Abstract

The corticotropin-releasing factor receptor type 2a (CRF2(a)R) belongs to the family of G protein-coupled receptors. The receptor possesses an N-terminal pseudo signal peptide that is unable to mediate targeting of the nascent chain to the endoplasmic reticulum membrane during early receptor biogenesis. The pseudo signal peptide remains uncleaved and consequently forms an additional hydrophobic receptor domain with unknown function that is unique within the large G protein-coupled receptor protein family. Here, we have analyzed the functional significance of this domain in comparison with the conventional signal peptide of the homologous corticotropin-releasing factor receptor type 1 (CRF1R). We show that the presence of the pseudo signal peptide leads to a very low cell surface receptor expression of the CRF2(a)R in comparison with the CRF1R. Moreover, whereas the presence of the pseudo signal peptide did not affect coupling to the Gs protein, Gi-mediated inhibition of adenylyl cyclase activity was abolished. The properties mediated by the pseudo signal peptide were entirely transferable to the CRF1R in signal peptide exchange experiments. Taken together, our results show that signal peptides do not only influence early protein biogenesis. In the case of the corticotropin-releasing factor receptor subtypes, the use of conventional and pseudo signal peptides have an unexpected influence on signal transduction.

Keywords: G Protein-coupled Receptors (GPCR), G Proteins, Protein Processing, Protein Targeting, Signal Peptidase, Signal Transduction, Corticotropin-releasing Factor Receptor

Introduction

The family of corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF)3 receptors encompasses two subtypes, the CRF1R and CRF2R (1, 2). The CRF1R is expressed mainly in the anterior pituitary and plays a central role in the regulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal stress axis in mammals (3). It binds CRF with high affinity and mediates ACTH release from the pituitary leading to cortisol biosynthesis in the adrenal cortex. A large body of evidence points to a major role of the receptor in mediating CRF effects in anxiety and depressive disorders (4–6).

In the case of the CRF2R, three splice variants have been described as follows: the CRF2(a)R, CRF2(b)R, and CRF2(c)R. All splice variants bind CRF with low affinity and the urocortins 1–3 with high affinity. They are involved in the regulation of feeding behavior (7) and in recovery from a stress response (8). It is likely that they are also involved in modulating anxiety-related behavior.

Both the CRF1R and the CRF2(a)R usually couple to the Gs/adenylyl cyclase system and consequently increase cytosolic cAMP as a second messenger. However, a promiscuous coupling behavior was described previously in particular for the CRF1R involving also G proteins of the Gi, Go, and Gq families (9–11). In the case of the CRF1R, coupling to Gs at low agonist occupancy and to Gi at high occupancy leads to a typical bell-shaped concentration-response curve in cAMP accumulation assays (12).

The CRF receptors belong to the small group of GPCRs (5–10%) possessing putative N-terminal signal peptides that are cleaved off after mediating the ER targeting/insertion process (13, 14). The majority (90–95%) of the GPCRs do not possess cleavable signal peptides. Here, one of the transmembrane helices of the mature receptors (usually TM1) mediates ER targeting/insertion as an uncleaved signal anchor sequence (13). The reason why some membrane proteins, including GPCRs, require additional signal peptides, whereas others do not, is not completely understood.

An initial function of a signal sequence (cleaved signal peptide or uncleaved signal anchor sequence) is to mediate targeting of the nascent chain to the translocon complex of the ER by binding the signal recognition particle. Moreover, the signal sequence opens the Sec61 protein-conducting channel to integrate the nascent chain into the bilayer. In the case of the CRF1R and the glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor, it was shown by deletion mutants that a cleavable signal peptide is indeed necessary for efficient receptor biosynthesis at the ER membrane (15, 16). However, additional functions were described for other GPCRs. In the case of the endothelin B receptor, the signal peptide facilitated N tail translocation across the ER membrane (17). The CRF(2a)R, in contrast, possesses an uncleaved pseudo signal peptide that is unable to mediate ER targeting/insertion, remains uncleaved at the extracellular mature N tail of the receptor, and thus forms an additional hydrophobic domain (18). Conventional signal peptide functions are blocked in the pseudo signal peptide by a single amino acid residue (Asn13), and conversion to a conventional cleaved signal peptide is achieved by mutation of this residue (18). To date, the pseudo signal peptide of the CRF2(a)R is a unique extracellular domain in the GPCR protein family. One function of the pseudo signal peptide may be to increase the portion of correctly folded receptors in the early secretory pathway (18). Here, we have assessed its functions in comparison with the conventional signal peptide of the homologous CRF1R. We show that the presence of the pseudo signal peptide leads to a very low receptor expression. Moreover, although the presence of the pseudo signal peptide did not affect coupling to the Gs protein, Gi coupling of the CRF2(a)R was impaired.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

The cDNA encoding the rat CRF1R and CRF2(a)R was a gift from U. B. Kaupp (IBI Forschungszentrum Jülich, Germany). [3H]cAMP was purchased from PerkinElmer Life Sciences. The peptidic ligand sauvagine was synthesized in our laboratory (10). LipofectamineTM 2000 and the vector pSecTag2A were purchased from Invitrogen. The transfection reagent FuGENETM 6 was from Roche Diagnostics. Polyethyleneimine (PEI) was from Polysciences Europe GmbH (Eppelheim, Germany). The monoclonal mouse anti-CRF1R antibody was from LifeSpan Bioscience (Seattle, WA). The phycoerythrin-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG was from Jackson ImmunoResearch (West Grove, PA). The polyclonal rabbit anti-calnexin antibody was from StressGen (Ann Arbor, MI). The alkaline phosphatase-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG and alkaline phosphatase-conjugated anti-mouse IgG were from Dianova (Hamburg, Germany). The polyclonal rabbit anti-biotin antibody, DyLight 800-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG and DyLight 680-conjugated anti-mouse IgG were from Biomol (Hamburg, Germany). The polyclonal rabbit anti-GFP antiserum 02 was raised against a glutathione S-transferase/GFP fusion protein in our group, and specificity was verified.4 The monoclonal mouse anti-GFP antibody and the TALON metal affinity resin were from BD Biosciences. DNA-modifying enzymes, PNGaseF and EndoH, were from New England Biolabs (Frankfurt am Main, Germany). Oligonucleotides were from Biotez (Berlin, Germany). Vector plasmid pEGFP-N1 (encoding the enhanced variant of GFP) and the monoclonal anti-GFP antibody were from Clontech. The Roti-Load sample buffer was from Carl Roth (Karlsruhe, Germany). All other reagents were from Sigma. Data of the cAMP RIA were analyzed using the program RadLig Software 6.0 (Cambridge, UK) and GraphPad Prism version 3.02 (GraphPad Software, San Diego).

