Abstract

Background

Phosphorus binders are used to treat hyperphosphatemia in maintenance dialysis patients, in whom the use of these medications has been associated with lower mortality in some observational studies. It is not clear if similar benefits can be seen in patients with non–dialysis-dependent chronic kidney disease (CKD).

Study design

Historical cohort.

Setting and participants

1,188 men with moderate and advanced non–dialysis-dependent CKD at a single medical center.

Predictor

The administration of any phosphorus binder.

Outcomes and measurements

We examined associations of any phosphorus binder administration with all-cause mortality and with the slopes of estimated glomerular filtration rate by using time-varying Cox models and mixed effects models. The associations were also examined in intention-to-treat type analyses and in 133 patient-pairs matched according to propensity scores.

Results

344 patients were treated with a binder; 658 patients died (mortality rate, 141/1000 patient-years; 95% CI, 131–153) during a median follow-up of 3.1 years. Treatment with binders was associated with significantly lower mortality (adjusted HR, 0.61; 95% CI, 0.45–0.81; p<0.001). Results were similar when exposure was modeled in intention-to-treat type analyses and when examining propensity-matched patients. Binder use was not associated with significant changes in kidney function loss.

Limitations

Results may not apply to all non–dialysis-dependent CKD patients.

Conclusions

The administration of phosphorus binders is associated with lower mortality in men with moderate and advanced non–dialysis-dependent CKD. Clinical trials are needed to determine the risks and benefits of phosphate binders in this patient population.

Index words: phosphorus binders, chronic kidney disease, mortality, CKD progression, hyperphosphatemia

Serum phosphorus concentration is usually maintained within the normal range by increasing the fractional excretion of phosphorus, as a result of increased FGF-23 (fibroblast growth factor 23) and serum parathyroid hormone (PTH) release stimulated by an increased phosphorus load.1 Elevations in serum phosphorus concentration, however, occur in patients with advanced chronic kidney disease (CKD), especially after their progression to end-stage renal disease (ESRD).1 Hyperphosphatemia represents a novel mortality risk factor in patients with CKD on maintenance hemodialysis therapy,18;33 and even high-normal levels of serum phosphorus appear associated with higher mortality in both the general population and persons with non–dialysis-dependent CKD18;33 and with a higher incidence of end stage renal disease (ESRD) in patients with moderate and advanced non–dialysis-dependent CKD.18;33 High levels of FGF-23 and PTH are also associated with increased mortality in dialysis patients18;33 and in non–dialysis-dependent CKD.17 Hence, it is possible, although not yet proven, that interventions aimed at lowering serum phosphorus levels improve survival even in non–dialysis-dependent CKD patients with seemingly normal or borderline-elevated serum phosphorus levels.

Medications that bind intestinal phosphorus represent the most commonly applied therapy of hyperphosphatemia in CKD. The lack of randomized controlled trials examining the impact of phosphorus binders against placebo therapy on hard clinical end points in CKD has hampered our ability to apply phosphate binders as a means to improve clinical outcomes beyond lowering serum phosphorus. A single observational study has found that the use of phosphorus binders in hemodialysis patients was associated with lower mortality.18 To the best of our knowledge no such studies have been performed in patients with non-dialysis dependent CKD.

We examined associations of phosphorus binder administration with all-cause mortality and with the slopes of estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) in male US veterans with moderate and advanced non–dialysis-dependent CKD at a single medical institution.

METHODS

Study population and data collection

We studied all 1,259 patients referred for evaluation of non–dialysis-dependent CKD at Salem Veteran Affairs Medical Center between January 1, 1990, and June 30, 2007, and followed them until April 1, 2009. Ten females and 6 patients whose race was other than white or black were excluded; a further 55 patients who were first exposed to phosphorus binders after the initiation of renal replacement therapy were also excluded. The final cohort consisted of 1,188 patients.

Baseline characteristics were recorded at the initial evaluation in the Nephrology clinic for all patients, and the same characteristics were reassessed at the time of the initial phosphorus binder administration in treated patients for propensity score calculations. These included demographic and anthropometric characteristics, co-morbid conditions including the Charlson Comorbidity Index and laboratory results, as detailed elsewhere.18;33 Phosphate binder exposure was assessed by reviewing electronic pharmacy records from the Veterans Administration Computerized Patient Records System, and was defined as the dispensation of a single or of multiple prescriptions for any calcium containing medication (with the recording of the daily dose of elemental calcium) or a non-calcium-containing phosphorus binder, with sevelamer hydrochloride being the only such medication found in the studied cohort. Longitudinal exposure to binders was assessed by recording the dates of subsequent pharmacy refills. In primary analyses, exposure to binders was analyzed on an as-treated basis; in sensitivity analyses, exposure was defined in intention-to-treat manner by considering patients with sustained binder administration as “treated” even if they subsequently discontinued their binders. Sustained exposure was defined as at least 10 dispensations of a binder, which was present in 86% of all treated patients. Follow-up data recorded during the entire follow-up was also extracted and utilized in time-varying analyses by time-updating the following variables: all medication use, body mass index, blood pressure and all the laboratory parameters. Serum calcium concentration was corrected for serum albumin concentration using the formula21: Corrected calcium = Measured calcium + 0.8*(4-serum albumin level in g/dl). Glomerular filtration rate was estimated using the 4-variable Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study (MDRD)22 equation and categorized according to the staging system introduced by the National Kidney Foundation's Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative (KDOQI) clinical practice guidelines regarding evaluation, classification, and stratification of CKD.23 All biochemical measurements were performed in a single laboratory at the Salem Veteran Affairs Medical Center.

Statistical analyses

Data points were missing for CCr (1%), body mass index (14%), serum albumin (1%), phosphorus (2%), alkaline phosphatase (9%), blood cholesterol (2%), hemoglobin (0.3%), WBC (0.9%), percent lymphocytes in WBC (1%), 24-hour urine protein (3%) and smoking (5% missing). Multivariable analyses were conducted using unimputed (complete) data, which was available in 832 patients.

Patients were considered lost to follow-up if no contact was documented with them for more than six months, and they were censored at the date of the last documented contact. Outcome measures were overall (pre- and post-dialysis) all-cause mortality (ascertained from VA electronic records) and the slopes of estimated GFR vs. time.

