Summary

Treponema denticola levels in the gingival crevice become elevated as periodontal disease develops. Oral treponemes may account for as much as 40% of the total bacterial population in the periodontal pocket. The stimuli that trigger enhanced growth of T. denticola and the mechanisms associated with the transmission of these signals, remain to be defined. We hypothesize that the T. denticola ORFs tde1970 (histidine kinase) and tde1969 (response regulator) constitute a functional two component regulatory system that regulates, at least in part, responses to the changing environmental conditions associated with the development of periodontal disease. The results presented demonstrate that tde1970 and tde1969 are conserved, universal among T. denticola isolates and transcribed as part of a 7 gene operon in a growth phase dependent manner. Tde1970 undergoes autophosphorylation and transfers phosphate to tde1969. Henceforth the proteins encoded by these ORFs are designated as Hpk2 and Rrp2 respectively. Hpk2 autophosphorylation kinetics were influenced by environmental conditions and by the presence or absence of a PAS domain. It can be concluded that Hpk2 and Rrp2 constitute a functional two-component system that contributes to environmental sensing.

Introduction

Periodontal disease reflects an imbalance in a normally well-balanced population of bacteria in the sub-gingival crevice (Handfield et al., 2008; Loesche and Grossman, 2001). Oral treponemes, and in particular Treponema denticola, are important contributors to periodontal disease (Ellen and Galimanas, 2005). T. denticola is a member of the red microbial complex which consists of T. denticola, Porphyromonas gingivalis and Tannerella forsythia (Haffajee and Socransky, 2005; Socransky and Haffajee, 2005). The red complex is tightly associated with advanced chronic periodontitis. In healthy individuals, T. denticola is present in the sub-gingival crevice at low numbers (<1% of the total bacteria). However as disease develops, T. denticola and other oral spirochetes thrive and ultimately represent as much as 40% of the total bacterial population in the periodontal pocket (Ellen and Galimanas, 2005; Loesche, 1988).

Significant advances have been made in recent years in understanding the complex mechanisms of communication that occur between organisms in oral biofilms (Handfield et al., 2008; Kolenbrander et al., 2002; Kolenbrander et al., 2006; Simionato et al., 2006). However, the communication strategies and global regulatory mechanisms of spirochetes associated with periodontal disease have been largely unexplored. In bacteria, two-component regulatory systems are key players in adaptive responses and global transcriptional regulation (Galperin, 2004). Two-component systems typically consist of a histidine kinase and a response regulator. There is considerable variation in domain architecture among histidine kinases and response regulators (Galperin, 2004, 2006). The effector mechanisms of response regulators also vary. The general paradigm for two-component systems is that external stimuli regulate the opposing autophosphorylation-phosphatase activities of the histidine kinase. Phosphorylation of the kinase activates it allowing for the transfer of phosphate to a conserved aspartate residue in the receiver domain of the response regulator. This induces a conformational change in the output domain that activates the protein (Koretke et al., 2000). The response regulator can then regulate transcription by binding to DNA. Some response regulators can also influence cellular activities through protein-protein interactions, c-di-GMP production and or through the regulation of enzymatic activities (Cotter and Stibitz, 2007; Galperin et al., 2001; Galperin, 2006; Rogers et al., 2009; Smith et al., 2009; Stock et al., 2000; Stock, 2007). To date the only two-component system of an oral spirochete that has been demonstrated to be functional is the growth phase regulated T. denticola AtcR (response regulator) and AtcS (histidine kinase) system (Frederick et al., 2008). AtcR is the only spirochetal response regulator identified to date that harbors a LytTR domain. This observation suggests that AtcR may play a unique role in T. denticola gene regulation (Frederick et al., 2008).

In this report we initiate studies to test the hypothesis that the T. denticola ORFs tde1970 (histidine kinase) and tde1969 (response regulator) constitute a functional two-component system that is responsive to environmental conditions. tde1970 and tde1969 are homologs of Hpk2 and Rrp2, respectively, which form a two-component system in Borrelia burgdorferi that is responsive to environmental stimuli (Blevins et al., 2009; Boardman et al., 2008; Ouyang et al., 2008; Yang et al., 2003). Importantly, T. denticola Hpk2 harbors a potential oxygen sensing, PAS-heme binding domain (Moglich et al., 2009). Oxygen concentrations in the sub-gingival crevice undergo significant change as periodontal disease progresses. Hpk2 and Rrp2 could prove to be critical regulators of responses to the changing environment associated with disease progression. The results presented within support the hypothesis that Hpk2-Rrp2 is a functional two-component systems that functions in environmental sensing.

Methods

Bacterial strains and culture conditions

T. denticola strains 35405, N17A1, GM1, 33521 and MS25 were cultivated in NOS media in an anaerobic chamber(5% H2, 20% CO2, 75% N2; 37° C). Growth was monitored by dark field microscopy using a microscope contained within the anaerobic chamber. All strains were obtained from ATCC or kindly provided by Dr. Peter Greenberg (Univ. Washington).

Ligation independent cloning (LIC) and generation of recombinant proteins

LIC techniques were used to generate recombinant proteins as previously described (Frederick et al., 2008). Gene sequences (or portions thereof) were PCR amplified using 2X Phusion high fidelity taq (Finnzymes) and annealed with the pET46Ek-LIC vector (Novagen). All oligonucleotide primers used in this report are described in Table 1. The recombinant plasmids were propagated in Escherichia coli NOVABlue cells, transformed into E. coli BL21 (DE3) cells and protein production induced with 1mM IPTG (3 hr; 37ºC). Recombinant proteins were purified using nickel chromatography as instructed by the supplier of the resin (Novagen).

Table 1.

Oligonucleotide primers used in this studya

| Rrp2-F | GACGACGACAAGATTATGAAATTCAGTATTTTGGTTATTGATGACGAAAAAAATATTCG |

| Rrp2 R | GAGGAGAAGCCCGGTTTATTTTTTGCCATTTACTTTTTCCTTTTTGGATTGATTTTC |

| Hpk2-F | GACGACGACAAGATTATGAGAGAGTTTATGAGAAGGGGAATACAAAAATCC |

| Hpk2-R | GAGGAGAAGCCCGGTTCATTTTATATCCTTTACCGAATCAAAATCGAAAGTTTTATCGG |

| 1968-69F | CGAAAACTTGATGAATATGATGCGGAG |

| 1968-69R | AAGTTTGTATACGGAACGAGCAGG |

| 1969-70F | GGCAGGGTATCTTACCCGAGGATATGCATAAAATATTTGAG |

| 1969-70R | CCCATCCTCATGGCTTCAACAGCCGTTTCTACCGTCC |

| 1970-71F | AATGAAGAATGTTCCGCTTTGGAAG |

| 1970-71R | GGATTTTTGTATTCCCCTTCTCATAAAC |

| 1971-72F | GTACATACGGTACAAAACATCGC |

| 1971-72R | GGCCCCGAAAACAAAATCG |

| 1972-73F | TTATCAATATCCAAACCTTTGTTTCATTCG |

| 1972-73R | GCCGAACTGTTTATCATACCC |

| 1973-74F | CAGGTGAAAAACCTGCCCTCG |

| 1973-74R | CTCGTCTATAAAACCGGTTACGGTAACC |

| 1974-75F | GCCTCGGATATTCTCAGGTGGAATG |

| 1974-75R | AGGCCTCGGCAACGGCAAG |

| ΔPAS-F | GACGACGACAAGATTATGAAAGCCGATAAGCCTGAAGGTAAAAATAAATATATTGAAGTTTCGG |

Ligase independent cloning tail sequences are indicated by underlining.