DNA Manipulations

Standard DNA manipulations were carried out according to the handbooks of Sambrook and Russel (19). The nucleotide sequences of the plasmid constructs were verified using the FS dye terminator kit from PerkinElmer Life Sciences. Site-directed mutagenesis was carried out with the QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit from Stratagene (Heidelberg, Germany).

Plasmid Constructs

The constructs used in this study are schematically shown in Fig. 1 (details of the cloning procedures on request).

FIGURE 1.

A, sequence of the uncleaved pseudo signal peptide (SP) of the CRF2(a)R (left) and the conventional cleaved signal peptide of the CRF1R (right). Residue Asn13 of the CRF2(a)R preventing conventional signal peptide functions (18) is depicted in boldface. B, schematic representation of the constructs used in this study. Upper panel, full-length receptor constructs. The signal peptides (SP) and the transmembrane domains (roman numerals) of the CRF2(a)R constructs (black) and the CRF1R constructs (gray) are indicated by boxes. The latin numbers above each construct indicate the number of receptor amino acid residues present (without signal peptide). The latin numbers below each construct indicate the number of amino acids forming the signal peptide. Lower panel, marker protein fusions: N tail sequences fused to GFP are indicated. The latin number above each construct indicate the number of N tail amino acid residues present (without signal peptide). The latin numbers below each construct indicate the number of amino acids forming the signal peptide. H, His tag.

Marker Protein Fusions

Constructs CRF2(a).NT and CRF1.NT represent GFP fusions to the N tails of the CRF2(a)R (position Ala121) and the CRF1R (position Ala119), respectively, in the vector pSecTag2A. In construct SP1-CRF2(a).NT, the pseudo signal peptide of the CRF2(a)R was replaced by the conventional signal peptide of the CRF1R. Conversely, in construct SP2-CRF1.NT, the signal peptide of the CRF1R was replaced by the pseudo signal peptide of the CRF2(a)R. In construct pN13A-CRF2(a), residue Asn13 of the CRF2(a).NT construct was replaced by an alanine residue to convert the pseudo signal peptide into a conventional, cleaved signal peptide (18). In all marker protein fusion constructs, an additional C-terminal His6 sequence was added to allow their purification.

Full-length Receptor Constructs

Plasmids pCRF2(a)R and pCRF1R encode the full-length CRF2(a)R and CRF1R in the vector plasmid pEGFP-N1. The receptors were C-terminally tagged with a GFP moiety at position Val411 (CRF2(a)R) and Thr413 (CRF1R) thereby deleting the stop codons. Plasmids pΔSP-CRF2(a)R and pΔSP-CRF1R encode the corresponding signal peptide deletion mutants. Plasmids pSP1-CRF2(a)R and pSP2-CRF1R encode the corresponding signal peptide swap mutants. In construct pN13A-CRF2(a)R, the pseudo signal peptide of the CRF2(a)R was converted to a conventional signal peptide (see above).

Cell Culture and Transfection

Cells were cultured at 37 °C and 5% CO2. Human embryonic kidney cells (HEK 293 cells) and mouse anterior pituitary tumor cells (AtT-20 cells) were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) containing 10% (v/v) fetal calf serum (FCS), penicillin (100 units/ml), and streptomycin (100 μg/ml). Transfection of the cells with LipofectamineTM 2000 and PEI was carried out according to the supplier's recommendations.

Confocal Laser-scanning Microscopy, Colocalization of Constructs with Plasma Membrane Marker Trypan Blue

1.5 × 105 HEK 293 cells grown for 24 h in a 35-mm diameter dish containing a poly-l-lysine-coated coverslip were transfected with 0.8 μg of plasmid DNA and PEI according to the supplier's recommendations. Cells were incubated overnight, washed once with PBS, and transferred immediately into a self-made chamber (details on request). Cells were covered with 1 ml of PBS (137 mm NaCl, 2.7 mm KCl, 4.3 mm Na2HPO4, 1.47 mm KH2PO4, pH 7.4), and trypan blue was added to a final concentration of 0.05%. After 1 min of staining, GFP and trypan blue fluorescence signals were visualized at room temperature on a Zeiss LSM510-META inverted confocal laser-scanning microscope (objective lens, ×100/1.3 oil; optical section, <0.8 μm; multitrack mode; GFP, λexc, 488 nm, argon laser; BP filter, 500–530 nm; trypan blue; λexc, 543 nm HeNe laser; LP filter, 560 nm). The overlay of both signals was computed using the Zeiss LSM510 acquisition software (release 3.2 SP2). Images were imported into Photoshop software (Adobe Systems Inc.), and contrast was adjusted to approximate the original image. The overlay of the signals was computed, and the images were processed as described previously above.

Quantification of Plasma Membrane GFP Fluorescence Intensities by Automated Microscopy

For quantification of the plasma membrane fluorescence signals of the receptor, 7 × 104 HEK 293 cells were grown for 24 h on 24-well microtiter plates and transfected with PEI according to the supplier's recommendations. Cells were incubated overnight, and the cell culture medium was removed, and the nuclei of the cells were stained for 30 min with 1 μm Hoechst-33342 diluted in medium. The staining solution was removed, and the plasma membranes were stained for 1 min with 0.1% (w/v) trypan blue diluted in PBS. After staining, plates were transferred to a Cellomics Array Scan VTI automated microscope and analyzed using the Array Scan VTI software (version 5.6.1.3, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Hoechst-33342 and trypan blue fluorescence signals were used to define nuclei and plasma membrane masks, respectively. Intracellular masks were defined as the difference between plasma membrane and nuclei masks. For each well, colocalization of the GFP fluorescence signals of the receptor with the plasma membrane and intracellular masks was measured for 1 × 103 transfected cells using the Array Scan VTI software. In addition to automated microscopy, plasma membrane expression of the receptor constructs was also quantified by conventional cell surface biotinylation assays as described previously (20).