The starting time for analyses was the date of the first encounter in the Nephrology Clinic; patients whose treatment with binders started at a later time were categorized as untreated until the time their treatment started. The association of binder use with all-cause mortality was evaluated in time-varying Cox models. The association between binder administration and the slopes of eGFR vs. time was examined in generalized linear mixed effects models allowing for a random intercept and slope of eGFR and of binder use, estimating the variance components by using the maximum likelihood method. Most patients did not start binder therapy at the beginning of the follow-up period; hence the eGFR slopes associated with binder therapy were modeled such as to allow for an intraindividual change in slopes corresponding to the initiation of binders. The effect of binder administration on progression of CKD was determined by comparing the slopes of eGFR after a binder was initiated with the pre-treatment slopes of the same patients. The change in eGFR from baseline until death, start of dialysis or loss of follow-up (whichever occurred first) was studied using a median of 17 serum creatinine measurements (range, 1–135) by applying a two stage model formulation.24 In such a model the level 1 change describes intraindividual changes in eGFR and the level 2 model describes how the change coefficients differ across participants. Model fit was determined by using the Akaike Information Criterion. Selection of variables to be included in multivariable models was done by determining probable confounders25 based on baseline characteristics and on theoretical considerations. To account for the different time periods when patients were enrolled in the study multivariable models were adjusted for a dummy variable corresponding to the enrollment period (1990–1995, 1996–2000 or post-2000). Final Cox models were adjusted for case mix (age, race, CCr, diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease, blood pressure, body mass index, smoking status, enrollment period and calcitriol use) and for laboratory parameters (estimated GFR, serum albumin, bicarbonate, calcium, phosphorus, alkaline phosphatase, blood hemoglobin, WBC, percentage of lymphocytes and 24 hour urine protein). Analyses of slopes were also adjusted for the presence or absence of deaths or ESRD events (in order to account for potential informative censoring due to these events). Sensitivity analyses were conducted to separately assess the association of calcium-containing binders with the same outcomes. To alleviate possible selection bias involving patients treated with binders, we calculated propensity scores from pertinent demographic and clinical characteristics and matched treated and untreated patients by their scores, resulting in a matched cohort of 266 patients.

Interactions were assessed by performing subgroup analyses by baseline age, race, estimated GFR (in Cox models only), serum calcium and phosphorus and the presence or absence of DM and CVD. Due to possible confounding by better nutritional status in patients with higher serum phosphorus levels, subgroup analyses were also performed by dividing patients along the median baseline values of various markers of protein-energy wasting:18;33 BMI, serum albumin, blood cholesterol, WBC count and the percentage of lymphocytes in WBC. Sensitivity analyses were performed by analyzing separately a more contemporary subgroup of patients enrolled after January 1, 2001 and by repeating analyses after substituting missing data points with imputed values using multiple imputation procedures. Due to the possibility that patients taking calcium-based medications might have received these for non-phosphate binding purposes, we performed additional sensitivity analyses by categorizing patients according to the amount of elemental calcium intake, by excluding patients who took <1000 mg of elemental calcium/day and by restricting analyses to patients using a combination of calcium-based binders and sevelamer hydrochloride. P values of less than 0.05 were considered significant. Statistical analyses were performed using STATA statistical software version 11 (STATA Corp, www.stata.com). The study protocol was approved by the Research and Development Committee at the Salem Veteran Affairs Medical Center.

