SUMMARY

Signaling cascades during adipogenesis culminate in the expression of two essential adipogenic factors, PPARγ and C/EBPα . Here we demonstrate that the IRE1α-XBP1 pathway, the most conserved branch of the unfolded protein response (UPR), is indispensable for adipogenesis. Indeed, XBP1-deficient mouse embryonic fibroblasts and 3T3-L1 cells with XBP1 or IRE1α knockdown exhibit profound defects in adipogenesis. Intriguingly, C/EBPβ, a key early adipogenic factor, induces Xbp1 expression by directly binding to its proximal promoter region. Subsequently, XBP1 binds to the promoter of Cebpa and activates its gene expression. The posttranscriptional splicing of Xbp1 mRNA by IRE1α is required as only the spliced form of XBP1 (XBP1s) rescues the adipogenic defect exhibited by XBP1-deficient cells. Taken together, our data show that the IRE1α-XBP1 pathway plays a key role in adipocyte differentiation by acting as a critical regulator of the morphological and functional transformations during adipogenesis.

Keywords: IRE1α, XBP1, UPR, adipogenesis, C/EBP

INTRODUCTION

Excess adipose tissue mass plays a central role in obesity-related complications such as cancer, cardiovascular diseases, insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. A comprehensive understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying adipocyte formation and development is of both fundamental and clinical relevance. Cellular models, such as 3T3-L1 and mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs), are invaluable in studying adipocyte differentiation or adipogenesis (Farmer, 2006). During adipogenesis, two transcription factors, CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein β (C/EBPβ) and C/EBPδ, are induced very early and play a crucial role in initiating the differentiation program by activating the expression of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ ) and C/EBPα , two key adipogenic transcription factors that positively regulate each other to promote and maintain the differentiated state (Farmer, 2006; Tontonoz and Spiegelman, 2008). Ectopic expression of either PPARγ or C/EBPα induces non-adipogenic fibroblasts to differentiate into adipocytes. Cells or adipose tissues with disruption in either gene exhibit severe defects in adipocyte differentiation or fat depot formation (Farmer, 2006; Tontonoz and Spiegelman, 2008).

Under the regulation of this complex transcriptional circuit, preadipocytes undergo dramatic transformations that ultimately lead to terminal adipogenic differentiation. However, it remains unclear how cells adapt to such dramatic morphological changes. Given their endocrine capacity and unique cellular structure, it has recently been hypothesized that adipocytes may display elevated UPR in an attempt to alleviate stress in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) caused by increased protein and lipid biosynthesis (Gregor and Hotamisligil, 2007). In yeast, upon ER stress, ER-resident transmembrane protein IRE1α oligomerizes and undergoes transautophosphorylation, leading to activation of its cytosolic endoribonuclease domain (Cox et al., 1993; Mori et al., 1993; Ron and Walter, 2007). Although phosphorylation of IRE1α has been used widely as an activation marker in experiments using ER stress inducers such as DTT or thapsigargin (Tg), recent studies in yeast suggest that the kinase activity may not be required for the endoribonuclease activity of IRE1α (Papa et al., 2003; Korennykh et al., 2009). However, the mechanism by which mammalian IRE1α is activated under physiological stress conditions remains largely unexplored.

Once activated, mammalian IRE1α splices 26 nucleotides from the Xbp1 mRNA, leading to a frameshift and the generation of an active b-ZIP transcription factor, XBP1s, that contains a C-terminal transactivation domain absent from the unspliced form XBP1u. XBP1s subsequently translocates to the nucleus and activates transcription of genes involved in protein folding and degradation to restore ER homeostasis (Ron and Walter, 2007). Studies in animal models have revealed that the IRE1α-XBP1 pathway is essential for the development and function of the liver and heart as well as professional secretory cells such as pancreatic exocrine and plasma cells (Masaki et al., 1999; Reimold et al., 2000; Reimold et al., 2001; Lee et al., 2005; Zhang et al., 2005). Recently, XBP1 has been shown to regulate hepatic lipogenesis via a UPR-independent manner (Lee et al., 2008a). However, its role in other cell types remains unclear.

Interestingly, XBP1 is highly expressed in embryonic adipose depots (Clauss et al., 1993) and white adipose cells (Kajimura et al., 2008). Moreover, XBP1−/− neonates rescued with hepatic XBP1s overexpression have no fat depot (Lee et al., 2005). These findings prompted us to hypothesize that XBP1 plays a role in adipocyte development. Indeed, our data demonstrate that XBP1 controls adipogenesis in part by transactivating the expression of a key adipogenic factor C/EBPα . In addition, our results suggest that adipogenic differentiation is associated with a low degree of UPR that is responsible for IRE1α activation and the subsequent splicing of Xbp1 mRNA. Intriguingly, IRE1α activity peaks during early adipogenesis and does not involve its hyperphosphorylation.

