Abstract

The X+-linked chronic granulomatous disease (X+-CGD) variants are natural mutants characterized by defective NADPH oxidase activity but with normal Nox2 expression. According to the three-dimensional model of the cytosolic Nox2 domain, most of the X+-CGD mutations are located in/or close to the FAD/NADPH binding regions. A structure/function study of this domain was conducted in X+-CGD PLB-985 cells exactly mimicking 10 human variants: T341K, C369R, G408E, G408R, P415H, P415L, Δ507QKT509-HIWAinsert, C537R, L546P, and E568K. Diaphorase activity is defective in all these mutants. NADPH oxidase assembly is normal for P415H/P415L and T341K mutants where mutation occurs in the consensus sequences of NADPH- and FAD-binding sites, respectively. This is in accordance with their buried position in the three-dimensional model of the cytosolic Nox2 domain. FAD incorporation is abolished only in the T341K mutant explaining its absence of diaphorase activity. This demonstrates that NADPH oxidase assembly can occur without FAD incorporation. In addition, a defect of NADPH binding is a plausible explanation for the diaphorase activity inhibition in the P415H, P415L, and C537R mutants. In contrast, Cys-369, Gly-408, Leu-546, and Glu-568 are essential for NADPH oxidase complex assembly. However, according to their position in the three-dimensional model of the cytosolic domain of Nox2, only Cys-369 could be in direct contact with cytosolic factors during oxidase assembly. In addition, the defect in oxidase assembly observed in the C369R, G408E, G408R, and E568K mutants correlates with the lack of FAD incorporation. Thus, the NADPH oxidase assembly process and FAD incorporation are closely related events essential for the diaphorase activity of Nox2.

Keywords: Enzyme Mechanisms, Enzyme Mutation, Immunodeficiency, Neutrophil, Respiratory Burst, NADPH Oxidase, Nox2, Structure/Function, Chronic Granulomatous Disease, Phagocyte

Introduction

Reactive oxygen species produced by phagocytes have been regarded as major deleterious agents for pathogens since 1933 when Balbridge and Gerard (1) observed that when canine neutrophils engulf bacteria they consume large amounts of oxygen. The importance of the phagocyte NADPH oxidase is highlighted by the recurrent and life-threatening infections that occur in patients with chronic granulomatous disease (CGD),3 whose phagocytes lack superoxide producing activity (2). The catalytic core of phagocyte NADPH oxidase (Nox) is gp91phox or Nox2, a glycosylated integral membrane protein that is one of the subunits of flavocytochrome b558 (cytb), with p22phox being the second one. Heterodimer formation is needed for maturation and targeting of cytb to the plasma membrane or to the membranes of specific granules of phagocytes (3, 4). Nox2 is the first member of a large family containing seven Nox analogs to be described. It is currently known that a wide variety of eukaryotes express Noxes, with each having developed their own regulatory system according to their specific functions in tissues (5). Indeed, phagocytic NADPH oxidase is dormant in the resting condition and becomes catalytically active to produce superoxide after stimulus-dependent activation by cytosolic factors such as p67phox, p47phox, p40phox, and Rac2 translocation and assembly with cytb (6–8).

According to the hydrophobic pattern of the Nox2 sequence and immunodetection coupled to flow cytometry analysis (9), the N-terminal half of the protein appears to be embedded in the plasma membrane and is structured into six potential α-helices. This part of Nox2 contains two nonidentical hemes coordinated by four histidine residues in the III and V transmembrane passages (10). The B and D intracytosolic loops within this region are essential for oxidase assembly and electron transfer in Nox2 (11, 12). In addition, the D loop of Nox4 seems to be involved in the folding and interaction between Nox4 and p22phox (13). The C-terminal half of Nox2 seems to constitute a cytosolic region highly involved in the catalysis and regulation of NADPH oxidase activity. Indeed, sequence alignments and homology modeling of the cytosolic C terminus of Nox2 with members of the ferredoxin-NADP+-reductase (FNR) family suggest the presence of FAD and NADPH-binding sites allowing it to be termed the “dehydrogenase domain.” Two regions, 338HPFTLTSA345 and 355IRIVGD360, have been proposed as binding sites for FAD. In addition, four cytosolic sequences, namely 410GIGVTPF416, 442YWLCRD447, 504GLKQ507, and 535FLCGPE540, are considered to be binding sites for pyrophosphate, ribose, adenine, and the nicotinamide unit of NADPH, respectively (14–16). In the predicted three-dimensional structure model of Nox2, an intriguing sequence 484DESQANHFAVHHDEEKDVITG504 not present in most FNRs has been proposed to form an α-helical loop covering, in the inactive state of the enzyme, the cleft in which NADPH binds. Upon oxidase activation, NADPH access to the binding site could potentially be regulated by conformation changes in this loop consecutive to oxidase assembly (12, 17, 18).

Chronic granulomatous disease is a rare congenital immunodeficiency disorder (frequency 1/200,000) in which phagocytic cells fail to generate superoxide ( ). The existence of extremely rare X-linked cases of chronic granulomatous disease (CGD) called X+-CGD variants, characterized by the absence of NADPH oxidase activity in phagocytes but with normal expression of Nox2, pointed to sequences of Nox2 specifically involved in the activation process of this enzyme (19). Only 19 mutations out of more than 300 found in CYBB, have been reported to cause X+-CGD. Most of them are missense mutations principally located in the C-terminal cytosolic region of Nox2, confirming that this is an important functional part of the protein and less implicated in its structural stability. Some functional consequences of these rare mutations such as ex vivo/in vitro NADPH oxidase activity and translocation of cytosolic factors have been evaluated in purified human X+-CGD neutrophils from patients, confirming that electron transfer and the p47phox/p67phox binding are intimately related events (20). However, the functional impact of most of the X+-CGD mutations remained unexplored because of limitations in obtaining the human biological material. A very useful cellular model of X0-CGD neutrophils has been developed by Zhen et al. (21). The X chromosome-linked CGD locus was disrupted by homologous recombination in the PLB-985 human myeloid cell line (knock-out PLB-985 cells). This cell line was transfected with mutated Nox2 cDNA to study the role of specific domains in Nox2 (11, 12, 22). The first functional analysis of an X+-CGD case studied using this approach was a splice site mutation resulting in an in-frame deletion of 10 nucleotides encoding residues 488–497 of Nox2, located in the α-helical loop (23). These authors (23) demonstrated that this deletion impaired the electron transfer from NADPH to FAD. The functional impact of another X+-CGD missense mutation L505R was studied after purification of the mutated cytb from transgenic PLB-985 cells. It was shown that Leu-505 was probably not involved in direct binding of the adenine of NADPH (504GLKQ507) as proposed previously from the sequence alignment with FNR family members. The L505R mutation affected the oxidase complex activation process through alteration of the p67phox interaction with cytochrome b558, thus inhibiting NADPH access to its binding site (17). These knock-out PLB-985 cells were also used to study the impact of the double missense mutation, H303N/P304R, and each single mutation on oxidase activity and assembly to rule out a possible new polymorphism in the CYBB gene (24).