Quantification of Plasma Membrane GFP Fluorescence Intensities by Confocal LSM Microscopy or Flow Cytometry Measurements

Plasma membrane GFP fluorescence signals of individual transiently transfected HEK 293 cells were quantified by confocal LSM microscopy as described previously (15). Briefly, the GFP fluorescence signals were colocalized with the plasma membrane marker trypan blue, and their intensity was quantified using an 8-bit grayscale and the Zeiss LSM510 acquisition software (release 3.2 SP2). Quantification of the plasma membrane GFP fluorescence signals was carried out with at least 20 cells. For the flow cytometry measurements, 1 × 106 stably transfected HEK 293 cells were grown on 12-well plates for 48 h. Cells were washed twice with PBS. Cells were transferred in PBS into a flow cytometry tube and incubated with a monoclonal mouse anti-CRF1R antibody (1:400, 30 min, 4 °C) directed against the N tail of the receptor. Cells were washed three times with PBS and incubated with phycoerythrin-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (1:100, 30 min, 4 °C). Cell surface fluorescence signals of 104 cells were analyzed using a FACSCanto II apparatus (BD Biosciences) and analyzed with FCS Express software (De Novo Software, Los Angeles). Nontransfected HEK 293 cells were used in the measurements to subtract the fluorescence background.

Quantitative Detection of Secreted GFP Marker Protein Fusions

Secreted GFP marker proteins from transiently transfected HEK 293 cells were analyzed by SDS-PAGE immunoblotting and fluorimetric measurements as described previously (15). Briefly, proteins were isolated from the cell culture medium via their His tag using TALON metal affinity resin beads. Proteins were quantified either by measuring their GFP signals fluorimetrically (λexc = 488 nm, λem = 507 nm) or by SDS-PAGE immunoblotting using a monoclonal anti-GFP antibody (1:4,000) and alkaline phosphatase-conjugated anti-mouse IgG 1:1,500).

Immunoprecipitation of GFP-tagged Full-length Receptor Constructs; Treatment with PNGaseF and/or EndoH; Detection of Coimmunoprecipitated Calnexin

The previously described immunoprecipitation procedure was used (18). Briefly, receptors were precipitated from transiently transfected HEK 293 cells using the rabbit anti-GFP antiserum 02. Optional treatment of the precipitated receptors with EndoH or PNGaseF was carried out according to the supplier's recommendations. Receptors were detected by SDS-PAGE immunoblotting using a monoclonal anti-GFP antibody (1:4,000) and alkaline phosphatase-conjugated anti-mouse IgG (1:1,500). Coprecipitated calnexin was detected using a polyclonal anti-calnexin antibody (1:1,000) and alkaline phosphatase-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (1:1,000).

Cell Surface Biotinylation Assay

Cell surface proteins were labeled with sulfo-NHS-biotin as described previously (15). Total receptors were precipitated using the rabbit anti-GFP antiserum 02 as described above. Receptors were deglycosylated with PNGaseF according to the supplier's recommendations and analyzed by SDS-PAGE immunoblotting using a polyclonal rabbit anti-biotin antibody (1:5,000, cell surface receptors) and a monoclonal mouse anti-GFP antibody (1:4,000, total receptors) on the same blot. Following incubation with secondary antibodies (DyLight 800-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG and DyLight 680-conjugated anti-mouse IgG; 1:10,000 each), immunoreactive protein bands were detected using the OdysseyTM infrared imaging system and the application software 2.1 (Li-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE).

cAMP Accumulation Assay

Activation of the full-length receptor constructs was monitored by measuring sauvagine-mediated cAMP accumulation as described previously (cAMP RIA) (21).

RESULTS

The Presence of the Pseudo Signal Peptide of the CRF2(a)R Leads to a Very Low Receptor Expression at the Plasma Membrane

We have previously shown that the CRF2(a)R possesses an uncleaved N-terminal pseudo signal peptide, whereas the CRF1R contains a conventional signal peptide (Fig. 1A) (18). Here, we have assessed in a comparative study the influence of these signal peptides on the plasma membrane expression of the different CRF receptor subtypes.

For this study, we used the C-terminally GFP-tagged CRF2(a)R and CRF1R and also constructed signal peptide swap mutants (Fig. 1B); the conventional signal peptide of the CRF1R was replaced by the pseudo signal peptide of the CRF2(a)R (construct SP2-CRF1R, Fig. 1B), and conversely, the signal peptide of the CRF2(a)R was replaced by that of the CRF1R (construct SP1-CRF2(a)R, Fig. 1B). In addition, the N13A mutant of the CRF2(a)R was used (construct N13A-CRF2(a)R, Fig. 1B). This point mutation converts the pseudo signal peptide into a conventional and cleaved signal peptide (18).

We first studied whether the properties of the different signals are preserved following the signal swap. To this end, marker protein fusions were constructed (Fig. 1B). The N tails of the above constructs were fused with a His-tagged GFP (Fig. 1B; constructs CRF2(a).NT, CRF1.NT, SP1-CRF2(a).NT, SP2-CRF1.NT, and N13A-CRF2(a).NT). These constructs do not contain transmembrane domains, and if a conventional signal peptide is present, it directs the soluble GFP marker via the signal recognition particle/translocon pathway to the ER and subsequently, following cleavage, via the secretory pathway to the cell culture medium (18). The pseudo signal peptide instead fails to target the GFP moiety to the ER; the signal peptide remains uncleaved, and the construct is located in the cytosol and in the nucleus (18) (nonmembrane-bound GFP is able to enter the nucleus, see Ref. 22).

