Abstract

Apoptosis is driven by positive feedback activation between aspartate-specific cysteinyl proteases (caspases). These feedback loops ensure the swift and efficient elimination of cells upon initiation of apoptosis execution. At the same time, the signaling network must be insensitive to erroneous, mild caspase activation to avoid unwanted, excessive cell death. Sublethal caspase activation in fact was shown to be a requirement for the differentiation of multiple cell types but might also occur accidentally during short, transient cellular stress conditions. Here we carried out an in silico comparison of the molecular mechanisms that so far have been identified to impair the amplification of caspase activities via the caspase-8, -3, -6 loop. In a systems model resembling HeLa cervical cancer cells, the dimerization/dissociation balance of caspase-8 potently suppressed the amplification of caspase responses, surprisingly outperforming or matching known caspase-8 and -3 inhibitors such as bifunctional apoptosis repressor or x-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein. These findings were further substantiated in global sensitivity analyses based on combinations of protein concentrations from the sub- to superphysiological range to screen the full spectrum of biological variability that can be expected within cell populations and between distinct cell types. Additional modeling showed that the combined effects of x-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein and caspase-8 dimerization/dissociation processes can also provide resistance to larger inputs of active caspases. Our study therefore highlights a central and so far underappreciated role of caspase-8 dimerization/dissociation in avoiding unwanted cell death by lethal amplification of caspase responses via the caspase-8, -3, -6 loop.

Keywords: Apoptosis, Caspase, Computation, Computer Modeling, Mathematical Modeling, Bifunctional Apoptosis Regulator (BAR), Sensitivity Analysis, Systems Biology, x-linked Inhibitor of Apoptosis Protein (XIAP)

Introduction

Apoptosis is an evolutionary conserved cell death mechanism crucial for both tissue homeostasis and the continuous removal of superfluous or damaged cells from the bodies of all metazoans. Unbalanced apoptotic signaling results in developmental defects and contributes to multiple diseases, including autoimmune and neurological disorders as well as cancer (1). Due to the central role of apoptotic signaling for human health and its grave consequence on cell fate (life/death), apoptotic signaling networks have become a major focus for cellular and molecular systems biological research (2).

The execution of apoptotic cell death is expedited by sequential activation of apoptotic initiator and effector caspases, proteases that reside in cells as inactive zymogens. Activation is thought to be enhanced by positive feedback loops between initiator and effector caspases (3, 4). Initiator caspases such as caspase-8 and -9 require binding to multiprotein platforms for their activation, resulting in autoproteolysis into small and large subunits that take up the mature heterotetrameric caspase conformation (4, 5). Procaspase-8 is activated at the death-inducing signaling complex (DISC).2 This multiprotein complex is formed at the plasma membrane in response to external ligands that bind to death receptors on the cell surface, and both dimerization and proteolytic processing of procaspase-8 are required to form a caspase-8 dimer capable of initiating apoptosis (6, 7). Procaspase-9 instead is activated at the cytosolic apoptosome complex as the consequence of an apoptotic signaling cascade emanating from permeabilized mitochondria (5). Both these initiator caspases can proteolytically activate effector caspase-3 and -7 (4, 5). Of these, caspase-3 directly or indirectly induces the majority of the morphological and biochemical hallmarks of apoptotic cell death, such as cytoskeletal collapse, loss of phospholipid asymmetry in the plasma membrane, and apoptotic plasma membrane blebbing. Caspase-3 also activates effector caspase-6, which cleaves procaspase-8 and thereby is believed to close a positive feedback loop between caspase-8, -3, and -6 (3, 8). Likewise, caspase-3 initiates another positive feedback by cleaving the x-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein (XIAP) binding motif off the small caspase-9 subunit (9), thereby rendering it insensitive to this potent caspase inhibitor.

In so-called type I cells, the caspase-8, -3, -6 loop is thought to be a major pathway for activating effector caspases in response to death ligands, whereas type II cells depend on the mitochondrial pathway for apoptosis execution (10), suggesting potent inhibition of the caspase-8, -3, -6 loop in the latter scenario. Furthermore, mild non-lethal caspase-8 and -3 activities have been demonstrated to be a physiological prerequisite in various scenarios of cellular proliferation and differentiation (reviewed in Refs. 11 and 12), rather than leading to cell death by feedback amplification. Sufficient inhibitory mechanisms also must be in place to avoid unwanted cell death in response to mild, temporary or spontaneous, accidental activation of small amounts of caspases, as might occur during transient stress conditions.

Here we constructed and analyzed computational biochemical models to quantitatively compare the potential of known anti-apoptotic molecular mechanisms in suppressing feedback amplification via the caspase-8, -3, -6 loop. This was performed initially for a scenario representing the physiological cellular context of type II HeLa cervical cancer cells and was subsequently expanded to a global analysis spanning the entire phase space to cover the biological variability that can be expected within cell populations and between different cell types.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Model Implementation, Parameterization, and Perturbation

All models were implemented as ordinary differential equations based on mass action kinetics. Process diagrams according to the systems biology graphical notation are provided as supplemental Fig. 4. For model parameterization, the kinetics for the dimerization/dissociation balance between processed caspase-8 monomers and active caspase-8 dimers were derived from experimental data published by Pop et al. (13). The authors force-dimerized caspase-8 species with the help of Hoffmeister salts to obtain starting material for experiments on dissociation kinetics. Although force dimerization is not a physiological scenario, these experiments allowed them to determine the rate constants for the dimerization/dissociation processes as required for this study. The equilibrium binding constant Kd for caspase-8 was determined as 3.3 μm. The decrease of caspase-8 activity due to the dissociation of active dimers into monomers was determined as 27 min.3 This half-time can also be appreciated from Fig. 5B in Ref 13. Based on the equation for the relation between the half-life and the rate constant for a first order reaction, a koff of 0.0257 min−1 was calculated

With the ratio of koff to kon being the equilibrium binding constant Kd, kon was calculated as 7788 m−1 min−1 using

FIGURE 5.

