Abstract

The intracellular fatty acid-binding proteins (FABPs) are abundantly expressed in almost all tissues. They exhibit high affinity binding of a single long-chain fatty acid, with the exception of liver FABP, which binds two fatty acids or other hydrophobic molecules. FABPs have highly similar tertiary structures consisting of a 10-stranded antiparallel β-barrel and an N-terminal helix-turn-helix motif. Research emerging in the last decade has suggested that FABPs have tissue-specific functions that reflect tissue-specific aspects of lipid and fatty acid metabolism. Proposed roles for FABPs include assimilation of dietary lipids in the intestine, targeting of liver lipids to catabolic and anabolic pathways, regulation of lipid storage and lipid-mediated gene expression in adipose tissue and macrophages, fatty acid targeting to β-oxidation pathways in muscle, and maintenance of phospholipid membranes in neural tissues. The regulation of these diverse processes is accompanied by the expression of different and sometimes multiple FABPs in these tissues and may be driven by protein-protein and protein-membrane interactions.

Keywords: Fatty Acid, Fatty Acid-binding Protein, Fatty Acid Transport, Lipid-binding Protein, Lipid Transport

Introduction

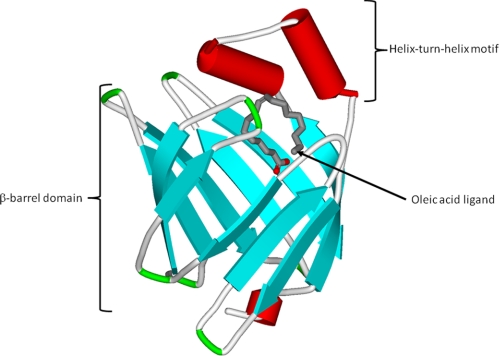

The fatty acid-binding proteins (FABPs)3 are abundant intracellular proteins expressed in almost all tissues; nine separate genes have been identified in mammals. FABPs were named after the tissue in which they were discovered or are prominently expressed. This nomenclature can be misleading because several FABPs are expressed in more than one tissue, and a numerical nomenclature for the various FABPs has been introduced (1–3). All FABPs exhibit high affinity binding of a single saturated or unsaturated long-chain fatty acid (LCFA; ≥14 carbons), with the exception of liver FABP (LFABP; FABP1), which binds two fatty acids or other hydrophobic molecules. Binding affinities correlate directly with fatty acid hydrophobicity (1–4). These small proteins (∼15 kDa) show only moderate amino acid sequence homology, ranging from 20 to 70%, yet they have highly similar tertiary structures. All have in common a 10-stranded antiparallel β-barrel structure. The ligand-binding pocket is located inside the β-barrel and is framed on one side by an N-terminal helix-turn-helix motif that is thought to act as the major portal for LCFA entry and exit (Fig. 1) (1–3).

FIGURE 1.

Crystal structure of human HFABP containing an oleic acid ligand (Protein Data Bank code 1HMS). The protein structure is similar for all the FABPs and shows the β-barrel domain and the N-terminal helix-turn-helix motif (56).

Why are there multiple FABPs, then, when all have a similar fold and all bind LCFA? Other classes of lipid-binding proteins are typically ubiquitously expressed from a single gene. As will be discussed below, recent research has suggested that the FABPs have individual functions in their specific tissues. Although all FABPs are involved in fatty acid disposition, it is likely that the diverse nature of fatty acid function is reflected in the diversity of FABP expression in different tissues. These divergent functions may be driven, in part, by protein-protein and protein-membrane interactions that are tissue specific. This minireview will present hypotheses regarding the functions of FABPs in different tissues, evaluating the evidence obtained from cultured cells, structure-function analyses, and gene knock-out mice.

Tissue-specific FABP Functions

Adipose Tissue

Adipose tissue is the major reservoir of stored calories in the form of triacylglycerol (TG). It has become increasingly apparent that adipose tissue is also an important endocrine organ, releasing many bioactive molecules, including cytokines involved in inflammation. Therefore, adipose tissue metabolism has important effects on systemic energy metabolism and inflammatory processes. Adipocytes express very high levels of the adipocyte FABP (AFABP; FABP4) and very low levels of the skin-type FABP (KFABP; FABP5).

