Sugars appended to pharmaceutically important natural products influence key pharmacological properties and/or molecular mechanism of action.[1] However, studies designed to systematically understand and/or exploit the role of carbohydrates in drug discovery are often limited by the availability of practical synthetic and/or biosynthetic tools.[2] Among the contemporary options to address this limitation,[3–4] chemoenzymatic glycorandomization utilizes a set of flexible enzymes consisting of an anomeric kinase, sugar-1-phosphate nucleotidylytransferase, and natural product glycosyltransferase (GT).[4–6] While chemoenzymatic glycorandomization has been successfully applied to alter the natural sugar moieties of numerous natural products,[4–8] the process remains primarily restricted by enzyme specificity and availability of suitable GTs for the target of interest. Thus, although there is precedent for improving non-glycosylated therapeutics via glycoconjugation, including colchicine,[9] mitomycin,[10] podophyllotoxin,[11] rapamycin,[12] isophosphoramide mustards,[13] or taxol,[14] such targets remain beyond chemoenzymatic strategies. Recent studies on OleD, the oleandomycin (1) GT from Streptomyces antibioticus (Scheme 1a), revealed an enhanced triple mutant (A242V/S132F/P67T, referred to herein as ‘ASP’) that displayed marked improvement in proficiency and substrate promiscuity.[4] To probe the synthetic utility of this enhanced catalyst and expand upon previous reports of acceptor promiscuity for wild-type (WT) OleD,[15] we report a comparison of the aglycon specificities of the WT and ‘ASP’ OleD variants toward 137 drug-like acceptors. This study highlights the ability of OleD variants to glucosylate a total of 71 diverse acceptors, catalyze iterative glycosylation with numerous substrates, and establishes OleD as the first multifunctional GT capable of generating O-, S- and N-glycosides.

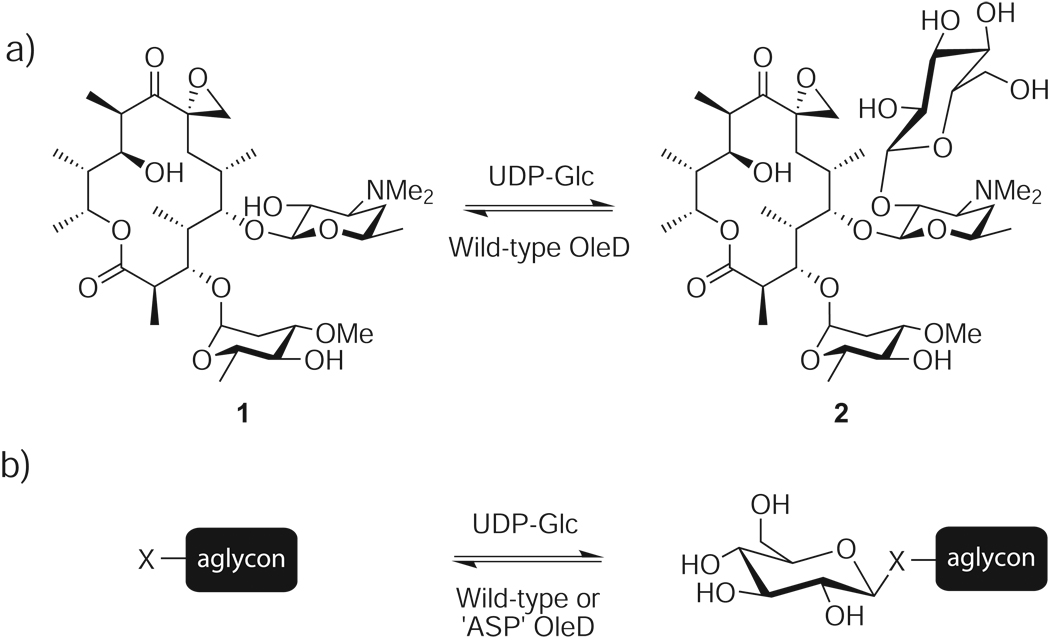

Scheme 1.

a) Natural reaction catalyzed by WT OleD b) General reaction for probing aglycon promiscuity in vitro against a panel of 137 library members, X = OH, SH, NH2, or NHR.

