Abstract

The related RING domain proteins MdmX and Mdm2 are best known for their role as negative regulators of the tumor suppressor p53. However, although Mdm2 functions as a ubiquitin ligase for p53, MdmX does not have appreciable ubiquitin ligase activity. In this study, we performed a mutational analysis of the RING domain of MdmX, and we identified two distinct regions that, when replaced by the respective regions of Mdm2, turn MdmX into an active ubiquitin ligase for p53. Mdm2 and MdmX form homodimers as well as heterodimers with each other. One of the regions identified localizes to the dimer interface indicating that subtle conformational changes in this region either affect dimer stability and/or the interaction with the ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme UbcH5b. The second region contains the cryptic nucleolar localization signal of Mdm2 but is also assumed to be involved in the interaction with UbcH5b. Here, we show that this region has a significant impact on the ability of respective MdmX mutants to functionally interact with UbcH5b in vitro supporting the notion that this region serves two distinct functional purposes, nucleolar localization and ubiquitin ligase activity. Finally, evidence is provided to suggest that the RING domain of Mdm2 not only binds to UbcH5b but also acts as an allosteric activator of UbcH5b.

Keywords: p53, Post-translational Modification, Ubiquitin-conjugating Enzyme (Ubc), Ubiquitin Ligase, Ubiquitination

Introduction

Genetic experiments in mice have shown that the related proteins Mdm2 and MdmX are critical regulators of the tumor suppressor protein p53. Knock-out of the mdm2 or the mdm4 gene (encoding MdmX) causes embryonic lethality, which is rescued by concomitant deletion of the p53 gene (1–4). Furthermore, analysis of tissue-specific Mdm2 and MdmX null mice indicates that the presence of MdmX is required to keep p53 in check in most but not all tissues, whereas Mdm2 appears to be essential in all tissues studied (5–11). Together with biochemical studies (12–14), these findings suggest that Mdm2 and MdmX act synergistically in p53 regulation but that Mdm2 also has MdmX-independent functions in p53 regulation and vice versa.

Mdm2 and MdmX share significant structural similarity, with the most conserved regions being the p53-binding domain within the N terminus of the respective protein, a central zinc- binding domain of unknown function, and a C-terminal RING domain (11, 15, 16). In many cases, RING or RING-like domains have been shown to represent interaction sites for ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes (E2), and thus, the presence of a RING domain is commonly assumed to be indicative for proteins with the function of an E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase (17–19). Indeed, Mdm2 has E3 ligase activity and in concert with members of the UbcH5 subfamily of E2s targets p53 for ubiquitination and degradation (20–24).

Unlike Mdm2, MdmX has no or only little E3 activity. It rather acts as a stimulator of the E3 activity of Mdm2 via heterocomplex formation, which is mediated by the respective RING domains of Mdm2 and MdmX (12, 13, 25, 26). Indeed, di- or multimeric forms of Mdm2 rather than Mdm2 monomers have E3 activity (14, 27). Furthermore, Mdm2-MdmX heteromers appear to be thermodynamically more stable than Mdm2 homomers providing a possible explanation for the observation that MdmX stimulates Mdm2 activity (25). In addition, Mdm2 but not MdmX contains amino acid sequence motifs for nuclear localization as well as nuclear export (11, 16, 24). Consequently, Mdm2 can shuttle between the nucleus and the cytosol, whereas the subcellular localization of MdmX depends on its interaction with Mdm2 or p53 (28, 29). Finally, there is evidence to indicate that Mdm2 controls the levels of MdmX and vice versa (13, 28, 30–32). In conclusion, the available data indicate that Mdm2 and MdmX cooperate to control the turnover rate of each other as well as that of p53.

Structural studies identified the amino acid residues of the RING domain of Mdm2 and MdmX that are involved in Mdm2 homodimer formation and Mdm2-MdmX heterodimer formation, respectively, and did not reveal any significant differences between the Mdm2 homodimer and the Mdm2-MdmX heterodimer (the structure of the RING domain of MdmX alone has not yet been reported) (27, 33). Furthermore, in silico comparisons with structures of RING domains of other E3s with their cognate E2 enzymes indicate that the amino acid residues of the Mdm2 RING domain that are presumably involved in E2 interaction are at least in part conserved in the MdmX RING domain (27, 33). Thus, to identify the regions within the RING domain of Mdm2 that render it an active E3 ligase for p53, we performed a mutational analysis of the RING domain of MdmX. The results obtained indicate that a region at the interface of the RING-RING dimer and a region overlapping with the cryptic nucleolar localization signal of Mdm2 (34, 35) are critical for E3 activity. In addition, the latter region affects the ability of the isolated RING domain of respective MdmX mutants to stimulate UbcH5b activity.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cell Lines and Plasmids

H1299 cells and mouse embryo fibroblasts derived from Mdm2/MdmX/p53 triple knock-out mice (kindly provided by J. C. Marine, Ghent, Belgium) were grown in DMEM supplemented with 10% (v/v) FBS.

Bacterial expression constructs for glutathione S-transferase (GST) fusion proteins of wild-type Mdm2 and MdmX were described previously (13, 14). Bacterial expression constructs for GST fusion proteins of various RING domain mutants of MdmX (see Fig. 1) and for UbcH5bI88A (36) were generated by PCR-based approaches (further details will be provided upon request). The expression constructs used in transient transfection experiments (Figs. 2–4) encoding wild-type p53 and His-tagged ubiquitin were described previously (13, 14). Expression constructs for p53Δ293–322 and for p531–43gal4 were generated by PCR-based approaches (further details will be provided upon request). For transient expression of Mdm2, MdmX, and the various MdmX mutants (Figs. 1 and 2), the respective cDNAs were extended at the 5′ end with a sequence encoding a FLAG tag and cloned into pcDNA4TO (Invitrogen).