RESULTS

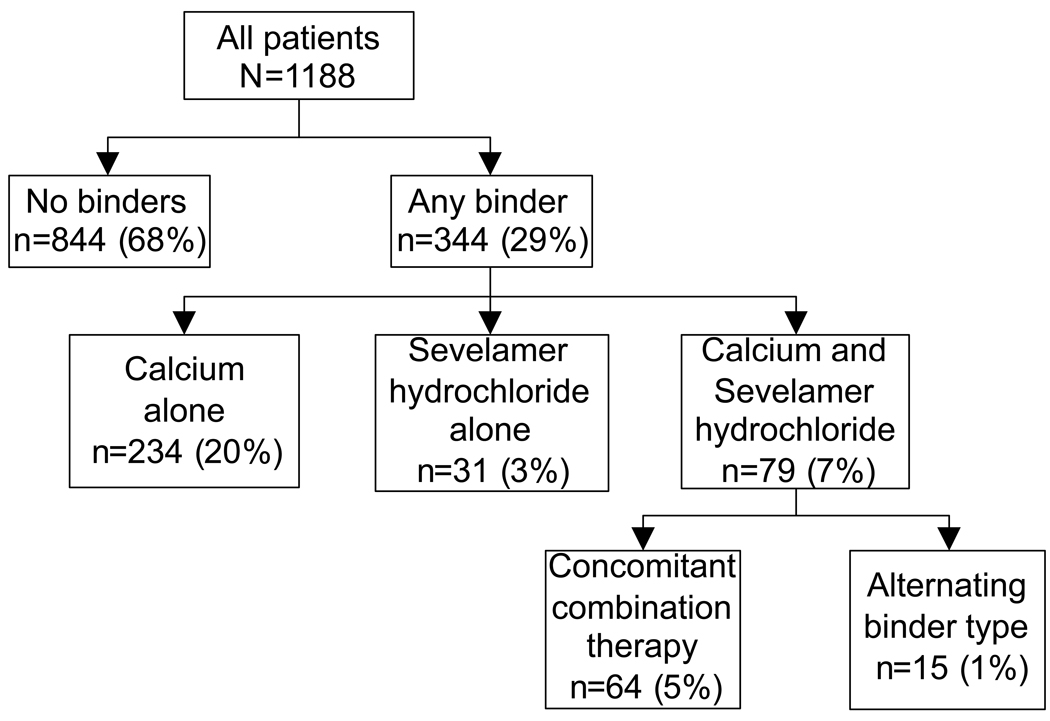

The mean (±SD) age of the cohort at baseline was 69±11 years, 24% of patients were black and their mean eGFR was 38±17 ml/min/1.73m2. Most patients had CKD stages 3 (57%) and 4 (30%), with few patients categorized as CKD stages 1 (2%), 2 (8%) and 5 (4%). The mean (±SD) baseline serum calcium and phosphorus were 9.4±0.5 and 3.8±0.8 mg/dl, with 5% and 12% of patients having at least one serum calcium and/or phosphorus level above the upper limit of normal (>10.3 and >4.6 mg/dl, respectively). Figure 1 shows the flow chart of the distribution of patients according to their phosphorus binder use. Overall 344 (29%) patients received some form of binder, with the majority of them using calcium-based binders, and a minority using solely sevelamer hydrochloride or a combination of the two. A binder was dispensed a median (25th–75th percentiles) of 25 times (15–39) in treated patients, who started using binders a median of 1.0 years (0.2–2.9) after the start of follow-up. The median dose of daily elemental calcium intake in patients taking calcium-based binders was 780 mg/day (507–1014). A total of 658 patients died (mortality rate of 141/1000 patient-years [95% confidence interval, 131–153]; 150 deaths (23%) occurred after dialysis initiation), and 215 patients reached ESRD (45/1000 patient-years; 95%CI, 39–51) during a median follow-up of 3.1 years. Forty five patients (4%) were lost to follow-up and their characteristics were not significantly different (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Distribution of patients according to their treatment or non-treatment with phosphorus binders and according to the types of phosphorus binders administered.

Demographic and clinical characteristics in patients divided according to their binder use are shown in Table 1. Patients treated with a binder were more likely to be black and to be active smokers, and were more likely to use calcitriol and aspirin, had higher Charlson comorbidity index, systolic blood pressure, serum phosphorus, WBC count and 24 hour urine protein, and lower body mass index, eGFR, serum bicarbonate, calcium, albumin, blood hemoglobin and percentage of lymphocytes in WBC. Table 2 shows the change in time (slopes) of serum calcium and phosphorus in subgroups of patients according to their binder use or non-use. Serum phosphorus showed a rise over time in patients treated with binders, with no significant change in patients not treated with binders. Serum calcium level did not change significantly in either group.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients, according to use or non-use of phosphorus binders

| No binder (n=844) |

Any binder (n=344) |

p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 69.6 ± 10.6 | 68.5 ± 10.6 | 0.1 |

| Race (Black) | 184 (22) | 96 (28) | 0.02 |

| DM | 448 (53) | 195 (57) | 0.2 |

| atherosclerotic CVD | 477 (57) | 201 (58) | 0.5 |

| Smoking | 179 (22) | 100 (30) | 0.005 |

| Comorbidity index | 2.3 ± 1.6 | 2.8 ± 1.8 | <0.001 |

| Calcitriol use | 207 (25) | 155 (45) | <0.001 |

| Aspirin use | 459 (54) | 237 (69) | <0.001 |

| ACEi/ARB use | 632 (75) | 263 (76) | 0.3 |

| Statin use | 556 (66) | 222 (65) | 0.2 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 29.6 ± 5.9 | 28.4 ± 5.8 | 0.006 |

| SBP (mmHg) | 147 ± 26 | 150 ± 25 | 0.04 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 73 ± 16 | 73 ± 15 | 0.6 |

| eGFR (ml/min/1.73m2) | 40.5 ± 17.1 | 23.1 ± 12.9 | <0.001 |

| Serum Albumin (g/dl) | 3.7 ± 0.5 | 3.5 ± 0.5 | <0.001 |

| Serum alkaline phosphatase (U/L) | 89 ± 42 | 95 ± 52 | 0.07 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dl) | 185 ± 54 | 191 ± 57 | 0.08 |

| Serum calcium (mg/dl) | 9.5 ± 0.5 | 9.3 ± 0.6 | <0.001 |

| Serum phosphorus (mg/dl) | 3.7 ± 0.7 | 4.4 ± 1.0 | <0.001 |

| Serum bicarbonate (mEq/l) | 26.0 ± 3.3 | 24.4 ± 3.8 | <0.001 |

| Blood Hb (g/dl) | 12.9 ± 1.9 | 11.9 ± 1.7 | <0.001 |

| Blood WBC count (1000/mm3) | 7.5 ± 2.2 | 7.9 ± 2.6 | 0.01 |

| Blood lymphocytes (%WBC) | 23.4 ± 8.4 | 21.4 ± 8.1 | <0.001 |

| Proteinuria (g/24h) | 502 (455–554) | 1,421 (1,229–1,643) | <0.001 |

Note: Data is presented as means ± SD, number (% of total) or geometric means (95% confidence interval), and was recorded at the initial encounter in patients not treated with binders, and at the time phosphorus binders (of any type) were initiated in treated patients. Comparisons were made by t test or by chi2 test.

Conversion factors for units: eGFR in mL/min/1.73m2 to mL/s/1.73m2, × 0.01667; serum albumin in g/dl to g/L, × 10; serum total cholesterol in mg/dL to mmol/L, × 0.02586; serum calcium in mg/dl to mmol/L, × 0.2495; serum phosphorus in mg/dl to mmol/L, × 0.3229; hemoglobin in g/dL to g/L, × 10; proteinuria in mg/24 hrs to g/24 hrs, ×0.001.

Abbreviations: DM, diabetes mellitus; CVD, cardiovascular disease; ACEi/ARB, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor/angiotensin receptor blocker; BMI, body mass index; SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; Hb, hemoglobin; WBC, white blood cell.

Table 2.

Changes in serum calcium and serum phosphorus levels over time, by patients’ binder treatment status

| No binder (n=844) |

Any binder (n=344) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Δ | P | Δ | P | |

| Serum Calcium (mg/dl/y) | 0.01 (−0.01, 0.01) |

0.7 | 0.01 (−0.01, 0.03) |

0.1 |

| Serum Phosphorus (mg/dl/y) | 0.02 (−0.01, 0.03) |

0.1 | 0.08 (0.04, 0.12) |

<0.001 |

Values in parentheses indicate 95% CI. Changes of serum calcium and phosphorus over time were estimated in generalized linear mixed effect models. Changes in patients treated with a binder were assessed after the initiation of binder therapy.

Conversion factors for units: serum calcium in mg/dl to mmol/L, × 0.2495; serum phosphorus in mg/dl to mmol/L, ×0.3229.