DNA sequence analysis

hpk2 and rrp2 were amplified from several T. denticola strains and annealed into the pET46Ek-LIC expression vector as described above. Insert sequences, determined on a fee-for service basis (MWG Biotech), were translated (Expert Protein Analysis System proteomics server), aligned (BioEdit sequence alignment editor 7.0.9.0) and percent similarity/identity values calculated (Matrix Global Alignment Tool).

Generation of antiserum and immunoblotting techniques

Antisera to Hpk2 and Rrp2 (derived from T. denticola 35405) was generated in C3H/HeJ mice using 25 μg of recombinant protein (Imject Alum adjuvant; Pierce). Boosts were administered at 2, 4 and 6 weeks. The mice were euthanized (week 7), blood was harvested and serum was prepared. To prepare cell lysates for SDS-PAGE, 0.1 O.D600 of T.denticola was suspended in SDS sample buffer (150μl) and boiled. The lysates (3 μl) were fractioned by SDS-PAGE (12.5% Criterion Precast SDS-PAGE gels; 200 V; 1 hr), transferred to PVDF membranes by electroblotting and screened with specific antiserum (1:1000 in blocking buffer; 1% PBS, 0.2% Tween 20, 5% Carnation Nonfat dry milk). Blots of recombinant proteins were screened with anti-His antibody (1:10,000 dilution). Bound antibody was detected with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (IgG) (Pierce; 1:40,000 dilution) using chemiluminescence.

Real-time RT-PCR

Cells were cultivated for either 4 or 13 days and RNA was extracted using the RNEasy Extraction Kit (Qiagen). RT-PCR and real-time RT-PCR analyses were conducted as previously described (Zhang et al., 2005). To generate standard curves, amplicons of each gene were cloned into the pCR2.1 TOPO vector (Invitrogen) and serial dilutions of the purified plasmid were used as the PCR template. flaA transcript levels, a constitutively expressed gene, served as the standardization-normalization control for real time RT-PCR analyses.

Autophosphorylation and phosphotransfer assays

Autophosphorylation of Hpk2 was assessed using recombinant protein (20 ng μl−1) under aerobic (room atmosphere) or anaerobic (5% CO2, 10% H2, and 85% N2) conditions in kinase buffer (50 μl volume, 30mM HEPES, pH 8.0, 50mM KCl, 10mM MgCl2, 0.5mM EDTA, 2mM DTT, 40 nM γ-32P ATP, 6000 Ci mmol−1, at room temperature). For anaerobic assays, all reagents were equilibrated in an anaerobic chamber for 3 days. Aliquots from each reaction (0, 5, 10, 30 min) were mixed with 2X SDS sample buffer, fractionated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to PVDF membranes. The membranes were exposed to film at −80 °C for 4 hr with intensifying screens. To quantitate autophosphorylation, the reactions were repeated as above, fractionated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to PDVF membranes, and stained with Coomassie. The bands corresponding to Hpk2 were excised, transferred to glass vials and the amount of incorporated phosphate determined using liquid scintillation counting.

Phosphotransfer was assessed by incubating radiolabeled-phosphorylated recombinant Hpk2 (generated as described above) with recombinant Rrp2 (20 ng μl−1) in kinase buffer under aerobic or anaerobic conditions. Aliquots from the reaction mixture (0, 5, 10, and 30 min) were mixed with 2X SDS sample buffer, fractionated by SDS-PAGE, electroblotted and exposed to film as above.

Results

Properties, sequence conservation and distribution of tde1970 (Hpk2) and tde1969 (Rrp2) among T. denticola isolates

tde1970 (46 kDa) and tde1969 (53 kDa) are functionally annotated as a sensor kinase and response regulator, respectively (Seshadri et al., 2004). Due to their homology with Hpk2 (Histidine protein kinase 2) and Rrp2 (Response regulator protein 2) of Borrelia burgdorferi (Yang et al., 2003), we designate tde1970 and tde1969 as Hpk2 and Rrp2, respectively.

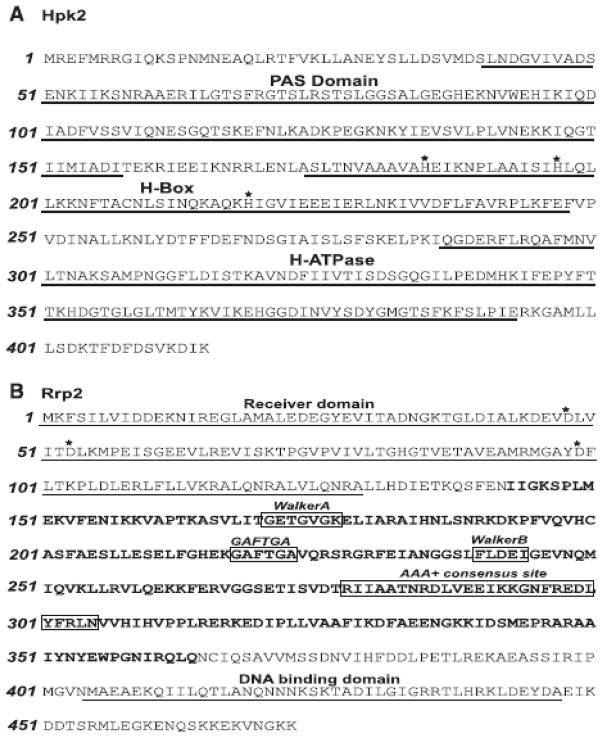

The domain architecture of Hpk2 and Rrp2 is depicted in Fig. 1. Hpk2 harbors an N-terminal PAS domain with a putative heme binding pocket. The association of heme binding-PAS domains with oxygen sensing suggest that Hpk2 could play an important role in responding to changing oxygen concentration in the subgingival crevice as disease progresses (Galperin, 2004; Taylor and Zhulin, 1999). The PAS domain is followed by an H-Box domain (with 3 putative His autophosphorylation sites at H185, H197 and H219) and an H-ATPase domain (ATP-Mg2+ binding sites). PCR and subsequent DNA sequence analyses of hpk2 from a panel of T. denticola isolates revealed that the gene is highly conserved with amino acid identity values greater than 96% (Table 2). All of the major functional domains and putative functionally important residues of Hpk2 are conserved (Fig. 1A). It is noteworthy that T. denticola hpk2 sequences harbor a unique insertion within the PAS domain of 45 nt/15 aa (indicated in Fig. 1A). This insertion is not found in other annotated PAS-domain containing proteins including those of other spirochetes.