). The existence of extremely rare X-linked cases of chronic granulomatous disease (CGD) called X+-CGD variants, characterized by the absence of NADPH oxidase activity in phagocytes but with normal expression of Nox2, pointed to sequences of Nox2 specifically involved in the activation process of this enzyme (19). Only 19 mutations out of more than 300 found in CYBB, have been reported to cause X+-CGD. Most of them are missense mutations principally located in the C-terminal cytosolic region of Nox2, confirming that this is an important functional part of the protein and less implicated in its structural stability. Some functional consequences of these rare mutations such as ex vivo/in vitro NADPH oxidase activity and translocation of cytosolic factors have been evaluated in purified human X+-CGD neutrophils from patients, confirming that electron transfer and the p47phox/p67phox binding are intimately related events (20). However, the functional impact of most of the X+-CGD mutations remained unexplored because of limitations in obtaining the human biological material. A very useful cellular model of X0-CGD neutrophils has been developed by Zhen et al. (21). The X chromosome-linked CGD locus was disrupted by homologous recombination in the PLB-985 human myeloid cell line (knock-out PLB-985 cells). This cell line was transfected with mutated Nox2 cDNA to study the role of specific domains in Nox2 (11, 12, 22). The first functional analysis of an X+-CGD case studied using this approach was a splice site mutation resulting in an in-frame deletion of 10 nucleotides encoding residues 488–497 of Nox2, located in the α-helical loop (23). These authors (23) demonstrated that this deletion impaired the electron transfer from NADPH to FAD. The functional impact of another X+-CGD missense mutation L505R was studied after purification of the mutated cytb from transgenic PLB-985 cells. It was shown that Leu-505 was probably not involved in direct binding of the adenine of NADPH (504GLKQ507) as proposed previously from the sequence alignment with FNR family members. The L505R mutation affected the oxidase complex activation process through alteration of the p67phox interaction with cytochrome b558, thus inhibiting NADPH access to its binding site (17). These knock-out PLB-985 cells were also used to study the impact of the double missense mutation, H303N/P304R, and each single mutation on oxidase activity and assembly to rule out a possible new polymorphism in the CYBB gene (24).

The aim of this study was to provide a wider view of the functional and molecular consequences of X+-CGD mutations located in the cytosolic C-terminal tail of Nox2 after reproduction in the X-CGD PLB-985 cellular model. A partial functional impact on the oxidase activation process using human X+-CGD neutrophils was described previously for the T341K, C369R, G408E, P415H, Δ507QKT509-HIWA insertion, and E568K mutations. Other mutations (G408R, P415L, C537R, and L546P) have not previously been investigated. According to the structural model of the cytosolic C-terminal tail of Nox2, we found that most of the CYBB mutations leading to the X+-CGD phenotype were located in or close to the FAD/NADPH binding regions. We confirmed that Pro-415/Cys-537 and Thr-341 mutations affect NADPH and FAD binding, respectively. However, these amino acids were not involved in the translocation of cytosolic factors p67phox and p47phox to the plasma membrane. Cys-369, Gly-408, residues 507–509, Leu-546, and Glu-568 were essential for the assembly process of the NADPH oxidase complex during NADPH oxidase activation. In addition, the defect in NADPH oxidase complex assembly observed in C369R, G408E, G408R, and E568K mutants is related to an inhibition of FAD incorporation in Nox2. In this study, the impact of X+-CGD mutations located in the cytosolic region of Nox2 never or only partially characterized before was investigated in detail regarding all aspects of NADPH oxidase activity, complex assembly, the integrity of the active site, and catalysis of electron transfer. The data provide a molecular explanation of X+-CGD phenotypes of cytosolic Nox2 mutants.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Chemicals and Reagents

Phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA), dimethylformamide, cytochrome c (horse heart, type VI), diisopropyl fluorophosphate, horseradish peroxidase (HRP), Nα-p-tosyl-l-lysine chloromethyl ketone polystyrene latex beads (3 μm), iononitrotetrazolium (INT), luminol, Triton X-100, sodium dithionite, FAD, superoxide dismutase, and the mammalian protease inhibitors mixture P8340 were obtained from Sigma. GTPγS, NADPH, leupeptin, and pepstatin were from Roche Applied Science. Fetal bovine serum, RPMI 1640 medium, geneticin G418, Alexa Fluor 488 goat-F (ab′)2 fragment anti-rabbit IgG1 (H+L), and Alexa Fluor 546 donkey-F(ab′)2 fragment anti-goat IgG1 (H+L) were from Invitrogen. Monoclonal antibody specific for Nox2 7D5 was purchased from MBL Medical and Biological Laboratories (Naka-ku Nagoya, Japan). Monoclonal antibodies 54.1 and 44.1 were kindly provided by Prof. A. Jesaitis (Montana State University). Polyclonal antibodies anti-p47phox and p67phox were purchased from Upstate Biotechnologies, Inc., and Tebu-Bio (Le Perray en Yvelines, France), respectively. Endo-free plasmid maxi kit and QIAprep spin miniprep kit were purchased from Qiagen. The Sephaglas kit and molecular weight markers (Page Ruler®) were obtained from Amersham Biosciences and Fermentas (Burlington, Canada), respectively. Nitrocellulose sheets for Western blotting were purchased from Bio-Rad.

In Vitro Mutagenesis and Expression of Recombinant Nox2 in Promyelocytic PLB-985 Cells

Mutations were introduced into the wild type Nox2 cDNA in pBlueScript II KS(+) vector using the QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. The mutated sequence of Nox2 cDNA was verified by sequencing (Cogenics, Grenoble, France). The WT or mutant Nox2 cDNA was subcloned into the BamHI site of the mammalian expression vector pEF-pGKNeo as described previously (12). The constructs were transfected into the X-CGD PLB 985 cell line (a generous gift of Prof. M. Dinauer, Indiana University) by electroporation at 250 V (1 pulse of 20 ms). X-CGD PLB-985 cells correspond to CYBB knock-out PLB-985 cells as described by Dinauer and co-workers (21). Clones were selected by limited dilution in the presence of 1.5 mg/ml geneticin.

Cell Culture and Granulocyte Differentiation

WT, X-CGD PLB-985 cells, and transfected X-CGD PLB-985 cells were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% (v/v) heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum, 100 units/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, 2 mm l-glutamine at 37 °C in a 5% CO2-humidified atmosphere. After selection of transfected X-CGD PLB-985 cells, 0.5 mg/ml geneticin was added to maintain the selection pressure. To induce granulocyte differentiation and expression of endogenous NADPH oxidase components, PLB-985 cells (2 × 105 cells/ml) were differentiated for 6 days with 0.5% (v/v) dimethylformamide.

Analysis of Recombinant Nox2 Expression in PLB-985 Cell Lines

Nox2 expression was analyzed by flow cytometry, immunoblot, and differential spectrophotometry in PLB-985 cell lines as described previously (12). 5 × 105 PLB-985 cells were incubated with 5 μg/ml monoclonal antibody 7D5 directed against Nox2 or with monoclonal irrelevant IgG1 (Clinisciences, Montrouge, France). Then the cells were incubated with phycoerythrin-labeled goat-F(ab′)2 fragment anti-mouse Ig (Molecular Probes, Cergy Pontoise, France). Flow analysis (FACS) was performed with FACSCalibur (BD Biosciences). In some experiments, 7D5-positive PLB 985 cells (1·107) were sorted with FACSVantage Diva (BD Biosciences) instrument at sheath pressure of 12 p.s.i. with a 70 μm nozzle. Sorted cells were collected into phosphate-buffered saline supplemented with 1% BSA (w/v). The purity rate of the sorted population is generally higher than 97%. The Nox2 expression was also examined by immunodetection using monoclonal antibodies 54.1 and 44.1 directed against Nox2 and p22phox, respectively (25). Cytochrome b558 differential analysis was performed with DU 640 Beckman spectrophotometer. For determination of cytochrome b558 concentration, a molecular extinction coefficient at λ426 nm, 106 mm−1·cm−1 was used.