HEK 293 cells were transiently transfected with the constructs, and the GFP fluorescence signals were localized by LSM. In the case of CRF2(a).NT, SP2-CRF1.NT, and the unfused GFP control protein, the signals were detected diffusely throughout the cell, including the nucleus demonstrating that these fusions were not targeted to the ER membrane (Fig. 2A). In contrast, in the case of CRF1R.NT, SP1-CRF2(a)R.NT, and the mutant N13A-CRF2(a).NT, reticular signals were detected demonstrating that these fusions were able to enter the ER (Fig. 2A; the validity of this LSM assay has been confirmed previously, see Ref. 18). The reticular signals also colocalized almost completely with the ER stain Rhodamine 6G (data not shown). Consistent with these results, only the constructs CRF1R.NT, SP1-CRF2(a)R.NT, and N13A-CRF2(a).NT could be purified via their His tag from cell culture supernatants and be detected by fluorimetric measurements or by immunoblotting (Fig. 2B). Taken together, these results show again that the CRF2(a)R possesses a pseudo signal peptide failing to mediate ER targeting (18). It could be converted to a conventional signal peptide by the N13A mutation as described previously (18). In contrast, the CRF1R possesses a conventional signal peptide that is able to mediate ER association and to direct the GFP moiety to the supernatant as a consequence of its cleavage. Importantly, signal peptide functions could be swapped; construct SP1-CRF2(a).NT behaves like CRF1R.NT in these experiments and construct SP2-CRF1.NT like CRF2(a).NT.

FIGURE 2.

The pseudo signal peptide of the CRF2(a) R maintains its properties in signal peptide exchange experiments. A, localization of the GFP fluorescence signals of the constructs CRF2(a).NT, CRF1.NT, SP1-CRF2(a).NT, SP2-CRF1.NT, and N13A-CRF2(a).NT in transiently transfected HEK 293 cells by confocal LSM. The soluble nonfused GFP protein was used as a control. The horizontal (xy) scans are representative of four independent experiments. Scale bar, 10 μm. n = nucleus. B, analysis of the secretion of the marker protein fusions. Nontransfected cells were used as a control (−). Upper panel, GFP fluorescence measurements. Constructs were purified from the cell culture supernatants of 1.2 × 106 cells, and the GFP fluorescence signals were measured fluorimetrically. Columns represent mean values of three independent experiments each performed in triplicate (S.D.). Lower panel, detection of the purified constructs by immunoblotting using a monoclonal anti-GFP antibody and alkaline phosphatase-conjugated anti-mouse IgG. In each lane, the isolated protein of 2 × 106 cells was loaded. The immunoblot is representative of three independent experiments.

To assess for signal peptide cleavage in the case of the full-length receptors, constructs CRF2(a)R, CRF1R, SP2-CRF1R, SP1-CRF2(a)R, and N13A-CRF2(a)R (see above) were immunoprecipitated from transiently transfected HEK 293 cells, and the apparent molecular masses of the deglycosylated constructs were compared with their corresponding signal peptide mutants ΔSP-CRF1R (Fig. 1B) and ΔSP-CRF2(a)R (Fig. 1B) by immunoblotting. If the signal peptide is cleaved off, constructs should comigrate with the corresponding signal peptide mutants, and if not, the apparent molecular mass should be increased by 2 kDa corresponding to signal peptide size. As expected, constructs CRF2(a)R and SP2-CRF1R indeed possess an uncleaved signal peptide in these experiments, whereas constructs CRF1R, SP1-CRF2(a)R, and N13A-CRF2(a)R possess a cleavable signal peptide (Fig. 3).

FIGURE 3.

Analysis of signal peptide cleavage of the full-length constructs CRF2(a)R, CRF1R, SP2-CRF1R, SP1-CRF2(a)R, N13A-CRF2(a)R, and the signal peptide deletion mutants ΔSP-CRF2(a)R and ΔSP-CRF1. Receptors were precipitated from transiently transfected HEK 293 cells using an anti-GFP antiserum, digested with PNGaseF to remove all N-glycosylations, and detected by SDS-PAGE immunoblotting using a monoclonal anti-GFP antibody. Nontransfected cells were used as a control for antibody specificity (−). Each lane shows the receptors from 2.5 × 106 cells. The immunoblot is representative of three independent experiments.

Comparison of the amount of precipitated receptors in Fig. 3 indicates that the CRF2(a)R is expressed in substantially lower amounts than the CRF1R. This lower expression seems to be solely due to the presence of the pseudo signal peptide because construct SP2-CRF1R also shows a low expression, whereas construct SP1-CRF2(a)R is conversely up-regulated. This up-regulation is also seen when the pseudo signal peptide is converted to a conventional signal peptide (construct N13A-CRF2(a)R).

The deglycosylated, immunoprecipitated receptors shown in Fig. 3 represent a mixture of cell surface and intracellular receptors. To assess the influence of the different signal sequences on the number of mature cell surface receptors, the GFP fluorescence signals of the full-length receptor constructs were localized in transiently transfected HEK 293 cells by confocal LSM (Fig. 4A, left panel, in green). The cell surface of the same cells was visualized by the use of trypan blue (Fig. 4A, center panel, in red), and colocalization is indicated in yellow (Fig. 4A, right panel). A high plasma membrane expression was observed for constructs CRF1R and SP1-CRF2(a)R, a substantially lower plasma membrane expression for constructs CRF2(a)R and SP2-CRF1R. Colocalization of the GFP fluorescence signals with trypan blue was also quantified using automated microscopy (Fig. 4B). Expression of the CRF2(a)R at the plasma membrane was 25% that of the CRF1R in these experiments. In the case of construct SP2-CRF1R, the presence at the plasma membrane was reduced to 26% of the CRF1R wild type level. Conversely, the amount of SP1-CRF2(a)R was up-regulated to 115% that of the CRF1R.