Fig. 1. Sequence and functional domains of Hpk2 and Rrp2.

Amino acid sequences are shown for the Hpk2 (panel A) and Rrp2 (panel B) proteins of T. denticola strain 35405. Predicted functional domains for both proteins are indicated. The bolded amino acids of Rrp2 indicate the σ54- interaction domain. Additional functional domains that reside within the σ54- interaction domain are highlighted by boxing. Residues that may undergo autophosphorylation in Hpk2 or serve as phosphoacceptor residues in Rrp2 are indicated by asterisks.

Table 2.

Percentage amino acid identity and similarity values for Treponema denticola Hpk2 orthologs

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Tde(35405) | 96.6 | 98.8 | 98.6 | 98.8 | 55.9 | 45.5 | 32.7 | 19.5 | 19.3 | 32 | 31.5 | 32 | 31.7 | 21.6 | 20.2 | |

| (2) Tde(N17A1) | 97.8 | 95.9 | 95.7 | 95.9 | 57 | 46.3 | 33.1 | 17.7 | 19.2 | 33.2 | 32.1 | 32.9 | 32.6 | 22.6 | 18.8 | |

| (3) Tde(GM1) | 99.5 | 97.3 | 99.3 | 100 | 56.3 | 45.3 | 32.7 | 18.4 | 18.5 | 32 | 31.5 | 32 | 31.7 | 21.6 | 20.1 | |

| (4) Tde(35521) | 99.5 | 97.3 | 99.5 | 99.3 | 56.6 | 45.5 | 32.9 | 17.4 | 18.1 | 32.2 | 31.7 | 31.7 | 31.5 | 21.8 | 20.4 | |

| (5) Tde(MS25) | 99.5 | 97.3 | 100 | 99.5 | 56.3 | 45.3 | 32.7 | 18.4 | 18.5 | 32 | 31.5 | 32 | 31.7 | 21.6 | 20.1 | |

| (6) TREVI0001_1211 | 74.7 | 75.6 | 74.9 | 74.9 | 74.9 | 49.5 | 34.1 | 18 | 19.1 | 34.7 | 34.7 | 34.1 | 33.8 | 23.4 | 18.4 | |

| (7) Tp0520 | 65.5 | 66.6 | 65.5 | 65.5 | 65.5 | 67.3 | 33.3 | 16.5 | 16.8 | 33.6 | 31.9 | 32.3 | 32.6 | 25.9 | 18.2 | |

| (8) Bb0764 | 55.7 | 56.1 | 55.7 | 55.7 | 55.7 | 57.9 | 58.9 | 18.5 | 18.6 | 74.1 | 73.8 | 72.8 | 73.1 | 23.9 | 18.4 | |

| (9) BG0787 | 33.3 | 35.6 | 34.9 | 34.2 | 34.9 | 37.4 | 33 | 38 | 90.9 | 18.2 | 19.2 | 19.4 | 18.6 | 17.3 | 15.5 | |

| (10) BA(PKo)0811/2 | 36.4 | 35.9 | 35.4 | 34.7 | 35.4 | 35.1 | 32 | 39.5 | 97 | 20.2 | 16.8 | 19.2 | 19.5 | 14.7 | 16.4 | |

| (11) BT0764 | 55.4 | 56.6 | 55.4 | 55.4 | 55.4 | 59.2 | 57.6 | 84.7 | 38.9 | 38.6 | 94.3 | 90.9 | 90.9 | 23.3 | 20.9 | |

| (12) BH0764 | 54.9 | 55.6 | 54.9 | 54.9 | 54.9 | 59.2 | 56.9 | 85.5 | 38.1 | 37.6 | 96.9 | 92.5 | 92.5 | 26.1 | 20.8 | |

| (13) BDU768 | 55.2 | 55.9 | 55.2 | 55.2 | 55.2 | 57.9 | 57.4 | 85.5 | 37.8 | 37.8 | 95.9 | 97.4 | 99.5 | 24.3 | 21.7 | |

| (14) BRE771 | 54.9 | 55.6 | 54.9 | 54.9 | 54.9 | 58.2 | 57.6 | 85.5 | 36.3 | 37.8 | 95.6 | 97.2 | 99.7 | 24.6 | 21.7 | |

| (15) LA2401 | 45.5 | 46.6 | 45.5 | 45.5 | 45.5 | 44.3 | 47.5 | 47.4 | 32.9 | 38.5 | 48.2 | 50.5 | 49 | 49.2 | 19 | |

| (16) LBL1667 | 36.4 | 35.7 | 36.4 | 36.6 | 36.4 | 34.1 | 33.4 | 37.8 | 27.2 | 29.5 | 36.2 | 35.7 | 35.4 | 35.4 | 34.2 |

Identity and similarity values are presented in the upper right and lower left quadrants respectively. The T. denticola (Td with isolate designations in parentheses) sequences were determined as part of this report. All other sequences were obtained from the databases. The open reading frame designations/numbers are provided.

T. vincentii, TREV; T. pallidum, Tp; Borrelia burgdorferi, BB; B. garinii, BG; B. afzelii, BA; B. turicatae, BT; B. hermsii, BH; B. duttonii, BDU; B. recurrentis, BRE; Leptospira interrogans, LA; L. borgpetersenii, LBL.

Rrp2 harbors a receiver-phosphorylation domain (with 3 highly conserved Asp residues at positions 48, 53 and 99), σ54 interaction domain, “AAA” ATPase domain and a helix-turn-helix DNA-binding domain (Fig. 1B). The putative functional domains of Rrp2 share significant sequence similarity with domains present in response regulators of the NtrC-fis family (σ54-RNA polymerase transcriptional activators). These activators function with σ54-RNA polymerase holoenzyme and stimulate isomerization of the closed promoter complex to an open complex in a reaction that requires ATP hydrolysis (Beck et al., 2007). Sequence analysis of rrp2 from a panel of T. denticola isolates revealed amino acid identity values greater than 98%, respectively (Table 3).