RESULTS

XBP1 is indispensable for adipogenesis

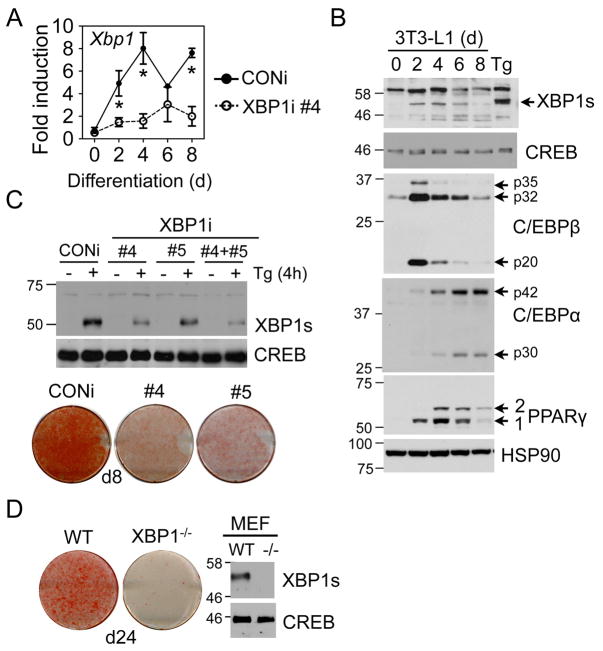

In 3T3-L1 differentiating adipocytes, Xbp1 mRNA increased significantly at day 2 (d2) and peaked around d4 (Fig. 1A). Consistently, XBP1s protein also peaked at d4 (Fig. 1B); this pattern strikingly resembles the induction of PPARγ and C/EBPα . To examine the role of XBP1 during adipogenesis, we transduced 3T3-L1 cells with control retroviruses (CONi) or with retroviruses encoding short hairpin RNAs against XBP1 (XBP1i). Lines #4 and #5 exhibited over 80 and 60% knockdown efficiency, respectively, as tested by immunoblots of cells treated with Tg (Fig. 1C top) and Q-PCR analysis of differentiating XBP1i cells (Fig. 1A). When these cells were cultured under adipogenic conditions, XBP1i-expressing cells demonstrated greatly attenuated differentiation, indicating an impaired adipogenic program (Fig. 1C bottom). Similar observations were obtained in XBP1−/− MEFs (Fig. 1D). Arguing against a non-specific effect provoked by short interference RNAs, 3T3-L1 cells expressing XBP1i that failed to effectively knockdown XBP1 (#1–2) exhibited no defects in adipogenesis (Fig. S1B). Taken together, XBP1 is essential for adipogenesis.

Figure 1.

XBP1 is essential for adipocyte differentiation. (A) Q-PCR analysis showing total Xbp1mRNA levels in 3T3-L1 CONi and XBP1i #4 during differentiation. Data normalized to d0 time-point of 3T3-L1 CONi cells. Data are means ± s.e.m. *, P<0.05 using unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test comparing CONi to XBP1i at the same time-point. (B) Immunoblots showing the levels of XBP1s and key adipogenic markers (C/EBPβ , C/EBPα , and PPARγ ) during adipogenesis. 3T3-L1 preadipocytes treated with 300 nM Tg for 4 h was loaded as a control. XBP1u (30kD) protein was not detectable. HSP90 and CREB, loading controls. (C) Top, Immunoblots of XBP1s protein in wildtype MEFs stably expressing CONi, XBP1i #4, #5 or both treated with 300 nM Tg for 4 h. CREB, a loading control. Bottom, Macroscopic pictures of Oil Red-O staining of 3T3-L1 cells expressing CONi, XBP1i #4 and #5 differentiated for 8 days (d8). (D) Left, macroscopic pictures of Oil Red-O staining of wildtype (WT) and XBP1−/− MEFs differentiated for 24 days (d24). Right, immunoblots of XBP1s protein in MEFs treated with 300 nM Tg for 4 h

C/EBPβ induces Xbp1 expression

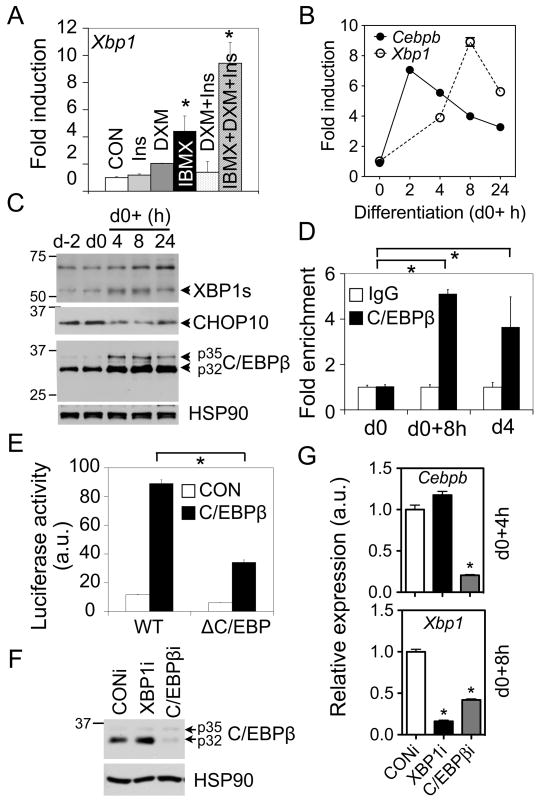

In light of a significant induction of Xbp1 mRNA during early differentiation, we next examined the mechanism underlying the transcriptional regulation of Xbp1. We first tested which component(s) of the adipogenic-inducing regimen was responsible for regulating Xbp1 induction. Only isobutylmethylxanthine (IBMX) or all three components of the regimen (IBMX, dexamethasone (DXM) and insulin) increased Xbp1 gene expression (Fig. 2A), suggesting that Xbp1 transcription is responsive to changes in cellular cAMP levels as IBMX is a phosphodiesterase inhibitor.

Figure 2.

C/EBPβ induces Xbp1 expression. (A) Q-PCR analysis of Xbp1 mRNA in 3T3-L1 cells (d0) treated with various stimuli as indicated for 8 h. Data normalized to the mock-treated sample (CON). (B) Q-PCR analysis showing the expression patterns of Xbp1 and Cebpb mRNA within the first 24 h postinduction in differentiating 3T3-L1 cells. (C) Immunoblot showing the expression patterns of XBP1s, CHOP10 and C/EBPβ proteins in differentiating 3T3-L1 cells. HSP90, a loading control. (D) ChIP analysis showing the recovery of Xbp1 promoter from immunoprecipitates of C/EBPβ or control IgG prepared from differentiated 3T3-L1 cells at d0, 8 h postinduction and d4. The amount of Xbp1 promoter (-580 to -425 bp) recovered was quantitated using Q-PCR. Data normalized to the IgG controls at each point. (E) Luciferase assay showing effects of C/EBPβ on wildtype (WT) or mutated Xbp1 reporter activity (−689 to +37 bp) in HEK293T cells transiently transfected with control GFP (CON) or C/EBPβ . ΔC/EBP, deletion of the C/EBP binding site (Fig. S2B). (F–G) Knockdown of C/EBPβ reduces Xbp1 level. Western blot (F) showing the protein level of C/EBPβ in 3T3-L1 stably expressing CONi or C/EBPβ i. Q-PCR analysis (G) of Cebpb and Xbp1 mRNA levels at 4 h or 8 h postinduction. Data are represented as mean ± s.e.m. *, P<0.05 using unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test comparing either the samples included by the brackets or that particular sample to the rest samples.