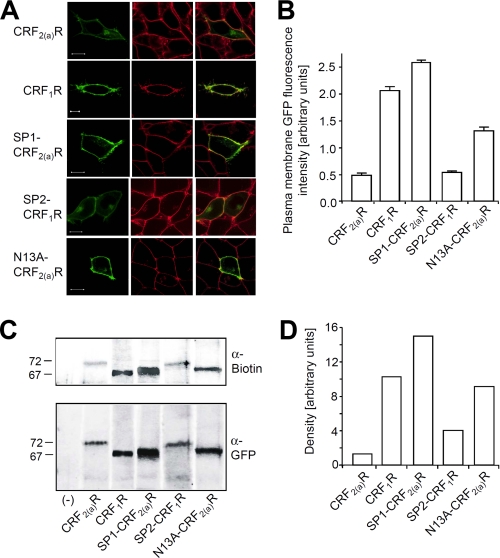

FIGURE 4.

The presence of the pseudo signal peptide strongly decreases cell surface receptor expression in transiently transfected HEK 293 cells. A, colocalization of the GFP signals of constructs CRF2(a)R, CRF1R, SP2-CRF1R, SP1-CRF2(a)R, and N13A-CRF2(a)R with the plasma membrane marker trypan blue in live cells by LSM. The GFP signals of the receptor are shown in green (left panels), and trypan blue signals of the cell surface of the same cells are shown in red (center panels). GFP and trypan blue fluorescence signals were computer-overlaid (right panels; overlap is indicated by yellow). The scans show representative cells. Scale bar, 10 μm. Similar data were obtained in three independent experiments. B, quantification of the plasma membrane GFP fluorescence signals of the receptor by automated microscopy. The columns represent mean values of three independent experiments (± S.D.) in arbitrary units. In the individual experiments, the plasma membrane GFP fluorescence intensity of at least 400 cells was analyzed for each construct. C, cell surface biotinylation assay. After labeling of the cell surface receptors with biotin, total receptors were precipitated using an anti-GFP antiserum. Receptors were deglycosylated with PNGaseF to remove all N-glycosylations and detected by SDS-PAGE immunoblotting using a monoclonal anti-biotin antibody (upper part, cell surface receptors) and a monoclonal anti-GFP antibody (lower part; total receptors). Nontransfected cells were used as a control for antibody specificity (−). Each lane shows the receptors from 3.75 × 106 cells. Each immunoblot is representative of three independent experiments. D, densitometric quantification of the protein bands detected by the anti-biotin antibody in C (cell surface receptors).

To verify these results, cell surface biotinylation assays were carried out (Fig. 4, C and D). After labeling of the cell surface receptors with biotin, total receptors were precipitated using an anti-GFP antiserum. Receptors were deglycosylated with PNGaseF and detected by SDS-PAGE immunoblotting using an anti-biotin antibody (cell surface receptors) or by an anti-GFP antibody (total receptors) on the same blot. A similar decrease in cell surface receptor expression was observed for the constructs containing the pseudo signal peptide confirming the above results. Taken together, these results show that the presence of the pseudo signal peptide causes a very low expression of the CRF2(a)R in the plasma membrane. This property could be transferred to the CRF1R by signal peptide exchange.

We next examined the mechanism of the pseudo signal peptide-mediated decrease in receptor expression. One likely possibility was that the presence of the pseudo signal peptide reduces folding efficiency. Misfolded receptors may be recognized by the quality control system (QCS) of the early secretory pathway and retained intracellularly. A decreased folding efficiency and QCS recognition should be accompanied by an increase in the amount of immature, high mannose, and nonglycosylated receptor forms.

To assess for this possibility, the full-length receptor constructs were immunoprecipitated from transiently transfected HEK 293 cells, detected by immunoblotting (Fig. 5A), and the amount of complex high mannose-glycosylated and nonglycosylated receptor forms was determined by densitometric measurements (Fig. 5B). The identity of the three receptor bands was verified by EndoH and PNGaseF treatments (Fig. 5C) (18). In the case of constructs CRF1R and SP1-CRF2(a)R, the majority of the receptors were present in the mature complex glycosylated form (56 and 57% respectively), and the portion of immature receptors was low. In the case of constructs CRF2(a)R and SP2-CRF1R, in contrast, the bulk of the receptor proteins was detectable in their immature (high mannose and nonglycosylated forms) forms (69 and 67%, respectively). Consistently, more intracellular GFP fluorescence signals were detectable for constructs CRF2(a)R and SP2-CRF1R (see also Fig. 4A above), and these intracellular signals colocalized with the ER marker stain Rhodamine 6G (data not shown).

FIGURE 5.

The pseudo signal peptide increases the amount of immature protein present in the early secretory pathway in transiently transfected HEK 293 cells. A, analysis of the glycosylation state of constructs CRF2(a)R, CRF1R, SP2-CRF1R, and SP1-CRF2(a)R. Receptors were precipitated using a polyclonal anti-GFP antiserum and detected by SDS-PAGE immunoblotting using a monoclonal anti-GFP antibody. Nontransfected cells were used as a control (−). In each lane the same amount of immunoreactive receptor protein was loaded. For each receptor construct, three immunoreactive protein bands are detectable representing the following glycosylation states: mature complex-glycosylated forms (*), immature high mannose forms (§), and immature nonglycosylated forms (#) (see below). The immunoblot is representative of three independent experiments. B, ratio of the individual immunoreactive protein bands for each construct. Intensity of the protein bands was measured densitometrically, and the relative amount was calculated for each construct. Columns represent mean values (± S.D.) of protein band intensity of three independent experiments. C, verification of the identity of the three protein bands for the constructs CRF2(a)R and CRF1R (see also Ref. 18). The receptors were precipitated from transiently transfected HEK 293 cells using a polyclonal anti-GFP antiserum. Samples were treated with EndoH or PNGaseF or left untreated (−). In each lane, the same amount of immunoreactive receptor protein was loaded. Immunoreactive proteins were detected by SDS-PAGE immunoblotting using a monoclonal anti-GFP antibody. Nonglycosylated receptors are EndoH- and PNGaseF-resistant (#); high mannose forms are EndoH- and PNGaseF-sensitive (§); complex-glycosylated receptors are EndoH-resistant and PNGaseF-sensitive (*). The immunoblot is representative of three independent experiments.