Enzymes for the study were overproduced as N-terminal His-tag-fusions in E. coli and purified to homogeneity as previously described.[4,5] Each member of the acceptor library (3-139) were first assessed as substrates for enzyme-catalyzed glucosylation with UDP-glucose (UDP-Glc) as the donor and either WT or ‘ASP’ OleD as catalyst (Scheme 1b). The library included molecules with diverse nucleophiles and representative alkaloid, beta-lactam, enediyne, non-ribosomal peptide, polyketide, and steroid natural products. Each member was assayed using a single ‘universal’ assay condition (50 mM Tris HCl [pH 8.0], 5 mM MgCl2, 0.5 μg µl−1 purified enzyme, 2.5 mM UDP-Glc, 1 mM aglycon, 25 °C, 16 hr). Glycoside production was determined by HPLC and LC-MS and control reactions lacking either enzyme or UDP-glucose confirmed products were dependent upon both enzyme and donor.

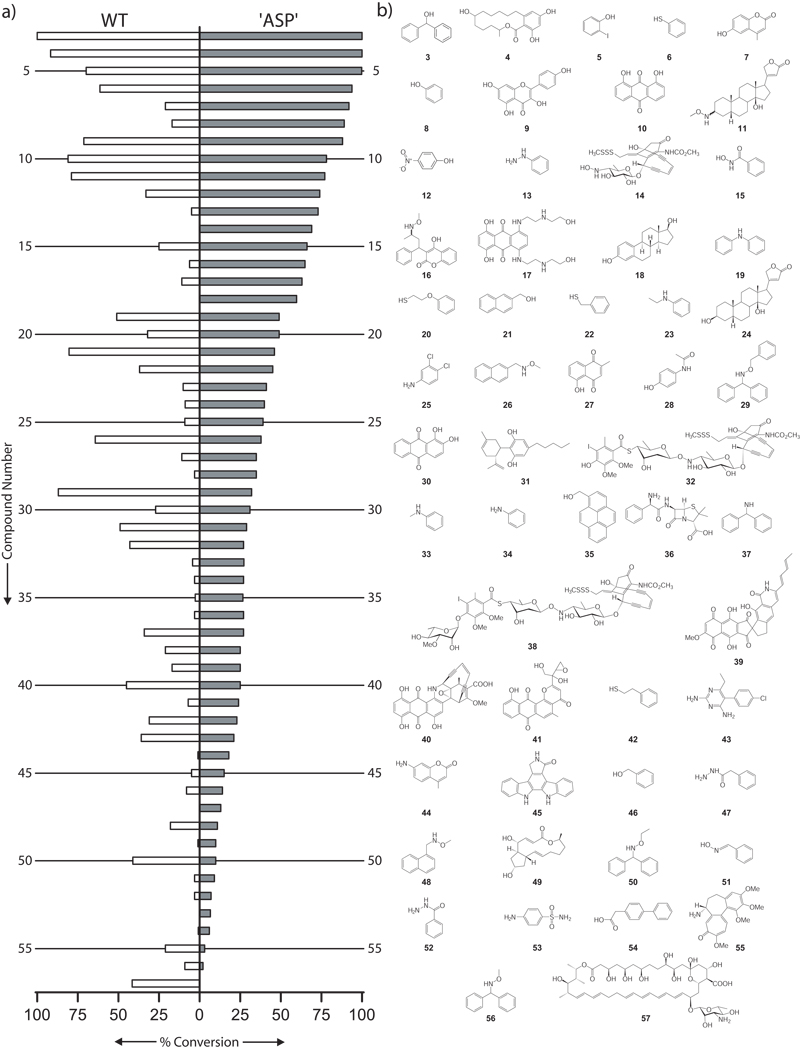

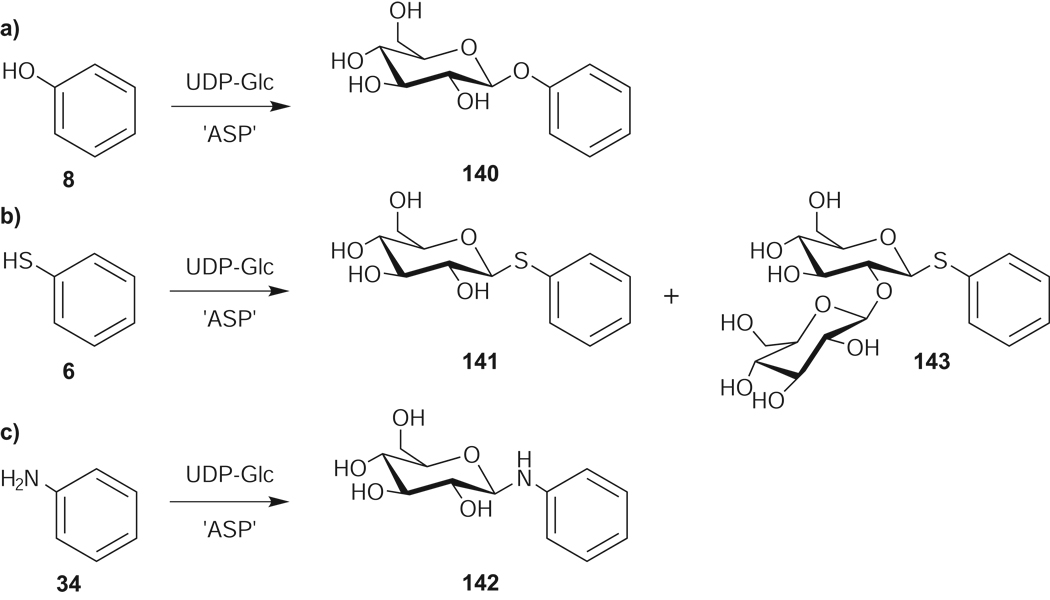

From this first-pass analysis, enzyme-catalyzed glucosylation of 71 of the 137 library members (52%) was observed (Figure 1). ‘ASP’ provided higher conversion with 56 of the 71 substrates and, in 10 cases (14, 18, 47, 53, 66, 67 and 70–73), product was observed only with ‘ASP’. In contrast, only polyene 57 was a unique substrate of WT OleD. Notably, of the 71 new substrates, 4 (6, 20, 22, 42) and 20 (13, 19, 23, 26, 29, 33, 34, 37, 43-45, 47, 48, 50, 52, 53, 55, 56, 61, 63, and 72) library members exclusively contained either S- or N-based nucleophiles, respectively. While the first-pass LC-MS analysis could not distinguish regio- or stereoselectivity, it is important to note that among the subgroup of library members containing multiple nucleophiles (34 members), 20 led to a single, chromatographically-distinct, monoglucosylated product. Perhaps most surprising was that 13 substrates (3, 4, 6, 9, 18-21, 23, 26, 29, 33, and 35) led