Abstract

Enzyme active site dynamics at femtosecond to picosecond time scales are of great biochemical importance, but remain relatively unexplored due to the lack of appropriate analytical methods. Two-dimensional infrared (2D IR) spectroscopy is one of the only methods that can examine chemical and biological motions at this time scale, but all the IR-probes used so far were specific to a few unique enzymes. The lack of IR-probes of broader specificity is a major limitation to further 2D IR studies of enzyme dynamics. Here we describe the synthesis of a general IR-probe for nicotinamide dependent enzymes. This azo analog of the ubiquitous cofactor nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide is found to be stable and bind to several dehydrogenases with dissociation constants similar to the native cofactor. The infrared absorption spectra of this probe bound to several enzymes indicate that it has significant potential as a 2D IR probe to investigate femtosecond dynamics of nicotinamide dependent enzymes.

Keywords: nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide, probe, infrared spectroscopy, femtosecond-picosecond, assays, isothermal titration calorimetry

Introduction

Protein motions are necessary for an enzyme's biological function,[1-6] but the role of enzyme dynamics at various timescales and their contribution toward catalytic activity is not clear. Enzymes undergo slow conformational sampling that involves large regions of the protein moving on time scales of nanoseconds to seconds. In addition, there are local motions that occur on the picosecond to femtosecond time scale. Theoretical studies by Schwartz and others [7-10] have suggested that, in some enzymes, protein promoting vibrations and internal motions at femtosecond (fs) to picosecond (ps) timescales are necessary for catalysis as they modulate the width and height of the activation barrier. Indirect experimental evidence of such motions comes from the anomalous kinetic isotope effects (KIEs) seen in many enzymes.[4, 5, 11- 13] This behavior is a hallmark of quantum tunneling, which requires that the nuclear wave functions of donor and acceptor potential wells should be close to each other and have degenerate energies. It has been suggested that protein dynamicsat the active site can cause fluctuations in the donor and the acceptor distance that result in coupling of these environmental dynamics to the C-H bond activation.[14,15] Although theoretical studies have suggested that enzyme motions at the fs-ps time scale are more likely to be involved in covalent bond activation than slower motions, they are relatively unexplored. The main reason is the lack of a suitable analytical tool that will afford exploration of these dynamics in a large and significant group of enzymes and other biological systems.

Recently developed nonlinear vibrational spectroscopies can directly investigate the fast motions in proteins.[16-18] Infrared photon echo and 2D IR spectroscopies can record equilibrium fluctuations with sub-picosecond time resolution. Previous studies of globular proteins,[19,20] membrane proteins,[21,22] amyloid fibers,[23] HIV-1 reverse transcriptase,[24] carbonic anhydrases,[25] and formate dehydrogenase[26] have provided insights into protein structural dynamics at fs to ps time scales. The midIR chromophores used for these studies, however, are not generally applicable to most enzymatic systems. For example, we have recently reported the dynamics of formate dehydrogenase complexes using the azide anion as a probe of the active site motions.[26]This anion is a transition-state-analog inhibitor,[27] has a nanomolar binding constant, and forms stable complexes with FDH that exhibit a vibrational transition in the mid-IR in a region that is devoid of localized transitions from the enzyme. Unfortunately, azide ion does not bind to a broad range of enzymes. Furthermore, when it does bind it is not generally a good transition state analog. A general probe in mid-IR for 2D IR studies of protein dynamics is thus lacking., and the lack of suitable probes that bind to a wide range of enzyme is a major obstacle to more widespread applications of 2D IR spectroscopy to enzyme dynamics. A suitable IR probe for 2D IR studies should (a) bind with the enzyme at the active site, (b) have a broad specificity, to afford examination of a significant number of enzymes and biological systems, and (c) have a transition in a suitable region in the mid-IR spectrum.

Nicotinamide-dependent cofactors are necessary for the function of many enzymes and other biological systems. Analogs of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) have been widely studied to assess their binding affinities, optical properties, and enzymatic reactivity.[28] Here, we report the synthesis of a mid-IR active analog of NAD+ in which the amide group in the nicotinamide ring has been replaced with an azide. We also characterize its infrared absorption spectra to assess its potential as a 2D IR probe to investigate enzyme active-site dynamics. On the basis of these studies we conclude that azo-NAD+ is a suitable chromophore for 2D IR spectroscopy that can readily be incorporated into the active sites of NAD-dependent enzymes. Because NAD+ is a cofactor for numerous enzymes, such an analog should have widespread applicability for 2D IR studies of enzyme dynamics.