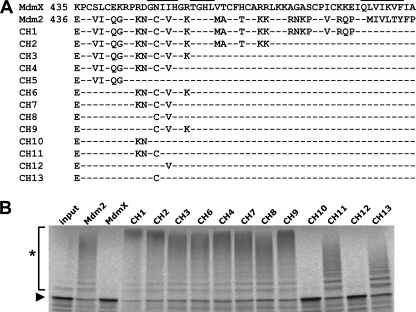

FIGURE 1.

In vitro ubiquitination of p53 by MdmX RING domain mutants. A, sequence alignment of the RING domains (C-terminal 56 amino acids) of human MdmX, human Mdm2, and the MdmX RING domain mutants generated. Residues previously shown to be involved in homodimer and heterodimer formation of the Mdm2 RING domain and the Mdm2-MdmX RING domains, respectively, are indicated by bars (27, 33). Note that due to the cloning strategy (i.e. introduction of an XhoI site), Lys-435 of MdmX was replaced in all mutants generated by Glu-436 of Mdm2. B, full-length versions of Mdm2, MdmX, and the various mutants (CH1–CH13) were bacterially expressed as GST fusion proteins. Similar amounts of the various fusion proteins (data not shown) were incubated with in vitro translated radiolabeled p53 under standard ubiquitination conditions for 2 h as indicated. The reaction products were analyzed by SDS-PAGE followed by fluorography. Running positions of the nonmodified form and of the ubiquitinated forms of p53 are indicated by an arrowhead and an asterisk, respectively. Note that the activity of Mdm2 and the various MdmX mutants varies slightly from protein preparation to preparation, but in general, CH11 and CH13 are less active than the other MdmX mutants. Furthermore, CH5 does not facilitate p53 ubiquitination (data not shown).

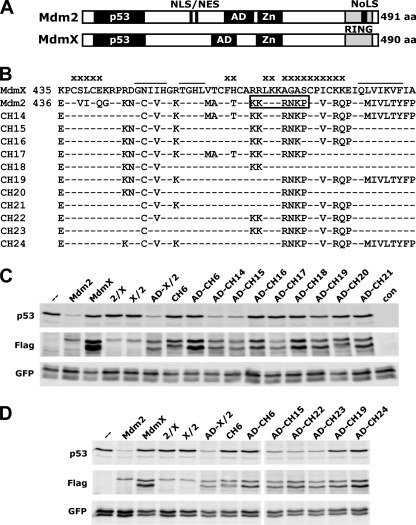

FIGURE 2.

Ability of RING domain mutants of MdmX to target p53 for degradation within cells. A, schematic structure of human Mdm2 and human MdmX. The positions of the p53 binding domain (residues 18–101 and 19–102, respectively), the acidic domain (AD; residues 237–288 and 215–255, respectively), the zinc finger (Zn; residues 289–331 and 290–332), and the RING domain (residues 436–482 and 435–481, respectively) are indicated. Residues 178–185 and 191–199 of Mdm2 include a nuclear localization signal (NLS) and a nuclear export signal (NES), respectively. Residues 466–474 represent the cryptic nucleolar localization signal (NoLS) of Mdm2 (11, 34, 35). aa, amino acids. B, sequence alignment of the RING domains (C-terminal 56 amino acids) of human MdmX, human Mdm2, and the MdmX RING domain mutants generated. Residues previously shown to be involved in homodimer and heterodimer formation of the Mdm2 RING domain and the Mdm2-MdmX RING domains, respectively, are indicated by bars (27, 33). Residues suggested to be involved in the interaction of Mdm2 with UbcH5b are indicated by “x,” and the cryptic nucleolar localization signal is boxed. C and D, H1299 cells were cotransfected with expression constructs for p53 and GFP (as control for transfection efficiency) in the absence (−) or presence of expression constructs for FLAG-tagged versions of Mdm2, MdmX, or the indicated MdmX mutants. Protein extracts were prepared 24 h after transfection, and levels of the various proteins were determined by Western blot analysis as indicated. 2/X indicates chimeric protein consisting of residues 1–436 of Mdm2 and 436–490 of MdmX; X/2 indicates chimeric protein consisting of residues 1–434 of MdmX and 436–491 of Mdm2; AD denotes that the central region of the respective MdmX mutants, which contains the acidic domain, was replaced by the respective region of Mdm2 (amino acids 202–302). Note that the results presented are representative for results obtained in at least three independent experiments. Furthermore, similar results were obtained with mouse embryo fibroblasts (MEFs) derived from mice null for Mdm2, MdmX, and p53 showing that the ability of MdmX mutants to target p53 for degradation does not require the presence of endogenous Mdm2 (supplemental Fig. 2). con, control.

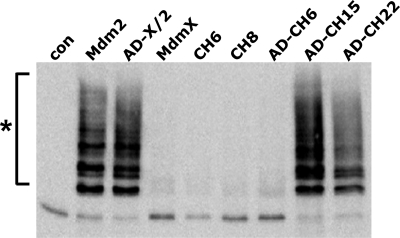

FIGURE 3.