Measurement of  Production by Chemiluminescence

Production by Chemiluminescence

production of intact differentiated PLB-985 cells (5 × 105 cells) in PBS containing CaCl2 and MgCl2, 20 mm glucose, 20 μm luminol, and 10 units/ml HRPO were measured after PMA stimulation (77 ng/ml). Relative light units were recorded at 37 °C over a time course of 60 min in a luminometer (Labsystems, Helsinki, Finland) connected to a computer. Results were expressed as the sum of relative luminescence detected during the kinetics of ROS production (12).

production of intact differentiated PLB-985 cells (5 × 105 cells) in PBS containing CaCl2 and MgCl2, 20 mm glucose, 20 μm luminol, and 10 units/ml HRPO were measured after PMA stimulation (77 ng/ml). Relative light units were recorded at 37 °C over a time course of 60 min in a luminometer (Labsystems, Helsinki, Finland) connected to a computer. Results were expressed as the sum of relative luminescence detected during the kinetics of ROS production (12).

Detection of Ex Vivo p47phox and p67phox Translocation in Transfected PLB-985 Cells

Differentiated 5·105 PLB-985 cells were deposited on glass slides and activated with 10 μl of PMA-treated latex beads (100 μl of 40 μg/ml PMA were mixed with latex beads (3 μm) in 100 μl of sterile PBS) for 15 min at 37 °C. Cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min and permeabilized by 0.25% Triton X-100. The polyclonal anti-rabbit p47phox raised against residues 371–390 in the C-terminal region, as described in Ref. 26, and goat polyclonal antibodies against p67phox C-19 from Santa Cruz Biotechnology were used as primary stain. Alexa Fluor 488 F(ab′)2 fragments of goat anti-rabbit IgG (H+L) and Alexa Fluor 546 F(ab′)2 fragments of donkey anti-goat IgG (H+L) were used as second antibodies (Molecular Probes). Cellular nuclei were visualized by Hoechst 33258 staining. Cells were examined with a confocal laser scanning microscope and analyzed by Leica confocal software (12). 107 X0-CGD and WT-Nox2 or some mutated Nox2-transfected PLB-985 cells were also activated with PMA (80 ng/ml) or without PMA for 10 min at 37 °C and then resuspended and sonicated in ice-cold oxidase buffer containing sucrose 15% (w/v) as described previously (34). Plasma membranes were separated on a discontinuous sucrose gradient (52% (w/v), 40% (w/v)), and the presence of cytosolic factors in the harvested plasma membranes (interface of the 15/40% sucrose layers) was visualized by Western blotting using the same antibodies as described above.

Preparation of Membranes and Cytosol Fractions

After treatment with 3 mm diisopropyl fluorophosphate in ice for 15 min, differentiated PLB-985 cells or purified human neutrophils, isolated as described previously (27), were resuspended at a concentration of 5·108 cells/ml in PBS containing 1.5 μm pepstatin, 2 μm leupeptin, and 12 μm Nα-p-tosyl-l-lysine chloromethyl ketone. Cells were disrupted by sonication (three times for 10 s, 40 watts), and the homogenate was centrifuged at 1000 × g for 15 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was centrifuged at 200,000 × g for 1 h at 4 °C. The high speed supernatant was referred to as the cytosol, and the pellet consisting of crude membranes was resuspended in the same buffer at a protein concentration of 3–5 mg/ml. Protein content was estimated using the Bradford assay (28).

Detection of NADPH Oxidase and Diaphorase Activities in a Cell-free System Assay

In vitro NADPH oxidase activity was measured using plasma membranes (100 μg) obtained from differentiated transfected PLB-985 cells and cytosol (300 μg) from human neutrophils in a reaction mixture containing 20 μm GTPγS, 5 mm MgCl2, and an optimal amount of arachidonic acid in a final volume of 100 μl. Oxidase activity was measured in the presence of 100 μm cytochrome c and 150 μm NADPH. The specificity of the  production was checked by adding 50 μg/ml superoxide dismutase (27). INT reductase (or diaphorase) activity was performed in the same conditions, except that cytochrome c was replaced with 100 μm INT (29).

production was checked by adding 50 μg/ml superoxide dismutase (27). INT reductase (or diaphorase) activity was performed in the same conditions, except that cytochrome c was replaced with 100 μm INT (29).

Detection of FAD Incorporation into Cytochrome b558

Membrane FAD content was determined from 5·108 PLB-985 transfected cells activated or not by PMA (80 ng/ml). Assays were performed from the resulting plasma membranes (0.7–1 mg) incubated at 100 °C for 15 min. After centrifugation at 20,000 × g for 15 min, supernatants were saved for measurements of noncovalently bound flavin by the fluorometric method (30). The emission of FAD was measured at 535 nm after excitation at 450 nm using a Varioskan (Thermo Scientific) fluorescence spectrophotometer against a FAD standard scale (50–1000 pmol/well). Results were expressed in pmol of FAD/mg of protein. The FAD content of plasma membranes from X0-CGD PLB-985 cells was deduced from the values measured in each transgenic PLB-985 cell line.

Statistics

Statistical analysis was performed with StatView Software using the Mann-Whitney test.

RESULTS

Localization and Conservation of Amino Acids of Nox2 Involved in X+-CGD among Noxes and Ferredoxin-NADP+ Reductase Family Members

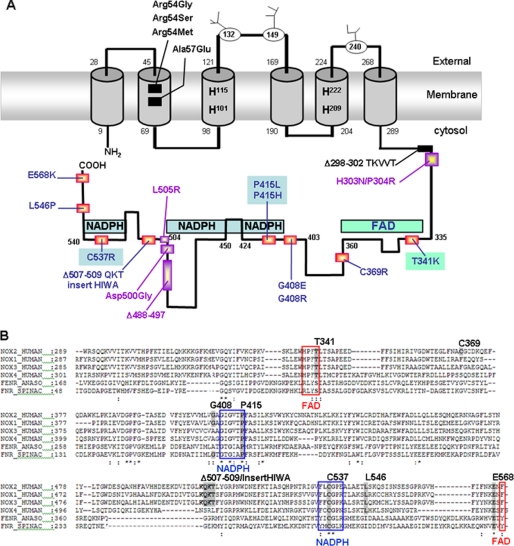

Nineteen mutations have been reported to cause X+-CGD. Fifteen are missense (or small deletions/insertions) mutations principally located in the C-terminal cytosolic region of Nox2, confirming that this domain has a central role in NADPH oxidase complex assembly and catalysis (Fig. 1A). Four of them (H303N/P304R, Δ488–497, D500G, and L505R) were reproduced previously in the X-CGD PLB-985 cell line to study their impact on NADPH oxidase complex functioning (12, 18, 23, 24). We studied the functional impact of 10 mutations (T341K, C369R, G408E, G408R, P415H, P415L, Δ507–509-InsertHIWA, C537R, L546P, and E568K) located in the cytosolic tail of Nox2 in the X-CGD PLB-985 cell line model to highlight amino acids and regions important for the NADPH oxidase activation process. However, we were not able to express Δ298–302 mutated Nox2 in the X-CGD PLB-985 cell line (data not shown).

FIGURE 1.

