Abstract

Approaches to the preparation of enantioenriched materials via catalytic methods that destroy stereogenic elements of a molecule are discussed. Although these processes often decrease overall molecular complexity, there are several notable advantages including material recycling, enantiodivergence and convergence, and increased substrate scope. Examples are accompanied by discussion of the critical design elements required for the success of these methods.

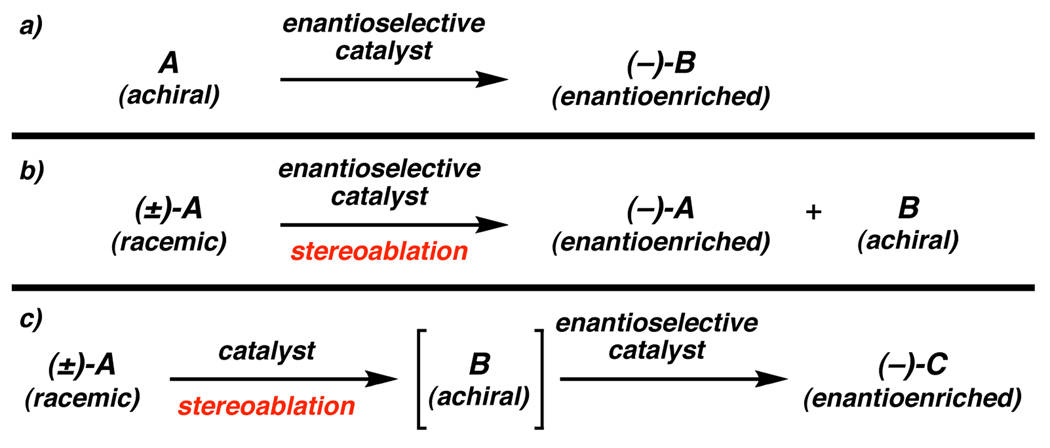

Since the inception of enantioselective catalytic methodology, the prevailing strategic approach has relied on inducing chirality into a prochiral atom by the generation of new asymmetric centers or axes (Figure 1a). While this tactic has proven extremely effective, the number of viable prochiral functional groups is relatively limited. An alternative approach to the production of enantioenriched materials is to begin with a racemic mixture and subsequently eliminate the intrinsic stereochemistry from a portion or all of this mixture. The scope of this approach to enantioselective catalysis is as wide as the number of chiral molecules in existence. While inherently a complexity minimizing process, this approach has proven to be valuable in the synthesis of chiral building blocks and more complex synthetic targets.

Figure 1.

Strategies for enantioselective catalysis.

In 2005, we defined the term “stereoablation” in the context of an enantioconvergent reaction.1 Our initial definition was “the conversion of a chiral molecule to an achiral molecule,” based on the Oxford English Dictionary definition for ablation: “the action or process of carrying away or removing; removal.”2 Upon further consideration of the importance of such methods in enantioselective chemical transformations, we have seen fit to expand the scope of this definition to include reactions where an existing stereocenter in a molecule is destroyed, but the intermediate molecule need not be wholly achiral.3 This revised definition thereby includes many other important advances. To date, few stereoablative strategies have been exploited for enantioselective catalysis, although notable exceptions include metal π-allyl alkylations4 and many dynamic kinetic resolutions.5 In this Emerging Area highlight, recent examples of novel approaches to asymmetric catalytic methods for stereoablation will be discussed. We hope to demonstrate that this is an important, though underutilized, method of asymmetric synthesis.6

When considering catalytic enantioselective stereoablative reactions, two possible regimes arise: one in which the stereoablative step is the enantioselective step (Figure 1b), and one in which stereoablation precedes the enantioselective step (Figure 1c). In the first case, a catalyst must selectively react with one enantiomer or enantiotopic group of the substrate to provide enantioenrichment. In the second case, a nonselective stereoablation is required before the enantioselective step.

Kinetic resolution is of the former type, selectively transforming one enantiomer of a racemic mixture to product. In addition to making enantiomer isolation a trivial process, stereoablative approaches often have the added capability of converting the achiral product back into a racemic starting material mixture by a relatively straightforward procedure. Recycling this material minimizes the waste common to many kinetic resolutions due to discard of the undesired enantiomer.

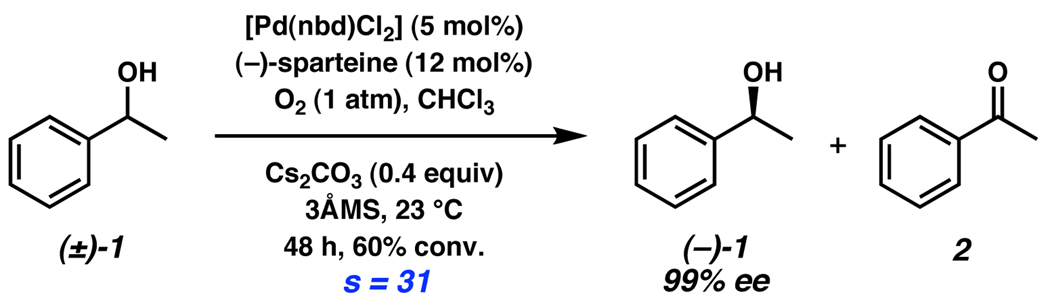

Recently, the Stoltz laboratory has reported an oxidative kinetic resolution (OKR) of secondary alcohols (Scheme 1).7,8,9,10 Utilizing molecular oxygen as the terminal oxidant, [Pd(nbd)Cl2] (nbd = norbornadiene) and (−)-sparteine catalyze the oxidation of alcohol (+)-1 to achiral ketone 2, leaving unreacted alcohol (−)-1 of high ee. Selective stereoablation by β–hydride elimination of a Pd-alkoxide to form product ketone has been shown to be enantiodetermining by extensive mechanistic7d,8 and computational7f studies. To date, a wide variety of secondary alcohols have been successfully resolved with this catalyst system.

Scheme 1.

Stoltz’s oxidative kinetic resolution of secondary alcohols.