The ability of cAMP signals to activate C/EBPβ during adipogenesis (Cao et al., 1991; Farmer, 2006) prompted us to test whether C/EBPβ regulates Xbp1 expression. Indeed, total Xbp1 mRNA increased nearly 10-fold with a peak at 8 h postinduction within the first 24 h; this upregulation occurred subsequently to that of the Cebpb gene, which peaked at 2 h postinduction (Fig. 2B). Consistently, XBP1s protein levels also peaked at 8 h postinduction (Fig. 2C).

Supporting the scenario that C/EBPβ directly regulates Xbp1 expression, recent genome-wide analysis identified putative C/EBP binding sites on the Xbp1 promoter (Lefterova et al., 2008). Indeed, sequence analysis of mammalian Xbp1 proximal promoter revealed the presence of a highly conserved C/EBP binding element (Osada et al., 1996) centered at −482 bp relative to transcription start site (Fig. S2A). Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) experiments showed enrichment of C/EBPβ proteins on the Xbp1 proximal promoter at 8 h postinduction and on d4 (Fig. 2D). Further confirming the specificity of the C/EBPβ antisera, no signal was detected at the 3’ UTR region of Xbp1 (not shown). In addition, overexpression of C/EBPβ in HEK293T cells activated a Xbp1 promoter (−689 to +37 bp)-luciferase reporter (Fig. 2E). This activation was significantly attenuated over 50% by deleting the putative binding element (Fig. S2B and 2E).

To further confirm the effect of C/EBPβ on Xbp1 induction, we generated 3T3-L1 cells stably expressing C/EBPβ shRNA with over 80% knockdown efficacy (Fig. 2F-G). Loss of C/EBPβ significantly blocked differentiation as expected (Fig. S2C). Indeed, Xbp1 mRNA levels were reduced by nearly 60% in differentiating C/EBPβ i 3T3-L1 cells compared to CONi cells at 8 h postinduction (Fig. 2G). Taken together, our data strongly suggest that the Xbp1 gene is a bona fide direct target of C/EBPβ during adipogenesis.

Adipogenesis is associated with a low measure of UPR

IRE1α is the predominant form of IRE1 in adipocytes (not shown) and throughout adipogenesis, its mRNA expression level did not vary significantly (Fig. S3A). During UPR, IRE1α splices Xbp1 mRNA to generate XBP1s, a potent transcription factor (Ron and Walter, 2007). Phosphorylation of IRE1α and Xbp1 mRNA splicing are two common markers of UPR activation that can be assessed by the mobility shift of IRE1α protein on an SDS-PAGE gel and by the ratio of the spliced Xbp1s mRNA to total Xbp1 mRNA using RT-PCR analysis, respectively.

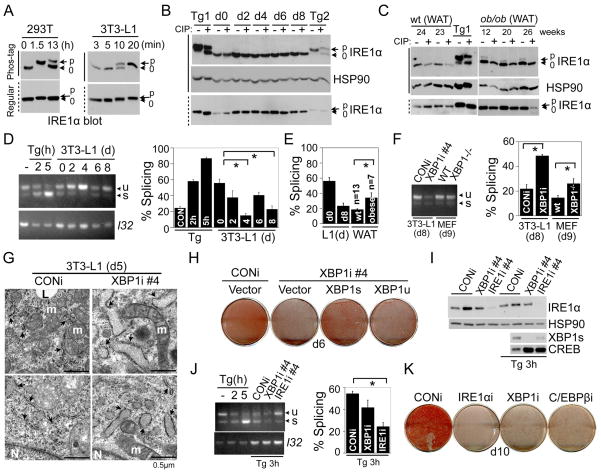

To increase the resolution of the phosphorylated forms of a protein on a SDS-PAGE, we incorporated Phos-tag and Mn2+ in regular SDS-PAGE gels (Kinoshita et al., 2006). Dramatically, in HEK293T cells, nearly 100% of IRE1α proteins were hyperphosphorylated upon a 1.5 h-treatment with Tg and only ~30% after 13 h (Fig. 3A). Interestingly, in all the conditions and samples tested, IRE1α exhibited one predominant band shift which was reversible by phosphatase (CIP) treatment (Fig. 3B), suggesting that transautophosphorylation of mammalian IRE1α may not be as extensive as predicted for the yeast counterpart (Korennykh et al., 2009).

Figure 3.

Adipogenesis is associated with a low level of physiological UPR. (A) Western blot showing mobility shift of IRE1α using Phos-tag or regular SDS-PAGE gels in (left) HEK293T and (right) 3T3-L1 cells treated with 300 nM Tg for indicated period of time. “p” and “0”, hyper-and non-phosphorylated IRE1α , respectively. Solid and dotted lines on the left hand side, Phos-tag and regular gels, respectively. (B) Immunoblot showing separation of p-IREα from IRE1α using regular and Phos-tag gels with or without CIP treatment (1 h) in differentiating 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Two positive controls: Tg1, HEK293T cells treated 300nM Tg for 1.5 h; Tg 2, 3T3-L1 cells treated 300nM Tg for 4 h. HSP90, a loading control. (C) Western blot showing mobility shift of IRE1α in white adipose tissues (WAT) collected from wildtype lean and ob/ob animals using Phos-tag with or without CIP treatment. The age of the mice (in weeks) shown. (D-F) RT-PCR analysis of Xbp1 splicing (Xbp1u and s) in (D) differentiating 3T3-L1 adipocytes, (E) WAT of wildtype lean (wt) and obese animals, and (F) differentiating 3T3-L1 and MEFs with XBP1 deficiency at d8 and d9, respectively. Samples treated with Tg for 2 or 5 h were used as controls. L32, a loading control. (G) Electron microscopic images of differentiated 3T3-L1 CONi or XBP1i adipocytes at d5. Each image taken from a different cell. Arrows, ER; m, mitochondrion; N, nucleus; L, lipid droplets. Scale bar shown at the right corner of each panel. (H) Macroscopic images of differentiation of 3T3-L1 expressing CONi or XBP1i plus pBabe-vector, XBP1s or XBP1u. Oil Red-O staining was carried out on d6. (I-K) Knockdown of IRE1α reduces Xbp1 splicing and attenuates differentiation. Western blot analysis (I) showing the IRE1α and XBP1s protein levels in XBP1i and IRE1α i #4 3T3-L1 cells. Nuclear-extracts were used for blots showing the levels of XBP1s in cells treated with 300nM Tg for 3 h. HSP90 and CREB, loading controls. (J) RT-PCR analysis of Xbp1 splicing (Xbp1u and s) in 3T3-L1 cells treated with Tg for 3 h and quantitated as above. (K) Macroscopic images of differentiation of 3T3-L1 expressing CONi, XBP1i, C/EBPβ i or IRE1α i#4. Oil Red-O staining was carried out on d10. For RT-PCR analysis of Xbp1 splicing, quantification was done using the NIH ImageJ software where band densities was calculated and subtracted from the background. Data are represented as mean ± s.e.m. of data from at least three experiments *, P<0.05 using unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test comparing the samples included by the brackets.