Ability of RING domain mutants of MdmX to target p53 for ubiquitination within cells. H1299 cells were cotransfected with expression constructs for p53 and His-tagged ubiquitin in the absence (−) or presence of expression constructs for Mdm2, MdmX, or the indicated MdmX mutants as indicated. Protein extracts were prepared 24 h after transfection, and ubiquitinated proteins were isolated by Ni2+-affinity chromatography. Upon affinity purification, levels of ubiquitinated p53 were determined by Western blot analysis with the p53-specific antibody DO1. X/2 indicates chimeric protein consisting of residues 1–434 of MdmX and 436–491 of Mdm2; AD denotes that the central region of the respective MdmX mutants, which contains the acidic domain, was replaced by the respective region of Mdm2 (amino acids 202–302); * denotes ubiquitinated forms of p53; con indicates control.

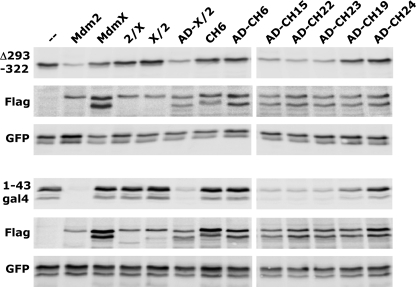

FIGURE 4.

Ability of RING domain mutants of MdmX to target p53Δ293–322 and 1–43gal4 for degradation within cells. H1299 cells were cotransfected with expression constructs for p53, p53Δ293–322, and 1–43gal4, respectively, and GFP in the absence (−) or presence of expression constructs for FLAG-tagged Mdm2, MdmX, or the indicated MdmX mutants. Protein extracts were prepared 24 h after transfection, and levels of the various proteins were determined by Western blot analysis as indicated. p53Δ293–322 represents a p53 mutant with an internal deletion of residues 293–322 that contain the major nuclear localization signal of p53 (i.e. in contrast to p53, this protein resides mainly in the cytoplasm). 1–43gal4 represents a fusion protein consisting of the N-terminal 43 amino acids of p53 (which contain the main binding site for Mdm2 and MdmX, respectively) fused to the Gal4 DNA-binding domain. A similar construct was originally used to show that binding of Mdm2 targets p53 for proteasome-mediated degradation (38). 2/X indicates chimeric protein consisting of residues 1–436 of Mdm2 and 436–490 of MdmX; X/2 indicates chimeric protein consisting of residues 1–434 of MdmX and 436–491 of Mdm2; AD denotes that the central region of the respective MdmX mutants, which contains the acidic domain, was replaced by the respective region of Mdm2 (amino acids 202–302).

Transfection and Antibodies

For transient expression, cells were transfected with the respective constructs in the presence of a reporter construct encoding the green fluorescent protein (GFP) by lipofection (Lipofectamine 2000; Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Protein extracts were prepared 24 h after transfection (14), and relative transfection efficiency was determined by monitoring GFP levels by Western blot analysis. Levels of p53 or ubiquitinated p53, FLAG-tagged Mdm2, MdmX, and MdmX mutants were determined by Western blot analysis. The antibodies used for detection were the mouse monoclonal M2 (Sigma) for FLAG-tagged proteins, the mouse monoclonal DO1 (Calbiochem) for p53, the mouse monoclonal ab1218 (Abcam) for GFP, and the mouse monoclonal P4G7 (Abcam) for ubiquitin.

Ubiquitination and Degradation Assays

For in vitro ubiquitination experiments, wild-type Mdm2, MdmX, and the various MdmX mutants were expressed as GST fusion proteins in Escherichia coli DH5α (13, 14). The ubiquitin-activating enzyme E1 was expressed in the baculovirus system, and UbcH5b and its mutant 5bI88A were expressed in E. coli BL21 by using the pET expression system as described previously (13, 14). For in vitro ubiquitination of p53, 1 μl of rabbit reticulocyte lysate-translated 35S-labeled p53 was incubated with 50 ng of E1, 50 ng of UbcH5b, and 20 μg of ubiquitin (Sigma) in the absence or in the presence of bacterially expressed Mdm2, MdmX, or the respective mutant proteins (200 ng) in 40-μl volumes. In addition, reactions contained 25 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 50 mm NaCl, 1 mm DTT, 2 mm ATP, and 4 mm MgCl2 (13, 14). After incubation at 30 °C for 2 h, total reaction mixtures were electrophoresed in 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gels and 35S-labeled p53 detected by fluorography. Results shown are representative of at least three different experiments with three different preparations of each protein.

For in vitro UbcH5b-mediated ubiquitin chain formation and ubiquitination of Mmd2/MdmX (“auto-ubiquitination”), respectively, reaction conditions were as described above for p53 ubiquitination, unless otherwise indicated. Reaction mixtures were electrophoresed in 17.5% SDS-polyacrylamide gels, and proteins were detected by staining with Coomassie Blue or by Western blot analysis using an anti-ubiquitin antibody as indicated.

For ubiquitination of p53 within cells, one 6-cm plate of H1299 cells was transfected with expression constructs encoding p53 (200 ng), His-tagged ubiquitin (1 μg), Mdm2, MdmX, or the respective MdmX mutants (1 μg). 24 h after transfection, 30% of the cells were lysed under nondenaturing conditions as described previously (14) to determine expression levels of Mdm2, the various forms of MdmX, and GFP. The remaining cells were lysed under denaturing conditions, and ubiquitinated proteins were purified as described previously (14).

To monitor degradation of ectopically expressed p53 within cells, one 6-cm plate of H1299 cells or one 10-cm plate of mouse embryo fibroblasts was transfected with expression constructs encoding p53 (50 ng), Mdm2, MdmX, or the respective MdmX mutants (200 ng). Protein extracts were prepared 24 h after transfection as described previously (13, 14), and p53 levels were determined by Western blot analysis.