In the case of glycoproteins, a decreased folding efficiency was usually accompanied by a stronger association with the lectin chaperones calnexin and/or calreticulin. To address this question, coprecipitated calnexin was detected in the receptor precipitation samples described above. Immunoreactive calnexin protein bands were detected in the case of constructs CRF2(a)R and SP2-CRF1R, but not in the case of constructs CRF1R and SP1-CRF2(a)R when identical amounts of immunoreactive, deglycosylated receptor protein were loaded (Fig. 6).

FIGURE 6.

The presence of the pseudo signal peptide leads to an increased association of the receptors with the lectin chaperone calnexin. Upper panel, detection of coprecipitated calnexin. Constructs CRF2(a)R, CRF1R, SP2-CRF1R, and SP1-CRF2(a)R were precipitated from transiently transfected HEK 293 cells. Coprecipitated calnexin was detected by SDS-PAGE immunoblotting using a polyclonal anti-calnexin antibody. In each lane, the same amount of immunoreactive receptor protein was loaded to allow comparison of the coprecipitated calnexin. Center panel, loading control. Receptors were detected in the above samples using a monoclonal anti-GFP antibody. All receptors were treated with PNGaseF to remove N-glycosylations allowing comparison of single protein bands. Lower panel, detection of calnexin in total cell lysates using a monoclonal anti-calnexin antibody. In each lane, lysates of 1.25 × 105 cells was loaded. All immunoblots are representative of three independent experiments.

Taken together, these results show that the presence of the pseudo signal peptide decreases folding efficiency of the CRF2(a)R in comparison with the CRF1R. Moreover, this property could be transferred by signal peptide exchange.

The Presence of the Pseudo Signal Peptide of the CRF2(a)R Prevents Gi-mediated Inhibition of Adenylyl Cyclase Activity

We have previously shown that the pseudo signal peptide of the CRF2(a)R does not influence the affinity of the receptor for the CRF receptor selective agonist urocortin I and the CRF2(a)R-specific agonist urocortin II (18). To address the question of whether the presence of the pseudo signal peptide affects receptor activation and second messenger formation, HEK 293 cells transiently transfected with the full-length receptor constructs were treated with the CRF receptor agonist sauvagine, and cAMP formation was measured by radioimmunoassays (cAMP RIA) (Fig. 7A).

FIGURE 7.

The presence of the pseudo signal peptide prevents Gi-mediated inhibition of adenylyl cyclase activity. A, adenylyl cyclase activity assay using transiently transfected HEK 293 cells expressing constructs CRF2(a)R, CRF1R, SP2-CRF1R, and SP1-CRF2(a)R. Intact cells were stimulated with increasing concentrations of the agonist sauvagine, and a cAMP RIA was performed. Data points represent geometric mean values of three independent experiments, each performed in triplicate. The calculated EC50 values are (95% confidence limits) as follows: CRF2(a)R, 0.12 nm (0.10–0.13); CRF1R (ascending slope), 0.23 nm (0.13–0.41); SP2-CRF1R, 0.27 nm (0.15–0.49); SP1-CRF2(a)R (ascending slope), 0.16 nm (0.15–0.17). B, adenylyl cyclase activity assay using AtT-20 pituitary cells expressing the CRF1R endogenously. The experiment was carried out as described previously in A. Data points represent geometric mean values of three independent experiments, each performed in triplicate. The calculated EC50 value is (95% confidence limits; ascending slope) 6.1 nm (4.3–8.6).

Consistent with previous results from other groups (10, 11), a bell-shaped concentration-response curve was recorded for the CRF1R. This unusual curve results from the fact that the receptor couples to Gs at low agonist occupancy but also to Gi at high occupancy (10, 11). Coupling to Gi was confirmed by blunting the concentration-response curve by pertussis toxin pretreatment (data not shown). In the case of the CRF2(a)R, in contrast, a monophasic concentration-response curve was observed suggesting that the CRF2(a)R is unable to activate Gi. Strikingly, the ability/inability to couple to Gi could be transferred by signal peptide exchange; in the case of construct SP1-CRF2(a)R, a bell-shaped concentration-response curve was observed, whereas construct SP2-CRF1R yielded a monophasic curve. These results demonstrate that the presence of the pseudo signal peptide of the CRF2(a)R was able to prevent Gi-mediated inhibition of the adenylyl cyclase activation.

One may argue that the additional Gi activation of the CRF1R was only detectable in overexpressing transfected cells. To address this question, a cAMP RIA was performed with nontransfected AtT-20 anterior pituitary tumor cells expressing the endogenous CRF1R (23). A bell-shaped concentration-response curve was also observed under these conditions (Fig. 7B) suggesting that Gi activation and impairing this activation in the case of the CRF2(a)R by the pseudo signal peptide could play a role in the natural CRF system.

The fact that the pseudo signal peptide prevents Gi-mediated inhibition of adenylyl cyclase activity (Fig. 7A) may be closely linked to the decreased cell surface expression caused by this domain. If one assumes a limited amount of Gs protein in the cell, a large amount of receptors at the cell surface may deplete the Gs pool at high agonist occupancy, and consequently, Gi coupling may be allowed (bell-shaped concentration-response curve). A low amount of receptor, in contrast, may not be sufficient to deplete Gs, and therefore, Gi coupling may not be observed (monophasic concentration-response curve). However, the fact that stimulation of the endogenous CRF1 receptors of AtT-20 cells also leads to a bell-shaped curve argues against a dominant role of receptor expression, because receptor number is very low in these cells (Fig. 7B). Alternatively, the pseudo signal peptide may favor directly receptor conformations unable to couple to Gi.

To study whether the pseudo signal peptide-mediated decrease of receptor expression is responsible for the observed inhibition of Gi coupling, constructs CRF1R and SP2-CRF1R were stably transfected into HEK 293 cells with the aim to select cell clones with matched cell surface receptor expression (expression levels are variable because of different integration sites of the plasmid DNA). Plasma membrane receptors of the individual clones were quantified by measuring their cell surface GFP fluorescence intensities using confocal LSM (Fig. 8A) and by flow cytometry measurements using intact cells and a monoclonal anti-CRF1R antibody directed against the N tail (Fig. 8B). In the case of the A6-CRF1R clone, cell surface expression is decreased to the level of the B3-SP2-CRF1R clone (Fig. 8, A and B). Nevertheless, the curve for sauvagine-mediated cAMP formation is still bell-shaped (Fig. 8C). Taken together, these results indicate that the pseudo signal peptide-mediated decrease in receptor expression is not responsible for the observed inhibition of Gi coupling.