to products with masses corresponding to the addition of multiple glucose moieties and within this group, 10 (3, 6, 19–21, 23, 26, 29, 33, 35) contained only a single heteroatom, implicating disaccharide formation via iterative glycosylation. To confirm O-, S- and N-glucoside formation, iterative glycosylation, and determine anomeric stereoselectivity, a select set of OleD-catalyzed reactions with simple aromatic model acceptors phenol (8), thiophenol (6), and aniline (34) were studied in depth. NMR characterization of products isolated from large scale reactions was consistent with the β-O-, S- and N-glucosides (140–143, Figure 2, J = 6.7, 7.8, and 9.6 Hz for H1, respectively). Iterative glycosylation of model acceptor 6 was also determined to be both regio- and stereoselective to provide the 2’-O-(β-D-glucosyl)-glucoside 143 (J = 7.8 and 9.8 Hz for H1 and H1’, respectively). Interestingly, while the kinetic parameters for all three model substrates fell within the range of previously reported values (Supplementrary Table 1),[4,5] the ranked order of WT OleD catalytic efficiency (kcat/Km; thiophenol > phenol ≈ aniline) differed from that for ‘ASP’ (phenol > aniline > thiophenol). Consistent with the enhanced proficiency of ‘ASP’,[4] this mutant was improved 25-, 5-, and 4- fold, respectively, toward phenol (8), aniline (34), and thiophenol (6).

Figure 1.

a) Percent conversion of each library member with both WT and ‘ASP’ OleD. Members are listed in descending order of ‘ASP’ conversion with numbering corresponding to the structures listed in (b). b) Structures of the corresponding library members. Compounds leading to trace products (58–73, >5% conversion) or no conversion (74–139) are listed in the Supplementary Information.

Figure 2.

Products isolated from large scale enzymatic reactions of ‘ASP’ OleD with (a) phenol (8), (b) thiophenol (6), and (c) aniline (34).

