Abstract

Utilizing the Citrobacter rodentium-induced transmissible murine colonic hyperplasia (TMCH) model, we measured hyperplasia and NF-κB activation during progression (days 6 and 12 post-infection) and regression (days 20–34 post-infection) phases of TMCH. NF-κB activity increased at progression in conjunction with bacterial attachment and translocation to the colonic crypts and decreased 40% by day 20. NF-κB activity at days 27 and 34, however, remained 2–3-fold higher than uninfected control. Expression of the downstream target gene CXCL-1/KC in the crypts correlated with NF-κB activation kinetics. Phosphorylation of cellular IκBα kinase (IKK)α/β (Ser176/180) was elevated during progression and regression of TMCH. Phosphorylation (Ser32/36) and degradation of IκBα, however, contributed to NF-κB activation only from days 6 to 20 but not at later time points. Phosphorylation of MEK1/2 (Ser217/221), ERK1/2 (Thr202/Tyr204), and p38 (Thr180/Tyr182) paralleled IKKα/β kinetics at days 6 and 12 without declining with regressing hyperplasia. siRNAs to MEK, ERK, and p38 significantly blocked NF-κB activity in vitro, whereas MEK1/2-inhibitor (PD98059) also blocked increases in MEK1/2, ERK1/2, and IKKα/β thereby inhibiting NF-κB activity in vivo. Cellular and nuclear levels of Ser536-phosphorylated (p65536) and Lys310-acetylated p65 subunit accompanied functional NF-κB activation during TMCH. RSK-1 phosphorylation at Thr359/Ser363 in cellular/nuclear extracts and co-immunoprecipitation with cellular p65-NF-κB overlapped with p65536 kinetics. Dietary pectin (6%) blocked NF-κB activity by blocking increases in p65 abundance and nuclear translocation thereby down-regulating CXCL-1/KC expression in the crypts. Thus, NF-κB activation persisted despite the lack of bacterial attachment to colonic mucosa beyond peak hyperplasia. The MEK/ERK/p38 pathway therefore seems to modulate sustained activation of NF-κB in colonic crypts in response to C. rodentium infection.

Keywords: MAPKs, NF-kappa B, Protein Phosphorylation, RSK, siRNA, Colon, Hyperplasia, Progression, Regression

Introduction

The intestinal epithelium is a self-renewing tissue that represents a unique model for studying interconnected cellular processes such as proliferation, differentiation, cell migration, and carcinogenesis. Increased rates of proliferation have been described both as a precursor to cancer and as an integral part of the malignant transformation of the epithelium (1, 2) and are associated with a multitude of changes in cell signaling molecules and oncogenes (3–5). The proliferative zone of the normal colorectal mucosa is confined to the lower two-thirds of the colonic crypts, whereas in conditions of high risk of cancer, proliferating cells are observed throughout the whole length of the gland.

Pathogenic strains of Escherichia coli, including enteropathogenic E. coli and enterohemorrhagic E. coli, and a closely related mouse pathogen Citrobacter rodentium are classified as attaching and effacing pathogens based on their ability to adhere to intestinal epithelium, destroy microvilli, and induce actin-filled membranous protrusions called “pedestals” at the site of attachment. In the mouse colon, pedestal formation is associated with the formation of attaching and effacing lesions, breach of the epithelial barrier by the bacteria, and development of disease (6, 7).

Transmissible murine colonic hyperplasia (TMCH),2 caused by C. rodentium infection, is characterized by significant hyperplasia accompanied by expansion of the proliferative compartment throughout the longitudinal crypt axis (8, 9). The epithelial cell hyperproliferation that results from C. rodentium infection promotes the development of colonic adenomas after administration of the carcinogen 1,2-dimethylhydrazine (10). C. rodentium infection, in the absence of carcinogen administration, however, does not result in adenoma formation, and the mucosa reverts back to normal in 4–6 weeks.

C. rodentium colonizes preferentially the murine colon with over 109 bacteria present during the peak of infection. However, by day 21 post-oral challenge, C. rodentium is cleared from the gastrointestinal tracts of normal adult mice (11). Studies have shown that both innate and adaptive immune responses are required for immunity (11–15), with CD4 T-cell-dependent antibody responses believed to be central to clearance (12). Infection of mice with C. rodentium elicits a mucosal Th-1 immune response (16), very similar to mouse models of inflammatory bowel disease.

Immune and inflammatory responses in the gut and other immunocompetent tissues often involve the transcription factor NF-κB (17). Multiple stimuli, including cytokines, mitogens, environmental particles, toxic metals, and viral or bacterial products, activate NF-κB, mostly through IκB kinase (IKK)-dependent phosphorylation and subsequent degradation of its inhibitor(s), the IκB family of proteins (17). Activated NF-κB translocates to the nucleus, binds to its sequence recognition motif on promoters of target genes, and activates their transcription. The transcriptional activity of NF-κB is also controlled by various post-translational modifications, including phosphorylation (18, 19) and acetylation of the p65 subunit (20, 21).

Utilizing the TMCH model, we showed previously that it was associated with a robust activation of β-catenin and NF-κB in the colonic crypts. NF-κB activation in TMCH followed the canonical pathway, including IKKα/β phosphorylation and IκBα degradation (22), but it was also characterized by atypical mechanism that enhances NF-κB activity, including phosphorylation and acetylation of the p65 subunit of NF-κB.

The epithelial hyperplasia induced by C. rodentium infection in TMCH is resolved within 4–6 weeks after infection, but the transient hyperplastic axis induced by C. rodentium infection promotes the development of carcinogen-induced colorectal tumors. Because inflammation in the gut and activation of NF-κB are often associated with an increased susceptibility to colon cancer, we hypothesized that some signals that contribute to NF-κB activation in TMCH remain elevated/altered in the mucosa even after bacterial clearance. Therefore, in this study, we investigated the mechanistic basis of NF-κB activity during progression and regression of TMCH. We report that NF-κB activation was highest at peak hyperplasia, which coincided with maximal colonization of the colon by C. rodentium. However its activation, although reduced at later time points, remained elevated over that of normal mucosa after bacterial clearance and even when the hyperplasia was completely resolved. Activation of NF-κB at time points that coincided with bacterial colonization (TMCH progression) was regulated primarily through the canonical mechanism (IκBα phosphorylation and degradation). In contrast, sustained activity after bacterial clearance (TMCH regression) was regulated by persistent phosphorylation events of the MEK/MAPK,ERK/RSK-1 pathway. We conclude that C. rodentium infection caused irreversible changes in colonic epithelium that could contribute to increased susceptibility to carcinogenesis.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

TMCH and Diets

TMCH was induced in Helicobacter-free Swiss-Webster mice (15–20 g; Harlan Sprague-Dawley) by oral inoculation with a 16-h culture of C. rodentium, as described previously (9, 22–29). Age- and sex-matched control mice received sterile culture medium only. For dietary intervention, mice were randomized to receive either a control AIN-93 diet (30) or 6% pectin (catalog no. TD97202) and 1% calcium diet (catalog no. TD97200) synthesized by Harlan Teklad (Madison, WI). All dietary interventions began 3-days post-C. rodentium infection as described previously (23). Animals were euthanized at 0, 6, 12, 20, 27, and 34 days post-infection, and distal colons were removed. Animals on various dietary regimens were killed at 12 days post-infection, and their colons were harvested. To isolate crypts, distal colons were attached to a paddle and immersed in Ca2+-free standard Krebs-buffered saline (in mmol/liter: 107 NaCl, 4.5 KCl, 0.2 NaH2PO4, 1.8 Na2HPO4, 10 glucose, and 10 EDTA) at 37 °C for 10–20 min, gassed with 5% CO2, 95% O2. Individual crypt units were then separated from the submucosa/musculature by intermittent (30 s) vibration into ice-cold potassium gluconate HEPES saline (in mmol/liter: 100 potassium gluconate, 20 NaCl, 1.25 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, 10 glucose, and 5 sodium pyruvate), and 0.1% BSA. The isolated crypts were processed for biochemical and molecular assays as described previously (9, 22–29).

Cell Culture, Transfection, and Bacterial Infection

Young adult mouse colon (YAMC) cells were derived from colonic crypts from the Immortomouse®, such that they were conditionally immortalized with an SV40 large T-antigen with a temperature-sensitive IFNγ (interferon-γ)-inducible promoter (31). The YAMC cells were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 2 mm glutamine, 50 μg/ml gentamicin, 100 units/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, and 5 units/ml IFNγ in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2 at 33 °C. For experiments, cells were incubated at 33 °C in IFNγ-containing medium for 24 h and then transferred to 37 °C in IFNγ-free RPMI 1640 medium for 24 h. To delineate the role(s) of MAPK signaling in NF-κB activation in response to C. rodentium infection, YAMC cells (5 × 105) were seeded in 35-mm dishes and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h followed by growth in serum- and antibiotic-free medium for 24 h. The cells were then transfected with either 100 nmol/liter of scrambled siRNA or siRNAs specific for MEK1/2 (sc-35904 and sc-75906), ERK1/2 (sc-39308 and sc-35336), and p38α/β (sc-29434 and sc-39117) using 2–8 μl of transfection reagent (sc-29528) from Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc., Santa Cruz, CA. C. rodentium strain DBS 100 (ATCC catalog no. 51459TM) was grown under aerophilic conditions on Luria-Bertani (LB) agar plates for 24 h at 37 °C and cultured in LB broth overnight at 37 °C. RPMI, containing 0.45% glucose, was inoculated with a 1:20 dilution of a standard LB overnight culture and incubated for 2 h at 37 °C. Monolayers of 5 × 105 YAMC cells at ∼50% confluence or cells transfected with various siRNAs after 36 h were infected with C. rodentium at a multiplicity of infection (m.o.i.) of 90 or the medium alone (as a control) for 3 h at 37 °C in 5% CO2. After 3 h, medium was changed and replaced with fresh medium plus antibiotics to ensure complete absence of live bacteria. Medium was tested negative for colony formation after 24 h (data not shown). At 24, 48, and 72 h, cellular/nuclear proteins were extracted and processed for either Western blotting or DNA binding assay as described elsewhere.