Materials and Methods

Materials

The starting materials 3-aminopyridine, sodium nitrite, sodium formate, sodium azide, phenylmethanesulphonylfluoride (PMSF), NADase and NAD+ are obtained from Aldrich and used as received. All solvents are obtained from commercial sources and used without further purification. C-18 silica gel is obtained from Analtech, Newark. Formate dehydrogenase (FDH, Candida boidinii) is obtained from Roche Diagnostics, Germany. Malate dehydrogenase (MDH, Porcine heart mitochondria) is obtained from Calzyme Laboratories Inc. CA. Glucose dehydrogenase (GDH, Bacillus megaterium) is obtained from USB Corp, OH. The synthesized products are characterized by UV-Vis spectroscopy (Varian, Cary300), HPLC (Aligent, 1200S), 1H-NMR (Bruker ,300 MHz), FTIR absorption(Bruker, Tensor27) and Mass spectroscopy (Mircromass Inc, Autospec).

Synthesis of Azopyridine

Azopyridine is synthesized as described by Sawanishi et al [29]. In short, 3-aminopyridine (8g, 0.08 mols) dissolves in 5M HCl and reacts with a solution of sodium nitrate (10g, 0.15 mols) at ≤ 5 °C for 10-15 min. A solution of sodium azide (13g, 0.15 mols) is added drop wise to this mixture for 10-15 minutes. The reaction continues for 30 minutes at room temperature and then is quenched until alkaline by Na2CO3. The oily liquid is filtered and extracted with CH2Cl2 (3 × 200 mL). The extract is purified using Silica-Gel chromatography with CH2Cl2-EtAc (1:1) to obtain the final product with a yield 5.57g, of pure product.(68.7%, overall yield). IH-NMR (δ, CDCl3): 7.2-7.4 (2H, m), 8.3-8.4 (2H, m). IR: 2134, 2094 cm−1. UV ; 287 nm. MS ; 120.1.

Preparation of NADase solution

Acetone-dried pig brain NADase (≥ 0.007 units/mg solid) is insoluble in water and requires proteolytic digestion for activation. 1g of NADase is suspended in 20 mM phosphate buffer (20 mL) at pH 7.5 and sonicated in dark maintaining a temperature at ≤ 5 °C. After 45 minutes, 5 mg of trypsin is added to the suspension, which we then place in an oven at 37 °C for an additional 45 minutes. A 0.1 M solution of serine protease inhibitor PMSF (360 μL) is added to the mixture to a final concentration of 2mM and the precipitate is then centrifuged at 20000g for 60 minutes at 5 ° C. The pale red activated NADase (~ 16 units/mL) obtained is carefully decanted and stored at 4 °C.

Synthesis of Azo-NAD+

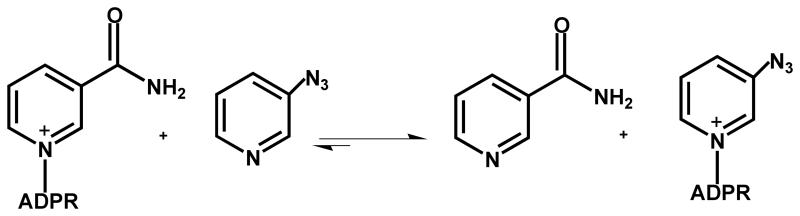

The azo-NAD+ is synthesized by modifying the base exchange reaction scheme proposed described by Hixson et al [30] (scheme 1). 3-azopyridine (410 mg, 3.41mols) dissolves in 5 mL of DMF and mixes with the activated NADase (18 mL) solution under dark conditions. An aqueous solution of NAD+ (150 mg, 0.23 mols) is then added to the mixture maintaining the pH at 7.5. The reaction is allowed to react for 12 hrs in the dark at 37 °C. Then, 25 mL of chloroform is added to the mixture to extract the azo-NAD+ in aqueous phase. Chloroform makes the aqueous solution turbid, which is centrifuged at 4 °C, carefully decanted into filter tubes (Amicon, Millipore), and further centrifuged. The filtrate is checked for absorbance at 303 nm and lyophilized. The crude product is separated by chromatography using C-18 silica gel with methanol-water as solvent in a flash column. Fractions with the highest absorptions at 260 nm and 303 nm are combined, rotary evaporated and lyophilized to obtain the final product (final yield 100 mg , 66.8%.). An HPLC run in a methanol-water gradient shows one major peak, which is assigned to azo-NAD+. IR: 2140 cm−1. UV-Vis : 260 nm, 303 nm. MS : 661.15, 660.12 . 1H-NMR (δ, D2O) : 4.4-3.9 (10H, m), 5.6 (1H, d), 5.8 (1H, d),7.6-7.7 (1H, m), 7.8 (1H, s), 7.9 (1H, s), 8.2 (1H, s), 8.3 (1H, d), 8.4 (1H, d).