In terms of potential for combinatorial applications, this study revealed WT OleD and ‘ASP’ to glucosylate a diverse range of ‘drug-like’ scaffolds including anthraquinones, indolocarbozoles, polyenes, cardenolides, steroids, macrolides, beta-lactams, and enediynes (Figure 1). Of particular note is that library members (or closely related compounds) are clinical analgesic (28), gout (55), congestive heart failure (24), hormone replacement (18), antifungal (57), antiparasitic (43), antibacterial (36, 53, 63, 69), and anticancer (14, 17, 32, 38, 62) agents.[16] Although there exist a few reported natural or engineered ‘bifunctional’ GTs, capable of forming two types of glycosidic bonds (O/N-, O/S-, or O/C-),[17–20] this is the first example of a GT capable of catalyzing O-, S-, and N-glycosidic bond formation. Moreover, putative ‘ASP’-catalyzed glycosidic bond formation was observed with aliphatic alcohols, aliphatic thiols, N-substituted anilines, oximes, hydrazines, hydrazides, N-hydroxyamides, O-substituted oxyamines, and carboxylic acids (Figure 1), the heteroatom nucleophiles of which represent a pKa range of ~ 4 – 14.[21] Although glycosides of oximes,[22] hydrazines,[23] hydrazides,[24] N-hydroxyamides,[25] and O-substituted oxyamines[9,26] have been chemically synthesized, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first enzyme-catalyzed route. While a few naturally-occurring iterative GTs also exist,[8] this is the first report of OleD-catalyzed iterative glycosylation. Cumulatively, the scaffold, nucleophile, and iterative adaptability of OleD clearly sets the stage for further engineering of custom GT catalysts for many applications.[4,5,27]

In the context of GT promiscuity, the role of OleD in macrolide self-resistance (1–2, Scheme 1a) may require this enzyme to uniquely adapt to accommodate alternative acceptors. Yet, even with library members containing multiple nucleophiles, the majority of reactions studied were remarkably regio- and stereoselective. Although other reports have highlighted moderate promiscuity of natural product GTs,[6,10,11,28–30] the underlying structural basis for maintaining specificity with variant acceptors is not well understood. Studies designed to understand the promiscuity of other enzyme classes implicate dramatic enzyme conformational changes,[31] voluminous active sites,[32] or similar conformational binding of unrelated compounds within the active site[33] as potential contributors to promiscuity. Consistent with this, substrate modelling of the promiscuous GT VinC suggested that gross molecular size and hydrogen-bonding interactions play significant roles.[29] Future structural studies of enhanced OleD variants bound to diverse substrates are critical to extend our currently limited understanding of GT specificity and catalysis. However, given the high conservation of the GT-B structural fold among natural product GTs,[34] including OleD,[35] other examples of dramatically promiscuous GTs are likely to emerge.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

The authors thank the University of Wisconsin–Madison School of Pharmacy Analytical Facility for analytical support. This research was supported in part by National Institutes of Health Grants AI52218 and U19 CA113297.

A Sweet Library Two variants (WT and a triple mutant) of glycosyltransferase (GT) OleD have been shown to catalyze glycosylation of over 70 substrates, formation of O-, S-, and N-glycosidic bonds, and iterative glycosylation. Identified substrates include nucleophiles not previously known to act in GT reactions and span numerous natural product and therapeutic drug classes.##Enzyme Catalyzed Glycosylation

carbohydrate

enzyme

glycoside

glycosylation

natural products

References

- 1.a Kren V, Řezanka T. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2008 doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2008.00124.x. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Thorson JS, Hosted TJ, Jr, Jiang J, Biggins JB, Ahlert J. Curr. Org. Chem. 2001;5:139–167. [Google Scholar]; c Weymouth-Wilson AC. Nat. Prod. Rep. 1997;14:99–110. doi: 10.1039/np9971400099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.a Salas JA, Méndez C. Trends Microbiol. 2007;15:119–232. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2007.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Thibodeaux CJ, Melançon CE, Liu H. Nature. 2007;446:1008–1016. doi: 10.1038/nature05814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Blanchard S, Thorson JS. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2006;10:263–271. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2006.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.a Griffith BR, Langenhan JM, Thorson JS. Curr. Opin. Biotech. 2005;16:622–630. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2005.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Langenhan JM, Griffith BR, Thorson JS. J. Nat. Prod. 2005;68:1696–1711. doi: 10.1021/np0502084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.a Williams GJ, Zhang C, Thorson JS. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2007;3:657–662. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2007.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Williams GJ, Thorson JS. Nat. Protoc. 2008;3:357–362. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Williams GJ, Goff RD, Zhang C, Thorson JS. Chem. Biol. 2008;15:393–401. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2008.02.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fu X, Albermann C, Jiang J, Liao J, Zhang C, Thorson JS. Nat. Biotech. 2003;21:1467–1469. doi: 10.1038/nbt909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang C, Griffith BR, Fu Q, Albermann C, Fu X, Lee I, Li L, Thorson JS. Science. 2006;313:1291–1294. doi: 10.1126/science.1130028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang C, Albermann C, Fu X, Thorson JS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:16420–16421. doi: 10.1021/ja065950k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ahmed A, Peters NR, Fitzgerald MK, Watson JA, Jr, Hoffmann FM, Thorson JS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:14224–14225. doi: 10.1021/ja064686s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ghiorghis A, Talebian A, Clarke R. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 1992;29:290–296. doi: 10.1007/BF00685947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Imbert TF. Biochimie. 1998;80:207–222. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9084(98)80004-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abel M, Szweda R, Trepanier D, Yatscoff RW, Foster RT. U.S. Patent No. US. 7,160,867. 2007