Surprisingly, we failed to observe a mobility shift of IRE1α at any time-point during differentiation (Fig. 3B). Arguing against the possibility that IRE1α in 3T3-L1 cells can not be phosphorylated, Tg treatment for as little as 20 min induced a dramatic mobility shift of nearly 100% of IRE1α proteins (Fig. 3A). Consistently, the majority of IRE1α in both white and brown adipose tissues (WAT and BAT) of wildtype lean animals at 23–27 weeks of age were not phosphorylated (Fig. 3C and S3B). In contrast, IRE1α phosphorylation was readily detectable in the liver from the same set of mice (Fig. S3B).

Next, we quantitated the percent of Xbp1 splicing using RT-PCR as a direct measure of IRE1α RNase activity. Unexpectedly, Xbp1 mRNA splicing peaked at d0 (mean ± SEM; 55.9 ± 4.9%) and reached nadir at d4 (15.1 ± 2.4%) (Fig. 3D and S3C). Supporting the physiological relevance of our cell model, the level of Xbp1 mRNA splicing on d8 of 3T3-L1 adipocytes was very similar to that of adipose tissues from wildtype lean mice (23.1 ± 4.1% vs. 18.3 ± 1.3%, Fig. 3E). As a positive control, Xbp1 mRNA splicing reached approximately 50% in pancreas of lean wildtype animals [(Iwawaki et al., 2004) and not shown]. Given that d0 adipocytes and pancreas exhibit similar levels of Xbp1 mRNA splicing, we conclude that physiological UPR is activated during early adipogenesis.

Obesity is postulated to cause ER stress or UPR in adipose tissues. However, the nature and the extent of UPR in adipose tissues of obese animals remain unclear. To this end, we examined IRE1α phosphorylation and Xbp1 splicing in mice that were either genetically- or dietary- induced to become obese (ob/ob and HFD). Unexpectedly, ~15% of IRE1α proteins were phosphorylated in WAT of these animals (Fig. 3C and not shown). Correspondingly, the splicing of Xbp1 in WAT was increased from 18.3 ±1.3% in lean mice to 33.9 ± 6.8% in obese animals (Fig. 3E and S3D). Thus, our data supports the notion that a low measure of UPR is associated with obesity.

During differentiation, XBP1s protein levels were inversely correlated with Xbp1s mRNA levels (Fig. 1C vs. 3D and 2C vs. S3C). We reasoned that XBP1 may function to maintain UPR in adipocytes at a low level via feedback inhibition on UPR and IRE1α activity. To directly test this possibility, we measured Xbp1 mRNA splicing in XBP1-deficient cells and wildtype cells. Indeed, Xbp1 mRNA splicing was increased over two-fold in XBP1i vs. CONi adipocytes on d8 (48.6 ± 1.1% vs. 21.9 ± 3.3%, Fig. 3F). Similar observations were obtained in XBP1−/−differentiating MEF adipocytes (26.1 ± 3.9% vs. 14.6 ± 1.8%, Fig. 3F). Surprisingly, the majority of IRE1α was not hyperphosphorylated in XBP1-deficient adipocytes (Fig. S3E).

As UPR is intimately linked to ER morphology and function (Ron and Walter, 2007), we examined the fine structure of the ER using transmission electron microscopy (TEM). Unlike the packed ER cisternae characteristic of professional secretory cells (Harding et al., 2001; Lee et al., 2005), the ER of adipocytes (d5) have few loosely dispersed cisternae with discernible ribosomes (Fig. 3G) as shown previously (Novikoff et al., 1980). By contrast, most of the ER in the XBP1i cells were fragmented and somewhat dilated compared to those in control adipocytes (Fig. 3G and S3I). Thus, our data suggest that XBP1 functions to maintain ER homeostasis in adipocytes; hence loss of XBP1 in adipocytes disrupts ER function and activates IRE1α .

To determine if the IRE1α-mediated splicing event is critical for differentiation, we transduced 3T3-L1 XBP1i cells with retroviruses encoding the pBabe vector, XBP1u or XBP1s (Fig. S3F). Only ectopic expression of XBP1s almost completely rescued the differentiation defect of 3T3-L1 XBP1i cells (Fig. 3H). Further supporting the role of XBP1s in adipogenesis, XBP1s protein levels were much higher than XBP1u in differentiated 3T3-L1 cells at d6 (Fig. S3G). Thus, Xbp1 mRNA splicing by IRE1α RNase activity is required for adipogenesis.

To directly test the consequences of IRE1α deficiency in adipogenesis, we generated 3T3-L1 cells stably expressing IRE1α shRNA (IRE1α i). One shRNA (#4) reduced IRE1α protein levels to less than 10% of controls (Fig. 3I). Supporting a key role of IRE1α in mediating Xbp1 splicing, knockdown of IRE1α significantly reduced Xbp1 splicing (54.4 ± 2.2% CONi, 41.7 ± 6.7% XBP1i vs. 24.3 ± 3.6% IRE1α i, Fig. 3J) and XBP1s production in cells treated with Tg for 3 h (Fig. 3I). Cells stably expressing IRE1α i#4 failed to undergo differentiation to a similar degree as XBP1i or C/EBPβ i cells (Fig. 3K); cells expressing shRNA (#2) with no knockdown effect exhibited normal differentiation (Fig. S3H). Thus, our data indicate that adipogenic conversion is associated with UPR and the IRE1α-XBP1 branch is indispensable for adipogenesis.