FIGURE 8.

The presence of the pseudo signal peptide prevents Gi-mediated inhibition of adenylyl cyclase activity independent of receptor expression. A, cell surface expression of constructs CRF1R and SP2-CRF1R in various stably transfected HEK 293 cell clones expressing different amounts of the receptors. The GFP fluorescence signals of the receptor were colocalized with the plasma membrane marker trypan blue using a confocal LSM, and their intensity was quantified using an 8-bit grayscale and the LSM software (15). Columns represent mean values of plasma membrane GFP fluorescence intensity of 20 cells (±S.D.). The quantification is representative of three independent experiments. B, flow cytometry quantification of the cell surface receptors of the cell clones A6-CRF1R and B3-SP2-CRF1R. Plasma membrane receptors of 104 cells were quantified using a monoclonal anti-CRF1R antibody directed against the extracellular N tail and a phycoerythrin-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG. Columns represent mean values of three independent experiments (±S.D.). C, adenylyl cyclase activity assay using the stably transfected HEK 293 cell clones A6-CRF1R and B3-SP2-CRF1R (see A). Intact cells were stimulated with increasing concentrations of the agonist sauvagine, and a cAMP RIA was performed. Data points represent geometric mean values of a single experiment performed in duplicate. Curves are representative of two independent experiments. The calculated EC50 values are (95% confidence limits) as follow: CRF1R (ascending slope), 0.46 nm (0.38–0.56); SP2-CRF1R, 0.48 nm (0.36–0.66).

DISCUSSION

We have analyzed the function of the pseudo signal peptide of the CRF2(a)R in comparison with the conventional signal peptide of the CRF1R. Two results were obtained for the significance of this unique GPCR domain as follows. (i) The presence of the pseudo signal peptide causes a very low cell surface receptor expression. (ii) Moreover, it abolishes Gi-mediated inhibition of adenylyl cyclase activity.

The observed lower cell surface expression is accompanied by an increase in intracellularly retained receptors that are present in their immature form in the early secretory pathway (high mannose and nonglycosylated forms, Fig. 5). These results indicate that the presence of the pseudo signal peptide decreases folding efficiency, consequently leading to more misfolded receptors that are retained by the QCS of the early secretory pathway. Indeed, we could detect a stronger association of the pseudo signal peptide-bearing constructs with the lectin chaperone calnexin (Fig. 6). Molinari and Helenius (24) demonstrated that the calnexin/calreticulin system of the QCS interacts directly with membrane proteins when an N-glycosylation site is present within the N-terminal 50 residues. The uncleaved pseudo signal peptide introduces an additional asparagine residue that is indeed N-glycosylated (Asn13, see Ref. 18). This may facilitate the observed stronger interaction of unfolded or partially folded receptors with these lectin chaperones. Unfortunately, this hypothesis is difficult to address experimentally because mutation of Asn13 also converts the pseudo signal peptide into a conventional signal peptide that is cleaved off (Figs. 2 and 3) (18). An alternative way by which the pseudo signal peptide may decrease folding efficiency is by impairing N tail translocation during protein integration into the ER membrane by the translocon machinery.

The experiments in this study compare the functional significance of the CRF2(a)R pseudo signal peptide with that of the conventional CRF1R signal peptide. Interestingly, deletion of the signal peptide of the CRF2(a)R without replacing it by another sequence leads to a further increase in the amount of immature receptor forms (Ref. 18; mutant ΔSP-CRF2(a)R). Thus, when the CRF2(a)R is considered alone, the pseudo signal peptide also seems to facilitate folding to a certain extent. These data may be put together as follows. The CRF2(a)R without its pseudo signal peptide or another signal sequence is expressed almost exclusively in its immature form in the early secretory pathway. The presence of the pseudo signal peptide somewhat increases folding efficiency that is, however, still very low in comparison with that mediated by the presence of a conventional signal peptide.

The fact that the pseudo signal peptide prevents Gi-mediated inhibition of adenylyl cyclase activity (Fig. 7) seems not to be due to the decreased cell surface expression caused by this domain. Decreasing cell surface expression of CRF1R to the level of construct SP2-CRF1R still leads to a bell-shaped concentration-response curve (Fig. 8, A–C). Obviously, the presence of the pseudo signal peptide favors receptor conformations that are unable to couple to Gi. Such a function should, however, be independent of ligand binding, because affinities of the CRF2(a)R for both its selective and specific agonists are not influenced by the pseudo signal peptide (18). It was shown previously that heterodimerization may affect selectivity of GPCRs for the different G proteins. An influence on Gi coupling, for example, was observed upon coexpression of μ- and δ-opioid receptors (25, 26) and CCR5/CCR2 chemokine receptors (27). If one speculates that homodimerization may also influence G protein selectivity, the presence of the pseudo signal peptide may prevent receptor dimerization and in turn impair Gi coupling. This speculation should be addressed in a future study.

In the case of the CRF2(b)R subtype, it was shown recently that this receptor is able to couple to Gi at high agonist occupancy (12) in contrast to the CRF2(a)R subtype studied here. It is long known that signal peptide sequences, even of closely related proteins, have a conserved conformation but do not share sequence homologies (28, 29). Indeed, the pseudo signal peptide of the CRF2(a)R and the corresponding sequence of the CRF2(b)R differ completely in their sequence (MDAALLLSLLEANCSLALA, CRF2(a)R versus MGTPGSLPSAQLLLCLFSLLPVLQVA, CRF2(b)R). Signal peptide prediction by the SignalP 3.0 program (30) indicates a cleavage probability of 98% for the CRF2(b)R, and it is thus conceivable that it possesses a conventional signal peptide like the CRF1R.