Scheme 1.

Synthetic scheme for the production of azo-NAD+ from azopyridine and NAD+ (−).

Enzymatic reaction assays

Three model enzymes – Formate dehydrogenase (FDH), Malate dehydrogense (MDH) and Glucose dehydrogenase (GDH) were tested for activity with the azo-NAD+ analog as substrate or inhibitor.

The standard ultraviolet (UV) semi-micro cuvette (1 ml) assay contains 0.1 M phosphate buffer at pH 7.5 with the coenzyme analog and the respective enzymes. For enzymes where Azo-NAD+ serves as a substrate, the Michaelis constant (Km) and the first order catalytic rate (kcat) were measured using Eq. 1.

| (1) |

where ν is initial rate, the maximum velocity Vmax is [E] * kcat, ([E] ; enzyme concentration ) and [S], is the Azo-NAD+ concentration.

In cases, where Azo-NAD+ serves as an inhibitor, the inhibition constant (Ki) was obtained from initial velocity experiments using global fitting to the kinetic equation of competitive inhibition (Equation 2),

| (2) |

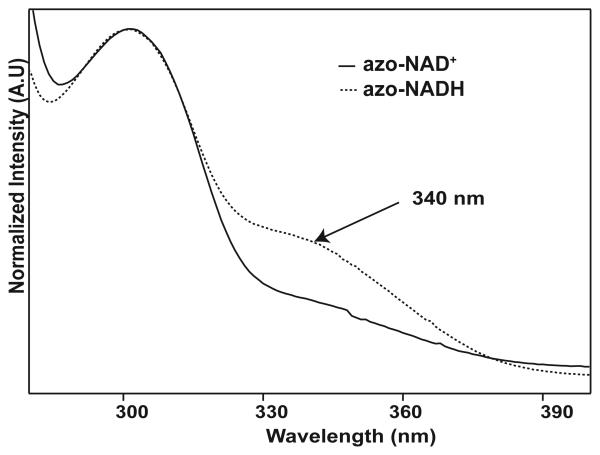

where [I] is the inhibitor concentration. In these experiments, the initial rate is measured for two minutes, using the absorbance increase at 340 nm (λmax for azo-NADH).

The experimental design for the binding studies, measured either with florescence titration or Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC), is dependent on the fluorescence efficiency, binding affinity and Weisman c-parameter of the enzymes with azo-NAD+.[31] The ITC experiments are performed with a MicroCal VP-ITC calorimeter with the coenzyme analog at pH 7.5. Heats of dilution are subtracted from the raw heats and the integrated heat obtained by titrating azo-NAD+ with each enzyme complex is fitted to a single-site binding model in Origin software for ITC (Microcal) to determine the binding constant (Kd). Fluorescence titrations are performed on a Varian flourometer to obtain the binding affinity of ligands to glucose dehydrogenase (GDH). A solution of GDH is tritrated with either azo-NAD+ alone (for binary complex) or both azo-NAD+ and glucono- -lactone (for ternary complex) at pH 7.5. The fluorescence emission is observed at 348 nm when excited at 295 nm. The maximum fluorescence (Qmax) is defined as fluorescence at 348 nm of the free GDH and observed fluorescence (Qobs) is defined as the fluorescence after addition of titrant. The decrease in fluorescence emission (1-(Qobs/Qmax)) × 100 %) with different concentration of azo-NAD+ is fit to a Langmuir binding model[32] (Equation 3) to obtain the binding affinities.

| (3) |

where Bmax and [A] are the maximum specific binding and ligand concentration respectively.

Fourier transform infrared spectra (FTIR) of the coenzyme analog both free in buffer solution and bound to the enzymes are collected using a Bruker Tensor 27 equipped with a nitrogen cooled MCT detector. All spectra are measured in phosphate buffer at pH 7.5.