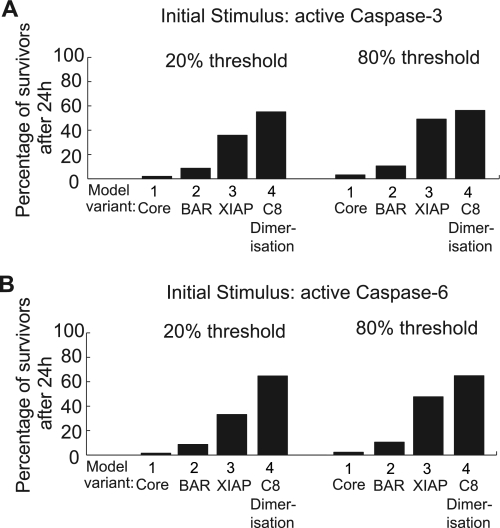

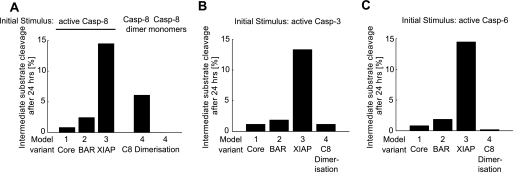

Global analysis of feedback attenuation upon mild systems perturbation via caspase-3 or -6. A global sensitivity analysis as shown in Fig. 4 was conducted for mild systems perturbations via caspase-3 or -6. A, end point comparison upon perturbation by caspase-3. The percentages of simulated conditions not reaching 20 or 80% substrate cleavage within 24 h are shown. C8, caspase-8. B, end point comparison upon perturbation by caspase-6. The percentages of simulated conditions not reaching 20 or 80% substrate cleavage within 24 h are shown. Like in Fig. 4, these comparisons allowed us to rank the distinct inhibitory mechanisms according to their potency for scenarios in which caspase-3 or -6 was used as input stimuli.

Concentrations for procaspase-8 and -6 in HeLa cervical cancer cells were determined by comparative quantitative Western blotting using whole cell extracts of HeLa and SKW6.4 cells. Other concentrations and reaction constants were taken from literature published previously. Detailed tables for the model parameterization and associated reference publications are listed in the supplemental tables.

For the numerical solution of the respective reaction networks, we used MATLAB-based scripts employing the ODE15s solver for ordinary differential equations, which implemented a backward differentiation formula for numerical integration. Scripts used in this study are available as supplemental Datasets S1 and S2. The distinct model variants described in the main body of this report were perturbed with the concentration equivalent of one processed active caspase-8, -3, or -6 heterodimer bearing two catalytic sites to represent a scenario of residual spontaneous, or accidental caspase activation. Methodologically, the ordinary differential equations modeling approach omitted stochastic effects and concentration discretization representing low numbers of reactants. Stochastic modeling would have required a more complex mathematical formalism and a multitude of repeats for each modeled condition to determine a mean response time but would not have affected the qualitative ranking of the potency of caspase-8 dimerization/dissociation, XIAP, and bifunctional apoptosis regulator (BAR).

Global Sensitivity Analysis

The global sensitivity analysis covered a range of 12 different concentrations from 0.5 nm to 2 μm for each of the procaspases as well as for XIAP and BAR and was performed for input perturbations via caspase-8, -3, and -6. In total, 136,512 different simulations were performed to screen the whole range of biological variability that can be expected between different cells and cell types. To decrease the duration of the computations, the MATLAB script was programmed to allow splitting and distributing the simulations across multiple computers. Results were stored as MATLAB data files and were analyzed subsequently for the time required for caspase-3 to cleave defined amounts of substrate as an indicator for cellular apoptotic responsiveness.

RESULTS

Network Topologies and Model Parameterization

The attenuation of caspase amplification via the caspase-8, -3, -6 loop is a matter of controversial discussion. Although inhibitors or inhibitory processes affecting caspase-8 or -3 activation have been characterized in great detail in isolation, information on their relative potency in attenuating the amplification of caspase activities in the presence of the entire caspase-8, -3, -6 loop is lacking. To obtain this information, we chose a mathematical approach of modeling reactions networks that was based on the published biochemical knowledge on the individual reactants.

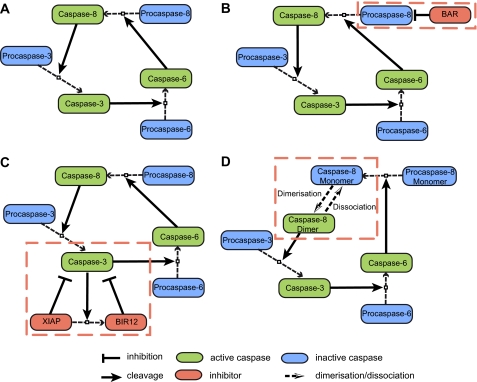

We first devised a core model consisting solely of procaspase-8, -3, and -6 (Fig. 1A, model variant 1). In this core model, no inhibitory processes were present, and cleavage of procaspases directly yielded active caspases. This core model was then expanded to separately compare and rank three known inhibitory mechanisms of the type I loop. (i) BAR, a protein that was proposed to inhibit caspase-8 activation (14), was introduced in the first model variant (Fig. 1B, model variant 2). BAR binds to procaspase-8, and only the fraction of procaspase-8 that is not bound to BAR is available for activation. Due to potential polyubiquitylation by the BAR RING domain, an enhanced degradation of the procaspase-8 fraction that is bound to BAR was taken into account as well. Although this function has not yet been conclusively shown experimentally, it ensured that the inhibitory potential of BAR was not underestimated in this study. (ii) In the second adaptation (Fig. 1C, model variant 3), the XIAP was implemented as an inhibitor of caspase-3. Active caspase-3 can cleave XIAP into two fragments, of which the NH2-terminal cleavage product (BIR12) maintains the capability to inhibit caspase-3 (15). The E3 ubiquitin ligase activity of full-length XIAP was taken into account in the model as well and was implemented to result in enhanced degradation of inactivated caspase-3. (iii) Direct cleavage of procaspase-8 monomers by other caspases, i.e. processing of procaspase-8 outside of the DISC, requires the subsequent dimerization of the processed caspase-8 monomers (comprised of small and large subunits) to form an active heterotetramer. Taking into account the caspase-8 dimerization/dissociation balance therefore could present a potent inhibitory mechanism that avoids spontaneous amplification of caspase activities via the caspase-8, -3, -6 loop. The kinetic characteristics determining the dimerized and dissociated fractions of caspase-8 were recently characterized (13) and were implemented in a third extension of the core model (Fig. 1D, model variant 4; see also “Experimental Procedures”).