Studies of AFABP support a role in both the TG storage and inflammatory functions of the adipose tissue. Ablation of AFABP expression results in marked up-regulation of KFABP expression (5–7) and is accompanied by relatively minor metabolic alterations in the adipose tissue, likely due to the similar ligand binding and in vitro transport properties of the two FABPs (6, 8). However, simultaneous deletion of both AFABP and KFABP reveals their importance in systemic energy balance, with double-null animals displaying a marked protection against the development of insulin resistance and the metabolic syndrome and against a variety of inflammatory diseases (9).

Emerging research points to several mechanisms of action of the adipose FABPs. AFABP has been shown to interact with the hormone-sensitive lipase (HSL), with charged residues in the helix-turn-helix domain of AFABP interacting with oppositely charged residues on HSL (10). Although a role in stimulating lipolysis by relieving lipase end product inhibition was initially proposed, only the holo-AFABP was found to interact with HSL. Moreover, the AFABP·HSL complex is present both in the cytosol, where HSL is inactive, and on the surface of lipid droplets, where the lipase is active (10).

AFABP may also function by regulating the fatty acid species profile in plasma. Higher levels of the low abundance palmitoleate (C16:1ω9) were reported in the adipose tissue and plasma of AFABP/KFABP double-null mice, and incubation of cultured liver and muscle cells with palmitoleate, in comparison with the saturated palmitate (PA; C16:0), led to changes consistent with protection against insulin resistance (11). The mechanism of palmitoleate action and a direct comparison of palmitoleate with oleate (OA; C18:1ω9) remain to be investigated (1).

AFABP may also function in adipose tissue at the level of gene transcription. AFABP binding of specific ligands leads to subtle conformational changes in the helical domain that promote nuclear localization and subsequent binding to the nuclear transcription factor PPARγ (12). Nuclear localization and PPARγ interaction occur only for those ligands that activate PPARγ target gene transcription (12, 13).

Macrophages

Unlike adipose tissue, differentiated macrophages express high levels of both AFABP and KFABP, and macrophage KFABP levels remain unchanged following AFABP ablation, suggesting that the two proteins are likely to have distinct functions in this tissue. Macrophage-specific knockdown of AFABP in the apoE-deficient mouse offers dramatic protection against development of diet-induced atherosclerosis, even though animals remain hypercholesterolemic (5, 14).

It is likely that alterations in inflammatory cytokine production underlie the beneficial effects of AFABP knockdown. Recently, it was demonstrated that macrophage inflammatory responses leading to cytokine production via JNK (c-Jun N-terminal kinase) and AP1 (activator protein-1) require AFABP, the transcription of which is in turn mediated by JNK (15). AFABP has also been shown to be necessary for macrophage endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress response to inflammatory signals (5). As mentioned above for AFABP, KFABP has also been shown to exhibit a subtle conformational change in the helical domain that reveals a cryptic nuclear localization signal upon binding of a PPARβ-activating ligand, resulting in translocation and PPARβ-mediated transcriptional activation (12, 13).

Muscle

Fatty acids contribute a large portion of the energy required in cardiac and skeletal muscles. The major FABP in muscle tissues is heart FABP (HFABP; FABP3). HFABP expression is up-regulated during cardiomyocyte differentiation and is associated with the inhibition of cardiomyocyte proliferation (16). A marked decrease in PA oxidation was observed in HFABP-null cardiac muscle, although β-oxidation capacity was not affected, suggesting that HFABP is required for LCFA transport to maintain efficient mitochondrial β-oxidation. HFABP ablation also causes a dramatic switch in cardiac fuel selection from LCFA to glucose, resulting in reduced tolerance to exercise and cardiac hypertrophy in older animals. HFABP-null mice displayed alterations in both cardiac LCFA uptake and esterification into TG and phospholipids (PLs) (2, 17, 18). Relative levels of PA were increased in the heart PL pool relative to the TG pool. Although arachidonic acid (AA; C20:4ω6) incorporation into both TG and PLs was decreased, the phosphatidylinositol and phosphatidylserine pools were not affected, implying that HFABP helps maintain specific PL pools that may be linked to lipid-mediated signal transduction (2, 17, 18).

