Abstract

Alzheimer disease neurons are characterized by extraneuronal plaques formed by aggregated amyloid-β peptide and by intraneuronal tangles composed of fibrillar aggregates of the microtubule-associated Tau protein. Tau is mostly found in a hyperphosphorylated form in these tangles. Glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK3β) is a proline-directed kinase generally considered as one of the major players that (hyper)phosphorylates Tau. The kinase phosphorylates mainly (Ser/Thr)-Pro motifs and is believed to require a priming activity by another kinase. Here, we use an in vitro phosphorylation assay and NMR spectroscopy to characterize in a qualitative and quantitative manner the phosphorylation of Tau by GSK3β. We find that three residues can be phosphorylated (Ser-396, Ser-400, and Ser-404) by GSK3β alone, without priming. Ser-404 is essential in this process, as its mutation to Ala prevents all activity of GSK3β. However, priming enhances the catalytic efficacy of the kinase, as initial phosphorylation of Ser-214 by the cAMP-dependent protein kinase (PKA) leads to the rapid modification by GSK3β of four regularly spaced additional sites. Because the regular incorporation of negative charges by GSK3β leads to a potential parallel between phospho-Tau and heparin, we investigated its interaction with the heparin/low density lipoprotein receptor binding domain of human apolipoprotein E. We indeed observed an interaction between the GSK3β-promoted regular phospho-pattern on Tau and the apolipoprotein E fragment but none in the absence of phosphorylation or the presence of an irregular phosphorylation pattern by the prolonged activity of PKA. Apolipoprotein E is therefore able to discriminate and interact with specific phosphorylation patterns of Tau.

Keywords: Alzheimer Disease, Apolipoproteins, NMR, Protein Phosphorylation, Tau

Introduction

The Tau proteins are a family of microtubule-associated proteins that are expressed predominantly in neurons and are produced by alternative splicing of a single gene (1). The longest mature isoform present in the nervous central system (Tau441) is an intrinsically unstructured protein consisting of 441 amino acids and lacking well defined globular domains (2). Tau can be divided into the following two large domains; the projection domain covers the N-terminal half of the molecule, and the C-terminal domain contains four 32 amino acids repeats, the microtubule-binding repeats (MTBRs)3 that are directly involved in microtubule binding (3). Two cysteine residues at positions 291 and 322 are present in the Tau441 isoform, whereas the fetal form characterized by three instead of four MTBRs contains only the cysteine at position 322.

Tau is a phosphoprotein, and numerous in vitro or cellular studies have demonstrated that site-specific phosphorylation of Tau by various protein kinases regulates its ability to bind and stabilize microtubules. Phosphorylation of Tau at distinct sites is generally considered as a critical marker for the progression of Alzheimer disease (AD). The Braak staging, based initially on silver staining of postmortem brain slices (4, 5), recently has been performed with the AT8 antibody (6), recognizing a specific phosphorylation pattern at the Ser-202/Thr-205 site. In the cerebrospinal fluid of AD patients, the level of Ser-396-phosphorylated Tau relative to the total level of Tau is equally considered as a reliable measure of the severity of the disease (7). Of specific interest to our work here, the glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK3β) has been shown to phosphorylate Tau in vitro (8), in cell models (9), and in mouse models (10–12). Current evidence indicates that GSK3β is a major kinase for Tau phosphorylation at disease-relevant proline-directed sites (13), including the Ser-396 of Tau in the brain (14), underscoring its importance both in physiological and pathological conditions.

GSK3β is a 45-kDa Ser/Thr proline-directed kinase that is expressed ubiquitously and found at high levels in the brain where it localizes predominantly to neurons (15). It is a typical two-domain kinase comprising a small N-terminal β-strand domain and a larger C-terminal α-helical domain (16, 17). The identification of a binding pocket for a negative charge within the substrate-binding cleft of GSK3β immediately suggests direct coupling between phosphate-primed substrate binding and catalytic activation, and hence it explains why GSK3β recognizes specifically the (S/T)XXX(pS) motif, whereby the first priming phosphorylation event is performed by another kinase (18–20). The activity of GSK3β is furthermore regulated by its own phosphorylation. Phosphorylation of GSK3β on Tyr-216 increases its activity (16) and can occur in an autocatalytic process, which explains the good activity of recombinantly expressed GSK3β (21, 22). On the contrary, the phosphorylation of its Ser-9 residue by PKB/Akt in response to an insulin signal inhibits its activity (23).

The mechanism by which GSK3β phosphorylates Tau is not yet fully understood. When Tau is purified from bovine brain and dephosphorylated, it becomes a poor substrate for GSK3β (24). On the other hand, the purified endogenously phosphorylated Tau from bovine brain is efficiently phosphorylated by GSK3β (24). In vivo as well as in vitro, Tau becomes a more favorable substrate for GSK3β when it is prephosphorylated by a non-proline-dependent kinase (25, 26) such as the cAMP-dependent protein kinase (PKA) or by another proline-dependent kinase such as the CDK5 cyclin-dependent kinase (27, 28). PKA is able in vitro to phosphorylate Tau at the Ser-208, Ser-214, Ser-324, Ser-416, Ser-356, and Ser-409 sites, with a clear preference for the Ser-214 site (29, 30), whereas CDK5 phosphorylates Tau at the Ser-235 site (28, 31). Godemann et al. (32) studied in vitro the GSK3β phosphorylation of Tau441 by two-dimensional phosphopeptide mapping, immunoblotting with phosphorylation-sensitive antibodies, and phosphopeptide sequencing. They found that GSK3β phosphorylates predominantly (Ser/Thr)-Pro motifs in Tau protein that occur in closely spaced pairs, in the order Ser-396/Ser-404, Ser-46/Thr-50, and Ser-202/Thr-205 but not at the Ser-262 position. In HEK-293 cells co-transfected with GSK3β and Tau, a direct phosphorylation of Tau at the Ser-202 position was observed but no phosphorylation for the Ser-262, Ser-235, and Ser-404 positions (14). The in vivo phosphorylation of Ser-396 would therefore occur sequentially, with a priming kinase phosphorylating first Ser-404, followed by GSK3β that sequentially phosphorylates Ser-400 and then Ser-396. Transfecting the same HEK-293 cells with Tau, GSK3β, and CDK5, it was found that CDK5 could play the role of priming kinase, as it phosphorylates the Ser-202, Ser-235, and Ser-404 sites (13). The Ser-235 phosphorylation by CDK5 thereby enhances GSK3β-catalyzed Thr-231 phosphorylation, and the Ser-404 phosphorylation by CDK5 enhances the sequential phosphorylation of Ser-400 and Ser-396 by GSK3β (14).