Additionally, ketone 4, obtained in the resolution of alcohol (±)-3, can be recycled by reduction to racemic (±)-3 in quantitative yield, allowing greater than 50% overall yield of the enantioenriched alcohol after a second resolution (Scheme 2).

Scheme 2.

OKR in the Stoltz synthesis of (+)-amurensinine.

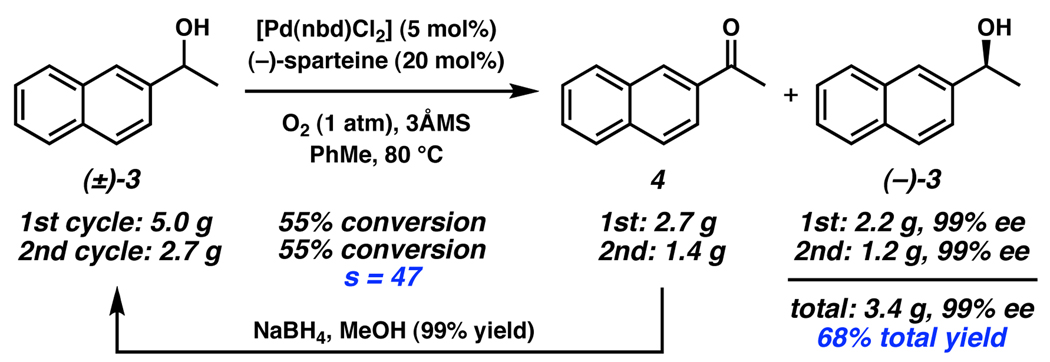

When other stereocenters are present in the alcohol, enantioenriched ketones can be obtained. In the Stoltz synthesis of (+)-amurensinine (7), racemic alcohol (±)-5 was resolved successfully using the [(sparteine)PdCl2] catalyst system (Scheme 3).11 In addition to highly enantioenriched alcohol (−)-5, diketone (−)-6a was obtained in 79% ee. This diketone presumably arises from overoxidation of the initial ketone product ((+)-6b, R = H2) in the presence of O2. In fact, the monoketone (+)-6b could be isolated with 77% ee at shorter reaction times, albeit with lower ee of alcohol (−)-5. Importantly, the products (−)-6a and (+)-6b have the opposite configuration at C(5), potentially providing access to (−)- amurensinine. In general, OKR of alcohols with multiple stereocenters can provide enantioenriched product ketones as well as alcohols, opening the door to enantiodivergent synthetic strategies.

Scheme 3.

OKR in the Stoltz synthesis of (+)-amurensinine.

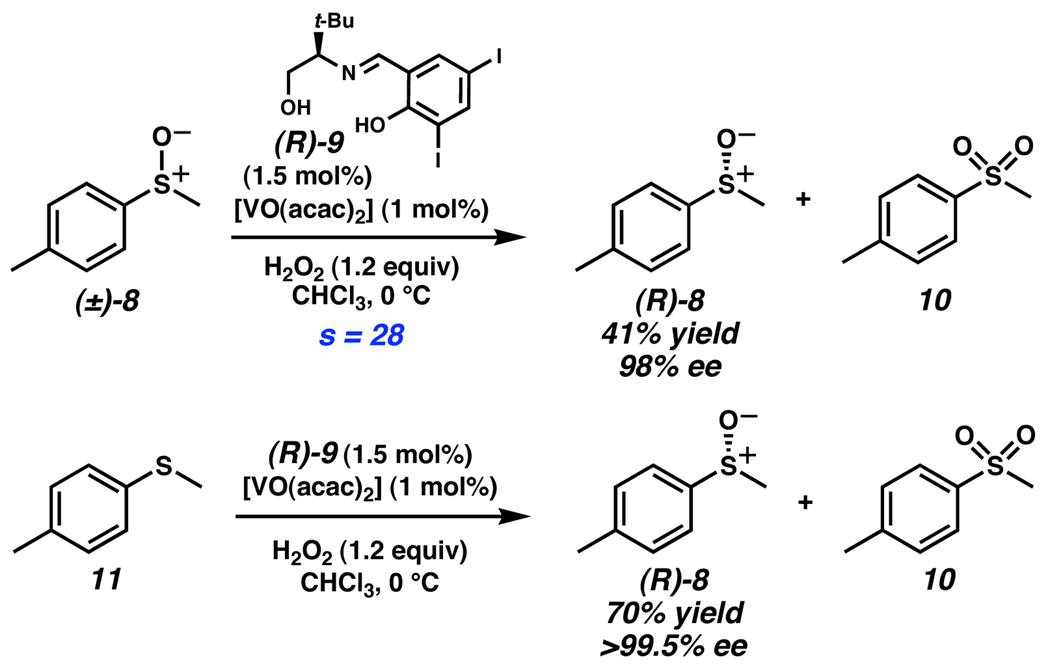

Oxidative resolution of sulfoxides has also been demonstrated. Unlike alcohol oxidation, in which C–H bond cleavage is stereoablative, in sulfoxide oxidation S–O bond formation leads to stereoablation. Of particular note is an example by Jackson and coworkers. It was found that a racemic mixture of sulfoxides was effectively resolved with a vanadium catalyst and diiodide ligand (R)-9 (Scheme 4).12 The high selectivity in sulfoxide oxidative kinetic resolution led them to investigate a tandem enantioselective sulfide oxidation followed by sulfoxide resolution. Treatment of sulfide 11 with their oxidative conditions provided sulfoxide (R)-8 in 70% yield and >99.5% ee, along with achiral sulfone 10. The combined effect of the two processes allows the synthesis of highly enantioenriched sulfoxides with higher yields than a typical kinetic resolution. Additionally, coupling two enantioselective reactions has the potential to bring poorly selective methods into the synthetically useful range because of the enhanced yield and product enantiopurity relative to the individual steps.

Scheme 4.

Jackson’s oxidation of sulfoxides and sulfides.