Table 3.

Percentage amino acid identity and similarity values for Treponema denticola Rrp2 orthologs

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Td(35405) | 96.6 | 98.8 | 98.6 | 98.8 | 55.9 | 45.5 | 32.7 | 19.5 | 19.3 | 32 | 31.5 | 32 | 31.7 | 21.6 | 20.2 | |

| (2) Td(N17A1) | 97.8 | 95.9 | 95.7 | 95.9 | 57 | 46.3 | 33.1 | 17.7 | 19.2 | 33.2 | 32.1 | 32.9 | 32.6 | 22.6 | 18.8 | |

| (3) Td(GM1) | 99.5 | 97.3 | 99.3 | 100 | 56.3 | 45.3 | 32.7 | 18.4 | 18.5 | 32 | 31.5 | 32 | 31.7 | 21.6 | 20.1 | |

| (4) Td(35521) | 99.5 | 97.3 | 99.5 | 99.3 | 56.6 | 45.5 | 32.9 | 17.4 | 18.1 | 32.2 | 31.7 | 31.7 | 31.5 | 21.8 | 20.4 | |

| (5) Td(MS25) | 99.5 | 97.3 | 100 | 99.5 | 56.3 | 45.3 | 32.7 | 18.4 | 18.5 | 32 | 31.5 | 32 | 31.7 | 21.6 | 20.1 | |

| (6) TREVI0001_1210 | 74.7 | 75.6 | 74.9 | 74.9 | 74.9 | 49.5 | 34.1 | 18 | 19.1 | 34.7 | 34.7 | 34.1 | 33.8 | 23.4 | 18.4 | |

| (7) Tp0519 | 65.5 | 66.6 | 65.5 | 65.5 | 65.5 | 67.3 | 33.3 | 16.5 | 16.8 | 33.6 | 31.9 | 32.3 | 32.6 | 25.9 | 18.2 | |

| (8) Bb0763 | 55.7 | 56.1 | 55.7 | 55.7 | 55.7 | 57.9 | 58.9 | 18.5 | 18.6 | 74.1 | 73.8 | 72.8 | 73.1 | 23.9 | 18.4 | |

| (9) Bg0786 | 33.3 | 35.6 | 34.9 | 34.2 | 34.9 | 37.4 | 33 | 38 | 90.9 | 18.2 | 19.2 | 19.4 | 18.6 | 17.3 | 15.5 | |

| (10) BA(PKo)0810 | 36.4 | 35.9 | 35.4 | 34.7 | 35.4 | 35.1 | 32 | 39.5 | 97 | 20.2 | 16.8 | 19.2 | 19.5 | 14.7 | 16.4 | |

| (11) BT0763 | 55.4 | 56.6 | 55.4 | 55.4 | 55.4 | 59.2 | 57.6 | 84.7 | 38.9 | 38.6 | 94.3 | 90.9 | 90.9 | 23.3 | 20.9 | |

| (12) BH0763 | 54.9 | 55.6 | 54.9 | 54.9 | 54.9 | 59.2 | 56.9 | 85.5 | 38.1 | 37.6 | 96.9 | 92.5 | 92.5 | 26.1 | 20.8 | |

| (13) BDU767 | 55.2 | 55.9 | 55.2 | 55.2 | 55.2 | 57.9 | 57.4 | 85.5 | 37.8 | 37.8 | 95.9 | 97.4 | 99.5 | 24.3 | 21.7 | |

| (14) BRE770 | 54.9 | 55.6 | 54.9 | 54.9 | 54.9 | 58.2 | 57.6 | 85.5 | 36.3 | 37.8 | 95.6 | 97.2 | 99.7 | 24.6 | 21.7 | |

| (15) LA2401 | 45.5 | 46.6 | 45.5 | 45.5 | 45.5 | 44.3 | 47.5 | 47.4 | 32.9 | 38.5 | 48.2 | 50.5 | 49 | 49.2 | 19 | |

| (16) LBL1666 | 36.4 | 35.7 | 36.4 | 36.6 | 36.4 | 34.1 | 33.4 | 37.8 | 27.2 | 29.5 | 36.2 | 35.7 | 35.4 | 35.4 | 34.2 |

Identity and similarity values are presented in the upper right and lower left quadrants respectively. The T. denticola (Td with isolate designations in parentheses) sequences were determined as part of this report. All other sequences were obtained from the databases. The open reading frame designations/numbers are provided.

T. vincentii, TREV; T. pallidum, Tp; Borrelia burgdorferi, BB; B. garinii, BG; B. afzelii, BA; B. turicatae, BT; B. hermsii, BH; B. duttonii, BDU; B. recurrentis, BRE; Leptospira interrogans, LA; L. borgpetersenii, LBL.

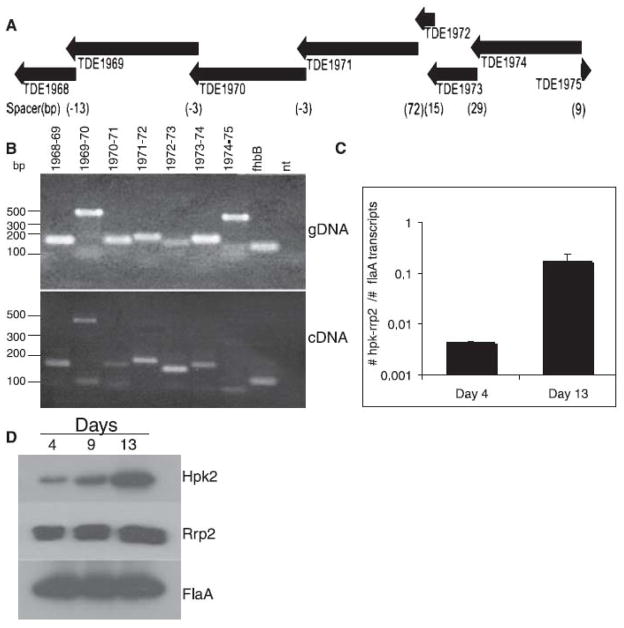

In the T. denticola isolate 35405, hpk2 and rrp2 are surrounded by ORFs that overlap or have short intergenic spacers (Fig. 2A). This arrangement suggests that these genes may be transcribed as a polycistronic mRNA that initiates with tde1974 and extends through tde1968. The proteins encoded by these ORFs are described in Table 4. PCR analyses of other T. denticola isolates revealed that the tde1968-tde1974 gene cluster is present and similarly oriented (data not shown). In other Treponemes and Borrelia species a analogous tde1974-tde1969 gene cluster is present but it lacks tde1972 and tde1968. Tde1968 is present in the genome of these spirochetes but it is distally located from hpk2-rrp2.