The properties mediated by the pseudo signal peptide of the CRF2(a)R were entirely transferable to the CRF1R in the signal peptide exchange experiments. The sequence may consequently be considered as a novel transport signal negatively influencing receptor processing. The reason why it is advantageous to keep CRF2(a)R expression low by this unique domain remains elusive. However, the fact that the bell-shaped concentration-response curve and thus Gi coupling is also observed in the case of the endogenous CRF1R (Fig. 7B) indicates that the use of these different signal sequences may play a role in vivo.

Finally, it is intriguing to speculate that the pseudo signal peptide is part of a novel mechanism regulating cell surface expression of GPCRs. Although the pseudo signal peptide failed to initiate ER targeting in various cell types and remained uncleaved (18), it is not excluded at the moment that it may gain conventional signal peptide functions under certain conditions. One may speculate, for example, that a protein factor blocks conventional signal peptide function, e.g. by preventing signal recognition particle binding during early receptor biogenesis. Unknown physiological or pathophysiological conditions may prevent binding of this factor, and a strong up-regulation of the CRF2(a)R at the cell surface accompanied by the ability to activate Gi would be the consequence.

Acknowledgments

We thank Gisela Papsdorf of the cell culture facilities of the Leibniz-Institut für Molekulare Pharmakologie and Erhard Klauschenz from the DNA sequencing service group for their contributions. We also thank Jenny Eichhorst for excellent technical assistance.

This work was supported by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft Grant SFB 449.

C. Rutz and R. Schülein, unpublished results.

- CRF

- corticotropin-releasing factor

- CRF1R

- rat corticotropin-releasing factor receptor type 1

- CRF2(a)R

- rat corticotropin-releasing factor receptor type 2a

- EndoH

- endoglycosidase H

- ER

- endoplasmic reticulum

- GPCR

- G protein-coupled receptor

- LSM

- laser scanning microscopy

- PNGaseF

- peptide N-glycosidase F

- SP

- signal peptide

- QCS

- quality control system.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hauger R. L., Risbrough V., Brauns O., Dautzenberg F. M. (2006) CNS Neurol. Disord. Drug Targets 5, 453–479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hauger R. L., Grigoriadis D. E., Dallman M. F., Plotsky P. M., Vale W. W., Dautzenberg F. M. (2003) Pharmacol. Rev. 55, 21–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Denver R. J. (2009) Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 1163, 1–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hauger R. L., Risbrough V., Oakley R. H., Olivares-Reyes J. A., Dautzenberg F. M. (2009) Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 1179, 120–143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Refojo D., Holsboer F. (2009) Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 1179, 106–119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Valdez G. R. (2009) Curr. Pharm. Des. 15, 1587–1594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Spina M., Merlo-Pich E., Chan R. K., Basso A. M., Rivier J., Vale W., Koob G. F. (1996) Science 273, 1561–1564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coste S. C., Kesterson R. A., Heldwein K. A., Stevens S. L., Heard A. D., Hollis J. H., Murray S. E., Hill J. K., Pantely G. A., Hohimer A. R., Hatton D. C., Phillips T. J., Finn D. A., Low M. J., Rittenberg M. B., Stenzel P., Stenzel-Poore M. P. (2000) Nat. Genet. 24, 403–409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grammatopoulos D. K., Dai Y., Randeva H. S., Levine M. A., Karteris E., Easton A. J., Hillhouse E. W. (1999) Mol. Endocrinol. 13, 2189–2202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wietfeld D., Heinrich N., Furkert J., Fechner K., Beyermann M., Bienert M., Berger H. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 38386–38394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gutknecht E., Van der Linden I., Van Kolen K., Verhoeven K. F., Vauquelin G., Dautzenberg F. M. (2009) Mol. Pharmacol. 75, 648–657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Milan-Lobo L., Gsandtner I., Gaubitzer E., Rünzler D., Buchmayer F., Köhler G., Bonci A., Freissmuth M., Sitte H. H. (2009) Mol. Pharmacol. 76, 1196–1210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wallin E., von Heijne G. (1995) Protein Eng. 8, 693–698 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Higy M., Junne T., Spiess M. (2004) Biochemistry 43, 12716–12722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alken M., Rutz C., Köchl R., Donalies U., Oueslati M., Furkert J., Wietfeld D., Hermosilla R., Scholz A., Beyermann M., Rosenthal W., Schuelein R. (2005) Biochem. J. 390, 455–464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huang Y., Wilkinson G., Willars G. (2010) Br. J. Pharmacol. 159, 237–257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Köchl R., Alken M., Rutz C., Krause G., Oksche A., Rosenthal W., Schuelein R. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 16131–16138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rutz C., Renner A., Alken M., Schulz K., Beyermann M., Wiesner B., Rosenthal W., Schuelein R. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 24910–24921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sambrook J., Russel D. W. (2001) Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wüller S., Wiesner B., Löffler A., Furkert J., Krause G., Hermosilla R., Schaefer M., Schuelein R., Rosenthal W., Oksche A. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 47254–47263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grantcharova E., Furkert J., Reusch H. P., Krell H. W., Papsdorf G., Beyermann M., Schulein R., Rosenthal W., Oksche A. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 43933–43941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Begitt A., Meyer T., van Rossum M., Vinkemeier U. (2000) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 10418–10423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen R., Lewis K. A., Perrin M. H., Vale W. W. (1993) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 90, 8967–8971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Molinari M., Helenius A. (2000) Science 288, 331–333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Charles A. C., Mostovskaya N., Asas K., Evans C. J., Dankovich M. L., Hales T. G. (2003) Mol. Pharmacol. 63, 89–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.George S. R., Fan T., Xie Z., Tse R., Tam V., Varghese G., O'Dowd B. F. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 26128–26135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mellado M., Rodríguez-Frade J. M., Vila-Coro A. J., Fernández S., Martín de Ana A., Jones D. R., Torán J. L., Martínez-A C. (2001) EMBO J. 20, 2497–2507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.von Heijne G. (1985) J. Mol. Biol. 184, 99–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.von Heijne G. (1990) Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2, 604–608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bendtsen J. D., Nielsen H., von Heijne G., Brunak S. (2004) J. Mol. Biol. 340, 783–795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]