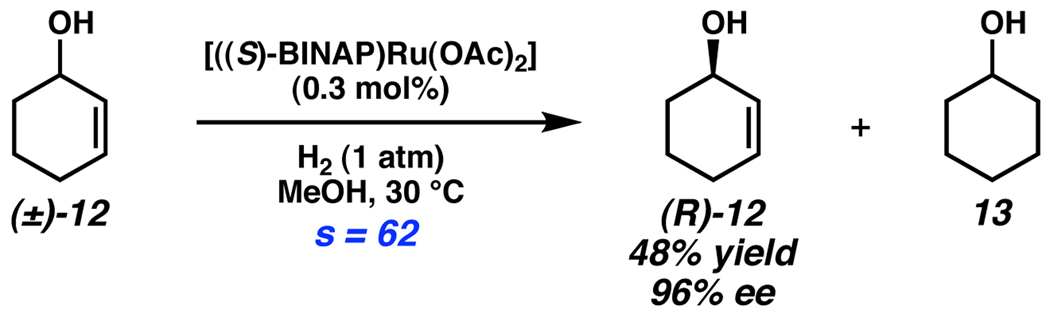

An unusual example of stereoablative kinetic resolution has been reported by Noyori.13 Hydrogenation of allylic alcohols with chiral catalyst [((S)-BINAP)Ru(OAc)2] results in kinetic resolution by symmetrizing one enantiomer of substrate (Scheme 5). This reductive kinetic resolution (RKR) is capable of resolving racemic alcohols such as (±)-12 with exceptionally high selectivity factors, providing achiral alcohol 13 as the byproduct. Although (R)-12 is obtained in high ee, there is currently no simple, direct method for recycling 13 back to (±)-12. Nonetheless, this RKR process provides a complementary method to the previously described OKR, using a reductive gas instead of an oxidative gas.

Scheme 5.

Noyori’s reductive kinetic resolution.

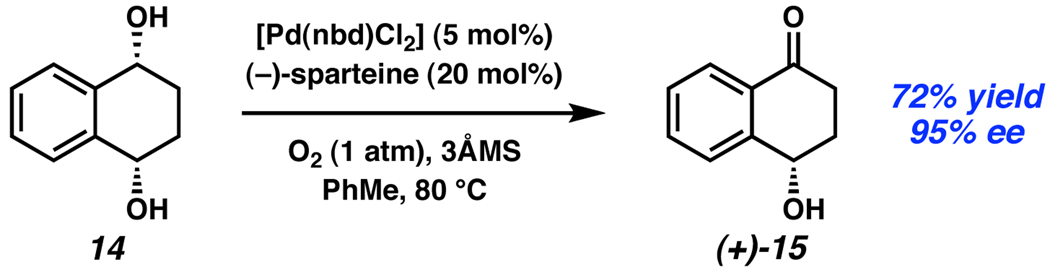

In addition to byproduct recycling, greater than 50% yield in a stereoablative process can be achieved by performing a desymmetrization. Such reactions utilize substrates that contain two enantiotopic functional groups, one of which selectively reacts with a chiral catalyst. Stoltz has reported a desymmetrization of meso diol 14 using their Pd-catalyzed oxidation conditions to obtain ketoalcohol (+)-15 in 72% yield with 95% ee (Scheme 6).7a

Scheme 6.

Stoltz’s desymmetrization of meso diol 14.

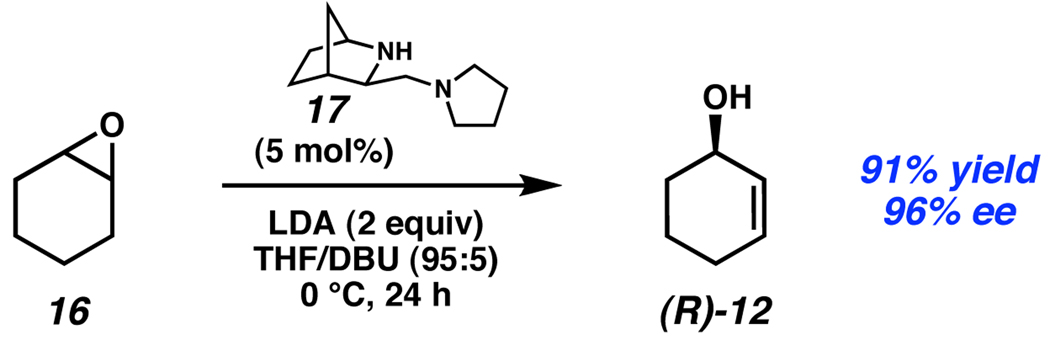

Catalytic enantioselective processes have also been employed in the desymmetrization of epoxides. Andersson has reported the use of chiral diamine 17 in the rearrangement of epoxides to allylic alcohols.14 Treatment of cyclohexene oxide (16) with 5 mol% 17 in the presence of LDA as the stoichiometric base provided (R)-2-cyclohexenol (12) in 96% ee (Scheme 7). Selective removal of one of the enantiotopic protons in the starting material accompanies destruction of one of the stereocenters of the epoxide in the elimination step. While there have been several other examples of catalytic asymmetric epoxide desymmetrization, this system has the largest reported substrate scope, with five allylic alcohols formed with good to excellent ee.

Scheme 7.

Andersson’s epoxide desymmetrization.

A second type of stereoablative enantioselective catalysis consists of stereoablation followed by enantioselective bond formation. In these enantioconvergent processes, both enantiomers of a racemic mixture are converted to an achiral intermediate, which is converted subsequently to an enantioenriched product in a separate process (Figure 1c). It is critical to avoid kinetic resolution in the stereoablative step in order to ensure good yield in a reasonable time.