RESULTS

A Single Amino Acid Exchange (N448C) Results in an MdmX Mutant Competent for p53 Ubiquitination in Vitro

An obvious explanation for the observation that MdmX is not active or is only weakly active as an E3 ligase is the notion that MdmX does not interact or only poorly interacts with UbcH5b. As we previously reported that Mdm2 detectably interacts with UbcH5b in the yeast two-hybrid system but not under the conditions of an in vitro coprecipitation experiment (14), the ability of the RING domain of MdmX to interact with UbcH5b was tested in yeast. This showed that the RING domain of MdmX interacted with UbcH5b, although slightly less efficiently than the RING domain of Mdm2 (data not shown). To corroborate this finding, the ability of the RING domain of Mdm2 and MdmX to bind to UbcH5b was additionally studied by size exclusion chromatography. Under the conditions used, UbcH5b co-migrated with both Mdm2 and MdmX (supplemental Fig. 1). These results indicate that there is no large difference between the RING domain of Mdm2 and MdmX in their ability to bind to UbcH5b in vitro. Thus, the inability of MdmX to act as an E3 ligase for p53 does not appear to be due to the notion that MdmX cannot interact with UbcH5b.

To obtain information about the regions of the MdmX RING domain that prevent it from acting as an E3 ligase for p53, cDNAs encoding MdmX variants with chimeric RING domains consisting of distinct parts of the RING domain of MdmX and Mdm2 were generated by PCR-based mutagenesis (Fig. 1A). The respective proteins were expressed as GST fusion proteins in E. coli. Upon purification, the MdmX mutants were tested for their ability to ubiquitinate in vitro translated 35S-labeled p53 (Fig. 1B). The results obtained show that replacement of the asparagine residue at position 448 of MdmX (numbering according to human MdmX) by cysteine, the respective residue of Mdm2, results in an MdmX mutant that can efficiently ubiquitinate p53 in vitro. Furthermore, substitution of residues surrounding Asn-448 by the respective Mdm2 residues, most importantly residues 450 and 453, result in MdmX mutants that ubiquitinate p53 in vitro with an efficiency similar to wild-type Mdm2 (as determined in titration experiments; data not shown).

Region Encompassing the Nucleolar Localization Signal of Mdm2 Is Required for p53 Ubiquitination and Degradation within Cells

It was previously reported that in addition to an intact RING domain, the central region of Mdm2 (amino acids 202–302) containing the so-called acidic domain (Fig. 2A) is required for p53 ubiquitylation and degradation within cells (37). Indeed, a chimeric protein consisting of the RING domain of Mdm2 fused to amino acid residues 1–434 of MdmX was not able to target p53 for degradation in coexpression experiments (Fig. 2C, X/2), whereas the respective chimera containing the central region of Mdm2 (Fig. 2C, AD-X/2) was active (note that in the in vitro system, the central region of Mdm2 is not required for p53 ubiquitination; see under “Discussion”). Thus, to determine whether substitution of amino acids 445–453 of MdmX by the respective amino acids of Mdm2 results in an MdmX mutant that can target p53 for ubiquitination and degradation within cells, the central region of the MdmX mutant CH6 (Fig. 1A) was replaced by the central region of Mdm2 (Fig. 2, AD-CH6). However, neither CH6 nor AD-CH6 was able to target p53 for degradation (Fig. 2C) or for ubiquitination (Fig. 3). This indicates that the requirements for p53 ubiquitination in vitro are different from those for p53 ubiquitination and degradation within cells.

To determine the regions of the Mdm2 RING domain that are required for p53 ubiquitination/degradation within cells, cDNAs encoding additional chimeric proteins were generated (Fig. 2B). Coexpression of the respective proteins with p53 revealed that besides N448C, a region spanning amino acids 465–480 (numbering according to human MdmX) is required for both p53 degradation (Fig. 2C) and p53 ubiquitination (Fig. 3) within cells.

Amino acids 465–480 contain the cryptic nucleolar localization signal (465–473) of Mdm2 (Fig. 2) (34, 35), and thus, it is conceivable that for p53 ubiquitination and degradation, p53 and Mdm2 have to pass through the nucleolus. To address this possibility, a p53 deletion mutant (Δ293–322) devoid of the main nuclear localization signal of p53 (24) and a chimeric protein consisting of the N-terminal 43 amino acids of p53 fused to the DNA-binding domain of the yeast transcription factor Gal4 (1–43gal4) (38) were tested for their ability to be degraded by Mdm2, MdmX, and various MdmX mutants. This showed (Fig. 4) that those MdmX mutants that were able to degrade wild-type p53 were also able to degrade Δ293–322 and 1–43gal, whereas those that were inactive for p53 degradation also did not facilitate degradation of Δ293–322 and 1–43gal. Furthermore, subcellular localization of Mdm2, MdmX, and selected MdmX mutants was determined by immunofluorescence microscopy (supplemental Fig. 3). As expected (11, 16, 24, 28, 29), Mdm2 localized mainly to the nucleus, although MdmX and the MdmX mutants studied were mainly or even exclusively found in the cytoplasm under the conditions used. Most importantly, there was no obvious difference in the localization of MdmX mutants that can target p53 for degradation and MdmX mutants that are inactive in this respect. This indicates that the inability of the MdmX mutants studied to target p53 for degradation is not due to inappropriate cellular localization. Taken together, the evidence obtained indicates that neither p53 nor Mdm2 nor the active MdmX mutants need to localize to the nucleolus or nucleus for p53 degradation.