TLR4/NF-κB/SEAPorter Activity Assay

To directly assess the role of toll-like receptor (TLR)-4 in NF-κB activation in response to C. rodentium infection, we utilized a stably co-transfected HEK 293 cell line (IML-104, Imgenex Corp., San Diego) that expresses full-length TLR4 and the secreted alkaline phosphatase (SEAP) reporter gene under the transcriptional control of an NF-κB response element (hereby designated as HEK 293-reporter cell line). The functionality of this cell line has been validated by measuring SEAP levels after LPS (lipopolysaccharide; a component of the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria) stimulation. The HEK 293 cells were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 4.5g/liter glucose, 10% FBS, 4 mm l-glutamine, 1 mm sodium pyruvate, 100 units/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, 10 μg/ml blasticidin, and 500 μg/ml G418 (geneticin). Cells were infected with C. rodentium at an m.o.i. of 90 for 3 h, washed, and incubated in fresh medium. The SEPorter activity was measured with the Imgenex SEPorter assay kit (catalog no. 10055K) as described by the manufacturer. An increase in SEAP levels indicates activation of NF-κB.

RNA Isolation and PCR

For measuring expression levels of CXCL-1/KC in the colonic crypts, cDNA was synthesized from total RNA by using superscript II and random primers. Specific gene products were identified by performing semiquantitative PCR. Primer sequences are provided in supplemental Table 1. The PCR products were separated by PAGE and visualized by ethidium bromide staining of the gels under UV light. Gel data were recorded with the Bio-Rad FluorS Imaging System, and relative densities of the bands were determined with Quantity One software (Bio-Rad). Gene expression was normalized against actin.

Electrophoretic Mobility Shift and DNA Binding Assays

Crypt nuclear extracts were prepared from normal or Citrobacter-infected mouse distal colon essentially as described previously (22–29). 10 μg of nuclear extract in 10 μl of buffer was mixed with 2 μg of poly(dI-dC) and 1 μg of BSA to a final volume of 19 μl. After a 15-min incubation on ice, 1 μl of [γ-32P]ATP end-labeled and double-stranded NF-κB consensus oligonucleotide (TGAGGGGACTTTCCCAGGC) was added to each reaction and incubated at room temperature for an additional 15 min. The reaction products were separated on a 4% native polyacrylamide 0.5%× Tris borate/EDTA gel and analyzed by autoradiography. Supershift antibodies (1 μl) were included in the binding reaction as indicated (all supershift antibodies were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology) (26). For DNA binding assays, relative levels of activated p65 NF-κB in nuclear extracts of normal or Citrobacter-infected mouse distal colonic crypts were measured using the TransAM p65 NF-κB Chemi Transcription Factor Assay kit from Active Motif (Carlsbad, CA) (27).

Immunoprecipitation and Western Blotting

For immunoprecipitation studies, crypt cytosolic extracts were normalized for protein concentration and pre-cleared for 1 h at 4 °C with 30 μl of protein A-coated Sepharose beads. Immunoprecipitation was carried out at 4 °C by incubating the fractions overnight with antibody recognizing p90RSK-1. Immune complexes were captured by incubation with 50 μl of protein A/G-Sepharose beads for 2 h at 4 °C. Control experiments were performed by carrying out immunoprecipitations in the presence of the immunizing peptides or with control IgG antisera. The immunoprecipitated proteins were recovered by boiling the Sepharose beads in 2× SDS sample buffer.

Total crypt cellular extracts, subcellular fractions (30–100 μg protein/lane), or immunoprecipitated proteins were subjected to SDS-PAGE and electrotransferred to nitrocellulose membrane. The efficiency of electrotransfer was checked by back staining gels with Coomassie Blue and/or by reversible staining of the electrotransferred protein directly on the nitrocellulose membrane with Ponceau S solution. No variability in transfer was noted. De-stained membranes were blocked with 5% nonfat dried milk in TBS (20 mm Tris-HCl and 137 mm NaCl, pH 7.5) for 1 h at room temperature (21 °C) and then overnight at 4 °C. Immunoantigenicity was detected by incubating the membranes for 1–2 h with the appropriate primary antibodies (0.5–1.0 μg/ml in Tris-buffered saline (TBS) containing 0.1% Tween 20 (TBS/Tween); Sigma). After washing, membranes were incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse or anti-rabbit secondary antibodies and developed using the ECL detection system (Amersham Biosciences) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Immunofluorescence (IMF) and Immunohistochemistry

IMF or immunohistochemistry studies for anti-LPS as a surrogate to detect the presence of C. rodentium in the colonic mucosa was performed on 5-μm-thick paraffin sections from distal colons of normal and TMCH mice (days 6–34) utilizing the HRP-labeled polymer conjugated to secondary antibody using Envision+ System-HRP (3,3′-diaminobenzidine; DakoCytomation, Carpinteria, CA) with microwave accentuation as described previously (9, 22, 27, 28). Slides were washed and incubated with 4–6-diamidino-2-phenylindole for 5 min at room temperature to stain the nuclei. The visualization was carried out either via fluorescent or light microscopies, respectively. Controls included either omission of primary antibody or detection of endogenous IgG staining pattern with goat anti-mouse or anti-rabbit IgG (Calbiochem).

RESULTS

Colonic Epithelial Cell Proliferation Accompanies NF-κB Activation during Progression and/or Regression Phases of Hyperplasia

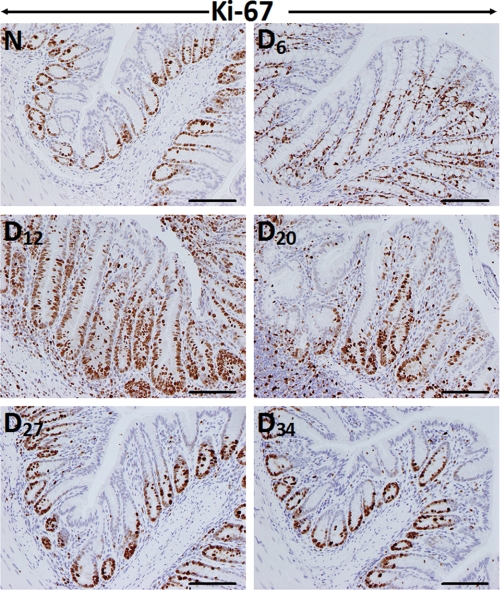

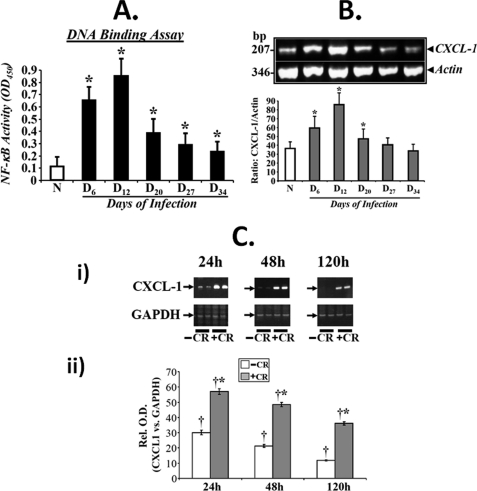

To determine the effect of C. rodentium infection on colonic crypt hyperplasia, we stained the distal colonic sections from Swiss-Webster outbred mice for Ki-67 as a marker of proliferation by immunohistochemistry. In normally proliferating crypts, only cells at the base exhibited nuclear staining (Fig. 1). At day 6 and particularly at day 12 TMCH, intense nuclear immunoreactivity extended throughout the longitudinal crypt axis (Fig. 1). Intense Ki-67 nuclear immunoreactivity persisted until day 27 before returning to base line by day 34 (Fig. 1). We define in this study days 6 and 12 post-infection as “TMCH progression” and days 20–34 post-infection as “TMCH regression.” When NF-κB activity in the distal colonic crypt nuclear extracts were measured via DNA binding assay, the activity increased reproducibly during TMCH progression, declined 40% at day 20, and then plateaued off at days 27 and 34. However, the residual activity, even at day 34, however, was 2-fold higher than uninfected control (Fig. 2A). It needs to be emphasized that even though we have previously reported the mechanism of NF-κB activation during progression of TMCH (22), we considered it extremely critical to include these time points to understand how progression and regression phases of hyperplasia associated with TMCH affect NF-κB activity in colonic crypts in vivo. To further investigate the effect of NF-κB activation on downstream signaling, we focused on chemokine (CXC motif) ligand 1 (CXCL-1/KC), one of the targets of NF-κB signaling and a cognate ligand for CXC chemokine receptor CXCR-2. Time course studies paralleled NF-κB activation kinetics to a certain extent, wherein expression of CXCL-1 increased significantly at days 6 and 12 post-infection, declined at day 20, but was still detectable at days 27 and 34 albeit at lower levels (Fig. 2B). As proof-of-principle, we used YAMC cells to study sustained activation of NF-κB in response to C. rodentium infection. YAMC cells were infected with C. rodentium at 90:1 m.o.i. for 3 h at 37 °C, washed to remove bacteria, and incubated in fresh medium with antibiotics for 24, 48, and 120 h. Expression analysis revealed significant increase in CXCL-1 levels at 24 and 48 h compared with uninfected control with sustained overexpression even at 120 h (Fig. 2C). Data from three separate experiments are presented as a bar graph in Fig 2C, panel ii, as a ratio of GAPDH in the samples. Because CXCL-1 is a downstream target of NF-κB signaling, these findings clearly indicate that sustained NF-κB activation may indeed be regulating expression of CXCL-1 over an extended period both in vivo and in vitro.