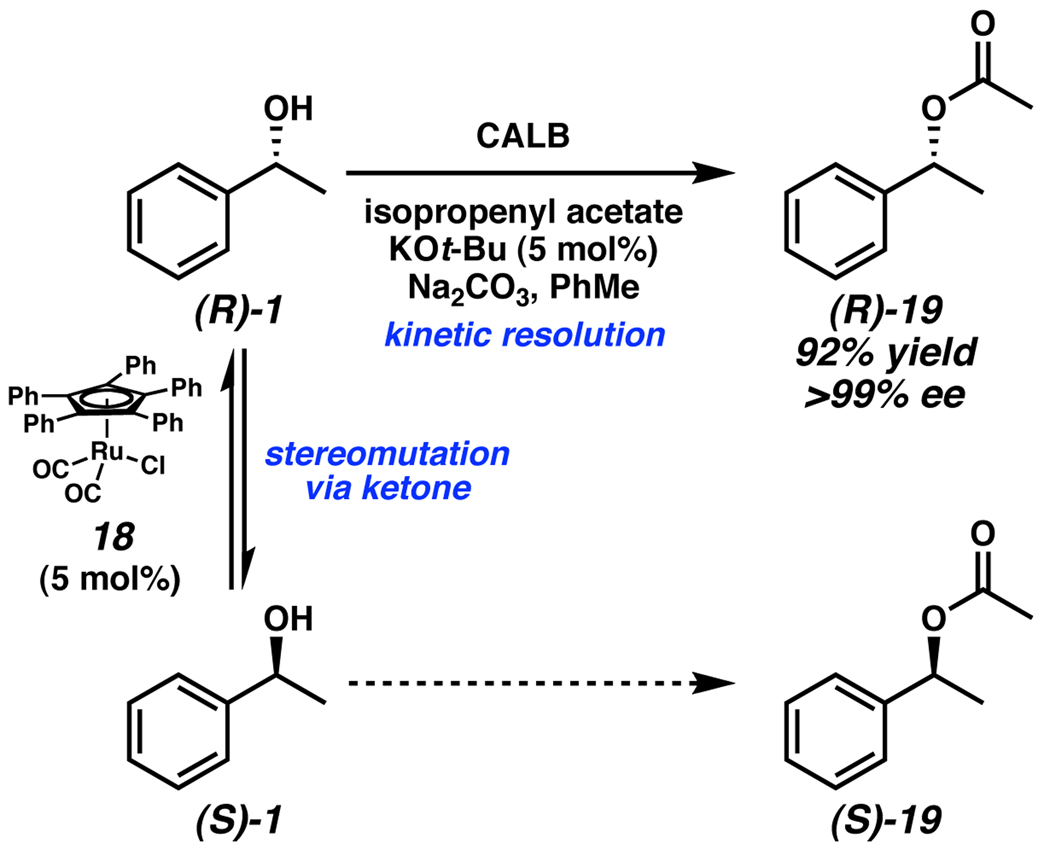

A prominent type of enantioconvergent catalysis is dynamic kinetic resolution (DKR) of racemic alcohols. A particularly elegant system was developed by Bäckvall, wherein an achiral metal catalyst (18) capable of rapid stereomutation via the corresponding ketone was coupled with selective acylating enzyme CALB (Scheme 8).15 The rates of these two simultaneous reactions are critical to the success of the process. The rate of stereomutation must be considerably greater than the rate of acylation in order to maintain an optimal 1:1 mixture of alcohol enantiomers for the enzymatic resolution. While kinetic resolution by acylation is a common approach to obtaining enantioenriched alcohols, the pairing of the stereoablative Ru catalyst and the acylation enzyme increases the overall efficiency of the reaction, as it allows yields greater than 50%. However, systems such as this are rare because the two concurrent catalytic reactions must tolerate one another.

Scheme 8.

Bäckvall’s dynamic kinetic resolution of alcohols.

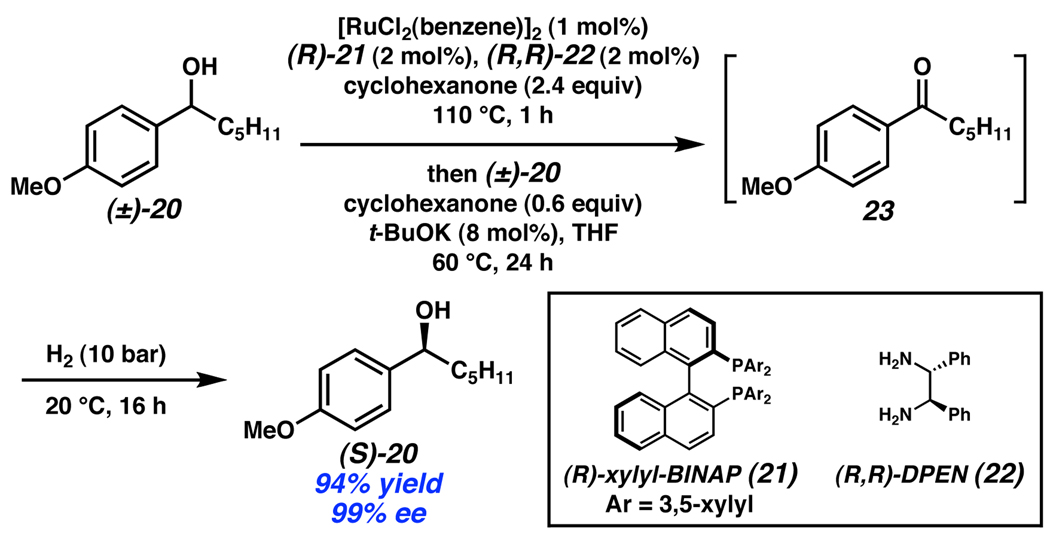

To avoid catalyst incompatibility, it is desirable to identify a single catalyst system capable of both the stereoablative step and enantioselective bond-forming step. In the realm of alcohol oxidation, Williams recently reported a deracemization of secondary alcohols utilizing a bifunctional Ru catalyst (Scheme 9).16 This system uses a single catalyst to perform a nonselective stereoablative oxidation followed by an enantioselective reduction. Exposure of racemic alcohol mixture (±)-20 to a catalyst formed in situ from [RuCl2(benzene)]2, phosphine 21, and (R,R)-DPEN (22) with cyclohexanone as a hydrogen acceptor produces achiral ketone 23. Pressurization of the reaction with H2 promotes enantioselective hydrogenation to the enantioenriched alcohol (S)-20. While the demonstrated substrate scope of this reaction is still limited, the system overcomes the shortcoming of low yields of kinetic resolution processes, providing benzylic alcohols in 82–97% yield. The unique ability of the Ru catalyst to operate via two distinct mechanisms is critical to the success of this method. According to the principle of microscopic reversibility, the nonselective transfer dehydrogenation must also be nonselective in the reverse reaction, and therefore cannot complete the deracemization. However, introduction of an atmosphere of H2 opens a different, highly selective mechanistic pathway leading to alcohols of high ee.