The up-regulation of HFABP expression during skeletal muscle differentiation is correlated with increased utilization of LCFA for both β-oxidation and esterification (2, 19). HFABP-null mice showed a decrease in the rate of muscle fatty acid uptake; however, the skeletal muscle had an increased mitochondrial density compared with wild-type mice and could therefore maintain efficient LCFA utilization (2, 19). Glucose oxidation was either increased or inhibited in HFABP-null soleus muscle depending on physiological conditions; thus, the effects of HFABP loss are not as acute in the skeletal compared with cardiac muscle (2, 19).

The effects of HFABP on LCFA utilization have been proposed to occur at the substrate level, to enhance LCFA supply, and also at the regulatory level, by interacting with allosterically modulated enzymes as well as transcription factors (2). The HFABP α-helical domain is involved in the collision-mediated transfer of LCFA from HFABP to acidic membranes, and similar interactions could take place between HFABP and acidic peptide domains to facilitate protein-protein interactions (20). HFABP may also interact with PPARα, a nuclear receptor, to induce the expression of mitochondrial and peroxisomal β-oxidation pathways (12).

Nervous System

Neural membrane PLs contain abundant long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), such as docosahexaenoic (DHA; C22:6ω3) and AA, as well as saturated PA. The central nervous system expresses HFABP in the adult brain, whereas brain FABP (BFABP; FABP7) and KFABP are detected mainly in the pre- and perinatal brain, respectively, with lower levels in the adult brain (3). In contrast, myelin FABP (myelin P2, FABP8) is found predominantly in the peripheral nervous system (21).

In human brain, the concentration of HFABP is ≥10 times higher than that of BFABP in each part of the brain (3, 22), suggesting that HFABP expression may be associated with the maintenance of the differentiation status of adult brain cells (3). Studies with HFABP-null mice have shown that HFABP expression is necessary to maintain the ω6/ω3-PUFA balance in adult brain cells and that decreased HFABP expression lowers the incorporation of AA into brain PLs, in particular phosphatidylinositol (23). An imbalance in the ω6/ω3 ratio of brain membranes is thought to be a factor in the pathogenesis of several neurological and psychiatric disorders (24), and decreased HFABP expression is found in the brains of patients with Down syndrome and Alzheimer disease, providing indirect evidence of a connection between HFABP and neurological function (25–27).

Neurogenesis includes three contiguous phases, namely proliferation, migration and differentiation, and maturation and integration of the precursor cells (28). The expression of BFABP is highest in the midterm embryonic stages of development and is associated with the proliferation of neural progenitor cells during early cortical development (3). The up-regulation of BFABP (and also KFABP) is likely related to the proliferation and initial differentiation of neural cells, rather than their maturation and integration (28). BFABP preferentially binds ω3-PUFA, e.g. DHA (29–31). DHA is a major component of brain phosphatidylethanolamine and phosphatidylserine and is highly enriched in the PLs of the synaptic plasma membrane and synaptic vesicles (32). An increase in BFABP expression is directly correlated with DHA utilization, and BFABP-null mice display decreased DHA incorporation into PLs, with an increase in AA and PA incorporation (3). Interestingly, BFABP expression levels are increased in schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and Down syndrome and have been associated with increased anxiety and depression and altered emotional behavior (3, 25); these disorders are proposed to be linked to ω3-PUFA deficiency via alterations in dopaminergic and serotonergic processes (24).