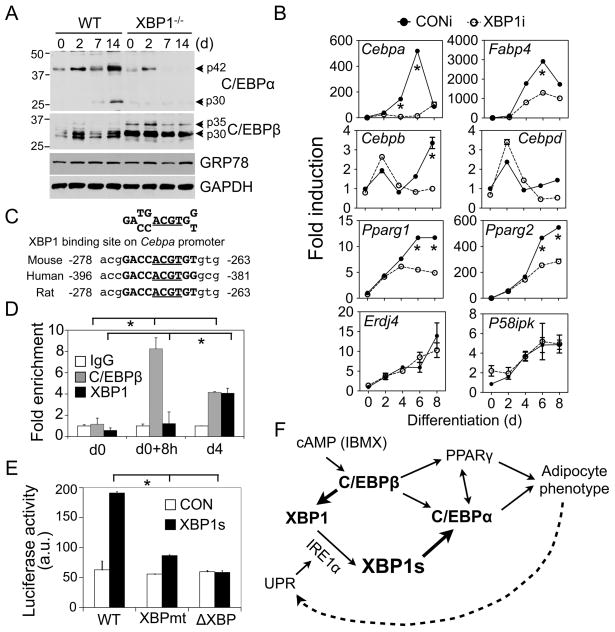

XBP1 directly regulates C/EBPα expression

We speculated that XBP1 may regulate the expression of an important adipogenic factor. Indeed, C/EBPα protein levels were significantly decreased in differentiating XBP1−/− MEFs while C/EBPβ levels remained largely unaffected (Fig. 4A). Similar observations were obtained in 3T3-L1 adipocytes (Fig. S4A). Furthermore, Cebpa mRNA levels on both d4 and d6 were significantly reduced by over 90% in 3T3-L1 XBP1i cells compared to CONi cells whereas both Pparg1 and 2 mRNA levels were reduced by approximately 50% only on d6 (Fig. 4B). Supporting the notion that XBP1 targets are cell-type specific (Lee et al., 2005; Acosta-Alvear et al., 2007), expression of some known XBP1 targets Erdj4 and p58IPK (Lee et al., 2003) was not affected in XBP1i adipocytes (Fig. 4B).

Figure 4.

XBP1 controls Cebpa expression. (A) Western blot analysis of C/EBPα and C/EBPβ protein levels in XBP1−/− and wildtype MEFs. GRP78 and GAPDH, loading controls. (B) Q-PCR analysis in differentiating 3T3-L1 expressing CONi and XBP1i #4. Data normalized to d0 time-point of 3T3-L1 CONi adipocytes. (C) Conservation of XBP1 binding sites on the Cebpa promoter. The core binding element ACGT is underlined. (D) ChIP analysis showing the recovery of Cebpa promoter from immunoprecipitates of C/EBPβ , XBP1 or control IgG prepared from 3T3-L1 cells at d0, 8 h postinduction and d4 as indicated. The amount of Cebpa promoter (−335 to −82 bp) recovered was quantitated using Q-PCR. Data normalized to the IgG controls at each point. (E) Luciferase assay showing effects of XBP1s on Cebpa reporter activity (−320 to +45 bp) in HEK293T cells transiently transfected with control GFP (CON) and XBP1s. The Cebpa reporter constructs with either mutation (XBPmt) or deletion (ΔXBP) of the XBP1 binding sites were included. Data represented as mean ± s.e.m.. *, P<0.05 using unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test comparing the samples included by the brackets. (F) Model showing the role of IRE1α-XBP1 in adipogenesis. The new findings described in this paper are highlighted in bold. See text for details.

XBP1 preferentially binds to CRE-like sequences containing an ACGT core (Clauss et al., 1996; Acosta-Alvear et al., 2007). Considering that the Cebpa proximal promoter region contains a highly conserved putative XBP1 binding element centered at −270 bp (Fig. 4C), we tested the role of XBP1 in modulating Cebpa expression in adipocytes. Pointing to a direct regulatory role for XBP1 in vivo, XBP1 was enriched on the Cebpa promoter on d4 (Fig. 4D); this binding was comparable to that of C/EBPβ on d4 and was completely abolished in XBP1i 3T3-L1 cells (Fig. 4D and S4B). Demonstrating the specificity of the antibody, the XBP1 antibody is highly specific for both XBP1s and XBP1u proteins in immunoprecipitation (Fig. S4D).

In further support of the notion that XBP1 transactivates Cebpa expression, XBP1s overexpression increased Cebpa promoter activity in luciferase reporter assays in XBP1−/− MEFs and HEK293T cells whereas XBP1u had no effect (Fig. S4E). The activity of XBP1s on the Cebpa promoter was comparable to that on the promoter of a known target gene Edem1 (Fig. S4E); this activation was largely abolished by either mutation or deletion of the XBP1 binding element on the Cebpa promoter (Fig. S4C and 4E). In a rescue experiment, C/EBPα overexpression readily rescued the differentiation defects observed in XBP1i cells (Fig. S4F), suggesting that adipogenic attenuation in these cells may be in part due to the reduction in C/EBPα levels. Taken together, our data demonstrates that Cebpa is a bona fide target of XBP1s in adipocytes.

DISCUSSION

Adipocytes are specialized cell types that integrate lipid metabolism with protein synthesis in a very compact cellular space. Here we show that the IRE1α-XBP1 pathway, the most conserved branch of the UPR, is indispensable for the cellular transformation into adipocytes (Fig. 4F). Investigation of the underlying mechanism uncovered a number of discoveries about the function of the IRE1α-XBP1 branch in adipogenesis that increased our understanding of this pathway in adipocytes.

First, we show that adipogenesis is associated with a low level of UPR – termed as “physiological” UPR. IRE1α activity peaks during early adipogenesis with nearly 55% of Xbp1 mRNA being spliced. Subsequently, splicing is reduced to 10–20% in mature adipocytes. Indeed, the splicing in fully differentiated adipocytes in our culture system is equivalent to that in mature adipocytes from wildtype lean mice. Upon induction of obesity, there is approximately a 2-fold increase in Xbp1 mRNA splicing with only a minor fraction of the IRE1α proteins being hyperphosphorylated. In support of our observations, UPR activation was detected mainly in the pancreas and skeletal muscles in a UPR-reporter transgenic mouse model with ~50% and 26% Xbp1 mRNA splicing, respectively; no UPR was detected in any other organs including adipose tissues (Iwawaki et al., 2004). Thus, we conclude that UPR is activated at an early stage of adipogenesis and maintained at a relatively low physiological level in mature adipocytes. Moreover, obesity is associated with elevated UPR, but the level of UPR activation incurred in adipose tissues is not as high as anticipated.