Whereas mutations in both Tau (33) and Alzheimer precursor protein, the transmembrane protein that after cleavage by both the β- and γ-secretase gives rise to the amyloid-β peptide (34), have clearly established a functional link between those two molecules and the disease, isoform 4 of apolipoprotein E (apoE4) was equally found to be a major risk factor for the common late onset familial and sporadic forms of AD and other forms of neurodegeneration (35). Risk for AD increased from 20 to 90% and mean age at onset decreased from 84 to 68 years with increasing number of APOE-ϵ4 alleles in 42 families with late onset AD (35). However, contrary to Tau and β-amyloid that are the major components of the tangles and plaques that are found in the diseased brain and that are thought to underlie their neurotoxicity, the molecular mechanism(s) for the clinical correlation between AD and apoE4 remain a subject of controversy (36–38). ApoE plays a key role in facilitating the clearance of lipoprotein particles from plasma via its ability to bind the low density lipoprotein (LDL) receptor (39). It has been shown to be involved in a wide range of physiological and pathological processes such as nerve regeneration (40), cytoskeletal stabilization (41), and lipid metabolism (42). Its role in neurodegeneration as observed in AD derives from the fact that human apoE possesses a genetic polymorphism due to a single arginine-cysteine interchange (42). Three common isoforms, apoE2, apoE3, and apoE4, are the products of three alleles of the APO-E gene. ApoE3 (Cys-112 and Arg-158) is the most common isoform (42), whereas apoE2 (Cys-112 and Cys-158) displays defective receptor binding and is associated with type III dyslipidemia. The apoE4 (Arg-112 and Arg-158) isoform has been associated with late onset AD (35).

Plasma apoE, a 299-amino acid exchangeable apolipoprotein (34 kDa), is composed of two domains that are linked via a protease-sensitive loop (42). The N-terminal domain (residues 1–191) contains the LDL receptor-binding site in the vicinity of residues 140–180 (43) and an overlapping heparin-binding site (residues 142–147) (44). The 10-kDa C-terminal domain (residues 210–299) accommodates high affinity lipid-binding sites (42) and the amyloid-β peptide binding region (45). This latter interaction between apoE and β-amyloid has led to the hypothesis that the correlation between the disease and the apoE isoform relies on an Aβ-dependent mechanism (36). However, Strittmatter et al. (46) found in vitro under nonreducing conditions that Tau binds avidly via its MTBR region to the receptor-binding N-terminal domain apoE3 but not to apoE4, suggesting an alternative molecular basis involving Tau rather than Aβ for the link between apoE polymorphism and AD. Both the presence of a reducing agent and the (hyper)phosphorylation of Tau with a brain extract abolished this interaction, raising questions about the chemical nature of the molecular interaction.

Here, we present a detailed NMR study of the in vitro phosphorylation of Tau by GSK3β, and this in the absence or presence of priming by PKA. We previously showed that NMR spectroscopy allows for a qualitative and quantitative view of the complete phosphorylation pattern of Tau, and we compared the results for PKA (29) and CDK2/CycA (47) with those obtained by immunochemistry and/or mass spectrometry. We found that GSK3β can generate without priming the regular C-terminal phosphorylation pattern at Ser(P)-404/-400/-396 but that it requires priming by PKA to generate a similar pattern in the proline-rich region. Because NMR is very suited for interaction mapping between proteins and/or other (bio)molecules, we set out to map a putative interaction between Tau and the 22-kDa N-terminal apoE domain. Under the reducing conditions for our NMR experiments, we could not find any interaction when Tau was not phosphorylated or phosphorylated in irregular positions as generated by prolonged action of PKA. However, the GSK3β phospho-Tau sample indeed interacts with the apoE3 domain via the GSK3-generated regularly spaced phosphorylation motifs. GSK3β thus can mediate this interaction in a selective manner, which might constitute a novel molecular basis for the clinical link between the apoE isoform and the occurrence of AD disease.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Preparation of Recombinant Kinases (GSK3β and PKA)

Glutathione S-transferase (GST)-human GSK3β expression vector with the GST tag in the N-terminal position (GSK3β-GST-pGEX) was obtained from Prof. G. Divita (Montpellier, France). Human GSK3β was expressed in Escherichia coli (BL21(DE3)Star, Novagen) and purified from bacterial lysates by affinity chromatography on glutathione-Sepharose beads (GE Healthcare). The catalytic subunit domain of the cAMP-dependent protein kinase (PKA) was received from Prof. H. Schwalbe, Frankfurt, Germany (49).

Preparation of Recombinant Tau Proteins

The E. coli BL21(DE3)Star (Novagen), carrying the longest human Tau isoform (441 amino acids) cloned in pET15b plasmid (Novagen) under the control of a T7 promoter with a sequence encoding the N-terminal His6 tag (numbering of the amino acids is according to the longest human Tau isoform and does not take into account the His tag), was grown at 37 °C in media containing ampicillin (100 μg/ml). Isotope labeling (15N and/or 13C) was performed by growing cells at 37 °C in 2 liters of LB medium until the A600 reached 0.6–0.8 units. The cells were then gently centrifuged and suspended in 1 liter of modified minimal M9 medium containing 1 g of [15N]NH4Cl and 2 g of [13C]glucose (Isotec, Sigma) or 4 g of [12C]glucose and allowed to grow for 30 min. The expression of the recombinant protein was then induced by addition of 0.4 mm isopropyl 1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside, and the culture was pursued for 3 h at 37 °C. Purification of the heat-stable soluble recombinant Tau protein includes 15 min of heating at 75 °C, followed by a nickel-immobilized metal affinity chromatography on a HiTrap chelatin HP column (GE Healthcare). Purity of the fractions was checked on 12% SDS-PAGE. The pooled fractions containing the His-tagged recombinant protein were dialyzed (cutoff 3000 Da) against 50 mm ammonium bicarbonate, 1 mm DTT before lyophilization. The lyophilized powder was directly suspended in the kinase buffer. The concentration of recombinant Tau was determined at 280 nm using a molar absorption coefficient of 7400 m−1·cm−1 at 280 nm.

Site-directed mutations of Ser/Thr to Ala residues (S404A and T205A) and Gly to Ala residues (G207A) were obtained by PCR amplification of the Tau cDNA or the full Tau-pET15b recombinant plasmid templates using mutagenic primers. All recombinant constructs were verified by DNA sequencing.

Preparation of Recombinant Human ApoE3 N-terminal Domain

The N-terminal domain of human apoE3, apoE3(1–191), was produced by heterologous expression using the plasmid pET11a (Novagen) in E. coli and purified as described previously (50).