KFABP is expressed mainly at the late embryonic stages, and its expression is up-regulated during the differentiation of human embryonic stem cells into motor neurons or astrocytes as well as in various pathological conditions, including peripheral nerve injury (3, 33). Thus, KFABP may be required for the mobilization of the LCFA substrates necessary for active synthesis of lipids and membranes in the processes of neurite outgrowth, axon development, and neural cell regeneration (3). In PC12 cells, neurite extension can be stimulated by the expression of KFABP and a simultaneous supply of AA and DHA, supporting a role in membrane biogenesis during neurite outgrowth and axon development (34). It has been proposed that KFABP exerts its cell- and tissue-specific roles via ligand binding and transport as well as ligand-specific interactions with PPARβ/δ (35). Indeed, KFABP has been shown to bind retinoic acid (RA) and deliver this lipid hormone to PPARβ/δ, thus partitioning RA away from the classical RA receptor and leading to the transcription of genes related to cell survival rather than growth inhibition (36).

Myelin FABP is expressed exclusively in the peripheral nervous system myelin sheath during development and is absent from the central nervous system (21). It is proposed to be important for the generation and maintenance of lipid composition of the myelin membranes (37).

Liver

The liver is the major site of very low density lipoprotein biogenesis and cholesterol synthesis as well as the site of bile acid synthesis. Fatty acid oxidative pathways are also active in the liver. It nevertheless expresses only a single FABP at a high level, namely LFABP. This singular expression in such a multifunctional organ may be related to the ligand binding properties of LFABP, which are unique in the FABP family in that two, rather than one, LCFAs are bound to LFABP, and moreover, a variety of other hydrophobic ligands have been shown to bind in its relatively large ligand-binding pocket (4, 38).

LFABP-null mice show diminished hepatic fatty acid β-oxidation in the fasted state that is not due to diminished oxidative capacity or decreases in PPARα or the expression of relevant genes (2, 39–42), supporting the hypothesis that LFABP acts as a LCFA transporter, specifically targeting ligand to β-oxidation pathways. Although LCFA oxidation is decreased, the LFABP-null mouse nevertheless does not develop hepatosteatosis following a high fat diet, indicating protection against development of the metabolic syndrome (2, 39–41); however, others have reported an exacerbation of obesity (42). Recently, it was shown that LFABP-null mice were highly susceptible to the development of cholesterol gallstones, with the effect likely secondary to increased liver cholesterol levels and increased enterohepatic bile acid pool size (43).

LFABP may, in part, be exerting its functional effects via regulation of gene transcription. Despite the absence of PPARα involvement in the diminished β-oxidative response to fasting in the LFABP-null mouse (40, 41), several reports indicate direct interactions between LFABP and PPARα (44, 45), a nuclear receptor involved in the induction of hepatic β-oxidation, and it has been suggested that LFABP is specifically delivering LCFA or perhaps other ligands to the nucleus (45, 46). Unlike what has been shown for AFABP and KFABP, however, the LFABP helix-turn-helix domain does not appear to contain structural information promoting nuclear localization; thus, the molecular basis for LFABP delivery of ligand to the nucleus, as well as the structural basis for the putative LFABP-PPARα association, remains to be determined.

Intestine

The small intestine is responsible for the assimilation of dietary lipid as well as the reuptake of bile acids via the enterohepatic circulation. Differentiated enterocytes of the proximal small intestine express high levels of two FABPs, LFABP and the intestine-specific form, intestinal FABP (IFABP; FABP2). The distal small intestine expresses a third member of the FABP family, ileal bile acid-binding protein (ILBP; FABP6) (47, 48). There appears to be no compensatory up-regulation of LFABP upon ablation of IFABP or vice versa, again indicating unique functional roles. However, LFABP-null mice display an increase in the mRNA levels of ILBP (43, 48), which may be part of the mechanism underlying the increased bile acid pool size and increased gallstone susceptibility.

A unique feature of LFABP in the intestine is its role in chylomicron biogenesis. Cell-free transport studies demonstrated that LFABP is necessary for the release of ER-generated vesicles containing nascent TG-rich chylomicrons, the prechylomicron transport vesicles (PCTVs). Budding of the PCTVs is dependent on LFABP, which cannot be replaced by IFABP (49). Recently, the intestinal ER-derived PCTV budding machinery was shown to be a >600-kDa complex containing LFABP as well as VAMP7, apoB48, CD36, and COPII proteins (50). As found in the liver, the LFABP-null mouse also displays defective fasting-induced fatty acid β-oxidation in the intestine. Total mucosal oxidative capacity is not decreased, and there are no changes in the expression of genes involved in β-oxidation; thus, in the intestine as well as in the liver, LFABP is likely playing a lipid transport/targeting role (51).