Location and conservation of Nox2 amino acids involved in X+-CGD among Noxes and ferredoxin-NADP+ reductase family members. A, glycosylated asparagines are located in the external loops of Nox2 and numbered by their residue numbers. The four heme-binding histidines located in the third and fifth transmembrane domains are shown by single-letter code as H. The potential FAD and NADPH binding domains are illustrated by filled boxes. Mutations causing X+-CGD forms of CGD are preferentially located in the C-terminal cytosolic part of Nox2. Mutations written in black were not studied here. X+-CGD mutations in purple have been previously studied for their functional impact in transgenic PLB-985 cells. X+-CGD mutations studied here are in blue. Mutations in blue and green filled boxes are located in the potential NADPH- and FAD-binding sites, respectively. B, amino acids involved in X+-CGD and conserved in Nox1, Nox3, and Nox4 homologs and in FNRs are boxed in gray. The red boxes represent the potential FAD-binding sites, and the blue boxes represent the NADPH-binding sites of Noxes highly conserved in FNRs. FENR_ANASO means ferredoxin-NADP+ reductase from Anabaena sp., and FRN_SPINAC means ferredoxin-NADP+ reductase from S. oleacera.

One striking observation is that most of the residues (5/7) concerned with the missense mutations, apart from Cys-369, which is not conserved in the Nox family members, Thr-341, Pro-415, Cys-537, Leu-546, and Glu-568 are strictly conserved in Nox1, Nox3, and Nox4, which present 56, 58, and 39% homology, respectively, with Nox2 (Fig. 1B). Yet Gly-408 is conserved in Nox1 and replaced by an Ala in Nox3 and Nox4. Nevertheless, both residues are noncharged residues differing by a methyl substitution only. Pro-415, Pro-537, and Glu-568 are totally conserved in the ferredoxin-NADP+ reductases (FNR) of Spinacia oleacera (31), which also served as template for the three-dimensional model of the dehydrogenase domain of Nox2 (18) and in the FNR from Anabaena sp. (highly homologous to FNR of S. oleacera) (32). In addition, Thr-341 is replaced by a Ser in the RXYS sequence in the two FNRs, which is the FAD binding domain homologous to HPFT in the Nox family members (4). The amino acids of the Δ507–509 are similar in Nox1, Nox2, and Nox3 but different in Nox4 and not found in FNRs. The high conservation of most of the studied residues in the Nox family members and high homologies found in the FNRs suggest that they could play a common role in the NADPH oxidase activation and/or activity.

Production of 10 Transfected PLB-985 Cells Mimicking the Human X+-CGD Neutrophils

The WT and mutated Nox2 cDNA subcloned into the pEF-PGKneo vector were checked by sequence analysis and purified before transfection in X-CGD PLB-985 cells, as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Nox2 expression was studied by flow cytometry (FACS) using the monoclonal antibody 7D5, and IgG1 was used as negative control to test the specificity of Nox2 binding (Fig. 2). For two mutants (G408E and G408R), FACS was also used to sort a high Nox2-expressing population. We tested 20–25 different clones for each mutant, and to minimize clone-to-clone variation in NADPH oxidase activity, two to three independent clones of each highly expressing Nox2 mutant were used for subsequent analysis (data not shown). As expected, Nox2 was not detected in X-CGD PLB-985 cells or in empty vector transfected PLB-985 cells. WT and mutated Nox2 and p22phox expression in transfected PLB-985 cells was analyzed semi-quantitatively by Western blot analysis (Fig. 3A). Finally, heme incorporation in recombinant WT and mutated Nox2 proteins was verified by differential spectrophotometry. Identical differential spectrum characteristics of flavocytochrome b558 were observed in all mutants compared with WT Nox2-transfected PLB cells or WT PLB-985 cells (Fig. 3B). In addition the amount of cytochrome b558 measured in all the transfected X-CGD PLB-985 cells was in the same range as that found in WT PLB-985 cells, confirming results previously obtained by FACS and Western blot analysis. No differential spectra were detected in X-CGD PLB-985 cells or empty vector transfected cells. Indeed, none of the mutated residues were involved in the incorporation/stabilization of the hemes, heterodimerization with p22phox, and Nox2 maturation up to the plasma membrane.

FIGURE 2.

Expression of WT and mutated Nox2 in transfected X-CGD PLB-985 cells. 5 × 105 differentiated transfected X-CGD PLB-985 cells were incubated with the Nox2 monoclonal antibody 7D5, combined with a phycoerythrin-conjugated anti-mouse IgG (H+L), as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Mouse IgG1 isotype was used as an irrelevant monoclonal antibody. For G408E and G408R mutated Nox2 PLB-985 cells, 7D5 positive clones were sorted by FACS. − and + represent Nox2 expression before and after sorting, respectively. Three positive clones were selected for each mutation and conserved in nitrogen.

FIGURE 3.

Cytochrome b558 quantification in transfected X-CGD PLB-985 cells. A, immunodetection of both subunits of cytochrome b558, Nox2 and p22phox, was performed in 1% Triton X-100 soluble extract from PLB-985 transgenic cells, submitted to SDS-PAGE, blotted onto a nitrocellulose sheet, and revealed with monoclonal antibodies 54.1 and 44.1 against Nox2 and p22phox respectively. Results shown are from one experiment representative of three. B, differential spectra analysis of cytochrome b558 in 1% Triton X-100 soluble extract from transfected PLB-985 cells. Reduction was achieved by adding a few grains of sodium dithionite to the sample, and the reduced-minus-oxidized difference spectra were recorded at room temperature with a DU 640 Beckman spectrophotometer. The amounts of cytochrome b558 expressed in nanomoles of cytb/mg protein represent the mean ± S.D. of three separate experiments.

Ex vivo NADPH oxidase activity of transfected PLB-985 cells was measured by chemiluminescence in the presence of luminol and HRP as described under “Experimental Procedures.” No  production was detected in intact PLB-985 cells of any of the tested mutants. In addition, no in vitro NADPH oxidase activity in a cell-free system assay could be reconstituted with subcellular fractions from any mutants (Table 1). At this stage, we can conclude that the phenotype of X+-CGD neutrophils was perfectly reproduced in the transfected PLB-985 cells for all the mutations studied, i.e. normal mutated Nox2 expression with no NADPH oxidase activity.

production was detected in intact PLB-985 cells of any of the tested mutants. In addition, no in vitro NADPH oxidase activity in a cell-free system assay could be reconstituted with subcellular fractions from any mutants (Table 1). At this stage, we can conclude that the phenotype of X+-CGD neutrophils was perfectly reproduced in the transfected PLB-985 cells for all the mutations studied, i.e. normal mutated Nox2 expression with no NADPH oxidase activity.

TABLE 1.

NADPH oxidase and INT reductase activities in transfected X-CGD PLB-985 cells

production was measured by luminol-amplified chemiluminescence in 5·105 differentiated and transfected X-CGD PLB-985 cells after PMA stimulation. Results are represented as total activity by the sum of relative luminescence units measured in 60 min. In vitro NADPH oxidase was reconstituted in a cell-free system with purified plasma membranes from transfected X-CGD PLB-985 cells in the presence of human neutrophil cytosol and activated with GTPγS and arachidonic acid as described under “Experimental Procedures.” INT reductase activity was determined in the same conditions as described above, except that cytochrome c was replaced by INT. Activities were also expressed as percentage of activity compared with the WT-Nox2 PLB-985 cell line. The data represent average ± S.D. of at least three independent experiments (n = 3–6).

production was measured by luminol-amplified chemiluminescence in 5·105 differentiated and transfected X-CGD PLB-985 cells after PMA stimulation. Results are represented as total activity by the sum of relative luminescence units measured in 60 min. In vitro NADPH oxidase was reconstituted in a cell-free system with purified plasma membranes from transfected X-CGD PLB-985 cells in the presence of human neutrophil cytosol and activated with GTPγS and arachidonic acid as described under “Experimental Procedures.” INT reductase activity was determined in the same conditions as described above, except that cytochrome c was replaced by INT. Activities were also expressed as percentage of activity compared with the WT-Nox2 PLB-985 cell line. The data represent average ± S.D. of at least three independent experiments (n = 3–6).