FIGURE 1.

Crypt hyperplasia as measured by Ki-67 staining. Immunohistochemical labeling of Ki-67 as a marker of proliferation in paraffin-embedded sections was prepared from the distal colons of uninfected normal (N) and C. rodentium-infected (days 6–34) mice. D, day. Bar, 75 μm (n = 5).

FIGURE 2.

A, NF-κB activity measured via DNA binding assay. Crypt nuclear extracts were prepared from normal (N) and days (D) 6–34 post-infected mice, and the presence of activated NF-κB p65 in the nuclear extracts was examined by utilizing Trans AM NF-κB p65 Chemi Transcription Factor Assay kit from Active Motif. Significant increases in NF-κB activity was recorded at days 6 and 12 with sustained activation at days 20, 27, and 34 of TMCH (n = 3; p < 0.05). B, expression of downstream target for NF-κB, CXCL-1/KC, during TMCH. Total RNA was extracted from colonic crypts isolated from normal or days 6–34 post-infected mice. CXCL-1/KC expression was measured via semi-quantitative RT-PCR using actin mRNA as loading control (upper panel). Lower panel represents a bar graph showing relative levels of CXCL-1/KC normalized to actin (p < 0.05, n = 3). C, measurement of CXCL-1/KC expression in YAMC cells in vitro. YAMC cells (5 × 105) were either treated with (+C. rodentium) or without (−C. rodentium) C. rodentium was 90:1 m.o.i. for 3 h. Cells were washed thoroughly to remove bacteria and incubated in fresh medium containing antibiotics for indicated periods. Total RNA was examined for the expression of CXCL-1/KC via RT-PCR, and GAPDH was used as loading control. A significant increase in the level of CXCL-1 was observed at 24 and 48 h post-infection with sustained expression even at 120 h compared with uninfected control (C, panel i; n = 3). C, panel ii, representative bar graph showing the relative expression levels of CXCL-1 normalized to GAPDH. *, p < 0.05 versus control (†, n = 3).

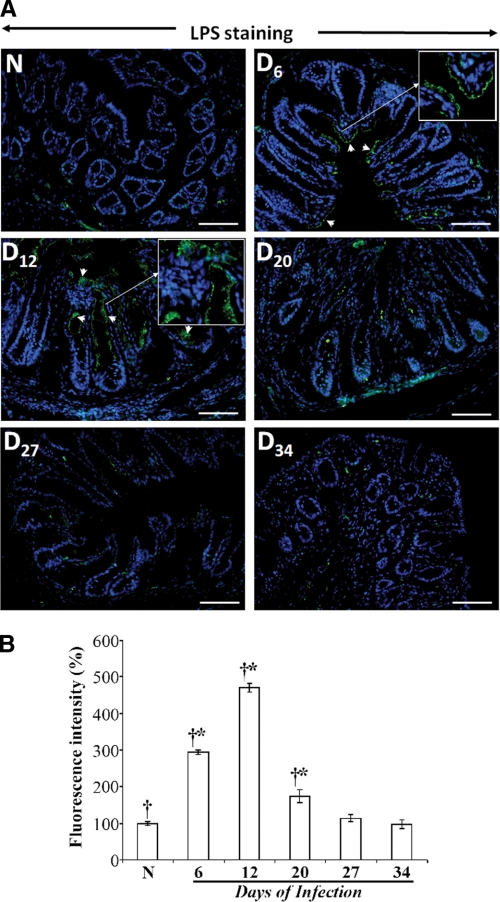

To rule out the possibility that the NF-κB activity during regression of TMCH may be a result of prolonged bacterial attachment to the colonic mucosa, we performed LPS IMF in deparaffinized sections from distal colon at different time points as a surrogate to detect Citrobacter attachment to the colonic mucosa. These IMF studies showed robust bacterial binding to the surface epithelial cells at days 6 and 12, wherein bacterial binding could be seen along the entire length of the colonic crypts (Fig. 3A). However, at days 20–34, almost complete loss of bacterial binding to the surface mucosa was observed (Fig. 3A) consistent with an earlier report of bacterial clearance at day 21 post-infection (11). The bar graph in Fig. 3B represents the percent increase in fluorescence intensity for LPS staining at the indicated time points. Thus, although some residual uptake of bacteria by cells of the immune system at later time points cannot be ruled out, we conclude that despite the lack of detectable bacterial attachment to colonic mucosa beyond day 12, NF-κB remains active albeit at reduced levels during TMCH regression.

FIGURE 3.

A, immunofluorescence detection of LPS as a surrogate for Citrobacter presence in the distal colon isolated from uninfected normal (N) and days (D) 6–34 (D6–D34) post-infected mice. Paraffin-embedded sections were deparaffinized, subjected to antigen retrieval, and incubated overnight at 4 °C with anti-LPS antibody. Following incubation with secondary antibody conjugated with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC), slides were analyzed by fluorescent microscopy using Axiophot 2 microscope (Carl Zeiss, Germany). Arrows indicate bacterial binding to the colonic mucosa in the sections. Insets represent enlarged images to show specific bacterial attachment to the colonic mucosa at days 6 and 12 post-C. rodentium infection. B, representative bar graph showing percent change in the fluorescence intensity at indicated time points. *, p < 0.05 versus control (†, n = 3).

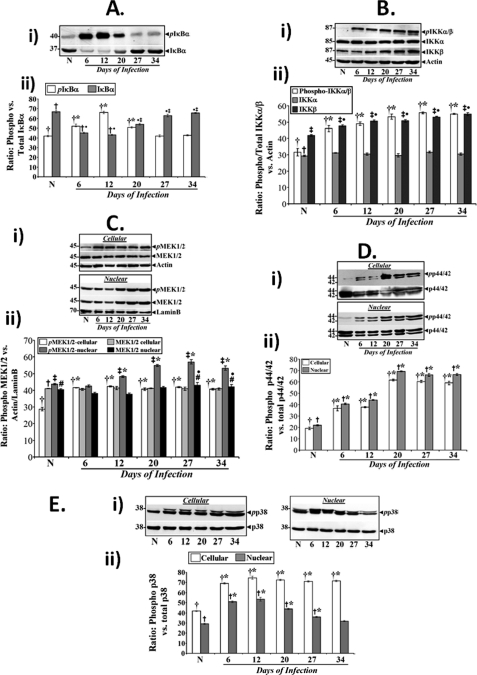

We have shown recently that NF-κB activation by C. rodentium infection during progression of TMCH occurs via the canonical pathway, including phosphorylation of cellular IKKα/β and phosphorylation and degradation of IκBα (22). In this study, we assessed/compared these molecular events during progression and regression of TMCH. As shown in Fig. 4A, phosphorylation of IκBα at Ser32/36 increased at days 6, 12, and 20 compared with uninfected control but decreased to base-line levels at later time points. Because phosphorylation of IκBα results in its degradation, we next measured total IκBα at these time points. Indeed, substantial decrease in the abundance of total IκBα was recorded at days 6 and 12 as reported earlier (22). At days 20, 27, and 34, however, total IκBα was restored to base line suggesting that NF-κB activity seen at these time points (Fig. 2A) may be independent of IκBα degradation. The bar graph in Fig. 4A, panel ii, represents the ratio of phosphorylated versus total IκBα from three independent experiments. Because these changes in phosphorylation and degradation of IκBα depend on activation of IKKα/β, we also analyzed the phosphorylation status of IKKα/β during TMCH, and we found that relative levels of phosphorylated cellular IKKα (Ser176/180) and IKKβ (Ser177/181) increased substantially at day 6 and remained elevated throughout progression and regression of TMCH (Fig. 4B). Although the level of unphosphorylated IKKα did not change during TMCH, IKKβ levels progressively increased during TMCH regression, but the significance of this remains unknown. The bar graph in Fig. 4B, panel ii, represents the ratio of phosphorylated and total IKKα/β levels normalized to actin (n = 3). These studies suggest that activated IKKs in the hyperproliferating crypts regulate IκBα function during progression but not during regression of TMCH.

FIGURE 4.

Both canonical and atypical pathways contribute toward NF-κB activation in colonic crypts in vivo. A, panel i, relative levels of phosphorylated and total IκBα in the colonic crypt cellular extracts prepared from uninfected normal (N) and days 6–34 post-infected mice. A, panel ii, representative bar graph showing the ratio of IκBα phosphorylated at Ser32/36 versus total IκBα. *, p < 0.05 versus control (†); ●, p < 0.05 versus control (†); ‡, p < 0.05 versus day 12 (†●, n = 3). B, panel i, both IKKα and -β undergo increased phosphorylation in vivo. Western blot analysis of total crypt extracts prepared from the distal colon of normal and days 6–34 post-infected mice revealed significant and sustained increases in phosphorylation of both IKKα and -β, compared with control (upper panel) although the levels of unphosphorylated IKKs did not change during TMCH (lower panels). B, panel ii, representative bar graph showing relative levels of phosphorylated and total IKKα/β versus actin. *, p < 0.05 versus control (†, n = 3); ●, p < 0.05 versus control (‡, n = 3). C–E, changes in the relative levels of MEK1/2, p44/42-ERK, and p38 during TMCH. Crypt cellular extracts prepared from the distal colons of normal and days 6–34 post-infected mice were analyzed for the relative abundance of MEK1/2 (C, panel i), p44/42-ERK (D, panel i), and p38 (E, panel i) proteins by Western blot analysis. Relative levels of phospho-MEK1/2 (pMEK1/2), p44/42 ERK (pp44/42), and p38 (pp38) exhibited dramatic increases in both cellular and nuclear extracts at peak hyperplasia, and the levels remained elevated during regression phase (days 20–34) of hyperplasia. Bar graphs in C, panel ii (*, p < 0.05 versus control (†), ‡*, p < 0.05 versus control (‡); ●, p < 0.05 versus control (#; n = 3)); D, panel ii (*, p < 0.05 versus control (†, n = 3); †*, p < 0.05 versus control (†, n = 3)); and E, panel ii (*, p < 0.05 versus control (†, n = 3); †*, p < 0.05 versus control (†, n = 3)) represent relative abundance of phosphorylated cellular/nuclear proteins normalized to actin/lamin B.