- 13.Veyhl M, et al. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95:2914–2919. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.6.2914. see Supporting Information. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu D, Sinchaikeul S, Reddy PVG, Chang M, Chen S. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2007;17:617–620. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2006.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang M, Proctor MR, Bolam DN, Errey JC, Field RA, Gilbert HJ, Davis BG. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:9336–9337. doi: 10.1021/ja051482n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lacy CF, Armstrong LL, Goldman MP, Lance LL, editors. Drug Information Handbook. 16th Ed. Ohio, USA: Lexi-Comp, Hudson; 2008. pp. 22–30.pp. 112–114.pp. 314–315.pp. 381–382.pp. 427–430.pp. 580–585.pp. 723–725.pp. 1151–1152.pp. 1350–1351.pp. 1609–1610.pp. 1065–1067. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Loutre C, Dixon DP, Brazier M, Slater M, Cole DJ, Edwards R. Plant J. 2003;34:485–493. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2003.01742.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brazier-Hicks M, Offen WA, Gershater MC, Revett TJ, Lim E, Bowles DJ, Davies GJ, Edwards R. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:20238–20243. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706421104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Patana A, Kurkela M, Finel M, Goldman A. Protein Eng. Des. Sel. 2008 doi: 10.1093/protein/gzn030. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dürr C, Hoffmeister D, Wohlert S, Ichinose K, Weber M, Von Mulert U, Thorson JS, Bechthold A. Angew Chem. 2004;118:8006–8010. doi: 10.1002/anie.200453758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2004;43:2962–2965. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Data available at http://www.chem.wisc.edu/areas/reich/pkatable/

- 22.Rodriguez EC, Marcaurelle LA, Bertozzi CR. J. Org. Chem. 1998;63:7134–7135. doi: 10.1021/jo981351n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Holland JP, et al. Inorg. Chem. 2007;46:465–485. doi: 10.1021/ic0615628. see Supporting Information. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Takeda Y. Carb. Res. 1979;77:9–23. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thomas M, Gesson J, Papot S. J. Org. Chem. 2007;72:4262–4264. doi: 10.1021/jo0701839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.a Peri F, Deutman A, La Ferla B, Nicotra F. ChemComm. 2002:1504–1505. doi: 10.1039/b203605c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Carrasco MR, Brown RT. J. Org. Chem. 2003;68:8853–8858. doi: 10.1021/jo034984x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.a Aharoni A, Thieme K, Chiu CPC, Buchini S, Lairson LL, Chen H, Strynadka NCJ, Wakarchuk WW, Withers SG. Nat. Methods. 2006;3:609–614. doi: 10.1038/nmeth899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Persson BMM, Palcic MM. Anal. Biochem. 2008;378:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2008.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Meyers CLF, Oberthür M, Anderson JW, Kahne D, Walsh CT. Biochem. 2003;42:4179–4189. doi: 10.1021/bi0340088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Minami A, Uchida R, Eguchi T, Kakinuma K. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:6148–6149. doi: 10.1021/ja042848j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang C, et al. ChemBioChem. 2006;7:795–804. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200500504. see Supporting Information. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ekroos M, Sjögren T. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:13682–13687. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603236103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kuzuyama T, Noel JP, Richard SB. Nature. 2005;435:983–987. doi: 10.1038/nature03668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu C, Deavours BE, Richard SB, Ferrer J, Blount JW, Huhman K, Dixon RA, Noel JP. Plant Cell. 2006;18:3656–3669. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.041376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lairson LL, Henrissat B, Davies GJ, Withers SG. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2008;77:521–555. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.76.061005.092322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bolam DN, et al. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:5336–5341. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607897104. see Supporting Information. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.