RING Domain of Mdm2 Stimulates UbcH5b-mediated Ubiquitin Chain Formation

The data presented above are consistent with the possibility that in addition to representing a nucleolar localization signal, the respective region affects another property of the Mdm2 RING domain. Structural data indicate that the nucleolar localization signal overlaps with amino acid residues of the RING domain that are involved in mediating the interaction with UbcH5b (Fig. 2 and also see Fig. 7) (27, 33). Thus, the isolated RING domains of Mdm2, MdmX, CH8 (MdmX RING domain with N448C and I450V; Fig. 1A), and CH22 (as CH8, but additional substitution of amino acids 465–480 by the respective Mdm2 residues; Fig. 2, A and B) were expressed as GST fusion proteins in bacteria and tested for their ability to stimulate UbcH5b activity.

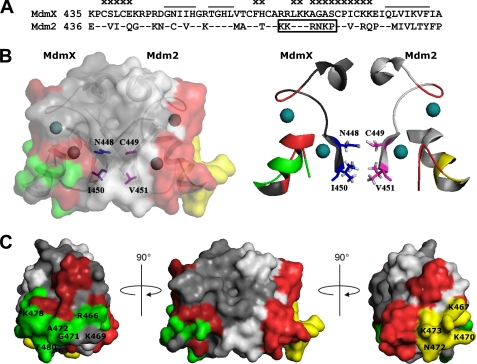

FIGURE 7.

Structure of the Mdm2-MdmX RING domain heterodimer. A, sequence alignment of the RING domains (C-terminal 56 amino acids) of human MdmX and human Mdm2. Residues previously shown to be involved in homodimer and heterodimer formation of the Mdm2 RING domain and the Mdm2-MdmX RING domains, respectively, are indicated by bars (27, 33). Residues suggested to be involved in interaction of Mdm2 with UbcH5b are indicated by x, and the cryptic nucleolar localization signal is boxed. B, schematic diagrams of the heterodimer indicating that Asn-448 and Ile-450 of MdmX (indicated in blue) are localized at the dimer interface opposing Cys-449 and Val-451, respectively, of Mdm2 (indicated in red). The side chains of the respective residues are shown as sticks; zinc ions are shown as spheres. C, surface models of the heterodimer. The RING domains of MdmX and Mdm2 are shown in dark gray and light gray, respectively. The surface area of Mdm2 suggested to be involved in the interaction with UbcH5b is shown in red and yellow, with yellow also representing the cryptic nucleolar localization signal (34, 35). The surface of MdmX corresponding to the suggested E2 interaction site of Mdm2 is shown in red and green, with green representing those residues of MdmX that need to be substituted by the respective residues of Mdm2 for p53 ubiquitination and degradation in cells.

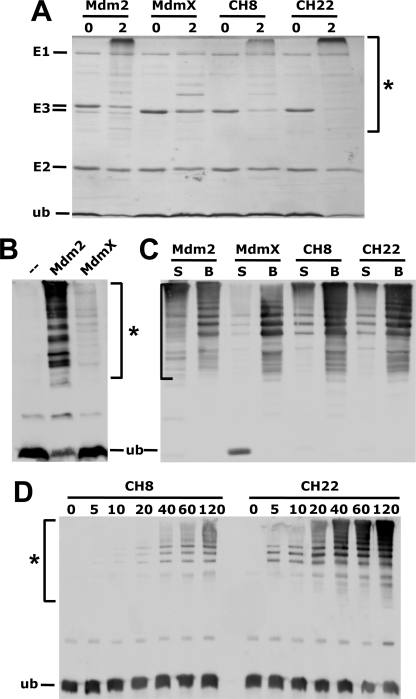

The different RING domains were incubated with E1, UbcH5b, and ubiquitin under standard ubiquitination conditions (see under “Experimental Procedures”), and proteins were visualized either by Coomassie Blue staining (Fig. 5A) or by Western blot analysis using an anti-ubiquitin antibody (Fig. 5, B–D). As expected, a significant amount of high molecular mass bands representing ubiquitinated GST-RING domains and/or free ubiquitin chains were observed with Mdm2, CH8, and CH22, although the RING domain of MdmX was significantly less active in this assay (Fig. 5, A and B). To distinguish between ubiquitinated GST-RING domains and free ubiquitin chains, a similar assay was performed with the different GST-RING domains bound to glutathione beads. After the reaction, GST-RING domains were spun down by centrifugation, and the amount of ubiquitin present in the supernatant (S, Fig. 5C) and in the beads fraction (B, Fig. 5C) was determined by Western blot analysis. This revealed that in the presence of the Mdm2 RING domain and to a lesser extent in the presence of CH8 and CH22, high molecular mass forms of ubiquitin were observed in the supernatant fraction. In contrast, in the case of MdmX, high molecular mass forms of ubiquitin were almost exclusively observed in the bound fraction (i.e. representing ubiquitinated GST-MdmX). These data suggest that Mdm2 and the active chimeric RING domains have the ability to stimulate UbcH5b-mediated formation of free ubiquitin chains. Furthermore, time course experiments with similar amounts of CH8 and CH22 indicate that CH22 is significantly more active in this type of assay than CH8 (Fig. 5D).

FIGURE 5.