Signaling via Components of the TLR4 Pathway

Based on a recent report that TLR signaling contributes to inflammation induced by C. rodentium and to identify signaling cascades responsible for NF-κB activation during TMCH, we next examined sequential changes in the components of the TLR pathway in the colonic crypts in vivo. Signaling cascades initiated by engagement of TLRs with their ligands require many adaptor and accessory proteins, including MyD88, TRAF-6, and TAK-1, which are directly or indirectly involved in activating downstream kinases such as MEK1/2, ERK, and p38 (32). When cellular extracts were probed with antibodies for MyD88, TRAF-6 and TAK-1, all three proteins were detected in the colonic crypts (supplemental Fig. 1, A–C). However, we did not detect any change in their cellular abundance during the course of TMCH as was revealed by densitometry following normalization with actin (n = 3). Cellular and nuclear levels of phosphorylated and hence activated MEK1/2 (Ser217/221; pMEK1/2) and p44/42 ERK (Thr202/Tyr204; pp44/42 ERK) on the other hand, increased substantially at day 6 and remained elevated throughout the course of progression and regression of TMCH (Fig. 4, C, panel i, and D, panel i) as was revealed by densitometry following normalization with actin or lamin B, respectively (Fig. 4, C, panel i, and D, panel ii; n = 3). This sustained elevation in the levels of cellular and nuclear pMEK1/2 or pp44/42 ERK correlated with the sustained phosphorylation status of IKKα/β (see Fig. 4B) as well as with sustained activation of NF-κB at these time points (see Fig. 2A). Similarly, cellular levels of phosphorylated p38 (Thr180/Tyr182; pp38) increased significantly at day 6 and remained elevated throughout TMCH (Fig. 4E, panel i). Nuclear pp38 levels, however, increased at days 6–20 but returned to base line at days 27 and 34 (Fig. 4E, panel i) as was revealed by densitometry following normalization with total p38 (Fig. 4E, panel ii; n = 3). Thus, phosphorylated and activated pMEK1/2, pp44/42 ERK, and pp38 may be regulating NF-κB activity both during progression and regression of TMCH.

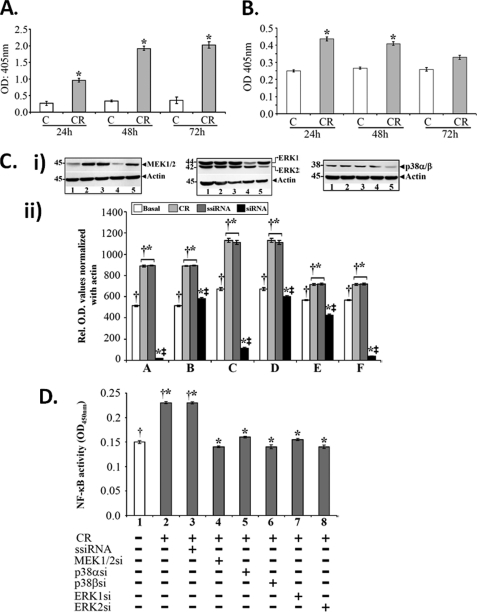

We next utilized a HEK 293-reporter cell line to definitively establish the role of TLR4 in NF-κB activation in response to C. rodentium infection in vitro. HEK 293 cells in general do not express TLR4 (33), and therefore, utilization of a TLR4-reporter cell line allows direct assessment of TLR4 function during LPS-induced activation of the NF-κB signaling pathway. The HEK 293-reporter cells were infected with C. rodentium at 90:1 m.o.i. for 3 h at 37 °C, washed to remove bacteria, and incubated in fresh medium with antibiotics for 24, 48, and 72 h. Measurement of SEAP in the spent medium via the SEAPorter assay kit revealed sequential increases in SEAP levels at 24, 48, and 72 h indicating NF-κB activation via TLR4 in response to C. rodentium infection (Fig. 5A). At the same time, SEAP levels in the cell extract sequentially declined thereby correlating with its secretion in the medium (Fig. 5B).

FIGURE 5.

Signaling via TLR4 and MEK/ERK/p38 regulates NF-κB activity in response to C. rodentium infection. A and B, functional analysis of TLR4. TLR4/NF-kB/SEAPorter HEK293 cells were infected with C. rodentium (CR) for 3 h, washed to remove bacteria, and SEAP levels were measured in the spent medium (A) and cell extracts (B) via SEAP assay kit. Significant and sequential increases in SEAP levels indicating NF-κB activation were recorded at 24, 48, and 72 h in the spent medium with concomitant decreases in the cell extracts at these time points (*, p < 0.05 versus uninfected control; n = 3). C, control. C, effect of siRNAs on MEK, ERK, and p38 levels in vitro. YAMC cells in culture were transiently transfected either with scrambled siRNA (ssiRNA) or siRNAs specific to MEK1/2, ERK1/2, and p38α/β. The transfected cells were treated with or without C. rodentium for 3 h, washed to remove bacteria, and processed for Western blotting after 48 h. Samples in various lanes are as follows: 1, basal; 2, C. rodentium; 3, C. rodentium + scrambled siRNA; 4, C. rodentium + siRNA (MEK1, ERK1, and p38α); 5, C. rodentium + siRNA (MEK2, ERK2, and p38β). Please note that siRNAs to MEK1, ERK1/2, and p38β, in particular, caused significant reduction in the levels of these proteins (C, panel i). C, panel ii, representative bar graph showing relative levels of MEK1/2 (A and B), ERK1/2 (C and D), and p38α/β (E and F) normalized to actin. *, p < 0.03 versus control (†, n = 3); ‡, p < 0.05 versus C. rodentium/scrambled siRNA (†*; n = 3). D, effect of blocking MEK/ERK/p38 on NF-κB activity. DNA binding assay was performed in YAMC cells transfected either with scrambled siRNA (ssiRNA) or siRNA specific for each kinase and infected with or without C. rodentium as described above. Various lane assignments are as follows: 1, basal; 2, C. rodentium-infected; 3, C. rodentium + scrambled siRNA; 4–8; C. rodentium + siRNAs for MEK1 (4), p38α (5), p38β (6), ERK1 (7), and ERK2 (8), respectively. *, p < 0.05 versus control (†, n = 3).

To assess the role of MEK, ERK and p38 in regulating NF-κB activity in response to C. rodentium infection, YAMC cells were transfected with either control or specific siRNAs for these kinases and infected with C. rodentium as described under “Experimental Procedures.” As can be seen from Fig. 5C, panel i, C. rodentium infection caused significant increase in cellular levels of MEK1/2, ERK1/2, and p38α/β, thereby correlating with in vivo data (see Fig. 4C). Cells transfected with siRNAs to MEK1, ERK1, and p38β exhibited almost complete loss of these proteins (Fig. 5C, panel i), whereas cellular levels of MEK2, ERK2, and p38α also decreased in response to intervention with specific siRNAs. The bar graph in Fig. 5C, panel ii, shows relative changes in the levels of these kinases when normalized with actin (n = 3).

To determine whether these interventions affected the NF-κB activity in response to C. rodentium infection, nuclear extracts prepared from control or specific siRNA-treated YAMC cells were subjected to DNA binding assay as described elsewhere (22, 27). As expected, C. rodentium infection led to significant increase in NF-κB activity compared with uninfected control (Fig. 5D). Interestingly, although siRNAs to all three MAPKs inhibited the NF-κB activity (Fig. 5D), isoform-specific siRNAs to MEK1, ERK2, and p38β were relatively more effective in reversing the activation of NF-κB in response to C. rodentium infection (Fig. 5D).

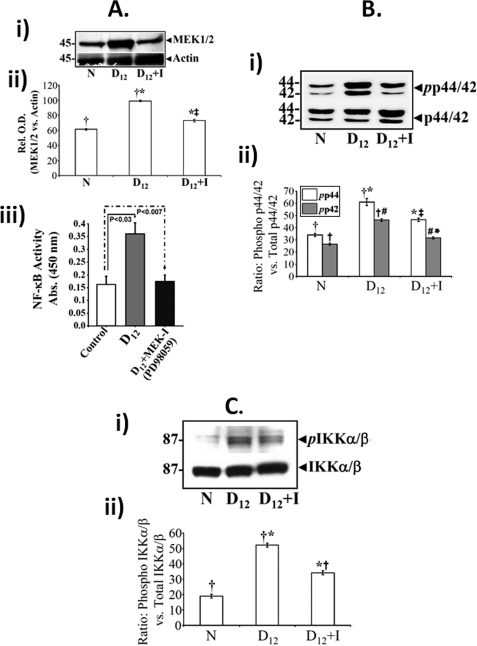

To further assess the role of MEK/ERK pathway in NF-κB activation, both uninfected (data not shown) and C. rodentium-infected mice were treated the specific MEK inhibitor, PD98059, for 10 days starting 2 days post-C. rodentium infection as described under “Experimental Procedures.” PD98059 significantly blocked increases in relative levels of MEK1/2 at peak hyperplasia as was revealed by densitometry following normalization with actin (Fig. 6A, panels i and ii) and inhibited NF-κB activity compared with untreated mice (Fig. 6A, panel iii) thereby confirming the role of MEK in NF-κB activation during TMCH. To examine downstream pathways affected because of MEK inhibition, we next examined the phosphorylation status of both ERK1/2 and IKKα/β in colonic crypts. MEK1/2 inhibition in vivo led to significant blockade of phosphorylated ERK1/2 along with phosphorylated IKKα/β (Fig. 6, B and C). The bar graphs in Fig. 6B, panel ii, and C, panel ii, represent the ratio of phosphorylated versus total ERK1,2/IKKα,β from three independent experiments. Given that IKKα/β catalyzes phosphorylation and subsequent degradation of IκBα, inhibition of IKKα/β may have directly affected the NF-κB activity in response to MEK1/2 inhibition at peak hyperplasia.