Results and Discussion

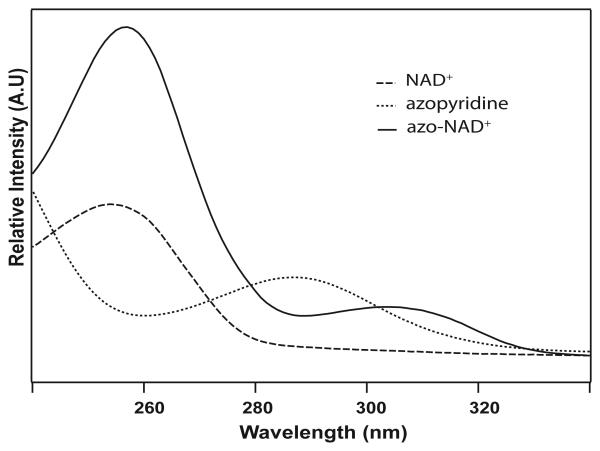

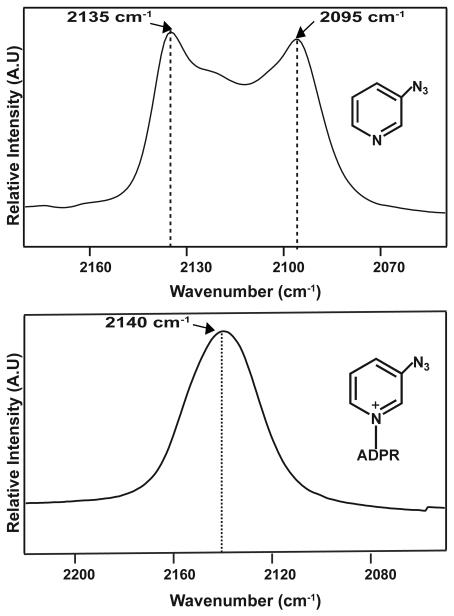

Although azo-NAD+ has been synthesized previously,[30] it was never purified and neither its kinetic nor spectroscopic properties were characterized quantitatively. The synthesis of azo-NAD+ requires control of both the pH and the mole ratio between 3-azopyridine and NAD+. Once prepared, the analog is a white solid that is soluble in phosphate buffer and methanol at room temperature and has a unique UV absorption at 303 nm that is distinct from both 3-azopyridine, and NAD+ as shown in Figure 1. The ratio of the UV absorbance at 260 nm to that at 303 nm is 4:1. This ratio remains unchanged in phosphate buffer pH 7.5 for 24 hrs at 25 °C indicating that the analog is stable under normal physiological conditions. As seen in Figure 2, azo-NAD+ also exhibits a single peak in the mid-IR at 2140 cm−1, in contrast to 3-azopyridine, which has two peaks.

Figure 1.

Normalized UV absorption spectra of azo-NAD+ (−), azopyridine (…), and NAD+ (− −).

Figure 2.

IR absorption spectra of azopyridine (upper panel) and azo-NAD+ (lower panel).

The analog can behave as either an inhibitor or a substrate depending on the enzyme. With both FDH and GDH, it is an active substrate that reacts to form azo-NADH and CO2 or gluconolactone, respectively. The formation of azo-NADH is apparent from the UV absorption at 340 nm as seen in Figure 3. Azo-NADH also fluoresces at 430 nm, when excited at 340 nm in contrast to native NADH, which fluoresces at 460 nm.

Figure 3.

UV absorption spectra showing the conversion of azo-NAD+ to azo-NADH.

Table 1 shows the kinetic parameters for azo-NAD+ interacting with three different NAD-dependent enzymes: formate dehydrogenase (FDH), malate dehydrogenase (MDH), and glucose dehydrogenase (GDH). The dissociation constants (Kd) for the binary complexes of the enzymes with azo-NAD+ are typically within the range of 5-300 µM. Measurements of the dissociation constant for ternary complexes employ either the substrate, if azo-NAD+ is an inhibitor, or an inhibitor for enzymes where azo-NAD+ is an active substrate. In the case of FDH we use the transition-state-analog inhibitor azide, for MDH we use the substrate, malate, and for GDH, we use the product of the catalyzed reaction, gluconolactone. As expected, the Kd of azo-NAD+ for each ternary complex is lower than for the corresponding binary complex. Note that, in contrast to the other enzymes, for which we measure Kd by ITC, the binary and ternary dissociation constants of GDH were obtained by measuring the quenching of tryptophan florescence upon binding with the analog.

Table 1.

Kinetic and binding parameters of enzymes with the azo-NAD+ analog.