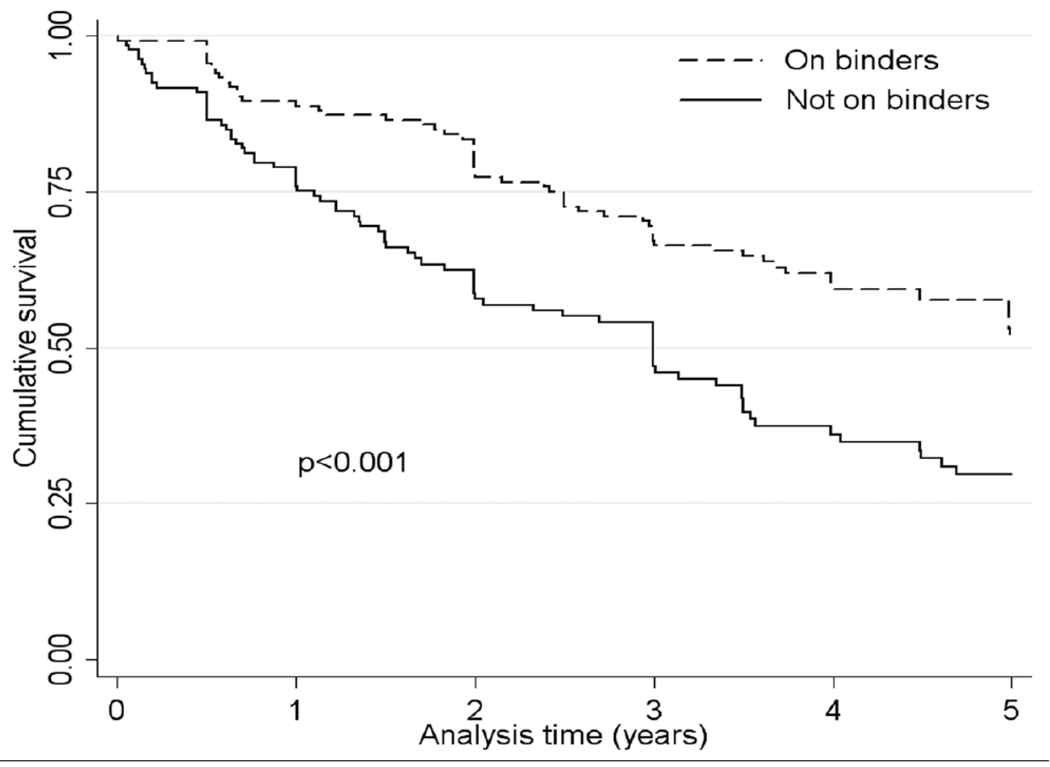

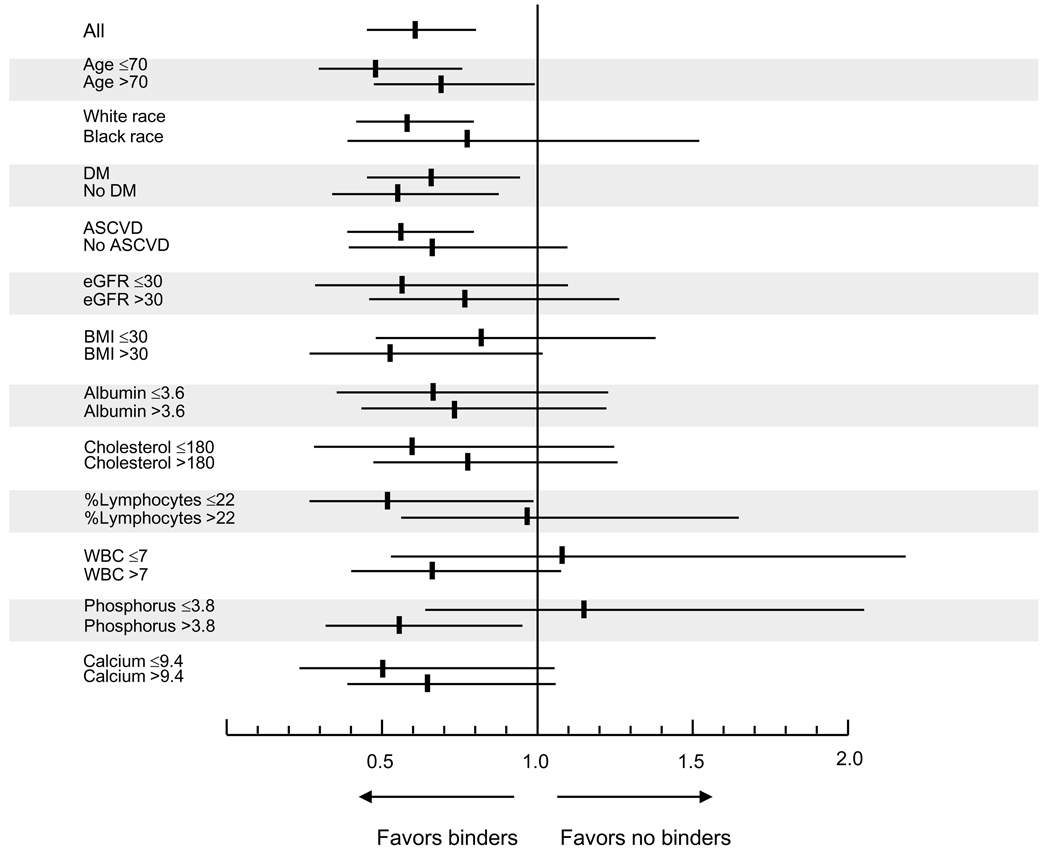

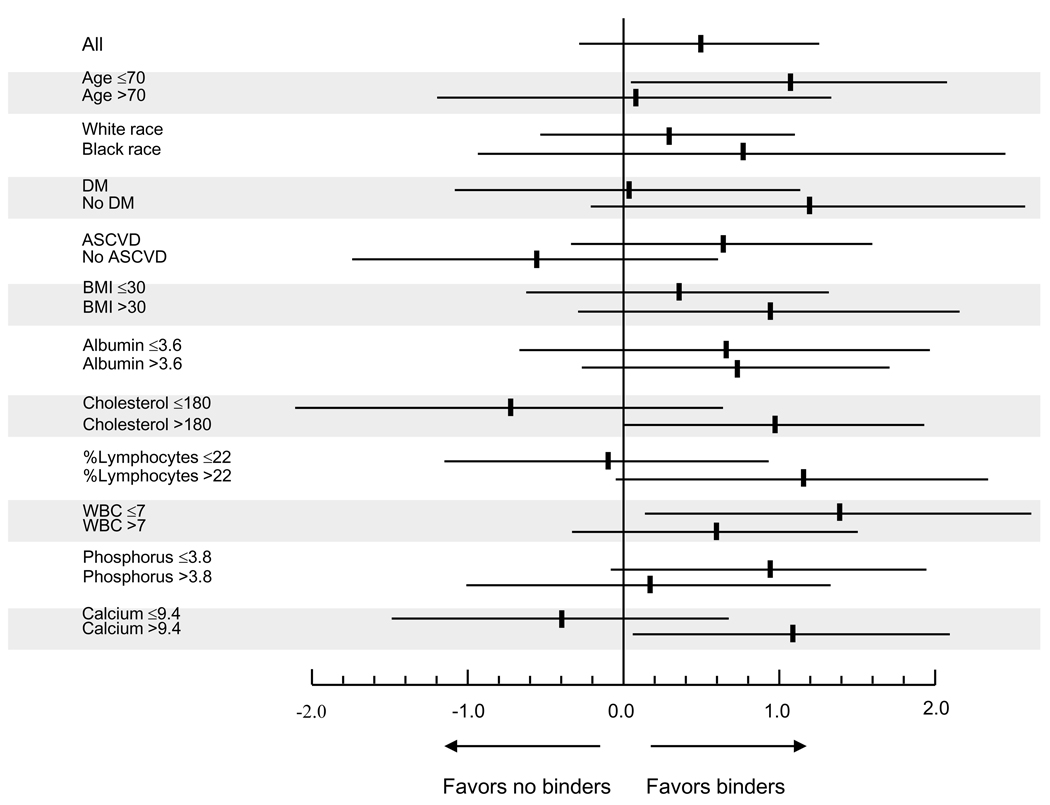

Crude overall all-cause mortality was higher in patients receiving binders, but adjustment for case-mix characteristics attenuated this difference, and full adjustment for case mix and biochemical characteristics revealed that binder use was associated with significantly lower all-cause mortality (Table 3). No single independent covariate was disproportionately responsible for the changes in the directionality of the associations during adjustments, including adjustment for serum phosphorus; the fully adjusted hazard ratio for mortality without adjustment for serum phosphorus was 0.67 (0.51–0.89), p=0.005. Associations were similar when examining propensity score-matched patients (Figure 2 and Table 3) and when defining exposure to binders on an intention-to-treat basis (0.77 (0.62–0.96), p=0.02). Subgroup analyses indicated that the mortality benefit associated with binder use appeared to be restricted to patients with higher serum phosphorus (Figure 3).

Table 3.

Outcomes associated with the administration of phosphorus binders.

| All patients (N=1188) |

Propensity-matched patients (n=266) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Mortality HR | Unadjusted | 1.15 (0.95, 1.41), p=0.3 | 0.57 (0.42, 0.76), p<0.001 |

| Case-mix adjusted | 1.00 (0.80, 1.28), p=0.7 | ||

| Case-mix + labs adjusted | 0.61 (0.45, 0.81), p<0.001 | ||

| Slope of eGFR (ml/min/1.73m2 per y) |

Unadjusted | 0.77 (0.02, 1.52), p=0.04 | 0.68 (−0.27, 1.63), p=0.2 |

| Case-mix adjusted | 0.87 (0.06, 1.68), p=0.03 | ||

| Case-mix + labs adjusted | 0.49 (−0.28, 1.26), p=0.2 |