Scheme 9.

Williams’ deracemization of benzylic alcohols.

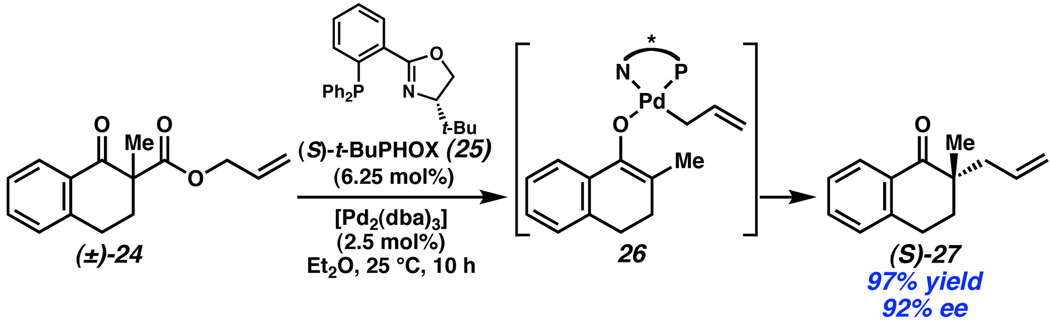

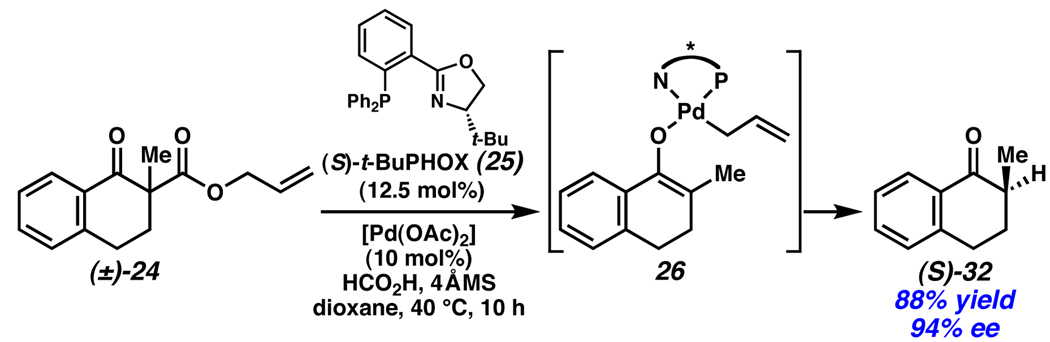

Recently, Stoltz established that racemic mixtures of allyl β-ketoesters are efficiently converted to enantioenriched α-quaternary cycloalkanones in an enantioconvergent process mediated by Pd and phosphinooxazoline (PHOX) ligands (Scheme 10).1 The mechanism is presumed to proceed through a Pd-enolate (26) formed by deallylation and stereoablative loss of CO2 from (±)-24. No significant kinetic resolution of the racemic starting materials was observed, and, coupled with the high chemical yield and enantioselectivity, these reactions represent an efficient method for the generation of enantioenriched building blocks for synthesis.17

Scheme 10.

Stoltz’s stereoablative enantioconvergent allylation.

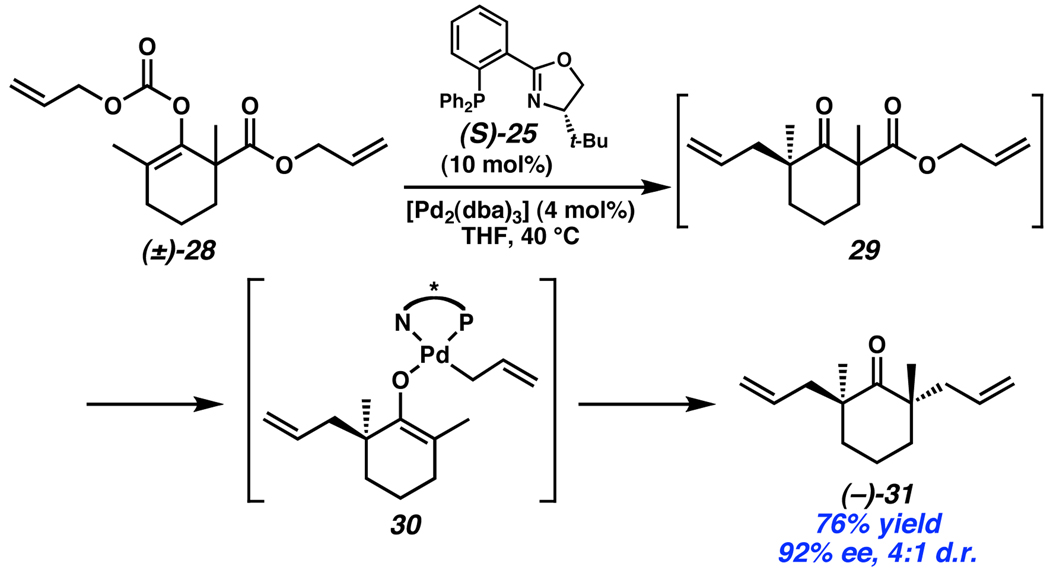

An interesting extension of this enantioconvergent method is the combination of a reactive allyl enol carbonate moiety with a latent allyl β-ketoester (28, Scheme 11). In the course of this reaction, a new stereocenter is first generated via decomposition of the allyl enol carbonate to reveal a Pd-enolate which undergoes enantioselective allylation. It is important that the catalyst be able to effectively overcome the inherent stereochemical preference of the substrate since the starting material is a racemic mixture. If the catalyst is unable to overcome the substrate preference, then a poor product d.r. will result. Notably, in this reaction, a 7:3 d.r. was obtained with Ph3P as ligand, while an enhanced d.r. of 4:1 was observed with (S)-t-BuPHOX (25) as ligand. In the second step of this double-allylation reaction, the newly revealed ketone in 29 activates the allyl ester toward decarboxylation and formation of Pd-enolate 30. Catalyst control over the configuration of the second stereocenter leads to a Horeau type enhancement18 of the overall ee of the product. In this case, product (−)-31 forms in 92% ee.