Certain unique roles for the two proximal enterocyte FABPs in intracellular lipid metabolism have also been found. LFABP ablation does not substantially alter the incorporation of LCFA into TG or PLs, but monoacylglycerol (MG) metabolism is shifted toward greater TG incorporation in the LFABP-null mucosa, suggesting that LFABP is involved in partitioning of MG toward PL biosynthesis (51). In contrast, IFABP-null animals display no changes in MG metabolism, consistent with the lack of MG binding by IFABP, but rather display a reduced incorporation of OA into TG relative to PLs, suggesting that IFABP is involved in partitioning of LCFA toward TG synthesis (52). In vitro studies of two IFABP-transfected intestinal cell lines, Caco-2 and HIEC-6, reported decreased TG secretion or no change in TG synthesis/secretion, respectively (53, 54). A small effect on OA oxidation was also found; HIEC-6 cells with a 90-fold overexpression of IFABP showed a 65% increase in OA oxidation (54).

As for LFABP, the actions of IFABP in the enterocyte may lead to systemic metabolic effects, although reports are not entirely consistent, and underlying mechanisms are not clear. Under certain conditions related to age, gender, or diet, IFABP-null mice appear to be more prone to developing obesity, hypertriglyceridemia, and increased liver TG accumulation (47, 48), characteristics of the metabolic syndrome. A potential role for IFABP in the development of the metabolic syndrome is also supported by a single nucleotide polymorphism in the IFABP gene that leads to the substitution of threonine for alanine at position 54. The Thr54 isoform binds LCFA with greater affinity than the Ala54 form, suggesting that the elevated postprandial serum lipid levels in individuals carrying the Thr54 allele and the increased lipid secretion found in Thr54 fetal explants are not secondary to greater sequestration of LCFA in the enterocyte but rather may be related to the aforementioned specific role of IFABP in intestinal TG synthesis and/or transport (8, 55).

Summary and Perspective

The functions of fatty acids and other lipids are often highly tissue-specific, and it is becoming clear that the FABPs function in a tissue-specific manner as well (Table 1). The functions of fatty acids and other lipids are often highly tissue-specific, and it is becoming clear that the FABPs function in a tissue-specific manner as well. Thus, despite similar ligand binding characteristics and highly homologous tertiary structures, each FABP appears to have unique functions in specific tissues. Overall, the FABPs function as intracellular LCFA trafficking proteins between particular subcellular sites. The transport properties of the FABPs are governed in part by specific protein-protein and protein-membrane interactions, and the helix-turn-helix domain of the FABPs is critical although likely not exclusive in specifying these interactions. Several of the FABPs have been shown to deliver their ligands to nuclear transcription factors, thus modulating gene expression in a tissue-specific manner. Cellular changes in gene expression and lipid metabolism brought about by the FABPs lead to changes in whole body energy homeostasis. Given the role of aberrant lipid metabolism in most if not all of the metabolic syndrome disorders, the FABPs may be envisioned as central regulators of lipid disposition at the cell and tissue levels that have a profound impact on systemic energy metabolism.

TABLE 1.

FABP Tissue Distribution and Proposed Functional Roles

| FABP expression | Functional roles | Physiological end points | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adipose tissue | |||

| AFABP (very high levels), KFABP (very low levels) | TG storage (interactions with HSL), regulation of fatty acid species abundance, interaction with PPAR nuclear receptors, inflammatory cytokine production | Insulin resistance, metabolic syndrome, inflammatory diseases | 1, 5–7, 9–13 |

| Macrophages | |||

| AFABP and KFABP | Inflammatory cytokine production, mediation of ER stress response, interaction with PPARγ nuclear receptors, interaction with JAK2 signaling pathway | Diet-induced atherosclerosis, other inflammatory diseases | 5, 12–15 |