The kinetic results indicate that the binding affinity of the azo-NAD+ is comparable to that of native NAD+ for each of these enzymes.[28,33]The azo-NAD+ analog behaves as a substrate for with FDH and GDH and as a competitive inhibitor with MDH. It seems likely that the analog binds in the enzyme active site in a geometry that is similar to that for the native cofactor. The turnover number for Candida Boidinii FDH with NAD+ is reported to be 3.7 s−1, which compares favorably to our observation of 7.5 s−1 with azo-NAD+ [34]. The dissociation constant for NAD+ with GDH from Bacillus magenterium was reported to be 600 M, [35] which is similar to the 300 M dissociation constant we report for the azo-NAD-GDH complex. With MDH from sus scrofa, azo-NAD+ behaves as an inhibitor (KI = 83 μM) which is similar to Km of NAD+ (140 μM) with the same enzyme.[36; 37] These binding behaviors suggest that azo-NAD+ forms stable complexes with these three enzymes that are structurally and functionally similar to the enzyme with the native cofactor. Consequently, it seems likely that azo-NAD+ will be a general tool to probe the dynamics of NAD-dependent enzymes by 2D IR spectroscopy.

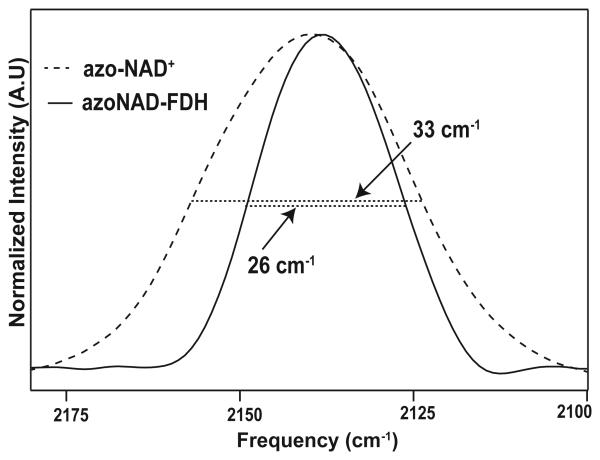

The azide antisymmetric stretching transition of azo-NAD+ is centered at 2140 cm−1 with a full width at half maximum (FWHM) of 33 ± 2 cm−1. The molar absorptivity at the maximum of this transition is 250 M−1cm−1, which is a little more than a factor of 10 smaller than that for the antisymmetric stretch of the azide anion. Thus, azo-NAD+ is a weaker chromophore than azide, but it still has a substantial transition moment suggesting that it could still be of significant potential value as a probe of protein dynamics using 2D IR spectroscopy. Figure 4 shows the FTIR spectra of azo-NAD+ free in solution and bound in the binary complex with FDH. Although the transition frequency does not shift much, the band narrows considerably, from 33 cm−1 to 26 cm−1. Similar band narrowing of the absorption spectrum upon binding to the protein has been seen frequently for chromophores that have been used to study protein dynamics via 2D IR spectroscopy, and it reflect that there is considerably less conformational heterogeneity in the enzyme than there is free in solution as is apparent too from the results of the 2D IR measurements. Table 2 summarizes the peak positions and line widths of the azo-transition in the binary and ternary complexes with each of the enzymes we have studied. In general there is very little change in the peak position or the line width among these enzymes even in comparing the binary and ternary complexes. Although the absorption spectra are not quantitatively different, it is well known that systems with quantitatively similar absorption profiles can exhibit qualitatively different dynamics when probed by 2D IR spectra.[20,38-39] That is because the infrared absorption line shape cannot be used to uniquely determine the character of the underlying spectral dynamics.

Figure 4.

IR absorption spectra of azo NAD+ in solution (−) and bound to FDH (−).

Table 2.

IR parameters for the azo-NAD+ analog with enzymes.

| Peak Position cm−1 | FWHM cm−1 | |

|---|---|---|

| Azo-NAD+ | 2140 | 33 |

| FDH-Azo-NAD+ | 2138 | 26 |

| FDH-Azo-NAD+-azide | 2142 a | 27 |

| MDH-Azo-NAD+ | 2142 | 28 |

| MDH-Azo-NAD+-malate | 2138 | 26 |

| GDH-Azo-NAD+ | 2141 | 27 |

| GDH-Azo-NAD+-Glucono-δ-lactone | 2142 | 28 |

Azide anion shows a peak at 2046 cm−1 compared to 2042 cm−1 for FDH-NAD+- azide

Azides are very sensitive probes of environmental dynamics and organic azides hold great potential for exploring protein dynamics using 2D IR spectroscopy. Azo-NAD+ provides a unique opportunity to investigate the active sites of numerous NAD-dependent enzymes that would otherwise be inaccessible by 2D IR. Based on our results, we can conclude that azo-NAD+ binds to several NAD-dependent enzymes with an affinity that is similar to that for native NAD+ and that the substitution of the azide at the amide position of the nicotinamide ring is a minor perturbation that, in at least two cases, does not inactivate the complex. Thus, we are able to use this analog to incorporate a vibrational reporter at the active site of the enzyme in a position where it is most likely to report dynamics that are functionally relevant. Furthermore, this chromophore should have widespread applicability to enzymes that utilize both NAD+ and NADP+. The development of an infrared chromophore that can be bound in the active site of a wide range of enzymes and is suitable for 2D IR spectroscopy is a significant result.