Phosphorylation of Tau by PKA

To phosphorylate 15N-labeled Tau by PKA, 10 μm Tau was incubated with 0.1 μm catalytic subunit of PKA in kinase buffer (5 mm ATP, 12.5 mm MgCl2, 50 μm EDTA, 55 mm NaCl, 5 mm DTT, and 50 mm Hepes, pH 8.0) during 15 min or 5 h, respectively, at 30 °C. The shorter time leads to the phosphorylation of Ser-214 and the longer to the phosphorylation of Ser-208, Ser-214, Ser-324, Ser-416, Ser-356, and Ser-409 (29). The reaction was heat-inactivated at 75 °C for 15 min, and the heat-denatured PKA was pelleted by centrifugation. The supernatant containing the heat-stable soluble Tau was dialyzed against 50 mm ammonium bicarbonate, 1 mm DTT before lyophilization. The lyophilized protein was suspended in 25 mm NaCl, 1 mm DTT, 25 mm Na2HPO4/NaH2PO4, pH 6.8, to obtain samples between 50 and 100 μm of Tau protein for NMR analysis or directly used for further phosphorylation by GSK3β.

Phosphorylation of Tau by GSK3β

The phosphorylation of 10 μm Tau, primed or not by PKA, was performed with 1 μm GSK3β in kinase buffer, at 30 °C, during 6 or 12 h. The procedure described above for PKA-phosphorylated Tau was similarly used to prepare NMR samples of the GSK3β-phosphorylated Tau.

For the kinetic study, the Ser(P)-214-Tau samples were incubated with GSK3β, in the conditions described above, for different periods, from 0 to 12 h. Aliquots were kept at different time points for further analysis by SDS-PAGE and/or NMR analysis.

NMR Spectroscopy

NMR measurements were performed at 293 K on a Bruker DMX600 spectrometer with a triple resonance cryogenic probe head or a Bruker Avance 800 MHz spectrometer with a regular triple resonance probe (Bruker, Karslruhe, Germany). Two-dimensional 1H-15N HSQC spectra, with 1024 complex points for 13 ppm in the proton dimension and 128 complex points for 30 ppm in the 15N indirect dimension, were used to monitor Tau phosphorylation. Water suppression was performed using the Watergate scheme (51). Resonance assignments of phosphorylated residues of Tau were achieved using triple resonance experiments (HNCACB and HN(CO)CACB) with standard Bruker pulse programs complemented with the HN(CA)NNH experiment (52). Acquisition parameters were 1024 (1H), 47 (15N), and 72 (13C) complex points and 16 or 8 scans per increment.

Proton chemical shifts were measured in parts per million and referenced relative to the methyl proton resonances (put at 0.0 ppm) of the internal standard trimethyl silyl propionate. Three-dimensional spectra processing and peak picking were performed using the TOPSPIN 1.3 (Bruker, Karlsruhe, Germany).

Study of the Interaction between the ApoE3 N-terminal Domain and the Unphosphorylated or Phosphorylated Tau

Interaction studies were performed in NMR buffer, 25 mm NaCl, 1 mm DTT, 25 mm Na2HPO4/NaH2PO4, pH 6.8, at 20 °C. HSQC spectra of various mixtures were acquired at a molar ratio 15N-labeled Tau/unlabeled apoE3(1–191) of 1:2 (100:200 μm). A control HSQC of the various 15N-labeled Tau samples was recorded in the same conditions.

RESULTS

Tau Phosphorylation by GSK3β after Priming with PKA

Our assay started with recombinant Tau incubated for 15 min with PKA. We previously showed that the latter incubation leads to a near complete phosphorylation at the Ser-214 site, whereas the other sites are hardly modified (29). This sample was used as starting material for subsequent phosphorylation by recombinant GSK3β for 12 h. Detection of the phosphorylated serine or threonine residues in the resulting HSQC spectrum (Fig. 1) is facilitated by the fact that phosphorylation shifts their amide proton resonance downfield to an empty region of the 15N-labeled Tau HSQC spectrum (53). Taking further into account the general validity of the random coil chemical shift values for a natively unfolded protein such as Tau (54) and the characteristic 2 ppm Cα chemical shift for residues that precede a proline (55, 56), HNCACB and HN(CO)CACB spectra complemented by the HN(CA)NNH experiment connecting the 15N frequencies of neighboring residues proved sufficient to identify the nature of every phosphorylated amino acid and of their preceding residue. Applying windows of 56.5 ± 0.5 ppm for the Ser(P) and 60 ± 0.5 ppm for the Thr(P) in the product plane approach starting from the HNCACB spectrum (57) allowed us to identify seven phosphorylated residues, and manual inspection of the carbon chemical shifts in the HN(CO)CACB spectrum identified their downstream neighbor (see Fig. 1 and Table 1).

FIGURE 1.

1H-15N HSQC spectrum of PKA-GSK3β-phosphorylated 15N,13C-labeled Tau. See text for the phosphorylation conditions and Table 1 for the assignment of the identified peaks.

TABLE 1.

Assignment of Tau peaks shifted downfield of 8.6 ppm after 15N-13C-Ser(P)-214-Tau (primed by PKA) was phosphorylated by GSK3β (1 μm) during 12 h

Peaks previously characterized by NMR analysis of Tau phosphorylated by PKA (29) or by CDK (47) are marked by * or **, respectively.

| HSQC δ (1H ppm; 15N ppm) | (CBCANH) Cαi/Cβi (ppm) (residue) | (CBCAcoNH) Cαi-1/Cβi-1 (ppm) (preceding residue) comments | Assignment and comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| 9.10; 118.8 | 58.0/65.3 (Ser(P)) | 55.68/30.84 (Arg) | Arg-Ser(P)-195-Gly only observed after 12 h |

| 9.05; 118.20 | 57.8/65.5 (Ser(P)) | 63.16/31.95 (Pro) | Pro-Ser(P)-214-Leu* |

| 8.97; 117.8 | 58.0/65.5 (Ser(P)) | 56.0/30.57 (Arg) | Arg-Ser(P)-210-Arg observed after 3 h |

| 8.48; 116 | 60.3/71.9 (pThr-Pro) | 44.69 (Gly) | Gly-Thr(P)-205-Pro** |

| 8.76; 120.6 | 55.8/65.0 (Ser(P)-Pro) | 57.44/64.36 (Ser) | Ser-Ser(P)-199-Pro** Observed after 3 hrs |