Second, we show that the majority of IRE1α proteins are not hyperphosphorylated during adipogenesis even as Xbp1 mRNA splicing approaches 55% on d0 of adipocyte differentiation. We speculate that hyperphosphorylation may not be required for activation of IRE1α RNase activity under physiological UPR. Indeed, although several structural studies have implicated the importance of dimerization and transautophosphorylation of IRE1α in activation of its RNase activity (Zhou et al., 2006; Lee et al., 2008b), an earlier study showed that the kinase-defective IRE1α K599A mutant has intact RNase activity (Tirasophon et al., 2000). Furthermore, a recent structural study on the cytosolic domain of yeast IRE1α (Korennykh et al., 2009) suggests that transautophosphorylation of IRE1α is not required for its RNase activation. As our data show that IRE1α RNase activity is dynamically regulated during adipogenesis, some intriguing questions arise: Is IRE1α activated by misfolded proteins during adipogenesis? How is IRE1α RNase activity affected by transautophosphorylation during this process? Does oligomerization of IRE1α proteins and formation of IRE1α foci occur under physiological UPR in mammals as shown in drug-treated yeast? Many detailed biochemical studies are required before we can fully appreciate the mechanisms of mammalian IRE1α activation under physiological conditions.

Third, we show that C/EBPβ regulates Xbp1 expression, which in turn modulates the expression of a key adipogenic factor C/EBPα. Cells or animals lacking XBP1 have profound defects in adipogenesis and adipose development [this study and (Lee et al., 2005)], similar to the phenotypes of C/EBPα-deficient cells or adipose tissues (Farmer, 2006; Tontonoz and Spiegelman, 2008). As PPARγ and C/EBPα are critical for the induction and maintenance of each other, further studies are required to determine whether regulation of Cebpa by XBP1 and PPARγ occurs independently or in concert. Additionally, generation of adipose-specific IRE1α or XBP1 null animals will elucidate the role of UPR in the pathogenesis of obesity and insulin resistance.

Fourth, we show that the IRE1α-XBP1 pathway of the UPR is important for adipogenic differentiation. In light of the observations made in this study, it is interesting to compare the roles of XBP1 in governing adipogenesis with that of myogenesis or plasma cell differentiation. In myogenic differentiation, two key myogenic factors, MyoD and myogenin, transactivate Xbp1 expression (Blais et al., 2005), which in turn transactivates Mist1, a negative regulator of MyoD, leading to decreased differentiation (Acosta-Alvear et al., 2007). During early B cell differentiation, IRF4 and Blimp-1 regulate Xbp1 expression (Shaffer et al., 2004; Klein et al., 2006), which in turn induces the expression of IL-6, a key growth factor for driving B cell differentiation (Iwakoshi et al., 2003). Thus, these results suggest that the IRE1α-XBP1 pathway may act as a critical regulatory component of diverse cellular differentiation events. Further studies of the activation of the different UPR components during adipocyte differentiation and their mechanisms of action will clarify how pre-adipocytes undergo their amazing transformation into adipocytes and provide insights into the nature of physiological UPR.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cells

3T3-L1 preadipocytes, XBP1−/− and wildtype control MEFs (gifts from Laurie Glimcher, Harvard Medical School), HEK293T and phoenix cells were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS (Hyclone). Tg (EMD Calbiochem) was used at 300 nM.

Retroviral transduction and stable cell line generation

Phoenix cells were transfected with the plasmids encoding the gene of interest in pSuper or pBabe vectors and VSVG at 2:1 ratio for 16 h and then replaced with fresh culture media. Following 48 h culture, media containing retroviruses were harvested and used to transduce target cells in the presence of 5 μg/ml polybrene (Sigma) for 24 h. Stable cell lines were selected in the presence of 2 μg/ml puromycin (Sigma) or 500 μg/ml G418 (EMD Calbiochem) and then used for differentiation. Typically, puromycin-resistant cell lines developed in 6 days whereas G418 resistant cell lines were generated in 12 days. In rescue experiments, 3T3-L1 cells transduced with two retroviruses were selected with both puromycin and G418. To minimize the batch-to-batch difference, we only compared cells made from the same batch of cells.

shRNA knockdown

Two vectors were used in this study: pSuper/retro (H1 promoter, a gift from Lee Kraus, Cornell University) and pSuper/U6/retro (U6 promoter, described in the Supplemental Procedures). XBP1i and IRE1α i were driven by the U6 promoter while the C/EBPβ i was driven by the H1 promoter. Control RNAi were against the firefly luciferase or the GFP gene. Target sequences are shown in Supplementary Table 2.

Mice and tissues

Wildtype and ob/ob mice on C57BL/6 background were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory. The epididymal WAT, BAT and liver were harvested from (a) wildtype mice fed with either 60% HFD (Research Diets Inc.) or 10% chow diet for over 13 weeks; (b) the ob/ob mice at the age of 12–26 week old. Tissues were harvested immediately following cervical dislocation, snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80° C (Qi et al., 2009). All animal procedures were approved by the Cornell IACUC.

Plasmids and viruses

XBP1u and XBP1s cDNAs, cloned from the mouse WAT cDNA library using pfu polymerase (Stratagene) were subcloned into pcDNA3/Flag or 3x HA vectors. Retroviral encoding XBP1u and Flag-XBP1s were cloned by shuttling XBP1 cDNA into the pBabe-puro vector. For retroviral transduction in the 3T3-L1 experiments, cDNAs encoding the mouse C/EBPβ and rat C/EBPα were cloned into the pBabe-puro vector using standard PCR reactions. Promoter regions of mouse Xbp1 (−689 to +37 bp), Edem (−336 to +15 bp) and Cebpa (−320 to +45 bp) were cloned via PCR of tail genomic DNA of C57BL/6 mice and ligated into the pGL3-basic luciferase reporter construct (Promega). Constructs generated by PCR were sequenced by the Cornell DNA sequencing facility.