|

Ex vivo NADPH oxidase activity (n = 3–5) |

In vitro NADPH oxidase activity |

In vitro INT reductase activity |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transgenic PLB-985 cells |

production (RLU) production (RLU) |

% |

production (nmol/min/mg protein) production (nmol/min/mg protein) |

% | Electrons production (nmol/min/mg protein) | % |

| Controls | ||||||

| WT - Nox2 cells | 350.00 ± 6.50 | 100 | 100.88 ± 11.10 | 100 | 90.33 ± 9.29 | 100 |

| PLB985 CGDX0 | 0.11 ± 0.02 | 0 | 1.78 ± 3.20 | 0 | 7.81 ± 4.16 | 0 |

| T341K | 0.08 ± 0.04 | 0 | 1.23 ± 3.06 | 0 | 5.83 ± 1.04 | 0 |

| FAD/NADPH | ||||||

| P415H | 0.51 ± 0.10 | 0 | 1.08 ± 3.70 | 0 | 5.67 ± 2.31 | 0 |

| P415L | 0.10 ± 0.01 | 0 | 1.15 ± 2.12 | 0 | 5.50 ± 0.71 | 0 |

| C537R | 0.34 ± 0.05 | 0 | 1.60 ± 1.73 | 0 | 9.00 ± 1.73 | 1 |

| C369R | 1.07 ± 0.40 | 0 | 1.45 ± 0.71 | 0 | 2.83 ± 1.61 | 0 |

| G408E | 0.08 ± 0.02 | 0 | 1.73 ± 3.06 | 0 | 5.00 ± 0.19 | 0 |

| Close to the FAD/NADPH-binding site | ||||||

| G408R | 0.07 ± 0.02 | 0 | 1.33 ± 2.08 | 0 | 6.33 ± 2.08 | 0 |

| Δ507–509 | 0.22 ± 0.09 | 0 | 1.37 ± 3.06 | 0 | 12.00 ± 1.00 | 5 |

| L546P | 0.40 ± 0.05 | 0 | 1.20 ± 1.73 | 0 | 6.33 ± 2.89 | 0 |

| E568K | 0.73 ± 0.31 | 0 | 1.96 ± 2.52 | 0 | 4.50 ± 2.95 | 0 |

In Vitro INT Activity of Transfected X-CGD PLB-985 Cells Mimicking X+-CGD Neutrophils

To determine whether the inhibition of oxidase activity and/or the defect of complex assembly in mutant PLB-985 cells was associated with the electron transfer process from NADPH to FAD, we measured the INT reductase activity in purified plasma membranes from all the mutant X+-CGD PLB-985 cells (Table 1). This activity was abolished in all the mutants of the cytosolic tail of Nox2 showing that the X+-CGD mutations studied disturbed the normal electron transfer from NADPH to FAD either directly by interfering within the FAD/NADPH-binding site or indirectly by preventing preliminary complex assembly.

Impact of the 10 X+-CGD Mutations on the p47phox/p67phox Translocation to the Plasma Membrane upon NADPH Oxidase Activation in Transgenic PLB-985 Cells

To elucidate the reason why the electron transfer from NADPH to FAD was abolished in X+-CGD PLB-985 cells, assembly of the oxidase complex was studied after particulate stimulation. Translocation of p47phox and p67phox was followed by confocal microscopy in intact differentiated PLB-985 cells after latex bead phagocytosis (Fig. 4). NADPH oxidase activity was systematically controlled in the activated cells by chemiluminescence assay (data not shown). This translocation method is highly reproducible, and the experiments were conducted at least four to six times for each mutant. The deformation of the Hoechst 33258-labeled nuclei allowed us to ascertain that the latex beads were indeed in the cell. As seen in Fig. 4A, the phagocytosis of latex beads occurred in WT-Nox2 PLB985 cells as in empty vector-transfected X-CGD PLB-985 cells (X-CGD) independently of oxidase activity. As expected, p47phox and p67phox were present in the cytosol from all the tested transfected PLB-985 cells. No fluorescence was observed in WT PLB-985 cells when primary antibodies were omitted (data not shown). A green and a red fluorescence representing p47phox and p67phox, respectively, surrounded the phagosome membranes around the latex beads in intact WT-Nox2 PLB-985 cells. A yellow merged image indicated the co-localization of p47phox and p67phox in phagosome membranes. However, no translocation of both cytosolic proteins occurs in X-CGD PLB-985 cells in which Nox2 expression is absent (Fig. 4A). These preliminary data are control experiments that ascertain the results obtained with the mutant PLB-985 cells. Four mutations of three residues (P415H, P415L, C537R, and T341K) did not affect the assembly of the NADPH oxidase complex (Fig. 4B), whereas five mutations (C369R, G408E, G408R, L546P, and E568K) strongly inhibited the translocation of p47phox and p67phox to the phagosomal membranes of the mutants (Fig. 4C). For the latter mutants, no accumulation of green and red fluorescence was visible around the phagocytosed latex beads as shown in the WT-Nox2 PLB-985 cells or in mutants with no defect of the assembly process (Fig. 4, A and B). The Δ507–509-HIWA insertion mutation of Nox2 partially affects the translocation of cytosolic factors to the phagosomal membrane during phagocytosis and oxidase activation (Fig. 4C). The same results for some mutants and controls were obtained with the classical translocation method consisting of analyzing the presence of cytosolic factors with Western blotting after purification of PMA-activated membranes of transfected PLB-985 cells from a discontinuous sucrose gradient (Fig. 4D), as described previously (34).

FIGURE 4.

NADPH oxidase assembly in transfected PLB-985 cells stimulated by latex beads. A, control of translocation experiments in Nox2-transfected PLB-985 cells and X-CGD PLB-985 cells. Positive control of p47phox and p67phox translocation corresponds to WT-Nox2 cells, whereas PLB-985 CGD X0 cells were used as a negative control of p47phox and p67phox translocation. B, cytosolic mutants located in the active pocket site (FAD/NADPH-binding site); C, mutants located in regions closed to the FAD/NADPH-binding site. p47phox and p67phox translocation to the plasma and phagosomal membranes were evaluated by confocal microscopy analysis in WT and mutated Nox2 transfected PLB-985 cells stimulated by PMA-treated latex beads as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The same observations were obtained in four to six independent experiments done for each transfected-PLB-985 cells. D, 107 X0-CGD and WT-Nox2 or mutated Nox2 transfected PLB-985 cells were activated with PMA (80 ng/ml) or without PMA and sonicated in ice-cold oxidase buffer as described previously (34). Plasma membranes were separated on a discontinuous sucrose gradient, and the presence of cytosolic factors was visualized by Western blotting as described under “Experimental Procedures.” − and + represent negative or positive cytosolic factors translocation to the plasma membranes, and +/– represents a diminished (or not optimal) cytosolic factors translocation. This is representative of one experiment of two.