| 8.91; 122 | 56.48/– (Ser(P)-Pro) | 55.06/34.0 (Lys) | Lys-Ser(P)-396-Pro |

| 8.98; 121.4 | 58.02/– (Ser(P)) | 61.8/32.8 (Val) | Val-Ser(P)-400-Gly |

| 8.66; 120.1 | 55.8/– (Ser(P)-Pro) | 61.77/69.9 (Thr) | Thr-Ser(P)404-Pro** |

Sites of Tau Phosphorylated by GSK3β in the Absence of Priming by PKA

As Tau is reported to become a more favorable substrate for GSK3β when it is prephosphorylated by other kinases (25–27), we expected a low efficiency for the Tau phosphorylation by GSK3β in the absence of any priming. We therefore used the same relatively long incubation time (12 h) of GSK3β (1 μm) to phosphorylate the unprimed 15N-labeled Tau. As depicted by the HSQC spectrum of supplemental Fig. A, three phosphorylated peaks were easily identified on the basis of their chemical shift values as follows: Ser(P)-396, Ser(P)-400, and Ser(P)-404. Although phosphate incorporation at all three sites was well below stoichiometry, the Ser(P)-404 cross-peak was the most intense, followed by the Ser(P)-396 and Ser(P)-400 peaks of equal intensity. The Ser-404 residue, which is followed by a proline residue, can therefore be phosphorylated by GSK3β without any priming. When this site is first phosphorylated by GSK3β, it could prime for the other sites.

To underscore this scenario, we mutated the Ser-404 of wild type Tau into Ala and incubated the unprimed TauS404A with GSK3β under the same experimental conditions as above. As expected, we did not observe any phosphorylation of Ser-400 and Ser-396 by GSK3β. When we primed the same TauS404A by PKA (Ser(P)-214-TauS404A), the phosphorylation events at Ser-195, Ser-199, Thr-205, and Ser-210 (supplemental Fig. B) showed up in the HSQC spectrum, but we did not observe any C-terminal phosphate incorporation. Therefore, we can conclude that under our experimental conditions, GSK3β is able to phosphorylate wild type Tau directly without any priming at the proline-directed Ser-404 position. This phosphorylation results in the creation of a Ser-Xaa-Xaa-Xaa-Ser(P)-404 motif recognized by GSK3β (16) that allows the subsequent phosphorylation of Ser-400 and Ser-396.

Kinetic Phosphorylation by GSK3β of Tau Prephosphorylated at Serine 214

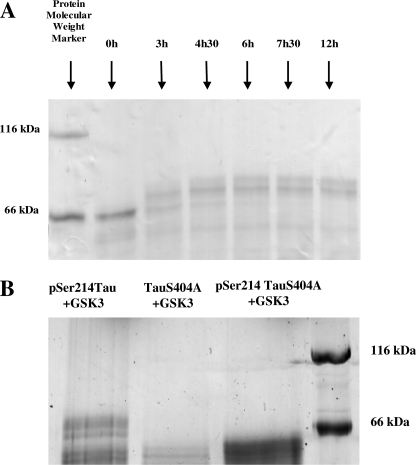

To determine a time scale for the kinase activity of GSK3β, Tau primed at Ser-214 by PKA (Ser(P)-214-Tau) was incubated in kinase buffer in the presence of recombinant GSK3β for different periods. Samples were taken during the course of the reaction and were split for analysis by SDS-PAGE (58) or for NMR analysis after purification and concentration. The unique PKA site of phosphorylation present at position 214 did not change the migration of Tau in SDS-PAGE (Fig. 2A) (29). Upon phosphorylation of Ser(P)-214-Tau by GSK3β, we observed an increasing slow down of the electrophoretic mobility in SDS-PAGE over the time course. After 3 h of phosphorylation, we observed one band over the position of the migration of albumin (Fig. 2A). NMR analysis of the same sample demonstrated observable phosphorylation cross-peaks corresponding to Ser-404, Ser-210, and Ser-205 (Fig. 3B). After 4.5 h of incubation, an additional band over the precedent became observable (Fig. 2A). This is a result of phosphate incorporation at the Ser-404, Ser-400, Ser-396, Ser-210, Thr-205, and Ser-199 positions as observed by NMR (Fig. 3C). After 6 h of incubation, the initial Ser(P)-214-Tau band in front of the position of albumin completely disappeared. NMR analysis revealed that after this incubation time, Ser-404, Ser-400, Ser-396, Ser-210, Thr-205, Ser-199, and Ser-195 of the Ser(P)-214-Tau (Fig. 3D) were phosphorylated. The electrophoretic profile did not vary significantly upon increasing the incubation time from 6 to 12 h, showing that the reaction reaches a plateau. From this combined SDS-PAGE and NMR analysis, it is interesting to note that the sole quantitative phosphorylation of Ser-404 is able to induce a noticeable electrophoretic shift in the migration of Ser(P)-214-Tau, in agreement with the previous report of Godemann et al. (32). To confirm this observation, we performed SDS-PAGE on the S404A mutant after incubation of the sample for 6 h with GSK3β. No shift in the electrophoretic mobility was observed when either TauS404A or Ser(P)-214-TauS404A was incubated with GSK3β (Fig. 2B). For the latter, the band does migrate at slightly higher apparent molecular weights than the former, suggesting that the phosphorylation events at Ser-195, Ser-199, Thr-205, and Ser-210 might be responsible for the additional shift that was observed for wild type Ser(P)-214-Tau after 3 h of incubation with GSK3β. We did not prolong the incubation further with GSK3β as degradation of Tau was observed after 12 h of incubation.

FIGURE 2.

A, SDS-PAGE (12%) kinetic study of the phosphorylation of Ser(P)-214-Tau incubated with a catalytic amount (1 μm) of recombinant GSK3β. Incubation times are indicated above the gel. B, 12% SDS-PAGE of wild type Tau primed by PKA at Ser-214 and submitted to the action of GSK3β (1st lane). 2nd lane, mutant Tau S404A not primed by PKA and submitted to the action of GSK3β. 3rd lane, mutant Tau S404A primed by PKA at Ser-214 and submitted to the action of GSK3β.

FIGURE 3.

NMR kinetic study of the phosphorylation of Ser(P)-214-Tau by GSK3β. A, 1H-15N HSQC of 15N-labeled Tau before the action of PKA and GSK3β (A),1H-15N HSQC spectra of 15N-labeled Ser(P)-214-Tau incubated for 3 (B), 4.5 (C), and 6 h (D) with 1 μm GSK3β at 30 °C. Peak identity was inferred from the HSQC assignments obtained on the PKA/GSK3β phosphorylated doubly labeled 15N-13C-Tau sample (Fig. 1 and Table 1).