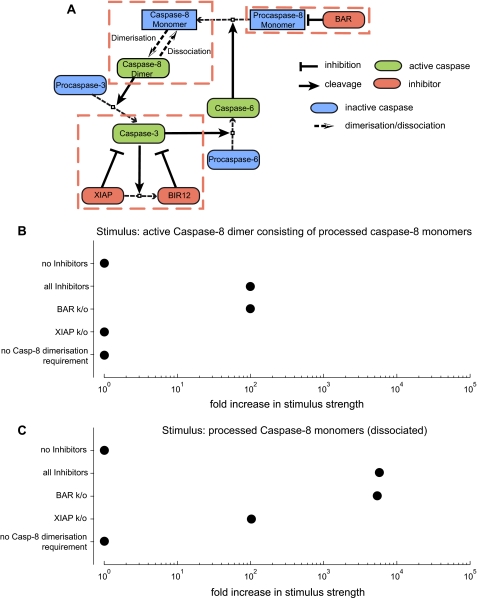

FIGURE 1.

Network topologies. To investigate the efficiency of different molecular mechanisms in attenuating activity amplification between caspase-8, -3, and -6, four distinct network topologies were implemented. All model variants provided substrate cleavage by caspase-3 as an output. This output was employed to evaluate the extent and timing of apoptosis execution. All models also took protein production and degradation into account, which is not explicitly visualized here. Detailed process diagrams according to the guidelines of the systems biology graphical notation (40) are provided as supplemental Fig. 4. A, the core model consisted of the caspase-8, -3, -6 amplification loop in the absence of inhibitory mechanisms. Cleavage of procaspases directly resulted in activation of the target caspases. B, extension of the core model by caspase-8 inhibitor BAR. BAR binds to procaspase-8, and only the fraction of procaspase-8 that is not bound to BAR is available for activation. Enhanced protein turnover due to potential polyubiquitylation by the BAR RING domain was taken into account as well. C, extension of the core model by XIAP, an inhibitor of caspase-3. XIAP can be cleaved by caspase-3, resulting in the BIR12 fragment. Full-length XIAP exerts E3 ubiquitin ligase activity and was modeled to result in enhanced degradation of inactivated caspase-3. D, extension of the core model by taking caspase-8 dimerization into account. Cleavage of procaspase-8 yields processed but inactive caspase-8 monomers, which need to dimerize to yield an active caspase-8 dimer. In reverse, active caspase-8 dimers can dissociate into inactive caspase-8 monomers.

It is important to note that all four model variants need to be considered as biologically incomplete because they contain either none or only one inhibitory process. However, the comparison of the potencies of the distinct inhibitory processes within the caspase-8, -3, -6 loop can only be achieved by investigating them separately. It is furthermore noteworthy that a comparison of the inhibitory potential of BAR versus XIAP versus caspase-8 dimerization/dissociation within the context of the caspase-8, -3, -6 loop cannot be performed experimentally. Caspase-8 dimerization/dissociation is an intrinsic feature of the loop and cannot be removed to examine the inhibitory power of BAR or XIAP in isolation. Therefore, the analysis of the relative inhibitory potency represents an experimentally inaccessible research question that however can be addressed by a systems modeling approach.

For simulations, the above network topologies were coded by sets of ordinary differential equations and allowed to calculate and visualize the changes in all protein fractions over time. The binding constants and catalytic rates for protein interactions and enzyme activities (kon, koff, kcat) were taken from previously published biochemical studies and characterizations as listed and cited in supplemental Tables 3–6. The dissociation constant of the active caspase-8 dimer was deducted from experiments published previously (13) as described under “Experimental Procedures.” All these parameters characterize the biochemical behavior of their respective reactants and are valid across different cell types. Different cell types and cell lines, however, can show significant variability in the expression of individual proteins. Initially, the protein quantities in the core model and its variants were therefore adjusted to values representing HeLa cervical cancer cells (supplemental Table 7). HeLa cells by now have become a key experimental reference system for systems biological studies of apoptotic cell death (16–19) and were classified as type II signaling cells in response to extrinsic apoptosis induction by death receptor ligands such as CD95L or tumor necrosis factor related apoptosis inducing ligand (20, 21). Type II cells require mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization and the release of cytochrome c and Smac into the cytosol to efficiently activate effector caspases and undergo apoptosis execution. Amplification via the caspase-8, -3, -6 loop upon mild, submaximal stimulation therefore should be strongly inhibited in type II HeLa cells. The potency of the inhibitors in the distinct model variants therefore could be tested against this biological a priori knowledge. The protein concentrations in HeLa cells were experimentally measured by us previously (caspase-3, XIAP) (16), were determined experimentally de novo for this study by comparative quantitative Western blotting (caspase-8 and -6), or were taken from a previously published systems model for HeLa cells (BAR) (22).

The Dimerization/Dissociation Balance of Caspase-8 Is the Most Potent Attenuator of the Caspase-8, -3, -6 Loop in a Systems Model Resembling HeLa Cervical Cancer Cells

We evaluated the potential of BAR, XIAP, or caspase-8 dimerization/dissociation to avoid unwanted apoptosis execution in the distinct model variants upon mild stimulation of the caspase-8, -3, -6 loop at type II HeLa cell conditions. To this end, we investigated the temporal profiles of the different protein species in these scenarios and calculated the cleavage kinetics of caspase-3 substrates. Determining the onset and extent of substrate cleavage by caspase-3 served to rank the inhibitory mechanisms according to their efficiency in blocking signal amplification and apoptosis execution (Fig. 2).