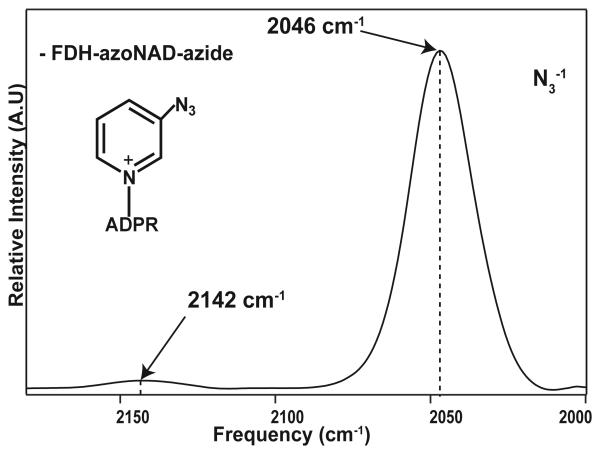

A particularly interesting case for further study is that of the ternary complex in FDH where we can probe both the azo-stretching vibration of azo-NAD+ as well as the azide anion antisymmetric stretch using 2D IR spectroscopy. Figure 5 shows the infrared absorption spectrum of this complex with both the azide anion and azo-NAD+ absorption bands. Because we have previously characterized the dynamics of the ternary complex of FDH with azide and NAD+ [26], the complex with the azo-NAD+ coenzyme is an especially interesting one in which we can determine the extent to which the two probes measure the same dynamics, and assess the magnitude of the perturbation to the dynamics of the active site caused by azo-NAD+. Even more significant is the potential of azo-NAD+ has to be a general probe of enzyme dynamics in NAD-dependent biological systems (e.g., dehydrogenases, reductases, oxidases, membranal proteins involved in cellular respiration, and more). Because the vibrational reporter is located on the coenzyme, it is possible to prepare a wide range of complexes with different substrates and inhibitors and to study both the binary and ternary complexes in these enzymes using 2D IR. In addition, because azo-NAD+ is also an active substrate for some of these enzymes, it is straightforward to reduce it to azoNADH, and to study complexes with the reduced form of the cofactor, with a complementary set of substrates and inhibitors. Furthermore, the same synthetic approach can also be extended to the preparation of azo-NADP+, which is an even better substrate of NADase (Dutta et al. unpublished data). Azo-NADP+ and azoNADPH would further extend the potential applications of vibrational spectroscopy as a probe for NADP+ and NADPH dependent enzymes.

Figure 5.

IR absorption spectrum of azo-NAD+ bound to FDH with azide anion.