A quantitative analysis of the kinetics of phosphate incorporation at the different positions through the site-specific integration of the phospho-cross-peaks in the corresponding NMR spectra revealed that in the C terminus only the phosphorylation peak corresponding to Ser(P)-404 was present after 3 h of incubation (Fig. 3B). The phosphorylation sites corresponding to Ser(P)-400 or Ser(P)-396 appear only later, after 4 h 30 min for the former (Fig. 3C) and after 6 h for the latter (Fig. 3D). This confirms that phosphorylation of Ser-396 and Ser-400 by GSK3β depends on the previous phosphorylation by GSK3β of Ser-400 and Ser-404, respectively, and suggests that the enzyme acts in a distributive manner (59). GSK3β hence would not “bind and slide” along the Tau substrate in a processive manner, as this would lead to equal intensities of the three C-terminal phosphorylation events in the spectrum. In contrast to this intuitive processive reaction, our results suggest that after phosphorylation of Ser-404, there is intermediate substrate release before the consecutive phosphorylation of Ser-400 and Ser-396. A similar conclusion can be drawn for the Ser(P)-214 primed phosphorylation of the proline-rich region. Although cross-peaks corresponding to Ser(P)-210, Thr(P)-205, and Ser(P)-199 were observable after 3 h, they increased gradually in intensity after 4.5 h, and Ser(P)-195 became only visible in the last sample corresponding to 6 h of GSK3β incubation. We thus conclude that the Ser-404 is a major site for the GSK3β kinase that is phosphorylated rapidly despite the absence of priming and that the other sites are modified through the anchoring of Tau via its priming site (be it Ser(P)-404 or Ser(P)-214) in a distributive manner.

Study of Interaction between the 22-kDa N-terminal Domain of Human ApoE3(1–191) and (Phospho-)Tau

We recorded the HSQC spectrum of 100 μm 15N-labeled Tau in the presence of 200 μm unlabeled apoE3(1–191) under reductive conditions (in the presence of 1 mm DTT) and compared it with the HSQC spectrum of 100 μm 15N-labeled Tau in the same buffer. Both spectra showed only marginal chemical shift differences despite the excess of apoE3 (Fig. 4, left panel). On this basis, we conclude that no interaction occurs between the two proteins in the conditions used. When 15N-labeled Tau is phosphorylated by 0.1 μm PKA during 5 h at 30 °C (Tau-PKA), this results in the phosphorylation of Tau at six positions; Ser(P)-208, Ser(P)-214, Ser(P)-324, Ser(P)-416, Ser(P)-356, and Ser(P)-409 (29). We used this phosphorylated Tau sample to probe in a similar manner by comparative NMR spectra a possible interaction between PKA-Tau and apoE3, but we again found no significant chemical shift changes that might indicate a molecular interaction between both proteins (Fig. 4, middle panel).

FIGURE 4.

1H-15N HSQC spectra of Tau and phosphorylated Tau at a final concentration of 100 μm without (red) or with (black) the 22-kDa N-terminal domain of human apolipoprotein E3:1–191 (apoE22K) at a final concentration of 200 μm to probe their interaction. Left panel, Tau is not phosphorylated; middle panel, Tau is phosphorylated 5 h by PKA (Tau-PKA), and right panel, Tau is phosphorylated at Ser-214 by PKA prior to phosphorylation by GSK3β during 6 h (Ser(P)-214-Tau-GSK3).

Ser(P)-214-Tau phosphorylated by 1 μm GSK3β during 6 h at 30 °C (Ser(P)-214-Tau-GSK3) results in the partial phosphorylation of Tau at eight positions that were identified as Ser(P)-404, Ser(P)-400, Ser(P)-396 in the C terminus and Ser(P)-214, Ser(P)-210, Thr(P)-205, Ser(P)-199, and Ser(P)-195 in the proline-rich region. In contrast to the absence of shifts for the Tau resonances in non- or PKA-phosphorylated Tau upon addition of the apoE3 N-terminal domain, we observed this time clear chemical shift differences in the Ser(P)-214-Tau-GSK3 spectrum after adding the apoE3 domain (Fig. 4, right panel). In the presence of apoE3(1–191), all resonances corresponding to phosphorylated residues shift downfield, and this shift extends to cross-peaks of residues that are not phosphorylated directly, such as Gly-207, but that are close to phosphorylated residues. We can conclude from these spectra that apoE3(1–191) interacts with a large region of the Ser(P)-214-Tau-GSK3 molecule spanning the two regular phospho-arrays generated in the C terminus and proline-rich region, and this interaction critically depends on these phospho-patterns.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we have mapped by heteronuclear NMR experiments the GSK3β-catalyzed phosphorylation sites on Tau without and with priming by PKA at the Ser-214 site. In the absence of priming, Tau can be phosphorylated by GSK3β at three sites (Ser(P)-404, Ser(P)-400, and Ser(P)-396) localized in the C terminus downstream of the four MTBRs (Fig. 5). Our results are hereby in agreement with previous in vitro studies of Tau phosphorylation by GSK3β using two-dimensional phosphopeptide mapping and phosphopeptide sequencing (32, 60). Kinetic analysis thereby shows that GSK3β phosphorylates Ser-404 at first and uses this phosphorylation event as a priming site for further modification of Ser-400 and Ser-396.

FIGURE 5.

Diagram of major phosphorylation sites identified in this study and resulting from the phosphorylation of prephosphorylated Tau at Ser-214 by GSK3β. The location of the priming site at Ser-214 (phosphorylated by PKA) is shown above the bar. The sites phosphorylated by GSK3β are shown below the bar. The diagram is a schematic representation of human Tau longest isoform present in the central nervous system (441 residues). P1 and P2 indicate the two proline-rich domains of Tau, and R indicates the four microtubule binding repeats.

Our kinetic study shows that Ser-404 is the first residue of Tau to be phosphorylated efficiently by GSK3β, and this remains such even when Ser-214 is phosphorylated by PKA (Fig. 3B). This phosphorylation is followed, however, by the subsequent and sequential phosphorylation on Ser-400, a non-proline-directed site that essentially needs the prephosphorylation of Ser-404. TauS404A indeed could not be phosphorylated at the Ser-400 site at all. After 6 h of incubation, the peak corresponding to Ser(P)-396 remains less intense compared with the peaks of Ser(P)-400 and Ser(P)-404 (Fig. 3D). We hence conclude that GSK3β is able to phosphorylate directly Ser-404 in vitro, and then sequentially the Ser-400 and Ser-396 positions in a backward reaction, with each phosphorylation generating a Ser-Xaa-Xaa-Xaa-Ser(P) motif. Although this latter scenario is equally in agreement with the work done in transfected cells (14), the main difference resides in the fact that GSK3β under our conditions is able to phosphorylate Tau at Ser-404 directly and efficiently. In vivo, other proline-directed kinases such as the cyclin-dependent protein kinase 5 might be more efficient to modify this Ser-404 site. GSK3β being able to catalyze the phosphate incorporation at nonprimed sites was previously reported for other substrates, including members of the Myc family of transcription factors (61). However, the nonprimed substrates mostly contain multiple acidic residues C-terminal to the phosphorylation site, which might substitute for the priming phosphorylation. Such is not obvious for Tau, where Pro-405 is followed by Arg-406 and His-407 and the first two acidic residues are Asp-418 and Asp-421. The molecular basis for this Ser-404 preference in Tau thus remains to be elucidated.

