent of angiogenesis. Moreover, the density of chymase-positive mast cells was significantly lower as compared with the density of tryptase-positive mast cells in all the examined gastric cancer bioptic specimens.

The crucial role played by inflammatory cells and among these by mast cells in regulating tumour progression and angiogenesis is well known (Ribatti & Crivellato 2009a,b;). Mast cells have been associated either with resistance or with a greater susceptibility to tumours. Indeed, mast cells accumulate in the stroma surrounding tumours and take part in the inflammatory reaction occurring at the margin of the neoplasia (Ribatti & Crivellato 2009b). Mast cells can participate in tumour rejection by producing molecules like interleukin 1 (IL-1), IL-4, IL-6 and tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α, that kill tumour cells. For instance, mast cell density in benign gastric ulcers was found to be much higher than in control subjects (Mukheriee et al. 2009). Furthermore, mast cell accumulation was also increased in well-differentiated gastric cancers when compared with controls, suggesting a mast cell intervention in the shift between inflammation and cancer. Remarkably, poorly differentiated gastric adenocarcinomas showed lower mast cell density than well-differentiated adenocarcinomas (Mukheriee et al. 2009).

In contrast, mast cells can facilitate tumour growth by promoting vascular supply, proteinase-mediated degradation of the tumour extracellular matrix and immunosuppression (Ribatti & Crivellato 2009b). An increased number of mast cells have indeed been reported in angiogenesis associated with vascular neoplasms, like haemangioma and haemangioblastoma (Glowacki & Mulliken 1982), as well as a number of solid and haematopoietic tumours. In general, mast cell density correlates with angiogenesis and poor tumour outcome. Association between mast cells and new vessel formation has been reported in breast cancer (Bowrey et al. 2000), colorectal cancer (Lachter et al. 1995) and uterine cervix cancer (Graham & Graham 1996).

Tryptase and chymase are involved in angiogenesis after their release from activated mast cells granules. Their proteolytic activities degrade extracellular matrix components or release matrix-associated growth factors (Taiplae et al. 1995) and they also act indirectly by activating latent matrix metalloproteinase (Gruber et al. 1989) and plasminogen activators (Stack & Johnson 1994). Blair et al. (1997) have demonstrated the angiogenic potential of tryptase in vitro and its important role in neovascularization. Tryptase added to microvascular endothelial cells cultured on Matrigel caused a pronounced increase in capillary growth and this was suppressed by specific tryptase inhibitors. Moreover, tryptase directly induced endothelial cell proliferation in a dose-dependent fashion. Tryptase-positive mast cells increase in number and vascularization increases in a linear fashion from dysplasia to invasive cancer of the uterine cervix (Benítez-Bribiesca et al. 2001; Ribatti et al. 2005). In benign lymphadenopathies and B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas, angiogenesis correlates with total and tryptase-positive mast cell counts and both increase in step with the increase with malignancy grades (Ribatti et al. 1998, 2000). In the bone marrow of patients with inactive and active multiple myeloma as well as those with monoclonal gammopathies of undetermined significance, angiogenesis highly correlates with tryptase-positive mast cells (Ribatti et al. 1999). A similar pattern of correlation between bone marrow microvessel count, total and tryptase-positive mast cell density and tumour progression has been found in patients with myelodysplastic syndrome (Ribatti et al. 2002) and B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (Ribatti et al. 2003d). In B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukaemia, the density of tryptase-positive mast cell in the bone marrow has been shown to predict the outcome of the disease (Molica et al. 2003).

An association of VEGF and mast cells with angiogenesis has been demonstrated in laryngeal carcinoma (Sawatsubashi et al. 2000) and in small lung carcinoma, where most intratumoural mast cells expressed VEG (Tomita et al. 2000). Mast cell accumulation was correlated with increased neovascularization, mast cell expression of VEGF (Tóth-Jakatics et al. 2000) and FGF-2 (Ribatti et al. 2003b), tumour aggressiveness and poor prognosis (Ribatti et al. 2003c) in human melanoma, as well as in squamous cell cancer of the oesophagus (Elpek et al. 2001). VEGF and its receptors are widely expressed in gastric carcinoma cells and VEGF stimulates VEGFR-2-positive tumour cell growth directly (Zhang et al. 2002), suggesting that VEGF plays a role in promoting tumour growth and metastasis in gastric carcinoma by participating in both paracrine and autocrine pathways.