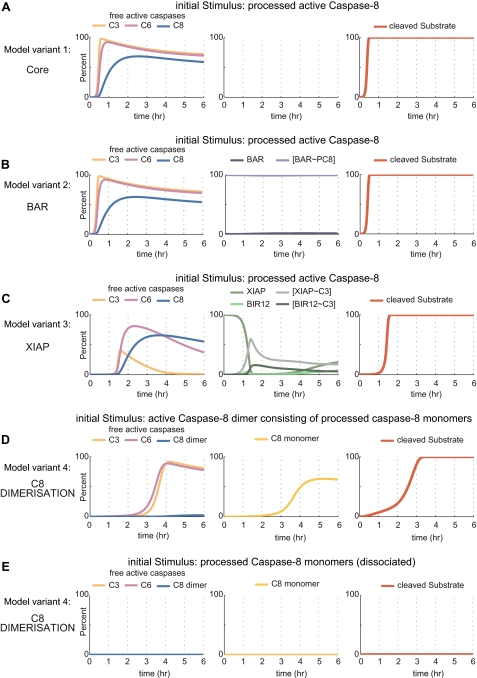

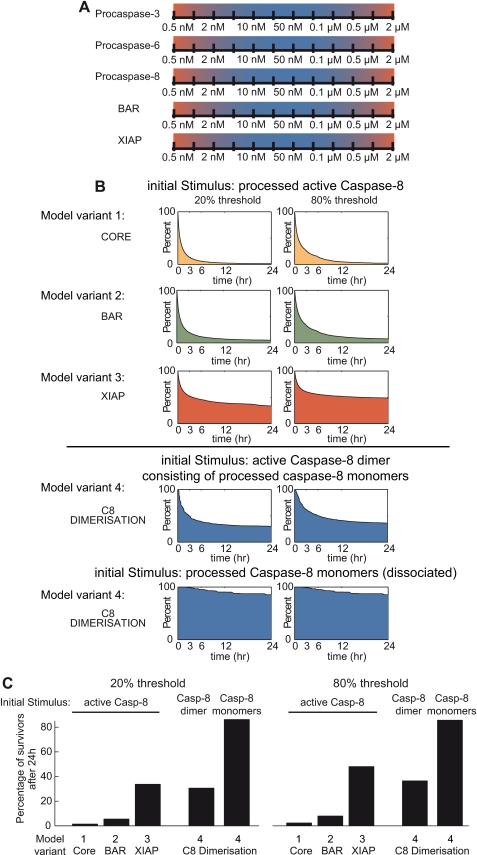

FIGURE 2.

Caspase activation and substrate cleavage profiles in a HeLa cell model upon mild perturbation via caspase-8. The distinct model variants (core model, BAR extension, XIAP extension, caspase-8 dimerization/dissociation extension) were mildly perturbed by the addition of low amounts of processed active caspase-8. This input perturbation biologically reflects caspase-8 dimers, although the model variants used in A–C do not explicitly take the dimerization requirement of caspase-8 into account. The different panels depict the proteins and protein complexes, which are generated as products in response to the initial perturbation. The generation of free, active caspase variants is shown in the left panels. For simplicity, traces depicting the processing of the inactive procaspases are not shown. Temporal profiles of inhibitor proteins or protein complexes consisting of inhibitors bound to caspases are depicted in the middle panels. Substrate cleavage by caspase-3 is shown in the right panels and served to investigate whether the amplification of effector caspase activity can be attenuated effectively. y axes are showing percentage scales with 100% representing the initial amounts of procaspases (left panels) or inhibitory proteins (middle panels). A, model variant 1, simulation of the uninhibited core model of the caspase-8, -3, -6 loop. C3, caspase-3; C6, caspase-6; C8, caspase-8. B, model variant 2, results for the simulation of the caspase-8, -3, -6 loop in the presence of BAR. BAR binds to procaspase-8 and prevents it from being processed. Because procaspase-8 is present in relative abundance when compared with BAR in the HeLa cell scenario, caspase-8 can be activated (left panel) without the pool of BAR-procaspase-8 being noticeably affected. PC8, procaspase-8. C, model variant 3, results for the simulation of the caspase-8, -3, -6 loop in the presence of caspase-3 inhibitor XIAP. Full-length XIAP as well as the BIR12 cleavage fragment can bind and inhibit active caspase-3. D and E, model variant 4, results for the simulation of the caspase-8, -3, -6 loop extended by caspase-8 dimerization/dissociation. The perturbation of this model variant was performed in two distinct modes, representing opposite ends of the caspase-8 dimerization/dissociation balance. The input consisted of either fully mature dimerized active caspase-8 (D) or processed caspase-8 monomers, which first have to dimerize to become active (E). In D and E, the middle panels show processed, inactive caspase-8 monomers.

Stimulating the core model via caspase-8 resulted in an early, concomitant, and rapid amplification of all caspase species, provoking swift and complete substrate cleavage within 15 min (Fig. 2A). The model variant including BAR indicated that active caspases accumulated similar to those in the core model (Fig. 2B). Approximately 100% of BAR remained bound to procaspase-8 (Fig. 2B, middle panel). This can be explained by procaspase-8 being present in relative abundance when compared with BAR in HeLa cells (see supplemental Table 7). Caspase-8 therefore can be activated without the pool of BAR-procaspase-8 being noticeably affected. Like in the core model, appreciable substrate cleavage started at ∼15 min and reached completion after about 30 min (Fig. 2B). In the presence of XIAP, significant amounts of active caspases are only accumulating ∼90 min after network stimulation, and the presence of XIAP prevented caspase-3 from exceeding values above 45% (Fig. 2C). The accumulation of free, active caspase-3 coincided with the time upon which full-length XIAP was consumed and the fractions of XIAP or the BIR12 fragment peaked in their interaction with caspase-3 (Fig. 2C). Onset of substrate cleavage was detectable at about 60 min and was completed at ∼90 min (Fig. 2C).

The perturbation of the model variant including caspase-8 dimerization/dissociation was performed in two distinct modes, representing opposite ends of the caspase-8 dimerization/dissociation balance. The input consisted of either (i) fully mature processed dimerized caspase-8 (Fig. 2D) or (ii) processed caspase-8 monomers, which first had to dimerize to become active (Fig. 2E). Upon perturbation with dimeric caspase-8, the fractions of caspase-3 and -6 started to increase after ∼2–3 h, whereas the amounts of dimeric caspase-8 remained very low at all times (Fig. 2D). The latter could be attributed to caspase-8 remaining largely in its monomeric form (Fig. 2D). Substrate cleavage by caspase-3 displayed an initial ramp that indicated low activity (30–120 min) followed by faster substrate cleavage at a time coinciding with increased caspase-3 activation and reached completion after 3 h (Fig. 2D). In stark contrast, no noteworthy amounts of active caspase species were calculated when initiating this model variant by processed caspase-8 monomers (Fig. 2E), indicating that the requirement for monomer association strongly impairs signal amplification. Correspondingly, no significant substrate cleavage was detected during the first 6 simulated hours (Fig. 2E). Extended simulations covering 24 h provided equivalent results (supplemental Fig. 1).