Scheme 11.

Stoltz’s cascade asymmetric allylation generating two quaternary stereocenters.

A second stereoablative reaction has been reported with the Pd/PHOX catalyst system. In this case, the putative Pd-enolate (26) is trapped with an alternate electrophile: a proton (Scheme 12).19 Again, the enantiopure catalyst is involved in both the bond-breaking and bond-forming steps, although the exact mechanistic course of the reaction remains unclear.20 The divergent reactivity of the enolate intermediate toward different electrophiles highlights the effectiveness and convenience of these stereoablative reactions. While the stereoablative step in both reactions is likely identical, two different structural motifs (α-quaternary and α-tertiary ketones) are both available from a common starting material.21

Scheme 12.

Stoltz’s stereoablative enantioconvergent protonation.

Catalyst design in catalytic enantioconvergent processes is especially important in cases such as the enantioselective decarboxylative allylation and protonation reactions described above. Since the catalyst is intimately involved in both the stereoablative (C–C bond-breaking) and enantioselective (C–C or C–H bond-forming) steps, it is critical that the first step be insensitive to substrate stereochemistry.

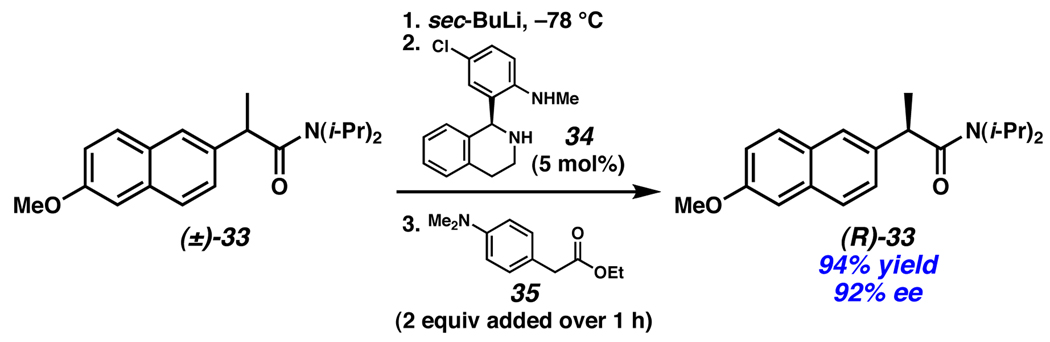

Analogous enolate methods are known in which stoichiometric reagents are used in the stereoablative step.22 Importantly, kinetic resolution of the starting material is avoided by employing an achiral reagent (e.g., sec-BuLi) for this process. Among these is the asymmetric Li-enolate protonation method of Vedejs, wherein a catalytic amount of a chiral amine (34) coupled with slow addition of stoichiometric phenylacetic acid derivative 35 leads to amide (R)-33 in high ee (Scheme 13).23

Scheme 13.

Vedejs’ enantioselective enolate protonation.

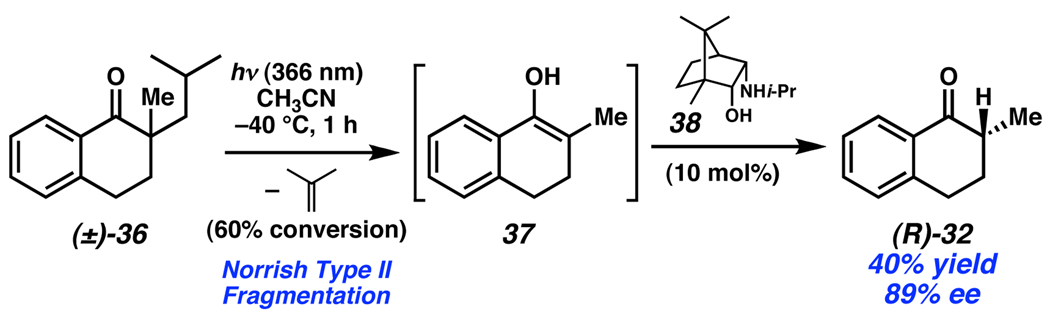

A unique, metal-free approach to stereoablation was developed by Hénin and Muzart.24 In this work, a light initiated Norrish Type II fragmentation is employed to eliminate the stereocenter present in tetralone 36 and access intermediate enol 37 (Scheme 14). Subsequently, amino alcohol 38 mediates tautomerization to the enantioenriched product (R)-32. Other amino alcohols provide higher levels of conversion and yield at the cost of enantioselectivity.

Scheme 14.

Muzart’s photolytic stereoablative process.