| Liver | |||

| LFABP | LCFA transport linked to β-oxidation, interaction with PPARα nuclear receptors | Development of metabolic syndrome and exacerbation of obesity, reduction of liver cholesterol and bile acid pools | 2, 39–46 |

| Intestine | |||

| IFABP | LCFA partitioning toward TG synthesis | Protection against obesity, hypertriglyceridemia, liver TG accumulation, and metabolic syndrome | 8, 43, 47, 48, 52–55 |

| ILBP | Bile acid transport | 47, 48 | |

| LFABP | LCFA transport linked to β-oxidation. MG incorporation into PLs, part of PCTV membrane budding complex | Chylomicron biogenesis | 43, 49–51 |

| Brain | |||

| Central nervous systema | |||

| BFABP | Neural utilization of DHA in membrane synthesis and signaling | Proliferation of neural progenitor cells and midterm stages of embryonic development; initial differentiation of neural cells; linked to schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, Down syndrome, and emotional behavior | 3, 24, 25, 28–31 |

| HFABP | Incorporation of AA into brain PLs, maintenance of ω6/ω3-PUFA balance | Maintenance of differentiation status of adult brain, linked to Down syndrome, Alzheimer disease, and neurological function | 3, 22, 23, 25–27 |

| KFABP | LCFA supply and membrane biogenesis, interaction with nuclear receptors (e.g. PPARβ/δ), utilization of RA | Neurite outgrowth and axon development, differentiation of neural cells, up-regulated under pathological conditions (e.g. nerve injury) | 3, 28, 33, 34, 36 |

| Peripheral nervous system | |||

| MFABP | LCFA supply and membrane biogenesis | Development of myelin sheath | 21, 37 |

| Muscle tissue | |||

| Cardiac | |||

| HFABP | LCFA transport linked to β-oxidation, trafficking of LCFA to specific PL pools, interaction with nuclear receptors (e.g. PPARα) | Cardiomyocyte differentiation and inhibition of cardiomyocyte proliferation, lipid fuel utilization | 2, 12, 16–18 |

| Skeletal | |||

| HFABP | LCFA transport linked to β-oxidation and esterification, interaction with nuclear receptors (e.g. PPARα) | Skeletal muscle differentiation | 2, 12, 19 |

a Expression of FABPs in the central nervous system shows spatiotemporal distribution patterns, as described in the text.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant DK38389 (to J. S.). This work was also supported by the New Jersey Agricultural Experiment Station (to J. S.) and the Faculty of Health and Medical Sciences, University of Surrey (to A. E. T.). This minireview will be reprinted in the 2010 Minireview Compendium, which will be available in January, 2011.

- FABP

- fatty acid-binding protein

- LCFA

- long-chain fatty acid

- LFABP

- liver FABP

- TG

- triacylglycerol

- AFABP

- adipocyte FABP

- KFABP

- keratinocyte FABP

- HSL

- hormone-sensitive lipase

- PA

- palmitate

- OA

- oleate

- PPAR

- peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor

- ER

- endoplasmic reticulum

- HFABP

- heart FABP

- PL

- phospholipid

- AA

- arachidonic acid

- PUFA

- polyunsaturated fatty acid

- DHA

- docosahexaenoic acid

- BFABP

- brain FABP

- RA

- retinoic acid

- IFABP

- intestinal FABP

- ILBP

- ileal bile acid-binding protein

- PCTV

- prechylomicron transport vesicle

- MG

- monoacylglycerol.