Mdm2 RING domain facilitates UbcH5b-mediated ubiquitin chain formation. A, RING domain of Mdm2, MdmX, and the MdmX mutants CH8 and CH22 were bacterially expressed as GST fusion proteins. Similar amounts of the various fusion proteins were incubated with purified ubiquitin-activating enzyme, UbcH5b, and ubiquitin for 0 or 2 h as indicated. The reaction products were analyzed by SDS-PAGE followed by staining with Coomassie Blue. Running positions of ubiquitin (ub), UbcH5b (E2), ubiquitin-activating enzyme (E1), and the various RING domains (E3) are indicated. * denotes high molecular mass forms of ubiquitin representing ubiquitinated forms of the various RING domains and free ubiquitin chains, respectively. B, ubiquitin, ubiquitin-activating enzyme, and UbcH5b were incubated in the absence (−) or presence of the RING domain of Mdm2 or MdmX for 2 h. The reaction products were analyzed by SDS-PAGE followed by Western blot analysis using a ubiquitin-specific antibody. C, reactions were performed as described in A and B, with the difference that the various RING domains were bound to glutathione beads during the reaction. After reaction, glutathione beads were centrifuged; the supernatant was removed, and the beads were washed. Proteins present in the supernatant fraction (S) or bound to glutathione beads (B) were analyzed by SDS-PAGE followed by Western blot analysis using a ubiquitin-specific antibody. D, similar amounts of the RING domains CH8 and CH22 were incubated with ubiquitin, ubiquitin-activating enzyme, and UbcH5b for the times indicated (in min). Analysis of the reaction products was as in B. ub indicates running position of ubiquitin; * indicates running position of ubiquitinated forms of the respective RING domains and free ubiquitin chains, respectively.

Ile-88 of UbcH5b Is Critically Involved in Mdm2-stimulated Ubiquitin Chain Formation

The results presented in Fig. 5 indicate that the RING domain of Mdm2 not only provides a platform for interaction with UbcH5b but, in addition, stimulates UbcH5b activity (note that in the absence of Mdm2, higher molecular mass forms of ubiquitin are not observed in the presence of UbcH5b and E1 under the conditions used; Fig. 5B). This is consistent with a previous report indicating that at least certain RING domains can act as allosteric activators of their cognate E2s (36). Furthermore, it was reported that RING-induced activation requires the presence of an isoleucine residue at position 88 of UbcH5b. Thus, to obtain initial evidence that the Mdm2 RING domain may activate UbcH5b via a similar mechanism, Mdm2-facilitated ubiquitin chain formation was studied in the presence of wild-type UbcH5b and a UbcH5b mutant with substitution of isoleucine 88 by alanine (5bI88A). As shown in Fig. 6, 5bI88A was significantly less active in this type of assay (by an order of at least 1–2 magnitudes) than wild-type UbcH5b.

FIGURE 6.

Mdm2-mediated ubiquitination is inefficiently supported by an allosteric mutant of UbcH5b. The RING domain of Mdm2 was incubated with purified ubiquitin-activating enzyme and ubiquitin in the absence (−) or presence of increasing amounts (25, 50, 100, and 200 ng) of UbcH5b or a UbcH5b mutant, in which isoleucine 88 was replaced by alanine (5bI88A). After 2 h, reaction products were analyzed by SDS-PAGE followed by staining with Coomassie Blue. Note that Ile-88 does not appear to be directly involved in the interaction of UbcH5b with RING domains and that 5bI88A forms thioester complexes with ubiquitin with an efficiency similar to wild-type UbcH5b (36). Running positions of ubiquitin (ub), UbcH5b (E2), ubiquitin-activating enzyme (E1), and the various RING domains (E3) are indicated. High molecular mass forms of ubiquitin are indicated by an asterisk.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we show that substitution of two regions within the MdmX RING domain by the respective regions of Mdm2 turn MdmX into an active E3 ligase for p53. The first region encompasses amino acids 448–453, and a single amino acid substitution in this region (N448C; Figs. 1B and 7) results in an MdmX mutant with a significantly increased ability to ubiquitinate p53 in vitro. For ubiquitination and degradation of p53 within cells, however, concomitant substitution of the region encompassing amino acid residues 465–480 is required (Figs. 2C and 7). In view of the finding that the RING domain of MdmX can interact with UbcH5b (supplemental Fig. 1), these data suggest that a physical contact between a RING domain and its cognate E2 does not suffice to facilitate E2-mediated ubiquitination of substrate proteins and that for functional interaction additional constraints must be met.

Structural analyses of the Mdm2 RING domain homodimer and the Mdm2-MdmX RING domain heterodimer have shown that residues 448–453 are part of a β-strand (β1) involved in mediating RING-RING dimer formation (Fig. 7) (27, 33). Although Ile-450 (MdmX) and Val-451 (Mdm2) are primarily involved in the formation of the dimer interface, Asn-448 (MdmX) and Cys-449 (Mdm2) do not appear to directly contribute to dimer formation but are buried at the interface facing each other. Thus, although the structure of MdmX RING domain homodimers has not yet been reported, it seems conceivable that the presence of two asparagines at this position of the interface affects the overall conformation of the MdmX RING domain homodimer and/or its thermodynamic stability (note that dimerization of Mdm2 is required for E3 ligase activity (14, 27)). We attempted to test the latter possibility by studying the stability of the various RING domain dimers by surface plasmon resonance but were not successful (mainly because bacterially expressed RING domain of Mdm2 tends to aggregate). It should be noted that substitution of Cys-449 of Mdm2 by serine was previously reported to result in an Mdm2 mutant that retains some E3 activity in vitro but is incapable of acting as an E3 ligase within cells (37). Thus, even a slight deviation (i.e. exchange of a thiol group by a hydroxyl group) at the respective position significantly affects E3 ligase activity. Nonetheless, to understand the mechanism by which the residue at position 448 (of MdmX) affects the E3 ligase activity of Mdm2 and MdmX, respectively, the structure of MdmX RING domain homodimers and, maybe more importantly, structures of the various RING domain dimers (Mdm2, Mdm2-MdmX, and MdmX) in complex with UbcH5b will have to be solved.