Outcomes were assessed in Cox models for overall mortality and in mixed effects models for slopes of eGFR. Mortality is compared between treated and untreated patients. Slopes of eGFR are compared between pre-treatment and post-treatment state of patients receiving a binder; positive slopes indicate favorable changes (decreased loss of function), negative slopes indicate unfavorable changes (increased loss of function). Adjustments were made for case mix (age, race, Charlson comorbidity index, diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease, blood pressure, body mass index, smoking status, enrollment period and the use of calcitriol) and for case mix + laboratory parameters (eGFR (Cox models only), serum albumin, bicarbonate, calcium, phosphorus, alkaline phosphatase, blood hemoglobin, white blood cell count, percentage of lymphocytes and 24 hour urine protein) + presence or absence of death and end stage renal disease (for slopes only). Propensity-matched models are unadjusted.

Abbreviations: HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate.

Figure 2.

Survival curves in 133 patients administered any type of phosphorus binder versus 133 patients on no phosphorus binder, matched by their propensity scores reflecting the likelihood of binder administration.

Figure 3.

Hazard ratio (95% confidence intervals) of overall all-cause mortality in various subgroups of patients treated with a phosphorus binder vs. not treated with any binder. All results are adjusted for age, race, Charlson comorbidity index, diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease, blood pressure, body mass index, smoking status, enrollment period, the use of calcitriol, estimated GFR, serum albumin, bicarbonate, calcium, phosphorus, alkaline phosphatase, blood hemoglobin, white blood cell count, percentage of lymphocytes and 24 hour urine protein.