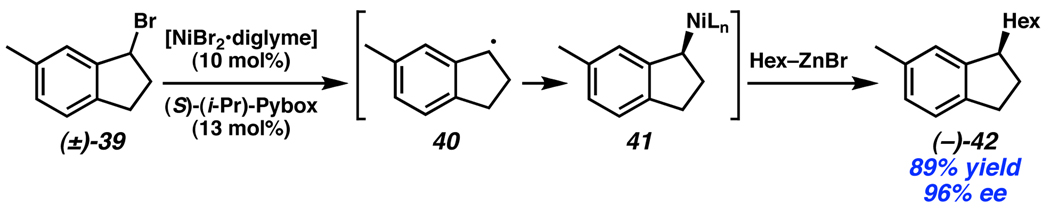

A recent report of a stereoablative enantioconvergent process for cross-coupling was detailed by Fu in 2005. In the reaction, a racemic α-bromo amide or benzylic bromide is treated with catalytic Ni, enantiopure (i-Pr)-Pybox ligand, and an alkylzinc reagent to create an enantioenriched tertiary stereocenter (Scheme 15).25 Although the mechanistic details have not been fully elucidated, it has been hypothesized that the racemic bromide (39) initially decomposes to a radical intermediate (40), negating the stereochemistry of the starting material. Subsequent combination of the carbon-centered radical with the Ni catalyst and Negishi-type coupling provides (−)-42 and completes the catalytic cycle.

Scheme 15.

Fu’s enantioconvergent Negishi coupling.

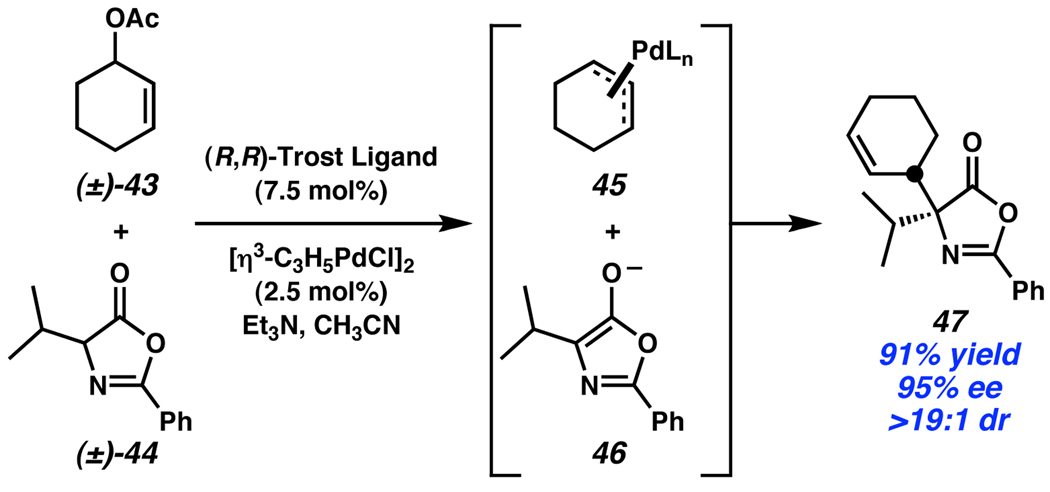

As a final example, Trost has reported an intermolecular system where both the electrophilic and nucleophilic partners are racemic (43 and 44, Scheme 16).26 It is proposed that (±)-43 is converted to an achiral η3-allyl ligand bound to Pd (45), which is subsequently attacked by deprotonated azlactone 46, forming product 47 with excellent enantio- and diastereocontrol. The remarkable stereochemical control in this work is made possible by two separate stereoablative steps.

Scheme 16.

Trost’s doubly-stereoconvergent allylic alkylation.

Conclusions

Although to date the primary focus during the development of enantioselective catalysis has been the creation of new stereocenters on prochiral substrates, asymmetric catalysis is not limited to the selective construction of new stereocenters. The selective destruction of stereogenic elements is also a viable, and increasingly important, technique that is beginning to show its utility in synthetic applications. This approach has several advantages including easily recycled byproducts, easily accessible racemic or meso starting materials, entries into enantioconvergent catalytic processes, and opportunities for enantiodivergent synthesis. As these new methods become more prominent and are further developed by the synthetic community they will surely play a pivotal role in the construction of enantiopure materials.

Acknowledgements

We thank NIH-NIGMS (R01GM080269-01), Eli Lilly (predoctoral fellowship to JTM), NDSEG (predoctoral fellowship to DCE), and NSF (predoctoral fellowship to DCE) for funding.

Biographies

Justin T. Mohr received his A.B. degree in chemistry from Dartmouth College in Hanover, NH, USA in 2003. In the same year, he joined the labs of Professor Brian Stoltz at Caltech, where he has worked toward his Ph.D. as a Lilly Fellow. His research interests include new methods of C–C bond formation, enantioselective catalysis, and total synthesis of natural products.

David C. Ebner received his B.S. in chemistry and B.A. in mathematics from the University of St. Thomas in St. Paul, MN, USA in 2002. He is currently pursuing his Ph.D. at Caltech in the labs of Professor Brian Stoltz. He has been awarded the National Defense Science and Engineering Fellowship and National Science Foundation Graduate Fellowship. His research interests involve the development of catalytic asymmetric reactions and their application to the total synthesis of natural products.

Brian M. Stoltz obtained his B.S. in chemistry and B.A. in German from Indiana University of Pennsylvania in 1993. He then earned his Ph.D. in 1997 in the labs of Professor John L. Wood at Yale University. Following an NIH postdoctoral fellowship in the laboratories of Professor E. J. Corey at Harvard University, he joined the faculty at Caltech in 2000, where he is currently a Professor of Chemistry. His research focuses on the design and implementation of new strategies for the synthesis of complex molecules possessing important biological properties, in addition to the development of new synthetic methods including asymmetric catalysis and cascade processes.

References

- 1.Mohr JT, Behenna DC, Harned AM, Stoltz BM. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2005;44:6924–6927. doi: 10.1002/anie.200502018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Simpson J, Weiner E, editors. The Oxford English Dictionary. 2nd edn. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 3.We suggest the following as a concise, inclusive definition for stereoablation: A chemical process where an existing stereogenic element in a molecule is eliminated.

- 4.For a recent review, see: Trost BM. J. Org. Chem. 2004;69:5813–5837. doi: 10.1021/jo0491004.

- 5.For a recent review, see: Pellissier H. Tetrahedron. 2003;59:8291–8327.