FIGURE 6.

A, effect of MEK1/2 inhibition on NF-κB activity in vivo. Swiss-Webster mice were divided into two groups and injected once a day for 10 days with either control or specific MEK1/2 inhibitor, PD98059 (see “Experimental Procedures”). 2 h after the last injection, colonic crypts were isolated and fractionated into cytosolic and nuclear extracts. Representative Western blots for total MEK1/2 in the colonic crypt cellular extracts prepared from uninfected normal (N), day 12 (D12), and day 12 +,inhibitor (D12+I)-treated mice (A, panel i). A, panel ii, representative bar graph showing relative levels of MEK1/2 when normalized to actin. *, p < 0.05 versus control (†, n = 3); ‡, p < 0.05 versus day 12 (†*, n = 3). A, panel iii, DNA binding assay. PD98059 significantly inhibited NF-κB activation, measured in a DNA binding assay with nuclear extracts prepared from day 12 + inhibitor (D12+I)-treated mice, compared with levels measured in either control or day 12 (D12) mice alone. Each bar represents mean ± S.E. values from three measurements from three separate mice. p values (<0.03 for day 12 and <0.007 for day 12 + inhibitor), respectively, versus corresponding control values. B, panel i, and C, panel i, representative Western blots showing relative levels of phospho (pp44/42) and total p44/42-ERK (B) and phospho (pIKKα/β) and total IKKα/β (C) in the colonic crypt cellular extracts prepared from uninfected normal (N), day 12 (D12), and day 12 + inhibitor (D12+I)-treated mice. Bar graphs in B, panel ii, and C, panel ii, represent relative levels of phosphorylated and total p44/42 ERK (B, panel ii; *, p < 0.05 versus control (†; n = 3); *‡, p < 0.05 versus day 12 (†*, n = 3); †#, p < 0.05 versus control (†; n = 3); #*, p < 0.05 versus day 12 (†#; n = 3)) and phosphorylated and total IKKα/β (C, panel ii; *, p < 0.05 versus control (†, n = 3); *†, p < 0.05 versus day 12 (†*, n = 3)) normalized to total proteins.

p65 Phosphorylation, Acetylation, and Interaction with RSK-1 Accompany NF-κB Activation in Vivo

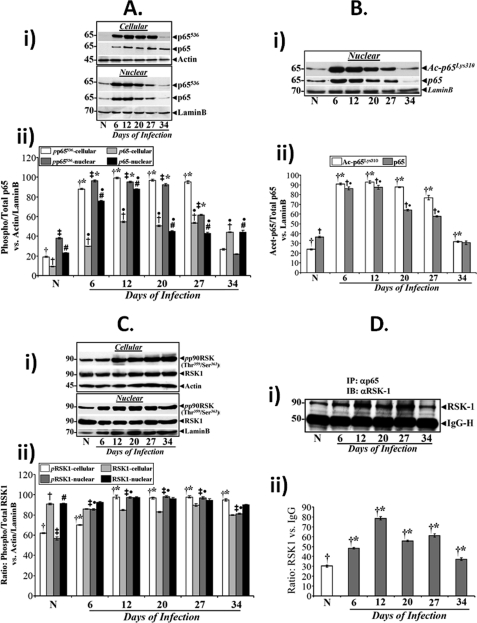

Besides the phosphorylation and subsequent degradation of IκBα, protein kinases are also required for optimal NF-κB activation by targeting functional domains of NF-κB proteins themselves. Phosphorylation of the p65 subunit for example, enhances its ability to recruit histone acetyltransferases such as cAMP-response element-binding protein-binding protein and p300 (20, 21). We therefore investigated the phosphorylation status of p65-NF-κB to determine whether post-translational modification of this subunit contributed toward sustained activation of NF-κB during regression of hyperplasia. Utilizing an antibody that detects phosphorylation of p65 at Ser536 (p65536), we evaluated this phosphorylation event in cellular and nuclear extracts during TMCH. Levels of both cellular and nuclear p65536 along with total p65 increased reproducibly at days 6 and 12 of TMCH compared with uninfected control, remained elevated until day 27, and then declined by day 34 (Fig. 7A, panel i). The bar graph in Fig. 7A, panel ii, represents the ration of phosphorylated/total p65 versus actin/lamin B from three independent experiments. To assess the acetylation status of p65 at these time points, we utilized an antibody that detects endogenous levels of p65 only when it is acetylated at lysine 310. Indeed, the kinetics of this acetylation event of p65 (Fig. 7B) paralleled that of p65536 (Fig. 7A) suggesting that phosphorylation of p65 at Ser536 may have facilitated its acetylation at lysine 310. These studies clearly show that NF-κB activation during the progression and regression phases of hyperplasia is associated with significant phosphorylation, nuclear translocation, and acetylation of p65 subunit ensuring the functional activation of NF-κB.

FIGURE 7.

Phosphorylation and acetylation of p65 subunit underlies functional activation of NF-κB during TMCH. Relative levels of phosphorylated (p65536) and total p65 subunit in the cellular and nuclear (A, panel i) extracts prepared from uninfected normal (N) and days 6–34 post-infected mice were determined by Western blotting. A, panel ii, representative bar graph showing relative levels of phosphorylated and total p65 subunit in the cellular and nuclear extracts when normalized to actin/lamin B. Bars, *, p < 0.05 versus control (†, n = 3); ●, p < 0.05 versus control (†, n = 3); ‡*, p < 0.05 versus control (‡, n = 3); ●#, p < 0.05 versus control (#, n = 3). B, nuclear accumulation of acetylated p65 subunit overlaps p65536 kinetics. Relative levels of p65 subunit acetylated at lysine 310 (Ac-p65Lys310) along with total p65 were measured in the nuclear extracts prepared from the distal colons of normal and days 6–34 post-infected mice (B, panel i). B, panel ii, representative bar graph showing relative levels of acetylated/total p65 versus lamin B. *, p < 0.05 versus control (†, n = 3); ●, p < 0.05 versus control (†, n = 3). C, phosphorylation status of RSK-1 during TMCH. C, panel I, relative levels of RSK-1 phosphorylated at Thr359/Ser363 (pp90RSK) and total RSK-1 were measured in the cellular and nuclear extracts prepared from normal and days 6–34 post-infected mice by Western blotting. C, panel ii, representative bar graph showing relative levels of phosphorylated and total p65 subunit in the cellular and nuclear extracts when normalized to actin/lamin B. Bars, *, p < 0.05 versus control (†, n = 3); ‡●, p < 0.05 versus control (‡, n = 3). D, panel I, co-immunoprecipitation: Crypt cellular extracts prepared from the distal colons of normal and days 6–34 post-infected mice were co-immunoprecipitated with anti-p65 and blotted with antibody to RSK-1. Lower panel represents IgG heavy chain. D, panel ii, representative bar graph showing relative levels of normalized RSK-1. *, p < 0.05 versus control (†, n = 3).

We previously reported that NF-κB-p65 subunit co-immunoprecipitated with RSK-1 and that p65/RSK-1 interaction kinetics overlapped with increases in p65 phosphorylation at Ser536 (22). In this study, we utilized an antibody that detects endogenous levels of RSK-1 only when phosphorylated at Thr359/Ser363 to directly measure activation status of RSK-1 during TMCH. Relative levels of RSK-1 phosphorylated at Thr359 and Ser363 (pp90RSK-1) increased in both cellular and nuclear extracts during the time course of TMCH (Fig. 7C, panel i) and overlapped to certain extent with the changes in p65536 kinetics (Fig. 7A). The bar graph in Fig. 7C, panel ii, represents the ration of phosphorylated/total RSK-1 versus actin/lamin B from three independent experiments. RSK-1 also co-immunoprecipitated with p65 subunit, and the kinetics paralleled increases in p65536 during the time course of TMCH (Fig. 7D, panels i and ii). Thus, RSK-1/p65 interaction may be integral to sustained NF-κB activation during TMCH.

Dietary Intervention to Block NF-κB in Vivo

We have shown previously that pectin (a soluble fiber and SCFA delivery system to the colon) abrogates TMCH by blocking increases in cell census (23). SCFA butyrate has been shown to modulate NF-κB activity in human colonic epithelial cell line (34). Because pectin provides SCFAs to the colon, we aimed at investigating whether pectin would duplicate the effects of butyrate in vivo.