Fig. 2. Schematic of the T. denticola 35405 hpk2-rrp2 locus: demonstration of co-transcription and growth phase regulated expression.

The organization of hpk2, rrp2 and adjacent genes are shown in panel A (ORF designations and the direction of transcription are indicated). Intergenic spacer lengths (in base pairs) are listed below the schematic in parentheses with negative numbers indicating coding sequence overlap. RT-PCR analyses, using primers that amplify across the intergenic spacer region, are presented in panel B (cDNA panel). To verify that the primers were functional, each was tested with genomic DNA (gDNA) as template. Detection of the constitutively expressed fhbB (Factor H binding protein B) (McDowell et al., 2007) gene served as a positive control for RT-PCR. Nt indicates that no template was added (negative control). The size standards (in base pairs) are indicated to the left. The results of hpk2-rrp2 qRT-PCR analyses are presented in panel C. Transcript levels were determined using RNA recovered from cultures grown for 4 or 13 days (as indicated). The data were normalized using the levels of the constitutively and highly transcribed flaA gene. Panel D presents immunoblot analyses in which the relative production of Hpk2, Rrp2 and FlaA (a constitutive control) were measured in cells cultivated for 4, 9 or 13 days. All methods are described in the text.

Table 4.

Description of genes/proteins investigated in this study

| orf | Gene | paralogs | Function and notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| tde1968 | ftsJ (rrmJ) | none | 23S rRNA methyltransferase; 2′-O methylates residue U2552 of the A loop of 23S rRNA; methylation stabilizes the 50S subunit within the 70S ribosome (Hager et al., 2002); inactivation of this gene in B. burgdorferi impaired growth rate and morphology (Morozova et al., 2005) |

| tde1969 | rrp2 | 2079, 2309, 2593, 0492, 1494, 2324, 2501, 2502, 0033, 0648, 0655, 0149, 0855 | σ54 dependent transcriptional regulator/response regulatory protein; In B. burgdorferi (Bb) an Rrp2 is required for survival as deletion of rrp2 appears to be lethal (Yang et al., 2003); In Bb Rrp2 directly or indirectly controls a regulon consisting primarily of plasmid carried genes involved in virulence (Blevins et al., 2009; Burtnick et al., 2007; Caimano et al., 2007; Lybecker and Samuels, 2007); |

| tde1970 | hpk2 | 2502, 0492, 0656 | histidine kinase, possibly involved in oxygen sensing; In Bb, it is presumed to be the cognate kinase for Rrp2 however this has not been directly demonstrated |

| tde1971 | dnaX | 2586 | gamma/tau subunit of DNA polymerase III, DNA replication |

| tde1972 | HP | 2397, 1131, 2094, 0692, 2223, 1235, 1005 | 40 aa peptide with a possible toxin BmKK4 domain (a member of the sub-family α-KTx17) (Zhang et al., 2004a; Zhang et al., 2004b); |

| tde1973 | cvpA | none | colicin V (anti-bacterial) production factor |

| tde1974 | murG | none | a glycosyltransferase that catalyzes the last intracellular step of peptidogylcan synthesis; it is required for cell growth and survival; interacts via hydrophobic interactions with the inner membrane; may be part of the divisome (Mohammadi et al., 2007) |

Transcriptional analysis of hpk2 and rrp2

To determine if hpk2-rrp2 and flanking genes are co-transcribed, RT-PCR analyses were conducted using gene spanning primers. RT-PCR analyses identified a transcriptional unit consisting of ORFs tde1968 through tde1974 (Fig. 2B). As a negative control, RT-PCR was performed using a primer set spanning ORFs tde1975 and tde1974. A product was not obtained consistent with the opposite orientation of tde1975. RT-PCR of fhbB, a constitutively expressed membrane protein that binds to the complement regulatory protein factor H (McDowell et al., 2009), served as a positive control for RT-PCR. Finally all primers were tested using genomic DNA as template to verify that all primers were functional. Henceforth we refer to this 7 gene operon as the hpk2-rrp2 operon.

Demonstration of growth phase-dependent expression of hpk2 and rrp2

To determine if transcription of the hpk2-rrp2 operon is influenced by growth stage, real-time RT-PCR was performed using RNA extracted from cells harvested after 4 and 13 days of cultivation. Relative to day 4, a 100-fold induction in hpk2-rrp2 transcript levels was observed at day 13 (Fig. 2C). The data were normalized against the numbers of flaA transcript detected and are presented as the ratio of the number of hpk2-rrp2 transcripts to the number of flaA transcripts. Immunoblot analyses of T. denticola cell lysates obtained from cultures harvested at 4, 9 and 13 days confirmed increased production of Hpk2 and Rrp2 with growth phase (Fig. 2D). The levels of FlaA protein, a constitutively produced protein, remained unchanged.

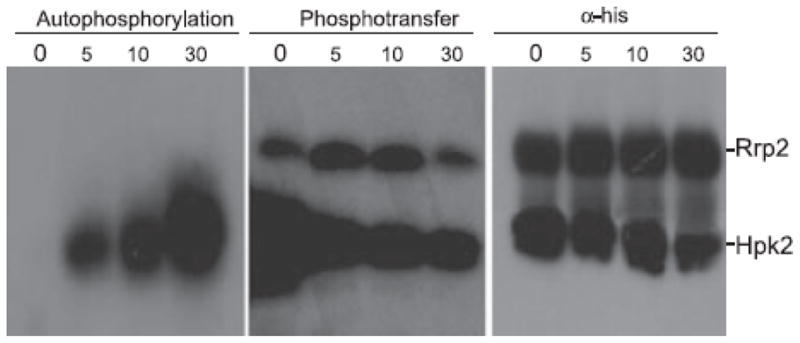

Autophosphorylation and phosphotransfer capabilities of Hpk2 and Rrp2

Using γ-32P ATP as a phosphate source, Hpk2 was demonstrated to autophosphorylate in a time-dependent manner (Fig. 3; left panel). As a control for the specificity of autophosphorylation, Rrp2, which is not expected to autophosphorylate, was incubated alone with γ-32P ATP. No labeling was observed (data not shown). Phosphorylated Hpk2 was then demonstrated to transfer phosphate to Rrp2 (Fig. 3). A plateau or equilibrium in Rrp2 phosphorylation was reached by 5 min. This rapid transfer and plateau is consistent with use of a 1:1 ratio of Hpk2 to Rrp2 in the reaction. Note that the 1:1 ratio of Hpk2 to Rrp2 was verified by immunoblotting using anti-His antiserum (Fig. 3; right panel). We noted that phosphotransfer requires preloading of Hpk2 with phosphate. When non-phosphorylated Hpk2 and Rrp2 were combined prior to the addition of γ-32P ATP, phosphotransfer did not occur.