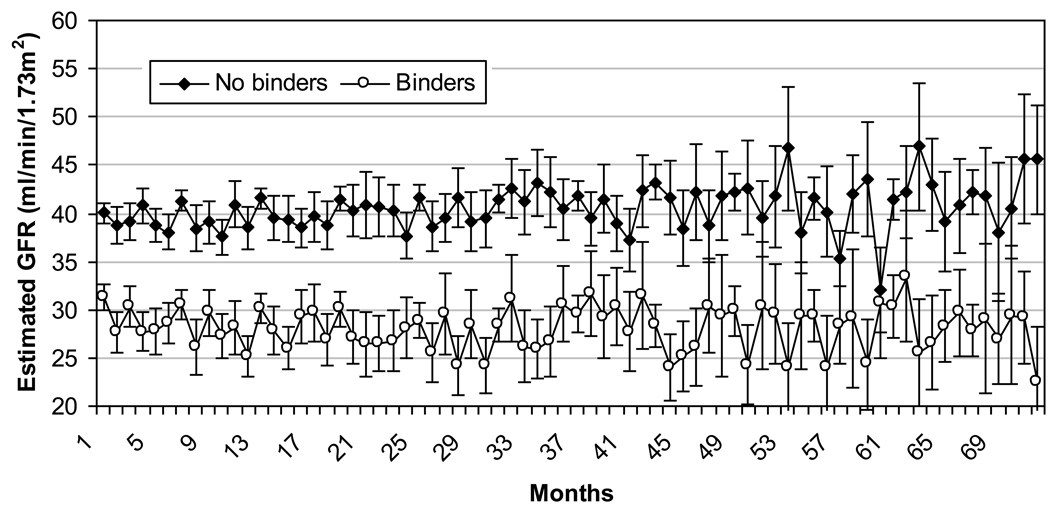

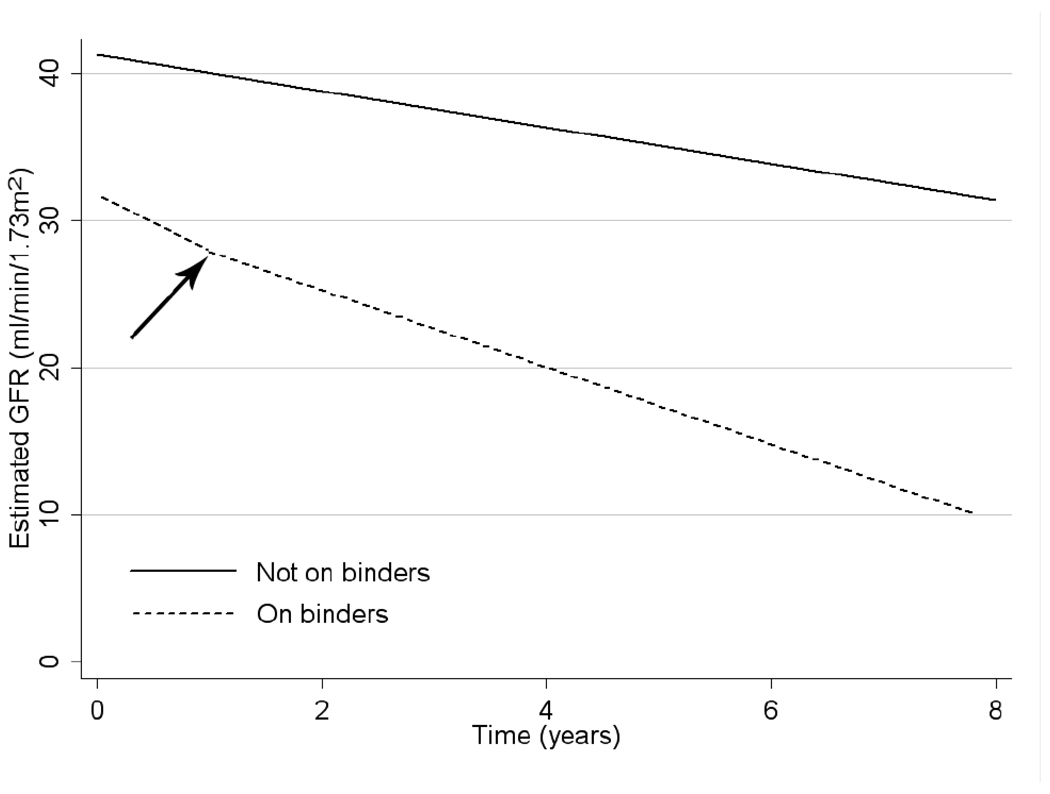

Figure 4 shows mean eGFR values over time in groups treated and not treated with binders. Figure 5 depicts the estimated slopes in mixed effect models of patients who never received a binder and the pre- and post-treatment slopes of patients treated with binders. Compared to untreated patients, the pre-treatment (baseline) slopes of patients who subsequently received a binder were significantly steeper (−1.23 ml/min/1.73m2/yr (−1.52 to −0.93) for untreated vs. −3.68 (−4.26 to −3.11) for patients who were later binder treated, p<0.001). Initiation of binder therapy was associated with a significant and favorable (less steep) change in slopes of eGFR compared to the pre-treatment slopes of the same patients in unadjusted and case-mix adjusted analyses of the overall cohort, but further adjustment for laboratory variables reduced these differences to a non-significant trend (Table 3). Subgroup analyses indicated that binder therapy was associated with slightly more favorable changes in the slopes of eGFR in younger patients, in patients with lower phosphorus and higher calcium levels, and in patients with better nutritional parameters (higher cholesterol and percentage of lymphocytes in WBC, and lower WBC) (Figure 6).

Figure 4.

Mean eGFR (95% confidence intervals) in patients who were and who were not treated with binders, assessed at monthly intervals during follow-up.

Figure 5.

Estimated mean slopes of eGFR vs. time in patients who were never treated with phosphorus binders (solid line) and in patients treated with phosphorus binders (dashed line). The arrow indicates the change in slope associated with the initiation of phosphorus binders in treated patients. Slopes were estimated from unadjusted mixed effect models in the respective subgroups.

Figure 6.

Differences in post-treatment vs. pre-treatment eGFR slopes (ml/min/1.73m2 per year) associated with binder therapy in various subgroups of patients treated with a phosphorus binder. 95% confidence intervals are indicated (horizontal lines). Results are adjusted for age, race, Charlson comorbidity index, diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease, blood pressure, body mass index, smoking status, enrollment period, the use of calcitriol, serum albumin, bicarbonate, calcium, phosphorus, alkaline phosphatase, blood hemoglobin, white blood cell count, percentage of lymphocytes and 24 hour urine protein and the presence or absence of a death or end stage renal disease event.

Results remained consistent in sensitivity analyses of patients enrolled after January 1, 2001; after substituting missing data points with imputed values; in patients using exclusively calcium-based binders; in calcium-using patients categorized according to their amount of elemental calcium intake; after excluding patients whose elemental calcium intake was <1000 mg/day; and after examining separately patients on combination binder-regimens of calcium plus sevelamer hydrochloride (data not shown).