When Tau is prephosphorylated (primed) at Ser-214 by PKA (Ser(P)-214-Tau), in addition to the three phosphorylation sites described above (Ser(P)-396, Ser(P)-400, and Ser(P)-404), four phosphorylation sites corresponding to Ser(P)-195, Ser(P)-199, Thr(P)-205, and Ser(P)-210 are readily observable in the two-dimensional 1H-15N HSQC spectrum (Figs. 1 and 3). All these additional five sites of phosphorylation (including Ser(P)-214) are located in the proline-rich region of Tau. The priming by PKA hence generates a Ser-210-Xaa-Xaa-Xaa-Ser(P)-214 motif recognized by GSK3β (16) and leads to the phosphorylation of Ser-210 and the subsequent phosphorylation of Thr-205, Ser-199, and Ser-195 by a similar mechanism (Fig. 5). Our NMR study thus confirms that prephosphorylation of Tau by PKA makes additional and different sites accessible for phosphorylation by GSK3β (26).

Strittmatter et al. (46) were the first to report a direct interaction between Tau and apoE. By Western blotting in nonreductive conditions, they showed that Tau and apoE3 form a molecular complex of 105 kDa that resisted dissociation by boiling in 2% SDS but could be dissociated by boiling in the presence of 2-mercaptoethanol, a reducing agent. They mapped the interaction zones to the MTBR of Tau and the N-terminal receptor-binding domain of apoE3 (residues 1–191), corresponding to the fragment we have used in this study. Surprisingly, these authors considered that apoE3-Tau complex was probably not complexed through disulfide bond. The main argument for this was that the homodimer of apoE3, disulfide bridge linked through its single cysteine at position 112, still bound Tau. However, because Tau has two cysteine residues at position 291 and 322 located, respectively, in the R2 and R3 MTBR (Fig. 5), one cannot exclude that disulfide bridge shuffling occurred, with one Tau molecule capturing two apoE3 proteins through two distinct disulfide bridges. We actually repeated this experiment in the absence of a reducing agent, but we could not see significant changes in the NMR spectra of Tau before or after addition of apoE3. However, the relative proportion of the complex observed in the original Western blot compared with the noncomplexed proteins was low (46), so we cannot exclude from this negative result that our NMR sample did not contain a small fraction of Tau in complex with one or more apoE3 proteins.

The N-terminal domain of apoE(1–191) contains a high amount (12%) of Arg residues. This relative high content of Arg in apoE led to its initial name of “arginine-rich protein” and ready purification on a heparin column (42). Therefore, although we did not observe any interaction between apoE3 and the nonmodified Tau, we could not exclude that phosphorylation would promote such an electrostatic interaction. The cross-peaks corresponding to the phosphorylated residues in the sample modified by GSK3β after priming at Ser-214 by PKA (Ser(P)-214-Tau-GSK3) indeed shifted significantly upon addition of the N-terminal 22-kDa fragment of apoE, demonstrating an unambiguous interaction of apoE3(1–191) with Ser(P)-214-Tau-GSK3 (Fig. 4, right panel). Surprisingly, although Tau was phosphorylated to roughly the same stoichiometry but not at the same pattern by prolonged action of PKA alone (Tau-PKA), we found no interaction of apoE3(1–191) with Tau-PKA (Fig. 4, middle panel). Therefore, to interact with apoE in reductive conditions, Tau needs to be negatively charged by kinase(s) in a well defined pattern. GSK3β is able to produce such a phosphorylation pattern that consists in a successive Ser(P) or Thr(P) residue regularly spaced by approximately three amino acids. Three successive charges are sufficient to promote this interaction, as we did observe significant shifts in the C-terminal part of the protein that contains the Ser(P)-404/Thr(P)-400/Ser(P)-396 pattern. It remains to be seen whether these phosphorylation patterns, which do probably mimic the regular charge distribution that can be found on sulfated glycosamine glycans such as heparin, indeed interact with the putative heparin-binding site on the 4th helix of apoE (48, 62).

Our interaction data have been obtained with the 22-kDa N-terminal four-helix bundle of the apoE3 isoform. It is hence legitimate to ask whether the interaction might be modified when the apoE4 characterizing amino acid substitutions are present. Richey et al. (63), using an in situ binding assay, reported that apoE binds avidly to Tau, the principal component of the intracellular neurofibrillary tangles, but it also interacts with the amyloid-β peptide, the main component of the extracellular senile plaques. Nevertheless, they did not observe any difference in the binding between the different isoforms of apoE and the neurofibrillary tangles. Based on the fact that the x-ray structures of the three isoforms of the 22-kDa N-terminal fragment of apoE only vary in a subtle manner that does not involve the heparin-binding site (42), any difference in interaction between Tau and the N-terminal domains of the apoE isoforms is highly improbable. Indeed, the only changes are the reorientation of two side chains at positions 109 and 61 in the 3rd helix of the N-terminal domain. In the apoE4–22-kDa (in which Arg-112 replaces the Cys-112 of apoE3–22 kDa), the Glu-109 swings down to form a salt bridge with Arg-112. To accommodate this shift, Arg-61, which normally occupies the space above Arg-112, swings out of the way. As a result of this movement, an inter-domain salt bridge between Arg-61 in the N-terminal domain and Glu-255 in the C-terminal domain of apoE4 is formed that is absent in apoE3 and apoE2. ApoE4 because of this altered inter-domain organization will preferentially bind to triglyceride-rich very low density lipoproteins in human plasma (64, 65). This inter-domain interaction is equally observed in living neuronal cells (66) or in Arg-61 knock-in mice (67). ApoE3, which lacks the domain interaction, is predicted to have a more open structure, and it binds preferentially to phospholipid-rich high density lipoproteins (64, 65). We cannot exclude that the same altered inter-domain organization might also modulate the interaction of the 22-kDa bundle with the phospho-pattern on Tau. Interaction studies with full-length apoE constructs might shed further light on this.