REFERENCES

- 1.Storch J., McDermott L. (2009) J. Lipid Res. 50, (suppl.) S126–S131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Binas B., Erol E. (2007) Mol. Cell. Biochem. 299, 75–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Owada Y. (2008) Tohoku J. Exp. Med. 214, 213–220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Richieri G. V., Ogata R. T., Zimmerman A. W., Veerkamp J. H., Kleinfeld A. M. (2000) Biochemistry 39, 7197–7204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Erbay E., Babaev V. R., Mayers J. R., Makowski L., Charles K. N., Snitow M. E., Fazio S., Wiest M. M., Watkins S. M., Linton M. F., Hotamisligil G. S. (2009) Nat. Med. 15, 1383–1391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shaughnessy S., Smith E. R., Kodukula S., Storch J., Fried S. K. (2000) Diabetes 49, 904–911 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coe N. R., Simpson M. A., Bernlohr D. A. (1999) J. Lipid Res. 40, 967–972 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Storch J., Corsico B. (2008) Annu. Rev. Nutr. 28, 73–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maeda K., Cao H., Kono K., Gorgun C. Z., Furuhashi M., Uysal K. T., Cao Q., Atsumi G., Malone H., Krishnan B., Minokoshi Y., Kahn B. B., Parker R. A., Hotamisligil G. S. (2005) Cell Metab. 1, 107–119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smith A. J., Sanders M. A., Juhlmann B. E., Hertzel A. V., Bernlohr D. A. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 33536–33543 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cao H., Gerhold K., Mayers J. R., Wiest M. M., Watkins S. M., Hotamisligil G. S. (2008) Cell 134, 933–944 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tan N. S., Shaw N. S., Vinckenbosch N., Liu P., Yasmin R., Desvergne B., Wahli W., Noy N. (2002) Mol. Cell. Biol. 22, 5114–5127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gillilan R. E., Ayers S. D., Noy N. (2007) J. Mol. Biol. 372, 1246–1260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Layne M. D., Patel A., Chen Y. H., Rebel V. I., Carvajal I. M., Pellacani A., Ith B., Zhao D., Schreiber B. M., Yet S. F., Lee M. E., Storch J., Perrella M. A. (2001) FASEB J. 15, 2733–2735 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hui X., Li H., Zhou Z., Lam K. S., Xiao Y., Wu D., Ding K., Wang Y., Vanhoutte P. M., Xu A. (2010) J. Biol. Chem. 285, 10273–10280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tang M. K., Kindler P. M., Cai D. Q., Chow P. H., Li M., Lee K. K. (2004) Cell Tissue Res. 316, 339–347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schaap F. G., Binas B., Danneberg H., van der Vusse G. J., Glatz J. F. (1999) Circ. Res. 85, 329–337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Binas B., Danneberg H., McWhir J., Mullins L., Clark A. J. (1999) FASEB J. 13, 805–812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Erol E., Cline G. W., Kim J. K., Taegtmeyer H., Binas B. (2004) Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 287, E977–E982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liou H. L., Kahn P. C., Storch J. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 1806–1815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Trapp B. D., Dubois-Dalcq M., Quarles R. H. (1984) J. Neurochem. 43, 944–948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Myers-Payne S. C., Hubbell T., Pu L., Schnütgen F., Börchers T., Wood W. G., Spener F., Schroeder F. (1996) J. Neurochem. 66, 1648–1656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Murphy E. J., Owada Y., Kitanaka N., Kondo H., Glatz J. F. (2005) Biochemistry 44, 6350–6360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chalon S. (2006) Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fatty Acids 75, 259–269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cheon M. S., Kim S. H., Fountoulakis M., Lubec G. (2003) J. Neural Transm. Suppl. 67, 225–234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Watanabe A., Toyota T., Owada Y., Hayashi T., Iwayama Y., Matsumata M., Ishitsuka Y., Nakaya A., Maekawa M., Ohnishi T., Arai R., Sakurai K., Yamada K., Kondo H., Hashimoto K., Osumi N., Yoshikawa T. (2007) PLoS Biol. 5, e297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sánchez-Font M. F., Bosch-Comas A., Gonzàlez-Duarte R., Marfany G. (2003) Nucleic Acids Res. 31, 2769–2777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Boneva N. B., Kaplamadzhiev D. B., Sahara S., Kikuchi H., Pyko I. V., Kikuchi M., Tonchev A. B., Yamashima T. (2010) Hippocampus, in press [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hanhoff T., Lücke C., Spener F. (2002) Mol. Cell. Biochem. 