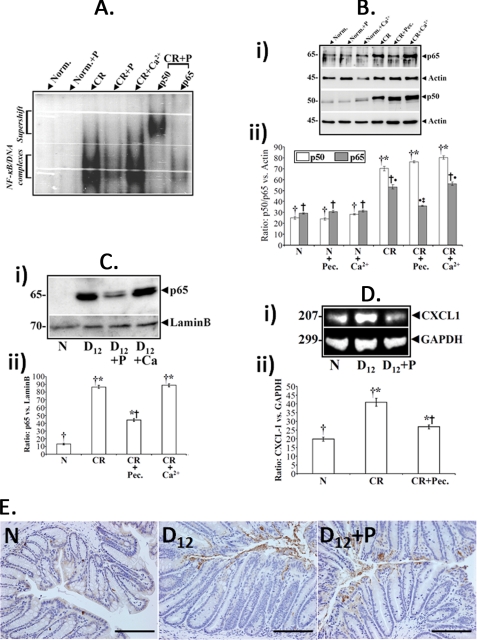

Both 6% pectin and 1% calcium diets abrogated C. rodentium-induced hyperplasia (supplemental Fig. 2). To examine the effects of these dietary ingredients on NF-κB, NF-κB activity in nuclear extracts was measured by EMSA using nuclear extracts prepared from uninfected normal (N) or TMCH crypts (D12) isolated from mice receiving either regular chow or high pectin and high calcium diets, respectively. Pectin in the absence of TMCH had no effect on NF-κB (Fig. 8A). High pectin diet in the presence of TMCH, however, inhibited increases in NF-κB activity, but the high calcium diet had no effect (Fig. 8A). Supershift studies were performed by p50 and p65 antibodies, respectively. Although antibody to p50 supershifted the NF-κB signal, no supershift was observed with antibody to p65 (Fig. 8A) suggesting that pectin may specifically be targeting the p65 subunit of NF-κB. When the abundance of NF-κB subunits was measured in isolated crypts under different dietary conditions, we found that high pectin diet blocked increases in p65 cellular abundance (Fig. 8B, panel i), whereas p50 subunit abundance was not affected. High calcium diet (1%), on the other hand, did not alter the abundance of any of these proteins (Fig. 8B, panel i). Data from three separate mouse samples are presented as a bar graph in Fig. 8B, panel ii, as ratio of p50/p65 versus actin.

FIGURE 8.

Pectin inhibits NF-κB activity in vivo. A, effect of dietary intervention on NF-κB activity in vivo. NF-κB activity in the nuclear extracts were measured via EMSA in uninfected normal (N) or TMCH crypts (D12) isolated from mice receiving either regular chow or high pectin and high calcium diets, respectively. EMSA showing relative levels of activated NF-κB in colonic crypts from mice treated as indicated: Norm., noninfected (N); P, pectin; CR, C. rodentium-infected (D12). Last 2 lanes, p50 but not the p65 subunit, supershifted with the indicated NF-κB subunit antibodies in the C. rodentium + pectin (CR+P)-treated crypt nuclear extracts. Pectin in the absence of TMCH, had no effect on NF-κB. B, effect of dietary intervention on subunit expression. Crypt cellular extracts prepared from mice treated as indicated in legends to A were subjected to Western blotting with antibodies to p50 and p65 subunits, respectively. B, panel ii, representative bar graph showing relative levels of p50/p65 when normalized to actin. Bars, *, p < 0.05 versus control (†, n = 3); †●, p < 0.05 versus control (†, n = 3); ●‡, p < 0.05 versus C. rodentium (†●, n = 3). C and D, effect of dietary intervention on nuclear translocation of NF-κB subunits and expression of downstream target CXCL-1. Crypt nuclear extracts prepared as described in legend to A were subjected to Western blot analysis with antibody to p65 subunit. 6% pectin but not high calcium diet blocked p65 nuclear translocation (C, *, p < 0.05 versus control (†, n = 3); *†, p < 0.05 versus C. rodentium (†*, n = 3)). This led to significant inhibition of NF-κB activity (see A) and subsequent down-regulation of downstream target gene CXCL-1 (D, *, p < 0.05 versus control (†, n = 3); *†, p < 0.05 versus C. rodentium (†*, n = 3)) in the pectin-treated samples (n = 3). E, effect of pectin treatment on bacterial binding. Paraffin-embedded sections prepared from uninfected (N) and pectin-untreated or pectin-treated 12-days post-infected mouse distal colons were stained with antibody to LPS and counter-stained with hematoxylin to label the nuclei (n = 3; bar, 100 μm).

Because NF-κB activation requires nuclear translocation of p65, we next examined the effect of either high pectin or high calcium diet on nuclear translocation of p65 during TMCH. Significant increases in nuclear p65 were observed in infected mice on control or high calcium diet (Fig. 8C, panel i) as reported previously (22). In contrast, high pectin diet substantially decreased the abundance of nuclear p65 (Fig. 8C, panel i); the bar graph in Fig. 8C, panel ii, shows relative changes in levels of p65 versus lamin B from three mouse samples. This led to significant inhibition of NF-κB activity (Fig. 8A) and subsequent down-regulation of the downstream target gene CXCL-1 (Fig. 8D, panel i). The bar graph in Fig. 8D, panel ii, shows relative changes in CXCL-1 in relation to GAPDH (n = 3). Finally, to ascertain that pectin did not interfere with the ability of C. rodentium to bind to colonic mucosa, the tissue sections prepared from the distal colons of untreated or pectin-treated mice were stained with antibody to LPS. As shown in Fig. 8E, sections prepared from infected mice fed a control diet and high pectin diet exhibited significant bacterial binding to the colonic mucosa at a 12-day post-infection when compared with uninfected colon thereby confirming that this dietary change did not alter the C. rodentium attachment to colonic epithelium. Thus, pectin inhibits NF-κB activity by modulating p65 cellular abundance and nuclear translocation eventually affecting expression of downstream target genes.

DISCUSSION

TMCH, at least in the context of outbred genetic background, is a self-limited disease and contrasts with the ongoing proliferation that occurs in colonic neoplasia. However, development of colonic hyperplasia during TMCH is associated with an increased susceptibility to carcinogenesis in response to either a chemical mutagen (10) or in the absence of a functional adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) gene product (35). As a noninvasive organism, C. rodentium lends itself to the study of how the host recognizes and eliminates pathogens in the intestinal lumen and distinguishes such pathogens from the normal flora. Signaling via TLR4 has been implicated in the protective host responses that lead to clearance of C. rodentium infection (14, 33). Thus, innate immune signaling in limiting mucosal damage is necessary to protect the host, whereas an adaptive immune response develops resulting in bacterial clearance.

NF-κB is an important component of the innate and adaptive immunity. Utilizing the C. rodentium-induced TMCH model, we showed previously that C. rodentium infection is associated with a dramatic increase in NF-κB activation at peak hyperplasia, and this activation involved both phosphorylation and degradation of IκBα and phosphorylation and nuclear translocation of p65 subunit (22). In this study, we report that activation of NF-κB at time points that coincided with bacterial colonization (TMCH progression) was regulated primarily through the canonical pathway (IκBα phosphorylation and degradation). In contrast, we also observed sustained NF-κB activity after bacterial clearance (TMCH regression) that was regulated by persistent phosphorylation events of the MEK/ERK/p38/RSK-1 pathway. These changes correlated with hyperplasia of the colonic crypts wherein sustained Ki-67 immunoreactivity was recorded between days 6 and 27 followed by decline by day 34. Thus, continuous bacterial attachment or colonization per se is not required to keep NF-κB active for an extended period, which corroborates well with the noninvasive nature of C. rodentium (37). Instead, the C. rodentium-induced cytokinetic changes due to intracellular signaling as discussed below may be sufficient to regulate NF-κB activity for an extended period of time.

In response to diverse stimuli, IKK, a complex composed of the regulatory IKKγ (NF-κB essential modulator) subunit and two enzymatically active subunits IKKα and IKKβ, undergoes phosphorylation at consensus phosphorylation sites (Ser176 and Ser180 in IKKα and Ser177 and Ser181 in IKKβ) leading to its activation. Canonical IKK activation involves IKKβ and results in phosphorylation of IκBα, dissociation of IκBα from NF-κB, ubiquitination, and proteasomal degradation. We observed significant increases in the relative levels of phosphorylated IKKs not only at days 6 and 12 of TMCH leading to increases in IκBα phosphorylated at Ser32/36 and proteasomal degradation, as reported earlier (22), but the increased levels were sustained at days 20, 27, and 34 of TMCH. However, NF-κB activation at later time points was probably less dependent on IκBα degradation despite the continued presence of phosphorylated and hence activated IKKs at these time points.

Positional cloning work and subsequent biochemical analyses have revealed that TLR4 transduces the LPS signal, alerting the host to infection by Gram-negative bacteria. The interaction of TLR4 with its ligand LPS results in the recruitment of the adaptor molecule MyD88 and phosphorylation of the interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase (38). Phosphorylated IRAK1 undergoes ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation, which is followed by TRAF-6 activation (38). TRAF-6, in association with the proteins TAB-1 (transforming growth factor-β-activated kinase-1 (TAK-1)-binding protein-1) and TAB-2, leads to the activation of the MAPK pathway following ubiquitination of both TRAF-6 and TAK-1 (39). TAK-1 then activates both MEK1,2/ERK and p38/JNK pathways, which catalyzes activation of both the IKK complex and NF-κB. In this study, utilizing a TLR4-reporter cell line, we established the direct involvement of TLR4 in NF-κB activation in response to C. rodentium infection (see Fig. 5, A and B), and we also detected all three major proteins involved in signaling via TLR4 as follows: MyD88, TRAF-6, and TAK-1 in the colonic crypts. Despite C. rodentium infection being unable to affect cellular changes in these proteins, their expression in colonic crypts suggests an important role for these proteins in transducing the TLR4 signaling in response to C. rodentium infection resulting in the activation of the MEK/ERK/MAPK pathway.