Amino acid residues 466–481 of Mdm2 but not the respective region of MdmX (residues 465–480) contain a nucleolar localization signal (residues 466–474) that was previously shown to be functional when p14ARF is bound to the central region of Mdm2 or when an extended central region of Mdm2 (residues 222–437) is deleted (34, 35). Based on the data obtained with p53 mutants (Fig. 4) and by immunofluorescence analysis (supplemental Fig. 3), it seems likely that nucleolar localization of neither p53 nor Mdm2 is essential for p53 degradation. Moreover, the results obtained with the MdmX RING domain mutants CH8 and CH22 (Fig. 5) indicate that residues 466–481 of Mdm2 serve an additional function. Structural comparison of the MDM2 RING domain with other RING domains in complex with their cognate E2s (27, 33) implicated residues 468, 469, and 472–480 of Mdm2 to be important for UbcH5b binding (Fig. 7). This assumption (amino acids 466–481 are part of the interaction surface of the RING domain of Mdm2 for UbcH5b) provides a reasonable explanation for the observation that in vitro CH22 has a more significant effect on UbcH5b activity than CH8 (Fig. 5D). Thus, a tempting but purely speculative model is that Mdm2 nucleolar localization (which is likely mediated by interaction of the nucleolar localization signal with a yet unknown protein (34, 35, 39)) and functional interaction of Mdm2 with UbcH5b are mutually exclusive events. In this model, binding of p14ARF to the central region of Mdm2 would disfavor the interaction of Mdm2 with UbcH5b and induce localization of Mdm2 to nucleoli and, as previously shown, p53 stabilization (23). On the other hand, interaction of the central region of Mdm2 with p53 (40) or with factors that stimulate Mdm2-mediated ubiquitination of p53, including CBP/p300 (41, 42), may positively affect Mdm2-UbcH5b interaction.

The above scenario (interaction of the RING domain with UbcH5b is modulated by cellular factors) may also provide an explanation for the observation that the central region of Mdm2, which contains the acidic domain (Fig. 2A), is required for p53 ubiquitination and degradation in cells but not in vitro. For example, it is conceivable that the respective region of MdmX interacts with negative regulatory factors but not with positive ones, and these potential inhibitory factors are not present in the in vitro system. Another possibility is provided by the finding that the central region of Mdm2 interacts with the Mdm2 RING domain (43). Thus, rather than interacting with additional proteins, interaction of the RING domain with the central region may positively affect Mdm2-UbcH5b interaction. In analogy to the results obtained for the region spanning amino acids 466–481 of Mmd2, this stimulatory effect may be required for efficient p53 degradation within cells but not for in vitro ubiquitination. To prove this possibility, experiments in defined in vitro systems will have to be performed.

Recent data indicate that RING domain E3 ligases do not only function as adaptor proteins between substrate proteins and E2s but in addition can act as allosteric activators of E2s (36, 44). Most significantly with respect to this study, detailed analysis of the interaction of UbcH5b with APC2/APC11 and the isolated RING domain of CNOT4 revealed that binding of an isolated RING domain induces slight but significant conformational changes in the cognate E2 (36) with isoleucine at position 88 as one of the residues affected. Importantly, substitution of Ile-88 by alanine resulted in a UbcH5b mutant that can still bind to RING domains and form thioester complexes with ubiquitin with an efficiency similar to UbcH5b but can no longer be allosterically activated (36). In agreement with the notion that the Mdm2 RING domain also acts as an allosteric activator of UbcH5b, UbcH5bI88A was only poorly activated by Mdm2 (Fig. 6) and only inefficiently supports Mdm2-facilitated ubiquitination of p53 in vitro (data not shown). However, the RING domain of Mdm2 has been reported to form dimeric and higher order multimeric structures (25, 27, 33, 45). An alternative but not mutually exclusive possibility therefore is that by forming multimeric structures, the RING domain of Mdm2 brings two or more UbcH5b molecules into close proximity thereby facilitating UbcH5b-mediated formation of (free) ubiquitin chains and ubiquitination of Mdm2 or Mdm2-associated proteins (e.g. p53).

Studies with transgenic mice indicate that Mdm2 and MdmX act synergistically but also have independent nonredundant functions in the control of p53 (5–10). In a simplified view, Mdm2 may counteract p53 activity mainly by targeting p53 for degradation, whereas MdmX may form tighter complexes with p53 than Mdm2 thereby interfering with p53 activity in a stoichiometric manner (16, 25). In combination with the notion that Mdm2-MdmX heteromeric complexes may possess both properties, this may allow a cell to finely tune Mdm2/MdmX-mediated regulation of p53. In this context, it will be interesting to determine/characterize the phenotype of transgenic mice that, instead of Mdm2 and MdmX, express an Mdm2-MdmX chimeric protein such as AD-CH22 that potentially possesses the properties of both Mdm2 and MdmX.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft and by the European Union Network of Excellence RUBICON.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. 1–3.