Impact of X+-CGD Mutations on FAD Incorporation in Nox2

To determine the impact of the X+-CGD mutations on FAD accumulation in mutated Nox2 proteins, which could also explain the absence of diaphorase activity in the mutants, plasma membranes were purified from unstimulated or PMA-stimulated transfected PLB-985 cells to measure the FAD incorporation as described under “Experimental Procedures.” No FAD incorporation in resting or stimulated plasma membranes from the T341K mutant was measured, although cytosolic factor translocation occurred normally. Nevertheless, the FAD incorporation was normal in the P415H and C537R mutants, and the NADPH oxidase assembly was correct (Table 2 and Fig. 5B). We concluded that the inhibition of NADPH oxidase and diaphorase activities in the P415H and C537R mutants was probably caused by a defect of NADPH binding, but for the T341K mutant, these defects were due to the absence of FAD incorporation during the activation process. Surprisingly, C369R, G408E, and E568K mutants, which demonstrated an absence of NADPH oxidase assembly during the phagocytosis of particulate stimuli (Fig. 5C), showed a defect of FAD incorporation in the mutated purified plasma membranes. Increases of FAD incorporation in the purified plasma membranes from PMA-activated transfected PLB-985 cells were obtained for WT-Nox2 PLB-985 cells and to a lesser extent for the C537R mutant cells. This suggests that the increase of FAD incorporation is related to the NADPH oxidase activation process (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

FAD incorporation into plasma membranes from transfected PLB-985 cells

FAD content of purified resting or PMA-activated plasma membranes was measured by the fluorometric method as described under “Experimental Procedures” and expressed in picomoles of FAD/mg of proteins. The FAD content of plasma membranes from X0-CGD PLB-985 cells was deduced from the values measured in each transgenic PLB-985 cell. The data represent the mean ± S.D. of at least three independent experiments. ND means not determined. The difference between resting and PMA activated membranes is significant.

| Transgenic PLB-985 cells, n = 3–5 | Resting membranes | PMA-activated membranes |

|---|---|---|

| pmol of FAD/mg of protein | ||

| Controls | ||

| WT-Nox2 | 36.6 ± 5.8 | 61.3 ± 4.1a |

| PLB-985 CGD X0 | / | / |

| FAD/NADPH | ||

| T341K | 0.0 ± 4.6 | 0.0 ± 2.2 |

| P415H | 35.9 ± 2.8 | ND |

| C537R | 42.9 ± 2,0 | 55.8 ± 5.5b |

| Close to the FAD/NADPH-binding site | ||

| C369R | 0.0 ± 1.7 | 0.0 ± 1.6 |

| G408E | 0.0 ± 2.8 | ND |

| E568K | 0.0 ± 2.1 | 1.7 ± 1.1 |

a p = 0.01 using Mann-Whitney test.

b p < 0.5 using Mann-Whitney test.

FIGURE 5.

X+CGD mutation locations within the cytosolic C-terminal domain of Nox2. Surface and schematic representation of the three-dimensional model of the cytosolic C-terminal domain of Nox2. FAD and NADPH are represented as sticks using the CPK color code (carbons are in yellow and cyan for FAD and NADPH, respectively). A, side chain of residue mutated in X+-CGD are represented as sticks and are colored orange. B, expanded view on the active site pocket. P415H and C537R mutation are modeled. Side chains are represented as sticks and also as surfaces for mutated ones. C, expanded view on top of the active site pocket, at the theoretical interface with the membranous part of Nox2. C-terminal Phe-570 is represented as sticks and is colored green. D, zoom on the NADPH pyrophosphate interacting loop (408–412), highlighted in red, containing the X+CGD mutated residue Gly-408. E, expanded view on the 358–370 β-sheet involved in the binding of the FAD adenosine moiety. X+CGD mutation C369R is modeled as sticks (respectively colored in orange and white for original cysteine and arginine mutations). Figures were drawn using PyMol software.

DISCUSSION

Taking advantage of previously identified key residues within the Nox2 C-terminal region and in the context of X+-CGD patients, our aim was to fully characterize on a structural and functional basis the molecular consequences associated with these mutations. Ten of the 15 X+-CGD mutations located in the C-terminal domain of Nox2 were successfully reproduced in the X-CGD PLB-985 cell model and were characterized by totally abolished oxidase activity despite a normal expression level. The functional impact of each mutation is summed up in Table 3. To better understand and to discuss these results, the mutations were visualized in the three-dimensional model of the cytosolic C terminus of Nox2 proposed by Taylor et al. (18). This model of the dehydrogenase domain of Nox2 was produced by homology modeling of FNRs and represents half of the Nox2 molecule. With due caution, this model (the only one accessible to us at the time of the study) allows us to propose a molecular interpretation of X+-CGD mutations in agreement with known experimental data. A striking observation is that all these mutated amino acids, involved in the X+-CGD phenotype, surround the NADPH/FAD-binding site of Nox2 (Fig. 5A).

TABLE 3.

Summary of the functional consequences of the X+-CGD mutations in phagocytes

| Mutations in Nox2 | NADPH oxidase activity | In vitro INT reductase activity | p47phox/p67phox translocation | FAD binding |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T341K | Abolished | Abolished | Normal | Abolished |

| P415H | Abolished | Abolished | Normal | Normal |

| P415L | Abolished | Abolished | Normal | ND |

| C537R | Abolished | 1% of normal | Normala | Normal |

| C369R | Abolished | Abolished | Abolisheda | Abolished |

| G408E | Abolished | Abolished | Abolished | Abolished |

| G408R | Abolished | Abolished | Abolished | ND |

| Δ507–509 | Abolished | 5% of normal | Diminisheda | ND |

| L546P | Abolished | Abolished | Abolished | ND |

| E568K | Abolished | Abolished | Abolished | Abolished |

a Results of cytosolic factors translocation were obtained after NADPH oxidase activation with both soluble and particulate stimuli as described under “Experimental Procedures.”

Mutated Amino Acids in the Active Site Pocket

Thr-341 is strictly conserved in Nox homologs and belongs to the 338HPFT341 motif that is a good candidate for FAD binding (18). In FNR members, this motif is replaced by the RXYS motif where the equivalent serine residue interacts with the N5 atom of the flavin ring (Fig. 1B). The N5 atom in the isoalloxazine ring of flavin is the site of electron entry upon hydride transfer from NADPH. This serine residue is essential to modulate reactivity of the flavin ring. Indeed, its replacement by an alanine in several FNR members leads to enzymes with only 0.05 and 0.07% catalytic efficiency remaining for spinach FNR and E. coli flavin reductase, respectively (4, 35). In addition, mutation of the cytochrome b5 reductase, which possesses a threonine at this position, leads to comparable effects (36). All of these studies have shown that mutation of this Ser/Thr residue destabilizes the transient state required for hydride transfer to occur between the FAD and the nicotinamide ring (4, 37, 38) Similarly, Thr-341 of Nox is proposed to be an essential amino acid for efficient electron transfer to FAD. In the case of the T341K mutation, a bulky lysine residue replaces this threonine. Indeed, apart from simply altering catalytic activity, its close proximity to the isoalloxazine ring in the active site (Fig. 5B) can prevent FAD binding in purified resting or PMA-activated plasma membranes. This defect also explains the absence of diaphorase activity. In addition, this mutation does not affect the translocation of cytosolic factors during the NADPH oxidase activation process, as might be expected from its location within the active site and data described previously (20). This permits us to conclude, for the first time, that translocation of cytosolic factors can occur in the absence of FAD in its binding site.