Understanding mechanisms of gastric cancer angiogenesis provides a basis for a rational approach to the development of an antiangiogenic therapy in patients with gastric cancer. As it has been previously shown by Kanai et al. (1998), anti-VEGF antibody inhibited both primary tumour growth and metastasis in spontaneous metastatic models of gastric cancers implanted orthotopically into nude mice. The inhibition of its activity by neutralizing antibodies was effective in a gastric cancer xenograft model (Kanai et al. 1998; Gasparini et al. 2005). The combination of bevacizumab, a humanised monoclonal antibody against VEGF, at 15 mg/kg every 14 days, irinotecan and cisplatin, was active in untreated metastatic patients (Shah et al. 2006). In mice bearing TMK-1 human gastric tumours, SU6668, a small-molecule receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor, has been shown to suppress peritoneal dissemination (Tokuyama et al. 2005). In another TMK-1 xenograft model, vandetanib increased tumour apoptosis and reduced tumour cell proliferation and microvessel density (McCarty et al. 2004).

Our data suggest that mast cells may represent a possible target for therapeutic intervention and inhibition of mast cell function and may therefore prove therapeutically useful in controlling tumour growth and angiogenesis in gastric cancer.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by MIUR (PRIN 2007), Rome, and Fondazione Cassa di Risparmio di Puglia, Bari, Italy.

References

- Araya M, Terashima M, Takagane A, et al. Microvessel count predicts metastasis and prognosis in patients with gastric cancer. J. Surg. Oncol. 1997;65:232–236. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9098(199708)65:4<232::aid-jso2>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benítez-Bribiesca L, Wong A, Utrera D, Castellanos E. The role of mast cell tryptase in neoangiogenesis of premalignant and malignant lesions of the uterine cervix. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 2001;49:1061–1062. doi: 10.1177/002215540104900816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair RJ, Meng H, Marchese MJ, et al. Tryptase is a novel, potent angiogenic factor. J. Clin. Invest. 1997;99:2691–2700. doi: 10.1172/JCI119458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowrey PF, King J, Magarey C, et al. Histamine, mast cells and tumour cell proliferation in breast cancer: does preoperative cimetidine administration have an effect? Br. J. Cancer. 2000;82:167–170. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.1999.0895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elpek GO, Gelen T, Aksoy NH, et al. The prognostic relevance of angiogenesis and mast cells in squamous cell carcinoma of the oesophagus. J. Clin. Pathol. 2001;54:940–944. doi: 10.1136/jcp.54.12.940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etoh T, Inoue H, Tanaka S, Barnard GF, Kitano S, Mori M. Angiopoietin-2 is related to tumor angiogenesis in gastric carcinoma: possible in vivo regulation via induction of proteases. Cancer Res. 2001;61:2145–2153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasparini G, Longo R, Toi M, Ferrara N. Angiogenic inhibitors: a new therapeutic strategy in oncology. Nat. Clin. Pract. Oncol. 2005;2:562–577. doi: 10.1038/ncponc0342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glowacki J, Mulliken JB. Mast cells in hemangiomas and vascular malformations. Pediatrics. 1982;70:48–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham RM, Graham JB. Mast cells and cancer of the cervix. Surg. Gynecol. Obstet. 1996;123:3–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruber BL, Marchese MJ, Suzuki K, et al. Synovial procollagenase activation by human mast cell tryptase dependence upon matrix metalloproteinase 3 activation. J. Clin. Invest. 1989;84:1657–1662. doi: 10.1172/JCI114344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guidolin D, Crivellato E, Nico B, Andreis PG, Nussdorfer GG, Ribatti D. An image analysis of the spatial distribution of perivascular mast cells in human melanoma. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2006;17:981–987. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guidolin D, Zunarelli E, Genedani S, et al. Opposite patterns of age-associated changes in neurons and glial cells of the thalamus of human brain. Neurobiol. Aging. 2008;29:926–936. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2006.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanai T, Konno H, Tanaka T, et al. Anti-tumor and anti-metastatic effects of human-vascular-endothelial-growth-factor-neutralizing antibody on human colon and gastric carcinoma xenotransplanted orthotopically into nude mice. Int. J. Cancer. 1998;77:933–936. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19980911)77:6<933::aid-ijc23>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitadai Y, Haruma K, Sumii K, et al. Expression of interleukin-8 correlates with vascularity in human gastric carcinomas. Am. J. Pathol. 1998;152:93–100. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitadai Y, Takahashi Y, Haruma K, et al. Transfection of interleukin-8 increases angiogenesis and tumorigenesis of human gastric carcinoma cells in nude mice. Br. J. Cancer. 1999;81:647–653. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6690742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachter J, Stein M, Lichtig C, Eidelman S, Munichor M. Mast cells in colorectal neoplasias and premalignant disorders. Dis. Colon Rectum. 1995;38:290–293. doi: 10.1007/BF02055605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda K, Chung YS, Takatsuka S, et al. Tumor angiogenesis as a predictor of occurrence in gastric carcinoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 1995;13:477–481. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1995.13.2.477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda K, Chung YS, Ogawa Y, et al. Prognostic value of vascular endothelial growth factor expression in gastric carcinoma. Cancer. 1996;77:858–863. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19960301)77:5<858::aid-cncr8>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maehara Y, Kabashima A, Koga T, et al. Vascular invasion and potential for tumor angiogenesis and metastasis in gastric carcinoma. Surgery. 2000;128:408–416. doi: 10.1067/msy.2000.107265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarty MF, Wey J, Stoeltzing O, et al. ZD6474, a vascular endothelial growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor with additional activity against epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase, inhibits orthotopic growth and angiogenesis of gastric cancer. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2004;3:1041–1048. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molica S, Vacca A, Crivellato E, Cuneo A, Ribatti D. Tryptase-positive mast cells predict clinical outcome of patients with early B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Eur. J. Haematol. 2003;71:137–139. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0609.2003.00110.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukheriee S, Bandyopadhyay G, Dutta C, Bhattacharya A, Karmakar R, Barui G. Evaluation of endoscopic biopsy in gastric lesions with a special reference to the significance of mast cell density. Indian J. Pathol. Microbiol. 2009;52:20–24. doi: 10.4103/0377-4929.44956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribatti D, Crivellato E. Immune cells and angiogenesis. J. Cell Mol. Med. 2009a;13:2822–2833. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2009.00810.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribatti D, Crivellato E. The controversial role of mast cells in tumor growth. Int. Rev. Cell. Mol. Biol. 2009b;275:89–131. doi: 10.1016/S1937-6448(09)75004-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribatti D, Vacca A. Overview of angiogenesis during tumor growth. In: Figg WD, Folkman J, editors. Angiogenesis: An Integrative Approach from Science to Medicine. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 2008. pp. 161–168. [Google Scholar]