Discussion

We examined associations between the routine clinical use of various phosphorus binders and relevant clinical end points in a large group of male patients with moderate and advanced non–dialysis-dependent CKD, and found that the application of these agents was associated with lower all-cause mortality and, with an overall neutral effect on the slopes of eGFR. The majority of the patients on binders in our cohort were administered calcium-containing medications; thus our results apply mainly to this group of binders.

The most plausible explanation for a beneficial impact of binder use on mortality is their phosphorus-lowering effect.1 The association of binder therapy with lower mortality in our study was more pronounced in the subgroup of patients with higher baseline serum phosphorus levels, which suggests that the observed benefit may directly or indirectly be mediated through a hyperphosphatemia-related mechanism of action. Epidemiologic studies in hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis patients have found significant associations between higher serum phosphorus and cardiovascular calcification and mortality,18;33 with similar results reported in patients with non–dialysis-dependent CKD.18;33 The increased mortality associated with higher serum phosphorus in observational studies could be explained by increased cardiovascular calcification occurring as a consequence of hyperphosphatemia;27 yet randomized controlled trials have never been conducted to test the hypothesis that lowering of serum phosphorus might improve mortality. Only one observational study in hemodialysis patients examined outcomes associated with phosphorus binders and reported a significant association with lower mortality,18 but to our knowledge no similar studies were performed in non–dialysis-dependent CKD. Compared to ESRD patients, those with non–dialysis-dependent CKD typically have lower serum phosphorus levels;18;33 hence the administration of binders is in general less frequent. Furthermore, the impact of such medications may be less obvious, as it may manifest itself in lowering urinary phosphorus excretion and serum levels of PTH and FGF-23 rather than in lowering serum phosphorus levels.1 These additional biochemical effects of binders in non–dialysis-dependent CKD may provide alternative explanations for the observed clinical benefit, as the affected biochemical parameters have themselves been associated with adverse outcomes.18;33 In our cohort the serum phosphorus of binder-treated patients showed an increase over time in spite of the treatment received, suggesting that the above alternative mechanisms of action may have played a role in the observed outcomes, rather than the lowering of serum phosphorus.

Higher serum phosphorus has been associated with a higher incidence of ESRD in several previous studies,18;33 and phosphorus restriction resulted in slower progression of CKD in small clinical trials.18;33 The latter studies were, however, confounded by the concomitant restriction of protein intake and by uneven blood pressure control, hence they could not examine the isolated effect of phosphorus restriction on progressive CKD. To the best of our knowledge no studies have examined the effect of binders on kidney function in CKD. In our study we noted a neutral effect of binder administration on the slopes of eGFR, suggesting no clear overall benefit from a mostly calcium-based binder regimen on progression of CKD. The significance of a benefit on progression of CKD seen in a number of our patient subgroups is unclear and warrants additional investigation.

Our study should be qualified by several potential limitations. The historical and observational nature of the study only allows us to establish associations, but not causal relationships. As patients were not randomly allocated to receive treatment with a binder selection, bias and unmeasured confounders might be responsible for the observed effects. We used various techniques such as propensity scores to mitigate such bias, but only controlled trials can fully resolve this problem. Our study was limited to male patients from a single institution; hence our results may not apply to the larger population with non–dialysis-dependent CKD. The enrollment of patients over an extended period of time in our study makes it possible that secular trends in medical practices could have affected patient outcomes differently based on the time of enrollment. To address this issue, we adjusted for the time of enrollment and we examined more contemporary patients separately, and found no differences in outcomes. We had limited data on PTH levels, hence we could not include this potential confounder in our analyses, but we were able to use instead serum alkaline phosphatase level as a marker of increased bone formation and an independent risk factor of mortality in MHD patients.18;33 Furthermore, adjustment for PTH levels would be expected to strengthen, and not to mitigate the association of phosphorus binders with favorable outcomes, given that such medications in general result in a lowering of serum PTH levels. We could not ascertain that all patients were administered calcium-based medications with the intent to lower serum phosphorus, since the proportion of patients using such medications in our cohort was higher than what has been reported in prior studies,18;33 and the serum phosphorus levels in the treated patients rose in spite of binder administration; it is thus possible that patients taking lower doses of calcium-based medications in our study might have used them as dietary supplements. In order to better segregate patients who might have received calcium containing medications with an indication as phosphorus binders we assessed outcomes separately in patients who took higher doses of said medications and also in patients who used a combination of calcium-based and non-calcium-based binders, and found that the results remained consistent in such sensitivity analyses. We hypothesized that cardiovascular events could have been the reason for deaths associated with improved phosphorus homeostasis, but we did not have causes of deaths available for analysis in order to test this hypothesis.

In conclusion, our analysis found that the administration of phosphorus binders is associated with lower mortality in male patients with moderate and advanced non–dialysis-dependent CKD. Our results strengthen earlier findings that linked hyperphosphatemia to adverse outcomes in ESRD and non–dialysis-dependent CKD, and should urge us to test phosphorus-lowering therapies in clinical trials.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

Support: Drs. Kovesdy and Kalantar-Zadeh received support from grant R01 DK078106-01. Further information on funding sources is listed in the financial disclosure.

Footnotes

This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Parts of this material were presented at the American Society of Nephrology Renal Week 2009, October 27 – November 1, 2009, San Diego, CA.

financial Disclosure: This study was supported by an investigator-initiated grant (without salary support) to Dr Kovesdy from Genzyme, which manufactured sevelamer hydrochloride; the study sponsor provided no input on data analysis and interpretation, and exerted no influence on manuscript preparation. Drs Kovesdy and Kalantar-Zadeh have received grant support and/or honoraria from Genzyme, Shire, and Fresenius, all of which market phosphate binders. The other authors declare that they have no relevant financial interests.