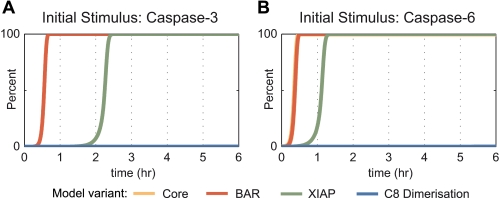

Perturbation of the distinct model variants via inputs of caspase-3 or caspase-6 suggested the same ranking; XIAP was more potent than BAR in delaying substrate cleavage, whereas caspase-8 dimerization/dissociation effectively abolished signal amplification (Fig. 3, A and B). We also repeated all simulations for conditions resembling type I SKW6.4 cells (parameters listed in supplemental Table 8). For protein compositions as found in a type I signaling system, the caspase-8, -3, -6 loop would be expected to more rapidly amplify caspase activities. Indeed, the model variants for SKW6.4 conditions showed a higher responsiveness toward stimulation because substrate cleavage occurred at earlier times when compared with type II HeLa cell conditions (supplemental Fig. 2). Qualitatively, the potency ranking yielded results corresponding to the HeLa cell scenario, with caspase-8 dimerization/dissociation being more potent than XIAP or BAR in attenuating signal amplification (supplemental Fig. 2). Taken together, these results indicate that the caspase-8, -3, -6 loop could most effectively be attenuated by the requirement of processed caspase-8 monomers to dimerize into an active caspase-8, irrespective of the chosen input perturbation.

FIGURE 3.

Caspase activation and substrate cleavage profiles in a HeLa cell model upon mild perturbation via caspase-3 or -6. The distinct model variants were mildly perturbed by the addition of active caspase-3 (A) or by the addition of active caspase-6 (B). Substrate cleavage by caspase-3 is shown here to compare the efficiency of feedback attenuation by BAR, XIAP, or caspase-8 dimerization/dissociation. The response of the model variant including BAR largely superimposed with the core model. The inclusion of caspase-8 (C8) dimerization/dissociation was the most efficient inhibitory process, followed by XIAP.

Global Sensitivity Analysis Identifies That the Dimerization/Dissociation Balance of Caspase-8 Is a Potent Attenuator of the Caspase-8, -3, -6 Loop

The human body comprises more than 200 different cell types, with diversities in cellular proteomes being central to bringing about distinct cell functionalities. Furthermore, protein profiles may change with progression through cell cycle phases or during adaptation to altered environmental conditions and were also shown to differ between individual cells within clonal cell populations due to noise in protein turnover (23, 24). Analyzing a single cellular context therefore is not sufficient to evaluate the relative power of the molecular mechanisms that inhibit the caspase-8, -3, -6 loop. We therefore conducted a global sensitivity analysis for all model variants, which encompassed 136,512 simulations. These simulations screened concentration combinations from the sub- to superphysiological range (0.5 nm to 2 μm) to reflect the biological variability that can reasonably be expected between cells and distinct cell types (Fig. 4A). Simulations covered 24 h and were analyzed for the time required for caspase-3 to cleave 20 or 80% substrate to determine the “time of death” for each individual run. These substrate cleavage thresholds were based on previously published data, which indicated that HeLa cells cleaving less than 20% substrate subsequently did not show morphological features of apoptosis, whereas cells cleaving 80% substrate always underwent efficient apoptosis execution (16).

FIGURE 4.

Global analysis of feedback attenuation upon mild systems perturbation via caspase-8. A, concentration ranges for the global sensitivity analysis. Each dimension of protein concentrations was discretized into 12 steps, ranging from sub- to superphysiological ranges. Extremes are highlighted in red. Using all possible combinations of protein concentrations from these concentration ranges, large numbers of individual simulations were performed to cover the variability that can be expected between cells and different cell types. B, survival plots for the simulation collectives of the distinct model variants. For each model variant, the global sensitivity analysis yielded a collective of individual simulations. Each simulation in the respective collectives was analyzed for the time when either 20 or 80% of substrate was cleaved. To visualize the susceptibility of the model variants to commit apoptosis, we generated survival plots. At time 0, these plots start with the entirety of simulated conditions (100%). As soon as a simulation reached 20 or 80% substrate cleavage, it was removed from the respective collective. This allowed us to display the percentage of “surviving” conditions against time. C8, caspase-8. C, end point comparison of survival plots. The percentage of simulated conditions not reaching 20 or 80% substrate cleavage within 24 h was compared for the different model variants. This comparison allowed us to rank the distinct inhibitory mechanisms according to their potency. Casp-8, caspase-8.

We initially performed the global sensitivity analysis using dimerized active caspase-8 as the input. For all model variants, we plotted the respective simulation collectives against time and removed individual runs once they reached either 20 or 80% substrate cleavage. This allowed us to generate survival plots that displayed the percentage of simulations that had not undergone apoptosis execution against time (Fig. 4B). As expected, for the core model, essentially no survivors could be identified (Fig. 4, B and C). The BAR-extended variant yielded low percentages of survivors (5 or 8% for thresholds of 20 or 80% substrate cleavage, respectively), whereas the XIAP-extended variant performed far better with 33 and 48% survivors (Fig. 4, B and C). Using an active caspase-8 dimer as the input to the model variant entailing caspase-8 dimerization/dissociation, the survival plots indicated a performance similar to the XIAP-extended model for the 20% threshold (Fig. 4, B and C), whereas XIAP remained more potent in attenuating signal amplification when investigating the 80% threshold of substrate cleavage (Fig. 4, B and C). Triggering with monomers of caspase-8 instead yielded by far the best survival rates (85% for 20 and 80% thresholds) when compared with all other scenarios (Fig. 4, B and C). Qualitatively comparable results were obtained when analyzing the distinct collectives for their death kinetics (supplemental Fig. 3A). We next repeated these simulations using active caspase-3 or -6 as inputs. In these collectives, the model variant including caspase-8 dimerization/dissociation again exceeded the inhibitory power of BAR or XIAP model variants (Fig. 5, A and B and supplemental Fig. 3, B and C). When comparing the results from different input stimuli (Figs. 4 and 5), the inhibitory potential of caspase-8 dimerization/dissociation was weakest when the signaling network was initiated by dimeric active caspase-8. Taken together, our data show that the dimerization/dissociation of caspase-8 generally is the most potent molecular mechanism in blocking the amplification of caspase activities via the caspase-8, -3, -6 loop.