Adipogensis

(a) 3T3-L1: Two days post-confluency (d0), cells were treated for 48 h with 0.25 mM IBMX, 1 μM DXM (EMD Calbiochem) and 1 μg/ml insulin (Sigma). Afterwards, cells were fed every 48 h with 1 μg/ml insulin in culture media until d8 post confluence. (b) MEF: Cells were differentiated as 3T3-L1 with the following modifications: when the cells became confluent (d0), they were treated with 0.25 mM IBMX, 5 μM DXM, 10 μg/ml insulin and 5 μM troglitazone (EMD Calbiochem) for the first 48 h. Subsequently, cells were maintained in 1 μg/ml insulin and 5 μM troglitazone to induce terminal differentiation.

Oil Red-O staining

Cells were fixed with 10% formaldehyde in PBS for 15 min at room temperature and stained with freshly-prepared Oil Red-O working solution for 30 min followed by three washes with water. Plates were scanned using an Epson scanner. Oil Red-O working solution was prepared by mixing 6 ml of 0.5% Oil Red-O (Sigma) in isopropanol with 4 ml of ddH2O followed by filtration through a Whatman #1 filter paper (Millipore).

Western blot

Western blot was performed using 15–30 μg of total cell lysates or 10 μg of nuclear extracts. Antibodies used in this study: C/EBPβ (mouse, 1:1000, Biolegend); GRP78 (goat, 1:1,000), C/EBPα (rabbit, 1:2,000), PPARγ (mouse, 1:400), XBP1 (rabbit, 1:1,000), and HSP90 (rabbit, 1:5,000) from Santa Cruz; IRE1α (rabbit, 1:1,000, Cell Signaling); GAPDH (rabbit, 1:10,000, Novus Biologicals). Secondary antibodies, goat anti-rabbit IgG, anti-mouse IgG (Biorad), and donkey anti-goat IgG HRP (Jackson ImmunoResearch), were used at 1:10,000. The p-Ser724 IRE1α antibody from Novus Biologicals did not work in our hand.

Phos-tag gels

Phos-tag gel was carried out the same way as regular Western blots, except that:(a) 5% SDS-PAGE containing 50 μM Phos-tag (NARD Institute) and 50 μM MnCl2 (Sigma) were used; (b) gels were soaked in 1 mM EDTA for 10 min prior to transfer onto a PVDF membrane.

RNA extraction and Q-PCR

Total RNA was extracted using Trizol per supplier’s protocol (Molecular Research Center) and reverse transcribed using Superscript III kit (Invitrogen). cDNA were analyzed using the Power SYBR Green PCR kit on the ABI PRISM 7900HT Q-PCR machine (Applied Biosystems) or the SYBR Green PCR system (gifts from Jeff Pleiss, Cornell University) on the iQ5 or Cfx384 Q-PCR machine (Bio-Rad). All Q-PCR data were normalized to ribosomal l32 gene.

RT-PCR for Xbp1 splicing

PCR primers were designed to encompass the splicing sequences of mouse Xbp1 (Supplementary Table 1). PCR products, amplified with annealing temperature at 58° C for 30 cycles, were separated by electrophoresis on a 2.5% agarose gel (Invitrogen). Quantitation of percent of splicing, defined as the ratio of Xbp1s level to total Xbp1 (Xbp1u + Xbp1s) levels, was carried out using the NIH ImageJ software.

Statistical analysis

Results are expressed as mean ± s.e.m. Comparisons between groups were made by unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test. P<0.05 was considered as statistically significant. All experiments were repeated at least three times and representative data are shown.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. L. Glimcher, L. Kraus and J. Pleiss for reagents; Drs. K. L. Guan, S. Lee, M. Montminy and three anonymous reviewers for insightful comments and suggestions. The Qi laboratory is supported by the Cornell start-up package and grants from AFAR (RAG08061), ADA (7-08-JF-47) and NIH (R01DK082582). L. Q. is the recipient of the 2008 Rosalinde and Arthur Foundation/American Federation for Aging Research New Investigator Award in Alzheimer’s Diseases and the American Diabetes Association (ADA) Junior Faculty Award. The study was funded by the Cornell start-up package and an ADA grant (7-08-JF-47).