Reference List

- 1.Kovesdy CP, Kalantar-Zadeh K. Bone and mineral disorders in pre-dialysis CKD. Int Urol Nephrol. 2008;40:427–440. doi: 10.1007/s11255-008-9346-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Block GA, Klassen PS, Lazarus JM, Ofsthun N, Lowrie EG, Chertow GM. Mineral metabolism, mortality, and morbidity in maintenance hemodialysis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2004;15:2208–2218. doi: 10.1097/01.ASN.0000133041.27682.A2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kalantar-Zadeh K, Kuwae N, Regidor DL, et al. Survival predictability of time-varying indicators of bone disease in maintenance hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int. 2006;70:771–780. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5001514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Slinin Y, Foley RN, Collins AJ. Calcium, phosphorus, parathyroid hormone, and cardiovascular disease in hemodialysis patients: the USRDS waves 1, 3, and 4 study. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:1788–1793. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2004040275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tentori F, Blayney MJ, Albert JM, et al. Mortality risk for dialysis patients with different levels of serum calcium, phosphorus, and PTH: the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study (DOPPS) Am J Kidney Dis. 2008;52:519–530. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2008.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kimata N, Albert JM, Akiba T, et al. Association of mineral metabolism factors with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in hemodialysis patients: the Japan dialysis outcomes and practice patterns study. Hemodial Int. 2007;11:340–348. doi: 10.1111/j.1542-4758.2007.00190.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Noordzij M, Korevaar JC, Boeschoten EW, Dekker FW, Bos WJ, Krediet RT. The Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative (K/DOQI) Guideline for Bone Metabolism and Disease in CKD: association with mortality in dialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2005;46:925–932. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2005.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Young EW, Albert JM, Satayathum S, et al. Predictors and consequences of altered mineral metabolism: the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study. Kidney Int. 2005;67:1179–1187. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00185.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dhingra R, Sullivan LM, Fox CS, et al. Relations of serum phosphorus and calcium levels to the incidence of cardiovascular disease in the community. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:879–885. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.9.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tonelli M, Sacks F, Pfeffer M, Gao Z, Curhan G. Relation between serum phosphate level and cardiovascular event rate in people with coronary disease. Circulation. 2005;112:2627–2633. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.553198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kestenbaum B, Sampson JN, Rudser KD, et al. Serum phosphate levels and mortality risk among people with chronic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:520–528. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2004070602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Voormolen N, Noordzij M, Grootendorst DC, et al. High plasma phosphate as a risk factor for decline in renal function and mortality in pre-dialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2007;22:2909–2916. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfm286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kovesdy CP, Anderson JE, Kalantar-Zadeh K. Outcomes associated with serum phosphorus level in males with non-dialysis dependent chronic kidney disease. Clin Nephrol. 2010;73:268–275. doi: 10.5414/cnp73268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Norris KC, Greene T, Kopple J, et al. Baseline predictors of renal disease progression in the African American Study of Hypertension and Kidney Disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17:2928–2936. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005101101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schwarz S, Trivedi BK, Kalantar-Zadeh K, Kovesdy CP. Association of disorders in mineral metabolism with progression of chronic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;1:825–831. doi: 10.2215/CJN.02101205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gutierrez OM, Mannstadt M, Isakova T, et al. Fibroblast Growth Factor 23 and Mortality among Patients Undergoing Hemodialysis. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:584–592. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0706130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kovesdy CP, Ahmadzadeh S, Anderson JE, Kalantar-Zadeh K. Secondary hyperparathyroidism is associated with higher mortality in men with moderate to severe chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2008;73:1296–1302. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Isakova T, Gutierrez OM, Chang Y, et al. Phosphorus binders and survival on hemodialysis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:388–396. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008060609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kovesdy CP, Trivedi BK, Anderson JE. Association of kidney function with mortality in patients with chronic kidney disease not yet on dialysis: a historical prospective cohort study. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2006;13:183–188. doi: 10.1053/j.ackd.2006.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kovesdy CP, Trivedi BK, Kalantar-Zadeh K, Anderson JE. Association of low blood pressure with increased mortality in patients with moderate to severe chronic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2006;21:1257–1262. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfk057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Payne RB, Little AJ, Williams RB, Milner JR. Interpretation of serum calcium in patients with abnormal serum proteins. Br Med J. 1973;4:643–646. doi: 10.1136/bmj.4.5893.643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Levey AS, Bosch JP, Lewis JB, Greene T, Rogers N, Roth D. A More Accurate Method To Estimate Glomerular Filtration Rate from Serum Creatinine: A New Prediction Equation. Ann Intern Med. 1999;130:461–470. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-130-6-199903160-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.National Kidney Foundation. K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: evaluation, classification, and stratification. Am J Kidney Dis. 2002;39:S1–S266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Singer JD, Willett JB. Modeling Change and Event Occurrence. Oxford: Oxford University Press, Inc.; 2003. Applied Longitudinal Data Analysis. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thadhani R, Tonelli M. Cohort studies: marching forward. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;1:1117–1123. doi: 10.2215/CJN.00080106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fouque D, Kalantar-Zadeh K, Kopple J, et al. A proposed nomenclature and diagnostic criteria for protein-energy wasting in acute and chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2008;73:391–398. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jono S, McKee MD, Murry CE, et al. Phosphate regulation of vascular smooth muscle cell calcification. Circ Res. 2000;87:E10–E17. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.7.e10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Levin A, Bakris GL, Molitch M, et al. Prevalence of abnormal serum vitamin D, PTH, calcium, and phosphorus in patients with chronic kidney disease: results of the study to evaluate early kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2007;71:31–38. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barsotti G, Morelli E, Giannoni A, Guidu A, Lupetti S, Giovannetti S. Restricted phosphorus and nitrogen intake to slow the progression of chronic renal failure: a controlled trial. Kidney Int Suppl. 1983;16:S278–S284. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maschio G, Oldrizzi L, Tessitore N, et al. Effects of dietary protein and phosphorus restriction on the progression of early renal failure. Kidney Int. 1982;22:371–376. doi: 10.1038/ki.1982.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Blayney MJ, Pisoni RL, Bragg-Gresham JL, et al. High alkaline phosphatase levels in hemodialysis patients are associated with higher risk of hospitalization and death. Kidney Int. 2008;74:655–663. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Regidor DL, Kovesdy CP, Mehrotra R, et al. Serum alkaline phosphatase predicts mortality among maintenance hemodialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19:2193–2203. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008010014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Winkelmayer WC, Levin R, Avorn J. The nephrologist's role in the management of calcium-phosphorus metabolism in patients with chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2003;63:1836–1842. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00930.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]