When comparing the amount of simulation runs that resulted in intermediate substrate cleavage (between 20 and 80%), we found that XIAP was most potent in bringing about substrate cleavage at intermediary levels (Fig. 6, A–C). In contrast, the protective potential of caspase-8 dimerization/dissociation appeared to largely reside in preventing the onset of substrate cleavage because intermediary substrate cleavage was rarely detected (Fig. 6, A–C).

FIGURE 6.

Attenuation of substrate cleavage at intermediate levels. A–C, all simulations from the global sensitivity analyses presented in the previous figures were investigated for runs that resulted in intermediate levels (between 20 and 80%) of substrate cleavage after 24 h. XIAP was most potent to attenuate substrate cleavage at intermediate levels in response to all perturbations investigated. Caspase-8 (Casp-8) dimerization/dissociation only contributed to intermediate substrate cleavage when the system was initiated by dimerized caspase-8 (C8).

An Integrated Systems Model Indicates That Caspase-8 Dimerization/Dissociation Confers Strong Perturbation Resistance to the Caspase-8, -3, -6 Signaling Loop

To obtain information on the perturbation resistance of a biologically more complete scenario of caspase-8, -3, -6 signaling, we next integrated all inhibitory processes into one systems model (Fig. 7A). This model did not display any noticeable amplification of caspase activity or substrate cleavage in response to stimulation by active caspases at the mild doses used in our previous model variants and simulations (results not shown). Using this model at HeLa cell conditions, we investigated how strong the initial input stimulus can be increased before apoptosis is executed (again defined as a minimum of 80% substrate cleavage within 24 h of stimulation). We found that the caspase-8, -3, -6 loop could resist 100-fold higher inputs of active caspase-8 dimers and 6000-fold higher inputs of processed, dissociated caspase-8 monomers (Fig. 7, B and C).

FIGURE 7.

Caspase-8 dimerization/dissociation confers strong perturbation resistance to the caspase-8, -3, -6 signaling loop. A, a systems model of the caspase-8, -3, -6 loop incorporating all inhibitory processes was generated and is shown here as a pathway diagram. B and C, the systems model entailing all inhibitory processes and variants thereof in which individual inhibitors were eliminated were analyzed for how strong the input stimulus can be increased before apoptosis is executed. The input stimuli were either active caspase-8 (Casp-8) dimers (B) or processed caspase-8 monomers (C). Apoptosis execution was defined as 80% substrate cleavage by effector caspase-3, and the respective stimulus strength was marked by a black circle. HeLa cell parameters were used for modeling. k/o, knock-out.

We next individually eliminated inhibitory processes from the full model and analyzed how this affected the sensitivity to perturbations. The elimination of BAR did not confer any significant sensitization, irrespective of whether the model was initiated by active dimeric caspase-8 or processed caspase-8 monomers (Fig. 7, B and C). The elimination of XIAP fully sensitized the model to active caspase-8 dimers, whereas in response to processed caspase-8 monomers, still a 100-fold increased resistance was observed (Fig. 7C). Eliminating the requirement for caspase-8 dimerization fully abolished the perturbation resistance in both scenarios (Fig. 7, B and C). A model for type I SKW6.4 cells was generally more sensitive to perturbations but provided qualitatively similar results (not shown). Qualitatively similar results were also obtained when using active caspase-3 or -6 as the input stimuli to the models (not shown). Taken together, these results further confirm that the caspase-8 dimerization/dissociation balance plays an important role in preventing unwanted apoptosis via the caspase-8, -3, -6 loop and additionally show that a combination of XIAP and caspase-8 dimerization/dissociation can synergistically establish significantly higher resistance thresholds to strong perturbations. These threshold values should, however, be considered as qualitative because in the models, the entire stimulus is added at time 0 and therefore does not reflect a gradual input of active caspases as would be expected in living cells.

DISCUSSION

We carried out an in silico comparison of the known inhibitory mechanisms of the caspase-8, -3, -6 signaling loop. Simulating systems composed of fundamental biochemical reactions, we identified that the caspase-8 dimerization/dissociation balance can provide significant tolerance to mild caspase activation. Mechanisms preventing spontaneous amplification of caspase activities in this loop are of central physiological importance as in contrast to the mitochondrial apoptosis pathway, all essential reactants and constituents required for a lethal apoptotic feedback are present within the same cellular compartment. In a seminal systems study of the caspase-8, -3 axis, Eissing et al. (22) noted that physiological concentrations of XIAP alone were not sufficient to prevent or at least delay rapid caspase amplification in response to mild stimulation. They succeeded in fitting their model to experimental data by introducing the caspase-8 inhibitor BAR, which, together with XIAP, was subsequently also used in other systems models to suppress the caspase-8, -3, -6 loop (17, 25). Although BAR was found in a few selected cancer cells, physiological expression of BAR is restricted nearly exclusively to the central nervous system where it promotes neural apoptosis resistance (14, 26). A role for BAR as a ubiquitous inhibitor of the caspase-8, -3, -6 loop is therefore probably not substantiated. This, as well as the normal development of XIAP-deficient mice (27), suggests that an additional ubiquitous inhibitory mechanism of the caspase-8, -3, -6 loop must exist to prevent unwanted lethal caspase amplification arising from mild caspase-8 and -3 activation. Although it was initially suggested that cIAP1 and -2 might compensate for the loss in XIAP, it was subsequently shown that expression levels of these and other key proteins involved in the regulation of apoptosis did not change in the absence of XIAP and also that XIAP-deficient cells do not present increased spontaneous death rates (28–30). As dimerization/dissociation is an intrinsic feature of caspase-8 (i.e. a dedicated inhibitor is not necessary), it fulfills the requirement of being a ubiquitously present regulator. We therefore conclude that the relevance of cytosolic caspase-8 dimerization/dissociation for attenuating feedback amplification of the caspase-8, -3, -6 loop currently is underappreciated.