Fig. 3. Demonstration of Hpk2 autophosphorylation and phosphotransfer to Rrp2.

Autophosphorylation of Hpk2 (left panel) and phosphotransfer to Rrp2 (middle panel) was assessed over time (as indicated above each lane in minutes) using recombinant proteins and protocols detailed in the text. To verify that equal molar amounts of Hpk2 and Rrp2 were used in the assay, an identical blot was screened with anti-his antibody (right panel). Note that for the phosphotransfer analyses, Hpk2` was preloaded with phosphate prior to mixing with Rrp2 and then aliquots were removed at the timepoints indicated. The migration position of each protein is indicated to the right.

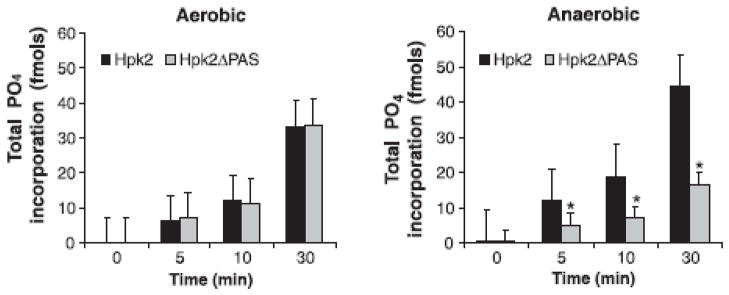

The Hpk2 PAS domain senses in-vitro environmental conditions and influences the kinetics of autophosphorylation and phosphotransfer

To assess the contribution of the PAS domain in Hpk2 autophosphorylation and phosphotransfer, full length Hpk2 and an N-terminal 122 aa truncation variant (Hpk2ΔPAS) were generated. The N-terminal truncation removes the PAS domain but leaves other functional domains of the protein intact. Autophosphorylation reactions were set up as detailed above except the reactions were conducted under aerobic and anaerobic conditions. Autophosphorylation was quantified by measuring the incorporation of 32P into Hpk2 and Hpk2ΔPAS. Under aerobic conditions no significant difference in phosphate incorporation was observed between Hpk2 and Hpk2ΔPAS (p>0.05) (Fig. 4). However, under anaerobic conditions significant differences were observed. Hpk2ΔPAS displayed a reduction in phosphate incorporation relative to the full length form of Hpk2 (p<0.05) (Fig. 4; right panel). While Hpk2ΔPAS retained its autophosphorylation activity (albeit at a reduced level under anaerobic conditions), it was not competent to transfer phosphate to Rrp2 (data not shown).

Fig. 4. Measurement of Hpk2 autophosphorylation: analysis of the contribution of the PAS domain and the influence of environmental conditions.

Autophosphorylation of recombinant Hpk2 and Hpk2ΔPAS under aerobic and anaerobic conditions (as indicated above each panel) was assessed as detailed in the text with incorporation of 32P serving as the read out. All assays were conducted in triplicate and the variance determined. Asterisks (*) indicate statistically significant differences between Hpk2 and Hpk2ΔPAS.

Discussion

The 70 or more Treponemal species that reside in the oral cavity (Paster et al., 2001; Paster et al., 2006) represent a low percentrage of the total bacterial mass of the sub-gingival crevice in healthy individuals. However, spirochetes become dominant in the periodontal pocket as disease progresses (Ellen and Galimanas, 2005; Loesche, 1988). The molecular basis of the adaptive responses associated with successful outgrowth of spirochetes during periodontal disease have not been delineated. The T. denticola genome encodes several two-component systems, orphan kinases and orphan response regulators (Frederick et al., 2008; Seshadri et al., 2004) that are likely to be key mediators of adaptive responses. However to date, only the AtcRS system of T. denticola has been analyzed and demonstrated to be functional in terms of autophosphorylation and phosphotransfer (Frederick et al., 2008). It is our hypothesis that the T. denticola Hpk2 and Rrp2 proteins form a functional two-component system that plays a role in sensing changes in environmental conditions. As detailed above, the rationale for studying this particular system and for the nomenclature applied, stems from the homology of these proteins to the B. burgdorferi Hpk2-Rrp2 two-component system, a key transducer of environmental signals (Blevins et al., 2009; Boardman et al., 2008; Burtnick et al., 2007; Ouyang et al., 2008; Yang et al., 2003). The goals of this study were to assess the sequence properties, transcriptional expression patterns, functional activity and environmental responsiveness of this previously uncharacterized two-component regulatory system.

To assess the molecular properties of Hpk2 and Rrp2, PCR, DNA sequence and database analyses were conducted. The genes are universal and the putative functional domains and residues of hpk2 and rrp2 are conserved among all T. denticola isolates that have been analyzed. The sequence analyses detailed above revealed that the N-terminal PAS domain of Hpk2 harbors a 15 amino acid insertion that is not found in PAS domains of other bacteria (http://cmr.jcvi.org.). This insertion was detected in all T. denticola isolates but not in Hpk2 orthologs of other spirochetes including T. vincentii, T. pallidum, Borrelia spps, and the Leptospira. It remains to be determined if this insert imparts unique biological characteristics or influences the activity of Hpk2. Conserved within the Hpk2 PAS domain is a putative heme-binding pocket. Heme binding domains allow for the sensing of redox potential and or oxygen levels (Galperin, 2004, 2006; Taylor and Zhulin, 1999). The features of Hpk2 and Rrp2 suggest that this putative two-component system may be an important contributor to the sensing of environmental changes that occur in the subgingival crevice as periodontal disease progresses.

Analyses of a panel of T. denticola isolates demonstrated that the genes up and downstream of the hpk2-rrp2 genes of T. denticola 35405 are conserved in sequence, gene order and orientation. Several of these genes have short intergenic spacers or have overlapping coding sequence. Consistent with this, transcriptional analyses revealed that hpk2-rrp2 are co-transcribed as part of a larger polycistronic mRNA that includes FtsJ (23S rRNA methytransferase), DnaK (DNA polymerase III tau/gamma subunit), CvpA (colicin V production factor), a hypothetical ORF and MurG (peptidogylcan synthesis). Transcript levels were 100 fold higher in late-stage cultures indicating that expression of the operon responds to stimuli associated with growth phase and or cell density. The potential significance of the co-expression of these genes is discussed below.