REFERENCES

- 1.Jones S. N., Roe A. E., Donehower L. A., Bradley A. (1995) Nature 378, 206–208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Montes de Oca Luna R., Wagner D. S., Lozano G. (1995) Nature 378, 203–206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Parant J., Chavez-Reyes A., Little N. A., Yan W., Reinke V., Jochemsen A. G., Lozano G. (2001) Nat. Genet. 29, 92–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Finch R. A., Donoviel D. B., Potter D., Shi M., Fan A., Freed D. D., Wang C. Y., Zambrowicz B. P., Ramirez-Solis R., Sands A. T., Zhang N. (2002) Cancer Res. 62, 3221–3225 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Migliorini D., Lazzerini Denchi E., Danovi D., Jochemsen A., Capillo M., Gobbi A., Helin K., Pelicci P. G., Marine J. C. (2002) Mol. Cell. Biol. 22, 5527–5538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Francoz S., Froment P., Bogaerts S., De Clercq S., Maetens M., Doumont G., Bellefroid E., Marine J. C. (2006) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 3232–3237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grier J. D., Xiong S., Elizondo-Fraire A. C., Parant J. M., Lozano G. (2006) Mol. Cell. Biol. 26, 192–198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marine J. C., Francoz S., Maetens M., Wahl G., Toledo F., Lozano G. (2006) Cell Death Differ. 13, 927–934 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xiong S., Van Pelt C. S., Elizondo-Fraire A. C., Liu G., Lozano G. (2006) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 3226–3231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wade M., Wahl G. M. (2009) Mol. Cancer Res. 7, 1–11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wade M., Wang Y. V., Wahl G. M. (2010) Trends Cell Biol. 20, 299–309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Badciong J. C., Haas A. L. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 49668–49675 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Linares L. K., Hengstermann A., Ciechanover A., Müller S., Scheffner M. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 12009–12014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Singh R. K., Iyappan S., Scheffner M. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 10901–10907 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shvarts A., Steegenga W. T., Riteco N., van Laar T., Dekker P., Bazuine M., van Ham R. C., van der Houven van Oordt W., Hateboer G., van der Eb A. J., Jochemsen A. G. (1996) EMBO J. 15, 5349–5357 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marine J. C., Jochemsen A. G. (2004) Cell Cycle 3, 900–904 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weissman A. M. (2001) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2, 169–178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kerscher O., Felberbaum R., Hochstrasser M. (2006) Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 22, 159–180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Deshaies R. J., Joazeiro C. A. (2009) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 78, 399–434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Honda R., Tanaka H., Yasuda H. (1997) FEBS Lett. 420, 25–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fang S., Jensen J. P., Ludwig R. L., Vousden K. H., Weissman A. M. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 8945–8951 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Honda R., Yasuda H. (2000) Oncogene. 19, 1473–1476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saville M. K., Sparks A., Xirodimas D. P., Wardrop J., Stevenson L. F., Bourdon J. C., Woods Y. L., Lane D. P. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 42169–42181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kruse J. P., Gu W. (2009) Cell 137, 609–622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tanimura S., Ohtsuka S., Mitsui K., Shirouzu K., Yoshimura A., Ohtsubo M. (1999) FEBS Lett. 447, 5–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Uldrijan S., Pannekoek W. J., Vousden K. H. (2007) EMBO J. 26, 102–112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Linke K., Mace P. D., Smith C. A., Vaux D. L., Silke J., Day C. L. (2008) Cell Death Differ. 15, 841–848 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Migliorini D., Danovi D., Colombo E., Carbone R., Pelicci P. G., Marine J. C. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 7318–7323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li C., Chen L., Chen J. (2002) Mol. Cell. Biol. 22, 7562–7571 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stad R., Little N. A., Xirodimas D. P., Frenk R., van der Eb A. J., Lane D. P., Saville M. K., Jochemsen A. G. (2001) EMBO Rep. 2, 1029–1034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.de Graaf P., Little N. A., Ramos Y. F., Meulmeester E., Letteboer S. J., Jochemsen A. G. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 38315–38324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pan Y., Chen J. (2003) Mol. Cell. Biol. 23, 5113–5121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kostic M., Matt T., Martinez-Yamout M. A., Dyson H. J., Wright P. E. (2006) J. Mol. Biol. 363, 433–450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lohrum M. A., Ashcroft M., Kubbutat M. H., Vousden K. H. (2000) Nat. Cell Biol. 2, 179–181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weber J. D., Kuo M. L., Bothner B., DiGiammarino E. L., Kriwacki R. W., Roussel M. F., Sherr C. J. (2000) Mol. Cell. Biol. 20, 2517–2528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ozkan E., Yu H., Deisenhofer J. (2005) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 18890–18895 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Meulmeester E., Frenk R., Stad R., de Graaf P., Marine J. C., Vousden K. H., Jochemsen A. G. (2003) Mol. Cell. Biol. 23, 4929–4938 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Haupt Y., Maya R., Kazaz A., Oren M. (1997) Nature 387, 296–299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Emmott E., Hiscox J. A. (2009) EMBO Rep. 10, 231–238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yu G. W., Rudiger S., Veprintsev D., Freund S., Fernandez-Fernandez M. R., Fersht A. R. (2006) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 1227–1232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Grossman S. R., Deato M. E., Brignone C., Chan H. M., Kung A. L., Tagami H., Nakatani Y., Livingston D. M. (2003) Science 300, 342–344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shi D., Pop M. S., Kulikov R., Love I. M., Kung A. L., Kung A., Grossman S. R. (2009) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 16275–16280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dang J., Kuo M. L., Eischen C. M., Stepanova L., Sherr C. J., Roussel M. F. (2002) Cancer Res. 62, 1222–1230 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Das R., Mariano J., Tsai Y. C., Kalathur R. C., Kostova Z., Li J., Tarasov S. G., McFeeters R. L., Altieri A. S., Ji X., Byrd R. A., Weissman A. M. (2009) Mol. Cell 34, 674–685 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Poyurovsky M. V., Priest C., Kentsis A., Borden K. L., Pan Z. Q., Pavletich N., Prives C. (2007) EMBO J. 26, 90–101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.