Conclusions

We have synthesized, purified, and characterized the interaction of azo-NAD+, an azide derivatized analog of the NAD+ coenzyme. We have also measured the infrared absorption spectra of this analogue of the ubiquitous nicotinamide cofactor both free in solution and bound to several enzymes. For both FDH and GDH, azoNAD+ is an active substrate and binds with an affinity that is comparable to the natural coenzyme. For MDH, it is a competitive inhibitor. Azo-NAD+ exhibits a distinct vibrational transition associated with the antisymmetric stretching vibration of the azo group at 2140 cm−1, which is located in an ideal spectral region that is clear of other transitions associated with either the solvent or the protein. Although the transition moment is not as strong as for the azide anion, at 250 M−1cm−1, the molar absorptivity is certainly high enough to make it accessible 2D IR spectroscopy.[40] 2D-IR studies of azo-NAD+ in water have demonstrated that it is an excellent probe of the dynamics of the water molecules that are solvating the azo moiety.[41] In addition, the line shape of the transition shows a distinct narrowing upon binding indicative of the sensitivity of this vibrational mode to its environment. Taken together, the interactions of this probe with several NAD-dependent enzymes and its ability to probe dynamics at the fs-ps time scale in 2D-IR experiments, suggest that azo-NAD+ is a promising new broad specificity probe of the active-site dynamics of NAD-dependent dehydrogenases and potentially other systems. Studies of the 2D IR spectroscopy of azo-NAD+, azo-NADP+ and a variety of enzymatic systems are underway to further demonstrate the applicability of this probe.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by NSF CHE-0644410 (CMC), and NIH R01 GM65368 and NSF CHE-0715448 (AK).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Finkelstein IJ, Zheng J, Ishikawa H, Kim S, Kwak K, Fayer MD. Probing dynamics of complex molecular systems with ultrafast 2D IR vibrational echo spectroscopy. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2007;9:1533–1549. doi: 10.1039/b618158a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boehr DD, McElheny D, Dyson HJ, Wright PE. The dynamic energy landscape of dihydrofolate reductase catalysis. Science. 2006;313:1638–1642. doi: 10.1126/science.1130258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nagel ZD, Klinman JP. Tunneling and dynamics in enzymatic hydride transfer. Chem. Rev. 2006;106:3095–3118. doi: 10.1021/cr050301x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kohen A. Kinetic isotope effects as probes for hydrogen tunneling, coupled motion and dynamics contributions to enzyme catalysis. Prog. React. Kinet. Mech. 2003;28:119–156. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kohen A. Current issues in enzymatic hydrogen transfer from carbon: tunneling and coupled motion from kinetic isotope effect studies. Hydrogen-Transfer React. 2007;4:1311–1340. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Henzler-Wildman KA, Lei M, Thai V, Kerns SJ, Karplus M, Kern D. A hierarchy of timescales in protein dynamics is linked to enzyme catalysis. Nature. 2007;450:913–916. doi: 10.1038/nature06407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Agarwal PK. Role of protein dynamics in reaction rate enhancement by enzymes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:15248–15256. doi: 10.1021/ja055251s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Klinmann JP, Kohen A. Hydrogen tunneling in biology. Chem. Biol. 1999:R191–R198. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(99)80058-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Antoniou D, Schwartz SD. Internal enzyme motions as a source of catalytic activity: rate-promoting vibrations and hydrogen tunneling. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2001;105:5553–5558. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schwartz SD. Vibrationally enhanced tunneling and kinetic isotope effects of enzymatic reactions. Isotope Effects in Chemistry and Biology. 2006:475–498. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kohen A, Klinman JP. Enzyme catalysis: beyond classical paradigms. Acc. Chem. Res. 1998;31:397–404. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cha Y, Murray CJ, Klinman JP. Hydrogen tunneling in enzyme reactions. Science. 1989;243:1325–1330. doi: 10.1126/science.2646716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Allemann RK, Evans RM, Loveridge EJ. Probing coupled motions in enzymatic hydrogen tunnelling reactions. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2009;037:349–353. doi: 10.1042/BST0370349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bialek W, Bruno WJ, Joseph J, Onuchic JN. Quantum and classical dynamics in biochemical reactions. Photosynth. Res. 1989;22:15–27. doi: 10.1007/BF00114763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bruno WJ, Bialek W. Vibrationally enhanced tunneling as a mechanism for enzymic hydrogen transfer. Biophys. J. 1992;63:689–699. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(92)81654-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zheng J, Kwak K, Fayer MD. Ultrafast 2D IR vibrational echo spectroscopy. Acc. Chem. Res. 2006;40:75–83. doi: 10.1021/ar068010d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim YS, Hochstrasser RM. Applications of 2D IR spectroscopy to peptides, proteins, and hydrogen-bond dynamics. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2009;113:8231–8251. doi: 10.1021/jp8113978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hunt NT. 2D-IR spectroscopy: ultrafast insights into biomolecule structure and function. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2009;38:1837–1848. doi: 10.1039/b819181f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Merchant KA, Thompson DE, Xu Q-H, Williams RB, Loring RF, Fayer MD. Myoglobin-CO conformational substate dynamics: 2D vibrational echoes and MD simulations. Biophys. J. 2002;82:3277–3288. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75669-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ishikawa H, Finkelstein IJ, Kim S, Kwak K, Chung JK, Wakasugi K, Massari AM, Fayer MD. Neuroglobin dynamics observed with ultrafast 2D-IR vibrational echo spectroscopy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2007;104:16116–16121. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707718104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Woys AM, Lin Y-S, Reddy AS, Xiong W, de Pablo JJ, Skinner JL, Zanni MT. 2D IR line shapes probe ovispirin peptide conformation and depth in lipid bilayers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:2832–2838. doi: 10.1021/ja9101776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mukherjee P, Kass I, Arkin IT, Zanni MT. Picosecond dynamics of a membrane protein revealed by 2D IR. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2006;103:3528–3533. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508833103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim YS, Liu L, Axelsen PH, Hochstrasser R. 2D-IR provides evidence for mobile water molecules in β–amyloid fibrils. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 2008;106:7220–7725. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909888106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fang C, Bauman JD, Das K, Remorino A, Arnold E, Hochstrasser RM. Two-dimensional infrared spectra reveal relaxation of the nonnucleoside inhibitor TMC278 complexed with HIV-1 reverse transcriptase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2008;105:1472–1477. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709320104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hill SE, Bandaria JN, Fox M, Vanderah E, Kohen A, Cheatum CM. Exploring the molecular origins of protein dynamics in the active site of human carbonic anhydrase II. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2009;113:11505–11510. doi: 10.1021/jp901321m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bandaria JN, Dutta S, Hill SE, Kohen A, Cheatum CM. Fast enzyme dynamics at the active site of formate dehydrogenase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;130:22–23. doi: 10.1021/ja077599o. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Blanchard JS, Cleland WW. Kinetic and chemical mechanisms of yeast formate dehydrogenase. Biochemistry. 1980;19:3543–3550. doi: 10.1021/bi00556a020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dolphin D, Poulson R, Avramovic O. Pyridine nucleotide coenzymes. coenzyme and cofactors. 1987;II [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sawanishi H, Tajima K, Tsuchiya T. Studies on diazepines. XXVIII. syntheses of 5H-1,3-diazepines and 2H-1,4-diazepines from 3-azidopyridines. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1987;35:4101–4109. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hixson SS, Hixson SH. Photochem. Photobiol. 1973;18:135–138. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1973.tb06403.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Turnbull WB, Daranas AH. On the Value of c: can low affinity Systems be studied by isothermal titration calorimetry? J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:14859–14866. doi: 10.1021/ja036166s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Landon LA, Harden W, Illy C, Deutscher SL. High-throughput fluorescence spectroscopic analysis of affinity of peptides displayed on bacteriophage. Anal. Biochem. 2004;331:60–67. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2004.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Popov VO, Lamzin VS. NAD(+)- dependent formate dehydrogenase. Biochem. J. 1994;301:625–643. doi: 10.1042/bj3010625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tishkov VI, Popov VO. Catalytic mechanism and application of formate dehydrogenase. Biochemistry. 2004;69:1252–1267. doi: 10.1007/s10541-005-0071-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pauly HE, Pfleiderer G. Conformational and functional aspects of the reversible dissociation and denaturation of glucose dehydrogenase. Biochemistry. 1977;16:4599–4604. doi: 10.1021/bi00640a011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Telegdi M, Wolfe DV, Wolfe RG. Malate Dehydrogenase. J. Biol. Chem. 1973;248:6484–6489. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mueggler PA, Wolfe RG. Malate dehydrogenase. Kinetic studies of substrate activation of supernatant enzyme by L-malate. Biochemistry. 1978;17:4615–20. doi: 10.1021/bi00615a006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Finkelstein IJ, Ishikawa H, Kim S, Massari AM, Fayer MD. Substrate binding and protein conformational dynamics measured by 2D-IR vibrational echo spectroscopy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2007;104:2637–2642. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610027104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ishikawa H, Kim S, Kwak K, Wakasugi K, Fayer MD. Disulfide bond influence on protein structural dynamics probed with 2D-IR vibrational echo spectroscopy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2007;104:19309–19314. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709760104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Naraharisetty SRG, Kurochkin DV, Rubtsov IV. C-D modes as structural reporters via dual-frequency 2DIR spectroscopy. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2007;437:262–266. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dutta S, Cook RJ, Kohen A, Cheatum CM. 2D-IR spectroscopy of azo- NAD+ in water. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. Submitted. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Horst S, Josef F, Hermann S, Maria-Regina K. Purification and properties of formaldehyde dehydrogenase and formate dehydrogenase from candida boidinii. Eur. J. Biochem. 1976;62:151–160. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1976.tb10108.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Aggeliki A, Dimitris P, Vladimir T, Vladimir P, Nikolaos EL. Structure-guided alteration of coenzyme specificity of formate dehydrogenase by saturation mutagenesis to enable efficient utilization of NADP. FEBS J. 2008;275:3859–3869. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2008.06533.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Keizo Y, Toshihiro N, Yasutaka M, Itaru U, Hirosuke O. Characterization of mutant glucose dehydrogenases with increasing stability. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1990;613:362–365. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1990.tb18179.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]