According to the alignment with FNR family members, Pro-415 and Cys-537 are located, respectively, in the 410GIGVTP415 and 535FLCGPE540 sequences that have been proposed to be part of the active site pocket. Pro-415 and Cys-537, like Thr-341, are highly conserved residues both in the Nox family members and in FNRs (Fig. 1B). According to our data, the absence of NADPH oxidase activity in the P415H, P415L, and C537R mutant PLB-985 cells is explained by the absence of diaphorase activity, although complex assembly and FAD binding were normal. For these mutants, we tested increasing amounts of NADPH, up to 3 mm, in the reconstituted NADPH oxidase activity assay without success (data not shown). The model of the dehydrogenase domain suggests that mutations of Cys-537 and Pro-415 to Arg and (His/Leu), respectively, induce steric clashes in the active site where the charge transfer between isoalloxazine and nicotinamide rings has to take place (Fig. 5B). This is in full agreement with previous observations on FNR proteins. Modification of the FNR corresponding cysteine to a serine decreases the kcat by a factor of 32 without affecting the binding of NADPH (33). Indeed, the correct positioning of the nicotinamide ring, with respect to the flavin isoalloxazine ring, required for efficient hydride transfer, is perturbed in this mutant. On this basis, the functional consequences of the more drastic C537R mutation in Nox2, which have never been studied before, can readily be extrapolated. Because of the size of the arginine side chain, with respect to cysteine, it probably prevents entrance or correct positioning of the nicotinamide ring in the active site as suggested by simulation of this mutation in the FNR-based model of the Nox2 dehydrogenase domain (Fig. 5B). Similarly, it suggests that the side chain size of histidine at position 415 induces steric clashes in the active site notably with the essential Thr-341 preventing access to the nicotinamide ring (Fig. 5B). This interpretation is supported by a previously reported photoaffinity experiment where the P415H mutation prevented 2-azido-NADP+ binding and labeling (14). On the other hand, the affected amino acids themselves, Pro-415 and Cys-537, are located at some distance from FAD, which explains why their mutations are compatible with normal FAD binding. These two amino acids are buried far from the protein surface within the active site, thus allowing normal translocation of cytosolic factors even when mutated. In conclusion, P415H or C537R mutations lead to steric conflicts probably incompatible with the correct orientation of NADPH with respect to FAD within the active site.

Mutated Amino Acids Close to the FAD/NADPH-binding Site

Cys-369, Gly-408, Leu-546, and Glu-568 are located close to the FAD/NADPH-binding sites. According to our data, C369R, G408E, G408R, L546P, and E568K have common and global functional effects; they inhibit NADPH oxidase, diaphorase activities, and p47phox and p67phox translocation to the phagosomal membranes. In addition, FAD incorporation is abolished in all these mutated Nox2 (except for L546P, data not determined). In line with the dehydrogenase structural model analysis and because of the absence of FAD binding to the mutated Nox2 protein, these mutations seem to disturb the integrity of the FAD/NADPH-binding site.

The Glu-568 residue is totally conserved both in Nox family members and in FNRs (Fig. 1B). Glu-568 is buried and located only two amino acids before the C-terminal Phe-570 (Fig. 5C), a crucial residue in the whole FNR family. In the absence of NADPH in the active site, the isoalloxazine ring is stacked and stabilized against two aromatic residues, one of them being Phe-570. In the reaction mechanism of these enzymes, the entry of NADPH displaces the C-terminal tyrosine and replaces it with its nicotinamide ring, thus allowing electron transfer to occur. In the FNR of peas, mutation of this residue has a dramatic effect on the stability and thus on the enzyme activity (39). The molecular explanation for the effect of CGD mutation E568K is not obvious from the analysis of Taylor's structural model. Replacement of this acidic residue by a basic one may disrupt the structural organization of the C terminus and notably the correct positioning of the Phe-570 ring (Fig. 5C). This may account for the loss of FAD binding in this mutant through an indirect effect on FAD stabilization in the active site, thus explaining the absence of activity. Finally, the impairment of complex assembly in this mutant is more difficult to explain. Because Glu-568 is at the interface between the cytosolic and membrane domains of Nox2, substitution by a basic residue may alter the orientation of both domains and might indirectly impair docking of cytosolic factors.

Gly-408, as previously stated by Leusen et al. (20), is at the beginning of a loop made up of three glycine residues (408GAGIG412 highlighted in red in Fig. 5D) included in a consensus sequence allowing the binding of the NADPH pyrophosphate moiety. Mutations of the smallest amino acid to the more bulky and charged residues (G408E or G408R) are rarely tolerated; they would induce a steric clash with a possible distant effect on FAD binding and might not be compatible with the entry of NADPH into its active site. Such global structural changes could also account for alterations in distant regions involved in the anchoring of cytosolic factors.

Cys-369, according to the homology model, is located in an extended region (residues 357–370) making extensive contacts with FAD in FNR members (Fig. 5, A and E) (31). Indeed, Cys-369 itself could be directly in contact with the ADP part of FAD as suggested by the complete loss of FAD binding in the C369K CGD mutant and leading to the disappearance of diaphorase activity. Strikingly, upon C369R mutation, complex assembly is impaired (Fig. 3C). From the location suggested by the model for the Cys-369 residue, its mutation by a positively charged arginine is likely to perturb the electrostatic environment and surface topology of this region (Fig. 5E). Lack of translocation of cytosolic factors by this mutant has also been observed before by Leusen et al. (20) in the X+-CGD neutrophils from the patient. From these observations, this region centered on Cys-369 may be proposed as a docking site for cytosolic factors, possibly p67Phox. A dual effect on both assembly after NADPH oxidase activation with soluble and particulate stimuli and FAD stabilization in this C369R mutant may for the first time suggest an activation mechanism occurring through FAD stabilization upon complex assembly.

Leu-546 is a highly conserved residue in Nox family members and is replaced by an isoleucine in the two FNRs shown in Fig. 2. According to Taylor's model it is localized in a secondary structure near the NADPH-binding site. Its mutation to Pro is likely to introduce a bend in this structural element with possible indirect secondary structural consequences that explain the defect in cytosolic factor translocation. Park et al. (40) demonstrated that the synthetic peptide 526–548 did not inhibit oxidase assembly in vitro indicating that Leu-546 is not directly involved in the anchoring of cytosolic factors during NADPH oxidase complex assembly.

According to homology with FNR family members for the Δ507QKT509-HIWA insertion, this mutation is in the potential binding site of the NADPH adenine moiety (504GLKQ507). However, in Nox proteins and in FRE1 from yeast (41), a supplementary cytosolic α-helical loop (484DESQANHFAVHHDEEKDVITG504) perturbs this structure. Previous evidence shows that an L505R mutation close to this stretch affects the oxidase complex activation process through alteration of p67phox activation of cytochrome b558, thus partially affecting access of NADPH to its binding site (17). The Δ507QKT509-HIWA insertion mutation close to Leu-505 leads to slight maintenance of oxidase complex assembly (Fig. 4, C and D) and diaphorase activity as we also found for the L505R mutation of Nox2.

We found that FAD binding by Nox2 protein was increased in PMA-activated plasma membranes from WT PLB-985 cells compared with nonactivated membranes (Table 2). In other words, the active conformation of the NADPH oxidase complex favors FAD binding in Nox2 perhaps by changing the affinity of its binding site. Our work corroborates previous results demonstrating that FAD binding to cytochrome b558 is facilitated during activation of phagocyte NADPH oxidase (42). It has previously been demonstrated that RacQ61L mutation lowers the FAD concentration required for the stabilization of the NADPH oxidase complex (43). One supposition could be that p67Phox, which is tightly bound to Nox2 through RacQ61L, may prevent FAD dissociation either directly or indirectly.