The ability of the Hpk2-Rrp2 two-component system system to function as a cognate kinase-response regulator pair was demonstrated in vitro using recombinant Hpk2 and Rrp2. Autophosphorylation progressed in a linear fashion out to 30 min and then reached a plateau. Phosphotransfer from Hpk2 to Rrp2 occurred rapidly but was completely dependent on the preloading of Hpk2 with phosphate. This is consistent with that previously demonstrated for the T. denticola AtcRS system (Frederick et al., 2008). Premature interaction of Rrp2 with monomeric-unphosphorylated Hpk2 might inhibit dimerization, a necessary step for phosphotransfer. Kinase dimerization is thought to result in the presentation of a stable interaction surface for the cognate response regulator (McEvoy et al., 1998; Ohta and Newton, 2003; Stock et al., 2000; Wright and Kadner, 2001).

The potential contribution of the PAS domain as a whole in environmental sensing and autophosphorylation was assessed by generating a recombinant Hpk2 truncation mutant lacking the PAS domain (Hpk2ΔPAS). Precedent for assessing the function of individual domains of his-kinases was established in earlier studies (Scholten and Tommassen, 1993). As an example, the role of the PhoR PAS domain was assessed by domain deletion. Deletion of the PAS domain from this histidine kinase provided information about its functional role without abolishing the activity of the autophosphorylation or phosphotransfer associated domains (Yamada et al., 1990). As demonstrated here, autophosphorylation kinetics of Hpk2 differed significantly for full length recombinant Hpk2 under aerobic conditions versus under anaerobic conditions. Autophosphorylation of full length Hpk2 occurred more rapidly and reached a higher level under anaerobic conditions. Deletion of the PAS domain significantly decreased Hpk2 autophosphorylation specifically under anaerobic condidtions (See Fig. 3). These data indicate a link between the PAS domain, Hpk2 autophosphorylation efficiency, and environmental conditions.

While the regulon controlled by the Hpk2-Rrp2 two-component regulatory system remains to be defined, the putative functions of the other proteins encoded by the hpk2-rrp2 operon suggests that they may play an important role in facilitating the outgrowth of T. denticola. Contained within this operon are genes encoding proteins critical for DNA replication, cell wall synthesis and translational efficiency. As environmental conditions associated with the progression of periodontal disease develop, the hpk2-rrp2 operon becomes transcriptionally activated. This presumably leads to a significant increase in the production of murG (peptidoglycan biosynthesis), DnaX (DNA replication) and FtsJ (translational efficiency) all of which could play a key role in facilitating the rapid outgrowth of T. denticola. The presence of CvpA (colicin V production factor) and tde1972 (a potential toxin of the α-KTx17 toxin sub-family) (Zhang et al., 2004a; Zhang et al., 2004b) within the operon is intriguing (Fath et al., 1989). These proteins are not known to contribute to core functions but it is possible that as T. denticola growth becomes stimulated by physiochemical changes in the periodontal pocket, the production of CvpA and tde1972 could contribute to inhibiting the growth of competitors or inhibit host immune effector cells allowing T. denticola to become a dominant organism. Future analyses will test these hypotheses. In conclusion, the results presented here, coupled with the homology of the Hpk2-Rrp2 to two-component systems of other bacteria suggest potential involvement in regulating adaptive responses associated with changing environmental conditions.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by grants to R.T.M. from NIAID and NIDCR.