Three major MAPK cascades have been described in mammalian cells, the ERK, p38, and the JNK pathways. They are linked to activation by LPS and subsequent cytokine gene expression. In this study, we observed significant increases in cellular and nuclear levels of phosphorylated and hence activated MEK1/2, ERK, and p38 at peak hyperplasia. Interestingly, the levels of these kinases did not decline with regressing hyperplasia suggesting that they may be regulating sustained levels of IKKα/β and NF-κB activity during TMCH. To that end, two different approaches were undertaken to establish direct involvement of these MAPKs in NF-κB activation in response to C. rodentium infection as follows. (i) An in vitro approach wherein YAMC cells were transfected with siRNAs specific to MEK1/2, ERK1/2, and p38α/β, and NF-κB activity was examined. siRNAs specific to all three MAPKs significantly inhibited NF-κB activity, although isoform-specific inhibition was also recorded for MEK1, ERK2, and p38β MAPKs. (ii) An in vivo approach wherein a proof-of-principle experiment was performed in vivo with an inhibitor of MEK1/2 and ERK pathway to further validate in vitro findings. MEK1/2 inhibitor PD98059 blocked increases in phosphorylated MEK1/2 and ERK leading to significant inhibition of NF-κB activity in the day 12 crypts. Because siRNA to MEK1 was more effective in reversing the effects of C. rodentium-induced NF-κB activation in vitro (see Fig. 5C), it is tempting to speculate that MEK1 and not MEK2 may be predominantly involved in regulating NF-κB activity in colonic crypts. We showed previously that inhibition of NF-κB via the proteasomal inhibitor VelcadeTM did not abrogate hyperplasia (22). Moreover, preliminary studies in TLR4−/− mice show significant hyperplasia of the colonic crypts in response to C. rodentium infection despite attenuated NF-κB activity. Hyperplasia in these mice is driven by β-catenin-mediated increases in downstream targets, cyclin D1 and c-Myc.3 This study clearly suggests that β-catenin is not downstream to the TLR4/MEK/ERK pathway and that β-catenin rather than NF-κB regulates crypt hyperplasia in response to C. rodentium infection (9, 22). Nevertheless, the MEK1,2/ERK pathway may be critical in regulating NF-κB activity at least at peak hyperplasia. Similarly, suppressor of cytokine signaling-1 (SOCS-1), a negative regulator of NF-κB activity in the TLR4/ERK/p38 pathway, failed to completely abolish NF-κB activity in regressing hyperplasia (data not shown). These studies suggest that the ERK/p38 pathway may have overwhelmed the inhibitory cues to maintain NF-κB in an activated state in regressing crypts. These findings suggest that ERK/p38 pathway may have overwhelmed the inhibitory cues to maintain NF-κB in an activated state in regressing crypts. Clearly, more studies are needed to understand how the sustained levels of MEK/ERK/p38 are regulated in colonic crypts in response to C. rodentium infection in vivo. Nonetheless, the sustained activation of NF-κB due to MEK1/ERK1,2/p38β may eventually prime the hyperplastic colonic mucosa toward neoplasia in response to a second hit. Given that NF-κB is an obvious target for newer treatments to block the inflammatory response in instances where this process becomes chronic or dysregulated, targeting these kinases to regulate NF-κB could be useful in blocking prolonged activation of this pathway. It is important to keep in mind, however, that it may not be feasible to block the NF-κB pathway for prolonged periods because NF-κB plays an important role in the maintenance of protective immunity. Based on our studies, short term treatment with pathway-specific inhibitors may reduce such potential side effects and may enhance the efficacy of cancer chemotherapy and reduce abnormal cytokine production eventually blocking growth and progression of colon carcinogenesis.

Phosphorylation and Acetylation of p65 Subunit May Regulate Sustained Activation of NF-κB in Vivo

Phosphorylation of the p65 subunit plays a key role in determining both the strength and duration of the NF-κB-mediated transcriptional response (40, 41). Sites of phosphorylation reported to date are serines 276 and 311 in the Rel homology domain, and serines 468, 529, and 536 in the transactivation domain. Moreover, acetylation of the phosphorylated p65 subunit at Lys310 is essential for the transcriptional activity of NF-κB (40, 42, 43). We previously showed significant increases in phosphorylation of the p65 subunit at Ser536 (pp65536), which translocated to the nucleus and interacted with transcriptional co-activator cAMP-response element-binding protein-binding protein. In this study, the relative levels of both cellular and nuclear p65536 along with total p65 increased reproducibly at days 6 and 12 of TMCH and remained elevated until day 27 before declining by day 34 (see Fig. 7). p65 subunit also underwent significant acetylation at lysine 310 (Ac-p65Lys-310) at peak hyperplasia with sustained levels even at day 34 of TMCH (see Fig. 7B) suggesting that phosphorylation of p65 subunit at Ser536 in the colonic crypts may have facilitated recruitment of transcriptional co-activator cAMP-response element-binding protein-binding protein with intrinsic acetyltransferase activity to catalyze acetylation of p65 at lysine 310. Because phosphorylation at Ser536 also reduces the ability of p65 to bind IκBα in cell lines (44), both pp65536 and Ac-p65Lys310 rather than degradation of IκBα may be regulating sustained and functional activation of NF-κB in the colonic crypts beyond peak hyperplasia.

The p90 RSKs are a family of serine/threonine kinases that lie at the terminus of the ERK pathway (45–48). In mammals, four isoforms are known, RSK-1 to RSK-4. Each one has two catalytically functional kinase domains, the N-terminal kinase domain and C-terminal kinase domain as well as a linker region between the two. The N-terminal kinase domain is responsible for phosphorylation of exogenous substrates, and the C-terminal kinase domain and linker region regulate RSK activation (45, 46, 48). In quiescent cells, ERK binds to the docking site in the C terminus of RSK (49–51). Upon mitogen stimulation, ERK is activated by its upstream MAPK/ERK kinase, MEK1/2, as discussed above. The active ERK phosphorylates Thr359/Ser363 of RSK-1 in the linker region and Thr573 in the C-terminal kinase domain activation loop. Through a series of trans- and autophosphorylations, RSK is finally activated. We also observed significant and sustained increases in relative levels of both cellular and nuclear RSK-1 phosphorylated at Thr359 and Ser363 as well as co-immunoprecipitation of RSK-1 with the p65 subunit, which paralleled p65536 kinetics during the time course of TMCH. Thus, RSK-1 and not necessarily IKKα/β seems to be involved in phosphorylating p65 at Ser536 both at peak hyperplasia and more importantly when hyperplasia is regressing thereby regulating sustained activation of NF-κB in colonic crypts. It remains to be determined whether MEK1,2/ERK inhibition in vivo affected RSK-1 levels or activation in colonic crypts and how sustained activation of RSK-1 is regulated during TMCH. Recent studies have shown that Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus infection activates multiple MAPK pathways and promotes interaction with RSKs (52–54). More importantly, the ERK/RSK activation was sustained both during Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus primary infection and during reactivation from latency (52, 53, 55, 56). Mechanistically, Kuang et al. (56) showed that ORF-45, an immediate early and also virion tegument protein of Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus, interacted with RSK-1 and strongly stimulated its kinase activity. ORF-45 also increased the association of RSK-1 with ERK and protected them from dephosphorylation, causing their sustained activation (56). Whether a similar mechanism exists for sustained phosphorylation and/or activation of pp44/42 ERK, pp90RSK-1, or pp38 during TMCH remains to be determined and will be investigated in future studies.

Dietary Intervention to Block NF-κB in Vivo

Given the diverse processes involved in activating the NF-κB pathway, it is not surprising that a plethora of chemical inhibitors or biologics have been utilized and implicated in blocking activation of this pathway (57). Butyrate and other SCFAs are generated by the bacterial metabolism of dietary fiber and are putative modulators of the beneficial effects of fiber on the colon. Intracellular mechanisms that mediate the beneficial aspects of butyrate, however, are not well elucidated. We showed previously that 6% pectin diet, as a butyrate delivery system to the colon, abrogated increases in β-catenin abundance and reduced its downstream effectors, cyclin D1 and c-Myc, thereby abrogating hyperplasia of colonic crypts in response to C. rodentium infection (23). Several natural compounds, including polyphenols, have been reported to suppress NF-κB activity and are suggested to be useful for the inhibition of cancer cell growth (57). For any intervention to be successful, however, it is critical to pinpoint the exact cell type responding to a particular intervention. In this study, we discovered that a 6% pectin diet significantly inhibited NF-κB activity in the epithelial cells of the colonic crypts of day 12 animals by blocking increases in cellular levels of the p65 subunit and preventing its nuclear import without altering the ability of C. rodentium to bind to colonic mucosa. To our knowledge, this is the first demonstration of a particular cell type responding to a dietary intervention. It has been shown by Yin et al. (58) that butyrate inhibits NF-κB by suppressing degradation of IκBα and cellular proteasome activity in vitro. Because bacterial fermentation of pectin generates butyrate and other SCFAs and our own observation that pectin treatment of infected animals increased generation of butyrate in the colon by 2-fold (data not shown), it is likely that pectin-induced inhibition of NF-κB activity in vivo is mediated by butyrate. The butyrate suppression of IκBα degradation and proteasome activity may derive from its ability to inhibit histone deacetylases as is reported previously (58). Thus, modulation of both β-catenin (23) and NF-κB pathways by luminal factors such as pectin and SCFAs during TMCH may be a physiologically relevant mechanism to regulate colonic crypt hyperplasia. Because a decrease in intestinal proliferation is associated with a reduced colon cancer risk, treatments or diets that increase colonic levels of SCFAs, such as pectin, may be beneficial for preventing the risk for colon carcinogenesis.