From our data, considering the position of the residues that are mutated in X+-CGD and their analysis in the context of a structural homology model of the Nox2 dehydrogenase domain, we find that most CYBB mutations leading to the X+-CGD phenotype surround the FAD/NADPH-binding sites. We propose that Thr-341, Pro-415, and Cys-537 are located in close proximity to the active site where mutations are not easily tolerated. Among them, Thr-341 may be directly involved in modulation of flavin “reactivity” without affecting normal cytosolic factor translocation. Gly-408, Leu-546, and Glu-568 are located in sequences necessary to maintain the integrity of the FAD/NADPH binding domains. In view of its external location, Cys-369 is probably not critical for the overall structural integrity of the protein. However, it might be a docking site for cytosolic factors influencing modulation of the FAD environment during the activation process. Further studies will be necessary to examine the mechanisms by which the successful assembly of the NADPH oxidase complex could control the increase of FAD incorporation in Nox2. In addition, structural data are expected to fully validate our previous proposals.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Prof. Mary C. Dinauer for the generous gift of X-CGD PLB-985 cells. The antibodies 54.1 and 44.1 were generous gifts from Prof. A. Jesaitis. The coordinates of the model of the C-terminal domain of Nox2 were kindly provided by Professors A. Segal and W. R. Taylor. We are very grateful to Cécile Martel and Michelle Mollin for their enthusiasm at work at the Chronic Granulomatous Disease Diagnosis and Research Center. Special thanks are extended to Lila Laval for excellent secretarial work and to Alison Mary Foote for editing the manuscript.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant N01-AI-30070 from United States Immunodeficiency Network and the Primary Immunodeficiency Disease Consortium. This work was also supported by grants from Joseph Fourier University Medical School and the Delegation for Clinical Research and Innovations, Grenoble, France.

- CGD

- chronic granulomatous disease

- PMA

- phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate

- INT

- iodonitrotetrazolium

- Nox

- NADPH oxidase

- superoxide

- GTPγS

- guanosine 5′-3-O-(thio)triphosphate

- cytb

- flavocytochrome b558.

REFERENCES

- 1.Balbridge C. W., Gerard R. W. (1933) Am. J. Physiol. 103, 235–236 [Google Scholar]

- 2.van den Berg J. M., van Koppen E., Ahlin A., Belohradsky B. H., Bernatowska E., Corbeel L., Español T., Fischer A., Kurenko-Deptuch M., Mouy R., Petropoulou T., Roesler J., Seger R., Stasia M. J., Valerius N. H., Weening R. S., Wolach B., Roos D., Kuijpers T. W. (2009) PLoS One 4, e5234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yu L., Zhen L., Dinauer M. C. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272, 27288–27294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aliverti A., Bruns C. M., Pandini V. E., Karplus P. A., Vanoni M. A., Curti B., Zanetti G. (1995) Biochemistry 34, 8371–8379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bedard K., Krause K. H. (2007) Physiol. Rev. 87, 245–313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marcoux J., Man P., Petit-Haertlein I., Vivès C., Forest E., Fieschi F. (2010) J. Biol. Chem. 285, 28980–28990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sumimoto H. (2008) FEBS J. 275, 3249–3277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Durand D., Cannella D., Dubosclard V., Pebay-Peyroula E., Vachette P., Fieschi F. (2006) Biochemistry 45, 7185–7193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Paclet M. H., Henderson L. M., Campion Y., Morel F., Dagher M. C. (2004) Biochem. J. 382, 981–986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Henderson L. M. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 33216–33223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Biberstine-Kinkade K. J., Yu L., Dinauer M. C. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 10451–10457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li X. J., Grunwald D., Mathieu J., Morel F., Stasia M. J. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 14962–14973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.von Löhneysen K., Noack D., Wood M. R., Friedman J. S., Knaus U. G. (2010) Mol. Cell. Biol. 30, 961–975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Segal A. W., West I., Wientjes F., Nugent J. H., Chavan A. J., Haley B., Garcia R. C., Rosen H., Scrace G. (1992) Biochem. J. 284, 781–788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rotrosen D., Yeung C. L., Leto T. L., Malech H. L., Kwong C. H. (1992) Science 256, 1459–1462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sumimoto H., Sakamoto N., Nozaki M., Sakaki Y., Takeshige K., Minakami S. (1992) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 186, 1368–1375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li X. J., Fieschi F., Paclet M. H., Grunwald D., Campion Y., Gaudin P., Morel F., Stasia M. J. (2007) J. Leukocyte Biol. 81, 238–249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Taylor W. R., Jones D. T., Segal A. W. (1993) Protein Sci. 2, 1675–1685 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stasia M. J., Li X. J. (2008) Semin. Immunopathol. 30, 209–235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leusen J. H., Meischl C., Eppink M. H., Hilarius P. M., de Boer M., Weening R. S., Ahlin A., Sanders L., Goldblatt D., Skopczynska H., Bernatowska E., Palmblad J., Verhoeven A. J., van Berkel W. J., Roos D. (2000) Blood 95, 666–673 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhen L., King A. A., Xiao Y., Chanock S. J., Orkin S. H., Dinauer M. C. (1993) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 90, 9832–9836 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhen L., Yu L., Dinauer M. C. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 6575–6581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yu L., Cross A. R., Zhen L., Dinauer M. C. (1999) Blood 94, 2497–2504 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bionda C., Li X. J., van Bruggen R., Eppink M., Roos D., Morel F., Stasia M. J. (2004) Hum. Genet. 115, 418–427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baniulis D., Nakano Y., Nauseef W. M., Banfi B., Cheng G., Lambeth D. J., Burritt J. B., Taylor R. M., Jesaitis A. J. (2005) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1752, 186–196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vergnaud S., Paclet M. H., El Benna J., Pocidalo M. A., Morel F. (2000) Eur. J. Biochem. 267, 1059–1067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cohen-Tanugi L., Morel F., Pilloud-Dagher M. C., Seigneurin J. M., Francois P., Bost M., Vignais P. V. (1991) Eur. J. Biochem. 202, 649–655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bradford M. M. (1976) Anal. Biochem. 72, 248–254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cross A. R., Yarchover J. L., Curnutte J. T. (1994) J. Biol. Chem. 269, 21448–21454 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kakinuma K., Kaneda M., Chiba T., Ohnishi T. (1986) J. Biol. Chem. 261, 9426–9432 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Karplus P. A., Daniels M. J., Herriott J. R. (1991) Science 251, 60–66 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fillat M. F., Edmondson D. E., Gomez-Moreno C. (1990) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1040, 301–307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Aliverti A., Piubelli L., Zanetti G., Lübberstedt T., Herrmann R. G., Curti B. (1993) Biochemistry 32, 6374–6380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Leusen J. H., de Boer M., Bolscher B. G., Hilarius P. M., Weening R. S., Ochs H. D., Roos D., Verhoeven A. J. (1994) J. Clin. Invest. 93, 2120–2126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nivière V., Fieschi F., Décout J. L., Fontecave M. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271, 16656–16661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yubisui T., Shirabe K., Takeshita M., Kobayashi Y., Fukumaki Y., Sakaki Y., Takano T. (1991) J. Biol. Chem. 266, 66–70 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nivière V., Fieschi F., Deæout J. L., Fontecave M. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 18252–18260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nivière V., Vanoni M. A., Zanetti G., Fontecave M. (1998) Biochemistry 37, 11879–11887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Calcaterra N. B., Picó G. A., Orellano E. G., Ottado J., Carrillo N., Ceccarelli E. A. (1995) Biochemistry 34, 12842–12848 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Park M. Y., Imajoh-Ohmi S., Nunoi H., Kanegasaki S. (1997) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 234, 531–536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shatwell K. P., Dancis A., Cross A. R., Klausner R. D., Segal A. W. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271, 14240–14244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hashida S., Yuzawa S., Suzuki N. N., Fujioka Y., Takikawa T., Sumimoto H., Inagaki F., Fujii H. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 26378–26386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Miyano K., Fukuda H., Ebisu K., Tamura M. (2003) Biochemistry 42, 184–190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]