239, 45–54 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xu L. Z., Sánchez R., Sali A., Heintz N. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271, 24711–24719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Balendiran G. K., Schnutgen F., Scapin G., Borchers T., Xhong N., Lim K., Godbout R., Spener F., Sacchettini J. C. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 27045–27054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Glomset J. A. (2006) Sci. STKE 2006, e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.De León M., Welcher A. A., Nahin R. H., Liu Y., Ruda M. A., Shooter E. M., Molina C. A. (1996) J. Neurosci. Res. 44, 283–292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu J. W., Almaguel F. G., Bu L., De Leon D. D., De Leon M. (2008) J. Neurochem. 106, 2015–2029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schug T. T., Berry D. C., Toshkov I. A., Cheng L., Nikitin A. Y., Noy N. (2008) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 7546–7551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schug T. T., Berry D. C., Shaw N. S., Travis S. N., Noy N. (2007) Cell 129, 723–733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kursula P. (2008) Amino Acids 34, 175–185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.He Y., Yang X., Wang H., Estephan R., Francis F., Kodukula S., Storch J., Stark R. E. (2007) Biochemistry 46, 12543–12556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Newberry E. P., Xie Y., Kennedy S. M., Luo J., Davidson N. O. (2006) Hepatology 44, 1191–1205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Erol E., Kumar L. S., Cline G. W., Shulman G. I., Kelly D. P., Binas B. (2004) FASEB J. 18, 347–349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Newberry E. P., Xie Y., Kennedy S., Han X., Buhman K. K., Luo J., Gross R. W., Davidson N. O. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 51664–51672 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Atshaves B. P., McIntosh A. L., Storey S. M., Landrock K. K., Kier A. B., Schroeder F. (2010) Lipids 45, 97–110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Xie Y., Newberry E. P., Kennedy S. M., Luo J., Davidson N. O. (2009) J. Lipid Res. 50, 977–987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hostetler H. A., McIntosh A. L., Atshaves B. P., Storey S. M., Payne H. R., Kier A. B., Schroeder F. (2009) J. Lipid Res. 50, 1663–1675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wolfrum C. (2007) Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 64, 2465–2476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McIntosh A. L., Atshaves B. P., Hostetler H. A., Huang H., Davis J., Lyuksyutova O. I., Landrock D., Kier A. B., Schroeder F. (2009) Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 485, 160–173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vassileva G., Huwyler L., Poirier K., Agellon L. B., Toth M. J. (2000) FASEB J. 14, 2040–2046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Agellon L. B., Drozdowski L., Li L., Iordache C., Luong L., Clandinin M. T., Uwiera R. R., Toth M. J., Thomson A. B. (2007) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1771, 1283–1288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Neeli I., Siddiqi S. A., Siddiqi S., Mahan J., Lagakos W. S., Binas B., Gheyi T., Storch J., Mansbach C. M., 2nd (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 17974–17984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Siddiqi S., Saleem U., Abumrad N. A., Davidson N. O., Storch J., Siddiqi S. A., Mansbach C. M., 2nd (2010) J. Lipid Res. 51, 1918–1928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lagakos W. S., Storch J., Zhou Y. X., Mandap B., Binas B. (2007) FASEB J. 21, LB35 [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lagakos W., Storch J., Zhou Y. X., Russnak T., Agellon L. (2009) FASEB J. 23, 521 [Google Scholar]

- 53.Levy E., Ménard D., Delvin E., Montoudis A., Beaulieu J. F., Mailhot G., Dubé N., Sinnett D., Seidman E., Bendayan M. (2009) Histochem. Cell Biol. 132, 351–367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Montoudis A., Seidman E., Boudreau F., Beaulieu J. F., Menard D., Elchebly M., Mailhot G., Sane A. T., Lambert M., Delvin E., Levy E. (2008) J. Lipid Res. 49, 961–972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Baier L. J., Sacchettini J. C., Knowler W. C., Eads J., Paolisso G., Tataranni P. A., Mochizuki H., Bennett P. H., Bogardus C., Prochazka M., Bennett P. H. (1995) J. Clin. Invest. 95, 1281–1287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Young A. C., Scapin G., Kromminga A., Patel S. B., Veerkamp J. H., Sacchettini J. C. (1994) Structure 2, 523–534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]