- Ribatti D, Nico B, Vacca A, et al. Do mast cells help to induce angiogenesis in B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas? Br. J. Cancer. 1998;77:1900–1906. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1998.316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribatti D, Vacca A, Nico B, et al. Bone marrow angiogenesis and mast cell density increase simultaneously with progression of human multiple myeloma. Br. J. Cancer. 1999;79:451–455. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6690070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribatti D, Vacca A, Marzullo A, et al. Angiogenesis and mast cell density with tryptase activity increase simultaneously with pathological progression in B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas. Int. J. Cancer. 2000;85:171–175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribatti D, Polimeno G, Vacca A, et al. Correlation of bone marrow angiogenesis and mast cells with tryptase activity in myelodysplastic syndromes. Leukemia. 2002;16:1680–1684. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribatti D, Marzullo A, Nico B, Crivellato E, Ria R, Vacca A. Erythropoietin as an angiogenic factor in gastric carcinoma. Histopathology. 2003a;42:246–250. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.2003.01581.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribatti D, Vacca A, Ria R, et al. Neovascularisation, expression of fibroblast growth factor-2, and mast cells with tryptase activity increase simultaneously with pathological progression in human malignant melanoma. Eur. J. Cancer. 2003b;39:666–674. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(02)00150-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribatti D, Ennas MG, Vacca A, et al. Tumor vascularity and tryptase-positive mast cells correlate with a poor prognosis in melanoma. Eur. J. Clin. Invest. 2003c;33:420–425. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2362.2003.01152.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribatti D, Molica S, Vacca A, et al. Tryptase-positive mast cells correlate positively with bone marrow angiogenesis in B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Leukemia. 2003d;17:1428–1430. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribatti D, Crivellato E, Roccaro AM, Ria R, Vacca A. Mast cell contribution to angiogenesis related to tumor progression. Clin. Exp. Allergy. 2004;34:1660–1664. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2004.02104.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribatti D, Finato N, Crivellato E, et al. Neovascularization and mast cells with tryptase activity increase simultaneously with pathologic progression in human endometrial cancer. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2005;193:1961–1965. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.04.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribatti D, Nico B, Vacca A. Importance of the bone marrow microenvironment in inducing the angiogenic response in multiple myeloma. Oncogene. 2006;25:4257–4266. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribatti D, Nico B, Crivellato E, Roccaro AM, Vacca A. The history of the angiogenic switch concept. Leukemia. 2007;21:44–52. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito H, Tsujitani S, Oka S, et al. The expression of transforming growth factor-α-1 is significantly correlated with the expression of vascular endothelial growth factor and prognosis of patients with advanced gastric carcinoma. Cancer. 1999;86:1455–1462. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19991015)86:8<1455::aid-cncr11>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawatsubashi M, Yamada T, Fukushima N, Mizokami H, Tokunaga O, Shin T. Association of vascular endothelial growth factor and mast cells with angiogenesis in laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Virchows Arch. 2000;436:243–248. doi: 10.1007/s004280050037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz LB. Analysis of MC(T) and MC(TC) mast cells in tissue. Methods Mol. Biol. 2006;315:53–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah MA, Ramanathan RK, Ilson DH, et al. Multicenter phase II study of irinotecan, cisplatin, and bevacizumab in patients with metastatic gastric or gastroesophageal junction adenocarcinoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2006;24:5201–5206. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.0887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stack MS, Johnson DA. Human mast cell tryptase activates single-chain urinary-type plasminogen activator (pro-urokinase) J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:9416–9419. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taiplae J, Lohi J, Saarinen J, Kovanen PT, Keshi-Oja J. Human mast cell chymase and leukocyte elestase release latent transforming growth factor beta-1 from the extracellular matrix of cultured human epithelial and endothelial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:4689–4696. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.9.4689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi Y, Cleary KR, Mai M, Kitadai Y, Bucana CD, Ellis LM. Significance of vessel count and vascular endothelial growth factor and its receptor (KDR) in intestinal-type gastric cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 1996;2:1679–1684. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi Y, Bucana CD, Akagi Y, et al. Significance of platelet-derived endothelial cell growth factor in the angiogenesis of human gastric cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 1998;4:429–434. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanigawa N, Amaya H, Matsumura M, et al. Extent of tumor vascularization correlates with prognosis and hematogeneous metastasis in gastric carcinomas. Cancer Res. 1996;56:2671–2676. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanigawa N, Amaya H, Matsumura M, Shimomatsuya T. Correlation between expression of vascular endothelial growth factor and tumor vascularity, and patient outcome in human gastric cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 1997a;15:826–832. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.2.826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanigawa N, Amaya H, Matsumura M, Shimomatsuya T. Association of tumour vasculature with tumour progression and overall survival of patients with non-early gastric carcinomas. Br. J. Cancer. 1997b;75:566–571. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1997.99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tokuyama J, Kubota T, Saikawa Y, et al. Tyrosine kinase inhibitor SU6668 inhibits peritoneal dissemination of gastric cancer via suppression of tumor angiogenesis. Anticancer Res. 2005;25:17–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomita M, Matsuzaki Y, Onitsuka T. Effect of mast cells on tumor angiogenesis in lung cancer. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2000;69:1686–1690. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(00)01160-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tóth-Jakatics R, Jimi S, Takebayashi S, Kawamoto N. Cutaneous malignant melanoma: correlation between neovascularization and peritumor accumulation of mast cells overexpressing vascular endothelial growth factor. Hum. Pathol. 2000;31:955–960. doi: 10.1053/hupa.2000.16658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Wu J, Meng L, Shou CC. Expression of vascular endothelial growth factor and its receptors KDR and Flt-1 in gastric cancer cells. World J. Gastroenterol. 2002;8:994–998. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v8.i6.994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]