Although several experimental studies suggested that procaspase-8 can be efficiently activated by effector caspase-mediated proteolysis (31, 32), it was later put forward that the experimental protocols used may have resulted in artifacts arising from unwanted caspase-8 dimerization during immunoprecipitation procedures (13). In vitro characterizations suggested that the dimerization/dissociation kinetic of caspase-8 monomers might need to be considered as an important limiting factor (13) and here indeed could be shown to significantly restrict the amplification of caspase activities in the context of the type I caspase-8, -3, -6 loop. Although the cytosolic accumulation of processed caspase-8 monomers would favor the forward reaction toward the generation of active caspase-8 dimers, our analyses of the perturbation sensitivity of the signaling system (Fig. 7) showed that the caspase-8, -3, -6 loop is astonishingly resistant also to larger amounts of processed caspase-8 monomers. A study that was published in this journal while our manuscript underwent review is consistent with this finding (7). The authors generated large amounts of cleaved caspase-8 monomers in living HeLa cells and found this insufficient to induce apoptosis unless caspase-8 dimerization was facilitated artificially.

Although our calculations showed that the dimerization/dissociation balance of caspase-8 confers a strong perturbation resistance to the signaling loop, the insensitivity in a living cell might be even larger because our model omitted additional processes that interfere with the dimerization of processed caspase-8 monomers. For example, cellular FLICE-inhibitory protein (c-FLIP) long and short isoforms can dimerize with caspase-8. Although dimers of caspase-8 and c-FLIP long, when investigated within the DISC, possess catalytic activity (33, 34), dimers of caspase-8 and c-FLIP short are catalytically inactive. Quantifications of c-FLIP expression levels suggested that c-FLIP short is typically expressed in 3–5-fold higher molar amounts than c-FLIP long (35). Because the heterodimerization of c-FLIP and caspase-8 in solution is weak (36), the interference with cytosolic caspase-8 dimerization might proceed with similar dimerization/dissociation constants as reported for the interaction between caspase-8 monomers. Initial modeling based on this assumption indeed would suggest an additional 5–10-fold increase in perturbation resistance.

Our systems analysis deliberately investigated scenarios in which caspase-8 recruitment platforms such as the DISC were absent. The presence of recruitment platforms are likely to significantly influence signaling via the caspase-8, -3, -6 loop, especially in scenarios where death receptor stimulation results in initially inefficient caspase-8 activation. Caspase-6 cleaves the human procaspase-8a and -b isoforms (55 kDa, 53 kDa) after a VETD motif at positions 374 or 360, respectively. The processed caspase-8 monomers consist of the p12 subunit as well as a large p43/41 fragment comprising the p18 catalytic subunit as well as the death effector domain-containing propeptide, which is required for DISC binding. The DISC therefore can recruit processed caspase-8 monomers and enhance their dimerization and activation. It is noteworthy that further autocatalytic processing of the p43/41 fragment into the fully processed p18 subunit at the DISC is not required for apoptosis induction but can be considered a secondary event that might serve to promote the release of fully matured active caspase-8 into the cytosol (6). The DISC might catalyze caspase-8, -3, -6 signal amplification until sufficient activity has been established to initiate the mitochondrial apoptosis pathway via Bid cleavage or, in scenarios where the mitochondrial pathway is blocked, to result in apoptosis execution via the caspase-8, -3 axis. Consistent with this reasoning, it was shown that cell lines that are capable of executing apoptosis via the type I pathway present with more efficient DISC formation upon death receptor engagement (10).

Both our reduced models as well as the model integrating all inhibitory processes showed that inhibitory potential of caspase-8 dimerization/dissociation was lower when the system was triggered by dimerized caspase-8. In this case, substrate cleavage proceeded in a biphasic manner of initially low and subsequently higher cleavage rates (Fig. 2D), indicating a rapid enhancement of caspase activities that qualitatively resembles the switch-like increase in substrate cleavage, which can be detected upon extrinsically induced apoptosis proceeding via the mitochondrial pathway (17, 21). In this scenario, XIAP was an equally important inhibitor of activity amplification. This is in agreement with recent data obtained from primary mouse hepatocytes, pancreatic beta cells, and human colon cancer cells, which showed that XIAP is a key regulator of type I apoptotic signaling in response to high doses of death ligands (37, 38).

It was also reported that caspase-8 activity can arise from cardiolipin-dependent clustering of caspase-8 on the outer mitochondrial membrane (39), presenting an intriguing possibility to initiate limited caspase activation independent of pronounced DISC formation or mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization. It is, however, not known yet whether this mechanism is involved in generating sublethal caspase activities required in cellular proliferation or differentiation scenarios (11, 12). Based on our findings, it seems, however, plausible that mechanisms altering the dimerization/dissociation balance of caspase-8 can serve to regulate and titrate caspase activities in the context of the caspase-8, -3, -6 loop.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Heinrich J Huber, Christina Pop, and Guy Salvesen for helpful discussions and comments. We also thank Lorna Flanagan for critical reading of the manuscript and the reviewers for constructive advice and useful comments.

This work was supported by National Biophotonics and Imaging Platform Ireland funded under the Higher Education Authority Program for Research in Third-Level Institutions Cycle 4, co-funded by the Irish Government and the European Union – Investing in your future, as well as by grants from the Health Research Board Ireland (RP/2006/258) and the Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland Research Committee (to M. R.).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1–S4, Tables 1–8, and Datasets 1 and 2.