The initial observation that apoE is synthesized by astrocytes, oligodendrocytes, activated microglia, and ependymal layer cells, but not by neurons in the brain, would tend to argue against the physiological relevance of the hereby described interaction between GSK3β phosphorylated Tau and apoE. However, later studies demonstrated that the central nervous system neurons also express apoE, albeit at lower levels than astrocytes (37, 68). Up-regulation of its expression level in neurons due to pathological stress, including cerebral infarction, has been reported (37, 39, 69, 70), although this protective mechanism may be overridden in individuals carrying the detrimental apoE4 allele (39, 71). Additional indirect evidence linking apoE, GSK3, and Tau comes from a recent interesting gene expression study showing that apoE and GSK3 are both differentially expressed in the entorhinal cortex where Tau pathology is thought to begin (72).

Finally, the recently discovered prion-like spreading of Tau fibrillization through the brain after injection of paired helical filaments points to the possibility that hyperphosphorylated Tau, once released in the extraneuronal space after breakdown of the neuron in which it originated (73, 74), would differentially interact with the apoE3/apoE4 isoforms. The apoE isoform might hence be a factor that modulates the rate of spreading of the tauopathy. Although much remains to be done, this perspective would indeed be an additional justification for the development of small molecules that interfere with the domain structure of the intact apoE.

In conclusion, our in vitro work confirms that GSK3β is able to phosphorylate Tau without priming at the Ser-404 proline-directed site and can continue to phosphorylate Tau upstream from this first site or another phosphorylation site in a primed manner. When Tau is primed by another kinase such as PKA or cyclin-dependent kinase, it creates at least one priming site from which GSK3β will phosphorylate Tau consecutively at upstream sites if a Ser or a Thr residue is present three amino acids away from this primed site. If the upstream Ser or Thr residues are followed by a proline, Tau can be phosphorylated by GSK3β at 3, 5, or 6 residues away from the previous phosphorylation site (see Table 1). This regular phosphorylation pattern generated by the GSK3β kinase generates a novel binding site for the apoE 22-kDa four-helix bundle, thereby highlighting again the importance for both GSK3β and apoE in AD.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof. Schwalbe (Frankfurt, Germany) for the PKA sample, and Dr. G. Divita for the GSK3β clone. The NMR facility used in this study was funded by the Région Nord-Pas de Calais (France), the CNRS, the University of Lille 1, and the Institut Pasteur de Lille.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. A and B.

- MTBR

- microtubule-binding repeat

- AD

- Alzheimer disease

- apoE

- apolipoprotein E.