References

- Beck LL, Smith TG, Hoover TR. Look, no hands! Unconventional transcriptional activators in bacteria. Trends Microbiol. 2007;15:530–537. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2007.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blevins JS, Xu H, He M, Norgard MV, Reitzer L, Yang XF. Rrp2, a {sigma}54-dependent transcriptional activator of Borrelia burgdorferi, activates rpoS in an enhancer-independent manner. J Bacteriol. 2009 doi: 10.1128/JB.01721-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boardman BK, He M, Ouyang Z, Xu H, Pang X, Yang XF. Essential role of the response regulator Rrp2 in the infectious cycle of Borrelia burgdorferi. Infect Immun. 2008;76:3844–3853. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00467-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burtnick MN, Downey JS, Brett PJ, Boylan JA, Frye JG, Hoover TR, Gherardini FC. Insights into the complex regulation of rpoS in Borrelia burgdorferi. Mol Microbiol. 2007;65:277–293. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05813.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caimano MJ, Iyer R, Eggers CH, Gonzalez C, Morton EA, Gilbert MA, Schwartz I, Radolf JD. Analysis of the RpoS regulon in Borrelia burgdorferi in response to mammalian host signals provides insight into RpoS function during the enzootic cycle. Mol Microbiol. 2007;65:1193–1217. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05860.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotter PA, Stibitz S. c-di-GMP-mediated regulation of virulence and biofilm formation. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2007;10:17–23. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2006.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellen RP, Galimanas VB. Spirochetes at the forefront of periodontal infections. Periodontology 2000. 2005;38:13–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.2005.00108.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fath MJ, Mahanty HK, Kolter R. Characterization of a purF operon mutation which affects colicin V production. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:3158–3161. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.6.3158-3161.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frederick JR, Rogers EA, Marconi RT. Analysis of a growth-phase-regulated two-component regulatory system in the periodontal pathogen Treponema denticola. J Bacteriol. 2008;190:6162–6169. doi: 10.1128/JB.00046-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galperin MY, Nikolskaya AN, Koonin EV. Novel domains of the prokaryotic two-component signal transduction systems. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2001;203:11–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2001.tb10814.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galperin MY. Bacterial signal transduction network in a genomic perspective. Environ Microbiol. 2004;6:552–567. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2004.00633.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galperin MY. Structural classification of bacterial response regulators: diversity of output domains and domain combinations. J Bacteriol. 2006;188:4169–4182. doi: 10.1128/JB.01887-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haffajee AD, Socransky SS. Microbiology of periodontal diseases: introduction. Periodontol 2000. 2005;38:9–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.2005.00112.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hager J, Staker BL, Bugl H, Jakob U. Active site in RrmJ, a heat shock-induced methyltransferase. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:41978–41986. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205423200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handfield M, Baker HV, Lamont RJ. Beyond good and evil in the oral cavity: insights into host-microbe relationships derived from transcriptional profiling of gingival cells. J Dent Res. 2008;87:203–223. doi: 10.1177/154405910808700302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolenbrander PE, Andersen RN, Blehert DS, Egland PG, Foster JS, Palmer RJ., Jr Communication among oral bacteria. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2002;66:486–505. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.66.3.486-505.2002. table of contents. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolenbrander PE, Palmer RJ, Jr, Rickard AH, Jakubovics NS, Chalmers NI, Diaz PI. Bacterial interactions and successions during plaque development. Periodontol 2000. 2006;42:47–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.2006.00187.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koretke KK, Lupas AN, Warren PV, Rosenberg M, Brown JR. Evolution of two-component signal transduction. Mol Biol Evol. 2000;17:1956–1970. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loesche WJ. The role of spirochetes in periodontal disease. Adv Dent Res. 1988;2:275–283. doi: 10.1177/08959374880020021201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loesche WJ, Grossman NS. Periodontal disease as a specific, albeit chronic, infection: diagnosis and treatment. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2001;14:727–752. doi: 10.1128/CMR.14.4.727-752.2001. table of contents. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lybecker MC, Samuels DS. Temperature-induced regulation of RpoS by a small RNA in Borrelia burgdorferi. Mol Microbiol. 2007;64:1075–1089. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDowell JV, Frederick J, Stamm L, Marconi RT. Identification of the gene encoding the FhbB protein of Treponema denticola, a highly unique factor H-like protein 1 binding protein. Infect Immun. 2007;75:1050–1054. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01458-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDowell JV, Huang B, Fenno JC, Marconi RT. Analysis of a unique interaction between the complement regulatory protein factor H and the periodontal pathogen Treponema denticola. Infect Immun. 2009;77:1417–1425. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01544-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEvoy MM, Hausrath AC, Randolph GB, Remington SJ, Dahlquist FW. Two binding modes reveal flexibility in kinase/response regulator interactions in the bacterial chemotaxis pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:7333–7338. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.13.7333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moglich A, Ayers RA, Moffat K. Structure and signaling mechanism of Per-ARNT-Sim domains. Structure. 2009;17:1282–1294. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2009.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohammadi T, Karczmarek A, Crouvoisier M, Bouhss A, Mengin-Lecreulx D, den Blaauwen T. The essential peptidoglycan glycosyltransferase MurG forms a complex with proteins involved in lateral envelope growth as well as with proteins involved in cell division in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 2007;65:1106–1121. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05851.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morozova OV, Dubytska LP, Ivanova LB, Moreno CX, Bryksin AV, Sartakova ML, Dobrikova EY, Godfrey HP, Cabello FC. Genetic and physiological characterization of 23S rRNA and ftsJ mutants of Borrelia burgdorferi isolated by mariner transposition. Gene. 2005;357:63–72. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2005.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohta N, Newton A. The core dimerization domains of histidine kinases contain recognition specificity for the cognate response regulator. J Bacteriol. 2003;185:4424–4431. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.15.4424-4431.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouyang Z, Blevins JS, Norgard MV. Transcriptional interplay among the regulators Rrp2, RpoN and RpoS in Borrelia burgdorferi. Microbiology. 2008;154:2641–2658. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2008/019992-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paster BJ, Boches SK, Galvin JL, Ericson RE, Lau CN, Levanos VA, Sahasrabudhe A, Dewhirst FE. Bacterial diversity in human subgingival plaque. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:3770–3783. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.12.3770-3783.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paster BJ, Olsen I, Aas JA, Dewhirst FE. The breadth of bacterial diversity in the human periodontal pocket and other oral sites. Periodontol 2000. 2006;42:80–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.2006.00174.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers EA, Terekhova D, Zhang HM, Hovis KM, Schwartz I, Marconi RT. Rrp1, a cyclic-di-GMP-producing response regulator, is an important regulator of Borrelia burgdorferi core cellular functions. Mol Microbiol. 2009;71:1551–1573. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06621.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scholten M, Tommassen J. Topology of the PhoR protein of Escherichia coli and functional analysis of internal deletion mutants. Mol Microbiol. 1993;8:269–275. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01571.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seshadri R, Myers GSA, Tettelin H, Eisen JA, Heidelberg JF, Dodson RJ, Davidsen TM, DeBoy RT, Fouts DE, Haft DH, Selengut J, Ren Q, Brinkac LM, Madupu R, Kolonay J, Durkin SA, Daugherty SC, Shetty J, Shvartsbeyn A, Gebregeorgis E, Geer K, Tsegaye G, Malek J, Ayodeji B, Shatsman S, McLeod MP, Smajs D, Howell JK, Pal S, Amin A, Vashisth P, McNeill TZ, Xiang Q, Sodergren E, Baca E, Weinstock GM, Norris SJ, Fraser CM, Paulsen IT. Comparison of the genome of the oral pathogen Treponema denticola with other spirochete genomes. PNAS. 2004;101:5646–5651. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307639101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simionato MR, Tucker CM, Kuboniwa M, Lamont G, Demuth DR, Tribble GD, Lamont RJ. Porphyromonas gingivalis genes involved in community development with Streptococcus gordonii. Infect Immun. 2006;74:6419–6428. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00639-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith KD, Lipchock SV, Ames TD, Wang J, Breaker RR, Strobel SA. Structural basis of ligand binding by a c-di-GMP riboswitch. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2009;16:1218–1223. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Socransky SS, Haffajee AD. Periodontal microbial ecology. Periodontol 2000. 2005;38:135–187. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.2005.00107.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stock AM, Robinson VL, Goudreau PN. Two-component signal transduction. Annu Rev Biochem. 2000;69:183–215. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.69.1.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stock AM. Diguanylate cyclase activation: it takes two. Structure. 2007;15:887–888. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2007.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor BL, Zhulin IB. PAS domains: internal sensors of oxygen, redox potential, and light. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1999;63:479–506. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.63.2.479-506.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright JS, 3rd, Kadner RJ. The phosphoryl transfer domain of UhpB interacts with the response regulator UhpA. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:3149–3159. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.10.3149-3159.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada M, Makino K, Shinagawa H, Nakata A. Regulation of the phosphate regulon of Escherichia coli: properties of phoR deletion mutants and subcellular localization of PhoR protein. Mol Gen Genet. 1990;220:366–372. doi: 10.1007/BF00391740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang XF, Alani SM, Norgard MV. The response regulator Rrp2 is essential for the expression of major membrane lipoproteins in Borrelia burgdorferi. Proc Natl Acad Scie USA. 2003;100:11001–11006. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1834315100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Raji A, Theisen M, Hansen PR, Marconi RT. bdrF2 of Lyme disease spirochetes is coexpressed with a series of cytoplasmic proteins and is produced specifically during early infection. J Bacteriol. 2005;187:175–184. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.1.175-184.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang N, Chen X, Li M, Cao C, Wang Y, Wu G, Hu G, Wu H. Solution structure of BmKK4, the first member of subfamily alpha-KTx 17 of scorpion toxins. Biochemistry. 2004a;43:12469–12476. doi: 10.1021/bi0490643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang N, Wu G, Wu H, Chalmers MJ, Gaskell SJ. Purification, characterization and sequence determination of BmKK4, a novel potassium channel blocker from Chinese scorpion Buthus martensi Karsch. Peptides. 2004b;25:951–957. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2004.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]