C. Pop and G. Salvesen, personal communication.

- DISC

- death-inducing signaling complex

- XIAP

- x-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein

- BAR

- bifunctional apoptosis regulator

- c-FLIP

- cellular FLICE-inhibitory protein.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cotter T. G. (2009) Nat. Rev. Cancer. 9, 501–507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huber H. J., Bullinger E., Rehm M. (2009) Systems approaches to the study of apoptosis, in Essentials of Apoptosis: A Guide for Basic and Clinical Research (Yin X.-M., Dong Z. eds) 2nd Ed., pp. 283–297, Humana Press, New York [Google Scholar]

- 3.Inoue S., Browne G., Melino G., Cohen G. M. (2009) Cell Death Differ. 16, 1053–1061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Logue S. E., Martin S. J. (2008) Biochem. Soc. Trans. 36, 1–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boatright K. M., Salvesen G. S. (2003) Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 15, 725–731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hughes M. A., Harper N., Butterworth M., Cain K., Cohen G. M., MacFarlane M. (2009) Mol. Cell. 35, 265–279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oberst A., Pop C., Tremblay A. G., Blais V., Denault J. B., Salvesen G. S., Green D. R. (2010) J. Biol. Chem. 285, 16632–16642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cowling V., Downward J. (2002) Cell Death Differ. 9, 1046–1056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Srinivasula S. M., Hegde R., Saleh A., Datta P., Shiozaki E., Chai J., Lee R. A., Robbins P. D., Fernandes-Alnemri T., Shi Y., Alnemri E. S. (2001) Nature 410, 112–116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scaffidi C., Fulda S., Srinivasan A., Friesen C., Li F., Tomaselli K. J., Debatin K. M., Krammer P. H., Peter M. E. (1998) EMBO J. 17, 1675–1687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maelfait J., Beyaert R. (2008) Biochem. Pharmacol. 76, 1365–1373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lamkanfi M., Festjens N., Declercq W., Vanden Berghe T., Vandenabeele P. (2007) Cell Death Differ. 14, 44–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pop C., Fitzgerald P., Green D. R., Salvesen G. S. (2007) Biochemistry 46, 4398–4407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang H., Xu Q., Krajewski S., Krajewska M., Xie Z., Fuess S., Kitada S., Pawlowski K., Godzik A., Reed J. C. (2000) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 2597–2602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deveraux Q. L., Leo E., Stennicke H. R., Welsh K., Salvesen G. S., Reed J. C. (1999) EMBO J. 18, 5242–5251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rehm M., Huber H. J., Dussmann H., Prehn J. H. (2006) EMBO J. 25, 4338–4349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Albeck J. G., Burke J. M., Aldridge B. B., Zhang M., Lauffenburger D. A., Sorger P. K. (2008) Mol. Cell 30, 11–25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rehm M., Huber H. J., Hellwig C. T., Anguissola S., Dussmann H., Prehn J. H. (2009) Cell Death Differ. 16, 613–623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Spencer S. L., Gaudet S., Albeck J. G., Burke J. M., Sorger P. K. (2009) Nature 459, 428–432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Engels I. H., Stepczynska A., Stroh C., Lauber K., Berg C., Schwenzer R., Wajant H., Jänicke R. U., Porter A. G., Belka C., Gregor M., Schulze-Osthoff K., Wesselborg S. (2000) Oncogene 19, 4563–4573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hellwig C. T., Kohler B. F., Lehtivarjo A. K., Dussmann H., Courtney M. J., Prehn J. H., Rehm M. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 21676–21685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eissing T., Conzelmann H., Gilles E. D., Allgöwer F., Bullinger E., Scheurich P. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 36892–36897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sigal A., Milo R., Cohen A., Geva-Zatorsky N., Klein Y., Liron Y., Rosenfeld N., Danon T., Perzov N., Alon U. (2006) Nature 444, 643–646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Elowitz M. B., Levine A. J., Siggia E. D., Swain P. S. (2002) Science 297, 1183–1186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bentele M., Lavrik I., Ulrich M., Stösser S., Heermann D. W., Kalthoff H., Krammer P. H., Eils R. (2004) J. Cell Biol. 166, 839–851 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roth W., Kermer P., Krajewska M., Welsh K., Davis S., Krajewski S., Reed J. C. (2003) Cell Death Differ. 10, 1178–1187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harlin H., Reffey S. B., Duckett C. S., Lindsten T., Thompson C. B. (2001) Mol. Cell. Biol. 21, 3604–3608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Conze D. B., Albert L., Ferrick D. A., Goeddel D. V., Yeh W. C., Mak T., Ashwell J. D. (2005) Mol. Cell. Biol. 25, 3348–3356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.O'Connor C. L., Anguissola S., Huber H. J., Dussmann H., Prehn J. H., Rehm M. (2008) Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1783, 1903–1913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cummins J. M., Kohli M., Rago C., Kinzler K. W., Vogelstein B., Bunz F. (2004) Cancer Res. 64, 3006–3008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Murphy B. M., Creagh E. M., Martin S. J. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 36916–36922 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sohn D., Schulze-Osthoff K., Jänicke R. U. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 5267–5273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chang D. W., Xing Z., Pan Y., Algeciras-Schimnich A., Barnhart B. C., Yaish-Ohad S., Peter M. E., Yang X. (2002) EMBO J. 21, 3704–3714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Micheau O., Thome M., Schneider P., Holler N., Tschopp J., Nicholson D. W., Briand C., Grütter M. G. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 45162–45171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kreuz S., Siegmund D., Rumpf J. J., Samel D., Leverkus M., Janssen O., Häcker G., Dittrich-Breiholz O., Kracht M., Scheurich P., Wajant H. (2004) J. Cell Biol. 166, 369–380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yu J. W., Jeffrey P. D., Shi Y. (2009) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 8169–8174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jost P. J., Grabow S., Gray D., McKenzie M. D., Nachbur U., Huang D. C., Bouillet P., Thomas H. E., Borner C., Silke J., Strasser A., Kaufmann T. (2009) Nature 460, 1035–1039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wilson T. R., McEwan M., McLaughlin K., Le Clorennec C., Allen W. L., Fennell D. A., Johnston P. G., Longley D. B. (2009) Oncogene 28, 63–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gonzalvez F., Schug Z. T., Houtkooper R. H., MacKenzie E. D., Brooks D. G., Wanders R. J., Petit P. X., Vaz F. M., Gottlieb E. (2008) J. Cell Biol. 183, 681–696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Le Novère N., Hucka M., Mi H., Moodie S., Schreiber F., Sorokin A., Demir E., Wegner K., Aladjem M. I., Wimalaratne S. M., Bergman F. T., Gauges R., Ghazal P., Kawaji H., Li L., Matsuoka Y., Villéger A., Boyd S. E., Calzone L., Courtot M., Dogrusoz U., Freeman T. C., Funahashi A., Ghosh S., Jouraku A., Kim S., Kolpakov F., Luna A., Sahle S., Schmidt E., Watterson S., Wu G., Goryanin I., Kell D. B., Sander C., Sauro H., Snoep J. L., Kohn K., Kitano H. (2009) Nat. Biotechnol. 27, 735–741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.