REFERENCES

- 1.Buée L., Bussière T., Buée-Scherrer V., Delacourte A., Hof P. R. (2000) Brain Res. Brain Res. Rev. 33, 95–130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cleveland D. W., Hwo S. Y., Kirschner M. W. (1977) J. Mol. Biol. 116, 227–247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Avila J., Lucas J. J., Perez M., Hernandez F. (2004) Physiol. Rev. 84, 361–384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Braak H., Braak E., Ohm T., Bohl J. (1988) Stain Technol. 63, 197–200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Newell K. L., Hyman B. T., Growdon J. H., Hedley-Whyte E. T. (1999) J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 58, 1147–1155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Braak H., Alafuzoff I., Arzberger T., Kretzschmar H., Del Tredici K. (2006) Acta Neuropathol. 112, 389–404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hu Y. Y., He S. S., Wang X., Duan Q. H., Grundke-Iqbal I., Iqbal K., Wang J. (2002) Am. J. Pathol. 160, 1269–1278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hanger D. P., Hughes K., Woodgett J. R., Brion J. P., Anderton B. H. (1992) Neurosci. Lett. 147, 58–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lovestone S., Reynolds C. H., Latimer D., Davis D. R., Anderton B. H., Gallo J. M., Hanger D., Mulot S., Marquardt B., Stabel S., et al. (1994) Curr. Biol. 4, 1077–1086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brownlees J., Irving N. G., Brion J. P., Gibb B. J., Wagner U., Woodgett J., Miller C. C. (1997) Neuroreport 8, 3251–3255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Spittaels K., Van den Haute C., Van Dorpe J., Geerts H., Mercken M., Bruynseels K., Lasrado R., Vandezande K., Laenen I., Boon T., Van Lint J., Vandenheede J., Moechars D., Loos R., Van Leuven F. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 41340–41349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lucas J. J., Hernández F., Gómez-Ramos P., Morán M. A., Hen R., Avila J. (2001) EMBO J. 20, 27–39 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li T., Hawkes C., Qureshi H. Y., Kar S., Paudel H. K. (2006) Biochemistry 45, 3134–3145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li T., Paudel H. K. (2006) Biochemistry 45, 3125–3133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Woodgett J. R. (1990) EMBO J. 9, 2431–2438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dajani R., Fraser E., Roe S. M., Young N., Good V., Dale T. C., Pearl L. H. (2001) Cell 105, 721–732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.ter Haar E., Coll J. T., Austen D. A., Hsiao H. M., Swenson L., Jain J. (2001) Nat. Struct. Biol. 8, 593–596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fiol C. J., Mahrenholz A. M., Wang Y., Roeske R. W., Roach P. J. (1987) J. Biol. Chem. 262, 14042–14048 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fiol C. J., Haseman J. H., Wang Y. H., Roach P. J., Roeske R. W., Kowalczuk M., DePaoli-Roach A. A. (1988) Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 267, 797–802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fiol C. J., Wang A., Roeske R. W., Roach P. J. (1990) J. Biol. Chem. 265, 6061–6065 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang Q. M., Fiol C. J., DePaoli-Roach A. A., Roach P. J. (1994) J. Biol. Chem. 269, 14566–14574 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cole A., Frame S., Cohen P. (2004) Biochem. J. 377, 249–255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cross D. A., Alessi D. R., Cohen P., Andjelkovich M., Hemmings B. A. (1995) Nature 378, 785–789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ishiguro K., Omori A., Takamatsu M., Sato K., Arioka M., Uchida T., Imahori K. (1992) Neurosci. Lett. 148, 202–206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu S. J., Zhang J. Y., Li H. L., Fang Z. Y., Wang Q., Deng H. M., Gong C. X., Grundke-Iqbal I., Iqbal K., Wang J. Z. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 50078–50088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang J. Z., Wu Q., Smith A., Grundke-Iqbal I., Iqbal K. (1998) FEBS Lett. 436, 28–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sengupta A., Wu Q., Grundke-Iqbal I., Iqbal K., Singh T. J. (1997) Mol. Cell. Biochem. 167, 99–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Landrieu I., Leroy A., Smet-Nocca C., Huvent I., Amniai L., Hamdane M., Sibille N., Buée L., Wieruszeski J.-M., Lippens G. (2010) Biochem. Soc. Trans. 38, 1006–1011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Landrieu I., Lacosse L., Leroy A., Wieruszeski J. M., Trivelli X., Sillen A., Sibille N., Schwalbe H., Saxena K., Langer T., Lippens G. (2006) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128, 3575–3583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Scott C. W., Spreen R. C., Herman J. L., Chow F. P., Davison M. D., Young J., Caputo C. B. (1993) J. Biol. Chem. 268, 1166–1173 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Peterson D. W., Ando D. M., Taketa D. A., Zhou H., Dahlquist F. W., Lew J. (2010) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 2884–2889 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Godemann R., Biernat J., Mandelkow E., Mandelkow E. M. (1999) FEBS Lett. 454, 157–164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Spillantini M. G., Murrell J. R., Goedert M., Farlow M. R., Klug A., Ghetti B. (1998) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 7737–7741 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.De Strooper B., Vassar R., Golde T. (2010) Nat. Rev. Neurol. 6, 99–107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Corder E. H., Saunders A. M., Strittmatter W. J., Schmechel D. E., Gaskell P. C., Small G. W., Roses A. D., Haines J. L., Pericak-Vance M. A. (1993) Science 261, 921–923 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mahley R. W., Weisgraber K. H., Huang Y. (2006) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 5644–5651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Huang Y. (2006) Neurology 66, S79–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim J., Basak J. M., Holtzman D. M. (2009) Neuron 63, 287–303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mahley R. W. (1988) Science 240, 622–630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mahley R. W., Nathan B. P., Bellosta S., Pitas R. E. (1995) Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 6, 86–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Weisgraber K. H., Roses A. D., Strittmatter W. J. (1994) Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 5, 110–116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Weisgraber K. H. (1994) Adv. Protein Chem. 45, 249–302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lalazar A., Mahley R. W. (1989) J. Biol. Chem. 264, 8447–8450 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Weisgraber K. H., Rall S. C., Jr., Mahley R. W., Milne R. W., Marcel Y. L., Sparrow J. T. (1986) J. Biol. Chem. 261, 2068–2076 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Strittmatter W. J., Weisgraber K. H., Huang D. Y., Dong L. M., Salvesen G. S., Pericak-Vance M., Schmechel D., Saunders A. M., Goldgaber D., Roses A. D. (1993) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 90, 8098–8102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Strittmatter W. J., Saunders A. M., Goedert M., Weisgraber K. H., Dong L. M., Jakes R., Huang D. Y., Pericak-Vance M., Schmechel D., Roses A. D. (1994) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 91, 11183–11186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Amniai L., Barbier P., Sillen A., Wieruszeski J. M., Peyrot V., Lippens G., Landrieu I. (2009) FASEB J. 23, 1146–1152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Saito H., Dhanasekaran P., Nguyen D., Baldwin F., Weisgraber K. H., Wehrli S., Phillips M. C., Lund-Katz S. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 14782–14787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Langer T., Vogtherr M., Elshorst B., Betz M., Schieborr U., Saxena K., Schwalbe H. (2004) ChemBioChem 5, 1508–1516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Monteilhet C., Lachacinski N., Aggerbeck L. P. (1993) Gene 125, 223–228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Piotto M., Saudek V., Sklenár V. (1992) J. Biomol. NMR 2, 661–665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Weisemann R., Rüterjans H., Bermel W. (1993) J. Biomol. NMR 3, 113–120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bienkiewicz E. A., Lumb K. J. (1999) J. Biomol. NMR 15, 203–206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Smet C., Leroy A., Sillen A., Wieruszeski J. M., Landrieu I., Lippens G. (2004) ChemBioChem 5, 1639–1646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wishart D. S., Bigam C. G., Holm A., Hodges R. S., Sykes B. D. (1995) J. Biomol. NMR 5, 67–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lippens G., Wieruszeski J. M., Leroy A., Smet C., Sillen A., Buée L., Landrieu I. (2004) ChemBioChem 5, 73–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Verdegem D., Dijkstra K., Hanoulle X., Lippens G. (2008) J. Biomol. NMR 42, 11–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Laemmli U. K. (1970) Nature 227, 680–685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Selenko P., Frueh D. P., Elsaesser S. J., Haas W., Gygi S. P., Wagner G. (2008) Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 15, 321–329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hanger D. P., Seereeram A., Noble W. (2009) Expert Rev. Neurother. 9, 1647–1666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Grimes C. A., Jope R. S. (2001) Prog. Neurobiol. 65, 391–426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Dong J., Peters-Libeu C. A., Weisgraber K. H., Segelke B. W., Rupp B., Capila I., Hernáiz M. J., LeBrun L. A., Linhardt R. J. (2001) Biochemistry 40, 2826–2834 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Richey P. L., Siedlak S. L., Smith M. A., Perry G. (1995) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 208, 657–663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Dong L. M., Weisgraber K. H. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271, 19053–19057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dong L. M., Wilson C., Wardell M. R., Simmons T., Mahley R. W., Weisgraber K. H., Agard D. A. (1994) J. Biol. Chem. 269, 22358–22365 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Xu Q., Brecht W. J., Weisgraber K. H., Mahley R. W., Huang Y. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 25511–25516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Raffai R. L., Dong L. M., Farese R. V., Jr., Weisgraber K. H. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 11587–11591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Dekroon R. M., Armati P. J. (2001) Glia 33, 298–305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Boschert U., Merlo-Pich E., Higgins G., Roses A. D., Catsicas S. (1999) Neurobiol. Dis. 6, 508–514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Aoki K., Uchihara T., Sanjo N., Nakamura A., Ikeda K., Tsuchiya K., Wakayama Y. (2003) Stroke 34, 875–880 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Roses A. D. (1997) Neurobiol. Dis. 4, 170–185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Liang W. S., Dunckley T., Beach T. G., Grover A., Mastroeni D., Walker D. G., Caselli R. J., Kukull W. A., McKeel D., Morris J. C., Hulette C., Schmechel D., Alexander G. E., Reiman E. M., Rogers J., Stephan D. A. (2007) Physiol. Genomics 28, 311–322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Frost B., Jacks R. L., Diamond M. I. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 12845–12852 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Clavaguera F., Bolmont T., Crowther R. A., Abramowski D., Frank S., Probst A., Fraser G., Stalder A. K., Beibel M., Staufenbiel M., Jucker M., Goedert M., Tolnay M. (2009) Nat. Cell Biol. 11, 909–913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.