TMCH in Context

TMCH induced by C. rodentium causes significant hyperproliferation and hyperplasia of the distal colonic crypts and increases the risk of subsequent neoplasia. In adult animals, infection is typically self-limited, and lifelong immunity is provided after recovery. In a recent study (36), it has been shown that NF-κB-p50−/− mice failed to promote bacterial clearance despite higher levels of anti-Citrobacter IgG and IgM, due to lack of NF-κB activation in these mice in response to C. rodentium infection suggesting that non-NF-κB-dependent defenses are insufficient to control C. rodentium infection. Thus, sustained activation of NF-κB during TMCH, driven by a combination of both IκBα phosphorylation and degradation (at peak hyperplasia; Fig. 9) and MEK1,2/ERK/p38-dependent regulation of p65/RSK-1 interaction (both during progression and regression; Fig. 9), besides working in tandem with β-catenin to regulate proliferatory activity of the colonic crypts, may be better suited to regulate bacterial clearance thereby keeping TMCH a self-limiting infection. From a disease standpoint, however, NF-κB has been reported to become constitutively active in tumor cells, and therefore blocking NF-κB can cause tumor cells to stop proliferating, to die, or to become more sensitive to the action of anti-tumor agents. In that context, the TMCH model with its entire repertoire of activated Wnt/β-catenin (9, 26) and MEK/ERK/p38/NF-κB pathways (Fig. 9) basically mimics human conditions wherein C. rodentium-induced cytokinetic alterations in colonic epithelia may promote mucosal priming for neoplasia. Thus, methods of blocking NF-κB signaling in vivo either via chemical inhibitors (such as shown in Fig. 6) or through dietary intervention (see Fig. 8) have therapeutic implications in cancer and in inflammatory diseases.

FIGURE 9.

Proposed mechanism of NF-κB activation in response to CR infection in vivo. In response to infection of Swiss Webster mice by C. rodentium, intracellular signaling via MEK/ERK and p38 pathways may lead to sustained levels of these kinases thereby affecting NF-κB activity in the colonic crypts. The solid arrows represent pathways that are more apparently active in the colonic crypts, and broken arrows represent pathways most likely contributing toward NF-κB activation in vivo. A and B represent possible mechanism for activation of NF-κB either during progression or both during progression and regression of hyperplasia. Both MEK1/2 inhibitor PD98059 and 6% pectin diet can significantly inhibit NF-κB activity in the colonic crypts in response to C. rodentium infection.

Supplementary Material

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants R01 CA131413 (to S. U.) and R01 CA 97959, CA114264 (to P. S.), and R21 CA131936 (to S. P.) from the NCI.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Table 1 and Figs. 1 and 2.

P. Chandrakesan, I. Ahmed, and S. Umar, manuscript in preparation.

- TMCH

- transmissible murine colonic hyperplasia

- IKK

- IκBα kinase

- NF-κB

- nuclear factor-κB

- RSK

- ribosomal S6 kinase

- SCFA

- short-chain fatty acid

- YAMC

- young adult mouse colon

- IMF

- immunofluorescence

- m.o.i.

- multiplicity of infection

- SEAP

- secreted alkaline phosphatase

- TLR

- toll-like receptor.

REFERENCES

- 1.Risio M., Lipkin M., Candelaresi G., Bertone A., Coverlizza S., Rossini F. P. (1991) Cancer Res. 51, 1917–1921 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vogelstein B., Kinzler K. W. (1994) Cold Spring Harbor Symp. Quant. Biol. 59, 517–521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peifer M. (1995) Trends Cell Biol. 5, 224–229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stewart D. B., Nelson W. J. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272, 29652–29662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blobe G. C., Obeid L. M., Hannun Y. A. (1994) Cancer Metastasis Rev. 13, 411–431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McDaniel T. K., Kaper J. B. (1997) Mol. Microbiol. 23, 399–407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Luperchio S. A., Schauer D. B., (2001) Microbes. Infect. 3, 333–340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barthold S. W., Coleman G. L., Bhatt P. N., Osbaldiston G. W., Jonas A. M. (1976) Lab. Anim. Sci. 26, 889–894 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sellin J. H., Wang Y., Singh P., Umar S. (2009) Exp. Cell Res. 315, 97–109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barthold S. W., Jonas A. M. (1977) Cancer Res. 37, 4352–4360 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mundy R., MacDonald T. T., Dougan G., Frankel G., Wiles S. (2005) Cell. Microbiol. 7, 1697–1706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bry L., Brenner M. B. (2004) J. Immunol. 172, 433–441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bry L., Brigl M., Brenner M. B. (2006) Infect. Immun. 74, 673–681 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lebeis S. L., Bommarius B., Parkos C. A., Sherman M. A., Kalman D. (2007) J. Immunol. 179, 566–577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maaser C., Housley M. P., Iimura M., Smith J. R., Vallance B. A., Finlay B. B., Schreiber J. R., Varki N. M., Kagnoff M. F., Eckmann L. (2004) Infect. Immun. 72, 3315–3324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Higgins L. M., Frankel G., Douce G., Dougan G., MacDonald T. T. (1999) Infect. Immun. 67, 3031–3039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Karin M., Ben-Neriah Y. (2000) Annu. Rev. Immunol. 18, 621–663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhong H., SuYang H., Erdjument-Bromage H., Tempst P., Ghosh S. (1997) Cell 89, 413–424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang D., Baldwin A. S., Jr. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 29411–29416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen Lf., Fischle W., Verdin E., Greene W. C. (2001) Science 293, 1653–1657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen L. F., Mu Y., Greene W. C. (2002) EMBO J. 21, 6539–6548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang Y., Xiang G. S., Kourouma F., Umar S. (2006) Br. J. Pharmacol. 148, 814–824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Umar S., Morris A. P., Kourouma F., Sellin J. H. (2003) Cell Prolif. 36, 361–375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Umar S., Sellin J. H., Morris A. P. (2000) Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 279, G223–G237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Umar S., Wang Y., Sellin J. H. (2005) Oncogene 24, 6709–6718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Umar S., Wang Y., Morris A. P., Sellin J. H. (2007) Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 292, G599–G607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Umar S., Sarkar S., Cowey S., Singh P. (2008) Oncogene 27, 5599–5611 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Umar S., Sarkar S., Wang Y., Singh P. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 22274–22284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Umar S., Sellin J. H., Morris A. P. (2000) Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 278, G765–G774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reeves P. G., Nielsen F. H., Fahey G. C., Jr. (1993) J. Nutr. 123, 1939–1951 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Whitehead R. H., VanEeden P. E., Noble M. D., Ataliotis P., Jat P. S. (1993) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 90, 587–591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kawai T., Akira S. (2010) Nat. Immunol. 11, 373–384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Khan M. A., Ma C., Knodler L. A., Valdez Y., Rosenberger C. M., Deng W., Finlay B. B., Vallance B. A. (2006) Infect. Immun. 74, 2522–2536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Inan M. S., Rasoulpour R. J., Yin L., Hubbard A. K., Rosenberg D. W., Giardina C. (2000) Gastroenterology 118, 724–734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Newman J. V., Kosaka T., Sheppard B. J., Fox J. G., Schauer D. B. (2001) J. Infect. Dis. 184, 227–230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dennis A., Kudo T., Kruidenier L., Girard F., Crepin V. F., MacDonald T. T., Frankel G., Wiles S. (2008) Infect. Immun. 76, 4978–4988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.MacDonald T. T., Frankel G., Dougan G., Goncalves N. S., Simmons C. (2003) Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 293, 87–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Medzhitov R., Preston-Hurlburt P., Kopp E., Stadlen A., Chen C., Ghosh S., Janeway C. A., Jr. (1998) Mol. Cell 2, 253–258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ninomiya-Tsuji J., Kishimoto K., Hiyama A., Inoue J., Cao Z., Matsumoto K. (1999) Nature 398, 252–256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen L. F., Greene W. C. (2004) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 5, 392–401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Viatour P., Merville M. P., Bours V., Chariot A. (2005) Trends Biochem. Sci. 30, 43–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kiernan R., Brès V., Ng R. W., Coudart M. P., El Messaoudi S., Sardet C., Jin D. Y., Emiliani S., Benkirane M. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 2758–2766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen L. F., Williams S. A., Mu Y., Nakano H., Duerr J. M., Buckbinder L., Greene W. C. (2005) Mol. Cell. Biol. 25, 7966–7975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bohuslav J., Chen L. F., Kwon H., Mu Y., Greene W. C. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 26115–26125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Roux P. P., Blenis J. (2004) Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 68, 320–344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hauge C., Frödin M. (2006) J. Cell Sci. 119, 3021–3023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Carriere A., Ray H., Blenis J., Roux P. P. (2008) Front. Biosci. 13, 4258–4275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Anjum R., Blenis J. (2008) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 9, 747–758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gavin A. C., Nebreda A. R. (1999) Curr. Biol. 9, 281–284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Roux P. P., Richards S. A., Blenis J. (2003) Mol. Cell. Biol. 23, 4796–4804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Smith J. A., Poteet-Smith C. E., Malarkey K., Sturgill T. W. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 2893–2898 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sharma-Walia N., Krishnan H. H., Naranatt P. P., Zeng L., Smith M. S., Chandran B. (2005) J. Virol. 79, 10308–10329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pan H., Xie J., Ye F., Gao S. J. (2006) J. Virol. 80, 5371–5382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Xie J., Ajibade A. O., Ye F., Kuhne K., Gao S. J. (2008) Virology 371, 139–154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sadagopan S., Sharma-Walia N., Veettil M. V., Raghu H., Sivakumar R., Bottero V., Chandran B. (2007) J. Virol. 81, 3949–3968 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kuang E., Wu F., Zhu F. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 13958–13968 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Surh Y. J., Chun K. S., Cha H. H., Han S. S., Keum Y. S., Park K. K., Lee S. S. (2001) Mutat. Res. 480, 243–268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yin L., Laevsky G., Giardina C. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 44641–44646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.