- 6.Recently, the related topic of racemization in asymmetric synthesis has been reviewed, see: Huerta FF, Minidis ABE, Bäckvall J-E. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2001;30:321–331.

- 7.(a) Ferreira EM, Stoltz BM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:7725–7726. doi: 10.1021/ja015791z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Bagdanoff JT, Ferreira EM, Stoltz BM. Org. Lett. 2003;5:835–837. doi: 10.1021/ol027463p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Bagdanoff JT, Stoltz BM. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2004;43:353–357. doi: 10.1002/anie.200352444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Trend RM, Stoltz BM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:4482–4483. doi: 10.1021/ja039551q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Caspi DD, Ebner DC, Bagdanoff JT, Stoltz BM. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2004;346:185–189. [Google Scholar]; (f) Nielson RJ, Keith JM, Stoltz BM, Goddard WA., III J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:7967–7974. doi: 10.1021/ja031911m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Ebner DC, Novák Z, Stoltz BM. Synlett. 2006;3533:3539. [Google Scholar]

- 8.A similar system was simultaneously reported, see: Sigman MS, Jensen DR. Acc. Chem. Res. 2006;39:221–229. doi: 10.1021/ar040243m. and references cited therein.

- 9.The selectivity factor s was determined using the equation: s = kfast/kslow = ln[(1−C)(1−ee)]/ln[(1−C)(1+ee)], where C = conversion, see: Kagan HB, Fiaud JC. In: Topics in Stereochemistry. Eliel EL, editor. Vol. 18. New York: Wiley & Sons; 1988. pp. 249–330.

- 10.For a recent review of alcohol oxidation, including enantioselective examples, see: Arterburn JB. Tetrahedron. 2001;57:9765–9788.

- 11.Tambar UK, Ebner DC, Stoltz BM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:11752–11753. doi: 10.1021/ja0651815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Drago C, Caggiano L, Jackson RFW. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2005;44:7221–7223. doi: 10.1002/anie.200503046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kitamura M, Kasahara I, Manabe K, Noyori R, Takaya H. J. Org. Chem. 1988;53:708–710. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Södergren MJ, Andersson PG. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998;120:10760–10761. [Google Scholar]

- 15.(a) Larsson ALE, Persson BA, Bäckvall J-E. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 1997;36:1211–1212. [Google Scholar]; (b) Perssson BA, Larsson ALE, Ray ML, Bäckvall J-E. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999;121:1645–1650. [Google Scholar]; (c) Martín-Matute B, Edin M, Bogár K, Bäckvall J-E. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2004;43:6535–6539. doi: 10.1002/anie.200461416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Adair GRA, Williams JMJ. Chem. Commun. 2007;2608:2609. doi: 10.1039/b704956k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.For related stereoablative, enantioconvergent allyation reactions, see: Nakamura M, Hajra A, Endo K, Nakamura E. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2005;44:7248–7251. doi: 10.1002/anie.200502703. Trost BM, Bream RN, Xu J. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2006;45:3109–3112. doi: 10.1002/anie.200504421. Burger EC, Baron BR, Tunge JA. Synlett. 2006:2824–2826. Schulz SR, Blechert S. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2007;46:3966–3970. doi: 10.1002/anie.200604553.

- 18.(a) Vigneron JP, Dhaenes M, Horeau A. Tetrahedron. 1973;29:1055–1059. [Google Scholar]; (b) Rautenstrauch V. Bull. Soc. Chim. Fr. 1994;131:515–524. [Google Scholar]; (c) Baba SE, Sartor K, Poulin J, Kagan H. Bull. Soc. Chim. Fr. 1994;131:525–533. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mohr JT, Nishimata T, Behenna DC, Stoltz BM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:11348–11349. doi: 10.1021/ja063335a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.For related Pd-catalyzed systems for enantioselective protonation, see: Hénin F, Muzart J. Tetrehedron: Asymmetry. 1992;3:1161–1164. Abouldhoda SJ, Hénin F, Muzart J, Thorey C, Behnen W, Martens J, Mehler T. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 1994;5:1321–1326. Abouldhoda SJ, Létinois S, Wilken J, Reiners I, Hénin F, Martens J, Muzart J. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 1995;6:1865–1868. Muzart J, Hénin F, Aboulhoda SJ. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 1997;8:381–389. Baur MA, Riahi A, Hénin F, Muzart J. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 2003;14:2755–2761. Sugiura M, Nakai T. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1997;36:2366–2368. Hamashima Y, Somei H, Shimura Y, Tamura T, Sodeoka M. Org. Lett. 2004;6:1861–1864. doi: 10.1021/ol0493711.

- 21.Despite the proposed common intermediate, experimental evidence suggests that that the mechanism of C–H bond-formation in the enantioselective protonation is substantially different from the mechanism of C–C bond-formation in the enantioselective allylation. See ref 19 for details.

- 22.Although many catalytic systems for enolate functionalization are known in the literature, the majority access the intermediate enolate from the corresponding achiral silyl enol ether in order to exclude Lewis basic amines. For representative examples, see: Yanagisawa A, Kikuchi T, Watanabe T, Kuribayashi T, Yamamoto H. Synlett. 1995:372–374. (b) Ref 20f; Yamashita Y, Odashima K, Koga K. Tetrahedron Lett. 1999;40:2803–2806.

- 23.Vedejs E, Kruger AW. J. Org. Chem. 1998;63:2792–2793. [Google Scholar]

- 24.(a) Hénin F, Muzart J, Pete J-P, M’boungou-M’passi A, Rau H. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1991;30:416–418. [Google Scholar]; (b) Hénin F, M’boungou-M’passi A, Muzart J, Pete J-P. Tetrahedron. 1994;50:2849–2864. [Google Scholar]

- 25.(a) Fischer C, Fu GC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:4594–4595. doi: 10.1021/ja0506509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Arp FO, Fu GC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:10482–10483. doi: 10.1021/ja053751f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Trost BM, Ariza X. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1997;36:2635–2637. [Google Scholar]