References

- Acosta-Alvear D, Zhou Y, Blais A, Tsikitis M, Lents NH, Arias C, Lennon CJ, Kluger Y, Dynlacht BD. XBP1 controls diverse cell type- and condition-specific transcriptional regulatory networks. Mol Cell. 2007;27:53–66. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blais A, Tsikitis M, Acosta-Alvear D, Sharan R, Kluger Y, Dynlacht BD. An initial blueprint for myogenic differentiation. Genes Dev. 2005;19:553–569. doi: 10.1101/gad.1281105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Z, Umek RM, McKnight SL. Regulated expression of three C/EBP isoforms during adipose conversion of 3T3-L1 cells. Genes Dev. 1991;5:1538–1552. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.9.1538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clauss IM, Chu M, Zhao JL, Glimcher LH. The basic domain/leucine zipper protein hXBP-1 preferentially binds to and transactivates CRE-like sequences containing an ACGT core. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:1855–1864. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.10.1855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clauss IM, Gravallese EM, Darling JM, Shapiro F, Glimcher MJ, Glimcher LH. In situ hybridization studies suggest a role for the basic region-leucine zipper protein hXBP-1 in exocrine gland and skeletal development during mouse embryogenesis. Dev Dyn. 1993;197:146–156. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001970207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox JS, Shamu CE, Walter P. Transcriptional induction of genes encoding endoplasmic reticulum resident proteins requires a transmembrane protein kinase. Cell. 1993;73:1197–1206. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90648-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farmer SR. Transcriptional control of adipocyte formation. Cell Metab. 2006;4:263–273. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregor MF, Hotamisligil GS. Thematic review series: Adipocyte Biology. Adipocyte stress: the endoplasmic reticulum and metabolic disease. J Lipid Res. 2007;48:1905–1914. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R700007-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding HP, Zeng H, Zhang Y, Jungries R, Chung P, Plesken H, Sabatini DD, Ron D. Diabetes mellitus and exocrine pancreatic dysfunction in perk−/− mice reveals a role for translational control in secretory cell survival. Mol Cell. 2001;7:1153–1163. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00264-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwakoshi NN, Lee AH, Vallabhajosyula P, Otipoby KL, Rajewsky K, Glimcher LH. Plasma cell differentiation and the unfolded protein response intersect at the transcription factor XBP-1. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:321–329. doi: 10.1038/ni907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwawaki T, Akai R, Kohno K, Miura M. A transgenic mouse model for monitoring endoplasmic reticulum stress. Nat Med. 2004;10:98–102. doi: 10.1038/nm970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kajimura S, Seale P, Tomaru T, Erdjument-Bromage H, Cooper MP, Ruas JL, Chin S, Tempst P, Lazar MA, Spiegelman BM. Regulation of the brown and white fat gene programs through a PRDM16/CtBP transcriptional complex. Genes Dev. 2008;22:1397–1409. doi: 10.1101/gad.1666108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinoshita E, Kinoshita-Kikuta E, Takiyama K, Koike T. Phosphate-binding tag, a new tool to visualize phosphorylated proteins. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2006;5:749–757. doi: 10.1074/mcp.T500024-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein U, Casola S, Cattoretti G, Shen Q, Lia M, Mo T, Ludwig T, Rajewsky K, Dalla-Favera R. Transcription factor IRF4 controls plasma cell differentiation and class-switch recombination. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:773–782. doi: 10.1038/ni1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korennykh AV, Egea PF, Korostelev AA, Finer-Moore J, Zhang C, Shokat KM, Stroud RM, Walter P. The unfolded protein response signals through high-order assembly of Ire1. Nature. 2009;457:687–693. doi: 10.1038/nature07661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee AH, Chu GC, Iwakoshi NN, Glimcher LH. XBP-1 is required for biogenesis of cellular secretory machinery of exocrine glands. EMBO J. 2005;24:4368–4380. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee AH, Iwakoshi NN, Glimcher LH. XBP-1 regulates a subset of endoplasmic reticulum resident chaperone genes in the unfolded protein response. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:7448–7459. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.21.7448-7459.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee AH, Scapa EF, Cohen DE, Glimcher LH. Regulation of hepatic lipogenesis by the transcription factor XBP1. Science. 2008a;320:1492–1496. doi: 10.1126/science.1158042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee KP, Dey M, Neculai D, Cao C, Dever TE, Sicheri F. Structure of the dual enzyme Ire1 reveals the basis for catalysis and regulation in nonconventional RNA splicing. Cell. 2008b;132:89–100. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.10.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefterova MI, Zhang Y, Steger DJ, Schupp M, Schug J, Cristancho A, Feng D, Zhuo D, Stoeckert CJ, Jr, Liu XS, et al. PPAR{gamma} and C/EBP factors orchestrate adipocyte biology via adjacent binding on a genome-wide scale. Genes Dev. 2008;22:2941–2952. doi: 10.1101/gad.1709008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masaki T, Yoshida M, Noguchi S. Targeted disruption of CRE-binding factor TREB5 gene leads to cellular necrosis in cardiac myocytes at the embryonic stage. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;261:350–356. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.0972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori K, Ma W, Gething MJ, Sambrook J. A transmembrane protein with a cdc2+/CDC28-related kinase activity is required for signaling from the ER to the nucleus. Cell. 1993;74:743–756. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90521-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novikoff AB, Novikoff PM, Rosen OM, Rubin CS. Organelle relationships in cultured 3T3-L1 preadipocytes. J Cell Biol. 1980;87:180–196. doi: 10.1083/jcb.87.1.180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osada S, Yamamoto H, Nishihara T, Imagawa M. DNA binding specificity of the CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein transcription factor family. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:3891–3896. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.7.3891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papa FR, Zhang C, Shokat K, Walter P. Bypassing a kinase activity with an ATP-competitive drug. Science. 2003;302:1533–1537. doi: 10.1126/science.1090031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi L, Saberi M, Zmuda E, Wang Y, Altarejos J, Zhang X, Dentin R, Hedrick S, Bandyopadhyay G, Hai T, et al. Adipocyte CREB promotes insulin resistance in obesity. Cell Metab. 2009;9:277–286. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2009.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reimold AM, Etkin A, Clauss I, Perkins A, Friend DS, Zhang J, Horton HF, Scott A, Orkin SH, Byrne MC, et al. An essential role in liver development for transcription factor XBP-1. Genes Dev. 2000;14:152–157. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reimold AM, Iwakoshi NN, Manis J, Vallabhajosyula P, Szomolanyi-Tsuda E, Gravallese EM, Friend D, Grusby MJ, Alt F, Glimcher LH. Plasma cell differentiation requires the transcription factor XBP-1. Nature. 2001;412:300–307. doi: 10.1038/35085509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ron D, Walter P. Signal integration in the endoplasmic reticulum unfolded protein response. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:519–529. doi: 10.1038/nrm2199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer AL, Shapiro-Shelef M, Iwakoshi NN, Lee AH, Qian SB, Zhao H, Yu X, Yang L, Tan BK, Rosenwald A, et al. XBP1, downstream of Blimp-1, expands the secretory apparatus and other organelles, and increases protein synthesis in plasma cell differentiation. Immunity. 2004;21:81–93. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tirasophon W, Lee K, Callaghan B, Welihinda A, Kaufman RJ. The endoribonuclease activity of mammalian IRE1 autoregulates its mRNA and is required for the unfolded protein response. Genes Dev. 2000;14:2725–2736. doi: 10.1101/gad.839400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tontonoz P, Spiegelman BM. Fat and beyond: the diverse biology of PPARgamma. Annu Rev Biochem. 2008;77:289–312. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.77.061307.091829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang K, Wong HN, Song B, Miller CN, Scheuner D, Kaufman RJ. The unfolded protein response sensor IRE1alpha is required at 2 distinct steps in B cell lymphopoiesis. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:268–281. doi: 10.1172/JCI21848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J, Liu CY, Back SH, Clark RL, Peisach D, Xu Z, Kaufman RJ. The crystal structure of human IRE1 luminal domain reveals a conserved dimerization interface required for activation of the unfolded protein response. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:14343–14348. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606480103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.